Abstract

The four-way DNA junction is the most prevalent structural motif in DNA nanotechnology. Recently, a reconfigurable DNA nanoarray (domino array) was created with this basic motif to realize intricate, stepwise transformation by the information relay between neighboring four-way junction units. Here, we generate a DNA domino array with same sequences at every junction, and use it as a platform to study how the design of DNA bases at junctions influences the kinetics and thermodynamics of transformation of four-way junctions in reconfigurable DNA nanoarrays. By regulating the energy difference and thus the conversion between the two configurations of four-way junctions, we show the transformation of DNA nanoarray can be modulated in a designable manner. The coordinated transformation of four-way junctions in the DNA domino array enables a detailed investigation on array transformation by using Atomic Force Microscopy (AFM) imaging and single-molecule Förster resonance energy transfer (FRET) microscopy.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

In past decades, DNA self-assembly was utilized to construct custom-designed, intricate nanoobjects. Various approaches were developed, including DNA tiles1,2,3, DNA bricks4,5,6 and DNA origami7,8. These versatile methods were used to fabricate not only increasingly more complex DNA nanostructures6,8,9,10,11,12,13,14, but also sophisticated nanomachines that are capable of performing prescribed motions15,16,17 and carrying out designated tasks18. Interestingly, many of the state-of-the-art nanostructures are still largely constructed by using a structural motif called immobile four-way junction (an adaptation from Holliday Junction19), which was invented by Seeman at the dawn of DNA nanotechnology20. Since its conception, immobile DNA four-way junctions, as well as its variants (e.g., 3, 5, or 6-way junctions), have been extensively used in DNA tiles, including the double-crossover DNA tiles2, the assembly of the first two-dimensional DNA nanoarrays21, and later the powerful, versatile DNA origami7,8.

Natural Holliday junction participates in the gene recombination process and can slide along DNA strands due to the symmetrical sequences at the junction, and plenty theoretical and experimental studies have characterized the structure and dynamics of Holliday junction, including immobilized Holliday Junction. For example, it has been shown that magnesium concentration22 and sequence near the junction position23,24,25 could affect the ratio of two stacked conformational isomers. Other factors were reported to the contribution of the observed isomer ratios, such as the geometric constraints imposed at the junction core26, and the sequence-dependent electrostatic potential27 on junction stacking preferences. MD simulations of J1 and J24 junction sequences demonstrated that stacking and geometric factors contributed to their structural changes28. Besides, the dynamics of individual Holliday junction have been studied using single-molecule fluorescence methodology22,29,30,31.

It is understood that a Holliday junction exhibits a one-helix-over-the-other-helix, X-shaped conformation (Fig. 1a) with an inter-helix angle of ~60°32. However, the conformation of a four-way junction in a DNA nanostructure is generally different. In most cases (e.g., in a typical DNA origami nanoarray), the conformation of four-way junctions is restricted by the surrounding DNA helices, leading to the four arms being forced into a plane (Fig. 1b), as observed in microscopy imaging7,33. Therefore, although it is certain that the sequence design of four-way junctions influences the stability and dynamics of DNA nanostructures, elucidating this sequence effect needs to be done in situ in DNA nanostructures. To this end, it was recently shown that the sequences of Holliday junctions had strong impact on DNA crystal formation34, and on the thermodynamics of DNA origami35. However, it remains challenging to design experiments to explore the effect of junction sequences on the reconfiguration processes of dynamic DNA origami in detail.

a Top and side view of a free-stranding Holliday junction, which exhibits the X-shaped conformation with an inter-helix angle of ~60°. b Generally, the four arms of a junction are confined into a plane by the surrounding DNA helices in a DNA nanostructure. c Simplified energy model for DODA transformation. d Schematics showing the step-by-step transformation of the DODA used in this work. e Detailed view of a junction in the DODA under conformation I and II. The blue strands and gray strands represent scaffold DNA and staple DNA, respectively. The four base pairs at the junction are highlighted to illustrate the different stacking patterns in junction configuration i and configuration ii.

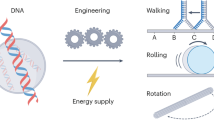

We previously established a DNA Origami Domino Array (DODA), which comprises many reconfigurable four-way Junctions (RJ)33,36,37. Under normal assembly conditions, a DODA predominantly adapts a conformation in which the scaffold DNA strand goes back and forth along each DNA double helix in a raster pattern. This conformation of DODA contains a few unpaired DNA scaffold loops that can bind to complementary trigger DNA strands to initiate a cascading transformation of individual RJs (Fig. 1c, d). When the reaction reaches completion, the DODA is converted to its final conformation, in which every RJ is transformed (Fig. 1e). In this study, the initial conformation and the final conformation are referred to as conformation I and II, and their corresponding RJ configurations are referred as configuration i and ii, respectively. Since we can consider RJs as the basic structural units of a DODA, it was believed that the assembly and reconfiguration of DODA can be regulated via designing sequences of RJs, particularly the eight base pairs at the junction (Fig. 1e). However, previous DODAs used M13 viral DNA as the scaffold, preventing any de novo design on RJ sequences. Recent development in custom DNA scaffold engineering38,39,40, particularly the pscaf method38, provides new tools for constructing DODAs with fully designable RJ sequences. Here, in this work, we design a DODA that contains four columns (5, 4, 5, 4 junctions in each column) of RJs (Fig. 1c) for systematic study of sequence effects on DODAs. Unlike the M13-scaffolded DODA, every RJ in a DODA was designed to contain identical eight base pairs at the junction by using custom-designed pscaf. Such a design strategy effectively amplifies the effect of sequences and enables our investigation on sequence effects in RJs and DODAs with Atomic Force Microscopy (AFM) imaging and single-molecule fluorescence imaging. The knowledge generated in this study can be used not only for programming transformation of DODAs but also for constructing custom-scaffolded DNA origami with designable junction sequences.

Results

There are 256 possible combinations (some would result in identical junction sequences if symmetry is taking into consideration) for the four base pairs at the junction. We estimated the free energy (ΔG) of configuration i and configuration ii based on previously published results41 (Supplementary Fig. 1). It is worth pointing out that the ΔGs of configuration i and configuration ii are expected to be substantially different from ΔGs of free-standing Holliday junctions, due to the fact that the RJs in DODA are confined by surrounding DNA (Fig. 1b; the four-way junction has a flat X-shape, which probably leads to weakened base stacking at the junction position). Nonetheless, we expect the estimated ΔGs provide a foundation for design DODAs with different assembly and transformation behaviors. Instead of exhaustively testing every combination, we selected three sets of sequence design (Fig. 2a). In this study, we selected a set of sequences that should generate the maximum energy differentials between the junction configuration i and ii (e.g., maximum difference between ΔGi and ΔGii), which may facilitate array transformation and improve data quality in single-molecule FRET experiments. As the result, G junction consists of four DNA base pairs that have largest \({\Delta G}_{i}-{\Delta G}_{{ii}}\) and therefore should favor junction configuration ii. The sequence of R junction is effectively the reverse of the G junction, and should favor junction configuration i. N junction is designed to contain a set of symmetric sequences, so that its configuration i and configuration ii have exactly the same arrangement of four base pairs at the junction and presumably the same ΔGs. It is worth noting that there are many possible symmetric sequences, and this work only tested one design (Supplementary Fig. 2). There are many sequence options for N junctions, and the choice of current design in this study is largely arbitrary. It is worth noting that although it is expected that ΔGi would be equal to ΔGii in various sequence choices for N junctions, the sequences can still significantly impact the transformation, particularly the reaction kinetics. The DODAs with custom-designed junctions were designed in cadnano42 (Supplementary Fig. 3), and custom-designed scaffolds for different junction designs were produced by using reported method38 (Supplementary Figs. 4–6).

a Three representative junction designs used in this study with different sequences for the eight base pairs at the junction position. Based the analysis on base stacking, G junction favors configuration ii and R junction favors i, while N junction favors neither. The DODAs made with these three junction designs have identical sequences across the structures, except for the base pairs at the 22 junctions. b Percentages of conformation II in one-pot assembly of DODAs with different number of triggers. The percentages of conformation II for G-DODA with 0–5 triggers were 0%, 0.5 ± 0.9%, 53.4 ± 6.0%, 97.9 ± 1.2%, 99.3 ± 1.1% and 100%, respectively. The percentages of conformation II for N-DODA with 0–5 triggers were 0%, 1.0 ± 0.9%, 37.8 ± 5.0%, 84.1 ± 5.7%, 96.8 ± 2.4% and 100%, respectively. The percentages of conformation II for R-DODA with 0–5 triggers were 0%, 0%, 7.8 ± 4.8%, 74.5 ± 12.3%, 94.9 ± 4.4% and 99.3 ± 1.1%, respectively. Error bars represent the mean values ± standard deviation of samples in AFM images (N = 3). G, N, and R represent G-, N-, and R-DODAs, respectively. c Representative AFM images of conformation I and II for G-DODA. Scale bars: 200 nm. Source data are provided as a Source Data file.

The one-pot assembly of three DODAs that contain purely G junction (G-DODA), N junction (N-DODA), and R junction (R-DODA), respectively, was investigated via agarose gel electrophoresis and AFM imaging (Supplementary Figs. 7–13). Without triggers, all three DODAs produced only conformation I, suggesting the origami design (scaffold routing) strongly favors conformation I and is sufficient to overcome energy difference induced by the junction sequence design. However, when trigger strands were included in the samples, the three DODAs exhibited different behaviors. The addition of all five trigger strands resulted in almost complete transformation to conformation II for the three DODAs. The reduction of the number of triggers to 4, 3, 2, and 1 clearly revealed the junction sequence design has changed the assembly of DODAs in a way that largely matches with our prediction (Fig. 2b). Percentages of conformation I and conformation II are calculated by analysis of AFM images in this work. Two examples of conformation I (R-DODA without trigger) and conformation II (G-DODA with all five triggers) are shown in Fig. 2c. In all cases, the percentages of conformation II follow a trend of G-DODA > N-DODA > R-DODA. For example, G-DODA, N-DODA, and R-DODA assembled with three triggers generated 97.9 ± 1.2%, 84.2 ± 5.7%, and 74.5 ± 12.4% of DODA in conformation II. The percentages of conformation II decreased when fewer triggers were added, which is in good agreement with the model in Fig. 1c. In absence of trigger DNA strands, the free energy of conformation I is significantly lower than the free energy of conformation II. The addition of each trigger DNA strand increases the free energy of conformation I until it eventually becomes higher than that of conformation II.

Because the only design variant between the G-, R-, N-DODAs is their junction sequences, we believe the differences in terms of the percentages of conformation II for these DODAs are the direct result of thermodynamic properties of individual junctions. Therefore, this design of DODAs provide a system for understanding single junctions by studying DNA arrays: Because the assembly and transformation behavior of a DODA represent the collective behavior of all junctions (with same junction sequences), studying DODA enables us to understand the single junctions by means (e.g., AFM) that cannot be directly applied on the small units.

We then extended our study to understanding transformation of DODAs with different junction sequences and various numbers of triggers. Three DODAs were incubated with different numbers of triggers at 50 °C overnight. The agarose gel-purified samples were imaged under AFM for counting the fraction of conformation II in the samples. The transformation results were overall consistent with the one-pot assembly (Supplementary Figs. 14–17). For each DODA design, the conformation II ratios increased with the addition of more triggers. With the same number of triggers added (2–5 triggers), G-DODA had higher transformation yield than N-DODA, followed by R-DODA.

Next, the transformation was studied with single-molecule experiments by using TIRF microscopy. A FRET array was designed for investigating transformation kinetics: A FRET pair composed of a red ATTO647N donor and an IowaBlack@RQ quencher was placed on the DODA nanoarray43 (Fig. 3a and Supplementary Fig. 18a). Under the initial conformation I, the donor and quencher are in proximity and thus the fluorescence of ATTO647N is quenched. After transformation to conformation II, the distance between the dye and quencher increases (from ~3 nm to 6.8 nm), resulting in enhanced fluorescence. The DODA was also modified with a biotinylated DNA strand that binds to the unused scaffold, allowing capturing of the DODA on BSA-biotin-NeutrAvidin-coated glass coverslips. A green ATTO542 dye label DNA strand was also incorporated in the DODA for identification of the array on surface for single-molecule fluorescence analysis on array transformation. We recorded fluorescence images of the DNA origami array structures before and after overnight incubation with and without different numbers of DNA staples at 37 °C on a total internal reflection fluorescence (TIRF) microscope and quantified the transformation yield of the DNA origami array structures from them. Consistent with the results observed in AFM assay (Fig. 2b), we observed the highest transformation yields for the G structure, followed by both the N and the R structure (Supplementary Fig. 18b).

a Design of DODA for fluorescence experiments. An ATTO647N and a quencher were labeled on the DNA strands on the left side of DNA origami arrays. Before transformation, fluorescence was quenched due to the close proximity with the quencher. After transformation, the fluorescence was enhanced due to the increased distance between ATTO647N and quencher. b Histograms showing percentages of transformed DODAs with two triggers at different time points via single-molecule fluorescence measurement repeated three times. c Representative fluorescence traces for single structure transformation of three DODAs. The black line represented the background signals. d Top: accumulative fluorescence signals from single-molecule fluorescence measurement showing the overall transformation kinetics of three DODAs with two triggers. The experiments were performed three times at 37 °C. Below: Apparent transformation rate constant k obtained from the kinetics data 0.126 ± 0.040 min−1, 0.080 ± 0.006 min−1, and 0.018 ± 0.005 min−1 for G-, N-, R-DODAs, respectively. Error bars represent the mean values ± standard deviation of the three experiments. e to i Transformation kinetic study on ensemble samples with different numbers of triggers by using real-time PCR. Top: ensemble fluorescence for the transformation of three DODAs with different number of triggers. The experiments were performed for three times at 30 °C. Below: The apparent rate constant k for three DODAs with different number of trigger input during the transformation. The k for G-, N-, R-DODAs with five triggers are 0.124 ± 0.011/min, 0.117 ± 0.010/min, and 0.078 ± 0.006/min, respectively. The k for G-, N-, R-DODAs with four triggers are 0.088 ± 0.014/min, 0.077 ± 0.022/min, and 0.064 ± 0.011/min, respectively. The k for G-, N-, R-DODAs with three triggers are 0.071 ± 0.007/min, 0.052 ± 0.002/min and 0.035 ± 0.003/min, respectively. The k for G-, N-, R-DODAs with two triggers are 0.028 ± 0.001/min, 0.024 ± 0.001/min, and 0.006 ± 0.001/min, respectively. Error bars represent the mean values ± standard deviation of the three experiments. G, N, and R represent G-, N-, and R-DODAs, respectively. Source data is provided as a Source Data file.

We then carried out real-time single-molecule imaging (time-lapse imaging with a 100 ms frame every 2 s, in order to guaranty single molecule trajectories for up to 20 min) on the FRET DODA in presence of various numbers of trigger strands (Fig. 3b, i). For instance, upon addition of two trigger strands at 37 °C, G-, N- and R-DODA exhibited distinctly different behaviors in terms of the transformation time, which was defined as the time from the addition of the DNA triggers to the signal jump (See Fig. 3b, c for single molecule data and example of real time fluorescence trace of individual DODA). Transformation kinetics of G-, N-, and R-DODA were calculated on the basis of percentages of transformed DODAs over time (Fig. 3d, see more discussion about DODA transformation in Methods Section, multi-step kinetics): G-DODA showed the fastest apparent rate constant of 0.126 ± 0.040 min−1, while N-DODA showed an apparent rate constant of 0.080 ± 0.006 min−1, and R-DODA transformed under the slowest apparent rate constant of 0.018 ± 0.005 min−1.

Next, the real-time ensemble FRET assay was applied for studying transformations of G-, N-, and R-DODAs. The samples were monitored at 30 °C–50 °C for 50 min to study the temperature effect on the transformation kinetics (Supplementary Fig. 19). We noted a significantly faster increase in fluorescence intensity for all three structures upon incubation with five trigger DNA staples, and the transformation kinetics for three DODAs increased with temperature. Notably, for the G and N structure, the transformation occurred quasi-simultaneously upon incubation with all five trigger strands. In contrast, a time delay between the transformation in the R and the G and N structure was noticed upon incubation with all five trigger DNA strands. The time delay between R-DODA and G or N-DODAs became smaller with increased temperature, but G- and N-DODA could not be resolved in the temperature range 30 °C–50 °C. We further studied the transformation of G-, N-, and R-DODAs with 5, 4, 3, 2, or 1 trigger (s) at 30 °C (Fig. 3e–i). Like the Supplementary Fig. 19, the G- and N-DODAs had similar apparent k (0.124 ± 0.011/min, 0.117 ± 0.010/min), and R-DODA had smaller apparent k (0.078 ± 0.006/min) with five triggers input. The transition kinetics were slowed down gradually when the number of trigger DNA strands was reduced. Notably, when adding only the upper four trigger DNA strands, we noticed a difference in the transformation kinetics of the G and the N structure (0.088 ± 0.014/min and 0.077 ± 0.022/min). Further reduction of the number of trigger DNA strands to three or two slowed down the ensemble kinetics but could still differentiate their kinetics, while the transformation process was not initiated at all upon incubation with no trigger or only 1 DNA trigger. In combination, this set of data shows that the DODA transformation kinetics can be finely tuned by changing trigger strands, temperature, buffers, in addition to junction sequences. It is worth pointing out that the kinetics of these transformations were approximated with a single exponential decay function, which should give us an estimate of the average transformation speed, while the actual reactions are likely more complex, considering the multistep nature of the transformation of the DODAs. For example, when five triggers were added to G-, N-, R-DODA, the transformation took various times to reach maximum reaction rates (Supplementary Fig. 20). Particularly, the G-DODA not only exhibited overall faster reaction rate, but also is fastest in the first stage of reaction, likely due to the fact that the G-DODA averagely requires fewer triggers (thus shorter time) to initiate the transformation.

We then studied DODA transformation under various concentrations of Mg2+ and Na+, because it is expected that monovalent or divalent cations would have a strong influence on the transformation kinetics. Since it is known that higher Mg2+ can enhance base-stacking39, as anticipated, we observed faster transformations for R-DODA when the Mg2+ concentration was changed from 6 mM to 500 mM NaCl was added (Supplementary Fig. 21), suggesting the weakening of base-stacking under lower Mg2+ allows the transformation to take place faster.

The kinetics of DODA transformations observed experimentally can be qualitatively explained by the difference in activation energy (Ea) associated with the breaking of base-stacking at junctions (Supplementary Fig. 22a; Note only a single junction was shown). However, since a DODA is a collection of junctions with identical junction sequences, the Ea of the three sets junction sequences (G, N, R) can be calculated by the sum of the free energy of four base-pair stacking (Supplementary Fig. 22c, e)41. Among them, G junction indeed has the lowest Ea, and R junction has the highest Ea, consistent with the observed kinetics in both single-molecule and ensemble assays.

After gaining a clear understanding on how junction sequences and base-stacking at junctions regulate the kinetic and thermodynamic properties of DODAs, we aimed to explore other options to module the junctions and thus regulate DODA transformation. First, we incorporated mismatches at the junctions, and the base-stacking is expected to be eliminated or significantly weakened due to the mismatches. To explore this, we designed and tested three types of mismatches at junction (Fig. 4a): (1) M1 is a symmetric design that contains mismatches on the positions B5/B6 and B3/B4 in the configuration i. (2) M2 contains mismatches on B3/B4 and B7/B8 in configuration i, and is expected to favor configuration i. (3) M3 is a reversed design to M2, and it is expected to favor configuration ii. Based on our understanding in the DODA transformation, we hypothesized simple transformation energy models corresponding to the Incorporation of different mismatches (Fig. 4b).

a Schematics of three designs of mismatches at the junction. b Simple free energy model corresponding to DODAs with three types of mismatches. c Percentages of conformation II for the G-DODA and its mismatched variants in one-pot assembly, in presence of various numbers of triggers. The percentages for G-DODA with 0–5 triggers are 0%, 0%, 54.0 ± 7.7%, 97.4 ± 23.0%, 98.9 ± 1.9% and 100%, respectively. The percentages for G_M1 with 0–5 triggers are 0%, 0%, 7.1 ± 6.3%, 97.3 ± 0.8%, 97.8 ± 3.7% and 100%, respectively. The percentages for G_M2 with 1–5 triggers are 0%, 2.2 ± 2.1%, 21.9 ± 9.3%, 60.1 ± 1.7%, 99.3 ± 1.1% and 100%, respectively. Error bars represent the mean values ± standard deviation of samples in AFM images (N = 3). d Percentages of conformation II for the R-DODA and its mismatched variants. The percentages for R-DODA with 0–5 triggers are 0%, 0.4 ± 0.7%, 6.8 ± 3.9%, 73.5 ± 11.5%, 91.7 ± 4.6% and 100%, respectively. The percentages for R_M1 with 0–5 triggers are 0%, 0%, 7.6 ± 5.4%, 60.4 ± 2.3%, 97.5 ± 2.2% and 100%, respectively. The percentages for R_M3 with 0–5 triggers are 0%, 8.2 ± 3.7%, 60.0 ± 9.4%, 86.0 ± 3.7%, 100% and 100%, respectively. Error bars represent the mean values ± standard deviation of samples in AFM images (N = 3). e Ensemble fluorescence experiments for transformation of R-DODA and its M1 and M3 variants, after addition of five triggers. f The apparent rate constant k obtained from data in e (0.071 ± 0.002 min−1, 0.117 ± 0.011 min−1 and 0.121 ± 0.004 min−1 for R-DODA, R_M1 and R_M3, respectively. Error bars represent the mean values ± standard deviation of the three experiments at 30 °C. g, j Single-molecule fluorescence measurement on the transformation of R-DODA, R_M1, and R_M3 after addition of two triggers. g Accumulative fluorescence signals from single-molecule fluorescence measurement showing the overall transformation kinetics. h The apparent rate constant k obtained from data in g (0.004 ± 0.001 min−1, 0.098 ± 0.021 min−1 and 0.055 ± 0.004 min−1 for R_DODA, R_M1 and R_M3, respectively. Error bars represent the mean values ± standard deviation of the three experiments at 30 °C. i Histograms showing percentages of transformed DODAs with two triggers at different time points via single-molecule fluorescence measurement. J Representative single-molecule fluorescence traces corresponding to the transformation of individual R-DODA, R_M1, and R_M3. The black line represented the background signals. G, N, and R represent G-, N-, and R-DODAs, respectively. Source data are provided as a Source Data file.

To examine how mismatches affect assembly and transformation of DNA origami arrays, we designed DODA variants G_M1 and G_M2 based on G-DODA, R_M1 and R_M3 for R-DODA (Supplementary Fig. 23). After assembly of DODAs with and without mismatches, the percentages of conformation II were obtained by analyzing AFM images (Fig. 4c, d and Supplementary Figs. 24–35). The fraction of conformation II structures increased with the number of added trigger DNA strands, being in good agreement with previous results. Interestingly, the mismatches showed different thermodynamic effects on the G- and R-DODA. For the G-DODA, a higher fraction of transformed structures was obtained in the presence of the mismatch G_M1, while the implementation of the mismatch G_M2 resulted in a lower yield. In the presence of either R_M1 or R_M3, an increased yield of transformed structures was obtained for the R structure. Although introducing mismatches results in an increase of the energy of the conformations I and II, the extent of increase for both conformations is different for the two structures. This leads to the uncertainty of the free energy differences between I and II, and this difference may vary depending on each specific mismatch. Although quantitative calculation of mismatch effect on the thermodynamics of junctions is lacking, our method presents an experimental strategy to verify the mismatch effect on the thermodynamics of DNA origami arrays.

Next, the mismatch effect on the transition kinetics of DNA origami arrays was investigated. The R origami array, as well as its mismatched structures R_M1 and R_M3 were measured with transformation kinetics using single-molecule fluorescence assay and ensemble fluorescence method. In the ensemble fluorescence assay with five triggers (Fig. 4e, f), both mismatched structures R_M1 and R_M2 showed increased kinetics compared with R structure and had similar apparent rate constants. We further reduced the trigger number from five to two to differentiate the kinetics of R_M1 and R_M3 (Fig. 4g, h). The reduced trigger number slowed down the overall kinetics of three structures. Noticeably, R_M1 and R_M2 presented significant kinetic differences. This phenomenon was further verified using the single-molecule fluorescence assay (Fig. 4i, j). We additionally studied the kinetics of G structure and its mismatched structures G_M1 and G_M2, and found that the two mismatched structures also had higher apparent rate constants than G structure (Supplementary Figs. 36 and 37). We reason that the increased transition kinetics in mismatched structures is due to the increased free energy of conformation I, which reduces the activated energy for the transformation.

Besides mismatching, there are other options to change the junction design in a (quasi-) predictable manner. For example, we engineered a junction design that includes two unpaired free bases by inserting an A on the top scaffold strand of the junction and a base T on the bottom scaffold strand, as illustrated in Supplementary Fig. 38a. Because the base-stacking at junction would be disrupted in conformation I but remain intact in conformation II, we expect this design would greatly favor the latter. Experimental results substantiated this hypothesis, as the DODA assembled into conformation II even without any trigger (Supplementary Figs. 38b and 28d). This example of incorporating free bases to tune the DODA assembly and transformation showed that there is a wider design space to be explored.

Discussion

We developed methods to study the effects of junction sequences on thermodynamics and transition kinetics of a reconfigurable DNA nanoarray. This model translates the thermodynamics and transition kinetics of individual junctions into the collective behaviors of a DNA origami array composed of the same junction sequence. The origami array amplifies the thermodynamic and kinetic differences between junctions with varying sequences, enabling the ensemble kinetic characterization of these differences for the first time. Experimental results demonstrated that the collective behaviors of DNA origami arrays are consistent with the energy model for single junctions.

This approach not only enhances the understanding of how junction sequences influence assembled DNA nanostructures but also offers new methods to tune the transformation kinetics of the DNA origami array. This serves as a complementary approach to previously reported methods, such as altering external factors (e.g., temperature or formamide) or structural design. We demonstrated two strategies to adjust the global transformation kinetics of the origami array: modifying the junction sequences in every junction within the array and adjusting the environmental magnesium concentration. Additionally, it is possible to program local transformation kinetics by engineering heterogeneous junction sequences in specific regions of the array.

The sequence-dependent transformation of DNA origami in this work can shed light on other DNA nanostructures or DNA nanomachines. Many dynamic DNA nanostructures contain soft joints or reconfigurable modules made of HJs. The thermal stability or transition kinetics of the dynamic parts in the DNA nanostructures can be influenced by the junction sequences. This work inspires the future design of dynamic DNA nanostructures for improved stability or transition rates by sequence design, in conjunction with the traditional structural design.

This approach also provides a model for investigating the thermodynamics and transition kinetics of junctions influenced by various factors. The origami array reflects the properties of individual junctions and offers a straightforward way to reveal subtle changes in thermodynamics and kinetics due to sequence effects. Although this work focuses on the effect of the junction core sequence, the model is applicable for studying other factors affecting junctions. Structurally, sequences near the junction core or even distant junction arm sequences can be investigated using this model. It can also be used to explore mechanical constraints, sequence-dependent electrostatic potentials, nicks, or other structural effects. Environmentally, besides magnesium concentration, other buffer conditions or chemical reagents may affect the junction’s preferences. In general, this model can be utilized to study a wide range of structural and environmental effects on junctions. A comprehensive understanding of junction preferences and their impact on assembled structures can ultimately advance the field of DNA nanotechnology.

Methods

Materials

Chemically synthesized DNA short strands and genes were purchased from IDT and were used without further purification. All other reagents were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich or New England Biolabs.

DNA sequences

All DNA sequences (custom DNA scaffold and short DNA oligos) are included in the Supplementary Data 1.

DNA origami design and folding

The DNA origami was designed with the software CaDNAno (http://cadnano.org/). For DNA Origami folding, 10 nM scaffold together with a tenfold excess of each staple strand was mixed in 1×TE (10 mM Tris, 1 mM EDTA; pH 8.0) buffer with 6 mM MgCl2. In the annealing process, the folding mixture was heated at 80 °C and slowly cooled down to 25 °C at the rate of −1 °C/3 min. Afterwards, the folded DNA origami was purified from excess staple strands by agarose gel electrophoresis.

Agarose gel electrophoresis

DNA origami samples were subjected to agarose gel electrophoresis at 70 V for 2–3 h in an ice water bath. Gels were prepared with 0.5 ×TBE buffer containing 10 mM MgCl2 and 0.005% (v/v) Ethidium Bromide. To purify the sample, the gel was illuminated under UV light. The target band was cut, and the sample was extracted by squeezing.

AFM imaging

Two microliter samples were deposited onto freshly cleaved mica. The sample area was filled with 80 µL 1×TE buffer with 10 mM MgCl2. The samples were imaged on a Multimode VIII system (Bruker) in liquid mode using commercial tips (SNL-10, Bruker). The results were analyzed by the Nanoscope analysis (Bruker) and Image J.

Production of custom DNA scaffold

The method uses a pScaf vector, which is commercially available on http://www.addgene.org/111401/. To produce custom DNA scaffold, a pseudogene with prescribed sequence should be designed first. The pseudogene contains the sequence with prescribed sequence and two restriction enzyme-recognition overhangs on both ends. The pScaf vector and pseudogene were first digested by KpnI and BamHI enzymes and purified by agarose gel electrophoresis. Then pScaf vector and pseudogene were mixed with 1:5 ratio and linked by T4 DNA ligase with overnight reaction. The mixtures were transformed into competent DH5α cells. The cells were grown in a LB plate containing 100 µg/ml carbenicillin in 37 °C overnight. Three colonies were selected to collect the plasmids by miniprep. The plasmids were then digested by KpnI and BamHI and verified on agarose gel electrophoresis. Correct insertion of pseudogene into pScaf would show correct bands in the gel. The recombinant pScaf plasmid and helper plasmid pSB4423 were co-transformed into competent XL1-blue cells and incubated on a LB plate containing 100 µg/ml carbenicillin and 20 µg/ml chloramphenicol in 30 °C for 2 days. One colony was selected to continue the growth in 2×YT medium for 24 h, and the custom DNA scaffold was collected following the standard protocol for extracting ssDNA from M13 cells.

Ensemble fluorescence measurements

For ensemble transformation kinetics measurements, DNA origami samples were assembled by mixing 20 nM DNA scaffold, 200 nM DNA staples, 10 nM ATTO647N modified staple, and 20 nM quencher modified staple in 1×TE buffer and 6 mM MgCl2. The mixtures were annealed from 80 °C to 25 °C with the rate of −1 °C/3 min. 200 nM triggers were added to the core structures and their fluorescence measured in a real-time PCR machine (Rotor-Gene Q, Qiagen, USA). Fluorescence measurements were carried out at 30 °C over a time of 50 min, and a data point was taken every 30 s. All measurements were repeated three times. To normalize the fluorescence measurements to the completely transformed sample, the samples with five triggers from one-pot assembly were used as reference for the kinetics normalization.

Sample preparation for single-molecule fluorescence measurements

Sample chambers for single-molecule fluorescence were constructed by affixing SecureSeal™ Hybridization Chambers (2.6 mm depth, Grace Bio-Labs) to 24 mm × 60 mm glass coverslips (170 μm thickness, Carl Roth GmbH). The resulting wells were first cleaned by a 1-h treatment with 1 M KOH, followed by three rinses with 1× PBS buffer. To passivate the surface and prevent non-specific binding, the wells were incubated for 30 min with 0.5 mg/mL BSA-Biotin (Sigma Aldrich) and then washed with 200 μL of 1× PBS. A solution of 0.25 mg/mL neutravidin (Thermo Fisher) was then added for a 10-min incubation to create a binding surface, followed by three washes with 150 μL of 1× PBS.

Biotinylated DNA origami structures were diluted to a final concentration of ~10 pM in 1× TE buffer supplemented with 750 mM NaCl. These structures were then immobilized onto the prepared surface by adding 150 μL of the solution to each well and incubating for 5 min, allowing for biotin-neutravidin binding. Unbound DNA origami was removed by washing the chambers with 150 μL of 1× TE buffer containing 750 mM NaCl. The surface density of the immobilized structures was confirmed using a TIRF microscope to ensure suitability for single-molecule analysis.

For data acquisition, a specialized imaging buffer was prepared to enhance photostability. This buffer consisted of an oxidizing and reducing system (1× TAE, 6 mM MgCl₂, 2 mM Trolox/Troloxquinone) combined with an oxygen scavenging system (12 mM protocatechuic acid, 56 μM protocatechuate 3,4-dioxygenase, 1% glycerol, 1 mM KCl, 2 mM Tris HCl, 20 μM Na₂EDTA). Trigger strands were added to a final concentration of 50 nM each, and the chambers were sealed immediately after the addition of the complete imaging buffer.

Single-molecule wide-field measurements

Single-molecule fluorescence data were acquired using a Nanoimager wide-field/TIRF microscope (Oxford Nanoimaging Ltd.). The system was operated in TIRF mode and equipped with a 532 nm laser (1000 mW) for green excitation and a 638 nm laser (1100 mW) for red excitation. Relative laser intensities were set to 9% and 18% for the green and red channels, respectively. All measurements were conducted with the sample stage maintained at 37 °C.

Two types of dual-color experiments were performed. To analyze transformation kinetics, TIRF movies were recorded over a 20-min period, with data acquisition initiated immediately upon addition of the DNA triggers. During these movies, 100 ms frames were captured every two seconds, alternating between the green and red excitation lasers with a 1-s delay between them. To determine the final transformation yield after this period, static dual-color TIRF images were then collected from several different areas of the same sample.

Multi-step kinetics

Unlike the single-exponential decay observed in dwell time histograms for the switching kinetics of single Holliday junctions1, for the DNA origami arrays, we often obtained nonexponential transformation time distributions that displayed a rising phase followed by a decay in the single-molecule experiments. Analogously, the ensemble measurements showed an initial phase of increasing transformation rates. Such a behavior cannot be described by kinetic laws of single step processes but is characteristic for the convolution of the kinetics of multiple steps. As such, the array transformation most probably consists of multiple consecutive steps, an assumption which is in good agreement with previous studies. They describe the DNA origami transformation as a multi-step process. In each of these steps, different Holliday junctions in the arrays switch their conformation, ultimately resulting in the transformation of the whole structure.

Extracting apparent transformation rate constants from the ensemble measurements

To compare the kinetics of the transformation of the different structures, we defined an apparent transformation rate constant k. For determining k, the normalized fluorescence transients were first calculated as described above. These transients describe the change in concentration of the transformed structures over time. By subtracting the normalized fluorescence values from one, the change in concentration of the untransformed structures was depicted. Similar to single-step first order kinetics, the apparent transformation rate constant k was then extracted as the negative slope of linear fits to the logarithmic representation of the plots. For the linear fit, only data points recorded between 2 min and 15 min were considered to exclude both the initial phase of increasing transformation rates and the endpoint of the transformation reaction.

Extracting transformation yields and apparent transformation rate constants from the single-molecule TIRF measurements

To quantify the percentage of transformed structures from single-molecule TIRF measurements, we divided the number of green (ATTO 542) and red (ATTO647N) co-localized spots by the total number of green spots of dual-color TIRF fluorescence images. To account for a labeling efficiency <100%, the percentage of co-localized spots was normalized by the percentage of co-localized spots of a DNA origami array folded with all five fuel DNA strands to calculate transformation yields. For calculating apparent transformation rate constants, the recorded TIRF movies were drift-corrected and dual-color background-corrected fluorescence intensity transients extracted from the spots. These transients were fitted using a Hidden Markov model, and the transformation times extracted from the fits as the time a sudden increase in fluorescence intensity occurred, and the intensity afterwards remained at a higher level for at least 10 s for the first time. To extract the evolution of the transformation yield over time, these transformation times were cumulatively added up and divided by the total number of transformation times collected. To account for possible transformation yields <100%, the resulting normalized values were multiplied with the final transformation yields extracted from TIRF images recorded directly after movie acquisition. If not stated otherwise, apparent rate constants were then extracted as described for the ensemble measurements, and data points recorded between 20 s and 150 s were considered for the linear fit.

Data availability

The experimental data generated in this study have been deposited in the Zenodo database under accession code https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.15686521. Source data are provided with this paper.

References

Fu, T. J. & Seeman, N. C. DNA double-crossover molecules. Biochemistry 32, 3211–3220 (1993).

Li, X., Yang, X., Qi, J. & Seeman, N. C. Antiparallel DNA double crossover molecules as components for nanoconstruction. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 118, 6131–6140 (1996).

Yin, P. et al. Programming DNA tube circumferences. Science 321, 824–826 (2008).

Wei, B., Dai, M. & Yin, P. Complex shapes self-assembled from single-stranded DNA tiles. Nature 485, 623–626 (2012).

Ke, Y., Ong Luvena, L., Shih William, M. & Yin, P. Three-dimensional structures self-assembled from DNA bricks. Science 338, 1177–1183 (2012).

Ong, L. L. et al. Programmable self-assembly of three-dimensional nanostructures from 10,000 unique components. Nature 552, 72–77 (2017).

Rothemund, P. W. K. Folding DNA to create nanoscale shapes and patterns. Nature 440, 297–302 (2006).

Douglas, S. M. et al. Self-assembly of DNA into nanoscale three-dimensional shapes. Nature 459, 414–418 (2009).

Yao, G. et al. Meta-DNA structures. Nat. Chem. 12, 1067–1075 (2020).

Tikhomirov, G., Petersen, P. & Qian, L. Fractal assembly of micrometre-scale DNA origami arrays with arbitrary patterns. Nature 552, 67–71 (2017).

Wagenbauer, K. F., Sigl, C. & Dietz, H. Gigadalton-scale shape-programmable DNA assemblies. Nature 552, 78–83 (2017).

Dietz, H., Douglas, S. M. & Shih, W. M. Folding DNA into twisted and curved nanoscale shapes. Science 325, 725–730 (2009).

Han, D. et al. DNA Origami with complex curvatures in three-dimensional space. Science 332, 342–346 (2011).

Han, D. et al. DNA gridiron nanostructures based on four-arm junctions. Science 339, 1412–1415 (2013).

Thubagere Anupama, J. et al. A cargo-sorting DNA robot. Science 357, eaan6558 (2017).

Douglas Shawn, M., Bachelet, I. & Church George, M. A logic-gated nanorobot for targeted transport of molecular payloads. Science 335, 831–834 (2012).

Gerling, T., Wagenbauer, K. F., Neuner, A. M. & Dietz, H. Dynamic DNA devices and assemblies formed by shape-complementary, non–base pairing 3D components. Science 347, 1446–1452 (2015).

Ke, Y., Meyer, T., Shih, W. M. & Bellot, G. Regulation at a distance of biomolecular interactions using a DNA origami nanoactuator. Nat. Commun. 7, 10935 (2016).

Seeman, N. C. Nucleic acid junctions and lattices. J. Theor. Biol. 99, 237–247 (1982).

Seeman, N. C. The design and engineering of nucleic acid nanoscale assemblies. Curr. Opin. Struct. Biol. 6, 519–526 (1996).

Winfree, E., Liu, F., Wenzler, L. A. & Seeman, N. C. Design and self-assembly of two-dimensional DNA crystals. Nature 394, 539–544 (1998).

Hyeon, C., Lee, J., Yoon, J., Hohng, S. & Thirumalai, D. Hidden complexity in the isomerization dynamics of Holliday junctions. Nat. Chem. 4, 907–914 (2012).

Miick, S. M., Fee, R. S., Millar, D. P. & Chazin, W. J. Crossover isomer bias is the primary sequence-dependent property of immobilized Holliday junctions. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA94, 9080–9084 (1997).

Carlström, G. & Chazin, W. J. Sequence dependence and direct measurement of crossover isomer distribution in model Holliday junctions using NMR spectroscopy. Biochemistry 35, 3534–3544 (1996).

Overmars, F. J. J. & Altona, C. NMR study of the exchange rate between two stacked conformers of a model holliday junction11Edited by I. Tinoco. J. Mol. Biol. 273, 519–524 (1997).

Lilley, D. M. J. & Clegg, R. M. The structure of the four-way junction in DNA. Annu. Rev. Biophys. Biomol. Struct. 22, 299–328 (1993).

Duckett, D. R., Murchie, A. I. & Lilley, D. M. The role of metal ions in the conformation of the four-way DNA junction. EMBO J. 9, 583–590 (1990).

Adendorff, M. R., Tang, G. Q., Millar, D. avidP., Bathe, M. & Bricker, W. illiamP. Computational investigation of the impact of core sequence on immobile DNA four-way junction structure and dynamics. Nucleic Acids Res. 50, 717–730 (2022).

McKinney, S. A., Déclais, A.-C., Lilley, D. M. J. & Ha, T. Structural dynamics of individual Holliday junctions. Nat. Struct. Biol. 10, 93–97 (2003).

Karymov, M., Daniel, D., Sankey, O. F. & Lyubchenko, Y. L. Holliday junction dynamics and branch migration: single-molecule analysis. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA102, 8186–8191 (2005).

Nickels, P. C. et al. Molecular force spectroscopy with a DNA origami–based nanoscopic force clamp. Science 354, 305–307 (2016).

Zettl, T. et al. The structural ensemble of a Holliday junction determined by X-ray scattering interference. Nucleic Acids Res. 48, 8090–8098 (2020).

Song, J. et al. Reconfiguration of DNA molecular arrays driven by information relay. Science 357, eaan3377 (2017).

Simmons, C. R. et al. The influence of Holliday junction sequence and dynamics on DNA crystal self-assembly. Nat. Commun. 13, 3112 (2022).

Gambietz, S., Stenke, L. J. & Saccà, B. Sequence-dependent folding of monolayered DNA origami domains. Nanoscale 15, 13120–13132 (2023).

Wang, D. et al. Programming the curvatures in reconfigurable DNA domino origami by using asymmetric units. Nano Lett. 20, 8236–8241 (2020).

Fan, S. et al. Proximity-induced pattern operations in reconfigurable DNA origami domino array. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 142, 14566–14573 (2020).

Nafisi, P. M., Aksel, T. & Douglas, S. M. Construction of a novel phagemid to produce custom DNA origami scaffolds. Synth. Biol. 3, ysy015 (2018).

Engelhardt, F. A. S. et al. Custom-size, functional, and durable DNA origami with design-specific scaffolds. ACS Nano 13, 5015–5027 (2019).

Marchi, A. N., Saaem, I., Vogen, B. N., Brown, S. & LaBean, T. H. Toward larger DNA origami. Nano Lett. 14, 5740–5747 (2014).

Friedman, R. A. & Honig, B. A free energy analysis of nucleic acid base stacking in aqueous solution. Biophys. J. 69, 1528–1535 (1995).

Douglas, S. M. et al. Rapid prototyping of 3D DNA-origami shapes with caDNAno. Nucleic Acids Res. 37, 5001–5006 (2009).

Cole, F. et al. Controlled mechanochemical coupling of anti-junctions in DNA origami arrays. Nat. Commun. 15, 7894 (2024).

Acknowledgements

The authors thank Petr Sulc, Dominik Schiwietz, and Michael Matthies for insightful discussion and their effort on using simulation to understand the conformation changes of DNA junctions. This work is supported by Department of Energy grant DE-SC0020996, the National Science Foundation grants CCF-2227399 and ECCS-2328217 to Y.K. The AFM images of DNA origami were collected on an atomic force microscope supported by Grants GM084070 and 3R01GM084070-07S1. D.W. acknowledges the support by the start-up funding from the University of Science and Technology of China, the Leading Talents of Innovation and Entrepreneurship of Gusu District (ZXL2023197), and the National Science Foundation of Jiangsu Province (BK20241817). P.T. gratefully acknowledges financial support from the Federal Ministry of Education and Research (BMBF) and the Free State of Bavaria under the Excellence Strategy of the Federal Government and the Länder through the ONE MUNICH Project (Munich Multiscale Biofabrication) and the BMBF in the framework of the Cluster4Future program (Cluster for Nucleic Acid Therapeutics Munich, CNATM) (Project ID: 03ZU1201AA).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

D.W., F.C., M.P., P.T., and Y.K. conceived and developed the concept. D.W. prepared DNA scaffolds. D.W., F.C., and M.P. prepared DNA origamis samples, performed experiments, and analyzed the data. M.C. and T.S. performed FRET experiments and analyzed data. Y.K. and P.T. supervised the project and analyzed the data. All authors have written, read, and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Peer review

Peer review information

Nature Communications thanks the anonymous reviewer(s) for their contribution to the peer review of this work. A peer review file is available.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Source data

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Wang, D., Cole, F., Pfeiffer, M. et al. Modulating transformation of DNA origami nanoarray via sequence design. Nat Commun 16, 5626 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-025-61421-w

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-025-61421-w

This article is cited by

-

DNA Nanostructures-based Delivery of RNA Drugs for Cancer Therapy

Chemical Research in Chinese Universities (2025)