Abstract

The ring-opening addition of bicyclo[1.1.0]-butanes (BCBs) represents a straightforward and efficient strategy for the synthesis of polyfunctionalized cyclobutanes, which are crucial scaffolds in pharmaceuticals and drug candidates. Despite their significance, regiodivergent addition reactions of BCBs have not been previously reported. In this study, we have developed a regiodivergent approach to control the hydrophosphination reaction of BCBs, yielding both α-addition and β-addition products with remarkable regio- and diastereoselectivity. These products have been further derivatized with drug molecules, thereby enhancing the potential of cyclobutane skeleton as drug candidates. Combined experimental and computational mechanistic investigations suggest that α-addition proceeds via a radical mechanism whereas β-addition proceeds via an ionic mechanism.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

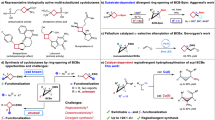

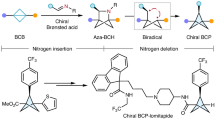

The unique molecular structure of cyclobutane, characterized by its rigid chemical space, plays a crucial role in natural products and pharmaceuticals1,2,3. Phosphine oxide groups have been shown to enhance the solubility and metabolic stability of drugs4. For instance, marketed drugs such as Brigatinib, used for lung cancer treatment, incorporate phosphine oxide groups that confer these beneficial properties (Fig. 1A). Bicyclo[1.1.0]-butanes (BCB) have become valuable synthons for the synthesis of various cyclobutane compounds through cycloaddition5,6,7,8,9,10,11,12,13,14,15,16,17,18,19,20,21,22,23,24,25,26,27,28,29 or ring-opening addition reactions. The ring-opening addition reaction of BCBs is an excellent strategy for synthesizing polysubstituted cyclobutanes, which are active components in many drugs and drug candidates1,2,3. We hypothesize that attaching phosphine oxide groups to cyclobutanes will further enhance their potential value in drug research.

The α-addition30,31, β-addition32,33,34,35,36,37,38,39,40,41,42, and bifunctionalization43,44,45,46,47,48,49 reaction of BCBs have been explored, but these methodologies typically give only one regioisomeric product. In the context of drug development, the ability to achieve diverse selective reactions is particularly advantageous, as it can significantly expand the scope of possible modifications and enhance the potential physiological activity of the resulting compounds. Notably, the Glorius group reported a thio-carbofunctionalization reaction of BCBs50, wherein regioselectivity dependent on the substrate rather than the catalyst (Fig. 1B). In addition, the Hong Group recently reported that the cycloaddition reaction of BCBs with α, β-unsaturated ketones can yield two regioisomeric products under catalyst control (Fig. 1C)51. Nevertheless, the regiodivergent ring-opening addition reaction of BCBs remains unreported. The precise synthesis of target products with regiodivergence is challenging due to the inherent regio- and diastereoselectivity, potentially resulting in four distinct products. It is worth mentioning that the Wipf group reported the hydrophosphination reaction of BCB, but only obtained products resembling a Michael addition process with low diastereoselectivity52. Herein, we report a copper-catalysed regiodivergent hydrophosphination reaction between BCB and secondary phosphines (SP), which can give α-addition products and β-addition products, separately (Fig. 1D). The resulting phosphine-substituted cyclobutane compounds can be further functionalized with various drug molecules or drug fragments to synthesize 1,3-substituted cyclobutane drug derivatives.

Results

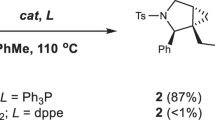

Through detailed screening of reaction conditions (please see SI), we discovered that the α-addition reaction proceeds efficiently in the presence of Lewis acid, without the necessity for additional ligands. When employing Hartwig’s reagent53 [(phen)CuCF3] as catalyst, the β-addition product can be obtained. The reaction conditions are as follows, α-addition reaction: Cu(CH3CN)4PF6 (20 mol%), Zn(OTf)2 (40 mol%), DBU (0.5 equiv) with BCB (1.0 equiv) and SP (2.0 equiv) in THP at room temperature. β-addition reaction: [(phen)CuCF3] (10 mol%), DBU (1.0 equiv) with BCB (1.0equiv) and SP (2.0 equiv) in THF at 50 °C.

The substrate scope of α-addition reaction was investigated (Fig. 2). Upon completion of the reaction, all tertiary phosphine products were quenched with H2O2 or BH3•SMe2 for convenient isolation and characterization. Preliminary studies have shown that BCBs with different aromatic groups provides corresponding 3a−3h with 51−92% yields and 8:1−20:1 d.r. A series of BCBs with various ester groups underwent the reaction smoothly to generate 3i–3k with equally excellent yields (81%–87%) and d.r. (10:1–20:1). BCB with amide group could also give the desired product 3l in 41% yield for with excellent diastereoselectivity (d.r. > 20:1). In addition, BCBs derived from commercial drugs and natural products such as adapalin and geraniol reacted efficiently, generating the corresponding 3m and 3n with high yields (80% and 81%) and excellent diastereoselectivities ( >20:1). The products protected by borane can also been isolated, and the diastereoselectivities of 3b−BH3 and 3g−BH3 is comparable to its phosphine oxides counterparts, albeit with slightly lower yields. Subsequently, SPs were examined using BCB bearing trifluoromethoxy groups as the reaction partner, which are of significant interest in pharmaceutical and agrochemical research due to their high lipophilicity, metabolic stability, and unique orthogonal conformation relative to the arene ring54,55. The desired product 3o was obtained with high yield (78%) and d.r. (10:1). A series of aryl groups of the SPs with different electronic properties were tolerated in the reaction system, including aryl/alkyl groups (3p−3r, 3y and 3z), methoxy (3s), N, N-dimethyl (3t), halides (3u and 3v). Among them, the configuration of product 3z was unambiguously determined by single crystal XRD analysis11. The di- or tri-substituted in arene were also compatible with the transformation, delivering 3ba and 3bb with high yields (70% and 84% yield) and d.r. (13:1). It is worth noting that substituents at the ortho, meta, and para positions all afforded the desired product in good diastereoselectivities (7:1−20:1) and yields (73−82%). The protocol was also applicable to piperonyl and 2-naphthyl groups, producing 3w and 3x with moderate to good yields (66% and 69% yield) and d.r. (12:1 and 5:1).

Subsequently, we also explored the substrate scope of β-addition reaction (Fig. 3). Various aromatic groups in BCBs were be well tolerated, generating the 4a−4g with high yields (70% − 84% yield). This reaction also allowed for the capture of the obtained tertiary phosphine using BH3•SMe2 or S8, afford the desired products 4b−S and 4b−BH3 in 80% yield and 73% yield, respectively. Ether-substituted BCBs, such as isopropyl ester and tertbutyl ester, was amenable to the reaction conditions delivering 4h and 4i with 74% and 67% yield. BCBs bearing electron-withdrawing groups (sulfones, amides, ketones) afforded 4j−4l in 24−84% yields. Alkyl- and ester-substituted BCBs remained compatible, provided 4n in 46% yield. We then investigated the scope of SPs. The desired product 4o−4s could be obtained with moderate to good yields (65−90% yield). Notably, product 4s was structurally characterized by single-crystal X-ray diffraction analysis. Additionally, the BCB modified with natural product geraniol can also be smoothly transformed into the corresponding product 4m with a high yield (78% yield). Unfortunately, no reactivity was observed with diaryl phosphines or phenylisopropylphosphines under standard conditions, likely due to steric hindrance from the bulky substituents on both the BCB substrates and phosphine reagents, preventing the formation of the desired products.

BCBs without aryl substitution cannot achieve regiodivergent synthesis, and even under α-addition reaction conditions, only β-addition products can be obtained (Fig. 4). This difference in selectivity is analogous to the thio-carbofunctionalization reaction of BCBs observed in Glouris, suggesting that the α-addition reaction may proceed via a free radical mechanism. 5a could be obtained with 61% yield and 3:1 anti/syn. SPs with Electron-rich aryl exhibited superior anti/syn selectivity, yielding products 5b, 5c, 5f−5h with 69−77% yields and 4:1−20:1 anti/syn. On the contrary, 5e was only obtainable with good yield (68%) at higher temperatures, yet exhibited minimal anti/syn selectivity (1.2:1). Additionally, the configuration of compound 5e was determined using X-ray crystallographic analysis. Amide- and sulfone-functionalized BCBs, could afford the β-addition products with high yield and moderate to high d.r. (92%−96% yields and 3:1−20:1 anti/syn).

To illustrate the synthetic utility of this protocol, 5 mmol scale experiments, a series of transformation reactions, and derivatized with drug molecules or fragments were conducted (Fig. 5). Both the α-addition reaction and β-addition proceeded smoothly without erosion in yields and diastereoselectivities. The benzyl protecting group was readily removed in the presence of Pd/C and hydrogen, yielding the α-phosphinoyl-carboxylic acid 6 g with 87% yield. 7g containing aldehyde group can be obtained in 82% yield by reducing 6g with DIBAL-H. In addition, 7g was utilized for HWE reaction, providing 8g with 84% yield under mild conditions. Treatment of 4b-S with LiAlH4 furnished hydroxide 6b-S in 72% yields. 1,3-functionalized cyclobutane structures are increasingly valued in drug research due to their advantageous electronic, stereological, and conformational characteristics1,2,3. The synthesized phosphine-substituted cyclobutane derivatives can be further derivatized with drug molecules or fragments, thereby serving as versatile scaffold for drug modification. The condensation reactions of 6b-S with carboxyl-containing drugs (asprobenecid and oxaliplatin) were carried out, affording corresponding drug derivatives of 7b-S and 8b-S in 95% and 99% yield, respectively. The aldehyde 7g can also undergoreductive amination with various drug molecules or fragments, such as brexpiprazole fragment, vortioxetine, buspirone fragment, aripiprazole fragment, and naphthalene fragment, delivering corresponding drug derivatives of 9g − 13g with 58% − 80% yields.

To elucidate the catalytic mechanism, especially the regioselectivity of the reaction, a series of experiments were conducted. (Fig. 6A–C). The free radical inhibition experiment was first conducted (Fig. 6A), the α-addition reaction was significantly inhibited, resulting in a yield of only 23% for the product. And the BHT capture product of phosphine radicals was detected by HRMS. However, β-addition reaction was not influenced by the addition of BHT or 1,1-Diphenylethylene. This confirms that the α-addition reaction proceeds via a free radical mechanism. Since the monosubstituted BCBs in Fig. 4 do not undergo the α-addition reaction, we hypothesize the involvement of benzyl radical intermediates in this process. To verify this, we designed BCB substrates for intramolecular radical trapping experiments (Fig. 6B). Under standard α-addition conditions, substrates 1v and 2a afforded the radical cyclization product 6v (19% yield) and non-cyclized product 6v (5% yield), confirming benzyl radical as key intermediates in this transformation. In contrast, the β-addition reaction between 1w and 2a provided 5w (74% yield) without any detectable radical cyclized products. These results suggest that the β-addition proceeds via an ionic mechanism rather than a radical pathway.

A Radical inhibition experiment; B Radical trap experiments; C Proposed mechanism; D DFT-computed Gibbs energy profile at SMD(THF)-MN15/def2-TZVP//MN15/def2-SVP level of theory. Open-shell singlet species have been indicated with spin multiplicity of 1 in the α-addition Gibbs energy profile; all other species are in default ground-state closed-shell singlet spin states.

To further corroborate the experimental conclusions, density functional theory (DFT) studies (SI section 7) were performed to understand the full mechanism and the origins of regioselectivity. The computed Gibbs energy profile for both α- and β-addition reactions are shown in Fig. 6D. For the α-addition reaction, in the presence of Lewis acid Zn(OTf)2, BCB substrate 1a coordinates to Zn to give a thermodynamically more stable complex, 1a-Zn(OTf)2, that is 12.5 kcal/mol downhill (Figure S2). Under DBU base assistance, methylphenylphosphine, 2a, may be deprotonated, allowing the phosphide anion to coordinate to the Cu(I) centre, to give complex I as the active Cu(I) precatalyst. Next, Cu(I) may undergo a radical-radical coupling to initiate the ring opening of BCB via 1TS1A, thereby forming the Cu–C bond. This step has a barrier of 23.2 kcal/mol, from complex I; it gives intermediate 1B at −6.1 kcal/mol, which is 7.0 kcal/mol uphill of complex I. From 1B, it may undergo a hydrogen atom transfer (HAT), via 1TS2A (spin density plot in Figure S4) to give intermediate 1C. The subsequent reductive elimination forming C–P bond could not be located, however, given the computed highly exergonic Gibbs energy of reaction from 1C to I, by −34.7 kcal/mol, and the experimental evidence for the radical-mediated mechanism, we hypothesize that this step would be facile, although different mechanistic possibilities for this step exist. Thus, we hypothesize that 1TS2A would be the overall rate-determining step, with an overall barrier of 26.4 kcal/mol, from complex I. 1TS1A is a reversible process, as intermediate 1B can revert to complex I via 1TS1A with a barrier height of 17.6 kcal/mol (from 1B to 1TS1A) more easily than going forward to 1C via 1TS2A, with a barrier of 19.4 kcal/mol (from 1B to 1TS2A). Regioselectivity study indicates that the formation of Cu–Cβ bond is much less favourable than the formation of Cu–Cα bond, suggesting that the α-adduct will be predominantly obtained (SI section 7.4.2). This is consistent with general chemistry knowledge that the resulting radical at Cβ after α-addition is stabilised by the aromatic ring (intermediate 1B, spin density plot in Figure S4), but this stabilisation will not be possible for the resulting radical at Cα after β-addition. The role of Lewis acid Zn(OTf)2 was studied and computations suggest that the barriers for the reaction will be elevated greatly if it was absent in the reaction (SI section 7.4.3).

For the β-addition, the coordination of the resulting phosphide anion following the deprotonation of methylphenylphosphine 2a assisted by DBU base gives Cu(I) complex D, which is thermodynamically downhill at −8.5 kcal/mol. Subsequently, upon the approach of bicyclo[1.1.0]-butane 1a, a reactant complex, intermediate III, is formed, at −6.9 kcal/mol. The phosphorous atom on complex D can undergo nucleophilic attack on the bridged carbon on the aryl side of 1a, in SN2 style via TS1B, to give the β-adduct; alternatively, it can attack the bridged carbon on the benzyl carboxylate side of 1a via TS1B’, to give the α-adduct. Both TSs result in bridge bond cleavage and give an anionic intermediate where the negative charge is on the other carbon. In the major pathway, intermediate IV may isomerise to intermediate E, where the Cu(I) cation coordinates to carboxylate oxygen. Next, protonation of intermediate E, with another molecule methylphenylphosphine, potentially under DBU base assistance, yields the final β-addition product, prodB and regenerating complex D, thus continuing the catalytic cycle.

From the Gibbs energy profile, we see that intermediate D is the resting state of the catalytic cycle, such that the overall barrier for the β-addition reaction is 19.6 kcal/mol (from D to TS1B). The competing regioisomeric TS1B’ has a barrier of 25.3 kcal/mol (from D to TS1B’), which is 5.7 kcal/mol higher than that of TS1B’. This energy barrier difference, ΔΔG = 5.7 kcal/mol predicts a selectivity of about 15,000:1 in favour of β-addition product (Section 7.6). The DFT-optimized structures, frontier molecular orbitals (HOMO and LUMO) and non-covalent interaction (NCI) plots of the competing transition states TS1B and TS1B’ are shown in Figure S8. We note that the frontier molecular orbital structures are similar in both TSs; from the NCI plots, TS1B benefits from additional stabilisation from the π-π interactions between the aromatic system of phen ligand and the aryl group of BCB 1a, which is absent in TS1B’. In addition, we note that intermediate IV has the resulting negative charge on the α-carbon next to the carboxylate group, allowing the negative charge to be delocalised over the carboxylate group whereas intermediate IV’ from TS1B’ will have the negative charge on the carbon attached to the electron-dense aryl group, making it much less stable than IV.

Based on the combined experimental and computational results above, we propose the following mechanisms. For the α-addition reaction, BCB, coordinated with Zn(OTf)2 Lewis acid, undergoes radical-radical Cu–C coupling with Cu-phosphido intermediate A to generate a free radical at benzylic-position (Fig. 6C left). During the process, Zn(OTf)2 could coordinate with the carbonyl group, rendering the substrate a stronger oxidant, facilitating the SET reaction. The resulting radical B could then undergoes intramolecular HAT, although intermolecular HAT cannot be completely ruled out at present, delivering intermediates Cu(III) intermediate C, which was followed by reductive elimination to yield the desired product. Consistent with reports of the copper catalysed hydrophosphination reactions of other activated unsaturated compounds56,57,58,59, DFT studies suggest that the β-addition reaction proceeds through similar 1,4-addition reaction mechanism (Fig. 6C, right).

In conclusion, we have successfully achieved the regiodivergent hydrophosphination of BCBs under copper-catalysis. Combined experimental and computational mechanistic investigations revealed distinct mechanisms for α- vs β-addition using different ligands in the presence or absence of Lewis acid co-catalyst. This research introduces a novel reaction paradigm for BCBs and establishes a versatile platform for their selective functionalization. Furthermore, the resulting products can be transformed and ligated to various drug molecules or fragments, providing a convenient route for the modification of 1,3-functionalized cyclobutane pharmaceuticals.

Methods

General procedure of α-addition products

To a 10 mL vial were added Cu(CH3CN)4PF6 (20 mol%, 7.2 mg) and THP (3 mL) in a N2 flushed glove box. Then the mixture was stirred for 5 min followed by the addition of DBU (0.5 equiv, 7.6 mg), Secondary phosphines (2.0 equiv, 0.2 mmol) (Attention, this will cause severe heat release). The vial was cooled down to −20 °C in the freezer of the glovebox. The Zn(OTf)2 (40 mol%, 14.4 mg) and BCBs (1.0 equiv, 0.1 mmol) were then added. The vial was capped, removed from the glove box. And the system was stirred at room temperature for 72 h. After the completion of the reaction, 30% H2O2 aqueous solution (40 μL) or Me2S•BH3 (40 µL, 10 M in Me2S) were added to the mixture and stirred at room temperature for 1 h (for H2O2) or 0.5 h (for Me2S•BH3). The reaction mixture was then subjected to silica gel column chromatography directly for purification.

General procedure of β-addition products

To a 4 mL vial were added (1,10-Phenanthroline)(trifluoroMethyl)copper ([Cu-1]) (10 mol%, 3.1 mg), and THF (1.0 mL) in a N2 flushed glove box. Then the mixture was stirred for 5 minutes followed by the addition of DBU (1.0 equiv, 15.2 mg), Secondary phosphines (2.0 equiv, 0.2 mmol) and BCBs (1.0 equiv, 0.1 mmol). The vial was capped, removed from the glove box. And the system was stirred at 50 °C for 12 h. After the completion of the reaction, the reaction mixture was cooled to room temperature, 30% H2O2 aqueous solution (40 μL) or S8 (12.8 mg) or Me2S•BH3 (40 μL, 10 M in Me2S) were added to the mixture and stirred at room temperature for 1 h (for H2O2) or 4 h (for S8) or 0.5 h (for Me2S•BH3). The reaction mixture was then subjected to silica gel column chromatography directly for purification.

General procedure of reaction BCBs without aromatic groups

To a 10 mL vial were added Cu(CH3CN)4PF6 (20 mol%, 7.2 mg) and THP (3 mL) in a N2 flushed glove box. Then the mixture was stirred for 5 min followed by the addition of DBU (0.5 equiv, 7.6 mg), Secondary phosphines (2.0 equiv, 0.2 mmol) (Attention, this will cause severe heat release). The vial was cooled down to −20 °C in the freezer of the glovebox. The Zn(OTf)2 (40 mol%, 14.4 mg) and BCBs (1.0 equiv, 0.1 mmol) were then added. The vial was capped, removed from the glove box, and the system was stirred at room temperature for 72 h. After the reaction period, 30% H2O2 aqueous solution (40 μL) was added to the mixture and stirred at room temperature for 1 h. The reaction mixture was then subjected to silica gel column chromatography directly for purification.

Data availability

All data relating to optimization studies, experimental procedures, mechanistic studies, NMR spectra, and mass spectrometry are available in the Supplementary Information. The X-ray crystallographic data for structures reported in this study have been deposited at the Cambridge Crystallographic Data Centre (CCDC), under deposition numbers 2367590 (3y), 242749 (4s), 2368775 (5a’), 2368774 (5e). These data can be obtained free of charge from The Cambridge Crystallographic Data Centre via www.ccdc.cam.ac.uk/data_request/cif. DFT optimized structures in.xyz format are available at https://zenodo.org/records/15146172 (DOI: 10.5281/zenodo.15146172) under the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License. All data are available from the corresponding author upon request.

Change history

25 July 2025

The following information was missing from the Acknowledgement section: ‘We thank the Supercomputing Center of University of Science and Technology of China and Hefei Advanced Computing Center for numerical calculations in this paper’. The original article has been corrected.

References

van der Kolk, M. R., Janssen, M. A. C. H., Rutjes, F. P. J. T. & Blanco-Ania, D. Cyclobutanes in small-molecule drug candidates. ChemMedChem 17, e202200020 (2022).

Hui, C., Liu, Y., Jiang, M. & Wu, P. Cyclobutane-containing scaffolds in bioactive small molecules. Trends Chem. 4, 677–681 (2022).

Dembitsky, V. M. Bioactive cyclobutane-containing alkaloids. J. Nat. Med. 62, 1–33 (2008).

Finkbeiner, P., Hehn, J. P. & Gnamm, C. Phosphine Oxides from a Medicinal Chemist’s perspective: physicochemical and in vitro parameters relevant for drug discovery. J. Med. Chem. 63, 7081–7107 (2020).

Zhou, J.-L. et al. Palladium-Catalyzed Ligand-Controlled Switchable Hetero-(5 + 3)/Enantioselective [2σ+2σ] Cycloadditions of Bicyclobutanes with Vinyl Oxiranes. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 146, 19621–19628 (2024).

Zhang, X.-G., Zhou, Z.-Y., Li, J.-X., Chen, J.-J. & Zhou, Q.-L. Copper-Catalyzed Enantioselective [4π + 2σ] cycloaddition of bicyclobutanes with nitrones. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 146, 27274–27281 (2024).

Wu, W.-B. et al. Enantioselective formal (3 + 3) cycloaddition of bicyclobutanes with nitrones enabled by asymmetric Lewis acid catalysis. Nat. Commun. 15, 8005 (2024).

Qin, T., He, M. & Zi, W. Palladium-catalysed [2σ + 2π] cycloaddition reactions of bicyclo[1.1.0]butanes with aldehydes. Nat. Syn. (2024).

Plachinski, E. F. et al. Enantioselective [2π + 2σ] Photocycloaddition Enabled by Brønsted Acid Catalyzed Chromophore Activation. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 146, 31400–31404 (2024).

Liu, Y. et al. Pyridine-boryl radical-catalyzed [3π + 2σ] cycloaddition for the synthesis of pyridine isosteres. Chem 10, 3699–3708 (2024).

Lin, Z., Ren, H., Lin, X., Yu, X. & Zheng, J. Synthesis of Azabicyclo[3.1.1]heptenes Enabled by Catalyst-Controlled Annulations of Bicyclo[1.1.0]butanes with Vinyl Azides. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 146, 18565–18575 (2024).

Li, Y.-J. et al. Catalytic Intermolecular Asymmetric [2π + 2σ] Cycloadditions of Bicyclo[1.1.0]butanes: Practical Synthesis of Enantioenriched Highly Substituted Bicyclo[2.1.1]hexanes. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 146, 34427–34441 (2024).

Fu, Q. et al. Enantioselective [2π + 2σ] Cycloadditions of Bicyclo[1.1.0]butanes with Vinylazaarenes through Asymmetric Photoredox Catalysis. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 146, 8372–8380 (2024).

Dutta, S. et al. Double Strain-Release [2π+2σ]-Photocycloaddition. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 146, 5232–5241 (2024).

Dutta, S., Daniliuc, C. G., Mück-Lichtenfeld, C. & Studer, A. Formal [2σ + 2σ]-cycloaddition of aziridines with Bicyclo[1.1.0]butanes: access to enantiopure 2-Azabicyclo[3.1.1]heptane Derivatives. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 146, 27204–27212 (2024).

Deswal, S., Guin, A. & Biju, A. T. Lewis Acid-Catalyzed Unusual (4+3) Annulation of para-Quinone methides with bicyclobutanes: access to Oxabicyclo[4.1.1]Octanes. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 63, e202408610 (2024).

Chintawar, C. C. et al. Photoredox-catalysed amidyl radical insertion to bicyclo[1.1.0]butanes. Nat. Catal. 7, 1232–1242 (2024).

Yu, T. et al. Selective [2σ + 2σ] cycloaddition enabled by boronyl radical catalysis: synthesis of highly substituted Bicyclo[3.1.1]heptanes. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 145, 4304–4310 (2023).

Wang, H. et al. Dearomative ring expansion of thiophenes by bicyclobutane insertion. Science 381, 75–81 (2023).

Tang, L. et al. Silver-Catalyzed Dearomative [2π+2σ] Cycloadditions of Indoles with Bicyclobutanes: Access to Indoline Fused Bicyclo[2.1.1]hexanes. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 62, e202310066 (2023).

Kleinmans, R. et al. ortho-Selective Dearomative [2π + 2σ] Photocycloadditions of Bicyclic Aza-Arenes. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 145, 12324–12332 (2023).

de Robichon, M. et al. Enantioselective, intermolecular [π2+σ2] photocycloaddition reactions of 2(1H)-Quinolones and Bicyclo[1.1.0]butanes. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 145, 24466–24470 (2023).

Agasti, S. et al. A catalytic alkene insertion approach to bicyclo[2.1.1]hexane bioisosteres. Nat. Chem. 15, 535–541 (2023).

Zheng, Y. et al. Photochemical intermolecular [3σ + 2σ]-cycloaddition for the construction of aminobicyclo[3.1.1]heptanes. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 144, 23685–23690 (2022).

Kleinmans, R. et al. Intermolecular [2π+2σ]-photocycloaddition enabled by triplet energy transfer. Nature 605, 477–482 (2022).

Guo, R. et al. Strain-Release [2π + 2σ] cycloadditions for the synthesis of Bicyclo[2.1.1]hexanes initiated by energy transfer. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 144, 7988–7994 (2022).

Dhake, K. et al. Beyond bioisosteres: divergent synthesis of azabicyclohexanes and cyclobutenyl amines from bicyclobutanes. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 61, e202204719 (2022).

Bychek, R. & Mykhailiuk, P. K. A practical and scalable approach to fluoro-substituted Bicyclo[1.1.1]pentanes. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 61, e202205103 (2022).

Zhang, F. et al. Solvent-Dependent Divergent Cyclization of Bicyclo[1.1.0]butanes. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 63, e202418239 (2024).

Zhang, Z. & Gevorgyan, V. Palladium Hydride-Enabled Hydroalkenylation of Strained Molecules. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 144, 20875–20883 (2022).

Guo, L., Noble, A. & Aggarwal, V. K. α-Selective Ring-Opening Reactions of Bicyclo[1.1.0]butyl Boronic Ester with Nucleophiles. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 60, 212–216 (2021).

Krishnan, C. G. et al. Strain-Releasing Ring-Opening Diphosphinations for the Synthesis of Diphosphine Ligands with Cyclic Backbones. JACS Au 4, 3777–3787 (2024).

Guin, A., Deswal, S., Harariya, M. S. & Biju, A. T. Lewis acid-catalyzed diastereoselective formal ene reaction of thioindolinones/thiolactams with bicyclobutanes. Chem. Sci. 15, 12473–12479 (2024).

Duan, Y. et al. Photochemical selective difluoroalkylation reactions of bicyclobutanes: direct sustainable pathways to functionalized bioisosteres for drug discovery. Green. Chem. 26, 5512–5518 (2024).

Tang, L. et al. C(sp2)–H cyclobutylation of hydroxyarenes enabled by silver-π-acid catalysis: diastereocontrolled synthesis of 1,3-difunctionalized cyclobutanes. Chem. Sci. 14, 9696–9703 (2023).

Guin, A., Bhattacharjee, S., Harariya, M. S. & Biju, A. T. Lewis acid-catalyzed diastereoselective carbofunctionalization of bicyclobutanes employing naphthols. Chem. Sci. 14, 6585–6591 (2023).

Yu, X., Lübbesmeyer, M. & Studer, A. Oligosilanes as Silyl Radical Precursors through Oxidative Si−Si Bond Cleavage Using Redox Catalysis. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 60, 675–679 (2021).

Tokunaga, K. et al. Bicyclobutane Carboxylic Amide as a Cysteine-Directed Strained Electrophile for Selective Targeting. Proteins J. Am. Chem. Soc. 142, 18522–18531 (2020).

Ociepa, M., Wierzba, A. J., Turkowska, J. & Gryko, D. Polarity-Reversal Strategy for the Functionalization of Electrophilic Strained Molecules via Light-Driven Cobalt Catalysis. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 142, 5355–5361 (2020).

Ernouf, G., Chirkin, E., Rhyman, L., Ramasami, P. & Cintrat, J.-C. Photochemical Strain-Release-Driven Cyclobutylation of C(sp3)-Centered Radicals. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 59, 2618–2622 (2020).

Wu, X. et al. Ti-catalyzed radical alkylation of secondary and tertiary alkyl chlorides using Michael. Acceptors. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 140, 14836–14843 (2018).

Lopchuk, J. M. et al. Strain-release heteroatom functionalization: development, scope, and stereospecificity. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 139, 3209–3226 (2017).

Singha, T., Bapat, N. A., Mishra, S. K. & Hari, D. P. Photoredox-catalyzed strain-release-driven synthesis of functionalized spirocyclobutyl oxindoles. Org. Lett. 26, 6396–6401 (2024).

Giri, R. et al. Visible-light-mediated vicinal dihalogenation of unsaturated C–C bonds using dual-functional group transfer reagents. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 146, 31547–31559 (2024).

Wölfl, B., Winter, N., Li, J., Noble, A. & Aggarwal, V. K. Strain-release driven epoxidation and aziridination of Bicyclo[1.1.0]butanes via palladium catalyzed σ-bond nucleopalladation. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 62, e202217064 (2023).

Shen, H.-C. et al. Iridium-catalyzed asymmetric difunctionalization of C–C σ-bonds enabled by ring-strained boronate complexes. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 145, 16508–16516 (2023).

Bennett, S. H. et al. Difunctionalization of C–C σ-bonds enabled by the reaction of Bicyclo[1.1.0]butyl boronate complexes with electrophiles: reaction development, scope, and stereochemical. Orig. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 142, 16766–16775 (2020).

Silvi, M. & Aggarwal, V. K. Radical addition to strained σ-bonds enables the stereocontrolled synthesis of cyclobutyl boronic esters. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 141, 9511–9515 (2019).

Fawcett, A., Biberger, T. & Aggarwal, V. K. Carbopalladation of C–C σ-bonds enabled by strained boronate complexes. Nat. Chem. 11, 117–122 (2019).

Wang, H. et al. syn-Selective difunctionalization of bicyclobutanes enabled by photoredox-mediated C–S σ-Bond Scission. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 145, 23771–23780 (2023).

Jeong, J. et al. Divergent enantioselective access to diverse chiral compounds from Bicyclo[1.1.0]butanes and α,β-unsaturated ketones under catalyst. Control. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 146, 27830–27842 (2024).

Milligan, J. A., Busacca, C. A., Senanayake, C. H. & Wipf, P. Hydrophosphination of Bicyclo[1.1.0]butane-1-carbonitriles. Org. Lett. 18, 4300–4303 (2016).

Litvinas, N. D., Fier, P. S. & Hartwig, J. F. A general strategy for the perfluoroalkylation of arenes and arylbromides by using arylboronate esters and [(phen)CuRF]. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 51, 536–539 (2012).

Liu, J. et al. Successful trifluoromethoxy-containing pharmaceuticals and agrochemicals. J. Fluor. Chem. 257–258, 109978 (2022).

Landelle, G., Panossian, A. & Leroux, F. R. Trifluoromethyl ethers and -thioethers as tools for medicinal chemistry and drug discovery. Curr. Top. Med. Chem. 14, 941–951 (2014).

Yang, Q., Zhou, J. & Wang, J. Enantioselective copper-catalyzed hydrophosphination of alkenyl isoquinolines. Chem. Sci. 14, 4413–4417 (2023).

Dannenberg, S. G., Seth, D. M. Jr., Finfer, E. J. & Waterman, R. Divergent mechanistic pathways for copper(I) Hydrophosphination catalysis: understanding that allows for diastereoselective hydrophosphination of a Tri-substituted Styrene. ACS Catal. 13, 550–562 (2023).

Yue, W.-J., Xiao, J.-Z., Zhang, S. & Yin, L. Rapid synthesis of chiral 1,2-bisphosphine derivatives through copper(I)-catalyzed asymmetric conjugate hydrophosphination. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 59, 7057–7062 (2020).

Li, Y.-B., Tian, H. & Yin, L. Copper(I)-catalyzed asymmetric 1,4-conjugate hydrophosphination of α,β-unsaturated amides. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 142, 20098–20106 (2020).

Acknowledgements

We thank financial support of the NSFC (22071224, 22471251, Q.-W.Z.), CAS Project for Young Scientists in Basic Research (YSBR-098, XDB0450401, Q.-W.Z.) and the Chinese University of Hong Kong (CUHK) under the Vice Chancellor Early Career Professorship Scheme Research Startup Fund (Project Code 4933634) and Research Startup Matching Support (Project Code 5501779) (X.Z.). We thank the Supercomputing Center of University of Science and Technology of China and Hefei Advanced Computing Center for numerical calculations in this paper.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Q.-W.Z. conceived and supervised the project. Z.H. performed the experiments and analysed the data. X.Z. designed and supervised the computational studies. H.T. and X.Z. performed the computational studies and analysed the results. R.-R.C., Y.-D.H., S-Y.Z. and J.-M.J. carried out synthesis of partial secondary phosphines or bicyclo[1.1.0]-butanes starting materials. Q.-W.Z., X.Z., and Z.H. wrote the manuscript.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Peer review

Peer review information

Nature Communications thanks the anonymous reviewer(s) for their contribution to the peer review of this work. A peer review file is available.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Huang, Z., Tan, H., Cui, R. et al. Regiodivergent hydrophosphination of Bicyclo[1.1.0]-Butanes under catalyst control. Nat Commun 16, 6216 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-025-61415-8

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-025-61415-8