Abstract

Biological sodium channels efficiently discriminate between same–charge ions with similar hydration shells. However, achieving precise ion selectivity and high throughput in artificial ion channel fabrication remains challenging. Here, we investigate angstrom–scale channels in 15-crown-5 (15C5) functionalized COF membranes for fast, selective ion transport. Due to crown ether recognition of sodium ions, channels in DHTA-Hz-15C5 membranes selectively facilitate Na+ transport, further enhanced by the hydroxyl-enriched COF skeleton. A Na+/K+ selectivity of 58.31 is achieved with 9.33 mmol m−2 h–1 permeance, significantly exceeding current membranes and resembling biological channels. Theoretical simulations indicate one–dimensional COF channels facilitate transport, while crown ether recognition makes the Na+ energy barrier significantly lower than K⁺, enabling ultrahigh selectivity with high Na⁺ permeability. This promotes COFs for efficient single-ion transport and advances crown ether ion selectivity in nano-restricted environments.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Biological sodium ion channels, characterized by their high selectivity of Na+ over K+ and rapid Na+ conduction rate, play important roles in a wide range of biological processes across virtually all cell types1,2,3. Typically, these natural channels exhibit a Na+/K+ selectivity of 10 – 102 and ultrafast sodium ion transport rate, serving to maintain the hemostasis equilibrium and transduce neural signals4. In recent years, there has been significant interest in developing artificial biological channels, because of their promising applications in water treatment5, nanofluidic devices6,7,8, ion gating9,10 and beyond. Numerous artificial ion channels/membranes have been designed to replicate the selective transport properties of biological channels. However, the identical ion valence, the comparable subnanometer dimensions of both bare ions (1–3 Å) and hydrated ions (6.5–8 Å), as well as the sub–2 Å size difference among different monovalent ions, present significant challenges to separate monovalent cation mixtures11.

To date, only a few studies have reported artificial sodium ion channels with a Na+/K+ selectivity over 104,12. Furthermore, the transport rate of Na+ in the aforementioned artificial sodium channels remains significantly lower than that of their biological counterparts, primarily due to the absence of synergistic effects from angstrom-scale channels and specific binding sites12,13,14,15,16. This disparity highlights the need for further innovation to enhance both the selectivity and transport rate of artificial sodium channels to approach the remarkable capabilities of their natural counterparts.

To successfully develop synthetic channels that mimic the properties of natural biological channels, artificial Na+ channels have primarily been synthesized by integrating crown ethers with specific Na+ binding sites into various materials, such as soft lipids13,14, graphene15, and MOFs12,16. Among these, metal–organic frameworks (MOFs) have garnered extensive attention due to their well–suited cavities and abundant functional groups for ion separation17. Specifically, an artificial ion channel, synthesized by incorporating a crown ether into a MOF through post–modification, exhibited a Na+/K+ selectivity up to 102, approaching that of biological channels12. In the three-dimensional framework of MOFs, distorted ion transport channels impede the rate of ion diffusion. Additionally, water molecules can readily disrupt relatively labile metal-organic coordination bonds, resulting in crystallographic phase transitions or structural degradation of MOFs18,19. Consequently, simultaneously achieving superior single-ion selectivity and permeability remains a significant challenge.

Unlike MOFs, two–dimensional polycrystalline covalent organic frameworks have locally straight, one–dimensional channels, which are conductive to the transport of ions and can effectively improve ion permeability20,21,22. In recent years, COF membranes have demonstrated exceptional ion selectivity and have been extensively investigated for applications in ion separation23,24,25,26,27, energy storage28,29, catalysis30,31 and other fields. The long–range ordered structure of COF ensures a narrow distribution of channel size and high pore density, which can result in both high ion selectivity and permeability32. For example, a COF membrane33, using oligoether functionalization to enhance ion selectivity, achieved a separation factor over 103 for Li+/Mg2+ and the Li+ permeance more than 25 mmol m−2 h–1, far exceeding that of other two–dimensional materials. This success in separating monovalent ions from divalent ions highlights the potential of COF as a platform for constructing artificial channels capable of high Na+/K+ selectivity and Na+ transport rate. However, due to the relatively large pore size of COF, ranging from 1 to 5 nm34, achieving precise monovalent ion separation is challenging. Current research focuses on modifying pore wall active sites to enhance selectivity32,35,36, but results have been limited, with monovalent ion selectivity reaching only 4.232. To date, COF–based artificial sodium–selective ionic devices with a simultaneous high selectivity and permeability remain elusive.

Herein, we report the synthesis of an artificial sodium-selective membrane by confining 15-crown-5 ether (15C5) within a DHTA-Hz membrane featuring straight one-dimensional channels with a diameter of 8.4 Å, which contain hydroxyl groups that facilitate Na+ transport. Experiments and molecular simulations revealed that the functional COF incorporating 15C5 molecules specifically recognizes and binds Na+ ions, leading to an accelerated permeation rate of Na+ ions. The synthesized DHTA-Hz-15C5 membrane exhibited a high Na+/K+ selectivity of 58.31 and an ultrahigh permeation of 9.33 mmol m−2 h–1, surpassing previously reported artificial nanochannels. This study represents an instance of ultrahigh sodium ion selectivity in sub–nanoporous COF channels with specific ion binding sites. Our study offers an approach for developing multiple sub–nanochannels for ion separation and other emerging nanofluidic applications.

Results and discussion

Fabrication and characterization of DHTA-Hz-15C5 membranes

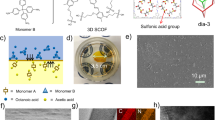

The DHTA-Hz membrane was synthesized by an in–situ growth of monomers on dual–channel anodic aluminum oxide (AAO) support. Subsequent post–modification with crown ether resulted in the formation of the DHTA-Hz-15C5 membranes (Fig. 1a). The AAO support, featuring a pore size of 80–100 nm and through–holes (Supplementary Fig. 1), facilitated the in–situ synthesis of defect–free DHTA-Hz membrane. The DHTA-Hz selective layer was formed on the AAO support within a custom–made reaction cell (Supplementary Fig. 2). The AAO membrane was positioned between two compartments, with one compartment containing 2,4–dihydroxybenzene–1,3,5–trialdehyde (DHTA) in an organic phase and the other compartment containing a hydrazine hydrate (Hz) and p–toluenesulfonic acid solution in an aqueous phase. The Hz reacts with DHTA in the organic phase at the surface of AAO support, forming the DHTA-Hz membrane as depicted in Fig. 1g (the COF structure is shown in Supplementary Fig. 3). Subsequently, the 15–crown–5 ether (15C5) was introduced into the nanopore channels via post–synthesis. The relatively smaller size of 15C5 ( ~ 6 Å) compared to that of the one–dimensional nanochannels (8.4 Å) in DHTA-Hz membrane, and the host–guest interaction between 15C5 and DHTA-Hz, ensure the stable incorporation of 15C5 in the COF membranes and the introduction of 15C5 does not alter the surface characteristics of the DHTA-Hz membranes. (Supplementary Fig. 4). Such selective binding enables Na+ ions to transport within locally confined channels, excluding K+, thereby achieving a high Na+/K+ separation ratio. Apart from the 15C5, the large number of-OH functional groups inside the DHTA-Hz pores also facilitate Na+ transport. This synergistic effect is crucial for its exceptional ion separation performance36.

a In–situ growth of DHTA-Hz selective layer on AAO support via interfacial polymerization. Crown ether 15C5 was introduced into the one–dimensional channel of the selective layer to form the DHTA-Hz-15C5 membrane. b SEM image of the surface of DHTA-Hz membrane. c SEM cross–sectional image of DHTA-Hz membrane. d Solid–state 13C CP/MAS NMR spectrum of DHTA-Hz membrane. e ACTEM image of DHTA-Hz membrane. f SEM image of the surface of DHTA-Hz-15C5 membrane. g Photograph of the DHTA-Hz membrane.

After in–situ confinement and growth, a highly crystalline and continuous DHTA-Hz membrane was successfully fabricated on AAO support. Scanning electron microscopy (SEM) images of the surface and cross-section of DHTA-Hz (Fig. 1b, c and Supplementary Fig. 5) reveal a layer thickness of approximately 580 nm, with no boundary defects or cracks. The defect-free nature of the membrane was further confirmed through gas sensitivity tests (Supplementary Fig. 6). Moreover, the solid–state 13C nuclear magnetic resonance (13C NMR) spectra provide chemical information on the atomic–level structure of DHTA-Hz (Fig. 1d). The Peak at 159.7 ppm is attributed to the carbon of the imine–type (C=N) group in DHTA-Hz. The spherical aberration corrected transmission electron microscope (ACTEM) image (Fig. 1e) displays a locally highly ordered arrangement with independent diffraction direction which indicates the high crystallinity of the DHTA-Hz membrane. Wide-angle X-ray scattering (WAXS) analysis further elucidates the crystallinity of the DHTA-Hz membrane (Supplementary Fig. 7). The PXRD pattern aligns with these findings, indicating consistent structural characteristics. The DHTA-Hz membrane exhibited intense diffraction peaks at 7.2° and 27°, which can be attributed to (100) and (001) facets diffraction, respectively (Fig. 2a, blue curve). As 15C5 gradually penetrates the pores of DHTA-Hz, the peak intensity at 7.2° corresponding to the (100) face of DHTA-Hz diminishes but remains well crystallized, indicating that 15C5 are not only present on the surface of the membrane but also occupy the pores of DHTA-Hz (Fig. 1f, and Supplementary Fig. 8).

a XRD patterns of AAO, DHTA-Hz and DHTA-Hz-15C5 membranes. b N2 adsorption/desorption isotherms of DHTA-Hz and DHTA-Hz-15C5 membranes. c Pore size distributions of DHTA-Hz and DHTA-Hz-15C5 membranes. d FTIR spectra of 15C5, DHTA-Hz and DHTA-Hz-15C5 membranes. e Thermogravimetric analysis of 15C5, DHTA-Hz and DHTA-Hz-15C5 membranes. f C 1s high–resolution XPS spectra of the DHTA-Hz and DHTA-Hz-15C5membranes. g Perfect confinement of 15C5 in the DHTA-Hz membrane and electrostatic potential (ESP) diagram of 15C5 and DHTA-Hz obtained from DFT calculation. The shaded area represents the binding sites of 15C5 and DHTA-Hz.

The Brunauer–Emmett–Teller (BET) surface area of DHTA-Hz-15C5 exhibited a significant reduction in comparison to that of DHTA-Hz (Fig. 2b). The pore size distribution demonstrates that the DHTA-Hz-15C5 have a distinct peak at 6 Å, which is smaller than that of DHTA-Hz (Fig. 2c), further confirming the presence of 15C5 in the DHTA-Hz channel37. Fourier transform infrared spectroscopy (FTIR) analysis of the DHTA-Hz membrane revealed the disappearance of –CHO in DHTA (Supplementary Fig. 9, red curve) and the emergence of a new vibrational band at 1570 cm–1, attributed to the C = N bond (supplementary Fig. 9, black curve), indicating the formation of imine bonds38,39. In contrast, the DHTA-Hz-15C5 membrane obtained by post–modification of the crown ether (15C5) showed C–O–C stretching around 1100 cm–1 (Fig. 2d, green curve), indicating successful synthesis of DHTA-Hz-15C5 membrane. Thermogravimetric analysis40 of 15C5, DHTA-Hz, and DHTA-Hz-15C5 membranes indicated a higher weight loss for the DHTA-Hz-15C5 membrane compared to the DHTA-Hz membrane, implying the presence of 15C5 within the pores of DHTA-Hz membrane (Fig. 2e). The molar percentage of 15C5 molecules with DHTA-Hz pores is ~23.83% (see the Supplementary Materials for the calculation details). Following the crown ether modification, the water contact angle of DHTA-Hz-15C5 decreased from approximately 69° to about 39° (Supplementary Fig. 10), suggesting an enhancement in the hydrophilicity of the DHTA-Hz-15C5 layer, which was beneficial to ion transport.

We further investigated the binding mechanism between 15C5 and the DHTA-Hz membrane via X-ray photoelectron spectroscopy (XPS) and FTIR analyses. The FTIR spectra (Fig. 2d) exhibited a notable blue shift of the C=N bond in the DHTA-Hz-15C5 membrane, shifting from 1570 cm–1 to 1639 cm–1 in comparison to DHTA-Hz. This shift indicates the presence of a significant electron–withdrawing group near the C=N bond, unveiling the host–guest interaction between 15C5 and DHTA-Hz. An analysis of the electrostatic potential of the crown ether 15C5 was conducted by DFT, as depicted in Fig. 2g. The analysis reveals that the O atoms of crown ether exhibit a notably high positive charge outside of the cavity, which facilitates a strong ionic interaction with the negatively charged nitrogen atoms situated within the one–dimensional channel of the DHTA-Hz. The zeta potential measurements further corroborate these findings, providing additional evidence to support this conclusion (Supplementary Fig. 11). Furthermore, the comparison of the O-C-O peak appearances in the X-ray photoelectron spectra of DHTA-Hz and DHTA-HZ-15C5 membranes further corroborated this conclusion (Fig. 2f and Supplementary Figs. 12, 13)41,42. To ensure that the reaction is not confined to the surface of the DHTA-Hz membranes, we conducted etching X-ray photoelectron spectroscopy (XPS) analysis on two types of membranes. The analysis results indicated that 15C5 is also present within the DHTA-Hz membrane. In the DHTA-Hz-15C5 membrane, the oxygen content in the pores at various depths is generally higher than that in the DHTA-Hz membrane (Supplementary Fig. 14). Such an interaction is crucial for modulating the selectivity and transport properties of the channel, which is essential for the membrane performance in ion separation processes.

Sodium selectivity of DHTA-Hz-15C5 membrane

The ion transport properties of DHTA-Hz and DHTA-HZ-15C5 membrane were investigated using current–voltage (I–V) measurements at room temperature in single–ion system. The membrane was placed in the middle of the testing cells with each filled with equal concentration of 0.1 M NaCl or KCl. To avoid interference from the base membrane, the AAO substrate was first tested (Supplementary Figs. 15, 16). All hydrated cations can pass through the channel and the ion transport rate through the AAO support is in the order of K+ > Na+. The DHTA-Hz membrane exhibit linear I–V curves for K+ and Na+ (Fig. 3b). The conductance value of KCl (21.52 μS) is slightly higher than that of NaCl (17.69 μS), indicating a relatively faster K+ transport rate compared to that of Na+, with a Na+/ K+ selectivity of 0.82. This is mainly because the one–dimensional pore size (8.4 Å) of DHTA-Hz membrane is larger than the hydrated diameter of Na+ (7.16 Å) and K+ (6.62 Å). All hydrated cations can pass through the channel, which is similar to that of AAO support.

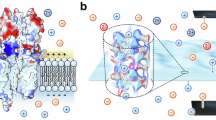

a Graph showing the ion separation, where COF channels and 15C5 pores recognize Na+ and facilitate Na+ translocation while preventing K+ from passing through. b Current–voltage (I − V) curves of a DHTA-Hz membrane with NaCl and KCl solutions. c I − V curves of a DHTA-Hz-15C5 membrane with NaCl and KCl solutions. d Ionic conductance of DHTA-Hz and DHTA-Hz-15C5 membranes with NaCl and KCl solutions. e Single–salt selectivity of AAO, DHTA-Hz and DHTA-Hz-15C5 membranes. f Ion permeation rates of DHTA-Hz and DHTA-Hz-15C5 membranes in the mixed ion system. g Ion selectivity of DHTA-Hz and DHTA-Hz-15C5 membranes in the mixed ion system. The error bar is the standard deviation from at least three samples, and the center of each error bar represents the average data from these samples. h Comparison of Na+/K+ selectivity obtained in this work with previously reported Na+/K+ selectivity data of other membranes and the permeability normalized by feed concentration.

After crown ether modification, the I–V characteristics of the DHTA-Hz-15C5 membrane (Fig. 3c) differed significantly from the AAO and DHTA-Hz membranes. Compared with the I–V curves of the DHTA-Hz membrane, the KCl currents of DHTA-Hz-15C5 decreased, and the conductance value of KCl decreased from 21.52 to 15.9 μS. This is primarily due to the narrowing of the ion transport channels from 8.4 Å to 6.0 Å after incorporating 15C5 into the one-dimensional pore size of the DHTA-Hz membrane. Conversely, the conductance value of NaCl significantly increased from 17.69 to 124.8 μS (Fig. 3d), despite the narrowing of the pores. This substantial enhancement in NaCl transport was attributed to the fact that the crown ether (15C5) within the nano-restricted domain COF channel could act as a specific binding site for Na+, thereby facilitating the transport of Na+. As a result, the Na+/K+ selectivity of the DHTA-Hz-15C5 membrane was significantly increased from 0.82 to 12.38 (Fig. 3e), which was much higher than that of the DHTA-Hz membrane and other membranes already reported (Supplementary Fig. 17 and Table S1). Our synthesized DHTA-Hz-15C5 membrane demonstrates a quite obvious binding effect of 15C5 to Na+ even in the single–ion system, which is very different from the membranes developed in previous studies12,40. In the single–salt experiments, the binding of Na+ to the crown ether 15C5 was significantly greater than K+ binding, which was attributed to the presence of the crown ether 15C5. Additionally, the –OH in the walls of the DHTA-Hz pore was observed to facilitate Na+ transport43,44,45. This conclusion is substantiated by the preparation of TFP-Hz membranes devoid of –OH groups (Supplementary Fig. 18). The oxygen–containing group, in conjunction with the oxygen present in the crown ether, resulted in the formation of an oxygen–rich environment within the slit pore, analogous to that observed in the inner cavity of the crown ether. This led to a comparable Na+ recognition ability and further promotion of Na+ transport, ultimately contributing to a high selectivity of Na+/K+. In the mixed system, the combined effect of the two resulted in facilitated Na+ diffusion within the membrane, while K+ diffusion was prevented, leading to a high Na+/K+ ion selectivity in both single salts and mixed salts (Fig. 3a).

Sodium–potassium ion selectivity in a solution mixture

The Na+/K+ selectivity and Na+ transport rate of DHTA-Hz and DHTA-Hz-15C5 membranes in the mixed salt system were also tested. Under electric field and concentration–driven configuration, a feed solution prepared by mixing equal molar amounts of 1.0 M KCl, and 1.0 M NaCl was added to the cell facing COF membrane for 12 h to drive ion permeation through the membranes (Supplementary Fig. 19). The monovalent cation concentrations in the permeate side were determined by inductively coupled plasma optical emission spectrometry and mass spectrometry (ICP–OES/MS). The ion permeation rates and ratios were then calculated on the basis of the concentrations to determine the ion flux and selectivity of the membranes. The observed ion permeation rates of the DHTA-Hz membrane followed the order of K+ > Na+, but DHTA-HZ-15C5 showed the opposite migration order, indicating that the DHTA-Hz-15C5 pair facilitated the transport of Na+ and inhibited the transport of K+ in the mixed solution system. Specifically, the permeation rate of Na+ increased to 9.33 mmol m−2 h−1, while that of K+ decreased significantly to 0.16 mmol m−2 h−1 respectively (Fig. 3f). Correspondingly, the mixed Na+/K+ selectivity of DHTA-Hz-15C5 was up to 58.31 (Fig. 3g), which is more four times of the selectivity in single–ion system due to the effect of competitive binding. This is a much higher selectivity than previously reported for membranes such as MOF and graphene (Fig. 3h, Supplementary Fig. 17 and Table S2).

For the binary ionic system, we tested it for up to 3 days using the concentration–driven diffusion method (Supplementary Fig. 20), and the results were consistent with the electrically driven test results, with the diffusion rate still Na+ > K+. However, the transmittance was slightly lower than the electric field–driven diffusion rate, the permeation of Na+ and K+ were 6.75 and 0.18 mmol m–2 h–1, respectively, which further suggests that the presence of the 15C5 facilitates the Na+ migration. In order to verify the structural stability of the DHTA-Hz-15C5 membrane after repeated stability tests, the membrane was characterized morphologically. Scanning electron microscopy surface images (Supplementary Fig. 21) and FTIR (Supplementary Fig. 22) of the DHTA-Hz-15C5 membrane showed that its structure remained intact after testing. Furthermore, after immersing DHTA-Hz-15C5 in deionized water for 5 days and analyzing its solution via nuclear magnetic carbon spectroscopy (Supplementary Fig. 23), no presence of 15C5 was detected. This further indicates that the crown ether stably exists within the COF channel. These results indicate that the DHTA-Hz-15C5 membrane has excellent structural and operational stability.

Ion Selectivity Mechanism of DHTA-Hz-15C5 Nanochannels

To further illustrate the passage of different ions through the domain–limited nanochannels, we performed DFT calculations. First, we calculated the energy barriers of various ions with hydrated water through the DHTA-Hz channel (Supplementary Fig. 24). As shown in Fig. 4a, the data indicated that all ion transport barriers were low throughout the transport channel, which suggests that one–dimensional COF channels facilitate ion transport. Notably, Na+ demonstrates a significantly lower transport barrier compared to K+, attributed to an abundance of –OH functional groups on the wall of the DHTA-Hz channels facilitating Na+ transport and ultimately achieving ultra–high Na+ permeation. However, due to the slightly larger pore size of DHTA-Hz relative to hydrated ions, all ions can partially shed water while crossing the COF pores; thus, precise ion separation cannot be achieved by DHTA-Hz membrane. Conversely, when ions with hydrated water pass through the 15C5 pore (Fig. 4b), they must release almost all bound water and traverse in their dehydrated form, resulting in a significantly higher energy barrier for transmembrane transport compared to passage through the COF channel. In contrast, when ions passed through the DHTA-Hz-15C5 channel (Fig. 4c), an obvious small volcanic form was observed for the energy barrier of transmembrane transport of all ions with K+ encountering a notably higher barrier than Na+, leading to rapid passage of Na+ through the channel while hindering and impeding K+ transmembrane transport. Furthermore, the change in energy barriers for both ions was simulated through the bilayer membrane structure (Supplementary Fig. 25), and in accordance with the results for the monolayer structure, the transport energy barriers for Na+ were found to be significantly lower than those for K+ throughout the process. Furthermore, a comprehensive investigation was conducted into the ionic transmembrane transport of these two ions in the two–dimensional structures of DHTA-Hz and DHTA-Hz-15C5 (Supplementary Figs. 26, 27). The results demonstrate that the energy barrier required for Na+ transport is significantly lower than that of K+, thus further substantiating the impact of the oxygen–rich environment of the COF functional group and the crown ether on the intramembrane transport of Na+, which also inhibits the transport of K+. This ultimately resulted in an ultra–high separation effect.

Energy barriers of ions transporting through the (a) DHTA-Hz, (b) 15C5, and (c) DHTA-Hz-15C5 channels. Mean square displacement (MSD) of ions transporting through (d) DHTA-Hz and (e) DHTA-Hz-15C5 channels with time. f Schematic diagram of ion transport behavior through DHTA-Hz-15C5 channels. g Simplified scheme of completely dehydrated ions transporting through the DHTA-Hz-15C5 channels.

To investigate the ion–selective transport properties of DHTA-Hz and DHTA-Hz-15C5 membranes driven by concentration gradients and electric field, we used molecular dynamics simulations (Fig. 4f and Supplementary Figs. 28–33). The experimental results show that the pore sizes of the DHTA-Hz membranes are much larger than those of the various hydrated ions, and thus all ions can pass through the pores (Supplementary Fig. 34). In this case, the theoretical diffusion order is K+ > Na+ (Fig. 4d), which is consistent with the experimental observations. On the contrary, the ions underwent a process from partial dehydration to complete dehydration and finally to hydration (Supplementary Fig. 34) by diffusion through DHTA-Hz-15C5 with the order of diffusion being Na+ > K+(Fig. 4e) further demonstrating the preferential transport of sodium ions by 15C5 to the exclusion of K+ ions throughout the process, and thus the system achieved a high Na+/K+ separation (Fig. 4g).

To verify the generality of the method, we incorporated the crown ether (18C6), known for its specific binding affinity for K+, into the DHTA-Hz channel. This resulted in high selectivity for K+/Na+ (supplementary Figs. 35–44). Specifically, the selectivity of the DHTA-Hz–18C6 channel for K+/Na+ was determined to be 7.38 in single–ion system (Supplementary Figs. 45, 46). In contrast, within the mixed salt system, the mixing selectivity of DHTA-Hz-18C6 for K+/Na+ was notably elevated, reaching 36.37 (Supplementary Fig. 47). This outcome validates the significant role of incorporating crown ether molecules with ion recognition capability into the COF pore in facilitating selective ion separation.

In summary, single-ion transport channels have been constructed by introducing crown ether into the COF pores. The crown ethers are confined in the sub-nanochannels to form stable COF membrane channels with selective single-ion transport, due to the precise lumen dimensions and electrostatic interaction with binding sites. The ion selectivity of the DHTA-Hz-15C5 membrane was 58.31 with a permeation of 9.33 mmol m−2 h−1. The mechanism of the selective ion transport is revealed experimentally as well as by means of DFT calculations and MD simulations as follows: Firstly, the one–dimensional pore structure of COF facilitates ion transport, leading to a significant enhancement in ion permeation. Secondly, the constriction of COF pores subsequent to the introduction of crown ether molecules promotes the separation of monovalent ions. Thirdly, the selective recognition capability of crown ether molecules imparts COF membranes with the ability for selective recognition, enabling the membrane to achieve specific recognition and separation functions.

Methods

Material and chemicals

Hydrazine hydrate ( > 99%,) was purchased from Sigma (Shanghai, China). 15–crown–5 (98.0%) was obtained from Energy Chemical (Anhui, China). 18–crown–6 (95%) was received from Aladdin (Shanghai, China). Ethanol (C2H5OH; 99.7%) and analytical grade KCl, and NaCl were obtained from China National Pharmaceutical Group Industry Co. Ltd. (Beijing, China). All reagents and solvents were used as received, without further purification. DI water was used throughout the experiments. AAO (Hefei Pu– Yuan Nano Technology Ltd.) discs were used as substrates.

Membrane synthesis

The DHTA-Hz selective layer was formed on the AAO surface using interfacial polymerization. A self–made diffusion cell, as shown in Supplementary Fig. 1, was used for the experiment. The volume of the diffusion cell was 7 mL. To prepare the aqueous phase solution, hydrazine hydrate (2.2 mg, 0.044 mmol) and p–toluene sulfonic acid (7.6 mg, 0.044 mmol) were dissolved in deionized water (20 mL). The organic phase was prepared by dissolving 2,4–dihydroxybenzene–1,3,5–tricarbaldehyde (DHTA) (8 mg, 0.04 mmol) in toluene (20 mL) solution. The AAO was soaked in the above aqueous solution and placed in the diffusion tank. Then the aqueous phase and organic phase liquid were slowly added to both sides of the diffusion cell, and the diffusion cell was stored at 30 °C for 3 days. Next, the membrane material was rinsed with methanol and deionized water to remove residual monomers, catalysts, and organic solvents. Finally, the obtained membrane material was soaked in water, naturally dried, and subjected to subsequent testing and characterization.

To synthesize the DHTA-Hz-15C5 membrane, the DHTA-Hz membrane was immersed in an aqueous solution containing crown ether (15C5) at 80 °C overnight. After treatment with anhydrous ethanol and deionized water, the membrane was dried and prepared for subsequent testing and characterization. DHTA-Hz–18C6 membranes were prepared following the same methodology.

Membrane and Material characterization

Powder X–ray diffraction (PXRD) was employed to identify the crystalline structure of the DHTA-Hz membranes. DHTA-Hz membranes were ground into powder and tested at a 2θ range of 5–40°. X–ray photoelectron spectroscopy (XPS) was used to analyze the elemental composition and chemical structure of the membranes. Solid state 13C NMR spectra and attenuated total reflectance Fourier transform infrared spectroscopy (ATR–FTIR) were taken to identify the chemical structure of the membranes. All samples were prepared in the same way as for the PXRD characterization. Wide-angle X-ray scattering (WAXS) measurements were conducted on a XEUSS 2.0 instrument producted by XENOCS, employing a high intensity rotating anode X-ray generator. The NMR experiment was performed at 25 °C on a AscendTM 600 MHz liquid NMR spectrometer. To characterize the membrane pore size, high–purity nitrogen was used throughout to measure the adsorption–desorption isotherm at 77 K by using a surface aperture analyzer. The membranes were collected and ground into powder. The obtained powder sample was degassed at 120 °C for 10 h under vacuum before measurement. The Brunauer–Emmett–Teller (BET) surface area was determined by measuring the N2 adsorption isotherms at 77 K in the liquid nitrogen bath and the pore size distribution was calculated with nonlocal density functional theory (NLDFT)46.

Scanning electron microscopy (SEM) images were performed to analyze the surface and cross–sectional morphologies of membrane samples. For the cross–section observation, the membrane samples were manually fractured in liquid nitrogen. All membrane samples were coated with a thin layer of Au.

TGA thermograms were recorded using a TGA Q2000 V3.15 analyzer at a heating rate of 10 °C min–1 under the N2 atmosphere and normalized at 100 °C to minimize the influence of extra water.

Current–voltage measurements

The ionic transport properties of all membranes were studied by measuring current–voltage I–V curves using a CHI 760E potentiostat. I–V plots were acquired to compare the ion transport characteristics of the DHTA-Hz and DHTA-Hz-15C5/18C6 composite membranes. Experiments were performed in a two–compartment transport cell at room temperature. The membrane was sandwiched between the two compartments, with an effective test area of 19.625 mm2. Ag/AgCl electrodes were inserted into the feed and receiving solutions, both containing 50 mL of 0.1 M KCl, NaCl, or LiCl. Before electrical measurements, the device was equilibrated for 10 min to reach steady–state conditions.

Ion permeation experiments

The DHTA-Hz or DHTA-Hz –15C5 membrane was clamped between two PTFE compartments. One compartment, facing the COF membrane, served as the feed solution and was filled with 50 mL of salt solution, while the other compartment served as the permeate solution and contained 50 mL of Milli–Q water. For the mixed ion permeation experiments, the feed solution (50 mL) contained 1.0 M NaCl and 1.0 M KCl. At the end of the experiments, the ion concentrations in the permeate side were measured by ICP–OES/MS. Permeation rates and permeability ratios were calculated to evaluate the monovalent ion transport and selectivity of the membranes.

The permeation rate (Pi, mmol m−2 h−1) of cations was calculated using Eq. (1):

where C (mg/L) was the cation concentration in permeated side, V (mL) was the effective volume of the solution in permeated side (V was 50 mL in this work), Mr (g mol−1) was the relative molecular mass of cation, A (mm2) was the effective permeated area, and Δt (h) was the permeated time.

The ideal or mixed-ion selectivity of COF membranes using Eq. (2):

where Pi (mmol m−2 h−1) and Pj (mmol m−2 h−1) were the permeation rate of cation i and j, respectively; ΔCi (mol L−1) and ΔCj (mol L−1) were the concentration gradient of cation i and j.

Molecular dynamics (MD) simulation

Molecular dynamics (MD) simulations were carried out to calculate the permeation rate of Na+ and K+ through the DHTA-Hz and DHTA-Hz-15C5 membranes under an electric field of 1 V/Å in NaCl, KCl and LiCl aqueous solution, respectively. The diffusion coefficients can be estimated from the slope of the mean square displacement (MSD) curves by the Einstein relationship47. All MD simulations were performed utilizing the Forcite module in Materials Studio (MS) 2020. The aqueous solution contained ions and H2O molecules, while the pure water box comprised solely of H2O molecules. The COMPASS III force field48,49 was employed to optimize the interface model and run MD simulations under an electric field of 1 V/Å in the NVT ensemble (T = 298 K) with a time step of 1.0 fs and a total simulation time of 300 ps. Trajectories were recorded at 3 ps intervals for MSD calculation and counting the number of ions through the membrane.

Density functional theory (DFT) calculations

The energy barriers of cations, namely Na+, K+ and Li+, through 15C5, DHTA-Hz and DHTA-Hz-15C5 were respectively calculated by DFT calculation utilizing Dmol3 module in Materials Studio 2020. The generalized gradient approximation (GGA) with Perdew–Burke–Ernzerhof (PBE) exchange–correlation functional was employed to fully relax 15C5, DHTA-Hz and DHTA-Hz-15C5. Double–numeric quality basis sets with polarization functions (DNP basis set) were used. The iterative tolerances for energy change, force and displacements were 1 × 10−5 Ha, 0.002 Ha Å−1and 0.005 Å, respectively. The self–consistent field (SCF) procedure used a convergence standard of 10−6 a.u. After structure optimization, the cation was positioned 5 Å above the mass center plane. The cation was then moved downward in 1 Å increments until a relative position –5 Å was reached. Energy barriers were calculated during this movement process.

Data availability

All data are available within the article and its Supplementary Information files. Additional data related to this paper may be requested from the corresponding authors. Source data are provided with this paper.

References

Jentsch, T. J., Hübner, C. A. & Fuhrmann, J. C. Ion channels: function unravelled by dysfunction. Nat. Cell Biol. 6, 1039–1047 (2004).

Maffeo, C., Bhattacharya, S., Yoo, J., Wells, D. & Aksimentiev, A. Modeling and simulation of ion Channels. Chem. Rev. 112, 6250–6284 (2012).

Li, Z. et al. Structural basis for pore blockade of the human cardiac sodium channel Nav1.5 by the antiarrhythmic drug quinidine. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 60, 11474–11480 (2021).

Ye, T. et al. Artificial sodium–selective ionic device based on crown–ether crystals with subnanometer pores. Nat. Commun. 12, 5231 (2021).

Culp, T. E. et al. Nanoscale control of internal inhomogeneity enhances water transport in desalination membranes. Science 371, 72–75 (2021).

Li, T. et al. Developing fibrillated cellulose as a sustainable technological material. Nature 590, 47–56 (2021).

Wang, M., Hou, Y., Yu, L. & Hou, X. Anomalies of ionic/molecular transport in nano and sub–nano confinement. Nano Lett. 20, 6937–6946 (2020).

Zhang, Z., Wen, L. & Jiang, L. Nanofluidics for osmotic energy conversion. Nat. Rev. Mater. 6, 622–639 (2021).

Yu, X. et al. Gating effects for ion transport in three-dimensional functionalized covalent organic frameworks. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 61, e202200820 (2022).

Wang, W. Z. et al. Light–driven molecular motors boost the selective transport of alkali metal ions through phospholipid bilayers. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 143, 15653–15660 (2021).

Zhang, H., Li, X., Hou, J., Jiang, L. & Wang, H. Angstrom–scale ion channels towards single–ion selectivity. Chem. Soc. Rev. 51, 2224–2254 (2022).

Lu, J. et al. An artificial sodium–selective subnanochannel. Sci. Adv. 9, eabq1369 (2023).

Lawal, O. et al. An artificial sodium ion channel from calix[4]arene in the 1,3–alternate conformation. Supramol. Chem. 21, 55–60 (2010).

Choy, E. M., Evans, D. F. & Cussler, E. L. Selective membrane for transporting sodium ion against its concentration gradient. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 96, 7085–7090 (2002).

Abraham, J. et al. Tunable sieving of ions using graphene oxide membranes. Nat. Nanotechnol. 12, 546–550 (2017).

Ma, L. et al. Artificial monovalent metal ion–selective fluidic devices based on crown ether@metal–organic frameworks with subnanochannels. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 14, 13611–13621 (2022).

Qiu, M. et al. Large–scale metal–organic framework nanoparticle monolayers with controlled orientation for selective transport of rare–earth elements. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 145, 12275–12283 (2023).

Wang, L. et al. The chemical stability of metal-organic frameworks in water treatments: Fundamentals, effect of water matrix and judging methods. Chem. Eng. J. 450, 138215 (2022).

Wang, C., Liu, X., Keser Demir, N., Chen, J. P. & Li, K. Applications of water stable metal-organic frameworks. Chem. Soc. Rev. 45, 5107–5134 (2016).

Xian, W., Wu, D., Lai, Z., Wang, S. & Sun, Q. Advancing ion separation: covalent–organic–framework membranes for sustainable energy and water applications. Acc. Chem. Res. 57, 1973–1984 (2024).

Li, X. et al. Chemically robust covalent organic frameworks: progress and perspective. Matter 3, 1507–1540 (2020).

Yuan, J. et al. Photo–tailored heterocrystalline covalent organic framework membranes for organics separation. Nat. Commun. 13, 3826 (2022).

Ren, L., Chen, J., Han, J., Liang, J. & Wu, H. Biomimetic construction of smart nanochannels in covalent organic framework membranes for efficient ion separation. Chem. Eng. J. 482, 148907 (2024).

Li, Q. et al. Covalent organic framework interlayer spacings as perfectly selective artificial proton channels. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 63, e202402094 (2024).

Yuan, Y. et al. Selective scandium ion capture through coordination templating in a covalent organic framework. Nat. Chem. 15, 1599–1606 (2023).

Guo, R. et al. Aminal-linked covalent organic framework membranes achieve superior ion selectivity. Small 20, 2308904 (2023).

Yuan, S. et al. Covalent organic frameworks for membrane separation. Chem. Soc. Rev. 48, 2665–2681 (2019).

Chafiq, M., Chaouiki, A. & Ko, Y. G. Advances in COFs for energy storage devices: harnessing the potential of covalent organic framework materials. Energy Stor. Mater. 63, 103014 (2023).

Li, J. et al. Bulk COFs and COF nanosheets for electrochemical energy storage and conversion. Chem. Soc. Rev. 49, 3565–3604 (2020).

Han, W. et al. Constructing Cu ion sites in MOF/COF heterostructure for noble–metal–free photoredox catalysis. Appl. Catal. B Environ. 317, 121710 (2022).

Shah, S. S. A. et al. Covalent organic frameworks (COFs) for heterogeneous catalysis: recent trends in design and synthesis with structure–activity relationship. Mater. Today 67, 229–255 (2023).

Wang, H. et al. Covalent organic framework membranes for efficient separation of monovalent cations. Nat. Commun. 13, 7123 (2022).

Meng, Q. W. et al. Enhancing ion selectivity by tuning solvation abilities of covalent–organic–framework membranes. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. 121, e2316716121 (2024).

Xu, X. et al. Pore partition in two–dimensional covalent organic frameworks. Nat. Commun. 14, 3360 (2023).

Cao, L. et al. Switchable Na+ and K+ selectivity in an amino acid functionalized 2D covalent organic framework membrane. Nat. Commun. 13, 7894 (2022).

Violet, C. et al. Designing membranes with specific binding sites for selective ion separations. Nat. Water 2, 706–718 (2024).

Li, J. et al. Charging Metal-organic framework membranes by incorporating crown ethers to capture cations for ion sieving. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 62, e202309918 (2023).

Maia, R. A., Oliveira, F. L., Nazarkovsky, M. & Esteves, P. M. Crystal engineering of covalent organic frameworks based on hydrazine and hydroxy–1,3,5–triformylbenzenes. Cryst. Growth Des. 18, 5682–5689 (2018).

Lu, J. et al. Large–scale synthesis of azine–linked covalent organic frameworks in water and promoted by water. N. J. Chem. 43, 6116–6120 (2019).

Xu, T. et al. Perfect confinement of crown ethers in MOF membrane for complete dehydration and fast transport of monovalent ions. Sci. Adv. 10, eadn0944 (2024).

Xu, R. et al. Reversible pH–Gated mxene membranes with ultrahigh mono–/divalent–ion selectivity. Environ. Sci. Technol. 58, 6835–6842 (2024).

Ishimaru, K., Hata, T., Bronsveld, P., Meier, D. & Imamura, Y. Spectroscopic analysis of carbonization behavior of wood, cellulose and lignin. J. Mater. Sci. 42, 122–129 (2006).

Shan, Y. et al. Sodium storage in triazine–based molecular organic electrodes: the importance of hydroxyl substituents. Chem. Eng. J. 430, 133055 (2022).

Wang, H. et al. Oxygen functional group modification of cellulose–derived hard carbon for enhanced sodium ion storage. ACS Sustain. Chem. Eng. 7, 18554–18565 (2019).

Xie, X., Ao, Z., Su, D., Zhang, J. & Wang, G. MoS2/Graphene composite anodes with enhanced performance for sodium-ion batteries: the role of the two-dimensional heterointerface. Adv. Funct. Mater. 25, 1393–1403 (2015).

Ma, H. et al. Cationic Covalent Organic Frameworks: a simple platform of anionic exchange for porosity tuning and proton conduction. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 138, 5897–5903 (2016).

Yao, L. et al. Insights into the nanofiltration separation mechanism of monosaccharides by molecular dynamics simulation. Sep. Purif. Technol. 205, 48–57 (2018).

Sun, H., Ren, P. & Fried, J. The COMPASS force field: parameterization and validation for phosphazenes. Comput. Theor. Polym. Sci. 8, 229–246 (1998).

Sun, H. COMPASS: An ab initio force–field optimized for condensed–phase applicationsoverview with details on alkane and benzene compounds. J. Phys. Chem. B. 102, 7338–7364 (1998).

Acknowledgements

This study was financed by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (No. 52370137 awarded to S.Y.) and the National Key Research and Development Program of China (2023YFC3207404, 2022YFA1205603 both awarded to J.Y.). Additionally, we would also like to thank the Analytical and Testing Center of Huazhong University of Science and Technology (HUST) for providing experimental measurements and the School of Environmental Science and Engineering of HUST for the supply of instruments for materials analysis.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

P.J. and S.Y. supervised the project. J.W. and H.T. designed, fabricated, and tested the COF membranes. H.W. developed the COF synthesis procedure. Z.D., J.Z. and J.Y. participated in the discussion. J.W., P.J., S.Y., and M.E. wrote the paper. read and revised the paper.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Peer review

Peer review information

Nature Communications thanks the anonymous reviewers for their contribution to the peer review of this work. A peer review file is available.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Source data

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Wang, J., Zhang, J., Jin, P. et al. A covalent organic framework membrane with highly selective and permeable artificial sodium channels via ion recognition. Nat Commun 16, 7346 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-025-62329-1

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-025-62329-1