Abstract

Claudin 18.2 (CLDN18.2)-targeted CAR-T cell therapies have shown promising clinical efficacy in gastric cancer. However, early-phase trials have reported gastrointestinal adverse events due to on-target off-tumor recognition of CLDN18.2 in the gastric mucosa. By leveraging shared CLDN18.2 epitopes and expression in humans and mice, we establish an in vivo model that replicates the on-target off-tumor toxicity of CLDN18.2 CAR-T. Our findings confirm that this toxicity is independent of the CAR construct’s design, co-stimulatory domain, and tumor model. Additionally, we demonstrate the utility of this model in testing strategies to mitigate on-target toxicity, such as Boolean-logic AND-gate approaches. Our results offer insights into the use of mouse models that recapitulate on-target off-tumor toxicities, with the caveat that although we are often concerned that models will undercall toxicities in humans, they may also overcall the incidence and severity of toxicities, prematurely discarding promising therapeutic agents from further clinical development.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Gastroesophageal adenocarcinoma (GEA) remains one of the most lethal cancers, with 20,640 new diagnoses and 16,410 deaths reported in the US in 2022 alone1. Despite the use of anti-PD1/PD-L1 (Programmed cell death protein 1/ Programmed cell death protein ligand 1) blocking antibodies in PDL1-positive or MicroSatellite Instability-high (MSI-high) cancer cases and HER2-targeted therapies for HER2-positive patients, significant advancements in patient outcomes have been limited2,3,4. This highlights the critical need for innovative target discovery and the development of more effective therapies for this challenging disease. Chimeric antigen receptor (CAR) T cell therapy has revolutionized the treatment of lymphoid malignancies, yielding remarkable clinical outcomes and frequent long-term remissions5,6,7,8. However, trials of CAR-T cells have generally reported modest clinical efficacy to date in most solid tumors9.

Encouragingly, a recent phase I clinical trial of CLDN18.2-directed CAR-T cell therapy in gastric cancer patients demonstrated promising efficacy, with an overall response rate of 54.9% and a median progression-free survival of 5.8 months10. Claudin 18.2 (CLDN18.2) is a stomach-specific isoform of CLDN18 involved in tight cell junction formation and frequently expressed in gastrointestinal tumors11,12. This makes CLDN18.2 an attractive target for immunotherapies, particularly in gastric and pancreatic cancer. Despite its basal expression in healthy gastric mucosa, preclinical data suggest that the subcellular localization of CLDN18.2 to the apical side of stomach epithelial cells limits antigen accessibility to antibodies and CAR-T cells13,14,15. However, this hypothesis is contradicted by the observation of on-target off-tumor toxicity in patients treated with Zolbetuximab, an anti-CLDN18.2 monoclonal antibody that has recently been approved by the US FDA, and with CLDN18.2 CAR-T cell treatments. Zolbetuximab-treated patients frequently experience nausea and vomiting16,17, while recent phase I trials of anti-CLDN18.2 CAR-T cells have reported more severe, albeit manageable, gastric injuries, including hemorrhage, gastritis, and mucosal denudation10,18,19. More recently, cyclophosphamide and cetuximab (used here as a safety switch) were employed in a clinical trial to deplete tEGFR+ CLDN18.2 CAR-T cells following the onset of severe on-target, off-tumor gastric toxicity, including significant gastric mucosal damage and bleeding, in one of the treated patients20. Given these concerns, there is a critical need for models that can better characterize the toxicity of CLDN18.2-targeted therapies and guide the development of safer approaches.

Here we describe the development of a preclinical model of on-target off-tumor toxicity of CLDN18.2-directed CAR-T cells. By leveraging the shared epitope and tissue expression of CLDN18.2 between humans and mice, we established an in vivo model that replicates the gastrointestinal toxicities seen in clinical trials, including mucosal denudation and gastric injury10,18,19. Our model demonstrates that CLDN18.2 CAR-T cells cause significant on-target off-tumor toxicity in mice, independent of CAR binder, co-stimulatory domain, or tumor model, aligning with observations of gastrointestinal adverse events in early-phase clinical trials. Furthermore, we demonstrate that this model can be used to test safer CLDN18.2 CAR-T cell strategies, such as Boolean-logic AND-gated CARs. By employing the LINK CAR AND-gate technology21, we confirm that the on-target off-tumor toxicity of CLDN18.2 CAR-T cells can be mitigated while maintaining anti-tumor efficacy.

Our findings provide critical insights into balancing efficacy and safety in CLDN18.2-directed CAR-T cell therapies and pave the way for developing safer treatments for gastric cancer.

Results

Lethal on-target off-tumor toxicity of CLDN18.2 CAR-T cells in mice due to gastric mucosa damage

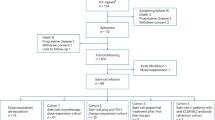

To investigate the in vivo effects of anti-CLDN18.2 CAR-T cells, we synthesized two distinct CAR constructs using single-chain variable fragments (scFv) derived from Zolbetuximab (Zolbe)22 and from the reported clinical trial CT041 (hu8e5)14,23. Both scFvs were cloned into a CD28 co-stimulated CAR backbone lentiviral vector to generate human T cells (Fig. 1A). In vitro, both CAR constructs demonstrated comparable anti-tumor efficacy against two CLDN18.2-expressing gastric cancer cell lines, GSU and NUGC-4 (Fig. 1B). The specificity for the CLDN18.2 isoform of CLDN18 was confirmed in vitro through complete epitope mapping of both binders, identifying a shared epitope centered on glutamic acid 56 of the first extracellular loop of CLDN18.2 (Fig. 1C).

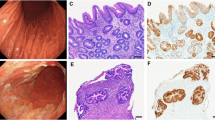

A hu8e5-2I ScFv (hu8e5) and Zolbetuximab ScFv (Zolbe) containing anti-CLDN18.2 CAR T cell design. B Real-time cytotoxicity assay of CLDN18.2 CAR T co-culture at a 1:1 E:T ratio with the gastric cancer cell lines NUGC-4 (left) or GSU (right) (mean of three independent replicates, mean ± s.d., 2-way ANOVA). C Epitope mapping of Zolbe and hu8e5 CARs. Zolbe-CD28z or hu8e5-CD28z CAR-expressing NFAT-GFP Jurkat cells were cultured for 16 h with wt Jurkat cells (WT), or Jurkat cells expressing human Claudin 18.1, Claudin18.2, or Claudin18.2 variants and analyzed by flow (normalized GFP expression compared to Claudin18.2, median of 6 technical replicates, Kruskal–Wallis test). D Experimental schematic (created in BioRender. Birocchi, F. (2025) https://BioRender.com/foaa417). NSG mice were injected subcutaneously with 2 × 106 GSU tumor cells. After 10 days mice were treated with 3 × 106 CAR-T cells (intravenously). E Flow cytometry plot showing CAR-T cell transduction efficiency. Tumor volume (F) and body weight change compare to pre-treatement (G) of GSU-bearing mice untreated (Tumor only), or treated with untransduced T cells (UTDs), Zolbe-CD28z, or hu8e5-CD28z (mean ± s.d., 2-way ANOVA) (n = 5/6 mice per group). H Absolute CAR-T cell count in the peripheral blood of treated mice at the end of the experiment (day 22) (n = 3 mice per group). I Immunohistochemistry staining of representative mice from the same experiment of D-F showing Claudin18.2 expression and T cell infiltration (hCD3) in CLDN18.2 CAR-T treated mice stomach compared to UTDs. FS = forestomach, GS = glandular stomach, LR = limiting ridge.

We then assessed the in vivo effects of Zolbe-CD28z and hu8e5-CD28z CAR-T cells in a GSU tumor model. Briefly, 2 × 106 GSU cells were injected subcutaneously in NSG mice, followed by intravenous injection of 3 × 106 CLDN18.2 CAR-T cells (Fig. 1D, E). Both CLDN18.2 CAR-T cell treatments resulted in rapid tumor regression (Fig. 1F); however, all treated mice experienced significant (>20%) body weight loss within the first three weeks (Fig. 1G). At the experiment’s endpoint (22 days post-treatment), mice exhibited high levels of circulating CAR-T cells (340–3600 CAR-T cells/μL of blood), indicating robust CAR-T cell expansion following antigen exposure (Fig. 1H).

The lung- and stomach-restricted expression patterns of CLDN18.1 and CLDN18.2 are conserved between humans and mice24 (Suppl. Fig. 1A). Moreover, murine and human CLDN18.2 share 89.4% overall sequence homology, with 100% identity in the first extracellular loop—the epitope recognized by Zolbetuximab15 (Suppl. Fig. 1B). Based on this, we hypothesized that the observed toxicity may stem from on-target, off-tumor recognition of murine CLDN18.2. We confirmed the absence of recognition of murine and human CLDN18.1 by both Zolbetuximab and hu8e5 CARs in Jurkat cells, ruling out CAR-mediated lung-directed cytotoxicity in mice (Suppl. Fig. 1C). Additionally, we demonstrated that hu8e5 binds murine and human CLDN18.2 with similar efficiency and induces comparable activation of Jurkat cells co-cultured with targets expressing varying levels of mouse or human CLDN18.2 (Suppl. Fig. 1D, E). Finally, we confirmed the selective stomach-specific expression of CLDN18.2 at the protein level in both species by performing immunohistochemistry (IHC) using a commercial anti-CLDN18.2 antibody (EPR19202) and a hu8e5-derived antibody on human and murine tissue microarrays (Suppl. Fig. 2A, B).

To evaluate the potential on-target off-tumor toxicity of CLDN18.2 CARs in treated mice, stomach tissues were analyzed by IHC for human T cell (CD3) infiltration and mouse CLDN18.2 expression. While UTD-treated animals exhibited normal CLDN18.2 expression in the stomach glandular epithelium, negligible human T cell infiltration, and preserved tissue morphology, Zolbe-CD28z and hu8e5-CD28z CAR-treated mice showed extensive CD3+ human T cell infiltration, loss of glandular epithelium, and partial or complete loss of CLDN18.2 expression (Fig. 1I). We also confirmed that most stomach-infiltrating cells were CAR+ (as indicated by mCherry expression, Suppl. Fig. 3).

These findings confirm on-target off-tumor toxicity of CLDN18.2 CAR-T cells in mice, consistent with prior reports of gastric injuries10,18 and loss of gastric mucosa (denudation) in CLDN18.2 CAR-T cell-treated patients19,20.

CLDN18.2 CAR-T cell on-target off-tumor toxicity is independent of co-stimulatory domain, CAR backbone, and tumor model

To rule out donor-dependent variability in CLDN18.2 CAR-T activity, we repeated the in vivo experiment using hu8e5-CD28z CAR-T cells from five different donors (Fig. 2A–F). Consistent with previous observations, hu8e5-CD28z CAR-T cells rapidly controlled tumor growth, followed by significant body weight loss and early mortality in mice treated with CAR-T cells from four out of five donors (Fig. 2A–F). Interestingly, mice treated with one donor (Donor 2) achieved complete tumor regression without affecting body weight, resulting in prolonged survival compared to UTD-treated mice (Fig. 2A–E). CAR-T cell counts in the peripheral blood were measured by flow cytometry at days 7, 14, and 21 post-injection. While all mice that experienced toxicity exhibited high levels of circulating CAR-T cells peaking at days 11–14, mice treated with Donor 2 CAR-T cells showed no measurable in vivo CAR-T cell expansion at any time point (Fig. 2F). These results suggest a correlation between toxicity and in vivo CAR-T cell expansion, which intriguingly did not correlate with anti-tumor response.

A Experimental schematic (created in BioRender. Birocchi, F. (2025) https://BioRender.com/foaa417): In vivo testing of hu8e5-CD28z CAR-T cells in 5 different healthy donors (B-E). NSG mice were injected subcutaneously with 2 × 10⁶ GSU tumor cells. After 10 days, mice were treated intravenously with 3 × 10⁶ hu8e5-CD28z CAR-T cells or UTDs cells (donor 1) (n = 5 mice per group). B Tumor volume (mean ± s.d., 2-way ANOVA). C Body weight change compared to pre-treatment (mean ± s.d., 2-way ANOVA). D CAR-T cell transduction efficiency (flow cytometry). E Survival plot. F Absolute count of CAR-T cells in the peripheral blood at 7, 14, and 21 days post CAR-T cell injection. G–L in vivo experiment comparing VH/VL orientation (VH-VL vs. VL-VH) and transmembrane domains (CD28 vs. CD8) in hu8e5-CD28z CAR-T cells. G Schematic of vector maps used. H Experimental schematic (same as A, created in BioRender. Birocchi, F. (2025) https://BioRender.com/foaa417) (n = 5 mice per group). I Flow cytometry plot showing CAR-T cell transduction efficiency. J Tumor volume (mean ± s.d., 2-way ANOVA). K Body weight change (mean ± s.d., 2-way ANOVA). L Survival plot. M–R In vivo comparison of hu8e5 CAR-T cells with 4-1BB vs. CD28 co-stimulatory domains. M Schematic of vector maps used. N Experimental schematic (same as A, created in BioRender. Birocchi, F. (2025) https://BioRender.com/foaa417) (n = 2 healthy donors, n = 5 mice per group/donor). O Flow cytometry plot showing CAR-T cell transduction efficiency. P Body weight change (mean ± s.d., 2-way ANOVA). Q Tumor volume (mean ± s.d., 2-way ANOVA). R Survival plot.

To better understand the on-target off-tumor toxicity, we investigated the impact of the CAR design, the co-stimulatory domain of the CAR, and the tumor model on CLDN18.2 CAR-T cell toxicity. The CAR design used in our initial experiments differs from that used in the clinical trial CT041, particularly in the use of a CD8 transmembrane domain instead of CD2810,14,18. Additionally, the orientation of the hu8e5 scFv’s heavy and light chains (VL-VH or VH-VL) used in clinical trials has not been publicly disclosed14,23. Since these factors might influence CAR expression and binding affinity to CLDN18.2, we cloned both variable chain orientations into CAR designs containing either the CD8 or CD28 transmembrane domain (Fig. 2G). Mice treated with CAR-T cells containing any of these constructs exhibited body weight loss and early mortality, excluding the role of variable chain orientation or CAR design in CLDN18.2 CAR-T on-target off-tumor toxicity (Fig. 2H–L). We next assessed whether different co-stimulatory domains (4-1BB vs. CD28) might reduce on-target off-tumor toxicity, given that other clinical trials utilize 4-1BB as a co-stimulatory domain for CLDN18.2 CAR-T cells19 and differ in their expansion kinetics compared to CD28-based CARs25 (Fig. 2M). However, no significant benefit was observed between hu8e5 CAR-T cells carrying CD28 or 4-1BB co-stimulatory domains in vivo, ruling out this hypothesis (Fig. 2N–R). Finally, to establish whether or not the findings were specific to the GSU tumor model, we evaluated the effects of hu8e5-CD28z CAR-T cells in a separate NUGC-4 tumor model in vivo. Even in this model, CAR-T cell treatment caused rapid body weight loss and lethal toxicity within 10 days of intravenous administration (Suppl. Fig. 4).

We also hypothesized that the rapid weight loss observed in CLDN18.2 CAR-T-treated mice might be due to an inability to digest solid food caused by gastric mucosa damage. We further speculated that this acute effect could be mitigated by providing a gel-based supplement diet. However, this approach also failed to prevent rapid weight loss and premature death in hu8e5-CD28z-treated mice (Suppl. Fig. 5). These data confirm that CLDN18.2 CAR-T cells cause severe on-target off-tumor toxicity in mice, independent of the co-stimulatory domain employed, CAR design, diet, and tumor model.

CLDN18.2 CAR-T cells exhibit a narrow therapeutic dose window

Despite preliminary data from ongoing clinical trials not indicating dose-limiting toxicity for CLDN18.2 CAR-T cells10,18, we explored whether the on-target off-tumor toxicity observed in mice might be dose-dependent. To test this possibility, we treated GSU-bearing mice with three doses of hu8e5-CD28z CAR-T cells: 3 × 106, 3 × 105, and 3 × 104 cells per mouse (Fig. 3A, B). In the same experiment, we also included a group of tumor-free mice treated with the highest dose (3 × 106) to evaluate the contribution of the tumor-induced expansion of CAR-T cells on the pathogenesis of the on-target off-tumor toxicity. While the 3 × 104 dose proved ineffective at controlling tumor growth, mice treated with 3 × 105 hu8e5-CD28z CAR-T cells showed no toxicity or measurable CAR-T cell expansion in the peripheral blood. However, these mice experienced a partial tumor response, with some achieving complete responses (Fig. 3C–E). Similar to tumor-bearing mice, tumor-free animals treated with 3 × 106 hu8e5-CD28z CAR-T cells showed a rapid and lethal body weight reduction, accompanied by CAR-T cell expansion in the peripheral blood that peaked at day 11 post-injection, excluding the role of tumor-induced CAR-T expansion in the onset of CAR-T cell toxicity (Fig. 3C–E). To better characterize the therapeutic window of CLDN18.2 CAR-T cells, we conducted another experiment where we treated GSU-bearing mice with 1 × 106 hu8e5-CD28z or hu8e5-41BBz CAR-T cells (an intermediate dose between the partial effective dose 3 × 105 and the toxic dose 3 × 106). Even at this dose, both hu8e5-41BBz and hu8e5-CD28z CAR-T cells caused lethal toxicity in mice, with a kinetic- similar to that observed at the highest dose (3 × 106 cells) (Suppl. Fig. 6).

A Experimental schematic (created in BioRender. Birocchi, F. (2025) https://BioRender.com/foaa417). GSU-bearing mice (2 × 10⁶ GSU tumor cells, subcutaneously) or tumor-free mice were treated intravenously with increasing doses of hu8e5-CD28z CAR-T cells (as indicated) (n = 2 healthy donors, 4 to 7 mice per group/donor). B Flow cytometry plot showing CAR-T cell transduction efficiency. C Tumor volume (mean ± s.d., 2-way ANOVA). D Body weight change compared to pre-treatment (mean ± s.d., 2-way ANOVA). E Survival plot (Log-rank Mantel-Cox test with Bonferroni correction). F Absolute count of CAR-T cells in the peripheral blood at 7, 14, and 21 days post CAR-T cell injection.

Finally, we evaluated the therapeutic efficacy of an intermediate dose (3 × 10⁵) of hu8e5-CD28z CAR-T cells in two additional tumor models: NUGC-4, which expresses approximately half the level of CLDN18.2 compared to GSU cells (low antigen density model; Suppl. Fig. 7A, B), and the AsPC-1 pancreatic cancer cell line engineered to overexpress human CLDN18.2 (high antigen density model; Suppl. Fig. 7A, D). While this dose of hu8e5-CD28z CAR-T cells had no impact on NUGC-4 tumor growth (Suppl. Fig. 7C), an anti-tumor effect comparable to that observed in the GSU model was seen in the AsPC-1 model (Suppl. Fig. 7E). These results suggest that CLDN18.2 expression levels play a critical role in determining therapeutic efficacy, particularly when CAR-T cell doses are suboptimal.

Our data indicate that CLDN18.2 CAR-T cells do have a therapeutic dose window, although narrow, where intermediate doses achieve tumor reduction without causing significant toxicity.

AND-Gate Strategy Targeting CLDN18.2 and mesothelin overcomes CAR-T cell toxicity

To date, we have shown that our in vivo model provides a valuable platform for studying and characterizing the on-target off-tumor toxicity of CLDN18.2 CAR-T cells. We hypothesized that it could also represent a useful tool for testing new therapeutic strategies aimed at reducing this toxicity. To this aim, we explored the recently published LINK21 Boolean-logic AND-gate technology to restrict CLDN18.2 CAR-T cell activity to tumor cells, while minimizing cytotoxic effects on healthy gastric mucosa. The LINK AND-gate operates by leveraging the proximal signaling molecules LAT and SLP-76 to bypass upstream CD3ζ, thereby activating T-cells in a specific manner. This approach has previously proven effective in reducing the on-target off-tumor toxicity of ROR1 CAR-T cells targeting lung tissue21. To apply the LINK technology to CLDN18.2 CAR-T cells, we selected mesothelin as the second antigen in the AND-gate. Mesothelin is reported to be overexpressed in approximately 25% of gastric cancers and GSU cells, while being absent in healthy gastric mucosa (Suppl. Fig. 8A)26. Using published patient gene expression data, we confirmed that while CLDN18.2 and Mesothelin are individually expressed in healthy stomach and lung tissues, respectively, their co-expression is restricted to gastric cancer cells (Suppl. Fig. 8B). To target mesothelin, we used M5, a binder that has shown greater potency in preclinical models compared to the commonly used SS1, although it has also demonstrated lethal on-target off-tumor toxicity in treated patients27. We cloned hu8e5-CD28(Hinge/Transmembrane)-LATΔGADS and M5-CD8(Hinge/Transmembrane)-SLP-76ΔGADS into two lentiviral vectors, which co-express LNGFR (a truncated low-affinity NGFR receptor) and truncated CD19, respectively (Suppl. Fig. 8C). This approach ensures that CAR-T cells expressing hu8e5-LAT and M5-SLP-76 do not recognize single-positive CLDN18.2 cells (healthy gastric cells) or mesothelin single-positive cells (healthy lung cells), but retain the ability to target and eliminate double-positive cells (gastric cancer cells) (Fig. 4A).

A Schematic of the LINK-based AND-gate strategy. CAR-T cell activation and killing occur only upon simultaneous recognition of both Claudin18.2 and Mesothelin on target tumor cells. B In vitro testing of the AND-gate in Jurkat NFAT-GFP reporter cells. Jurkat cells expressing one or both receptors were cultured alone or co-cultured with wild-type (wt), Mesothelin knockout (MesothelinKO), or Claudin18.2 knockout (Claudin18.2KO) GSU cells. After 16 h, cells were analyzed for GFP expression via flow cytometry. C Real-time cytotoxicity assay comparing UTDs, hu8e5-CD28z, and LINK CAR-T cells in co-culture at a 3:1 E:T ratio with the gastric cancer cell line GSU (MesoKO, Claudin18.2KO or wt) (n = 2 healthy donors. Average of three independent replicates, mean ± s.d., 2-way ANOVA). D, E In vivo comparison hu8e5-CD28z and LINK CAR-T cells (n = 2 healthy donors, 5 mice per group/donor). NSG mice were injected subcutaneously with 2 × 10⁶ GSU tumor cells. After 10 days, mice were treated intravenously with 3 × 10⁶ CAR-T cells D Body weight change compared to pre-treatment (mean ± s.d., 2-way ANOVA). E Tumor volume (mean ± s.d., 2-way ANOVA).

To assess the specificity of the LINK CAR in vitro, we leveraged NFAT-GFP reporter Jurkat cells, in which GFP expression is driven by the NFAT promoter that is selectively activated upon effective CAR signaling. We transduced Jurkat NFAT-GFP cells with lentiviral vectors encoding hu8e5-LAT, M5-SLP-76, or both and then cultured them alone or with either wild-type GSU cells (double-positive) or GSU cells with mesothelin or CLDN18.2 knocked out for 16 h. As expected, Jurkat cells expressing either hu8e5-LAT or M5-SLP-76 alone showed no CAR signaling (as measured by GFP expression) when exposed to any of these cell lines (Fig. 4B). Jurkat cells co-expressing both hu8e5-LAT and M5-SLP-76 also did not activate in the presence of single antigens but showed high levels of GFP expression when exposed to wild-type GSU cells (Fig. 4B).

Next, we tested the LINK CAR in primary T cells. Activated human T cells were transduced with hu8e5-LAT and M5-SLP-76, and double-transduced cells were isolated via magnetic separation using NGFR and CD19 microbeads (Suppl. Fig. 8D, E). In vitro, LINK CAR-T cells killed wild-type GSU cells as effectively as hu8e5-CD28z CAR-T cells, while showing no activity against mesothelin knockout or CLDN18.2 knockout GSU cells, confirming the specificity of the AND-gate (Fig. 4C). Finally, we evaluated the LINK CAR-T cells in vivo. NSG mice bearing GSU tumors were treated with 3 × 106 hu8e5-CD28z or LINK CAR-T cells. Strikingly, while hu8e5-CD28z CAR-T treated mice experienced severe body weight loss and lethal toxicity within 10 days, LINK CAR-T treated mice showed no signs of toxicity or weight loss, and were able to partially control tumor growth (Fig. 4D).

To assess the long-term anti-tumor efficacy of LINK CAR-T cells in vivo, we utilized MHC class I-deficient NSG mice (B2mKO), which offer enhanced resistance to graft-versus-host disease (GVHD) compared to standard NSG mice28, thereby enabling extended experimental timelines (Fig. 5A). Consistent with our prior results (Fig. 4D, E), mice treated with hu8e5-CD28ζ CAR-T cells exhibited rapid and pronounced weight loss, with four out of five succumbing to toxicity and one to tumor relapse (Fig. 5B–D). In contrast, LINK CAR-T-treated mice displayed no signs of toxicity or weight loss, and three out of five achieved durable tumor clearance, surviving through day 87 without recurrence or measurable adverse effects (Fig. 5B–D). Notably, the CAR-T cell expansion in peripheral blood differed significantly between the two constructs. While hu8e5-CD28ζ CAR-T cells peaked around day 10, LINK CAR-T cells showed minimal measurable expansion during the first three weeks following infusion (Fig. 5E).

A Experimental schematic (created in BioRender. Birocchi, F. (2025) https://BioRender.com/foaa417). GSU-bearing B2mKO NSG mice (2 × 10⁶ GSU tumor cells, subcutaneously) were treated intravenously with 3 × 10⁶ CAR-T cells (as indicated)(n = 5 mice per group). B Tumor volume (mean ± s.d.). C Body weight change compared to pre-treatment (mean ± s.d.). D Survival plot. E Absolute count of CAR-T cells in the peripheral blood at 7, 14, and 21 days post CAR-T cell injection. F Experimental schematic (created in BioRender. Birocchi, F. (2025) https://BioRender.com/foaa417): NSG mice bearing subcutaneous GSU tumors (2 × 10⁶ cells) were treated intravenously with CAR-T cells as indicated. Eight days post-treatment, mice were euthanized, and tumors and stomach tissues were harvested for immunohistochemistry analysis (n = 5 mice per group). G, H Quantification of human CD3⁺ cells per mm² of tissue in the stomach (G) and tumor (H) of treated mice, performed using QuPath software (Kruskal-Wallis test).

To further investigate the safety profile of LINK CAR-T cells and compare it with intermediate-dose CLDN18.2 CAR-T cells, we treated GSU-bearing NSG mice with UTDs, high-dose (3 × 106) or intermediate-dose (3 × 105) hu8e5-CD28ζ CAR-T cells, or LINK CAR-T cells (3 × 106), and collected tumors and stomachs at an early time point (day 8 post-injection) for immunohistochemistry (IHC) analysis (Fig. 5F). As anticipated, T cell infiltration in the tumor was limited at this early stage, and notably absent in the stomach of LINK CAR-T cell-treated mice (Fig. 5G, H). In contrast, high and intermediate doses of hu8e5-CD28ζ CAR-T cells led to robust and moderate T cell infiltration, respectively, in both stomach and tumor tissues, without evidence of preferential localization to either site (Fig. 5G, H). These data suggest that in our model, CLDN18.2 CAR-T cells do not exhibit selective targeting of tumor over normal gastric tissue. Therefore, the improved safety profile observed with the intermediate dose of hu8e5-CD28ζ likely reflects a mild and potentially reversible on-target, off-tumor effect in the stomach, rather than selective tumor-specific activity.

In summary, these findings validate our preclinical model as a useful platform for assessing strategies to mitigate on-target off-tumor toxicity associated with CLDN18.2 CAR-T cell therapies, while also confirming the translational potential of the hu8e5-LAT and M5-SLP-76 LINK CAR-T cell approach for the treatment of gastric cancer.

Discussion

This study demonstrates the challenge of balancing efficacy and safety in Claudin 18.2 (CLDN18.2)-directed CAR-T cell therapies, particularly in addressing on-target off-tumor toxicity in the healthy gastric mucosa. CLDN18.2-directed therapies, including Zolbetuximab, a recently approved monoclonal antibody targeting CLDN18.2 for HER2-negative gastric or gastroesophageal junction (GEJ) adenocarcinoma, represent the latest advancements in gastric cancer treatment. With over 60 ongoing clinical trials investigating anti-CLDN18.2 drugs, including 23 focused on CLDN18.2-directed CAR-T cells29, it is essential to develop reliable preclinical mouse models that can accurately replicate the efficacy as well as the potential toxicity of CLDN18.2-directed therapies.

In this study, we developed a mouse model of gastric cancer that recapitulates, although in a more aggressive fashion, the on-target off-tumor toxicity seen in the early clinical trials employing CLDN18.2-directed CAR-T cells. Through this model, we demonstrated that CLDN18.2 CAR-T cells not only target tumor cells but also recognize Claudin 18.2 in healthy gastric glandular cells, leading to the destruction of the gastric mucosa and lethal toxicity in mice. Importantly, this toxicity was consistent regardless of the binder (Zolbe or hu8e5), co-stimulatory domains (41BB or CD28), CAR design, or tumor models.

Although it is commonly believed that CLDN18.2 in the healthy gastric mucosa is buried within the tight junction complex and becomes exposed only during neoplastic transformation15,30, our data only partially supported this hypothesis. Although CLDN18.2-directed CAR-T cells demonstrated partial efficacy without measurable toxicity at an intermediate dose (3 x 105), the therapeutic window was narrow. A lower dose (3 x 104) was ineffective, while higher doses (≥ 1 x 106) caused significant toxicity. These findings align with clinical data, where patients receiving CLDN18.2-directed CAR-T cells often experience moderate to severe gastric toxicity and only short-lived anti-tumor responses10,18,19. However, it is worth noting that the toxicity experienced by the mice is much more frequent and much more severe, despite supportive dietary measures, than what has been observed in humans treated with either Zolbetuximab or in clinical trials of CLDN18.2-directed CAR-T cells.

We further demonstrated that the presence of on-target off-tumor toxicity correlated with the peripheral expansion of CAR-T cells in the blood, while its absence corresponded to a lack of measurable expansion. This association, also observed in tumor-free mice, suggests that CLDN18.2-directed CAR-T cells expand mainly after recognizing the antigen in healthy gastric mucosa, excluding tumor-dependent factors in the toxicity mechanism. Based on these findings, we speculate that CAR-T cell expansion triggers a feedback loop of antigen recognition and cytotoxicity, potentially leading to a self-amplifying cycle of CAR-T cell expansion and tissue damage, eventually leading to lethal toxicity in mice. This hypothesis, if confirmed also in the clinical setting, could inform the development of therapeutic interventions aimed at controlling CAR-T cell expansion to mitigate off-tumor toxicity.

We acknowledge that our findings contradict previous preclinical reports demonstrating the safety of anti-CLDN18.2 CAR-T cells. Some of these studies were conducted in syngeneic models, making direct comparison challenging due to differences in the T cells used (murine vs. human)31,32. Additionally, other groups have reported strong anti-tumor responses from CLDN18.2-directed human CAR-T cells in xenograft models without observing on-target off-tumor toxicity14,33. While our data align with toxicity seen in patients, we are unable to fully account for these conflicting results. Notably, we also observe an absence of on-target off-tumor toxicity in one of the five donors used (donor 2), suggesting that donor-specific factors may influence this toxicity. This variability underscores the importance of testing multiple healthy donors in CAR-T cell manufacturing, as it could lead to different outcomes in preclinical models. In addition, it should be noted that other experimental differences may justify the different results obtained by ours and other groups, including the use of CLDN18.2 artificially overexpressing tumor cell lines14,33, which may favor a preferential recognition of the antigen expressed at a higher level in the tumor compared to the stomach. Additionally, differences in mouse strains (NOG33 or BALB/c nude14 mice) and the use of lymphodepleting conditioning (cyclophosphamide14) could contribute to the discrepancies observed.

There are many examples in the literature where xenograft studies of CAR-T cells in mice have failed to predict the toxicities observed in human clinical trials. This has been true of on-target off-tumor toxicities, often attributed to the lack of endogenous expression of an identical target antigen in murine tissues34,35,36, and also of off-target toxicities such as cytokine release syndrome or immune-effector cell associated neurotoxicities (ICANs), which has been attributed to the immunodeficiency of the mice and/or the lack of cross-reactivity among cytokines that activate immune responses following T cell activation. In this study, we report an on-target toxicity that is much more severe in mice than what has been observed in humans. Given the reports of strong anti-tumor activity with the use of CLDN18.2-targeted therapies, including complete regression of pancreatic cancer19 and incidence of partial and complete responses in gastric cancer and other GI malignancies10,18, it would have been a real loss to patients had clinical development been halted based on toxicities observed in mice.

Nevertheless, our model serves as a valuable tool for developing, testing, and refining molecular strategies to mitigate on-target off-tumor toxicities. For example, our test of a Boolean-logic AND-gate approach (LINK) demonstrated potential as a safer alternative, though anti-tumor activity was slightly diminished, perhaps due to the absence of costimulation. Future studies will aim to elucidate the mechanisms underlying the reduced anti-tumor activity observed with LINK CAR-T cells and explore strategies to enhance their efficacy. These may include the use of higher-affinity binders to lower the activation threshold required for effective LINK CAR signaling.

A further potential limitation of the CLDN18.2/Mesothelin LINK CAR-T cell strategy is its restricted applicability to patients whose tumors co-express both antigens. While our data demonstrate that this antigen pair is present in a substantial subset of gastric cancers, we recognize that this requirement may constrain broader clinical use. Ongoing efforts will focus on identifying alternative antigen pairs with wider expression profiles to expand the therapeutic reach of the LINK CAR platform.

Finally, the LINK CAR approach—like other AND-gate CAR-T cell strategies—carries an inherent risk of therapeutic failure, as tumor cells may evade recognition by downregulating or losing expression of either one of the two targeted antigens.

We believe this mouse model offers a valuable platform for testing and validating future strategies to mitigate the on-target, off-tumor toxicity of CLDN18.2-directed CAR-T cell therapies. Potential approaches include IF-gate systems such as synthetic Notch (synNotch) receptors and Synthetic Intramembrane Proteolysis Receptors (SNIPRs), as well as IF-Better Gate technologies. Additionally, combination strategies—such as co-administration of proton pump inhibitors to minimize gastric toxicity—may also be explored using this model.

In summary, the findings of this study emphasize the strengths and weaknesses of mouse models to accurately replicate potential on-target off-tumor toxicities of CAR-T cell therapies; on the one hand, it is useful to leverage models that demonstrate on-target effects to an endogenous tissue due to natural expression of an identical antigen with similar distribution of expression in mice and humans. On the other hand, models may overcall the severity of a toxicity, and prematurely discard promising clinical candidates. In the case of claudin 18.2, for example, many patients with gastric cancer have had a prior gastrectomy, and thus would likely not experience on-target toxicities from claudin 18.2-directed therapies.

Methods

Study design

This study was designed to develop anti-Claudin 18.2 CAR T cells for treating gastroesophageal adenocarcinoma. To assess CAR T cell efficacy, a range of functional assays were conducted in vitro and in vivo using diverse gastric tumor cell lines. T cells were derived from anonymized human blood samples, obtained with Institutional Review Board (IRB) approval for the purchase of anonymous leukapheresis products from the MGH blood bank. The IRB at Massachusetts General Hospital classified the use of these T cells as “non-human subjects research.” All animal studies followed approved protocols from the MGH Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee (IACUC), with animals randomized before CAR T cell treatment. The maximal tumor size permitted by the MGH IACUC is a 20 mm diameter, which was not exceeded in our experiments.

Mice and cell lines

Male and female NOD-SCID-γ chain −/− (NSG) mice purchased from the Jackson laboratory were bred under pathogen-free conditions at the MGH Center for Cancer Research. Animals were maintained in rooms with 12:12 h light:dark cycles, humidity of 30–70%, and temperature of 21.1–24.5 C. All experiments were approved according to MGH Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee protocols. For experiments involving a liquid diet supplement, DietGel® 76 A (with Animal Protein) (Clear H2O) was provided alongside solid food. Each diet cup was replaced with a fresh one every 2–3 days.

GSU and NUGC-4 cells were sourced from Creative Bioarray. Jurkat cells were sourced from the American Type Culture Collection (ATCC). All cell lines were maintained under conditions as outlined by the supplier.

GSU and NUGC-4 cells were transduced with enhanced GFP (eGFP) and click beetle green (CBG) luciferase. Cell lines were then sorted for 100% transduction on a BD FACSAria II BD FACSMelody™ cell sorter. GSU mesothelin knock-out and claudin18.2 knock-out have been generated as follows. Briefly, GSU cells have been electroporated with 10ug of Cas9 mRNA and 0.3nmol of sgRNA (Synthego CRISPRevolution. Mesothelin: GGAGACAGACCAUGUCGACG. Claudin18.2: AGUUGAAUACAGCGGUCACC) using BTX ECM 830 electroporator. Efficient knock-out was measured by flow cytometry, and knock-out pure populations were isolated by cell sorting.

To generate Jurkat NFAT-GFP cells, Jurkat cells were transduced with the NFAT eGFP Reporter Lentivirus (BPS Bioscience, cat #79922), and a pure transduced cell population was obtained by cultivating the cells in the presence of puromycin.

All cell lines were routinely tested for mycoplasma contamination. Cell lines ordered from ATCC were used within 6 months of ordering or authenticated via STR analysis.

Flow cytometry

Generally, cells were washed with FACS buffer (2% FBS in PBS), incubated with antibody in the dark for 20 min at 4 C, and then washed twice and stained with DAPI to separate live/dead populations prior to analysis on a BD LSRFortessa X20 or a NovoCyte Penteon Flow Cytometer. Antibodies that required secondary staining had a similar protocol: after primary staining as described, the secondary was added before DAPI, again stained in the dark for 20 min at 4 C and washed twice. The following antibodies were used: CD19 (1:100, HIB19, Biolegend), CD271 (1:100, ME20.4-1.H4, Miltenyi), CD3 (1:50, UCHT1, BD Bioscience), CD3 (1:50, OKT3, Biolegend), CD45 (1:100, HI30, Biolegend), G4S (1:100, E7O2V, Cell Signaling Technology), CLDN18.2 (1:100, 101676, BPS Bioscience). Precision Count Beads (Biolegend) were used according to manufacturer recommendations for CAR quantification in blood samples. All data were collected using the BD FACSDiva software and analyzed using FlowJo Software.

Immunohistochemistry

For IHC, murine tumors were washed in PBS and then incubated overnight in 4% paraformaldehyde (PF Thermo-Fisher Scientific AAJ19943K2), followed by serial incubations in 30%, 50%, and finally 70% ethanol for storage until staining. Staining was performed using the services of the MGH specialized histopathology services core facility. The following antibodies were used: Anti-Claudin18.2 antibody (EPR19202, Abcam, ab222512). Anti-human CD3 (2GV6, Roche, 790-4341). Anti-Claudin18.2 (hu8e5) antibody (custom antibody production, Genscript). Anti-mCherry antibody (1C51, Abcam, ab125096). Images were acquired with ZEISS Axio Scan.Z1. CD3+ cells quantifications in tumor and stomach tissues were performed using default settings of QuPath. The following tissue microarrays were used: Human Multi-Organ Tissue MicroArray (Normal) (Novus Biologicals, NBP2-30189) and Mouse (BALB/c strain) multiple organ normal tissue array, 24 cases/ 54 cores, replacing MO541e (Amsbio, MO541f).

Construction of CARs

Anti-CLDN18.2 (Zolbetuximab22, hu8e514,23) and mesothelin (M5) CAR T constructs were synthesized (GenScript) under the regulation of a human EF-1ɑ promoter and cloned into a third-generation lentiviral backbone. Most CAR constructs contained a CD8 or CD28 hinge and transmembrane domain as indicated, CD28 costimulatory domain (unless otherwise stated as 41BB), CD3ζ signaling domain, and fluorescent reporter mCherry to evaluate transduction efficiency. AND-gate CAR constructs contained a CD8 or CD28 hinge and transmembrane domain, SLP76ΔGADS or LATΔGADS (sequences were obtained from the original manuscript21) and truncated CD19 or LNGFR to evaluate transduction efficiency.

Lentiviral production

HEK293 T cells from ATCC were cultured in RPMI supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum and 1X penicillin streptomycin. Synthesized CAR constructs were transfected with third-generation packaging plasmids using Lipofectamine 3000 and P3000 (ThermoFisher Scientific) in OptiMEM (Gibco) media. Viral supernatants were harvested 24 and 48 h after transfection, combined, filtered and concentrated by ultracentrifugation (ThermoFisher Scientific Sorvall WX+ Ultracentrifuge) at 25000 RPM for 2 h at 4 C. Concentrated virus was stored at −80C and titered on SUPT1 cells to determine MOI for transduction of primary T cells via mCherry expression, CD19 or LNGFR staining.

CAR T cell production

An Institutional Review Board protocol approved the purchase of anonymous human healthy donor leukapheresis products from the MGH blood bank. Stem Cell Technologies T cell Rosette Sep Isolation kit was used to isolate T cells. Bulk human T cells were activated on Day 0 using CD3/CD28 Dynabeads (Life Technologies) at a 1:3 T cell:bead ratio to generate CAR T cells and untransduced T cells from the same donors to serve as controls. T cells were grown in RPMI 1640 media with GlutaMAX and HEPES supplemented with 10% FBS, penicillin, streptomycin, and 20IU per ml recombinant human IL-2 (Peprotech). On Day 1 (24 h after activation), cells were transduced with CAR lentivirus at an MOI of 5. T cells continued expanding with media and IL-2 addition every 2–3 days. Dynabeads were removed via magnetic separation on Day 7, and cells were assessed by flow cytometry for mCherry expression on Days 12–14 to determine transduction efficiency prior to cryopreservation. Microbead-based CD19 (Miltenyi) and LNGFR (Miltenyi) selections were performed on Days 8 and 11 for AND-gate CAR T cells. Prior to use in in vitro and in vivo functional assays, CAR T cells and untransduced cells were thawed and rested for 18–24 h in the presence of IL-2.

Cytotoxicity assays

CAR T cells were incubated with GFP-expressing tumor cells at the indicated effector to target (E:T) cell ratios for 72–96 h. Green fluorescence was measured every 2 h using an Incucyte live cell imaging and analysis system with Sartorius software (version 2022 A).

NFAT activation assay

For CLDN18.2 CAR epitope mapping, the cDNA encoding for Claudin18.2, Claudin18.1, or Claudin18.2 mutants were synthesized and cloned under EF1a promoter in a bicistronic lentiviral vector encoding also for mTAGBFP2 (Genscript). Wt Jurkat cells were transduced with each Claudin-expressing lentiviral vector, and transduced mTAGBFP2+ cells were isolated by cell sorting. NFAT-GFP transduced CLDN18.2 (Zolbe or hu8e5) CAR-expressing Jurkat cells were cultured with jurkat cells WT, or expressing Claudin 18.1, Claudin18.2 or Claudin18.2 mutants at a 1:1 ratio for 16 h. Cells were analyzed by flow cytometry for GFP expression.

A similar approach was used for testing LINK CAR specificity in vitro. CAR-expressing Jurkat cells were cultured alone or with WT, mesothelin KO, or Claudin18.2 KO GSU cells.

In vivo models

GSU or NUGC-4 cells were administered subcutaneously with 2e6 cells in 100ul of a 1:1 mixture of PBS and Matrigel (Corning) and engrafted for 10 days prior to CAR+ cells being administered intravenously in 100ul PBS. Animals were monitored biweekly for body weight and tumor volume (caliper measurements). Animals were euthanized as per the experimental protocol or when they met pre-specified endpoints defined by the IACUC. The maximal tumor size allowed was a diameter of 20 mm, which was not exceeded. One animal technician who performed all animal injections and monitoring was blinded to expected outcomes. All animal experiments included 5 animals per group. Mice were randomized post-tumor injection prior to treatment.

Statistical methods

Based on previous studies, groups of at least 5 mice were used to detect statistical differences between groups. Analyses were performed with GraphPad Prism 9 (version 9.0). The tests used are indicated in the corresponding figure legends. All tests were two-sided. The 2-way ANOVA test was conducted without assuming sphericity. Significance was considered for P < 0.05 as the following: p = *< 0.05, **< 0.01, ***< 0.001, ****< 0.0001.

Illustrations

Illustrations in Figs. 1D, 2A, 2H, 2N, 3A, 5A, 5F, and Supplementary Figs. 4A, 5A, 6A, 7B, 7D were created in BioRender (Created in BioRender. Birocchi, F. (2025) https://BioRender.com/ foaa417) and edited in Adobe Illustrator.

Gene expression data analyses

Gene- and Isoform-level expression measurements for samples from the Genotype-Tissue Expression (GTEx) consortium were obtained from the “V8” release37. Raw data from gastric and esophageal adenocarcinoma samples of the Cancer Genome Atlas (The Cancer Genome Atlas Nature 201738, dbGaP accession phs000178) were processed using an identical pipeline including alignment with STAR v2.5.3a to hg38 using gencode annotation v26, isoform quantification by RSEM v1.3.0, and QC and gene-level quantification using RNA-SeQC v1.1.9. Expression values normalized to transcripts-per-million were taken for downstream analysis.

Reporting summary

Further information on research design is available in the Nature Portfolio Reporting Summary linked to this article.

Data availability

All requests for raw and analyzed data will be reviewed by Massachusetts General Hospital to determine if they are subject to intellectual property or confidentiality obligations. Any data and materials that can be shared will be released using a material transfer agreement. Please contact Marcela V. Maus at mvmaus@mgh.harvard.edu. Source data are provided with this paper.

References

Siegel, R. L., Miller, K. D., Fuchs, H. E. & Jemal, A. Cancer statistics, 2022. CA Cancer J. Clin. 72, 7–33 (2022).

Shitara, K. et al. Molecular determinants of clinical outcomes with pembrolizumab versus paclitaxel in a randomized, open-label, phase III trial in patients with gastroesophageal adenocarcinoma. Ann. Oncol. 32, 1127–1136 (2021).

Alsina, M., Diez, M. & Tabernero, J. Emerging biological drugs for the treatment of gastroesophageal adenocarcinoma. Expert Opin. Emerg. Drugs 26, 385–400 (2021).

Roviello, G. et al. Current status and future perspectives in HER2-positive advanced gastric cancer. Clin. Transl. Oncol. 24, 981–996 (2022).

Maude, S. L. et al. Tisagenlecleucel in children and young adults with B-cell lymphoblastic leukemia. N. Engl. J. Med. 378, 439–448 (2018).

Neelapu, S. S. et al. Axicabtagene Ciloleucel CAR T-Cell Therapy in Refractory Large B-Cell Lymphoma. N. Engl. J. Med. 377, 2531–2544 (2017).

Munshi, N. C. et al. Idecabtagene vicleucel in relapsed and refractory multiple myeloma. N. Engl. J. Med. 384, 705–716 (2021).

Berdeja, J. G. et al. Ciltacabtagene autoleucel, a B-cell maturation antigen-directed chimeric antigen receptor T-cell therapy in patients with relapsed or refractory multiple myeloma (CARTITUDE-1): a phase 1b/2 open-label study. Lancet 398, 314–324 (2021).

June, C. H. & Sadelain, M. Chimeric antigen receptor therapy. N. Engl. J. Med. 379, 64–73 (2018).

Qi, C. et al. Claudin18.2-specific CAR T cells in gastrointestinal cancers: phase 1 trial final results. Nat. Med. 30, 2224–2234 (2024).

Sahin, U. et al. Claudin-18 splice variant 2 is a pan-cancer target suitable for therapeutic antibody development. Clin. Cancer Res. 14, 7624–7634 (2008).

Kubota, Y. et al. Comprehensive clinical and molecular characterization of claudin 18.2 expression in advanced gastric or gastroesophageal junction cancer. ESMO Open 8, 100762 (2023).

Bähr-Mahmud, H. et al. Preclinical characterization of an mRNA-encoded anti-Claudin 18.2 antibody. Oncoimmunology 12, 2255041 (2023).

Jiang, H. et al. Claudin18.2-specific chimeric antigen receptor engineered T cells for the treatment of gastric cancer. J. Natl Cancer Inst. 111, 409–418 (2019).

Nakayama, I. et al. Claudin 18.2 as a novel therapeutic target. Nat. Rev. Clin. Oncol. 21, 354–369 (2024).

Shitara, K. et al. Zolbetuximab plus mFOLFOX6 in patients with CLDN18.2-positive, HER2-negative, untreated, locally advanced unresectable or metastatic gastric or gastro-oesophageal junction adenocarcinoma (SPOTLIGHT): a multicentre, randomised, double-blind, phase 3 trial. Lancet 401, 1655–1668 (2023).

Sahin, U. et al. FAST: a randomised phase II study of zolbetuximab (IMAB362) plus EOX versus EOX alone for first-line treatment of advanced CLDN18.2-positive gastric and gastro-oesophageal adenocarcinoma. Ann. Oncol. 32, 609–619 (2021).

Qi, C. et al. Claudin18.2-specific CAR T cells in gastrointestinal cancers: phase 1 trial interim results. Nat. Med 28, 1189–1198 (2022).

Zhong, G. et al. Complete remission of advanced pancreatic cancer induced by claudin18.2-targeted CAR-T cell therapy: a case report. Front. Immunol. 15, 1325860 (2024).

Zhong, G. et al. The high efficacy of claudin18.2-targeted CAR-T cell therapy in advanced pancreatic cancer with an antibody-dependent safety strategy. Mol. Ther. 33, 2778–2788 (2025).

Tousley, A. M. et al. Co-opting signalling molecules enables logic-gated control of CAR T cells. Nature 615, 507–516 (2023).

Wang, H., Song, B. & Cai, X. Immunologic effector cell of targeted CLD18A2, and preparation method and use thereof. US Patent No US 12,098,199 B2 (2021).

Li, Z., Luo, H., Jiang, H. & Wang, H. Genetically engineered cell and application thereof. US Patent Appl. US 2021/0213061 A1 (2021)

Türeci, Ö et al. Claudin-18 gene structure, regulation, and expression is evolutionary conserved in mammals. Gene 481, 83–92 (2011).

Salter, A. I. et al. Phosphoproteomic analysis of chimeric antigen receptor signaling reveals kinetic and quantitative differences that affect cell function. Sci. Signal. 11, eaat6753 (2018).

Han, S.-H., Joo, M., Kim, H. & Chang, S. Mesothelin expression in gastric adenocarcinoma and its relation to clinical outcomes. J. Pathol. Transl. Med. 51, 122–128 (2017).

Haas, A. R. et al. Two cases of severe pulmonary toxicity from highly active mesothelin-directed CAR T cells. Mol. Ther. 31, 2309–2325 (2023).

Brehm, M. A. et al. Lack of acute xenogeneic graft- versus -host disease, but retention of T-cell function following engraftment of human peripheral blood mononuclear cells in NSG mice deficient in MHC class I and II expression. FASEB J. 33, 3137–3151 (2019).

Xu, Q., Jia, C., Ou, Y., Zeng, C. & Jia, Y. Dark horse target Claudin18.2 opens new battlefield for pancreatic cancer. Front. Oncol. 14, 1371421 (2024).

Shah, M. A. et al. Zolbetuximab plus CAPOX in CLDN18.2-positive gastric or gastroesophageal junction adenocarcinoma: the randomized, phase 3 GLOW trial. Nat. Med 29, 2133–2141 (2023).

Liu, Y. et al. FAP-targeted CAR-T suppresses MDSCs recruitment to improve the antitumor efficacy of claudin18.2-targeted CAR-T against pancreatic cancer. J. Transl. Med 21, 255 (2023).

Shi, H. et al. IL-15 armoring enhances the antitumor efficacy of claudin 18.2-targeting CAR-T cells in syngeneic mouse tumor models. Front. Immunol. 14, 1165404 (2023).

Lee, H. J., Hwang, S. J., Jeong, E. H. & Chang, M. H. Genetically engineered CLDN18.2 CAR-T cells expressing synthetic PD1/CD28 fusion receptors produced using a lentiviral vector. J. Microbiol. 62, 555–568 (2024).

Kloss, C. C. et al. Dominant-negative TGF-β receptor enhances PSMA-targeted human CAR T cell proliferation and augments prostate cancer eradication. Mol. Ther. 26, 1855–1866 (2018).

Lamers, C. H. J. et al. Treatment of metastatic renal cell carcinoma with autologous T-lymphocytes genetically retargeted against carbonic anhydrase IX: first clinical experience. J. Clin. Oncol. 24, e20–e22 (2006).

Morgan, R. A. et al. Case report of a serious adverse event following the administration of T cells transduced with a chimeric antigen receptor recognizing ERBB2. Mol. Ther. 18, 843–851 (2010).

Aguet, F. et al. The GTEx Consortium atlas of genetic regulatory effects across human tissues. Science 369, 1318–1330 (2020).

Integrated genomic characterization of oesophageal carcinoma. Nature 541, 169–175 (2017).

Acknowledgments

FB is supported by the American Italian Cancer Foundation (AICF) and the Italian Foundation for Cancer Research (AIRC). This project is supported by SU2C (MVM). This research is supported by the Specialized Histopathology Services- MGH (DF/HCC) Core Facility of the Dana-Farber/Harvard Cancer Center (P30 CA06516).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

F.B., M.V.M., and T.R.B. conceived the study. F.B. planned and performed the experiments, interpreted data, and wrote the manuscript. A.J.A., A.P., A.A.B., S.G., C.K., A.M., and J.F. performed the experiments. N.J.H., S.K., and G.G. performed and interpreted the analysis of patients’ gene expression data. All authors, including M.B.L., G.E., and D.S.B. contributed intellectually to the experiments as well as editing and approval of the final version of the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

MVM is an inventor on patents related to adoptive cell therapies, held by Massachusetts General Hospital (some licensed to Promab and Luminary) and University of Pennsylvania (some licensed to Novartis). MVM receives Grant/Research support from: Kite Pharma, Moderna, Sobi. MVM has served as a consultant for multiple companies involved in cell therapies. MVM holds Equity in 2SeventyBio, A2Bio, Affyimmune, BendBio, Cargo, GBM newco, Model T bio, Neximmune, Oncternal. MVM serves on the Board of Directors of 2Seventy Bio. None of the above is directly relevant to the data presented in this manuscript. The remaining authors declare no competing interests.

Peer review

Peer review information

Nature Communications thanks Prasad Adusumilli, Yanping Yang and the other, anonymous, reviewer(s) for their contribution to the peer review of this work. A peer review file is available.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Source data

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Birocchi, F., Almazan, A.J., Parker, A. et al. On-target off-tumor toxicity of claudin18.2-directed CAR-T cells in preclinical models. Nat Commun 16, 9650 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-025-61858-z

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-025-61858-z