Abstract

Optical memristors represent a monumental leap in the fusion of photonics and electronics for neuromorphic computing and artificial intelligence. Here, we reveal the first lead zirconate titanate (PZT) optical memristor, working with a paradigm of functional duality: non-volatile setting and ultrafast volatile modulation via the Pockels effect. Fine-tuning and large modulation depth are achieved with an index change of 4.6 × 10−3 when setting above a threshold voltage Vth and the switching energy is 12.3 pJ only. The non-volatility is highly stable even with >100,000 cycles. Sub-nanosecond volatile modulation (48 Gbps, 432 fJ/bit) is realized with high efficiency (VπL ~ 0.5 V·cm) via the strong Pockels effect below Vth. Our wafer-scale manufacturing process shows great potential for mass production. The present PZT optical memristors bridge the gap between high-speed photonics and non-volatile memory, offering transformative potential for high-speed and energy-efficient optical interconnects, quantum computing, neural networks, in-memory computing, and brain-like architecture.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Memristors, with the ability to modulate signals actively and hold memory states akin to synaptic activity in the mammalian brain, have opened new avenues to non-volatile memory and neuromorphic computing, significantly improving energy efficiency and integration density while bypassing the von Neumann bottleneck1. Inspired by the remarkable capabilities and technological promise of electronic memristors, the photonics community has been striving to develop an optical counterpart called optical memristors, which are capable of modulating the light amplitude/phase and holding the state non-volatilely2. Optical memristors represent a monumental leap in the fusion of photonics and electronics, heralding a new era of high-speed, energy-efficient information processing that promises to transcend the constraints of traditional architectures. Significant efforts have been made towards developing optical memristors to create new paradigms in photonic integrated circuits (PICs), and catalyze the emergence of new applications, including high-efficiency in-memory computing3,4,5,6, brain-inspired architectures7, and post-fabrication trimming of PICs for calibrating the operation of sophisticated programmable optical processors with fabrication-sensitive structures.

Among them, phase-change materials (PCMs)8,9,10,11,12,13,14,15,16 have received substantial attention owing to compact footprint, multi-level storage, and large modulation depth, while the difficulty in the inherent control mechanism for the amorphous/crystalline phase change might hinder the wide application in large-scale integration2. Microelectromechanical systems (MEMS)17,18, magneto-optics19, and charge-based20,21 optical memristors are interesting but still suffer from the fabrication complexity or inability for multi-level tuning, and few experimental demonstrations have been reported so far2. The ferroelectric material is another option that allows optical information storage by switching non-volatile ferroelectric domains with an external electric field22,23,24. Common ferroelectric materials include lithium niobate (LN), lithium tantalate (LT), BaTiO3 (BTO), and PZT. Among them, LN and LT have been studied extensively as conventional ferroelectric materials, but there have not been non-volatile optical memory behaviors reported yet. Alternatively, BTO allows the storage of optical information by switching non-volatile ferroelectric domains23, while a continuous direct current (DC) voltage is needed to maintain the non-volatile state. Meanwhile, the heterogeneous integration of thin-film BTO required a few complicated processes, including molecular beam epitaxy, direct wafer bonding, and wafer grinding, which leave space for further refinement. On the other hand, when programming energy and time are considered, current technologies typically show lower power efficiency and slower speeds compared to their digital counterparts25. While previous research has explored the use of volatile responses of integrated PN junction and PCM to enhance tunability26, this method encounters obstacles such as a limited operation bandwidth of 7.1 GHz, intricate fabrication processes involving multi-layer sputtering, and restricted volatile modulation efficiency to levels below 5 pm/V. Therefore, more efforts are expected to explore a brand-new routine for optical memristors in terms of optical performance, switching speed, energy, fabrication process, and the capability for scaling to system-level integration.

PZT has been reported to exhibit spatially photo-induced non-volatile response under applied bias through carrier generation27, pyroelectric or optoelectronic effects28. For the photonics community, significant attention is given to its strong electro-optic (Pockels) effect, which facilitates ultra-fast modulation29,30. However, the feasibility of achieving both electrically-controlled optical memristor and high-speed modulation on a single device remains an open question.

Here we demonstrate optical memristors based on thin-film PZT, which precisely control the refractive index directly by electrically manipulating the ferroelectric domain, with no bias voltage required. Specifically, our PZT optical memristors have a unique functional duality related to a threshold voltage Vth: (i) Non-volatile setting with stable domain reconfiguration occurs above Vth, while (ii) ultrafast volatile modulation via the Pockels effect dominates below Vth, achieving sub-nanosecond switching speeds– a capability unattainable in existing ferroelectric photonic devices. The PZT optical memristor exhibits superior performance metrics over prior non-volatile devices: low loss of ~1.9 dB /cm, precise fine-tuning, large modulation depth with an index-change as large as 4.6 × 10−3, high stability over the period of more than three weeks, great endurance of over 100,000 cycles with pJ-level non-volatile switching energy and zero maintaining power. For volatile operation, the device achieves 48 Gbps high-speed signal processing with an energy efficiency of 432 fJ/bit and a modulation efficiency of 42 pm/V. The wafer-scale sol-gel fabrication process has the potential for Complementary Metal-Oxide-Semiconductor (CMOS) compatibility and scalability, making it ideal for on-chip photonic integration in the wafer-scale. This advancement enables the realization of essential elements with versatile functionality, such as microring resonators (MRRs), Mach-Zehnder interferometers (MZIs), and Fabry-Pérot (FP) cavities, showing great potential for advancing large-scale photonic systems31. Furthermore, we demonstrate the scalability of PZT optical memristors for developing PICs with a memristive optical switch matrix and adaptive memristive optical cavities for spectral manipulation. This work demonstrated the optical memristor capable of performing high-speed signal processing and non-volatile retention on a single platform and presented the inaugural demonstration of scalable functional systems with electrical-controlled optical memristors. Our finding underscores the great promise for wide applications in high-speed and energy-efficient optical interconnects32, programmable PICs33, quantum computing34,35, neural networks4,36, in-memory computing6, and brain-like computing37.

Results

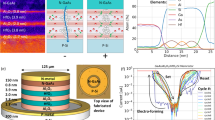

The fabrication of thin-film PZT wafers and optical waveguides was carried out with the sol-gel process38,39, as illustrated in Fig. 1a–g. Highly (100)-oriented PZT films in our recently published work were developed successfully at low annealing temperatures (450 °C), demonstrating the great potential for CMOS- compatibility39 (see more details in Methods and Supplementary Section 1). The 4-inch PZT wafer was realized with a top-surface roughness of 0.7 nm and a thickness non-uniformity of less than 15 nm. All the following processes, including the lithography, dry etching, and by-product cleaning processes, were optimized for achieving PZT optical waveguides with smooth sidewalls/top-surfaces, enabling high-quality building blocks and multi-functional photonic integrated circuits (PICs), as depicted in (Fig. 1e–g). The simulated field distribution for the TE0 mode of the PZT optical waveguide is shown in Fig. 1h, where the optical field is tightly confined in the PZT ridge with a high confinement factor of over 85% due to the high refractive-index contrast, which facilitates strong electro-optic interaction in PZT. As a ferroelectric material, PZT possesses a perovskite crystal structure. Initially, the crystal is in a paraelectric phase, with positive and negative charge centers aligned at the body center. When an external electric field is applied, the Zr and Ti4+ ions shift towards one of the eight vertices, causing a displacement of the positive and negative charge centers (Fig. 1i). This is achieved, for example, by applying a voltage to the electrodes on both sides of the waveguide (Fig. 1j).

a Wafer-scale sol-gel fabrication processes of PZT Optical Memristors. b Photograph of the spin-coating wafer. c Scanning electron microscopy (SEM) picture of the top view of the thin-film PZT (thickness~ 300 nm). d AFM image of the thin-film PZT. e Photograph of a 4-inch wafer patterned by using an ultraviolet stepper lithography system. f Colorized SEM of PZT MRR (blue). g SEM picture of the cross-section of a PZT ridge waveguide. h Simulated field distribution for the TE0 mode. i PZT unit cell representation before and after poling. j Schematic diagram of the ridge waveguide cross-section and the poling process. k The dependence of the refractive index changes ∆neff (Pν) against the net ferroelectric domain polarization, and the corresponding simplified top-view schematic of ferroelectric domains in PZT.

The core mechanism of this study is the electric-field-driven control of ferroelectric domains in PZT, which exhibit a unique functional duality. This manipulation hinges critically on the magnitude of the applied electric field relative to the activation field, defined as the minimum field strength necessary to induce domain motion and polarization reversal in PZT40,41,42 (Supplementary Sections 2, 3). In this work, for the convenience of expression, we define the minimum voltage required to induce domain reversal as the threshold voltage (Vth).

If the applied voltage is larger than the Vth, the polarization reversal occurs and, once the external field is removed, the ferroelectric domain inside the thin-film PZT maintains a certain degree of polarization, known as remanent polarization43. The refractive index neff(Pν) of thin-film PZT is related to the remnant polarization in PZT44, i.e.,

where neff0 is the refraction index of thin-film PZT with random polarization, n1 is the relative refractive index, Pν is the net ferroelectric domain polarization, and P0 is the ferroelectric domain polarization on the boundary of the thin film. According to Eq. (1), variations in |Pν| lead to changes in the non-volatile refractive index neff (Pν), as described in Fig. 1k. Here, we define the saturated polarization state as “State 1” and the random polarization state as “State 0”. “State 1” and “State 0” correspond to the minimum and maximum refractive indices, respectively. For the non-volatile operation, changing the domain to any mixed-polarization state between “State 1” and “State 0” can be accomplished by applying the setting voltage Vset, so that the refractive index neff(Pν) can be varied. Similarly, applying a poling voltage Vpol can erase the net ferroelectric domain polarization in PZT to its “State 1”.

However, if the applied voltage is below the Vth, the ferroelectric film will be in a metastable state. In this state, the polarization reversal process of the ferroelectric domain will become very slow or even almost non-existent. The domain walls revert to their initial positions upon field removal, resulting in linear Pν − E curves with negligible remanent polarization (Supplementary Section 2)45,46. To differentiate, we refer to the time-varying voltage with an amplitude less than Vth as the driving voltage Vdr. This different electric-field-driven control allows us to choose non-volatile or volatile working procedures.

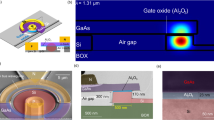

To further verify this concept, we employed an MRR for realizing multi-level non-volatile operation and high-speed volatile operation (Fig. 2a). The initial poling was performed by applying a train of 10 voltage pulses at a frequency of 1 kHz with a 50% duty cycle and an amplitude of 150 V. Subsequently, transmission at the through port of the MRR was measured after applying 2-minute Vset pulses (8–26 V) at the same frequency and duty cycle. Figure 2b shows a single-cycle demonstration of one distinct non-volatile state. As clearly shown in Fig. 2c, adjusting the setting voltage Vset results in multi-level non-volatile resonance-wavelength detuning without DC bias.

a Optical microscopy image of an MRR with a bending radius of 60 μm. b Single-cycle demonstration of one distinct non-volatile state. c Measured transmissions at the through port of the MRR-based PZT optical memristor with different setting voltages Vset. d Measured resonance-wavelength detuning of the MRR-based PZT optical memristor set with different setting voltages Vset as the driving voltage Vdr varies. e Eye diagrams for NRZ modulation at the data rate of 48 Gbps with a driving voltage Vdr of 3 V.

We also observe that increasing Vset leads to higher Q-factors and reduced transmission loss, which may be attributed to the gradual dissipation of surface charges that remain after poling47. To mitigate these effects, a post-poling conditioning step of −1 V for 1 minute could be applied. The non-volatile switching energy is calculated as 12.3pJ for the minimum setting voltage ~ 8 V. When higher non-volatile detuning is required, both the Vset and the corresponding power consumption increase. For example, the required energy rises to 130 pJ when Vset is 26 V. (Supplementary Section 4).

Notably, the Vth was observed to be 8 V in this instance with 4 μm electrode spacing. When voltages below the Vth were applied and subsequently withdrawn, no resonance shifting occurred (Supplementary Section 2). Only volatile modulation of the refractive index via the Pockels effect in PZT. It is important to note that the Pockels effect is also related to the domain polarization inside the waveguide23. The EO modulation efficiency of the PZT waveguides and its dependence on Vset were first characterized by measuring the resonance detuning of the fabricated MRR set at Vset = 0, 10, 15, and 20 V. Here, Vdr was varied from −8 V to 8 V, staying below the threshold, as shown in Fig. 2d. When Vdr was negative (i.e., opposite to the poling direction), the measured modulation efficiency was about 42, 25, 12, and 6 pm/V with Vset = 0, 10, 15, and 20 V, respectively. When Vdr was positive, the modulation efficiency became 26, 33, 20, and 23 pm/V, respectively. Such asymmetry of the Vset-dependence for the modulation efficiency is attributed to the ferroelectric domain and Pockels effect interactions in PZT, as expected by our theoretical prediction in the Supplementary Section 3. Then, high-speed EO modulation for NRZ signals was demonstrated by using the setup described in the method. As given in Fig. 2e, the recorded NRZ eye-diagram with a driving voltage Vdr of 3 V at 48 Gbps, the corresponding electrical energy consumption is estimated to be ~432 fJ/bit for the 48 Gbps data transmission.

Further measurements confirmed that the fabricated PZT waveguide had a low propagation loss of ~1.9 dB/cm and a low temperature sensitivity of ~30 pm/°C (Supplementary Sections 5, 6). Additionally, we also investigated the DC drift of the thin-film PZT waveguides (Supplementary Section 7), finding high stability with a negligible phase drift of less than 0.05π. The ability to address the issue of DC drifting, which often challenges other EO modulators or switches fabricated on, e.g., thin-film lithium niobate48, is very promising for various applications with optical switching and modulation. In the following sections, we will present several representative building blocks for various applications

Building blocks

MZI-based PZT optical memristors

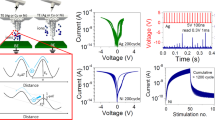

MZIs are crucial fundamental components for photonic systems on a chip, encompassing the versatile functionality of e.g., optical modulation, optical switching, variable optical attenuation, optical filtering, variable optical splitting for optical interconnects and optical computing49,50. For example, large-scale photonic switches are typically assembled from 2 × 2 MZI switches interconnected into networks or arrays of various topologies, including cross-bar, Benes, and path-independent loss (PI-Loss), along with their numerous variants36,49,51. However, developing large-scale PICs presents significant challenges, particularly in calibrating a large number of MZI elements due to random phase errors in their initial states, which often require complex processes and additional power consumption. In this section, we demonstrate MZI-based PZT optical memristors for optical switching, Fig. 3a, b, highlighting their potential to simplify the calibration and non-volatile reconfigurability as well as volatile high-speed optical signal processing.

a Schematic of the MZI -based 2 × 2 PZT optical memristors, consisting of two imbalanced arms with 1-mm-long phase shifters and two 2 × 2 multimode interferometers with a splitting ratio of 50%: 50%; the purple arrow represents the direction of the poling electric field; the blue arrow represents the direction of the applied drive voltage Vdr. b Optical microscopy image of the fabricated 2 × 2 MZI optical memristors. c Non-volatile tuning of the wavelength notch with the setting voltage Vset varying from 8 V to 32 V. Before the setting voltage is applied to set any state, this optical memristor was re-initialized by applying a high poling voltage Vpol of 80 V. d Real-time optical modulation measurements. Normalized output intensity from the through port when the device operates with a drive voltage Vdr of 4 Vpp at the frequency of 10 MHz. The upper one represents the input electrical signals, and the bottom one represents the switched optical signals. e Measured transmissions at the cross port when operating with Vdr = 0 and 5.0 V, respectively.

The present MZI-based PZT optical memristor consists of two imbalanced arms and two 2 × 2 multimode interferometers with a splitting ratio of 50%: 50%. Electrodes used for applying a lateral electric field were placed on both sides of these two arm waveguides, forming the phase shifters with the length of, e.g., ~1.0 mm. Initially, the poling process is implemented by applying ten short electrical pulses at the frequency of 1 kHz in the direction shown in Fig. 3a. Figure 3c shows the measured non-volatile tuning of the notch wavelength as Vset increases from 10 V to 32 V.

To further demonstrate the functional duality of thin-film PZT, the MZI operated in a push-pull configuration for high-speed optical signal processing with a driving voltage Vdr lower than Vth. The voltage directions of Vpol and Vdr shown in Fig. 3a reflect this push–pull configuration, in which opposite driving electric fields are applied to the two interferometer arms. Figure 3d shows the measurement results when 4 Vpp (Voltage peak-peak) was applied with 10 MHz frequency (Methods), indicating that the device is switchable on nano-second scale. Figure 3e presents the measured transmissions at the cross port of the MZI with 1-mm-long phase shifters when operating with Vdr = 0 and 5.0 V, respectively, showing that a phase-shifting of π was achieved, and correspondingly, the modulation efficiency VπL is about 0.5 V∙cm. The estimated Pockels coefficient of the post-poling PZT is as high as 120 pm/V, which is over four times higher than that of lithium niobate52. Moreover, extending the electrode length (e.g., to 5 mm) could greatly reduce the voltage Vπ to be less than 1 V, so that it is potentially possible to develop the PZT modulators operating at CMOS-compatible driving voltages.

FP-cavity-based PZT optical memristors

Optical cavities have been recognized as another key element for realizing various functionalities (including optical filtering, modulation, or switching) due to the great advantages in structure flexibility, footprint compactness, and energy efficiency53,54,55. Unfortunately, the resonance wavelengths are often susceptible to the fabrication variations and thus, one often needs to thermally or electrically tune the resonance wavelength for alignment with additional high-power consumption56.

In this section, we propose a 1 × 2-FP-cavity-based PZT optical memristor, as shown in Fig. 4a, b (more design details in Supplementary Section 8). Note that the present device has a short cavity length, enabling a free spectral range (FSR) as large as 8 nm, which is much larger than regular MRRs on the same chip, helping to clearly observe the multi-level non-volatility revealed here. A fine-grained non-volatile tuning was achieved by systematically varying the setting voltage Vset from 10 V to 36 V with an increment of 0.4 V, each inducing a measurable resonance wavelength shift (Δλres) in the FP-cavity-based memristor, as shown in Fig. 4c, d. A fine-tuning was observed across a spectral range of 3.0 nm, corresponding to a non-volatile refractive index change of approximately 4.6 × 10−3 (Supplementary Section 9). The observed nonlinear tuning behavior, including plateaus and abrupt jumps, is likely attributed to material imperfections and fluctuations in the applied DC signals. To improve the step resolution and enable a greater number of distinguishable states, thereby advancing toward quasi-continuous non-volatile tuning, future efforts should focus on stabilizing the driving electric field and improving the Q-factor of the FP cavity.

a Schematic configuration. MWGs, multimode waveguide gratings, Modemux, mode multiplexers. b Optical microscopy image of the fabricated device. c Measured transmission spectral responses at the through port with different setting voltages Vset. d Extracted resonance wavelength shifts (detuning with 1559.2 nm) versus different setting voltages Vset. e Five distinct non-volatile states correspond to the setting voltages Vset of 30, 21, 23, 25, and 36 V. For each non-volatile state, there are 20 cycles measured for the resonance-wavelength detuning. f Time domain measurements after 10 and 10000 cycles, showing that the optical memristor operates well without any degradation. s. Real-time optical modulation measurements: g–j Normalized output optical intensity at the through port when operating with rectangular driving-voltage signals (Vdr=4Vpp) at the frequency of 1 Hz (g), 100 kHz (h), and 5 MHz (i). j The rising/falling edge of the switched optical signals. k Measured spectral responses at the through port of the FP cavity when operating with different driving voltages Vdr of −1, 0, and +1 V, respectively.

Figure 4e demonstrates the repeatability of the FP-cavity-based optical memristor by characterizing five target states set with Vset = 30, 21, 23, 25, and 36 V as examples, respectively. For each target state, the following cycle process was repeated 20 times (Supplementary Section 10): (i) setting to the target state; (ii) measuring the resonance wavelength; (iii) erasing to “State 1”. Each target state was cycled 20 times, and the corresponding experimental results have shown excellent consistency and repeatability with a minor wavelength variation of less than ±0.05 nm. Further improvement is expected with more precise voltage and temperature control. More details are shown in the Supplementary Section 11. Furthermore, to highlight the high endurance of our PZT optical memristors, we used an arbitrary function generator programmed to alternate voltage pulse cycles between setting and erasing at a frequency of 5 Hz (see Method). The pulse series were generated with the amplitudes of 1 V for setting and −5 V for erasing, which were then amplified to 30 V and −150 V by using a voltage amplifier, respectively. This setup was maintained throughout the whole experiment, and the experimental result with more than 100,000 cycles was recorded, as shown by the data in Fig. 4f as well as the video in the supplementary material (Supplementary Movie 1). Some baseline drift was observed, primarily due to the unpackaged vertical fiber coupling and the absence of thermal stabilization. Nevertheless, the overall signal contrast and switching functionality remained clearly distinguishable. These issues are expected to be mitigated with improved packaging and active thermal control in future implementations.

The functional duality of the FP-cavity-based PZT memristor was also showcased in experiments. When operating below Vth, this PZT memristor demonstrated its availability for high-speed optical switching/modulation. In particular, temporal responses of the device were measured with different modulation frequencies of 1 Hz, 100 kHz, and 5 MHz, while the driving voltage was chosen as 4 Vpp, as shown in Fig. 4g–j. The optical signal was effectively modulated across different frequencies, showcasing the device’s versatility for high-speed switching with minimal electro-optic relaxation effects, which is a crucial issue for low-frequency or long-timescale applications, like ubiquitous DC bias in modulators57. As shown in Fig. 4i, the switching exhibited a fast rising/falling time of around 2.5 ns, primarily limited by the measurement setup in the lab. Intrinsically, the switching speed can be achieved in sub-nanosecond scale. Figure 4k demonstrates the measured static spectral responses at the through port of this FP cavity when operated with different driving voltages Vdr of −1, 0, and +1 V, respectively. The EO modulation efficiencies for negative and positive biases were different, with the measured values of 26 pm/V and 22 pm/V, respectively, showing the asymmetry similar to the MRR-based PZT optical memristors mentioned above. By judiciously choosing the appropriate ferroelectric domain polarization and bias voltage, the effective Pockels coefficient can be enhanced, which is advantageous for developing high-performance EO modulators as desired for high-speed optical processing systems.

Multifunctional photonic circuits enabled by scalable pzt optical memristors

Previously reported optical memristors were still limited to the implementations of individual elements (such as MZIs and MRRs)12,23, and have not demonstrated their potential scalability for multifunctional photonic systems on a chip with large-scale integration, which is essential for practical applications. Here, we make efforts to demonstrate the scalability and versatility of our PZT optical memristors with the following two representative architectures, including a memristive optical switch matrix and an adaptive memristive multi-channel optical cavities for spectral manipulation.

Memristive optical switch matrix

The memristive optical switch matrix demonstrated here is a 4 × 4 non-blocking optical switch with Benes topology, as shown in Fig. 5a, integrating six 2 × 2 MZI-based PZT optical memristors cascaded in three stages and two waveguide crossings (Supplementary Section 12). Initially, these six 2 × 2 MZIs showed notable random phase errors due to the random variation of the waveguide dimensions, which is a common challenge in developing large-scale PICs58. Figure 5b shows the measured transmissions Tij (i, j = 1, 2, 3, 4) from port Ii to port Oj at the initial state without any calibration, illustrating that light from any one input port was routed to the target and non-target output ports with random power ratios (Supplementary Section 13). In this case, careful calibration is often inevitable for conventional MZIs, which introduces high complexity for the development and also consumes additional power to compensate for the random phase errors58. Fortunately, the initial random phase errors can be compensated conveniently by utilizing the PZT non-volatility to introduce permanent phase-correction for each 2 × 2 MZI. By applying the appropriate setting voltage, we achieved phase shifts ranging from 0 to π, effectively reconfiguring each MZI to the desired ON or OFF state. Several typical routing configurations were demonstrated successfully by applying optimal setting voltages Vset, as summarized in Fig. 5c–e and Table S2 in the Supplemental materials. For example, we configured the routes non-volatilely as follows: (1) Configuration #1 with the routines of I1 → O1, I2 → O2, I3 → O3 and I4 → O4; (2) Configuration #2 with the routines of I1 → O3, I2 → O4, I3 → O1, and I4 → O2; (3) Configuration #3 with the routines of I1 → O2, I2 → O1, I3 → O3, and I4 → O4. All these non-volatile reconfigurations of optical routines were realized with decent extinction ratios higher than 15 dB within the wavelength range of 1530–1600 nm. In particular, for a single MZI, one can achieve non-volatile optical power routing with a low excess loss of less than 0.3 dB and high extinction ratios greater than 30 dB at the center wavelength (Supplementary Section 12). In theory, the performance could be further enhanced with fine phase control. This memristive optical switch matrix was further used to demonstrate high-bit-rate data routing by choosing configuration #3 as an example (Supplementary Section 13), and 40 Gbps non-return-to-zero (NRZ) data were launched into the corresponding input port. Figure 5f shows the measured eye diagrams for the data routing in configuration #3, exhibiting high signal-to-noise ratios and showing great potential for developing a large-scale N × N optical switch matrix with excellent non-volatile reconfiguration and high-speed operation. The ability to compensate the initial random phase errors non-volatilely eliminates the need for continuous power consumption for correction, representing a great advancement for developing programmable photonic chips.

a Optical microscopy image of the 4 × 4 optical switch. b Chart of the measured transmissions from the input ports (I1, I2, I3, and I4) to the output ports (O1, O2, O3, and O4) at the initial state with random phase errors. c–e Chart of the measured transmissions from the input ports (I1, I2, I3, and I4) to the output ports (O1, O2, O3, and O4) when all the 2 × 2 MZI switches are reconfigured with the desired optical routines (as defined by configurations #1, #2 and #3) by applying the appropriate setting voltages. f Measured eye diagrams for the optical signals propagating along the routines (I1-O2, I2-O1, I3-O3, I4-O4) as defined by configuration #3. FP-cavity-based PZT optical memristors in cascade for adaptive memristive spectral manipulation: (g) Schematic configuration; (h) Optical microscopy image of the fabricated device; (i) Measured transmission spectra at the through ports for the initial state without any correction; (j) Measured transmission spectra at the through/cross ports when the resonance wavelength of each FP cavity was aligned carefully to have uniform channel spacing by applying the corresponding setting voltage Vset; (k) Measured transmission spectra at the through/cross ports when channels #1 and #3 are erased and retrospectively set so that their resonance wavelengths are respectively aligned with channels #2 and #4.

Adaptive memristive optical cavities for spectral manipulation

Optical cavities have been extensively developed and widely employed, while the resonance wavelengths have to be tuned for alignment with additional power consumption56. Here, we developed an adaptive approach of non-volatile fine-tuning of the resonance wavelengths of multiple FP cavities in cascade for PZT optical memristors (Fig. 5g, h). Figure 5i gives the measured initial transmission at the through port, showing high non-uniformity of the channel spacing, which seriously hinders the application in systems. When channels #1- #4 were tuned by applying the appropriate setting voltages Vset of 15, 30, 12, and 13 V, the resonance wavelengths were well aligned with a uniform channel spacing of 200 GHz (1.6 nm), as shown in, as shown in Fig. 5j. Note that the Q-factor changes of these FP cavities were negligible, further validating that no additional loss was introduced. To further verify the non-volatile spectral manipulation, the setting states of channels #1 and #3 were erased and set with 8 V and 15 V, in which way their resonance wavelengths were aligned with channels #2 and #4, respectively, as shown in Fig. 5k. Accordingly, the present four-channel FP-cavity-based PZT optical memristors were reconfigured successfully to have a two-channel spectral response with a channel spacing of 400 GHz and enhanced extinction ratios of >25 dB. The chip was also characterized after it was stored at room temperature for three weeks, exhibiting a gentle resonance-wavelength shift of less than 0.01 nm, thus verifying a high long-term stability (Supplementary Section 14), which is crucial for practical applications. The demonstrated non-volatility addresses the key issues for optical cavities used for applications like wavelength-selective switches (WSSs), which are crucial components in flexible optical networks59. In addition, the present structure could also work as a modulator array available to work together with an optical frequency comb or multi-wavelength lasers for ultra-high capacity optical interconnects56 or optical computing60,61 with multiple wavelength channels.

Vision of potential applications of PZT optical memristors

Our vision of potential applications of the developed PZT optical memristors is illustrated in Fig. 6, which highlights the diverse application prospects of the thin-film PZT platform for PICs, showcasing great potential in optical interconnects, microwave photonics, optical neural networks, and Lidar, etc.

As shown in Fig. 6, a general architecture of compact optical transmitters/receivers with multiple FP-cavity modulators or filters in cascade is presented, as desired for high-capacity wavelength-division-multiplexed optical interconnects. For this optical transmitter, the volatility of these cascaded FP-cavity modulators supports high-speed EO modulation, while their electrical non-volatility is used for precise trimming to align the central wavelengths as defined. For this receiver, the non-volatility is utilized for achieving accurate wavelength alignment for the multi-channel FP-cavity filter. With this configuration, ultra-compact, high-speed, energy-efficient, and high-data-capacity optical interconnect systems can be realized with an optical frequency comb laser source.

Compared with other non-volatile solutions, the present thin-film PZT platform supports low-loss waveguide propagation as well as high-speed EO modulation, enabling various large-scale reconfigurable PICs. For example, the integration of multiple high-speed EO MZI switches and low-loss waveguide spirals can achieve high-speed tunable optical delay lines and the array, facilitating the realization of high-speed parallel signal processors that can manipulate signals across temporal, wavelength, and spatial dimensions. The chip can be reconfigured conveniently to support a range of advanced functionalities, including accurate microwave reception, narrowband microwave filtering, and wide-bandwidth arbitrary waveform generation for optical computing. The inherent non-volatility of PZT optical waveguides allows for precise trimming of random phase errors in MZI switches, greatly simplifying the control systems and significantly reducing the energy consumption for the PICs when used for handling complex and diverse signal processing tasks.

We also present a general optical neural network (ONN) architecture, which can be implemented efficiently using the present PZT optical memristors equipped with MZIs or MRRs, without any additional complexity of design and presents significant challenges, as depicted in Fig. 6. In this example, this architecture is designed with MZIs, while a mesh of MRRs can also be developed similarly. With this ONN, high-speed training is facilitated through the volatility of the thin-film PZT MZI when the driving voltage Vdr is below the threshold voltage Vth. After the network is trained very well, the non-volatile setting can be achieved by appropriately adjusting one arm of the MZI-based optical memristors, depending on the setting voltage Vset. In contrast, the use of non-volatile PCMs for being reconfigured with optical pulses presents challenges for large-scale PICs, due to the inability to support high-speed training, the complexity of the control systems, and the unavailability of ultra-low energy consumption.

Last but not least, with the high-speed EO modulation capability of the present PZT optical memristors when working below Vth, an optical phased array (OPA) with frequency-modulated continuous-wave (FMCW) technology is achievable for all-solid-state light detection and ranging (LiDAR). When compared with the popular thermo-optically modulated silicon OPAs, the present PZT optical memristors have significant advantages of consuming ultra-low energy, eliminating the thermal crosstalk, and enabling ultra-fast modulation speeds, which is especially crucial within dense OPAs for high-resolution LiDAR systems62. On the other hand, the PZT optical memristors offer high modulation efficiency with low temperature sensitivity as well as low DC drift, which is evidently more advantageous than conventional EO modulation used for OPAs. This is essential for real-time data processing and rapid environmental mapping in autonomous vehicles and other applications requiring precise spatial awareness and object detection.

Discussion

The advantages of electrical control in photonic systems arise from the maturity and reliability of electronic technologies, which enable efficient, scalable, and precise modulation critical for advanced optical applications. As highlighted in Table 1, state-of-the-art electrically controlled optical memristors, each exhibit inherent trade-offs among performance metrics. (Note: Optically controlled memristor systems63,64,65 for optical computing, though progressing significantly, are not included in this discussion.) PCMs are noted for their compact footprint, multi-level storage, and large modulation depth, but face significant challenges in cycling endurance and the complexity of pulse control needed for effective heating. MEMS structures often require large electrostatic combs, complicating their monolithic integration with other functional devices. Furthermore, the programming speed requires further enhancement to meet the demands of computing applications. BTO enables quasi-continuous non-volatile control but necessitates a sustained DC bias, resulting in static power dissipation. Although heterogeneous III–V/Si materials have been incorporated into mature and standard semiconductor processes, the charge-trapping mechanism has to involve multiple fabrication steps, including multi-etching, multi-doping, wafer bonding, and atomic layer deposition. Magneto-optic memristors achieve high endurance and sub-nanosecond switching speeds but exhibit limited modulation depth (~0.15 nm). Additionally, these optical memristors are still developed at the level of individual elements due to the fabrication complexity and propagation losses, which introduce some constraints to the scalability for multifunctional photonic integrated systems, and more efforts are demanded.

In contrast, our PZT optical memristors represent a revolutionary advancement by uniquely combining non-volatile and volatile functionalities within the same waveguide. This platform supports a precise fine-tuning, high cycling endurance, low non-volatile switching energy, and substantial modulation depth. The functional duality enables architectures for photonic computing, where synaptic weights are dynamically reconfigured in volatile mode and stored non-volatilely without static power, directly addressing the von Neumann bottleneck by minimizing data movement. The wafer-scale sol-gel fabrication process, with low-temperature annealing (@ 450 °C), makes promise to CMOS compatibility. The XRD characterization confirms good crystallographic uniformity across the wafer. In addition, multiple devices fabricated in the same block exhibit consistent threshold electrical field (~2 V/μm), indicating good die-level consistency. These experimental results suggest the potential to have high wafer-scale uniformity of the sol–gel–derived PZT thin films. Considering that the CMOS integration of PZT may encounter potential contamination concerns during etching processes, back-end-of-line processing protocols66, could be established to address these risks systematically.

The non-volatile operation of PZT optical memristors currently requires elevated voltages, posing the integration challenge with electronic circuitry at the chip level, while the kHz-non-volatile-switching speed remains suboptimal. Recent advances suggest the pathway for improvement. For example, in ref. 67, optimized the waveform and rise/fall times of pulse poling, resulting in better alignment and higher piezoelectric response compared to bipolar pulse poling, requiring less time. In ref. 32, a high temperature of 90 °C is employed to reduce the poling voltage and shorten the time, enabling the realization of high-performance electro-optic modulators. Notably, nanosecond-level domain switching time was observed in PZT-based ferroelectric capacitor68, which benefits from the narrowed electrode spacing and shrunk electrode area. Inspired by these studies, we aim to optimize the poling pulse profile, elevate the operating temperature, and reduce electrode spacing to lower the Vset and enhance the response speed. These adjustments are expected to address both voltage and speed limitations through practical engineering strategies, without fundamental material modifications. For system-level integration with electronic circuitry, the required high voltage can be achieved by using on-chip charge pump DC-DC converters69 or the approach used for MEMS systems70.

These findings in this work lay the groundwork for future optical neural networks, large-scale matrix operations implementations. Especially, the non-volatile manipulation provided by PZT enables the trimming to compensate for the random phase errors (which always happen), which is very helpful to greatly simplify the system management and thus strongly supports the further realization of large-scale photonic integrated circuits (PICs). Furthermore, the fabrication can be easily implemented on wafer-scale with the regular deep-UV lithography process to support the realization of the PICs for large-scale matrix operation. Note that the current propagation loss ~1.9 dB/cm can be reduced possibly by optimizing the etching process to develop ultra-large-scale PICs on PZT in the future. Looking ahead, we aim to enlarge these devices into scalable systems for optical interconnects, LiDAR phased arrays, and photonic tensor cores. Key challenges include reducing driving voltages with on-chip charge pumps and optimizing PZT films for nanosecond-scale switching. By bridging device innovation with system-level integration, this work lays the groundwork for energy-efficient, brain-inspired photonic processors.

Methods

Basic voltage definition

The poling voltage Vpol is the pulse voltage used for poling or erasing of the PZT film ferroelectric domains, ensuring the alignment of all domains.

The Setting Voltage Vset is the pulse voltage (above the threshold voltage Vth) used for non-volatile control of the ferroelectric domain. Unless otherwise stated, Vset generally refers to the control voltage of the non-volatile working state, which will be withdrawn after being applied for a while.

The Driving Voltage Vdr is a time-varying voltage (below the threshold voltage Vth) used for high-speed, volatile modulation via the electro-optic effect.

Working procedure

-

Poling the device by applying the poling voltage Vpol, which is pulsed with a frequency of 1 kHz and an amplitude of 150 V;

-

Apply the setting voltage Vset, which is pulsed with an amplitude greater than Vth;

-

After completing the two steps mentioned above, the device can be controlled by a low drive voltage Vdr (less than Vth) with a high frequency.

Fabrication of PZT optical memristors

For the fabrication of the present PZT optical memristors, the SiO2/Si substrate was first chemically modified with an atomic seed layer to promote the crystallization of PZT in the desired (100)-oriented perovskite phase. The seed layer was prepared using a lanthanum-based precursor solution, spin-coated onto the substrate, and heat-treated on a hot plate at 440 °C for 2–5 minutes under ambient air. This process formed a La2O2CO3 intermediate layer, which minimizes the lattice mismatch (0.5% with PZT) and reduces the nucleation activation energy for low-temperature crystallization. Subsequently, the PZT precursor solution was spin-coated onto the seed layer. The coated film underwent pyrolysis at 250 °C for 20 minutes on a hot plate to remove organic components, followed by rapid thermal annealing (RTA) in an oxygen atmosphere. The RTA process involved heating the substrate to 450 °C at a ramp rate of 10 °C/min, holding for one hour, and cooling at the rate of 10 °C/min. This spin-coating and annealing cycle was repeated twice to achieve a total PZT film thickness of 300 nm. The oxygen atmosphere and controlled ramp rates ensured the phase-pure perovskite formation while adhering to the CMOS-compatible thermal budget (<450 °C). The waveguide structure was patterned using electron-beam lithography (EBL) or ultraviolet stepper lithography, followed by inductively coupled plasma (ICP) etching with CHF3/Ar gas to a depth of 150 nm. A co-planar electrode pattern was then defined via ultraviolet contact lithography. The electrodes, consisting of 5-nm-thick Ti (adhesion layer) and 400-nm-thick Au, were deposited using electron-beam evaporation and lift-off processes. Finally, a 1.8-μm-thick SiO2 film was spin-coated on top as the upper cladding.

PZT device non-volatile characterization

Optical fiber guides the light generated from an ASE and then being coupled into the PZT platform by grating couplers. An optical spectrum analyzer (AQ6370D) was used to acquire transmission spectra with spectral resolution of 10 pm. Then electrical signals were applied to the sample at room temperature for setting and erasing: An arbitrary function generator (SDG1032X) and was programmed to generate sequential voltage pulse cycles at the frequency of 1 kHz, which were then amplified to 30 V and −150 V with a voltage amplifier (HA1600).

Experimental setup for eye diagram measurement

Light from a tunable diode laser (Keysight, 81606 A) was polarization-controlled and coupled to the fabricated PZT chip by grating couplers, and the MRR-based PZT optical memristor was driven by the RF signals generated by the arbitrary waveform generator (AWG, M8199A) amplified by a linear electrical RF amplifier (SHF S807 C) via a 67-GHz RF GSG probe, The output optical signal was amplified using an erbium-doped fiber amplifier (EDFA) comprising an optical bandpass filter and collected by an electrical sampling oscilloscope connected to the oscilloscope(N1000A).

Experimental setup for high-speed optical signal-processing

A tunable laser was used as the light source and was coupled into the PZT optical memristors through a grating coupler. Here, a polarization controller (PC) was used to achieve TE-polarized light for the input. A continuous rectangular-wave signal with different modulated frequencies generated from an arbitrary function generator (AFG) was then applied to the PZT optical memristor. The modulated optical signals were coupled from the chip to the fiber connected with a10%: 90% power splitter and the port with 90% output-power was connected to the oscilloscope (DSO) via a photodetector (PD), while the other 10% output-power was collected by an optical spectrum analyzer, which allowed synchronized observation of the operating wavelength.

Experimental setup for High-bit-rate data routing

For high-bit-rate data routing with the developed memristive optical switch matrix in Fig. 5, the tunable laser was set at 1550 nm with an output power of 13 dBm injected into a LiNbO3 Mach-Zehnder modulator. The high-speed OOK signals with a standard pseudo-random binary sequence (PRBS) pattern were generated by an arbitrary waveform generator (AWG) and then amplified by the commercial RF amplifier and finally were injected to drive the LiNbO3 modulator. The modulated optical signals were then sent to the memristive optical switch matrix. At the receiving end, the optical signals were amplified by an EDFA and subsequently analyzed with a sampling oscilloscope.

Data availability

Data underlying the results presented in this paper are available from the authors upon request. Source data are provided with this paper.

References

Strukov, D. B., Snider, G. S., Stewart, D. R. & Williams, R. S. The missing memristor found. Nature 453, 80–83 (2008).

Youngblood, N., Ríos, Ocampo, C. A., Pernice, W. H. P. & Bhaskaran, H. Integrated optical memristors. Nat. Photonics 17, 561–572 (2023).

Ríos, C. et al. In-memory computing on a photonic platform. Sci. Adv. 5, eaau5759 (2019).

Feldmann, J., Youngblood, N., Wright, C. D., Bhaskaran, H. & Pernice, W. H. All-optical spiking neurosynaptic networks with self-learning capabilities. Nature 569, 208–214 (2019).

Feldmann, J. et al. Parallel convolutional processing using an integrated photonic tensor core. Nature 589, 52–58 (2021).

Lian, C. et al. Photonic (computational) memories: tunable nanophotonics for data storage and computing. Nanophotonics 11, 3823–3854 (2022).

Shastri, B. J. et al. Photonics for artificial intelligence and neuromorphic computing. Nat. Photonics 15, 102–114 (2021).

Zhang, Y. et al. Electrically reconfigurable non-volatile metasurface using low-loss optical phase-change material. Nat. Nanotechnol. 16, 661–666 (2021).

Wuttig, M., Bhaskaran, H. & Taubner, T. Phase-change materials for non-volatile photonic applications. Nat. Photonics 11, 465–476 (2017).

Fang, Z. et al. Arbitrary Programming of Racetrack Resonators Using Low-Loss Phase-Change Material Sb2Se3. Nano Lett. 24, 97–103 (2023).

Fang, Z. et al. Ultra-low-energy programmable non-volatile silicon photonics based on phase-change materials with graphene heaters. Nat. Nanotechnol. 17, 842–848 (2022).

Chen, R. et al. Non-volatile electrically programmable integrated photonics with a 5-bit operation. Nat. Commun. 14, 3465 (2023).

Ríos, C. et al. Integrated all-photonic non-volatile multi-level memory. Nat. Photonics 9, 725–732 (2015).

Wei, M. et al. Monolithic back-end-of-line integration of phase change materials into foundry-manufactured silicon photonics. Nat. Commun. 15, 2786 (2024).

Zhang, H. et al. Miniature multilevel optical memristive switch using phase change material. ACS Photonics 6, 2205–2212 (2019).

Zheng, J. et al. Nonvolatile electrically reconfigurable integrated photonic switch enabled by a silicon PIN diode heater. Adv. Mater. 32, 2001218 (2020).

Kim, D. U. et al. Programmable photonic arrays based on microelectromechanical elements with femtowatt-level standby power consumption. Nat. Photonics 17, 1089–1096 (2023).

Edinger, P. et al. A bistable silicon photonic mems phase switch for nonvolatile photonic circuits. In: 2022 IEEE 35th International Conference on Micro Electro Mechanical Systems Conference (MEMS) (eds. IEEE MEMS 2022 Technical Program Committee) 995–997 (IEEE).

Pintus, P. et al. Integrated non-reciprocal magneto-optics with ultra-high endurance for photonic in-memory computing. Nat. Photonics 19, 54–62 (2024).

Cheung, S. et al. Energy efficient photonic memory based on electrically programmable embedded III-V/Si memristors: switches and filters. Commun. Eng. 3 (2024).

Tossoun, B. et al. High-speed and energy-efficient non-volatile silicon photonic memory based on heterogeneously integrated memresonator. Nat. Commun. 15, 551 (2024).

Guo, R. et al. Non-volatile memory based on the ferroelectric photovoltaic effect. Nat. Commun. 4, 1990 (2013).

Geler-Kremer, J. et al. A ferroelectric multilevel non-volatile photonic phase shifter. Nat. Photonics 16, 491–497 (2022).

Team, P. A manufacturable platform for photonic quantum computing. Nature 1-3 (2025).

Yang, G. et al. Processing-in-memory using optically-addressed phase change memory. In: 2023 IEEE/ACM International Symposium on Low Power Electronics and Design (ISLPED) (eds. IEEE/ACM ISLPED 2023 Technical Program Committee) 1–6 (IEEE).

Rahimi Kari, S. et al. High-speed multifunctional photonic memory on a foundry-processed photonic platform. Optica 12 (2025).

Dimos, D., Potter, B. G., Sinclair, M. B., Tuttle, B. A. & Warren, W. L. Photo-induced and electrooptic properties of (Pb,La)(Zr,Ti)O3 films for optical memories. Integr. Ferroelectr. 5, 47–58 (2006).

Thakoor, S., Olson, E. & Nixon, R. H. Optically addressed ferroelectric memory and its applications. Integr. Ferroelectr. 4, 257–269 (2006).

Alexander, K. et al. Nanophotonic Pockels modulators on a silicon nitride platform. Nat. Commun. 9, 3444 (2018).

Yu, H. et al. Thin-film lead zirconate titanate nanobeam electro-optic modulator. ACS Photonics 12, 1015–1021 (2025).

Xie, Y. et al. Towards large-scale programmable silicon photonic chip for signal processing. Nanophotonics 13, 2051–2073 (2024).

Mao, J. et al. Ultra-fast perovskite electro-optic modulator and multi-band transmission up to 300 Gbit s−1. Commun. Mater. 5, 114 (2024).

Delaney, M. et al. Nonvolatile programmable silicon photonics using an ultralow-loss Sb2Se3 phase change materia. Sci. Adv. 7, 3500 (2021).

Lvovsky, A. I., Sanders, B. C. & Tittel, W. Optical quantum memory. Nat. Photonics 3, 706–714 (2009).

Zheng, Y. et al. Multichip multidimensional quantum networks with entanglement retrievability. Science 381, 221–226 (2023).

Xu, Z. et al. Large-scale photonic chiplet Taichi empowers 160-TOPS/W artificial general intelligence. Science 384, 6692 (2024).

Zhang, W. et al. Edge learning using a fully integrated neuro-inspired memristor chip. Science 381, 1205–1211 (2023).

Ban, D. et al. High electro-optic coefficient lead zirconate titanate films toward low-power and compact modulators. Opt. Mater. Express 11 (2021).

Li, B. et al. Measuring the effective electro-optic coefficient of low-temperature-prepared lead zirconate titanate thin films. Materials (Basel) 18 (2025).

Dawber, M. Physics of thin-film ferroelectric oxides. Rev. Mod. Phys. 77 (2005).

Jung, D. J., Morrison, F. D., Dawber, M., Kim, H. H., Kim, K., & Scott, J. F. Effect of microgeometry on switching and transport in lead zirconate titanate capacitors: Implications for etching of nano-ferroelectrics. J. Appl. Phys. 95 (2004).

Merz, W. J. Domain formation and domain wall motions in ferroelectric BaTiO3 single crystals. Phys. Rev. 95, 690–698 (1954).

Morioka, H., Asano, G., Oikawa, T., Funakubo, H. & Saito, K. Large remanent polarization of 100% polar-axis-oriented epitaxial tetragonal Pb (Zr0.35Ti0.65) O3 thin films. Appl. Phys. Lett. 82, 4761–4763 (2003).

Glinchuk, M. et al. Optical refraction index and polarization profile of ferroelectric thin films. Integr. Ferroelectr. 38, 101–110 (2001).

Zhou, D. et al. Electric field and temperature scaling of polarization reversal in silicon doped hafnium oxide ferroelectric thin films. Acta Mater. 99, 240–246 (2015).

Prabu, M., Shameem Banu, I. B., Gobalakrishnan, S. & Chavali, M. Electrical and ferroelectric properties of undoped and La-doped PZT (52/48) electroceramics synthesized by sol–gel method. J. Alloy. Compd. 551, 200–207 (2013).

Bednyakov, P. S., Sturman, B. I., Sluka, T., Tagantsev, A. K. & Yudin, P. V. Physics and applications of charged domain walls. npj Comput. Mater. 4 (2018).

Salvestrini, J. P., Guilbert, L., Fontana, M., Abarkan, M. & Gille, S. Analysis and control of the DC drift in LiNbO3 based Mach–Zehnder modulators. J. Lightwave Technol. 29, 1522–1534 (2011).

Shen, Y. et al. Deep learning with coherent nanophotonic circuits. Nat. Photonics 11, 441–446 (2017).

Lu, K. et al. Empowering high-dimensional optical fiber communications with integrated photonic processors. Nat. Commun. 15, 3515 (2024).

Chen, X., Lin, J. & Wang, K. A review of silicon-based integrated optical switches. Laser Photonics Rev. 17, 2200571 (2023).

Wang, C. et al. Integrated lithium niobate electro-optic modulators operating at CMOS-compatible voltages. Nature 562, 101–104 (2018).

Li, X., Gao, W., Lu, L., Chen, J. & Zhou, L. Ultra-low-loss multi-layer 8 × 8 microring optical switch. Photonics Res. 11, 712–723 (2023).

Zhang, C. et al. Reconfigurable multichannel amplitude equalizer based on cascaded silicon photonic microrings. Photonics Res. 11, 742–749 (2023).

Eppenberger, M. et al. Resonant plasmonic micro-racetrack modulators with high bandwidth and high temperature tolerance. Nat. Photonics 17, 360–367 (2023).

Rizzo, A. et al. Massively scalable Kerr comb-driven silicon photonic link. Nat. Photonics 17, 781–790 (2023).

Holzgrafe, J. et al. Relaxation of the electro-optic response in thin-film lithium niobate modulators. Opt. Express 32, 3619–3631 (2024).

Song, L. et al. Low-loss calibration-free 2× 2 Mach-Zehnder switches with varied-width multimode-interference couplers. J. Lightwave Technol. 40, 5254–5259 (2022).

Khope, A. S. P. et al. Multi-wavelength selective crossbar switch. Opt. Express 27, 5203–5216 (2019).

Bai, B. et al. Microcomb-based integrated photonic processing unit. Nat. Commun. 14, 66 (2023).

Xu, S., Wang, J., Yi, S. & Zou, W. High-order tensor flow processing using integrated photonic circuits. Nat. Commun. 13, 7970 (2022).

Wang, W. et al. Cascaded subarray design and control method for power efficient, thermal crosstalk optimized optical phased array. Opt. Express 31, 37381–37394 (2023).

Bruckerhoff-Pluckelmann, F. et al. Probabilistic photonic computing with chaotic light. Nat. Commun. 15, 10445 (2024).

Dong, B. et al. Partial coherence enhances parallelized photonic computing. Nature 632, 55–62 (2024).

Dong, B. et al. Higher-dimensional processing using a photonic tensor core with continuous-time data. Nat. Photonics 17, 1080–1088 (2023).

Halter, M. et al. Back-end, CMOS-compatible ferroelectric field-effect transistor for synaptic weights. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 12, 17725–17732 (2020).

Kobayashi, T., Suzuki, Y., Makimoto, N., Funakubo, H. & Maeda, R. Influence of pulse poling on the piezoelectric property of Pb (Zr0.52, Ti0.48) O3 thin films. AIP Adv. 4 (2014).

Larsen, P. K., Kampschöer, G. L. M., Ulenaers, M. J. E., Spierings, G. A. C. M. & Cuppens, R. Nanosecond switching of thin ferroelectric films. Appl. Phys. Lett. 59, 611–613 (1991).

Shen, B., Bose, S. & Johnston, M. L. Fully-Integrated Charge Pump Design Optimization for Above-Breakdown Biasing of Single-Photon Avalanche Diodes in 0.13-μm CMOS. IEEE Trans. Circuits Syst. I Regul. Pap. 66, 1258–1269 (2019).

Seok, T. J., Kwon, K., Henriksson, J., Luo, J. & Wu, M. C. Wafer-scale silicon photonic switches beyond die size limit. Optica 6 (2019).

Acknowledgements

The authors acknowledge support from the National Natural Science Foundation of China (62405271, U23B2047, 62321166651, 62305294, 62405070 and 92150302), Natural Science Foundation of Zhejiang Province (LD19F050001), Zhejiang Provincial Major Research and Development Program (2022C01103), Fundamental Research Funds for the Central Universities, China Postdoctoral Science Foundation (2023M733039), and Leading Innovative and Entrepreneur Team Introduction Program of Zhejiang (2021R01001), “Pioneer” and “Leading Goose” R&D Program of Zhejiang Province (2024C01112).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

D.D. and C.L. conceived the idea, C.L. developed the theory of PZT optical non-volatility, C.L., T.S. and D.D. designed the PZT memristors and the chip layout, T.S., C.L., H.Y. and C.W. fabricated the chip, Y.Z and C.L. carried out the high-speed optical signal-processing of the memristors, H.C. and J.X. built up the system experiments for measuring eye-diagrams, H.Y., H.L., Z.X., Z.Y. W.C. contributed to the discussion of the fabrication and poling process, C.L., D.D., Z. G., Y.Z., L.H., L.L., S.Y. wrote the manuscript, all authors discussed the results and contributed to the manuscript. D.D. and F.Q. supervised the project.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Peer review

Peer review information

Nature Communications thanks Warren Jin and the other, anonymous, reviewers for their contribution to the peer review of this work. A peer review file is available.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Source data

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Li, C., Yu, H., Shu, T. et al. PZT optical memristors. Nat Commun 16, 6340 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-025-61536-0

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-025-61536-0