Abstract

Soil carbon stocks on the Tibetan Plateau are widely considered to be increasingly threatened by drastic climate warming and intensified livestock grazing. But it remains elusive due to unconstrained model projections. Here we integrate large-scale soil campaigns, soil incubation with paired grazing experiments to project impacts of climate change and grazing on soil carbon stocks in a three-pool soil carbon model. While Tibetan soils will act as a carbon sink, over half of the gains occur in active or unprotected pools, making them vulnerable to extreme events and grazing. Although thermokarst processes may not reverse this trend, continued livestock grazing at current levels, or even a transition to a forage-livestock balanced state, could nearly offset climate-induced benefits. We highlight the critical need to optimize grazing to sustain soil carbon sinks on the Tibetan Plateau, and emphasize the importance of incorporating grazing impacts on soil carbon stocks into Earth system models.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The Tibetan Plateau is the world’s largest alpine permafrost region, holding vast reserves of organic carbon in its soils1,2. Near-surface air temperatures are rising at more than twice the global average, a trend projected to persist through the end of the century3. This warming is expected to accelerate soil carbon decomposition, particularly in permafrost-affected regions4, offsetting gains from increased vegetation productivity especially when temperatures approach or exceed the optimal thresholds for photosynthesis5. Consequently, this imbalance would threaten the stability of soil carbon stocks, and may ultimately tip the Tibetan soil carbon stocks. But whether this imbalance will definitely occur remain disputed. Previous estimates of climate-induced future soil carbon stock changes fall into the two distinct categories. The first category is to use model projections from Earth system models6, however which used a spatially-consistent soil turnover rate without any observational constraints7,8. The second one is to extrapolate the experimental data on climate sensitivity of soil carbon to project regional soil carbon responses into the future9,10. However, this simple statistical extrapolation fails to capture the complex processes governing long-term soil carbon dynamics11, and existing experiments on the Tibetan Plateau were predominantly focused on warming12, rather than multifactor climate change scenarios that more accurately represent future conditions.

In addition to climate change, livestock grazing, the primary form of subsistence for the inhabitants of the Plateau, can profoundly affect soil carbon through feeding and trampling13,14. Existing field studies have shown that Tibetan soil carbon pools decrease, remain unchanged or even increase in the presence of herbivory15,16,17. The underlying mechanisms driving these contrasting results remain poorly understood, complicating efforts to develop effective grazing policies for maintaining soil carbon stocks. Moreover, evidence from combined warming and grazing experiments suggests that grazing can mediate climate-induced changes in soil carbon18. The synergistic interactions between grazing and climate change may either amplify or offset their individual effects, further limiting our ability to project future soil carbon trajectories within a pastoral-based socioeconomic system.

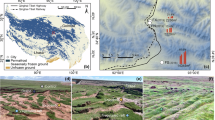

Here we aim to understand how Tibetan soil carbon stocks will respond to the dual force from rapid climate change and changes in livestock grazing. To do this, we first assemble the largest database of soil carbon observations to date (n = 4170) (Fig. 1 and Supplementary Fig. 1), incorporating the latest gridded soil sampling campaigns from 2019 to 2022, in situ measurements of soil carbon age with long-term soil incubation experiments to parameterize the reduced-complexity three-pool soil carbon model7. After calibrating the three-pool model, we project that Tibetan soils would continue to maintain carbon sinks in an amplified warming world. Furthermore, we analyzed 296 paired soil carbon observations from field grazing experiments across the Tibetan Plateau to identify the key drivers of variability in grazing impacts on soil carbon (Fig. 1). By extrapolating this empirical relationship across the plateau, we estimated grazing impacts under different combinations of warming and grazing scenarios, including a conservative forage-livestock balance assumption. In contrary to the prevailing view that climate change will destabilize Tibetan soil carbon stocks, we suggest that livestock grazing, instead of climate change, plays a dominant role in weakening soil carbon sinks.

Our study comprises 4170 soil profiles from multiple field surveying campaigns, 296 paired soil carbon observations from grazing experiments and 19 long-term soil incubation experiments. This map was created using R v4.4.1. The base map was obtained from the National Tibetan Plateau/Third Pole Environment Data Center (https://cstr.cn/18406.11.Geogra.tpdc.270099)67, and the vegetation distribution data were derived from 1:1 million vegetation map of China68. Both datasets are licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License (CC BY-NC-SA 4.0).

Results and discussion

Active carbon pool dominates future climate-induced soil carbon increases

Before projecting climate-induced soil carbon stock changes, we first integrated field measurements (n = 4170) of soil carbon density and associated environmental variables into a machine learning algorithm to model soil carbon stock at layers of 0–30 cm, 30–100 cm and 100–300 cm at a spatial resolution of 1 km, respectively (Supplementary Fig. 1 and Supplementary Table 1). Compared to previous estimates2,19,20, this assessment incorporates data from 667 newly collected sites from the most recent field campaign during 2019−2022 (Fig. 1), in addition to 1114 sites gathered during 11 previous field campaigns.

Our results showed that nitrogen availability plays a dominant role in shaping Tibetan soil carbon dynamics, with consistently positive effects across all three soil layers (Supplementary Fig. 2). Increased nutrient availability stimulates microbial community abundance21, which in turn promotes soil carbon accumulation through enhanced microbial necromass inputs22. In addition, climate, particularly precipitation, has a notable influence on soil organic carbon, while this influence decreases with increasing soil depth (Supplementary Fig. 3). In general, soil carbon tends to be higher in wetter regions, likely due to favorable climatic conditions that enhance plant productivity and subsequently increase carbon inputs into soils2,23,24. These findings highlight the importance of integrating both biotic and abiotic factors when assessing soil carbon responses to global changes.

We estimated that the total soil carbon stock at a depth of 3 m over the Tibetan Plateau was ~53 ± 13 PgC, with higher soil carbon density observed in warmer and wetter climate regimes especially for top 1 m soils (Supplementary Fig. 4). Of this total, the 0–30 cm, 30–100 cm, and 100–300 cm layers contributed 33%, 27%, and 40%, respectively (Supplementary Fig. 5). Among different ecosystem types, alpine meadows hold the largest soil carbon stock (18.3 ± 4.6 PgC), followed by shrublands (11.4 ± 2.7 PgC) and alpine steppes (9.6 ± 2.8 PgC), while alpine deserts (7.9 ± 1.5 PgC) and forests (5.7 ± 1.6 PgC) have the lowest stocks (Supplementary Fig. 5).

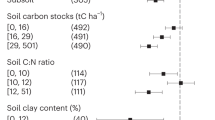

The soil carbon turnover time in a warming climate is one of the most uncertain and least constrained components of climate-induced soil carbon stock change7,25. To address this, we estimated the soil carbon turnover time as the intrinsic one (τi), which is not modified by either abiotic (e.g., climate change and mineral protection) or biotic factors (e.g., rhizosphere priming effect)7. We first assessed the τi of Tibetan soils for the fast, slow and passive soil carbon pools using 19 long-term soil incubation experiments (see Methods). Our analyses showed that mean annual precipitation (MAP), soil pH, and soil nitrogen were key factors controlling soil τi variability across the Tibetan Plateau (Fig. 2), though their effects differed among soil carbon pools. The τi of slow soil carbon pool is longer with lower precipitation, higher soil pH and poorer nutrient contents, which is contrasted to the fast soil carbon pool (Supplementary Fig. 6). This result is probably related to shifts in soil microbial compositions, for example, the relative abundance of soil fungi versus bacteria, which could vary significantly with environmental conditions26. Compared to bacteria, fungi, which often have lower turnover rates and prefer to decompose more recalcitrant substrates27,28, tend to dominate in less productive ecosystems with dry climates and nutrient-poor conditions29. We then extrapolated soil τi of different soil carbon pools from the site-level to the whole Tibetan Plateau using empirical relationships between soil τi and environmental variables. Our results showed that soil τi of the Tibetan Plateau is 0.34 (95%: 0.2–0.6) year, 7.9 (6.2–9.7) year and 369 (305–424) year for fast, slow and passive pools, respectively (Supplementary Fig. 7).

The values were derived from random forest models for the effects of 9 environmental variables on soil intrinsic turnover time (τi) of fast (a), slow (b) and passive (c) pools. These variables include normalized difference vegetation index (NDVI), mean annual temperature (MAT; °C), mean annual precipitation (MAP; mm), soil bulk density (g/cm3), soil pH value, soil organic carbon (g/kg), soil total nitrogen (g/kg), soil clay content (g/kg).

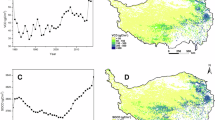

We then optimized environmental modifiers of soil τi by evaluating them against observations within a reduced-complexity three-pool model. Specifically, we calibrated these modifiers using both gridded soil carbon stock data (Supplementary Fig. 4) and upscaled field-based estimates of soil carbon age—derived from radiocarbon measurements as a proxy for in situ soil carbon turnover rate8—to minimize model-data mismatch over the historical period (see Methods). After using these observational-constrained parameters in a reduced-complexity three-pool model, we projected that Tibetan soils will become a carbon sink by 2060, with an uptake of 261 TgC and 292 TgC at a depth of 1 m under most-likely and worst-case warming scenarios (Fig. 3), respectively. While the soil carbon will increase across nearly all three soil carbon pools, our projections showed that the majority occurs in the active, easily-decomposed carbon pool, which contributes to 63–70% of the increases (Fig. 3g). Moreover, changes in soil carbon stock showed large spatial variations across the Tibetan Plateau (Fig. 3a, d). An enhanced soil carbon stock is most pronounced in alpine meadow (72, 68 and 0.93 TgC for fast, slow and passive carbon pools) and alpine steppe (48, 45 and 0.95 TgC), followed by shrubland (19, 13 and −0.12 TgC), while soil carbon stock of other ecosystems will exhibit a minor increase (e.g., alpine desert) or even decreases (e.g., forests) (Supplementary Table 2).

a−f Spatial patterns of changes in soil carbon (kgC m−2) under ‘future climate change’ (a, d), ‘current livestock grazing policy’ (b, e) and ‘forage-livestock balance’ (c, f) scenarios. g Soil carbon storage changes (TgC) under the above scenarios. Error bars in (g) represent standard deviation of five CMIP6 models. These maps were created using R v4.4.1, with the base map obtained from the National Tibetan Plateau/Third Pole Environment Data Center under a CC BY-NC-SA 4.0 license (https://cstr.cn/18406.11.Geogra.tpdc.270099)67.

Our results showed that soils of the Tibetan Plateau will continue to act as a carbon sink of 5.6–6.2 TgC year−1 by 2060. This contrasts with a recent synthesis study suggesting that field warming has non-significant impacts on soil carbon on the Tibetan Plateau (−1% to 5%; n = 74)30. The discrepancy probably arises because warming experiments do not take into account changes in precipitation, which often result in reduced soil moisture30. Furthermore, the majority of warming experiments (75%) simulated temperature increases of <2 °C, which is lower than the levels projected by climate models. Together, these two factors are likely insufficient to stimulate the plant productivity required to drive changes in soil carbon, resulting in no detectable responses in biomass or soil carbon across field warming experiments on the Tibetan Plateau30. In contrast, our analysis incorporates enhanced vegetation responses under warmer and wetter conditions on the Tibetan Plateau (see Methods, Supplementary Fig. 8), thereby more accurately capturing the combined effects on soil carbon dynamics. These results highlight the need for more field experiments that include multiple climate change factors to improve predictions of soil carbon dynamics under future climate change. We found that more than half of soil carbon increase will be occurring in the active soil carbon pool (Fig. 3g), despite this pool comprising only 2% of the total soil carbon stock7. The projected increase in active carbon storage is likely to be driven by increased plant-derived carbon inputs under future warmer and wetter climate conditions2. In addition, according to the carbon-quality temperature hypothesis31, the relatively low temperature sensitivity of active carbon decomposition may partly explain this trend. This result is consistent with a recent global synthesis32. The increasing proportion of active soil carbon indicates the increased vulnerability of Tibetan soil carbon stocks to extreme weather events and disturbances such as fire and grazing. We highlight the need for targeted management strategies to maintain the soil carbon sink in this fragile region.

In addition, our estimate of climate-induced changes in soil carbon stocks does not account for permafrost processes that potentially contribute to soil carbon destabilization33. While, we tentatively suggested that including these processes might not be able to reverse the projected increase in soil carbon stocks in a warmer future. For example, evidence is mounting that abrupt thaw of ice-rich permafrost, termed as thermokarst, could expose more soil carbon to microbial decomposition and enhance soil carbon loss34,35. A recent study estimated that thermokarst-affected soils on the northeastern Tibetan Plateau released an additional 422 ± 51 g C m⁻² yr⁻¹ compared to adjacent non-thermokarst landforms under 2 °C warming34. The simple extrapolation of this thermokarst-induced additional soil carbon release to upland regions with a high probability of thermokarst on the Tibetan Plateau (Supplementary Fig. 9) suggests a total soil carbon loss of 160 TgC, offsetting about 55% of the warming-induced soil carbon increases.

Grazing will reduce soil carbon stocks amid future climate change

In addition to climate change, livestock grazing is a major driver of changes in soil carbon stocks over the Tibetan Plateau36. However, the extent to which livestock grazing could amplify or offset climate change-induced increases remains unclear. To address this issue, we collected 296 paired (grazed vs. control) soil carbon observations from field grazing experiments on the Tibetan Plateau to evaluate the grazing impacts (see Methods). The effects of grazing on soil carbon stocks were variable, with positive, negative and neutral impacts observed across experimental sites (Supplementary Fig. 10). Our analysis showed that the direction and magnitude of these grazing-induced changes across sites are predictable across sites, as the soil clay content and the intensity of livestock grazing are important determinants (Fig. 4a), and the impacts of grazing intensity vary with stabilization capacities that are indicated by soil textural properties. In coarse-textured soils with weaker capacities (e.g., the clay content is <22%), the total soil carbon stock significantly decreased with increasing grazing intensity (Fig. 4b, P < 0.001, n = 133). However, in fine-textured soils with greater capacities (the clay content is >22%), the soil carbon stock initially increased with grazing intensity up to about 50% before declining (Fig. 4c).

a Variable importance of 12 predictors from random forest models. b, c Relationship between grazing intensity and the effects of grazing on soil carbon for different clay content classes. The black lines in (b) and (c) were based on linear (R2 = 0.23, P < 0.001, n = 133) and quadratic (R2 = 0.1, P = 0.05, n = 55) regression models, respectively, with 95% confidence intervals. We used grazing-induced aboveground biomass changes as an indicator of grazing intensity. NDVI, normalized difference vegetation index. MAT, mean annual temperature. MAP, mean annual precipitation. LRR, log response ratio.

These results are in accord with the grazing optimization hypothesis14,37 that compared to low grazing intensity, moderate grazing could enhance plant productivity and increase more root carbon inputs to soils14, leading to the carbon accumulation in fine-textured ones with greater stabilization capacities13. In contrast, on sandy soils, increased grazing intensity might instead accelerate soil drying and erosions through biomass removal38, which in turn reduces soil mineralogical capacity to hold organic carbon. In addition to soil texture, we also showed that mean annual temperature and soil nitrogen could also contribute to the variation in grazing-induced soil carbon changes (Fig. 4a).

We then generated a predictive model that could explain ~71% of the variance in grazing-induced soil carbon changes on the basis of the relationships between grazing-induced changes and environmental drivers (see Methods). We further applied this predictive model to project soil carbon changes across the Tibetan Plateau under the two grazing (that is, ‘current livestock grazing policy’ and ‘forage-livestock balance’) and two warming scenarios. Note that these two grazing scenarios represent future grazing practices that maintain current stocking rates and optimize grazing towards forage-livestock balance, respectively (Supplementary Fig. 11). Our results showed that livestock grazing will reduce soil carbon stocks of the Tibetan Plateau across all scenarios (Fig. 3b, c, e, f). Specifically, under the ‘current livestock grazing policy’ scenario, Tibetan soil carbon stocks at a depth of 1 m are projected to decrease by 259 ± 50 TgC under the most likely warming scenario, with this decline intensifying to 287 ± 54 TgC under the worst-case scenario by 2060 (Fig. 3g). In contrast, under the ‘forage-livestock balance’ scenario, grazing-induced soil carbon loss would be mitigated to 209–238 TgC under both warming scenarios (Fig. 3g). There is modeling evidence to show that the current stocking rate approaches or even exceeds the threshold in most grasslands of the Tibetan Plateau39. Our findings suggested that although the vegetation productivity of the Tibetan Plateau would be enhanced under warmer and wetter conditions (Supplementary Fig. 8), maintaining current grazing policies in the future may still be ineffective in preventing soil degradation. In addition, we observed that the interaction between grazing and warming could further exacerbate soil carbon loss (Fig. 3g), which is consistent with a meta-analysis showing that grazing-induced reductions in root carbon inputs could outweigh the positive effects of warming, leading a net loss of soil carbon across experiments that combined both factors18. Spatially, the effects of livestock grazing are contingent on the size of the initial soil carbon stock (Fig. 3), with great losses occurring in central and northeastern regions with high-standing soil carbon stocks (Supplementary Fig. 4).

By combining climate-induced and grazing-induced changes in soil carbon stocks, we found that grazing-induced soil carbon losses largely offset the warming-induced accumulation, resulting in a minimal net sink of only 0.06 TgC yr⁻¹ in soils by 2060 under the current livestock grazing policy (Fig. 5). If the grazing policy is switched to “forage-livestock balance” policy, the net carbon uptake (1.12 TgC yr−1) by 2060 in soils would become more than three times as large as that of the ‘current livestock grazing policy’ scenario (Fig. 5 and Supplementary Fig. 12). Spatially, the greatest soil carbon loss was observed mainly in the eastern regions of the Tibetan Plateau with a large population and a high-standing soil carbon stock (Fig. 5). However, due to the larger climate-induced soil carbon sink, the soils in western Tibetan Plateau exhibited a net carbon gain (Fig. 5a–d).

a−f Spatial patterns of net changes in soil carbon (kgC m−2) under ‘future climate change & current livestock grazing policy’ (a, c) and ‘future climate change & forage-livestock balance’ (b, d) scenarios. e Rates of change in soil carbon storage (TgC yr−1) by 2060 under different scenarios across five ESM models, with triangles representing the means. Box plots show 25th and 75th percentiles (box borders), medians (central black lines) and data ranges (whiskers). These maps were created using R v4.4.1, with the base map obtained from the National Tibetan Plateau/Third Pole Environment Data Center under a CC BY-NC-SA 4.0 license (https://cstr.cn/18406.11.Geogra.tpdc.270099)67.

Our analysis has several limitations. First, although our depth-specific models used to estimate soil carbon stocks across the Tibetan Plateau incorporate a wide range of environmental variables (Supplementary Fig. 13), the inherent uncertainty within several key datasets (e.g., soil nitrogen content) was not quantified in our analysis due to data constraints. This limitation warrants further investigation to better assess its potential impact on model predictions. Second, almost all grazing and soil incubation studies were conducted within the top one meter of soils on the Tibetan Plateau (Supplementary Fig. 13). More deep soil core sampling, incubations of varying durations to inform turnover parameters of deep soil carbon, as well as long-term monitoring of grazing impacts on deep soil carbon, particularly in underrepresented regions (Fig. 1), are highly necessary. Moreover, the estimated soil carbon changes due to climate change are subject to large uncertainties (Fig. 3g), highlighting the need to improve the reliability of climate and plant productivity projections within ESMs. Last, our study focused on the effects of livestock grazing, but other anthropogenic disturbances—such as grazing policy changes, urban expansion and increasing tourism—should also be considered in future research.

Overall, we used observational constraints on soil carbon turnover to project that Tibetan soils will continue to absorb atmospheric CO₂ in a warmer future, though at a magnitude roughly half of the soil carbon sink observed over the past two decades1. Our back-of-the-envelope calculation of emerging processes, such as permafrost-induced thermokarst in a warming world34, suggests their limited role in reversing soil carbon stock changes. However, most of the increase in Tibetan soil carbon stock has occurred in the active soil carbon pool, suggesting its heightened sensitivity to extreme events and decreasing soil organic carbon stability in a warming world.

Furthermore, maintaining livestock grazing systems at both the current intensity and a reduced intensity with a forage-livestock balanced state will still lead to soil carbon depletion, potentially fully offsetting climate-induced soil carbon accumulation. Reversing this soil carbon loss could be achieved by reducing grazing intensity. For instance, under a biophysical no-grazing scenario, soil carbon sequestration potential could reach ~5.51 TgC yr⁻¹ by 2060. But this approach could disrupt the socioeconomic activities that Tibetan communities rely on for their livelihoods. We instead emphasize sustainable management interventions, such as rotational grazing or periodic fencing40, which could not only prevent soil carbon depletion but also support local livelihoods. We called for a necessity of representing the vulnerability of soil carbon to livestock grazing in Earth system models that are used in climate change projections.

Methods

Mapping current soil carbon stocks across the Tibetan Plateau

Study area and soil carbon database

The Tibetan Plateau is the highest and largest plateau on Earth, with an average elevation of 4000 m above sea level. The mean annual temperature (MAT) in this area ranges from −4.9 °C to 6.1 °C, and mean annual precipitation (MAP) ranges from 76 mm to 598 mm19. Due to its unique environmental conditions, the Tibetan Plateau, the largest permafrost area in middle latitudes of the Northern Hemisphere, holds a large amount of soil organic carbon. To construct a comprehensive soil carbon database for this region, we combined data from a large-scale, standardized field survey and previous studies19,41. In 2019 and 2020, 1,608 soil samples were collected across the Tibetan Plateau. Specifically, following a standard sampling protocol, we established a 15 m transect at each site, and set up three 1 m × 1 m plots at the beginning, middle and end of the transect. After recording vegetation information and clipping aboveground biomass in each plot, soil samples were taken at 0−10 cm, 10−20 cm and 20−30 cm using soil cores, and then bulked and homogenized in the field. Soil samples were passed through a 2 mm sieve and air-dried for subsequent physical and chemical analysis of bulk density, organic carbon content, total nitrogen and pH. In addition, we collected 2,562 soil carbon data from previous studies that sampled to a maximum depth of 3 m over the last three decades19,41. In total, we obtained 4,170 soil carbon observations, covering a wide range of environmental conditions and vegetation types including alpine meadow, alpine steppe, alpine desert, forest and shrubland (Fig. 1; Supplementary Fig. 1).

Model training and upscaling

Given the substantial variation in soil carbon across depths (Supplementary Fig. 1b), we used depth-specific random forest (RF) models (using the R package randomForest version 4.7-1.1)42 to generate spatially explicit estimates of current soil carbon stocks at 0−30 cm, 30−100 cm, and 100−300 cm across the Tibetan Plateau. RF is a widely used machine learning algorithm with superior predictive performance compared to traditional statistical models and many deep learning approaches8. It could also effectively capture non-linear relationships and complex interactions between predictor variables through its ensemble of decision trees, without requiring prior specification of such interactions43. Climate-, plant- and soil-related variables, which have been shown to have important influences on the region’s soil carbon cycling19,20,44, were used as model inputs for upscaling (Supplementary Table 1). Specifically, these variables include normalized difference vegetation index (NDVI), modern climates and paleoclimates in the mid-Holocene and the Last Glacial Maximum (MAT and MAP), elevation, soil depth, soil pH, soil clay content, soil carbon content, soil nitrogen content, C:N ratio, soil cation exchange capacity and soil dissolved organic carbon. Given the considerable heterogeneity in sampling depths among studies, soil depth—including both upper and lower boundaries—was incorporated as a predictor variable in the models. For each independent data point, values were extracted from global gridded datasets based on location, sampling year and depth (Supplementary Table 1).

We used a grid-search procedure, with tenfold cross-validation, to select the best combination of hypermeters for the random forest model with the lowest cross-validation root mean square error (RMSE) (Supplementary Fig. 2). In addition to individual variable importance, we also evaluated potential interactions among predictors using the iml package (version 0.11.4) in R45, and found generally low interaction strengths (Supplementary Fig. 14). This suggests that complex interactions have limited influence on model performance, and that our model structure is adequate for accurately predicting soil carbon stocks on the Tibetan Plateau. We also tested the extent of our extrapolations and found that our soil samples spanned most environmental conditions of this region (Supplementary Fig. 13). The final depth-specific models yielded high predictive accuracy, with R2 values of 0.66 for 0–30 cm (n = 2721), 0.45 for 30–100 cm (n = 985), and 0.42 for 100–300 cm (n = 436) soil layers (Supplementary Fig. 2). Then, we used the best trained predictive models, combined with the gridded datasets at 1 km resolution (Supplementary Table 1), to upscale soil carbon stocks at a depth of 0–30 cm, 30–100 cm and 100–300 cm across the Tibetan Plateau (Supplementary Fig. 4). To quantify the uncertainty in soil carbon stock estimates, we performed a bootstrapping procedure. Specifically, we derived 100 random forest models with each model trained on an independent bootstrapped sample of the training data, and calculated the standard deviation of the 100 models’ predictions as model uncertainty (Supplementary Fig. 4).

Projecting Tibetan soil carbon changes under different warming scenarios

Deriving soil intrinsic carbon turnover times

To assess the intrinsic decomposability of different soil carbon pools across the Tibetan Plateau, we conducted a literature survey for long-term soil incubation experiments in Web of Science (WoS) and China National Knowledge Infrastructure (CNKI) databases using the terms “soil carbon”, “incubation”, “laboratory” and “Tibetan Plateau”. In the laboratory, soils were often incubated at constant temperatures while other environmental factors such as soil moisture were maintained at optimum levels46; moreover, long-term incubations lasting months to years could provide more information on the decomposability of slow-cycling carbon pools47. These metrics make laboratory soil incubation experiments an ideal and widely used approach to evaluate the intrinsic decomposability of different soil carbon pools. The searched literatures were included in this study only if (1) the soils were incubated longer than half of a year and under aerobic conditions; (2) initial soil carbon concentration must be provided. In total, we derived 19 incubation experiments over the Tibetan Plateau. For each experiment, we recorded time-series soil CO2 efflux data from tables or figures using the GetData (v.2.25) software.

We then used a three-pool carbon decomposition model (Eq. 1), together with the time-series CO2 data, to estimate pool-specific intrinsic carbon turnover times (τi)7,47. In this model, the observed soil respiration (SR) was separated into three carbon pools (that is, fast, slow and passive), each with a unique intrinsic decay rate (the inverse of τi).

where fp and τi,p represent the partitioning coefficient of total soil carbon content (Ctot) and intrinsic carbon turnover time for each pool (p), respectively. Using a deconvolution analysis47, we estimated the pool-specific soil τi for each experiment, and then normalized them from their own incubation temperatures to a common temperature of 15°C using an empirical temperature-Q10 relationship derived from Hamdi et al. (2013).

Variable importance and upscaling

For each of the three carbon pools, we used a random forest model, implemented in the randomForest R package (version 4.7-1.1), to quantify the relative importance of nine variables including mean annual temperature (MAT), mean annual precipitation (MAP), NDVI, soil pH, soil bulk density, soil clay content, soil carbon content, soil nitrogen content and C:N ratio. These random forest models explained 56–63% variations in soil τi within carbon pools. We then used these predictive relationships to upscale empirical soil τi of each carbon pool across the Tibetan Plateau to reveal the geographic patterns (Supplementary Fig. 7). In addition, we also obtained the distributions of carbon fractions of different carbon pools using the same approach.

Future projection

We integrated the data-driven soil carbon stock and soil τi datasets into a refined reduced-complexity three-pool model developed by Ren et al. (2024) to project Tibetan soil carbon dynamics to 2060 under two warming scenarios, namely most-likely (SSP2-4.5) and worse-case (SSP5-8.5) warming. This model is refined from a reduced-complexity three-pool model (Eq. 2), which has been shown to well capture the future Tibetan soil carbon dynamics simulated in five Earth system models (ESMs) (Supplementary Figs. 15–16)7, including ACCESS-ESM1-5, CESM2-WACCM, IPSL-CM6A-LR, NorESM2-LM and TaiESM1.

where NPP is net primary productivity, rf and rs are transfer coefficients for carbon flowing from fast to slow pools and from slow to passive pools, respectively. Cf, Cs, Cp represent the soil carbon stock of the fast, slow and passive pools, respectively. kf, ks and kp are the actual carbon decay rates (yr−1) derived from Eqs. (3–4).

Where τa denotes the actual carbon turnover time (yr), while τi denotes the intrinsic carbon turnover time (yr) at a reference temperature (Tref = 15 °C), respectively. T and P are the ambient temperature (°C) and precipitation (mm), respectively. F(T) is a Q10-based standard exponential function to represent the temperature modifier of τi. F(P) represents a moisture modifier that increases with annual precipitation, normalized to maximal annual precipitation. b is an exponent parameter.

It is important to note that, although recent studies have advocated the use of physically measured carbon fractions such as mineral-associated organic carbon (MAOC) and particulate organic carbon (POC) to improve understanding of soil carbon dynamics32, their application in our study is limited by methodological challenges (e.g., an increased number of parameters to optimize) and sparse data availability across the Tibetan Plateau. We therefore employed the reduced-complexity three-pool modeling approach that leverages observational constraints to parameterize key processes within a physically consistent modeling framework, providing a scientifically robust and pragmatic alternative under current data limitations.

In the refined model, soil intrinsic carbon decomposability is modified by not only climates but also soil mineral protection48 and rhizosphere priming effect49. While soil τi are directly taken from our data-driven estimates (Supplementary Fig. 7), other parameters including precipitation scalar b, temperature scalar Q10, as well as the transfer coefficients rf and rs, were optimized through minimizing errors between the observed and modeled carbon stocks of the three pools in each grid cell. Here the observed pool-specific carbon stocks were derived from our data-driven estimates at a depth of 1 m (Supplementary Fig. 4). In the optimization process, we used the 15 year mean (2000–2014) of climate derived from CRU50 and the satellite-based NPP derived from MODIS51 and Global Inventory Modeling and Mapping Studies52 as model inputs; moreover, the observation-driven soil carbon age dataset was used as a surrogate of τa8. After parameter calibration, we used climate and NPP for each year from 2000−2014 as model inputs and repeatedly run the refined model until it reached a steady state. Finally, we used bias-corrected MAT, MAP and NPP data from the five ESM projections to run the steady-state refined model to project changes in Tibetan soil carbon stocks in 2060 under the two warming scenarios7.

Upland thermokarst landscape estimation

The potential upland thermokarst landscape across Tibetan Plateau was quantified using a weighted geomorphic susceptibility framework35 that integrates six key landscape characteristics: permafrost types, ground ice content, sedimentary overburden thickness, topography, histel coverage (perennially frozen peatland soils defined in USDA Soil Taxonomy53), and vegetation types. These variables were selected based on their critical roles in thermokarst development, particularly their influence on land subsidence and lateral soil transport35,54. Typically, the steep slope, higher ground ice content, thick overburden and less histel coverage collectively drive hillslope destabilization in grasslands54.

The framework uses a subtractive score structure35, with a unique set of scores for each thermokarst landscape type (Supplementary Table 3). From a maximum score of 100, points are subtracted based on the landscape characteristic score that are considered to make a region less likely to have extensive thermokarst landscapes. The resulting score is categorized into five thermokarst landscape coverage classes (‘high’ [>75], ‘moderate’ [50–75], ‘low’ [25–50], and ‘none’ [<25]); each coverage class corresponds to an estimated fractional coverage of a region, with both a range and a mode for each class35.

Projecting changes in soil carbon stocks under different grazing scenarios

Data collection

We synthesized published field grazing studies from WoS and CNKI using the terms “soil carbon”, “grazing” and “Tibetan Plateau”. To be included, studies have to meet several criteria: (1) the livestock grazed should be large vertebrates (e.g. sheep and yak); (2) the study should measure at least one of soil carbon stock, soil carbon concentration or soil organic matter content; (3) site coordinates and soil depth information should be provided; (4) if the study includes experiments with different grazing durations, we select the experiment with the longest duration; and (5) for enclosure studies, plots that had been free of herbivores for >15 years were used as controls. This timeframe has been shown to allow soil carbon to respond adequately to the absence of herbivores55. The search process finally yielded 52 peer-reviewed studies.

For each study, in addition to soil carbon, we also collected data on site coordinates, aboveground plant biomass, soil depth (ranging from the top 5 cm to >1 m), soil pH, soil bulk density, soil organic matter, soil clay content, C:N ratio and grazing duration. Means, standard deviations and replicates were recorded for both ungrazed and grazed plots. Given the large effect of animal trampling on soil physical properties (e.g. bulk density)56, we focus here on changes in carbon stocks rather than changes in concentration. In this case, where studies only provided soil carbon concentration or soil organic matter content, we converted these to carbon stocks based on bulk density and depth; specifically, carbon concentration was calculated as organic matter/257. In total, we obtained 296 depth-specific paired soil carbon stock observations.

Meta-analysis and variable importance

We used the natural logarithm of the response ratio (LRR) to assess the grazing effects on soil carbon changes (Eq. 5).

With XC and XG as mean values of the variables in the ungrazed and grazed treatments, respectively. LRR was calculated using escalc function in metafor R package (version 4.8-0)58. The percentage change in soil carbon stocks was derived by the back-transformation of the response ratio ((eLRR - 1) × 100).

We identified potential drivers of grazing effects (LRR) on soil carbon across the Tibetan Plateau using random forest models (randomForest v4.7−1.1 package). The examined environmental variables include NDVI, annual mean temperature, annual precipitation, soil pH, soil bulk density, soil clay content, soil carbon content, soil nitrogen content, C:N ratio. In addition, we evaluated three experimental variables including sampling depth, duration and grazing intensity. In this study, we used aboveground biomass changes as an indicator of grazing intensity, which is widely used in previous studies14,59,60. The importance analysis showed that soil clay content and grazing intensity are important factors on the grazing effects on soil carbon. To explore whether there are interactive effects between the two variables, we performed recursive partitioning analyses using the R packages partykit v1.2-2261 and ggparty v1.0.062. Our analysis showed that the effect of grazing intensity on soil carbon changes was largely dependent on clay content, with a partitioning point at 22% of clay content.

Future projection

We used the predictive model to assess the potential vulnerability of Tibetan soil carbon stocks to grazing practices by 2060. Absolute changes in soil carbon stocks due to grazing were estimated by multiplying the estimated relative changes by our data-driven current soil carbon stocks (Supplementary Fig. 4). Notably, due to limited data availability (Supplementary Fig. 13), here we restricted our analysis to 1 m soils of the Tibetan Plateau. Detailed information on grided dataset used is given in Supplementary Table 1. For grazing intensity, we first compiled livestock numbers (e.g., yaks, sheep and goats) from the Chinese Statistical Yearbook for each county of the Tibetan Plateau. Then, we used conversion factors (4.5 for yaks and 0.9 for goats) to convert different livestock types to a common sheep unit, and downscaled to derive grid-level stocking rates (sheep units km-2) based on the ratio of the NDVI of a grid to the total NDVI of the county. Specifically, we designed two grazing scenarios based on the current stocking rate dataset and future productivity in 2060 derived from ESMs under the two warming scenarios above. In the first scenario, we estimated future stocking rates as a proportion of future NPP, but their ratios will remain at current levels (‘current livestock grazing policy’ scenario). In the second scenario, we assumed that grassland within each grid will be grazed at a sustainable stocking rate, defined as a ratio of about 0.55 of grassland productivity, which follows the industry standard “Calculation of reasonable livestock carrying capacity of natural grassland” by the Ministry of Agriculture and Rural Affairs of the People’s Republic of China (‘forage-livestock balance’ scenario).

We then used the following equation to convert the stocking rates of the two scenarios into grazing intensity (GI, %).

where TLU represents tropical livestock units. One TLU is equal to 250 kg liveweight, which is about 10 sheep units63. FI refers to grass feed intake, with a value of 1.1 tC yr−1 TLU−1 for the Tibetan Plateau60. GA is the grazing area per grid cell, derived from two grazing fraction datasets64,65. ANPP is aboveground net primary production, calculated by multiplying future NPP by the fraction of carbon allocated to belowground (fBNPP). Specifically, NPP was derived from MODIS and GIMMS3g, and BNPP was derived from observation-derived estimates66. FI, GA and fBNPP were assumed to be constant over time.

To assess the impact of grazing and its interactions with future climate on Tibetan soil carbon stocks, we used the predictive model trained above (R2 = 0.71) to carry out the following four simulations by 2060. First, we used the current grazing intensity and climate (MAT and MAP) to generate simulations under present-day conditions (S1). In the second simulation (S2), we used future grazing intensity together with bias-corrected MAT and MAP from ESMs to project soil carbon dynamics under the above two grazing and two warming scenarios. The third simulation (S3) used future climate data with current grazing intensity, while the fourth (S4) reversed this, using current climate data with future grazing intensity. Future changes in Tibetan soil carbon stocks due to grazing were calculated as S4–S1, while the interactions with climate change were calculated as S2–S3–S4–S1.

Data availability

The outputs of the Earth system models can be downloaded from the CMIP6 website (https://esgf-node.llnl.gov/projects/cmip6/). The WorldClim and CRU climate data are available at http://www.worldclim.com/version2 and https://crudata.uea.ac.uk/cru/data/hrg/, respectively. The global NPP databases of MODIS and GIMMS3g are available at http://files.ntsg.umt.edu/data/NTSG_Products/MOD17/ and https://wkolby.org/data-code/, respectively. The data supporting the findings of this study can be found at the Figshare data repository (https://figshare.com/s/a2564db0370f84a13f38). Source data are provided with this paper.

Code availability

Data analysis was carried out using R v.4.4.1 and MATLAB R2024a. The code used in this study is available at the Figshare data repository (https://figshare.com/s/a2564db0370f84a13f38).

References

Wang, T. et al. The current and future of terrestrial carbon balance over the Tibetan Plateau. Sci. China Earth Sci. 66, 1493–1503 (2023).

Ding, J. et al. Decadal soil carbon accumulation across Tibetan permafrost regions. Nat. Geosci. 10, 420–424 (2017).

Chen, R. et al. Surface air temperature changes over the Tibetan Plateau: Historical evaluation and future projection based on CMIP6 models. Geosci. Front. 13, 101452 (2022).

Koven, C. D., Hugelius, G., Lawrence, D. M. & Wieder, W. R. Higher climatological temperature sensitivity of soil carbon in cold than warm climates. Nat. Clim. Change 7, 817–822 (2017).

Zhang, Y. et al. Future reversal of warming-enhanced vegetation productivity in the Northern Hemisphere. Nat. Clim. Change 12, 581–586 (2022).

Shi, Z. et al. Global-scale convergence obscures inconsistencies in soil carbon change predicted by earth system models. AGU Adv. 5, e2023AV001068 (2024).

Ren, S. et al. Projected soil carbon loss with warming in constrained Earth system models. Nat. Commun. 15, 102 (2024).

Shi, Z. et al. The age distribution of global soil carbon inferred from radiocarbon measurements. Nat. Geosci. 13, 555–559 (2020).

Crowther, T. W. et al. Quantifying global soil carbon losses in response to warming. Nature 540, 104–108 (2016).

Wang, M. et al. Global soil profiles indicate depth-dependent soil carbon losses under a warmer climate. Nat. Commun. 13, 5514 (2022).

García-Palacios, P. et al. Evidence for large microbial-mediated losses of soil carbon under anthropogenic warming. Nat. Rev. Earth Environ. 2, 507–517 (2021).

Song, J. et al. Global change and China’s terrestrial carbon sink: a quantitative review of 30 years’ ecosystem manipulative experiments. Ecol. Monogr. 95, e70005 (2025).

McSherry, M. E. & Ritchie, M. E. Effects of grazing on grassland soil carbon: a global review. Glob. Change Biol. 19, 1347–1357 (2013).

Ren, S. et al. Historical impacts of grazing on carbon stocks and climate mitigation opportunities. Nat. Clim. Change 14, 380–386 (2024).

Sun, J. et al. Verification of the biomass transfer hypothesis under moderate grazing across the Tibetan plateau: a meta-analysis. Plant Soil 458, 139–150 (2021).

Yan, L. et al. Grazing significantly increases root shoot ratio but decreases soil organic carbon in Qinghai-Tibetan Plateau grasslands: a hierarchical meta-analysis. Land Degrad. Dev. 31, 2369–2378 (2020).

Zhang, Z. et al. Comprehensive analysis of grazing intensity impacts alpine grasslands across the Qinghai-Tibetan Plateau: a meta-analysis. Front. Plant Sci. 13, 1083709 (2023).

Zhou, G. et al. Effects of livestock grazing on grassland carbon storage and release override impacts associated with global climate change. Glob. Change Biol. 25, 1119–1132 (2019).

Ding, J. et al. The paleoclimatic footprint in the soil carbon stock of the Tibetan permafrost region. Nat. Commun. 10, 4195 (2019).

Han, D. et al. Shift in controlling factors of carbon stocks across biomes on the Qinghai-Tibetan Plateau. Environ. Res. Lett. 17, 074016 (2022).

Cui, Y. et al. Global patterns of nutrient limitation in soil microorganisms. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 122, e2424552122 (2025).

Cao, Y. et al. Necromass-derived soil organic carbon and its drivers at the global scale. Soil Biol. Biochem. 181, 109025 (2023).

Wang, Y., Xia, A. & Xue, K. Cold and humid climates enrich soil carbon stock in the third pole grasslands. Innovation 5, 100545 (2024).

Song, X.-D. et al. Significant loss of soil inorganic carbon at the continental scale. Natl. Sci. Rev. 9, nwab120 (2022).

He, Y. et al. Radiocarbon constraints imply reduced carbon uptake by soils during the 21st century. Science 353, 1419–1424 (2016).

Yang, T. et al. Soil fungal diversity in natural grasslands of the Tibetan Plateau: associations with plant diversity and productivity. N. Phytol. 215, 756–765 (2017).

Rousk, J. & Bååth, E. Fungal biomass production and turnover in soil estimated using the acetate-in-ergosterol technique. Soil Biol. Biochem. 39, 2173–2177 (2007).

Strickland, M. S. & Rousk, J. Considering fungal: bacterial dominance in soils–methods, controls, and ecosystem implications. Soil Biol. Biochem. 42, 1385–1395 (2010).

Yu, K. et al. The biogeography of relative abundance of soil fungi versus bacteria in surface topsoil. Earth Syst. Sci. Data 14, 4339–4350 (2022).

Chen, Y. et al. Warming has a minor effect on surface soil organic carbon in alpine meadow ecosystems on the Qinghai–Tibetan Plateau. Glob. Change Biol. 28, 1618–1629 (2022).

Craine, J. M., Fierer, N. & McLauchlan, K. K. Widespread coupling between the rate and temperature sensitivity of organic matter decay. Nat. Geosci. 3, 854–857 (2010).

Liu, M. et al. Unprotected carbon dominates decadal soil carbon increase. Nat. Commun. 16, 2008 (2025).

Schädel, C. et al. Earth system models must include permafrost carbon processes. Nat. Clim. Change 14, 114–116 (2024).

Wang, G. et al. Enhanced response of soil respiration to experimental warming upon thermokarst formation. Nat. Geosci. 17, 532–538 (2024).

Olefeldt, D. et al. Circumpolar distribution and carbon storage of thermokarst landscapes. Nat. Commun. 7, 13043 (2016).

Wang, Y. et al. Grassland changes and adaptive management on the Qinghai–Tibetan Plateau. Nat. Rev. Earth Environ. 3, 668–683 (2022).

McNaughton, S. Grazing as an optimization process: grass-ungulate relationships in the Serengeti. Am. Nat. 113, 691–703 (1979).

Bai, Y. & Cotrufo, M. F. Grassland soil carbon sequestration: Current understanding, challenges, and solutions. Science 377, 603–608 (2022).

Zhu, Q. et al. An early warning signal for grassland degradation on the Qinghai-Tibetan Plateau. Nat. Commun. 14, 6406 (2023).

Sun, J. et al. Reconsidering the efficiency of grazing exclusion using fences on the Tibetan Plateau. Sci. Bull. 65, 1405–1414 (2020).

Chen, L. et al. Changes of carbon stocks in alpine grassland soils from 2002 to 2011 on the Tibetan Plateau and their climatic causes. Geoderma 288, 166–174 (2017).

Liaw, A. & Wiener, M. Classification and regression by randomForest. R. N. 2, 18–22 (2002).

Wright, M. N., Ziegler, A. & König, I. R. Do little interactions get lost in dark random forests?. BMC Bioinforma. 17, 1–10 (2016).

Jiang, L. et al. Assessment of frozen ground organic carbon pool on the Qinghai-Tibet Plateau. J. Soils Sediment. 19, 128–139 (2019).

Ullah, M. I., Aslam, M. & Altaf, S. lmridge: A comprehensive R package for ridge regression. R. J. 10, 326 (2018).

Hamdi, S., Moyano, F., Sall, S., Bernoux, M. & Chevallier, T. Synthesis analysis of the temperature sensitivity of soil respiration from laboratory studies in relation to incubation methods and soil conditions. Soil Biol. Biochem. 58, 115–126 (2013).

Schädel, C. et al. Circumpolar assessment of permafrost C quality and its vulnerability over time using long-term incubation data. Glob. Change Biol. 20, 641–652 (2014).

Sulman, B. N., Phillips, R. P., Oishi, A. C., Shevliakova, E. & Pacala, S. W. Microbe-driven turnover offsets mineral-mediated storage of soil carbon under elevated CO2. Nat. Clim. Change 4, 1099–1102 (2014).

Keuper, F. et al. Carbon loss from northern circumpolar permafrost soils amplified by rhizosphere priming. Nat. Geosci. 13, 560–565 (2020).

Harris, I., Osborn, T. J., Jones, P. & Lister, D. Version 4 of the CRU TS monthly high-resolution gridded multivariate climate dataset. Sci. Data 7, 109 (2020).

Zhao, M. & Running, S. W. Drought-induced reduction in global terrestrial net primary production from 2000 through 2009. Science 329, 940–943 (2010).

Kolby et al. Large divergence of satellite and Earth system model estimates of global terrestrial CO2 fertilization. Nat. Clim. Change 6, 306–310 (2016).

Tarnocai, C. et al. Soil organic carbon pools in the northern circumpolar permafrost region. Glob. Biogeochem. Cycles https://doi.org/10.1029/2008GB003327 (2009).

Jorgenson, M. & Osterkamp, T. Response of boreal ecosystems to varying modes of permafrost degradation. Can. J. For. Res. 35, 2100–2111 (2005).

Hu, Z. et al. A synthesis of the effect of grazing exclusion on carbon dynamics in grasslands in China. Glob. Change Biol. 22, 1385–1393 (2016).

Schmitz, O. J. et al. Animals and the zoogeochemistry of the carbon cycle. Science 362, eaar3213 (2018).

Pribyl, D. W. A critical review of the conventional SOC to SOM conversion factor. Geoderma 156, 75–83 (2010).

Viechtbauer, W. Conducting meta-analyses in R with the metafor package. J. Stat. Softw. 36, 1–48 (2010).

Chang, J. et al. Climate warming from managed grasslands cancels the cooling effect of carbon sinks in sparsely grazed and natural grasslands. Nat. Commun. 12, 118 (2021).

Fetzel, T. et al. Quantification of uncertainties in global grazing systems assessment. Glob. Biogeochem. Cycles 31, 1089–1102 (2017).

Hothorn, T. & Zeileis, A. partykit: A modular toolkit for recursive partytioning in R. J. Mach. Learn. Res. 16, 3905–3909 (2015).

Borkovec, M. & Madin, N. ggparty:“ggplot” Visualizations for the “partykit” Package. https://cran.r-project.org/web/packages/ggparty/index.html (2019).

Rothman-Ostrow, P., Gilbert, W. & Rushton, J. Tropical livestock units: re-evaluating a methodology. Front. Vet. Sci. 7, 556788 (2020).

Erb, K.-H. et al. A comprehensive global 5 min resolution land-use data set for the year 2000 consistent with national census data. J. Land Use Sci. 2, 191–224 (2007).

Ramankutty, N., Evan, A. T., Monfreda, C. & Foley, J. A. Farming the planet: 1. Geographic distribution of global agricultural lands in the year 2000. Glob. Biogeochem. Cycles https://doi.org/10.1029/2007GB002952 (2008).

Xiao, L. et al. Global depth distribution of belowground net primary productivity and its drivers. Glob. Ecol. Biogeogr. 32, 1435–1451 (2023).

Zhang, Y. Integration Dataset of Tibet Plateau Boundary. https://data.casearth.cn/dataset/5feae826819aec33049b7ca9 (2019).

Hou, X. 1:1 Million Vegetation Map of China. https://data.tpdc.ac.cn/en/data/eac4f2cf-d527-4140-a35d-79992957f043/ (2024).

Acknowledgements

This study was supported by the National Key Research and Development Project of China (2024YFF0809104), the National Natural Science Foundation of China (42425106) and the Second Tibetan Plateau Scientific Expedition and Research (STEP) program (2024QZKK0301). We also acknowledge the support of the Kathmandu Center for Research and Education, Chinese Academy of Sciences—Tribhuvan University.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

T.W. conceptualized the paper. S.R. performed data analysis and produced figures. X.J. presented a framework for mapping thermokarst landscapes. L.W. and J.W. generated the livestock distribution datasets. Y.C. and J.D. contributed field-sampled soil carbon data. S.R. and T.W. drafted the paper; all authors contributed to the interpretation of the results and to the text.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Peer review

Peer review information

Nature Communications thanks Gang Li and Xiangping Tan for their contribution to the peer review of this work. A peer review file is available.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Source data

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Ren, S., Wang, T., Ji, X. et al. Grazing reverses climate-induced soil carbon gains on the Tibetan Plateau. Nat Commun 16, 6978 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-025-62332-6

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-025-62332-6

This article is cited by

-

Herbivore Dung inputs mainly drive copiotrophic bacterial contributions to soil nutrient pool turnover in alpine grasslands

Biology and Fertility of Soils (2025)