Abstract

This phase II trial aims to determine the efficacy and safety of frontline acalabrutinib, lenalidomide and rituximab for patients with advanced stage follicular lymphoma (FL) and high tumor burden. The primary endpoint was best complete response (CR) rate; the secondary endpoints were overall response rate (ORR), duration of response measured as CR at 30 months (CR30), progression of disease at 24 months (POD24) rate, progression-free survival (PFS), overall survival and safety. Twenty-four patients with previously untreated FL were included in this phase 2 single arm study (NCT04404088). The most common grade 3-4 adverse events were neutropenia (58%) and liver function test elevation (17%). Best ORR was 100% and best CR rate was 92%. CR30 rate was 65% and POD24 rate was 17%. After a median follow-up of 43 months, median PFS and OS were not reached, 2-year PFS rate was 79% and 2-year OS rate was 92%. Here we show that the addition of acalabrutinib to R2 is a safe and effective frontline regimen for FL patients, and further exploration in larger clinical trials is needed.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Follicular lymphoma (FL) affects mainly elderly and frail patients, challenging the use of standard frontline chemoimmunotherapy1,2. The combination of lenalidomide and rituximab, also referred to as R2, showed to be safe and effective as compared to chemoimmunotherapy as frontline treatment for patients with advanced stage FL meeting indications for treatment, in the randomized phase III RELEVANCE trial3,4. However, due to lack of superiority, while recommended by the National Comprehensive Cancer Network guidelines, R2 is not currently approved by the Food and Drug Administration as a frontline regimen in FL. Of interest, achievement of complete response (CR) as best response was associated with significantly prolonged progression-free survival (PFS) during frontline use of R2 in FL, suggesting that modifications of this regimen aimed at increasing CR rates may translate into superior activity5. In addition, while long-term follow-up data from the RELEVANCE trial show a 6-year PFS-rate of 60%, it remains unclear whether a maintenance is needed after 12 cycles of R2, and no difference in 8-year PFS rates were observed in the previous phase II study based on treatment duration4,5.

We previously demonstrated that subsets of pro-tumoral macrophages are increased at time of progression after frontline R2 in FL patients, suggesting that they may be associated with resistance to this regimen6. Bruton tyrosine kinase (BTK) inhibitors, through a dendritic cell-specific ICAM-3 grabbing non-integrin-mediated mechanism, can interrupt the cross-talk between FL cells and macrophages, inducing downregulation of pro-survival pathways in FL cells7,8. As compared to ibrutinib, acalabrutinib seems to yield a higher potential, because it does not directly hamper macrophage anti-tumoral activity9. We therefore hypothesized that the addition of acalabrutinib to R2 will increase efficacy due to beneficial effect on tumor-associated macrophages, in addition to its direct anti-lymphoma activity. The safety of this combination, also referred to as aR2, was investigated in a phase I study including 29 patients with relapsed/refractory FL and was shown to be well tolerated and identified the recommended phase II dose for acalabrutinib and R2 10.

Here we conducted a phase II trial to determine the efficacy and safety of frontline aR2 in patients with advanced stage FL and high tumor burden. Additionally, we performed an exploratory analysis to investigate the impact of this regimen on circulating immune cells and its ability to eradicate minimal residual disease (MRD).

Results

Patients

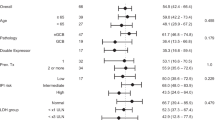

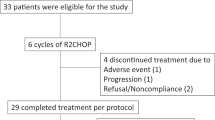

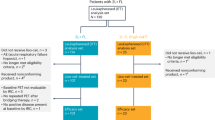

Thirty-one patients were screened between 07/2020 and 08/2021, and twenty-four patients were included in the study (Supplementary Fig. 1). All patients were evaluable for safety and efficacy. Median age was 62 (range, 40–82 years), 18 (75%) were male, and 22 (92%) were Caucasian. Baseline median largest lymph node size was 6.3 cm (range, 1.9–15 cm), median SUVmax was 14 (range, 6.3–35.9), and 17 (71%) patients had intermediate or high FLIPI score. Most patients (92%) had FL grade 1 to 2, and 50% had bone marrow involvement. Remaining baseline characteristics are shown in Table 1.

The median number of delivered cycles was 13 (range, 6–13). Twenty patients received the planned 13 cycles; 2 patients stopped after 6 cycles due to progressive disease; 1 patient died of severe COVID-19 pneumonia after 10 cycles, while in CR; and 1 patient stopped after 11 cycles, due to brain abscess of unclear etiology, responsive to empiric antibiotic therapy. Fifteen (62.5%) patients experienced a cycle delay; this trial took place during the COVID-19 pandemic, and cycle delay was due to COVID-19 infection in 11 (46%) patients. Toxicity-related dose reduction in lenalidomide was required in 6 (25%) patients, but none required lenalidomide discontinuation. Toxicity-related dose reduction in acalabrutinib was required in 2 (8%) patients, and 1 patient discontinued acalabrutinib after a grade 1 retinal bleeding due to a pre-existent condition.

Safety

The most frequently reported AEs of any grade during treatment were neutropenia (91%), anemia (83%), fatigue (79%), thrombocytopenia (67%) and headache (58%). Most of these AEs were grade ≤2, except for neutropenia. Fifty-eight percent of patients experienced grade ≥3 neutropenia, and 14 (58%) needed growth factor support, a median of 2 times (range, 1–8). However, no patient experienced neutropenic fever. The second most frequent grade ≥3 AE was represented by liver function test (LFT) elevation, including alanine aminotransferase elevation (17%) and aspartate aminotransferase elevation (12.5%), but not bilirubin elevation. Lenalidomide was held for LFT elevation of any grade, and was, along with COVID-19 infection, the main cause for cycle delay. All cases of LFT elevation resolved within 2 weeks, and only 2 patients required dose reduction in lenalidomide due to a second recurrence of grade ≥3 LFT elevation.

Overall, infections were experienced by 45.5% of patients throughout the treatment and were grade ≥3 in 12.5%. Infections observed during treatment were mainly related to COVID-19.

Skin rash was observed in 50% of patients and was grade ≥3 in 8%. In most patients, it was loco-regional, and was managed with topical corticosteroids, oral antihistamines, and oral lysine. No patient required use of systemic corticosteroids nor dose reduction of lenalidomide due to skin rash. One patient developed atrial fibrillation, and none had severe bleeding. One patient developed a second primary malignancy (desmoid fibromatosis), deemed not related to treatment. The malignancy was diagnosed 3 years after initiation of treatment and managed with observation only. Additional details regarding incidence and grade for all AEs are shown in Table 2.

Efficacy

The best CR rate (primary endpoint) was 92% (95% CI 73–99%), after 6 cycles of treatment, increasing from 62.5% after 3 cycles. When measured by computed tomography (CT) only, rather than positron emission tomography (PET)-CT, best CR rate was 83% (95% CI, 65–93%). In all patients with baseline bone marrow involvement, CR was confirmed with repeated bone marrow biopsy at the end of treatment. Seven out of 9 patients who were in partial response (PR) after 3 cycles converted to CR after 6; the 2 patients who remained in PR after 6 cycles subsequently progressed. This led to a best overall response rate (ORR) of 100% (Fig. 1).

Response after 3, 6, and 13 cycles or end of treatment. All patients were evaluable for response. Complete response is depicted in green, partial response in blue, and progressive disease in orange. No patients experienced stable disease. CR complete response, PR partial response, PD progressive disease. Source data are provided as a Source Data file.

After a median follow-up of 43 months (95% confidence interval [CI] 41–47 months), 8 patients relapsed or progressed. At the most recent follow-up, median PFS was not reached, 2-year PFS rate was 79% (95% CI 65–97%) and 3-year PFS rate was 62% (95% CI 45–85%) (Fig. 2). Three patients relapsed or progressed with evidence of transformation into DLBCL. These included 2 patients who transformed at 5 and 7 months, while in PR (both with pre-treatment bulky disease and SUVmax > 17); and 1 who transformed at the end of treatment, after initial CR. Of 23 patients evaluable for early progression (1 patient died in CR before 24 months), CR30 rate was 65% and progression of disease within 24 months (POD24) rate was 17%.

Kaplan-Meier of progression-free survival and overall survival since initiation of treatment. Solid lines represent median survival. Dotted lines represent 95% confidence interval. Median follow-up of 43 months (95% CI 41–47 months). Source data are provided as a Source Data file.

At most recent follow-up, 3 patients have died. One patient died due to disease progression and transformation, and 2 due to COVID19 infection while in CR: both patients were unvaccinated, one died at 14 months and one at 34 months (while in CR from a subsequent line of therapy). Median OS has not been reached, 2-year OS rate was 92% (95% CI 81–100%), and 3-year OS rate was 87% (95% CI 75–100%) (Fig. 2).

Correlative analyses

After acalabrutinib monotherapy, the frequency of 38 types of circulating immune cells, measured by bulk RNA sequencing with deconvolution using the Kassandra algorithm, was unchanged, including classical and non-classical monocytes (Supplementary Fig. 2). We then evaluated gene expression signatures associated with monocyte biology and observed a significant increase in gene signatures of monocyte proliferation (E2F2, TYMS, CDK1, TK1, MKI67, KIF11, KIAA0101, PKMYT1, AURKA, AURKB, E2F1, MYBL2, BUB1, PLK1, CCNB1) (p = 0.011), tumor necrosis factor (TNF) response (CASP5, CXCL10, GBP1, MAPK14, STAT1, TNFAIP6, TNFSF10, TNFSF13B, CCL2)(p = 0.015), anti-viral (EPSTI1, HERC5, IFI27 IFI44, IFI44L, IFIT3, IFITM3, ISG15, LY6E, RSAD2) (p = 0.007) and anti-tumoral activity (IFI30, NPC2, C1QB, APOC1, S100A11, FCER1G) (p = 0.02) (Fig. 3). With the addition of R2, after a total of 6 cycles of treatment, a significant decrease in the frequency of circulating regulatory natural killer (NK) cells (p = 0.014), and an increase in the frequency of circulating CD4 + T cells (p = 0.014) and classical monocytes (p = 0.003) was observed (Supplementary Fig. 3).

Monocyte-related gene expression signatures (proliferation, tumor necrosis factor [TNF] response, antiviral activity, and anti-tumoral activity) were evaluated on peripheral blood samples collected before initiation of treatment (pre timepoint) and after acalabrutinib monotherapy (C2D1 timepoint). Enrichment scores were calculated using ssGSEA and subsequently median scaled for normalization. Each dot represents a blood sample from an individual patient (biological replicate). Box-and-whisker plots show the median (center line), 25th, and 75th percentile (lower and upper boundary), with 1.5 × inter-quartile range indicated by whiskers and outliers shown as individual data points. Statistical analysis was performed by two-sided paired Wilcoxon signed-rank test; no adjustment was made for multiple comparisons. TNF tumor necrosis factor, TAMM Tumor-associated macrophages and microglia, C2D1 cycle 2 day 1. Source data are provided as a Source Data file.

The median baseline ctDNA concentration, including all 24 patients, was 45.8 haploid genome equivalents (hGE)/mL (range, 4.8–2554.7 hGE/mL, n = 23). Baseline ctDNA concentration did not show any significant association with markers of tumor burden, including largest lymph node diameter (p = 0.26), Ann Arbor stage (p = 0.12), SUVmax (p = 0.09), FLIPI (p = 0.0523), FLIPI-2 (p = 0.26) or PRIMA-PI (p = 0.30) scores. Using median concentration of baseline ctDNA as cut-off, no significant difference in median relapse-free survival (RFS) was observed when comparing patients with baseline low vs high ctDNA (p = 0.48) (Fig. 4a). Peripheral blood samples for MRD assessment by PhasED-seq were available for 22 patients (20 in CR and 2 in PR). After 6 cycles of treatment, 16 of 22 (73%) patients achieved MRD eradication (Fig. 4b). None of the patients in PR was MRD-negative. At most recent follow-up, 5 (83%) of 6 patients with detectable MRD after 6 cycles have relapsed or progressed, while 1 patient with detectable MRD after 6 cycles remains in CR after 32 months. Thirteen (81%) of 16 patients without detectable MRD after 6 cycles remain in CR, while 3 have relapsed after 12, 28 and 29 months (p = 0.01) (Fig. 4c). On a landmark analysis at 6 cycles, median RFS was significantly longer for patients achieving MRD eradication after 6 cycles of treatment as compared to those with detectable MRD (not reached vs 22 months; p = 0.0059) (Fig. 4d)

a Relapse free survival of patients tratified by their pretreatment circulating tumoral DNA (ctDNA) level (above or below the median). The P value represents a two-sided log-rank test. b A waterfall plot shows the log-fold change in ctDNA from baseline until after the completion of 6 cycle of therapy. Patients with eventual relapsed disease are show in red, while patients without relapse are shown in blue. c A bar plot depicting the fraction of cases achieving ctDNA negative status by cycle 6, stratified by subsequent disease relapse. Fisher’s exact P = 0.011. d Relapse free survival of patients stratified by ctDNA status after 6 cycles of therapy (detectable versus undetectable ctDNA). One patient MRD positive, in whom MRD was collected before end of cycle 6, was not included in the analysis. The P value represents a two-sided log-rank test. Source data are provided as a Source Data file.

Discussion

The results of this phase 2 study indicate that the addition of acalabrutinib to R2 is a safe and effective frontline non-chemotherapy regimen for FL patients with an indication for treatment, resulting in high and early CR rates. With all the limitations of interstudy comparisons, patients included in this trial presented more adverse prognostic features compared to those treated with frontline R2 in phase II and phase III trials, including older age, larger lymph node diameter, and more elevated beta-2-microglobulin levels11,12,13, suggesting that aR2 could compare favorably to R2 3,14. Of interest, patients enrolled in this trial also had significantly elevated baseline SUVmax, which has previously been shown to associate with poor outcomes in patients treated with non-R-CHOP-based regimens, including R2 15. In addition, while FLIPI, FLIPI-2 and PRIMA-PI scores look comparable to benchmark trials, they have shown to be prognostic for patients treated with chemoimmunotherapy, but not for those treated with R2 16. These elements should be taken into consideration, while comparing long-term outcomes with aR2 to what observed with historical data with R2, including comparable POD24 rates and 2-year PFS rates.

The addition of less specific BTK inhibitors to R2 for the treatment of FL had previously been attempted with ibrutinib17,18. However, off-target interleukin-2 inducible T-cell kinase inhibition has the potential risk of increasing T-cell function, and hence lenalidomide-related toxicity19,20. To this regard, the combination of ibrutinib and R2 has shown to be poorly tolerated, mainly due to skin rash, resulting in significant dose reductions and delays, potentially impacting efficacy outcomes18,19. The latter could have also been due to off-target epidermal growth factor receptor inhibition and direct skin toxicity exerted by ibrutinib21. In contrast, in our trial, the addition of acalabrutinib to R2 did not seem to associate with increased toxicity, resulting in similar rates of AEs as compared to previous reports of R2 alone in FL patients3,14. It is important to notice that an increase in G3-4 neutropenia rates was observed with this combination, as compared to historical data with R2. Although this could be related to higher frequency in toxicity assessments as compared to prior trials, a lower dose of lenalidomide (15 mg instead of 20 mg) could be considered in older and frail patients, to minimize toxicity. While this trial took place during the peak of COVID-19 pandemia, mostly before the introduction of proper vaccination, given the known association between BTK inhibition and severe COVID-19 infections, patients should be vaccinated and promptly treated with anti-viral medications in case of infection, while undergoing this regimen. In addition, this combination was associated with a 17% rate of G3-4 LFT elevation: while the frequency of this specific AE is not clearly stated in RELEVANCE, both lenalidomide and acalabrutinib have been associated with hepatotoxicity, but no treatment discontinuation nor irreversible liver damage was observed in our study22,23. This same regimen has been explored in other B-cell non-Hodgkin lymphomas, but comparison in toxicity rates is limited by lymphoma subtype, line of therapy and duration of response24.

In addition to increasing toxicity, the use of less specific BTK inhibitors, such as ibrutinib, has also the potential disadvantage of decreasing lenalidomide-associated anti-tumoral activity, by inducing the polarization of tumor associated macrophages to a more pro-tumoral phenotype25,26,27. In contrast, in this study we demonstrate in FL patient-derived samples the positive impact of acalabrutinib on circulating monocytes, with significant increase in gene signatures associated with anti-tumoral activity. The survival and proliferation of FL cells is strongly dependent on myeloid cells, as their presence is necessary for their propagation in vitro28,29. To this regard, multiple studies have demonstrated the prognostic impact of macrophage content and polarization in FL patients, with different treatment strategies30,31,32,33. Additional studies are needed to verify whether agents able to target macrophage biology, including those blocking the interaction between CD47 and SIRPα, may increase the anti-tumoral activity of R2 and result in superior outcomes in FL patients34,35,36.

In this phase 2 study, in addition to elevated CR rates, early and high ctDNA-MRD eradication rates have also been observed with the use of frontline aR2. MRD eradication has shown to associate with survival outcomes in FL patients treated with different therapeutic strategies, including R237. However, the majority of MRD data available in FL are polymerase chain reaction (PCR)-based, an assay focused on cellular DNA and whose sensitivity is about 1:10,000 cells38,39,40,41,42,43,44,45. Next-generation sequencing, including ClonoSEQ and CAncer Personalized Profiling by deep Sequencing (CAPP-Seq), have addressed some of these challenges, the latter associating with a sensitivity in the parts per 10,000 range, but both are still limited by low negative predictive values45,46,47,48,49,50,51. As shown by a recently published randomized trial, MRD strategies based on cellular DNA, rather than ctDNA, are not effective in guiding FL therapy44. In this study we report for the first time ctDNA-MRD data in FL patients using PhasED-seq, an ultrasensitive assay yielding sensitivity in the parts per million, and demonstrate high and early MRD eradication rates, associating with significantly improved RFS, independently from baseline ctDNA, and better correlating with 2-year PFS than best CR rate. While larger datasets are needed to confirm our findings, our results suggest that PhasED-seq-based MRD assessment could be an effective early surrogate marker of RFS, and with longer follow-up it may challenge the ongoing paradigm of non-curability in FL, in addition to driving treatment duration.

We acknowledge several limitations of this study, including its small sample size, single center nature, relatively limited follow-up, and lack of tissue samples for correlative analyses. However, despite the high-risk patients being included in this study, high CR and MRD eradication rates were observed with this combination.

To further explore its activity and to investigate a shorter duration of treatment, the study has been expanded to include additional 26 FL patients. An exploratory cohort of 10 patients with marginal zone lymphoma has also been included. While randomized phase III trials investigate the efficacy of anti-CD3/CD20 bispecific antibodies in the frontline setting, and regimens combining other BTK inhibitors and anti-CD20 monoclonal antibodies show promising efficacy in the salvage setting, aR2 represents a safe and effective chemotherapy-free regimen. The high and early rates of MRD eradication and favorable biological effects on the circulating immune microenvironment achieved with this regimen justify its potential to be compared to chemoimmunotherapy, with similar treatment durations, in future randomized trials.

Methods

Ethics statement

The study was approved by the Institutional Review Board of The University of Texas MD Anderson Cancer Center (MDACC) and conducted in accordance with our institutional guidelines and the principles of the Declaration of Helsinki. All participants provided informed consent; no compensation was provided to participants.

Patients and study design

This is a single center, single arm, open label phase II study, conducted at MDACC from September 2020 to September 2021, with a data cut-off for reported follow-up of February 2025 (ClinicalTrials.gov; NCT04404088; pre-registration 07/16/2020; the original study, here presented, has been completed). Adult patients with previously untreated FL, grade 1 to 3A, with advanced Ann Arbor stage and indication for treatment, defined as meeting at least one of The Groupe d’ Etude des Lymphomes Folliculaires (GELF) criteria, were eligible for this study52. Patients with clinical or radiological suspicion for transformation underwent a tissue biopsy of the area with the highest standardized uptake volume (SUVmax), and those with histological evidence of transformation to diffuse large B-cell lymphoma (DLBCL) were excluded. Additional details about eligibility are provided in Supplementary Note 1. All patients received acalabrutinib lead-in at 100 mg orally (PO) twice a day for one 28-day cycle (cycle 1) and continued for total of 13 cycles; lenalidomide 20 mg PO daily on days 1–21, during cycle 2–13, and rituximab 375 mg/m2 intravenously (IV) weekly during cycle 2, and on day 1 of cycle 3–13. Prophylactic acetylsalicylic acid was used based on age and cardiovascular risk as per institutional guidelines.

End points and assessment

The primary endpoint was best CR rate measured by PET-CT, including CR achieved during treatment; CT-based responses were also prospectively collected. Secondary endpoints included safety, tolerability, and other measurements of efficacy, including ORR, CR at 30 months (CR30), PFS, POD24, RFS and overall survival (OS). Exploratory endpoints included impact of acalabrutinib as a single agent and of aR2 on circulating immune cells, and measurement of MRD by circulating tumor DNA (ctDNA-MRD).

The FL international prognostic index (FLIPI), FLIPI-2 and PRIMA-prognostic index (PI) scores were calculated as previously described11,12,13. Adverse events (AEs) were prospectively graded for 3 years from treatment initiation, until relapse, progression or initiation of subsequent line of therapy, according to the Common Toxicity Criteria for Adverse Events version 5. Response status was prospectively assessed by the Lugano 2014 classification, using PET-CT after 3 and 6 cycles, at the end of treatment, every 3 months for the first 2 years, every 6 months for the subsequent 3 years, and then yearly until progression53. In cases of complete metabolic response (CMR), use of CT with contrast was allowed instead of PET-CT during long-term monitoring. Bone marrow biopsy was performed for confirmation of CR for cases where it was positive for lymphoma involvement before initiation of treatment.

Bulk RNA sequencing and deconvolution

Bulk RNA sequencing was performed on peripheral blood samples collected at baseline, and on day 1 of cycles 2 and 7. Cellular deconvolution with the Kassandra algorithm was used to analyze the frequencies of different immune cell types in each blood sample, and immune-related gene expression signatures were evaluated54. RNA isolation was performed from patient buffy coat samples snap frozen in liquid nitrogen. The Maxwell RSC simplyRNA Cells Kit (Promega) was used to extract RNA, with several modifications to the protocol: For example, warm homogenization buffer containing 2-thioglyceral was added to the frozen buffy coat suspension immediately and incubation at 37 °C to completely thaw cryopreserved cells. These cells were all then extracted according to the manufacturer’s instructions, before loading onto the Maxwell RSC automated nucleic acid extraction platform.

RNAseq libraries were prepared with Illumina TruSeq® Stranded mRNA library prep (Poly-A mRNA; stranded). Libraries were sequenced on NovaSeq 6000 as Paired-End Reads (2 × 150) with targeted coverage of 50 mln reads per sample.

Raw FASTQ files quality was analyzed using FastQC (version 0.11.9), FastQ Screen (0.11.1) and MultiQC (version 1.14) software tools. The reference genomes utilized for the creation of BWA aligner indices (for FastQ Screen) included Homo sapiens (GRCh38), Mus musculus, Danio rerio, Drosophila melanogaster, Caenorhabditis elegans, Saccharomyces cerevisiae, Arabidopsis thaliana, Mycoplasma arginini, Escherichia virus phiX174, microbiome (downloaded from NIH Human Microbiome Project website), adapters (provided with FastQC v0.11.9), and UniVec (NCBI). All open-source blood RNA-seq type datasets went through the same quality metric procedure as well. High fraction of hemoglobin readcounts was detected during the quality assessment, so an additional re-sequencing run was performed to confirm that the reason for this was the type of the sample, and not the sequencing procedure.

Bulk RNA-seq fastq files were processed by Kallisto, version55. The Kallisto index file was downloaded from the Xena project, this index file was built based on GENCODE transcriptome annotation version 23 and the human reference genome GRCh38 with genes from the PAR locus removed (chrY:10,000-2,781,479 and chrY:56,887,902-57,217,415)56. In contrast to paired-end fastq files, single-end fastq files were processed by Kallisto with additional options -l 200 -s 15 in line with Xena. Calculated expression results were presented in the TPM format. All open-source blood RNA-seq type datasets obtained from GEO or ArrayExpress were processed the same way as internal RNA-seq data.

Hemoglobin genes were eliminated from further analysis. Cell deconvolution was performed with the Kassandra algorithm to estimate the percentages of 38 cell populations for every sample54. Changes in cell population proportions were compared between the Pre and C2D1, C2D1 and 6Mo, and Pre and 6Mo timepoints using a two-sided Wilcoxon Rank Sum test, which is appropriate for paired samples. Additionally, a comparison of subtype to parent population ratios was made for CD4 and CD8 T cells. P values were corrected for multiple testing with Benjamini-Hochberg procedure to control the false discovery rate.

For signature analysis, several sets of BostonGene signatures were employed. This included internal blood signatures (10 signatures) and myeloid-cell associated signatures (including non-blood-specific signatures) from the internal database (44 signatures). Both ranking calculation of enrichment scores and geometric mean scoring methods were utilized. The scores were tested according to the previously described scheme. Correlation coefficients of internal blood signature scores between the 1st run and re-seq samples were obtained, as well as correlation coefficients of deconvolution populations’ percentages. Open-source signatures were also tested between the Pre and C2D1 time points. New groups of correlated genes, referred to as “new signatures,” were derived from myeloid-related signatures, blood signatures (excluding signatures related to bacteria or virus response), and genes from deconvolution models (specifically Monocytes, Classical, and Non-classical subtypes). Only genes which 95% percentile of our internal blood RNA-seq cohort expression greater than 5 TPM were taken for further analysis. Groups were constructed using correlation coefficients with networkx.algorithms.find_cliques, which implements the Bron-Kerbosch algorithm. The groups were then tested between the Pre and C2D1 time points, and only those with a p < 0.05 (without correction) were subjected to enrichment analysis using EnrichR (gseapy package).

Differential gene expression analysis was performed using the EdgeR package. Differentially expressed genes were further examined to determine the cell populations in which they were predominantly expressed, and the results were presented as barplots. For genes that passed FDR threshold 0.05 expression boxplots were calculated for Pre and C2D1 time points.

Minimal residual disease evaluation

MRD was measured non-invasively by phased variant enrichment and detection sequencing (PhasED-seq, Foresight Diagnostics) on peripheral blood plasma57. Baseline plasma was utilized to identify phased variants (PVs), which were used to measure ctDNA-MRD levels at baseline and on day 1 of cycle 7. MRD positivity was determined by an analytical approach on a sample-specific basis, where the threshold is defined to allow a <1% false positive rate, using an assay with analytical sensitivity of <1 part per million58.

Library preparation, hybrid capture target enrichment, and sequencing by synthesis was performed at Foresight Diagnostics, using optimized workflows under standard operating procedures. Five to 120 ng of cfDNA or gDNA were used to construct sequencing libraries using KAPA HyperPrep kits (Roche Sequencing Solutions, Indianapolis, IN) on a custom workflow. Library DNA was enriched using a custom B-cell lymphoma probe panel (Integrated DNA Technologies, Inc., Coralville, IA), performed per the manufacturer’s instructions. After enrichment, libraries were sequenced using sequencing by synthesis on the Illumina NovaSeq 6000 and/or NovaSeq X Plus instrument (Illumina, Inc., San Diego, CA).

Sequence data were analyzed using in-house developed algorithms and pipelines. Briefly, raw sequencing data were de-multiplexed to FASTQ files for each sample using BCL Convert software (Illumina, Inc., San Diego, CA; versions 2.2.0 to 2.4.0). Low-quality sequencing reads and adapter read-throughs were removed using “fastp” (version 0.20.0). Sequencing reads were then aligned to the reference human genome (GRCh37) using the BWA-MEM aligner (version 2.2.1) to create one alignment file per sample, followed by proprietary methods to remove PCR and optical duplicates. The resulting sequence alignment files were used for the analysis of phased variants. MRD status was determined by the presence or absence of tumor-specific phased variants, meeting a threshold based on the likelihood of an incidental mutation overlapping with the tumor-specific phased variant list.

Statistics and reproducibility

The final analysis was conducted at the point when all patients could be evaluated for CR30. Redcap Version 11.4.4 was used to collect patient data. As in the RELEVANCE trial best CR rate included also unconfirmed CR, whereas all CRs were confirmed with a bone marrow biopsy in this study, to account for a potential 5-10% discrepancy between PET-CT and bone marrow biopsy (unconfirmed CR), a benchmark CR rate of 50% (rather than 59%) was utilized. With a sample size of 24 patients, the study had an 80% power to detect a difference in best CR rate between 50% for the standard of care (R2 alone) in the null hypothesis and 80% for the experimental regimen (aR2) in the alternative hypothesis, using an exact binomial test with a two-sided type I error rate of 0.05 (nQuery Advisor 7.0). A null hypothesis of 50% was based on CT-guided response criteria, as CMR for R2-treated patients in RELEVANCE is not known. Assuming a CMR rate of 70%, based on what observed with rituximab-based chemoimmunotherapy and published after study design59, a retrospective sample size calculation was performed to confirm adequate power: a sample size of 24 patients had an 83% power to detect a difference in best CR rate between 70% and 91%, using an exact binomial test with a one-sided type I error rate of 0.10. PFS was defined as the time from the start of therapy to progression of disease, death, or last follow-up (whichever occurred first). RFS was defined as time from the start of therapy to relapse or progression of disease, death due to disease or last follow-up. OS was defined as the time from the start of therapy to death or last follow-up. PFS, RFS and OS were calculated for all patients in the study and for subgroups of patients using Kaplan-Meier estimates and were compared between subgroups using the log-rank test. Landmark analysis was performed for RFS by MRD status at 6 cycles. The landmark time of 6 cycles was used. A p value of ≤0.05 (two-tailed) was considered statistically significant. Wilcoxon signed-rank test, with multiple comparisons corrected by the Benjamini-Hochberg procedure was utilized for comparisons of immune cells. Statistical software SAS 9.4 (SAS, Cary, NC) and TIBCO Spotfire S + 8.2 (TIBCO Software Inc., Palo Alto, CA) were used for all the analyses.

No data were excluded from the analyses. In this study, sex and gender were self-reported; research findings do not apply to one sex or gender.

Reporting summary

Further information on research design is available in the Nature Portfolio Reporting Summary linked to this article.

Data availability

The protocol of the study is available as Supplementary Note 1. The clinical and exploratory analysis data of this study underlying the results are available in the main manuscript, Supplementary Figs. and Source data file. The data reported in this article are not publicly available, as they are either confidential or proprietary. The authors will provide access to sequencing data and de-identified participant-level data underlying the data presented in this article to researchers who provide a methodologically sound proposal for academic purposes to interpret, verify and extend research in the article that does not violate privacy, data encumbrance, intellectual property or other legal, regulatory or contractual confidentiality obligations, beginning 12 months after article publication. Data provided will be subject to a data use agreement. Researchers should contact the corresponding author when applying for data access. Response to external data requests will be within a reasonable timeframe of a few weeks to months depending on the nature of the request. Use of data will be restricted to agreed purpose. Source data are provided within this manuscript.

References

Rummel, M. J. et al. Bendamustine plus rituximab versus CHOP plus rituximab as first-line treatment for patients with indolent and mantle-cell lymphomas: an open-label, multicentre, randomised, phase 3 non-inferiority trial. Lancet 381, 1203–1210 (2013).

Flinn, I. W. et al. First-line treatment of patients with indolent non-hodgkin lymphoma or mantle-cell lymphoma with bendamustine plus rituximab versus R-CHOP or R-CVP: results of the BRIGHT 5-year follow-up study. J. Clin. Oncol. 37, 984–991 (2019).

Morschhauser, F. et al. Rituximab plus lenalidomide in advanced untreated follicular lymphoma. N. Engl. J. Med. 379, 934–947 (2018).

Morschhauser, F. et al. Six-year results from RELEVANCE: lenalidomide plus rituximab (R(2)) versus rituximab-chemotherapy followed by rituximab maintenance in untreated advanced follicular lymphoma. J. Clin. Oncol. 40, 3239–3245 (2022).

Strati, P. et al. Long-term follow-up of lenalidomide and rituximab as initial treatment of follicular lymphoma. Blood 137, 1124–1129 (2021).

Marques-Piubelli, M. L. et al. SIRPalpha+ macrophages are increased in patients with FL who progress or relapse after frontline lenalidomide and rituximab. Blood Adv. 6, 3286–3293 (2022).

Linley, A. et al. Lectin binding to surface Ig variable regions provides a universal persistent activating signal for follicular lymphoma cells. Blood 126, 1902–1910 (2015).

Amin, R. et al. DC-SIGN-expressing macrophages trigger activation of mannosylated IgM B-cell receptor in follicular lymphoma. Blood 126, 1911–1920 (2015).

Golay, J., Ubiali, G. & Introna, M. The specific Bruton tyrosine kinase inhibitor acalabrutinib (ACP-196) shows favorable in vitro activity against chronic lymphocytic leukemia B cells with CD20 antibodies. Haematologica 102, e400–e403 (2017).

Strati, P. et al. Acalabrutinib plus rituximab with or without lenalidomide in patients with follicular lymphoma: a multipart, open-label, phase 1b trial. Blood 140, 3606–3608 (2022).

Solal-Celigny, P. et al. Follicular lymphoma international prognostic index. Blood 104, 1258–1265 (2004).

Federico, M. et al. Follicular lymphoma international prognostic index 2: a new prognostic index for follicular lymphoma developed by the international follicular lymphoma prognostic factor project. J. Clin. Oncol. 27, 4555–4562 (2009).

Bachy, E. et al. A simplified scoring system in de novo follicular lymphoma treated initially with immunochemotherapy. Blood 132, 49–58 (2018).

Fowler, N. H. et al. Safety and activity of lenalidomide and rituximab in untreated indolent lymphoma: an open-label, phase 2 trial. Lancet Oncol. 15, 1311–1318 (2014).

Strati, P. et al. Pre-treatment maximum standardized uptake value predicts outcome after frontline therapy in patients with advanced stage follicular lymphoma. Haematologica 105, 1907–1913 (2020).

Julia, E. et al. Validation of the PRIMA-prognostic index for patients treated with rituximab plus chemotherapy and refinement of prognostic parameters for patients on rituximab plus lenalidomide in the phase III relevance trial. Blood 134, 1524 (2019).

Ujjani, C. et al. A phase 1 study of lenalidomide and ibrutinib in combination with rituximab in relapsed and refractory CLL. Blood Adv. 2, 762–768 (2018).

Gordon, M. J. et al. Safety and efficacy of ibrutinib in combination with rituximab and lenalidomide in previously untreated follicular and marginal zone lymphoma: an open label, phase 2 study. Cancer 130, 876–885 (2024).

Long, M. et al. Ibrutinib treatment improves T cell number and function in CLL patients. J. Clin. Invest 127, 3052–3064 (2017).

Kondo, K. et al. Ibrutinib modulates the immunosuppressive CLL microenvironment through STAT3-mediated suppression of regulatory B-cell function and inhibition of the PD-1/PD-L1 pathway. Leukemia 32, 960–970 (2018).

Stephens, D. M. & Byrd, J. C. How I manage ibrutinib intolerance and complications in patients with chronic lymphocytic leukemia. Blood 133, 1298–1307 (2019).

Nojkov, B., Signori, C., Konda, A. & Fontana, R. J. Lenalidomide-associated hepatotoxicity-a case report and literature review. Anticancer Res. 32, 4117–4119 (2012).

Shaker, M. E. et al. Inhibition of Bruton tyrosine kinase by acalabrutinib dampens lipopolysaccharide/galactosamine-induced hepatic damage. Biomed. Pharmacother. 131, 110736 (2020).

Park, C. et al. Combination of acalabrutinib with lenalidomide and rituximab in relapsed/refractory aggressive B-cell non-Hodgkin lymphoma: a single-arm phase II trial. Nat. Commun. 15, 2776 (2024).

Fiorcari, S. et al. Ibrutinib modifies the function of monocyte/macrophage population in chronic lymphocytic leukemia. Oncotarget 7, 65968–65981 (2016).

Colado, A. et al. Effect of the BTK inhibitor ibrutinib on macrophage- and gammadelta T cell-mediated response against Mycobacterium tuberculosis. Blood Cancer J. 8, 100 (2018).

Strati, P. et al. Achieving complete remission in CLL patients treated with ibrutinib: clinical significance and predictive factors. Blood 135, 510–513 (2020).

Umetsu, D. T., Esserman, L., Donlon, T. A., DeKruyff, R. H. & Levy, R. Induction of proliferation of human follicular (B type) lymphoma cells by cognate interaction with CD4+ T cell clones. J. Immunol. 144, 2550–2557 (1990).

Johnson, P. W. et al. Isolated follicular lymphoma cells are resistant to apoptosis and can be grown in vitro in the CD40/stromal cell system. Blood 82, 1848–1857 (1993).

Pollard, J. W. Tumour-educated macrophages promote tumour progression and metastasis. Nat. Rev. Cancer 4, 71–78 (2004).

Hanada, T. et al. Prognostic value of tumor-associated macrophage count in human bladder cancer. Int J. Urol. 7, 263–269 (2000).

Kim, Y. J. et al. Correlation between tumor-associated macrophage and immune checkpoint molecule expression and its prognostic significance in cutaneous melanoma. J. Clin. Med. 9, 2500 (2020).

Gouni, S., Marques-Piubelli, M. L. & Strati, P. Follicular lymphoma and macrophages: impact of approved and novel therapies. Blood Adv. 5, 4303–4312 (2021).

Advani, R. et al. CD47 Blockade by Hu5F9-G4 and rituximab in non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma. N. Engl. J. Med. 379, 1711–1721 (2018).

Ansell, S. M. et al. Phase I study of the CD47 blocker TTI-621 in patients with relapsed or refractory hematologic malignancies. Clin. Cancer Res. 27, 2190–2199 (2021).

Kim, T. M. et al. ALX148, a CD47 Blocker, in combination with rituximab in patients with non-Hodgkin. Lymphoma Blood 136, 13–14 (2020).

Delfau-Larue, M. H. et al. Lenalidomide/rituximab induces high molecular response in untreated follicular lymphoma: LYSA ancillary RELEVANCE study. Blood Adv. 4, 3217–3223 (2020).

Rambaldi, A. et al. Quantitative PCR of bone marrow BCL2/IgH+ cells at diagnosis predicts treatment response and long-term outcome in follicular non-Hodgkin lymphoma. Blood 105, 3428–3433 (2005).

Ladetto, M. et al. Prospective, multicenter randomized GITMO/IIL trial comparing intensive (R-HDS) versus conventional (CHOP-R) chemoimmunotherapy in high-risk follicular lymphoma at diagnosis: the superior disease control of R-HDS does not translate into an overall survival advantage. Blood 111, 4004–4013 (2008).

Galimberti, S. et al. Minimal residual disease after conventional treatment significantly impacts on progression-free survival of patients with follicular lymphoma: the FIL FOLL05 trial. Clin. Cancer Res 20, 6398–6405 (2014).

Ladetto, M. et al. Persistence of minimal residual disease in bone marrow predicts outcome in follicular lymphomas treated with a rituximab-intensive program. Blood 122, 3759–3766 (2013).

Pott, C. et al. Minimal residual disease status predicts outcome in patients with previously untreated follicular lymphoma: a prospective analysis of the phase III GALLIUM study. J. Clin. Oncol. 42, 550–561 (2024).

Pulsoni, A. et al. Minimal residual disease monitoring in early stage follicular lymphoma can predict prognosis and drive treatment with rituximab after radiotherapy. Br. J. Haematol. 188, 249–258 (2020).

Luminari, S. et al. Response-adapted postinduction strategy in patients with advanced-stage follicular lymphoma: the FOLL12 study. J. Clin. Oncol. 40, 729–739 (2022).

Sarkozy, C. et al. The prognostic value of clonal heterogeneity and quantitative assessment of plasma circulating clonal IG-VDJ sequences at diagnosis in patients with follicular lymphoma. Oncotarget 8, 8765–8774 (2017).

Distler, A. et al. A prospective study of clonal evolution in follicular lymphoma: circulating tumor DNA correlates with overall tumor burden and fluctuates over time without therapy. Blood 138, 1328 (2021).

Jimenez-Ubieto, A. et al. Real-life disease monitoring in follicular lymphoma patients using liquid biopsy ultra-deep sequencing and PET/CT. Leukemia 37, 659–669 (2023).

Fernandez-Miranda, I. et al. Monitoring of circulating tumor DNA predicts response to treatment and early progression in follicular lymphoma: results of a prospective pilot study. Clin. Cancer Res 29, 209–220 (2023).

Hatipoglu, T. et al. Plasma concentrations and cancer-associated mutations in cell-free circulating DNA of treatment-naive follicular lymphoma for improved non-invasive diagnosis and prognosis. Front. Oncol. 12, 870487 (2022).

Scherer, F. et al. Distinct biological subtypes and patterns of genome evolution in lymphoma revealed by circulating tumor DNA. Sci. Transl. Med. 8, 364ra155 (2016).

Schroers-Martin, J. G. et al. Tracing founder mutations in circulating and tissue-resident follicular lymphoma precursors. Cancer Discov. 13, 1310–1323 (2023).

Brice, P. et al. Comparison in low-tumor-burden follicular lymphomas between an initial no-treatment policy, prednimustine, or interferon alfa: a randomized study from the Groupe d’Etude des Lymphomes Folliculaires. Groupe d’Etude des Lymphomes de l’Adulte. J. Clin. Oncol. 15, 1110–1117 (1997).

Cheson, B. D. et al. Recommendations for initial evaluation, staging, and response assessment of Hodgkin and non-Hodgkin lymphoma: the Lugano classification. J. Clin. Oncol. 32, 3059–3068 (2014).

Zaitsev, A. et al. Precise reconstruction of the TME using bulk RNA-seq and a machine learning algorithm trained on artificial transcriptomes. Cancer Cell 40, 879–894 e816 (2022).

Bray, N. L., Pimentel, H., Melsted, P. & Pachter, L. Near-optimal probabilistic RNA-seq quantification. Nat. Biotechnol. 34, 525–527 (2016).

Vivian, J. et al. Toil enables reproducible, open source, big biomedical data analyses. Nat. Biotechnol. 35, 314–316 (2017).

Kurtz, D. M. et al. Enhanced detection of minimal residual disease by targeted sequencing of phased variants in circulating tumor DNA. Nat. Biotechnol. 39, 1537–1547 (2021).

Klimova, N., Close, S., Kurtz, D. M., Hockett, R. D. & Hyland, L. Analytical validation of a circulating tumor DNA assay using PhasED-Seq technology for detecting residual disease in B-cell malignancies. Oncotarget 16, 329–336 (2025).

Trotman, J. et al. Prognostic value of end-of-induction PET response after first-line immunochemotherapy for follicular lymphoma (GALLIUM): secondary analysis of a randomised, phase 3 trial. Lancet Oncol. 19, 1530–1542 (2018).

Acknowledgements

This research is supported in part by Astrazeneca and by The University of Texas MD Anderson Cancer Center Support Grant from National Institutes of Health (P30 CA016672). Astrazeneca had no role in the study design, data collection and analysis. The MD Anderson Lymphoma Tissue Bank was utilized in this study and is supported by KW Cares. P.S.’s salary is supported by the Leukemia Lymphoma Society Scholar in Clinical Research Career Development Program, the Kite Gilead Scholar in Clinical Research Award, and the Sabin Family Fellowship Award. We acknowledge the technical support provided by the following BostonGene employees: Polina Turova, Aleksandr Zaitsev, and Anastasiya Terenteva.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

P.S. and S.S.N. designed the study, analyzed the data, and wrote the paper. LF provided statistical support and coauthored the paper; P.S., J.R.W., R.N., L.E.F., M.A.R., D.C., L.M., M.G., C.R.F., and S.S.N. provided clinical care to patients and coauthored the paper; M.R. collected clinical data and coauthored the paper. J.H., I.W., A.B., A.R., D.K., S.K.A., and A.A.A. performed correlative analyses.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

P.S. is a consultant for Roche-Genentech, Abbvie-Genmab, Ipsen, Kite/Gilead, Hutchison MediPharma, AstraZeneca-Acerta, ADC Therapeutics, Sobi, and TG Therapeutics; he has received research funds from Sobi, AstraZeneca-Acerta, ALX Oncology, and ADC Therapeutics. S.S.N. received research support from Kite/Gilead, BMS, Allogene, Precision Biosciences, Adicet Bio, and Sana Biotechnology; served as Advisory Board Member/Consultant for Kite/Gilead, Merck, Sellas Life Sciences, Athenex, Allogene, Incyte, Adicet Bio, BMS, Bluebird Bio, Fosun Kite, Sana Biotechnology, Caribou, Astellas Pharma, Morphosys, Janssen, Chimagen, ImmunoACT, Orna Therapeutics, Takeda, and Synthekine; has stock options from Longbow Immunotherapy, Inc; and has intellectual property related to cell therapy. S.K.A. reports consultancy for Foresight Diagnostics. The remaining authors declare no competing interests.

Peer review

Peer review information

Nature Communications thanks the anonymous, reviewer(s) for their contribution to the peer review of this work. A peer review file is available.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Source data

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Strati, P., Feng, L., Westin, J.R. et al. Frontline acalabrutinib, lenalidomide and rituximab for advanced stage follicular lymphoma with high tumor burden: phase II trial. Nat Commun 16, 7300 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-025-62509-z

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-025-62509-z