Abstract

Thermochromic smart windows offer an efficient solution to reduce building energy consumption by regulating solar radiation without external energy input. However, conventional thermochromic windows often struggle to achieve high luminous transmittance (>70%), strong solar modulation, and an optimal transition temperature (30–40 °C) simultaneously. Here, we present a hydrated ionic polymer thermochromic smart window, which transitions between transparent and blue states through temperature-induced hydration and dehydration. Notably, the smart windows exhibit significant solar modulation (ΔTsol = 30.5%) and high luminous transmittance (Tlum = 87.7%), with an adjustable transition temperature range from 25 °C to 42 °C. Additionally, no significant performance degradation was observed after 200 heating-cooling cycles and 120 days under high-humidity conditions. Field tests showed that the smart windows can reduce indoor temperatures by up to 10 °C compared to clear windows. Simulations indicate a most probable energy-saving efficiency of 11.4% compared to clear windows, with further improvements up to 17.7% when combined with Low-E glass in warm climates. This work delivers a high-performance thermochromic smart window and offers a promising strategy for improving building energy efficiency and promoting global sustainability.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Extreme heatwave events now exceed 20 days per year and continue to increase by 2.1 days per decade1, posing serious threats to human life2 and sustainable development3. Increased energy is required to maintain comfortable indoor thermal environments, with over 20% of global energy consumption attributed to heating, ventilation, and air conditioning systems in buildings4,5,6. Notably, windows account for over 60% of energy losses in these processes due to their high solar transmittance7,8, with the rising window-to-wall ratio in modern architecture further amplifying these losses9. Additionally, windows play a critical role in providing natural lighting and outdoor views10,11. Smart windows have therefore been proposed to optimize the solar heat and natural light utilization. Thermochromic smart windows, which can automatically regulate solar radiation in response to temperature variations without external energy input, have been demonstrated as a competitive solution because of their zero-energy input, low cost, simple configuration, and large-area availability12,13.

Ideal thermochromic smart windows should offer high luminous transmission (Tlum > 70%14) and strong solar energy modulation (ΔTsol) to effectively regulate solar heat while maintain clear views15. Most importantly, a suitable transition temperature (τc) of around 30 to 40 °C is crucial to ensure the thermal activation under ambient conditions16. Conventional thermochromic smart windows have mainly focused on vanadium dioxide (VO2), which shows infrared transmittance contrast due to a metal-insulator transition at approximately 68 °C17. Although strategies such as element doping, defect engineering, and grain size control have been employed to lower the transition temperature, these approaches often result in weaker spectral modulation or reduced luminous transmittance18. Hydrogels demonstrate strong optical contrast through changes in scattering states caused by a reversible hydrophilic/hydrophobic phase transition at around 30.4 °C19. However, high haze and negligible luminous transmittance of hydrogels in the hot state limit their applications20.

Many transition metal complexes exhibit significant optical contrast between low and high temperatures, demonstrating potential for application in thermochromic smart windows21. A range of thermochromic complex materials has been proposed, including those based on ligand exchange22 and solid-state phase transition materials23,24,25, often encapsulated in polymers. However, the phase separation and micron-scale voids between polar thermochromic materials and non-polar polymer matrices can result in scattering losses22,26, thereby increasing haze and impairing visibility. Additionally, due to the presence of H2O or O2 in the air, complexes are prone to dissolution and leakage, posing challenges to stability27,28. The fundamental mechanism of the optical property changes in transition metal ions lies in the alteration of coordination configurations, particularly the transitions between tetrahedral or square-planar and octahedral coordination29. Recent studies have shown that similar coordination changes can occur during the adsorption and desorption of water molecules30,31,32. Therefore, leveraging reversible hydration and dehydration processes to achieve thermochromism represents a highly promising strategy for developing smart windows with enhanced stability and superior optical performance.

Herein, we propose a simple, uniform hydrated ionic polymer (HIP), [(C2H5)2NH2]2NiCl4@PVP, for thermochromic smart windows. As shown in Fig. 1a, upon heating, water dissociates from HIP, allowing Ni2+ to coordinate with Cl−, forming a blue tetrahedral configuration. Upon cooling, H2O is reabsorbed, coordinating with Ni2+, forming a transparent octahedral configuration. HIP thermochromic film demonstrates an impressive ΔTsol of 30.5% and a high Tlum of 87.7%. The τc can be customized between 25 °C and 42 °C by controlling humidity, making it easily activated in hot climates for solar modulation. Importantly, the thermochromic transition is highly reversible, with no significant performance degradation after 200 heating-cooling cycles and 120 days of testing under high-humidity conditions. Field tests and energy calculations further show that HIP smart windows (HIPSW) can be activated by natural environmental conditions, thereby dynamically blocking solar heat and demonstrating its great potential for reducing energy consumption in buildings.

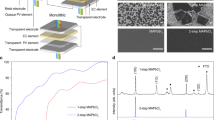

a Schematic demonstration of the thermochromic process of hydration and dehydration in HIP. b Photographs of the HIP film at different temperatures. Scale bar: 1 cm. c UV-Vis-NIR transmittance spectra of the film at 20 °C and 60 °C, together with the solar irradiance intensity (air mass 1.5 global) and photopic luminous efficiency. d Summaries of luminous transmittance and solar modulation ability of recently reported thermochromic films.

Results

Optical performance of HIP thermochromic films

The HIP thermochromic film was fabricated using the blade coating method (Supplementary Fig. 1). As shown in Fig. 1b, the sample appeared transparent at room temperature and gradually turned a deep blue as the temperature increased to 80 °C, with no significant haze throughout the process (Supplementary Fig. 2). The low haze is attributed to the formation of a non-porous, uniform structure (Supplementary Figs. 3 and 4), which causes minimal light scattering33. In addition, experimental results indicate that the heating time has minimal impact on the thermochromic performance, as shown in Supplementary Fig. 5. The color change is attributed to the reversible coordination configuration change between transparent octahedral coordination at low temperature and blue tetrahedral coordination at high temperature34. Figure 1c shows the optical transmittance of the fabricated sample across the UV-Vis-NIR wavelength range, together with the solar irradiance intensity and photopic luminous efficiency, demonstrating strong regulation in both the visible range (600–800 nm) and the near-infrared range (1300–1400 nm). The Tlum of the sample at cold and hot states is 87.2% and 31.0%, respectively, and Tsol is 81.5% and 51.4%. Consequently, the ΔTlum and ΔTsol can reach impressive values of 56.2% and 30.1%, respectively. The high ΔTlum and ΔTsol are attributed to the alignment of the high regulation performance band with the high-energy band of the solar spectrum and photopic luminous efficiency. Figure 1d compares the thermochromic performance of current thermochromic systems, showing that Tlum has reached a relatively high level compared to current reports, far exceeding the requirement of 70%, while ΔTsol reaches up to 30%, demonstrating significant improvements over other thermochromic smart windows (Supplementary Table 1).

Structural characteristics of HIP thermochromic films

As depicted above, water vapor plays an important role in the thermochromism of HIP. To provide direct evidence of water vapor involvement, two heated, colored samples were placed in air and vacuum environments. The sample exposed to air faded to a transparent state within 1.0 h, whereas the sample in a vacuum chamber remained colored, as shown in Fig. 2a. Thermogravimetric analysis (TGA) and differential scanning calorimetry (DSC) tests were also conducted (Supplementary Fig. 6), revealing significant thermal weight loss and endothermic behavior as the temperature increased, corresponding to dehydration. XRD patterns indicate that with the adsorption and desorption of H2O, significant changes in lattice spacing occur, as evidenced by a pronounced shift in the diffraction peaks (Supplementary Fig. 7).

a Photographs of HIP thermochromic films transitioning between colored and transparent states in vacuum and air over time. b FTIR spectra comparison of PVP and HIP thermochromic films at 20 °C and 60 °C. c, d Peak fitting of octahedral and tetrahedral nickel complex species. e Schematic illustrating thermochromism caused by hydration and dehydration.

Fourier transform infrared spectroscopy (FTIR) measurements were conducted to provide specific structural information. Figure 2b shows the FTIR spectra of PVP and the HIP thermochromic film during the heating and cooling processes. A strong peak at 3365.2 cm−1 is observed in HIP at 20 °C, attributed to −OH stretching vibrations23. Compared to pure PVP and [(C2H5)2NH2]2NiCl4, the N − H, −OH, and C = O stretching vibrations peaks of HIP shift to a lower frequency, suggesting the formation of hydrogen bond (Supplementary Fig. 8)35. When the HIP thermochromic film was heated to 60 °C, the −OH stretching vibrations nearly disappeared, indicating the desorption of H2O molecules. Upon cooling back to 20 °C, the peak of −OH stretching vibrations reappeared due to rehydration. The thermochromic behavior of [(C2H5)2NH2]2NiCl4 has been reported previously25,36, which is caused by a structural transformation induced by hydrogen bond reconstruction, along with a significant shift in the N − H vibration peaks (Supplementary Fig. 9). In comparison, the hydration and dehydration processes in this work require a lower transition temperature (Supplementary Fig. 10).

Absorption spectra were employed to characterize the coordination strength. NiCl2 aqueous solution and [(C2H5)2NH2]2NiCl4 were employed as model absorption species. It is well-established that Ni2+ ions coordinate with H2O to form an octahedral Ni(H2O)62+ configuration37. At 20 °C, Ni2+ ions coordinate with Cl− to form an octahedral NiCl42− configuration, while at 60 °C, a tetrahedral NiCl64− configuration is formed25. The absorption spectra of HIP at 20 °C, as shown in Fig. 2c, consist of three distinct bands centered at 1.04 eV, 1.65 eV, and 1.88 eV, corresponding to the 3A2 → 3T2, 3A2 → 1E(1D), and 3A2 → 3T1(3F) transitions of Ni2+, respectively38. The absorption spectra of NiCl2 aqueous solution exhibit very similar patterns. However, a noticeable red shift in the peaks of [(C2H5)2NH2]2NiCl4 at 20 °C indicates weaker coordination strength. The absorption spectra of HIP at 60 °C, as shown in Fig. 2d, consist of four bands centered at 0.952 eV, 1.75 eV, 1.90 eV, and 2.04 eV, corresponding to the 3T1(3F) → 3T2, 3T1(3F) → 3A2, 3T1(3F) → 3T2(1D), and 3T1(3F) → 1E(1D) transitions of Ni2+, respectively38. Similar absorption bands were observed in the spectra of [(C2H5)2NH2]2NiCl4 at 80 °C. The crystal field strength was qualitatively plotted onto the energy level diagram to clearly present the relative strength of the crystal field (Supplementary Fig. 11). The crystal field strength of HIP at 20 °C is very similar to that of NiCl2 aqueous solution, suggesting that the Ni2+ ions in HIP are coordinated with H2O molecules to form an octahedral configuration. In contrast, the crystal field strength of [(C2H5)2NH2]2NiCl4 is lower than that of HIP due to the weaker coordination ability of Cl− ions, consistent with the spectrochemical series39. At 60 °C, the crystal field strength of HIP is nearly identical to that of [(C2H5)2NH2]2NiCl4 due to the same Cl− ion ligands. EPR testing shows that the signal intensity under dehydration is much stronger than under hydration (Supplementary Fig. 12), corresponding to the octahedral coordination of Ni (II) ions, which are non-Kramers ions (S = 1) and difficult to detect at 9.5 GHz. The dehydration state exhibits a strong signal linked to low-symmetry tetrahedral coordination. The magnetization tests show that the hydration state has a higher magnetic susceptibility compared to the dehydration state, suggesting the presence of low-spin species (distorted tetrahedral configuration) in the dehydration state (Supplementary Figs. 13 and 14). This low-symmetry tetrahedral species enhances the absorption capacity of HIP at hot states21.

As shown in Fig. 2e, these results suggest the mechanism behind the thermochromism of HIP. At low temperatures, hydration occurs, where H2O coordinates with Ni2+, forming a transparent octahedral configuration. At high temperatures, dehydration takes place, allowing Cl− to coordinate with Ni2+, forming a distorted tetrahedral configuration which exhibits strong light absorption capacity.

Transition properties of HIP thermochromic films

In practical applications, a lower transition temperature and faster transition speed are essential to ensure effective regulation of sunlight. A spectroscopic testing platform capable of controlling both temperature and humidity was constructed to monitor in situ changes in optical properties under varying humidity and temperature conditions (Supplementary Fig. 15). The thermochromic process originates from the hydration and dehydration of HIP, indicating that the relative humidity (RH) plays a crucial role in the transition. The absorbance changes over time under different RH levels indicate that the coloring process is minimally affected by humidity, with coloring completed in approximately 400 − 500 s under most conditions, as shown in Fig. 3a. However, the decoloring process is significantly influenced by humidity. The decoloring time is 554 s at 80% RH, but it dramatically increases to over 11,489 s when the RH is reduced to 20%. This suggests that under low-humidity conditions, the rate of water adsorption by HIP is slower, prolonging the hydration process. Samples with different thicknesses were also fabricated. As thickness increased, although ΔTsol significantly improved (Supplementary Fig. 16), the transition speed also decreased rapidly (Supplementary Fig. 17). Therefore, the 73.7μm film exhibited the best overall performance, featuring short transition times of approximately 347 s for coloration and 792 s for decoloration under a relative humidity of 60%. The coloration and decoloration rates under different heating rates were also investigated40,41, as shown in Supplementary Fig. 18. At a heating rate of 1.0 °C/min, the HIP film completed the coloration and decoloration processes within approximately 1500 s. However, due to the mismatch between the water molecule diffusion rate and the heating rate, a higher temperature was required to trigger the thermochromic transition. In contrast, under a slower heating and cooling rate of 0.2 °C/min, the τc stabilized more effectively and exhibited a smaller temperature hysteresis, as demonstrated in Supplementary Fig. 19. Figure 3b shows the variation in transmittance at 650 nm during the heating and cooling cycles under different humidity conditions. At a relative humidity of 80%, the τc values are 44.6 °C and 39.0 °C during heating and cooling processes, respectively. When the humidity is reduced to 20%, τc decrease significantly to 28.9 °C and 21.4 °C. This indicates that high humidity hinders the escape of water molecules, requiring higher temperatures to facilitate dehydration. This behavior can be explained by the Clausius-Clapeyron relation42, which reveals the relationship between the τc and water vapor pressure (Eqs. 1 and 2):

p0 is the reference pressure, x is the molar ratio of water absorption, R is the gas constant, and ΔH0 and ΔS0 represent the enthalpy and entropy under p0 conditions, respectively. The experimental data were fitted using the above equation, demonstrating a strong goodness-of-fit as shown in Fig. 3c. This allows for a straightforward estimation of the film’s τc based on the current relative humidity. Moreover, encapsulating HIP thermochromic films within double-layered glass, the τc can be easily customized to match the local climate by adjusting the internal humidity. It was found that reducing humidity alone is insufficient to induce coloration (Supplementary Fig. 20). Even under vacuum conditions, nearly 24 h were required to achieve slight coloration (Supplementary Fig. 21). Therefore, these results indicate that the film can achieve rapid coloration within minutes under thermal activation near room temperature, and the τc can be adjusted by controlling the humidity.

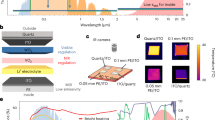

a Time-dependent absorbance during the coloring and fading processes. b The temperature-dependent thermochromic hysteresis loops of HIP film at different RH levels. c Thermodynamic model of the transition temperature, represented by the Clausius–Clapeyron diagram, illustrates the dependence of HIP’s transition temperature on relative humidity. The colored region indicates the temperature range achievable under sunlight, while the yellow and gray curves represent the temperatures at which color change begins and is fully completed, respectively. d Schematic of the experimental setup for temperature measurement under solar radiation simulation at controlled ambient temperature and humidity. e Real-time temperature evolution curves during the transition from transparent to colored states. f Photographs and thermal images at both transparent and colored states.

The role of (C2H5)2NH·HCl (DEA) in the system was investigated. As the stoichiometric ratio of DEA increased, the thermochromic behavior of the films became more pronounced, as shown in Supplementary Fig. 22, while the coordination strength gradually decreased (Supplementary Fig. 23). Variable-temperature cyclic spectroscopy revealed a slight increase in the transition temperature with higher DEA content (Supplementary Fig. 24), attributed to the enhanced hydrophilicity of the film (Supplementary Fig. 25) and its lower saturated vapor pressure (Supplementary Figs. 26 and 27). The hysteresis width decreased significantly, which can be explained by the increased diffusion rate of H2O (Supplementary Fig. 28). FTIR analysis showed that the −OH vibration peak around 3340 cm−1 gradually blue-shifted (Supplementary Fig. 29), indicating that DEA cations disrupted the crosslinking of the PVP matrix, weakening hydrogen bond strength43. This dual effect enhanced the mobility of water molecules while exposing more hydrophilic groups, thereby increasing the water absorption capacity of the film, which facilitates the rapid transition of the film back to its transparent state as the temperature decreases. It is noteworthy that after several heating and cooling cycles, films with a molar ratio of less than 2 exhibited cracking, while films with a molar ratio exceeding 2 showed significant particle precipitation on the surface (Supplementary Fig. 30). Therefore, a molar ratio of 2 was ultimately selected for the fabrication of the thermochromic film.

Ensuring that the thermochromic film can be activated by natural temperature and sunlight is essential for practical applications. A solar simulation system was constructed, as shown in Fig. 3d, where a solar simulator provides 1000 W/m2 of solar irradiance. The environment was maintained at 32 °C and 60% RH using a controller. Thermocouples and thermal imaging were employed to monitor the surface temperature and the temperature at the solar-exposed point, respectively. Figure 3e presents the temperature rise curves under simulated sunlight exposure. During the first 0.25 h, both the clear glass and HIP thermochromic film remained transparent, with little difference between the solar-exposed and surface temperatures. As time progressed, the thermal activation of HIP thermochromic film is clearly observable, with the surface temperature gradually increasing and the film turning blue, while the solar-exposed temperature begins to decrease. After approximately 1.0 h, the film completely turns blue, with the surface temperatures of the clear glass and HIP thermochromic film are approximately 38.1 °C and 60.8 °C, respectively, and the solar-exposed temperatures are approximately 65.7 °C and 47.3 °C, as shown in the infrared thermal images in Fig. 3f. Supplementary Movie 1 demonstrates the dynamic color change process during heating.

Outdoor performance

To evaluate the thermal insulation performance of the HIP thermochromic film, an on-site test was conducted in Harbin. A double-glazed glass was prepared, which had a HIP thermochromic film coated on the inner side of the outer layer, with the RH controlled at around 40% by adding solid CaCl2 powder, as shown in Supplementary Fig. 31, to construct the HIPSW. The optical properties of two double-glazed glass are shown in Supplementary Fig. 32. The double-glazed glass was installed on a testing chamber made of 2.5 cm thick wooden boards with thermal insulation foil on the surface, as shown in Fig. 4a. The solar radiation and RH changes during the test were recorded in Fig. 4b, with the peak sunlight irradiance reaching about 950 W/m2. Figure 4c illustrates the temperature variations in the HIPSW chamber and the clear window chamber. Before 8:00, due to the absence of direct sunlight caused by shadow, the surface temperature of both glass types and the air temperature in the chamber remained around 26.5 °C. After 8:00, direct sunlight caused the film to rapidly color, causing the surface temperature of the HIPSW to reach 54.1 °C, compared to 36.7 °C for the clear glass. The internal temperature of the HIPSW chamber was nearly 10 °C lower than that of the clear window chamber, demonstrating a significant cooling effect. After 16:00, as the chamber no longer received solar radiation, the film gradually faded, and the temperatures in both chambers became consistent again.

a Schematic of the experimental setup for temperature measurement under solar radiation simulation at controlled ambient temperature and humidity. b Solar irradiance and RH during the test period. c Real-time temperature evolution curves during the transition from transparent to colored states, with corresponding photographs and thermal images at both transparent and colored states. d Schematic of testing chamber equipped with temperature controller and power meter. e Energy consumption comparison between the HIPSW and clear window chamber over 60 mins. f Optical performance of the HIPSW thermochromic film after 200 heating and cooling cycles. g UV-Vis-NIR transmittance spectra and h Temperature-dependent transmittance at 650 nm of the HIP thermochromic film before and after 200 cycles and after 120 days.

To intuitively assess the impact of HIPSW on the energy consumption of air conditioning systems, a custom thermostatic chamber system was used. This system simulated indoor air conditioning cold air supply using semiconductor cooling chips and fans, as shown in Fig. 4d (the photographs of the system are provided in Supplementary Fig. 33). Thermocouples were used to detect the air temperature and direct solar temperature inside the chamber, with the air temperature serving as the control standard. The start and stop temperatures were set at 26 °C and 29 °C, respectively. A power meter was installed at the power source to record energy consumption data. The air temperature was well controlled within the set range (Supplementary Fig. 34). The HIPSW chamber cooled down faster than the clear window chamber, and the direct solar temperature was lower, attributed to HIPSW blocking the entry of high-energy solar radiation, making it easier to cool down. The corresponding energy consumption data is shown in Fig. 4e, where the energy consumption of the HIPSW chamber was consistently lower than that of the clear window chamber, with an overall energy-saving efficiency exceeding 30%. In summary, these results indicate that the HIPSW can effectively reduce indoor energy load by regulating solar radiation, demonstrating great application potential.

The cyclic performance and stability were investigated to ensure the long-term effectiveness of thermochromic temperature control in smart window applications. The test environment was maintained at a temperature of 20 °C and a relative humidity of 40%, with performance tested after every 10 cycles. Figure 4f shows that after 200 heating and cooling cycles, there was almost no degradation in performance, maintaining a high luminous light transmittance of 86.9% at 20 °C and a solar modulation rate of 30.0%. Additionally, after 200 cycles, the high- and low-temperature spectra remained almost identical, and even after 120 days maintained at a RH 80% and repeated testing, the film’s transmission spectra showed virtually no change, as shown in Fig. 4g. The transition characteristics also remained highly consistent, with the transition temperature fluctuating only within 2 °C around 36 °C and 30 °C, as shown in Fig. 4h. No significant changes in the surface morphology of the film were observed (Supplementary Fig. 35). In addition, the UV aging resistance of the film was evaluated, as shown in Supplementary Fig. 36. After exposure to UV radiation equivalent to 2 years of sunlight44, the average luminous transmittance decreased by only 2.2%, while the solar modulation performance remained nearly unchanged. Aging tests indicate that the HIP thermochromic film maintains stable thermochromic performance after multiple switching cycles and UV aging, ensuring reliability for practical applications.

Energy saving evaluation

To further evaluate the energy-saving performance of HIPSW, the EnergyPlus program was used to calculate the energy consumption of a 10-floor office building (Supplementary Fig. 37). The simulation details are summarized in Supplementary Table 2, and the thermal properties of the materials are listed in Supplementary Table 3. The simulation schedule is presented in Supplementary Fig. 38. The optical properties of clear glass, Low-E glass, and HIPSW are provided in Supplementary Tables 4 and 5, respectively. A total of 1623 cities worldwide were selected for analysis (Supplementary Fig. 39), comparing the energy performance of office buildings fitted with five different types of double-glazed windows, as illustrated in Supplementary Fig. 40. The results indicate that HIPSW achieves up to 21% energy savings globally, as shown in Fig. 5a. Notably, in low-latitude regions, solar film windows are more suitable than thermochromic windows, offering energy savings of up to 30%, as shown in Supplementary Fig. 41. In contrast, Low-E windows demonstrate more significant energy-saving potential in high-latitude regions, as illustrated in Supplementary Fig. 42.

a Total energy savings of HIPSW compared to clear windows. b–e Energy savings compared with clear windows under different climate conditions categorized by CDD and HDD for buildings equipped with Low-E windows, solar film windows, HIPSW, and LHIPSW. The central line in the box plot represents the median, the box shows the range from the first to the third quartile. Violin plot areas were normalized for comparison, and x-axis ranges were standardized across subplots. f Heating and cooling energy consumption in Beijing. g–h Solar irradiance, LWIR, and convective heat transfer between windows and the indoor environment under cold and hot weather conditions.

To explore the applicable climate zones for thermochromic window films, climate classification was conducted using cooling degree days (CDD) and heating degree days (HDD)45, dividing regions into hot, warm, and cold climates (Supplementary Fig. 43). As shown in Fig. 5b, Low-E windows perform well in cold climates, with a most probable energy-saving efficiency of 16.0%. Solar film windows exhibit optimal performance in hot climates, achieving a most probable energy-saving efficiency of up to 18.0%. However, as HDD increases, their energy-saving potential declines sharply, even resulting in a 2–30% increase in total energy consumption (Fig. 5c). In contrast, HIPSW demonstrates a more moderate and stable energy-saving performance across nearly all regions, with a most probable energy-saving efficiency of 11.4% (Fig. 5d). Supplementary Fig. 44 clearly demonstrates that HIPSW outperforms solar film windows in terms of energy savings, particularly in regions where it exhibits a positive energy-saving effect. When combined with Low-E glass, LHIPSW achieves even greater energy savings in warm and cold climates, reaching a most probable energy-saving efficiency of 17.7%, as shown in Fig. 5e and Supplementary Fig. 45.

To analyze the underlying mechanism by which HIPSW regulates energy consumption, Beijing was selected as a representative city with substantial heating and cooling loads. As shown in Fig. 5f, Low-E windows effectively reduce heating energy consumption, with a slight increase in cooling load, resulting in modest overall energy savings. Although solar film windows significantly reduce cooling load, they also substantially increase heating consumption, leading to a net rise in total energy use. In contrast, HIPSW reduces cooling energy consumption while having minimal impact on heating load, thus maintaining a net positive energy-saving performance. LHIPSW, which combines HIPSW with Low-E glass, further reduces both heating and cooling loads, resulting in enhanced energy savings. To further investigate the energy-saving mechanisms of different window types, solar irradiance, long-wave infrared radiation (LWIR), and convective heat transfer through the window were extracted for analysis. As shown in Fig. 5g, under cold weather conditions, Low-E windows and LHIPSW reduce LWIR exchange, effectively enhancing thermal insulation. This leads to an increase in window surface temperature (Supplementary Fig. 46) and a reduction in convective heat loss. Meanwhile, HIPSW and LHIPSW maintain relatively high solar transmittance, contributing to increased solar heat gains and thereby reducing heating load in winter. Under hot weather conditions, as illustrated in Fig. 5h, both HIPSW and LHIPSW significantly suppress solar heat gain, resulting in reduced cooling load.

In addition, a large-area HIP thermochromic film (30 cm × 40 cm) was successfully fabricated, exhibiting similarly remarkable thermochromic performance (Supplementary Fig. 47). HIPSW has also been demonstrated to be a cost-effective solution, with its economic performance summarized in Supplementary Table 6. Cytotoxicity tests46,47,48 further confirmed the biosafety of the HIP (Supplementary Fig. 48). These results further highlight its strong potential for large-scale application in energy-efficient building design.

Discussion

This work demonstrates a thermochromic smart window utilizing a hydrated ionic polymer, [(C2H5)2NH2]2NiCl4@PVP, designed to regulate solar radiation and improve building energy efficiency. The thermochromic behavior of HIP is driven by the reversible hydration and dehydration of Ni2+ ions, which switch between octahedral and tetrahedral coordination structures, alternating between a transparent state at low temperatures and a blue state at high temperatures. HIP thermochromic films exhibit an impressive ΔTsol of 30.5% and a high Tlum of 87.7%, with a τc between 25 °C and 42 °C by controlling humidity as well as short transition times of approximately 347 s for coloration and 792 s for decoloration, respectively. These characteristics allow HIPSW to be easily activated by natural environment conditions, as demonstrated in field tests that dynamically block solar heat. Additionally, the film maintained stable thermochromic performance even after 200 heating-cooling cycles and 120 days of testing under high-humidity conditions, ensuring long-term durability. Field tests showed that HIPSW can reduce solar-exposed temperatures by approximately 10 °C, while the simulations indicated a most probable energy-saving efficiency of 11.4% for HIPSW, which increased to 17.7% when combined with Low-E glass. Overall, HIPSW offers a promising, cost-effective, and durable solution for energy-efficient building designs, particularly in regions with high solar radiation, contributing to significant energy savings and promoting sustainable development.

Methods

Materials

(C2H5)2NH·HCl, NiCl2·6H2O, and polyvinyl pyrrolidone (PVP, K29 − 32) were purchased from Aladdin reagent Co., Ltd. Glass substrates (3 cm × 3 cm) were supplied by Luoyang Guluo Glass Co., Ltd. Deionized (DI) water (18.2 MΩ cm) was prepared in the laboratory. All reagents were used without further purification.

Fabrication of thermochromic films

The sample was prepared by first dissolving 5.0 g of PVP in 50 mL of DI water, followed by stirring for 24 h to obtain a PVP aqueous solution. Next, 2.2 g of (C2H5)2NH·HCl and 2.4 g of NiCl2·6H2O were added to the solution and stirred for an additional 2 h until a clear, green precursor solution was formed. Finally, the precursor was coated onto the glass substrates using the blade coating method and dried at 60 °C on a hot stage for 2 h to obtain the HIP thermochromic film.

Characterization

The optical transmittance was measured using a UV-Vis-NIR spectrophotometer (HT2000G, Xi’an Bohui Instrument & Meter Co., Ltd, China) equipped with a custom-designed heating module, which included a heater, T-type thermocouples, and a PID temperature controller, over a wavelength range of 300–2500 nm. The luminous and solar transmittance, along with modulation, were further calculated using the following equations:

Where T(λ) represents the transmittance of the samples at wavelength λ. AM1.5(λ) is the solar irradiance spectrum for an absolute air mass of 1.5, and V(λ) is the photopic luminous efficiency of the human eye as defined by the International Commission on Illumination standard. The hysteresis loop of the sample was measured using a fiber optic spectrometer (CHS-5000/200um, Guangzhou Changhui, China) with a wavelength range of 250 nm to 1750 nm, equipped with a custom-designed heating module and a 150 mm integrating sphere detector. The τc was defined as the point where the first derivative of transmittance with respect to temperature reaches its minimum value16. The heating rate was controlled at 0.2 °C/min, with one spectrum recorded every minute. The τc measurement was conducted in a constant temperature and humidity chamber at 20 °C and 20%, 40%, 60%, 80% RH. The transition time is determined as the duration required for the normalized initial transmittance to change from 5% to 95%.

The infrared spectra of samples were obtained using an FTIR spectrophotometer (HT9G, Xi’an Bohui Instrument & Meter Co., Ltd, China) over the range of 400–4000 cm-1 during hydration and dehydration, employing the ATR mode. The desorption behavior of water molecules in HIP was analyzed through thermogravimetry and differential scanning calorimetry (HQT-4, HENVEN, China). The sample was heated from room temperature to 300 °C at a heating rate of 10 °C/min, with an airflow rate of 50 mL/min.

The vapor pressure of the film was measured using a sealed chamber equipped with RH and temperature sensors, as well as fans. First, the humidity was stabilized at 50%, and then the sample was placed into the chamber. Changes in the air RH and temperature were recorded, allowing the calculation of the vapor pressure inside the chamber.

Building energy saving simulation

The annual HVAC energy consumption of buildings was simulated using EnergyPlus (https://energyplus.net). The model used a large, 10-floor office building with dimensions of 75.0 m (L) × 35.0 m (W) × 40.0 m (H) and a window-to-wall ratio of 50%. Hourly weather data was download from http://Climate.OneBuilding.org.

Data availability

All data are available from the corresponding author upon request. Source data are provided with this paper as Source Data file. Source data are provided with this paper.

References

Johnson, N. C., Xie, S.-P., Kosaka, Y. & Li, X. Increasing occurrence of cold and warm extremes during the recent global warming slowdown. Nat. Commun. 9, 1724 (2018).

Li, L. & Zha, Y. Population exposure to extreme heat in China: frequency, intensity, duration and temporal trends. Sust. Cities Soc. 60, 102282 (2020).

Wen, J., Zhao, X.-X., Fu, Q. & Chang, C.-P. The impact of extreme weather events on green innovation: which ones bring to the most harm?. Technol. Forecast. Soc. Chang. 188, 122322 (2023).

Sheng, S.-Z. et al. Nanowire-based smart windows combining electro- and thermochromics for dynamic regulation of solar radiation. Nat. Commun. 14, 3231 (2023).

Chai, J. & Fan, J. Solar and thermal radiation-modulation materials for building applications. Adv. Energy Mater. 13, 2202932 (2023).

Sui, C. et al. Dynamic electrochromism for all-season radiative thermoregulation. Nat. Sustain. 6, 428–437 (2023).

Jelle, B. P. et al. Fenestration of today and tomorrow: a state-of-the-art review and future research opportunities. Sol. Energy Mater. Sol. Cells 96, 1–28 (2012).

Wang, S. et al. Thermochromic smart windows with highly regulated radiative cooling and solar transmission. Nano Energy 89, 106440 (2021).

Paulos, J. & Berardi, U. Optimizing the thermal performance of window frames through aerogel-enhancements. Appl. Energy 266, 114776 (2020).

Huang, G. et al. Radiative cooling and indoor light management enabled by a transparent and self-cleaning polymer-based metamaterial. Nat. Commun. 15, 3798 (2024).

Zhang, Y. et al. Perovskite thermochromic smart window: advanced optical properties and low transition temperature. Appl. Energy 254, 113690 (2019).

Zhang, Z. et al. Thermochromic energy efficient windows: fundamentals, recent advances, and perspectives. Chem. Rev. 123, 7025–7080 (2023).

Xu, G. et al. Thermochromic hydrogels with dynamic solar modulation and regulatable critical response temperature for energy-saving smart windows. Adv. Funct. Mater. 32, 2109597 (2022).

Taylor, A. et al. A bioinspired solution for spectrally selective thermochromic VO2 coated intelligent glazing. Opt. Express 21, A750 (2013).

Ke, Y. et al. Emerging thermal-responsive materials and integrated techniques targeting the energy-efficient smart window application. Adv. Funct. Mater. 28, 1800113 (2018).

Liu, S. et al. Organic Hybrid perovskite (MAPbI3−xClx) for thermochromic smart window with strong optical regulation ability, low transition temperature, and narrow hysteresis width. Adv. Funct. Mater. 31, 2010426 (2021).

Cui, Y. et al. Thermochromic VO2 for Energy-Efficient Smart Windows. Joule 2, 1707–1746 (2018).

Hao, Q. et al. VO2/TiN Plasmonic Thermochromic Smart Coatings for Room-Temperature Applications. Adv. Mater. 30, 1705421 (2018).

Zhou, Y. et al. Hydrogel smart windows. J. Mater. Chem. A 8, 10007–10025 (2020).

Pu, J. et al. Ammonia powered thermal-responsive smart window with spectral regulation of Cu2+ and sodium copper chlorophyllin. Energy Conv. Manag. 299, 117815 (2024).

Billeci, F. et al. Ionic Liquids–Cobalt(II) Thermochromic Complexes: How the Structure Tunability Affects “Self-Contained” Systems. ACS Sustain. Chem. Eng. 9, 4064–4075 (2021).

Chen, Y. et al. VO2/Nickel-bromine-ionic liquid composite film for thermochromic application. Sol. Energy Mater. Sol. Cells 196, 124–130 (2019).

Kahani, S. A. & Abdevali, F. Mechanochemical synthesis and characterization of a nickel(ii) complex as a reversible thermochromic nanostructure. RSC Adv. 6, 5116–5122 (2016).

Zhao, X. et al. Thermochromic composite film of VO2 nanoparticles and [(C2H5)2NH2]2NiBr4@SiO2 nanospheres for smart window applications. Chem. Eng. J. 460, 141715 (2023).

Yu, D. et al. Thermochromic Ni(II) organometallics with high optical transparency and low phase-transition temperature for energy-saving smart windows. Small 19, 2205833 (2023).

Wei, X., Yu, L., Jin, X., Wang, D. & Chen, G. Z. Solar-thermochromism of pseudocrystalline nanodroplets of ionic liquid–Ni II complexes immobilized inside translucent microporous PVDF films. Adv. Mater. 21, 776–780 (2009).

Liu, S. et al. Mask-inspired moisture-transmitting and durable thermochromic perovskite smart windows. Nat. Commun. 15, 876 (2024).

Siegler, T. D. et al. Deliquescent chromism of nickel(II) iodide thin films. Langmuir 35, 2146–2152 (2019).

Pitchaimani, J. et al. Reversible thermochromism of nickel(II) complexes and single-crystal-to-single-crystal transformation. ACS Omega 4, 13756–13761 (2019).

Wang, Z., Hou, X., Duan, N., Ren, Y. & Yan, F. Shape- and color-switchable polyurethane thermochromic actuators based on metal-containing ionic liquids. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 13, 28878–28888 (2021).

Wang, Y.-J., Shi, N., Sun, C., Sun, Y.-Q. & Zheng, S.-T. Reversible thermochromism and stable resistance switching behaviors based on a Co(III)-complex-linked polyoxoniobate. Inorg. Chem. 62, 10675–10683 (2023).

Zhou, Y. et al. Hydrochromic NiI2/(CH3)4NI derived humidity self-adaptive nano-electronic for precisely tracking gastric cancer-related volatile markers under humid condition. Chem. Eng. J. 425, 130543 (2021).

Qin, M. et al. Vapor exchange induced particles-based sponge for scalable and efficient daytime radiative cooling. Adv. Funct. Mater. 33, 2304073 (2023).

Wei, X., Yu, L., Wang, D., Jin, X. & Chen, G. Z. Thermo-solvatochromism of chloro-nickel complexes in 1-hydroxyalkyl-3-methyl-imidazolium cation based ionic liquids. Green. Chem. 10, 296–305 (2008).

Liu, M., Yan, X., Liu, H. & Yu, W. An investigation of the interaction between polyvinylpyrrolidone and metal cations. React. Funct. Polym. 44, 55–64 (2000).

Chen, C., Zhihua, Z., Yiming, Z. & Jiangyan, D. Solid-state synthesis of a thermochromic compound. J. Chem. Educ. 77, 1206 (2000).

Xia, F.-F., Zeng, D., Yi, H.-B. & Fang, C. Direct contact versus solvent-shared ion pairs in saturated NiCl2 aqueous solution: a DFT, CPMD, and EXAFS investigation. J. Phys. Chem. A 117, 8468–8476 (2013).

Zhu, Y. et al. Doping and luminescence mechanisms of broadband NIR-II emitting Zn2(1−x)Ni2xGa3Ge0.75O8 nanoparticles. J. Am. Ceram. Soc. 106, 1203–1215 (2023).

Mortensen, S. R. & Kepp, K. P. Spin propensities of octahedral complexes from density functional theory. J. Phys. Chem. A 119, 4041–4050 (2015).

Peng, H. et al. Thermochromic smart windows with broad-range customizable responsive temperature via the Hofmeister effect. J. Mater. Chem. A 11, 17848–17857 (2023).

Lin, Z., Yang, Z. & Gao, L. Engineering a polyvinyl butyral hydrogel as a thermochromic interlayer for energy-saving windows. Mater. Horiz. 11, 3127–3142 (2024).

Wheeler, L. M. et al. Switchable photovoltaic windows enabled by reversible photothermal complex dissociation from methylammonium lead iodide. Nat. Commun. 8, 1722 (2017).

Xie, D., Xu, J., Cheng, H., Wang, N. & Zhou, Q. The role played by amine and ethyl group in the reversible thermochromic process of [(C2H5)2NH2]2CuCl4 probing by FTIR and 2D-COS analysis. J. Mol. Struct. 1161, 267–272 (2018).

Xiong, L. et al. Thin lamellar films with enhanced mechanical properties for durable radiative cooling. Nat. Commun. 14, 6129 (2023).

Ciulla, G. & D’Amico, A. Building energy performance forecasting: a multiple linear regression approach. Appl. Energy 253, 113500 (2019).

Zhang, F., Huang, Y., Zhang, Y. & Lü, X. Screening and validation of nickel ion cytotoxicity biomarkers based on transcriptomic and proteomic technology. Regen. Biomater. 9, rbac073 (2022).

Zhang, Y., Huang, Y., Chen, R., Chen, S. & Lü, X. The interaction mechanism of nickel ions with L929 cells based on integrative analysis of proteomics and metabolomics data. Regen. Biomater. 9, rbac040 (2022).

Yang, K. et al. Supramolecular polymerization-induced nanoassemblies for self-augmented cascade chemotherapy and chemodynamic therapy of tumor. Angew. Chem. -Int. Ed. 60, 17570–17578 (2021).

Acknowledgements

This work was financially supported by the Joint Fund for Regional Innovation and Development of the National Natural Science Foundation of China (Grant No. U21A20143 (J.G.)) and the Fundamental Research Funds for the Central Universities of China (J.G.).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

H.W. and J.G. proposed the concept and designed the experiments. Y.L. and X.T. conducted the energy-saving simulations. J.W., T.Q., and B.Z. contributed to film fabrication and UV-Vis-NIR spectral measurements. J.W. also participated in field testing. M.W. assisted with SEM characterization. H.W., X.T., and Y.L. analyzed the data. H.W. drafted the original manuscript. C.Y. and Y.H. assisted in revising and formatting several figures. J.G., F.S., W.Z., Z.Q., and G.Z. reviewed and edited the manuscript. J.G. and W.Z. supervised the project.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Peer review

Peer review information

Nature Communications thanks Khaled Khaled and the other, anonymous, reviewer(s) for their contribution to the peer review of this work. A peer review file is available.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Source data

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Wang, H., Lu, Y., Wang, J. et al. Hydrated ionic polymer for thermochromic smart windows in buildings. Nat Commun 16, 6509 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-025-61776-0

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-025-61776-0