Abstract

Lightweight, high-performance electromagnetic shielding materials rely on the precise design of electromagnetic response structures. Conventional shielding materials often involve complex fabrication of conjugated composites or graphitization of organic materials, facing challenges in balancing their performance and processability. As such, seeking and designing intrinsically conjugated materials with superior processability is crucial. In this work, we have innovatively engineered those bioinspired polymers with highly ordered microstructures, using a 5, 6-dihydroxyindole ring tetramer framework to construct highly ordered melanin-like nanofibers by tuning π–π stacking. The resulting melanin-like aerogels represent surprising microwave absorption performance, a maximum reflection loss of −68.87 dB, and an effective absorption bandwidth of 5.25 GHz. In the X-band, the aerogel reached the specific EMI shielding efficiency of 47909.9 dB cm2/g. This work represents the first successful extension of melanin-like polymers into the microwave spectrum, demonstrating great potential in the electromagnetic field.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

With the increasingly stringent requirements of aerospace and military equipment for combat speed and concealment in complex environments, electromagnetic shielding materials are undergoing iterative upgrades, aiming for higher performance and lighter weight1,2. Conventional metal materials and their composites usually suffer from unsatisfactory density, leading to the increasing attentions on highly conjugated inorganic materials such as carbon nanotubes and graphene, graphene, etc., which could be compounded with polymers or directly processed into material forms via customized methods. However, due to their poor compatibility, there is an inevitable dilemma that conjugate structures make it difficult to construct effective adaptive networks3,4. An Alternative strategy is to graphitize natural or organic materials to obtain a high degree of conjugated structures. However, the inherent defects would be present in the graphitized products, which are difficult to regulate accurately. The resulting electromagnetic shielding materials often exhibited limited performance5. Therefore, the key to breaking through the lightweight and high-performance electromagnetic shielding materials is to develop a class of intrinsic conjugated organic materials with well-regulated structures and functions2.

Melanin has been regarded as a class of emerging, promising energy-dissipating biomacromolecules in nature, which could efficiently absorb and transform a broad spectrum of energy due to its characteristic and chaotic assembled structures6,7,8,9. Melanin and melanin-like polymers offer abundant chemical versatility and significant potential for structural regulation, making them easily combinable with various materials. Considerable research has been focused on the structural and interaction regulation of melanin-like polymers, which have shown good responses to a wide range of electromagnetic waves, from ionizing radiation to near-infrared (NIR) light, offering radiation protection, visible light absorption, and photothermal conversion10,11,12,13,14,15. However, reports on melanin-like materials exhibiting effective absorption in the microwave band are quite lacking, since their disordered structures cannot support long-range electron transfer paths to respond to long-wavelength energy8. Thus, if we could construct melanin-like materials with highly ordered microstructure through appropriate supramolecular engineering strategies, it is expected to extend the energy dissipation range of melanin-inspired polymers and break the performance limitations in lightweight, high-performance materials for electromagnetic shielding.

Theoretically, the formation process of melanin and melanin-like polymers involves both chemical processes(oxidation, isomerization, rearrangement into 5,6-dihydroxyindole (DHI) tetramers, and coupling reactions between intermediates) and physical assembly through intermolecular interactions, including π–π stacking and hydrogen bonding. Traditional methods typically result in disordered melanin-like materials due to complicated macromolecular structures and cross-linked hydrogen bond networks formed by phenolic hydroxyl groups, which severely inhibit the establishment of long-range ordered structures. Therefore, we speculated that highly ordered melanin structures can be achieved by enhancing the π–π interactions between DHI tetramers and minimizing random chemical reactions and hydrogen bond crosslinking within the macromolecular networks. The resulting highly ordered melanin-like polymers might enable long-range electron conduction and improve electromagnetic response capabilities.

One possible way to realize this goal is to increase the proportion of cyclized indole and reduce the disordered crosslinking caused by hydrogen bonding. To accomplish this, we strived to use indole analogs as active species to induce the polymerization process, resulting in improved π–π stacking of the DHI tetramers. This approach could achieve the successful formation of highly ordered melanin-like nanofibers. These nanofibers were then processed into ultra-light, high-performance carbon aerogels through typical freeze-drying and pyrolysis treatments. Surprisingly, the resulting melanin-inspired aerogels exhibited exceptional electromagnetic interference (EMI) shielding and microwave absorption (MA) properties, with a maximum reflection loss (RL) of −68.87 dB and an effective absorption bandwidth (EAB) of 5.25 GHz in the 2–18 GHz range. In the X-band, with a density of 3.11 mg/cm3 and a thickness of 2 mm, the aerogel achieved an impressive absolute EMI shielding effectiveness (SSE/t), defined as the shielding effectiveness (SE) value divided by the surface density, reaching 47,909.9 dB·cm2/g. Additionally, radar cross-section (RCS) simulations were performed, confirming the potential application of these aerogels as intelligent electromagnetic shielding materials for stealth technology. This work demonstrates the successful construction of melanin-like polymers with highly ordered microstructures through the rational regulation of interaction forces, offering a different way for optimizing the properties of a broad range of bioinspired materials.

Results

Fabrication and characterization of melanin-like nanofibers

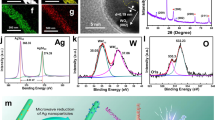

Conventional melanin-like polymers, such as polydopamine (PDA), typically form isotropic nanoparticles due to their disordered structures. In this work, we introduced indole units with different hydroxyl groups into the conventional melanin polymerization process, aiming to reduce the influence of hydrogen bonding. A one-pot copolymerization of different indole analogs and dopamine monomer in a mixture solution of water and alcohol at room temperature in the presence of ammonium hydroxide was facilely performed, as the typical experimental condition for PDA nanoparticles preparation (Fig. 1A, Note S1, and Figs. S1–S3). We discovered that the PDAs formed with indole or 5,6-dihydroxy indole maintained traditional black nanoparticles, while those synthesized with 5-hydroxyindole exhibited distinct yellow nanofibers prepared under similar conditions (Figs. 1B, C and S4). Ultraviolet-visible spectra further confirmed the presence of characteristic absorption between 300 nm and 450 nm (Fig. S5), while there is almost no absorption in the rest of the visible region, suggesting that the optical properties of PDA nanofibers are quite different from conventional PDA nanoparticles. Furthermore, we confirmed the existence of the highly ordered structures by transmission electron microscopy (TEM), which revealed a layered structure with an interlayer spacing of approximately 3.4 Å, consistent with classical π–π stacking (Fig. 1D).

A Preparation and application diagram of traditional PDA nanoparticles and PDA nanofibers. B Optical photograph of PDA nanofibers aerogel (C) SEM image of PDA nanofibers. D HRTEM image of PDA nanofibers. The red line shows the π–π stacking spacing. E XPS survey spectra and element proportion of PDA nanofibers. F UPLC-MS spectra of PDA nanofibers solution. G Graphical result of molecular stacking at time t (t = 0, 20, 50, and 100 ns) in GROMACS and specific characteristic structures and corresponding interlayer spacing. H XRD patterns of PDA nanofibers. I Raman spectra of PDA nanofibers.

We then carefully investigated their chemical structures in detail. Firstly, we used X-ray photoelectron spectroscopy (XPS) to determine the element proportions, which revealed that the molar ratio of hydroxyl indole was 17.8%, consistent with the results from elemental analysis (EA) (Figs. 1E and S6). Next, we performed the disassembly experiments in various solvents (Fig. S7). It was found that the nanofibers were completely disassembled in methanol and acetonitrile, indicating that their assembly was driven by supramolecular forces. The dissolution likely occurred due to the disruption of hydrogen bonds, caused by solvent interactions and competition. Electrospray ionization mass spectrometry (ESI-MS) analysis of the disassembled PDA nanofibers in methanol solution revealed prominent peaks that closely matched the coupled molecules of DHI and 5-hydroxyindole (M1), the dimer of 5-hydroxyindole (M2), and the ring tetramer of DHI (M3) (Figs. S8 and S9). Additionally, the ring tetramer of DHI was successfully isolated using ultraperformance liquid chromatography-tandem mass spectrometry (UPLC-MS) (Fig. 1H). Based on the elemental analysis, we calculated the M1 to M3 ratio as 11:10, consistent with the N and O element ratios. To better understand the self-assembly process, we used GROMACS16,17 simulations to model the interactions between these two molecular species at the same ratio, under identical solvent and temperature conditions (Fig. 1G). The whole system is arranged and stacked autonomously, driven by its interaction force. Over a simulation time of 100 ns, the molecules exhibited a general tendency to form fibrous assemblies. Through the analysis of the still frames at different times, a series of frequent structures are found by performing a dynamic simulation of the entire system, which were preserved in the final stable structure. Key structural analysis revealed that the tetramer (M3) favored axial packing, likely contributing to the formation of nanofibers (structure 1). Additionally, the interplay of hydrogen bonding, cation-π interactions, and hydrophilic-hydrophobic forces, combined with the planar deflection angles of M1 and M3, led to a deflected, side-by-side arrangement of the fibers. M1 co-stacked via hydrogen bonding and π–π interactions, producing a variety of typical arrangements and corresponding interlayer spacings (structures 2–4)18. Based on these results, we proposed that the formation of PDA nanofibers follows a specific pathway: in a base-catalyzed environment, dopamine undergoes oxidation, cyclization, and rearrangement to generate DHI. During this process, quinone free radicals are formed, which initiate both self-polymerization and copolymerization with indole. Since 5-hydroxyindole has only a single hydroxyl group, it cannot support multidirectional hydrogen bond cross-linking. This limitation facilitates the formation of M3 with outward-facing hydrogen bonds18,19. Additionally, M3 exhibits a strong π–π conjugation tendency, with the delocalized π-electron cloud over the indole ring promoting directional axial packing. This axial packing provides a potential mechanism for π-electron transport within the material19. As the degree of crosslinking varies due to hydrogen bonding between the tetramer and other conjugated structures, nanofibers with different length-to-diameter ratios are formed.

This hypothesis was further supported by X-ray diffraction (XRD) analysis (Fig. 1H), which revealed a highly ordered stacking structure that differs significantly from the amorphous peaks typically observed in conventional PDA nanoparticles. The peaks between 20° and 25° correspond to the π–π stacking region, while the smaller angle peaks likely result from multistage diffraction or other assembled structures19,20. These findings closely align with the structural predictions obtained from GROMACS simulations. An integral analysis of the XRD data indicated that the amorphous envelope peak region accounts for only 2.1%, further confirming the high degree of ordered microstructures within the PDA nanofibers. Raman spectroscopy (Fig. 1I) provided additional evidence for the ordered structure. The PDA nanofibers were found to exhibit a sharp and narrow G-peak at 1580 cm−1, in stark contrast to the broader, multiple peaks characteristic of conventional PDA nanoparticles. This sharp G-peak suggested that the molecules within the nanofibers primarily undergo in-plane stretching vibrations, with boundary vibrations suppressed due to their fixed, lattice-like arrangement. This result strongly correlated with the vibration characteristics of the DHI ring tetramer. The narrow peak width further indicates a high degree of uniformity among the molecular units participating in in-plane vibrations within the PDA nanofibers21. Upon magnifying the Raman spectrum, a very small signal in the D-peak region was detected. Although this peak was visually masked, its area accounts for only 1.61% of the G-peak area. Further, we compare it with the computed Raman spectra obtained by Gaussian optimized Structure 1, and obtain a high consistency (Figs. S10 and S11). This result was consistent with the XRD findings, reaffirming the highly ordered structures within the PDA nanofibers.

Fabrication and characterization of PDA carbon aerogels

The as-synthesized PDA nanofiber aerogels were carbonized in a tubular furnace under a flowing nitrogen atmosphere at various temperatures (600 °C, 700 °C, 800 °C, and 900 °C) for 2 h, with a heating rate of 5 °C/min (Fig. 2A). The resulting carbon aerogel samples were designated as NFAG-i (i = NFAG-600, NFAG-700, NFAG-800, and NFAG-900), respectively. SEM imaging in Fig. 2B–D (NFAG-700, 800, 900) confirmed that the carbonized aerogels still retained their long fibrous morphologies, indicating structural stability during carbonization. XPS survey scans shown in Fig. 2C revealed the removal of N and O elements, leading to the formation of oxygen vacancies and electron-hole pairs within the NFAG samples. These defects act as polarization centers, significantly enhancing the dielectric properties of the material (Fig. 2E). Figure 2F shows the Raman spectra of NFAGs, where the D band (centered at ~1350 cm−1) and G band (centered at ~1590 cm−1) intensities were analyzed. The D/G ratio (ID/IG), indicative of the relative proportions of disordered and graphitic carbon, showed a gradual increase in the graphite phase with rising temperatures, reaching an ID/IG value of 0.8221 for NFAG-900, which is favorable for electron transport. FTIR spectra (Fig. 2G) further corroborated these findings, showing a significant reduction or complete disappearance of organic C=O and C–N peaks, consistent with the XPS results. Notably, π–π stacking in NFAG not only facilitated π-conjugated electron transportation but also contributed to the formation of micropores during heat treatment, since its higher bond length made it more susceptible to such structural changes compared to typical covalent bonds. N2 adsorption-desorption characterization was used to evaluate the specific surface area (SSA) and pore size distribution of the NFAG samples. The high air-phase volume fraction provided a potential impedance-matching advantage for NFAG in dielectric applications. All samples (Fig. 2H) exhibited typical type IV isotherms with H1 hysteresis loops, indicative of capillary condensation of N2. NFAG-900 demonstrated a good surface area of 885.65 m2/g, ~four times higher than that of carbonized PDA nanoparticles reported previously13. The predominant micropores (<2 nm) play a crucial role in facilitating ion transport, improving electrical applications, optimizing impedance matching, and enabling the construction of abundant gas-solid heterostructures.

MA of NFAGs

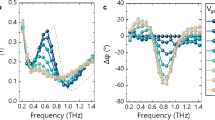

Figure 3A, B illustrates the primary loss mechanisms in NFAGs. The extensive SSA and micropores contributed significantly to the interfacial loss in NFAGs, while the multistage core-skin structure of the fibers generated additional heterogeneous interfacial systems. Debye relaxation polarization in NFAGs could be attributed to numerous defects and residual groups, including oxygen vacancies and electron-hole pairs induced by heat treatment, which facilitated electron accumulation, transfer, and dipole formation. Furthermore, the good electrical conductivity of the PDA nanofibers, owing to their ordered structure, played a significant role in ohmic loss. This effect was further amplified by the large aspect ratio and three-dimensional interconnected conductive network formed during heat treatment and sintering. Next, the MA capacity of NFAGs (NFAG-600, NFAG-700, NFAG-800, and NFAG-900) was evaluated, respectively. Generally, an RL value below −10 dB is considered the threshold for effective absorption, indicating that more than 90% of incident microwaves are absorbed1. The corresponding microwave frequency range is referred to as the EAB, a critical parameter for assessing the broadband performance of microwave-absorbing (MA) materials. The RL values of NFAGs were calculated using Eqs. 4 and 5, with the results presented in Figs. 3C, D and S15. The data revealed that the absorption efficiency of NFAGs improved with increasing pyrolysis temperature. Among the samples, NFAG-900 demonstrated satisfactory performance, achieving a minimum reflection loss (RLmin) of −68.87 dB at 10.62 GHz and an EAB of 5.25 GHz at a thickness of 2.5 mm. These results surpassed most of the recently reported microwave-absorbing materials (Fig. 3E). To further clarify the absorbing mechanism, we discussed the electromagnetic parameters of all samples. The real part (ɛ′) and imaginary part (ɛ′′) of complex permittivity represent the ability to store and dissipate electrical energy, respectively. As shown in Fig. S16, the electromagnetic parameters of NFAG-900 were characterized. Firstly, it was observed that the ɛ′ values of all samples tend to decrease with increasing frequency. This behavior could be attributed to polarization hysteresis at higher frequencies and typical frequency dispersion. Additionally, both ε‘ and ε“ increased with rising pyrolysis temperatures, attributed to the higher graphite phase ratio, enhanced sintering degree, and the formation of electron-hole pairs, interfaces, and micropores. These factors collectively contributed to a denser electron transport network, enhancing the material’s dielectric loss2. Impedance matching (Z = |Zin/Z0|) is employed to assess the alignment between the material and free space, with optimal matching achieved when the Zin/Z0 ratio approaches 1. As shown in Fig. 3F, NFAG-900 displayed befitting impedance matching over a wide frequency range, where the position of the maximum absorption corresponded to the optimal impedance-matching position. This facilitated the penetration of significant electromagnetic waves into the material22. Furthermore, when comparing the attenuation constant, NFAG-900 exhibited high values, confirming its effective ability to dissipate electromagnetic waves (Fig. S17). According to the λ/4 theory, NFAGs with different thicknesses correspondingly exhibited different adaptive frequency bands. As the thickness increases, the adaptive frequency bands showed a trend of moving towards low frequencies(Fig. 3G)22. According to Debye’s theory, the presence of Cole–Cole semicircles in the ε′−ε′′ plots suggested Debye relaxation processes. As shown in Fig. 3G, the curve displayed two distinct sections with varying characteristics. In the low-frequency region, the Cole–Cole plot exhibited an approximately linear relationship, primarily attributed to dielectric loss due to interface polarization, while in the high-frequency region, the classical Cole–Cole semicircle revealed significant Debye relaxation polarization4. This phenomenon is understandable, as interface polarization occurs at heterogeneous interfaces and requires charge accumulation or complete dipole migration, which necessitates a longer response time. In contrast, Debye relaxation polarization involves directional dipole polarization of lower intensity. Upon removal of the external field relaxation, the dipole loses its orientation under thermal motion, leading to a significantly shorter response time compared to interface polarization. Applying a nonlinear least squares model allowed for the separate determination of contributions from polarization losses and conduction losses. As shown in Fig. S18, polarization loss made a major contribution to dielectric loss23.

A Schematic illustration of the MA process. B MA mechanism of NAFGs. C RL value of NFAG-900. D Three-dimensional representations and two-dimensional projection images of the RL value of NFAG-900. E Comparison of RL and EAB of typical reported carbon aerogels33,34,35,36,37,38,39,40,41,42,43,44,45. F Impedance-matching of NFAG-900 at different thicknesses. G EAB of NFAG-900 with different thicknesses. H Cole-Cole plot of NFAG-900.

Electromagnetic shielding performances of NFAGs

Figure 4A illustrates the mechanism for the exceptionally high EMI shielding performance of NFAGs, based on transmission line theory. First, impedance matching occurred at the interface of the NFAGs. A small portion of the electromagnetic wave was reflected, while a large amount penetrated into the material. Once inside, the electromagnetic waves were trapped within the NFAG structure, where they were attenuated by losses in conduction and polarization between the cross-linked carbon nanofiber networks. This process converted electromagnetic energy into heat. Additionally, the dense skin structure of the nanofibers allowed repeated reflections of the remaining electromagnetic waves, ensuring that the energy was completely absorbed, contributing to shielding efficiency24. Notably, the core-shell structure of the self-assembled nanofibers further created rich heterogeneous interfaces, which were conducive to interface polarization and loss, further enhancing the material’s shielding capability25,26. To further expand its application scenario of NFAGs, we investigated their shielding performance in the common X-band. As shown in Fig. 4C, NFAGs exhibited high electrical conductivity, which could be attributed to the good electron transport capacity of the highly ordered microstructures. Interestingly, the conductivity of NFAG-900 reached 103.47 S/m, several orders of magnitude higher than the graphitized PDA nanoparticles, which typically exhibit conductivities in the range of 10−4–10−6 S m−1 27. Correspondingly, the shielding efficiency of NFAGs increased with the heat treatment temperature. Electromagnetic shielding generally involves three primary mechanisms: reflection (R), absorption (A), and transmission (T)2. We further calculated the contribution of each shielding through theoretical calculations. The shielding performance of NFAGs with π–π stacking framework is primarily dominated by absorption, in contrast to traditional conjugated materials, which often suffer from poor impedance matching. The essential difference with traditional materials lies in the difference in conjugation structure. The traditional covalent conjugation has a high degree of free delocalization of π electrons, and the transmission process has almost no loss, while the π–π electron conduction between the aromatic ring layers needs to pass through a complex polarization field and path, resulting in loss28. The higher degree of graphitization and the increased number of polarization centers, resulting from higher heat treatment temperatures, were crucial factors contributing to the enhanced absorption. In addition, NFAGs, due to their simple preparation method, offer the flexibility to adjust the final material density by varying the concentration of the lyophilized solution, as practically needed. Specifically, a 2 mm thick NFAG-900 sample, with a density of 21.38 mg/cm3, achieved an electromagnetic shielding efficiency (SE) of 65 dB. To evaluate the comprehensive EMI shielding properties, we calculated the specific SSE/t, which accounts for the material’s absolute SE considering its thickness (t) and density (ρ), as given by the following equation:

A Schematic illustration of the EMI mechanism of the skin-core structure. B Comparison of SSE/t of typical reported carbon aerogels as a function of density24,46,47,48,49,50,51,52,53,54,55,56,57,58,59,60,61. C Conductivity, D EMI shielding efficiency, and E EMI shielding parameter of NFAGs at different heat treatment temperatures. F Conductivity, G EMI shielding efficiency, H EMI shielding parameter of NFAGs in different concentrations. I SEM and TEM images of the multi-scale skin core structure.

Excitingly, the specific shielding effectiveness (SSE/t) of NFAGs at a density of 3.11 mg/cm3 and a thickness of 2 mm reached an impressive 47,909.9 dB·cm2/g (Fig. 4B). Analysis of the parameters revealed that the reflection (R) increased with density, which can be attributed to the formation of a higher-density fiber network and a denser outer cortex. SEM and TEM images revealed the multiscale skin-core structure of the NFAGs. Notably, NFAG-900 exhibited a dense shell formed by the curling and sintering of the outermost fibers during heat treatment, which led to fiber entanglement at the interface and a tightly packed shell structure. Furthermore, high-resolution observations of the graphitized nanofibers showed enhanced π–π stacking near the surface, likely due to the extended period available for surface refinement during the later stages of the reaction, after the chemical process had terminated. The skin-core structure introduced additional heterogeneous interfaces, which enhanced the ability of NFAGs to dissipate electromagnetic waves. This phenomenon was consistent with previous reports on the role of heterogeneous interfaces in improving wave dissipation24,29.

Through the pre-regulation of melanin-based organic structures, we have successfully developed ultra-lightweight and highly efficient electromagnetic shielding and microwave-absorbing materials. Note that nature offers numerous examples where alterations in the aggregation state and interaction forces of organic materials lead to varied energy responses. For instance, non-covalently arranged porphyrin derivatives serve as the primary chromophores in the light-harvesting systems of plants and algae, enabling them to capture light of different wavelengths by modulating their aggregation state. Inspired by this, our work highlights the potential of pre-regulating the structure of organic materials or synthetic molecules to achieve enhanced energy-responsive architectures while preserving strong processability. At the same time, this work also showed that π–π stacking might be an adaptive characteristic structure of electromagnetic energy dissipation, and it had better impedance-matching and microstructure than the traditional conjugate structure, which was expected to greatly expand the material candidate pool in the field of energy dissipation applications.

RCS simulation

To verify the practical application potential, FEKO software was employed to simulate the Radar Cross Section (RCS) of the composite aerogel at different temperatures, using the classic stealth fighter F-35 as the model (Fig. 5A, B)30,31. NFAG-900 was applied as a 2.5 mm-thick coating on the F-35’s surface, and its performance was compared with that of an ideal coating of the same thickness. The simulation was conducted using monostatic RCS and plane wave propagation, with incident angles of 10°, 0°, and −10° to cover different flight attitudes, and a frequency of 10.46 GHz (the optimal absorption frequency)30,31,32. The results showed that NFAG-900 exhibited adequate radar stealth capabilities, with ΔRCS values consistently below -20 dB. Specifically, the average ΔRCS was −35.88 dB at 0°, −36.56 dB at 10°, and −35.45 dB at −10°. At an incident angle of 10°, the F-35 demonstrated the best RCS value of −50.47 dB at 153°, indicating that NFAG-900 provides satisfactory radar stealth performance across a range of angles. These findings suggested that NFAGs have promising potential as intelligent microwave-absorbing materials, adaptable for real-time use in diverse applications, particularly in the defense and aerospace sectors.

Discussion

In summary, distinct from traditional strategies that focus on the engineering of conjugated precursors or the pyrolysis of natural materials, we have proposed the structural pre-regulation strategy to construct melanin-like polymers with highly ordered microstructures to achieve optimal electromagnetic matching. Indole analogs were employed to regulate the interaction forces during the melanin polymerization process, successfully constructing ordered PDA nanofibers with stacked DHI ring tetramers. Through typical freeze-drying and heat treatment, we have successfully fabricated ultra-light, conductive, and multi-scale core-skin structured NFAGs, which are well-suited for MA and shielding applications. This multi-scale core-skin ordered structure significantly enhanced the electromagnetic wave propagation path and created abundant heterojunctions, thereby improving dielectric loss. As a result, NFAGs showed good MA performance, with a maximum RL of −68.87 dB and EAB of 5.25 GHz. In the X-band, with a density of 3.11 mg/cm3 and a thickness of 2 mm, its SSE/t value reaches 47909.9 dB cm2/g. This strategy is expected to extend to the design and application of a broader range of bio-inspired polymers in energy response dissipation, thereby driving material innovation in the electromagnetic and stealth fields.

Methods

Materials

Dopamine hydrochloride (98%), 5-hydroxyindole (98%), and ammonia aqueous solution (25–28 wt%) were all purchased from Titan Scientific Co. Ltd (Shanghai, China). Ethanol (SafeDry), methyl alcohol (Safe Dry), ethyl acetate (SafeDry), acetonitrile (SafeDry), NaOH (99%), HCl (37%), THF (Safe Dry), DMSO (SafeDry), and DMF (SafeDry) were acquired from Kelong Chemical Reagent Co., Ltd. (Chengdu, China). All chemical reagents were freshly used without any further purification in the research.

Synthesis of PDA nanofibers

A total of 450 mg dopamine (DA) and 50 mg 5-hydroxyindole were dispersed in a mixed aqueous alcohol solution (90 mL H2O and 40 mL ethanol) using ultrasonic treatment. Ammonia aqueous solution (NH₄OH, 3 mL, 28–30%) was then added to the above solution. The color of the mixture immediately changed to light brown, gradually transitioning to dark green. After 24 h of reaction, the yellow PDA nanofibers were obtained by centrifugation and washed three times with deionized water.

Fabrication of PDA carbon aerogels

The PDA aerogel was prepared by freeze-drying the dispersion, which was evenly dispersed in water at a specific concentration. The as-synthesized PDA nanofiber aerogel was carbonized at a specific temperature (600 °C, 700 °C, 800 °C, 900 °C) for 2 h at a heating rate of 5 °C min−1 in a flow nitrogen atmosphere to prepare PDA nanofiber carbon aerogel samples (NFAG-600, NFAG-700, NFAG-800, and NFAG-900).

Characterization

The surface morphologies of the series of materials mentioned were acquired on a scanning electron microscope (SEM) of FEI Quanta 250. The transmission electron microscope (TEM) images and the EELS mapping analysis were acquired on a Talos F200i (Thermo Scientific, Czech). The ESI-MS spectrum of the disassembly solution of PDA nanofibers was applied on Applied Biosystems API 2000 with positive anion mode electrospray ionization with a 10 µL min−1 flow rate. The UPLC-MS was performed by Agilent 1290 UPLC and Agilent QTOF 6550 with positive anion mode electrospray ionization with 0.3 min−1 flow rate; (Chromatographic column: Waters BEH C18 2.1 × 100 mm 1.7 μm; 20% mobile phase A: 0.1% aqueous formic acid; 80% mobile phase B: methanol). Raman spectra were obtained with a Raman spectrometer (HORIBA HR Evolution) using an Ar ion laser (532 nm) as the emission source to characterize the degree of graphitization. UV-vis spectroscopy was performed by a PerkinElmer Lambda 650 UV–vis spectrophotometer. Fourier transform infrared spectra (FTIR, Thermo Fisher Nicolet iS50), X-ray photoelectron spectra (XPS, Thermo Fisher Thermo Scientific K-Alpha+), and XRD (Rigaku Ultima IV) were employed to analyze the chemical structure of samples. The pore characteristics and SSAs of the samples were evaluated using Micromeritics ASAP 2020 at liquid Ar temperature. EIS measurements were conducted on a CHI760E electrochemical workstation. Corresponding electrical conductivity (σ) was examined by an RTS-9 four-point probe tester at a temperature of 25 °C according to the modified ASTM F 390-98.

Electromagnetic parameter characterization

Electromagnetic parameters were obtained by an Agilent E5071C vector network analyzer in the frequency range of 2–12 GHz based on a coaxial method. The measured samples were prepared by adding the absorbents (10–30 wt%) into molten paraffin, uniformly mixing them, followed by molding into a coaxial ring with an outer diameter of 7.0 mm and an inner diameter of 3.0 mm. In order to further analyze the shielding capability in the X band (8.2–12.4 GHz), the Electromagnetic parameters were obtained on the basis of a waveguide method. The EMI performance is calculated according to the scattering parameters, including SE total (SET), SE reflection (SER), and SE absorption (SEA), the coefficients of absorption (A), transmission (T), and reflection (R).

Molecular simulation

The molecular ratio was calculated as DA tetramer (structure 1): Bimolecular conjugate (structure 1) = 11:10 according to the proportion of elements obtained by EA, which was used to simulate molecular stacking in GROMACS. For random insertion of molecules, the GROMACS insert-molecules tool was used. The amber14sb force field parameters were used for both molecules, and the system was solvated using the TIP3P model. The system, containing a total of 1800 water molecules, 800 molecules of ethanol, which is consistent with the reaction environment, 11 molecules of structure 1, and 1 molecule of structure 2, was used for the simulation. The steepest descent method was used to minimize the energy of the system, and the NPT ensemble was performed with 100 ps. The production of the simulation was run for 100 ns using a 2-fs time step under standard atmospheric pressure. The V-rescale method was used for temperature coupling, and the Parrinello-Rahman method was used for pressure coupling. The Particle Mesh Ewald (PME) method was used for long-range electrostatic interactions. A 14 Å cut-off was employed for van der Waals force (VdW) and short-range coulombic interaction. MD calculations were performed with the GROMACS molecular dynamics simulation package. Pymol was used for all molecular visualizations. The Antechamber program was used to generate complex force field parameters, and the team (Amber 18.0 Module) was used to generate the molecular topology. The HF/6-31 G* method and basis set were used to calculate the electrostatic potential (ESP), and then the result was employed to calculate the restricted ESP(RESP)2 charge. During the running time, the molecules within the system would spontaneously move and arrange based on their interaction forces. The applied molecules were in a constantly dynamic changing state to achieve an energy-stable state.

Simulation details and methodology of electromagnetic parameters

The RL values were calculated based on the transmission line theory:

where εr and μr are the complex permittivity (εr = ε′ − jε′′) and permeability (μr = μ′ − jμ′′), respectively, f is the frequency of the microwave, c is the velocity of light, d is the thickness, and Zin is the normalized input impedance of the sample.

Additionally, the EMI SE of shielding materials can be defined as the logarithmic ratio of the incident power (PI) to transmitted power (PT) of an EM wave, and can be expressed in the following equation:

Where \({{SE}}_{T}\), \({{SE}}_{R}\), and \({{SE}}_{A}\) represent the overall SE, reflection, and absorption effectiveness (dB).

Where the SET > 15 dB, the SEM is generally neglected, and the SET is determined by the sum of SER and SEA:

Where A, R, and T are the reflection coefficient, absorption coefficient, and transmission coefficient, respectively.

RCS simulations

The RCS value simulations were performed by FEKO 2017 software, using F35 as models. The scanning simulations were performed using the adaptive scanning technology AFS (Function Method of MoM Green-SGF). The simulated model was made up of an upper absorbing layer (NFAG-900, 2.5 mm) and a bottom perfect electric conductor layer (PEC, 2.5 mm). The measured permittivity and permeability of NFAG-900 were used as EM parameters for input materials. The scattering directions were set as ≈0–360° for θ, and 0°, −10°, and 10° for aircraft attitude inclination ϕ. The monitor frequency is set as 10.46 GHz, which shows the maximum ΔRL values for NFAG-900.

Data availability

The authors declare that all data supporting the results in this study are present in the paper, and the Source data are provided with the paper. All data are available from the corresponding author upon request. Source data are provided with this paper.

References

Qin, M., Zhang, L. & Wu, H. Dielectric loss mechanism in electromagnetic wave absorbing materials. Adv. Sci. 9, e2105553 (2022).

Lv, H. L., Yang, Z. H., Pan, H. G. & Wu, R. B. Electromagnetic absorption materials: current progress and new frontiers. Prog. Mater. Sci. 127, 52–64 (2022).

Green, M. & Chen, X. B. Recent progress of nanomaterials for microwave absorption. J. Materiomics 5, 503–541 (2019).

Wu, Z. C. et al. Dimensional design and core-shell engineering of nanomaterials for electromagnetic wave absorption. Adv. Mater. 34, 202107538 (2022).

Shi, Y. et al. Advanced functional electromagnetic shielding materials: a review based on micro-nano structure interface control of biomass cell walls. Nanomicro Lett. 17, 3 (2025).

Hu, J. F. et al. Polydopamine free radical scavengers. Biomater. Sci. 8, 4940–4950 (2020).

Jin, Z. K. et al. Flexible polydopamine bioelectronics. Adv. Funct. Mater. 31, 202103391 (2021).

Yang, P. et al. Stimuli-responsive polydopamine-based smart materials. Chem. Soc. Rev. 50, 8319–8343 (2021).

Lee, H. A., Park, E. & Lee, H. Polydopamine and its derivative surface chemistry in material science: a focused review for studies at KAIST. Adv. Mater. 32, 201907505 (2020).

Zou, Y. et al. Regulating the absorption spectrum of polydopamine. Sci. Adv. 6, abb4696 (2020).

Yang, Z. et al. A Bioinspired strategy toward UV absorption enhancement of melanin-like polymers for sun protection. Ccs Chem. 5, 2389–2402 (2023).

Bai, W. J. et al. Boosting the optical absorption of melanin-like polymers. Macromolecules 55, 3493–3501 (2022).

Yang, L. et al. Emergence of melanin-inspired supercapacitors. Nano Today 37, 101075 (2021).

Wang, X. H. et al. Quaternary ammonium assisted synthesis of melanin-like poly(l-DOPA) nanoparticles with a boosted photothermal effect. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 16, 22493–22503 (2024).

Yang, Z. et al. Structural disruption of melanin-like polymers with boosted UV protection. Sci. China Chem. 67, 1653–1663 (2024).

Ping, Y. Q. et al. Structural basis for the tethered peptide activation of adhesion GPCRs. Nature 604, 763–770 (2022).

Hess, B., Kutzner, C., van der Spoel, D. & Lindahl, E. GROMACS 4: algorithms for highly efficient, load-balanced, and scalable molecular simulation. J. Chem. Theory Comput. 4, 435–447 (2008).

Liebscher, J. et al. Structure of polydopamine: A never-ending story?. Langmuir 29, 10539–10548 (2013).

Yu, X., Fan, H. L., Wang, L. & Jin, Z. X. Formation of polydopamine nanofibers with the aid of folic acid. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. Engl. 53, 12600–12604 (2014).

Ma, J. et al. Enhanced adsorptive removal of methyl orange and methylene blue from aqueous solution by alkali-activated multiwalled carbon nanotubes. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 4, 5749–5760 (2012).

Zhu, J. Y. et al. Near-room-temperature water-mediated densification of bulk van der Waals materials from their nanosheets. Nat. Mater. 23, 604–611 (2024).

Li, Y. et al. Controlled preparation of lightweight, resilient helical carbon fibers for high-performance microwave absorption and oil-water separation. Carbon 233, 119923 (2025).

Y. Li et al. A tough temperature-responsive composite for switchable microwave absorption. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces. 17, 27178–27187 (2025).

Yao, J. R. et al. Ultrathin self-assembly MXene@flake carbonyl iron composites with efficient microwave absorption at elevated temperatures. Adv. Electron. Mater. 7, 202100587 (2021).

Li, X., Wu, Z. C., You, W. B., Yang, L. T. & Che, R. C. Self-assembly MXene-rGO/CoNi film with massive continuous heterointerfaces and enhanced magnetic coupling for superior microwave absorber. Nanomicro Lett. 14, 73 (2022).

Wu, Z. C. et al. Electrochemical switching of electromagnetism by hierarchical disorder tailored atomic scale polarization. Adv. Mater. 36, 202410466 (2024).

Osak, W., Tkacz, K., Czternastek, H. & Slawinski, J. IV Characteristics and electrical-conductivity of synthetic melanin. Biopolymers 28, 1885–1890 (1989).

Liu, A. et al. Asymmetric structural MXene/PBO aerogels for high-performance electromagnetic interference shielding with ultra-low reflection. Adv. Mater. 37, 202414085 (2025).

Wu, N. N. et al. Review on the electromagnetic interference shielding properties of carbon based materials and their novel composites: recent progress, challenges and prospects. Carbon 176, 88–105 (2021).

Uluisik, C., Çakir, G., Çakir, M. & Sevgi, L. Radar cross section (RCS) modeling and simulation, part 1:: a tutorial review of definitions, strategies, and canonical examples. IEEE Antenn Propag. M 50, 115–126 (2008).

Cheng, L. L., Yue, K. Z., Xing, C. F. & Yu, D. Z. RCS numerical simulation of stealth modified three-surface aircraft. Int. J. Aeronaut. Space Sci. 17, 101–108 (2016).

Kalaagi, M. & Seetharamdoo, D. Multiangle retrodirective cascaded metasurface. J. Appl. Phys. 126, 104901 (2019).

Dai, Y., Wu, X. Y., Liu, Z. S., Zhang, H. B. & Yu, Z. Z. Highly sensitive, robust and anisotropic MXene aerogels for efficient broadband microwave absorption. Compos. Part B Eng. 200, 108263 (2020).

Cheng, Y. et al. Lightweight and flexible cotton aerogel composites for electromagnetic absorption and shielding applications. Adv. Electron. Mater. 6, 201900796 (2020).

Li, Y. et al. Multifunctional organic-inorganic hybrid aerogel for self-cleaning, heat-insulating, and highly efficient microwave absorbing material. Adv. Funct. Mater. 29, 201807624 (2019).

Huang, X. G. et al. Ultralight magnetic and dielectric aerogels achieved by metal-organic framework initiated gelation of graphene oxide for enhanced microwave absorption. Nanomicro Lett. 14, 107 (2022).

Jiang, Y. et al. Hierarchically structured cellulose aerogels with interconnected MXene networks and their enhanced microwave absorption properties. J. Mater. Chem. C. 6, 8679–8687 (2018).

Liang, L. L. et al. Ultralight, flexible carbon hybrid aerogels from bacterial cellulose for strong microwave absorption. Carbon 162, 283–291 (2020).

Jiang, Y., Chen, Y., Liu, Y. J. & Sui, G. X. Lightweight spongy bone-like graphene@SiC aerogel composites for high-performance microwave absorption. Chem. Eng. J. 337, 522–531 (2018).

Song, S. K. et al. Carbon aerogel based composite phase change material derived from kapok fiber: Exceptional microwave absorbility and efficient solar/magnetic to thermal energy storage performance. Compos. Part B Eng. 226, 109330 (2021).

Mahani, A. A., Motahari, S. & Nayyeri, V. Electromagnetic and microwave absorption characteristics of PMMA composites filled with a nanoporous resorcinol formaldehyde based carbon aerogel. RSC Adv. 8, 10855–10864 (2018).

Wang, Y. Y. et al. Carbon aerogel microspheres with in-situ mineralized TiO2 for efficient microwave absorption. Nano Res. 15, 7723–7730 (2022).

Gu, W. H. et al. Environmentally friendly and multifunctional shaddock peel-based carbon aerogel for thermal-insulation and microwave absorption. Nanomicro Lett. 13, 102 (2021).

Zhao, H. B. et al. Magnetic and conductive Ni/carbon aerogels toward high-performance microwave absorption. Ind. Eng. Chem. Res. 57, 202–211 (2018).

Wang, K. J., Ye, Z. W., Li, X. Q. & Yang, J. N. Nanoporous resorcinol-formaldehyde based carbon aerogel for lightweight and tunable microwave absorption. Mater. Chem. Phys. 278, 125718 (2022).

Feng, L. et al. Superelastic, highly conductive, superhydrophobic, and powerful electromagnetic shielding hybrid aerogels built from orthogonal graphene and boron nitride nanoribbons. ACS Nano 16, 17049–17061 (2022).

Wu, N. et al. Ultrathin cellulose nanofiber assisted ambient-pressure-dried, ultralight, mechanically robust, multifunctional MXene aerogels. Adv. Mater. 35, 202207969 (2022).

Liang, C. B. et al. Ultra-light MXene aerogel/wood-derived porous carbon composites with wall-like “mortar/brick” structures for electromagnetic interference shielding. Sci. Bull. 65, 616–622 (2020).

Zeng, Z. H. et al. Ultralight and highly elastic graphene/lignin-derived carbon nanocomposite aerogels with ultrahigh electromagnetic interference shielding performance. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 10, 8205–8213 (2018).

Hu, P. Y. et al. Multifunctional aramid nanofiber/carbon nanotube hybrid aerogel films. ACS Nano 14, 688–697 (2020).

Wu, X. Y. et al. Compressible, durable and conductive polydimethylsiloxane-coated MXene foams for high-performance electromagnetic interference shielding. Chem. Eng. J. 381, 122622 (2020).

Lu, D. W. et al. Flexible, lightweight carbon nanotube sponges and composites for high-performance electromagnetic interference shielding. Carbon 133, 457–463 (2018).

Zhou, Z. H. et al. Structuring dense three-dimensional sheet-like skeleton networks in biomass-derived carbon aerogels for efficient electromagnetic interference shielding. Carbon 152, 316–324 (2019).

Xi, J. B. et al. Graphene aerogel films with expansion enhancement effect of high-performance electromagnetic interference shielding. Carbon 135, 44–51 (2018).

Liu, J. et al. Superelastic and multifunctional graphene-based aerogels by interfacial reinforcement with graphitized carbon at high temperatures. Carbon 132, 95–103 (2018).

Li, S. T., Liu, D. Y., Li, W. C. & Sui, G. X. Strong and heat-resistant SiC-coated carbonized natural loofah sponge for electromagnetic interference Shielding. ACS Sustain. Chem. Eng. 8, 435–444 (2020).

Yuan, Y. et al. Stiff, thermally stable and highly anisotropic wood-derived carbon composite monoliths for electromagnetic interference shielding. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 9, 21371–21381 (2017).

Yuan, Y. et al. Multifunctional stiff carbon foam derived from bread. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 8, 16852–16861 (2016).

Zheng, Y. et al. Lightweight and hydrophobic three-dimensional wood-derived anisotropic magnetic porous carbon for highly efficient electromagnetic interference shielding. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 12, 40802–40814 (2020).

Zhang, L. Y. et al. Phthalonitrile-based carbon foam with high specific mechanical strength and superior electromagnetic interference shielding performance. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 8, 7422–7430 (2016).

Wu, S. Q. et al. Ultralight and hydrophobic MXene/chitosan-derived hybrid carbon aerogel with hierarchical pore structure for durable electromagnetic interference shielding and thermal insulation. Chem. Eng. J. 446, 137093 (2022).

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (Y.L., 52225311), the Sichuan Science and Technology Program (Y.L., 2025NSFTD0011), and the Fundamental Research Funds for Central Universities (Y.L.).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Conceptualization: P.C. and Y.L. Methodology: P.C. Investigation: P.C., S.H., C.W. and J.T. Visualization: P.C., T.W. and Y.L. Funding acquisition: Y.L. and P.C. Data curation: P.C. and Y.L. Validation: P.C., S.H. and C.W. Formal analysis: P.C., S.H. and Y.L. Software: P.C. Project administration: Y.L. and P.C. Supervision: Y.L. and P.C. Resources: Y.L. and P.C. Writing—original draft: P.C. Writing—review and editing: P.C., T.W. and Y.L.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Peer review

Peer review information

Nature Communications thanks the anonymous reviewer(s) for their contribution to the peer review of this work. A peer review file is available.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Source data

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Chen, P., He, S., Wang, T. et al. Melanin-like nanofibers with highly ordered structures achieve ultrahigh specific electromagnetic interference shielding efficiency. Nat Commun 16, 7127 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-025-62367-9

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-025-62367-9

This article is cited by

-

Multifunctional Three-Dimensional Porous MXene-Based Film with Superior Electromagnetic Wave Absorption and Flexible Electronics Performance

Nano-Micro Letters (2026)

-

Emerging lignocellulose-based electromagnetic interference shielding materials towards multi-scenario applications

Science China Materials (2025)