Abstract

Coherent perfect absorption (CPA), or anti-lasing, has been so far inherently restricted to continuous wave scenarios, drastically restricting its applications to standard linear steady-state systems. However, future technologies based on enhanced light-matter interactions typically require the dynamic emission and absorption of pulses, as in ultrafast optics, frequency-comb technologies, or spiking neuromorphic networks. Here, we propose to extend the reach of anti-lasing to pulsed operation. We unveil the phenomenon of fast temporal anti-lasing, in which perfect absorption of photons occurs transiently over ultrashort time scales, creating fast absorption pulses associated with broadband absorption frequency combs. This is obtained by leveraging robust topological transitions occurring in a hysteretic scattering system, which is temporally modulated to loop near a CPA singularity. Our work evidences the interplay between intrinsic memory and topology in wave scattering, unveiling the rich physics of Floquet engineering through topological switching. We envision applications in spiking photonic networks with robust emission, routing and detection of spikes, which may form the basis for future analog neuromorphic hardware.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

In physics, winding or encircling is the fundamental concept allowing the distinction between topology and triviality1,2,3. For topological systems, winding is a property defined from a continuous mapping, from the circle to a parameter space in which the physical system undergoes a closed winding loop. When going through the loop, topological systems accumulate a quantized phase, allowing their topological classification based on an integer invariant or charge2,3,4,5,6,7,8,9,10,11. Conventionally, such loops have been generated using adiabatic linear mechanisms with no memory of their history, being mostly based on the quasistatic response of the system to an external control parameter, completing the loop at an arbitrary speed.

However, hysteretic systems can exhibit a different form of loop, whose shape depends strongly on the current and past driving amplitude and frequency. Such hysteretic behavior has recently gained significant attention due to its non-volatile character, which is crucial to neuromorphic systems, due to its dependence on previous time stages12,13,14,15. These methods have found applications in various fields, such as the development of memristors with pinched loops16,17,18,19,20 or photonics and nanoscale synapses for emulating learning and forgetting processes21,22,23,24. Although these hysteresis loops exist naturally, they have so far been restricted to real-valued responses, e.g. current-voltage characteristics, and therefore remained irrelevant to topological physics. On the other hand, considering the singular topology of scattering matrices5 may provide a way for hysteretic loops to be leveraged for controlling topological transitions and winding directions. Indeed, scattering matrix topology is based on encircling a singular point where the matrix has a zero determinant. Since this singularity is the well-known coherent perfect absorption (CPA) condition4,25,26,27,28, we surmise that introducing hysteresis in the realm of topological scattering may unveil fundamentally new effects such as fast non-volatile topological transitions accompanied by spiking-like CPA, that are only controlled by hysteretic dynamics.

This paper unveils the potential of topological hysteretic winding, demonstrating how magnetic hysteresis can be leveraged to control robust topological transitions that deeply influence the transient scattering of microwave photons, leading to fast temporal anti-lasing processes. We induce hysteretic winding loops in Floquet scattering systems made of circulators subject to time-modulated external magnetic fields, driving periodic topological transitions associated with transient singular scattering behavior. By tuning the modulation parameters, we are able to accumulate hysteretic winding charge over long times, and release it at a later stage depending on the temporal dynamics of the winding patterns. Very fast temporal coherent perfect absorption and wideband topological absorption frequency combs are observed experimentally. Our findings enrich the physics of CPA and other topological singularities, by extending them to the realm of temporal processes. We envision applications in devices leveraging the memory and robust spiking behavior of the topological scattering pulses that are emitted and absorbed in such systems.

Results

Concept of hysteretic winding

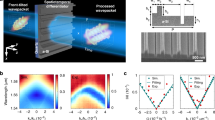

We begin by describing our experimental setup, depicted in Fig. 1a. A ferrite circulator, a fundamental nonreciprocal microwave device that transmits waves in a uni-rotational manner29, is subjected to periodic modulation using an external magnetic field whose voltage signal is generated by a function generator (see Supplementary Section I for the justification of using circulator as the basic scattering node). The circulator is made of a ferrite dielectric cavity that is biased by an internal permanent magnet (see Methods). As a consequence, when modulating sufficiently fast the external field, magnetic hysteresis will come into play and influence the scattering response through a modulation of the ferrite’s magnetic permeability30,31. The resultant hysteresis in the microwave scattering parameters is measured using a vector network analyzer, which is capable of recording in real time the evolution of the four scattering parameters between two circulator ports. These four parameters form the scattering matrix, which becomes singular when its determinant vanishes, a condition equivalent to CPA or anti-lasing. Figure 1b illustrates the concept of topological hysteretic winding around the CPA singularity. Generally, a complex-valued field can support topological defects in the form of zeros, around which the phase can wind3,28,32,33, corresponding here to the singularity condition \(\det (S)=0\)5, where we use the convention of scattering matrix with diagonal and off-diagonal elements being the reflection and transmission coefficients, respectively. For the time-modulated circulator, the topology is revealed in a 2D parameter space composed of the frequency detuning of the ferrite cavity Δf0 and the Zeeman splitting ΔZeeman, which are both controllable through the external magnetic modulation (see Supplementary Section I and II). Over one period Tm, a linear system would yield a non-hysteretic response (green path), for which the trajectory is the same when increasing and decreasing the control signal, with no possibility of winding. In contrast, in the case of hysteretic scattering, winding loops are formed due to magnetic hysteresis, as the scattering matrix undergoes a different path when increasing and decreasing the control signal. This effect, widely employed in magnetic memories, is used here in the context of topological scattering. In particular, when the hysteresis loop winds about the singularity \(\det (S)=0\), a phase accumulation of ±2π occurs within one driving period, resulting in a quantized accumulation of topological charge Q = ±1. We stress that this loop is made possible by temporal hysteresis, in stark contrast from conventional quasistatic winding mechanisms that do not feature any memory. This unique behavior offers exciting possibilities for the manipulation and control of transient wave scattering and topological properties. In Fig. 1c, we present the experimentally measured hysteretic winding behavior at 5 GHz. The complex value of \(\det (S)\) is mapped onto polar coordinate to conveniently visualize the winding loop and distinguish topological (and trivial) hysteretic winding based on encircling (or not) the origin of the plot. The driving period is Tm = 10 ms, its voltage modulation amplitude is 6 V, and a nontrivial winding is obtained by adding an offset voltage V0 = 3.5 V. Figure 1d highlights the accumulation of topological winding charge over a duration of 2 s, the accumulation rate being controlled by the modulation period. This shows that topological winding is very stable, and can be used as a basis for controlling the scattering, as we show in the following.

a Schematic of experimental setup. A ferrite-based nonreciprocal circulator is periodically modulated by an external magnetic field using a low-frequency function generator (sine wave with period Tm, modulation amplitude Vm, and DC bias V0). The magnetization hysteresis in the circulator ferrite translates to a hysteresis winding loop of the microwave scattering parameters, that can be measured with a vector network analyser. The third port of the circulator is matched. b Illustration of topological hysteretic winding. The scattering matrix topology is characterized by its determinant \(\det (S)\), whose evolution is plotted with phase (color) and magnitude (height) in the 2D parameter space of frequency detuning Δf0 and Zeeman splitting ΔZeeman. The singularity \(\det (S)=0\) corresponds to nonreciprocal coherent perfect absorption (CPA, marked by a star). Depending on the modulation speed and amplitude, one obtains either a non-hysteretic path, or hysteretic loops. Such loops can wind about the CPA point or not, with the winding number being defined from the total phase accumulation of \(\det (S)\) over a modulation period. c Experimentally measured trivial (V0 = 0 V) and topological (V0 = 3.5 V) hysteretic winding for microwave photon scattering at 5 GHz with Tm = 10 ms and Vm = 6 V. The complex value of \(\det (S)\) is mapped onto polar coordinates. d Experimental data showing the accumulation of the topological winding charge Q over 2 s at different modulation periods of Tm = 10, 2, 1 ms.

Asymmetric dual modulation

We now investigate ways to dynamically control this hysteretic behavior, the winding direction, and the associated topological transitions. We consider a setup where two circulators are cascaded, and subjected to close-by modulation periods and amplitudes denoted as Tm1,m2 and Vm1,m2, respectively (illustrated in Fig. 2a). The system still has only two scattering ports, the other ones being terminated by matched loads. This asymmetric dual modulation causes the hysteresis loop to move and deform across different temporal periods. Looking at the charge accumulation curves (Fig. 2b, c), we observe a key difference with the single circulator case, namely that topological transitions occur, due to the fact that the loop changes over a slow time scale. We observe two ways by which the topological charge of a loop can change, which we call path switch (Fig. 2b) and loop switch (Fig. 2c). In the path switch scenario, a single loop is involved, and its winding changes when one of its sides crosses the origin, collapsing the entire loop on the opposite side, before the other side crosses zero. This entire process results in a flipping of winding direction. The figure depicts snapshots of the winding loops at specific instants marked by arrowheads. As for the loop switch scenario, two counter-winding loops form an “8” shape, and these loops successively encircle the singularity, reversing the winding direction. Dynamic animations are provided in Supplementary Movies 1 and 2. We also note the possibility of loop switching with two nested loops, where one loop winds inside another one with opposite winding (see Supplementary Fig. S6 and Supplementary Movie 3). It’s noteworthy that under the adiabaticity assumption, the topological transition guarantees a singularity must occur somewhere within the interface, which is applicable in our temporal system: the modulation period is much smaller than the transition time. The rich dynamics of these loops presents unique opportunities for exploring transient topological scattering and switching, as we now demonstrate.

a Experimental setup for dynamic topological transitions. Two circulators interact through a bidirectional transmission line and are modulated at different periods Tm1,m2 or amplitudes Vm1,m2. Two of the ports are used for scattering measurements, while all other ports are left unexcited and matched. Multiple periods of winding loops are recorded over time, leading to the accumulated charge Q over time, and we observe two types of topological transitions. b Path switch topological transition, obtained for (1/Tm1, 1/Tm2) = (100, 100.1) Hz and Vm1 = Vm2 = 4 V. The loop crosses zero and collapse, before crossing zero again, flipping the winding direction. c, Loop switch topological transition, obtained for (1/Tm1, 1/Tm2) = (100, 100.1) Hz and (Vm1, Vm2) = (4, 2) V. Two counter-winding loops form an “8”-shaped path, also allowing for a topological transition. Insets show the corresponding winding loop at the arrowhead instant, and the stars mark the singularity of \(\det (S)=0\) in polar coordinates. Topological transitions occur when the color of the line changes.

Fast anti-lasing at transition

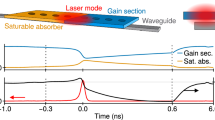

We can now harness these periodic topological transitions to enable very fast temporal anti-lasing, which must occur transiently at topological transitions. Indeed, the topological transition is equivalent to \(\det (S)=0\), which implies directly that a nonreciprocal CPA can be encountered periodically and transiently in situations like the one of Fig. 3a (see Supplementary Fig. S3 for the illustration of winding loops just before and after topological transitions). Since the eigenstate for a two-port non-reciprocal CPA is special and only involves excitation from one of the ports, we do not have to synchronize excitations at multiple ports to engage it, but simply send a single input wave (see Supplementary Section IV). We note this condition is not hard to realize since we have the nonreciprocal circulator at hand. It initially has a very large nonreciprocal ratio of around 20 dB, meaning the value of backscattering is considerably small compared to forward transmission. By introducing additional magnetic bias, the value of backscattering can be further tuned to closer to zero in experiments, corresponding to the condition of nearly perfect nonreciprocity. Under this condition, the measured total outgoing intensity is shown in Fig. 3b. We observe very deep and sharp absorption pulses (marked by stars), which precisely coincide with the topological transitions (Fig. 3b). Remarkably, the duration of these pulses is two orders of magnitude smaller than the modulation period (the minimum linewidth reaching ~ 0.003Tm), demonstrating the rapid character of the anti-lasing effect. The zoomed-in view of Fig. 3c compares, in log scale, the fast CPA pulses (starred) to conventional pulses obtained at instants when the loop approaches the CPA point without crossing it. The transition-enabled pulses are significantly faster and deeper, underscoring the pivotal role of topological transitions in achieving fast and efficient anti-lasing effects. To solidify our findings, we have monitored the outgoing power at port 2 and the power leakage at the matched ports. This measurement demonstrates that when the singularity is crossed, the signal incident at port 1 is indeed not transmitted to port 2, but is transiently absorbed by the matched ports. This means that the absorption of the anti-lasing pulses is not only due to losses in the ferrite cavity, but also to absorption in the terminations at the matched ports. It shows that both anti-lasing and lasing spikes coexist in the system, and could be leveraged in future applications. Digging deeper, power spectral density (PSD) spectrums of the outgoing intensity of Fig. 3b reveal intriguing frequency combs as a consequence of intrinsic hysteresis (Fig. 3e, f). For the anti-lasing pulses, the comb starts at the modulation frequency of 100 Hz and extends to multiple high harmonics beyond 2 kHz (Fig. 3e). This is in stark contrast with the case of trivial pulses, for which the PSD spectrum has only a few significant harmonic components (Fig. 3f). This implies that interplay between topological singularity and hysteretic transition strongly enhances harmonic generation, which is the mechanism underlying the generation of fast temporal pulses. This nonlinear behavior due to history-dependent scattering not only adds richness to the system’s response but also unlocks the potential for a diverse range of frequency components to participate in the transient pulse generation processes.

a Accumulated charge over time for the hysteretic winding of \(\det (S)\), obtained at the dual modulation condition around (1/Tm1, 1/Tm2) = (100, 100.4) Hz. At periodic time instants, the topology of the winding changes forcing the CPA condition to be encountered transiently. b Outgoing intensity when injecting the CPA eigenstate. The topological transitions manifest themselves as fast temporal anti-lasing pulses (marked by blue stars). c Zoomed-in view of one of the CPA peaks (curve marked by the blue star), which is compared to multiple no-transition trivial pulses observed over one driving period in the shaded region of b. d With excitation at port 1, plot of the measured outgoing intensity at port 2 and power leakage to the matched port. Power spectral density (PSD) of time-domain outgoing intensity (e) with topological transitions and f without transition.

Discussion

Besides typical modulation signals, it’s possible to construct more complex topological winding by controlling the modulation period and amplitude simultaneously. This provides more degrees of freedom of the hysteresis loops in the complex plane for topological winding and phase transition. Some examples are demonstrated in Supplementary Fig. S7. The hysteretic winding enriches conventional real-valued hysteresis effects, which are widely employed for in-memory computing and neuromorphic devices, with complex-valued scattering phenomena and nontrivial topology. This enhances the routing and detection of spikes with phase-transition assisted sensitivity and noise resilience with quantized topological charge. Also, recent research is conducted for edge-state computing by employing memorized quantized Hall conductance34, and our concept can be readily extended to networks with anomalous or Chern edge state in photonic regime showing topological protection in both spatial and time domains.

The demonstrated hysteretic topological winding presents nontriviality in both topology and encircling dynamics, enabling the accumulation of in-memory quantized charges. This feature holds great promise for the implementation of neuromorphic perception35,36 and computing37 within a topologically robust network capable of robust emission, routing and detection of spikes. It is important to note that topology is not limited to a CPA singularity; it also encompasses non-Hermitian braiding and other singularities such as exceptional points32,38 or scattering zeros, unveiling a wide range of topological winding charges and transition phenomena. The utilization of topological transitions now presents an opportunity to achieve fast and high-contrast switching in dynamic systems, that can actually be regarded as a previously unrecognized temporal topological interface39. This can provide a powerful tool for realizing efficient topological switches40. Furthermore, these concepts can be readily extended to acoustic, optical, thermal emission, and quantum systems using topological Floquet configurations. This work therefore opens up possibilities for exploring topological physics, in-memory computing, spiking photonic networks, and dynamic edge states in very diverse fields.

Methods

Experimental set-up

The circulator is a surface-mounted microwave circulator, designed from a Y-shaped strip line on a printed circuit board. The three ports are placed 120∘ apart from each other such that they are iso-spaced. The printed circuit board is sandwiched between two pieces of ferrite. Without magnetic fields, the Y-junction strip line supports two degenerate modes at f0: right and left-handed. To bias it, two internal magnets are fixed outside, providing the required magnetic field of 50 kA/m = 628 Oe, normal to the printed circuit board and polarizing the ferrite, therefore lifting the initial degeneracy, with chiral modes at f+ and f−. The electromagnet is placed above the circulator and a periodic modulation of the voltage signal is applied to the electromagnet (\(V(t)={V}_{0}+{V}_{m}\sin (2\pi t/{T}_{m})\)), generating a periodically modulated magnetic field normal to the circulator’s top surface. Two ports are connected to the vector network analyser (Rohde & Schwarz’s ZNA67) and all other ports are connected with match loads for measuring scattering parameter over time at 5 GHz. Power leakage is measured by replacing one matched port with a spectrum analyzer (tinySA Ultra). The accumulated charge is obtained through the phase of scattering-matrix determinant over time. Then it is unwrapped and divided by 2π.

Theoretical model

The numerical simulations of singular topology in circulators, topological hysteresis winding loop using magnetic hysteresis, and theory on nonreciprocal CPA eigenstate are provided in Supplementary Sections I–IV. They provide a quantitative validation of the observed experimental results presented in the main text.

Data availability

The data that support the findings of this study are available at https://doi.org/10.6084/m9.figshare.29053901.

Code availability

This study did not involve the development of a custom computer code.

References

Roe, J. Winding around: the winding number in topology, geometry, and analysis (American Mathematical Society Mathematics, 2016).

Kim, D., Baucour, A., Choi, Y.-S., Shin, J. & Seo, M.-K. Spontaneous generation and active manipulation of real-space optical vortices. Nature 611, 48–54 (2022).

Song, Q., Odeh, M., Zúñiga-Pérez, J., Kanté, B. & Genevet, P. Plasmonic topological metasurface by encircling an exceptional point. Science 373, 1133–1137 (2021).

Liu, M. et al. Spectral phase singularity and topological behavior in perfect absorption. Phys. Rev. B 107, L241403 (2023).

Guo, C., Li, J., Xiao, M. & Fan, S. Singular topology of scattering matrices. Phys. Rev. B 108, 155418 (2023).

Asbóth, J. K., Oroszlány, L. and Pályi, A. The Su-Schrieffer-Heeger (SSH) model. In A short course on topological insulators: band structure and edge states in one and two dimensions, 1–22 (Springer International Publishing, Cham, 2016).

Zhen, B., Hsu, C. W., Lu, L., Stone, A. D. & Soljačić, M. Topological nature of optical bound states in the continuum. Phys. Rev. Lett. 113, 257401 (2014).

Qin, H. et al. Disorder-assisted real-momentum topological photonic crystal. Nature 639, 602–608 (2025).

Qin, H. et al. Arbitrarily polarized bound states in the continuum with twisted photonic crystal slabs. Light Sci. Appl. 12, 66 (2023).

Ermolaev, G. et al. Topological phase singularities in atomically thin high-refractive-index materials. Nat. Commun. 13, 2049 (2022).

Thomas, P. A., Menghrajani, K. S. & Barnes, W. L. All-optical control of phase singularities using strong light-matter coupling. Nat. Commun. 13, 1809 (2022).

Hong, S., Auciello, O. & Wouters, D. editors. Emerging non-volatile memories (Springer, 2014).

Chen, A. A review of emerging non-volatile memory (NVM) technologies and applications. Solid State Electron. 125, 25–38 (2016).

Han, S.-T., Zhou, Y. & Roy, V. A. L. Towards the development of flexible non-volatile memories. Adv. Mater. 25, 5425–5449 (2013).

Youngblood, N., Ocampo, C. A. R., Pernice, W. H. P. & Bhaskaran, H. Integrated optical memristors. Nat. Photonics 17, 561–572 (2023).

Strukov, D. B., Snider, G. S., Stewart, D. R. & Williams, R. S. The missing memristor found. Nature 453, 80–83 (2008).

Spagnolo, M. et al. Experimental photonic quantum memristor. Nat. Photonics 16, 318–323 (2022).

Chua, L. If it’s pinched it’s a memristor. Semiconductor Sci. Technol. 29, 104001 (2014).

Kumar, S., Wang, X., Strachan, J. P., Yang, Y. & Lu, W. D. Dynamical memristors for higher-complexity neuromorphic computing. Nat. Rev. Mater. 7, 575–591 (2022).

Zhang, W. et al. Edge learning using a fully integrated neuro-inspired memristor chip. Science 381, 1205–1211 (2023).

Prezioso, M. et al. Spike-timing-dependent plasticity learning of coincidence detection with passively integrated memristive circuits. Nat. Commun. 9, 5311 (2018).

Zhu, C. et al. Optical synaptic devices with ultra-low power consumption for neuromorphic computing. Light Sci. Appl. 11, 337 (2022).

Cheng, Z., Ríos, C., Pernice, W. H. P., Wright, C. D. & Bhaskaran, H. On-chip photonic synapse. Sci. Adv. 3, e1700160 (2017).

Deng, W. et al. Organic molecular crystal-based photosynaptic devices for an artificial visual-perception system. NPG Asia Mater. 11, 1–9 (2019).

Chong, Y. D., Ge, L., Cao, H. & Stone, A. D. Coherent perfect absorbers: time-reversed lasers. Phys. Rev. Lett. 105, 053901 (2010).

Baranov, D. G., Krasnok, A., Shegai, T., Alù, A. & Chong, Y. Coherent perfect absorbers: linear control of light with light. Nat. Rev. Mater. 2, 17064 (2017).

Sakotic, Z. et al. Non-Hermitian control of topological scattering singularities emerging from bound states in the continuum. Laser Photonics Rev. 17, 2200308 (2023).

Ergoktas, M. S. et al. Localized thermal emission from topological interfaces. Science 384, 1122–1126 (2024).

Qin, H., Zhang, Z., Chen, Q., Zhang, Z. & Fleury, R. Anomalous-Chern steering of topological nonreciprocal guided waves. Adv. Mater. 36, 2401716 (2024).

Pozar, D. M. Microwave engineering, 4th ed. (John Wiley & Sons, Inc, 2012).

Liu, G.-G. et al. Topological Chern vectors in three-dimensional photonic crystals. Nature 609, 925–930 (2022).

Ergoktas, M. S. et al. Topological engineering of terahertz light using electrically tunable exceptional point singularities. Science 376, 184–188 (2022).

Liu, M. et al. Broadband mid-infrared non-reciprocal absorption using magnetized gradient epsilon-near-zero thin films. Nat. Mater. 22, 1196–1202 (2023).

Chen, M. et al. Selective and quasi-continuous switching of ferroelectric Chern insulator devices for neuromorphic computing. Nat. Nanotechnol. 19, 962–969 (2024).

Jiang, C. et al. Neuromorphic antennal sensory system. Nat. Commun. 15, 2109 (2024).

Baek, E. et al. Neuromorphic dendritic network computation with silent synapses for visual motion perception. Nat. Electron. 7, 454–465 (2024).

Goi, E., Zhang, Q., Chen, X., Luan, H. & Gu, M. Perspective on photonic memristive neuromorphic computing. PhotoniX 1, 3 (2020).

Ding, K., Fang, C. & Ma, G. Non-Hermitian topology and exceptional-point geometries. Nat. Rev. Phys. 4, 745–760 (2022).

Yin, S., Galiffi, E., Xu, G. & Alù, A. Scattering at Temporal Interfaces: An overview from an antennas and propagation engineering perspective. IEEE Antennas Propag. Mag. 65, 21–28 (2023).

Huang, K., Fu, H., Watanabe, K., Taniguchi, T. & Zhu, J. High-temperature quantum valley Hall effect with quantized resistance and a topological switch. Science 385, 657–661 (2024).

Acknowledgements

R.F. acknowledged the funding support from the Swiss State Secretariat for Education, Research and Innovation (SERI) under contract number MB22.00028.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

H.Q., Z.Z., and R.F. conceived this study. H.Q. and Z.Z. built the theoretical model, designed the experimental setup, performed the measurements and data analysis. J. W. provided technical support. All authors contributed to the writing of the paper. R.F. supervised this work.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Peer review

Peer review information

Nature Communications thanks Denis Baranov, Jan Wiersig, and the other, anonymous, reviewer(s) for their contribution to the peer review of this work. A peer review file is available.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Qin, H., Zhang, Z., Wang, J. et al. Topological hysteretic winding for temporal anti-lasing. Nat Commun 16, 6189 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-025-61282-3

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-025-61282-3