Abstract

One preferred lead-free ferroelectric, (K,Na)NbO3, offers prominent features of environmentally benign and excellent piezoelectricity, but suffers from poor ferroelectricity. Mn-doping has improved its electrical properties, yet its site occupancy remained unclear. In this study, Mn-atomic-layered antiphase boundaries were created in (K,Na)NbO3-based films, revealing Mn occupying the A-site position. These boundaries stabilized ferroelectricity in these (K,Na)NbO3-based films with a large twice remnant polarization (~72.5 μC/cm2) across a wide frequency range (20 Hz−10 kHz). High-resolution imaging shows densely arranged antiphase boundaries are grown along three crystal axes. These boundaries are Mn-atomic-enriched at a nanoscale width of a single unit cell, equilibrating the interfacial charges and clamp the interfacial strain, resulting in the highly squared hysteresis loops and high Curie temperature of ~400 °C in the films. Our results may provide a paradigm for designing high-performance lead-free ferroelectric films, unleashing their application potential for expelling lead-containing counterparts.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Many lead-free ferroelectric systems are being investigated for replacing Pb(Zr,Ti)O3 due to the toxic lead to the environment and human health1,2,3. One preferred alternative (K,Na)NbO3 (KNN) is non-toxic and has previously achieved giant piezoelectric response in its both ceramic and film forms4,5. But its ferroelectricity is poor, the polarization of complex chemically modified-KNN film [twice remnant polarization (2Pr) ~ 64.91 μC/cm2] ever reported is still far inferior to the values of other perovskite lead-free ferroelectric films, e.g., BaTiO3 (2Pr ~ 200 μC/cm2) and BiFeO3 (2Pr ~ 260 μC/cm2)6,7,8. As known, the information storage depends on the switching and movement of ferroelectric domain wall, which is associated with the structural defect and polarization behavior9. For example, the reorientation of mobile defects inside BiFeO3 films can decay the domain written time10, and the charged defects inside Pb(Zr0.6Ti0.4)O3 determine the evolution of domain wall pinning process11. The structurally and chemically coexisted defects in ferroelectric materials, which can be regarded as phase boundary, can tune the polarization switching and induce diverse switching behaviors12,13,14.

The antiphase boundary, which is characterized by mismatch between adjacent domains at half unit cell dimension. Due to the partial lattice mismatch and associated electronic structure change, these antiphase boundaries could induce some exotic performance that differ from its constituent phase. Currently, the exploration of phase boundaries in diverse oxide functional materials encompasses a multitude of phenomena, including but not limited to, enhanced multiferroicity, magnetic interactions, and superconductivity15,16,17. These studies delve into the intricate interplay between structural transitions and the emergence of physical properties, offering profound insights into the fundamental mechanisms governing these materials. In perovskite ferro/piezo-electric oxides, the partial lattice mismatch induced local strain and chemical interface along vertical direction can effectively tune the polar behavior18,19,20. In oxide ferro/piezo-electric materials, the antiphase boundary encompasses various structural aspects, such as atomic arrangement, translational vector, and habit plane21,22,23. Previously, extensive researches have been conducted on the interplay between interface chemistry and the ordering of charged boundary polarity in ferroelectric materials, which significantly influences their overall properties and functionalities24. In lead-free NaNbO3 films, a giant and ultrahigh electromechanical response has been achieved via constructing phase boundaries4,25. However, the unavoidable leakage current will still deteriorate the ferroelectric performance of KNN-based materials, despite significant breakthroughs in the piezoelectric properties26. Whether this structural and chemical antiphase boundary has an optimization effect on the ferroelectric and leakage behavior of KNN-based films is a topic worthy of further investigating. Although there are many studies on the structural characteristic, formation mechanism and strain distribution of antiphase boundary in oxide ferroelectrics27,28, the detailed understanding of its effects on the micro ferroelectric domain switching dynamics and macro ferroelectricity is still elusive.

Herein, the epitaxial 2 wt% MnO2-modified (K0.49Na0.49Li0.02)(Ta0.2Nb0.8)O3 (KNNLT-M) ferroelectric films are fabricated on transparent (La0.03Sr0.97)SnO3 (LSSO)-coated SrTiO3 (STO) (001) substrates. It is demonstrated that these films exhibit stable ferroelectricity with a large 2Pr value of ~72.5 μC/cm2 and high degree of squareness of ~85% at a broad frequency range from 20 Hz to 10 kHz. The atomically resolved scanning transmission electron microscopy (STEM) images reveal that densely arranged antiphase boundaries are formed throughout the entire thickness of KNNLT-M films. These boundaries are grown along three crystal axes by half unit cell lattice mismatch. They are Mn-atomic enriched with A-site alkali ions deficiency at a nanoscale width of a single unit cell. The interfacial strain-polarization coupling along the antiphase boundary could contribute to its stable ferroelectricity with large polarization value and enhance its phase transition temperatures. Our results will help to the design of a high-performance KNN-based lead-free ferroelectric films, thus holding enormous application potential for eliminating toxic lead in the next-generation electronic devices.

Results and discussion

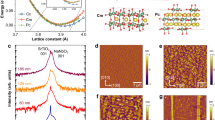

Electrical properties and optical transmittance measurements

Figure 1a shows the room temperature polarization-electric field (P-E) hysteresis loops of KNNLT-M films grown on the LSSO-coated STO (001) substrates, where squared shapes with a large polarization value are obtained. Accordingly, the P-E hysteresis loops of studied KNNLT-M films measured at 1 kHz shows a high degree of squareness [remnant polarization (Pr)/saturate polarization (Pmax)], although not completely saturated, of ~85% with a large 2Pr value of 72.5 μC/cm2 at 500 kV/cm. Based on the statistical analysis of the 2Pr values for both pure and doped KNN presented in Supplementary Fig. 1, the present polarization of studied KNNLT-M film surpasses that of the majority of state-of-the-art KNN-based films previously reported in the literature (see details in Supplementary Fig. 1). This is of great significance in KNN ferroelectric family, despite inferior to that in BiFeO3, BaTiO3 and PbTiO37,8,29. Strikingly, this polarization value can be maintained at a large frequency range as low as 20 Hz, and up to 10 kHz (Figs. 1d, 2a–i and Supplementary Fig. 2a, b). It is well known that Mn-doping is a common and effective method to suppress the leakage current in KNN system, improving its ferroelectric nature. The gaussian fitting in the high-resolution Mn 2p XPS spectra in Supplementary Fig. 3g indicate that Mn is at 2+ and 3+ state with Mn2+ dominantly exists over Mn3+ inside our KNNLT-M films. Here, the additional electron absorption by Mn4+ from MnO2 via reducing its valence to Mn3+/Mn2+ can effectively suppress the leakage current (Fig. 1c) and contribute the ferroelectricity of our KNNLT film. The high crystalline quality of KNNLT-M film, as identified by the small full width at half maximum (FWHM) of ~0.42° in Supplementary Fig. 4c, is also beneficial to optimize its leakage characteristics. We have further conducted measurements of leakage current curves for both pure and MnO2-doped KNNLT films (Supplementary Fig. 5) to verify the role of MnO2 in reducing leakage current. It is evident from the results that the magnitude of the leakage current decreases substantially with increasing MnO2 doping levels from 0.0 to 2.0 wt%. Meanwhile, the low deposition temperature and high growth oxygen pressure can inhibit the A-site element (K, Na, Li here) volatilization, which can also reduce the leakage current of our KNN-based film. In Fig. 1b, the acuter I-E peaks in the corresponding switching current curves indicate the fast ferroelectric domain switching with electric field excitation of the KNNLT-M film. Figure 1d shows the frequency-dependent P-E hysteresis loops of KNNLT-M films measured from 20 Hz to 10 kHz at a relatively high electric field it can endure, where it can be seen that the KNNLT-M film shows large 2Pr of ~72.5 μC/cm2 and 2Pmax of ~80.0 μC/cm2 at a wide frequency range as low as 20 Hz, and up to 10 kHz. Due to the short domain reverse time and domain movement resistance at higher test frequencies, the ferroelectric film needs a larger electrical field for achieving approximately the same domain reversal, thus resulting in the increased coercive electric field in Fig. 1d and Supplementary Fig. 2c. The frequency-dependent dielectric properties in Fig. 1e show that our KNNLT-M film has a high dielectric constant of 1200 at 1 kHz. This may be derived from the unanimous growth direction and good crystalline quality, as reflected by the low dielectric loss of ~0.1 at 1 kHz in Fig. 1e and small FWHM in Supplementary Fig. 4c. However, the irregular ferroelectric/electrode interfaces, the vacancies inside KNNLT-M film and time-dependent domain reversal process lead to a remarkable decrease of dielectric constant to the high frequency range. We have measured the frequency-dependent dielectric constant and loss of KNNLT-M films at an even lower test frequency of 40 Hz, as depicted in Supplementary Fig. 6. More encouragingly, the highly optical transmittance of ~75% from 400 nm to 2000 nm in Fig. 1f, approximately approaching to that of the Pb(Zr, Ti)O3 films and other lead-free ferroelectric films, endowing them with unlimited potential for applications in the opto-electronic devices.

a, b Room temperature P-E hysteresis loops and corresponding switching current curves measured at 1 kHz under various applied electric fields, c I-E curves, d frequency-dependent P-E hysteresis loops from 20 Hz to 10 kHz, e dielectric constant and loss from 1 kHz to 100 kHz, f and optical transmission spectrum at a wavelength range from 200 nm to 2000 nm of KNNLT-M films grown on the LSSO-coated STO (001) substrates.

Detailed frequency-dependent P-E hysteresis loop measurements

Figure 2a–i present the detailed frequency-dependent P-E hysteresis loops of studied KNNLT-M films grown on the LSSO-coated STO (001) substrates under various applied electric fields. As seen, our KNNLT-M films show stable ferroelectricity at a wide test frequency range from 20 Hz to 10 kHz. The saturated shapes and 2Pr - and 2Pmax - E curves extracted from Fig. 2 in Supplementary Fig. 2a, b can also demonstrate this situation, where both 2Pr and 2Pmax values tend to be a constant at this test frequency range. Among the measured frequencies, we compare the P-E hysteresis loops (Supplementary Fig. 7a-i) and corresponding switching current curves (Supplementary Fig. 7j–r) at the same electrical field of 200 kV/cm. The enlarged view of the comparative loops in Supplementary Fig. 7s show that the coercive electric field increase with increasing test frequency, which then again results in the reduced Pr and Pmax values. This is in good agreement with the theoretically calculation and consist with reported data in other ferroelectric families, examples included the perovskite ferroelectric Pb(Zr0.2Ti0.8)O330, molecular ferroelectric HQReO431, and multiferroic h-ErMnO332. Accordingly, the pure domain wall motion is a time-dependent process, the time-dependent kinetics of the domain wall determine the frequency-dependent polarization reversal at higher frequencies. Meanwhile, the domain movement usually suffers a certain resistance in ferroelectric materials. Such resistance increases with increasing the test frequency. On the other hand, some defects, such as oxygen vacancies and free charges, move well with applied electric field at low frequencies, but not at high frequencies, thus resulting in the reduced polarization. The slope reduction of the hysteresis loops (Supplementary Fig. 7a–i) and switching current curves (Supplementary Fig. 7j–r) with increasing test frequency can also demonstrate the slowing down of the domain reverse. Additionally, all the P-E hysteresis loops show slightly asymmetry along x-axis, indicating an internal bias field exist across KNNLT-M film. This phenomenon originates from the different work functions of the top (metal/oxide) and bottom (oxide/oxide) interfaces. Therefore, the stable ferroelectricity with large polarization in the wide frequency range suggest that KNN has great application potential in ferroelectric film devices, and provides experimental basis for replacing the lead-based ones.

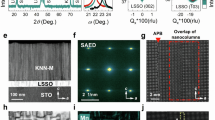

Microstructure and area elemental analysis

For epitaxial ferroelectric films, their properties are closely related to the nanostructure and internal strain. Previous studies have demonstrated that the isotropic tensile strain theoretically increases tetragonality (out-of-plane lattice constant/in-plane lattice constant) of perovskite oxides29,33. A large tetragonality is usually associated with a large dipolar moment in perovskite ferroelectric oxides, resulting in high polarization value34,35. The out-of-plane (in-plane) lattice constants of perovskite oxides can be calculated using the Bragg equation as λ/sinθ or through reciprocal space mapping (RSM) results as 3λ/2Qy(\(\bar{1}\)03) [-λ/2Qx(\(\bar{1}\)03)]. From the X-Ray diffraction results in Supplementary Fig. 4, we deduced that the KNNLT-M films exhibit normal broken-symmetry with a tetragonality of ~1.04. The perovskite structure of KNNLT-M films in Fig. 3d further confirms this tetragonality value. This moderate tetragonality is insufficient to induce substantial broken-symmetry or promote such large polarization obtained in our KNNLT-M films in Fig. 2. Therefore, we further characterized the microstructure of our KNNLT-M films. From the low-magnification cross-sectional STEM image in Fig. 3a, we found many vertically aligned nanostructures with a relatively smooth surface in the cross-sectional view of KNNLT-M films. In the enlarged view of the nanostructure region (Fig. 3b), as indicated by the red rectangle in Fig. 3a, we observed many extended vertical aligned nanostructures with flat nanostructure/matrix interfaces across KNNLT-M films. Remarkably, a misregistry offset occurs across the nanostructure regions, the lattice is shifted by absolutely half of a unit cell along out-of-plane direction. This situation can be more clearly distinguished from the locally enlarged image from the cyan rectangle in Fig. 3b, as identified by yellow and magenta dash lines in the atomically resolved images in Fig. 3b1 and b2. Meanwhile, we have also characterized the in-plane surface topography and atom arrangement of our films, where chessboard-like surface is detected in Fig. 3c. The in-plane atomically resolved image also shows the half unit cell misregistry offset along the in-plane [100] and [001] directions, as highlighted by yellow and magenta dash lines in Fig. 3c1. The detailed topography and atom arrangement along the in-plane direction on the surface of KNNLT-M films are shown in Supplementary Fig. 8a–d. Hence, the misregistry between the nanostructure regions and matrix inside KNNLT-M films can be seen as the special case of three-dimensional antiphase boundary21,23. The displacement vector in our KNNLT-M films can be described to be <a/2, c/2, b/2 > , where a, c and b are the unit vectors along both the in-plane and out-of-plane directions. The antiphase boundary between the nanostructure regions and normal perovskite matrix can usually induce local structural and polar heterogeneity. Between two neighboring antiphase domains, the lattice translation symmetry will be broken across each domain wall by shifting a vector of 1/2 unit cell. This lattice mismatch around the antiphase regions will facilitate the polarization rotation and domain wall motion under applied electric field, thus substantially improving ferroelectric polarization in our KNNLT-M films, as supported by experimental results in Fig. 2. Meanwhile, there will be epitaxial strain along the antiphase boundary in studied KNNLT-M films. The densely arranged nanostructure along the out-of-plane direction in our films can yield the clamped vertical stress. The strain-polarization coupling along the vertical antiphase boundary can vertically strain the KNNLT-M matrix, thus improving its polarization value. In 2020, Yao et al. have reported an in-plane antiphase boundary <a/2, b/2> and out-of-plane normal phase <δc> perovskite Na-deficient NaNbO3 nanostructure films (δc is an out-of-plane partial vector), achieving a giant piezoelectricity of 1098 pm/V4. On the basis of the above structural analysis and atomically resolved images in Fig. 3b1, b2 and c1, we constructed the schematic structural diagrams along both the out-of-plane and in-plane directions (Fig. 3b11, b12, b21 and c11). From Fig. 3c11, it can be seen that the formation and growth of in-plane antiphase boundary are strictly along the a- and c-axis (wine arrows). The schematic structural diagrams in Fig. 3b11, b12 and b21 illustrate the formation and growth of antiphase boundary along three crystal axes by half unit cell lattice mismatch, resulting in the atom overlapping in Fig. b1, and clear atom image in Fig. b2.

a The low-magnification cross-sectional STEM image, b the enlarged view of the out-of-plane nanostructure region, c in-plane surface topography, d and normal perovskite structure of KNNLT-M films grown on the LSSO-coated STO (001) substrates. b1, b2 The corresponding high-magnification out-of-plane, c1 and in-plane atomically resolved images enlarged from (b, c). The proposed schematic structural diagrams of the antiphase boundary formation along both the (b11, b12 and b21) out-of-plane and (c11) in-plane directions.

To identify the structural and chemical state along the antiphase boundary, the EDS was conducted along the out-of-plane and in-plane directions of the nanostructured KNNLT-M films, as the test areas were shown in Fig. 4a, e. The corresponding EDS maps of Mn, K, Na are displayed in Fig. 4b–d and f–h, respectively. From the EDS results, it can be seen that a distinct element separation occurs in our KNNLT-M films, in which almost all Mn elements are concentrated along the antiphase boundary region (Fig. 4b, f). In Mn-doped KNN-based films, the function and occupancy (A- or B- site) of Mn have long been debated. Previous studies have demonstrated that the Mn-doping can effectively suppress the leakage current and improve the ferroelectric nature of KNN-based materials5, which has also been discussed in Fig. 1 and Supplementary Fig. 5. However, the occupancy of Mn in KNN-based film has always been controversial. Here, from the EDS maps of A-site elements of K and Na along the out-of-plane (Fig. 4c, d) and in-plane directions (Fig. 4g, h), it is found that the Mn-enriched areas are usually accompanied by K and Na element depletions. The distribution of Na element is much diffused along the antiphase boundary, which can be attributed to the different thermodynamics and kinetics of K and Na in KNN-based materials36. Therefore, it can be speculated that the Mn element plays a crucial role in forming the antiphase boundary, and occupy the A-site positions in our KNNLT-M films. These Mn2+/Mn3+-enriched and densely arranged antiphase boundaries can equilibrate the charges induced by the A-site alkali ions deficiency. As a result, the lattice mismatch (strain) and element segregation (charge equilibration) along the antiphase boundary could induce local structural and polar heterogeneity, and suppress the leakage current of KNNLT-M films. Previously, the in-plane antiphase boundary was also found in Na-deficient NaNbO3 nanopillar films, where nanoscale domains with local structural and polar heterogeneity are formed and obtained a giant piezoelectric coefficient of 1098 pm/V4. These results indicate that the Na element also promotes the antiphase boundary formation, which will facilitate the polarization rotation and domain wall motion, thus promoting its stable ferroelectricity and large polarization in our KNNLT-M films. The XPS characterization of Nb 3 d and Ta 4 f in Supplementary Fig. 3d, e indicate that both elements are at valance state of 5+ and occupy the B-site in our KNNLT-M films37,38. According to the EDS maps of Nb, Ta and O in Supplementary Fig. 9b–d and 9f–h, no obvious morphological correlation between the B-site element distribution and the antiphase boundary. Combined with the structural characterization in Fig. 3 and element distribution analysis in Fig. 4, the nanostructures inside KNNLT-M films can be inferred as three-dimensional nano-grids. The width of the antiphase boundary is usually around the nanoscale of a single unit cell. The antiphase boundary is flat and clear, and strictly extends along the three crystal axes of [100], [001] and [010], forming the Mn-enriched three-dimensional nano-grids through the entire thickness of the KNNLT-M films as thick as 350 nm.

To investigate the relationship between ferroelectricity and the scale and distribution of antiphase boundaries, we fabricate two additional groups of KNNLT-M films exhibiting significant differences in ferroelectric properties, achieved by growing them at higher temperatures. As illustrated in Fig. 5a–c, sample R corresponds to the researching KNNLT-M films with large polarization, which were grown at 660 °C. In contrast, sample N and sample L represent the KNNLT-M films growing at higher temperatures of 680 °C and 700 °C, respectively. These two groups of KNNLT-M films exhibit normal and leaky P-E hysteresis loops, as seen in Fig. 5b, c. The corresponding EDS maps of Mn element are provided below each P-E hysteresis loop. From Fig. 5a–f, it is evident that the ferroelectric properties of the KNNLT-M films are strongly influenced by the scale and distribution of the antiphase boundary. As observed in Fig. 5d–f, the sample R exhibit slight separation of the Mn element along the antiphase boundary. In contrast, the Mn element within both sample N and sample L demonstrates a more dispersed distribution along the antiphase boundary. These results demonstrate that the scale and distribution of the antiphase boundary plays a critical role in determining the ferroelectric performance of our KNNLT-M films.

a–c The P-E hysteresis loops of KNNLT-M film sample with large ferroelectricity (SR: deposited at 660 °C) and two other samples with normal and leakage ferroelectricity (SN: deposited at 680 °C, and SL: deposited at 700 °C) at 1 kHz. d–f The analysis of the corresponding Mn element in the above three samples.

Phase transition behavior

To identify the phase stability of KNNLT-M film, temperature-dependent dielectric constant and XRD were collected and summarized in Fig. 6a, b. Based on the phase transformation analysis in our previous works39,40, the abnormal peak of ~300 °C in Fig. 6a represents the ferroelectric orthorhombic and tetragonal (O + T) mixed phases to ferroelectric T phase transition temperature TMIX-T. The broad TMIX-T peak here indicate the gradual transition process of our KNNLT-M films, which was induced by the structural inhomogeneity above room temperature, or the diffusive O and T phase coexistence caused by three-dimensional epitaxial strain. At this measured temperature range, stable ferroelectric phase of KNNLT-M can be maintained up to 400 °C, and no other transition peak was detected in Fig. 6a, especially the Curie temperature (TC). Then we conduct the high-temperature XRD to determine the actual TC, with a test temperature up to 600 °C, as shown in Fig. 6b. For clarify, only the XRD results around KNNLT-M (020) and STO (002) diffraction region are shown. From the symmetry and intensity ratio of KNNLT-M (020) peaks, we can deduce that the O-phase is dominantly exist over the T phase from 25 °C to 300 °C. Then the KNNLT-M (002) peaks become symmetry with a sharp and narrow single (002) diffraction peaks. Notably, between 300 °C and 400 °C, the 2θ shifts to the higher diffraction angle with raising temperature, while no change of 2θ from 400 °C on. We then calculated the out-of-plane lattice constants of KNNLT-M and STO change as a function temperature in Fig. 6c, d. Two abnormal points around 300 °C and 400 °C are detected in Fig. 6c, which are denoted by TMIX-T and TC, respectively. Thus, the ferroelectric to ferroelectric structure transition TMIX-T in Fig. 6b, c sufficiently coincides with the variation of the temperature-dependent dielectric constant in Fig. 6a. The calculated out-of-plane lattice constants of STO change with temperature in Fig. 6d provide a basis for the accuracy of the lattice evolution of KNNLT-M, which is consistent with previously reported results6,41. For KNNLT-M bulk ceramic in our previous work, the O to T phase transition temperature is observed at ~65 °C with a TC of 320 °C42. Here, the densely arranged antiphase boundaries will stabilize the KNNLT-M matrix by introducing the interfacial stress along three axes, forcing it to maintain the ferroelectric O and T phase to an even higher temperature, thus resulting in the highly elevated TMIX-T of 300 °C and a higher TC of 400 °C.

a Temperature-dependent relative dielectric constant measured at 1 kHz, b and the high-temperature XRD linear scans around STO (002) of KNNLT-M film grown on LSSO-coated STO (001) substrates. c, d Temperature-dependent out-of-plane lattice constants calculated from (b) of KNNLT-M and STO, respectively.

In summary, the Mn-atomic-layered antiphase boundary induced stable ferroelectricity with large polarization is achieved in KNNLT-M ferroelectric films. These films show large 2Pr value of ~72.5 μC/cm2 and high degree of squareness of ~85% at a large frequency range as low as 20 Hz, and up to 10 kHz. These antiphase boundaries are Mn-atomic enriched with both A-site alkali ions deficiency at a nanoscale width of a single unit cell and grown along three crystal axes by half unit cell lattice mismatch throughout the entire thickness of the films. By equilibrating the interfacial charges and clamping the interfacial strain, these boundaries could facilitate the polarization rotation and domain wall motion, thus contributing to the stable ferroelectricity with a large polarization value (2Pr ~ 72.5 μC/cm2) and enhancing its phase transition temperature (TC ~ 400 °C). Our results will help to design a high-performance KNN-based lead-free ferroelectric films, showing its application potential for eliminating the toxic lead in the next-generation electronic devices.

Methods

The ceramic target fabrication and film growth

The ferroelectric KNNLT-M target was prepared via conventional ceramic processing technology42. The starting oxides, namely Li2CO3, Na2CO3, K2CO3, Nb2O5, Ta2O5, and MnO2 powders, were mixed in accordance with a stoichiometric ratio corresponding to the desired nominal composition. The resulting mixture was initially milled in ethanol for 24 hours to ensure homogeneity. Subsequently, the mixture was calcined at 900 °C for 4 hours and re-milled for another 24 hours to achieve optimal particle distribution. The synthesized powders were then compacted into disks with a diameter of ~20 mm under a pressure of 300 MPa via cold isostatic pressing. Finally, the compacts were sintered in air at 1100 °C for 2 hours to obtain the final ceramic target. The structural characterization of (002)/(200) peak splitting and intensity ratio of ~2:1 by X-ray diffraction in Supplementary Fig. 10 demonstrate the O-phase of this target43. The polycrystalline LSSO target was fabricated via a standard solid-state reaction44. The precursor oxide, namely La2O3, SrCO3, and SnO2 powders, were mixed in stoichiometric proportions and subjected to thorough grinding. Subsequently, the mixture was reacted in air at temperatures ranging from 1250 to 1400 °C for 48 hours, with intermediate grinding steps performed twice. The resulting powders were then uniaxially pressed into disc-shaped targets with a diameter of ~ 20 mm under a pressure of 30 MPa and sintered in air at 1450 °C for 24 hours. Utilizing a custom-designed pulsed laser deposition (PLD) system equipped with a KrF excimer laser (248 nm), operating at a repetition rate of 10 Hz and an energy density of 1.5 J/cm2, KNNLT-M films were deposited onto LSSO-coated STO (001) substrates. Throughout the deposition process, the target-substrate distance was maintained at 5.5 cm. To achieve optimal growth conditions, the LSSO buffer layer (60 nm) was deposited onto the STO (001) substrate under a substrate temperature of 740 °C and oxygen pressure of 15 Pa. Subsequently, the KNNLT-M layer (350 nm) was epitaxially grown above the LSSO layer at a substrate temperature of 660 °C and oxygen pressure of 40 Pa. Following in situ annealing for 15 min, the system was allowed to cool down to room temperature automatically. For electrical characterization, a circular Pt top electrode (φ = 200 µm, 30 nm thick) was fabricated on the surface of the KNNLT-M film via PLD under high-vacuum conditions ( ~ 10-4 Pa) at room temperature.

Structural and electrical characterization

The film heterostructure was structurally characterized using X-ray diffraction (XRD, X´Pert, PANalytical, Netherlands, Cu-Kα1 radiation), including the 2θ-ω linear scan, rocking curve and off-specular RSM. The optical transmittance spectra of the films were measured using a UV-visible spectrophotometer (Lambda 950, PerkinElmer, USA). The electrical performance of studied KNNLT-M film was conducted using radiant precision premier LC ferroelectric measurement system (Radiant Technologies Inc, USA), semiconductor characteristic analyzer system (Keithley, 4200 SCS, USA) and impedance analyzer (Agilent 4294 A, Agilent Technologies, Inc. USA). The microstructure and area elemental analysis of the film was carried out by STEM (JEM-AMR200F) with energy-dispersive X-ray spectroscopy (EDS). The chemical state of elements contained in KNNLT-M film were analyzed by X-ray photoelectron spectra (XPS, Axis Supra + , Kratos, Japan).

Reporting summary

Further information on research design is available in the Nature Portfolio Reporting Summary linked to this article.

Data availability

All data are available within the main text, the Supplementary Information file, and the Source Data files. Source data are provided with this paper.

References

Zhang, S., Xia, R. & Shrout, T. R. Lead-free piezoelectric ceramics vs. PZT? J. Electroceram. 19, 251–257 (2007).

Shrout, T. R. & Zhang, S. J. Lead-free piezoelectric ceramics: alternatives for PZT?. J. Electroceram. 19, 113–126 (2007).

Liu, W. & Ren, X. Large piezoelectric effect in Pb-free ceramics. Phys. Rev. Lett. 103, 257602 (2009).

Liu, H. et al. Giant piezoelectricity in oxide thin films with nanopillar structure. Science 369, 292–297 (2020).

Wu, J., Xiao, D. & Zhu, J. Potassium-sodium niobate lead-free piezoelectric materials: past, present, and future of phase boundaries. Chem. Rev. 115, 2559–2595 (2015).

Xu, L. et al. Robust ferroelectric properties in (K, Na)NbO3-based lead-free films via a self-assembled nanocomposite approach. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 12, 4616–4624 (2020).

Wang, Y. et al. Chemical-pressure-modulated BaTiO3 thin films with large spontaneous polarization and high Curie temperature. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 143, 6491–6497 (2021).

Zhang, J. X. et al. Microscopic origin of the giant ferroelectric polarization in tetragonal-like BiFeO3. Phys. Rev. Lett. 107, 147602 (2011).

Sharma, P. et al. Nonvolatile ferroelectric domain wall memory. Sci. Adv. 3, e1700512 (2017).

Ziegler, B., Martens, K., Giamarchi, T. & Paruch, P. Domain wall roughness in stripe phase BiFeO3 thin films. Phys. Rev. Lett. 111, 247604 (2013).

Yang, S. M., Kim, T. H., Yoon, J.-G. & Noh, T. W. Nanoscale observation of time-dependent domain wall pinning as the origin of polarization fatigue. Adv. Funct. Mater. 22, 2310–2317 (2012).

Barrozo, P. et al. Defect-enhanced polarization switching in the improper ferroelectric LuFeO3. Adv. Mater. 32, e2000508 (2020).

Gao, P. et al. Revealing the role of defects in ferroelectric switching with atomic resolution. Nat. Commun. 2, 591 (2011).

Gao, P. et al. Ferroelastic domain switching dynamics under electrical and mechanical excitations. Nat. Commun. 5, 3801 (2014).

Kumar, A. et al. Antisite defects stabilized by antiphase boundaries in YFeO3 thin films. Adv. Funct. Mater. 32, 2107017 (2022).

Gao, C. et al. Atomic origin of magnetic coupling of antiphase boundaries in magnetite thin films. J. Mater. Sci. Technol. 107, 92–99 (2022).

Huang, E. W. et al. Numerical evidence of fluctuating stripes in the normal state of high-Tc cuprate superconductors. Science 358, 1161–1164 (2017).

Waqar, M. et al. Origin of giant electric-field-induced strain in faulted alkali niobate films. Nat. Commun. 13, 3922 (2022).

Luo, J. et al. Monoclinic (K,Na)NbO3 ferroelectric phase in epitaxial films. Adv. Electron. Mater. 3, 1700226 (2017).

Martin, L. W. & Rappe, A. M. Thin-film ferroelectric materials and their applications. Nat. Rev. Mater. 2, 16087 (2016).

Wang, Z. et al. Designing antiphase boundaries by atomic control of heterointerfaces. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 115, 9485–9490 (2018).

Fu, Z. et al. Atomic reconfiguration among tri-state transition at ferroelectric/antiferroelectric phase boundaries in Pb(Zr,Ti)O3. Nat. Commun. 13, 1390 (2022).

Zurbuchen, M. A. et al. Morphology, structure, and nucleation of out-of-phase boundaries (OPBs) in epitaxial films of layered oxides. J. Mater. Res. 22, 1439–1471 (2007).

MacLaren, I. et al. Local stabilisation of polar order at charged antiphase boundaries in antiferroelectric (Bi0.85Nd0.15)(Ti0.1Fe0.9)O3. APL Mater. 1, 021102 (2013).

Lin, B. et al. Ultrahigh electromechanical response from competing ferroic orders. Nature 633, 798–803 (2024).

Ho, K.-T., Monteiro Diniz Reis, D. & Hiller, K. Resistance degradation in sputtered sodium potassium niobate thin films and its relationship to point defects. Appl. Phys. Lett. 121, 162902 (2022).

Wang, Y. Q., Liang, W. S., Petrov, P. K. & Alford, N. M. Antiphase boundaries in Ba0.75Sr0.25TiO3 epitaxial film grown on (001) LaAlO3 substrate. Appl. Phys. Lett. 98, 091910 (2011).

MacLaren, I. et al. Strain localization in thin films of Bi(Fe,Mn)O3 due to the formation of stepped Mn4+-rich antiphase boundaries. Nanoscale Res. Lett. 10, 407 (2015).

Zhang, L. et al. Giant polarization in super-tetragonal thin films through interphase strain. Science 361, 494–497 (2018).

Yang, S. M. et al. Ac dynamics of ferroelectric domains from an investigation of the frequency dependence of hysteresis loops. Phys. Rev. B 82, 174125 (2010).

Tang, Y. Y. et al. Visualization of room-temperature ferroelectricity and polarization rotation in the thin film of quinuclidinium perrhenate. Phys. Rev. Lett. 119, 207602 (2017).

Ruff, A. et al. Frequency dependent polarisation switching in h-ErMnO3. Appl. Phys. Lett. 112, 182908 (2018).

Tinte, S., Rabe, K. M. & Vanderbilt, D. Anomalous enhancement of tetragonality in PbTiO3 induced by negative pressure. Phys. Rev. B 68, 144105 (2003).

Béa, H. et al. Evidence for room-temperature multiferroicity in a compound with a giant axial ratio. Phys. Rev. Lett. 102, 217603 (2009).

Zeches, R. J. et al. A strain-driven morphotropic phase boundary in BiFeO3. Science 326, 977–980 (2009).

Amoruso, S. et al. High fluence visible and ultraviolet laser ablation of metallic targets. Appl. Surf. Sci. 127-129, 1017 (1998).

Özer, N., Barreto, T., Büyüklimanli, T. & Lamperta, C. M. Characterization of sol-gel deposited niobium pentoxide films for electrochromic devices. Sol. Energy Mater. Sol. Cells 36, 433–443 (1995).

Sponchia, G. et al. Ceramics of Ta-doping stabilized orthorhombic ZrO2 densified by spark plasma sintering and the effect of post-annealing in air. Scr. Mater. 130, 128–132 (2017).

Dai, S. et al. Anomalous lattice evolution-mediated electrical properties in transparent KNN-based lead-free ferroelectric films. Inorg. Chem. 61, 19399–19406 (2022).

Xu, L. et al. Tuning electrical properties and phase transitions through strain engineering in lead-free ferroelectric K0.5Na0.5NbO3-LiTaO3-CaZrO3 thin films. Appl. Phys. Lett. 115, 202901 (2019).

Li, C. et al. Phase transition behavior of BaTiO3 thin films using high-temperature x-ray diffraction. J. Appl. Phys. 86, 4555–4558 (1999).

Wang, K. et al. Temperature-insensitive (K,Na)NbO3-based lead-free piezoactuator ceramics. Adv. Funct. Mater. 23, 4079–4086 (2013).

Chen, F. et al. Intergranular stress induced phase transition in CaZrO3 modified KNN-based lead-free piezoelectrics. J. Am. Ceram. Soc. 98, 1372–1376 (2015).

Wang, H. F. et al. Transparent and conductive oxide films of the perovskite LaxSr1–xSnO3 (x ≤ 0.15): epitaxial growth and application for transparent heterostructures. J. Phys. D: Appl. Phys. 43, 035403 (2010).

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by the National Key Research and Development Program of China (Grant No. 2024YFA161101) (F.C.), National Natural Science Foundation of China (Grant No. 12374095) (F.C.), (Grant No. 12204005) (L.X.), (Grant No. 12074001) (Z.H.), (Grant No. 12104008) (K.H.), (Grant No. 12104002) (P.C.), the Basic Research Program of the Chinese Academy of Sciences Based on Major Scientific Infrastructures (Grant No. JZHKYPT-2021-08) (F.C.) and Anhui Provincial Major S&T Project (Grant No. s202305a12020005) (F.C.).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

L.X. and F.C. conceived and designed the study; F.-Z.Y. and K.W. fabricated the ceramic targets; Z.K. and B.Z. prepared the films; L.X.Z.K., B.Z. and X.W. carried out the electric testing; L.X., K.H. and P.C. performed X-ray diffraction and analyzed the data; C.L. prepared the TEM samples, performed S/TEM, EDS mapping and analyzed the data; L.X. perform the phase transition measurement and analyzed the data; L.X., W.W., F.-Z.Y., Z.H. and F.C. wrote and modified the manuscript; All authors discussed the results and revised the manuscript.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Peer review

Peer review information

Nature Communications thanks Valdirlei F. Freitas, and the other, anonymous, reviewer(s) for their contribution to the peer review of this work. A peer review file is available.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Source data

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Xu, L., Kong, Z., Zhu, B. et al. Mn-atomic-layered antiphase boundary enhanced ferroelectricity in KNN-based lead-free films. Nat Commun 16, 5907 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-025-61170-w

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-025-61170-w