Abstract

High-performance flexible sensing electronics on complex surfaces operating across broad temperatures are critical for aerospace and industrial applications. However, existing flexible sensors and materials face limitations in sensitivity and thermal stability. Here, we report an ink-engineering strategy to directly print single-face MoWNb medium entropy alloy paints on arbitrary surfaces without complicated post-processing. These sensors exhibit exceptional strain sensitivity (gauge factor up to −752.7 at 300 °C), a low detection limit (0.57 με), and superior thermal stability from −150 to 1100 °C. Through a cyclic dispersing/re-printing process, the fully recyclable sensors retain electrical properties and sensing performance. Furthermore, by integrating with a long-range radio module, we demonstrate a wireless sensing system for in-situ and real-time monitoring of a morphing aircraft under various extreme environments. Our findings provide a convenient and efficient approach for the direct fabrication of flexible sensors and the seamless integration into sensing systems that work reliably in harsh environmental conditions.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Flexible sensing electronic devices and integrated systems have attracted considerable attention in intelligent medicine, wearable healthcare, and human-machine interaction due to the high deformability, light weight, thin structures, and optical transparency1,2,3,4. In recent years, the applications of flexible sensors and systems have also been expanded to several specific areas of aerospace, supersonic vehicle, and nuclear industry for status monitoring of aircraft engines, combustion chambers, and turbine blades5. Along with this, several critical challenges emerge for these devices operating in extreme environments. For example, the high performance of flexible sensors at ambient conditions may degrade or even lose in harsh conditions because of the materials’ intrinsically poor resistance to temperature, pressure, and humidity6,7,8. Additionally, the interfaces between sensitive layer and substrate might delaminate with the increase in temperature due to the mismatch of thermal expansion coefficients9,10. Currently, various emerging flexible materials and several unique strategies have been developed to enhance the interface stability and the resistance to corrosion gas, high pressure, low-, and high-temperatures to withstand the operation in extreme environments6,11. Among them, ceramic materials and the related strain sensors possess unique features of high temperature-resistance5,12,13,14, corrosion resistance15,16, and excellent strain sensing performance (high strain sensitivity: >10014,17,18, superior stability and durability at temperatures higher than 800 °C19,20. However, for most ceramics, it is not easy to achieve mechanical flexibility due to their intrinsic brittleness. While compositing with polymer matrix offers flexibility and stretchability for wearable devices21, these organic-inorganic nanocomposites are typically unsuitable for high-temperature applications due to thermal degradation or decomposition of polymer binders at elevated temperatures. Besides, manufacturing of ceramic sensors typically requires thermal annealing at high temperatures14,17, which is incompatible with most flexible substrates. Metallic sensors are commonly utilized in several flexible scenarios with satisfactory sensitivity and stability22,23,24,25. However, due to the poor resistance to corrosion and oxidation, metals and metallic alloys-based flexible sensors are hardly applied in ultrahigh-temperature environments26,27,28. Therefore, it is highly desirable and urgent to explore new materials and novel strategies to construct flexible sensors and systems for stable operation at extreme environments.

Entropy alloys (EAs), including high-entropy alloys (HEAs) and medium-entropy alloys (MEAs), are an emerging and promising class of materials with highly customizable structures and unprecedented features, such as elevated temperature mechanical strength, high resistance to corrosion, and unique electrical properties29,30. In the past decade, numerous efforts have been devoted to exploring these alloys for vast applications in the fields of energy31, mechanicals32, and catalysts33,34. Recently, EAs have also been applied to flexible sensing electronics owing to their larger baric response, stronger resistance to oxidation, higher thermal and electrical conductivity, leading to relatively high sensitivity, wide linearity, and broad detection limit of EAs-based sensors35,36,37,38. However, their remarkable properties have not been heavily investigated in flexible sensors and integrated systems, especially operating at low- and high-temperature ranges. At cryogenic temperatures, most EAs have high brittleness39 and low fracture toughness40, which may bring failure in flexible devices under mechanical deformations. Oxidation and phase instability are typical challenges for EAs at high temperatures33. The fabrication process of EA materials and corresponding flexible electronic devices is complex, which typically consists of extra post-treatment procedures (e.g., rolling deformations from bulky counterparts35, thermal annealing precursors at 800 °C41,42, pyrolysis33, etc.), resulting in a high cost and difficulty in conformal contact with curved surfaces.

Here, we report a direct printing strategy to fabricate flexible sensing devices on arbitrary surfaces with exceptional sensitivity and detection limit over an ultra-wide temperature range. To this end, utilizing single-face MoWNb refractory MEAs as sensitive materials, we develop a paintable and writable ink for high-performance strain sensing that can be deposited on flat, curved, and waved surfaces of glasses, ceramics, polymers, and metals. The lattice deformation in the atoms and the stress concentration in the printed films lead to the high sensitivity of the printed sensors to bending strains. With the optimized inks and printing process, we have achieved a collection of compelling sensing performance, including high strain sensitivity, an ultra-broad working temperature regime, a low strain detection limit, and a broad strain range. Interestingly, the materials are recyclable, and the high performance of the painted sensors with recycled MoWNb powder is well maintained. To demonstrate the feasibility of the proposed strategy, we demonstrate a flexible wireless sensing system by integrating the directly printed sensing units on wings with a long-range radio (LoRa) module for real-time monitoring of the status of a morphing aircraft at various extreme conditions.

Results

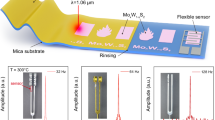

Principle of the painting electronics and integrated system

The overall process for the MEAs synthesis, ink preparation, painting electronics, and system integration is shown in Fig. 1a, b. Supplementary Fig. 1a shows the photographs of the procedures of material synthesis, including precursor preparation, drying, and thermal annealing. The metal salts were dispersed and mixed well in a mixture solution comprising ethanol and water as the precursor. After drying completely, a thermal annealing process is applied for the decomposition and reduction of these metal salts with the assistance of high-concentration hydrogen gas (92% in volume) at 1000 °C (“Methods” section). After cooling down to room temperature naturally, MoWNb elements are mixed, and MEAs powders are obtained. Note that the process is highly scalable, verified by the gram scale synthesis in one batch (Supplementary Fig. 1b), which benefits the practical applications. The MEAs inks are prepared by mixing the grinded powders with a trace amount of organic binder (ethylene cellulose) in a solvent mixture of terpilenol and ethanol (“Methods” section). Dual solvents with both high boiling and low points are beneficial for tuning the viscosity and evaporation temperature of the paints for mask printing and direct writing with a relatively slow drying rate. Ethyl cellulose is an effective stabilizer and thickening agent to help stabilize the MEA particles, tailor the viscosity of the ink (Supplementary Fig. 2), and enhance the adhesion with target surface (Supplementary Fig. 3). The resultant ink is used to directly fabricate electronic devices on a curved morphing aircraft wing and dried with an infrared lamp without extra process, providing a convenient approach for sensor fabrication at low temperature. It should be noted that a sintering process with high temperatures is typically required in the fabrication of high-temperature sensors, such as annealing14,43,44,45, co-sintering17,24, and laser pyrolysis5,20,46,47. Using the direct fabrication strategy, we then integrate the painted sensors with a wireless LoRa module to construct a long-range monitoring system for evaluating the flying and morphing status of a morphing aircraft at several extreme conditions, such as fire flaming and cryogenic environments (Fig. 1b).

a (i) Schematic diagram of the synthesis process of MoWNb MEA nanoparticles. Zoomed-in schematic shows the hydrogen reduction of the metal salts to MEA elements. Insets are photographs of materials in a ceramic boat before and after thermal annealing. (ii) Photograph of the MEA powders in a gram scale. (iii) Photograph of the prepared MEA ink. (iv) Schemes of the patterning process on an aircraft wing using mask printing and direct writing. Inset is a photograph of the direct writing process. b Schematic illustration showing the printed sensors and the integration with a wireless module on a morphing aircraft. Four sensors are attached to the wings for monitoring the flying and morphing status of the aircraft at various extreme conditions with different temperature regimes. c Sensing mechanism of the printed MoWNb MEA sensors. (i) Simulated stress distribution in the macroscopical film and the calculated resistance variation as a function of bending strains at 500 °C, showing a linear correlation. The calculated GF is 448.5. (ii) Simulated stress distribution in the nanoscale structure under tensile strain. (iii) Lattice structure and the calculated electronic conductivity of MoWNb MEAs under various lattice strains based on DOS results in the DFT calculation, showing a high linear correlation. d–i Photographs of the printed flexible and stretchable circuits and conductive structures on various intricate surfaces, such as hemi-glass tube, wavy plastic, oblique ceramic, flexible polymer, and serpentine aluminum. LEDs are also mounted in the circuits to verify the high conductivity and the stability of the printed lines.

The sensing properties of the prepared MoWNb MEAs-based flexible sensors at both high and low temperatures are largely attributed to the multiscale structures of the MEA films. A model of the macroscopical film and the nanoscale structure of the printed MEA film is constructed to investigate the stress distribution of the structure under strains. As shown in Fig. 1c, the stress concentration is mainly distributed at the fixed ends and the central part of the MEA film, leading to the most significant deformation within the MEA film. This behavior is consistent with the typical strain-sensitive films14,48. To understand the sensing mechanism, we have conducted a thorough simulation and comprehensively analyzed the data to establish a mechanistic link between mechanical strain and electrical response of the MEA film at elevated temperatures. In COMSOL Multiphysics, we have implemented the solid mechanics interface, electric currents interface, and multiphysics coupling to achieve thermo-electro-mechanical simulations. In the solid mechanics interface, we calculate stress (σ) and strain (ε) fields by incorporating temperature-dependent material properties (e.g., elastic modulus, Poisson’s ratio, thermal expansion coefficient). In the electric currents/circuit interface, we utilize deformed geometry (i.e., varied lengths and cross-sectional areas under strain) and define resistivity as a function of both temperature and strain. We then achieve the calculation of temperature-dependent strain and stress, considering thermal expansion and varied resistance under geometry change. Finally, we establish a stress-strain-temperature relationship, achieving a two-way coupling by transferring strain fields to electrical calculations by accounting for temperature-dependent elastic modulus (Supplementary Note 1). It is found that there is a linear relationship between strain and stress at various temperatures (Supplementary Fig. 4a, b). Moreover, simulation results confirm the approximately linear correlations among stress, strain, and resistance changes under different temperatures (Supplementary Figs. 5 and 6). Multivariate linear regression yields a maximum R-square value of 0.9906, indicating excellent linearity, which validates the model’s capability for strain simulation under varying thermal conditions. We also calculate the strain sensitivity by fitting the strain-resistance curves. The simulated results show that the sensor exhibits gauge factors of several hundred at high temperatures (Fig. 1c and Supplementary Fig. 6), confirming the high strain sensitivity.

In the nanoscale structure, the concentrated stress may induce a loose contact of neighboring nanoparticles, leading to possible breakage of conductive pathways49,50, which results in a noticeable change in electrical resistance of MEA film under strains. To confirm this behavior, we have investigated the interparticle contacts and microstructural evolution of the MEA particles under strain through in-situ scanning electron microscopy (SEM) observation. It is found that the contact between adjacent particles will be weak, and a complete separation occurs at a strain of 5% (Supplementary Fig. 7a–e). The particles are reconnected upon the strain removal. Consistent with the microstructural evolution, resistance variation of the MEA patterns under strain is highly repeatable without failure throughout the stretching cycles (Supplementary Fig. 7f). Note that the slight drift in the output signals is ascribed to the hysteresis of polyimide fiber membrane under mechanical strain, which can be eliminated by substrate optimization.

To further study the sensing behavior and the physical mechanisms of the MEA film under strains, we conduct first-principles density functional theory (DFT) calculations of the electronic structures within the MoWNb MEA (“Methods” section). A cubic supercell with randomly seeded Mo, W, and Nb atoms is constructed on the sites of body-centered cubic (BCC) lattice (Fig. 1c). Tensile and compressive strains in the range of −1.5% to 1.5% are subjected to the MoWNb lattice structure and the total electronic densities of states (DOS) under strains are calculated. As shown in Supplementary Fig. 8a, a noticeable effect of strain on the DOS is observed under both compression and tension. Specifically, the calculated DOS of the MoWNb alloy decreases with the increase in tensile strains, while there is an increase in the DOS under compression. This leads to the variation in the electrical resistivity of the MoWNb alloy, contributing to the enhancement of strain sensitivity. The mechanistic link between atomic-scale lattice distortion under strain and the macroscopic electronic conductivity is further estimated based on the Drude model (Supplementary Note 2). It is found that there is a linear relationship between the estimated electrical conductivity and the lattice strain in the range of −1.5% to 1.5% (Fig. 1c and Supplementary Fig. 8b). Specifically, the electrical conductivity increases under compression lattice strain, while there is a decrease in electrical conductivity when the lattice is stretching. After linear fitting, we can obtain a strain sensitivity of −9.63 in the atomic scale (Supplementary Fig. 8b), which is slightly higher than the reported value based on HEAs35. These observations suggest that the MoWNb MEAs are promising as a strain-sensitive material for high-performance flexible strain sensors.

As mentioned, the utilization of the paints and the direct writing technology enables the creation of arbitrary structures on free surfaces in a highly efficient, facile, and adaptable manner, which is feasible for the fabrication of flexible sensing electronic devices. To demonstrate the printability and feasibility of the proposed approach, we apply the resultant inks to fabricate a wide range of advanced conductive patterns through mask printing and direct writing of the MEA ink on various surfaces. The screen-printing and mask printing procedures are shown in Supplementary Fig. 9. Screen printing is utilized to print large-area patterns and multiple sensors on polyethylene terephthalate substrate, while a polyimide mask is applied on a tube to help directly fabricate sensors on curved surface. As shown in Fig. 1d–i, various intricate structures, including flowers, cartoons, lines, curves, and wave lines, are printed or written on curved glasses, ceramics, plastics, polymers, and aluminum. These painted structures are conductive, as verified by the successful illumination of light-emitting diodes (LEDs) through the lines. It should be noted that the inks can also be painted on metallic surfaces with an insulating layer to produce stretchable conductors (Supplementary Fig. 10a, b). The resultant structures maintain their high conductivity even after being subjected to a tensile strain of about 18% (Supplementary Fig. 10c–e), demonstrating their ability to fabricate flexible and stretchable electronic devices. We also evaluate the morphology of the printed microstructures. As shown in the SEM images in Supplementary Fig. 11a, straight lines obtained through screen printing have achieved a minimum line width of about 280 μm, and the lines have sharp and clear edges with dense particles. According to the elemental mappings by energy-dispersive X-ray spectroscopy (EDS), the elements of Mo, W, and Nb are evenly distributed in the lines (Supplementary Fig. 11b), confirming the uniformity of the structure and the existence of Mo, W, and Nb elements. Additionally, we have investigated the morphological behavior of the printed lines through both mask printing and direct writing. Similar to the screen-printed lines, we observe clear edges of the printed lines on glass tube, ceramic, and morphing aircraft (Supplementary Fig. 12).

MoWNb MEAs-based nanostructures

The as-prepared products were initially characterized macroscopically via a powder X-ray diffraction (XRD) measurement to investigate the crystal structures. As shown in Fig. 2a, a series of sharp and dominant diffraction peaks at 40.38°, 58.47°, 73.45°, and 87.51° are observed, which are indexed to the crystal planes of a BCC structure32,51, indicating the formation of a highly crystalline single-phase solid solution. We also evaluated the phase characteristics of the products annealed with a smaller concentration of hydrogen gas or lower sintering temperatures (i.e., 900 °C). The phase characterizations show that there is detectable impurity in the alloys (Supplementary Fig. 13), which is identified as the crystalline phase signals from NbO2. It indicates that providing a sintering environment with a higher concentration of hydrogen gas and a higher temperature throughout the process is crucial for the precursor reduction and metal element mixing to achieve single-phase MEAs51,52. We then investigated the stability of the produced alloys. The XRD patterns show no obvious change in the diffraction peaks after six months in an ambient environment (Fig. 2a), suggesting that the humidity and oxygen in the air did not markedly change the crystallinity of the MoWNb MEA nanostructures. Note that the addition of trace amounts of polymer binder into the alloys has a negligible influence on the crystalline structure and the phase composition, as confirmed by the XRD pattern of the prepared printable inks.

a Powder XRD patterns of the as-synthesized nanoparticles, stored at ambient environment for six months, and the prepared printable ink. The signals are assigned in accordance with the ref. 2 -theta positions of a single-phase BCC structure. a.u., arbitrary units. b High-resolution XPS spectra with peak fitting of Mo 3d, W 4f, and Nb 3d regions. c TEM image of the MoWNb nanostructures featuring an agglomerate with irregular shapes. Inset is the SAED of the nanostructures. d HAADF-STEM image of the MoWNb MEA nanostructures. The white lines indicate the lattice spacing of (110) and (200) planes. e Atomic-resolution HAADF-STEM image taken from the region marked by the box in (d). f Atomic-resolution HAADF-STEM image and the corresponding FFT pattern, revealing a solid solution feature with a BCC structure. g HADDF-STEM images and corresponding element mapping for the MoWNb MEAs, revealing a homogenous distribution of Mo, W, and Nb elements. h EDX pattern of the MoWNb MEAs. arb. units arbitrary units.

We further conducted X-ray photoelectron spectroscopy (XPS) measurements to analyze the chemical bonds and electronic states of the synthesized MoWNb MEA nanostructures to evaluate the chemical states of these refractory metals in the MEAs. Supplementary Fig. 14 shows the complete spectrum of XPS of the as-prepared MEAs in the binding energy region of 40–400 eV, exhibiting the presence of Mo, W, Nb, C, and O species without other metallic impurities. As shown in Fig. 2b, the high-resolution XPS spectra show that there are two Mo 3d peaks at 230 eV and 232 eV, corresponding to Mo 3d3/2 and Mo 3d5/2 of Mo metal, respectively. Similarly, the two peaks in the W 4f spectrum can be assigned to the W metal. Note that there is an oxidized state of Nb in the Nb 3d spectrum, which may be ascribed to the easy oxidation of Nb surface53.

The morphologies of the prepared MoWNb MEAs are then investigated using SEM characterization. As shown in Supplementary Fig. 15, the particles are mainly in agglomerating morphology with a nanoscale size. The EDS mappings of both the low and high magnification images show that the metal elements of Mo, W, and Nb are uniformly distributed over the entire regions. To gain in-depth insight into the unique features of the MoWNb MEAs, we characterized the resultant metallic nanostructures using transmission electron microscopy (TEM) and high-angle annular dark-field scanning TEM (HAADF-STEM). Figure 2c shows a typical TEM image of the MEA nanostructures, demonstrating a mixture of irregularly shaped nanostructures for the agglomerates with an average size of about 35 ± 12 nm (Supplementary Fig. 16). The selected area electron diffraction (SAED) pattern in Fig. 2d indicates the single-crystal BCC diffraction features of the nanostructures with diffraction rings corresponding to the (110), (200), (211), and (310) peaks, which matches with the XRD patterns (Fig. 2a). The atomic-resolution HAADF-STEM image taken from a typical nanoparticle revealed an interplane spacing of 0.24 nm and 0.15 nm, which can be assigned to the (110) and (200) lattice planes of a single-phase solid solution BCC structure (Fig. 2e, f). The fast Fourier transform (FFT) pattern further confirms a characteristic BCC structure viewed from the (110) direction. Owing to the difference in atomic weight of the three metal elements, there is a contrast difference throughout the selected areas of the nanostructures, confirming the random distribution of these elements.

We further analyzed these MEA nanostructures using energy-dispersive X-ray spectroscopy (EDX) mapping in scanning TEM. As shown in Fig. 2g, there is a uniform distribution of constituent elements in the MEA nanoparticles without composition segregation. In addition, based on the EDX results, the atomic fractions of Mo, W, and Nb elements are approximately 41.7%, 34.7%, and 23.6%, respectively (Fig. 2h). All these results confirm the successful preparation of high-crystallinity and high-quality refractory MoWNb MEAs nanostructures, holding great application prospects in the fields of catalysis, energy storage, and mechanical sensors.

Sensing properties of the printed flexible sensors

Using the solid solution MoWNb MEAs, we prepared paintable and printable inks for the direct fabrication of flexible sensors and systems on arbitrary surfaces. We first deposit the ink on temperature-resistant flexible mica substrate using a mask printing method for the realization of flexible mechanical sensors toward extreme environments. The electromechanical behaviors of the sensors are investigated over a wide temperature regime. First, we evaluated their mechanical sensitivity at elevated temperatures by applying bending-induced tensile or compressive strains to the sensors. A specially designed testing system is used for the measurement, which comprises a temperature controlling module, a mechanics controlling module, and a data acquisition module (Supplementary Fig. 17). A furnace tube and a step motor are utilized to provide a variable temperature environment and different mechanical strains to the sensors, respectively. When the strains in the sensors change via the movement of the step motor, the resistance signals are recorded through a source meter and transmitted the collected data to a computer. The applied strains are calculated based on a cantilever model (Supplementary Note 3).

Supplementary Fig. 18a shows the resistance change of the fabricated sensors as a function of different strains from 28.6 to 258 με. There is an increase in the resistance change under a tensile strain, while the resistance decreases when a compressive strain is applied to the sensor. The resistance variations with the in-plane strain are slightly larger than those of the compressive strain at room temperature, which is consistent with the strain sensors in the literature49. The relative change in resistance (ΔR/R0) as a function of the applied strains for the MEAs-based sensors is displayed in Supplementary Fig. 18b, where ΔR and R0 indicate the resistance change and the initial resistance, respectively. The figure of merit (i.e., gauge factor, GF) for the strain sensors can be obtained by linearly fitting the curve. The flexible sensor exhibits a GF of 534.9 and −513.6 at room temperature under tensile and compressive states, respectively (Supplementary Fig. 18b). The fitting curves for both states show relatively high linearity of more than 98%. The electromechanical properties of the sensors under tensile strains are highly repeatable, and the resistance variations in two cycles are approximately consistent despite the applied strains (Supplementary Fig. 18c). We then evaluate the electromechanical behaviors of the sensors with tensile and compressive strain at high temperatures. As expected, the GFs of the flexible sensor under tensile strains are coincident with that at compressive state when the temperatures vary from 500 to 1000 °C (Supplementary Figs. 18d–f and 19). To avoid the possible damage of the brittle mica substrate because of the relatively larger tensile strains, we applied compressive strains to the sensor in the following experiments.

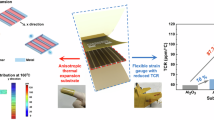

To comprehensively investigate the electromechanical behavior of the MEAs materials and the sensing performance of the printed flexible sensors at extreme environments, we recorded the resistance change of the MEA strain sensors by applying microstrains from 28.6 to 258 με at an ultra-wide temperature range from −150 °C to 1100 °C. As shown in Supplementary Fig. 20, the resistances of the strain sensors decrease monotonically as the applied strains increase over the entire temperature range. Figure 3a shows four representative curves of the relative resistance change as a function of microstrains, as well as the fitted curves with calculated GFs. High linear relationships are found in these curves with a high correlation coefficient of more than 97% (Supplementary Fig. 21), benefiting the precise data acquisition at different bending states. The GFs of the sensors are determined to be −364.1, −513.6, −712.3, and −280.3 at temperatures of −150, 25, 500, and 900 °C, respectively, indicating that high GFs are maintained at a wide temperature range. We also evaluate the electrical response of the sensors at temperatures larger than 900 °C. There is a high linearity for the sensors working at 1000 °C, and the calculated GF is −41.7. When the temperature further increases to 1100 °C, the GF slightly decreases to −32.9 (Supplementary Fig. 22). Despite the relatively unstable resistance variations, the MEA sensor exhibits reversible and repeatable responses to strains at 1100 °C, which is hardly achieved for strain sensors reported in the literature. The ultra-wide working range can cover the lower and higher temperature ranges of various scenarios, such as space exploration. Note that the GF of the sensor initially increases to a value of −752.7 as the temperatures increase from −150 °C to 300 °C. At larger temperatures, the GFs of the sensors decrease. The behavior is consistent with that of the high-temperature strain sensors obtained with ceramic materials54, metals17,22, and metal alloys25.

a Relative change in resistance of a single sensor as a function of the applied microstrains at various temperatures from −150 °C to 900 °C. The solid lines are the linear fitting results, showing the linearity and GFs. b Comparison of the GF values and the working temperature regime among the printed flexible strain sensors in the current study and the representative high-temperature strain sensors based on metals, metal alloys, ceramics, carbons, polymers, and semiconductors reported in the literature. GFs are absolute values for easy comparison. c Long-term stability and durability of the MEA sensor tested at 900 °C with the maximum microstrain of 258 μɛ. The almost identical electrical outputs are well maintained throughout the entire 1200 bending cycles. d Relative change in resistance of the MEA sensor under tiny and large strains from 0.57 μɛ to 4541 μɛ. There is a consistent response in several bending and releasing cycles. e Comparison of detection limit, maximum strain, and working temperature range for various high-temperature strain sensors and stretchable strain sensors. f Photographs of a sensor array under tensile strain and the measurement setup for evaluating the output of the four sensing branches under bending operation. g Distribution of the relative change in resistance in the MEA sensitive layer when different branches of the sensor array are pressed individually.

We then compare the performance of state-of-the-art high-temperature strain sensors in terms of GFs and working temperatures. It is found that the proposed MoWNb MEA strain sensor exhibits much larger GFs over an ultra-broad temperature range (Fig. 3b and Supplementary Table 1) than most strain sensors. The semiconductor-based strain sensors have relatively higher GFs. However, the working temperatures are typically limited to a relatively low value of 200 °C due to the intrinsic properties. Strain sensors based on polyimide fiber and polyimide ionogel also demonstrate a limited working temperature range55,56. Similarly, several stretchable strain sensors based on carbon nanotube57 (CNT) and MXene/CNT composites58 operate at near room temperature, despite the much larger GFs than those of our sensor. Owing to the high resistance to oxidation, ceramic sensors can operate at high temperatures over 800 °C. But they typically have small GFs. Similarly, the GFs of metallic sensors are generally not large, despite the relatively wide working temperature range. Optical fiber strain sensors typically operate stably at temperatures higher than 1000 °C59. However, their strain sensitivity is relatively low. Nevertheless, the GFs of the MEA sensor are about one orders of magnitude larger than that with noble metals17,22,26,27,28,60,61,62, metal alloys23,24,25,28, semiconductors10,48, polymers56,63, carbons64,65,66, ceramics5,12,13,18,19,20,21,54,67,68,69,70,71, and inorganic materials72. Moreover, our sensor demonstrates stable operation in cryogenic environments, which is rarely achieved in flexible strain sensors. The high sensitivity and wide operation temperatures endow the MEA strain sensors with the ability to monitor strains or deformations with high precision in various extreme scenarios, including deep-sea survey, space exploration, and combustion monitoring.

In addition to the exceptional sensitivity and working temperature range, the MEAs strain sensor has several attractive features. We first evaluate the long-term reliability by continuously applying a cyclic strain in the range of 0–258 με to the sensor for more than 1200 cycles at a temperature of 900 °C. The electrical resistance is relatively consistent, and the output signals are almost identical (Fig. 3c), revealing a highly repeatable and durable behavior. Additionally, the MEA sensors endure extremely high temperatures for a long time (1100 °C for 10 h, 1200 °C for 4 h, Supplementary Fig. 23a, b). The morphologies of the printed patterns and the MEA particles remain intact without noticeable change after the long-term thermal stability test (Supplementary Fig. 23c–e). The materials remain a single-phase solid solution with BCC structures without additional peaks (Supplementary Fig. 23f). All these results confirm the good thermal stability, durability, and reliability of the sensor, and the material integrity after the thermal test. Moreover, the stable operation of the sensor is also well maintained when the sensor is loaded with the cyclic strain at cryogenic condition (Supplementary Fig. 24). The high reliability under cyclic bending and compressing states reveals that the dynamical deformation on the curved surfaces can be achieved without degradation in the sensing performance over an ultra-wide temperature range.

We also evaluate the limit of detection of the sensor, which is defined as the detectable output signals at a minimum and maximum strain. Figure 3d indicates that the minimum and maximum strains in our measurement are 0.57 μɛ and 4541 μɛ, respectively. The relative resistance change of the sensor linearly increases from approximately 0.025% to 0.06% when the microstrains increase from 0.57 μɛ to 2.86 μɛ. Furthermore, highly reversible outputs are also observed at each microstrain for more than five cycles (Supplementary Fig. 25), revealing the high stability and reproducibility of the flexible sensor to microstrains. We also examine the electrical response to larger strains using another home-made test system (Supplementary Fig. 26 and Supplementary Note 4). The resistance variation increases to −52.7% at a strain of 4541 μɛ (Fig. 3d), which is more than three orders of magnitude larger than that of microstrains. As expected, the electrical response to large strains in the range of 0–4108 μɛ is well maintained for three repeated cycles (Supplementary Fig. 27). In addition, when a cyclic bending of a maximum strain of 4541 μɛ is subjected to the sensor, both the wave patterns and the baseline of the output resistance changes of the MEA sensor remained stable and identical over more than 1000 cycles (Supplementary Fig. 28), demonstrating its long-term stability under large strains.

Compared with the state-of-the-art high-temperature strain sensors, our MoWNb MEA sensors demonstrate several advantages. First, a reliable response to microstrains with a minimum value of 0.57 μɛ is achieved, which is more than two orders of magnitude smaller than that of the reported strain sensors based on ceramics, metals, semiconductors, optical fibers, polymers, hydrogels, and carbons (Fig. 3e and Supplementary Table 1). Secondly, the MEA strain sensors exhibit a wide strain range with a maximum strain up to 4541 μɛ, outperforming most previous values in the literature (Supplementary Table 1). Note that the strain range is much lower than that of stretchable strain sensors56,57,58 due to the flexion sensing mechanism of our sensor. The MEA sensors can operate at an ultra-broad temperature range from −150 °C to 1100 °C, which is much wider than the reported values.

The strain resolution is another important parameter to characterize the ability of the strain sensors to distinguish the minimum strain. A continuous strain loading with a stepped increasing amplitude is subjected to the MEA strain sensor under temperatures of −150 °C, 25 °C, and 800 °C. As shown in Supplementary Fig. 29, at the low temperature range, the sensor can effectively identify a microstrain increment of 1.14 μɛ, and a programmable change in the relative resistance is successfully recorded with high precision for more than seven increments in the strains. Note that the exceptional behavior is well maintained even at a high temperature of 800 °C, manifested by the highly repeatable outputs in the electrical signals when an incremental strain of 1.14 μɛ is loaded to the MEA strain sensor and unloaded back in two cycles (Supplementary Fig. 30). These results indicate that the MoWNb MEA sensor can resolve an ultra-low strain of 1.14 μɛ over a broad temperature range, which is the lowest reported value (Supplementary Table 1) in the literature, demonstrating its capability to accurately discriminate microscale strain change at various temperatures.

We also examine the response time of the MEA sensor, which is crucial for sensors to respond rapidly to external stimuli. There is abrupt jump in the resistance when a small strain of 0.057 μɛ is applied to the sensor, and the resistance promptly recovers to the initial value after unloading the strain (Supplementary Fig. 31). A short response and recovery time of about 34 ms is determined for the MEA sensor, which is one of the lowest values in the literature (Supplementary Table 1). Moreover, the response of the MEA strain sensor to applied strains with different frequencies is also investigated. As shown in Supplementary Fig. 32, there are roughly constant and identical outputs for the sensors with increased strain frequencies from 0.09 to 0.23 Hz, demonstrating their frequency-independent behavior.

We also compare the sensing performance of the MEA strain sensor with the sensor based on Mo, W, and Nb mixture with the composition of nanostructured metallic particles. The XRD pattern reveals three sets of diffraction peaks, which are assigned to the Mo, W, and Nb metals, respectively (Supplementary Fig. 33), confirming the existence and well mixing of these metallic particles. The SEM images demonstrate that the metal particles are in spherical and irregular shapes with a size of about tens of nanometers (Supplementary Fig. 34a). The EDS mappings show that the Mo, W, and Nb nanoparticles distribute separately (Supplementary Fig. 34b), which is completely different from our MEAs with alloying structures. The metal mixture is used to prepare paintable ink with the identical formulation of MEA ink, which is the base for device fabrication. The electrical response of the mixture-based sensor to microstrains is examined by subjecting bending strains from 0 to 258 μɛ. As shown in Supplementary Fig. 35, the mixture-based sensor can respond to the applied strains at a wide temperature range from 25 °C to 900 °C. However, compared to our MEA alloy sensors, the relative change in resistance is much lower. In addition, there is extremely weak output with negligible resistance variation to several microstrains when the temperatures increase to 300 °C, indicating the limited detectable bending strains. Furthermore, the fitting coefficient of determination for the fitted curves is also lower than the MEA alloy sensors, especially at high temperatures, such as 900 °C. The resultant GFs of the mixture-based sensor are at least five times smaller than those of the MEA-based sensors (Supplementary Fig. 36). Note that the GFs are still larger than those of the reported high-temperature strain sensors in the literature14,24,46, verifying the effectiveness of the proposed ink-and-printing strategy on the achievement of high GFs for flexible high-temperature strain sensors.

Different from the conventional high-temperature sensors, the printed MEA sensors are recyclable and reusable due to the trace amount of polymer binders in the ink formulation and the nanostructured shapes. After being tested at high temperatures, the MEAs can be recycled and then redesigned for another ink formulation to expand their application scenario. Supplementary Fig. 37a shows the recycling process of the MEA powders from the printed sensors. The sensors are immersed in ethanol for a few minutes and gently scratched to allow the delamination of the MEA particles from the substrates and re-dispersion in ethanol. After centrifugation and drying, MEA powders are obtained, which could be further reused as raw materials for the preparation of new printable inks and the fabrication of flexible sensors. We have evaluated the crystalline structure and microstructures of the recycled materials. The XRD patterns of the as-prepared MEAs show no significant structural changes after the recycling cycles, whereas four BCC peaks are identified without extra peaks (Supplementary Fig. 37b). In the microscopic level, there are no noticeable morphological changes in the MEAs after five recycling cycles (Supplementary Fig. 37c), indicating that the material integrity is well maintained throughout the recycling process.

We then investigate the sensing performance of the fabricated sensors using recycled MEAs, including resistance variation and strain sensitivity, which should remain consistent with that of the pristine sensors to ensure the precise response to external bending strains. As shown in Supplementary Figs. 38–40, compared to the original outputs, the recycled sensors exhibited almost identical electric response to a maximum strain up to 258 μɛ at various temperature points from −150 °C to 1000 °C. Specifically, the GFs of pristine sensors and recycled sensors with one and five recycling cycles are highly coincident with a slight variation of about 7.4%. It is noteworthy that the behavior is well maintained when the sensor is exposed to cryogenic temperatures down to −150 °C and high temperatures up to 1000 °C, further confirming the integrity of the MEAs nanostructures and the superior sensing performance of the fabricated sensors even after fifth recycling.

As noted, the proposed approach is highly desirable and efficient for allowing the rapid realization of arbitrary patterns over a large area on various surfaces. Based on the MoWNb strain sensor, we design and construct a flexible sensor array comprising four symmetry sensors to evaluate the ability of identifying deformation direction. There are five wired connections with one shared wire connecting the four sensors to reduce the complexity of measurement. A gentle pressure is applied to each sensor (Fig. 3f), and the electrical response of the four sensors is recorded simultaneously. At a high temperature of 500 °C, the results show that there is pronounced variation in resistance when the applied pressure is closest to the strain sensor (Supplementary Fig. 41a). In specific, there a relative change in resistance of −3.6% for sensor A under pressing, while sensors B, C, and D exhibit values of −0.03%, −0.29%, and −0.34%, respectively. In contrast, sensor C shows the largest change in resistance when sensor C is pressed. Similar results are obtained for other sensors under pressing. As shown in Fig. 3g, the spatial mapping clearly reveals this behavior, wherein the sensors closest to the pressing position exhibit a substantial change in resistance. After releasing the pressure stimuli, the sensors remain a relatively smaller change in resistance. Since the sensors are arranged in a rectangular shape with an offset of 90° from each other, the sensor array demonstrates the potential to estimate the unknown direction of the applied pressure even in a high-temperature environment48,65. Note that similar results are also obtained when the sensors operate at room temperature (Supplementary Fig. 41b, c). The relative change in resistance for the sensor arrays working at room temperature is slightly larger than that at 500 °C, which is consistent with the single sensor test.

Integrated sensing system for morphing aircraft status monitoring

Throughout the thorough experiments, we have verified the exceptional sensing performance of the proposed flexible high-temperature strain sensor, as well as the capability of the direct printing approach for the rapid production of highly customizable flexible electronic devices on arbitrary surfaces. As a proof of concept, we directly print sensors on a morphing aircraft to construct a wireless LoRa-based sensing system for the in situ, long-distance, and real-time monitoring of its transformable behaviors and flying status under various extreme environments. The fabrication process of the strain sensor and the integrating procedure comprise the mask printing, wire welding, and system connection, which is consistent with that of the strain sensor in Fig. 1a, b. The fully integrated wireless sensing system is shown in Fig. 4a. The sensors are printed on the curved surfaces of the wings, demonstrating clear and sharp edges. A flexible LoRa module is fixed at the bottom side of the aircraft with a wire connection to the printed sensors. We design a flexible printed circuit board (FPCB) for the electrical measurements, signal processing, and wireless data transmission. Figure 4b shows a block diagram of the wireless sensing system. The collected resistance data is pre-processed in a microcontroller unit, which contains a signal converter and a multichannel analog-to-digital converter (ADC) to convert the resistance signal to voltages and data acquisition. The preprocessed data is then wirelessly transmitted to a user interface through a LoRa connector over a distance of about 2 km and displayed on a computer screen.

a Photographs of the integrated system on a morphing aircraft including printed sensors, wire connections, and a LoRa module. b Block diagram of the wireless sensing system. Low dropout regulator (LDO), Serial Wire Debug (SWD), input/output (I/O), ANT antenna, digital signal processing (DSP), integrated circuits (IC). c Relative change in resistance of the sensing system when the aircraft is under normal morphing for various configurations at −20 °C. The right panel shows the photographs of the aircraft under morphing and the corresponding morphing angle. d Time-frequency domain spectrum and the PSD spectrum of the sensing system under normal morphing. e Relative change in resistance and the calculated PSD values of the sensing system under various morphing angles from 180° to 90°. f Resistance signals obtained by the printed sensor when the aircraft morphs from configuration one to several other conditions, and the corresponding time-frequency analysis diagram. Arrows indicate the timing of the morphing. g Relative change in resistance of the sensing system under vibration with a frequency of about 1 Hz, and a high-temperature environment of 200 °C for >3 h. Insets show the captured vibrational signals at 40 min and 180 min. h Photographs of the wireless sensing system for aircraft status monitoring at a high-temperature smoky environment, and 2 km long-distance data transmission to a computer screen showing the morphing configuration.

Based on the high-performance strain sensor and the integrated wireless sensing system, we first investigate the application in monitoring the morphing configurations of the aircraft in extreme temperature environments. Figure 4c shows the relative change in resistance of the sensing system when the aircraft morphs at various configurations at a low temperature of about −20 °C. Under normal morphing status, the sensing system operated without noticeable hysteresis, and the resistance of the sensor increases immediately when the wings of the aircraft morph between different configurations. A morphing angle (θ), defined as the wing-fuselage angle, is utilized to quantitatively analyze the morphing process. In configuration one, the wing is at flat status, indicating aθ of 180°. As the wings progressively fold (configurations two-four), θ decreases to 150°, 120°, and 90°, respectively. In the mappings of the time-frequency spectrum, there are noticeable variations when the aircraft morphs its configurations, whereas the intensity gradually increases with the increase in θ (Fig. 4d). This behavior is also clearly observed in the power density spectrum. The power spectral density (PSD) of the recorded signals is calculated to indicate the relative power intensity of the signals at various frequencies. There is a significant increase in the PSD during the dynamic and continuous morphing (Fig. 4d), whereas the PSD increases from 22.8 dB/Hz to 51.4 dB/Hz as the aircraft morphs from configuration one to configuration four. Based on the fitted result, there is a linear correlation between PSD and morphing angle, described by the equation: PSD = −0.32θ + 80.1 (dB/Hz) (Fig. 4e). These results indicate that the proposed sensing system is capable of precisely acquiring and monitoring the variation of the morphing configurations in a dynamic and real-time manner, which is expected to improve the adaptability and responsiveness of the aircraft.

Given the superior sensing performance to extremely tiny deformations, our sensing system can enable high sensitivity to differentiate the flying status of the aircraft induced by the partially damaged wings. Notably, the resistance variation of the sensing system is irregular when the aircraft is under abnormal morphing. As shown in Supplementary Fig. 42, the recorded resistance signals for the abnormal morphing are completely different from those of the normal morphing status. There is a significant delay in the resistance variation after morphing the aircraft to various configurations, which is ascribed to the morphing stuck. This is further confirmed in the time-frequency analysis diagram. The signal amplitudes increase hysteretically after the morphing stimuli, and there are signal recessions when the morphing is complete, indicating that the aircraft operates at an abnormal status.

In addition to the operation at low temperature, the sensing system can monitor the morphing status at high temperatures. The resistance variations obtained with the sensing system at about 200 °C and the corresponding time-frequency analysis diagram are shown in Fig. 4f. The resistance signals and the signal amplitudes increase simultaneously with the multiple morphing stimuli. Moreover, the peak values of both signals keep increasing when the aircraft is folding from configuration two to configuration four and the values roughly recover to the original ones after the aircraft refolds to its free status. Notably, the morphing process is highly reversible and repeatable in multiple morphing-recovering cycles, evidenced by the stable outputs in the resistance variation signals and the signal amplitudes (Supplementary Fig. 43), confirming the precise and reliable performance of the integrated sensing system under extreme temperature environment.

We further evaluate the long-term stability and reliability of the sensing system under high-temperature environments. Vibrations with a frequency of about 1 Hz are applied to both the morphing aircraft and the integrated system. The sensor painted on the aircraft wing accurately captures the vibrational signals, evidenced by the regular resistance variations with a peak value of about 2% and a frequency of about 1 Hz throughout the morphing process (Fig. 4g and Supplementary Fig. 44). The aircraft maintains normal morphing under vibration loading, demonstrating system-level robustness and reliability, which can be attributed to the high interfacial adhesion between the sensor and aircraft surface. Moreover, the sensing system operates reliably at 200 °C for over 3 h without fatigue, failure, or damage, further confirming the superior stability and durability under combined thermal and mechanical conditions.

As mentioned, LoRa is a wireless transmission method with longer transmission distances and lower power consumption. In our measurement setup, the transmission distance from the aircraft to the user interface (through a receiving module) reaches 2 km (Fig. 4h), which is expected to be sufficient for practical applications of an unmanned aerial vehicle. The received signals from the receiving module are displayed on a computer screen, wherein there are transient signal variation when the aircraft morphs between different configurations (Fig. 4h and Supplementary Fig. 45). Correspondingly, deformations of the aircraft wings and the specific configuration are displayed on the user interface to indicate the flying status of the aircraft, which provides an effective method for tuning the operation.

Discussion

In summary, we have demonstrated a convenient and effective approach to directly produce arbitrary patterns and flexible sensors on various complex surfaces using a direct printing method. MoWNb MEAs with controllable compositions are synthesized in a gram scale, benefiting the preparation of paintable inks for high-performance flexible electronic devices. The sensing performance of the printed MoWNb MEAs-based flexible sensors is systematically and comprehensively evaluated at both low and high temperatures. The sensors exhibit extremely high GFs (maximum −752.7 at 300 °C) over an ultra-broad temperature regime from −150 °C and 1100 °C, which is superior compared to the reported values in the literature. An extremely low detection limit of 0.57 με is also achieved in the sensor, facilitating the detection of tiny strains. Interestingly, the sensors can be dissolved and reprinted in a recycling process, and the collective sensing performance is well maintained. Furthermore, a flexible sensing system that incorporates a designed sensor unit, an acquisition circuit, and a LoRa module is developed and integrated on the surface of a morphing aircraft, enabling the in-situ and real-time monitoring of the flying status and morphing process of the aircraft at various extreme scenarios. The convenient preparation and the superior performance of the proposed sensors offer an attractive approach for the in-situ sensing of various complex surfaces over an ultra-wide temperature range, which demonstrates great potential in flexing sensing electronics at extreme environments.

Methods

Synthesis of MoWNb nanoparticles

Aqueous-type precursors were prepared separately by dissolving the metal salts of (NH4)6Mo7O24·4H2O, (NH4)10H2(W2O7)6, and C10H5NbO20 into a solvent mixture (water: ethanol = 4:1 (v/v)) with the assistance of magnetic stirring and sonication at room temperature for 0.5 h. The precursor solutions are then mixed well and sonicated for 0.5 h. The weight ratio of these metal precursors is 0.5:0.45:0.3. Then, the prepared solution was dried in an oven at 80 °C for 5 h to obtain film-like precursors. After grinding into powders, the precursors were loaded into a ceramic boat and placed at the center of a tube furnace. Before the sintering process, the furnace was purged with 600 sccm Ar for 10 min to remove any air residual. Afterward, the furnace was ramped to 1000 °C within 1 h and maintained this temperature for 4 h in a mixed atmosphere of H2 (92%)/Ar (8%). Finally, the furnace was naturally cooled down to room temperature, maintaining a high-concentration H2 atmosphere.

Preparation of MoWNb MEAs-based ink

The MoWNb powders were grinded using an agate mortar to obtain fine particles. A viscous cellulose paste was prepared by dissolving ethylene cellulose (5 wt.%) into a mixed solvent including terpilenol and ethanol with a weight ratio of 3:2. Then, 1.0 g of the grinded powder was mixed with 0.2 g of the cellulose paste and sonicated for 10 min to produce a black-colored ink. The viscosity and the drying behavior of the ink could be tailored by adjusting the weight ratio of terpilenol and ethanol in the cellulose paste. In addition, cellulose content in the ink can also be used to adjust the viscosity of the ink. We have prepared several inks with different cellulose contents from 0.27 wt.% to 0.98 wt.%. The adhesion to substrate was tuned by controlling the amount of cellulose in the ink, and a slightly higher amount of cellulose leads to a stronger contact of the MoWNb particles to the applied surfaces.

Patterning process

The prepared MoWNb-MEAs ink was directly deposited on various surfaces, including glass, ceramics, polymers, plastics, and aluminum, through a mask printing or direct writing. In the mask printing process, a polyimide tape was patterned using a laser writing system to form a printing mask and then firmly attached to the target surfaces. The ink was added to one side of the pattern and squeegeed into the mask. Then the mask was peeled off, and the deposited layers on the target surfaces were dried using an infrared light with a temperature of about 120 °C for 10 min. For the direct writing, a flat painting brush was used to directly print the ink on the target surfaces to form arbitrary patterns. The drying process follows the same with that of the mask printing. The thickness and electrical conductivity of the printed layers could be tuned by repeating the printing or writing process several times.

Electrical connection to a wireless LoRa module and system integration

An electrical connection is required for the electrochemical measurement and the integration with the wireless module. A temperature-resistant conductive AgPd paste was used to fix the pins of the fabricated sensors with the connection wires for the construction of an electrical connection between the sensor and the external circuits. To enhance the strength of the connection, an insulation paste was applied to embed the connection wires.

A flexible high-temperature sensing system is designed based on the STM32 microcontroller (STM32F103C8T6) and LoRa remote communication technology. The system provides real-time monitoring of strain data and long-distance wireless data transmission to a central server via LoRa for data analysis and processing. Keil MDK is used as the development environment to write an embedded program in the C language, while Altium Designer software is employed for the schematic and routing design of the FPCB, ensuring signal integrity and anti-interference. The communication interface uses UART serial mode with configured clocks, General Purpose Input/Output, ADC, and other peripherals, achieving the collection, conversion, and processing of strain data. A LoRa module (SX1278) is used to transmit data over long distances. In our experiment, stable data transmission within a range of two kilometers is achieved, and there is a packet loss rate of less than 1%. A customizable interface is designed to display the received data from the LoRa module on a computer screen.

COMSOL simulation

Three-dimensional finite element analysis technique (COMSOL Multiphysics software) is conducted to simulate the bending-induced strain effect of the printed films and the nanoparticles. First, a three-dimensional geometric model of the strain sensor is constructed, including a flexible substrate and a sensing element. The geometric model is meshed with static loading conditions to simulate the deformation under external forces. The parameters of the sensitive material for the strain sensor include elastic modulus (240 GPa), Poisson’s ratio (0.45), and a thermal expansion coefficient of 4.9 × 10−6 K−1. The substrate material has a thermal expansion coefficient of 8 × 10−6 K−1. Appropriate boundary conditions and external loads are set. The distributions of strain and displacement fields of the sensor under strains are obtained through the simulation.

DFT calculation

All the first-principles DFT calculations were performed using the Vienna ab initio Simulation Package. The exchange-correlation energy is treated within the Perdew–Burke–Ernzerhof generalized gradient approximation. The plane-wave basis set with a kinetic energy cutoff of 500 eV was employed. For the geometry optimization and static self-consistent calculations, the Brillouin-zone integrations were conducted using Monkhorst–Pack grids of special points with a separation of 0.03 Å−1. The structure relaxation considering the atomic positions was performed by the conjugate gradient scheme until the maximum force on each atom was less than 10−3 eV/Å, and the total energy was converged to 10−6 eV with the Gaussian smearing method. To ensure the accuracy of DFT calculations, we selected a BCC structure as the primary framework, constructing a model with 52 Mo atoms, 43 W atoms, and 30 Nb atoms to roughly match the experimental atomic ratios. In addition, a rule of random atomic distribution was employed in the modeling process.

Characterizations and measurements

SEM images and the EDS mapping of the synthesized MoWNb powders, printed patterns, and the MoWNb mixture were obtained from a field emission scanning electron microscopy (FESEM, Zeiss). The optical images of the printed patterns were taken through an optical microscope (Nexcope NMM910). Viscosity of the inks is measured using a rheometer (MCR 302e, Anton Paar). XRD patterns were taken on an X-ray diffractometer (Bruker, D8). In-situ SEM images were taken from an FESEM (TESCAN-MIRA) equipped with a tensile and compression module. TEM and HAADF-STEM images and EDX mapping of the MoWNb MEAs were obtained on a field-emission TEM (JEM 2100F with an accelerating voltage of 200 kV). The surface chemistry was studied through XPS with a high-resolution X-ray photoelectron spectrometer (Thermo Fisher Scientific ESCALAB 250Xi). The electrical response of the printed sensors was recorded through a digital multimeter (Keithley 2450). The strain sensing performance at low and high temperatures was evaluated under Ar atmosphere after annealing the sensor at 800 °C to remove polymer residuals. A homemade high precision strain-evaluation system was used, comprising a furnace tube, a step motor, and an alumina holder, wherein the temperature and bending strain could be controlled.

Data availability

The data associated with all simulations and experimental results discussed in the main text of this paper are available. Source data are provided with this paper.

References

Zhong, D. et al. High-speed and large-scale intrinsically stretchable integrated circuits. Nature 627, 313–320 (2024).

Ding, Y. et al. Metal nanowire-based transparent electrode for flexible and stretchable optoelectronic devices. Chem. Soc. Rev. 53, 7784–7827 (2024).

Park, B., Jeong, C., Ok, J. & Kim, T. -i Materials and structural designs toward motion artifact-free bioelectronics. Chem. Rev. 124, 6148–6197 (2024).

Liu, Z. et al. A three-dimensionally architected electronic skin mimicking human mechanosensation. Science 384, 987–994 (2024).

Xu, L. et al. Rapid laser fabrication of indium tin oxide and polymer-derived ceramic composite thin films for high-temperature sensors. J. Colloid Interface Sci. 658, 913–922 (2024).

Wu, C. et al. Exploring the nonlinear piezoresistive effect of 4H-SiC and developing MEMS pressure sensors for extreme environments. Microsyst. Nanoeng. 9, 41 (2023).

Eswarappa Prameela, S. et al. Materials for extreme environments. Nat. Rev. Mater. 8, 81–88 (2023).

Wu, S. et al. Structural design and fabrication of multifunctional nanocarbon materials for extreme environmental applications. Adv. Mater. 34, 2201046 (2022).

Kim, S. D. et al. Poly(amide-imide) materials for transparent and flexible displays. Sci. Adv. 4, eaau1956 (2018).

Li, W. et al. Large-scale ultra-robust MoS2 patterns directly synthesized on polymer substrate for flexible sensing electronics. Adv. Mater. 35, 2207447 (2023).

Li, W. et al. Microsecond-scale transient thermal sensing enabled by flexible Mo1-xWxS2 alloys. Research 7, 0452 (2024).

Wu, C. et al. TiB₂/SiCN thin-film strain gauges fabricated by direct writing for high-temperature application. IEEE Sens. J. 22, 11517–11525 (2022).

Wu, C. et al. Ultrafast high-temperature sintering of polymer-derived ceramic nanocomposites for high-temperature thin-film sensors. Chem. Eng. J. 463, 142518 (2023).

Yang, M. et al. A strain-temperature integrated polymer-derived SiCN ceramic high temperature sensor with wide-range and ultra-short response time. Adv. Funct. Mater. 34, 2400400 (2024).

Yetim, T. et al. Synthesis and characterization of wear and corrosion resistant Ni-doped Al2O3 nanocomposite ceramic coatings by sol-gel method. Surf. Coat. Technol. 444, 128659 (2022).

Attarzadeh, N., Molaei, M., Babaei, K. & Fattah-alhosseini, A. New promising ceramic coatings for corrosion and wear protection of steels: a review. Surf. Interfaces 23, 100997 (2021).

Wu, C. et al. Multilayer co-sintered Pt thin-film strain gauge for high-temperature applications. Surf. Coat. Technol. 459, 129380 (2023).

Ling, S. et al. A novel semiconductor piezoresistive thin-film strain gauge with high sensitivity. IEEE Sens. J. 24, 13914–13924 (2024).

Li, Y., Zhou, P., Qi, Y. & Zhang, T. All-inorganic flexible high-temperature strain sensor based on SrRuO3/muscovite heteroepitaxy. J. Am. Ceram. Soc. 105, 2038–2045 (2022).

Xu, L. et al. In situ laser fabrication of polymer-derived ceramic composite thin-film sensors for harsh environments. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 14, 12652–12661 (2022).

Tan, C. et al. A high performance wearable strain sensor with advanced thermal management for motion monitoring. Nat. Commun. 11, 3530 (2020).

Wu, C. et al. Innovative coaxial high-temperature thin-film sensor with core–shell structure surpassing traditional multilayer films. Rare Met. 43, 3854–3867 (2024).

Zhao, Y., Li, Y., Wu, Y., Ding, G. & Zhang, C. High-temperature PdCr thin-film strain gauge with high gauge factor based on cavity structure. IEEE Sens. J. 24, 9573–9584 (2024).

Wu, C. et al. AgPd thin-film strain gauges fabricated by direct writing for high-temperature application. IEEE Sens. J. 22, 22473–22478 (2022).

Liu, H. et al. High temperature static and dynamic strain response of PdCr thin film strain gauge prepared on Ni-based superalloy. Sens. Actuators, A 298, 111571 (2019).

Lee, C.-Y., Shen, C.-C., Lee, S.-J., Chiu, C.-W. & Lin, H.-T. Real-time microscopic monitoring of temperature and strain on the surface of magnesium hydrogen storage tank by high temperature resistant flexible integrated microsensor. Int. J. Hydrog. Energy 47, 12815–12821 (2022).

Rahman, M. T., Moser, R., Zbib, H. M., Ramana, C. V. & Panat, R. 3D printed high performance strain sensors for high temperature applications. J. Appl. Phys. 123, 024501 (2018).

Lichtenwalner, D. J., Hydrick, A. E. & Kingon, A. I. Flexible thin film temperature and strain sensor array utilizing a novel sensing concept. Sens. Actuators, A 135, 593–597 (2007).

Kim, L. et al. Distinguishing elements at the sub-nanometer scale on the surface of a high entropy alloy. Adv. Mater. 36, 2402442 (2024).

Han, L. et al. Multifunctional high-entropy materials. Nat. Rev. Mater. 9, 846–865 (2024).

Tang, Q. et al. High-entropy thermoelectric materials. Joule 8, 1641–1666 (2024).

Cook, D. H. et al. Kink bands promote exceptional fracture resistance in a NbTaTiHf refractory medium-entropy alloy. Science 384, 178–184 (2024).

Li, M. et al. High-entropy alloy electrocatalysts go to (sub-)nanoscale. Sci. Adv. 10, eadn2877 (2024).

Huang, K. et al. Lattice-disordered high-entropy alloy engineered by thermal dezincification for improved catalytic hydrogen evolution reaction. Adv. Mater. 36, 2304867 (2024).

Uporov, S. A. et al. High entropy alloys as strain-sensitive materials. Intermetallics 170, 108334 (2024).

Rajendrachari, S., Adimule, V., Gulen, M., Khosravi, F. & Somashekharappa, K. K. Synthesis and characterization of high entropy alloy 23Fe-21Cr-18Ni-20Ti-18Mn for electrochemical sensor applications. Materials 15, 7591 (2022).

Feng, X. et al. Unique multi-mode nanoporous CoCrFeNiAl high entropy alloy for hydrogen peroxide sensor. Electrochim. Acta 503, 144855 (2024).

Lv, C.-L. et al. Self-supported PtPdMnCoFe high-entropy alloy with nanochain-like internetworks for ultrasensitive electrochemical immunoassay of biomarker. Sens. Actuators, B 401, 135041 (2024).

Gludovatz, B. et al. A fracture-resistant high-entropy alloy for cryogenic applications. Science 345, 1153–1158 (2014).

Liu, D. et al. Exceptional fracture toughness of CrCoNi-based medium- and high-entropy alloys at 20 kelvin. Science 378, 978–983 (2022).

Ma, Y. et al. A one-step fabrication of soft-magnetic high entropy alloy fiber with excellent strength and flexibility. Nat. Commun. 15, 10549 (2024).

Mayandi, J. et al. Thin films made by reactive sputtering of high entropy alloy FeCoNiCuGe: optical, electrical and structural properties. Thin Solid Films 744, 139083 (2022).

Lin, F. et al. ZrB2/SiCN thin-film strain gauges for in-situ strain detection of hot components. Micromachines 13, 1467 (2022).

Zeng, Y. et al. Thermally conductive reduced graphene oxide thin films for extreme temperature sensors. Adv. Funct. Mater. 29, 1901388 (2019).

Liu, Z. et al. Flexible temperature sensor with high sensitivity ranging from liquid nitrogen temperature to 1200 °C. Int. J. Extrem. Manuf. 5, 015601 (2023).

Xu, L. et al. Rapid printing of high-temperature polymer-derived ceramic composite thin-film thermistor with laser pyrolysis. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 15, 9996–10005 (2023).

Peng, Z. et al. Flexible copper-based thermistors fabricated by laser direct writing for low-temperature sensing. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 16, 10496–10507 (2024).

Park, S. et al. Layer-selective synthesis of MoS2 and WS2 structures under ambient conditions for customized electronics. ACS Nano 14, 8485–8494 (2020).

Cai, Y. et al. Graphdiyne-based nanofilms for compliant on-skin sensing. ACS Nano 16, 16677–16689 (2022).

Liu, Y. et al. Ag–thiolate interactions to enable an ultrasensitive and stretchable MXene strain sensor with high temporospatial resolution. Nat. Commun. 15, 5354 (2024).

Sun, Y. et al. Ultrafine-grained refractory high-entropy alloy with oxygen control and high mechanical performance. J. Mater. Sci. Technol. 215, 45–57 (2025).

Cao, G. et al. Liquid metal for high-entropy alloy nanoparticles synthesis. Nature 619, 73–77 (2023).

Pancotti, A. et al. Surface characterization of NbO islands formed on Nb(100) by X-Ray Photoelectron Diffraction. Top. Catal. 61, 784–791 (2018).

Schmid, P. et al. Electro-mechanical properties of multilayered aluminum nitride and platinum thin films at high temperatures. Sens. Actuators, A 293, 128–135 (2019).

Xiang, S., Chen, S., Yao, M., Zheng, F. & Lu, Q. Strain sensor based on a flexible polyimide ionogel for application in high- and low-temperature environments. J. Mater. Chem. C. 7, 9625–9632 (2019).

Liu, J., Weng, L., Zhang, X., Wang, X. & Wu, Z. Intrinsic fiber reinforced polyimide aerogel flexible strain sensor applied in high-temperature environment. Nano Res. 18, 94907302 (2025).

Yuan, T. et al. Synergistic structural construction of strain sensors with low baseline drift and high sensitivity for continuous dynamic monitoring. Nano Lett. 25, 4969–4978 (2025).

Wang, J. et al. Ultrasensitive electrospinning fibrous strain sensor with synergistic conductive network for human motion monitoring and human-computer interaction. J. Mater. Sci. Technol. 213, 213–222 (2025).

He, J. et al. High-temperature strain sensor based on sapphire fiber Bragg grating. Opt. Lett. 49, 446–449 (2024).

Bose, A. K. et al. Screen-printed strain gauge for micro-strain detection applications. IEEE Sens. J. 20, 12652–12660 (2020).

Schmid, P. et al. Impact of adhesion promoters and sputter parameters on the electro-mechanical properties of Pt thin films at high temperatures. Sens. Actuators, A 285, 149–157 (2019).

Huang, J., Wang, Y., Dong, H. & Tan, Q. A high-temperature strain dual reference sensor with a self-compensating structure. IEEE Sens. J. 25, 19386–19393 (2025).

Li, M. et al. Wearable and robust polyimide hydrogel fiber textiles for strain sensors. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 13, 43323–43332 (2021).

Saeidi-Javash, M. et al. All-printed MXene–Graphene nanosheet-based bimodal sensors for simultaneous strain and temperature sensing. ACS Appl. Electron. Mater. 3, 2341–2348 (2021).

Li, S. et al. Monitoring blood pressure and cardiac function without positioning via a deep learning–assisted strain sensor array. Sci. Adv. 9, eadh0615 (2023).

Zou, S., Wang, Y., Li, D., Zhang, Y. & Cai, G. Facile and scalable fabrication of stretchable flame-resistant yarn for temperature monitoring and strain sensing. Chem. Eng. J. 450, 138465 (2022).

Yang, C. et al. A flexible strain sensor of Ba(Ti, Nb)O3/Mica with a broad working temperature range. Adv. Mater. Technol. 4, 1900578 (2019).

Dou, S. et al. High-temperature high-sensitivity AlN-on-SOI Lamb wave resonant strain sensor. AIP Adv. 8, 065315 (2018).

Sun, T. et al. Bioinspired, ultra-sensitive flexible strain sensor based on ceramic fiber paper with superhydrophobic and high-temperature-resistant properties. Adv. Mater. Technol. 8, 2200972 (2023).

Xu, L. et al. High-temperature thin-film strain sensors with low temperature coefficient of resistance and high sensitivity via direct ink writing. Nanotechnol. Precis. Eng. 8, 013001 (2024).

Zhang, P. et al. Measurements of polymer-derived ceramic thin-film strain gauges at high temperatures. IEEE Sens. J. 24, 34127–34133 (2024).

Hai, Z. et al. Printable silicate and RuO2 composite with wide-range linear PTC for high-temperature sensors. Ceram. Int. 50, 30776–30784 (2024).

Acknowledgements

This work was financially supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (No. 62288102, 62371397, 62304182, and 62471396), the Fundamental Research Funds for the Central Universities, the Young Talent Fund of Xi’an Association for Science and Technology (No. 959202413089), and Open Test Funding Project from Analytical & Testing Center of Northwestern Polytechnical University (No. 2023T008). We would like to thank Dr. Yan Wang from the Analytical & Testing Center of Northwestern Polytechnical University for in-situ SEM strain test. We would like to thank Prof. Lei Li from the Institute of Flexible Electronics of Northwestern Polytechnical University for his DFT calculations.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Weiwei Li and Yingzhe Li contributed equally to this work. W.L., L.Z., X.W. and W.H. supervised the project. W.L. and Y.L. conceived the idea. W.L. and Y.Z. prepared the precursors. W.L., Y.Z., K.W. and R.M. annealed the precursors in quartz furnace. M.X. analyzed XPS and TEM data. W.L., Y.Z. and Y.C. printed the sensors. Y.L., Y.S., W.L. and S.D. conducted the strain sensing tests. Y.L. and Y.Z. conducted tests on aircraft. Y.L. performed COLMOSOL simulations. M.X. draw the schematics and illustrations. W.L., Y.L., M.X., X.W. and L.Z. wrote the manuscript. All authors commented on the manuscript.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Peer review

Peer review information

Nature Communications thanks Jong-Woong Kim, and the other, anonymous, reviewer(s) for their contribution to the peer review of this work. A peer review file is available.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Source data

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Li, W., Li, Y., Xu, M. et al. Highly customizable, ultrawide-temperature free-form flexible sensing electronic systems based on medium-entropy alloy paintings. Nat Commun 16, 7351 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-025-62100-6

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-025-62100-6