Abstract

Avalanche photodiodes are crucial in emerging weak light signal detection fields. However, most avalanche photodiodes either suffer from relatively high breakdown voltage or relatively low gain, impairing the advantages of avalanche multiplication. Herein, we report the bilateral Geiger mode avalanche in two-dimensional Graphene/InSe/Cr asymmetrical Schottky junction. A high gain of 6.3 × 107 is yielded at low breakdown voltage down to 1.4 V approaching InSe’s threshold limit of bandgap. In addition to the separated carrier injection region and avalanche multiplication region, a positive temperature coefficient of the ionization rate and a very low critical electric field (11.5 kV cm–1) are demonstrated, leading to the nice performance. Such device architecture also enables low dark current and noise equivalent power, showing weak light signals detection ability down to around 35 photons at room temperature. This study provides alternative strategies for developing energy-efficient and high-gain avalanche photodiodes.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Avalanche photodiodes (APDs) that leverage carrier multiplication to detect weak light signals have widespread application scenarios such as optical communication, quantum cryptography, and light detection and ranging (LiDAR)1,2,3. In conventional APDs, an intense electron-phonon (e-ph) interaction results in a huge waste of energy during the charge-carrier acceleration process and inefficient carrier multiplication4,5. The multiplication region is generally in the order of micrometers, and carrier mean free path is to tens or hundreds of nanometers, which indicates that the carriers will take 10 more chances of impact. The charge multiplication mechanism involves one type of carrier requiring a large breakdown voltage (Vbd) to achieve pronounced gain6. Typically, the threshold voltage for Si APDs7 is up to 50 V, and the InGaAs APDs8 need to be biased over 60 V to achieve a multiplication factor over 105. Moreover, defect states from the heteroepitaxial growth9 and the device fabrication process10,11 usually accompany a high dark current, which will would result in stringent operational conditions and weaken the advantages of APDs.

Two-dimensional (2D) layered materials showing easy processing, strong light interaction, and quantum confinement effect have inspired investigations for highly efficient optoelectronic devices5,12,13,14,15,16. It is demonstrated that weak e-ph coupling and strong electron-hole interactions in 2D heterostructure result in efficient carrier multiplication14. Besides, the carrier multiplication phenomenon is observed by applying the small avalanche threshold energy, as low as twice the bandgap (Eg) of the 2D material5. The unique transport characteristics and structural features of 2D materials have been revealed, giving insight into the possible physical mechanisms17. These studies indicate that it is feasible to fabricate APDs with 2D materials, showing low avalanche threshold energy and efficient carrier multiplication.

By constructing stepwise WSe2 homojunction APD, a very low avalanche threshold energy approaching the fundamental limit of the Eg is reported18, but the multiplication gain of the device is only 470. The gain is improved to 5 × 105 by adopting the Schottky junction (SJ) structure. However, the Vbd is limited to 24 V far from the fundamental threshold limit of WSe219. The performance of APD is strongly related to the materials and structures selected, both affecting the impact ionization process. InSe is physically superior to WSe2 for larger thermal velocity20, which ensures a rapid acceleration of carriers to facilitate the impact ionization process. Gao at al. realize a large multiplication factor of up to about 3 × 104 at the voltage of 4.3 V in nanoscale vertical InSe/BP heterostructures15. Zhao et al.6 achieved a gain of 3 × 105 at 5.5 V in a Schottky junction built from the Graphite and n-InSe, while the Graphite/InSe APDs are limited to a low temperature because of the thermally assisted carrier transport of the SJ devices. Hence, it is a very promising route that one searches a high saturation veloextemecity 2D material and constructs a novel device structure with alternative mechanisms to realize a high gain at a very low Vbd.

In this paper, we design Graphene/InSe/Cr asymmetric Schottky junction (GISC-SJ) APD devices, where p-type InSe conducting behavior from intrinsic bipolar InSe is achieved along with the different work functions of the Graphene, InSe and Cr. The asymmetrical SJs significantly avail initiating impact ionization and multiplication for the injected majority carriers and the bilateral asymmetric Geiger mode avalanche phenomenon with a steep breakdown property is observed. A high multiplication factor of up to 6.3 × 107 is achieved in the GISC-SJ APDs at low Vbd. The Vbd is yielded to be 1.4 V approximately, which is close to the threshold energy limit of the Eg of the InSe. A positive temperature coefficient of the ionization rate and a small critical electric field (11.5 kV cm–1) are found in the InSe APDs. The GISC-SJ APDs can operate at room temperature showing low dark current below 620 fA, and weak light signals detection ability (around 35 photons). These characteristics indicate that taking asymmetrical InSe SJs is a promising approach for developing next-generation low-power consumption and high-gain APDs.

Results

PN Junction and Schottky Junction avalanche photodiodes

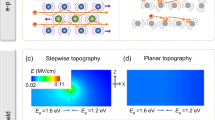

APDs are generally based on the PN or SJ junction, taking the junction’s strong electric field (εfield) under a reverse bias to trigger carrier impact ionization and multiplication. Traditional Si, Ge, InGaAs, and HgCdTe APDs are based on the PN junction (Fig. 1a), where the charge multiplication process involves one-carrier cascade impact ionization (Fig. 1b)21. These traditional APDs usually need a high Vbd due to the low density of final states, limitation of the momentum conservation rule, and rapid carrier cooling by phonon scattering5. It is essential to provide sufficient energy for each injected carrier to initiate impact ionization and the inefficient multiplication process4,5. In addition, linear avalanche is often accompanied by the Geiger mode one. Hence, the PN APDs display a larger dark current (Fig. 1c).

a Diagram device structure of a PN junction. P and N represent p-type and n-type semiconductor, while PN represent the depletion region of the PN junction. b Band diagram of a PN junction, showing the one-carrier multiplication process and dark current mechanisms. The shaded area represents the multiplication region. TAT and BBT denote trap-assisted tunneling and band-to-band tunneling, respectively. c The I-V curve for the PN APD. IGeiger, ILinear, and IR are the current of the Geiger mode, linear mode, and reversed saturation, respectively. d, e Diagram device structure and electron band structure of a 2D Schottky junction (SJ), showing the carrier multiplication process at the reverse and forward cases. The shaded areas represent the multiplication regions (depletion regions). f The I-V curve of a 2D SJ APD with bilateral avalanche breakdown. IDRI denotes the drift current.

Recently, great advances in 2D layered materials and their heterostructures have re-spurred investigations into the impact ionization for high-performance APDs5. Two distinct approaches are identified, namely field-effect transistor structure based on the SJ22,23 and heterostructure of the PN junction15,24. Thanks to the excellent switching characteristics and simple processes, the SJs well replace the PN ones in microwave devices and high electron mobility transistors25. For the 2D materials, Schottky barriers are readily formed by transferring Graphene, 2D semimetal or evaporating metal as electrodes (Fig. 1d, e). In addition, 2D SJs are free from extrinsic doping and the resulting defects, and thus a perfect interface between 2D materials and electrodes is built, which enables very low leakage current26,27. The reverse leakage current can also be further restrained by constructing a higher and broader Schottky barrier26,28.

In the APDs built from two SJs sitting back-to-back architecture, carriers conquer the first forward-biased barrier and arrive at the reverse-biased SJ (Fig. 1e). To realize a higher gain at a lower Vbd, the forward-biased SJ is designed with a lower barrier height for carriers to be easily injected. While the reverse-biased SJ has a higher barrier to provide a strong built-in electrical field and a longer multiplication region for carriers to proceed multiple times impact ionization. The Schottky barrier width W, i.e., multiplication region length, is described by the formula26, W = (2εsVbi/eNA)1/2. Here εs is the static dielectric constant of a semiconductor, Vbi = Фlow (or Фhigh)/e is the built-in potential, e is the elementary charge, NA = N2D/d is the body carrier concentration of the multiplication region, and Фhigh and Фlow denotes the high and low Schottky barriers, respectively. As depicted in Fig. 1d, more multiple times impact ionization and multiplication proceed where a wider W appears at the SJ due to the Фhigh. In this case, a higher multiplication factor (M) and a low breakdown voltage are present under forward bias (Fig. 1f). In contrast, when the lower Schottky barrier is reverse-biased, the majority carriers have to conquer the Фhigh to arrive at the multiplication region with a narrower W (Fig. 1e), which bring about a lower M and a larger breakdown voltage (Fig. 1f). Therefore, the bilateral avalanche in the asymmetrical SJs with different barrier is demonstrated showing a different multiplication behavior because of the diverse carrier injection barriers, multiplication regions and collection processes (Fig. 1f).

Device structure and avalanche breakdown characteristics

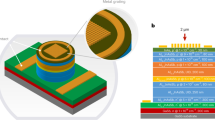

The schematic illustration of the GISC-SJ APDs structure with asymmetrical Graphene/InSe and Cr/InSe junction is plotted in the top panel in Fig. 2a. The InSe nanosheets are exfoliated from a bulk crystal and transferred onto Graphene flakes, and then Cr/Au electrodes are deposited as contacts (detailed information is present in the Methods). During the measurement, the bias on the Graphene and Cr electrode is defined as the forward and reverse bias, respectively. The thickness of InSe and Graphene are around 25 nm and 5 nm. The InSe and Graphene are well assembled, as confirmed by Raman spectra. The seven Raman peaks of the overlapping area of vertical InSe/Graphene (Supplementary Fig. 1) are well indexed by the phonon vibration modes of the γ-InSe and 2D Graphene28,29. Because of the vdW integration of InSe and Graphene, a well-defined and damage-free interface without the presence of any contamination or amorphous phases is also confirmed by the cross-sectional High-Resolution Transmission Electron Microscope (HRTEM) (Fig. 2b and Supplementary Fig. 2). The lattice spacing of 8.52 Å and vdW gap of 1.81 Å is in agreement with those of the γ-InSe along the [010] zone axis12,30, and atomic stack between the Graphene and InSe further indicates a nearly ideal interface (bottom panel in Fig. 2a). Such splendid contact behaviors will support excellent electrical performance and dozens of avalanche breakdown operations. At the InSe/Cr interface, however, a thin hybridized interlayer of the InSe and Cr is present (Fig. 2c). This non-ideal interfacial layer is possibly from the thermal deposition process, which is a universal behavior in 2D material devices31.

a 3D schematic illustration of the GISC-SJ APDs (top panel), and cross-sectional HRTEM image of an InSe/Graphene interface (bottom panel). The scale bar is 1 nm. b, c Cross-sectional HRTEM images of the InSe/Graphene and InSe/Cr interfaces. The scale bar is 1 nm. d Linear plots (red) and logarithmic plots (blue) I-V curves under a low bias. Inset is the optical image of the GISC-SJ APD and the scale bar is 5 μm. e The I-V characteristics curves of the GISC-SJ APD under the reverse and forward biases at 100 K. Inset is the I-V curve at 300 K. f The M dependence of the Vbd for a comparison of the GISC-SJ APDs, traditional semiconductors APDs, and other 2D materials APDs. Detailed values and references to the selected work can be found in Supplementary Table 1. Error bars are standard deviations of M and Vbd.

To ensure that an asymmetric Schottky barrier is formed, the InSe devices with symmetric electrodes are fabricated. Note that the I-V curves of the Cr/InSe/Cr and Graphene/InSe/Graphene devices show a nonlinear transport behavior, indicating a Schottky contact at both Cr/InSe and Graphene/InSe interfaces (Supplementary Fig. 3). More crucially, Cr and Graphene with different work functions are chosen to regulate the typical n-type to the weak p-type of the 2D InSe, which optimizes the multiplication ambiance, widens the multiplication region length, and thus facilitates the impact ionization6,15,32. The Schottky barrier is around 0.54 eV at the Cr/InSe side and 0.18 eV at the Graphene/InSe one (Supplementary Fig. 4), respectively, which confirms the formation of asymmetric back-to-back Schottky barriers in the GISC-SJ APDs. Figure 2d demonstrates obvious rectification behavior with a rectification ratio beyond 103 at |Vd | = 3 V. The GISC-SJ APD shows low dark current below 100 fA. These behaviors are also demonstrated in the other APD devices, reflecting the performance is closely related to the device structure and the high reliability of the GISC-SJ APDs with Cr and Graphene electrodes (Supplementary Fig. 5).

Next, the avalanche characteristics of the GISC-SJ APDs are examined. To study the effect of barrier height on breakdown characteristics, we first test the electrical performance of the device at low temperatures since thermionic exaction and thermal field emission induced carrier injection is greatly suppressed at this time. When the voltage sweeps from 0 V to –16 V, the dark current maintains at 100 fA and abruptly increases at a certain voltage (–12.9 V) at 100 K (Fig. 2e). The steep variation in current signals a typical avalanche breakdown. The same abrupt avalanche breakdown phenomenon is also observed when the voltage sweeps from 0 V to 10 V (Fig. 2e), implying a bilateral Geiger mode avalanche related to the bilateral Schottky barrier configuration design. More importantly, the GISC-SJ APD device exhibits a bilateral Geiger mode avalanche breakdown even in the ambient atmosphere (inset in Fig. 2e).

The multiplication factor M, a crucial parameter for an APD, is defined as33,34,35, M = I/Isat, where Isat is current at Vbd and I is the current above Vbd. A high M of ≈ 4.6 × 105 is obtained comparable to that of the commercial Si and InGaAs APDs while the Vbd is only –13.1 V, far lower than 40 V of Si and 60 V of InGaAs APDs8,35. Remarkably, the high M beyond 1.7 × 107 is achieved but with a low Vbd down to 5.1 V at the forward case, and this Vbd is further optimized to be lowered to ≈1.4 V, which is close to the theoretical threshold limit of Eg/e. To our best knowledge, this high M is larger than the value of 6 × 106 for the commercial Si APDs35. Note that the different M and Vbd at the forward and reverse cases evidence the device structure design of the asymmetric SJ with various barriers. The carriers can be readily injected at the Graphene/InSe side with a lower barrier under a smaller voltage, and thus effectively trigger impact ionization at the Cr/InSe interface where a strong built-in potential and a longer multiplication region are built. These behaviors are also demonstrated in the other APD devices, reflecting the design concept and operation principle of the GISC-SJ APDs (Supplementary Fig. 5). Additionally, negligible variation of the I-V curves at Geiger mode after dozens of cycling scans further implies the high reliability and robustness of the GISC-SJ APDs (Fig. 2e).

To evaluate these parameters, the M dependence of the Vbd for the commercial semiconductors Si35, Ge1, InGaAs/InP8, InAlAsSb36 and AlInAsSb/GaSb37 APDs, 2D materials APDs6,18,19,24,38, and the GISC–SJ APDs are summarized in Fig. 2f and Supplementary Table 1. For the typical commercial semiconductor APDs, a large threshold voltage is needed to initiate the carrier impact ionization to achieve the Geiger mode avalanche, such as M of 6 × 106 at 40 V for the Si APDs35, and M of 105 at a higher voltage of 60 V for the InGaAs/InP APDs8, which poses the severe requirements on material quality, operation conditions and signal processing for these semiconductor APDs. Note that the avalanche breakdown voltage is significantly reduced and can arrive at around 5 V for the new-type 2D materials APDs6. However, their multiplication factor M is below 3 × 105 much lower than that of the Si APDs. In contrast, for the GISC-SJ APDs, the M is yielded to be 1.7 × 107 and further optimized to be 6.3 × 107 while the Vbd ranges from 1.4 V to 5.1 V, which exhibits a significant advantage in terms of high multiplication gains and low breakdown voltages.

Avalanche breakdown characteristics and mechanism

To investigate the avalanche nature of the GISC-SJ APDs with high M and low Vbd, variable temperature experiments are conducted and the I-V curves at temperatures from 100 K to 200 K are given in Fig. 3a and Supplementary Fig. 6. This can reveal the competition of the thermal carrier transport, lattice vibration scattering and e-ph coupling, and thus well sheds light on the physics of the carrier transport and multiplication6,16. The avalanche Vbd at either a forward or reverse bias decreases with increasing the temperature, i.e. a negative temperature coefficient of the Vbd, which is in contrast to those of the traditional PN APDs where a positive temperature coefficient of the Vbd is present because of the enhanced phonon scattering with the increase of the temperature39. The threshold voltage (Vth) decreases with the temperature at either a forward or a reverse bias case (Fig. 3b and Supplementary Fig. 8), which well follows the transport behaviors of SJ diodes with temperature due to the narrowing of bandgap with increasing temperature40. Note that the Vbd shows the same evolution as that of the Vth with the temperature. Crucially, notice that the M does not decay with increasing the temperature at both the reverse and forward biases (Fig. 3b and Supplementary Fig. 8). These data indicate that the majority carrier injection can avail avalanche thanks to the drop of the Schottky barrier resulting from the Fermi-Dirac distribution expanding to a higher level with the temperature. This is also reflected by the asymmetrical Schottky barriers related different Vbd at Cr/InSe (Fig. 3a Inset II) and Graphene/InSe (Fig. 3a Inset III) sides, respectively.

a I-V curves at different temperatures from 100 K−200 K under the reverse and forward biases. The inset II and III at the bottom shows that the high Schottky barrier at the Cr/InSe interface prevents the injection of holes at a low bias, while the low Schottky barrier at the Cr/InSe one allows the injection of holes at a low bias. The inset I at the top gives the impact of the reduced dimensionality of e-ph coupling on the carrier acceleration and multiplication process. b The dependence of the Vth, Vbd, and M on the temperature at the forward bias case. c α as a function of the inverse electric field at the selected temperatures of 100 K, 140 K and 200 K, respectively. The inset is the dependence of electric field strength on the temperature when α is fixed at 103 cm−1. The dotted lines are a guide for the eyes. d The I-V curves of Cr/InSe/Cr devices with different channel lengths, from right to left, correspond to channel lengths of 4.58, 3.65, 2.47, 1.62, and 0.71 μm respectively. e The Vbd versus the channel length, and the dotted plot is a linear fit. The error bar shows the error in determining the breakdown voltage by identifying the current breakdown point from the repeated I-V curves, which is extracted from Supplementary Fig. 9e–i. The inset is the optical image of the Cr/InSe/Cr APDs with different channel lengths. The scale bar is 5 μm. f The dependence of the ECR on the Eg for the InSe APDs, conventional semiconductors APDs, and 2D MoS2, WSe2, BP APDs. Detailed values and references to the selected work can be found in Supplementary Table 2.

In these cases, the injected holes pass difficultly through the Cr/InSe interface at a low reverse bias, and easily through the lower barrier Graphene/InSe one at a low forward bias as shown in the inset in Fig. 3a (Inset II). Hence, a higher M at a forward bias is demonstrated because of the different carrier injection efficiencies as given in Fig. 2e, Fig. 3b and Supplementary Fig. 8. Moreover, multiplication processes are enhanced by constructing the efficient multiplication region through tuning the typical n-type InSe to a weak p-type. Nearly perfect interface configurations of the Graphene/InSe also avail the carrier collection. Consequently, a lower Vbd and a higher M are present at the forward bias in the GISC-SJ APDs. Notably, the carrier multiplication in our asymmetrical SJ APDs is triggered by the majority carriers. This differs from the multiplication mechanism of the traditional PN APDs, where the multiplication is involved by the minority carriers at a large reverse bias. These also imply that it is an efficient route to optimize the Vbd by construction of an asymmetrical Schottky junction with a higher built-in barrier difference. To confirm the drop of the Vbd is closely correlated to the asymmetric Schottky barriers, Cr/InSe/Cr devices with a similar InSe thickness of 27.4 nm are also fabricated, and the Vbd is 10.6 V, twice as large as that of the GISC devices as shown in the Supplementary Fig. 9.

Generally, a high temperature lowers the impact ionization process since the enhanced lattice vibrations significantly reduce the carrier mean-free path and induce severe e-ph coupling in traditional semiconductor materials and devices41. In layered 2D materials, however, a large vdW gap (EvdWg) is present between the interlayers and the EvdWg of InSe is 1.85 eV (Fig. 3a Inset I), which can well undertake a large potential barrier, and thus avail the in-plane carrier movement and suppresses the out-of-plane charge transport17,42. Compared to the multiplication processes of traditional materials APDs, hence, 2D materials lose less energy related to the quantum confinement effect with the aid of the EvdWg, and the Vbd dramatically drops in 2D APDs. To confirm this result, a crucial characteristic parameter, ionization rate α reflecting the multiplication ability for an APD device, is calculated. It is defined as the number of generated electron-hole pairs by an initial charge carrier per unit distance traveled and described by the formula43,44, α = 1/L(1 − 1/M) (detailed discussion is provided in Supplementary note 1). Here M is the multiplication factor, α is the ionization rate (here α of hole and electron are assigned to be equal) and L is the multiplication region length. The detailed α under the forward and reverse biases is given in Supplementary Fig. 7. As a typical case, Fig. 3c shows the dependence of the α on the inverse electrical field (εfield) at the selected temperatures of 100 K, 140 K, and 200 K, and the inset gives the temperature dependence of the εfield at the fixed αp of 103 cm–1. Note that, at a lower temperature, a larger εfield is applied to initiate the same impact ionization, while the avalanche readily occurs at a higher temperature, i.e. a larger ionization rate at a lower εfield. This is in contrast to those of the traditional PN APDs where the α is lowered with increasing temperature due to the enhanced lattice vibration and e-ph scattering39.

The large εfield for initiating the ionization breakdown and strong correlation of the α with the εfield indicate the lower ionization possibility led by the lower thermal carrier saturation velocity (Vsat) and longer mean free path despite the weak lattice vibration scattering at a lower temperature (Fig. 3c). When the temperature increases from 100 K−200 K, however, the εfield needed to achieve the same impact ionization level (103 cm–1) decreases significantly around three times (inset in Fig. 3c). This implies that the higher thermal carriers Vsat and shorter mean free path defeat overwhelmingly the phonon scattering, and thus enhance impact possibility and dominate the avalanche processes at a higher temperature. This can be attributed to the unambiguously proofed weak e-ph coupling and large EvdWg barrier in 2D InSe6. Hence, a weak correlation of the α to the εfield, and easy ionizing at a higher temperature are demonstrated in the GISC-SJ APDs (Fig. 3c), which is further supported by the M increment with increasing the temperature at both the forward and reverse biases (Fig. 3b and Supplementary Fig. 8). These results clearly point to the low Vbd in the asymmetric GISC-SJ APDs.

The critical electric field (ECR) is an important characteristic parameter, reflecting the intrinsic properties of a semiconductor and its device, and closely correlated to the Eg and the depletion region width W, namely multiplication region length. The W depends on the applied voltage. To obtain ECR, the InSe SJ APDs with various channel lengths L from 0.76 μm to 4.58 μm are fabricated (Supplementary Fig. 10). Their I-V characteristic curves are given in Fig. 3d and the optical image is plotted in the inset in Fig. 3e. Note that the Vbd drops from 2.34 V to 0.57 V as the L decreases from 4.58 μm to 0.76 μm (Fig. 3d). Crucially, the Vbd shows a linear decrease trend when the L is above 1.6 μm, implying that the channel is not completely depleted and thus the effective W is lower than the L. Therefore, the effective W should be below 1.6 μm. However, with further shrinking the L to 0.76 μm, the I-V curve deviates from the linear dependence, and a platform appears as indicated by the arrow in Fig. 3d, i.e. a negative differential resistance behavior, which is the typical characteristic for a tunneling effect transistor. Obviously, when the L is 0.76 μm, the tunneling effect is present in this InSe SJ device. This also reflects the intrinsic avalanche effect rather than the tunneling in the long L InSe SJ APDs. The effective W is thus in the range from 0.76 μm to 1.6 μm, which is in agreement with that of the photocurrent mapping (Supplementary Fig. 11). In addition, the ECR is yielded to be 11.5 kV cm–1 defined by the slope of the relation of the Vd to the L (Fig. 3e). Figure 3f shows a comparison of the ECR for the GISC-SJ APDs, other 2D materials16,23,44 and bulk semiconductors APDs45. The ECR is closely dependent on the Eg for the bulk semiconductors, and the lowest ECR of Ge APDs only approaches to 100 kV cm–1. In contrast, the ECR is nearly independent on the Eg for the 2D BP23, WSe216, MoS244 and our InSe SJ APDs, and their ECR is much lower than those of the bulk material APDs44,45. A low ECR is demonstrated in the InSe APDs, which is another crucial factor for the high M and low Vbd in the asymmetric GICS-SJ APDs.

Room-temperature photoresponse performance

Based on the excellent electrical performance of the device, we characterize the detection performance of the device at room temperature. As presented in Fig. 4a, the dark I-V curve showcases a low dark current of 6.2 × 10–13 A at bias levels below –2 V and low breakdown voltage of 2.9 V. As the bandgap III − VI compound semiconductor showing direct bandgap structure in multilayer regime, InSe has always been an excellent optoelectronic material for visible light detection46,47. To study the optical performance of InSe based photodetectors, we first measure the photoresponse at 520 nm. Laser illumination precipitates earlier photocurrent avalanche onset and the avalanche breakdown voltage decreases from 2.6−1.8 V with the increase of the P from 70.7−418.7 fW due to increased light power (Fig. 4a). The avalanche gain (G) is calculated by the formula48,49, G = (Iph – Idark)/(Iph0 – Idark0). Here Iph and Idark denote the photocurrent and dark current, and Iph0 and Idark0 are the photocurrent and dark currents with G = 1. The G of the GISC-SJ APD reaches a high level of 3.5 × 106 (Fig. 4b), which enables the device to have a very high responsivity of 4.8 × 106 A W–1 after avalanche multiplication (Fig. 4b inset).

a I-V curves at darkness and laser powers from 70.7 fW to 418.7 fW with a laser wavelength of 520 nm at room temperature. b Gain as a function of the operation voltage at the power of 70.7 fW. Inset is the responsivity as a function of the operation voltage. c Normalized photoresponsivity as a function of the wavelength obtained in the GICS-SJ device (red dot line) and the increased ratio of device responsivity in APD mode compared with in photovoltaic (PV) mode (blue dot). d Normalized frequency response at different reverse biases when the incident light wavelength is 520 nm. e Noise current of the GICS-SJ APD with different biases as a function of frequency at 300 K. f Comparison of responsivity and detectivity for the GICS-SJ APDs, and other 2D materials APDs, PV and PG detectors. Detailed values and references to the selected work can be found in Supplementary Table 4.

The red dot line in Fig.4c displays the normalized photoresponsivity as a function of the wavelength obtained in the GISC-SJ APD device. It can be seen that the device shows the strongest response to light in the 520 nm band and achieves a wide spectral response ranging from 520 nm to 1550 nm (Supplementary Fig. 12), which exceeds the cut-off wavelength of InSe due to internal photoelectron emission (IPE) effect50,51,52,53. In the PV mode, the device shows the maximum responsivity of 4.5 × 10–3 A W–1 at 520 nm (Supplementary Table 3), and the responsivity gradually decreases as the wavelength increases. When the detection wavelength exceeds the cut-off wavelength of InSe, due to the low quantum efficiency of the IPE effect54, the responsivity at 1270, 1450, and 1550 nm are also very low, which are 3.8 × 10–8, 9.9 × 10–9 and 3.7 × 10–9 A W–1, respectively (Supplementary Table 3). In APD mode, the responsivity of the device is greatly improved due to avalanche gain (blue dot in Fig. 4c extracted from Supplementary Fig. 12 and 13a). The responsivity at 520 nm has been enhanced by five orders of magnitude to 158.8 A W–1. This value is smaller than that of 4.8 × 106 A W–1, which is due to the relatively large test light power for spectrum test. In the near-infrared band, the photoresponse has been increased by about 7 orders of magnitude and the responsivity at 1550 nm reaches 6.7 × 10–2 A W–1 (Supplementary Table 3). Supplementary Fig. 13b shows the variable power response of the device at 1550 nm, demonstrating that the device can sense light signals with its intensity down to 96.2 nW.

To further demonstrate the advantage in time response and weak light detection characteristic of the GISC-SJ APD, we assessed the 3 dB bandwidth and noise equivalent power (NEP) at different biases. Figure 4d displays normalized frequency response at different reverse biases when the incident light wavelength is 520 nm. It can be seen that the 3 dB bandwidth increase abruptly after breakdown, which is due to rf enhancement effect49. The 3 dB bandwidth obtained is 121 kHz when biased at –3 V. Figure 4e shows the noise power spectral density of the GISC-SJ APD with different biases as a function of frequency at 300 K. It can be seen that the noise shapes of the device before and after avalanche are significantly different. The noise after the avalanche is mainly 1/f noise, which is similar to the noise currents of previously reported InSe/BP15 and Ni/WSe2/Pt APD19. The measured noise current (Inoise) at 1 Hz and 50 kHz are 1.9 × 10–7 and 1.9 × 10–10 A Hz–1/2, respectively, under the bias voltage of –3 V. The NEP is calculated using: NEP = Inoise/R, where R is the responsivity of the photodetector55. The GISC-SJ APD achieves a very low NEP of 39.6 fW Hz–1/2 at 300 K, which is comparable to the NEP of the reported single-photon detectors1. Such a low NEP and low light power of 70.7 fW (Fig. 4a) measured at 520 nm indicates that the device can sense light signals with its intensity down to 35 photons in the count (the detailed calculation is given in Supplementary Fig. 14). To further verify the excellent photoresponse performance of the GISC-SJ APD, we make a comparison of our GISC-SJ APD and other 2D materials APDs, photovoltaic (PV) and photogating (PG) detectors. Figure 4f and Supplementary Table 3 show the comparison of responsivity and detectivity at visible light. It can be seen that the GISC-SJ APDs display the highest responsivity and comparable detectivity.

Discussion

In summary, asymmetrical Graphene/InSe/Cr SJ APD configuration is designed and fabricated. The device demonstrates bilateral Geiger mode avalanche breakdown with different forward and reverse Vbd and M. The GISC-SJ APDs show high gain from 6.5 × 106 to 6.3 × 107 at low Vbd from 1.4 V to 6.3 V. The very low Vbd of 1.4 V approaches its threshold limit of Eg of InSe. A positive temperature coefficient of the α, and very low ECR of 11.5 kV cm-1 are found in the GISC-SJ APDs. Besides the designed asymmetric Schottky barrier configurations, these characters allow low bias trigging impact ionization and low-loss carrier multiplication. The GISC-SJ APD achieves a low dark current of 620 fA, and low NEP of 39.6 fW Hz–1/2, showing few photons detection ability of around 35 photons at room temperature. The design concept and operation principle of the InSe asymmetrical Schottky junctions provide a promising approach for developing weak light detectors with high gain and low loss.

Methods

Device fabrication

The Graphene used here is mechanically exfoliated from the bulk material provided by HQ Graphene and then transferred to a highly p-doped silicon substrate with 285 nm SiO2. While 2D InSe is mechanically exfoliated from bulk materials supplied by 6Carbon Technology. By the fixed-point transfer method on a self-constructed transfer platform, the InSe nanosheets are stacked on the Graphene. Electron-beam photolithography is used to depict the electrode patterns, and then the metal films Cr/Au (15/45 nm) are deposited by thermal evaporation. After the lift-off process, the Cr/InSe/Graphene devices are successfully fabricated. Notably, Cr/InSe/Cr devices with various channels are prepared by transferring InSe on hBN through the same process.

Material characterization

Optical and dark field images of the devices are characterized on an Olympus BX51 microscope. Lab Ram HR800 from HORIBA with a 532 nm excitation laser and Olympus × 100 objective lens performs the Raman spectrum. A cross-sectional sample containing the Graphene/InSe and Cr/InSe interfaces is prepared by a focused ion beam (FEI Helios G4 UX), and HRTEM is conducted using JEOL JEM-ARM300 to obtain the interface information. The thickness, channel lengths, and surface potential differences are measured by using AFM and SKPM on an Oxford Cypher S microscope.

Electrical and optoelectronic characterization

The temperature-dependent measurements are conducted with a commercial Keysight B1500A connected to a Lake Shore probe station. For temperature-dependent measurements, the sample is first cooled to 100 K, and the I-V curves at different temperatures were recorded after the temperature is reached and stabilized for 10 min. Alternating forward and reverse biases are applied to the sample to character bilateral avalanche breakdown. An external laser source (Thorlabs LP520-SF15) is introduced to excite the devices to perform a broad spectral response (520, 830, 1310, 1550 nm). The room temperature I-V curves and I-Vg curves are measured by an MS200 optoelectronic measurement system from Maita Optoelectronic Technology Co., LTD. A 520 nm laser is incident on the sample area to perform variable power response. The transient response and −3 dB bandwidth are recorded by an MS200 system using a PicoScope 4262 oscilloscope and a low-noise current preamplifier (SR570, Stanford Research Systems). The noise spectra of the APD are measured up to 50 kHz using a signal analyzer (Keysight 35670 A) combined with a low noise current preamplifier powered by electric batteries (SR570, Stanford Research Systems).

Data availability

The Source Data underlying the figures of this study are available with the paper. All raw data generated during the current study are available from the corresponding authors upon request. Source data are provided in this paper. Source data are provided with this paper.

References

Na, N. et al. Room temperature operation of germanium-silicon single-photon avalanche diode. Nature 627, 295–300 (2024).

Chen, Y. A. et al. An integrated space-to-ground quantum communication network over 4,600 kilometres. Nature 589, 214–219 (2021).

Shi, Y. et al. Avalanche photodiode with ultrahigh gain-bandwidth product of 1,033. GHz. Nat. Photonics 18, 610–616 (2024).

Aerts, M. et al. Highly efficient carrier multiplication in PbS nanosheets. Nat. Commun. 5, 3789 (2014).

Kim, J.-H. et al. Carrier multiplication in van der Waals layered transition metal dichalcogenides. Nat. Commun. 10, 5488 (2019).

Zhang, Z. et al. Approaching intrinsic threshold breakdown voltage and ultra-high gain in graphite/InSe Schottky photodetector. Adv. Mater. 34, 2206196 (2022).

Hall, D., Liu, Y.-H. & Lo, Y.-H. Single photon avalanche detectors: prospects of new quenching and gain mechanisms. Nanophotonics 4, 397–412 (2015).

Signorelli, F. et al. Low-noise InGaAs/InP single-photon avalanche diodes for fiber-based and free-space applications. IEEE J. Sel. Top. Quantum Electron. 28, 1–10 (2022).

Guo, Z. et al. Material defects and dark currents in InGaAs/InP avalanche photodiode devices. IEEE Trans. Electron Devices 69, 4944–4949 (2022).

Lei, W., Antoszewski, J. & Faraone, L. Progress, challenges, and opportunities for HgCdTe infrared materials and detectors. Appl. Phys. Rev. 2, 041303 (2015).

Ma, Y. et al. Impact of etching on the surface leakage generation in mesa-type InGaAs/InAlAs avalanche photodetectors. Opt. Express 24, 7823–7834 (2016).

Liu, Y., Huang, Y. & Duan, X. Van der Waals integration before and beyond two-dimensional materials. Nature 567, 323–333 (2019).

Xia, F., Wang, H., Xiao, D., Dubey, M. & Ramasubramaniam, A. Two-dimensional material nanophotonics. Nat. Photonics 8, 899–907 (2014).

Barati, F. et al. Hot carrier-enhanced interlayer electron-hole pair multiplication in 2D semiconductor heterostructure photocells. Nat. Nanotechnol. 12, 1134–1139 (2017).

Gao, A. et al. Observation of ballistic avalanche phenomena in nanoscale vertical InSe/BP heterostructures. Nat. Nanotechnol. 14, 217–222 (2019).

Choi, H. et al. A steep switching WSe2 impact ionization field-effect transistor. Nat. Commun. 13, 6076 (2022).

Kang, T. et al. Anisotropy of impact ionization in WSe2 field effect transistors. Nano Converg. 10, 13 (2023).

Wang, H. et al. Room-temperature low-threshold avalanche effect in stepwise van-der-Waals homojunction photodiodes. Nat. Commun. 15, 3639 (2024).

Li, X. et al. Achieving a noise limit with a few-layer WSe2 avalanche photodetector at room temperature. Nano Lett. 24, 13255–13262 (2024).

Jiang, J., Xu, L., Qiu, C. & Peng, L.-M. Ballistic two-dimensional InSe transistors. Nature 616, 470–475 (2023).

Capasso, F. Band-gap engineering: from physics and materials to new semiconductor devices. Science 235, 172–176 (1987).

Seo, J. et al. Ultrasensitive Photodetection in MoS2 avalanche phototransistors. Adv. Sci. 8, e2102437 (2021).

Ahmed, F. et al. Impact ionization by hot carriers in a black phosphorus field effect transistor. Nat. Commun. 9, 3414 (2018).

Son, B. et al. Efficient avalanche photodiodes with a WSe2/MoS2 heterostructure via two-photon absorption. Nano Lett. 22, 9516–9522 (2022).

Zhang, Y. et al. High-speed transition-metal dichalcogenides based Schottky photodiodes for visible and infrared light communication. ACS Nano 16, 19187–19198 (2022).

Zhang, X. et al. Near-ideal van der Waals rectifiers based on all-two-dimensional Schottky junctions. Nat. Commun. 12, 1522 (2021).

Kwon, G. et al. Interaction- and defect-free van der Waals contacts between metals and two-dimensional semiconductors. Nat. Electron. 5, 241–247 (2022).

Dai, M. et al. Ultrafast and sensitive self-powered photodetector featuring self-limited depletion region and fully depleted channel with van der waals contacts. ACS Nano 14, 9098–9106 (2020).

Dai, M. et al. Robust piezo-phototronic effect in multilayer γ-inse for high-performance self-powered flexible photodetectors. ACS Nano 13, 7291–7299 (2019).

Hao, Q. et al. Phase identification and strong second harmonic generation in pure ε-InSe and its alloys. Nano Lett. 19, 2634–2640 (2019).

Wang, Y. & Chhowalla, M. Making clean electrical contacts on 2D transition metal dichalcogenides. Nat. Rev. Phys. 4, 101–112 (2021).

Hu, S. et al. Reconfigurable InSe electronics with van der Waals integration. Adv. Electron. Mater. 8, 2101176 (2022).

Lei, S. et al. An atomically layered InSe avalanche photodetector. Nano Lett. 15, 3048–3055 (2015).

Jia, J. et al. Avalanche carrier multiplication in multilayer black phosphorus and avalanche photodetector. Small 15, e1805352 (2019).

Zhao, D. et al. Controllable photocurrent generation in lateral bilayer MoS2–WS2 heterostructure. Adv. Opt. Mater. 11, 2300709 (2023).

Chen, D. K. et al. Photon-trapping-enhanced avalanche photodiodes for mid-infrared applications. Nat. Photonics 17, 594–600 (2023).

Jones, A. H., March, S. D., Bank, S. R. & Campbell, J. C. Low-noise high-temperature AlInAsSb/GaSb avalanche photodiodes for 2 μm applications. Nat. Photonics 14, 559–563 (2020).

Xia, H. et al. Pristine PN junction toward atomic layer devices. Light Sci. Appl. 11, 170 (2022).

Groves, C., Ghin, R., David, J. P. R. & Rees, G. J. Temperature dependence of impact ionization in GaAs. IEEE Trans. Electron Devices 50, 2027–2031 (2003).

Isik, M. & Gasanly, N. M. Temperature-tuned band gap characteristics of InSe layered semiconductor single crystals. Mater. Sci. Semicond. Process. 107, 104862 (2020).

Crowell, C. R. & Sze, S. M. Temperature dependence of avalanche multiplication in semiconductors. Appl. Phys. Lett. 9, 242–244 (1966).

Sangwan, V. K. & Hersam, M. C. Electronic transport in two-dimensional materials. Annu. Rev. Phys. Chem. 69, 299–325 (2018).

Kim, J. et al. Channel-length-modulated avalanche multiplication in ambipolar WSe2 field-effect transistors. ACS Nano 16, 5376–5383 (2022).

Pak, J. et al. Two-dimensional thickness-dependent avalanche breakdown phenomena in MoS2 field-effect transistors under high electric fields. ACS Nano 12, 7109–7116 (2018).

Hudgins, J. L., Simin, G. S., Santi, E. & Khan, M. A. An assessment of wide bandgap semiconductors for power devices. IEEE Trans. Power Electron. 18, 907–914 (2003).

Liu, W. et al. Self-powered and broadband opto-sensor with bionic visual adaptation function based on multilayer γ-InSe flakes. Light Sci. Appl. 12, 180 (2023).

Shang, H. et al. Carrier recirculation induced high-gain photodetector based on van der waals heterojunction. ACS Nano 16, 21293–21302 (2022).

Gibson, S. J. et al. Tapered InP nanowire arrays for efficient broadband high-speed single-photon detection. Nat. Nanotechnol. 14, 473–479 (2019).

Liu, Q. et al. Ultraviolet response in coplanar silicon avalanche photodiodes with CMOS compatibility. Sensors 22, 3873 (2022).

Li, Z. et al. Telecom-band waveguide-integrated MoS2 photodetector assisted by hot electrons. ACS Photonics 9, 282–289 (2022).

Lu, Y. et al. Hot carrier transport and carrier multiplication induced high performance vertical graphene/silicon dynamic diode generator. Adv. Sci. 9, 2200642 (2022).

Peng, L. et al. Macroscopic assembled graphene nanofilms based room temperature ultrafast mid-infrared photodetectors. InfoMat 4, e12309 (2022).

Shao, W., Hu, J. & Wang, Y. Five-layer planar hot-electron photodetectors at telecommunication wavelength of 1550 nm. Opt. Express 30, 25555–25566 (2022).

Shao, W. et al. Planar hot-electron photodetection with polarity-switchable photocurrents controlled by the working wavelength. Opt. Express 31, 25220–25228 (2023).

Wang, Y. et al. Fast uncooled mid-wavelength infrared photodetectors with heterostructures of van der waals on epitaxial HgCdTe. Adv. Mater. 34, e2107772 (2021).

Acknowledgements

This work was partially supported by Development Program of China (Grant Nos. 2021YFA1200700 (J.W.), 2024YFA1211500 (Y.C.), 2024YFA1409700 (Y.C.)), Natural Science Foundation of China (Grant Nos. 62174055 (W.B.), 62025405 (J.W.), 62222413 (X.W.), 62334001 (X.W.)), Natural Science Foundation of Shanghai (Grant No. 23ZR1473400 (X.W.)).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

D.Z. and Y.C. contributed equally to the work. Y.C., X.W. and W.B. conceived and supervised the research. D.Z., T.H., H.C., X.Z., and Y.J. performed the device characterizations. X.W., H.S., J.Y., Y.Z., X.T., J.W. and J.C. advised on the experiments and data analysis. X.W., Y.C., and J.W. provided experimental testing support. W.B. was responsible for project planning. D.Z. and Y.C. analyzed the data and drafted the manuscript. X.W., Y.C., and W.B. revised the manuscript. All authors discussed the results.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Peer review

Peer review information

Nature Communications thanks the anonymous reviewer(s) for their contribution to the peer review of this work. A peer review file is available.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Source data

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Zhao, D., Chen, Y., Hu, T. et al. Bilateral Geiger mode avalanche in InSe Schottky photodiodes. Nat Commun 16, 7859 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-025-62383-9

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-025-62383-9