Abstract

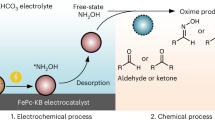

Oximes are crucial intermediates in the production of polymers and pharmaceuticals. Conventional synthesis methods, involving the hydrogenation of nitrogen oxides and nucleophilic addition of hydroxylamine to carbonyl compounds, are energy-intensive and hazardous. Here, we report an economical and sustainable electrosynthesis route to oximes using hydroxyl compounds and nitrate in an anode-cathode cascade electrolyzer. In this system, hydroxyl compounds are first dehydrogenated to ketones at a cobalt oxyhydroxide anode, followed by the subsequent co-reduction of ketones with nitrate at a Cu-substituted Fe3C cathode to form oximes. The cascade electrolyzer exhibits robust performance over 72 h at 2.8 V, achieving a high pyruvatoxime yield of 2.61 mmol cm–2 h–1 with a Faradaic efficiency of 101%. This versatile method accommodates diverse feedstocks, enabling the production of various relevant commodities. Process modeling and techno-economic analysis confirm the viability and cost-effectiveness of this innovative approach, offering a more sustainable pathway to essential chemical intermediates.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Oximes serve as crucial intermediates in the synthesis of organic nitrogen compounds such as amines, amides, N-containing heterocycles and amino compounds, which are used extensively across various fields including the materials and pharmaceutical industries1,2. Their unique properties, including dual nucleophilic sites at oxygen and nitrogen sites and an amphiphilic carbon, make them useful in diverse synthetic schemes, from cycloadditions to bioconjugation3,4. Oximes exhibit similarities to imines, such as the ability to convert to amines or isomerize, but offer greater stability, particularly against hydrolysis5. Conventional synthetic routes of oximes involve two main steps: (1) hydrogenation of nitrogen oxides (NOx) to hydroxylamine (NH2OH) using noble metal catalysts (e.g. Pt, Rh, Ru), followed by (2) the nucleophilic addition−elimination reaction of NH2OH with carbonyl compounds (e.g., aldehydes or ketones)6,7. However, these processes are complex and taxing in terms of energy and cost, and produces hazardous wastes. Moreover, the corrosive and explosive properties of synthetic precursors such as NH2OH and the reactive nature of carbonyl compounds introduced potential safety risks8. Therefore, there is a need to identify economical and sustainable routes by using safe feedstocks with low costs.

Electrochemical C-N coupling using organic chemicals and nitrates is highly attractive, especially in view of the fact that nitrates are industrial waste products. However, intersectional control for simultaneous oxidation of organic chemicals and reduction of nitrate (\({{{\rm{NO}}}}_{3}^{-}\)) is challenged by their differing kinetics and complex pathways9,10,11. To date, all reported works for electrosynthesis of oxime from \({{{\rm{NO}}}}_{3}^{-}\) are based on the expensive feedstocks of aldehydes or ketones, which are unstable in aqueous phase12,13,14,15,16. The artificial decomposition of biomass such as glycerol, sugars, and cellulose has been promulgated as green and sustainable routes for producing organic chemicals17,18. Among the derivatives, hydroxyl compounds have been produced on a large scale from biomass19,20. The electrosynthesis of oximes from hydroxyl compounds and NOx presents a promising alternative, potentially deceasing energy consumption, shortens reaction steps, and reduces the production of waste byproduct. This also improves safety by circumventing the use of explosive NH2OH and unstable carbonyl compounds. Despite its advantages, this approach remains relatively unexplored, particularly in the context of cost-effective and clean electrochemical technologies.

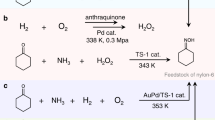

Traditional methods for oxime synthesis often depend on noble metal catalysts and multi-step purification under stringent conditions, yet they remain plagued by limited selectivity and environmental pollutants, as shown in Fig. 113,21,22. Although recent advances in electrochemistry have enabled oxime production via the co-reduction of ketones and nitrogen species10,11,13,23,24,25,26, key challenges persist. These include the need for energy-intensive dehydrogenation pretreatments to generate unstable feedstocks, inefficient oxygen evolution kinetics at the anode, and costly downstream separation processes. To address these limitations, we present an anode-cathode (A-C) cascade flow electrolyzer that co-upgrades biomass-derived lactic acid (LA) and nitrate (\({{{\rm{NO}}}}_{3}^{-}\)) into value-added oximes.

Using LA, a widely available, renewable platform chemical, as a model substrate, our system directly synthesizes pyruvatoxime (POXM), a critical precursor for alanine production and a key component in industrial protein synthesis. The global market for alanine, driven by its applications in food, pharmaceuticals, and agriculture, is forecasted to exceed $1.13 billion by 203027. Beyond LA, this cascade electrolysis platform demonstrates versatility in producing diverse oximes, highlighting its potential for broader industrial adoption. By integrating feedstock conversion and product formation in a single electrochemical process, our approach eliminates the need for intermediate purification, enhances energy efficiency, and leverages sustainable biomass resources.

At the anode, hydroxyl dehydrogenation has a more favorable reaction potential than oxygen evolution28. Meanwhile, at the cathode, ketone and \({{{\rm{NO}}}}_{3}^{-}\) show a more positive theoretical reduction potential (0.39 V) compared with hydrogen evolution (0 V)29,30. Therefore, it can be expected that the full cell (Anode) hydroxyl dehydrogenation | |(Cathode) (ketone + \({{{\rm{NO}}}}_{3}^{-}\)) cascade flow electrolyzer will enjoy a lower overpotential than conventional electrolyzer paired with oxygen evolution reactions at the anode11,31. Furthermore, employing hydroxyl compounds confers notable economic and safety benefits compared with ketone compounds: their high global production reduces feedstock costs, while intrinsic high flash points and benign hazard classifications lower operational risks and regulatory burdens32,33,34. Therefore, our cascade design can offer a compelling advance in selective, safe, and cost-efficient oxime synthesis.

In our electrolyzer system, we utilized a cobalt oxyhydroxide (CoOOH) nanosheet array-on-nickel foam (CoOOH/NF) as the anode for hydroxyl dehydrogenation, and a Cu-substituted Fe3C (Cusub/Fe3C) matrix-coated carbon paper as the cathode for the co-reduction of ketone and \({{{\rm{NO}}}}_{3}^{-}\). We investigated the efficiency of these electrocatalysts separately in an H-cell configuration and subsequently evaluated their performance in a coupled electrolyzer for the electrosynthesis of POXM from LA and \({{{\rm{NO}}}}_{3}^{-}\). We conducted experiments in the anode and cathode compartments, followed by the implementation of an A-C cascade flow electrolyzer. The objective was to achieve the synthesis of POXM with high yield and stability. The system’s stability was validated over a 72-h period, with an average yield of 2.61 mmol cm−2 h−1 of POXM at 2.8 V, reaching an outlet concentration of 87 mM POXM at the flow rate of 0.5 mL cm−2 min−1. To illustrate the versatility and commercial relevance of the electrolyzer, we also synthesized other oxime compounds, including acetone oxime (AO), methyl-ethyl-ketoxime (MEKO), and cyclohexanone oxime (CHXO), which are in demand as corrosion inhibitors, anti-skinning agents for paints, and polymer synthesis precursors, respectively. To assess the technical and economic viability of this process, we performed process modeling and conducted a comprehensive techno-economic analysis. The results demonstrated the feasibility of the proposed cascade electrolyzer and its economy of scale.

Results

Electrochemical dehydrogenation of lactic acid to pyruvic acid

In the electrosynthesis of POXM from LA and \({{{\rm{NO}}}}_{3}^{-}\), the hydroxyl compound LA was first converted to pyruvic acid (PA) at the anode, the latter diffuses from the anode to the cathode, facilitating the C-N coupling process towards POXM35. Therefore, the initial challenge is achieving high conversion in the selective electrochemical dehydrogenation of LA to PA at anode, which is the pre-requisite to ensure a sufficient concentration of PA for PA + \({{{\rm{NO}}}}_{3}^{-}\) co-reduction at cathode. Previous study reveals that transition metal such as Fe, Ni, Pd, Pt have high catalytic activities for the dehydrogenation of LA to PA22,36. Thus, we screened catalysts based on the various hydroxyl oxides of transition metal with and without noble metal loading. All the catalysts were prepared by electrodeposition method in one-pot cell and tested in the gasket H-cell. We found that CoOOH showed the highest yield and selectivity to PA, avoiding the unwanted C-C cleavage of LA (comparison in Fig. 2a and Supplementary Fig. 1). XPS verified that the cobalt exists as +3 oxidation state, with peaks at 794.5, 779.5, and 529.0 eV, attributing Co3+ (2p1/2), Co3+ (2p3/2), and Co-O, respectively (Supplementary Fig. 2b, c)37,38. In the SEM images (Supplementary Fig. 3), the nanosheet array of CoOOH/NF (cobalt oxyhydroxide on nickel foam) were uniformly distributed and completely covered on the framework of nickel foam, and this is reflected by the negligible signal of Ni 2p in XPS (Supplementary Fig. 2d). As shown in Fig. 2b, the overpotential for the electrochemical dehydrogenation of LA on CoOOH/NF is lower than that of oxygen evolution reaction (OER), which translates to a lower energy consumption in the full cell electrolyzer. The ability to maintain >80% selectivity of LA to PA over a wide potential range of 1.0–1.6 V, accompanied by a high current density, demonstrates the feasibility of our approach, as depicted in Fig. 2c (calculation of Faradaic efficiency (FE) and yield are shown in Supplementary Fig. 4).

a Comparing the yield of the electrochemical dehydrogenation of LA to PA among different catalysts, including FeOOH, CoOOH, NiOOH, Pd/CoOOH, Pt/CoOOH, and Au/CoOOH. b LSV curves for OER (1 M KOH + 0.3 M KNO3) and LA dehydrogenation (1 M KOH + 0.3 M KNO3 + 0.2 M LA) and (c) Selectivity of various products at the potential from 1.0 to 2.0 V over CoOOH/NF catalyst. No iR correction was applied. Source data for Fig. 2 are provided as a Source Data file.

Electrochemical co-reduction of nitrate and pyruvic acid to pyruvatoxime

Attaining high selectivity for POXM in the co-reduction of PA and \({{{\rm{NO}}}}_{3}^{-}\) at the cathode is challenging because of competing side reactions, including the reduction of \({{{\rm{NO}}}}_{3}^{-}\) to ammonia/ammonium (\({{{\rm{NH}}}}_{3}/{{{\rm{NH}}}}_{4}^{+}\)) and the reduction of PA to LA. In previous research on oxime synthesis, the \({{{\rm{NO}}}}_{3}^{-}\) undergoes a stepwise deoxygenation process, progressing from *NO3 to *NO and further to hydrogenation intermediates such as *NH2OH39. The accumulated *NH2OH then spontaneously forms POXM through a nucleophilic addition-elimination mechanism. The nucleophilic nitrogen of *NH2OH attacks the electrophilic carbonyl carbon of PA to form a tetrahedral intermediate, which then undergoes dehydration to convert to POXM at a high reaction rate. To achieve high selectivity in POXM formation, it is crucial to prevent excessive hydrogenation of *NH2OH to \({{{\rm{NH}}}}_{3}/{{{\rm{NH}}}}_{4}^{+}\). Therefore, reducing the reduction rate of \({{{\rm{NO}}}}_{3}^{-}\) is essential to minimize unwanted side reactions, allowing for efficient C-N coupling and the selective formation of POXM.

Based on previous work, Fe-based catalysts are relatively mild in terms of hydrogenation and produces mainly *NH2OH during nitrate reduction25,26. Thus, Fe3C matrix was selected as the catalyst at the cathode, and it is modified for POXM electrosynthesis by Cu doping. We used modified sol-gel method to synthesize a series of Fe3C porous matrix with various Cu loading (0 to 7.64 wt%), which were coated on carbon fiber paper and directly used as electrode40,41. The Cu in Cu-doped Fe3C catalysts was quantified using inductively coupled plasma optical emission spectrometry (ICP-OES). The concentration of Cu was further corroborated by energy disperse spectroscopy (EDS, Supplementary Fig. 5). The crystal structure and morphology of the Cu-doped Fe3C were evaluated by X-ray diffraction (XRD, Fig. 3c), scanning electron microscope (SEM, Supplementary Fig. 6), aberration-corrected high-angle annular dark-field scanning transmission electron microscope (HADDF-STEM, Supplementary Fig. 7) and EDS mapping by STEM (Supplementary Fig. 8). These results showed that there was no Cu metal aggregation and distortion in crystal structure after doping with Cu. At higher Cu loading >19 wt% in Fe3C, the signal for Cu metal emerges in XRD, indicating metal aggregation (Fig. 3c). As characterized by X-ray photoelectron spectroscopy (XPS, Supplementary Fig. 9), multiple peaks located at 724.2 eV, 720.1 eV, 711.0 eV, and 707.4 eV were assigned to Fe2+ (2p1/2), Fe0 (2p1/2), Fe2+ (2p3/2) and Fe0 (2p3/2), respectively, and others were attributed to the satellite peak of Fe 2p42,43. In Fig. 3a, b, K-edge X-ray absorption near edge (XANES) and k3-weighted Fourier transform extended X-ray absorption fine structure (FT-EXAFS) spectra were recorded to reveal the oxidation states of Fe. The results indicate the main iron-containing species are Fe3C, which is consistent with XRD and XPS. The oxidation state and coordination structure of Cu in Cu/Fe3C were verified by XANES, XPS and FT-EXFAS. As shown in the XANES data in Fig. 3d, the energies of Cu state in Cu/Fe3C catalysts are much lower than that of CuO, but higher than that of Cu foil and similar with Cu2O, thus the oxidation state of Cu is assigned +1; such a state is present in Cu/Fe3C catalysts of different loadings (red: 3.92 wt%, and blue: 7.64 wt%), These results are also consistent with XPS of Cu 2p in Fig. 3f. Broad peaks located at 954.5 eV, 952.8 eV, 934.6 eV, and 933.0 eV were attributed to Cu2+ (2p1/2) (red peak), Cu+ (2p1/2) (blue peak), Cu2+ (2p3/2) (red peak) and Cu+ (2p3/2) (blue peak), along with the satellite peak44,45. FT-EXFAS (Fig. 3e) exhibited the different local environment of Cu/Fe3C with Cu foil, Cu2O, and CuO. It is worth noting that the local environment of Cu in Cu/Fe3C is compatible with the Fe in Cu/Fe3C as shown in Fig. 3b, e. This data evidenced the substitution of Fe by Cu in Cu/Fe3C (called Cusub/Fe3C).

a, d Fe and Cu K-edge XANES of various Cu loading on Fe3C catalysts, respectively. b, e FT-EXFAS of various Cu loading on Fe3C catalysts, respectively. c, f XRD and XPS. g LSV curves in the solution of 1 M KOH + 0.3 M KNO3 + 0.1 M PA. h Faradaic efficiency. i Yield of POXM and total current density. No iR correction was applied. Source data for Fig. 3 are provided as a Source Data file.

The experiments on co-reduction of PA and \({{{\rm{NO}}}}_{3}^{-}\) were performed in a customized H-cell in argon under ambient conditions. Linear scan voltammetry (LSV) in an electrolyte containing 1 M KOH, 0.3 M KNO3, and 0.1 M PA was used to evaluate the catalytic activity of Fe3C with various Cu loading. As shown in Fig. 3g, the current density of 3.92 wt% Cusub/Fe3C was highest among all the different catalyst loading, and also higher than that of pristine Fe3C and 18.9% Cu-coated metal/Fe3C, hence subsequent discussion will be based on this champion composition. As shown in Fig. 3h, i, we compared the FE and yield for POXM at the potential of –0.5 V vs. RHE. The 1H NMR peak positions of all the products are shown in the Supplementary Fig. 11. The FE and yield of POXM reaches maximum when Cu doping increases to 3.92 wt% and decreases beyond that.

The ratio of [\({{{\rm{NO}}}}_{3}^{-}\)]/[PA] was varied systematically to identify the optimal condition for producing POXM using 3.9 wt% Cusub/Fe3C in 1 M KOH + 0.3 M KNO3 (Supplementary Fig. 12a, b), where a moderate ratio of 3:1 of [\({{{\rm{NO}}}}_{3}^{-}\)]/[PA] was found to be the best. A high ratio of [\({{{\rm{NO}}}}_{3}^{-}\)]/[PA] leads to high selectivity for \({{{\rm{NH}}}}_{3}/{{{\rm{NH}}}}_{4}^{+}\) because *NH2OH was further reduced to \({{{\rm{NH}}}}_{3}/{{{\rm{NH}}}}_{4}^{+}\) on the surface owing to the limited diffusion rate of PA. On the other hand, a low ratio of [\({{{\rm{NO}}}}_{3}^{-}\)]/[PA] results in the direct reduction of LA. A high concentration of PA might compete with \({{{\rm{NO}}}}_{3}^{-}\) for active sites on the catalyst surface, suppressing *NH2OH production. Here withal, our discussion will be based on Cusub/Fe3C, which represents the champion catalyst composition that we have identified. The time-dependent experiments, as shown in the Supplementary Fig. 12c, d, demonstrate that sufficient selectivity and conversion (>90%) of PA can be achieved in one pass in the flow electrolyzer. The subsequent decrease in the FE of POXM is due to the decrease in PA concentration after successive conversion cycles.

The occurrence of C-N coupling was verified by performing operando attenuated total reflectance surface-enhanced infrared absorption spectroscopy (ATR-SEIRAS). Supplementary Fig. 13a show the distinct signals of C-N coupling at 1102 cm−1, 1429 cm−1 and 1666 cm−1 of 3.92 wt% Cusub/Fe3C compared with pristine Fe3C46,47. In contrast, the signal of *NH2OH in pristine Fe3C is stronger than that of 3.92 wt% Cusub/Fe3C, implying the slower condensation of *NH2OH with PA on the pristine Fe3C than 3.92 wt% Cusub/Fe3C.

To gain insights into the role of Csub in the nucleophilic elimination of *NH2OH with PA, we analyzed the Gibbs energy pathways using density functional theory (DFT). We investigated the reactions involving the reduction of \({{{\rm{NO}}}}_{3}^{-}\) to NH3, \({{{\rm{NO}}}}_{3}^{-}\) to NH2OH, PA to LA, and PA + \({{{\rm{NO}}}}_{3}^{-}\) to POXM, considering both pristine Fe3C and Cusub/Fe3C catalyst models (as shown in Supplementary Fig. 14 and Supplementary Data 1). In Supplementary Fig. 13b, we observed a similar energy barrier for the conversion of \({{{\rm{NO}}}}_{3}^{-}\) to *NO2 on both pristine Fe3C and Cusub/Fe3C, indicating that the initial deoxygenation step of \({{{\rm{NO}}}}_{3}^{-}\) is a fast step on all catalysts. However, the ΔG (change in Gibbs energy) from LA to *LA was significantly higher for Cusub/Fe3C (−0.008 eV) compared to pristine Fe3C (−0.51 eV). This finding demonstrated that Cusub partially suppresses the direct reduction of PA to LA. Furthermore, the conversion of *NO to *NHOH on Cusub/Fe3C has a lower energy barrier (0.55 eV) compared to pristine Fe3C (0.97 eV). This indicates a faster rate of *NH2OH formation on Cusub/Fe3C. The adsorption energies of *NH2OH on pristine Fe3C and Cusub/Fe3C are 0.265 eV and 0.811 eV, respectively. Considering the instability of NH2OH in alkaline electrolyte, we propose that the condensation between *NH2OH and PA occurs predominantly on the Cusub/Fe3C surface rather than in the electrolyte. The energy barrier for POXM formation from the nucleophilic elimination of *NH2OH with PA on Cusub/Fe3C (0.44 eV) was significantly lower than that on pristine Fe3C (0.74 eV), suggesting a more rapid rate on Cusub/Fe3C. Therefore, Cusub is demonstrated to be an effective enhancer for the production of POXM in the Fe3C matrix.

(Anode) Hydroxyl dehydrogenation | |(Cathode) (ketone + \({{{\rm{NO}}}}_{3}^{-}\)) cascade flow electrolyzer

We employed a 2 × 2 cm2 flow electrolyzer with the electrode configuration of (anode) LA dehydrogenation | |(cathode) (PA + \({{{\rm{NO}}}}_{3}^{-}\)) to evaluate performance parameters such as selectivity, yield, and conversion at various cell voltages, as shown in Supplementary Fig. 15. FE calculations are also presented in Supplementary Fig. 16. CoOOH/NF and Cusub/Fe3C were employed as the anode and cathode materials, respectively. Taking into account the optimal concentration of reactants and the difference of electron transfer numbers between the anode and cathode reactions, we controlled the flow rates of the anode and cathode at 1- and 0.5-mL cm−2 min−1, respectively. This flow rate ensures a minimal conversion >20% among conditions tested. For LA to PA conversion or PA + \({{{\rm{NO}}}}_{3}^{-}\) co-reduction, the selectivity decreased if potential exceeded 3.0 V. This decrease can be attributed to the intense competition by side reactions such as oxygen evolution reaction (OER) at the anode and nitrate reduction with PA hydrogenation at the cathode. The optimal voltage for LA hydrogenation to PA was found to be 2.8 V, which resulted in the highest conversion (>60%) and yield (6.54 mmol cm−2 h−1). Besides, the cathode reaction maintained a yield of >2 mmol cm−2 h−1 and a conversion of >80% for the reaction of PA + \({{{\rm{NO}}}}_{3}^{-}\) co-reduction to POXM within the wide potential range of 2.4 to 3.6 V.

Next, we used an A-C cascade flow electrolyzer that connects anode output to cathode input directly for POXM electrosynthesis. The optimal operating potential was set at 2.8 V. As shown in Supplementary Fig. 18, the yield of POXM and conversion of LA increased with flow rate from 0.1 to 0.5 mL cm−2 min−1. At this flow range, the rate of LA dehydrogenation at anode increased with flow rate. At higher flow rate, the yield decreased due to the higher rate of reduction of *NH2OH to \({{{\rm{NH}}}}_{3}/{{{\rm{NH}}}}_{4}^{+}\) compared to the condensation reaction between *NH2OH with PA to form POXM. Supplementary Figs. 19, 20a shows the concentration of various products at various flow rates, wherein the flow rate of 0.5 mL cm−2 min−1 gave the highest yield of POXM. Therefore, we operate the flow electrolyzer at the optimal flow rate of 0.5 mL cm−2 min−1. The cascade flow electrolyzer remains stable for at least 72 h when operated at a potential of 2.8 V with a flow rate of 0.5 mL cm−2 min−1, giving an average yield 2.61 mmol cm−2 h−1 for POXM (Fig. 4a). The electrolyte at the outlet of cathode was analyzed at different intervals and the 1H NMR spectra are shown in Supplementary Figs. 20b, 21. These trends show that POXM formation is governed by the two-electron anodic LA to PA conversion. When PA is low in concentration, *NH2OH will be hydrogenated to \({{{\rm{NH}}}}_{3}/{{{\rm{NH}}}}_{4}^{+}\), reducing selectivity. Operating at 2.8 V and 0.5 mL cm−2 min−1 keeps the process in the anode-limited regime, thereby maximizing C–N coupling and sustaining high POXM output.

a Stability validation for over 3 days: current density and concentration of products at outlet at the potential of 2.8 V for LA to POXM. b Full current density at flow rate per area from 0.1 to 2 mL cm−2 min−1, c Faradaic efficiency of dehydrogenation, hydroxyl to oxime, and nitrate reduction, and (d) yield of oxime in co-upgrading lactic acid, isopropanol, 2-butaonl, and cyclohexanol with \({{{\rm{NO}}}}_{3}^{-}\) to their corresponding oxime. No iR correction was applied. Source data for Fig. 4 are provided as a Source Data file.

To demonstrate a wider scope of our electrolyzer, three common hydroxyl compounds, isopropanol (IPA), 2-butanol (2BU), and cyclohexanol (CHX) were reacted with nitrates in our cascade electrolyzer, where the corresponding oximes (Acetone oxime, 2-butanone oxime, and cyclohexanone oxime) can be produced, respectively. These hydroxyl compounds show similar electrochemical performance in cascade electrolyzer (Fig. 4b–d, and Supplementary Figs. 23–26) except for the slightly lower yield of cyclohexanone oxime due to the low solubility of CHX. It should be noted that a larger than 100% FE of oxime from hydroxyl in A-C cascade electrolyzer is possible because both anodic and cathodic reactions contribute to product formation with a single passage of current. In our system, the production of oxime involves 2 electrons transferred at the anode and 6 at the cathode, totaling 8 electrons per molecule, which corresponds to a theoretical maximum of FE of 133% for the whole electrolyzer (when FE of C-N coupling reach 100% at cathode). The additional FE beyond 100% arises from this paired electrolysis mechanism. The success of boarder conversion from hydroxyl to oxime demonstrates the universality of A-C cascade flow electrolyzer and their potential commercial prospect.

Process modelling and techno-economic analysis

To assess the techno-economic viability of the A-C cascade flow electrolyzer for co-upgrading LA and \({{{\rm{NO}}}}_{3}^{-}\) into POXM, we developed an integrated process model using Aspen Plus and MATLAB, encompassing the electrolyzer, distillation, stripping, extraction, and auxiliary units (Fig. 5a; see Methods Section for full design details). The model aligned operating conditions with experimental parameters from the cascade electrolyzer. A custom optimization framework dynamically adjusted separation parameters (e.g., flow rate) to achieve >95% POXM purity while minimizing energy use. This approach demonstrated robust performance: >99% of simulated cases met purity targets with low energy demand (Supplementary Fig. 27).

At a flow rate of 0.5 mL cm−2 min−1 (matching experimental conditions), the system produces 13.61 kilotons (kt) year−1 of POXM using 13.36 kt year−1 LA and 10.72 kt year−1 KNO3 (Fig. 5b). Economic analysis revealed a 20-year NPV of $193.69 million and a 5-year payout period (Fig. 6a and Supplementary Fig. 28a), driven by three factors: (1) High POXM yield with low electricity demand; (2) Efficient multi-stage separations; (3) Reduced separation energy due to high POXM concentration in the electrolyte outflow.

Comparison between the co-reduction and A-C cascade configuration: (a) NPV, (b, c) subdivided cost of POXM at the base scenario. d the distribution of levelized cost of POXM for orange: all the case in the bae scenario, blue: all the scenario in the base case. e global sensitivity analysis of CAPEX and OPEX, total production, and levelized cost of POXM via ten independent variables (flow rate, current density, cell voltage, FE of LA to PA at anode, FE of PA to POXM at cathode, electricity cost, cooling cost, steam cost, feedstock cost, and electrolyzer cost). GSA indices quantify the relative influence of input parameters on the variability of output. For example, a value of 0.5 implies that the input accounts for 50% of the variance in the output. Source data for Fig. 6 are provided as a Source Data file.

Notably, profitability hinges on POXM concentration in the electrolyte: lower flow rates resulted in negative NPVs. Compared to conventional oxime synthesis (which relies on costly ketones and unstable NH2OH), our electrolyzer enables one-step synthesis from abundant, stable feedstocks (alcohol acids and nitrates), widely available in biomass and industrial waste. With POXM market prices exceeding $1000 kg−1 (for >99% purity) and its derivative AL priced > $100 kg−1, our target production cost of $25 kg−1 (> 95% purity) positions the process as commercially competitive48,49.

The cascade configuration was benchmarked against a co-reduction approach using ketone and \({{{\rm{NO}}}}_{3}^{-}\) feedstocks. Under base-case conditions, the co-reduction system fails to achieve profitability, yielding a negative net present value (NPV) of –$75.69 million (Fig. 6a). In contrast, the cascade system significantly lowers production costs. In subdivided cost evaluation, POXM can be produced at the cost of $16.44 kg−1 via the cascade versus $24.01 kg−1 using co-reduction (Fig. 6b, c and Supplementary Fig. 30). This 48% cost reduction stems from three factors: (1) Use of low-cost feedstocks (hydroxyls instead of ketones). (2) Elimination of PA recovery steps. (3) Marginally lower electricity consumption.

The violin profile in Fig. 6d illustrates the distribution of the levelized cost of POXM for all performance cases under the base economic scenario (sandstone orange) and the experimental base case under all possible economic scenarios (sapphire blue, their parameters in Supplementary Tables 8, 9). The majority of the levelized costs of POXM under the base economic scenario range from $20 kg−1 to $30 kg−1 and can be controlled within $51.36 kg−1 for all situations, which is one order of magnitude lower than the current market price. The distribution of the levelized cost of POXM under all scenarios exhibits a small range of $14.22 kg−1 to $30.09 kg−1, demonstrating the economic robustness of the process in the face of fluctuating conditions. These distribution analyses of the levelized cost highlight the competitiveness and economic value of the A-C cascade flow electrolyzer technology.

A global sensitivity analysis (GSA) was performed to quantify the influence of key variables—including flow rate, FE of side reactions, and cost parameters—on process economics. Unlike local sensitivity methods that isolate single variables, GSA evaluates how simultaneous variations in input uncertainties propagate to output variances, offering a robust framework for prioritizing optimization targets and guiding development decisions50,51. Sensitivity indices were calculated via Fourier amplitude sensitivity testing (FAST), identifying the relative contributions of ten inputs: Electrolyzer parameters: Flow rate, current density, cell voltage, anode FE (LA-to-PA conversion), cathode FE (PA-to-POXM conversion). Economic factors: Electricity, cooling, steam, feedstock, and electrolyzer prices52. These inputs govern four outputs: equipment cost, utility cost, yield rate, and levelized cost.

As shown in Fig. 6e and Supplementary Fig. 31, flow rate overwhelmingly dominates sensitivity indices, particularly for equipment cost (index: 0.912). This highlights that prioritizing high flow rates without concurrent conversion efficiency improvements exacerbates material consumption, especially in downstream distillation. In contrast, electricity price exhibits negligible impact (indices <0.0001), reinforcing that purification, not energy supply, drives costs. With electrocatalytic performance already at practical levels, further enhancements are likely to yield limited incremental gains, underscoring the need to optimize separation processes. The anode FE (LA-to-PA conversion: 0.398) most significantly influences yield rate, underscoring the importance of optimizing upstream reaction efficiency in the cascade electrolyzer. While flow rate remains the most impactful parameter for levelized cost (index: 0.671), current density (0.138) and cathode FE (PA-to-POXM conversion: 0.036) also moderately affect costs. These results highlight flow rate as the key optimization target, provided that baseline current density and FE thresholds are maintained to ensure process stability.

Discussion

This study demonstrates the promising potential of electrochemical co-upgrading of hydroxyl and \({{{\rm{NO}}}}_{3}^{-}\) to produce oxime using an A-C cascade flow electrolyzer. Oxime compounds are highly valuable and versatile, and our new process shows potential for replacing conventional oxime synthesis methods. Operating the A-C cascade flow electrolyzer at a potential of 2.8 V and a flow rate of 0.5 mL cm−2 min−1, we achieved an average yield of 2.61 mmol cm−2 h−1 for pyruvatoxime during a 72-h stability validation period. In addition to producing POXM, we also explored the synthesis of other commercially relevant oxime compounds in our cascade electrolyzer, underscoring its versatility for broader applications. Our studies provide new routes for oxime production through the co-upgrading of biomass-derived hydroxyl compounds and \({{{\rm{NO}}}}_{3}^{-}\). Moreover, they offer insights into the conceptual design of the A-C cascade flow electrolyzer, with significant opportunities for optimizing conversion rates through further engineering, such as modifying the electrode areas to balance electron transfer rates between the cathode and anode. In summary, we demonstrate the A-C cascade flow electrolyzer as a viable platform for sustainable oxime production, with the potential for scalability and adaptability in industrial applications.

Methods

Sol-gel synthesis of Cusub/Fe3C as cathode

All chemicals were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich and used as received unless otherwise specified. Stoichiometric amount of Copper (II) Nitrate (Cu(NO3)2, 0.4 mmol for 3.92 wt% Cu loading) and 25 mmol citric acid was dissolved into 50 mL distilled water with over 1 h stirring for fully dispersing. Then, 10 mmol iron nitrate was added into the solution above under 3 h stirring to obtain the dark reddish solution. The color of solution changed to jade green after adding 9 mL 25 ~ 28 wt% ammonia. The 8 mL absolute ethanol was added after at least 1 h stirring. After overnight stirring, the jade-green solution was drop-casted onto the hydrophilic carbon paper (Air-pretreated at 500 oC for 2 h, Toray 060 carbon paper from Fuel Cell Store). The gel-encapsulated carbon paper was aged at quartz boat at 95 oC for 72 h to remove excess amount of water. The quartz boat with carbon paper was cured at 600 oC for 3 h with in Argon/H2 (95:5, 100 sccm) at 20 °C min−1 to convert Cu/Fegel into Cusub/Fe3C. A similar method was also employed to obtain black Cusub/Fe3C powder without using carbon paper.

Electrochemical deposition of CoOOH/NF and M-CoOOH/NF (M = Pd, Pt, Au) as anode

The nickel foam (300 × 400 × 1 mm) was used as matrix for growing Co(OH)2 nanosheets array. Initially, the nickel foam (300 × 400 × 1 mm) was sequentially washed with dilute HCl (2 M), ethanol, and deionized water (each for 10 min) to remove surficial oxides and contaminants. The electrochemical deposition of Co(OH)2 nanosheet array was carried out in a three-electrodes setup, using saturated KCl Ag/AgCl and Pt foil as reference and counter electrodes respectively. The growth of Co(OH)2 nanosheets was performed at constant potential ( −1.0 V vs. SCE) in aqueous Co(NO3)2 (0.3 M) electrolyte for 1200 s. The resulting Co(OH)2 nanosheet array was withdrawn and rinsed thoroughly with ethanol and distilled water. Pd, Pt, Au nanoparticles were deposited on Co(OH)2 by stepping the potential to −0.6 V vs. SCE for 10 s, followed by stepping back to −0.2 V vs. SCE for 10 s for three cycles, using aqueous electrolyte with 0.1 M NaCl and 5 mM HPdCl4, H2PtCl6, HAuCl4, respectively. The CoOOH and M-CoOOH were obtained from the as-prepared Co(OH)2 M-Co(OH)2 via a simple cyclic voltammetry (CV) method in a three-electrode configuration, using Ag/AgCl (with saturated KCl) and Pt foil as reference and counter electrodes respectively. The electrochemical oxidization process was performed at a scan rate of 100 mV s−1 from 0 V to 0.8 V vs. Ag/AgCl for ~40 cycles in 1 M KOH solution.

Electrochemical deposition of FeOOH/NF and NiOOH/NF

FeOOH/NF and NiOOH/NF were prepared via similar electrodeposition methods by using Fe(NO3)3 and Ni(NO3)2 instead of Co(NO3)2.

Material characterization

The following equipment were used: STEM-ADF (200 kV using JEOL ARM200F equipped with a cold field emission gun and ASCOR aberration corrector), EELS (200 kV by Gatan Quantum ER system with an exposure time of 40 s), EDS (200 kV by Oxford Aztec EDS system), TEM (FEI Titan, 200 kV), SEM (JEOL JSM-6701F), XPS (Thermo Fisher Scientific K-Alpha+, monochromatic Al Ka), XRD (Bruker D8), NMR (Bruker Advanced 500 MHz and 400 MHz), ICP-OES (Perkin Elmer Avio 500 ppm level accuracy), Electrochemistry (Ivium-n-Stat (sModule 5 A/10 V) and Autolab PGSTAT30 with current booster), Operando ATR-SEIRAS (Bruker Vertex 80), In-situ SERS (Horiba labRAM HR Evol). The X-ray absorption spectra (XAS) including X-ray absorption near-edge structure (XANES) and extended X-ray absorption fine structure (EXAFS) of the samples were collected at the Singapore Synchrotron Light Source (SSLS) center, where a pair of channel-cut Si (111) crystals was used in the monochromator. The storage ring was working at the energy of 700 MeV with average electron current of below 200 mA. Cu K-edge XAS: 50 mg of 3.92 wt% Cusub/Fe3C powder was finely ground with 150 mg boron nitride using a mortar and pestle before being pressed into a 10 mm pellet. Mo K-edge XAS: 20 mg of 3.92 wt% Cusub/Fe3C powder was ground with 150 mg boron nitride into a 10 mm pellet. Data analysis and simulation were carried out on Athena, Artemis, and Hephaestus (Version 0.9.26).

Electrochemical co-reduction of nitrate and pyruvic acid in a H-cell setup

Measurements were conducted in a customized gas-tight H-type glass cell separated by a Nafion NC700 membrane (Chemours). at room temperature (~24 °C) using an Ivium-n-Stat (sModule 5 A/10 V). A Hg/HgO reference electrode, a dimensionally stable anode (DSA, RuIr/TiO2 on Ti-mesh, 1 × 2 cm2) and working electrode (1 × 1 cm2) were used for a three-electrode system in an aqueous electrolyte containing 1 M KOH and 0.3 M KNO3 with various concentration of PA. Electrolyte solutions were prepared fresh immediately prior to use. Solutions prepared in advance were stored under refrigeration (e.g., at 4 °C) until required. LSV was conducted at 5 mV s−1. Chrono-amperometry (CA) was performed at constant potential at a stirring rate of 500 rpm. High-purity Ar was purged for 15 mins prior to the experiment. After 30 min reaction, 6 mL of catholyte (15 mL in total) was added into another glass vial containing 2 mL of 3 M H2SO4. 500 μL electrolyte in cathode chamber of H-cell were taken out and extra 500 μL new electrolyte was added every period of 10 min during time dependent experiment. The quantification of products from catholyte were determined by NMR. The reported current density was normalized to the geometric area of carbon paper without iR compensation. The potentials were recalculated into RHE by the formula ERHE = EHg/HgO + 0.0592 × pH + 0.197. No iR correction was applied to the electrochemical data presented in this study. All potentials are reported as measured, relative to the reference electrode. Unless otherwise specified, all key metrics of electrochemical performance and production quantification were determined from at least three independent measurements.

Electrochemical oxidation of lactic acid in a H-cell setup

Measurements were conducted (these tests were performed as single replicates) in a customized gas-tight H-type glass cell separated by a Nafion NC700 membrane (Chemours) at room temperature using an Ivium-n-Stat (sModule 5 A/10 V). A Hg/HgO reference electrode, a Pt mesh, (1.5 × 1.5 cm2) and working electrode (1 × 1 cm2) were used for a three-electrode system in an aqueous electrolyte containing 1 M KOH, and 0.2 M lactic acid. LSV was conducted at 5 mV s−1. CA was performed at constant potential at a stirring rate of 500 rpm. After 20 min reaction, 6 mL of catholyte (15 mL in total) was added into another glass vial containing 2 mL of 3 M H2SO4. The quantification of products from catholyte were determined NMR. The reported current density was normalized to the geometric area of carbon paper without iR compensation. The potentials were recalculated into RHE by the formula ERHE = EHg/HgO + 0.0592 × pH + 0.197.

Flow electrolyzer measurements for (anode) LA dehydrogenation | |(cathode) (PA + \({{{\rm{NO}}}}_{3}^{-}\))

Typically, one piece of Cusub/Fe3C on carbon paper (2 × 2 cm2) and CoOOH/NF were used as the cathode and anode, respectively. The flow electrolyzer (2 × 2 cm2) was assembled with two stainless-steel cover plates, two gold-coated copper plates as the current collector, two monopolar graphite plates with flow channel for electrolyte distribution, cathode, anode and a Nafion NC700 membrane (2.5 × 2.5 cm2, Chemours). The flow rate was controlled by two Watson Marlow 120S peristaltic pumps, and the actual flow rate was calibrated by a measuring cylinder. An aqueous electrolyte containing 1 M KOH, 0.3 M KNO3, and 0.1 M PA was supplied to the cathodic chamber at 0.5 min−1 cm−2 while the anode was flowed with 1 M KOH and 0.2 M lactic acid at 1 mL min−1 cm−2. Cell voltage was applied on the current collectors by an Autolab PGSTAT30 workstation with current booster which has maximum current of 10 A. Catholyte and anolyte were collected as respectively after a stable period of 30 min for each voltage ((typically 6 mL for each voltage)), and then mixed with 2 mL of 3 M H2SO4 to avoid the escape of ammonia and hydrolysis of oxime. Conversion and yield rate of all the products were monitored by NMR.

Anode-cathode cascade flow electrolyzer

As the same with above, one piece of Cusub/Fe3C on carbon paper (2 × 2 cm2) and CoOOH/NF were used as the cathode and anode, respectively. The flow cell was assembled with two stainless-steel cover plates, two gold-coated copper plates as the current collector, two monopolar graphite plates with flow channel for electrolyte distribution, cathode, anode and a Nafion NC700 membrane (2.5 × 2.5 cm2, Chemours). The flow rate was controlled by one Watson Marlow 120S peristaltic pumps at the inlet, and the actual flow rate was calibrated by a measuring cylinder. An aqueous electrolyte containing 1 M KOH, 0.3 M KNO3, and 0.2 M LA inlet with various flow rates of 0.1 to 2 min−1 cm−2 was supplied to anode. Electrolyte solutions can be prepared in advance, and stored under ambient condition. Cell voltage was applied on the current collectors by an Autolab PGSTAT30 workstation with current booster which has maximum current of 10 A (Supplementary Fig. 17). The output electrolyte at cathode outlet started to be collected after a period of 30 min for reaching to the steady state. The stability test was conducted for a continues operation over 3 days at the potential of 2.8 V with the flow rate of 0.5 min−1 cm−2. The output product was collected for each several hours and quantified by NMR. The long-term stability test was conducted once due to the extended duration of the experiment.

Product identification and quantification

All the organic liquid products were quantified using 1H NMR in water suppression mode. The internal standard solvent was prepared by diluting DMSO 100 times with water and then mixing with D2O with a 1:1 (V/V) ratio. 500 μL of the electrolyte after acidic treatment as above was added into 100 μL internal standard mixture for NMR test. The amount of the analyte (Supplementary Figs. 11, 22) was calculated based on the ratio of the area of the analyte peak (lactic acid, ~1.24 ppm, doublet peak, 3H; Pyruvic acid, ~2.29 ppm, singlet peak, 3H; pyruvatoxime, ~1.90 ppm, singlet peak, 3H; alanine, ~1.37 ppm, doublet peak, 3H; acetic acid, ~1.98 ppm, singlet peak, 3H; formic acid, ~8.06 ppm, singlet peak, 1H) to that of the internal standard (DMSO, ~2.55 ppm, single peak, 6H; more chemicals were supplemented in the caption of Supplementary Fig. 22). For identification and quantification of \({{{\rm{NH}}}}_{4}^{+}\) from electrolyte, the concentration was calculated based on the ratio of the area of the NH4+ peak (\({{{\rm{NH}}}}_{4}^{+}\), ~6.90 ppm, triplet peak) to that of DMSO using calibration curves (Supplementary Fig. 10).

The amount of produced organic product was calculated by the Eq. (1):

Then, the concentration and yield of organic product was calculated by the Eqs. (2, 3):

Considering the entire system involved electrochemical and chemical reaction meanwhile C-C cleavage exists, here we preferred to compare their selectivity according to the liquid products, although we calculated Faradaic efficiency as references:

Where m is the number of H atoms of the characteristic peak, d is the dilute ratio for acidic treatment, n is the mole of the produced organic product, V is the volume of the electrolyte, t is the reaction time, A is the electrode area, a is the electron transfer number, F is the Faraday constant, and Q is the total electron number in the system.

Electrochemical operando attenuated total reflectance surface-enhanced infrared absorption spectroscopy (ATR-SEIRAS)

The operando ATR-FTIR was performed on Bruker Vertex 80 with silicon as the prismatic window. First, catalysts ink (pure ethanol as the dispersant) was carefully dropped on the surface of the gold coated silicon prismatic, which surface was electrochemically activated before each experiment. Then, the deposited silicon prismatic served as the working electrode. The Pt foil and Hg/HgO electrode were used as the counter and reference electrodes, respectively. The 1 M KOH + 0.3 M KNO3 + 0.1 PA solution was employed as the electrolyte, which was pre-saturated with pure Ar. Spectra were recorded at intervals of 0.05 V with a continuous change in applied potential from 0.20 to −0.40 V versus RHE. The background spectrum of the catalyst electrode was acquired at an open-circuit voltage before each systemic measurement.

In situ electrochemical impendence spectroscopy (EIS) and distribution of relaxation time (DRT)

EIS was conducted at the applied potential of 1.2 to 2.0 V with flow rate of 0.5 mL cm−2 min−1, and 0.5 mL cm−2 min−1 at the flow rate of with the applied potential of 1.6 V. and a scanning frequency range between 100 kHz to 0.1 Hz at an amplitude of 0.01 V. The Gaussian-basis function DRT of EIS spectra was obtained by using a MATLAB® application DRTtools53. The relationship between the measured impedance and DRT is defined as54:

where Z is impedance, Rinf is series resistance, Rpol is total polarization resistance, Γ is DRT, τ is the relaxation time, and ω is angular frequency. The DRT parameters and classification were fixed as shown in Supplementary Table 155.

Computational simulation by density function theory

The first-principles calculations were performed with density functional theory (DFT) as implemented in Vienna ab-initio Simulation Package (VASP). The generalized gradient approximation (GGA) in the Perdew-Burke-Ernzerhof (PBE) format, the projector-augmented wave (PAW) method and a plane-wave basis with the kinetic cut-off energy of 450 eV is used are employed in all calculations. The (022) facet of Fe3C was selected as the proposed reaction facet. The Fe3C model contains 48 Fe atoms and 16 C atoms while there are 47 Fe atoms, 16 C atoms and 1 Cu atom in the Cusub/Fe3C model. The Fermi scheme was employed for electron occupancy with an energy smearing of 0.1 eV. The energy (converged to 1.0 ×10−5 eV atom−1) and force (converged to - 0.02 eV Å−1) were set as the convergence criterion for geometry optimization. A vacuum layer as large as 20 Å was used along the c direction normal to the surface to avoid periodic interactions. In all structural optimization calculations, all of the atoms were allowed to relax. Pristine Fe3C models were obtained by similar method.

Model development and techno-economic analysis

The process models in this study is developed by Aspen Plus V14 modeling environment according to experimental results. The non-random two-liquid model (ELECNRTL) is chosen as a physical properties package for all the process except extraction section. The extraction section is simulated based on another package, NRTL. Two cascade RStio Reactor block represents anode and cathode in the electrolyzer and RadFrac blocks are used for all the distillation process. Toluene is considered as the entrainer to extract organic chemicals with high boiling points (e.g., LA, PA, and POXM) from electrolyte56,57. Low pressure ammonia, referred to the previous work, is obtained by stripping58. Besides, acetate and formate are eliminated by hybrid-extraction-distillation process, as the reported work59. The power to electrolyzer for all the scenario use the same value of 10 MW, which generally referred for the electricity production by one PV farm (50 MW and 20% efficiency)60. After process model establishment, MATLAB is linked to Aspen Plus for optimizing the parameters to achieve the reasonable energy consumption and products outputs.

The purpose of the proposed scale is to bridge the gap between laboratory-scale experimentation and industrial applicability. In alignment with sustainable chemical production principles, we propose that all electricity consumption for the cascade electrolyzer be sourced from a 50 MW photovoltaic (PV) farm, with a solar capacity factor of 20%. The standard electricity price is assumed to be USD 0.10 per kWh. The effective energy output of the PV system is calculated as follows:

The area of cascade electrolyzer is determined based on the constant electricity supply from the photovoltaic system and the performance of our lab-scale electrolyzer, with reasonable uncertainty incorporated into the analysis. The parameters of the key blocks in Aspen Plus as shown in Supplementary Table 3. All the equipment exclude electrolyzer were evaluated by Aspen Economic Estimator with default setting, and utility costs are calculated by MATLAB according to the energy consumption in the process. Electrolyzer cost could be divided into several parts as stack, catalysts and membrane as the parameter in Supplementary Table 4. All the equipment cost estimation in the base case, were shown in Supplementary Table 5, and utility cost in the current scenario were provided as Supplementary Table 6. Other economic parameters of framework in the standard scenario were referred from previous literatures as shown in in Supplementary Table 760,61,62. Net present value (NPV) and levelized cost (LC) calculation was based on Supplementary Table 8 and the equations below:

The production cost exclusive of depreciation (CExcl.Dep..) included the feedstocks (nitrate, lactic acid, and water), utilities, labor-related operations, maintenance, operating overhead, property taxes and insurance, and general expenses.

The LC of POXM was calculated by NPV equals to zero.

This equation was solved by MATLAB function fsolve with the algorithm of Levenberg Marquardt.

Furthermore, global sensitivity analysis was conducted to reveal the impact from electrolyzer parameters and economic parameters to the concentration of product in the electrolyte, net present value and levelized cost. The range of economic parameters shown in Supplementary Table 9.

Data availability

All relevant data that support the conclusions drawn in this study are available within the Article and its Supplementary Information. Source data are provided with this paper. Additional data related to this paper may be requested from the authors. Source data are provided with this paper.

Code availability

All code related to this paper may be requested from the authors.

References

Rykaczewski, K. A., Wearing, E. R., Blackmun, D. E. & Schindler, C. S. Reactivity of oximes for diverse methodologies and synthetic applications. Nat. Synth. 1, 24–36 (2022).

Dhuguru J., Zviagin E., Skouta R. FDA-approved oximes and their significance in medicinal chemistry. 4, 66 (2022).

Kölmel, D. K. & Kool, E. T. Oximes and hydrazones in bioconjugation: mechanism and catalysis. Chem. Rev. 117, 10358–10376 (2017).

Li, B., Chen, J., Liu, D., Gridnev, I. D. & Zhang, W. Nickel-catalysed asymmetric hydrogenation of oximes. Nat. Chem. 14, 920–927 (2022).

Krylov, I. B., Paveliev, S. A., Budnikov, A. S. & Terent’ev, A. O. Oxime radicals: generation, properties and application in organic synthesis. Beilstein J. Org. Chem. 16, 1234–1276 (2020).

Mie Y., Katagai S., Mikami C. Electrochemical molecular conversion of α-keto acid to amino acid at a low overpotential using a nanoporous gold catalyst. 22, 9442 (2021).

Fukushima, T. & Yamauchi, M. Electrosynthesis of amino acids from biomass-derivable acids on titanium dioxide. Chem. Commun. 55, 14721–14724 (2019).

Wei, C., Rogers, W. J. & Mannan, M. S. Thermal decomposition hazard evaluation of hydroxylamine nitrate. J. Hazard. Mater. 130, 163–168 (2006).

Li, Y. et al. Sequential co-reduction of nitrate and carbon dioxide enables selective urea electrosynthesis. Nat. Commun. 15, 176 (2024).

Wu, J. et al. Integrated tandem electrochemical-chemical-electrochemical coupling of biomass and nitrate to sustainable alanine. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 62, e202311196 (2023).

Li M. et al. Electrosynthesis of amino acids from NO and α-keto acids using two decoupled flow reactors. Nat. Catal. 6, 906–915 (2023).

Chen W., et al. Catalyst selection over an electrochemical reductive coupling reaction toward direct electrosynthesis of oxime from NOx and aldehyde. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 146, 6294–6306 (2024).

Wu, Y. et al. Electrosynthesis of a nylon-6 precursor from cyclohexanone and nitrite under ambient conditions. Nat. Commun. 14, 3057 (2023).

Guzmán, M. I., Hildebrandt, L., Colussi, A. J. & Hoffmann, M. R. Cooperative hydration of pyruvic acid in ice. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 128, 10621–10624 (2006).

Greenzaid, P., Luz, Z. & Samuel, D. A nuclear magnetic resonance study of the reversible hydration of aliphatic aldehydes and ketones. i. Oxygen-17 and proton spectra and equilibrium constants. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 89, 749–756 (1967).

Wang, X.-G., Ajisafe, M. P., Fayad, E., Katouah, H. A. & Qin, H.-L. A Protocol For Hydrogenation Of Aldehydes And Ketones To Alcohols In Aqueous Media At Room Temperature In High Yields And Purity. (Organic & Biomolecular Chemistry, 2024).

Luo, Z. et al. Carbon–carbon bond cleavage for a lignin refinery. Nat. Chem. Eng. 1, 61–72 (2024).

Besson, M., Gallezot, P. & Pinel, C. Conversion of biomass into chemicals over metal catalysts. Chem. Rev. 114, 1827–1870 (2014).

Zhou, C.-H., Xia, X., Lin, C.-X., Tong, D.-S. & Beltramini, J. Catalytic conversion of lignocellulosic biomass to fine chemicals and fuels. Chem. Soc. Rev. 40, 5588–5617 (2011).

Li, Y. et al. Sustainable lactic acid production from lignocellulosic biomass. ACS Sustain. Chem. Eng. 9, 1341–1351 (2021).

Benson, R. E., Cairns, T. L. & Whitman, G. M. Synthesis of hydroxylamine. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 78, 4202–4205 (1956).

Mäki-Arvela, P., Simakova, I. L., Salmi, T. & Murzin, D. Y. Production of lactic acid/lactates from biomass and their catalytic transformations to commodities. Chem. Rev. 114, 1909–1971 (2014).

Li L. et al. Tandem dual-site PbCu electrocatalyst for high-rate and selective glycine synthesis at industrial current densities. Nano Letters, 24, 2392–2399 (2024).

Sharp, J. et al. Sustainable electrosynthesis of cyclohexanone oxime through nitrate reduction on a Zn–Cu alloy catalyst. ACS Catal. 14, 3287–3297 (2024).

Wu, Y. et al. Electrocatalytic synthesis of nylon-6 precursor at almost 100 % Yield. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 62, e202305491 (2023).

Xian, J. et al. Electrosynthesis of α-amino acids from NO and other NOx species over CoFe alloy-decorated self-standing carbon fiber membranes. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 62, e202306726 (2023).

Markets Ra. Alanine Market by End-User Industry, Application, Product Type - Global Forecast 2025-2030 (2024).

Holade, Y. et al. Recent advances in the electrooxidation of biomass-based organic molecules for energy, chemicals and hydrogen production. Catal. Sci. Technol. 10, 3071–3112 (2020).

Unden, G. & Bongaerts, J. Alternative respiratory pathways of Escherichia coli: energetics and transcriptional regulation in response to electron acceptors. Biochimica et. Biophysica Acta (BBA) - Bioenerg. 1320, 217–234 (1997).

Paidar, M., Roušar, I. & Bouzek, K. Electrochemical removal of nitrate ions in waste solutions after regeneration of ion exchange columns. J. Appl. Electrochem. 29, 611–617 (1999).

Shi, K., Si, D., Teng, X., Chen, L. & Shi, J. Pd/NiMoO4/NF electrocatalysts for the efficient and ultra-stable synthesis and electrolyte-assisted extraction of glycolate. Nat. Commun. 15, 2899 (2024).

Reinisch, J. & Klamt, A. Predicting flash points of pure compounds and mixtures with COSMO-RS. Ind. Eng. Chem. Res. 54, 12974–12980 (2015).

Gezae Daful, A. & Görgens, J. F. Techno-economic analysis and environmental impact assessment of lignocellulosic lactic acid production. Chem. Eng. Sci. 162, 53–65 (2017).

Park, S., Bailey, J. P., Pasman, H. J., Wang, Q. & El-Halwagi, M. M. Fast, easy-to-use, machine learning-developed models of prediction of flash point, heat of combustion, and lower and upper flammability limits for inherently safer design. Computers Chem. Eng. 155, 107524 (2021).

Wang, S. et al. Highly efficient one-pot electrosynthesis of oxime ethers from NOx over ultrafine MgO nanoparticles derived from Mg-based metal–organic frameworks. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. n/a, e202405553 (2024).

Tsujino, T., Ohigashi, S., Sugiyama, S., Kawashiro, K. & Hayashi, H. Oxidation of propylene glycol and lactic acid to pyruvic acid in aqueous phase catalyzed by lead-modified palladium-on-carbon and related systems. J. Mol. Catal. 71, 25–35 (1992).

Xiao, M. et al. Self-adaptive amorphous CoOxCly electrocatalyst for sustainable chlorine evolution in acidic brine. Nat. Commun. 14, 5356 (2023).

Zhang, X. et al. High-spin Co3+ in cobalt oxyhydroxide for efficient water oxidation. Nat. Commun. 15, 1383 (2024).

Jia, S. et al. Synthesis of hydroxylamine via ketone-mediated nitrate electroreduction. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 146, 10934–10942 (2024).

Hua, Z., Deng, Y., Li, K. & Yang, S. Low-density nanoporous iron foams synthesized by sol-gel autocombustion. Nanoscale Res. Lett. 7, 1–7 (2012).

Tappan, B. et al. Ultralow-density nanostructured metal foams: combustion synthesis, morphology, and composition. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 128, 6589–6594 (2006).

Hao, R. et al. Elucidation of the electrocatalytic activity origin of Fe3C species and application in the NOx full conversion to valuable ammonia. Chem. Eng. J. 467, 143371 (2023).

Liu, X. et al. Fe3C nanoparticles decorated 3D nitrogen-doped carbon foam as a highly efficient electrocatalyst for nitrate reduction to ammonia. J. Electroanalytical Chem. 933, 117295 (2023).

Hu, Q. et al. Ammonia electrosynthesis from nitrate using a ruthenium–copper cocatalyst system: a full concentration range study. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 146, 668–676 (2024).

Song, J. et al. Promoting dinuclear-type catalysis in Cu1–C3N4 single-atom catalysts. Adv. Mater. 34, 2204638 (2022).

Cheng, Y. et al. Highly efficient electrosynthesis of glycine over an atomically dispersed iron catalyst. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 146, 10084–10092 (2024).

Peng, O. et al. Swinging hydrogen evolution to nitrate reduction activity in molybdenum carbide by ruthenium doping. ACS Catal. 12, 15045–15055 (2022).

PharmCompass. Dl-Alanine | Price | per kg | USD. https://www.pharmacompass.com/price/dl-alanine (2025).

Alfa Chemistry. 2-(Hydroxyimino)-propanoic acid (CAS 2211-14-5). https://www.alfa-chemistry.com/cas_2211-14-5.htm (2024).

Cukier, R. I., Fortuin, C. M., Shuler, K. E., Petschek, A. G. & Schaibly, J. H. Study of the sensitivity of coupled reaction systems to uncertainties in rate coefficients. I Theory. J. Chem. Phys. 59, 3873–3878 (1973).

Cannavó, F. Sensitivity analysis for volcanic source modeling quality assessment and model selection. Computers Geosci. 44, 52–59 (2012).

Sobol, I. M. Global sensitivity indices for nonlinear mathematical models and their Monte Carlo estimates. Math. Computers Simul. 55, 271–280 (2001).

Liu, J. & Ciucci, F. The Gaussian process distribution of relaxation times: a machine learning tool for the analysis and prediction of electrochemical impedance spectroscopy data. Electrochim. Acta 331, 135316 (2020).

Avioz Cohen, G., Gelman, D. & Tsur, Y. Development of a typical distribution function of relaxation times model for polymer electrolyte membrane fuel cells and quantifying the resistance to proton conduction within the catalyst layer. J. Phys. Chem. C. 125, 11867–11874 (2021).

Wang, Y., Marchetti, B. & Zhou, X.-D. Call attention to using DRT and EIS to quantify the contributions of solid oxide cell components to the total impedance. Int. J. Hydrog. Energy 47, 35437–35448 (2022).

Pal, D., Keshav, A., Mazumdar, B., Kumar, A. & Uslu, H. Production and recovery of pyruvic acid: recent advances. J. Inst. Eng. (India): Ser. E 98, 165–175 (2017).

Yang Kong, Z., Yeh Lee, H. & Sunarso, J. The evolution of process design and control for ternary azeotropic separation: Recent advances in distillation and future directions. Sep. Purif. Technol. 284, 120292 (2022).

Hu, Q., Peng, O., Liu, J., Chen, D. & Loh, K. P. Low power consumption ammonia electrosynthesis using hydrogen-nitrate flow electrolyzer. ACS Energy Lett. 9, 2303–2309 (2024).

Ramdin, M. et al. Electroreduction of CO2/CO to C2 products: process modeling, downstream separation, system integration, and economic analysis. Ind. Eng. Chem. Res. 60, 17862–17880 (2021).

Na, J. et al. General technoeconomic analysis for electrochemical coproduction coupling carbon dioxide reduction with organic oxidation. Nat. Commun. 10, 5193 (2019).

Biegler, L. T., Grossmann, I. E., Westerberg, A. W. Systematic methods for chemical process design. Prentice Hall, Old Tappan, NJ (United States) (1997).

Seider W. D. et al. Product and Process Design Principles: Synthesis, Analysis, and Evaluation. (Wiley, 2020).

Acknowledgements

K.P.L. thanks funding from NUS Centre for Hydrogen Innovation grant CHI-P2022-01 and also NRF-PUB project CWR-2101-0032. This research is also supported by Shenzhen Science and Technology Program (grant no.20231115112954001), Guangdong-Hongkong-Macao Joint Laboratory for Photonic-Thermal-Electrical Energy Materials and Devices, Southern University of Science and Technology, Shenzhen 518055, China (No. 2019B121205001), and Guangdong Provincial Key Laboratory of Energy Materials for Electric Power, Southern University of Science and Technology, Shenzhen 518055, China (Grant No. 2018B030322001). This research used facilities in the Singapore Synchrotron Light Source. This research used facilities in the Singapore Synchrotron Light Source.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

O.P. and Q.H. contributed equally to this work. O.P. conceived the research, synthesized the materials, conducted catalytic performance measurement, and simulated the process modelling under the supervision of C.C. and K.P.L. Q.H. performed the DFT calculation. M.J. assisted in measuring the Operando ATR-SEIRAS; STEM was conducted by M.S.; XAS measurement and data analysis were conducted by S.X. XAS data analysis was also assisted by J.L., and B.L. supported information collection for TEA. The draft was written by O.P. and advised by C.C., and revised by K.P.L. All authors discussed and commented on the manuscript.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Peer review

Peer review information

Nature Communications thanks Magda Helena Barecka, and the other, anonymous, reviewer(s) for their contribution to the peer review of this work. A peer review file is available.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Source data

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Peng, O., Hu, Q., Jin, M. et al. Hydroxyl and nitrate co-upgrading to oxime via anode-cathode cascade electrolyzer. Nat Commun 16, 6145 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-025-61186-2

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-025-61186-2