Abstract

Atomic clocks are at the leading edge of accuracy and precision and are essential for synchronisation of distributed critical infrastructure, position, navigation and timing, and scientific applications. There has been significant improvements in the performance of atomic clocks with the shift from microwave to optical frequency transitions. However, this performance increase has come at the cost of size, complexity and fragility, which has confined optical clocks to laboratories. Here we report on a recent international collaboration where three emerging optical clocks, each based on different operating principles, were trialled at sea. These clocks demonstrated world-class performance and reliability by providing stable frequency outputs in optical, microwave and radio-frequency domains over three weeks of unsupervised naval operation.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Atomic clocks have been at the leading-edge of accurate and precise measurements since their invention in 19551. Following the International Bureau of Weights and Measures’ (BIPM) re-definition of the second in 1967 to depend on the caesium ground state transition frequency2 atomic clocks have been cemented at the heart of the International System of Units (SI). The much improved performance and lower systematic uncertainty associated with optical frequency atomic clocks has led to the expectation that the SI will soon move to a definition for the second based on an optical frequency transition3.

Since their invention, atomic clocks have increasingly been incorporated into infrastructure that is critical to our daily lives. The most notable and ubiquitous example is their use in the satellite constellations that form the various Global Navigation Satellite Systems (GNSSs). In addition to allowing precise navigation across the globe, atomic clocks are key in providing timing synchronisation across spatially-distributed networks including: telecommunications, distributed computing, electrical power grid synchronisation, relativistic geodesy and very-long baseline radio astronomy applications4,5,6,7,8. However, the benefits that have accrued from easy and universal availability of GNSS timing signals has perhaps led to an over-reliance in critical infrastructure. Furthermore, future high-speed communication and data processing applications will require local timing references with better stability than current microwave clocks can offer9,10. To overcome the vulnerabilities and performance shortcomings of GNSS-based timing dissemination on these dependent systems, there is a clear need to develop GNSS-independent, high-performance mobile atomic clocks that can deliver high-quality local timing signals in uncontrolled real-world environments11,12.

Atomic clocks typically use an oscillator to excite a narrow transition in an ensemble of unperturbed atoms. A signal is derived from this interaction which relates to the frequency difference between the oscillator and the atomic frequency and this is then used to lock the oscillator to the transition frequency. Historically, atomic clocks have used a microwave oscillator to drive atomic transitions in the electronic ground state of Cs or Rb atoms13. However, recent laboratory efforts have focused on using optical transitions with transition frequencies of the order of hundreds of terahertz14. This new generation of optical atomic clocks has demonstrated a massive leap in frequency stability compared to commercially-available microwave atomic clocks15,16,17,18,19,20,21,22, in part linked to their inherently higher quality-factor (Q-factor).

However, working in the optical domain also brings an increase in complexity, and so with a few notable exceptions, optical clocks are large, lab-based devices. Recently, optical lattice clocks23,24,25,26,27 and ion clocks28,29,30 have been shrunk to the scale of a cubic metre, allowing their transport between locations and rapid (circa days) return to operation. Vehicle transportable systems have also been demonstrated, such as Physikalisch-Technische Bundesanstalt’s (PTB’s) transportable strontium lattice clock31, and the Chinese Academy of Sciences’ calcium ion clock32. In both cases these occupy an air-conditioned trailer and are operable relatively quickly (circa days) after transport.

Though these devices offer exciting opportunities for the frequency metrology community, usefulness in broader applications in real-world environments requires a truly mobile timing reference that is fully automated and in operation even while in motion. A number of microwave clocks are capable of operating in this regime, with the most commercially successful of these being the Chip Scale Atomic Clock (CSAC)33 and Microchip Caesium Beam Clock (5071A)34. The first nascent steps for mobile optical clock technology have been taken with a molecular iodine vapour cell, which operated during a six minute flight on a sounding rocket35.

Here we report on a marine field trial of an ensemble of three vapour-based optical clocks, each operating on a fundamentally different architecture. This architectural difference leads to significant variations in environmental sensitivity of each clock strengthening the confidence in our estimation of the long-term frequency stability of the individual clocks. Further, the presence of three simultaneously operating high-performance optical clocks allows us to calculate the short-term performance of each individual optical clock, and thus verify their superiority over commercial microwave counterparts in deployed and uncontrolled environments.

The clocks were air-freighted from their respective institutions (two from the University of Adelaide (UofA), Australia, and the third from the Air Force Research Laboratory (AFRL), USA), installed on a ship (HMNZS Aotearoa), and operated autonomously at sea for three weeks. We note that along with the three portable optical atomic clocks reported here, a fourth clock technology based on molecular iodine was also demonstrated during the challenge36. As we show below, the performance and robustness of the three clocks reported here, along with the good performance of the technology explored in ref. 36, emphasises that a range of robust and compact optical atomic clocks have reached the maturity required to be tested in various deployed scenarios. With further engineering development these devices will soon find use in applied metrology and timekeeping applications.

Results

Portable optical clocks

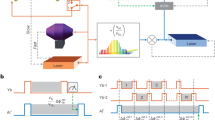

The three portable optical clocks that formed the mobile ensemble are pictured in Fig. 1a. Each system contains the key components of an optical atomic clock: a physics package that contains an atomic sample with a suitable, high quality-factor atomic feature; a photonics package that contains the laser source(s) and photonics to generate a tailored optical interrogation signal along with the digital control that locks the laser frequency to the atomic transition; and an optical frequency comb to down-convert that locked laser signal into radio-frequency (RF) and microwave signal outputs. All three clocks described here use a thermal vapour cell at the heart of their physics package. This avoids the complexity of laser cooling or trapping albeit at the potential expense of a higher environmental sensitivity. In each clock the optical transition has a modest linewidth of order 100 kHz, resulting in a sufficiently large Q-factor for high-performance operation, but also allowing high-speed feedback (circa 100 kHz) for active suppression of fast laser noise and conferring high reliability against external vibration and shock during operation.

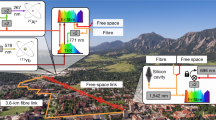

a The mobile clock systems: the UofA Yb clock, the UofA Rb clock, and the AFRL Optical Rubidium Atomic Frequency Standard (ORAFS). b The route taken by the HMNZS Aotearoa during one of the field trials, with an inset showing loading of the Office of Naval Research (ONR) SeaBox onto the deck of the ship via the ship’s crane. Made with Natural Earth. Free vector and raster map data @ naturalearthdata.com.

Two of the clocks were developed by UofA. The first of these, the Ytterbium Vapour Cell Clock (UofA Yb) is based on modulation transfer spectroscopy of the 556 nm inter-combination line in neutral ytterbium vapour. The second, the Rubidium Two-Photon Clock (UofA Rb) makes use of a two photon transition in a 87Rb vapour excited via two counter-propagating lasers at 780 nm and 776 nm37,38. The third clock, the Optical Rubidium Atomic Frequency Standard (ORAFS) was developed at AFRL and is based on the same two photon transition in 87Rb vapour, but is excited by a single laser at 778 nm39,40. Further details of the individual clock technologies can be found in the Methods section.

Maritime demonstration

The marine trial of the clock ensemble was undertaken as part of The Technical Cooperation Programme (TTCP) Alternative Position, Navigation, and Timing Challenge, which was managed by the Office of Naval Research. This afforded the rare opportunity to test cutting-edge alternative position, navigation, and timing (PNT) technologies in a relevant operational environment. During the challenge the clocks were installed within a heavily modified shipping container known as the SeaBox alongside other state-of-the-art quantum and precision PNT experiments from a variety of nations. The SeaBox was then loaded onto the deck of the HMNZS Aotearoa whilst she actively participated in the Rim of the Pacific exercise (RIMPAC-2022) in July-August 2022, an international maritime exercise based around Hawaii.

In total, the clocks operated at sea for a period of 21 days covering over 80 nautical miles (150 km). This was split over three trips, with the course followed during one of these shown in Fig. 1b. During the clocks’ time at sea the ship carried out various high-speed manoeuvres and other operations resulting in the clocks experiencing a wide range of acceleration, temperature, humidity, and vibration conditions. Accelerations of up to ±5 m/ s2 in a 7 Hz measurement bandwidth in all three axes were recorded by off-the-shelf inertial sensors embedded within the ensemble. The clocks were also subjected to significant temperature variations, with daily temperature swings within the thermally isolated clock housings of 3 K at a rate of up to 6 K per hour while the ship was underway, with more rapid temperature swings of up to 10 K recorded whilst the SeaBox was being accessed frequently before the ship left port. Additionally, the location of the SeaBox on the deck of the ship led to exposure to significant sea spray in adverse weather conditions.

Clock frequency measurements

To assess the performance of the clocks while at sea a versatile frequency comparison system was also installed within the SeaBox. The frequency comparison system was designed to allow the frequency stability of each clock within the ensemble to be measured in both the RF and optical domains, with the measurement architecture shown in Fig. 2. At the heart of the system is a K+K Messtechnik multi-channel zero-dead time phase and frequency counter41, referenced to a commercial Microchip 5071A microwave caesium beam clock34. Since the performance of each of our optical clocks is higher than the 5071A, a simple measurement of the clock output frequencies using this 5071A referenced system would be limited by the noise and drift performance of the 5071A and counter system rather than being indicative of the performance of the optical clocks themselves. However, as we show below, the simultaneous measurement of three high-quality optical clocks allows the use of the three-cornered hat technique42, which in turn allows estimation of the frequency stability of each individual clock without limitation by the 5071A reference.

In total, seven separate frequency measurements were logged simultaneously throughout the duration of the trial as shown in Fig. 2. These frequencies relate to frequency differences between the multiple RF and optical frequencies generated by each of the three clocks. The in-built optical frequency comb within each clock generated stable RF and microwave outputs at 100 MHz and 1 GHz respectively that were coherently related to the optical output frequencies of the clock. Our approach was to directly count the 100 MHz outputs of the three optical clocks, each of which are measurements against the common frequency reference provided by the commercial Cs clock. Although this measurement precision is limited by the performance of the Cs clock, it is possible to eliminate the Cs clock noise after the fact by taking pairwise differences between these measurements. In addition, we record the frequency difference between the 1 GHz outputs of the UofA Yb and UofA Rb clocks by mixing these microwave signals down to the RF domain (a direct measurement here would not have sufficient frequency resolution and would have been limited by the counter) and counting the resulting 10 kHz-range signal. Finally, we measured the relative frequency fluctuations between the optical frequency outputs of the three clocks. For the two Rb clocks we produced a difference frequency signal between their optical outputs by combining them on a photodetector—the RF output of the photodetector was recorded using the frequency counter. However, given the large difference in output frequencies of the Yb and Rb-based clocks, this direct approach was not possible. Instead, we used the integrated optical frequency comb in each of the UofA clocks to coherently synthesise a second optical output that was in the frequency environs of the output of the other clock, as shown in Fig. 2. We then measured the frequency difference between the synthesised signal and the second clock by combining them on a photodiode.

More details on the comparison system can be found in Section “Clock Comparisons and Analysis”.

The operation and resilience of the clocks is demonstrated in Fig. 3, where the direct measurements of the 100 MHz output of the clocks is shown as a fractional frequency shift over the total event duration of thirty days. The noise on short timescales throughout this plot is entirely limited by the 5071A used to reference the frequency counter and is common mode across all three raw clock measurements. The plot shows clock frequency variations during three measurement phases: a first period of ~10 days on land within the offices of an off-base contractor facility that provided a baseline measurement of clock performances in a well controlled, air-conditioned environment following transport to Hawaii, a five-day period in which the SeaBox was operated on land before it was loaded onto HMNZS Aotearoa, and an eight day operational period of the clocks while in harbour. Between the off-base and at-dock measurement runs was a nine-day period in which the clock units and other attending quantum technologies were repackaged into provided racks inside the Office of Naval Research’s SeaBox at Joint Base Pearl Harbor-Hickam (during which there is no data). The data after 13/07/22 shows the clock performance while the ship was underway on the route shown in Fig. 1b. This was divided into two four-day periods interrupted by an intentional removal of power that required the clocks to shutdown autonomously, shown in the figure with a dashed line. The AFRL team used on-board personnel to restart the clock while the UofA systems were designed to operate autonomously and automatically recover from a loss-of-power event. All clocks successfully re-started after this event and remained operational until they were intentionally deactivated once the ship returned to port.

Frequency vs time measurement of the 100 MHz RF outputs of the three clocks directly measured by the frequency counter during different stages of the trial. The three systems have been offset by 200 × 10−12 for clarity. The ORAFS data has been processed to remove shifts between data segment due to changes in the comb mode index used for optical to RF down-conversion. An additional offset of 2 × 10−9 has been removed from three segments of ORAFS data in which the clock was operated in a different locking scheme — denoted by a box with star (*).

Considering the measurements in Fig. 3 as a whole, the Yb clock was highly stable over the entire campaign. Averaged over a 1000 s window, the total fractional frequency deviation was less than 6 × 10−12 throughout.

The output of the UofA Rb clock displays a number of step changes in fractional frequency. These features arise after a frequency unlocking event, and correspond to small changes in the light shift of the clock on the order of 5 × 10−11 due to a change in intermediary-state detuning. The mechanism by which this leads to steps is described in Section “Rubidium Two-Photon Clock—UofA Rb”.

The ORAFS clock also shows a number of stepped changes in output frequency. These correspond to changes to the operational parameters and locking configuration that were made between measurement runs. Small shifts of order 5 × 10−11 were due to changes in optical power, causing a trade off between signal-to-noise and long-term stability. Larger steps of order 2 × 10−9 also occurred when the locking configuration was changed from 1f to 3f demodulation, another technique used to improve long term performance at the cost of signal-to-noise. The measured offset has been subtracted from the 3f configuration data shown in Fig. 3 (denoted by a white box) to better illustrate the operational time of the clock over the entire trial.

As all of the step-like features in both UofA Rb and ORAFS data correspond to the start or end of measurement periods, they do not contribute to frequency shifts within data sets.

Also of note in Fig. 3 is an increased short-timescale noise while the ship was underway (after 13/07/2022). As with the rest of the data this is entirely limited by the 5071A and is common between all three measurements. This is demonstrated in Fig. 4, where a two minute section of the fractional frequencies of the beat notes between clock optical outputs outputs is plotted along with the direct 100 MHz outputs and the instantaneous vertical acceleration data recorded by sensors embedded within the clocks.

a A two minute section of the fractional frequency shift of the optical beats between the three clocks measured by the frequency counter referenced to the 5071A. b The fractional frequency shifts of the 100 MHz outputs of each optical clock measured directly by the frequency counter referenced to the 5071A. c Vertical acceleration measured by a sensor within the clock.

A strongly correlated 8 Hz modulation is seen in the 100 MHz measurements against the commercial standard, which matches very well to the acceleration profile recorded contemporarily. In contrast, the optical beatnotes show no evidence of acceleration sensitivity at this level indicating that the increased short time scale noise at sea is associated with the acceleration sensitivity of the 5071A contaminating the frequency counter timebase. For optical beatnotes we expect the timebase noise to be suppressed by the ratio of the optical frequency to the beatnote frequencies of 10 MHz, 59 MHz, and 80 MHz for the UofA Yb vs. UofA Rb, UofA Yb vs. ORAFS, and UofA Rb vs. ORAFS comparisons respectively. This results in a measurement noise limit of better than 1 × 10−16 at worst—significantly lower than the performance of the optical clocks themselves.

Individual clock stabilities

A more detailed examination of the frequency stability of the individual clocks was made by carrying out a comprehensive statistical analysis of the frequency measurements. The results of this are shown in Figs. 5, 6 where we compare the RF, microwave and optical performance of the clocks whilst on shore during initial testing (Fig. 5), and whilst the HMNZS Aotearoa was underway (Fig. 6). We estimate the optical performance of each clock by calculating the Modified Allan deviation43 (ModADEV) for each comparison and then using a three-cornered hat estimation to extract the individual performances42. We choose the ModADEV measure because it distinguishes between phase flicker noise and white phase noise components, and has a simple relationship to the accumulated timing error. The three-cornered hat estimated ModADEV for each clock is plotted in Figs. 5, 6 (solid lines), as well as the direct ModADEV of the 1 GHz UofA Yb vs UofA Rb comparison (cyan).

Synthesised individual clock Modified Allan deviations (ModADEVs) calculated for the three direct optical comparisons (solid lines) and synthesised ModADEVs from 100 MHz measurements (dashed lines) while the clocks were on shore. 5071A counter reference is shown in black dashed line with closed circles. Shaded regions indicate the statistical confidence interval, as described in ref. 49. Use of the three-cornered hat method allows extraction of the performance of each individual clock, without noise or drift contributions from the 5071A counter reference. As discussed in text, the 100 MHz measurements are limited by counter noise, while the direct 1 GHz UofA Yb and UofA Rb clock comparison, as well as the three direct inter-clock optical comparisons, are not limited by this noise source.

Synthesised individual clock Modified Allan deviations (ModADEVs) calculated for the three direct optical comparisons (solid lines) and synthesised ModADEVs from 100 MHz measurements (dashed lines) while the clocks were at sea. 5071A counter reference is shown in black dashed line with closed circles. Shaded regions indicate the statistical confidence interval, as described in ref. 49.

Additional processing is required for the RF domain results since the 100 MHz clock outputs were directly counted, and are therefore limited not only by the 5071A reference as discussed earlier, but also by noise introduced by the counter itself. To analyse the RF performance we first take frequency differences between independent pairs of the 100 MHz measurements. This removes noise and drift contributions from the 5071A and generates three effective comparisons between the 100 MHz clock outputs. We then extract the RF ModADEV (dashed lines on Figs. 5, 6) of each individual clock by using three-cornered hat estimation as before. As the Cs 5071A is significantly noisier than the other clocks in the comparison we can estimate its performance from the noise in the direct frequency measurements. This is shown on Figs. 5, 6 in black.

The integrated frequency combs should faithfully transfer the clocks’ optical frequency stability into its RF outputs and hence one would expect the RF and optical ModADEVs to agree exactly. Whilst true for times longer than 100 s, the RF measurements show elevated noise at times shorter than this. This is due to counter noise impacting the 100 MHz measurements, which is uncorrelated between counter channels and therefore cannot be removed as common-mode noise. We confirm this by comparing the UofA Yb vs UofA Rb 1 GHz comparison measurement to the UofA Yb and UofA Rb optical performances. The higher carrier frequency of these comparisons lowers the contribution of the counter noise to the resulting measurement such that it is no longer setting the measurement limit. The 1 GHz measurement shows a fractional frequency stability that is identical to the sum of the optical frequency instabilities of the two UofA clocks for integration times greater than 100 ms. Separate lab-based measurements of the additive noise of the frequency combs show an out-of-loop contribution of less than 2 × 10−15 at 1 s, this itself limited by measurement noise. This demonstrates that the integrated frequency combs are indeed capable of fully transferring the optical stability of the clocks into the RF domain and that the additional instability seen in the 100 MHz RF measurements is associated with the frequency measurement system rather than the clocks themselves.

All three optical clocks within the ensemble show a significant improvement in performance over the 5071A for integration times shorter than 1000 s. For example, the UofA Yb clock shows a stability in the 10−14 domain from 100 ms to 80 ks of integration time. This improvement in performance by more than an order of magnitude at short and medium timescales will be key for future applications such as high-speed communication and data processing. Comparing Figs. 5, 6, the short-term performance (integration times below 100 s) of each clock at sea was similar to that exhibited in the on-shore test. For measurement times beyond 100 s, each clock showed a decreased frequency stability in the moving environment when compared to the stationary tests. It is difficult to disentangle the effects of environmental influences on individual clocks, as well as the same influences on the inter-clock measurement apparatus. Unlike macroscopic resonators, atomic transitions do not possess a fundamental sensitivity to most common environmental influences such as temperature, humidity, or acoustics. These noise sources instead couple into the clock outputs through intermediary processes such as the misalignment of optical beam paths. Addressing these issues is the target of further engineering development. We note that despite this, these results represent a step-change improvement for portable timing solutions.

Discussion

The three optical clock technologies represented here balance a necessary compromise between the high stabilities offered by the world’s best lab-based optical clocks, against the robustness and practical considerations required to make a portable, deployable device. This trade-off is illustrated in Fig. 7 where we compare a range of both microwave and optical clocks as a function of their frequency instability at 1 s and a measure of their combined size-weight-and-power (SWaP) metric in cm3 kg W. The clocks range from compact commercial microwave clocks in the top left, to ultra-high performance transportable optical lattice clocks in the bottom right. Previously demonstrated transportable optical clocks are shown in blue although we note that the SWaP remains prohibitively high for deployed applications.

Fractional frequency stability at 1 s vs Size-Weight-and-Power of UofA Yb, UofA Rb and ORAFS, compared to a limited selection of commercially available and emerging microwave (red) and optical (blue) portable atomic clocks. CSAC: Microchip Chip scale atomic clock33; PRS 10: Stanford Research Systems Low phase noise Rb oscillator50; 5071A: Microchip 5071A Primary frequency standard34; SD cRb: SpectraDynamics cold Rubidium microwave atomic clock51; MuClock: Muquans MuClock52; MHM Maser: Microchip MHM-2020 Active hydrogen maser53; DSAC: Deep space atomic clock54; NPL Cs: National Physics Laboratory Cs Fountain55; VA: Vector Atomic Evergreen-3036; OptiClock: Yb ion clock30; Tiqker: Infleqtion Tiqker56; WIPM 2020: Ca ion clock32; LENS: Sr Lattice clock23; RIKEN: Sr Lattice clock57; PTB: Sr Lattice clock31. This has been reproduced from ref. 58.

The atomic-vapour-based optical clocks demonstrated here, as well as the other optical clock technology demonstrated in the trial36, have made a breakthrough reduction in SWaP whilst still making significant improvements in performance over currently available and emerging microwave clocks. The SWaP breakdown for UofA Yb, UofA Rb and ORAFS is shown in Table 1. The SWaP of these clocks is now such that they can be installed by a single person within existing infrastructure and be easily powered by a single mains outlet. In the case of the two UofA clocks, operation during transport both on-foot and within a moving vehicle whilst within their normal cases as seen in Fig 1(a) has also been demonstrated. Furthermore, each system has reached a sufficient level of automation that they operate without human intervention.

The results of a field trial of a mobile optical clock ensemble at sea presented here confirm that vapour-based optical clocks with integrated frequency combs are now on the cusp of real-world applications. Future development of optical atomic clocks into off-the-shelf devices will deliver wide-ranging benefits providing reliable PNT for vessels operating under a diverse set of conditions, including undersea or in dense urban environments. In the commercial sphere, precision timing is critical for any system that requires synchronisation, where portable optical clocks will provide significant competitive advantage. The mobile and autonomous optical atomic clocks will also support the scientific community through allowing for better tests of fundamental physics, relativistic geodesy, and synchronisation of distributed sensors such as very-long baseline interferometry arrays amongst other applications.

Methods

Ytterbium cell atomic clock—UofA Yb

The UofA Yb clock is based on the singly-forbidden 1S0 → 3P1 transition in neutral ytterbium-174, with optical frequency ν0 = 539, 386, 600, 191(118) kHz44. This species and transition was chosen because it was amenable to a simple vapour cell architecture, with a narrow clock transition and a convenient wavelength for excitation with commercially available fibre lasers. The particular isotope was chosen as it has the largest relative abundance and a desirable electronic configuration in which the lack of nuclear spin combined with the filled external S shell results in a single ground state with low magnetic sensitivity. Further, the lack of any nearby single or two-photon transitions from either the ground or excited state provides a low sensitivity to light-shifts.

The interrogation of the atomic transition is achieved using modulation transfer spectroscopy (MTS), which provides for a high signal to noise ratio. Frequency modulation of a strong pump beam is converted to intensity modulation of a weak, counter-propagating probe beam through the optical pumping of the atomic medium. Coherent demodulation of the transmitted probe intensity provides for a sub-Doppler error feature with high contrast and low contamination from the broader Doppler background.

The Yb interrogating laser system consists of a seed fibre laser at 1112 nm, which is amplified and frequency doubled to 556 nm using a fibre-coupled waveguide second harmonic generator module (SHG). The 556 nm light is split into pump and probe arms— the pump arm is frequency-modulated by an acousto-optic modulator (AOM), while the probe arm passes through a voltage-controlled optical attenuator (VOA). The combination of these two actuators provides the ability to control the power of both beams, while the AOM additionally allows for residual amplitude modulation (RAM) suppression. The pump and probe beams are directed to the vapour cell. All input and output signals are monitored and a pair of field-programmable gate array (FPGA) signal processing units are used to maintain the necessary control loops for optical power control, frequency stabilisation, and RAM suppression. The direct clock output is taken from a sample of the 1112 nm light before the SHG unit.

The vapour cell is designed with a central zone hot containing the Yb metal sample and cold ends with standard vacuum viewports45. The atomic vapour is localised to the central zone by a low pressure (6 Pa) of argon gas, which is maintained in the range of 350 °C to 400 °C. This is a trade off between size of the error signal and longevity of the cell higher temperature results in improved SNR and better short term stability at the cost of increased power consumption and reduced cell lifetime. At the temperature and pressure used in this design we achieve a saturation absorption feature with greater than 10% contrast, and able to operate for longer than six months continuously. The absolute limit to the lifetime has not been well identified.

The output signal of this clock provides an optical frequency reference for a self-referenced optical frequency comb based on the National Institute for Standards and Technology (NIST) design46. This frequency comb is steered to ensure that the beat note between its nearest optical frequency mode and the Yb clock output is phase locked to a numerically-controlled oscillator (NCO) referenced to the comb’s repetition rate. The comb’s carrier-envelope offset (CEO) frequency is also phase-locked to another NCO using the same reference. The pulse train output of the comb is also measured on a high-speed photodetector from which we deliver stable RF frequencies at the base repetition rate of the comb (200 MHz) as well as its higher harmonics. We specifically choose the fifth harmonic of the repetition rate at 1 GHz to allow for high sensitivity microwave clock comparisons. The 200 MHz output is also divided to 100 MHz and 10 MHz using the FPGA unit to provide standard countable RF outputs.

Both the clock and comb control systems are managed by a dedicated mini-PC embedded in the larger clock package which performs oversight tasks such as a cold-start procedure, status logging, error state detection, and re-start protocols. The clock system is entirely autonomous, with the transition from a cold start to a fully operational clock achieved in 30 minutes via key-turn operation. The Yb clock has run independently for months at a time without human intervention. The physical package occupies 7 rack units in a standard 19" rack with a total volume of 67 L, including clock, comb, oversight and power supply, with a weight of 40 kg and wall-socket power consumption of 210 W.

Optical rubidium atomic frequency standard—ORAFS

The AFRL ORAFS clock is based upon the design previously described in ref. 39,40. ORAFS uses counter-propagating 778.1 nm beams to perform Doppler-free excitation of the two-photon 5S1/2 → 5D5/2 transition in 87Rb. A telecommunications fibre laser at 1556.2 nm is amplified using a semiconductor optical amplifier (SOA), and then frequency-doubled via a SHG to generate the 778.1 nm light used to excite the two-photon transition. The laser power delivered to the Rb atoms is detected just before the Rb cell and then actively stabilised by feeding back to the current of the SOA, which modulates the gain, and hence the total optical power. The interrogating laser is frequency modulated and one observes consequent intensity modulation of a 420 nm fluorescence produced via the 6P3/2 decay pathway, whose complex amplitude is indicative of the average detuning of the 778 nm laser signal from exact two-photon resonance. Synchronous demodulation of the amplitude of this fluorescence signal delivers a signal proportional to this frequency detuning. A commercial-off-the-shelf laser driver and locking electronics were used to lock the frequency of the 1556.2 nm laser to that of the atomic transition.

The other control systems and control electronics were implemented on an FPGA platform and placed in a vacuum (<1 × 10−4 Pa) along with the laser, frequency comb, and vapour cell physics package. The lasers, vapour cell and electronics occupy a volume of 112 L, weigh 30 kg, and consume 300 W of electrical power. We note, however, that since this clock was originally designed to operate in a vacuum environment, it was necessary to operate the clock within a vacuum chamber together with appropriate vacuum pumps and a heat rejection plate. The total footprint of the system including ancillary vacuum apparatus occupies 46 rack units, weighs 310 kg, and consumes 1300 W of wall-socket power. An in-built self-referenced optical frequency comb has its repetition rate actively steered so that one mode of the comb is frequency stabilised to the 1556.2 nm laser output. Further, by detecting the fundamental repetition rate of the comb one automatically obtains a highly stable 100 MHz microwave output for comparison purposes with other RF sources.

Rubidium Two-Photon clock—UofA Rb

The UofA Rb clock utilises dual-colour excitation of the two-photon 5S1/2 → 5D5/2 transition in 87Rb. The excitation light is derived from two telecommunications lasers at 1552 nm and 1560 nm by frequency doubling using two SHGs, with the resulting 776 nm and 780 nm beams launched in opposing directions in the vapour cell to minimise Doppler broadening from the atomic motion. We frequency modulate the 1552 nm laser, and observe synchronous intensity modulation of the 420 nm fluorescence from the 6P3/2 decay pathway when the sum frequency of the two lasers is near two-photon resonance. This fluorescent light is detected with photomultiplier tubes and then demodulated with the frequency modulation signal. The resulting error signal allows us to steer the frequency of the 1552 nm laser so that the sum of the 776 nm and 780 nm photons corresponds to exact two-photon resonance.

A small portion of the 1552 nm and 1560 nm light is directed through a sum frequency generator (SFG) to generate the stable optical output of the clock at 778 nm. This can be used for comparison purposes and was used for the direct optical comparisons with the ORAFS clock, as well as with the UofA Yb comb. This 778 nm clock output light is then used to stabilise the repetition rate of the dedicated self-referenced optical frequency comb via a phase-locked loop (similarly to that described previously in both the ORAFS and Yb clocks). Finally the 1560 nm is offset-locked to the nearest mode of the optical frequency comb, fixing the intermediary-state detuning of the two-photon excitation and removing the final degree of freedom. As with the UofA Yb clock, the comb design was based on that from46.

This two-colour excitation delivers freedom to tune the 780 nm laser so that the first step of the two-photon excitation is nearly co-incident with the 5S1/2 → 5P3/2 transition in Rb. This near-resonant first step gives a large enhancement of the two-photon transition rate for a given input power. The disadvantage of the two-colour approach is that it introduces an unwanted residual Doppler broadening (~4 MHz) to the transition width along with introducing the extra complexity of two lasers. Two AOMs are used to stabilise the powers of the two lasers, with the 1552 nm AOM additionally providing frequency modulation of the 1552 nm light. The AOM-based modulation introduces unwanted RAM, which is detected along with the optical powers of the two lasers on photodetectors near to the Rb cell. We actively steer the RF drive level of the 1552 nm AOM to suppress the unwanted amplitude modulation. The physics package is actively temperature stabilized to between 60 ∘C and 70 ∘C to maintain constant Rb number density. This clock architecture is described in more detail in refs. 37,38.

All stabilisation feedback loops are implemented using software running on FPGA platforms with a master control computer running an automation and oversight script. This allowed the clock to cold-start, stabilise all feedback loops, and provided for error handling autonomously. This approach also allowed for remote monitoring during some phases of the sea trial. The clock system is entirely autonomous, with the transition from a cold start to a fully operational clock achieved in 30 min via key-turn operation. As mentioned above, evident in Fig. 3, are step-like features in the optical frequency output of the Rb clock after the autonomous system re-locks the lasers to the transition. This unwanted feature arises because when relocking the 1560 nm laser the automation system is unable to ensure that the laser is relocked to the same specific comb mode on each occasion. This discrete change in frequency of the 1560 nm laser resulted in a discrete change in the resulting light shift of the clock transition because of the change in detuning of the 1560 nm laser from the 5S1/2 → 5P3/2 transition in Rb. The effect of this on the clock frequency stability is described in detail in ref. 38 In the next iteration of the clock this will be prevented by ensuring that the autonomous system relocks the laser to a defined comb mode.

The Rb clock has operated independently for months at a time without human intervention or restarts. The physical package occupies 7 rack units in a standard 19" rack with a total volume of 81 L, including clock, comb, oversight and power supply, with a weight of 45 kg and wall-socket power consumption of 340 W.

Clock comparisons and analysis

The phase/frequency counter is a high performance device by K+K47,48 that allows simultaneous zero-dead-time frequency measurements of 8 inputs in comparison to an external 10 MHz clock input provided by the commercial Microchip Cs beam clock (5071A). This measurement configuration is shown in Fig. 2. We poll the counter at 100 ms intervals and record the data to the disk of a dedicated rugged computer for later processing. This allowed uninterrupted measurements over the duration of the exercise even in the event of an individual clock restart.

In addition to the direct measurement of each clock’s 100 MHz output, optical and microwave comparisons between the clocks were also recorded. For the optical frequency comparison between the UofA Yb and Rb clocks, we undertook the comparison at double the wavelength of the Yb transition (1112 nm), with this wavelength directly available from the Yb optical clock and accessible as a comb-mode from the UofA Rb clock’s optical frequency comb. For the optical frequency comparison between the two Rb clocks, we made use of a direct optical comparison between the 778 nm optical outputs of the two clocks, without the need of an optical frequency comb. The ORAFS to UofA Yb clock comparison was made at 778 nm through a beat note between the ORAFS 778 nm clock output and an optical comb mode from the Yb clock generated by frequency doubling of the stable comb output centred around 1556 nm. Although complex, this system ensured that the counter always had available at least one strong difference frequency signal from each of the clock comparisons.

For the analysis of the optical frequency comparisons, the measured direct difference frequency signals were processed by scaling by the optical frequency and removing the mean frequency to produce fractional frequency data. This time-series data is then passed through the Modified Allan deviation algorithm (ModADEV)43 to produce the conventional expression of frequency instability as a function of integration time. As we have three pairwise comparisons between three non-identical clocks it is possible to perform a three-cornered-hat analysis42—taking linear combinations of those comparisons to estimate the instability contribution associated with each individual clock. This technique assumes uncorrelated data, which we expect to be a good assumption over short time scales, however due to the co-located nature of the clocks, and the dramatic environmental variations they all experienced, it is likely that over long time scales this approximation will fail (as would be the case for any co-located clock comparisons). Nonetheless, it is worth noting that since the three clocks presented here differ in construction, atomic species and in interrogation protocol, this has potentially less susceptibility to systematic errors of this type, since the environmental sensitivities of each system are not inherently matched.

Data availability

Data underlying the results presented in this paper are not publicly available as they were collected during an international military exercise but may be obtained from the authors upon reasonable request and approval from the sponsor.

Code availability

Code used to process the data presented in this paper is available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

References

Essen, L. & Parry, J. V. L. An atomic standard of frequency and time interval: A cæsium resonator. Nature 176, 280–282 (1955).

On the future redefinition of the second. Resolution 1 of the 13th CGPM (1967).

On the future redefinition of the second. Resolution 5 of the 27th CGPM (2022).

Tavella, P. & Petit, G. Precise time scales and navigation systems: mutual benefits of timekeeping and positioning. Satell. Navig. 1, 1–12 (2020).

Schuldt, T. et al. Optical clock technologies for global navigation satellite systems. GPS Solut. 25, 1–11 (2021).

Boldbaatar, E., Grant, D., Choy, S., Zaminpardaz, S. & Holden, L. Evaluating optical clock performance for GNSS positioning. Sensors 23, 5998 (2023).

Takano, T. et al. Geopotential measurements with synchronously linked optical lattice clocks. Nat. Photonics 10, 662–666 (2016).

Rochat, P. Droz, F. Wang, Q. and Froidevaux, S. Atomic clocks and timing systems in global navigation satellite systems. In Proceedings of European Navigation Conference, Gdansk, April, pages 1–11, 2012.

Marin-Palomo, P. et al. Performance of chip-scale optical frequency comb generators in coherent WDM communications. Opt. Expr. 28, 12897–12910 (2020).

Hillerkuss, D. et al. Single-laser 32.5Tbit/s Nyquist WDM transmission. J. Opt. Commun. Netw. 4, 715–723 (2012).

Petrov, D. Melnik, S. and Hämäläinen, T. Distributed GNSS-based time synchronization and applications. In 2016 8th International Congress on Ultra Modern Telecommunications and Control Systems and Workshops (ICUMT), pages 130–134. IEEE, 2016.

Hasan, K. F., Feng, Y. & Tian, Y.-C. GNSS time synchronization in vehicular ad-hoc networks: Benefits and feasibility. IEEE Trans. Intell. Transp. Syst. 19, 3915–3924 (2018).

Hellwig, H. W. Atomic frequency standards: A survey. Proc. IEEE 63, 212–229 (1975).

Ludlow, A. D., Boyd, M. M., Ye, J., Pei, E. & Schmidt, P. O. Optical atomic clocks. Rev. Mod. Phys. 87, 637–701 (2015).

Ushijima, I., Takamoto, M., Das, M., Ohkubo, T. & Katori, H. Cryogenic optical lattice clocks. Nat. Photonics 9, 185–189 (2015).

Huntemann, N., Sanner, C., Lipphardt, B., Tamm, C. & Peik, E. Single-ion atomic clock with 3 × 10−18 systematic uncertainty. Phys. Rev. Lett. 116, 063001 (2016).

Gao, Q. et al. Systematic evaluation of a 171Yb optical clock by synchronous comparison between two lattice systems. Sci. Rep. 8, 8022 (2018).

McGrew, W. F. et al. Atomic clock performance enabling geodesy below the centimetre level. Nature 564, 87–90 (2018).

Bothwell, T. et al. JILA SrI optical lattice clock with uncertainty of 2.0 × 10−18. Metrologia 56, 065004 (2019).

Oelker, E. et al. Demonstration of 4.8 × 10−17 stability at 1 s for two independent optical clocks. Nat. Photonics 13, 714–719 (2019).

Sanner, C. et al. Optical clock comparison for lorentz symmetry testing. Nature 567, 204–208 (2019).

Hobson, R. et al. A strontium optical lattice clock with 1 × 10−17 uncertainty and measurement of its absolute frequency. Metrologia 57, 065026 (2020).

Poli, N. et al. A transportable strontium optical lattice clock. Appl. Phys. B 117, 1107–1116 (2014).

Origlia, S. et al. Towards an optical clock for space: Compact, high-performance optical lattice clock based on bosonic atoms. Phys. Rev. A 98, 053443 (2018).

Kong, D.-H. et al. A transportable optical lattice clock at the national time service center. Chin. Phys. B 29, 070602 (2020).

Ohmae, N. et al. Transportable strontium optical lattice clocks operated outside laboratory at the level of 10−18 uncertainty. Nat. Photonics 14, 411–415 (2020).

Kale, Y. B. et al. Field deployable atomics package for an optical lattice clock. Quantum Sci. Technol. 7, 045004 (2022).

Cao, J. et al. A compact, transportable single-ion optical clock with 7.8 × 10−17 systematic uncertainty. Appl. Phys. B 123, 112 (2017).

Khabarova, K. et al. Toward a new generation of compact transportable Yb+ optical clocks. Symmetry, 14, 2022.

Stuhler, J. et al. Opticlock: Transportable and easy-to-operate optical single-ion clock. Meas.: Sens. 18, 100264 (2021).

Grotti, J. et al. Geodesy and metrology with a transportable optical clock. Nat. Phys. 14, 437–441 (2018).

Huang, Y. et al. Geopotential measurement with a robust, transportable Ca+ optical clock. Phys. Rev. A 102, 050802 (2020).

Microchip Technology Inc. Low-Noise Chip-Scale Atomic Clock—datasheet (2023).

Microchip Technology Inc. 5071A Cesium Primary Time and Frequency Standard—sell sheet (2023).

Döringshoff, K. et al. Iodine frequency reference on a sounding rocket. Phys. Rev. Appl. 11, 054068 (2019).

Roslund, J. D. et al. Optical clocks at sea. Nature 628, 736–740 (2024).

Perrella, C. et al. Dichroic two-photon rubidium frequency standard. Phys. Rev. Appl. 12, 054063 (2019).

Ahern, E. J. et al. Tailoring the stability of a two-color, two-photon rubidium frequency standard. Phys. Rev. Appl. 23, 044025 (2025).

Martin, K. W. et al. Compact optical atomic clock based on a two-photon transition in rubidium. Phys. Rev. Appl. 9, 014019 (2018).

Lemke, N. D. et al. Measurement of optical rubidium clock frequency spanning 65 days. Sensors 22 (2022).

Messtechnik, K. K. K+K FXE Phase + Frequency Meter. https://kplusk-messtechnik.de/products/fxe_19.htm (2021).

Gray, J. E. and Allan, D. W. A method for estimating the frequency stability of an individual oscillator. In 28th Annual Symposium on Frequency Control. 243–246 (1974).

Allan D. W. and Barnes J. A. A modified “Allan variance" with increased oscillator characterization ability. In Thirty Fifth Annual Frequency Control Symposium, pages 470–475, 1981.

Atkinson, P. E., Schelfhout, J. S. & McFerran, J. J. Hyperfine constants and line separations for the 1S0 − 3P1 intercombination line in neutral ytterbium with sub-Doppler resolution. Phys. Rev. A 100, 042505 (2019).

Vilshanskaya, E. V. et al. Saturation spectroscopy of calcium atomic vapor in hot quartz cells with cold windows. J. Phys.: Conf. Ser. 946, 012130 (2018).

Sinclair, L. C. et al. Invited article: A compact optically coherent fiber frequency comb. Rev. Sci. Instrum. 86, 081301 (2015).

Kramer, G. and Klische, W. Multi-channel synchronous digital phase recorder. In Proceedings of the 2001 IEEE International Frequncy Control Symposium and PDA Exhibition (Cat. No. 01CH37218), pages 144–151. IEEE, 2001.

Kramer, G. and Klische, W. Extra high precision digital phase recorder. In 2004 18th European Frequency and Time Forum (EFTF 2004), pages 595–602. IET, 2004.

Riley, W. J. Handbook of frequency stability analysis. NIST Special Publication 1065 (National Institute of Standards and Technology, Boulder, CO, 2008).

Stanford Research Systems. PRS10 Rubidium Frequency Standard Data Sheet. Available at https://www.thinksrs.com/products/prs10.html

SpectraDynamics. cRb-Clock: Portable Cold Rubidium Microwave Atomic Clock. Available at https://spectradynamics.com/products/crb-clock/

Muquans. MuClock: A High-Performance Frequency Standard Based on Cold Atoms. Product Datasheet (2019). Available at https://www.muquans.com/product/muclock/

Microchip Technology. MHM-2020 Active Hydrogen Maser Data Sheet DS50002965B (2024).

Burt, E. A. et al. Demonstration of a trapped-ion atomic clock in space. Nature 595, 43–47 (2021).

Hendricks, R. J. et al. Cs fountain clocks for commercial realizations—an improved and robust design. IEEE Trans. Ultrason. Ferroelectr. Freq. Control 66, 624–631 (2019).

Infleqtion. Tiqker Optical Clocks for Satellite Applications. White Paper Rev. 05 (2025).

Takamoto, M. et al. Test of general relativity by a pair of transportable optical lattice clocks. Nat. Photonics 14, 411–415 (2020).

White, B., Offer, R. F., Hilton, A. P. & Luiten, A. N. The SWaP plot: Visualising the performance of portable atomic clocks as a function of their size, weight and power. Preprint at https://arxiv.org/abs/2409.08484 (2024).

Acknowledgements

The data presented here was collected at a TTCP Intelligence Surveillance Target Acquisition and Reconnaissance (ISTAR) group Alternative Position, Navigation and Timing (APNT) event at the Rim of the Pacific (RIMPAC) exercise out of Pearl Harbor, Hawaii in July August 2022. TTCP is a five nation (Australia, Canada, New Zealand, United Kingdom, United States) Defence Science and Technology collaborative research programme. We would particularly like to thank the DSTG staff who supported the exercise, including Joe Verringer, Vance Crook, Joanne Harrison, Ken Grant, and Scott Foster. We would like to thank Tommy Willis from the Office of Naval Research for organising the APNT Challenge and providing the SEABOX, and David Collier for managing the day-to-day access and facilities during the demonstration. This research was supported by the Australian Government through the Next Generation Technologies Fund (now managed through ASCA) (A.N.L). We thank the Optofab node of the Australian National Fabrication Facility (ANFF) which utilize Commonwealth and South Australia State Government funding. The authors thank Evan Johnson, Alastair Dowler, and Lijesh Thomas and the rest of the Optofab team for their technical support. The authors thank Pacific Rim Defense for provide the space, access, and amenities used for the pre-trial benchmarking tests.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

A.P.H., R.F.O., S.K.S. and E.K. wrote the manuscript. All authors provided editorial comments on the manuscript. A.P.H., R.F.O., E.K. and B.W. developed the UofA ytterbium clock. S.K.S., C.L., C.P. and E.A. developed the UofA rubidium clock. N.B.H. and C.L. developed and built the UofA frequency combs. N.B.H. and C.B. provided software and control solutions for the UofA clocks. M.N. and J.W.A. provided engineering solutions for the UofA clocks. K.W.M., R.B. and J.D.E developed the AFRL clock and managed their participation in the trial. B.M.S. coordinated the field trial. A.N.L. leads the UofA clocks team and their managed their participation in the trial.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare the following competing interest: Andre Luiten is co-founder, part owner and Managing Director of QuantX Labs Pty Ltd. QuantX holds commercial IP rights to some University of Adelaide IP, including the Yb and Rb clocks described in this work. The remaining authors declare no competing interests.

Peer review

Peer review information

Nature Communications thanks the anonymous reviewer(s) for their contribution to the peer review of this work. A peer review file is available.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Disclosures

Approved for public release, distribution is unlimited. Public Affairs release approval # AFRL-2024-2933. The views expressed are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the official policy or position of the Department of the Air Force, the Department of Defense, or the U.S. government. The intellectual property related to the Rubidium Two-Photon Clock is owned by QuantX Labs and covered by patent US 10353270 B2.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Hilton, A.P., Offer, R.F., Klantsataya, E. et al. Demonstration of a mobile optical clock ensemble at sea. Nat Commun 16, 6063 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-025-61140-2

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-025-61140-2