Abstract

Lettuce (Lactuca sativa L.) is among the most widely cultivated and consumed vegetables globally, valued for its phytonutrients beneficial for human health. Here, we report the high-quality reference super-pangenome for the Lactuca genus by integrating 12 chromosome-scale genomes from representative cultivated lettuce morphotypes, landrace, and wild relatives, and investigate lettuce genome evolution and domestication. These assemblies exhibit diverse genome sizes ranging from 2.1 Gb to 5.5 Gb with abundant repetitive sequences, and expansion of repetitive sequences, associated with low DNA methylation levels, likely contributes to the genome size variations. Furthermore, by constructing a graph-based lettuce pangenome reference, we explore the landscape, genomic, and epigenetic features of structural variations, and reveal their contributions to gene expression and domestication. We also identify copy number variations in FLOWERING LOCUS C in association with delayed flowering in cultivated lettuce. Overall, this comprehensive Lactuca super-pangenome assembly will expedite functional genomics studies and breeding efforts of this globally important crop.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The genus Lactuca belongs to the Asteraceae family (also known as the Compositae or daisy family), which is the largest family of flowering plants. As a key representative of this genus, cultivated lettuce (Lactuca sativa L.) is one of the most widely grown and consumed vegetables worldwide (https://www.fao.org/), constituting a significant natural source of phytonutrients beneficial for human health1. Cultivated lettuce is believed to have originated from a single domestication event involving its wild progenitor, prickly lettuce (L. serriola), near the Caucasus in the Middle East at approximately 4000 BC2,3. The initial domestication and subsequent diversification lead to modern cultivated lettuce, exhibiting a variety of morphological differences that can be grouped into seven morphotypes: crisp, butterhead, cutting (also known as looseleaf), cos (also known as romaine), Latin, stem (also known as stalk), and oilseed lettuce2,3,4. This domestication and diversification also likely involve genomic introgressions from wild relative species of lettuce, like L. serriola, L. virosa, and L. saligna3,5,6,7. Moreover, these three wild relatives are compatible with cultivated lettuce to varying degrees, making them valuable sources of novel traits for lettuce breeding4,5,8.

Recent genomic studies have shed light on the abundant genetic variations during lettuce domestication3; however, large-scale variations, like structural variations (SVs), and their contribution to shaping domestication traits remain largely unexplored. Fully grasping the genetic variations driving lettuce evolution requires a thorough analysis of its pan-genome, as relying on a single reference genome may miss substantial genetic information9,10,11,12,13. So far, the genomes of crisp, stem, and cutting lettuce, as well as the wild relatives L. virosa and L. saligna, have been sequenced using different approaches, with varying levels of continuity and completeness14,15,16,17,18,19. The differing qualities of Lactuca genomes are possibly attributed to their highly complex genomes, characterized by large genome sizes and abundant repeat sequences. Thus, these genomes are insufficient to obtain a comprehensive understanding of the genome evolution and domestication of lettuce.

Genome evolution is profoundly influenced by DNA methylation at the C-5 position of cytosine20,21. DNA methylation is not only present on repeat sequences to inhibit transposon activity and maintain genome stability, but is also associated to SVs18,22,23,24,25,26. In plants, DNA methylation occurs in CG, CHG, and CHH (H = A, T, or C) contexts, with CG and CHG methylation maintained by METHYLTRANSFERASE1 and CHROMOMETHYLASE3 (CMT3), respectively, and CHH methylation established by DOMAINS REARRANGED METHYLASE2 or CMT226,27,28. In addition, DNA methylation is also associated with the loss of gene copies during lettuce diploidization18, a process that follows a whole-genome triplication (WGT) through a paleopolyploidization event shared by subfamilies near the crown node of the Asteraceae family14,15,29. Although population epigenetics has revealed DNA methylation variations during lettuce domestication7, the roles of DNA methylation in the generation of SVs and diploidization during lettuce genome evolution remain largely unknown.

Herein, we de novo assemble 10 high-quality chromosome-scale genomes for five cultivated lettuce (L. sativa) morphotypes (butterhead, cutting, cos, Latin, and oilseed lettuce), one landrace, and four close wild relatives (L. serriola, L. saligna, L. virosa, and L. indica). By integrating these genomes with the published genomes of the other two lettuce morphotypes, crisp and stem lettuce14,15, we construct a super-pangenome and a graph-based reference genome and detect SVs. We further explore the landscape, genomic and epigenetic features of SVs and core WGT genes after diploidization in lettuce genome evolution. Furthermore, we identify abundant SVs related to domestication. The pangenome offers unique insights into genome evolution and provides valuable genomic resources for lettuce research and improvement.

Results

High-quality genome assembly of representative lettuce morphotypes and wild relatives

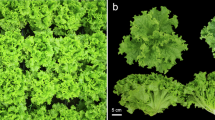

Lettuce is a globally cultivated cash vegetable crop with steadily increasing global production since the 1960s, reaching over 22 million tons in 2020 (Fig. 1a, b). To represent the diversity of cultivated and wild lettuce species, we selected five cultivated morphotypes (butterhead, cutting, cos, Latin, and oilseed lettuce) from the world’s most productive regions, one landrace, and four wild relatives (L. serriola from near the core domestication region, L. saligna, L. virosa, and L. indica) for de novo genome assembly (Fig. 1b, c and Table 1).

Total worldwide production of lettuce from 1961 to 2020 (a) and its geographic distribution in 2020 (b). The data of worldwide production of lettuce were obtained from Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations (https://www.fao.org/). The map was created using the map data function in ggplot2 of R language. c Seedling morphologies and the origins of representative accessions used for genome assembly to construct the Lactuca super-pangenome. The origins of crisp and stem lettuce with previously reported genome assemblies14,15 are also indicated. Their germplasm IDs, types, and species names were provided above. Scale bar, 15 cm. d Genome-wide syntenic relationships across 12 Lactuca genomes. The orange, blue, and gray linking blocks indicate inversions, translocations, and syntenic regions, respectively. Chr, chromosome. e Nucleotide alignment dot plots comparing the collinearities and similarities between the genomes of butterhead lettuce (ButterG25V01) and crisp lettuce (CrispV11), and between butterhead lettuce and L. indica (LIndG103V01). MPI indicates mean percent identify with a minimum nucleotide alignment length = 1 kb. Source data are provided as a Source Data file.

We assembled the genomes of these ten accessions by integrating PacBio HiFi long-reads and high-throughput chromosome conformation capture (Hi-C) data (Supplementary Data 1). Among these assemblies, the five cultivated morphotypes, landrace, and the wild progenitor L. serriola have similar genome sizes of approximately 2.6 Gb (Table 1), consistent with previous reports for other morphotypes14,15. Our assemblies have a long contig N50 (20 Mb on average) (Table 1), which is 4- and 1.6-fold longer than the previously published genomes of stem lettuce15 (StemV01 with a contig N50 of 4.98 Mb) and crisp lettuce14 (CrispV11 with a contig N50 of 12.5 Mb; GCF_002870075.4), respectively. Surprisingly, the wild relatives exhibit divergent genome sizes: L. saligna with the smallest genome of 2.1 Gb, L. virosa with 3.3 Gb, and L. indica with the largest genome of 5.5 Gb (Table 1). Although our assembled genome lengths of L. saligna and L. virosa are similar to those of previous published genomes16,17, their contig N50 values are significantly longer, at 56.7 Mb and 47.5 Mb (Table 1), respectively, compared to the previously reported values of 0.09 Mb and 0.13 Mb. On average, 99.6% of contig sequences were anchored to the nine pseudochromosomes of the Lactuca genus (Table 1). The mean LAI score for LTR identity on these assembled reference genomes is 19.5 (Table 1). In addition, the completeness of these genome assemblies was estimated to be an average of 96.5%, as assessed using Benchmarking Universal Single-Copy Orthologs (BUSCO) (Table 1 and Supplementary Data 1).

Wild relatives displayed low genomic collinearity and synteny within each other, with long inversions observed particularly in chromosomes 1, 3, and 9 (Fig. 1d). The highest quality assembly of butterhead lettuce (Table 1) showed higher collinearity with CrispV11 (Fig. 1e) and other lettuce morphotypes (Supplementary Fig. 1), but much lower collinearity with wild relatives (Fig. 1d and Supplementary Fig. 1), especially L. indica (Fig. 1e), which is consistent with evolutionary patterns3,7.

Super-pangenome of lettuce

We annotated 34,090–40,618 high-confidence gene models with 56,908–63,000 transcripts in the Lactuca genus by integrating RNA sequencing (RNA-seq)-based transcriptomics data, ab initio prediction, and homology-based prediction (Supplementary Fig. 2a and Supplementary Data 2). Analysis of gene family contraction and expansion revealed uneven rates of gene retention and loss among these species examined. Unlike the abundant gene family retention and loss in other species, the Lactuca genus, excluding stem lettuce, experienced approximately 2000 gene family retention and losses (Fig. 2a and Supplementary Fig. 2b). Interestingly, gene family losses were significantly higher than gene family retention among the Lactuca genus.

a Gene family contraction and expansion in the Lactuca genome. The phylogenetic relationships and estimated divergence times are shown on the left, while the numbers representing gene family contraction (blue color) and expansion (right color) are shown on the right. MYA, million years ago. b Variation of gene family sizes in the pan-genome and core genome as additional Lactuca genomes are incorporated into the clustering. 12 genomes were analyzed. In boxplots, the 25% and 75% quartiles are shown as lower and upper edges of boxes, respectively, and central lines denote the median. The whiskers extend to 1.5× the interquartile range. c Compositions of the pangenome and core genome. The histogram shows the number and frequency of gene families among the 12 Lactuca genomes, and the pie chart shows the proportion of gene family marked by composition in the pangenome. The numbers of gene family for testing 1–12 genomes are 1126, 3833, 2118, 1533, 1199, 1116, 1177, 1237, 1195, 1754, 4224, and 9243). GO analysis of the domestication-retention (d) and domestication-loss (e) core genes. Source data are provided as a Source Data file.

Next, we integrated our assembled 10 genomes with the 2 published lettuce genomes14,15 to generate the lettuce super-pangenome assembly. We defined 37,456 pangene families by clustering protein-coding genes of these 12 genomes (Fig. 2b). This pangene family number was lower than those of the Solanum genus11, Oryza genus9, and soybean10. The number of gene families increased rapidly with the inclusion of more genomes (Fig. 2b), indicating that the 12 Lactuca genomes are diverse and that a single reference genome is unable to capture the full genetic diversity of lettuce. Only 42.0% of gene families were conserved among the 12 Lactuca genomes (core gene families), 12.9% were soft core genes (present in 10 or 11 accessions), 43.4% were dispensable gene families (present in 2 to 9 accessions), and 3% were accession-specific pangene families (Fig. 2c). This super-pangenome dataset serves as a basis for exploring and utilizing genes or alleles in wild lettuce species.

A total of 1.4% of pangene families were cultivated lettuce-specific retention (158) or losses (491), where gene families were retained or lost in main cultivated lettuce morphotypes (butterhead, cutting, cos, Latin, stem and crisp lettuce) compared to their wild ancestor (L. serriola). These pangene families were thus termed domestication-retention or domestication-loss core genes. Gene ontology (GO) enrichment analysis showed that domestication-retention core genes were enriched in biological processes such as DNA-templated DNA replication, response to biotic stimulus, and nucleic acid phosphodiester bond hydrolysis process (Fig. 2d). Domestication-loss core genes were overrepresented in processes such as establishment of protein localization to organelle, response to temperature stimulus, and protein localization to organelle (Fig. 2e).

Similar diploidization effect across the Lactuca genus

These assemblies of the Lactuca genus have large genome sizes (Table 1), yet all of them are diploid30, implying that they may have experienced paleopolyploidization. Indeed, recent analyses suggest that lettuce underwent paleopolyploidization, a process shared by subfamilies near the crown node of the Asteraceae family14,15,29,31,32. During diploidization, the lettuce genome rapidly lost many gene copies resulting from WGT, a phenomenon also observed in maize33. To examine the features of diploidization following WGT in the Lactuca genus, we performed a comprehensive genomic and epigenomic analysis of duplicated genes. Among the total annotated genes for each genome, the average composition included 34.8% single-copy genes (singleton), 14.8% WGT genes, and 50.4% small-scale duplicated genes that were further categorized as 10.8% tandem, 6.5% proximal, and 33.1% dispersed duplicated genes (Fig. 3a), with the exception of stem lettuce which had over 50% single-copy genes (Supplementary Fig. 2c). In addition, similar percentages of each duplicated gene class in core genes (conserved in all Lactuca genomes excluding stem lettuce) were observed between cultivated lettuce and wild relatives (Fig. 3b), suggesting a similar degree of diploidization across the Lactuca genus. Strikingly, the percentage of WGT genes in core genes was much higher than in total genes (Fig. 3c), indicating a potential role of these core WGT genes in lettuce diploidization. These results suggest that similarly strong diploidization has occurred across the Lactuca genus.

Percentage of WGT, small-scale duplicated (tandem, proximal, and dispersed), and single-copy (singleton) genes in total annotated genes (a) and core annotated genes (b) across the Lactuca genus. c Average percentage of WGT, small-scale duplicated, and single-copy genes in core annotated genes. Data are presented as mean ± s.d. (n = 11). d GO enrichment of core WGT genes. The plot shows the 10 top-scoring biological processes. e Expression levels of WGT, small-scale duplicated, and single-copy genes in leaves. The numbers of Singleton, Dispersed, Proximal, Tandem, and WGT genes are 13,290, 11,682, 2459, 3713, and 5795. In boxplots, the 25% and 75% quartiles are shown as lower and upper edges of boxes, respectively, and central lines denote the median. The whiskers extend to 1.5× the interquartile range. The asterisk indicates a significant difference (**P < 0.01; two-sided Wilcoxon signed-rank test). f Average CG methylation levels around WGT, small-scale duplicated, and single-copy genes. TSS, transcription start site; TTS, transcription termination site. The asterisk indicates a significance difference between DNA methylation levels of WGT and singleton genes (**P < 0.01, two-sided Wilcoxon signed-rank test). The exact P values (e, f) are provided in Supplementary Data 4. Source data are provided as a Source Data file.

GO analysis revealed that the core WGT genes were enriched in important biological processes, including shoot system development, RNA biosynthetic process, and regulation of cellular biosynthetic process (Fig. 3d). Interestingly, we found that these core WGT genes exhibited significantly higher expression levels than small-scale duplicated genes and single-copy genes (Fig. 3e and Supplementary Fig. 2c). We also observed low CG DNA methylation around genic regions, particularly near transcriptional start sites (TSSs), in WGT genes compared to single-copy genes (Fig. 3f), implying that genes with low CG methylation levels are more likely to be retained during the diploidization process in the Lactuca genus.

Transposon expansion contributing to genomic size

A range of 84.5–89.1% of our lettuce genome assemblies were annotated as repetitive elements, with long terminal repeat (LTR) retrotransposons (Gypsy, Copia, and other LTRs) being the most prevalent, accounting for an average of 82.6% of the total repetitive sequences (Fig. 4a and Supplementary Table 1). A small proportion of repetitive elements were annotated as DNA transposable elements (TEs), including hobo-Activator and Tourist/Harbinger transposable repeats, which made up an average of approximately 2.1% of these genomes (Fig. 4a and Supplementary Table 1). The genome of L. saligna, which has the smallest genome size, contained the lowest proportion of repetitive sequence at 84.5%, whereas the genome of L. indica, with the largest genome size, had the highest proportion at 89.1% (Fig. 4a and Supplementary Table 1). To investigate the contribution of LTRs to genomic size variations during Lactuca evolution, we identified intact LTRs and found that L. saligna had the lowest LTR intact rate at 17.9%, while L. indica had the highest at 28.2% (Fig. 4b). Most intact LTRs were approximately 8.0 kb in length, but those in L. indica were shorter compared to the other Lactuca genomes, with a particularly high abundance of intact LTRs around 6.3 kb in length (Fig. 4c). Interestingly, most intact LTRs of both of Copia and Gypsy in L. indica had much younger insertion times compared to the other Lactuca genomes, with particularly notable peaks indicating multiple rounds of Copia expansion (Fig. 4d; Supplementary Fig. 3a). Together, these results indicate that recent LTR expansion, with many rounds of insertion, contributes to the huge genomic size of L. indica.

a Total lengths and compositions of repetitive sequences in the Lactuca genome assemblies. The repetitive sequences are categorized into RNA-TEs including LTR retrotransposons (Copia, Gypsy, and other LTRs) and other RNA TEs, as well as DNA TEs, unclassified TEs, and other repeats. Identification of intact LTRs (b) and their length (c). The numbers of LTRs are 130,511, 54,480, 29,730, 39,350, 37,679, 37,693, 37,179, 37,751, 37,985, and 37,793. In boxplots, the 25% and 75% quartiles are shown as lower and upper edges of boxes, respectively, and central lines denote the median. The whiskers extend to 1.5× the interquartile range. d The insertion time of Copia- and Gypsy-type intact LTRs. The numbers of Copia are 8017, 12,724, 11,310, 15,516, 13,505, 13,480, 13,283, 13,541, 13,612, and 13,599, while the numbers of Gypsy are 109,229, 21,016, 11,199, 14,465, 14,606, 14,765, 14,588, 14,723, 14,717, and 14,755. In boxplots, the 25% and 75% quartiles are shown as lower and upper edges of boxes, respectively, and central lines denote the median. The whiskers extend to 1.5× the interquartile range. e Average DNA methylation levels of CG (left), CHG (middle), and CHH (right) in wild relatives and cultivated lettuce. Data are presented as mean ± s.d. (n = 2 biological replicates). Different letters on the boxes indicate significant differences (one-way ANOVA test) in a pairwise comparison. f DNA methylation levels of CG (left), CHG (middle), and CHH (right) across different genomic features including gene regions, Copia, and Gypsy. Asterisks indicate significant differences (**P < 0.01, two-sided Wilcoxon signed-rank test) between L. indica and butterhead lettuce. The lines representing different accessions are color-coded as shown in e. The exact P values (e, f) are provided in Supplementary Data 4. g Phylogenetic tree based on protein sequences encoded by CMT2 genes. These include CMT2 genes in butterhead lettuce (G25Chr7g26322, G25Chr7g27234, G25Chr3g10111, and G25Chr5g19182), landrace lettuce (G116Chr3g8963 and G116Chr5g19145), wild lettuce L. serriola (G126Chr3g8903, G126Chr5g18666), L. saligna (G105Chr3g7480 and G105Chr5g16227), L. virosa (G108Chr3g9323 and G108Chr5g20233), L. indica (G103Chr3g9149 and G103Chr6g23952), Arabidopsis (AT4G19020), and rice (LOC_Os05g13780 and LOC_Os03g12570). h Expression changes of CMT2 in wild relatives compared to the butterhead cultivated lettuce. Source data are provided as a Source Data file.

DNA methylation plays an essential role in silencing transposable elements26. We then investigated DNA methylation variations during Lactuca evolution and found that the genome of L. indica exhibited minor changes in CG and CHG methylation, but an obvious decrease in CHH methylation levels compared to butterhead lettuce (Fig. 4e), which is consistent with our previous observations7. L. indica showed lower CHH methylation levels in gene-flanking regions and transposable elements compared to butterhead lettuce, with the lowest methylation levels observed in LTRs (Fig. 4f and Supplementary Fig. 3b–d). Since CHH methylation is de novo established by DRM2 or CMT226, we identified CMT2 homologs in Lactuca genus. At least two CMT2 homologous genes were identified among the Lactuca assemblies (Fig. 4g and Supplementary Fig. 3e). L. indica had two copies of CMT2 and both exhibited lower expression level compared to butterhead lettuce (Fig. 4h). This result suggests transcription levels of CMT2s play a role in recent LTR expansion and increased genomic size of L. indica.

Structural variants driven by transposons

To detect SVs across the Lactuca genus, we leveraged these 12 high-quality genome assemblies and performed pair-wise genome alignment with butterhead lettuce genome (ButterG25V01, the highest quality genome among the cultivated lettuce morphotypes). Among the cultivated lettuce morphotypes, an average of 87,625 SVs were identified in genomes of cutting lettuce (97,327; CutG36V01), cos lettuce (86,995; CosG53V01), Latin lettuce (72,433; LatinG79V01) and crisp lettuce (93,744; CrispV11), whereas higher numbers of SVs were found in oilseed lettuce (123,841 SVs; OilG67V01) and stem lettuce (192,230 SVs; StemV01) (Fig. 5a and Supplementary Fig. 4a). In L. serriola, 131,682 SVs were identified in the landrace genome (LOilG116V01) and 276,594 SVs in the wild progenitor (LSerG126V01) (Fig. 5a and Supplementary Fig. 4a). In wild relatives, 112,055 SVs were found in L. indica (LIndG103V01), 244,996 in L. virosa (LVirG108V01), and 294,989 in L. saligna (LSalG105V01) (Fig. 5a). We randomly chose 20 SVs identified spanning across 9 chromosomes, 17 of which were confirmed through PCR analysis, supporting the reliability of our identified SVs (Supplementary Table 2). To account for pangenome variations and develop a key resource for breeding, we constructed a lettuce graph-based reference genome by integrating these linear reference genome sequences of Lactuca into the butterhead lettuce reference genome sequence (Methods). This graph-based genome is an essential resource for studying SVs and provides a comprehensive reference for accurately discovering SVs and their heritability, surpassing the limitations of traditional single-genome references.

a Number of different types of SVs in each genome compared to the butterhead lettuce reference genome. b Distribution of PAVs across the 9 chromosomes in butterhead lettuce genome. 1, gene density per Mb; 2, Gypsy density per Mb; 3, Copia density per Mb; 4; Density of DNA TEs per Mb. All tracks are intensity-coded, with the color intensity indicating the frequency of each element. Centromere, represented by orange color, are depicted on the outmost track of chromosomes, with numbers indicating coordinates in Mb. c Density of PAVs in the gene regions, RNA-TEs (Copia- and Gypsy-type LTRs), and DNA-TEs. Asterisks indicate significance differences (**P < 0.01, two-sided Wilcoxon signed-rank test) between the boundaries and flanking regions in each category. d Expression levels of genes associated with PAVs in butterhead lettuce. The numbers of genes with PAV and without PAV are 3291 and 18,293. In boxplots, the 25% and 75% quartiles are shown as lower and upper edges of boxes, respectively, and central lines denote the median. The whiskers extend to 1.5× the interquartile range. Asterisks indicate significant differences (**P < 0.01, two-sided Wilcoxon signed-rank test). e SVs in the CMT2A gene in L. indica compared to butterhead lettuce. The expression profiles of CMT2A in butterhead lettuce and L. indica are shown below. f Average DNA methylation level of CG, CHG, and CHH in L. indica transiently overexpressing CMT2A. Data are presented as mean ± s.d. (n = 2 biological replicates). The asterisk indicates a significant difference (*P < 0.05, one-way ANOVA test) between plant expressing 35S:CMT2A and an empty vector (Control). g CHH methylation levels across different genomic features including gene regions (left), Copia (middle), and Gypsy (right) in L. indica transiently overexpressing CMT2A (**P < 0.01, two-sided Wilcoxon signed-rank test). The exact P values (c, d, f, g) are provided in Supplementary Data 4. Source data are provided as a Source Data file.

SVs can be categorized into presence/absence variations (PAVs), copy number variations (CNVs), inversions (INV), and translocations (TRANS)12. An average of 92.3% of the identified SVs in the Lactuca genus were PAVs, with 42.0% as insertions (INS) and 50.3% as deletions (DEL) (Fig. 5a). These PAVs were present across the whole genome, particularly in heterochromatin regions enriched with LTRs (Fig. 5b). To study the potential relation of PAVs and LTRs, we analyzed the distribution of PAVs around genes and repetitive sequences, and found that PAVs were less prevalent in genic regions but were enriched at both the left and right boundaries of repetitive regions, irrespective of TEs of DNA class or RNA class (Copia and Gypsy) (Fig. 5c). This observation implies a possible association between SV events and TE activity, similar to what has been observed in many angiosperms such as maize34.

Interestingly, genes associated with PAVs exhibited lower expression levels compared to those without PAVs (Fig. 5d), suggesting that PAVs may influence gene transcription. For instance, the genomic region of CMT2A contained abundant PAVs in its gene body in L. indica and it exhibited lower expression levels compared to butterhead lettuce (Fig. 5e; Fig. 4h). This observation is consistent with the reduced CHH methylation levels in L. indica compared to butterhead lettuce (Fig. 4f). Consistently, overexpression of CMT2A increased the global CHH methylation level in L. indica (Fig. 5f), particularly in Copia- and Gypsy-type LTRs (Fig. 5g).

Another interesting example of PAVs was located on chromosome 5, involving the RLL2A gene, which encodes a MYB transcription factor that promotes anthocyanin accumulation35. RLL2A was only present in the cos lettuce exhibiting red-colored leaves and in Latin lettuce, but absent in other cultivated lettuce morphotypes (Supplementary Fig. 4b). The expression of RLL2A was only detected in the cos lettuce (Supplementary Table 3), and its overexpression increased anthocyanin levels in the leaves of both tobacco and butterhead lettuce (Supplementary Fig. 4c–f). These results suggest that a PAV involving RLL2A possibly results in variations in leaf anthocyanin content.

Association of SVs with lettuce domestication

Next, we identified domestication-associated PAVs in the assemblies of cultivated lettuce morphotypes compared to their wild progenitor, L. serriola (LSerG126V01). An analysis of the distribution of these PAVs across different genomic features revealed that they were more prevalent in intergenic regions (Fig. 6a). Approximately 6.8% of these PAVs were found within genic regions, including coding sequences and the 5’ and 3’ flanking regions (Fig. 6a). We then identified 506,004 domestication-associated PAV clusters, merged from the assemblies of cultivated lettuce morphotypes (Fig. 6b). These PAV clusters composed of 26.7% of private PAVs (present in only one accession) and 73.3% of the non-private PAVs, including 20.5% of core PAVs (present in all accessions) and 52.8% dispensable PAVs (present in 2-7 accessions) (Fig. 6b). On average, 4.8% of PAV clusters were private to each accession (Fig. 6c). These results suggest that a group of core domestication-associated PAVs are shared among different lettuce morphotypes, consistent with their origin from a single wild progenitor2,3.

a Number and genomic location of domestication-associated SVs in each genome compared to the L. serriola wild lettuce genome. b Proportions of private (present in only one accession), dispensable (present in 2-7 accessions), and core (present in all accessions) PAV clusters associated with domestication. c Comparisons of proportions of PAV clusters associated with domestication in each genome. d GO enrichment of genes related with domestication-associated PAVs. The plot shows the 10 top-scoring biological processes. e Phylogenetic tree based on protein sequences encoded by FLC genes of lettuce and Arabidopsis. f SVs in the FLC genes in the wild (L. serriola) and cultivated lettuce. Source data are provided as a Source Data file.

In total, 3232 genes related to core domestication-associated PAVs were identified, and these genes were enriched in important biological pathways, including vernalization response, early endosome to Golgi transport, and (1->3)-beta-D-glucan biosynthetic process (Fig. 6d). Interestingly, genes overrepresented in the vernalization response included multiple copies of the FLOWERING LOCUS C (FLC), which are known to repress flowering in many plant species36,37. We then analyzed the change in FLC copy numbers during lettuce domestication and found that cultivated leaf-type lettuce contained 5-8 copies of the FLC gene, while L. serriola had only 3 copies (Fig. 6e and Supplementary Fig. 5a, b), reminiscent of the variations in FLC copy numbers affecting flowering time in Brassica species38,39 and Arabidopsis species40. Consistently, cultivated leaf-type lettuce flowered much later compared to wild lettuce (Supplementary Fig. 5c). In addition, FLC gene copies only present in cultivated lettuce contained many long insertions or deletions in L. serriola genome (Fig. 6f), implying SVs is associated with loss of gene copies. These results suggest that FLC copies may have been selected during domestication to delay flowering, thereby extending the harvesting period and increasing yield in lettuce. Another PAV-related gene, G25Chr2g7314, encodes a homolog of AT3G49180 (RID3) (Supplementary Fig. 6a), which is involved in the regulation of cell division and heat response41,42. In addition, a > 90 kb deletion was identified that encompassing eight tandem repeated genes homologous to AT4G14130 (Supplementary Fig. 6b, c), which has been implicated in stress response43,44. Together, the domestication-associated SVs represent valuable resources for studying domestication-related traits in lettuce.

Discussion

Lettuce is a globally important crop, widely consumed for its high nutritional value and low calorie content. Gaining a deeper understanding of the hidden genomic variations shaped during lettuce evolution and domestication is invaluable for the research communities, driving innovations in plant breeding and expanding our understanding of plant evolution and diversity. High-quality pangenomes and graph-based reference genomes are crucial for research and breeding, as they capture the full spectrum of genetic diversity across multiple accessions, offering a comprehensive understanding of genetic variations within a species12,13,45. However, due to the complexities and large sizes of their genomes14,15,16,17, assembling high-quality genomes of the Lactuca genus is particularly challenging. Here, we present the high-quality super-pangenome and graph-based lettuce pangenome through combining our de novo chromosome-scale genome assemblies of 10 representative wild and cultivated lettuce accessions with 2 existing cultivated lettuce genomes. We reveal that diploidization that followed the last palaeopolyploidization has occurred much earlier than divergence between the Lactuca species whereas differential activity of transposable elements in L. indica is the cause of the important genome size variation. Moreover, we detect the landscape, genomic, and epigenetic features of structural variants, and their contributions to gene expression and domestication. These resources will expedite studies and breeding of this globally important crop.

Our genome assemblies, which include wild relatives of lettuce, provide valuable insights into Lactuca genome evolution and diversity. L. virosa and L. indica have genome sizes of 3.3 Gb and 5.5 Gb, respectively (Table 1), consistent with the karyotype analyses showing that their larger chromosomes compared to cultivated lettuce30. The large genome size of these wild relatives, practically L. indica, is intriguing. It has been proposed that lettuce underwent WGT through a paleopolyploidization event shared by subfamilies near the crown node of the Asteraceae family, followed by a relatively rapid post-polyploid diploidization process14,15,29. Similarly, the same hexaploidization event in the common ancestor of Brassica and Raphanus also led to significant diploidization, marked by extensive gene losses and divergence in the expression of retained duplicates in Brassica and raddish46. Nevertheless, our analyses reveal a similar percentage of WGT genes in L. virosa and L. indica compared to all cultivated lettuce morphotypes (Fig. 3a), suggesting a comparable diploidization effect across the Lactuca genus. Strikingly, while all Lactuca genomes contain a high abundance of repetitive sequences, L. indica exhibits a 2.21-fold increase in repeat length compared to other Lactuca genomes, with a particularly dramatic 6.75-fold increase in Copia elements (Fig. 4a). We further revealed that this extensive transposon expansion is likely due to lower CHH DNA methylation levels, which is associated with low transcriptional levels of CMT2 genes in L. indica compared to cultivated butterhead lettuce (Fig. 4e–h). Consistently, overexpression of CMT2 in L. indica remarkably increases CHH DNA methylation around transposons (Fig. 5f, g), but the long-term effects of these changes on transposon expansion and genome size in lettuce genome evolution remain to be thoroughly examined. DNA methylation is one of many factors influencing TEs expansion and genomic size. Although other Lactuca species examined did not exhibit notable changes of CMT2 expression correlated with CHH methylation, our current results do not exclude the effect of methylation on TE expansion and genomic stability, as complex mechanisms are involved in genomic stability, including chromosome rearrangements, the S-phase checkpoint, and double-strand-break repair machinery47, which may also be regulated directly or indirectly by DNA methylation48.

Based on the 12 Lactuca genome assemblies, we construct a graph-based reference genome for lettuce to facilitate the utilization of genetic diversity from our super-pangenome. We reveal the landscape of SVs and their contributions to gene expression and domestication. Strong genomic shocks always occur during polyploidization and subsequent diploidization, which could induce epigenetic changes and TE activities involved in chromosome arrangement and fusion, leading to abundant SVs49,50,51. We find an association between SVs and TE activities (Fig. 5c), implying that transposons contribute to the generation of SVs, similar to observations in maize34. These SVs could directly lead to loss, gain, and reshuffling of important genes and regulatory elements, impacting phenotype and causing diseases52,53. PAVs may influence gene transcription, as genes associated with PAVs tend to show lower expression levels compared those without PAVs (Fig. 5d). Moreover, by analyzing the SVs in cultivated lettuce morphotypes and their wild progenitor, we identify the landscape of domestication-associated SVs. Interestingly, genes related to domestication-associated PAVs are highly enriched in vernalization response, including the FLC genes that have conserved roles in inhibiting flowering54. PAVs in FLC genes are associated with a high number of intact genes in cultivated lettuce morphotypes compared to their wild progenitor (Fig. 6e, f). Copy number variations have significant consequences34,55, and FLC copy number variations have been shown to correlated with flowering time among different Arabidopsis species40 and Brassica species38. Consistently, the observed higher number of FLC copies in cultivated leafy-type lettuce, compared to wild lettuce, could be associated with their delayed flowering traits (Supplementary Fig. 5c), a desired characteristic for many leafy vegetable crops that has arisen through domestication56. Intriguingly, the seed-harvesting oilseed lettuce contains five FLC copies yet exhibits a flowering time comparable to wild lettuce, implying that oilseed lettuce may have undergone common domestication of FLC shared with other cultivated lettuce, alongside specific early flowering domestication to facilitate seed harvesting. Nevertheless, future genome assemblies involving a broader range of wild species and cultivated lettuce morphotypes are necessary to validate SVs, including their relationship to FLC copy numbers, while addressing potential sampling bias. As FLC is an important target of selection during crop domestication and improvement57, exemplified by the introgression of FLC3 from B. rapa into the Asian semi-winter oilseed rape (B. napus)39, further research and breeding efforts focusing on diverse FLC loci in lettuce morphotypes are essential for advancing our understanding of flowering domestication in vegetable crops.

Taken together, our pangenome dataset, encompassing both wild and cultivated lettuce accessions, lays a crucial foundation for future functional genomics research in lettuce. It enables the identification of complex variations that may be missed when mapping short reads to a single reference genome. The graph-based genome reference also provides a robust platform for detecting genetic variations at the pangenome level. Given that the comprehensive assessment and effective utilization of genetically diverse germplasm are vital for crop improvement12,58,59, our pangenome, which includes four wild relative species with distant relationships but sexual compatibility with modern lettuce60,61, will also facilitate the incorporation of wild gene resources into lettuce breeding. Thus, the Lactuca pangenome serves as comprehensive resources for comparative genomics, biological studies, and molecular breeding, and will significantly benefit lettuce research and breeding communities.

Methods

Plant materials and sampling

Seeds of the Lactuca genus were obtained from the Center for Genetic Resources, the Netherlands (http://www.wageningenur.nl/) (Supplementary Data 1). Dry seeds were surface sterilized using 10% sodium hypochlorite and grown on soil in a growth chamber with a 16 h light/8 h dark cycle at 24 °C (day)/22 °C (night). The third pair of leaves at 30 days after planting (30 DAP) was collected at ZT4 (Zeitgeber time) and used for genomic DNA isolation and library construction.

Genome sequencing and assembly

Frozen leaves were ground into fine powder in liquid nitrogen for the preparation of high-molecular-weight DNA18. In brief, nuclei were extracted using the nuclei isolation buffer [40% glycerol, 0.25 M sucrose, 20 mM HEPES, 1 mM MgCl2, 5 mM KCl, 0.25% Triton X-100, 0.1 mM PMSF, 1× Protease Inhibitor Cocktail (Roche), and 0.1% 2-mercaptoethanol]. The nuclei were then lysed in 500 μL of nuclei lysis buffer (50 mM Tris-HCl, 1% SDS, 10 mM EDTA) supplemented with 10 μg of Proteinase K (Roche). Genomic DNA was subsequently extracted using the DNeasy Plant Mini Kit (Qiagen) following the manufacturer’s protocol. The purified genomic DNA was used for library construction for PacBio HiFi sequencing, and the resulting libraries were run on the PacBio Sequel IIe platform.

For Hi-C library construction, ~0.5 g of fresh leaves at 30 DAP were harvested and crosslinked with 1% formaldehyde. Nuclei were isolated using the nuclei isolation buffer described above, and the chromatin was digested by DpnII (NEB). The digested chromatin was end-filled by biotin-14-dCTP, proximally ligated using T4 DNA Ligase (NEB), and purified with the QIAquick PCR Purification Kit (Qiagen). The purified DNA was sonicated to produce 300–500 bp long fragments, which were subsequently pulled down by Dynabeads MyOne Streptavidin T1 beads (Invitrogen), end-repaired, and 3’-end adenylated followed by ligation of the adapter (AITbiotech) according to the protocol of NEBNext® Ultra™ II DNA Library Prep Kit for Illumina® (NEB). These adapter-ligated DNA fragments were subsequently amplified by a 6-cycle of PCR amplification with Q5® HiFi Hot Start DNA Polymerase (NEB). After purification with the VAHTSTM DNA Clean Beads (Vazyme), the Hi-C libraries were sequenced on a NovaSeq platform (Illumina), generating 150 bp paired-end reads.

For genome assembly, PacBio HiFi reads were used for the initial whole-genome assembly by Hifiasm (v0.19.5)62 with default parameters. Based on the mapping results of Hi-C sequencing data processed by Juicer (v1.6.2)63, the final contigs from the initial whole-genome assembly were scaffolded into the chromosome-scale assembly using the three-dimensional de novo DNA assembly (3D DNA) pipeline (v.180114)64 with parameters (-r 3 -m diploid). Finally, we manually corrected assembly error using Juicebox (v1.8.8)65 and generated the final scaffolds, with the largest 9 scaffolds representing 9 chromosomes. Genome assembly completeness was assessed using BUSCO66 with the “genome” mode based on the eudicotyledons_odb10 database.

RNA-seq and gene annotation

Total RNA was extracted from various tissues of each accession, including leaves, roots, stems, and flowers (Supplementary Data 1), using Trizol reagent (Invitrogen), followed by mRNA purification with the Dynabeads mRNA purification kit (Invitrogen). Subsequently, strand-specific mRNA-seq libraries were constructed using the VAHTS Universal V8 RNA-seq Library Prep Kit (Vazyme) and sequenced on the NovaSeq platform (Illumina) to generate 150-bp paired-end reads. After filtering the raw reads with fastp67, clean RNA-seq reads were mapped using HISAT2 (v2.1.0)68 with the parameter (-dta -rnastrandness RF). Following the removal potential PCR duplicates and extraction of uniquely mapped reads, the expression levels (FPKM) of each gene were calculated by StringTie (v1.3.3b)69 with parameters (-B -A -rf).

Gene annotation was performed by integrating RNA-seq data from multiple tissues, ab initio gene prediction, and homology-based gene prediction. The above-mentioned clean RNA-seq reads were mapped onto the corresponding reference genomes of each accession using HISAT2 (v.2.1.0)68, and transcripts were reconstructed by StringTie (v1.3.3b)69. Meanwhile, genome-guided de novo assembly of transcripts was performed with the RNA-seq data using Trinity (v2.1.1)70, and gene models were predicted using the PASA pipeline (v2.3.3)71 with the parameters (--MAX_INTRON_LENGTH 20000—-transcribed_is_aligned_orient—-stringent_alignment_overlap 30.0). Subsequently, candidate coding regions were identified by TransDecoder (v5.3.0) (https://github.com/TransDecoder/TransDecoder) based on the transcript sequences generated by both StringTie and Trinity. The resulting gene sets were used for model training of the ab initio gene prediction program AUGUSTUS (v3.2.2)72, and then, ab initio gene prediction was performed based on the repeat-masked genome generated by RepeatMasker. For the homology-based approach, homologous proteins from the genomes of Arabidopsis thaliana, Helianthus annuus, Glycine max, Solanum lycopersicum, Zea mays, Oryza sativa, and Setaria italica were downloaded from the Phytozome 13 or NCBI databases (Phytozome 13: https://phytozome.jgi.doe.gov/pz/portal.html; NCBI: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/) for prediction via Exonerate (v2.2.0)73. Finally, the combined gene annotation sets from these three strategies were built using EVidenceModeler (v1.1.1)74 with parameters (--segment size 500000—-overlapSize 10000).

Orthologous genes identification, pangenome construction, and GO analysis

Orthologous gene clusters were recognized using OrthoFinder (v2.2.7)75 with parameters (-S diamond -M msa -T raxml). Subsequently, these gene clusters were used to estimate divergence time with r8s (v1.81)76, and the constrained divergence time range was used to construct phylogenetic trees based on TimeTree77. Contraction and expansion of gene families were identified using CAFE (v4.2.1)78 with parameters (-p 0.05 -filter), which accounted for phylogenetic history and provided a statistical basis for evolutionary inference. P values were used to estimate the likelihood of the observed sizes based on average rates of retention and loss, and to determine expansion or contraction of individual gene families at each node.

A pangenome analysis of gene families was performed using the Markov clustering approach75. In brief, all paired genes were identified through all-versus-all comparisons using DIAMOND (v2.1.5)79 with an E-value cutoff of 1 × 10−5, and then clustered using OrthoFinder (v2.3.12)75. Subsequently, genes were classified into four categories: core (present in all 12 accessions), soft core (present in 10–11 accessions), dispensable (present in 2-9 accessions), and private (present in only one accession). GO annotations were obtained by mapping protein sequences to the eggNOG database80 using DIAMOND (v2.1.5)79.

Analyses of repetitive sequences and TEs

Repeats were de novo annotated and organized into a repeat consensus database using RepeatModeler (v2.0.3) (http://www.repeatmasker.org/). Intact LTR retrotransposons were de novo annotated using LTR-FINDER (v.1.0.9)81 and LTR_retriever (v.2.9.5)82 using default parameters. The repeat database was used to identify repeats in the intact LTR-masked assembly by RepeatMasker (v. 4.1.2) with parameters (-cutoff 250) (http://www.repeatmasker.org/). The insertion times of the intact LTR retrotransposons were estimated based on a nucleotide substitution rate of 7 × 10−9 per site per generation (assumed to equal one year) by LTR_retriever (v.2.9.5)82.

SV identification and graph-based genome assembly

For detecting PAVs and CNVs, all genomes were divided into 10-kb windows with 100-bp steps (100 × depth of genome), and then mapped onto the butter lettuce genome (ButterG25V01) using minimap2 (v2.18-r1015) with default parameters83. Mapped results were sorted by Samtools for SV calling using cuteSV (v1.0.11) with options (-s 10 –r 500 -l 50 -sl 50; Supplementary Fig. 1)84. To detect inversion and translocation events, all genomes were aligned to ButterG25V01 using NUCmer (‘-maxmatch -c 100 -l 50)85. The resulting alignment blocks, filtered by the one-to-one alignment mode, were then used to identify inversion and translocation events by SyRI (v.1.6.3)86,87. ButterG25V01 was also used as the reference genome to construct a graph-based genome with the vg tool (v.1.25.0) (https://github.com/vgteam/vg)88. Primers used for SV verification are listed in Supplementary Data 3.

The PAVs present or absent in each cultivated types compared to their wild progenitor were considered as domestication-related that. According to allele frequencies, these domestication-related PAV were defined as private (present in only one accession), dispensable PAVs (present in 2-7 accessions), core PAVs (present in all accessions).

Functional validation of genes

The full-length coding sequences of RLL2A from cos lettuce and CMT2 from butterhead lettuce were amplified with their gene-specific primers (Supplementary Data 3) and cloned into the pJL-TRBO-G vector89. The resulting binary plasmids of 35S:RLL2A and 35S:CMT2 were transformed into Agrobacterium tumefaciens GV3101. Agrobacterium cells harboring 35S:RLL2A or 35S:CMT2 were resuspended in the infiltration medium (10 mM MES, pH 5.7, 10 mM MgCl2, 200 mM acetosyringone) to an OD600 of 1.0, and then infiltrated into the abaxial surface of 3-week-old Nicotiana benthamiana or lettuce leaves using syringes. After infiltration, lettuce and N. benthamiana plants were grown in a growth chamber.

MethylC-seq and analysis

Genomic DNA was isolated using the cetyltrimethylammonium bromide approach90. After eliminating RNA with RNase A (NEB), approximately 2 µg of genomic DNA was fragmented into 300–500 bp, end-repaired, and 3’-end adenylated, followed by ligation of the methylated adapter (AITbiotech) based on the NEBNext® Ultra™ II DNA Library Prep Kit for Illumina® (NEB) protocol. The adapter-ligated DNA fragments were treated with bisulfite using the Zymo EZ DNA Methylation-GoldTM kit (Zymo Research), and subsequently amplified with a 10-cycle PCR using Q5U® HiFi Hot Start DNA Polymerase (NEB). After cleanup of the PCR products with VAHTS DNA Clean Beads (Vazyme), the MethylC-seq libraries were sequenced on the NovaSeq platform (Illumina), producing 150-bp paired-end reads.

The raw MethylC-seq reads were first filtered by fastp67, and the clean reads were then mapped onto the corresponding reference genome using Bismark (v0.15.0) with options (-score_min L,0,-0.2 -X 1000)91. The mapped results were used for calculating average methylation levels for every 100-bp interval of each gene and TE, encompassing 2-kb upstream and downstream flanking regions.

qPCR analysis

Total RNA was extracted using the RNeasy Plant Mini Kit (Qiagen) and reverse transcribed with the HiScript III RT SuperMix (Vazyme) following the manufacturers’ instructions. qPCR was performed using Taq Pro Universal SYBR Green Master Mix (Vazyme) on the CFX Opus 384 Real-Time PCR System (Bio-Rad). Relative gene expression levels were determined using the 2−ΔΔCt method7. LsActin was used as the internal control. Primers used for qPCR analysis are listed in Supplementary Data 3.

Reporting summary

Further information on research design is available in the Nature Portfolio Reporting Summary linked to this article.

Data availability

The high-throughput sequencing data of genome, transcriptomes, DNA methylomes data generated in this study have been deposited in the Genome Sequence Archive in BIG Data Center under the accession PRJCA026911 and Genome Warehouse under the accessions GWHETKD00000000.1 [https://ngdc.cncb.ac.cn/gwh/Assembly/85030/show], GWHETKC00000000.1 [https://ngdc.cncb.ac.cn/gwh/Assembly/85029/show], GWHETKB00000000.1 [https://ngdc.cncb.ac.cn/gwh/Assembly/85028/show], GWHETKA00000000.1 [https://ngdc.cncb.ac.cn/gwh/Assembly/85027/show], GWHETJZ00000000.1 [https://ngdc.cncb.ac.cn/gwh/Assembly/85026/show], GWHETKI00000000.1 [https://ngdc.cncb.ac.cn/gwh/Assembly/85035/show], GWHETKH00000000.1 [https://ngdc.cncb.ac.cn/gwh/Assembly/85034/show], GWHETKG00000000.1 [https://ngdc.cncb.ac.cn/gwh/Assembly/85033/show], GWHETKF00000000.1 [https://ngdc.cncb.ac.cn/gwh/Assembly/85032/show], and GWHETKE00000000.1 [https://ngdc.cncb.ac.cn/gwh/Assembly/85031/show]. Source data are provided with this paper.

References

Shatilov, M. V., Razin, A. F. & Ivanova, M. I. Analysis of the world lettuce market. IOP Conf. Ser.: Earth Environ. Sci. 395, 012053 (2019).

Zhang, L. et al. RNA sequencing provides insights into the evolution of lettuce and the regulation of flavonoid biosynthesis. Nat. Commun. 8, 2264 (2017).

Wei, T. et al. Whole-genome resequencing of 445 Lactuca accessions reveals the domestication history of cultivated lettuce. Nat. Genet 53, 752–760 (2021).

Lebeda, A., Ryder, E.J., Grube, R., Dolezˇalova´, I. & Krˇ´ıstkova, E. Lettuce (Asteraceae; Lactuca spp.). Genetic Resources, Chromosome Engineering, and Crop Improvement Vol. 3 (ed. Singh, R. J) 377–472 (CRC Press, 2006).

Lebeda, A. et al. Wild Lactuca species, their genetic diversity, resistance to diseases and pests, and exploitation in lettuce breeding. Eur. J. Plant Pathol. 138, 597–640 (2014).

Fertet, A. et al. Sequence of the mitochondrial genome of Lactuca virosa suggests an unexpected role in Lactuca sativa’s evolution. Front. Plant Sci. 12, 697136 (2021).

Cao, S., Sawettalake, N., Li, P., Fan, S. & Shen, L. DNA methylation variations underlie lettuce domestication and divergence. Genome Biol. 25, 158 (2024).

Lebeda, A. et al. Research gaps and challenges in the conservation and use of North American wild Lettuce germplasm. Crop Sci. 59, 2337–2356 (2019).

Qin, P. et al. Pan-genome analysis of 33 genetically diverse rice accessions reveals hidden genomic variations. Cell 184, 3542–3558.e16 (2021).

Liu, Y. et al. Pan-genome of wild and cultivated soybeans. Cell 182, 162–176.e13 (2020).

Li, N. et al. Super-pangenome analyses highlight genomic diversity and structural variation across wild and cultivated tomato species. Nat. Genet. 55, 852–860 (2023).

Shi, J., Tian, Z., Lai, J. & Huang, X. Plant pan-genomics and its applications. Mol. Plant 16, 168–186 (2023).

Bayer, P. E., Golicz, A. A., Scheben, A., Batley, J. & Edwards, D. Plant pan-genomes are the new reference. Nat. Plants 6, 914–920 (2020).

Reyes-Chin-Wo, S. et al. Genome assembly with in vitro proximity ligation data and whole-genome triplication in lettuce. Nat. Commun. 8, 14953 (2017).

Shen, F. et al. Comparative genomics reveals a unique nitrogen-carbon balance system in Asteraceae. Nat. Commun. 14, 4334 (2023).

Xiong, W. et al. Genome assembly and analysis of Lactuca virosa: implications for lettuce breeding. G3 (Bethesda) 13, jkad204 (2023).

Xiong, W. et al. The genome of Lactuca saligna, a wild relative of lettuce, provides insight into non-host resistance to the downy mildew Bremia lactucae. Plant J. 115, 108–126 (2023).

Cao, S., Sawettalake, N. & Shen, L. Gapless genome assembly and epigenetic profiles reveal gene regulation of whole-genome triplication in lettuce. Gigascience 13, giae043 (2024).

Wang, K. et al. The complete telomere-to-telomere genome assembly of lettuce. Plant Commun. 5, 101011 (2024).

Cao, S. & Chen, Z.J. Transgenerational epigenetic inheritance during plant evolution and breeding. Trends Plant Sci. 29, 1203–1223 (2024).

Venney, C.J., Anastasiadi, D., Wellenreuther, M. & Bernatchez, L. The evolutionary complexities of DNA methylation in animals: from plasticity to genetic evolution. Genome Biol. Evol. 15, evad216 (2023).

Cao, S. et al. Asymmetric variation in DNA methylation during domestication and de-domestication of rice. Plant Cell 35, 3429–3443 (2023).

Zhang, Y. et al. Global impact of somatic structural variation on the DNA methylome of human cancers. Genome Biol. 20, 209 (2019).

Xu, G. et al. Evolutionary and functional genomics of DNA methylation in maize domestication and improvement. Nat. Commun. 11, 5539 (2020).

Zhang, L. et al. A natural tandem array alleviates epigenetic repression of IPA1 and leads to superior yielding rice. Nat. Commun. 8, 14789 (2017).

Zhang, H., Lang, Z. & Zhu, J. K. Dynamics and function of DNA methylation in plants. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 19, 489–506 (2018).

Kankel, M. W. et al. Arabidopsis MET1 cytosine methyltransferase mutants. Genetics 163, 1109–22 (2003).

Lindroth, A. M. et al. Requirement of CHROMOMETHYLASE3 for maintenance of CpXpG methylation. Science 292, 2077–80 (2001).

Huang, C. H. et al. Multiple polyploidization events across Asteraceae with two nested events in the early history revealed by nuclear phylogenomics. Mol. Biol. Evol. 33, 2820–2835 (2016).

Matoba, H., Mizutani, T., Nagano, K., Hoshi, Y. & Uchiyama, H. Chromosomal study of lettuce and its allied species (Lactuca spp., Asteraceae) by means of karyotype analysis and fluorescence in situ hybridization. Hereditas 144, 235–43 (2007).

Badouin, H. et al. The sunflower genome provides insights into oil metabolism, flowering and Asterid evolution. Nat. Methods 546, 148–152 (2017).

Barker, M. S. et al. Multiple paleopolyploidizations during the evolution of the Compositae reveal parallel patterns of duplicate gene retention after millions of years. Mol. Biol. Evol. 25, 2445–55 (2008).

Zhao, M., Zhang, B., Lisch, D. & Ma, J. Patterns and consequences of subgenome differentiation provide insights into the nature of paleopolyploidy in plants. Plant Cell 29, 2974–2994 (2017).

Marroni, F., Pinosio, S. & Morgante, M. Structural variation and genome complexity: is dispensable really dispensable?. Curr. Opin. Plant Biol. 18, 31–6 (2014).

Su, W. et al. Characterization of four polymorphic genes controlling red leaf colour in lettuce that have undergone disruptive selection since domestication. Plant Biotechnol. J. 18, 479–490 (2020).

Madrid, E., Chandler, J. W. & Coupland, G. Gene regulatory networks controlled by FLOWERING LOCUS C that confer variation in seasonal flowering and life history. J. Exp. Bot. 72, 4–14 (2021).

Soppe, W. J. J., Vinegra de la Torre, N. & Albani, M. C. The Diverse Roles of FLOWERING LOCUS C in Annual and Perennial Brassicaceae Species. Front. Plant Sci. 12, 627258 (2021).

Belser, C. et al. Chromosome-scale assemblies of plant genomes using nanopore long reads and optical maps. Nat. Plants 4, 879–887 (2018).

Sun, F. et al. The high-quality genome of Brassica napus cultivar ‘ZS11’ reveals the introgression history in semi-winter morphotype. Plant J. 92, 452–468 (2017).

Jiang, X., Song, Q., Ye, W. & Chen, Z. J. Concerted genomic and epigenomic changes accompany stabilization of Arabidopsis allopolyploids. Nat. Ecol. Evol. 5, 1382–1393 (2021).

Tamaki, H. et al. Identification of novel meristem factors involved in shoot regeneration through the analysis of temperature-sensitive mutants of Arabidopsis. Plant J. 57, 1027–39 (2009).

Ohbayashi, I. et al. Evidence for a role of ANAC082 as a ribosomal stress response mediator leading to growth defects and developmental alterations in Arabidopsis. Plant Cell 29, 2644–2660 (2017).

Larkindale, J. & Vierling, E. Core genome responses involved in acclimation to high temperature. Plant Physiol. 146, 748–61 (2008).

Mahalingam, R. et al. Characterizing the stress/defense transcriptome of Arabidopsis. Genome Biol. 4, R20 (2003).

Wang, S., Qian, Y. Q., Zhao, R. P., Chen, L. L. & Song, J. M. Graph-based pan-genomes: increased opportunities in plant genomics. J. Exp. Bot. 74, 24–39 (2023).

Moghe, G. D. et al. Consequences of whole-genome triplication as revealed by comparative genomic analyses of the wild radish Raphanus raphanistrum and three other Brassicaceae species. Plant Cell 26, 1925–1937 (2014).

Aguilera, A. & Gomez-Gonzalez, B. Genome instability: a mechanistic view of its causes and consequences. Nat. Rev. Genet 9, 204–17 (2008).

Zhou, D. & Robertson, K.D. Role of DNA methylation in genome stability. in Genome Stability (eds Kovalchuk, I. & Kovalchuk, O.) Ch. 24, 409–424 (Academic Press, 2016).

Charles, M. et al. Dynamics and differential proliferation of transposable elements during the evolution of the B and A genomes of wheat. Genetics 180, 1071–86 (2008).

Baduel, P., Bray, S., Vallejo-Marin, M., Kolář, F. & Yant, L. The “Polyploid Hop”: shifting challenges and opportunities over the evolutionary lifespan of genome duplications. Front. Ecol. Evol. 6, 117 (2018).

Wang, L. et al. Altered chromatin architecture and gene expression during polyploidization and domestication of soybean. Plant Cell 33, 1430–1446 (2021).

Koeppel, J., Weller, J., Vanderstichele, T. & Parts, L. Engineering structural variants to interrogate genome function. Nat. Genet. 56, 2623–2635 (2024).

Weischenfeldt, J., Symmons, O., Spitz, F. & Korbel, J. O. Phenotypic impact of genomic structural variation: insights from and for human disease. Nat. Rev. Genet. 14, 125–38 (2013).

Michaels, S. D. & Amasino, R. M. FLOWERING LOCUS C encodes a novel MADS domain protein that acts as a repressor of flowering. Plant Cell 11, 949–56 (1999).

DeBolt, S. Copy number variation shapes genome diversity in Arabidopsis over immediate family generational scales. Genome Biol. Evol. 2, 441–53 (2010).

Conrady, M. et al. Plants cultivated for ecosystem restoration can evolve toward a domestication syndrome. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 120, e2219664120 (2023).

Schilling, S., Pan, S., Kennedy, A. & Melzer, R. MADS-box genes and crop domestication: the jack of all traits. J. Exp. Bot. 69, 1447–1469 (2018).

Varshney, R. K. et al. 5Gs for crop genetic improvement. Curr. Opin. Plant Biol. 56, 190–196 (2020).

Golicz, A. A., Batley, J. & Edwards, D. Towards plant pangenomics. Plant Biotechnol. J. 14, 1099–105 (2016).

de Vries, I. M. Origin and domestication of Lactuca sativa L. Genet. Resour. Crop Evol. 44, 165–174 (1997).

Lindqvist, K. On the origin of cultivated lettuce. Hereditas 46, 319–350 (1960).

Cheng, H., Concepcion, G. T., Feng, X., Zhang, H. & Li, H. Haplotype-resolved de novo assembly using phased assembly graphs with hifiasm. Nat. Methods 18, 170–175 (2021).

Durand, N. C. et al. Juicer provides a one-click system for analyzing loop-resolution Hi-C experiments. Cell Syst. 3, 95–8 (2016).

Dudchenko, O. et al. De novo assembly of the Aedes aegypti genome using Hi-C yields chromosome-length scaffolds. Science 356, 92–95 (2017).

Durand, N. C. et al. Juicebox provides a visualization system for Hi-C contact maps with unlimited zoom. Cell Syst. 3, 99–101 (2016).

Simao, F. A., Waterhouse, R. M., Ioannidis, P., Kriventseva, E. V. & Zdobnov, E. M. BUSCO: assessing genome assembly and annotation completeness with single-copy orthologs. Bioinformatics 31, 3210–2 (2015).

Chen, S., Zhou, Y., Chen, Y. & Gu, J. fastp: an ultra-fast all-in-one FASTQ preprocessor. Bioinformatics 34, i884–i890 (2018).

Kim, D., Langmead, B. & Salzberg, S. L. HISAT: a fast spliced aligner with low memory requirements. Nat. Methods 12, 357–60 (2015).

Pertea, M. et al. StringTie enables improved reconstruction of a transcriptome from RNA-seq reads. Nat. Biotechnol. 33, 290–5 (2015).

Grabherr, M. G. et al. Full-length transcriptome assembly from RNA-Seq data without a reference genome. Nat. Biotechnol. 29, 644–52 (2011).

Haas, B. J. et al. Improving the Arabidopsis genome annotation using maximal transcript alignment assemblies. Nucleic Acids Res. 31, 5654–66 (2003).

Stanke, M., Diekhans, M., Baertsch, R. & Haussler, D. Using native and syntenically mapped cDNA alignments to improve de novo gene finding. Bioinformatics 24, 637–44 (2008).

Slater, G. S. & Birney, E. Automated generation of heuristics for biological sequence comparison. BMC Bioinform. 6, 31 (2005).

Haas, B. J. et al. Automated eukaryotic gene structure annotation using EVidenceModeler and the program to assemble spliced alignments. Genome Biol. 9, R7 (2008).

Emms, D. M. & Kelly, S. OrthoFinder: phylogenetic orthology inference for comparative genomics. Genome Biol. 20, 238 (2019).

Sanderson, M. J. r8s: inferring absolute rates of molecular evolution and divergence times in the absence of a molecular clock. Bioinformatics 19, 301–2 (2003).

Kumar, S., Stecher, G., Suleski, M. & Hedges, S. B. Timetree: a resource for timelines, timetrees, and divergence times. Mol. Biol. Evol. 34, 1812–1819 (2017).

Han, M. V., Thomas, G. W., Lugo-Martinez, J. & Hahn, M. W. Estimating gene gain and loss rates in the presence of error in genome assembly and annotation using CAFE 3. Mol. Biol. Evol. 30, 1987–97 (2013).

Buchfink, B., Reuter, K. & Drost, H. G. Sensitive protein alignments at tree-of-life scale using DIAMOND. Nat. Methods 18, 366–368 (2021).

Cantalapiedra, C. P., Hernandez-Plaza, A., Letunic, I., Bork, P. & Huerta-Cepas, J. eggNOG-mapper v2: functional annotation, orthology assignments, and domain prediction at the metagenomic scale. Mol. Biol. Evol. 38, 5825–5829 (2021).

Xu, Z. & Wang, H. LTR_FINDER: an efficient tool for the prediction of full-length LTR retrotransposons. Nucleic Acids Res. 35, W265–8 (2007).

Ou, S. & Jiang, N. LTR_retriever: a highly accurate and sensitive program for identification of long terminal repeat retrotransposons. Plant Physiol. 176, 1410–1422 (2018).

Li, H. Minimap2: pairwise alignment for nucleotide sequences. Bioinformatics 34, 3094–3100 (2018).

Jiang, T. et al. Long-read-based human genomic structural variation detection with cuteSV. Genome Biol. 21, 189 (2020).

Marcais, G. et al. MUMmer4: a fast and versatile genome alignment system. PLoS Comput Biol. 14, e1005944 (2018).

Goel, M., Sun, H., Jiao, W. B. & Schneeberger, K. SyRI: finding genomic rearrangements and local sequence differences from whole-genome assemblies. Genome Biol. 20, 277 (2019).

Li, X. et al. Large-scale gene expression alterations introduced by structural variation drive morphotype diversification in Brassica oleracea. Nat. Genet. 56, 517–529 (2024).

Garrison, E. et al. Variation graph toolkit improves read mapping by representing genetic variation in the reference. Nat. Biotechnol. 36, 875–879 (2018).

Lindbo, J. A. TRBO: a high-efficiency tobacco mosaic virus RNA-based overexpression vector. Plant Physiol. 145, 1232–40 (2007).

Allen, G. C., Flores-Vergara, M. A., Krasynanski, S., Kumar, S. & Thompson, W. F. A modified protocol for rapid DNA isolation from plant tissues using cetyltrimethylammonium bromide. Nat. Protoc. 1, 2320 (2006).

Krueger, F. & Andrews, S. R. Bismark: a flexible aligner and methylation caller for Bisulfite-Seq applications. Bioinformatics 27, 1571–2 (2011).

Acknowledgements

We thank the Centre for Genetic Resources, the Netherlands for providing seeds of the Lactuca genus, and Centre for Bioimaging Sciences of National University of Singapore for providing the computing facility for data analysis. We thank Prof. Hao Yu and members of Shen Lab for discussion and comments on this manuscript. This work was supported by the Singapore Food Story R&D Programme (SFS_RND_SUFP_001_04; L.S.), the National Research Foundation Competitive Research Programme (NRF-CRP22-2019-0001; L.S.), and the intramural research support from Temasek Life Sciences Laboratory.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

S.C. and L.S. conceived and designed the research. S.C. performed experiments and analyzed the data. N.S. provided materials. S.C. and L.S. wrote the manuscript. All authors read and approved the paper.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests

Peer review

Peer review information

Nature Communications thanks Xingtan Zhang and the other, anonymous, reviewer(s) for their contribution to the peer review of this work. A peer review file is available.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Source data

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Cao, S., Sawettalake, N. & Shen, L. Lactuca super-pangenome provides insights into lettuce genome evolution and domestication. Nat Commun 16, 7257 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-025-62641-w

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-025-62641-w