Abstract

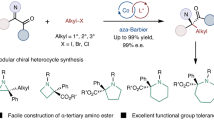

The stereochemical course of nitrogen in tertiary amines has long been overlooked because of the low energy barriers for pyramidal inversion between nitrogen-based conformers. Tröger’s base (TB) is a textbook three-dimensional (3D) molecule with N-centered chirality. Despite the major development of TB chemistry, surprisingly few general strategies are available to access enantioenriched TBs. Here, we report the organocatalytic asymmetric synthesis of TBs via the aminalization of tetrahydrodibenzodiazocines with aromatic aldehydes. This chiral phosphoric acid (CPA)-catalyzed protocol features a broad substrate scope (55 examples), high efficiency (up to 96% yield), and excellent enantioselectivity (up to >99% ee). Density functional theory (DFT) calculations are performed to reveal the reaction mechanism and the origin of the enantioselectivity. The success in preparing TB-polymers and aggregation-induced emission luminogen (AIEgen) demonstrates the potential for widespread applications, especially in the fields of materials science.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

In tertiary amines, lone pair electrons occupy one of the tetrahedral orientations, forming a nitrogen stereocenter. However, the pyramidal inversion of the nitrogen atom enabled by quantum tunneling has a relatively low barrier (20–25 kJ mol−1), therefore the stereochemical course of nitrogen has long been overlooked1,2,3. Embedding nitrogen in bridgehead positions in rigid bicyclic architectures represents among the most effective approach for the preparation of configurationally stable tertiary amines bearing a stereogenic nitrogen atom (Fig. 1A)4,5,6,7. Tröger’s base (TB)8,9,10,11, the first chiral compound with stereogenic nitrogen atoms, was isolated by Julius Tröger from the condensation of p-toluidine and formaldehyde in aqueous hydrochloric acid in 188712. Nearly half a century later, Spielman established the correct structure in 193513, which consists of a methano-1,5-diazocine ring fused with two aromatic rings (Fig. 1B). The central methylene bridge projects the aromatic rings in a nearly perpendicular fashion, making TB a rather rigid cleft-like V-shaped molecule with a hydrophobic cavity. In addition, owing to the presence of two configurationally stable bridgehead N-stereogenic centers on the diazocine ring, TB is an inherently C2-symmetric chiral molecule. Since the successful separation of its enantiomers by Prelog in 194414, TB has become a classic example of “chiral nitrogen” and occupies a place in many stereochemistry textbooks. These intriguing properties have fascinated chemists from multiple research fields, including molecular recognition15,16,17, DNA binding18,19, supramolecular chemistry20,21,22, material science23,24,25, asymmetric catalysis26,27, and drug development28,29,30, just to name a few. Moreover, TBs are valuable building blocks in organic synthesis, capable of producing structurally stable derivatives31,32,33,34,35,36 and functionalized polycyclic molecules37,38,39,40.

Despite the long-term development and widespread application of TB chemistry, surprisingly few general strategies are available for preparing optically pure TBs41. At present, the most common strategy is still to physically separate the two enantiomers of racemic TBs on a chiral stationary phase chromatography42,43,44,45, but alternative methods, including chemical resolution46,47,48, capillary electrophoresis49,50, the chiral auxiliary strategy51,52,53, and CH2-extrusion54, have also been described. In 2013, Cvengroš et al. reported an excellent enzymatic resolution that can prepare two highly functionalized optically active TBs from pre-synthesized racemic substrates55. By using chiral glucose-containing pyridinium ionic liquids, Wu et al. achieved the enantioselective synthesis of pyrazol-TBs56. Very recently, Zhang et al. documented a palladium-catalyzed α-arylation enabled by their home-developed GF-Phos for the rapid construction of a rigid cleft-like structure with both a C- and an N-stereogenic center with high efficiency and selectivity57. Despite these efforts, direct catalytic asymmetric synthesis of TBs still remains an attractive goal. Asymmetric aminalization catalyzed by chiral phosphoric acid (CPA) has become a powerful tool for the facile synthesis of optically active aminals58. In 2008, List and Rueping first applied this strategy to the direct enantioselective synthesis of cyclic aminals from aldehydes59,60. Our group has always been interested in the synthesis of three-dimensional (3D)-shaped molecules61 and CPA catalysis62,63,64,65,66. Here, we show that enantioselective construction of TBs 3 is feasible via the CPA-catalyzed asymmetric aminalization of tetrahydrodibenzodiazocines (THDBDAs) 1 with aromatic aldehydes 2 (Fig. 1C)28,67,68. However, TB is known to racemize in the presence of Brønsted or Lewis acids69,70,71, which poses a daunting challenge to this scenario.

Results

We commenced this investigation with the model reaction of THDBDA 1a with benzaldehyde 2a (Table 1). In his seminal work on optical resolution attended by second-order asymmetric transformation, Wilen used CPA as the resolving agent46. In view of this, we assume that TBs are configurationally stable in the presence of CPA. To our delight, the CPA-catalyzed aminalization reaction readily occurred in CH2Cl2 at ambient temperature, providing the desired TB product 3a in 60% yield (Table 1, entry 1). Owing to the inability of the C1 catalyst to control the enantioselectivity, several other commercial BINOL-derived CPA catalysts were screened (entries 2−4). The results indicated that the triphenylsilyl (SiPh3) group at the 3,3′-position was effective. Spiro skeleton-based CPAs were then employed, with C5 affording the product with an encouraging ee value of 52% (entries 5−7). Therefore, C5 was selected as the best catalyst for the next reaction parameter screening. The reaction was proven to have a background effect, and we decided to mitigate this adverse effect by lowering the reaction temperature (entries 8−11). As expected, at −10 °C, the ee value increased to 66%. In addition, research on the solvent effect revealed that chloroform was superior to other solvents, such as 1,2-dichloroethane (DCE), toluene, tetrahydrofuran (THF), and acetonitrile (entries 12−16). Moreover, the addition of 3 Å molecular sieves (MS) significantly improved the ee to 86% (entry 17). 4 Å MS and 5 Å MS were also effective but not as good as 3 Å MS (entries 18 and 19). When 4-bromobenzaldehyde 2b was used instead of benzaldehyde 2a, the ee value improved to 90% (entry 20). Further lowering the reaction temperature resulted in a product with excellent enantioselectivity (entries 21 and 22). Notably, the newly prepared TB products are configurationally stable in the presence of acids (see the Supplementary Information page S80-S81 for details). Finally, the best reaction conditions were those in entry 22, which afforded 3b in 96% yield with 96% ee.

With the optimal conditions established, we investigated the substrate generality of THDBDAs. As shown in Fig. 2, the reaction was applicable to various symmetric 1, allowing the formation of C2-symmetrical TBs in good yields with typically excellent enantioselectivities. The unsubstituted substrate was well tolerated and delivered 3c in 84% yield with 93% ee. It was practical to change the methyl group at the 2(8)-position to other alkyl groups, such as ethyl, n-propyl, n-butyl, n-amyl, and benzyl groups. The corresponding TB products (3 d−h) were consistently obtained in good yields (85−92%) and excellent ee (92−98%). In addition, a phenyl group (3i) was also compatible with this chemistry. The electron nature of the substituent had a significant impact on the reaction, as the introduction of either an electron-donating methoxyl group (3j) or an electron-withdrawing bromo group (3k) resulted in a significant decrease in the ee. THDBDAs bearing alkyl substituents, including methyl (3 l), ethyl (3 m), i-propyl (3n), and t-butyl (3o) groups, at the 3(9)-position proceeded smoothly to furnish the desired TBs in good yields and enantioselectivities. The phenyl group was also applicable, but could only provide product 3p with 80% ee. Disubstituted substrates were successfully employed, which afforded corresponding products 3q − s in 83−92% yields with 90−95% ee. Tetrahydrodinaphthodiazocine was utilized to access 3t in 85% yield with 84% ee. When an unsymmetrical substrate was employed, a new carbon stereogenic center emerged on the bridge. The electronic properties of the two benzene rings on the THDBDA substrate dominate the diastereoselectivity of the product. For instance, while TB 3 u was obtained with a diastereoselectivity ratio (dr) of 1:1.6, TB 3 v with strongly electronically differentiated two aromatic rings was yield as a single diastereoisomer (dr > 20:1). This result can be rationalized considering a preferred regioselective nucleophilic addition between benzaldehyde and the two amino groups of THDBDA (see the Supplementary Information page S79 for details).

Next, we examined the scope of this reaction with respect to aldehydes 2 (Fig. 3). Benzaldehydes bearing a halo substituent at the para-position were well tolerated, and the reaction afforded corresponding TBs 3w − y in high yields with good enantioselectivities. The reaction with 4-(trifluoromethyl)benzaldehyde also proceeded well to yield product 3z, whose absolute configuration was determined by X-ray crystallographic analysis. Electron-withdrawing groups, such as formyl (3a’), acetyl (3b′), and methoxycarbonyl (3c′), were compatible with the current conditions. 4-Ethynylbenzaldehyde was a suitable reaction partner to produce TB 3 d′ with strong postmodifiability in 90% yield and 92% ee. However, the phenyl group was not suitable for this reaction. Although the yield of product 3e′ was high, the ee was moderate. Electron-donating groups were incompatible with the reaction in terms of the low enantioselectivity. When meta-substituted benzaldehydes were employed, the desired products 3 f′−l′ were all obtained in satisfactory yields with comparably high enantioselectivities. Moreover, disubstituted benzaldehydes worked very well in this aminalization, delivering TB products 3 m′−p′ in 88−94% yields with 90−94% ee. Notably, we successfully applied our protocol to the late-stage functionalization of complicated natural alcohols, including cholesterol, geraniol, perillyl alcohol, menthol, and galactose, and the corresponding products 3q′−u′ were produced in excellent yield and high stereoselectivity.

Encouraged by the successful synthesis of diverse mono-TB compounds, we decided to apply this CPA-catalyzed asymmetric aminalization to prepare more synthetically challenging chiral bis- and tri-TBs, which are potential elementary units for poly-TB network materials (Fig. 4)72. Under standard conditions, terephthalaldehyde 4a reacted with 1a (2.4 equiv), allowing the formation of bis-TB 5a in 72% yield with >99% ee. Moreover, subjection of 3a’ with 90% ee to the reaction also yielded bis-TB 5a with >99% ee (see the SI for details). These results indicated that the combination of the catalytic asymmetric reaction and dimerization led to ee enrichment, i.e., Horeau amplification73. The use of isophthalaldehyde 4b further demonstrated this phenomenon, providing 5b (65%, >99% ee) and its diastereoisomer meso-5b (13%). Given the excellent ee of 3 l′ (Fig. 3), the low diastereoselectivity should be attributed to poor enantio-control during the dimerization process. Similarly, several other optically pure bis-TBs 5c−f were readily prepared from their corresponding dialdehydes. Notably, when the tricarbaldehyde precursors 4 g and 4 h were employed, the modular synthesis of the structurally interesting homochiral tri-TBs 5 g and 5 h was achieved.

To probe the reaction mechanism, Hammett studies were performed on the reactions of para-substituted benzaldehydes with 1a and 2(8)-substituted THDBDAs with 2b. As shown in Fig. 5A, the Hammett plot of the conversion of benzaldehydes vs Hammett σp was linearly correlated. The large positive ρ value of 2.81 indicated that the use of electron-deficient benzaldehydes facilitated the reaction. On the other hand, the poor linear Hammett plot of the conversion of THDBDAs vs Hammett σp indicated a complex relationship between the electronic properties of THDBDAs and the reaction rate (Fig. 5B). In addition, the plot of log(er) values vs Hammett σp values revealed a linear correlation between enantioselectivity and the electronic effect of para substituents on benzaldehyde (Fig. 5C). The negative slope of the plot indicates that the iminium intermediate generated from an electron-deficient aldehyde binds more tightly to the CPA catalyst. A nonlinear effect (NLE) study on the reaction of 1a with 2b revealed a linear relationship between the catalyst and the product (Fig. 5D), implying that the enantio-determining step of this aminalization should involve only one component of CPA. On the basis of these experimental results and previous CPA-catalyzed asymmetric acetalizations74,75, a plausible reaction pathway and transition states (TSs) were proposed (Fig. 5E). The aminalization involves a reaction sequence of addition, dehydration, and cyclization. The CPA catalyst has a dual function here, promoting the formation of iminium and controlling the enantioselectivity. In the enantio-determining step (cyclization), CPA controls enantioselectivity through hydrogen-bonding interactions. Electron-deficient iminiums can enhance this interaction by increasing the acidity of hydrogen, thereby affording higher ee values.

To further explore the general mechanism and origin of the enantioselectivity, density functional theory (DFT) calculations were performed as follows. The relative Gibbs free energy profiles for the C5-catalyzed stereoselective aminalization reaction pathways associated with tetrahydrodibenzodiazocine (1a) and benzaldehyde (2a) are shown in Fig. 6. All calculations have been performed using Gaussian 16 at the M06-2×76,77,78/6-311 + G(d,p)/IEFPCM79,80 trichloromethane//M06-2X/6-31 G(d,p)81,82/IEFPCMtrichloromethane level, and more computational details have been provided in the Supplementary Information (SI). Firstly, under the C5 catalysis, C5 combines with tetrahydrodibenzodiazocine 1a via hydrogen bonding to form intermediates M1SS and M1RR, which then respectively combine with 2a to form the intermediates M2SS and M2RR. Subsequently, the nitrogen atom of 1a nucleophilically attacks benzaldehyde 2a through transition states TS1SS and TS1RR with energy barriers of 6.8 kcal/mol and 6.9 kcal/mol, leading to the formation of zwitterionic intermediates M3SS and M3RR, respectively. Then the zwitterionic intermediates can be transformed to M4SS and M4RR after a proton transfer process, which is followed by a dehydration step. The dehydration occurs through transition states TS2SS (ΔG‡ = 9.9 kcal/mol) and TS2RR (ΔG‡ = 11.2 kcal/mol), respectively, to form the intermediates M5SS and M5RR, indicating that S,S-conformational pathway is more energetically favorable in kinetics. The imine intermediate M5SS can further be transformed to the stereoselectively favored (S,S)-Tröger’s base (PSS) via transition state TS3SS. It should be mentioned that the total energy barrier between TS3SS and M3SS is 0.9 kcal/mol without zero-point energy and thermal corrections, but the Gibbs free energy difference between TS3SS and M3SS is negative (-0.3 kcal/mol) with zero-point energy and thermal corrections, which indicates that this cyclization step is a barrier-less process.

Alternatively, the enantiomer intermediate M5RR undergoes bridged-ring cyclization via transition state TS3RR to form (R,R)-configured Tröger’s base (PRR), and the Gibbs free energy barrier between TS3RR and M3RR is 3.9 kcal/mol. The dehydration has the highest energy barrier, so it should be the rate-determining step of the entire reaction. For this step, we used CREST (v2.12) and xTB package (v6.4.0) to confirm that the transition states TS2SS and TS2RR are the lowest energy conformation and more results can be found in Figure S131 of Supplementary Information.

DFT calculation results indicate that the pathway leading to the (S,S)-conformation is more energetically favorable, which is consistent with the experimental observation. The interaction energy analysis proposed by Houk83,84 and Bickelhaupt85 has been applied to the stereoselective transition states TS2SS and TS2RR. The results revealed that TS2SS has the relatively larger interaction energy (ΔEint = -150.3 kcal/mol) compared to TS2RR (ΔEint = -136.6 kcal/mol), and more details and results provided in SI. Furthermore, the non-covalent interaction (NCI) and atoms in molecules (AIM) analyses86,87 of the key transition states TS2SS and TS2RR were performed to identity the key weak interactions for determining stereoselectivity of the reaction. As shown in Fig. 7, a strong O–H⋯N (1.86 Å) exists in TS2SS, and the stronger π⋯π and C–H⋯π hydrogen bond interactions in TS2SS compared with those in TS2RR, which result in that the pathway associated with TS2SS has a lower energy barrier.

A Dimensional structure of TS2SS, (B) Dimensional structure of TS2RR, (C) NCI and AIM analyses for TS2SS, (D) NCI and AIM analyses for TS2RR. In the three-dimensional structures, oxygen, nitrogen, carbon, phosphorus, silicon, and hydrogen atoms are depicted as red, blue, cyan, brown, yellow, and white balls, respectively. Bond critical points (BCPs) along the bond paths were visualized as small orange balls connected by yellow lines.

Finally, the large-scale synthesis and further transformations of the prepared chiral (methano-) TB products were performed to demonstrate the synthetic utility of this protocol (Fig. 8). Under standard conditions with (ent)-C5, the large-scale synthesis of TB (ent)-3b was readily conducted in 88% yield with 96% ee (Fig. 8A). The functionalized phenyl group in 3 provided a platform for diverse derivatizations (Fig. 8B). For example, TB (ent)-3b underwent a standard Heck coupling reaction with 4-vinylpyridine to yield 6 with excellent enantioselectivity (95% ee). The lithium/bromine exchange of (ent)-3b followed by quenching with chlorodiphenylphosphane afforded TB-phosphine 7 as a chiral ligand. The reduction and oxidation of 3a’ afforded benzyl alcohol 8 and carboxylic acid 9 in good yields, respectively. The assembly of TB 3 d′ with zidovudine, an anti-HIV drug, was successfully established with excellent diastereoselectivity via a copper-catalyzed “click” reaction. Notably, aggregation-induced emission (AIE)88,89,90 was observed by dissolving 6 in the mixture solution of THF and water with different fractions. When water fraction was <85%, the emission intensity maintained at a low level. However, when water fraction exceeded 85%, the emission intensity increased significantly since the restriction of intramolecular motion. Moreover, this TB-AIEgen 6 exhibited interesting blue luminescence in solid state, making it suitable for OLEDs and live animal imaging through structural modification.

Discussions

In conclusion, we have established the organocatalytic asymmetric synthesis of Tröger’s bases. Under the catalysis of chiral phosphoric acid, the aminalization of tetrahydrodibenzodiazocines with aromatic aldehydes readily takes place, affording a wide range of rigid V-shaped TB products in good yields with excellent enantioselectivities (55 examples, up to 96% yield, up to >99% ee). More importantly, the protocol has been successfully applied to the preparation of more sophisticated three-dimensional architectures, i.e., bis- and tri-TBs. Detailed mechanistic investigations and DFT calculations illustrate the stepwise reaction pathway and enantio-control via hydrogen-bonding. The preparation of TB-polymers and TB-AIEgen demonstrates the potential for widespread applications, especially in the fields of materials science. Further investigation along this line is ongoing in our laboratory and will be reported in due course.

Methods

General procedure for the enantioselective synthesis of 3

Tetrahydrodibenzodiazocine 1 (0.1 mmol), 3 Å MS (100 mg) and CPA (C5 or ent-C5) (0.005 mmol, 4.2 mg) were dissolved in CHCl3 (1 mL), aldehyde 2 (0.12 mmol) was then added in 5 min. The reaction was stirred at - 40 °C temperature until the start materials were completely consumed (detected by TLC). The solvent was removed in vacuo and the crude product was separated by flash column chromatography on silica gel to afford 3 or ent-3.

General procedure for the enantioselective synthesis of 5

Tetrahydrodibenzodiazocine 1 (0.24 mmol), 3 Å MS (100 mg) and CPA (ent-C5) (0.005 mmol, 4.2 mg) were dissolved in CHCl3 (1 mL), aldehyde 4 (0.1 mmol) was then added in 5 min. The reaction was stirred at - 40 °C temperature until the start materials were completely consumed (detected by TLC). The solvent was removed in vacuo and the crude product was separated by flash column chromatography on silica gel to afford 5.

Data availability

The authors declare that the data relating to the characterization of products and experimental protocols are available within the article and its Supplementary Information. The X-ray crystallographic coordinate for structure 3z reported in this study has been deposited at the Cambridge Crystallographic Data Centre (CCDC), under deposition number 2379081. These data can be obtained free of charge from The Cambridge Crystallographic Data Centre via www.ccdc.cam.ac.uk/data_request/cif. The DFT data generated in this study are provided in the Supplementary Information/Source Data file. All data are available from the corresponding author upon request.

References

Lehn, J. M. Nitrogen inversion. Fortschr. Chem. Forsch. 15, 311–377 (1970).

Rauk, A., Allen, L. C. & Mislow, K. Pyramidal Inversion. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 9, 400–414 (1970).

Köhler, V. & Zaitseva, S. Pyramidal stereogenic nitrogen centers (SNCs). Synthesis 57, 1237−1254 (2024).

Huang, S. et al. Organocatalytic enantioselective construction of chiral azepine skeleton bearing multiple-stereogenic elements. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 60, 21486–21493 (2021).

Walsh, M. P., Phelps, J. M., Lennon, M. E., Yufit, D. S. & Kitching, M. O. Enantioselective synthesis of ammonium cations. Nature 597, 70–76 (2021).

Yu, T. et al. Immobilizing stereogenic nitrogen center in doubly fused triarylamines through palladium-catalyzed asymmetric C–H activation/seven-membered-ring formation. ACS Catal. 13, 9688–9694 (2023).

Zaitseva, S., Prescimone, A. & Köhler, V. Enantioselective allylation of stereogenic nitrogen centers. Org. Lett. 25, 1649–1654 (2023).

Valík, M., Strongin, R. M. & Král, V. Tröger’s base derivatives—new life for old compounds. Supramol. Chem. 17, 347–367 (2005).

Dolenský, B., Elguero, J., Král, V., Pardo, C. & Valík, M. Current Tröger’s base chemistry. Adv. Heterocycl. Chem. 93, 1–56 (2007).

Sergeyev, S. Recent developments in synthetic chemistry, chiral separations, and applications of Tröger’s base analogues. Helv. Chim. Acta 92, 415–444 (2009).

Dolenský, B., Havlík, M. & Král, V. Oligo Tröger’s bases—new molecular scaffolds. Chem. Soc. Rev. 41, 3839 (2012).

Tröger, J. Ueber einige mittelst nascirenden Formaldehydes entstehende Basen. J. Prakt. Chem. 36, 225–245 (1887).

Spielman, M. A. The structure of Troeger’s base. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 57, 583–585 (1935).

Prelog, V. & Wieland, P. Über die spaltung der tröger’schen base in optische antipoden, ein beitrag zur stereochemie des dreiwertigen stickstoffs. Helv. Chim. Acta 27, 1127–1134 (1944).

Hansson, A. P., Norrby, P.-O. & Wärnmark, K. A bis(crown-ether) analogue of Tröger’s base: recognition of achiral and chiral primary bisammonium salts. Tetrahedron Lett. 39, 4565–4568 (1998).

Goswami, S., Ghosh, K. & Dasgupta, S. Troger’s Base molecular scaffolds in dicarboxylic acid recognition. J. Org. Chem. 65, 1907–1914 (2000).

Kejík, Z. et al. Specific ligands based on Tröger’s base derivatives for the recognition of glycosaminoglycans. Dyes Pigments 134, 212–218 (2016).

Baldeyrou, B. et al. Synthesis and DNA interaction of a mixed proflavine–phenanthroline Tröger base. Eur. J. Med. Chem. 37, 315–322 (2002).

Veale, E. B. & Gunnlaugsson, T. Synthesis, photophysical, and dna binding studies of fluorescent Tröger’s base derived 4-amino-1,8-naphthalimide supramolecular clefts. J. Org. Chem. 75, 5513–5525 (2010).

Chen, Y. et al. Centered chiral self-sorting and supramolecular helix of Troger’s base-based dimeric macrocycles in crystalline state. Front. Chem. 7, 383 (2019).

Feng, H. et al. Chiral selection of Tröger’s base-based macrocycles with different ethylene glycol chains length in crystallization. Chin. Chem. Lett. 34, 108038 (2023).

Shi, C. et al. Tröger’s base-embedded macrocycles with chirality. Chem. Commun. 61, 2450–2467 (2025).

Meckler, S. M. et al. Thermally rearranged polymer membranes containing tröger’s base units have exceptional performance for air separations. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 57, 4912–4916 (2018).

Braukyla, T. et al. Inexpensive hole-transporting materials derived from Tröger’s base afford efficient and stable perovskite solar cells. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 58, 11266–11272 (2019).

Medina Rivero, S. et al. V-Shaped tröger oligothiophenes boost triplet formation by CT mediation and symmetry breaking. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 145, 27295–27306 (2023).

Harmata, M. & Kahraman, M. Congeners of Troeger’s base as chiral ligands. Tetrahedron.: Asymmetry 11, 2875–2879 (2000).

Shen, Y. M., Zhao, M. X., Xu, J. & Shi, Y. An amine-promoted aziridination of chalcones. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 45, 8005–8008 (2006).

Johnson, R. A., Gorman, R. R., Wnuk, R. J., Crittenden, N. J. & Aiken, J. W. Troeger’s base. An alternate synthesis and a structural analog with thromboxane A2 synthetase inhibitory activity. J. Med. Chem. 36, 3202–3206 (1993).

Manda, B. R., Alla, M., Ganji, R. J. & Addlagatta, A. Discovery of Tröger’s base analogues as selective inhibitors against human breast cancer cell line: design, synthesis and cytotoxic evaluation. Eur. J. Med. Chem. 86, 39–47 (2014).

Kaplánek, R. et al. Synthesis and biological activity evaluation of hydrazone derivatives based on a Tröger’s base skeleton. Bioorgan. Med. Chem. 23, 1651–1659 (2015).

Hamada, Y. & Mukai, S. Synthesis of ethano-Tröger’s base, configurationally stable substitute of Tröger’s base. Tetrahedron Asymmetry 7, 2671−2674 (1996).

Faroughi, M., Try, A. C., Klepetko, J. & Turner, P. Changing the shape of Tröger’s base. Tetrahedron Lett. 48, 6548–6551 (2007).

Michon, C., Sharma, A., Bernardinelli, G., Francotte, E. & Lacour, J. Stereoselective synthesis of configurationally stable functionalized ethano-bridged Tröger bases. Chem. Commun. 46, 2206 (2010).

Sharma, A., Guénée, L., Naubron, J. V. & Lacour, J. One-step catalytic asymmetric synthesis of configurationally stable Tröger bases. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 50, 3677–3680 (2011).

Sharma, A., Besnard, C., Guénée, L. & Lacour, J. Asymmetric synthesis of ethano-Tröger bases using CuTC-catalyzed diazo decomposition reactions. Org. Biomol. Chem. 10, 966–969 (2012).

Pujari, S. A., Guénée, L. & Lacour, J. Efficient synthesis of imino-methano tröger bases by nitrene insertions into C–N bond. Org. Lett. 15, 3930−3 (2013).

Bosmani, A., Guarnieri-Ibáñez, A., Goudedranche, S., Besnard, C. & Lacour, J. Polycyclic indoline-benzodiazepines through electrophilic additions of α-imino carbenes to Tröger bases. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 57, 7151–7155 (2018).

Ge, L., Chiou, M.-F., Li, Y. & Bao, H. Radical azidation as a means of constructing C(sp3)-N3 bonds. Green. Synth. Catal. 1, 86–120 (2020).

Saleh, N. et al. Access to chiral rigid hemicyanine fluorophores from Tröger bases and α-imino carbenes. Org. Lett. 22, 7599–7603 (2020).

Saleh, N., Besnard, C. & Lacour, J. Concave P-stereogenic phosphorodiamidite ligands for enantioselective Rh(I) catalysis. Org. Lett. 26, 2202–2206 (2024).

Rúnarsson, ÖV., Artacho, J. & Wärnmark, K. The 125th anniversary of the Tröger’s base molecule: synthesis and applications of Tröger’s base analogues. Eur. J. Org. Chem. 2012, 7015–7041 (2012).

Sergeyev, S. & Diederich, F. Semipreparative enantioseparation of Tröger base derivatives by HPLC. Chirality 18, 707–712 (2006).

Kiehne, U. et al. Synthesis, resolution, and absolute configuration of difunctionalized Tröger’s base derivatives. Chem. Eur. J. 14, 4246–4255 (2008).

Benkhäuser-Schunk, C. et al. Synthesis, chiral resolution, and absolute configuration of functionalized tröger’s base derivatives: part II. ChemPlusChem 77, 396–403 (2012).

Lützen, A. et al. Synthesis, chiral resolution, and absolute configuration of functionalized tröger’s base derivatives: part III. Synthesis 47, 3118–3132 (2015).

Wilen, S. H., Qi, J. Z. & Williard, P. G. Resolution, asymmetric transformation, and configuration of Troeger’s base. Application of Troeger’s base as a chiral solvating agent. J. Org. Chem. 56, 485–487 (1991).

Jameson, D. L. et al. Application of crystallization-induced asymmetric transformation to a general, scalable method for the resolution of 2,8-disubstituted Tröger’s base derivatives. J. Org. Chem. 78, 11590–11596 (2013).

Ondrisek, P., Schwenk, R. & Cvengroš, J. Synthesis of enantiomerically pure Tröger’s base derivatives via chiral disulfoxides. Chem. Commun. 50, 9168 (2014).

Řezanka, P. et al. Enantioseparation of Tröger’s base derivatives by capillary electrophoresis using cyclodextrins as chiral selectors. Chirality 25, 379–383 (2013).

Řezanka, P., Sýkora, D., Novotný, M., Havlík, M. & Král, V. Nonaqueous capillary electrophoretic enantioseparation of water insoluble tröger’s base derivatives using β-cyclodextrin as chiral selector. Chirality 25, 810–813 (2013).

Maitra, U. & Bag, B. G. First asymmetric synthesis of the Troger’s base unit on a chiral template. J. Org. Chem. 57, 6979–6981 (1992).

Lauber, A., Zelenay, B. & Cvengroš, J. Asymmetric synthesis of N-stereogenic molecules: diastereoselective double aza-Michael reaction. Chem. Commun. 50, 1195–1197 (2014).

Kohrt, S., Santschi, N. & Cvengroš, J. Accessing N-Stereogenicity through a double Aza-Michael reaction: mechanistic insights. Chem. Eur. J. 22, 390–403 (2015).

Pujari, S. A., Besnard, C., Bürgi, T. & Lacour, J. A mild and efficient ch2-extrusion reaction for the enantiospecific synthesis of highly configurationally stable Tröger bases. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 54, 7520–7523 (2015).

Kamiyama, T., Özer, M. S., Otth, E., Deska, J. & Cvengroš, J. Modular synthesis of optically active Tröger’s base analogues. ChemPlusChem 78, 1510–1516 (2013).

Yuan, R. et al. The first direct synthesis of chiral Tröger’s bases catalyzed by chiral glucose-containing pyridinium ionic liquids. Chem. Eng. J. 316, 1026–1034 (2017).

Ma, C., Sun, Y., Yang, J., Guo, H. & Zhang, J. Catalytic asymmetric synthesis of Tröger’s base analogues with nitrogen stereocenter. ACS Cent. Sci. 9, 64–71 (2023).

Rippel, R., Ferreira, L. M. & Branco, P. S. Progress on the synthesis and applications of aminals: scaffolds for molecular diversity. Synth.-Stuttg. 56, 2933–2954 (2024).

Cheng, X., Vellalath, S., Goddard, R. & List, B. Direct catalytic asymmetric synthesis of cyclic aminals from aldehydes. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 130, 15786–15787 (2008).

Rueping, M., Antonchick, A. P., Sugiono, E. & Grenader, K. Asymmetric brønsted acid catalysis: catalytic enantioselective synthesis of highly biologically active dihydroquinazolinones. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 48, 908–910 (2009).

Guan, C.-Y. et al. Catalytic asymmetric synthesis of planar-chiral dianthranilides via (Dynamic) kinetic resolution. Nat. Commun. 15, 4580 (2024).

Miao, Y.-H. et al. Catalytic asymmetric dearomative azo-Diels–Alder reaction of 2-vinlyindoles. Chin. Chem. Lett. 35, 108830 (2024).

Fu, Y.-D. et al. Azocarboxamide-enabled enantioselective regiodivergent unsymmetrical 1,2-diaminations. Nat. Commun. 15, 10225 (2024).

Gao, X. et al. Catalytic asymmetric dearomatization of phenols via divergent intermolecular (3 + 2) and alkylation reactions. Nat. Commun. 14, 5189 (2023).

Gao, H. J. et al. Diversity-oriented catalytic asymmetric dearomatization of indoles with o-quinone diimides. Adv. Sci. 10, 2305101 (2023).

Han, T. J., Zhang, Z. X., Wang, M. C., Xu, L. P. & Mei, G. J. The rational design and atroposelective synthesis of axially chiral C2-arylpyrrole-derived amino alcohols. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 61, e202207517 (2022).

Periasamy, M., Suresh, S. & Satishkumar, S. Synthesis of new derivatives from a Tröger base via exchange of the methano bridge with carbonyl compounds. Tetrahedron. Asymmetry 23, 108–116 (2012).

Musengimana, E. & Fatakanwa, C. Synthesis and NMR study of N-heterocyclic carbenes (NHC) precursors derived from Tröger’s base. Orient. J. Chem. 29, 1489–1496 (2013).

Greenberg, A., Molinaro, N. & Lang, M. Structure and dynamics of Troeger’s base and simple derivatives in acidic media. J. Org. Chem. 49, 1127–1130 (1984).

Trapp, O. et al. Probing the stereointegrity of Tröger’s base—A dynamic electrokinetic chromatographic study. Chem. Eur. J. 8, 3629 (2002).

Révész, Á, Schröder, D., Rokob, T. A., Havlík, M. & Dolenský, B. In-flight epimerization of a bis-Tröger base. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 50, 2401–2404 (2011).

Antonangelo, A. R. et al. Tröger’s base network polymers of intrinsic microporosity Tröger’s base network polymers of intrinsic microporosity (TB-PIMS) with tunable pore size for heterogeneous catalysis. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 144, 15581–15594 (2022).

Tong, S., Limouni, A., Wang, Q., Wang, M. X. & Zhu, J. Catalytic enantioselective double carbopalladation/C−H functionalization with statistical amplification of product enantiopurity: a convertible linker approach. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 56, 14192–14196 (2017).

Čorić, I., Vellalath, S. & List, B. Catalytic asymmetric transacetalization. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 132, 8536–8537 (2010).

Kim, J. H., Čorić, I., Palumbo, C. & List, B. Resolution of diols via catalytic asymmetric acetalization. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 137, 1778–1781 (2015).

Zhao, Y. & Truhlar, D. G. The M06 suite of density functionals for main group thermochemistry, thermochemical kinetics, noncovalent interactions, excited states, and transition elements: two new functionals and systematic testing of four M06-class functionals and 12 other functionals. Theor. Chem. Acc. 120, 215–241 (2008).

Zhao, Y. & Truhlar, D. G. Exploring the limit of accuracy of the global hybrid meta density functional for main-group thermochemistry, kinetics, and noncovalent interactions. J. Chem. Theory Comput. 4, 1849–1868 (2008).

Zhao, Y. & Truhlar, D. G. Density functionals with broad applicability in chemistry. Acc. Chem. Res. 41, 157–167 (2008).

Barone, V. & Cossi, M. Quantum calculation of molecular energies and energy gradients in solution by a conductor solvent model. J. Phys. Chem. A 102, 1995–2001 (1998).

Mennucci, B. & Tomasi, J. Continuum solvation models: A new approach to the problem of solute’s charge distribution and cavity boundaries. J. Chem. Phys. 106, 5151–5158 (1997).

Petersson, G. A. et al. A complete basis set model chemistry. I. The total energies of closed-shell atoms and hydrides of the first-row elements. J. Chem. Phys. 89, 2193–2218 (1988).

Hariharan, P. C. & Pople, J. A. Accuracy of AHn equilibrium geometries by single determinant molecular orbital theory. Mol. Phys. 27, 209–214 (1974).

Ess, D. H. & Houk, K. N. Theory of 1,3-dipolar cycloadditions: distortion/interaction and frontier molecular orbital models. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 130, 10187–10198 (2008).

Sader, C. A. & Houk, K. N. Distortion/ interaction analysis of the reactivities and selectivities of halo- and methoxy-substituted carbenes with alkenes. Arkivoc iii, 170–183 (2014).

Bickelhaupt, F. M. & Houk, K. N. Analyzing reaction rates with the distortion/ interaction-activation strain model. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 56, 10070–10086 (2017).

Bader, R. F. W. A quantum theory of molecular structure and its applications. Chem. Rev. 91, 893–928 (1991).

Bader, R. F. W. Atoms in molecules. Acc. Chem. Res. 18, 9–15 (1985).

Luo, J. et al. Aggregation-induced emission of 1-methyl-1,2,3,4,5-pentaphenylsilole. Chem. Commun. 21, 1740-1741 (2001).

Li, H. et al. Reverse thinking of the aggregation-induced emission principle: amplifying molecular motions to boost photothermal efficiency of nanofibers**. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 59, 20371–20375 (2020).

Liu, B. & Tang, B. Z. Aggregation-induced emission: more Is Different. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 59, 9788–9789 (2020).

Acknowledgements

Financial supports from National Natural Science Foundation of China (22371265 and 22208302), Natural Science Foundation of Henan Province (232301420047 and 252300421039) and the project of State Key Laboratory of Green Pesticide, Guizhou Medical University (GPLKF202507) are gratefully acknowledged.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Y.-W.L., N.-N.M., J.-X.W., X.X. and T.-J.H. performed and analyzed the experiments. H.Z. and D.W. performed the DFT calculations. G.-J.M. conceived and designed the project. G.-J.M. overall supervised the project. All authors prepared this manuscript.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Peer review

Peer review information

Nature Communications thanks Jie Han and the other anonymous reviewer(s) for their contribution to the peer review of this work. A peer review file is available.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Li, YW., Mo, NN., Zhang, H. et al. Organocatalytic asymmetric synthesis of Tröger’s bases. Nat Commun 16, 6383 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-025-61772-4

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-025-61772-4