Abstract

The interplay between superconductivity and charge or spin order is a key focus in condensed matter physics, with kagome lattice systems providing unique insights. The kagome superconductor LaRu3Si2 (Tc ≃ 6.5 K) features a characteristic kagome band structure and a hierarchy of charge order transitions at Tco,I ≃ 400 K and Tco,II ≃ 80 K, along with an additional transition at T* ≃ 35 K associated with electronic and magnetic responses. Using magnetotransport under pressure up to 40 GPa, we find Tc peaks at 9 K (2 GPa)—the highest among kagome superconductors—remains nearly constant up to 12 GPa, and then decreases to 2 K at 40 GPa, forming a dome-shaped phase diagram. Similarly, both the resistivity anomaly at T* and the magnetoresistance exhibit a dome-shaped pressure dependence. Moreover, above 12 GPa, X-ray diffraction reveals that the charge order evolves from long-range to short-range, coinciding with the suppression of Tc. These observations indicate that superconductivity in LaRu3Si2 is closely linked to the charge-ordered state and the electronic responses at Tco,II and T*.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The kagome lattice1,2,3,4,5,6,7,8,9,10,11,12, composed of corner-sharing triangles, has attracted growing interest in condensed matter physics due to its inherent geometric frustration, nontrivial band topology, and potential to host a variety of exotic quantum phases. In recent years, several kagome metals—most notably the AV3Sb5 family (A = K, Rb, Cs)10,11,12—have been identified as hosts of unconventional charge ordering phenomena intertwined with superconductivity and other symmetry-breaking orders2,3,13,14,15,16,17,18,19,20,21,22,23,24,25,26,27,28,29,30. These materials exhibit a charge density wave (CDW) transition at high temperatures, followed by superconductivity at lower temperatures, suggesting a complex interplay between competing or cooperating electronic ground states. What makes these systems particularly intriguing is the unconventional nature of their charge order, including features such as time-reversal symmetry breaking and the presence of nematicity—a spontaneous breaking of rotational symmetry without structural distortion. Such features go well beyond the expectations of a conventional Peierls-like CDW and hint at deeper, potentially topological or correlation-driven origins.

In parallel, related kagome compounds such as ScV6Sb6, CsTi3Bi531, CsCr3Sb532 and others have also shown signs of rich electronic behavior, including charge ordering tendencies and superconductivity, though often with different transition temperatures, symmetry properties, or structural responses. These findings collectively suggest that the kagome lattice provides a versatile framework for exploring novel forms of electronic order. However, despite these advances, the microscopic origin of the charge order, the nature of its coupling to superconductivity, and the full scope of associated electronic and magnetic responses remain poorly understood.

To address these outstanding issues, it is essential to broaden the investigation beyond the well-studied AV3Sb5 family and examine other kagome systems to identify universal features and material-specific behaviors. In this context, LaRu3Si24,7,9 stands out as a kagome superconductor with a relatively high superconducting critical temperature (Tc = 6.5 K) and a charge order (propagation vector of (\(\frac{1}{4}\), 0, 0)) with an exceptionally high onset temperature, Tco,I ≃ 400 K-the highest recorded for any kagome superconductor7. This high-temperature charge order distinguishes LaRu3Si2 from its counterparts, suggesting an unusual stability of ordered electronic phases even at elevated temperatures. In addition to this high-temperature charge order, we identified a second charge ordering transition with a propagation vector of (\(\frac{1}{6}\), 0, 0) below Tco,II ≃ 80 K33, coexisting with (\(\frac{1}{4}\), 0, 0)) charge order. The secondary charge order aligns with a significant change in the electronic structure, as indicated by the emergence of magnetoresistance. The magnetoresistance begins to increase below Tco,II ≃ 80 K, with a sharper rise observed below T* ≃ 35 K33. Additionally, a sign reversal in the Hall effect occurs across T*33. These transitions at 80 K and 35 K are not purely electronic but are accompanied by the onset of magnetism—at 35 K in zero field and at 80 K under high magnetic field as revealed by muon-spin rotation (μSR) measurements. Consequently, three distinct temperature scales have been identified: Tco,I ≃ 400 K, Tco,II ≃ 80 K, and T* ≃ 35 K. This sequence of charge ordering and magnetic transitions below 80 K suggests a coupling between the electronic and magnetic degrees of freedom, raising intriguing questions about the role of magnetism in the ground state of LaRu3Si2. While these properties are intriguing, the interplay between superconductivity, charge order, and the normal-state electronic response remains largely unexplored, particularly given the complex phase landscape introduced by the kagome lattice.

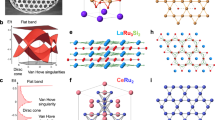

To investigate this interplay, we conducted a comprehensive study using a combination of resistivity, magnetoresistance, and single-crystal X-ray diffraction measurements under extreme pressures, reaching up to 40 GPa using a diamond-anvil cell (Fig. 1a and b). The motivation for employing high-pressure techniques is to precisely tune distortions within the charge-ordered state and systematically examine their influence on superconductivity and normal-state properties. This approach aims to elucidate the role of such distortions in shaping superconducting behavior and normal-state transport responses. By applying such pressures, we observe an evolution in Tc, which initially increases from 6.5 K to 9 K at 2 GPa and remains steady up to 12 GPa, after which it gradually decreases, reaching 2 K at 40 GPa (Fig. 1c). This dome-shaped superconducting phase diagram is a hallmark of potential unconventional superconductivity. Notably, the strength of the resistivity anomaly across T* as well as the base-T value of magnetoresistance exhibits a similar dome-shaped pressure dependence (Fig. 1d), revealing a positive correlation between them (Fig. 1f). Furthermore, the suppression of Tc beyond the superconducting dome correlates with a decrease in the onset temperature of the primary charge order under pressure. Long-range order persists up to 12 GPa, where the onset temperatures of the two charge orders converge Tco,I ≃ Tco,II and transition into short-range order (Fig. 2). These results highlight a strong and positive correlation between superconductivity and charge order coherence, as well as the electronic responses associated with Tco,II and T*. Notably, the superconducting critical temperature is maximized when the charge order remains long-range and the normal-state electronic properties are most optimized. While a detailed discussion of the microscopic mechanism is beyond the scope of this manuscript, our systematic and comprehensive experimental findings strongly motivate further theoretical work to provide deeper microscopic insight. Furthermore, these findings open avenues for future experiments—such as applying uniaxial stress along multiple directions—to manipulate Ru-site distortions, T* and Tco,II, with the potential to enhance the superconducting critical temperature.

a Schematic illustration of the diamond anvil cell setup, showing the anvils, gasket, sample, pressure indicator, and pressure-transmitting medium. b Side view of the atomic structure of LaRu3Si2. The Ru atoms construct a kagome lattice (red middle-size circles), while the Si (green small-size circles) and La atoms (blue large-size circles) form a honeycomb and triangular structure, respectively. c Pressure dependence of the superconducting critical temperature, determined from the temperature dependence of resistivity using three criteria: onset, midpoint, and zero-resistance values. d The strength of the anomaly in resistivity near T* ≃ 30-40 K. The magnetoresistance at 9 T is also shown as a function of pressure on the right axis. e Pressure dependence of T* and TCO,II, determined from the resistivity measurements. Long-range and short-range charge-ordered regions of the phase diagram is noted based on X-ray diffraction experiments. The plots include error bars that indicate the standard error. The standard error is a measure of the variability or precision of a sample mean. f The strength of the anomaly in resistivity near T* and the magnetoresistance at 9 T as a function of superconducting critical temperature Tc.

Results

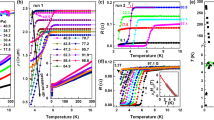

Figure 3 a presents the temperature dependence of resistivity (see also Supplementary Figs. S1 and S2) for LaRu3Si2, focusing on the low-temperature range, measured at ambient pressure and under applied pressures up to 38 GPa. At ambient pressure, the system displays a well-defined superconducting transition, with an onset temperature \({T}_{c}^{{{{\rm{onset}}}}}\) of 6.5 K, and reaching zero resistance below 6 K, indicating a robust superconducting phase. With an applied pressure of 1 GPa, Tc,onset increases noticeably to 9 K, although the transition becomes relatively broader, suggesting pressure-induced modifications in the superconducting properties. As the pressure increases further, up to 10 GPa, \({T}_{c}^{{{{\rm{onset}}}}}\) remains at 9 K; however, the superconducting transition sharpens, indicating an enhancement in phase coherence or homogeneity in the superconducting state under moderate pressures. This stability in the superconducting onset up to 10 GPa reflects the systems resilience to pressure within this range. Beyond 10 GPa, the onset of superconductivity begins to decrease gradually, signifying a pressure-induced suppression of superconductivity. By 38 GPa, the onset temperature has decreased significantly, reaching 2 K, pointing to a diminishing superconducting state at high pressures. Figure 3d–i illustrate the suppression of the transitions under magnetic fields at selected pressures, confirming the superconducting nature of the transitions. Additionally, they demonstrate a decrease in the critical field as pressure is reduced.

a Temperature dependence of resistivity, normalized to the value at 15 K, focusing on the low-temperature region to highlight the superconducting transitions recorded at ambient pressure and under pressures up to 38 GPa. b, c Temperature dependence of resistivity, normalized to the value at 300 K, measured over a wide temperature range at various pressures within 0-10 GPa and 13.6-51 GPa. d–i Temperature dependence of resistivity below 10 K, measured under different applied magnetic fields at selected pressures: (d) 1 GPa, (e) 6.7 GPa, (f) 10 GPa, (g) 15.4 GPa, (h) 20.2 GPa, and (i) 31.4 GPa.

For clarity in interpreting these observations, we define three characteristic temperatures: the onset temperature \({T}_{c}^{{{{\rm{onset}}}}}\), the midpoint temperature \({T}_{c}^{{{{\rm{midpoint}}}}}\) (where resistivity decreases by 50%), and the temperature \({T}_{c}^{{{{\rm{zero}}}}}\) below which resistivity reaches zero. These defined temperatures are illustrated in the phase diagram shown in Fig. 1c, which captures the overall pressure-dependent superconducting behavior. The phase diagram exhibits a dome-shaped superconducting region, indicating an optimal pressure range where superconductivity is most robust, with suppression occurring beyond this optimal range. This dome-shaped behavior highlights the intricate interplay between pressure and superconductivity in LaRu3Si2, potentially revealing insights into the underlying mechanisms of superconductivity in this system.

Next, we discuss the normal-state response observed in the resistivity data. Notably, no anomaly is detected across Tco,II either at ambient pressure or under applied pressure. However, an anomaly is evident across T*, which is weak at ambient pressure but becomes clear in the first derivative of the resistivity, as shown in Fig. 4a. Interestingly, applying pressure enhances the prominence of this anomaly, particularly in the pressure range between 2.2 GPa and 15.4 GPa. In this range, the anomaly is clearly visible in the resistivity data and is further accentuated in the first derivative, where sharper and more intense peaks are observed. Above 15.4 GPa, the anomaly progressively weakens, and the peaks in the first derivative become less intense and broader. To characterize the pressure evolution of this anomaly, we calculated the difference in the first derivative dR/dT between its maximum value at T* and its value at 120 K. This difference serves as a measure of the anomaly’s strength and is plotted as a function of pressure in Fig. 1d. Remarkably, the anomaly exhibits a dome-shaped pressure dependence, with its maximum occurring in the pressure range of 1-15.4 GPa, coinciding with the pressure range where the superconducting transition temperature Tc reaches its peak. To highlight this, we plot the anomaly strength as a function of Tc, revealing a clear linear correlation (Fig. 1f). This indicates that the anomaly at T* becomes most pronounced when superconductivity is optimal. This correlation implies an intimate connection between Tc and T*, the latter being the temperature below which muon-spin rotation experiments detect time-reversal symmetry breaking and magnetotransport measurements show enhanced magnetoresistance. In Fig. 1e, the pressure dependence of T*, determined as the peak position in the first derivative, is presented. While the absolute value of T* changes slightly with pressure, it exhibits a dip around 12 GPa, aligning with the maximum Tc.

Both temperature scales, T* and Tco,II, in LaRu3Si2, are also reflected in magnetoresistance (MR) measurements. Magnetotransport techniques34,35,36,37,38,39,40, known for their sensitivity to charge-order transitions, utilize MR as an indicator of the mean free path integrated over the Fermi surface37. This approach is particularly effective in detecting changes in scattering anisotropy and Fermi surface reconstructions. Figure 5a–d present the MR in LaRu3Si2 under a perpendicular magnetic field across the temperature range of 10 K to 80 K, measured at p = 0 GPa and at selected pressures of p = 2.2 GPa, 20.2 GPa, and 41.8 GPa. Additionally, Fig. 4b shows the temperature dependence of MR at 9 T, recorded under various pressures. Within the primary 1/4 charge-ordered state, the MR remains negligible and only begins to appear below the 1/6 charge ordering temperature Tco,II. At p = 0 GPa, the MR starts to increase at Tco,II, with a steeper rise occurring below T* (see Figs. 4b and 5a). Under a pressure of 2.2 GPa, both the onset of MR and its base-temperature value at 9 T remain unchanged down to T*, below which the MR increases significantly (see Figs. 4b and 5b). Notably, the MR(9T) value at 10 K reaches 14 %, nearly twice the value observed at ambient pressure. However, when pressure exceeds 15 GPa, the MR decreases and eventually becomes smaller than the value recorded at ambient pressure (see Fig. 5c and d). Despite these changes, the onset of charge order at Tco,II remains nearly unaffected. These MR experiments reveal that the absolute value of MR is maximized within the pressure range where superconductivity is optimal, highlighting a strong connection between charge order, magnetotransport properties, and superconductivity in LaRu3Si2.

To complement the resistivity experiments, we conducted X-ray diffraction measurements41 up to 20 GPa, providing direct insight into both the 1/4 and 1/6 charge orders. In Fig. 6a–d, we present reconstructed reciprocal-space patterns along the (hk1) direction for 300 K at selected pressures for a single crystal of LaRu3Si2. At higher temperature (T = 300K) T (see Fig. 6a), the diffraction pattern reveals fundamental Bragg peaks τ and superlattice peaks at Q = τ + qi with q1 = (\(\frac{1}{4}\),0,0) and q2 = (0,\(\frac{1}{4}\),0). The application of pressure suppresses the onset temperature of the primary charge order (Tco,I) such that already at 7 GPa charge order peaks are not visible (Fig. 6b–d). As the temperature decreases below Tco,II ≃ 80 K (see Fig. 6e, i), an additional set of reflections emerges at positions corresponding to \(q^{\prime}_{1}\)=(\(\frac{1}{6},0,0\)), \(q^{\prime}_{2}\)=(0, \(\frac{1}{6},0\)), and \(q^{\prime}_{3}\)=(\(\frac{1}{6},\frac{-1}{6},\,0\)). Significantly, both \(\frac{1}{4}\) and \(\frac{1}{6}\) charge orders coexist below 80 K, persisting into the superconducting state33. While the application of pressure suppresses the onset temperature of the primary charge order (Tco,I), the onset temperature (Tco,II) below which 1/4 and 1/6 charge orders coexist remains nearly unaffected (see Fig. 6e–g). At approximately 12.5 GPa, Tco,I and Tco,II converge, beyond which broad, diffuse scattering intensity emerges at the same onset temperature (Tco,II) (see Fig. 6g, h), and it does not coalesce into sharp Bragg diffraction peaks down to base temperature. We note that the crossover from long-range to short-range charge order above 12.5 GPa begins around 80 K and persists down to 3 K, even in the superconducting state. As an example, we present data taken well below 80 K (see Fig. 6i–k). Notably, the transition from long-range charge order to a short-range state at 12.5 GPa coincides with the pressure at which the superconducting transition temperature begins to decrease. This correlation suggests a positive relationship between charge order and superconductivity in LaRu3Si2.

a–d Reconstructed reciprocal space in the (h k 1) plane, measured at T=300 K for various pressures (a) p=0.3 GPa, (b) 7 GPa, (c) 12 GPa, and (d) 18 GPa. Panels b,c,d correspond to the same area in reciprocal space as the other panels but reflections are indexed with a and b lattice parameters doubled. e–h Reconstructed reciprocal space in the (h k 1) plane, measured at T ≃ 70 K for various pressures p=0.4 GPa (e), 6.4 GPa (f), 12.5 GPa (g), and 19.8 GPa (h). i–k Reconstructed reciprocal space in the (h k 1) plane, measured at T ≃ 10 K for various pressures p=0.3 GPa (i), 6.5 GPa (j), 12.8 GPa (k). Green circles indicate Bragg peaks. Red and orange circles indicate the charge order peaks with a propagation vectors of (\(\frac{1}{4}\), 0, 0) and (\(\frac{1}{6}\), 0, 0), respectively. The bright reflection visible in (j and k) corresponds to a diamond reflection from one of the anvils.

Discussion

Charge order is a recurring motif in a wide variety of quantum materials, including cuprate high-temperature superconductors42, colossal magnetoresistive manganites43, transition-metal dichalcogenides (TMDs)44, and, more recently, kagome-lattice metals2. Its frequent emergence in close proximity to unconventional superconductivity has placed it at the center of discussions about competing and intertwined electronic orders. Understanding the relationship between charge order, superconductivity, and the associated normal-state electronic and magnetic responses remains one of the central challenges in condensed matter physics.

In this work, we explore this interplay in LaRu3Si2, a kagome superconductor notable for having one of the highest Tc among kagome systems. By systematically tuning the system with pressure and employing complementary transport and structural probes, we uncover a complex, but highly revealing, interdependence between superconductivity and charge order. Our key findings can be summarized as follows: (1) Tc exhibits a dome-shaped dependence on pressure, reaching a maximum of 9 K. This represents the highest superconducting onset temperature reported among kagome systems. (2) The resistivity anomaly at T*—linked to electronic and magnetic responses—also shows a dome-shaped pressure evolution, mirroring the behavior of Tc. Both Tc and T* are measured in zero-field conditions. (3) The low-temperature magnetoresistance, associated with both Tco,II and T*, follows a similar dome-like trend. (4) While the absolute value of T* varies only modestly with pressure, it exhibits a non-monotonic pressure dependence with a distinct dip near 12 GPa, aligning with the maximum in Tc. (5) The primary charge order transition temperature Tco,I is gradually suppressed under pressure, while Tco,II remains largely pressure-independent. (6) Importantly, above 12 GPa, the nature of the charge order associated with Tco,II evolves from long-range to short-range, coinciding with the onset of superconductivity suppression. These observations strongly support a scenario in which superconductivity is intimately connected to the charge-ordered state and the associated normal-state anomalies. In particular, the close correlation between Tc and the strength of the resistivity anomaly at T* suggests that the anomalous electronic and magnetic responses that develop below T* are enhanced when superconductivity is optimal. This is further substantiated by a linear relationship between Tc and the strength of the resistivity anomaly, as shown in Fig. 1f. The second critical link lies in the structural character of the charge order: the transition from long-range to short-range order above 12 GPa is accompanied by a marked suppression of Tc. This highlights the role of spatial coherence of the charge-ordered state in stabilizing superconductivity, even in the absence of a change in the onset temperature Tco,II.

The origin of superconductivity and charge order in kagome systems—whether primarily driven by electronic correlations or phonons—remains an open question. In AV3Sb5 (A = K, Rb, Cs), the proximity of van Hove singularities (vHS) to the Fermi level, combined with sublattice interference, is thought to drive the 2 × 2 charge order and contribute to its unconventional superconductivity. A similar charge pattern appears in magnetic kagome FeGe, while ScV6Sn6, despite also featuring vHS near the Fermi level, exhibits a distinctly phonon-driven charge order involving out-of-plane distortions of Sn and Sc atoms. In contrast, LaRu3Si2 hosts vHS derived from Ru-dz2 orbitals and displays a unique charge order combining in-plane Si and out-of-plane Ru displacements. It further distinguishes itself through its three-dimensional electronic structure and nearly isotropic superconductivity, in contrast to the quasi-two-dimensional nature of AV3Sb5. Furthermore, in contrast to AV3Sb5 and CsCr3Sb5, where superconductivity and charge order appear to compete, our findings in LaRu3Si2 reveal not competition but rather a coexistence between the two.

To understand the origin of this cooperative behavior, it is important to consider the underlying coupling mechanisms operating within the Ru-based kagome lattice. Recent theoretical studies45 reveal that superconductivity in LaRu3Si2 is primarily driven by strong coupling between kagome Ru-B3u phonons—associated with local displacements along the x-direction toward the hexagon center—and Ru Ag electrons, which are localized in the \({d}_{{x}^{2}-{y}^{2}}\) orbital. In parallel, our previous work has shown that charge order in LaRu3Si2 is intimately linked to out-of-plane distortions of the Ru-based kagome lattice7. Since the electronic states near the Fermi level are predominantly derived from Ru 4d orbitals, both the normal-state electronic properties and emergent phenomena such as TRS breaking originate from the Ru sublattice. Furthermore, the electronic structure is characterized by a quasi-flat band located just below the Fermi level, originating primarily from the Ru \({d}_{{x}^{2}-{y}^{2}}\) orbitals within the kagome network. This flat band was suggested to play a crucial role in superconductivity, likely by providing a high density of states near the Fermi level. Consequently, superconductivity, charge ordering, and the normal-state electronic response all share a common origin in the Ru 4d electronic states and are intrinsically linked to the kagome lattice. Given these insights, the pressure-induced evolution of superconductivity in LaRu3Si2 may be understood as a consequence of modifications to the coupling strength between kagome B3u phonons and Ag electrons, driven by changes in the Ru electronic structure under pressure. In this framework, a positive correlation emerges between superconducting properties, charge ordering tendencies, and normal-state electronic behavior, all interconnected through the delicate interplay of lattice, charge, and electronic degrees of freedom intrinsic to the Ru-based kagome lattice. While the microscopic mechanism by which pressure modifies the kagome phonons and electronic states remains to be fully understood, our experimental findings underscore the essential role of the kagome lattice in shaping the remarkable physical properties of this material.

To summarize, we employ a combination of resistivity, magnetoresistance, and single-crystal X-ray diffraction techniques to probe the superconductivity and charge orders in LaRu3Si2 under pressures up to 40 GPa. This high-pressure approach enables us to map out the response of superconductivity, normal state transport and charge orders to extreme conditions, offering new insights into their interplay and the broader physics of kagome superconductors. Our experiments reveal LaRu3Si2 as a unique member of the kagome superconductor family, in which superconductivity, the normal state, and charge order not only coexist but are strongly intertwined. In particular, we find a clear correlation between superconductivity and the normal-state electronic response associated with T* and Tco,II. This is evidenced by a striking positive relationship between Tc and several key features: the strength of the resistivity anomaly across T*, the pressure induced crossover from long-range to short-range charge order below Tco,II, and the enhancement of MR. LaRu3Si2 exhibits a dome-shaped pressure dependence of Tc, reaching a maximum of 9 K and representing the highest superconducting onset temperature reported among kagome systems. Our results emphasize the need to consider not only the presence of charge order but also its spatial character and its coupling to the electronic and magnetic landscape of the normal state. This study establishes LaRu3Si2 as an important platform for advancing the theoretical and experimental exploration of universal mechanisms underlying tunable superconductivity and charge order in kagome systems and beyond.

Note added: While our work was under review, an independent study46 was published presenting a temperature-pressure superconducting phase diagram that is quantitatively very similar to ours.

Methods

High-pressure resistivity experiments

For high-pressure experiments, a screw-clamped diamond-anvil cell (DAC) manufactured from the nonmagnetic alloy MP35N and equipped with Boehler-Almax design diamond anvils with 500-μm culets was used. The tungsten gasket was insulated with a cubic BN-epoxy mixture. A single crystal sample of suitable size (120 μm × 120 μm × 10 μm) was cut and placed into the central hole of the gasket filled with NaCl as a pressure-transmitting medium. The electrical leads were fabricated from 5-μm-thick Pt foil and attached to the sample in a van der Pauw configuration. Electrical resistivity was measured at different pressures in the temperature range 1.8–300 K in a magnetic field up to 9 T using the electrical transport option of a Physical Property Measurement System (PPMS-9, Quantum Design). The pressure was determined using the ruby scale by measuring the luminescence from the small chips of ruby placed in contact with the sample.

High-pressure X-ray Diffraction experiments

X-ray diffraction was performed at ID2741, ESRF using monochromatic X-rays with a wavelength of 0.3738 Å and a spotsize of 0.6 × 0.6 μm2. The sample was mounted on a membrane driven diamond anvil cell with 70 degrees angular aperture designed at ESRF to reach pressures up to 20 GPa. The pressure cell is made of CuNi2Be. The diamonds were single crystals with Boehler-Almax design and culet sizes of 600 μm. Stainless steel was used as gasket material. Helium was used as the pressure transmitting medium and the applied pressure was measured by the fluorescence of Ruby. The diamond anvil cell was mounted into a Helium flow cryostat (ESRF). The applied pressures were kept constant during cooling by adapting the membrane pressure. X-ray diffraction was collected with a Eiger2 CdTe detector (DECTRIS AG, Baden-Daettwil, Switzerland) in shutterless mode and continuous rotation over 64 degrees with readout every 0.1 degree. CrysAlisPro (Rigaku) was used for data reduction and TDS2EL (ESRF) for reciprocal space reconstructions.

Reporting summary

Further information on research design is available in the Nature Portfolio Reporting Summary linked to this article.

Data availability

The high-pressure X-ray diffraction data is available at https://doi.org/10.15151/ESRF-ES-1402335301. High pressure transport data are available from authors upon request.

References

Syôzi, I. Statistics of Kagome Lattice. Prog. Theor. Phys. 6, 306 (1951).

Guguchia, Z., Khasanov, R. & Luetkens, H. Unconventional charge order and superconductivity in kagome-lattice systems as seen by muon-spin rotation. npj Quantum Materials 8, 41 (2023).

Yin, J.-X., Lian, B. & Hasan, M. Z. Topological kagome magnets and superconductors. Nature 612, 647–657 (2022).

Mielke III, C. et al. Nodeless kagome superconductivity in LaRu3Si2. Phys. Rev. Mat. 5, 034803 (2021).

Guguchia, Z. et al. Tunable anomalous Hall conductivity through volume-wise magnetic competition in a topological kagome magnet. Nat. Commun. 11, 559 (2020).

Kiesel, M. L. & Thomale, R. Sublattice interference in the kagome Hubbard model. Phys. Rev. B 86, 121105 (2012).

Plokhikh, I. & Guguchia, Z. et al. Charge order above room-temperature in a prototypical kagome superconductor La(Ru1−xFex)3Si2. arXiv:2309.09255 (2023).

Barz, H. Ternary transition metal phosphides: High-temperature superconductors. Mater. Res. Bull. PNAS 15, 1489 (1980).

Vandenberg, J.M. & Barz, H. ibid. 15, 1493 (1980).

Ortiz, B. et al. CsV3Sb5: A Z2 Topological Kagome Metal with a Superconducting Ground State. Phys. Rev. Lett. 125, 247002 (2020).

Ortiz, B. et al. Superconductivity in the Z2 kagome metal KV3Sb5. Phys. Rev. Mater. 5, 034801 (2021).

Yin, Q. et al. Superconductivity and normal-state properties of kagome metal RbV3Sb5 single crystals. Chinese Phys. Lett. 38, 037403 (2021).

Jiang, Y.-X. et al. Discovery of topological charge order in kagome superconductor KV3Sb5. Nat. Mater. 20, 1353–1357 (2021).

Mielke III, C. et al. Time-reversal symmetry-breaking charge order in a kagome superconductor. Nature 602, 245–250 (2022).

Neupert, T., Denner, M. M., Yin, J.-X., Thomale, R. & Hasan, M. Z. Charge order and superconductivity in kagome materials. Nat. Phys. 18, 137–143 (2022).

Christensen, M. H., Birol, T., Andersen, B. M. & Fernandes, R. M. Loop currents in AV3Sb5 kagome metals: multipolar and toroidal magnetic orders. Phys. Rev. B 106, 144504 (2022).

Wagner, G., Guo, C., Moll, P. J. W., Neupert, T. & Fischer, M. H. Phenomenology of bond and flux orders in kagome metals. Phys. Rev. B 108, 125136 (2023).

Grandi, F. et al. Theory of nematic charge orders in kagome metals. Phys. Rev. B 107, 155131 (2023).

Guguchia, Z. et al. Tunable unconventional kagome superconductivity in charge ordered RbV3Sb5 and KV3Sb5. Nat. Commun. 14, 153 (2023).

Wang, Z. et al. Electronic nature of chiral charge order in the kagome superconductor CsV3Sb5. Phys. Rev. B 104, 075148 (2021).

Khasanov, R. et al. Time-reversal symmetry broken by charge order in CsV3Sb5. Phys. Rev. Res. 4, 023244 (2022).

Xu, Y. et al. Three-state nematicity and magneto-optical Kerr effect in the charge density waves in kagome superconductors. Nat. Phys. 18, 1470–1475 (2022).

Guo, C. et al. Switchable chiral transport in charge-ordered kagome metal CsV3Sb5. Nature 611, 461–466 (2022).

Yang, S. et al. Giant, unconventional anomalous Hall effect in the metallic frustrated magnet candidate, KV3Sb5. Sci. Adv. 6, 1–7s (2020).

Denner, M., Thomale, R. & Neupert, T. Analysis of charge order in the kagome metal AV3Sb5 (A = K, Rb, Cs). Phys. Rev. Lett. 127, 217601 (2022).

Christensen, M. H., Birol, T., Andersen, B. M. & Fernandes, R. M. Theory of the charge-density wave in AV3Sb5 kagome metals. Phys. Rev. B 104, 214513 (2021).

Tazai, R., Yamakawa, Y., Onari, S. & Kontani, H. Mechanism of exotic density-wave and beyond-Migdal unconventional superconductivity in kagome metal AV3Sb5 (A=K, Rb, Cs). Sci. Adv. 8, eabl4108 (2022).

Park, T., Ye, M. & Balents, L. Electronic instabilities of kagome metals: saddle points and Landau theory. Phys. Rev. B 104, 035142 (2021).

Lin, Y.-P. & Nandkishore, R. M. Complex charge density waves at Van Hove singularity on hexagonal lattices: Haldane-model phase diagram and potential realization in the kagome metals AV3Sb5. Phys. Rev. B 104, 045122 (2021).

Chandan Setty, C., Hu, H., Chen, L., Si, Q. Electron correlations and T-breaking density wave order in a Z2 kagome metal, https://arxiv.org/abs/2105.15204 (2021).

Yang, H. et al. Superconductivity and nematic order in a new titanium-based kagome metal CsTi3Bi5 without charge density wave order. Nat. Commun. 15, 9626 (2024).

Liu, Y. et al. Superconductivity under pressure in a chromium-based kagome metal. Nature 632, 1032–1037 (2024).

Mielke III, C. et al. Charge orders with distinct magnetic response in a prototypical kagome superconductor LaRu3Si2. https://arxiv.org/pdf/2402.16219 (2024).

Giraldo-Gallo, P. et al. Scale-invariant magnetoresistance in a cuprate superconductor. Science 361, 479–481 (2018).

Novak, M., Sasaki, S., Segawa, K. & Ando, Y. Large linear magnetoresistance in the Dirac semimetal TlBiSSe. Phys. Rev. B 91, 041203(R) (2015).

Wei, X. et al. Linear nonsaturating magnetoresistance in kagome superconductor CsV3Sb5 thin flakes. 2D Mater. 10, 015010 (2023).

Das, L. et al. Two-carrier magnetoresistance: applications to Ca3Ru2O7. J. Phys. Soc. Jpn. 90, 054702 (2021).

Li, L., Shen, J., Xu, Z. & Wang, H. Magnetoresistance and hall effect of two-dimensional 2H-NbSe2. Int. J. Mod. Phys. B 19, 275–279 (2005).

LeBoeuf, D. et al. Electron pockets in the Fermi surface of hole-doped high-Tc superconductors. Nature 450, 533–536 (2007).

LeBoeuf, D. et al. Lifshitz critical point in the cuprate superconductor YBa2Cu3Oy from high-field Hall effect measurements. Phys. Rev. B 83, 054506 (2011).

Mezouar, M. et al. The high flux nano-X-ray diffraction, fluorescence and imaging beamline ID27 for science under extreme conditions on the ESRF Extremely Brilliant Source. High Pressure Research 44, 171–198 (2024).

Tranquada, J. M., Sternlieb, B. J., Axe, J. D., Nakamura, Y. & Uchida, S. Evidence for stripe correlations of spins and holes in copper oxide superconductors. Nature 375, 561–563 (1995).

Attfield, J. P. Charge ordering in transition metal oxides. Solid State Sci. 8, 861–867 (2006).

Johannes, M. D., Mazin, I. I. & Howells, C. A. Fermi-surface nesting and the origin of the charge-density wave in NbSe2. Phys. Rev. B 73, 205102 (2006).

Deng, J. et al. Theory of Superconductivity in LaRu3Si2 and Predictions of New Kagome Flat Band Superconductors. arXiv:2503.20867v1 (2025).

Li, Z. et al. Superconducting dome and structural changes in LaRu3Si2 under pressure. Phys. Rev. B 111, 144505 (2025).

Acknowledgements

Z.G. acknowledges support from the Swiss National Science Foundation (SNSF) through SNSF Starting Grant (No. TMSGI2_211750). Z.G. acknowledges usful discussions with Prof. T. Neupert and Dr. M.H. Fischer. I.P. acknowledges support from Paul Scherrer Institute research grant No. 2021_0134. We acknowledge the ESRF for provision of beamtime within the in-house proposal IH-HC-3952, Jeroen Jacobs for preparation and gas loading of the high-pressure cells, Gaston Garbarino for help with the high-pressure cryostat, Mohamed Mezouar for help with aligning the beamline and Stany Bauchau for technical support.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Z.G. conceived and designed the project. Z.G., S.M. and D.J.G. supervised the project. Crystal growth and characterization: H.N., F.v.R. and S.N. High pressure transport experiments, analysis and corresponding discussions: K.M., S.M., C.F. and Z.G. High pressure X-ray diffraction experiments at ESRF, analysis and corresponding discussions: B.W., I.P., C.M.III, V.S., J.N.G., P.K., O.G., E.P., D.J.G. and Z.G. Figure development: Z.G., K.M., B.W., J.N.G. and S.M. Writing of the paper: Z.G. with contributions from all authors. All authors discussed the results, interpretation, and conclusion.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Peer review

Peer review information

Nature Communications thanks the anonymous reviewers for their contribution to the peer review of this work. A peer review file is available.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Ma, K., Plokhikh, I., Graham, J.N. et al. Correlation between the dome-shaped superconducting phase diagram, charge order, and normal-state electronic properties in LaRu3Si2. Nat Commun 16, 6149 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-025-61383-z

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-025-61383-z

This article is cited by

-

Discovery of high-temperature charge order and time-reversal symmetry-breaking in the kagome superconductor YRu3Si2

Nature Communications (2025)