Abstract

Constructing three-dimensional covalent organic frameworks (3D COFs) remains a significant challenge compared to other areas of reticular chemistry. Most existing methods for constructing 3D COFs emphasize the necessity of at least one precursor being extended into 3D space. As a result, designing and synthesizing precursors with specific stereoconformations has become a dominant strategy for discovering new 3D COFs. In this study, we leverage the principle that the steric hindrance of intermediates during COF formation is inherently greater than that of the precursors. We demonstrate a strategy utilizing multinode porphyrin blocks with eight rotatable knots to create intermediates with steric hindrance-confined rigid stereoconformations, which can be viewed as active precursors for guiding 3D formation of COFs with high crystallinity. This approach paves an avenue to self-adaptive COF growth towards diverse 3D topologies that may circumvent obstacles for traditional precursor synthesis.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Three-dimensional covalent organic frameworks (3D COFs) possess unique porosity and superior mass adsorption as well as transport capabilities over their two-dimensional counterparts (2D COFs), making them attractive materials for applications in catalysis, separation, and molecular recognition1,2. However, the development of 3D COFs lags far behind 2D COFs and other 3D frameworks, largely hindered by bottlenecks in building block designs, synthesis and precise structure determination3,4,5. To overcome these obstacles, it is essential to continuously explore new precursors underlying 3D COF topologies and related physiochemical properties. Since the first example of 3D COFs brought by Yaghi et al. nearly two decades ago6, substantial advancements in this field have relied on polyhedral precursors, which can be categorized into three types: (1) tetrahedral precursors centered on carbon, silicon, adamantane, twisted biphenyl, woven units, etc.; (2) triangular prism-like precursors centered on cage or triptycene; and (3) twisted planar structure centered on benzene, biphenyl, pyrene and porphyrin7. The nodes of these inherently stereoscopic precursors lead to polymerization exclusively in three dimensions, thereby forming the 3D architecture of COFs. Recently, multinode planar precursors have also been exploited, though restricted to specific unit combinations or reactions. Examples include 3-connected triangular units and 4-connected square units for constructing ffc or tbo topologies8,9, 4-connected D4h units and 6-connected D3h units for constructing she topologies10, as well as bifunctional units carrying both boric acid and phosphoric acid groups for self-condensation into 8-connected polycubanes11. Up to date, the documented topologies of 3D COFs—including dia12, pts13, ctn6, bor6, lon14, lij15, qtz16, stp17, acs18 ceq19, hea20, pcu21, scu22, tty23, pcb24, she10, bcu25, flu26, rra27, srs28, nbo29, ffc8, tbo9, fjh30, pto31, mhq-z31, lnj7, sqc32 and alb-3,6-Ccc233—remain limited, indicating persistent and urgent need to expand the molecular repertoire and structural diversity of 3D COFs.

Formation of COFs is essentially a polymerization process guided by the geometry matching of monomers and the direction of covalent bonding34. The polymer backbone typically extends from rigid π-blocks possessing multiple reactive sites via successive condensation with organic linking units, yielding oligomeric intermediates in dynamic sizes, bond orientations and conformations toward thermodynamically stable COFs35. Therefore, it raises an intriguing question: Can the intermediates be pre-designed as self-adaptive precursors to guide the skeleton growth in a 3D manner according to the geometry-directed topology diagram? Here, since the steric hindrance of the intermediates formed during backbone extension must exceed that of the monomers, we can modify the node position of the planar precursors and the length of the linear linker. This adjustment allows us to alter the steric hindrance of the intermediates, influencing their conformation. When the intermediates adopt a more stereoscopic conformation, the successful formation of 3D COFs can be induced.

Results

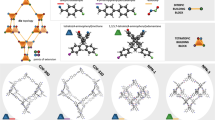

We synthesized a multinode porphyrin precursor, 5,5’,5”,5”’-(porphyrin-5,10,15,20-tetrayl)tetraisophthalaldehyde (TTP) (Supplementary Scheme 1), featuring eight aldehyde groups. Solvothermal condensation of TTP with p-phenylenediamine (PD), benzidine (BD), or 4,4”-diamino-p-terphenyl (TD) in a mixture of 1,2-dichlorobenzene (o-DCB), n-butanol (n-BuOH), and 6 M acetic acid (5:5:1 v/v/v) at 120 °C for 72 h yielded green powders designated as BNU-1, BNU-2 and BNU-3, respectively (Fig. 1a). Since the solvent type and composition significantly influence the crystallinity of COFs34, we took BNU-3 as an example to conduct crystallinity optimization experiments. The results revealed that when the volume ratio of o-DCB to n-BuOH was 1:1, the obtained BNU-3 exhibited the highest crystallinity (Supplementary Fig. 1). Imine linkages were confirmed using Fourier-transform infrared (FT-IR), reflected by the disappearance of the amine N–H stretching vibration band at 3390 cm−¹ and the aldehyde C=O stretching vibration band at 1697 cm−¹ for porphyrin, along with the emergence of the C=N stretching vibration band at 1622 cm−¹ (Supplementary Fig. 2)24. As shown by the solid-state ¹³C nuclear magnetic resonance (NMR) spectra of BNU-2 and BNU-3 (Supplementary Fig. 3), the characteristic peak at 157 ppm corresponds to the C=N linkages36, while the signals in the range of 100–150 ppm originate from the phenyl and porphyrin rings37,38,39. These results unambiguously confirm that the aldehyde and amine monomers are connected through imine bonds to form the COF frameworks.

a Schematic representation of the synthesis of 3D COFs featuring porphyrin knots connected by linear amino π-conjugated linkers via C=N bonds. TTP, 5,5’,5”,5”’-(porphyrin-5,10,15,20-tetrayl)tetraisophthalaldehyde. PD, p-phenylenediamine. BD, benzidine. TD, 4,4”-diamino-p-terphenyl. b Mechanistic diagram illustrating the role of steric effects of intermediates in regulating the formation of 3D COFs. Black rods indicate porphyrin precursors, while gray, blue, and red rods represent linkers of varying lengths. The molecule formed from the reaction of one porphyrin precursor with eight linkers is identified as an intermediate in the COF formation process, with three intermediates named TTP-8PD, TTP-8BD, and TTP-8TD.

According to our designed topology diagram (Fig. 1b), an intermediate for one TTP block and eight linkers with low steric hindrance could not generate a stable stereoconformation, more likely leading to a 2D ordered or disordered structure during the polycondensation process. Conversely, increased steric hindrance reinforces rotation of the meso C‒C bonds in porphyrins, thereby facilitating 3D extension at the eight nodes. To verify the pre-designed diagram, we assessed the crystallinity of BNU-1/2/3 by powder X-ray diffraction (PXRD) (Supplementary Fig. 4). BNU-1 exhibits a set of weak diffraction peaks at 6.54°, 9.32°, 10.40°, 14.04°, 16.94°, 19.18°, 23.70°, and 26.96°. BNU-2 displays a prominent diffraction peak at 3.82° and relatively weak peaks at 5.46°, 7.79°, 8.74°, and 11.65°. Similarly, we observed a strong peak at 3.17° and weak peaks at 4.39°, 7.33°, and 9.91° with BNU-3. Notably, the diffraction pattern of BNU-1 is markedly different from those of BNU-2/3, the latter causing significant diffractions in the low-angle region while the former shows negligible and scattered signals throughout the investigated region.

We employed computer modeling to clarify the COF structures by comparing the theoretical XRD patterns of BNU-1/2/3 models with the experimental data. Given the characteristics of the eight-node building blocks, we selected the pcb topology for structure refinement based on the Reticular Chemistry Structure Resource40, the Database of Zeolite Structures41 and existing literature24. We modeled both non-interpenetrated and 2-fold interpenetrated pcb topologies for BNU-1, BNU-2 and BNU-3 (Supplementary Figs. 5–10). As shown in Fig. 2a, the computed XRD pattern of the proposed 3D model of BNU-1 is completely inconsistent with the experimental XRD outcome, indicating that the TTP–PD intermediate size is too small to impose sufficient steric hindrance to facilitate the formation of a 3D COF. BNU-2 and BNU-3 display good agreement between the experimental XRD patterns and those of the 2-fold interpenetrated models (Fig. 2b, c), confirming that they are indeed 3D COFs in pcb topology. Rietveld refinement of the experimental PXRD patterns resulted in refined unit cell parameters of a = 36.09 Å, b = 30.62 Å, c = 26.29 Å, and α = β = γ = 90° for BNU-2, with Rp = 10% and Rwp = 8% (Fig. 3a–c). BNU-3 also belongs to the P1 space group, with unit cell parameters of a = 41.80 Å, b = 28.52 Å, c = 33.47 Å, and α = β = γ = 90°, yielding Rp = 8% and Rwp = 6% (Fig. 3d–f). Collectively, PXRD results demonstrate that BNU-1 is likely amorphous, whereas BNU-2/3 are 3D COFs with high crystallinity.

Given that COF growth must adhere to the geometry-confinement principle34, polycondensation of the TTP precursors with linear π-conjugated linkers (PD, BD and TD) would form COFs in well-reserved topology. Supplementary Fig. 11 illustrates the eight connection directions (a, b, c, d, e, f, g and h) in the plane of TTP, with the angles between each two directions being 30°. Density functional theory (DFT)-optimized TTP structure also confirmed its planar nature and the in-plane orientation of the eight aldehyde nodes (Supplementary Fig. 12a). Other than being strictly rigid, TPP blocks possess rotatable meso C–C bonds to allow substituents on the porphyrin ring to reorientate under the control of intermediary steric effects. As shown in Fig. S12b, the TTP-8PD intermediate encounters a very small steric hindrance, so the eight linkers are still aligned in-plane. However, the resulting BNU-1 is nearly amorphous instead of being a 2D COF, because the TTP-8PD intermediates can exert little restriction on the extending orientations and stereoconformations during the polycondensation process, tending to proceed in a disordered manner. In sharp contrast, the TTP-8BD and TTP-8TD intermediates experienced remarkable steric hindrance-driven conformational changes after DFT optimization (Supplementary Fig. 12c, d). The extended groups at the meso position break away from the tetrapyrrole ring plane of the porphyrin backbone42, forming a 3D configuration similar to the propeller blade with approximate D4 point symmetry.

To investigate the mechanistic role of steric effects in intermediates during COF formation, we employed two computational approaches: flexible potential energy surface (PES) scans and molecular dynamics (MD) simulation. As shown in Fig. 4a, we quantified the stereoconfiguration of the intermediates using the dihedral angle between the porphyrin plane and the benzene ring plane. Flexible PES scans further demonstrated that the energy-minimized dihedral angles for TTP-8BD (69°) and TTP-8TD (69.5°) were similar, both being higher than that of TTP-8PD (65°) (Fig. 4b). The PES profiles also indicated that TTP-8BD and TTP-8TD exhibited higher energy barriers for low-angle deformations compared to TTP-8PD, implying reduced structural flexibility of the former two intermediates. MD simulation revealed a centralized distribution of dihedral angles (Fig. 4c) as the result of different intramolecular interactions (Supplementary Figs. 13–15). For TTP-8PD, only hydrogen bonding interactions between terminal amino groups prevailed in the molecule trajectory, yielding a near-planar conformation of the intermediate. In addition to hydrogen bonding, TTP-8BD exhibited π-π interactions between adjacent terminal benzene rings. The two types of intramolecular interactions co-determined a twisted conformation with broken planarity. With longer π-conjugated arms, TTP-8TD adopted a more spatially restricted conformation with a higher degree of non-planarity, primarily relying on π-π stacking interactions between extended aromatic rings. These results suggest that the differences in crystallinity among the corresponding COFs may arise from variations in the intramolecular interaction. Specifically, terminal hydrogen bonding appeared to hinder the crystallization while π-π interactions promoted this process. Intermediates with sufficiently large steric hindrance exhibit more rigid 3D molecular architectures, attenuated hydrogen bonding strength, and enhanced π-π stacking interactions, leading to restricted conformational flexibility that facilitates the formation of highly crystalline 3D COFs by promoting ordered stacking during assembly.

a The dihedral angle between the porphyrin ring plane (blue) and the benzene ring plane (red) was used to quantify the stereoconfiguration of the intermediates (TTP-8PD, TTP-8BD and TTP-8TD). b Flexible PES diagram of the intermediates (TTP-8PD, TTP-8BD and TTP-8TD). The horizontal axis represents the dihedral angle from (a), while the vertical axis shows the relative energy of the intermediate at each corresponding angle. c Distribution of MD-simulated dihedral angles.

Scanning electron microscopy (SEM) revealed that BNU-2 is composed of stacked small cubes with sides measuring approximately 50 nm (Fig. 5a), while BNU-3 consists of twisted square filaments (Fig. 5b). The porosity and crystallinity of BNU-2 and BNU-3 were characterized by high-resolution transmission electron microscopy (HR-TEM), which clearly displayed quadrangular-arranged channels and periodic fringes (Fig. 5c, d). The channel width of 0.63 nm closely matches the modeled distance of 0.62 nm for BNU-2 (Figs. 3c, 5c). Similarly, the pore size of BNU-3, measured at 1.13 nm, aligns well with its modeled value of 1.18 nm (Figs. 3f, 5d). The lattice spacings for BNU-2 and BNU-3 were respectively measured at 2.23 nm and 2.69 nm, both corresponding to the 101 lattice plane. N2 adsorption-desorption isotherms at 77 K were utilized to explore the pore characteristics of the COFs. As shown in Fig. 5e, f, both crystalline frameworks exhibited typical type-I isotherms, indicative of microporous characteristics. By the Brunauer-Emmett-Teller (BET) equation, the specific surface areas of BNU-2 and BNU-3 were respectively calculated to be 522 m²/g and 632 m²/g (Supplementary Table 1), relatively low due to the interpenetrated structures that may lead to pore channel blockage and reduced accessibility of adsorption sites1. DFT calculations indicated that BNU-2 and BNU-3 possess narrow pore size distributions centered at 0.64 nm and 1.18 nm (Supplementary Fig. 16), respectively, corroborating the values derived from the modeled crystal structures and HR-TEM measurements. We also assessed the stability of the synthesized 3D COFs by thermal gravimetric analysis (TGA), which showed a mass loss of approximately 7.5% at 120 °C due to the evaporation of water molecules adsorbed within the framework and suggested the onset of thermal decomposition at 400 °C (Supplementary Fig. 17).

Furthermore, solid-state UV-vis spectroscopy unraveled that both BNU-2 and BNU-3 strongly adsorb in the 300–700 nm regions (Supplementary Fig. 18). Porphyrins and their derivatives are photosensitizers, which can promote the conversion of dioxygen to singlet oxygen (¹O₂) under photoirradiation43,44. This encouraged us to assess the photocatalytic performances of BNU-2 and BNU-3 in generating ¹O₂ as heterogeneous photocatalysts. As illustrated in Supplementary Fig. 19, an 8-min illumination at 660 nm can trigger the rapid production of ¹O₂ by BNU-2 or BNU-3, consuming 86.6% or 99.3% of 1, 3-diphenylisofuran (DPBF), respectively, whereas illumination without COFs caused only 10.6% consumption of DPBF. The capacities of photocatalytic production of ¹O₂ by BNU-2 and BNU-3 far exceed that of 3D Por-COF (60% consumption of indicators after photoirradiation for 50 min) formed from tetrahedral precursors13. Time-resolved fluorescence decay spectroscopy was employed to characterize BNU-2 and BNU-3 (Supplementary Fig. 20a). The shorter fluorescence lifetime observed for BNU-2 compared to BNU-3 suggests a faster photoelectron transfer process45 in BNU-3. Complementary photocurrent response measurements (Supplementary Fig. 20b) revealed that BNU-3 generates a significantly stronger photocurrent than BNU-2, demonstrating more efficient charge separation46 facilitated by its extended linker structure. Furthermore, we compared the ¹O₂ generation capability of BNU-3 to reported systems and demonstrated a comparable performance of our designed 3D COFs (Supplementary Table 2), with high structural stability and crystallinity for photocatalysis (Supplementary Fig. 21).

Discussion

We have developed a strategy for controlling the interpenetration of 3D COFs by tailoring the intermediary steric hindrance in the polycondensation process. This approach offers a fresh perspective on how we can use multinode planar building blocks decorated with rotatable linear π-linkers to influence framework growth through pre-designable, reorientable and self-adaptive intermediates, which can be regarded as active precursors that participate in tuning and stabilizing the stereoconformations in a 3D manner. This ability to regulate steric hindrance opens up exciting opportunities for designing 3D COFs with expandable topologies and functionalities. One of the notable advantages of our strategy is its potential universality. The distinct characteristics of intermediate molecules during COF formation differ significantly from those of traditional precursors. This variance is crucial because it allows for a wider range of synthetic methods to be involved for the discovery of new frameworks that might not have been possible with conventional strategies. Moreover, this work introduces intermediates as an additional variable to the existing precursor design strategy, with a focus on investigating their influence on the dimensionality of COFs during formation. Since the structures of intermediates can be predicted and modulated, it enlightens an effective pathway for expanding the repertoire of 3D COFs. In the future, it will be necessary to develop in situ and real-time analytical methods to monitor the transformation process from precursors to intermediates and finally to COFs, thereby elucidating the molecular mechanisms governing COF formation to revolutionize the synthesis of COFs and broaden their applications.

Methods

Materials

Dichloromethane (DCM), petroleum ether (PE), ethyl acetate (EA), trichloromethane (CHCl3), concentrated sulfuric acid (H2SO4), acetone and toluene were purchased from TGREAR. Isophthalaldehyde, N-bromosuccinimide, anhydrous sodium sulfate (Na2SO4), chloroform-d, 2,2-dimethylpropane-1,3-diol, p-toluenesulfonic acid (p-TsOH), tetrahydrofuran (THF), n-butyllithium (n-BuLi), N,N-dimethylformamide (DMF), ammonium chloride (NH4Cl), pyrrole, trifluoroacetic acid (TFA), p-chloranil, triethylamine, sodium carbonate (Na2CO3), (Dimethyl sulfoxide)-d6 (DMSO-d6), p-phenylenediamine (PD), benzidine (BD), 4,4”-diamino-p-terphenyl (TD), 1,2-dichlorobenzene (o-DCB), n-butanol (n-BuOH), Mesitylene (Mes), 1,4-dioxane (Dio), 1,3-diphenylisofuran (DPBF), N-methylpyrrolidone and acetic acid (AcOH) were purchased from Innochem. All reagents were of commercial grade, and solvents were of analytical purity.

Synthesis of 5-Bromoisophthalaldehyde (1)

A mixture of isophthalaldehyde (50.00 g, 372.7 mmol, 1.0 eq.) and concentrated sulfuric acid (200 mL) was stirred at 65 °C. Then, N-bromosuccinimide (72.98 g, 410.1 mmol, 1.1 eq.) was added to the mixture slowly over 30 min. The reaction was stirred at the same temperature for 24 h. After cooling down to room temperature, the mixture was slowly poured into ice water (1 L) with stirring. The solid was collected by filtration and washed with water until the filtrate became neutral. Then, the solid was dissolved in DCM and washed with water three times. The organic layer was dried with anhydrous Na2SO4. The solvent was removed to give 1 as a beige solid in 60% yield, which could be used directly in the next step. 1H NMR spectrum of 1 is shown in Supplementary Fig. 22.

Synthesis of 2,2’-(5-Bromo-1,3-phenylene)bis(5,5-dimethyl-1,3-dioxane) (2)

Synthetic procedure was modified from the protocol reported by He et al.47. A solution of 1 (25 g, 117 mmol), 2,2-dimethylpropane-1,3-diol (40 g, 350 mmol), and p-TsOH (50 mg) in toluene (250 mL) was refluxed using a Dean-Stark trap for 24 h. After cooling down to room temperature, the toluene was removed. The crude product was purified by column chromatography (silica, petroleum ether/ethyl acetate 50:1) to give 2 as a white solid in 90% yield. 1H NMR spectrum of 2 is shown in Supplementary Fig. 23.

Synthesis of 3,5-Bis(5,5-dimethyl-1,3-dioxan-2-yl)benzaldehyde (3)

Synthetic procedure was modified from the protocol reported by He et al.47. Compound 2 (20 g, 52 mmol) was dissolved in anhydrous THF (300 mL) under Ar atmosphere. Then, n-BuLi solution (24 mL, 2.5 M in hexane) was added slowly at −78 °C. After the solution was stirred at −78 °C for 2 h, anhydrous DMF (8 mL, 104 mmol) was added at −78 °C, and the mixture was allowed to warm to 0 °C and stirred for 1 h. The reaction was quenched by aqueous NH4Cl (100 mL, 1 M). The mixture was extracted with DCM and washed with water three times. The organic layer was combined and dried with anhydrous Na2SO4. The crude product was purified by column chromatography (silica, petroleum ether/ethyl acetate 10:1) to give 3 as a white solid in 80% yield. 1H NMR spectrum of 3 is shown in Supplementary Fig. 24.

Synthesis of 5,10,15,20-tetrakis(3,5-bis(5,5-dimethyl-1,3-dioxan-2-yl)phenyl)porphyrin (4)

Compound 3 (4.56 g, 13.65 mmol) was dissolved in DCM (400 mL) under Ar atmosphere at room temperature. Then, pyrrole (1.2 mL) and TFA (0.85 mL) were slowly added to the solution in turn. After the solution was stirred for 4 h, p-chloranil (1.75 g, 7.1 mmol) was added, and the mixture was stirred for one night. After the overnight reaction, triethylamine (2.4 mL) was added to neutralize the acid. The solvent was removed under vacuum to give crude black solid products. The pure product 4 was achieved by column chromatography (silica, DCM/EA 80:1) as a purple solid in 11% yield. 1H NMR, 13C NMR and MALDI-TOF MS spectra of 4 are shown in Supplementary Figs. 25–27.

Synthesis of 5,5’,5”,5”’-(porphyrin-5,10,15,20-tetrayl)tetraisophthalaldehyde (TTP)

Compound 4 (300 mg, mmol) was dissolved in a mixture of CHCl4 (30 mL) and TFA (30 mL). The solution was refluxed for 3 days at 65 °C. After cooling down to room temperature, the solvent was removed by vacuum evaporation, and the saturated Na2CO3 aqueous solution (30 mL) was added. The purple solid was collected by filtration, washed with water and methanol, and dried under vacuum at room temperature overnight (Yield, 97%). 1H NMR and MALDI-TOF MS spectra of TTP are shown in Supplementary Figs. 28, 29.

Synthesis of BNU-1/2/3

A Pyrex tube measuring 10 × 7 mm (o.d × i.d) was loaded with TTP (16.77 mg, 0.02 mmol), PD (8.65 mg, 0.08 mmol)/BD(14.73 mg, 0.08 mmol)/TD (20.81 mg, 0.08 mmol), 1,2-dichlorobenzene (0.5 mL), n-butanol (0.5 mL), and 6 M aqueous AcOH (0.1 mL). After 10 min of sonication, the tube was flash frozen at 77 K (liquid N2 bath). After 5 min of pumping, the tube was sealed by flame at a distance of 4 cm from the top. The reaction was heated at 120 °C for 72 h to yield a green solid. The product was washed several times with DMF and acetone in turn, filtered and dried to obtain the green solid. Yield: (88%/97%/95%).

Data availability

All data generated in this study are provided in the Supplementary Information and Source Data file. All the data are available from the corresponding author upon request. Source data are provided with this paper.

References

Guan, X., Chen, F., Fang, Q. & Qiu, S. Design and applications of three dimensional covalent organic frameworks. Chem. Soc. Rev. 49, 1357–1384 (2020).

Chen, F. et al. Exploring high-connectivity three-dimensional covalent organic frameworks: topologies, structures, and emerging applications. Chem. Soc. Rev. 54, 484–814 (2025).

Waller, P. J., Gándara, F. & Yaghi, O. M. Chemistry of covalent organic frameworks. Acc. Chem. Res. 48, 3053–3063 (2015).

Kandambeth, S., Dey, K. & Banerjee, R. Covalent organic frameworks: chemistry beyond the structure. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 141, 1807–1822 (2019).

Zhu, R., Ding, J., Jin, L. & Pang, H. Interpenetrated structures appeared in supramolecular cages, MOFs, COFs. Coord. Chem. Rev. 389, 119–140 (2019).

El-Kaderi, H. M. et al. Designed synthesis of 3D covalent organic frameworks. Science 316, 268–272 (2007).

Li, Z. et al. Synthesis of 12-connected three-dimensional covalent organic framework with lnj topology. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 146, 4327–4332 (2024).

Lan, Y. et al. Materials genomics methods for high-throughput construction of COFs and targeted synthesis. Nat. Commun. 9, 5274 (2018).

Kang, X. et al. Reticular synthesis of tbo topology covalent organic frameworks. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 142, 16346–16356 (2020).

Xu, X., Cai, P., Chen, H., Zhou, H.-C. & Huang, N. Three-dimensional covalent organic frameworks with she topology. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 144, 18511–18517 (2022).

Gropp, C., Ma, T., Hanikel, N. & Yaghi, O. M. Design of higher valency in covalent organic frameworks. Science 370, eabd6406 (2020).

Uribe-Romo, F. J. et al. A crystalline imine-linked 3D porous covalent organic framework. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 131, 4570–4571 (2009).

Lin, G. et al. 3D porphyrin-based covalent organic frameworks. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 139, 8705–8709 (2017).

Ma, T. et al. Single-crystal X-ray diffraction structures of covalent organic frameworks. Science 361, 48–52 (2018).

Xie, Y. et al. Tuning the topology of three-dimensional covalent organic frameworks via steric control: from pts to unprecedented ljh. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 143, 7279–7284 (2021).

Yu, B. et al. Linkage conversions in single-crystalline covalent organic frameworks. Nat. Chem. 16, 114–121 (2024).

Li, H. et al. Three-dimensional large-pore covalent organic framework with stp topology. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 142, 13334–13338 (2020).

Zhu, Q. et al. 3D cage COFs: a dynamic three-dimensional covalent organic framework with high-connectivity organic cage nodes. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 142, 16842–16848 (2020).

Li, Z. et al. Three-dimensional covalent organic framework with ceq topology. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 143, 92–96 (2021).

Li, Z. et al. Three-dimensional covalent organic frameworks with hea topology. Chem. Mater. 33, 9618–9623 (2021).

Martínez-Abadía, M. et al. π-Interpenetrated 3D covalent organic frameworks from distorted polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 60, 9941–9946 (2021).

Jin, F. et al. Bottom-up synthesis of 8-connected three-dimensional covalent organic frameworks for highly efficient ethylene/ethane separation. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 144, 5643–5652 (2022).

Wu, M., Shan, Z., Wang, J., Liu, T. & Zhang, G. Three-dimensional covalent organic framework with tty topology for enhanced photocatalytic hydrogen peroxide production. Chem. Eng. J. 454, 140121 (2023).

Shan, Z. et al. 3D covalent organic frameworks with interpenetrated pcb topology based on 8-connected cubic nodes. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 144, 5728–5733 (2022).

Gong, C. et al. Synthesis and visualization of entangled 3D covalent organic frameworks with high-valency stereoscopic molecular nodes for gas separation. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 61, e202204899 (2022).

Liu, W. et al. Highly connected three-dimensional covalent organic framework with flu topology for high-performance Li-S batteries. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 145, 8141–8149 (2023).

Zhang, Y. et al. Three-dimensional anionic cyclodextrin-based covalent organic frameworks. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 56, 16313–16317 (2017).

Yahiaoui, O. et al. 3D anionic silicate covalent organic framework with srs topology. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 140, 5330–5333 (2018).

Wang, X. et al. A cubic 3D covalent organic framework with nbo topology. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 143, 15011–15016 (2021).

Nguyen, H. L., Gropp, C., Ma, Y., Zhu, C. & Yaghi, O. M. 3D covalent organic frameworks selectively crystallized through conformational design. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 142, 20335–20339 (2020).

Zhu, D. et al. Three-dimensional covalent organic frameworks with pto and mhq-z topologies based on tri- and tetratopic linkers. Nat. Commun. 14, 2865 (2023).

Lu, M. et al. 3D covalent organic frameworks with 16-connectivity for photocatalytic C(sp3)–C(sp2) cross-coupling. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 146, 25832–25840 (2024).

Yin, Y. et al. Ultrahigh–surface area covalent organic frameworks for methane adsorption. Science 386, 693–696 (2024).

Feng, X., Ding, X. & Jiang, D. Covalent organic frameworks. Chem. Soc. Rev. 41, 6010–6022 (2012).

Geng, K. et al. Covalent organic frameworks: design, synthesis, and functions. Chem. Rev. 120, 8814–8933 (2020).

Jin, F. et al. Rationally fabricating 3D porphyrinic covalent organic frameworks with scu topology as highly efficient photocatalysts. Chem 8, 3064–3080 (2022).

Liu, X. et al. Triazine–porphyrin-based hyperconjugated covalent organic framework for high-performance photocatalysis. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 144, 23396–23404 (2022).

Beyzavi, M. H., Nietzold, C., Reissig, H.-U. & Wiehe, A. Synthesis of functionalized trans-A2B2-porphyrins using donor–acceptor cyclopropane-derived dipyrromethanes. Adv. Synth. Catal. 355, 1409–1422 (2013).

Kumar, R. S., Kim, H., Mergu, N. & Son, Y.-A. A photocatalytic comparison study between tin complex and carboxylic acid derivatives of porphyrin/TiO2 composites. Res. Chem. Intermed. 46, 313–328 (2020).

O’Keeffe, M., Peskov, M. A., Ramsden, S. J. & Yaghi, O. M. The Reticular Chemistry Structure Resource (RCSR) database of, and symbols for, crystal nets. Acc. Chem. Res. 41, 1782–1789 (2008).

Database of Zeolite Structures. http://www.iza-structure.org/databases/ (2017).

Guo, X. et al. Homolytic versus heterolytic hydrogen evolution reaction steered by a steric effect. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 59, 8941–8946 (2020).

Tian, J., Huang, B., Nawaz, M. H. & Zhang, W. Recent advances of multi-dimensional porphyrin-based functional materials in photodynamic therapy. Coord. Chem. Rev. 420, 213410 (2020).

Kandambeth, S. et al. Enhancement of chemical stability and crystallinity in porphyrin-containing covalent organic frameworks by intramolecular hydrogen bonds. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 52, 13052–13056 (2013).

Wu, K. et al. Linker engineering for reactive oxygen species generation efficiency in ultra-stable nickel-based metal–organic frameworks. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 145, 18931–18938 (2023).

Dong, P. et al. Stepwise protonation of three-dimensional covalent organic frameworks for enhancing hydrogen peroxide photosynthesis. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 63, e202405313 (2024).

He, T. et al. Porphyrin-based covalent organic frameworks anchoring Au single atoms for photocatalytic nitrogen fixation. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 145, 6057–6066 (2023).

Acknowledgements

This work is supported by the National Key Research and Development Program of China (2024YFA1803400 for L.M.), the National Natural Science Foundation of China (22134002 for L.M., 22222411 and 21927804 for F.W., and 22125406 and 22074149 for P.Y.), the Natural Science Foundation of Beijing (Z230022 for P.Y., and 2242028 for W.M.), Fundamental Research Funds for the Central Universities (F.W.), and Postdoctoral Fellowship Program of CPSF (GZC20230260 for S.L.). We also thank the Analytical Test Platform of the College of Chemistry of Beijing Normal University and the Analytical Test Platform of the Institute of Chemistry of the Chinese Academy of Sciences for performing structural characterizations of 3D COFs.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

J.L. and L.M. conceived the idea of the research. J.L. designed the experiments. J.L. performed synthesis, structural determination, XRD characterizations and modeling. S.L. performed SEM and singlet oxygen evolution experiments. W.M., F.W. and P.Y. contributed to data analysis and discussions. J.L., F.W. and L.M. wrote the original draft. All authors contributed to the finalization of the draft. L.M. supervised the whole project.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Peer review

Peer review information

Nature Communications thanks Rahul Banerjee, Shilun Qiu and the other anonymous reviewer(s) for their contribution to the peer review of this work. A peer review file is available.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Source data

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Lai, J., Liu, S., Ma, W. et al. Steric effect of intermediates induces formation of three-dimensional covalent organic frameworks. Nat Commun 16, 6071 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-025-61373-1

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-025-61373-1

This article is cited by

-

DFT-based evaluation of covalent organic frameworks for adsorption, optoelectronic, clean energy storage, and gas sensor applications

Journal of Molecular Modeling (2025)