Abstract

Cholesterol and lipid unsaturation underlie a balance of opposing forces that features prominently in adaptive cell responses to diet and environmental cues. These competing factors have resulted in contradictory observations of membrane elasticity across different measurement scales, requiring chemical specificity to explain incompatible structural and elastic effects. Here, we demonstrate that – unlike macroscopic observations – lipid membranes exhibit a unified elastic behavior in the mesoscopic regime between molecular and macroscopic dimensions. Using nuclear spin techniques and computational analysis, we find that mesoscopic bending moduli follow a universal dependence on the lipid packing density regardless of cholesterol content, lipid unsaturation, or temperature. Our observations reveal that compositional complexity can be explained by simple biophysical laws that directly map membrane elasticity to molecular packing associated with biological function, curvature transformations, and protein interactions. The obtained scaling laws closely align with theoretical predictions based on conformational chain entropy and elastic stress fields. These findings provide unique insights into the membrane design rules optimized by nature and unlock predictive capabilities for guiding the functional performance of lipid-based materials in synthetic biology and real-world applications.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Cell membranes are a remarkable class of molecular assemblies that have evolved to perform and regulate biological processes with unparalleled efficiency and precision—features that scientists and engineers strive to emulate. Membranes primarily composed of lipids and sterols initially served as scaffolds for protocells but gradually evolved to enable the ascent of complex cellular life forms1,2,3. What is more, cell membranes constantly adapt to external cues by tuning their lipidome to maintain biological function, a phenomenon known as homeostasis4,5,6. Recent investigations have revealed that such adaptive remodeling is largely regulated through lipid packing density (described by the area per lipid)7. For instance, lipidomic analyses of cultured cells show that membrane compositional responses to dietary uptake, growth conditions, and environmental factors often involve changes in cholesterol and lipid unsaturation which have opposite effects on lipid packing8,9,10. Similar responses have been observed in multicellular organisms including marine invertebrates exposed to extreme hydrostatic pressure as well as mammals such as arctic reindeer, whose extremities feature high concentrations of unsaturated lipids to conserve membrane function at low temperatures11,12. In addition, different ratios of unsaturated lipids and cholesterol have been detected in various parts of the brain and in synaptic vesicles, pointing to an important role in cognitive and neural functions13,14.

To begin to understand how lipid packing informs the physical rules underlying cellular adaptation, we directed our attention to membrane elasticity as an allosteric regulator of biological function15,16,17. Recent studies have shown that changes in membrane elasticity significantly impact protein expression and folding, consequently influencing biological activity and the design of cell mimetics18. These findings agree with earlier studies of rhodopsin and ion channels reporting variations in activity and lifetime with membrane stiffness19,20. Similarly, changes in lipid packing play a critical role in nanoscopic membrane deformations and localization of curvature sensing proteins21,22,23. Nonetheless, contradictory experimental reports of membrane elasticity with variations in cholesterol and lipid unsaturation continue to present a significant challenge to unification of biophysical principles correlating lipid order with membrane elastic properties.

For example, while cholesterol is widely accepted to cause tighter lipid packing across membranes with saturated and unsaturated lipids, its effects on the membranes' bending moduli have been found to vary with lipid unsaturation and with the length and time scales of observation24,25,26. Specifically, unsaturated lipid membranes have been reported to exhibit a null or softening effect by cholesterol via techniques probing membrane fluctuations on micro- and millisecond scales, referred to here as macroscopic scales (e.g., fluorescence spectroscopy, diffuse X-ray scattering)25,26. Yet, these membranes show nontrivial stiffening when measured by techniques sensitive to mesoscopic dynamics on sub-μm and sub-μs scales (e.g., neutron spin echo spectroscopy, solid-state 2H NMR spectroscopy)24. In contrast, saturated lipid membranes show cholesterol-induced stiffening in both the mesoscopic and macroscopic regimes. Molecular dynamics (MD) simulations suggest that the observed differences are caused by conformational (local, fast) and diffusional (long-range, slow) dynamic modes, which can result in distinct emergent elastic properties depending on the accessible spatiotemporal scales of measurement techniques24,27. Given the immense diversity of cellular lipidomes, the ability to distinguish hierarchical dynamics and establish generalized biophysical laws of membrane elasticity is pivotal to understanding biological processes and replicating them in ongoing pursuits of lifelike artificial cells. This is particularly important on mesoscopic scales (sub-μm and sub-μs) which remain underexplored despite their overlap with protein conformational transitions17,28.

In this work, we examine the interdependence of membrane packing and elastic moduli for various lipid and cholesterol compositions using nuclear spin techniques and MD simulations that bridge the gap between lipid chain conformations and emergent membrane dynamics. Specifically, we utilize neutron spin-echo (NSE) spectroscopy to access bending fluctuations in the ns regime and solid-state 2H NMR spectroscopy to measure segmental chain relaxations with correlation times in the ps to ns range. Findings from both methods are used to determine the mesoscopic bending moduli across different membrane compositions and are subsequently mapped to lipid packing densities obtained by small-angle X-ray and neutron scattering (SAXS/SANS). Our experimental results, corroborated by MD simulations, reveal a unified dependence of the bending moduli on the average area per lipid, demonstrating a clear correspondence of membrane material properties to molecular order regardless of cholesterol content or lipid chain unsaturation. The obtained structure-property relations indicate that mesoscopic elasticity is predominantly dictated by conformational chain entropy, in agreement with theoretical predictions. Our findings thus present untapped opportunities for understanding adaptive cell responses and developing synthetic lipid membranes with tunable functionality.

Results

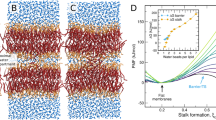

Cholesterol induces membrane thickening and tighter lipid packing

To compare the response of structurally different membranes to cholesterol, we investigated five phosphatidylcholine (PC) lipids ranging from fully saturated lipids (zero double bonds in the acyl chains) to mono- and polyunsaturated lipids with up to 6 double bonds (see Fig. 1a for lipid structures and abbreviations). The choice of lipids was guided by optimal diversification in lipid chain structures and membrane compositions to establish generalized scaling relations over a wide range of packing densities. Each lipid type was mixed with varying molar ratios of cholesterol. Structural membrane changes were measured by SAXS/SANS from unilamellar liposomal suspensions (Fig. 1b), solid-state 2H NMR lineshapes from multilamellar dispersions (Fig. 1c), and atomistic MD simulations of in silico membrane models. The fitting of the SAXS/SANS data (Supplementary Fig. 2, Supplementary Table 2) showed a monotonic increase in the total membrane thickness, \({D}_{{{{\rm{B}}}}}\), with increasing cholesterol content regardless of the degree of chain unsaturation (Fig. 1d). These observations are consistent with the increase in quadrupolar splitting observed in the 2H NMR lineshapes (Fig. 1c and Supplementary Fig. 8) indicating membrane thickening29. Similar trends for cholesterol-induced membrane thickening were observed in MD simulations (Supplementary Table 5).

a Chemical structures of the different phosphatidylcholine (PC) lipids used in this study, listed in the order of increasing chain unsaturation described in terms of the double bonds in the acyl chains. These include 1,2-dimyristoyl-sn-glycero-3-phosphocholine (DMPC), 1-palmitoyl-2-oleoyl-sn-glycero-3-phosphocholine (POPC), 1,2-dioleoyl-sn-glycero-3-phosphocholine (DOPC), 1-palmitoyl-2-linoleoyl-sn-glycero-3-phosphocholine (PLPC), and 1-stearoyl-2-docosahexaenoyl-sn-glycero-3-phosphocholine (SDPC). The nomenclature X:Y represents the number of carbon atoms, X, and the number of double bonds, Y, in each acyl chain. b Representative SAXS data of POPC liposomes, as a function of the wavevector transfer \({{{Q}}}\), with cholesterol contents of 0, 20, and 35 mol%. Here, the wavevector transfer is defined as \({{ Q}}={{4}}{{\pi }}\,{{\sin }}\,{{\theta }}/{{\lambda }}\), where \({{\theta }}\) is half the scattering angle and \({{\lambda }}\) is the X-ray (or neutron) wavelength. Data are vertically offset for better visualization. Fits to the data (solid lines), using the scattering model described in the SI, yielded the membrane structural parameters reported in (d) and (e). c Representative solid-state 2H NMR lineshapes of multilamellar dispersions of POPC show an increase in the quadrupolar splittings, indicating greater membrane thickness with increasing cholesterol content in agreement with conclusions from SAXS/SANS studies. d, e Fit results of scattering data show an increase in the total membrane thickness, \({{{ D}}}_{{{{\rm{B}}}}}\), and a corresponding decrease in the area per lipid, \({A}_{{\rm{L}}}\), with greater cholesterol mole fraction for all studied membranes. The observed trends in \({A}_{{\rm{L}}}\) are closely replicated by atomistic molecular dynamics (MD) simulations, as shown in (f). Note that all membranes were studied in the fluid phase. All experimental and computational studies were conducted at 25 °C, except for DMPC samples which were studied at 44 °C (and 30 °C, SI) to ensure membrane fluidity. Error bars represent ± SD from the mean value or as described in the SI for simulation results. Source data are provided as a Source Data file.

For all the PC lipids investigated, the measured increase in membrane thickness corresponded with a decrease in the area per lipid \({A}_{{{{\rm{L}}}}}\) (Fig. 1e, f), consistent with the condensing effect of cholesterol in fluid membranes30. Notably, our SAXS/SANS results showed that cholesterol exhibited the strongest condensing effect in saturated DMPC membranes, measured at 30 °C (i.e., 6 °C above the gel-to-fluid transition, see Supplementary Fig. 3). Upon heating to 44 °C (i.e., further into the fluid phase), DMPC membranes showed larger \({A}_{{{{\rm{L}}}}}\) values, as expected31. In unsaturated lipid membranes, we observed a gradual increase in \({A}_{{{{\rm{L}}}}}\) with unsaturation, consistent with greater conformational freedom of the lipid chains. The relative trend of larger \({A}_{{{{\rm{L}}}}}\) with the number of double bonds in the lipid chains persisted across all studied membranes at corresponding molar ratios of cholesterol.

The condensing effect of cholesterol on PC lipid membranes was also evident in solid-state 2H NMR measurements of the segmental order parameter \({S}_{{{{\rm{CD}}}}}^{(i)}\) versus the carbon index (i) (Supplementary Fig. 8). The spectra showed an increase in the plateau region for low carbon indices (i.e., carbon atoms closest to the lipid headgroup) with additional cholesterol, indicating higher \({S}_{{{{\rm{CD}}}}}\) values that are associated with denser packing29. Comparison of the \({S}_{{{{\rm{CD}}}}}\) plateau values across DMPC, POPC, and DOPC membranes revealed that saturated DMPC membranes exhibited the highest \({S}_{{{{\rm{CD}}}}}\) values followed by POPC and DOPC at identical cholesterol content, as demonstrated by SAXS/SANS and MD simulations. The measured \({S}_{{{{\rm{CD}}}}}^{(i)}\) profiles closely tracked those obtained from theoretical calculations of lipid chain conformations32.

Cholesterol stiffens saturated and unsaturated lipid membranes

To directly probe mesoscopic membrane elasticity, we utilized neutron spin-echo (NSE) spectroscopy on unilamellar liposomal suspensions. These measurements access membrane thermal fluctuations in the form of short-range bending undulations over relatively short time scales33. In this study, the probed time scales were in the range of ~ 1–100 ns, and the length scales were in the range of ~ 7–23 nm. For liposomal samples with diameters of ~ 100 nm, the wavelength of the accessible fluctuation modes is significantly smaller than the liposome’s circumference; hence, the measured dynamics correspond to local bending fluctuations. Our model-free analysis of the NSE relaxation spectra revealed clear qualitative differences in membrane dynamics with changes in cholesterol content and lipid chain unsaturation. We note that slower relaxations in NSE spectra signify membranes that are less dynamic, which we attribute to membrane stiffening. As such, our data revealed that the addition of cholesterol results in slower bending relaxations in all studied membranes (Supplementary Fig. 4), indicative of cholesterol-mediated stiffening. Comparison of the relaxations across membranes with varying degrees of chain unsaturation showed that the cholesterol effect on bending fluctuations is most pronounced in saturated DMPC membranes, becoming gradually weaker with increasing lipid chain unsaturation (Fig. 2a and Supplementary Fig. 4)—an observation that we correlate later with changes in packing density and chain conformations following the molecular theory of Szleifer et al.34.

a NSE bending fluctuation spectra of saturated DMPC membranes and polyunsaturated SDPC membranes with 0 and 35 mol% cholesterol show steeper decays in the latter—indicative of softer membranes. With the addition of cholesterol, SDPC membranes exhibit less pronounced changes in bending relaxations, implying a weaker stiffening effect of cholesterol in polyunsaturated lipid membranes. b All studied unilamellar liposomal systems show an increase in the bending modulus \({\kappa }\) with additional cholesterol content, signifying membrane stiffening. Cholesterol-induced stiffening effects are most pronounced in saturated DMPC membranes and become weaker with increasing lipid chain unsaturation. c Analysis of splay fluctuations in MD simulations replicate the experimentally observed trends in \({\kappa }\). d, e Plots of measured and simulated \({{\kappa }}\) values, normalized against \({{{\kappa }}}_{{{0}}}\) of the corresponding cholesterol-free membrane, show almost identical scaling with \({{{A}}}_{{{\rm{L}}}}\). Data marked by (*) in panel d correspond to liposomal DOPC membranes extruded through 50- and 100-nm pores, as taken from Chakraborty et al.24 Data marked by (*) in panel (e) correspond to simulation results from the same reference. All samples are reported at 25 °C except for DMPC at 30 °C and 44 °C. Error bars represent ± SD from the mean value or as described in the SI for simulation results. Source data are provided as a Source Data file.

Quantitative analysis of the NSE relaxation spectra using standard models of bending fluctuations35,36 yielded the bending modulus \(\kappa\) for different membrane compositions, as described in the SI. The bending moduli (Fig. 2b and Supplementary Table 3) exhibited the same relative trends in cholesterol-induced stiffening deduced from the model-free observations. Specifically, we found the largest change in \(\kappa\) for saturated DMPC membranes with up to a ~ 3.3-fold increase for 35 mol% cholesterol (at 44 °C), compared to cholesterol-free DMPC membranes. This relative increase became gradually smaller with greater chain unsaturation, with a ~ 2.3-fold increase in mono- and di-unsaturated membranes (i.e., POPC, DOPC, and PLPC) and ~ 1.7-fold increase in polyunsaturated SDPC membranes. These findings are in close agreement with the \(\kappa\) values calculated by splay fluctuation analysis of our MD simulation trajectories (Fig. 2c and Supplementary Table 5), referred to here as MD-Splay simulations37,38.

As might be expected, even in the absence of cholesterol, the bending moduli measured by NSE showed a steady decrease in \(\kappa\) with greater lipid chain unsaturation, from \(\kappa=\left(28.1\pm 4.4\right){k}_{{{{\rm{B}}}}}T\) for fluid DMPC membranes (at 44 °C) to \(\left(23.4\pm 3.8\right){k}_{{{{\rm{B}}}}}T\) for POPC, \(\left(20.4\pm 2.5\right){k}_{{{{\rm{B}}}}}T\) for DOPC, \(\left(12.8\pm 0.8\right){k}_{{{{\rm{B}}}}}T\) for PLPC, and lastly \(\left(12.7\pm 0.8\right){k}_{{{{\rm{B}}}}}T\) for SDPC. These findings (shown in Supplementary Fig. 7) are in excellent accord with published simulation results38,39. Interestingly, DOPC and PLPC membranes have the same degree of lipid chain unsaturation (i.e., two double bonds), with one double bond in each of the sn-1 and sn-2 acyl chains of DOPC (symmetric chains) and two double bonds in the sn-2 acyl chain of PLPC (asymmetric chains). Yet, the two systems have distinct bending rigidities with PLPC membranes being significantly softer than DOPC membranes. Evidently this finding implies that the location of the double bonds has a more pronounced effect on the bending rigidity than the total number of double bonds. These observations are consistent with recent NSE studies showing that membranes with lipid chain asymmetry are softer and more dynamic than their symmetric lipid counterparts40. Our findings are also consistent with predictions of mixed surfactant membranes41, elucidating that surfactants with different chain lengths (as is the case in PLPC) are softer than those with identical chains (like DOPC)—analogous to co-surfactant softening42,43,44.

To further assess the effect of temperature on the bending modulus, we conducted additional NSE studies of fluid DMPC membranes at 30 °C. As expected, DMPC membranes showed a higher bending modulus, \(\kappa=\left(43.7\pm 7.5\right){k}_{{{{\rm{B}}}}}T\) at the lower (30 °C) temperature, compared to \(\kappa=\left(28.1\pm 4.4\right){k}_{{{{\rm{B}}}}}T\) at 44 °C, similar to observations in previous work35,45. Likewise, our NSE measurements showed that higher bending moduli persisted in DMPC-cholesterol membranes at 30 °C, compared to the same membranes at 44 °C (see Supplementary Table 3).

Mesoscopic bending moduli scale with lipid packing

Our current NSE data did not show a consistent dependence of \(\kappa\) on membrane thickness \({D}_{{{{\rm{B}}}}}\) (see Supplementary Fig. 7), unlike earlier studies of saturated and monounsaturated PC lipid membranes46,47. In contrast, we found that membranes with approximately the same thickness—but with different area per lipid—exhibited distinct bending moduli. For instance, PLPC membranes have a similar thickness as SDPC or DMPC (44 °C) membranes containing 20 mol% cholesterol, with \({D}_{{{{\rm{B}}}}}=\left(39.32\pm 0.03\right)\;{{{\text{\AA}}}}\), \(\left(39.56\pm 0.08\right)\;{{{\text{\AA }}}}\), and \(\left(40.27\pm 0.94\right)\;{{{\text{\AA }}}}\) respectively (Supplementary Table 2). However, they exhibit significantly different \({A}_{{{{\rm{L}}}}}\) values of \(\left(62.85\pm 0.05\right)\;{{{{\text{\AA }}}}}^{2}\), \(\left(60.69\pm 0.11\right)\;{{{{\text{\AA }}}}}^{2}\), and \(\left(49.86\pm 0.36\right)\;{{{{\text{\AA }}}}}^{2}\). If one assumes that the bending rigidity of lipid membranes is equivalent to that of a continuum elastic sheet and that they are similarly compressible, then based on thickness alone these membranes should have similar bending moduli. In comparison, our studies revealed dramatic differences in the measured elastic moduli, with \(\kappa=\left(12.8\pm 0.8\right){k}_{{{{\rm{B}}}}}T\), \(\left(17.3\pm 1.7\right){k}_{{{{\rm{B}}}}}T\), and \(\left(46.7\pm 8.4\right){k}_{{{{\rm{B}}}}}T\) respectively (Supplementary Table 3). This finding implies that the mesoscopic bending rigidity of lipid membranes is not solely determined by the membrane thickness, but rather depends on the chain packing density, as predicted by theories of molecular self-assembly and conformational chain statistics32.

Indeed, when we compared the NSE-measured \(\kappa\) values for each membrane composition against its corresponding area per lipid, \({A}_{{{{\rm{L}}}}}\), we found a well-defined inverse relation of \(\kappa\) vs. \({A}_{{{{\rm{L}}}}}\) across all studied membranes (see Supplementary Fig. 7). The stiffening effects of cholesterol were further elucidated by inspecting the reduced bending modulus, \(\kappa /{\kappa }_{0}\), obtained by normalizing \(\kappa\) of the cholesterol-rich lipid membranes against \({\kappa }_{0}\) of the corresponding cholesterol-free membrane. By doing so, we eliminated variations in \({\kappa }_{0}\) arising from lipid chain unsaturation and determined the relative changes induced by cholesterol by normalizing all membranes to the same initial reduced bending rigidity (i.e., \(\kappa /{\kappa }_{0}=1\)). The use of reduced variables was also necessary for comparing the bending moduli obtained by different experimental techniques and with various membrane geometries. As an example, we have previously shown that liposomal membranes with different curvatures (dictated by liposomal size) exhibit variations in their measured \(\kappa\) while their reduced bending moduli, \(\kappa /{\kappa }_{0}\), show identical trends within experimental error24. Likewise, bending moduli obtained by NSE for unilamellar liposomal suspensions and by solid-state 2H NMR for multilamellar dispersions (reported in Supplementary Tables 3, 4) have different absolute values but show consistent changes in \(\kappa /{\kappa }_{0}\), as discussed below. In such a representation, our NSE data revealed that \(\kappa /{\kappa }_{0}\) scales as \({A}_{{{{\rm{L}}}}}^{-6.68\pm 0.47}\) (Fig. 2d). Similar results were observed in all-atom MD simulations analyzed using the splay-fluctuations method (Fig. 2e).

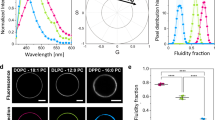

Bending moduli from segmental relaxations follow common scaling laws

To investigate the role of segmental chain dynamics in the NSE-obtained trends of bending moduli, we utilized complementary solid-state 2H NMR relaxation studies on multilamellar dispersions of DMPC, POPC, and DOPC membranes. The membrane elasticity measured by NMR emanates from the dynamics of the C–H bonds along the lipid chains by sampling their orientational fluctuations relative to the membrane normal29,48. Notably, segmental reorientations have correlation times in the ps–ns regime (complementing the time scales accessed by NSE). However, the Fourier transform of the fluctuation autocorrelation function yields spectral densities with ms−1 relaxation rates that can be measured experimentally49. Here, we used deuterium spin labeling along the saturated acyl chains of either intrinsic or probe lipids to relate membrane elasticity to atomistically resolved segmental chain dynamics obtained from the measured relaxation spectra29,50. Following an initial perturbation of the 2H nuclear spins away from their equilibrium state, the time-resolved recovery of the magnetization (Supplementary Fig. 9) enabled experimental observations of the spin-lattice relaxation rates, \({R}_{1{{{\rm{Z}}}}}^{(i)}\), at the carbon atoms along the deuterated acyl chain, with index \(\left(i\right)\) starting at the lipid headgroup and increasing along the chain. As we have shown in the past, the relaxation rates of chain segments within the bilayer core (i \(\sim\) 7–16) often follow a square-law dependence on the corresponding \({S}_{{{{\rm{CD}}}}}^{(i)}\) segmental order parameter values that is attributed to collective order-director fluctuations51. Therefore, plots of \({R}_{1{{{\rm{Z}}}}}^{(i)}\) vs. \({|{S}_{{{{\rm{CD}}}}}^{(i)}|}^{2}\) typically exhibit a linear behavior for the bilayer interior with a slope that is inversely related to membrane stiffness50. Our experiments showed that this behavior persisted across the three membrane types we examined and for all molar ratios of cholesterol, with a gradual decrease in the slope indicating membrane stiffening with increasing cholesterol content (Fig. 3a, Supplementary Fig. 9). Notably, comparison of 2H NMR results of membranes with the same cholesterol molar ratio showed that it has the strongest stiffening effect (i.e., largest slope decrease) in DMPC membranes followed by POPC and DOPC membranes respectively (Fig. 3b), in excellent agreement with our NSE studies and splay analysis of MD simulations.

a 2H NMR relaxometry measurements of multilamellar dispersions of POPC-cholesterol membranes show linear dependence of the relaxation rates, \({R}_{1{{{\rm{Z}}}}}^{(i)}\), on the squared-order parameter, \({|{S}_{{{{\rm{CD}}}}}^{(i)}|}^{2}\), within the bilayer core. The gradual decrease in the linear slope with increasing cholesterol content indicates greater membrane bending rigidity. b Comparison of DMPC, POPC, and DOPC membranes with 0 and 50 mol% cholesterol shows that the decrease in the square law slopes is largest for saturated DMPC membranes, followed by monounsaturated POPC membranes and di-monounsaturated DOPC membranes. This implies that the cholesterol stiffening effect in lipid membranes is diminished by lipid chain unsaturation, in agreement with our NSE observations. Note that measurements of DMPC and POPC membranes were conducted using DMPC-d54 and POPC-d31, respectively, whereas data for DOPC membranes were obtained using 10 mol% of POPC-d31 as probe lipid. Data shown in blue correspond to 0 mol% cholesterol and data shown in brown correspond to 50 mol% cholesterol. c The reduced bending rigidity moduli, \({{\kappa }}/{{{\kappa }}}_{{{0}}}\), calculated from the slopes of the \({R}_{1{{{\rm{Z}}}}}^{(i)}\) vs. \({|{S}_{{{{\rm{CD}}}}}^{(i)}|}^{2}\) plots, exhibit a well-defined dependence on the area per lipid, \({{{A}}}_{{{\rm{L}}}}\), measured by SAXS/SANS. Specifically, \({{\kappa }}/{{{\kappa }}}_{{{0}}}\) show a power-law dependence ~ \({{{ A}}}_{{{\rm{L}}}}^{-{{7}}}\), in good agreement with findings by NSE and MD-Splay simulations. d The MD simulations of segmental chain dynamics, as probed by 2H NMR, yield an almost identical dependence of \({{\kappa }}/{{{\kappa }}}_{{{0}}}\) on \({{{A}}}_{{{\rm{L}}}}\) with a power of ~ –7, further confirming the scaling relations. Data are reported at 25 °C except for DMPC at 44 °C. Error bars represent ± SD from the mean value or as described in the SI for simulation results. Source data are provided as a Source Data file.

Analysis of the relaxation rates as a function of the squared order parameter was performed following the formalism developed earlier by Brown51. This was done by setting the slope to \(3{k}_{{{\rm{B}}}}T{\sqrt{\eta}} /5{S}_{{{\rm{s}}}}^{2}\sqrt{2({\kappa} /2{D}_{{{\rm{B}}}})^{3}}\), where \(\eta\) is the 3D viscosity coefficient and \({S}_{{{{\rm{s}}}}}\) is the order parameter for slow motions. Using this approach, our analysis revealed that DMPC, POPC, and DOPC membranes experienced a steady increase in \(\kappa\) with greater cholesterol content, clearly illustrating its stiffening effect in both saturated and unsaturated lipid membranes (see Supplementary Table 4). Here, we uniquely mapped the NMR-obtained bending moduli against corresponding area per lipid values measured by SAXS/SANS to demonstrate the interdependence of membrane elasticity, segmental dynamics, and lipid packing density. The unique combination of NMR-measured elastic moduli and scattering-derived lipid packing density revealed structure-property relations that are consistent with those in Fig. 2d. Indeed, \(\kappa /{\kappa }_{0}\) measured by 2H NMR showed a remarkably similar dependence on \({A}_{{{{\rm{L}}}}}\) to that obtained by NSE with a power-law ~ \({A}_{{{{\rm{L}}}}}^{-7}\) (Fig. 3c), regardless of the differences in \(\kappa\) values measured by the two techniques (Supplementary Tables 3, 4). We note that despite the different sample conditions dictated by the specific technical requirements of NSE and 2H NMR (i.e., unilamellar liposomal suspensions vs. multilamellar dispersions), the two methods provide complementary insights into mesoscopic membrane elasticity. For instance, while unilamellarity is ideally suited for bending fluctuation studies by NSE, the use of unilamellar liposomes with 2H NMR typically results in loss of spectral resolution due to rotational and diffusional motions. Nonetheless, once the differences in geometry are accounted for, spin-lattice relaxation rates exhibit corresponding trends in both types of systems, as demonstrated in previous publications52,53. This agreement primarily stems from the fact that 2H NMR signals are obtained from segmental relaxations within the membrane core, and are thus less sensitive to the sample lamellarity. Accordingly, our measurements yielded consistent scaling behavior of \(\kappa /{\kappa }_{0}\) across both NSE and 2H NMR studies (Fig. 2d and Fig. 3c).

To further validate the experimentally observed scaling laws, we applied our recently developed simulation approach for computationally modeling C–H bond relaxations measured by NMR spectroscopy49, referred to as MD-NMR simulations. Simulated spectral densities of thermally excited C–H bonds were generated for lipid membranes with cholesterol content between 0 and 50 mol%. By considering the motions of the C–H bonds along the lipid acyl chains relative to the membrane director, our simulations confirmed the relaxation rates follow an approximately linear relation in terms of the squared order parameter within the membrane core, as determined in NMR relaxometry studies. Analysis of the relaxation rates as explained above yielded the bending moduli reported in Supplementary Table 5. Consistent with the experiments, all simulated membranes showed higher \(\kappa\) values with increasing cholesterol molar ratio. In addition, the simulated \(\kappa /{\kappa }_{0}\) values exhibited a similar dependence on \({A}_{{{{\rm{L}}}}}\) as observed experimentally, with a power law given by \(\kappa /{\kappa }_{0}\propto {A}_{{{{\rm{L}}}}}^{-6.48\pm0.61}\) (Fig. 3d).

Unified scaling applies to chain unsaturation and sterol content

Next, to examine the packing dependence of the reduced bending moduli, we plotted \(\kappa /{\kappa }_{0}\) vs. \({A}_{{{{\rm{L}}}}}\) from all experiments and simulations. In accord with our hypothesis, the collected data showed a striking convergence into a unified scaling law (Fig. 4a), in excellent agreement with mean-field theory predictions34. A similar scaling law was obtained for the reduced bending moduli as a function of the reduced area per lipid, \({A}_{{{{\rm{L}}}}}/{A}_{0}\), as shown in Fig. 4b. In this case, the data were specifically fitted using the power law: \(\kappa /{\kappa }_{0}={c}_{1}{\left({A}_{{{{\rm{L}}}}}/{A}_{0}\right)}^{-\alpha }+{c}_{2}\), with \({c}_{1}+{c}_{2}=1\) to account for the limiting condition that \(\kappa /{\kappa }_{0}=1\) for \({A}_{{{{\rm{L}}}}}/{A}_{0}=1\), corresponding to cholesterol-free membranes. The convergence of all experimental and computational data to a well-defined dependence on \({A}_{{{{\rm{L}}}}}\) and \({A}_{{{{\rm{L}}}}}/{A}_{0}\) represents a powerful framework for assessing and predicting membrane elasticity from easily accessible information on membrane packing. For instance, lipid packing density can be readily obtained by structural studies or environment-sensitive probes54 compared to spectroscopic techniques needed for measuring mesoscopic bending moduli (e.g., requiring access to neutron facilities or solid-state 2H NMR instruments). Accordingly, the scaling relations demonstrated in this study open predictive capabilities for investigating complex lipid membranes beyond the experimental constraints outlined above. For example, one can predict the elastic responses of local membrane patches by mapping their measured lipid packing density to the obtained expression of \(\kappa /{\kappa }_{0}\) as a function of \({A}_{{{{\rm{L}}}}}\) or \({A}_{{{{\rm{L}}}}}/{A}_{0}\). An example of this is demonstrated in Supplementary Fig. 12 for environment-sensitive fluorescent probes. This mapping scheme holds practical significance by establishing the physical design rules for engineered membranes and artificial cells with real-world functionalities, as discussed later. However, further research is needed to translate these findings to other membrane types with distinct chain architectures and headgroup structures, e.g., cardiolipin and phosphatidylethanolamine (PE) lipids which are found in bacterial and mitochondrial membranes and are often used in constructing synthetic mimics.

a Collective data obtained by NSE (Fig. 2d), 2H NMR (Fig. 3c), and corresponding MD simulations (Figs. 2e and 3d) show a unified dependence of \({{\kappa }}/{{{\kappa }}}_{{{0}}}\) on \({{{A}}}_{{{\rm{L}}}}\). b The reduced bending moduli, \({{\kappa }}/{{{\kappa }}}_{{{0}}}\), show a similar scaling relation with the reduced area per lipid, \({{{A}}}_{{{\rm{L}}}}/{{{A}}}_{{{0}}}\). Notably, bending moduli of POPC membranes (denoted by †) from earlier studies by Henriksen et al.59 with different sterol types show excellent agreement with the scaling laws obtained in this study, when plotted against area per lipid values obtained from our SAXS measurements. This convergence of results indicates unified structure property relations in PC lipid membranes regardless of lipid chain unsaturation, sterol type, or sterol content. All data are at 25 °C except for DMPC at 30 °C and 44 °C. Error bars represent ± SD from the mean value or as described in the SI for simulation results. Source data are provided as a Source Data file.

Discussion

Cells maintain a delicate homeostatic balance between cholesterol and lipid chain unsaturation to adapt their membranes to environmental cues and dietary uptake. Recent evidence points to membrane packing as a regulatory mechanism for compositional remodeling, allowing cells to maintain local lipid densities needed for protein activity and overall function7,16. Yet, the complexity of membranes involves hundreds of lipid species55,56,57, leading to the question of whether the lipid diversity is associated with specific molecular interactions or nonspecific material properties of the lipid membrane. The ability to simplify compositional complexity into physical observables, such as the average area per lipid and elastic deformations, holds significant promise in distinguishing such interactions in membrane biophysics and related applications. Here, we demonstrate that—on the mesoscale—the elasticity of phosphatidylcholine (PC) lipid membranes follows a unified dependence on their packing across variations in cholesterol and lipid chain unsaturation. Our measurements leveraged spin-relaxation techniques that exclusively probed mesoscopic dynamics in the form of local bending fluctuations (NSE) and segmental chain relaxations (solid-state 2H NMR) with insights from corresponding MD simulation analyses. This integrative approach combining experimental and computational methods demonstrates convergence of mesoscopic studies of bending moduli accessed over complementary time scales (from ps to ~100 ns). The remarkable agreement across our methods reveals that collective lipid dynamics in the form of bending (splay) fluctuations or segmental relaxations are indeed manifestations of elastic membrane deformations dictated by lipid packing densities.

More importantly, our experimental and computational data have revealed that the normalized bending rigidity moduli, \(\kappa /{\kappa }_{0}\), of PC lipid membranes scale universally with the area per lipid as \({A}_{{{{\rm{L}}}}}^{-6.88\pm 0.34}\) (Fig. 4a), a finding of both theoretical and practical significance. A similar relation was observed in terms of \({A}_{{{{\rm{L}}}}}/{A}_{0}\) (Fig. 4b) yielding a scaling law that aligns remarkably well with theoretical predictions by Szleifer et al. based on conformational chain statistics34. The mechanism underlying the theory assumes that the hydrophobic core of the membrane is uniformly packed with chain segments. The elastic constants are thus determined via the chain probability distribution function by minimizing configurational free energy while accounting for packing constraints imposed on any given chain by its neighbors. It follows that the theory relates the bending modulus to lateral pressure profiles caused by chain packing, leading to a direct scaling of the bending modulus with the area per lipid such that \(\kappa \propto {A}_{{{{\rm{L}}}}}^{-\alpha }\) where \(\alpha \sim\!7-8\). The agreement of our findings with this theoretical prediction implies that the bending elasticity of membranes on mesoscopic scales is primarily determined by the conformational space available to the lipid chains—a property that is directly governed by lipid packing density.

Within the context of the molecular theory, one should note that flip-flop and long-range diffusional dynamics are excluded since they are slower than local membrane fluctuations32. As a case in point, a recent MD study showed that DOPC-cholesterol membranes undergo noticeable stiffening when cholesterol flip-flop and lateral diffusion are restricted, but this effect is reversed (i.e. the membrane appeared softer) when both processes were allowed58. While those observations were interpreted as nonuniversal effects of cholesterol, we note that by solely focusing on macroscopic elasticity measured over longer time scales (micro- and millisecond regime) one overlooks the hierarchy of membrane dynamics and their physical manifestations. In contrast, our data support the notion that the elastic effects induced by cholesterol are indeed universal on mesoscopic scales. Our observations also recapitulate findings from earlier computational studies by Lessen et al. reporting variations in membrane softening depending on whether one considers only conformational (local) relaxations or takes into account diffusional (long-range) dynamics27. Here, we propose that one can separate the two dynamic modes contributing to the apparent membrane elasticity by selectively probing conformational chain relaxations on mesoscopic scales (e.g., via NSE, NMR, or MD simulations). Measurements on longer scales can have additional effects from lateral diffusion, potentially giving rise to inconsistent trends of emergent elasticity. Such considerations are crucial to understanding the role of cholesterol and lipid chain unsaturation in biological functions occurring on different scales, such as protein conformational transitions (mesoscopic) compared to membrane deformations during cellular division (macroscopic).

In terms of broad significance, our results provide a robust and predictive tool for mapping lipid packing density to mesoscopic bending moduli across various membrane compositions. For example, we found that data from previous studies on POPC membranes with different sterols (i.e., cholesterol, lanosterol, and ergosterol)59 yielded normalized bending moduli (measured by vesicle fluctuation analysis) which closely follow the scaling laws determined from our current study (see Fig. 4a, b and Supplementary Table 6). Knowing that cholesterol and ergosterol have evolved from lanosterol, as demonstrated in recent discoveries of fossil biomarkers in rocks dating back 3.7 billion years60, the common effects of these sterols on the bending moduli suggest an important role of membrane elasticity throughout cellular evolution. In addition, a similar dependence of \(\kappa\) on \({A}_{{{{\rm{L}}}}}\) has also been observed in model membranes composed of binary mixtures of saturated PC lipids with different chain lengths (namely DMPC and DSPC) across a wide range of mixing ratios61. Put together, these observations suggest that the scaling laws we report hold for membrane compositions beyond PC lipid-sterol mixtures and regardless of lipid chain length.

Our development moreover has far-reaching implications in biophysics, cellular and synthetic biology, and rational designs of lipidic materials that motivate various applications. For example, the diversity of lipids in cell membranes leads to varied packing arrangements that support selective recruitment of proteins and bioactive molecules62,63. Elastic properties of such heterogenous environments can directly affect the folding and activity of membrane proteins18. The ability to correlate local packing densities to the rigidity of a given membrane patch allows mapping the energy landscapes of protein conformational transitions to those of the host lipid environment64,65,66, providing unique possibilities for optimizing protein function and developing membrane-targeted therapeutics. Such opportunities are synergistic with advances in cellular lipidomics which currently allow for detailed identification of lipid metabolites and compositional variations, providing high-resolution maps of lipid distributions within cellular membranes67,68. Combined with growing use of packing-sensitive probes69,70, it becomes possible to determine the physical principles correlating local lipid order and membrane elasticity to protein functions. Establishing these principles will accelerate our understanding of the mechanisms for lipid variations and lateral rearrangements in adaptive cellular responses71,72,73.

At a practical level, the scaling laws we identified can facilitate the design of artificial cells with tunable biophysical properties and controlled function. Regardless of whether such activities are triggered by external stimuli or by activating natural or engineered proteins74,75,76, implementing specific elastic membrane responses will expand the toolkit available for optimizing protein activity and artificial cell sensing77. Similarly, bottom-up developments of artificial cells with reconfigurable cytoskeletons require decoupling between innate membrane properties (e.g., elasticity) and cytoskeletal effects in achieving regulated membrane dynamics78,79. The distinction between membrane and cytoskeletal mechanics is also critical in cancerous cells, typically characterized by elevated cholesterol levels and increased cell stiffness80,81. In addition, our findings address a pressing need for enhanced liposomal designs for the delivery of vaccines and other targeted therapeutics82,83. The structure-property relations reported here provide a blueprint for optimizing the stability of lipid carriers using compositional and structural guides dictated by molecular packing density. Finally, our experimental data contribute to a library of structural and elastic membrane properties on spatiotemporal scales that are synergistic to ongoing molecular simulations. Such data libraries facilitate the training of machine-learning algorithms for predictive modeling of lipid membranes with increasing molecular complexity and tunable functionality.

Methods

Sample preparation

Phospholipids and cholesterol (ovine wool, >98%) were purchased from Avanti Polar Lipids (Albaster, AL) as dry powders and used without further purification. D2O (99.9%) was purchased from Cambridge Isotope Laboratories, Inc. and ultrapure H2O was obtained from a High-Q purification system. Lipid membranes were prepared in the form of unilamellar liposomes for SAXS/SANS and NSE experiments. All samples were prepared by first dissolving the required amount of lipids and cholesterol in chloroform together with 4 mol% of a corresponding charged lipid, e.g., DOPS (1,2-dioleoyl-sn-glycero-3-phospho-L-serine) for DOPC membranes and POPS (1-palmitoyl-2-oleoyl-sn-glycero-3-phospho-L-serine) for POPC membranes. Chloroform was then completely evaporated by purging with nitrogen, followed by overnight vacuum drying. The samples were hydrated with 10 mM sodium phosphate buffer (pH 8), followed by five freeze/thaw cycles to ensure sample homogeneity. Finally, unilamellar liposomal suspensions were prepared by standard extrusion through a 100-nm polycarbonate filter using a home-built automated extruder incorporating an Avanti mini extruder setup. Preparation of multilamellar dispersions for NMR experiments was done by first dissolving lipids in 1:1 methanol:cyclohexane solutions, then completely evaporating the solvent (overnight freeze drying), followed by 50 wt.% hydration with 10 mM sodium phosphate buffer (pH 8) prepared with 2H-depleted H2O (Cambridge Isotope Laboratories), and then subjected to multiple freeze/thaw cycles. Measurements of DMPC and POPC membranes were performed using DMPC-d54 and POPC-d31, respectively. For DOPC membranes, the experiments utilized 10 mol% of POPC-d31 as a probe lipid to circumvent challenges with lipid chain deuteration and unresolvable peaks in the spectrum from unsaturated chains. Our previous control studies have shown that the probe lipid approach accurately detects the average bilayer properties24. More details on sample preparation for the different experiments are provided in the SI.

Small-angle X-ray/neutron scattering (SAXS/SANS) measurements

SAXS measurements were carried out using the Rigaku BioSAXS-2000 system (Rigaku Americas) at Oak Ridge National Lab (ORNL) and the Xenocs Xeuss 3.0 SAXS instrument in the Material Characterization Laboratory at Virginia Tech. The SAXS data were collected at a fixed sample-to-detector distance calibrated using a silver behenate standard, with a typical overall data collection time of 3 h. One-dimensional (1D) scattering intensity profiles were obtained from 2D detector images by radially averaging the corrected 2D intensity, after background subtraction using compatible instrument software. All experiments were conducted using 20 mg/mL liposomal suspensions at 25 °C, except for DMPC suspensions which were run at 30 °C and 44 °C. The SANS experiments were performed at the NGB-30m SANS instrument at the National Institute of Standards and Technology (NIST) Center for Neutron Research (NCNR) and the CG-3 Bio-SANS instrument at the High-Flux Isotope Reactor (HFIR) at ORNL. Like SAXS, the SANS data were collected on 20 mg/mL liposomal suspensions and the 1D SANS signals were obtained from radial averaging of the 2D scattering signals after correcting for resolution, empty cell scattering, and background. The 1D SAXS/SANS data were analyzed following the scattering model described in the SI. Information about the code used for SAXS/SANS data fitting can be found under Code Availability.

Neutron spin-echo (NSE) spectroscopy measurements

NSE experiments were conducted on the NSE spectrometers at the NIST Center for Neutron Research (NCNR) and Spallation Neutron Source (SNS) at ORNL. Measurements were conducted using 50 mg/mL liposomal suspensions of lipid-cholesterol membranes at 25 °C for DOPC, SDPC, PLPC, and POPC and at 30 °C and 44 °C for DMPC. All measurements were performed on fully protiated membranes, i.e., using fully protiated lipids and cholesterol, in D2O buffer to maximize the contrast between the membranes and their aqueous environment for the highest signal-to-noise ratio. Experiments at NCNR were performed over a \(Q\)-range of ~ 0.03–0.1 Å−1 whereas experiments at SNS were performed over a \(Q\)-range of ~ 0.04–0.15 Å−1. In both cases, the instrument resolution and the buffer were measured under the same configurations for data reduction and normalization. Briefly, bending fluctuation spectra of liposomal membranes were measured in terms of the normalized dynamic structure factor \({{{\rm{S}}}}(Q,t)/{{{\rm{S}}}}(Q,0)\) vs. the Fourier time, t. When fitted to a refined Zilman-Granek model, this yielded the relaxation rates \(\Gamma (Q)\) of bending fluctuations35. The bending moduli were then obtained from the slopes of the linear fits of \(\Gamma (Q)\) vs. \({Q}^{3}\) for each of the measured samples. More details of the measurements and data fitting procedures are provided in the SI. Information about the code used in fitting the fluctuation spectra can be found under Code Availability.

Solid-state 2H NMR spectroscopy measurements

Experiments with solid-state 2H NMR spectroscopy were conducted using a highly modified Bruker AMX-500 spectrometer (11.78 T magnetic field strength, 2H frequency 76.77 MHz) at the University of Arizona. Measurements were conducted at 25 °C except for DMPC samples which were measured at 44 °C to ensure the lipid membranes were in the fluid state. Powder-type spectra (Pake patterns) were recorded on multilamellar lipid dispersions with a phase-cycled, quadrupole echo sequence (π/2)x – d6 − (π/2)y – d7 – acquire. These patterns were obtained by Fourier transformation of quadrupolar echoes, starting at the echo top with a fast Fourier transform algorithm, using an in-house MATLAB routine. Pulse sequences were generated using a home-built solid-state probe with an 8-mm diameter horizontal solenoid coil and high-voltage capacitors (Polyflon; Norwal, CT) with a Bruker (Billerica, MA) radiofrequency amplifier. Equilibrium spectra corresponding to the parallel orientation of the bilayer normal to the external magnetic field were obtained by numerical inversion of nonoriented powder-type spectra using the de-Pakeing method. An inversion-recovery pulse sequence, described in the SI, was used to measure spin-lattice relaxation times. The spin-lattice relaxation rates for each resolved peak were obtained by nonlinear regression fitting. Further details can be found in the SI. Information about the codes used is provided under Code Availability.

All-atom molecular dynamics simulations

All-atom MD simulations were conducted according to the protocols described in the SI. The simulation trajectories were analyzed in two different ways which complement the experimental methods used in this work. Analyses of splay fluctuations provided direct comparison against NSE data, and analyses of segmental relaxations relative to the membrane normal enabled comparisons with solid-state 2H NMR observations. Details of the simulation setup and data analysis can be found in the SI. Information about the codes used in both analysis approaches can be found under Code Availability.

Reporting summary

Further information on research design is available in the Nature Portfolio Reporting Summary linked to this article.

Data availability

Unless otherwise stated, all data supporting the results of this study can be found in the article, supplementary, and source data files. Experimental data and simulation trajectories can be accessed through Virginia Tech’s Data Repository [https://doi.org/10.7294/27118998]. Source data are provided with this paper.

Code availability

The code used to analyze the SAXS/SANS data can be accessed as a SasView plug-in model through Virginia Tech’s Data Repository [https://doi.org/10.7294/27118998]. The code used to analyze the NSE signals can be accessed as an Origin file in the same repository. The codes used for analyzing the NMR data can be accessed as MATLAB files in the data repository. The code for calculating bending moduli from splay fluctuations was published by Johner et al.84 and can be found at Github [https://github.com/njohner/ost_pymodules]. The code for calculating bending moduli following NMR-based analysis of segmental relaxations is described in Doktorova et al.49 and can be found at Zenodo [https://zenodo.org/records/15742918].

References

Gözen, I. et al. Protocells: milestones and recent advances. Small 18, 2106624 (2022).

Griffiths, G. Cell evolution and the problem of membrane topology. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 8, 1018–1024 (2007).

Deamer, D., Dworkin, J. P., Sandford, S. A., Bernstein, M. P. & Allamandola, L. J. The first cell membranes. Astrobiology 2, 371–381 (2002).

Ernst, R., Ejsing, C. S. & Antonny, B. Homeoviscous adaptation and the regulation of membrane lipids. J. Mol. Biol. 428, 4776–4791 (2016).

Budin, I. et al. Viscous control of cellular respiration by membrane lipid composition. Science 362, 1186–1189 (2018).

Sinensky, M. Homeoviscous adaptation—a homeostatic process that regulates the viscosity of membrane lipids in Escherichia coli. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 71, 522–525 (1974).

Ballweg, S. et al. Regulation of lipid saturation without sensing membrane fluidity. Nat. Commun. 11, 756 (2020).

Levental, K. R. et al. Lipidomic and biophysical homeostasis of mammalian membranes counteracts dietary lipid perturbations to maintain cellular fitness. Nat. Commun. 11, 1339 (2020).

Leveille, C. L., Cornell, C. E., Merz, A. J. & Keller, S. L. Yeast cells actively tune their membranes to phase separate at temperatures that scale with growth temperatures. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 119, e2116007119 (2022).

Burns, M., Wisser, K., Wu, J., Levental, I. & Veatch, S. L. Miscibility transition temperature scales with growth temperature in a zebrafish cell line. Biophys. J. 113, 1212–1222 (2017).

Irving, L. Arctic life of birds and mammals: Including man. 2, (Springer Science & Business Media, 2012).

Winnikoff, J. R. et al. Homeocurvature adaptation of phospholipids to pressure in deep-sea invertebrates. Science 384, 1482–1488 (2024).

Osetrova, M. et al. Lipidome atlas of the adult human brain. Nat. Commun. 15, 4455 (2024).

Takamori, S. et al. Molecular anatomy of a trafficking organelle. Cell 127, 831–846 (2006).

Andersen, O. S. & Koeppe, R. E. Bilayer thickness and membrane protein function: an energetic perspective. Annu. Rev. Biophys. Biomol. Struct. 36, 107–130 (2007).

Levental, I. & Lyman, E. Regulation of membrane protein structure and function by their lipid nano-environment. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 24, 107–122 (2023).

Brown, M. F. Soft matter in lipid–protein interactions. Annu. Rev. Biophys. 46, 379–410 (2017).

Jacobs, M. L., Boyd, M. A. & Kamat, N. P. Diblock copolymers enhance folding of a mechanosensitive membrane protein during cell-free expression. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 116, 4031–4036 (2019).

Lundbæk, J. A., Birn, P., Girshman, J., Hansen, A. J. & Andersen, O. S. Membrane stiffness and channel function. Biochemistry 35, 3825–3830 (1996).

Brown, M. F. Modulation of rhodopsin function by properties of the membrane bilayer. Chem. Phys. Lipids 73, 159–180 (1994).

Kozlov, M. M. & Taraska, J. W. Generation of nanoscopic membrane curvature for membrane trafficking. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 24, 63–78 (2023).

Tripathy, M. & Srivastava, A. Lipid packing in biological membranes governs protein localization and membrane permeability. Biophys. J. 13, 2727–2743 (2023).

Stachowiak, J. C. et al. Membrane bending by protein–protein crowding. Nat. Cell Biol. 14, 944–949 (2012).

Chakraborty, S. et al. How cholesterol stiffens unsaturated lipid membranes. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 117, 21896–21905 (2020).

Pan, J., Tristram-Nagle, S. & Nagle, J. F. Effect of cholesterol on structural and mechanical properties of membranes depends on lipid chain saturation. Phys. Rev. E 80, 021931 (2009).

Gracià, R. S., Bezlyepkina, N., Knorr, R. L., Lipowsky, R. & Dimova, R. Effect of cholesterol on the rigidity of saturated and unsaturated membranes: fluctuation and electrodeformation analysis of giant vesicles. Soft Matter 6, 1472–1482 (2010).

Lessen, H. J., Sapp, K. C., Beaven, A. H., Ashkar, R. & Sodt, A. J. Molecular mechanisms of spontaneous curvature and softening in complex lipid bilayer mixtures. Biophys. J. 121, 3188–3199 (2022).

Henzler-Wildman, K. & Kern, D. Dynamic personalities of proteins. Nature 450, 964–972 (2007).

Molugu, T. R., Lee, S. & Brown, M. F. Concepts and methods of solid-state NMR spectroscopy applied to biomembranes. Chem. Rev. 117, 12087–12132 (2017).

Hung, W.-C., Lee, M.-T., Chen, F.-Y. & Huang, H. W. The condensing effect of cholesterol in lipid bilayers. Biophys. J. 92, 3960–3967 (2007).

Kučerka, N., Nieh, M.-P. & Katsaras, J. Fluid phase lipid areas and bilayer thicknesses of commonly used phosphatidylcholines as a function of temperature. Biochim. Biophys Acta 1808, 2761–2771 (2011).

Harries, D. & Ben-Shaul, A. Conformational chain statistics in a model lipid bilayer: comparison between mean field and Monte Carlo calculations. J. Chem. Phys. 106, 1609–1619 (1997).

Arriaga, L. R. et al. Stiffening effect of cholesterol on disordered lipid phases: a combined neutron spin echo + dynamic light scattering analysis of the bending elasticity of large unilamellar vesicles. Biophys. J. 96, 3629–3637 (2009).

Szleifer, I., Kramer, D., Ben-Shaul, A., Gelbart, W. M. & Safran, S. A. Molecular theory of curvature elasticity in surfactant films. J. Chem. Phys. 92, 6800–6817 (1990).

Nagao, M., Kelley, E. G., Ashkar, R., Bradbury, R. & Butler, P. D. Probing elastic and viscous properties of phospholipid bilayers using neutron spin echo spectroscopy. J. Phys. Chem. Lett. 8, 4679–4684 (2017).

Zilman, A. G. & Granek, R. Undulations and dynamic structure factor of membranes. Phys. Rev. Lett. 77, 4788–4791 (1996).

Doktorova, M., LeVine, M. V., Khelashvili, G. & Weinstein, H. A new computational method for membrane compressibility: bilayer mechanical thickness revisited. Biophys. J. 116, 487–502 (2019).

Doktorova, M., Harries, D. & Khelashvili, G. Determination of bending rigidity and tilt modulus of lipid membranes from real-space fluctuation analysis of molecular dynamics simulations. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 19, 16806–16818 (2017).

Eid, J., Razmazma, H., Jraij, A., Ebrahimi, A. & Monticelli, L. On calculating the bending modulus of lipid bilayer membranes from buckling simulations. J. Phys. Chem. B 124, 6299–6311 (2020).

Kelley, E. G., Frewein, M. P. K., Czakkel, O. & Nagao, M. Nanoscale bending dynamics in mixed-chain lipid membranes. Symmetry 15, 191 (2023).

Szleifer, I., Kramer, D., Ben-Shaul, A., Roux, D. & Gelbart, W. M. Curvature elasticity of pure and mixed surfactant films. Phys. Rev. Lett. 60, 1966–1969 (1988).

Kozlov, M. M. & Helfrich, W. Effects of a cosurfactant on the stretching and bending elasticities of a surfactant monolayer. Langmuir 8, 2792–2797 (1992).

Farago, B., Richter, D., Huang, J. S., Safran, S. A. & Milner, S. T. Shape and size fluctuations of microemulsion droplets: the role of cosurfactant. Phys. Rev. Lett. 65, 3348–3351 (1990).

Safinya, C. R., Sirota, E. B., Roux, D. & Smith, G. S. Universality in interacting membranes: the effect of cosurfactants on the interfacial rigidity. Phys. Rev. Lett. 62, 1134–1137 (1989).

Steinkühler, J., Sezgin, E., Urbančič, I., Eggeling, C. & Dimova, R. Mechanical properties of plasma membrane vesicles correlate with lipid order, viscosity and cell density. Commun. Biol. 2, 337 (2019).

Rawicz, W., Olbrich, K. C., McIntosh, T., Needham, D. & Evans, E. Effect of chain length and unsaturation on elasticity of lipid bilayers. Biophys. J. 79, 328–339 (2000).

Bermúdez, H., Hammer, D. A. & Discher, D. E. Effect of bilayer thickness on membrane bending rigidity. Langmuir 20, 540–543 (2004).

Brown, M. F., Thurmond, R. L., Dodd, S. W., Otten, D. & Beyer, K. Composite membrane deformation on the mesoscopic length scale. Phys. Rev. E 64, 010901 (2001).

Doktorova, M., Khelashvili, G., Ashkar, R. & Brown, M. F. Molecular simulations and NMR reveal how lipid fluctuations affect membrane mechanics. Biophys. J. 122, 984–1002 (2023).

Martinez, G. V., Dykstra, E. M., Lope-Piedrafita, S., Job, C. & Brown, M. F. NMR elastometry of fluid membranes in the mesoscopic regime. Phys. Rev. E 66, 050902 (2002).

Brown, M. F. Theory of spin-lattice relaxation in lipid bilayers and biological membranes. 2H and 14N quadrupolar relaxation. J. Chem. Phys. 77, 1576–1599 (1982).

Brown, M. F., Ribeiro, A. A. & Williams, G. D. New view of lipid bilayer dynamics from 2H and 13C NMR relaxation time measurements. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 80, 4325–4329 (1983).

Nevzorov, A. A. & Brown, M. F. Dynamics of lipid bilayers from comparative analysis of 2H and 13C nuclear magnetic resonance relaxation data as a function of frequency and temperature. J. Chem. Phys. 107, 10288–10310 (1997).

Doktorova, M. et al. Cell membranes sustain phospholipid imbalance via cholesterol asymmetry. Cell. 188, 2586–2602.E24 (2025).

Harayama, T. & Riezman, H. Understanding the diversity of membrane lipid composition. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 19, 281 (2018).

Shevchenko, A. & Simons, K. Lipidomics: coming to grips with lipid diversity. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 11, 593–598 (2010).

van Meer, G., Voelker, D. R. & Feigenson, G. W. Membrane lipids: where they are and how they behave. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 9, 112–124 (2008).

Pöhnl, M., Trollmann, M. F. W. & Böckmann, R. A. Nonuniversal impact of cholesterol on membranes mobility, curvature sensing and elasticity. Nat. Commun. 14, 8038 (2023).

Henriksen, J. et al. Universal behavior of membranes with sterols. Biophys. J. 90, 1639–1649 (2006).

Brocks, J. J. et al. Lost world of complex life and the late rise of the eukaryotic crown. Nature 618, 767–773 (2023).

Kelley, E. G., Butler, P. D., Ashkar, R., Bradbury, R. & Nagao, M. Scaling relationships for the elastic moduli and viscosity of mixed lipid membranes. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 117, 23365–23373 (2020).

Lingwood, D. & Simons, K. Lipid rafts as a membrane-organizing principle. Science 327, 46–50 (2010).

Sezgin, E. et al. Adaptive lipid packing and bioactivity in membrane domains. PLOS ONE 10, e0123930 (2015).

Dill, K. A. & MacCallum, J. L. The protein-folding problem, 50 years on. Science 338, 1042–1046 (2012).

Onuchic, J. N., Luthey-Schulten, Z. & Wolynes, P. G. Theory of protein folding: the energy landscape perspective. Annu. Rev. Phys. Chem. 48, 545–600 (1997).

Smith, A. A., Vogel, A., Engberg, O., Hildebrand, P. W. & Huster, D. A method to construct the dynamic landscape of a bio-membrane with experiment and simulation. Nat. Commun. 13, 108 (2022).

Symons, J. L. et al. Lipidomic atlas of mammalian cell membranes reveals hierarchical variation induced by culture conditions, subcellular membranes, and cell lineages. Soft Matter 17, 288–297 (2021).

Bai, Y. et al. Single-cell mapping of lipid metabolites using an infrared probe in human-derived model systems. Nat. Commun. 15, 350 (2024).

Sanchez, S. A., Tricerri, M. A. & Gratton, E. Laurdan generalized polarization fluctuations measures membrane packing micro-heterogeneity in vivo. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 109, 7314–7319 (2012).

Sezgin, E., Sadowski, T. & Simons, K. Measuring lipid packing of model and cellular membranes with environment sensitive probes. Langmuir 30, 8160–8166 (2014).

Miller, E. J. et al. Divide and conquer: how phase separation contributes to lateral transport and organization of membrane proteins and lipids. Chem. Phys. Lipids 233, 104985 (2020).

Ernst, R., Ballweg, S. & Levental, I. Cellular mechanisms of physicochemical membrane homeostasis. Curr. Opin. Cell Biol. 53, 44–51 (2018).

Puth, K., Hofbauer, H. F., Sáenz, J. P. & Ernst, R. Homeostatic control of biological membranes by dedicated lipid and membrane packing sensors. Biol. Chem. 396, 1043–1058 (2015).

Gavriljuk, K. et al. A self-organized synthetic morphogenic liposome responds with shape changes to local light cues. Nat. Commun. 12, 1548 (2021).

Gispert, I. et al. Stimuli-responsive vesicles as distributed artificial organelles for bacterial activation. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 119, e2206563119 (2022).

Peruzzi, J. A., Galvez, N. R. & Kamat, N. P. Engineering transmembrane signal transduction in synthetic membranes using two-component systems. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 120, e2218610120 (2023).

Boyd, M. A. & Kamat, N. P. Designing artificial cells towards a new generation of biosensors. Trends Biotechnol. 39, 927–939 (2021).

Daly, M. L. et al. Designer peptide–DNA cytoskeletons regulate the function of synthetic cells. Nat. Chem. 16, 1229–1239 (2024).

Novosedlik, S. et al. Cytoskeleton-functionalized synthetic cells with life-like mechanical features and regulated membrane dynamicity. Nat. Chem. 17, 356–364 (2025).

Xu, W. et al. Cell stiffness is a biomarker of the metastatic potential of ovarian cancer cells. PLoS ONE 7, e46609 (2012).

Kuzu, O. F., Noory, M. A. & Robertson, G. P. The role of cholesterol in cancer. Cancer Res. 76, 2063–2070 (2016).

Patel, S. et al. Naturally-occurring cholesterol analogues in lipid nanoparticles induce polymorphic shape and enhance intracellular delivery of mRNA. Nat. Commun. 11, 983 (2020).

Zheng, L., Bandara, S. R., Tan, Z. & Leal, C. Lipid nanoparticle topology regulates endosomal escape and delivery of RNA to the cytoplasm. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 120, e2301067120 (2023).

Johner, N., Harries, D. & Khelashvili, G. Implementation of a methodology for determining elastic properties of lipid assemblies from molecular dynamics simulations. BMC Bioinformatics 17, 161 (2016).

Acknowledgments

We thank Dr. Michihiro Nagao and Dr. Elizabeth Kelley for assistance with the NSE and SANS data acquisition at NIST. R.A. acknowledges support from the Jeffress Trust Award Program in Interdisciplinary Research and NSF Grants MCB-2137154 and DMR-2350336. M.F.B. acknowledges support by NIH Grant R01EY026041 and NSF Grants MCB-1817862, CHE-1904125, and DMR-2350337. M.D. was supported by a Ruth L. Kirschstein NIH Postdoctoral Fellowship, NIH Grant 1F32GM134704, and the SciLifeLab & Wallenberg Data Driven Life Science Program (grant KAW 2024.0159). G.K. gratefully acknowledges support from the 1923 Fund, and access to computational resources awarded through the COVID-19 High Performance Computing Consortium at the Center for Computational Innovations at the Rensselaer Polytechnic Institute. T.K. acknowledges partial support from the ORNL Neutron Scattering Graduate Research Program. The authors acknowledge the use of neutron-scattering facilities at NIST and ORNL. Access to the NIST NSE beamline was provided by the Center for High Resolution Neutron Scattering, a partnership between NIST and NSF under Agreement DMR-1508249. The SANS measurements performed on the Bio-SANS instrument utilized the Center for Structural Molecular Biology (FWP ERKP291), a Structural Biology Resource of the U.S. DOE Office of Biological and Environment Research. SAXS and NSE studies conducted at ORNL were facilitated by the Scientific User Facilities Division of the Department of Energy (DOE) Office of Science, Basic Energy Science (BES) Program, under Contract DE-AC05-00OR22725. Purchase of the Xenocs Xeuss 3.0 SAXS/WAXS instrument at Virginia Tech (used to obtain results included in this publication) was supported by NSF Grant DMR-MRI-2018258. This work benefited from the use of the SasView application, originally developed under NSF award DMR-0520547. SasView contains code developed with funding from the European Union’s Horizon 2020 research and innovation program under the SINE2020 project under Agreement No. 654000.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

T.K. and S.G. collected and analyzed the NSE data; T.K., S.G., and N.B.M. collected and analyzed the SAXS/SANS data; N.B.M. developed the SAXS/SANS fitting codes; T.K. collated all results and led the scaling analysis across all methods; F.T.D. analyzed the NMR data; H.L.S. and J.K. assisted with the SAXS data collection at ORNL; L.-R.S. assisted with the NSE data collection and reduction; S.V.P. assisted with the SANS data collection; M.D. and G.K. designed and conducted the MD simulations; M.D. led the analysis of the simulation trajectories; M.F.B. directed the performance and analysis of the NMR studies; R.A. directed the performance of scattering studies and subsequent data analysis; M.D., M.F.B., and R.A. discussed and reviewed the results; R.A designed the overall research project, delineated the scope and objectives, conceptualized and oversaw the convergence of methods, and wrote the manuscript.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Peer review

Peer review information

Nature Communications thanks Veerendra Sharma and the other anonymous reviewer(s) for their contribution to the peer review of this work. A peer review file is available.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Source data

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Kumarage, T., Gupta, S., Morris, N.B. et al. Cholesterol modulates membrane elasticity via unified biophysical laws. Nat Commun 16, 7024 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-025-62106-0

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-025-62106-0