Abstract

The rare-earth α-pyrochlore iridates are a prospective class of conducting frustrated magnets where electronic correlations, large spin-orbit coupling, and geometrical frustration interplay, leading to a rich set of magnetic and electronic phases. Despite their intriguing properties, the magnetic order and excitations in this fundamental class of topological quantum materials remain poorly understood due to challenges in growing large single crystals and insufficient microscopic information on their temperature-dependent phases. Here, by combining state-of-the-art thin-film synthesis, resonant elastic and inelastic X-ray scattering, spin wave analysis, and dynamical spin susceptibility calculations, we unequivocally reveal the presence of spectrally sharp, gapped magnetic excitations in Y2Ir2O7 that surprisingly persist well above the Néel transition temperature, signaling the presence of a quasi-universal regime connected to fluctuations on frustrated lattices. This finding implies the existence of a highly unusual cooperative paramagnetic (CP) phase above the ordering temperature and offers an explanation for the puzzling high-temperature magnetic behavior observed across the family of metallic pyrochlore crystals. Understanding such magnetic excitations at technologically relevant temperatures opens up possibilities for novel topological spintronic devices.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Geometrically frustrated quantum antiferromagnets (AFM) have played a crucial role in the search for new physics beyond the Landau symmetry-breaking paradigm1,2,3. Unlike conventional ordered magnets, where the low-energy excitations manifest as spin waves (magnons), the frustrated magnets offer collective modes such as Majorana fermions4 and spinons5 which become highly complex due to the quantum effects associated with numerous nearly degenerate spin states6,7,8,9,10. In particular, for the pyrochlore lattice, frustration arises from competing interactions due to the underlying lattice geometry. This opens up possibilities for rich and exotic behaviors, including proposals of quantum spin liquids11,12, unconventional superconductivity13, and topologically non-trivial orders14.

In metallic quantum antiferromagnets, the involvement of mobile electrons creates long-range exchange pathways, enriching the landscape of the interaction beyond those in frustrated insulators15. When charge and spin degrees of freedom are intertwined, frustration facilitates more exotic phenomena, including spin-charge separation16, stripe formation17, and charge18 and valence-bond orders19. On the other hand, additional couplings such as single-ion anisotropy, dipolar and Dzyaloshinskii-Moriya (DM) interactions, or the order-by-disorder effect, partially or entirely remove the ground state’s degeneracy, favoring one of the lower-symmetry ground states. Unlike conventional magnets, in frustrated magnets, the long-range spin ordering near the Curie-Weiss temperature ∣ΘCW∣ is suppressed. Instead, an unusual, strongly correlated regime without long-range spin order emerges in the temperature range between the Néel temperature TN and ∣ΘCW∣.

This regime, known as cooperative paramagnetism (CP)20, has been extensively studied in the context of unusual spin dynamics in spin-ice pyrochlores1,21, spinels6,22, and two-dimensional geometrically frustrated lattices23. However, its exploration in frustrated metallic antiferromagnets remains nascent due to a lack of studies on low-energy physics within the CP regime and a requirement for new theoretical approaches for correlated frustrated metals. In this study, we utilize state-of-the-art resonant elastic and inelastic X-ray scattering to uncover the “four-in-four-out” (4i-4o) AFM ground state in Y2Ir2O7, revealing the persistence of gapped magnon modes above the ordering temperature. Surprisingly, our results demonstrate that the magnetic gap survives up to at least 175 K, well above the Néel temperature of 145 K for this material. The identified highly unusual CP phase could be the first realization of the novel quasi-universal regime predicted to arise in the vicinity of the quantum critical point in the PyIr family24,25. The exotic, spectrally sharp, spin-gapped magnetic excitations found deep in the CP state of a 3D frustrated Weyl semimetal (WSM) suggest the excellent potential of the here-discovered phase for topological quantum spintronics at elevated temperatures.

Results

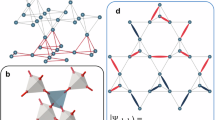

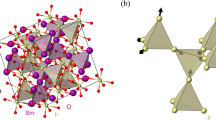

The metallic α-pyrochlore iridates with the chemical formula R2Ir2O7 (hereafter referred to as PyIr; R is a rare-earth element) are a canonical family of materials actively investigated for simultaneously hosting frustrated magnetism26,27,28, chiral spin liquids29, and strongly-correlated topological states13,14,30,31,32,33. At low temperatures, the Ir4+ sites, each with an effective spin Jeff = 1/2, undergo a long-range non-collinear (chiral) antiferromagnetic (AFM) order known as “four-in-four-out” (4i-4o) (illustrated in Fig. 1a) stabilized by the DM interaction. The symmetry of realized magnetic order plays a crucial role in the formation of topological phases, such as the WSM state14,25,34. Angle-resolved photoemission spectroscopy measurements on PyIr uncovered a quadratic band touching (QBT) point, where two doubly-degenerate bands touch quadratically at the zone center Γ33,35, establishing the PyIr as the Luttinger-Abrikosov-Beneslavskii semimetal at high temperatures25,32,36,37. More recently, magnetotransport measurements on PyIr thin films, including Y2Ir2O7 (hereafter YIO), revealed a non-zero anomalous Hall effect29,38, providing strong evidence for the WSM state.

a The pyrochlore lattice features two interpenetrating sublattices of corner-sharing tetrahedra. In the ordered ground state, possible spin configurations include “two-in-two-out” (red arrows), as in the titanates, or “four-in-four-out” (blue arrows), as in the iridates. b The low-temperature electronic and magnetic phases are well-established for pyrochlore iridates with larger ionic radii (Pr-Eu). The phase diagram features optical and charge gap39, SQUID40,41,42,43, REXS38,44,45, and torque magnetometry46 data. For smaller A-site radii, spectroscopic studies are limited due to the lack of availability of large-size single crystals. μSR data indicate the presence of a quantum cooperative paramagnet regime for Y2Ir2O7 (YIO) and Nd2Ir2O747,48. The XRMS data on YIO is revealed for the first time in this manuscript.

A comprehensive experimental phase diagram of PyIr is shown in Fig. 1b38,39,40,41,42,43,44,45,46,47,48. The rare-earth element has a significant impact on the structural and electronic properties of the pyrochlore iridates. Like the other compounds on the left-hand side of the diagram, Y2Ir2O7 exhibits semiconducting behavior (see Supplementary Information Fig. S2), sharply contrasting with the metallic behavior for R=Eu and beyond. Despite extensive macroscopic characterizations, direct measurements of the magnetic ground states and low-energy excitations remain challenging for many scattering approaches, including neutrons, due to the very high absorption cross-section on iridium. In the past, resonant elastic and inelastic X-ray scattering (REXS and RIXS) have been used to detect the 4i-4o magnetic order in several PyIr materials44,45,49,50, notably those on the right side of the phase diagram in Fig. 1b. However, very few REXS and RIXS studies have been conducted on PyIr materials with smaller rare-earth radii (i.e., from Y to Lu). The extreme scarcity of experimental results is linked to the challenges of synthesizing sufficiently large, high-quality single crystals of PyIr. Further, layer-by-layer thin film growth has not been demonstrated due to a lack of compatible substrates, significant oxygen non-stoichiometry, structural defects, and difficulty of in-situ iridium metal oxidation51,52. Recently, a new approach known as hybrid solid phase epitaxy52,53,54,55,56 was developed to enable the growth of large single-crystalline PyIr thin films. This synthesis method creates the long-awaited opportunity for X-ray scattering measurements and offers a new perspective for mapping the unknown magnetic ground states and excitations across the whole family of pyrochlore iridates. To fulfill this goal, we successfully created new high-quality YIO thin films on (111)-oriented single-crystal ZrO2: Y2O3 (YSZ) substrates using hybrid solid-state epitaxy57. Structurally, the YIO films of 100 nm thickness are fully relaxed to the bulk-like lattice parameters, as revealed by reciprocal space mapping given in Section S1 in the Supplementary Information.

With the availability of high-quality (111) oriented films, we demonstrated the presence of long-range magnetic order in YIO using REXS performed at the Ir L3 pre-edge at 11.215 keV, as detailed in the Methods section. We monitored the temperature dependence of a magnetically allowed but structurally forbidden Bragg peak (0 0 10) shown in Fig. 2. To accurately define the critical temperature, we recorded a series of rocking scans around this Bragg reflection in the σ-π scattering channel as a function of temperature (see Fig. 2a). As clearly seen in Fig. 2b, the strong magnetic Bragg reflection at 21 K is completely suppressed around TN ~ 145 K. The REXS measurement establishes, for the first time, the presence of long-range magnetic order and the critical temperature for the transition into the 4i-4o state in single-crystal YIO. Further, fitting the local magnetic moment M deduced from scattering intensity \({I}_{{{{\rm{(0}}}}\,{{{\rm{0}}}}\,{{{\rm{10)}}}}}\propto {\langle {M}_{{{{\rm{Ir}}}}}\rangle }^{2}\propto {({T}_{N}-T)}^{2\beta }\) yields a critical exponent β of 0.30 ± 0.04 (see Supplemental Material S4). This value of β falls into the 3D Ising universality class58, consistent with the theoretically proposed 4i-4o antiferromagnetic ground state (see Fig. 2b inset) due to the discrete symmetry of the effective magnetic Hamiltonian13. The overall temperature-dependent scattering intensity and the critical exponent β are in excellent agreement with the previous report of spontaneous magnetization in zero-field μSR measurements on a polycrystalline YIO48. We note that this value differs from the critical exponent β = 0.2 as found in Eu2Ir2O7 (hereafter EIO)50. This finding, in conjunction with the difference in resistivity behavior near TN, implies that the magnetic behavior in YIO may be markedly different compared to EIO.

a Temperature-dependent scans around the (0 0 10) peak which is magnetically allowed for the 4i-4o spin ordering. The σ − π geometry filters out contributions from the charge channel. The intensity disappears around 145 K. b Each scan was fit to a Lorentzian lineshape, and the peak intensity was plotted as a function of temperature (open circles). The results have a similar profile to the muon precession frequency of YIO (solid circles)48. Inset shows the time-reversal (TR) pair of the 4i-4o and 4o-4i ordering.

To quantitatively describe the magnetic interactions responsible for the 4i-4o ground state, we obtained the magnetic excitation spectra in YIO using resonant inelastic X-ray scattering (RIXS) measurements (see Methods for more details). Collecting RIXS data from thin-film PyIr materials in the hard X-ray regime of several keV presents a significant challenge in suppressing the elastic line. To address this, we positioned the RIXS spectrometer at 2θ ~ 90° to minimize the elastic line contribution59,60,61,62,63. Additionally, we employed an extreme grazing incidence geometry below the critical angle of ~1° and near the structurally forbidden Bragg peak of YIO and YSZ to enhance the inelastic magnetic scattering from the film. The combination of these experimental arrangements greatly suppressed the elastic peak intensity, reducing it to only ~2–4 times the intensity of the low-energy magnetic excitations, as further discussed in Supplementary Information Section S5.

Presented in Fig. 3a is a set of RIXS spectra at 10 K, recorded along the Γ-K direction, which features the most dispersive magnon modes in the Brillouin zone. To detail the magnon dispersion, we fit each RIXS spectrum as the sum of the elastic peak, two separate magnon modes, and a broad magnetic continuum (see Supplementary Information Section S6 for more details). It is worth noting that the magnetic continuum (dashed line) is dispersionless, markedly different from well-defined magnetic quasiparticles (with a full width at half maximum (FWHM) ≥ 200 meV at all momentum transfers q), in accord with previously reported RIXS measurements on Sm2Ir2O7 and Eu2Ir2O745,50. The origin of the continuum was previously proposed as arising from the spontaneous multi-magnon decay64 or, more broadly, incoherent multi-magnon excitations50. In particular, we attribute the origin of this peak to the particle-hole continuum. Decomposing the calculated Lindhard function into its spin and charge channels shows that the continuum appears exclusively in the spin susceptibility channel and is absent in the charge channel. Figure 3b summarizes the magnon dispersion obtained along the Γ-K direction. As immediately seen at the zone center (Γ), two magnon modes at 24(4) meV and 47(3) meV are uncovered in the ground state of YIO. The significant magnon gap at 24(4) meV is a direct manifestation of the magnetic anisotropy. To determine the characteristic energy scales, we fit the experimentally determined magnon dispersion to a minimal effective Hamiltonian that includes nearest-neighbor Heisenberg interactions, J, and an anisotropic DM term with D > 032,36,65 (see Methods for definitions and a description of the Hamiltonian). A direct comparison of the experimental dispersion curves to the linear spin-wave theory gives the values of the magnetic interactions J = 33.9 meV and D = 5.6 meV (see the Supplementary Section S7). The positive sign of D selects the gapped 4i-4o chiral magnetic order over 3i-1o (magnetic monopole) and XY ordering ground states, which theoretically are close in energy to the 4i-4o state but distinguished by the gapless quasi-acoustic magnon branches66. Furthermore, the ratio between the competing interactions, D/J ~ 0.17, is in line with the experimental value of TN = 145 K obtained from the REXS T-scan; see Section S7 in the Supplementary Information for details.

a RIXS curves along Γ-K direction at 10 K. The multi-peak fit at Γ is displayed at the bottom of the figure. b Dispersion of the two magnon modes, which at Γ correspond to Eg1 and Eg2. A gap at Γ is indicative of 4i-4o ordering. Inset shows Γ-K direction for the BZ of a face-centered cubic lattice. c RIXS temperature-dependent curves which show a clear backside to the elastic line at all shown temperatures. The fit at 175 K is displayed at the bottom of the figure. d Color map of temperature-dependent RIXS data after subtraction of the elastic line and magnetic background. A magnon gap is clearly seen, indicating the presence of gapped excitations that persist above TN. The fitted magnon modes for T = 10 K are plotted at the bottom of the figure.

We note that the linear spin-wave fit does not fully capture the behavior of the higher-energy mode near Γ. One possibility is that higher-order interactions (e.g., ring exchange) may be necessary to fully capture the spin-wave behavior5. The improvement in the synthesis of high-quality bulk single crystals may allow for the study of dispersion along more high-symmetry directions, clarifying the role of higher-order corrections in the spin-wave dynamics in Y2Ir2O7. Alternatively, calculating the dynamical structure factor within the random-phase approximation (RPA) may be more appropriate for some pyrochlore iridate compounds31; recent work on non-stoichiometric Tb2Ir2O7 also signals that the RPA approach may better fit the dispersion of the smaller rare-earth site pyrochlore iridate compounds67.

Next, we examine the evolution of the magnetic excitations across TN. For this purpose, we acquired the temperature dependence of the magnon spectra by tracking the magnetic modes, specifically the magnon gap at the Γ point below and above the Néel transition temperature. Unexpectedly, the RIXS data displayed in Fig. 3c reveal that the spin gap persists well above TN to at least 175 K, the highest temperature measured due to increased intensity of the elastic line with temperature. A direct inspection of Fig. 3c affirms this feature is most prominent from the hump on the energy loss side of the RIXS spectra between 30 and 50 meV. To further analyze this behavior, we extracted the magnetic spectral weight by removing the elastic line and the temperature-independent inelastic magnetic continuum. The result shown in Fig. 3d reveals that the magnetic excitation gap barely softens, if at all, across the entire temperature range from 10 K to 175 K. The persistence of the unusual magnetic gap, even as the long-range magnetic order melts, is unexpected and unique, standing in sharp contrast to the previous RIXS reports on pyrochlore iridates. Sm2Ir2O7 shows the spectral weight for the magnon mode disappear around the transition temperature45, whereas EIO shows the gap softening at Γ as T approaches TN50. YIO is perhaps a more likely candidate for observing the persistent gapped magnetic excitations since the system lacks a confounding structural phase transition or the renormalization of the Heisenberg interaction observed in EIO. We speculate that this could result from Ir-O-Ir bond angle and Ir-O bond length differences across the pyrochlore iridate family, leading to a deviation of the J1/2 significantly away from the idealized equal superposition of Ir dxy, dyz and dzx orbitals68.

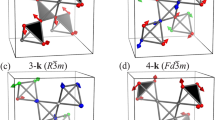

To gain microscopic insight into the persistence of the exotic spin excitations above the Néel temperature, we compare the RIXS spectra with the imaginary part of the orbitally-resolved dynamical transverse spin susceptibility69,70. We compute this quantity within the Lindhard function framework from the realistic electronic band structure for YIO, which we refer to as the dynamical bare transverse spin susceptibility (see details and limitations in Methods and Supplementary Information Section S8). First, we comment on the DFT+U calculations, which show that the ground state of YIO is the 4i-4o WSM for U ≤ 0.9 eV while a topologically trivial Mott insulator arises for larger values of U values (see “Methods”). Our calculations target the non-magnetic solution to describe the paramagnetic states above the Néel transition of three different itinerant models obtained from the first principles for U = 0.85 eV, 1.2 eV, and 1.96 eV, shown in Fig. 4b–d. See Supplementary Information Section S9 for more details about the connection to the WSM phase.

a Illustration of temperature evolution of phases in YIO. Above TN, the system enters a CP regime wherein the magnetic order parameter goes to zero, but the spins are still strongly correlated. The system only enters a true paramagnetic state above the Curie-Weiss temperature ∣ΘCW∣. b The DOS around the Fermi level for the paramagnetic state above the Weyl semimetal phase (PM-WSM) for U = 0.85 eV (red) and above the topologically-trivial insulator phase (PM-TT) for U = 1.2 eV (purple) and 1.96 eV (blue). c The integrated intensity of the imaginary part of the dynamical bare transverse spin susceptibility around Γ from the Lindhard function calculation as a function of ω for the same models as given in (b). The values on the y-axis for all curves are normalized to the maximum of the integrated intensity \({\sum }_{\delta {{{\bf{q}}}}}{\chi }_{0}^{\perp }(\delta {{{\bf{q}}}},\omega )\) for U = 0.85 eV. d Momentum-resolved imaginary part of the dynamical bare transverse spin susceptibility for the model with U = 0.85 eV calculated along Γ-K/3 direction. The values of parameters for calculations on all panels are given in “Methods”.

Figure 4b shows the electronic density of states (DOS) near the Fermi energy for the non-magnetic solutions of these three U values (labeled by “PM”). All three solutions are metallic and display two peaks in the DOS around the Fermi level: one below and one centered at the Fermi level. The dynamical bare transverse spin susceptibility integrated around the zone center for these three models is given in Fig. 4c. As seen, all models qualitatively exhibit the same response, featuring a low-energy peak centered around 25 meV and a higher-energy broader peak centered at ~70–90 meV. We note, however, that the position of the low-energy peak does not correspond to the gap of the lowest excitations, which appear to be gapless in our calculations, as is discussed in the Supplementary Information. The inconsistency between the gap in the experiment and the calculations remains to be resolved, likely within a more advanced model that better accounts for electronic correlations in the system.

From the momentum-resolved dynamical susceptibility, the low-energy peak can be attributed to sharp paramagnon-like excitations propagating from the zone center, corroborating the experimental discovery of magnetic modes above the Néel transition. We attribute the origin of this peak to a sharp peak in the density of states (DOS) centered precisely at the Fermi level, rendering this system rather unique. In the Lindhard function limit, this peak can favor both charge density wave (CDW, Peierls instability) and 4i-4o (Stoner instability) magnetic order, as evidenced by both spin and charge susceptibility from our calculations (see Supplementary Information Sections S8 and S10). The dominant order can be distinguished within the full RPA treatment, which is computationally very expensive for the fully realistic model of YIO considered here. However, based on the experimental observation of the 4i-4o order, the YIO system clearly selects the magnetic instability. Remarkably, in agreement with experimental findings, our itinerant approach resolves another weaker and broader branch in the excitation spectrum. This branch propagates with a smaller velocity along the Γ-K direction, as shown in Fig. 4d for the model with U = 0.85 eV (see also Supplementary Information Section S10).

Our itinerant calculations also reveal a second, higher-energy, broader peak centered around 70–90 meV. Taking into account its momentum dependence (see Supplementary Information Section S10), we attribute this peak to the characteristic magnetic continuum which was detected by RIXS in many pyrochlore compounds45,50. For the first time, we offer a consistent explanation for the origin of these excitations. Specifically, they appear only in the transverse spin and not charge susceptibility channel (see Supplementary Information Section S10), confirming their fully magnetic character. Additionally, we can link their origin to the particle-hole continuum, as the energy of these excitations can be associated with the energy separation between the two peaks near the Fermi level in the DOS given in Fig. 4a. This interpretation is further supported by the finding that as U increases, both the energy gap between the two peaks in the DOS decreases, and the magnetic continuum shifts towards lower energies, as illustrated in Fig. 4b, c. While our calculations (on the level of Lindhard function calculation) very well capture the high-energy excitations, and the presence of two magnon branches in the low-energy excitations (as discussed in the Supplementary Information), they do not reproduce the experimentally observed gap magnitude.

Discussion

Now, we turn our attention to the physical origin of the gapped excitations above TN observed both in the experiment and theory, emphasizing the relative hierarchy of the energy scales in YIO sketched in Fig. 4a. To quantify the effect of frustration on the state above the AFM transition in YIO, we compare the Néel temperature TN = 145 K, extracted from our REXS data, to the Curie-Weiss temperature ΘCW ~ 350–450 K, deduced from the SQUID magnetization measurements71,72. The large mismatch between these two thermal scales corresponds to a frustration factor f = ∣ΘCW∣/TN ~ 2 − 3, implying the presence of a cooperative paramagnetic (CP) regime for TN < T < ΘCW, characterized by strong spin correlations, dynamic fluctuations, and the absence of long-range magnetic order (see Fig. 1b). Similarly to the gas-liquid transition, the CP phase continuously connects the spin state just above the 4i-4o transition temperature to the high-temperature paramagnetic phase characterized by the exchange coupling J. Further, in YIO, a careful examination of the zero- and longitudinal-field spectra from muon spin resonance (μSR) shows a loss of asymmetry due to the onset of oscillations starting around 190 K, indicating the increasing presence of local spin fluctuations well above TN48. Additionally, the magnetic entropy of 6.84 J ⋅ mol−1 ⋅ K−1, extracted from specific heat data at 200 K, is unexpectedly far below the anticipated value of \(2R\ln 2 \sim 11.5\) J ⋅ mol−1 ⋅ K−1 in the state above TN73. Along with our RIXS and REXS results, these macroscopic probes strongly support the notion of the exotic CP phase in YIO.

Furthermore, the identified unconventional CP phase could be the first realization of the exotic quasi-universal regime theoretically predicted to arise in the critical fan above the quantum critical point (QCP) in the PyIr family24,25,74,75. Remarkably, the quasi-universal regime is also expected to sustain long-lived paramagnons. A detailed future study on the scaling behavior in the CP phase will be essential to definitively link the discovered CP phase with the novel quasi-universality regime in the vicinity of the 4i-4o Weyl QCP.

In the following discussion, we speculate about the spin dynamics in the CP state of YIO, as illustrated in Fig. 4a. The reference state at zero temperature is a 4i-4o long-range order, with natural excitations being magnons that have a spin bandwidth on the order of the largest exchange energy J. In conventional magnets, one expects magnons to remain as sharp spectral features for T < TN, with increased thermal broadening as the temperature rises. However, in systems where the transition temperature TN is suppressed relative to J (due to enhanced quantum fluctuations from e.g. low dimensionality or geometric frustration), short-range spin-spin correlations that retain characteristics of the reference state can persist above TN. In such cases, magnetic excitations can exhibit distinct spectral features up to a temperature T⋆, which is on the order of the magnon bandwidth. This leads to the CP regime for TN < T < T⋆, potentially extending it up to ΘCW. Next, for an extreme example, in an ideal spin liquid (SL), the transition temperature is suppressed to zero, but magnetic excitations—gapped or gapless depending on the system—can still be observed experimentally. Particularly, previous experiments and theoretical studies in quasi-1D systems have shown that the spectral properties of these systems (which can exhibit sharp features from magnons or spinon Van Hove singularities at zero temperature) evolve smoothly and continuously, with sharp features broadening slowly with increasing temperature until they disappear at T⋆76,77,78. In addition, the persistence of spectrally sharp magnetic excitations above TN has also been found in the insulating low-dimensional compounds such as 2D triangular antiferromagnets YMnO379 and KYbSe280, layered iridate Sr2IrO481, van der Waals antiferromagnet NiPS382, a ladder-like spin-dimer magnet TlCuCl383, a Heisenberg chain YbAlO384, and the Ruddlesden-Popper members of the Hg-based cuprates85. However, the finding reported here of sharp gapped paramagnons in a 3D frustrated metallic antiferromagnet is unique and challenges the conventional symmetry-breaking picture. In our case, the magnon gap, established by D, is on the order of 25 meV, so even at TN ~ 145 K (equivalent to 12 meV), the minimum excitation energy is still well above TN. This, in turn, implies the exceptional robustness of the magnetic modes, explaining the persistence of nearly undamped magnetic excitations observed in our RIXS experiment within the CP phase.

Finally, we highlight the exciting potential of frustration phenomena in oriented epitaxial films of metallic pyrochlores for spin manipulation. While the studies of frustrated quantum magnets and spintronics have evolved mostly independently, their integration could bring significant mutual advancements86. Particularly, quantum magnets with exotic excitations, such as Majorana fermions, spinons, and magnetic monopoles, offer promising paths for quantum and topological spintronics87,88,89. In these systems, local electric probes could manipulate these excitations, encoding information in a way similar to spin waves and electrons. In return, standard spin-charge conversion methods, such as charge injection and the spin Hall effect, could reveal new fundamental behaviors of frustrated correlated metals in thin film form. The discovery of high-temperature, spectrally sharp magnetic excitations in metallic topological pyrochlores opens the ample potential for quantum spintronics and magnon-based transduction devices90 with new functionalities under technologically relevant conditions.

Methods

Sample preparation and characterization

The (111)-oriented Y2Ir2O7 (YIO) thin films were grown on 5 × 5 mm2 (111) yttria-stabilized zirconia (Y2O3: ZrO2) substrates by a multi-stage in-situ solid phase epitaxy (SPE) method as in ref. 57. An iridium-rich phase-mixed ceramic target (Y:Ir = 1:3) was ablated using a KrF excimer laser (λ = 248 nm, energy density 6 J/cm2) with a repetition rate of 10 Hz. In the deposition stage, the substrate was heated to 550 °C, and the chamber was held at 35 mTorr in a mixture of Ar and O2 gases (partial pressure ratio, Ar:O2 = 10:1). Then, the film was post-annealed inside the chamber at 1000 °C, under 500 Torr atmosphere of pure O2 for 30 min, and afterward cooled to room temperature. Applied SPE annealing time is found to vary about 2–3 times depending on amorphous film thickness and substrate-target distances. X-ray diffraction was used to confirm the high structural quality of the films.

Resonant elastic X-ray scattering (REXS)

The REXS experiments were performed at the beamline 6-ID-B of the Advanced Photon Source (APS) and beamline 4-ID of the National Synchrotron Light Source II (NSLS-II). To maximize the magnetic diffraction cross-section, we took a resonance profile which revealed the Ir L3 pre-edge at 11.215 keV. To further suppress the charge contribution, we collected the magnetic Bragg peak intensity in the σ-π scattering channel. To suppress the charge contribution, we acquired a series of scans around (0 0 4n + 2) (n = 0, 1, 2) Bragg peaks. These Bragg peaks are structurally forbidden but are magnetically allowed for a 4i-4o spin configuration. Additionally, we eliminated the remnant contribution from the aspherical charge distribution of 5d electrons collecting the magnetic Bragg peak intensity in the σ-π scattering channel. For further details, see the Supplementary Information Section S3. Here, we note that a very high neutron absorption cross-section on Ir renders resonant X-rays the only practical bulk momentum-resolved probe of low-energy excitations in iridium-based materials.

Resonant inelastic X-ray scattering (RIXS)

RIXS measurements were performed at the 27-ID-B end-station of the Advanced Photon Source. Measurements were taken at the Ir L3 pre-edge with an incident energy of 11.215 keV to enhance the magnetic scattering cross-section. The total energy resolution of the RIXS setup was 29 meV as determined using substrate (6 6 6) peak at the base temperature of 10–15 K. The X-ray photons scattered from the thin film were subsequently collected using a Si (8 4 4) energy analyzer with a spectrometer arm length of 2 m. The RIXS spectra were collected using a LAMBDA detector with a pixel size of 55 μm.

Linear spin wave modeling

We model the system using a spin (local moment) model Hamiltonian, defined as

where Si represents the effective spin-1/2 operator at site i. Here, J represents the Heisenberg exchange strength, and the \({{{{\rm{D}}}}}_{ij}=D{\hat{d}}_{ij}\) term describes the bond-dependent Dzyaloshinskii-Moriya (DM) interactions91, parametrized by strength D and unit DM vectors \({\hat{d}}_{ij}\). The summation is performed over nearest-neighbor pairs 〈i, j〉. The Hamiltonian was derived for the bulk36,65 and is expected to also hold in our films, at least several layers away from the boundaries13. We performed a linear spin-wave calculation assuming the 4i-4o order13, and fit the dispersion to RIXS data by minimizing the \({\chi }_{{{{\rm{red}}}}}^{2}\) between calculated and observed energies along the Γ-K-\({\Gamma }^{{\prime} }\) path. We have also performed a classical Monte Carlo simulation for the fitted model that supports an AFM transition at TN ≳ 127 K, a value reasonably close to the experimental critical temperature of 145 K. See Section S7 in the Supplementary Information for details.

Density functional theory calculations

To obtain the electronic structure of YIO, we performed first-principles density functional calculations implemented in the Vienna ab initio simulation package (VASP)92,93 with an exchange-correlation PBE functional94 and an on-site interaction95U applied to the Ir d-orbitals, with non-collinear spin configurations and spin-orbit coupling included. We have identified the range U ≤ 0.9 eV as the region where the ground state exhibits a Weyl semimetal phase (with small electron and hole pockets near U = 0.9 eV), beyond which the system transitions to an insulating state. See Supplementary Information, Section S11, for additional details. As seen, the 4-in/4-out magnetic ordering remains robust for all values of U ≥ 0.75 eV. We estimated the ground state to appear for U = 1.96 eV for the Ir d-orbitals using the linear response theory within DFT + U96, where the ground state of YIO appears as a 4i-4o insulator with a small gap of 0.38 eV. The spectral functions were computed using WANNIERTOOLS97 for a 41-layer (111)-slab, with the top (bottom) terminated surfaces as kagome (triangle) Ir atomic planes, as described by a tight-binding Hamiltonian downfolded from the DFT + U calculations to the Ir t2g orbitals using Wannier9098. We used the rotationally invariant approach for DFT + U95, with a single Hubbard U parameter correlating the d-shell of the Ir sites. Comparisons of the electronic structures obtained from DFT + eDMFT are provided in the Supplementary Material Sections S12 and S13.

Susceptibility calculations

We consider full 24-orbital spin-resolved Wannier models in the paramagnetic state derived from DFT + U calculations, including SOC

where \({t}_{ia\sigma,jb{\sigma }^{{\prime} }}\) are hopping matrix elements, and the operator \({c}_{ia\sigma }^{{{\dagger}} }\) creates an electron at site i in orbital a ∈ {1, …12} with spin polarization σ ∈ {↑, ↓}. The PM models are obtained within a self-consistent field calculation by enforcing zero magnetic moments at all atomic sites with SOC included.

In Fig. 4b, we show the total density of states (DOS) for different models considered. The DOS is calculated as

where δ corresponds to the broadening, EF denotes the Fermi level, and the summation is performed over energies Ei ≤ E that correspond to NE filled states. The Fermi level corresponds to a filling of n = 20 electrons per unit cell.

We calculate the dynamical bare spin and charge susceptibilities given by refs. 69,99

where m, n denote bands and a, b denote orbitals. The tensor \({{{{\mathcal{M}}}}}_{abba}^{mn}({{{\bf{k}}}},{{{\bf{q}}}})\) takes a different form for different spin- and charge- channels as discussed in detail in Supplementary Information Section S8. Here, N is the total number of k-points considered for the discretization of the reciprocal primitive unit cell, m, n index energy bands with energies \({\varepsilon }_{{{{\bf{k}}}}}^{n}\) obtained from the tight-binding Hamiltonian with respect to the Fermi level, and \({n}_{F}({\varepsilon }_{{{{\bf{k}}}}}^{n})=1/[{e}^{{\varepsilon }_{{{{\bf{k}}}}}^{n}/{k}_{B}T}+1]\) is the Fermi-Dirac distribution function at temperature T, where kB is the Boltzmann constant.

Calculations shown in Fig. 4b–c contrast the results for the paramagnetic states above the Néel temperature of the Weyl phase (U = 0.85 eV) and above the nearby topologically trivial phases (U = 1.2 and 1.96 eV). The electronic density of states (DOS) shown in Fig. 4b for all models is calculated on a 60 × 60 × 60 k-point grid. The imaginary part of the dynamical bare transverse spin susceptibility shown in Fig. 4c is obtained at the temperature kBT = 0.015 eV, with the broadening η = 3 meV, using a discretization of the first Brillouin zone with a 20 × 20 × 20 k-point grid. The integration around the zone center is obtained by summation over 3 × 3 × 3 q-points considering linear sizes of 5% around Γ. Figure 4d is obtained at the temperature kBT = 0.015 eV, with the broadening η = 2 meV, using a discretization of the first Brillouin zone with a 30 × 30 × 30 k-point grid. The calculation is obtained for 26 points along Γ − K/3 direction. The i-th curve at frequency ω = 1.6i meV is shifted along the y-axis by an additional amount of 0.12i.

Results presented here are obtained on the level of calculation of the spin- and charge-resolved channels of the Lindhard response function. A more thorough study should take into account the role of short-range interactions, such as within the random phase approximation (RPA). The inclusion of interactions is not expected to introduce new features in the spectrum, but the relative intensity of different magnon branches in the spectrum can significantly change, as shown in, e.g. refs. 100,101,102. Such calculations lie beyond the scope of this paper.

Data availability

The RIXS and REXS data generated in this study have been deposited in the Github database at https://github.com/michaelterilli/y227_rixs103.

Code availability

Code relevant to data analysis in this study is available at https://github.com/michaelterilli/y227_rixs103.

References

Castelnovo, C., Moessner, R. & Sondhi, S. L. Magnetic monopoles in spin ice. Nature 451, 42–45 (2008).

Sibille, R. et al. Experimental signatures of emergent quantum electrodynamics in Pr2Hf2O7. Nat. Phys. 14, 711–715 (2018).

Yang, J., Zhang, H., Zhang, H. & Hao, L. Perspective on antiferromagnetic iridates for spintronics. APL Mater. 11, 070901 (2023).

Do, S.-H. et al. Majorana fermions in the Kitaev quantum spin system α-RuCl3. Nat. Phys. 13, 1079–1084 (2017).

Coldea, R., Tennant, D. A., Tsvelik, A. M. & Tylczynski, Z. Experimental realization of a 2d fractional quantum spin liquid. Phys. Rev. Lett. 86, 1335–1338 (2001).

Lee, S. H. et al. Emergent excitations in a geometrically frustrated magnet. Nature 418, 856–858 (2002).

Hirobe, D. et al. One-dimensional spinon spin currents. Nat. Phys. 13, 30–34 (2017).

Shen, Y. et al. Fractionalized excitations in the partially magnetized spin liquid candidate YbMgGaO4. Nat. Commun. 9, 4138 (2018).

Janša, N. et al. Observation of two types of fractional excitation in the Kitaev honeycomb magnet. Nat. Phys. 14, 786–790 (2018).

Wulferding, D. et al. Magnon bound states versus anyonic Majorana excitations in the Kitaev honeycomb magnet α-RuCl3. Nat. Commun. 11, 1603 (2020).

Sibille, R. et al. Candidate quantum spin liquid in the Ce3+ pyrochlore stannate \({{{{\rm{Ce}}}}}_{2}{{{{\rm{Sn}}}}}_{2}{{{{\rm{O}}}}}_{7}\). Phys. Rev. Lett. 115, 097202 (2015).

Gao, B. et al. Experimental signatures of a three-dimensional quantum spin liquid in effective spin-1/2 Ce2Zr2O7 pyrochlore. Nat. Phys. 15, 1052–1057 (2019).

Laurell, P. & Fiete, G. A. Topological magnon bands and unconventional superconductivity in pyrochlore iridate thin films. Phys. Rev. Lett. 118, 177201 (2017).

Wan, X., Turner, A. M., Vishwanath, A. & Savrasov, S. Y. Topological semimetal and Fermi-arc surface states in the electronic structure of pyrochlore iridates. Phys. Rev. B 83, 205101 (2011).

Lacroix, C. Frustrated metallic systems:a review of some peculiar behavior. J. Phys. Soc. Jpn. 79, 011008 (2010).

Läuchli, A. & Poilblanc, D. Spin-charge separation in two-dimensional frustrated quantum magnets. Phys. Rev. Lett. 92, 236404 (2004).

Davies, J. E. et al. Frustration driven stripe domain formation in Co/Pt multilayer films. Appl. Phys. Lett. 95, 022505 (2009).

Pinsard-Gaudart, L. et al. Pressure-induced structural phase transition in LiV2O4. Phys. Rev. B 76, 045119 (2007).

Raczkowski, M. & Poilblanc, D. Supersolid phases of a doped valence-bond quantum antiferromagnet: Evidence for a coexisting superconducting order parameter. Phys. Rev. Lett. 103, 027001 (2009).

Villain, J. Insulating spin glasses. Z. f. Phys. B Condens. Matter 33, 31–42 (1979).

Gardner, J. S. et al. Cooperative paramagnetism in the geometrically frustrated pyrochlore antiferromagnet Tb2Ti2O7. Phys. Rev. Lett. 82, 1012–1015 (1999).

Tomiyasu, K. et al. Molecular spin resonance in the geometrically frustrated magnet MgCr2O4 by inelastic neutron scattering. Phys. Rev. Lett. 101, 177401 (2008).

Kundu, S. et al. Signatures of a spin-\(\frac{1}{2}\) cooperative paramagnet in the diluted triangular lattice of Y2CuTiO6. Phys. Rev. Lett. 125, 117206 (2020).

Savary, L., Moon, E.-G. & Balents, L. New type of quantum criticality in the pyrochlore iridates. Phys. Rev. X 4, 041027 (2014).

Moser, D. J. & Janssen, L. Quasiuniversality from all-in–all-out Weyl quantum criticality in pyrochlore iridates. Phys. Rev. B 109, L081111 (2024).

Nakatsuji, S. et al. Metallic spin-liquid behavior of the geometrically frustrated Kondo lattice Pr2Ir2O7. Phys. Rev. Lett. 96, 087204 (2006).

Trump, B. A. et al. Universal geometric frustration in pyrochlores. Nat. Commun. 9, 2619 (2018).

Kavai, M. et al. Inhomogeneous Kondo-lattice in geometrically frustrated Pr2Ir2O7. Nat. Commun. 12, 1377 (2021).

Liu, X. et al. Chiral spin-liquid-like state in pyrochlore iridate thin films. Nat. Commun. 15, 10348 (2024).

Yanagishima, D. & Maeno, Y. Metal-nonmetal changeover in pyrochlore iridates. J. Phys. Soc. Jpn. 70, 2880–2883 (2001).

Lee, E. K.-H., Bhattacharjee, S. & Kim, Y. B. Magnetic excitation spectra in pyrochlore iridates. Phys. Rev. B 87, 214416 (2013).

Witczak-Krempa, W., Go, A. & Kim, Y. B. Pyrochlore electrons under pressure, heat, and field: shedding light on the iridates. Phys. Rev. B 87, 155101 (2013).

Nakayama, M. et al. Slater to Mott crossover in the metal to insulator transition of Nd2Ir2O7. Phys. Rev. Lett. 117, 056403 (2016).

Ueda, K. et al. Magnetic-field induced multiple topological phases in pyrochlore iridates with Mott criticality. Nat. Commun. 8, 15515 (2017).

Kondo, T. et al. Quadratic Fermi node in a 3D strongly correlated semimetal. Nat. Commun. 6, 10042 (2015).

Witczak-Krempa, W. & Kim, Y. B. Topological and magnetic phases of interacting electrons in the pyrochlore iridates. Phys. Rev. B 85, 045124 (2012).

Berke, C., Michetti, P. & Timm, C. Stability of the Weyl-semimetal phase on the pyrochlore lattice. N. J. Phys. 20, 043057 (2018).

Liu, X. et al. Magnetic Weyl semimetallic phase in thin films of Eu2Ir2O7. Phys. Rev. Lett. 127, 277204 (2021).

Ueda, K., Fujioka, J. & Tokura, Y. Variation of optical conductivity spectra in the course of bandwidth-controlled metal-insulator transitions in pyrochlore iridates. Phys. Rev. B 93, 245120 (2016).

Lefrançois, E. et al. Fragmentation in spin ice from magnetic charge injection. Nat. Commun. 8, 209 (2017).

Cathelin, V. et al. Fragmented monopole crystal, dimer entropy, and Coulomb interactions in Dy2Ir2O7. Phys. Rev. Res. 2, 032073 (2020).

Vlášková, K. et al. Magnetic properties and crystal field splitting of the rare-earth pyrochlore Er2Ir2O7. Phys. Rev. B 102, 054428 (2020).

Klicpera, M., Vlášková, K. & Diviš, M. Characterization and magnetic properties of heavy Rare-Earth A2Ir2O7 pyrochlore iridates, the case of Tm2Ir2O7. J. Phys. Chem. C. 124, 20367–20376 (2020).

Tomiyasu, K. et al. Emergence of magnetic long-range order in frustrated pyrochlore Nd2Ir2O7 with metal-insulator transition. J. Phys. Soc. Jpn. 81, 034709–034709 (2011).

Donnerer, C. et al. All-in–all-out magnetic order and propagating spin waves in Sm2Ir2O7. Phys. Rev. Lett. 117, 037201 (2016).

Liang, T. et al. Orthogonal magnetization and symmetry breaking in pyrochlore iridate Eu2Ir2O7. Nat. Phys. 13, 599–603 (2017).

Disseler, S. M. et al. Magnetic order and the electronic ground state in the pyrochlore iridate Nd2Ir2O7. Phys. Rev. B 85, 174441 (2012).

Disseler, S. M. et al. Magnetic order in the pyrochlore iridates A2Ir2O7 (A = Y, Yb). Phys. Rev. B 86, 014428 (2012).

Sagayama, H. et al. Determination of long-range all-in-all-out ordering of Ir4+ moments in a pyrochlore iridate Eu2Ir2O7 by resonant X-ray diffraction. Phys. Rev. B 87, 100403 (2013).

Chun, S. H. et al. Magnetic excitations across the metal-insulator transition in the pyrochlore iridate Eu2Ir2O7. Phys. Rev. Lett. 120, 177203 (2018).

Chakhalian, J., Liu, X. & Fiete, G. A. Strongly correlated and topological states in [111] grown transition metal oxide thin films and heterostructures. APL Mater. 8, 050904 (2020).

Kim, W. J., Song, J., Li, Y. & Noh, T. W. Perspective on solid-phase epitaxy as a method for searching novel topological phases in pyrochlore iridate thin films. APL Mater. 10, 080901 (2022).

Fujita, T. C. et al. Odd-parity magnetoresistance in pyrochlore iridate thin films with broken time-reversal symmetry. Sci. Rep. 5, 9711 (2015).

Gallagher, J. C. et al. Epitaxial growth of iridate pyrochlore Nd2Ir2O7 films. Sci. Rep. 6, 22282 (2016).

Yang, W. C. et al. Epitaxial thin films of pyrochlore iridate Bi2+xIr2−yO7−δ: structure, defects and transport properties. Sci. Rep. 7, 7740 (2017).

Kareev, M. et al. Epitaxial stabilization of a pyrochlore interface between Weyl semimetal and spin ice. Nano Lett. 25, 966–972 (2025).

Liu, X. et al. In-situ fabrication and transport properties of (111) Y2Ir2O7 epitaxial thin film. Appl. Phys. Lett. 117, 041903 (2020).

Ódor, G. Universality classes in nonequilibrium lattice systems. Rev. Mod. Phys. 76, 663–724 (2004).

Kim, J. et al. Magnetic excitation spectra of Sr2IrO4 probed by resonant inelastic X-ray scattering: establishing links to cuprate superconductors. Phys. Rev. Lett. 108, 177003 (2012).

Gretarsson, H. et al. Magnetic excitation spectrum of Na2IrO3 probed with resonant inelastic X-ray scattering. Phys. Rev. B 87, 220407 (2013).

Dean, M. P. M. et al. Ultrafast energy- and momentum-resolved dynamics of magnetic correlations in the photo-doped Mott insulator Sr2IrO4. Nat. Mater. 15, 601–605 (2016).

Meyers, D. et al. Magnetism in iridate heterostructures leveraged by structural distortions. Sci. Rep. 9, 4263 (2019).

Paris, E. et al. Strain engineering of the charge and spin-orbital interactions in Sr2IrO4. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 117, 24764–24770 (2020).

Zhitomirsky, M. E. & Chernyshev, A. L. Colloquium: Spontaneous magnon decays. Rev. Mod. Phys. 85, 219–242 (2013).

Pesin, D. & Balents, L. Mott physics and band topology in materials with strong spin–orbit interaction. Nat. Phys. 6, 376–381 (2010).

Arakawa, N. Magnon dispersion and specific heat of chiral magnets on the pyrochlore lattice. J. Phys. Soc. Jpn. 86, 094705 (2017).

Faure, Q. et al. Spin dynamics and possible topological magnons in non-stoichiometric pyrochlore iridate Tb2Ir2O7 studied by RIXS. Phys. Rev B. 110, L140401 (2024).

Jackeli, G. & Khaliullin, G. Mott insulators in the strong spin-orbit coupling limit: from Heisenberg to a quantum compass and Kitaev models. Phys. Rev. Lett. 102, 017205 (2009).

Kaneshita, E., Tsutsui, K. & Tohyama, T. Spin and orbital characters of excitations in iron arsenide superconductors revealed by simulated resonant inelastic x-ray scattering. Phys. Rev. B 84, 020511 (2011).

Knolle, J., Eremin, I., Chubukov, A. V. & Moessner, R. Theory of itinerant magnetic excitations in the spin-density-wave phase of iron-based superconductors. Phys. Rev. B 81, 140506 (2010).

Krajewska, A. et al. Almost pure \({J}_{{{{\rm{eff}}}}}=\frac{1}{2}\) Mott state of In2Ir2O7 in the limit of reduced intersite hopping. Phys. Rev. B 101, 121101 (2020).

Kumar, H. & Pramanik, A. K. Evolution of magnetic and transport properties in hole doped Y2Ir2O7. J. Phys.: Conf. Ser. 828, 012009 (2017).

Liu, H. et al. Evolution of magnetic and transport properties in pyrochlore iridates A2Ir2O7 (A=Y, Eu, Bi). Wuhan. Univ. J. Nat. Sci. 22, 215–222 (2017).

Boettcher, I. & Herbut, I. F. Anisotropy induces non-Fermi-liquid behavior and nematic magnetic order in three-dimensional Luttinger semimetals. Phys. Rev. B 95, 075149 (2017).

Fidrysiak, M. & Spałek, J. Stable high-temperature paramagnons in a three-dimensional antiferromagnet near quantum criticality: application to TlCuCl3. Phys. Rev. B 95, 174437 (2017).

Kenzelmann, M. et al. Evolution of spin excitations in a gapped antiferromagnet from the quantum to the high-temperature limit. Phys. Rev. B 66, 174412 (2002).

Coldea, R. et al. Quantum criticality in an Ising chain: experimental evidence for emergent E8 symmetry. Science 327, 177–180 (2010).

Scheie, A. et al. Witnessing entanglement in quantum magnets using neutron scattering. Phys. Rev. B 103, 224434 (2021).

Demmel, F. & Chatterji, T. Persistent spin waves above the néel temperature in YMnO3. Phys. Rev. B 76, 212402 (2007).

Scheie, A. O. et al. Proximate spin liquid and fractionalization in the triangular antiferromagnet KYbSe2. Nat. Phys. 20, 74–81 (2024).

Liu, X. et al. Anisotropic softening of magnetic excitations in lightly electron-doped Sr2IrO4. Phys. Rev. B 93, 241102 (2016).

He, W. et al. Magnetically propagating Hund’s exciton in van der Waals antiferromagnet NiPS3. Nat. Commun. 15, 3496 (2024).

Merchant, P. et al. Quantum and classical criticality in a dimerized quantum antiferromagnet. Nat. Phys. 10, 373–379 (2014).

Kish, L. L. et al. High-temperature quantum coherence of spinons in a rare-earth spin chain ArXiv:2406.16753 (2024).

Wang, L. et al. Paramagnons and high-temperature superconductivity in a model family of cuprates. Nat. Commun. 13, 3163 (2022).

Bonbien, V. et al. Topological aspects of antiferromagnets. J. Phys. D Appl. Phys. 55, 103002 (2021).

Šmejkal, L., Mokrousov, Y., Yan, B. & MacDonald, A. H. Topological antiferromagnetic spintronics. Nat. Phys. 14, 242–251 (2018).

He, Q. L., Hughes, T. L., Armitage, N. P., Tokura, Y. & Wang, K. L. Topological spintronics and magnetoelectronics. Nat. Mater. 21, 15–23 (2022).

Baltz, V., Hoffmann, A., Emori, S., Shao, D.-F. & Jungwirth, T. Emerging materials in antiferromagnetic spintronics. APL Mater. 12, 030401 (2024).

Zheng, Y. et al. Paramagnon drag in high thermoelectric figure of merit Li-doped MnTe. Sci. Adv. 5, eaat9461 (2019).

Elhajal, M., Canals, B., Sunyer, R. & Lacroix, C. Ordering in the pyrochlore antiferromagnet due to Dzyaloshinsky-Moriya interactions. Phys. Rev. B 71, 094420 (2005).

Kresse, G. & Furthmüller, J. Efficient iterative schemes for ab initio total-energy calculations using a plane-wave basis set. Phys. Rev. B 54, 11169–11186 (1996).

Kresse, G. & Furthmüller, J. Efficiency of ab-initio total energy calculations for metals and semiconductors using a plane-wave basis set. Comput. Mater. Sci. 6, 15–50 (1996).

Perdew, J. P., Burke, K. & Ernzerhof, M. Generalized gradient approximation made simple. Phys. Rev. Lett. 77, 3865–3868 (1996).

Dudarev, S. L., Botton, G. A., Savrasov, S. Y., Humphreys, C. J. & Sutton, A. P. Electron-energy-loss spectra and the structural stability of nickel oxide: An LSDA+U study. Phys. Rev. B 57, 1505–1509 (1998).

Cococcioni, M. & de Gironcoli, S. Linear response approach to the calculation of the effective interaction parameters in the LDA + U method. Phys. Rev. B 71, 035105 (2005).

Wu, Q., Zhang, S., Song, H.-F., Troyer, M. & Soluyanov, A. A. WannierTools: An open-source software package for novel topological materials. Comput. Phys. Commun. 224, 405–416 (2018).

Mostofi, A. A. et al. An updated version of wannier90: a tool for obtaining maximally-localised Wannier functions. Comput. Phys. Commun. 185, 2309–2310 (2014).

Scherer, D. D. & Andersen, B. M. Spin-orbit coupling and magnetic anisotropy in iron-based superconductors. Phys. Rev. Lett. 121, 037205 (2018).

Knolle, J., Eremin, I. & Moessner, R. Multiorbital spin susceptibility in a magnetically ordered state: orbital versus excitonic spin density wave scenario. Phys. Rev. B 83, 224503 (2011).

Kovacic, M., Christensen, M. H., Gastiasoro, M. N. & Andersen, B. M. Spin excitations in the nematic phase and the metallic stripe spin-density wave phase of iron pnictides. Phys. Rev. B 91, 064424 (2015).

Nedić, A.-M. et al. Competing magnetic fluctuations and orders in a multiorbital model of doped SrCo2As2. Phys. Rev. B 108, 245149 (2023).

Terilli, M. Michaelterilli/y227_rixs: v1 https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.15226090 (2025).

Acknowledgements

M.T., T.-C.W., M.K., and J.C. acknowledge the support by the U.S. Department of Energy, Office of Science, Office of Basic Energy Sciences under award number DE-SC0022160. X.J. and Y.Cao acknowledge the U.S. Department of Energy, Office of Science, Basic Energy Sciences, Materials Science and Engineering Division for supporting the RIXS experiment and data analysis at the Argonne National Laboratory. X.L. acknowledges the support by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (Grant No. 12204521) and the National Key R&D Program of China (Grant No. 2022YFA1403400). The work by P.L. was supported by the U.S. Department of Energy, Office of Science, Basic Energy Sciences, Materials Sciences and Engineering Division. H.L. and J.Z. acknowledge the support from NSF Grant No. DMR-1720595 and DMR-2308817. Y.Chang acknowledges the support of Abrahams Postdoctoral Fellowship from Rutgers University. G.A.F. was supported by the Department of Energy (BES) Award No. DE-SC0022168 (magnetic anisotropy), the National Science Foundation Grant No. DMR-2114825 (magnetic dynamics), and the Alexander von Humboldt Foundation. A.-M.N. was supported by the U.S. Department of Energy (DOE) through the University of Minnesota (UMN) Center for Quantum Materials under Grant No. DE-SC0016371. J.H.P. acknowledges NSF Career Grant No. DMR-1941569 and the Alfred P. Sloan Foundation through a Sloan Research Fellowship. H.C. and W.H. acknowledge support from the U.S. Department of Energy, Office of Science, Office of Basic Energy Sciences Early Career Research Program under Award Number DE-SC-0021305. W.H. acknowledges support from the National Science Foundation under Grant No. 1944957. We acknowledge Daniel Alejandro Bustamante Lopez for measuring the second-harmonic generation signal of the sample. A.-M.N. acknowledges useful discussions with Rafael M. Fernandes, Milan Kornjača, Peter P. Orth, and Yihua Qiang. M.T. and J.C. acknowledge Premala Chandra, Piers Coleman, and Yong-Baek Kim for valuable discussions. This research used resources of the Advanced Photon Source, a U.S. Department of Energy (DOE) Office of Science user facility operated for the DOE Office of Science by Argonne National Laboratory under Contract No. DE-AC02-06CH11357. This research used resources at 4-ID of the National Synchrotron Light Source II, a U.S. Department of Energy (DOE) Office of Science User Facility operated for the DOE Office of Science by Brookhaven National Laboratory under Contract No. DE-SC0012704. This research is funded in part by a QuantEmX grant from ICAM and the Gordon and Betty Moore Foundation through Grant GBMF5305 and GBMF9616 to T.-C.W. Y.Chang would like to thank Kristjan Haule for valuable discussions and help in performing DMFT calculations.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

M.T., Y.Cao, and J.C. conceived the project. H.L. and J.Z. prepared the target for growth, and X.L. and M.K. developed the sample fabrications. T.W. performed the transport measurements. J.-W.K., P.R., and C.N. carried out the resonant elastic X-ray scattering experiments. M.T., X.J., H.C., W.H., and Y.Cao carried out the resonant inelastic X-ray scattering experiments and performed the data analysis with assistance from M.U. and J.K. Spin-wave analysis was carried out by P.L. and G.A.F. Density functional theory calculations were performed by Y.Chang and J.P., and susceptibility calculations were performed by A.-M.N. The manuscript was written by M.T., X.J., Y.Cao, and J.C. All authors discussed the results and commented on the manuscript.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Peer review

Peer review information

Nature Communications thanks Alexander Yaresko and Lukas Janssen for their contribution to the peer review of this work. A peer review file is available.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Terilli, M., Jia, X., Liu, X. et al. Spectrally sharp magnetic excitations above the critical temperature in a frustrated Weyl semimetal. Nat Commun 16, 6576 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-025-61752-8

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-025-61752-8