Abstract

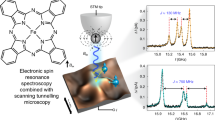

Spin-active materials with sensitive electron spin centers have drawn significant attention in quantum sensing due to their unique quantum characteristics. Herein, we report a molecular spin sensor based on metallofullerene Y2@C79N for in-situ monitoring of crystallization behavior and phase transitions in aromatic materials with high precision. Temperature-dependent spin resonance signals of Y2@C79N dissolved in aromatic materials are analyzed using electron paramagnetic resonance (EPR) spectroscopy. Two functional aromatic materials, 1-chloronaphthalene and a liquid crystal material of 5CB, are selected based on their significant crystallization-related technological applications. For Y2@C79N in 1-chloronaphthalene, a distinct EPR signal transition attributed to the crystallization of 1-chloronaphthalene. For Y2@C79N in 5CB, three EPR signal transitions correspond to the phase transitions of crystalline 5CB. Theoretical calculations reveal that the sensing mechanism originates from crystallization-induced alignment of fullerene molecular orientation. This work establishes metallofullerene-based spin probes as a powerful analytical tool for detecting the crystallization processes in materials.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Recently, the use of electron spins in advanced science and technology has been actively studied owing to their quantum characteristics that can result in the development of new functionalities1,2,3,4,5. Among these studies, molecular spins have attracted considerable attention because these systems exhibit unique features and advantages6,7,8,9,10, including spin preparation and modulation via chemical engineering, spin sensing, and measurements at the molecular level. Therefore, exploring the molecular spin properties and functions is essential to advance related applications.

Metallofullerenes with electron spin characteristics, such as Y2@C79N11, Sc3C2@C8012, Y@C8213, and Gd2@C79N14, are emerging as molecular spin materials that have characteristic electron paramagnetic resonance (EPR) signals with potential applications in diverse fields including spin sensors and quantum information processing. Among them, the aza-metallofullerene Y2@C79N has an electron spin localized on the internal cluster and shows distinct EPR signals15,16. Previously, we revealed that the internal spin in Y2@C79N can sense external environmental conditions, such as cage modification17,18 and orientation11,19. We investigated the spin modulation of Y2@C79N by encapsulating it within the pores of a metal–organic framework (MOF) of MOF-177 and revealed its orientation sensitivity for Y2@C79N19. Additionally, we studied the spin modulation of Y2@C79N when incorporated into molecular nanorings, highlighting its orientation sensitivity within supramolecular systems20. Our findings reveal the characteristic orientation of Y2@C79N in organic materials containing phenyl groups, demonstrating the spin capacity to sensitively detect buckyball orientation. Therefore, further exploration of the spin-sensing function of Y2@C79N corresponding to the molecular orientation is vital.

Organic molecular orientation is widely observed in processes such as crystallization, phase transition, and molecular assembly21,22,23,24. For example, in organic solar cells (OSCs), the short range crystallization of donor/acceptor materials has been reported to be significant21. To enhance the device performance of OCSs, 1-chloronaphthalene is often used as a solvent additive because it improves the degree of order of the polymer films. This occurs because the crystallization of 1-chloronaphthalene can induce the orientation and rearrangement of polymers25,26. Additionally, crystallization-related phase transitions can also be found in liquid crystal (LC) materials27,28,29,30, which have attracted considerable interest because of their wide practical applications in displays, innovative sensors, and digital nonvolatile memory devices. These results indicate that studies on the crystallization and phase transitions corresponding to the molecular orientation of organic materials are essential. Presently, the molecular orientation in crystallization and phase transition is widely characterized by X-ray diffraction (XRD). However, the XRD technique cannot effectively identify light atoms such as C, H and O, which are the dominant components in molecular materials. Thus, exploring other methods to probe the molecular orientation more precisely is vital.

Herein, we selected the aforementioned functional organic materials, including 1-chloronaphthalene and a liquid crystal material of 4-cyano-4′-pentyl-biphenyl (5CB), to explore the spin-sensing function of Y2@C79N for the crystallization behavior and phase transitions of aromatic materials. For comparison, X-ray diffraction (XRD) and polarized-light optical microscopy (POM) imaging were employed to illustrate the relationship between the spin signals and compound crystallization. These results reveal that the Y2@C79N spin can be developed as a molecular spin sensor to monitor the phase transition of aromatic materials in situ and in real time.

Results

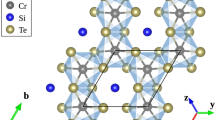

Aza-metallofullerene Y2@C79N, in which one carbon atom of the cage is substituted with a nitrogen atom, has an electron spin localized on the internal Y2 cluster (Fig. 1a, b). In solution, Y2@C79N shows three distinct groups of EPR signals owing to the hyperfine couplings between the spin and the two Y nuclei (IY = 1/2). Notably, the orientation of Y2@C79N in solution is disordered. However, the selective orientation of Y2@C79N can be achieved by encapsulating it within the pores that contain phenyl groups. Our previous findings reveal the characteristic orientation of Y2@C79N in aromatic materials containing phenyl groups. This orientation is facilitated by π–π interactions between the N-substituted region of the fullerene cage and the benzene unit (Fig. 1c). The crystallization of selected organic materials (1-chloronaphthalene and 5CB) with benzene rings formed an ordered array, which could also induce the Y2@C79N orientation (Fig. 1d).

a DFT-optimized molecular structure of Y2@C79N at the level of B3LYP/6-31 G* ~ LANL2DZ for Y. (Nitrogen atom, carbon atoms and yttrium atoms are respectively colored in indigo, blue, and rose-red spheres.). b Calculated spin density distributions (orange) of Y2@C79N. c Schematic of the interaction between the N-substituted region in C79N cage and benzene ring. d Schematic of the orientation of Y2@C79N in crystalline aromatic materials.

First, 1-chloronaphthalene, an aromatic compound with a melting point of 253 K, was employed to dissolve Y2@C79N, and the temperature-dependent EPR spectra were collected to study the crystallization-induced Y2@C79N orientation and spin sensing (Fig. 2a). Subsequently, we measured the EPR signals of Y2@C79N in 1-chloronaphthalene from 290 to 90 K (Fig. 2b). EPR spectra were recorded using an EPR spectrometer (CIQTEK EPR200-Plus) with a continuous-wave X-band frequency. The signal intensity and linewidth changes under varied temperatures were analyzed, and the changes for three groups of EPR signals were made respectively (Fig. S2). From 290 to 245 K, the signal intensity for the EPR signals at central and high magnetic field gradually increased owing to weakened spin–lattice interactions; it reached its peak at 245 K. From 245 to 230 K, the signal intensity began to decrease because of the restricted motion of Y2@C79N owing to the coagulation of 1-chloronaphthalene.

a Schematic diagram of Y2@C79N in the disordered and ordered matrix of 1-chloronaphthalene. b Temperature-dependent EPR spectra of Y2@C79N in 1-chloronaphthalene ranging from 290 to 90 K. The EPR measurement frequency is 9.7033 GHz, the continuous-wave power is 0.63 mW, the intensity is 25 dB, modulation amplitude is 2 G, and scan number is two. c Linewidth changes for the EPR signals of Y2@C79N in 1-chloronaphthalene under varied temperatures from 290 to 230 K. T1 and T2 denote the transition temperatures of 245 and 230 K, respectively. d Experimental EPR spectrum of Y2@C79N in 1-chloronaphthalene measured at 130 K, and correspondingly simulated EPR spectrum. e In-situ temperature-dependent XRD characterizations on 1-chloronaphthalene under varied temperatures. f In-situ polarized-light optical microscope (POM) images of 1-chloronaphthalene under varied temperatures.

From 290 to 230 K, the intensity of the EPR signal at a high magnetic field has a higher enhancement than that at a low magnetic field owing to paramagnetic anisotropy. This is because the two Y nuclei and spin have restricted motion at low temperatures; consequently, insufficient rotational averaging occurs in the resonance structure. Notably, a new group of EPR signals was observed at 225 K. According to our previous EPR studies on Y2@C79N, this new group of EPR signals can be ascribed to the axisymmetric EPR signals, which are caused by the orientation of Y2@C79N in 1-chloronaphthalene. The intensity of this axisymmetric group of EPR signals gradually increased when the temperature was decreased to 90 K. These results show that at low temperatures, Y2@C79N orientates more in 1-chloronaphthalene.

The linewidths of the EPR signals were analyzed to determine the motion states of Y2@C79N in 1-chloronaphthalene at varied temperatures. Generally, the linewidth of an EPR signal is related to the rotation of the spin molecule. Figure 2c shows the linewidth changes for the EPR signals of Y2@C79N in 1-chloronaphthalene at temperatures ranging from 290 to 230 K. For Y2@C79N in 1-chloronaphthalene, the linewidths of the EPR signals have a minimum value at 250 K. From 245 to 230 K, the linewidths of the EPR signals began increasing because of the restricted motion of Y2@C79N owing to the coagulation of 1-chloronaphthalene and restricted motion of Y2@C79N. As mentioned above, the signal intensity of Y2@C79N in 1-chloronaphthalene reached its peak at 245 K (Fig. S2), and the signal intensity begins to decrease below 245 K owing to the coagulation of 1-chloronaphthalene. These results reveal that the evolution of signal intensity and linewidth can well reflect the temperature-dependent spin relaxation processes. These results indicate that the spin of Y2@C79N can effectively sense the coagulation of 1-chloronaphthalene. Furthermore, this transition point is slightly lower than the standard melting point of 1-chloronaphthalene (253 K), and this difference could be caused by the doping of metallofullerene.

In addition, the linewidths for the EPR signals of Y2@C79N in 1-chloronaphthalene show a dramatic rise at 230 K, below which Y2@C79N in 1-chloronaphthalene shows axisymmetric EPR signals. When the temperature was decreased to 225 K, Y2@C79N in 1-chloronaphthalene clearly showed a new group of axisymmetric EPR signals. Moreover, from 225 K to 90 K, the intensity of the axisymmetric EPR signals gradually increased. This type of axisymmetric EPR signals was observed in Y2@C79N⊂MOF-177 complex below 253 K11 as well as Y2@C79N⊂[4]CHBC complex below 298 K18. As reported previously, the axisymmetric EPR signals revealed Y2@C79N orientation in matrix. Moreover, as noted earlier, 1-chloronaphthalene is often used as a solvent additive for solar cells because it induces a short-range regular arrangement of the polymers owing to crystallization. Therefore, we propose that the Y2@C79N in 1-chloronaphthalene below 230 K also has a crystallization-induced orientation.

The EPR spectra of Y2@C79N in 1-chloronaphthalene were simulated to obtain the hyperfine coupling constants (a) and g-factors. The simulated EPR spectra were obtained using the Easyspin package, encoded on MATLAB. Figure 2d shows the experimental EPR spectrum of Y2@C79N in 1-chloronaphthalene measured at 130 K, and the corresponding simulated EPR spectrum with parameters of a⊥= 80.36 G, a//= 92.86 G, g⊥= 1.955, and g//= 1.993. The simulated EPR spectrum exhibited axisymmetric parameters, further demonstrating the orientation of Y2@C79N in 1-chloronaphthalene.

For comparison, temperature-dependent EPR spectra of Y2@C79N in a non-aromatic solvent of CS2 were measured, as shown in Fig. S2. From 290 to 170 K, the intensity of EPR signals of Y2@C79N in CS2 increased due to the weakened spin-lattice interaction at low temperature. In addition, the EPR spectra showed anisotropic characteristics due to the insufficient rotational averaging of the g and hyperfine tensors. Below 150 K, Y2@C79N in CS2 showed seriously broadened EPR signals due to the coagulation of CS2 solvent. These results reveal that Y2@C79N in CS2 under low temperature could only sense the melting point of CS2 solvent, but would not show orientation in coagulated CS2.

We performed in-situ temperature-dependent XRD characterizations of 1-chloronaphthalene (Fig. 2d) to further investigate the relationship between the EPR signals and compound crystallization. In-situ XRD is an experimental method useful for detecting material crystallization. We found that 1-chloronaphthalene shows distinct diffraction peaks at 230 K, indicating the beginning of compound crystallization. Notably, the crystallization temperature of 1-chloronaphthalene obtained by XRD is close to the transition point of the EPR signals of Y2@C79N. These results further demonstrate the relationship between the EPR signals of Y2@C79N and compound crystallization.

Moreover, polarized light optical microscopy (POM) was used to characterize the crystallization of 1-chloronaphthalene at various temperatures (Fig. 2e). The crystal morphology was first observed at 233 K for 1-chloronaphthalene, indicating the beginning of compound crystallization. This transition temperature at the beginning of the compound crystallization is also close to the transition point for the EPR signals of Y2@C79N at 230 K. In addition, when the temperature was further decreased, 1-chloronaphthalene showed a more obvious crystal morphology, indicating that it crystallizes better at low temperatures. These POM imaging results are consistent with EPR data, where Y2@C79N shows more prominent axisymmetric signals at low temperatures.

Table 1 lists the temperature transition points of melting and crystalline states for 1-chloronaphthalene obtained by EPR, XRD, and POM. These results further confirm the relationship between the EPR signals of Y2@C79N and compound crystallization. Additionally, these results show that the spin of Y2@C79N is sensitive to compound crystallization, demonstrating its potential application as a molecular spin sensor.

Based on these results, the Y2@C79N spin was employed to sense the phase transitions in crystallization process of a liquid crystal material 5CB (Fig. 3a). Liquid-crystal (LC) materials have attracted considerable research interest owing to their promising practical applications in displays, flat panels, innovative sensors, and digital nonvolatile memory devices. 5CB belongs to a class of thermotropic liquid crystals, and is one of the most widely studied liquid crystal materials27,31,32,33,34,35,36,37,38,39,40,41,42,43. It has been established that 5CB has an isotropic-nematic transition temperature of approximately 308 K and a nematic-crystalline transition temperature of approximately 297 K. Thus, we measured the temperature-dependent EPR signals of Y2@C79N dissolved in 5CB at temperatures ranging from 320 to 130 K (Figs. 3b and S3).

a Schematic diagram of Y2@C79N in 5CB from nematic to crystalline states. 5CB molecules are colored green. b Temperature-dependent EPR spectra of Y2@C79N in 5CB ranging from 320 to 130 K. The EPR measurement frequency is 9.5399 GHz, continuous-wave power is 0.63 mW, intensity is 25 dB, modulation amplitude is 3 G, and scan number is three. c Temperature dependence of the linewidth of EPR signals for Y2@C79N in 5CB. T1 and T2 denote the transition temperatures of 290 and 270 K, respectively. d Experimental EPR spectrum of Y2@C79N in 5CB measured at 230 K, and correspondingly simulated EPR spectrum. e Experimental EPR spectrum of Y2@C79N in 5CB measured at 130 K, and correspondingly simulated EPR spectrum. f Temperature-dependent XRD characterizations on 5CB. g Temperature-dependent polarized-light optical microscopy images of 5CB.

For EPR studies, Y2@C79N in 5CB shows three groups of EPR signals with higher signal intensity at high field than at low field between 320 and 290 K. This reveals the anisotropic EPR spectra resulting from the restricted motion of Y2@C79N in the nematic phase of 5CB. As shown in Fig. S2, from 320 to 290 K, the EPR signal intensity for the EPR signals at central and high magnetic field reached its peak at 290 K owing to the weakened spin–lattice interaction at low temperatures. Notably, the EPR signal intensity of Y2@C79N in 5CB decreased below 290 K. According to the literature, the nematic-crystalline phase transition of 5CB occurs at ~297 K, below which the 5CB begins to crystallize. Therefore, it can be deduced that below 290 K, the spin–lattice interaction for Y2@C79N in crystalline 5CB would intensify due to the crystallization of 5CB.

The temperature-dependent linewidths of the EPR signals of Y2@C79N in 5CB were then analyzed. Figure 3c shows the temperature dependence of linewidths for the EPR signals at varied temperatures. For Y2@C79N in 5CB, the linewidths of the EPR signals have a minimum value at 295 K. The linewidths of all EPR signals gradually decrease when the temperature decreases from 320 to 295 K owing to the weakened spin–lattice interactions of Y2@C79N in nematic 5CB at low temperatures. From 290 K, the linewidths of the EPR signals began to increase when the temperature decreased. It has been established that 5CB has a nematic-crystalline transition temperature of approximately 297 K. Therefore, these results demonstrate the relationship between the EPR signals of Y2@C79N and 5CB crystallization. When the temperature was decreased to 270 K, the linewidths for the EPR signals of Y2@C79N in 5CB show a dramatic rise. From 270 to 230 K, it can be observed that Y2@C79N in 5CB exhibited similar axisymmetric EPR signals. The EPR spectra of Y2@C79N in 5CB were simulated to obtain the hyperfine coupling constants and g-factors, and Fig. 3d shows the experimental and simulated EPR spectra of Y2@C79N in 5CB measured at 230 K. These results reveal that Y2@C79N in crystalline 5CB begins to show orientation from 270 K. It also can be observed that from 270 to 230 K the intensity of the EPR signals gradually decreased, revealing the restricted motion of Y2@C79N in crystalline 5CB.

When the temperature was decreased to 225 K, Y2@C79N in 5CB clearly showed a new group of axisymmetric EPR signals, and this type of axisymmetric EPR signals demonstrates the further orientation of Y2@C79N in crystalline 5CB. Therefore, this type of axisymmetric EPR signals reveal another crystalline phase of 5CB below 225 K. Moreover, from 225 K to 130 K, the intensity of these EPR signals gradually increased, revealing the further orientation of Y2@C79N in crystalline 5CB as the temperature drops lower. These results show that the complete orientation of Y2@C79N in 5CB matrix is highly related to the low temperature, which could restrict the motion of Y2@C79N. Figure 3e shows the experimental EPR spectrum of Y2@C79N in 5CB measured at 130 K, and the corresponding simulated EPR spectrum with parameters of a⊥= 78.21 G, a//= 92.14 G, g⊥= 1.952, and g//= 1.993. The simulated EPR spectrum exhibited axisymmetric parameters, further demonstrating the orientation of Y2@C79N in crystalline 5CB.

To further investigate the relationship between the EPR signals and 5CB crystallization, we performed in-situ temperature-dependent XRD characterization of 5CB from 300 to 240 K (Fig. 3f). 5CB exhibits distinct XRD peaks at 270 K, revealing that 5CB crystallizes at this point. Notably, the axisymmetric EPR signals for Y2@C79N in 5CB were also clearly observed at 270 K. These results further demonstrated the crystallization-induced Y2@C79N orientation in the crystalline phase of 5CB. Additionally, from 270 to 240 K, the XRD patterns of 5CB showed similar peaks without variations in the EPR spectra. POM was used to characterize the crystallization of 5CB at various temperatures (Fig. 3g). A crystal morphology was discovered at approximately 308 K for 5CB, revealing its nematic phase. From 308 to 260 K, the POM images of 5CB were similar. From 255 K, the POM images of 5CB show a changed crystal morphology, indicating a change in the crystalline phase.

Temperature-dependent phase transitions of 5CB have been reported using several methods, such as differential scanning calorimetry (DSC), fluorescence spectroscopy, X-ray diffraction, Raman spectroscopy, and proton nuclear magnetic resonance (NMR)31,32,33,34,35,36,37,38,39,40,41,42,43,44. Table 2 lists the temperature transition points of 5CB in different crystalline states obtained by DSC, EPR, XRD, and POM. The DSC method was employed to systematically study the phase transitions of 5CB, which showed repeated transition points. In the DSC results, the exothermic peak at approximately 260 K can be attributed to the transition from the C2 crystalline phase to the metastable C1b phase. Additionally, the exothermic peak at approximately 230 K can be attributed to the transition from the metastable C1b crystalline phase to the C1a phase. The XRD and POM results for 5CB show distinct XRD peaks at 270 K and a change in crystal morphology at 255 K, respectively, which can be attributed to the transition from the C2 crystalline phase to the metastable C1b phase. However, the transition from the metastable C1b crystalline phase to the C1a phase was not observed in the XRD or POM results. Notably, two marked changes in the EPR results were observed at 270 and 225 K, which are consistent with the two corresponding phase transition points in the DSC results. For the DSC thermograms of 5CB measured in heating mode, two exothermal peaks were observed at 230 and 260 K, corresponding to two crystalline phase transition points35. However, for the DSC thermograms of 5CB measured in cooling mode, only one peak at 260 K was clearly observed44. For the EPR results of Y2@C79N in 5CB, these two crystalline phase transition points can be clearly observed both in cooling and heating modes. These results show that the spin of Y2@C79N is more sensitive to 5CB crystallization, demonstrating its potential for application as a molecular spin sensor.

Density functional theory (DFT) calculations were performed to further analyze the orientation of Y2@C79N in crystalline 5CB. As illustrated in Fig. 4a–d, we assessed the thermodynamic stability of the four typical sites of Y2@C79N within the 5CB crystal lattice. The most favorable structure was obtained when the nitrogen atom of Y2@C79N is positioned near a benzene ring of 5CB, which connects to the cyano-group, as shown in Fig. 4a, e. In addition, the two Y atoms are in proximity to the 5CB benzene rings as well.

a–d Four typical conformations of Y2@C79N in crystalline 5CB and their relative energies. e Local structure diagram for the most favorable structure of Y2@C79N in crystalline 5CB. f Molecular dynamics simulation (1000 ps) of Y2@C79N in crystalline 5CB and statistical analyses of the distance changes between the nitrogen atom in Y2@C79N and the benzene ring center in 5CB. Letter d in inset denotes the distance between the nitrogen atom in Y2@C79N and the benzene ring center in 5CB.

Concurrently, molecular dynamics (MD) simulations were employed to statistically analyze the changed distances (d) between the nitrogen atom on the carbon cage and the center of a benzene ring in 5CB. For initial conformation, the nitrogen atom was placed at a distance (d) far away from the center of the benzene ring of 5CB (approximately 9.2 Å). Following MD simulations, the distance (d) between the nitrogen atom and the center of the benzene rings stabilizes at an average of 3.44 Å finally (Fig. 4e). These results suggest that Y2@C79N exhibits distinct orientation characteristics in crystalline 5CB. During the MD simulations, the nitrogen atom from the fullerene consistently interacted with the benzene ring connecting CN group, leading to a stable orientation. On the whole, the stable Y2@C79N-5CB structures observed in the MD simulations are similar to the optimized structures found by DFT, as shown in the amplified structures in Fig. 4a, e. The slight difference is the N-benzene distance. For the structures observed in the MD, the N-benzene distance is around 3.44 Å, which is 3.16 Å in the DFT calculation. The differences of the N-benzene distance may arise from the different calculation methods. MD method includes empirical van der Waals terms and thermal fluctuations, which can slightly increase the distance.

Discussion

This study reported a molecular spin senor of metallofullerene Y2@C79N for in-situ monitoring of the crystallization behavior and phase transition in aromatic materials. Two functional aromatic materials, including 1-chloronaphthalene and a liquid crystal material of 5CB, were selected to illustrate this spin-sensing function of Y2@C79N. Temperature-dependent EPR results of Y2@C79N dissolved in these two aromatic materials were analyzed. The EPR results indicated that Y2@C79N in 1-chloronaphthalene exhibits two distinct changes for EPR signals at 245 and 230 K, which correspond to the melting and crystallization points of 1-chloronaphthalene, respectively. For Y2@C79N in a liquid crystal of 5CB, it exhibits three distinct changes for EPR signals at 290, 270, and 225 K, corresponding to the nematic-crystalline transition, C2 crystalline to metastable C1b crystalline phase transition, and metastable C1b crystalline to the C1a crystalline phase transition. These results show that the spin of Y2@C79N can sense the crystallization-related phase transitions of these aromatic materials. In addition, Y2@C79N dissolved in these aromatic materials exhibited EPR signals that changed from isotropic to axisymmetric patterns below their crystallization points owing to the orientation of Y2@C79N in these crystalline materials.

Moreover, Y2@C79N was found to be capable of sensing most phase changes of a liquid crystal material of 5CB at 290, 270, and 225 K. Conversely, the XRD method can only detect one phase transition at 270 K. XRD, a common method for characterizing orientation, struggles to detect light atoms like C, H, and O In addition, for the DSC thermograms of 5CB measured in heating mode, three peaks were observed at 230 and 260 and 297 K, corresponding to three crystalline phase transition points. However, for the DSC thermograms of 5CB measured in cooling mode, only one peak at 260 K was clearly observed, revealing the somewhat deficiency of the DSC method.

In order to clarify the applicability scope of this molecular spin sensor, temperature-dependent EPR spectra of Y2@C79N in a non-aromatic solvent of CS2 were measured for comparison, and the EPR results revealed that Y2@C79N in CS2 would not show orientation in coagulated CS2. Therefore, Y2@C79N could not be capable of sensing the crystallization behavior of non-aromatic materials, revealing the specific application scope of this molecular spin sensor.

This susceptible spin character of aza-metallofullerene Y2@C79N has potential applications for monitoring the crystallization behavior and phase transitions of certain aromatic materials with high precision. In particular, this molecular spin probe can penetrate into the crystal lattice of aromatic materials and reflect the phase transitions in situ. Compared to the well-known spin probes of NV colour centers in diamond, this molecular spin probe based on metallofullerenes can be embedded to the crystal lattice, channels of organic framework materials and cavities of molecular nanorings, to realize spin sensing applications on the molecular scale in situ. In addition, compared to the classical spin probes of nitroxide radicals, this molecular spin probe based on metallofullerenes has high thermal stability and specific sensitivity for aromatic systems. Therefore, these studies of molecular spin systems based on metallofullerenes could be developed into a transformative technology in the future.

Methods

Synthesis, isolation and characterizations of Y2@C79N

Metallofullerene Y2@C79N was synthesized by the arc-discharge method. Briefly, Y/Ni2 alloy and graphite powder were mixed in a mass ratio of 3:1 and filled into the hollow graphite rod. The furnace was vacuumed and filled with 190 Torr He and 10 Torr N2. Then the graphite rods were evaporated in a DC arc discharge furnace with a current of 130 A to get the carbon soot containing various fullerenes and metallofullerenes. The carbon soot was subjected to Soxhlet extraction in toluene for 12 h. Y2@C79N was isolated and purified by multi-step high performance liquid chromatography (HPLC) on Buckyprep and Buckyprep-M columns (20 mm × 250 mm) with toluene as the mobile phase. The purity of Y2@C79N was determined by matrix-assisted laser desorption/ionization time-of-flight mass spectrometry (MALDI-TOF-MS, AXIMA Assurance, Shimadzu).

XRD measurements

The PANalytical Empyrean X-ray diffractometer was employed for the characterization of samples. A volume of 100 μL of the solvent was placed in a custom-designed sample cell and positioned on the sample stage for analysis. To achieve temperature control, a low-temperature nitrogen gas was used to establish an equilibrium atmosphere. A temperature probe was positioned in close proximity to the sample surface to monitor the environmental temperature. Spectra were acquired for each sample at different temperatures, with a stabilization period of ten minutes at each temperature.

POM measurements

An Olympus BX51 polarized-light optical microscope (POM) equipped with a charge-coupled device (CCD) digital camera and a Linkam THMS-600 heating stage was used to detect the crystallization of 1-chloronaphthalene and 5CB. The sample (3 μL) was putted in the middle of two slides. The sample was cooled at a rate of 5 K/min.

EPR measurements

EPR spectra were recorded on an EPR spectrometer (CIQTEK EPR200-Plus) with a continuous-wave X-band frequency (~9.7 GHz). Y₂@C₇₉N was completely dissolved in 1-chloronaphthalene and 5CB at a concentration of 3.5 × 10⁻⁴ M, ensuring thorough dissolution and uniform dispersion of the metallofullerene molecules. Then, transfer 80 μL of the solution to the bottom of a quartz tube. To probe the phase transition of aromatic materials using the molecular spin of Y2@C79N, the Variable-temperature EPR signals were recorded. Variable-temperature EPR experiments were conducted using the EPR200-Plus electron paramagnetic resonance spectrometer equipped with a liquid nitrogen cooling system to achieve low temperatures. Each temperature was maintained for 15 min to ensure that the actual sample temperature equilibrated with the temperature detected by the sensor. Subsequently, the EPR signals were recorded. The detailed test procedure is described in Supplementary Information.

Statistical Information

Statistics were performed with OriginPro 2021 software.

Calculation methods

Geometric optimization of Y2@C79N was performed without symmetry constraints at the theory level of B3LYP/6-31 G* (LANL2DZ basis for Y) using Gaussian 09 program with the inclusion of considering the dispersion corrections. The schematic diagrams in Figs. 1, 2a, 3a and Supplementary Fig. 3a were all generated from calculation software of Materials studio 2019.

The calculations of Y2@C79N/5CB complex were performed using the Vienna ab initio simulation package (VASP)45,46,47, and the Perdew-Burke-Ernzerhof form of the generalized gradient approximation (GGA-PBE)48 functional was employed to obtain the exchange and correlation terms. The optimization was performed with an energy cutoff of 520 eV, using a k-mesh of 1 x 1 x 1 and achieving energy and force convergence of 1 × 10−5 eV and 0.02 eV/Å, respectively. The selection of the four sites is based on the orientations of the nitrogen atom and the internal metal Y clusters referring to correlative references17,18,19,20. Specifically, the following configurations were considered: (1) The N-atom in cage is close to a benzene ring of 5CB or away from it; (2) The two Y-atoms is close to the benzene rings of 5CB or away from them. Consequently, four representative configurations were selected and optimized.

Molecular dynamics simulations were conducted utilizing the GROMACS simulation package, version 2022.449. The simulations were executed for a duration of 1000 ps, with an integration time step precisely set to 0.001 ps. Each simulation was carried out at an isothermal condition, with the temperature rigorously maintained at a constant value of 300 K. To achieve temperature coupling, the v-rescale algorithm was employed50. Throughout all simulations, periodic boundary conditions were consistently applied in the three-dimensional space. The cutoff distance for nonbonded interactions was established at 1.0 nm. For the treatment of long-range electrostatic interactions, the particle mesh Ewald (PME) method was implemented51. The simulations were facilitated by the Universal Force Field (UFF)52, which provided the force field parameters. For the images of Fig. 4, visualization of molecular structures and dynamics results were generated from software of VESTA (ver.3.9) and VMD (ver.1.9.4).

Data availability

All the data supporting the findings of this study are available within this article and its Supplementary Information and Source Data file. Any additional information can be requested from corresponding author. Source data are provided with this paper.

References

Bayer, M. All for one and one for all. Science 364, 30–31 (2019).

Gaita-Ariño, A., Luis, F., Hill, S. & Coronado, E. Molecular spins for quantum computation. Nat. Chem. 11, 301–309 (2019).

Laorenza, D. W. & Freedman, D. E. Could the quantum internet be comprised of molecular spins with tunable optical interfaces. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 144, 21810–21825 (2022).

Moreno-Pineda, E., Godfrin, C., Balestro, F., Wernsdorfer, W. & Ruben, M. Molecular spin qudits for quantum algorithms. Chem. Soc. Rev. 47, 501–513 (2018).

Troiani, F., Ghirri, A., Paris, M. G. A., Bonizzoni, C. & Affronte, M. Towards quantum sensing with molecular spins. J. Magn. Magn. Mater. 491, 165534 (2019).

Bloom, B. P., Paltiel, Y., Naaman, R. & Waldeck, D. H. Chiral induced spin selectivity. Chem. Rev. 124, 1950–1991 (2024).

Bousseksou, A., Molnár, G., Salmon, L. & Nicolazzi, W. Molecular spin crossover phenomenon: recent achievements and prospects. Chem. Soc. Rev. 40, 3313–3335 (2011).

Du, J. F., Shi, F. Z., Kong, X., Jelezko, F. & Wrachtrup, J. Single-molecule scale magnetic resonance spectroscopy using quantum diamond sensors. Rev. Mod. Phys. 96, 025001 (2024).

Tang, S. X. & Wang, X. P. Spin frustration in organic radicals. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 136, e202310147 (2024).

Wang, T. S. & Wang, C. R. Endohedral metallofullerenes based on spherical Ih‑C80 cage: molecular structures and paramagnetic properties. Acc. Chem. Res. 47, 450–458 (2014).

Feng, Y. et al. Steering metallofullerene electron spin in porous metal–organic framework. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 137, 15055–15060 (2015).

Zhang, J. et al. Embedded nano spin sensor for in situ probing of gas adsorption inside porous organic frameworks. Nat. Commun. 14, 4922 (2023).

Gil-Ramírez, G. et al. Distance measurement of a noncovalently bound Y@C82 pair with double electron electron resonance spectroscopy. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 140, 7420–7424 (2018).

Hu, Z. et al. Endohedral metallofullerene as molecular high spin qubit: diverse Rabi cycles in Gd2@C79N. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 140, 1123–1130 (2018).

Ma, Y. et al. Susceptible electron spin adhering to an yttrium cluster inside an azafullerene C79. N. Chem. Commun. 48, 11570–11572 (2012).

Zuo, T. et al. M2@C79N (M = Y, Tb): isolation and characterization of stable endohedral metallofullerenes exhibiting M−M bonding interactions inside Aza[80]fullerene cages. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 130, 12992–12997 (2008).

Lu, Y. et al. Enhanced spin-nuclei couplings of paramagnetic azametallofullerene hooped in cycloparaphenylene. J. Phys. Chem. C. 127, 4660–4664 (2023).

Zhao, C. et al. Construction of a short metallofullerene-peapod with a spin probe. Chem. Commun. 55, 11511–11514 (2019).

Zhao, C. et al. Anisotropic paramagnetic properties of metallofullerene confined in a metal–organic framework. J. Phys. Chem. C. 122, 4635–4640 (2018).

Zhao, C. et al. Supramolecular complexes of C80-based metallofullerenes with [12]cycloparaphenylene nanoring and altered property in a confined space. J. Phys. Chem. C. 123, 12514–12520 (2019).

Khasbaatar, A. et al. From solution to thin film: molecular assembly of π-conjugated systems and impact on (opto)electronic properties. Chem. Rev. 123, 8395–8487 (2023).

Zhang, W., Mazzarello, R., Wuttig, M. & Ma, E. Designing crystallization in phase-change materials for universal memory and neuro-inspired computing. Nat. Rev. Mater. 4, 150–168 (2019).

Usman, A., Xiong, F., Aftab, W., Qin, M. & Zou, R. Emerging solid-to-solid phase-change materials for thermal-energy harvesting, storage, and utilization. Adv. Mater. 34, 2202457 (2022).

Lehmann, M., Dechant, M., Lambov, M. & Ghosh, T. Free space in liquid crystals—molecular design, generation, and usage. Acc. Chem. Res. 52, 1653–1664 (2019).

Yao, Z. F. et al. Ordered solid-state microstructures of conjugated polymers arising from solution-state aggregation. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 59, 17467–17471 (2020).

Lv, J. et al. Additive-induced miscibility regulation and hierarchical morphology enable 17.5% binary organic solar cells. Energy Environ. Sci. 14, 3044–3052 (2021).

Sadati, M. et al. Molecular structure of canonical liquid crystal interfaces. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 139, 3841–3850 (2017).

Sidky, H., de Pablo, J. J. & Whitmer, J. K. Measurement of elastic moduli of nematic liquid crystals. Phys. Rev. Lett. 120, 107801 (2018).

Tran, L. et al. Lassoing saddle splay and the geometrical control of topological defects. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 113, 7106–7111 (2016).

Uchida, J., Soberats, B., Gupta, M. & Kato, T. Advanced functional liquid crystals. Adv. Mater. 34, 2270171 (2022).

Bezrodna, T., Melnyk, V., Vorobjev, V. & Puchkovska, G. Low-temperature photoluminescence of 5CB liquid crystal. J. Lumin. 130, 1134–1141 (2010).

Brown, P. A., Fischer, S. A., Kołacz, J., Spillmann, C. & Gunlycke, D. Thermotropic liquid crystal (5CB) on two-dimensional materials. Phys. Rev. E 100, 062701 (2019).

Devadiga, D. & Ahipa, T. N. A review on the emerging applications of 4-cyano-4′-alkylbiphenyl (nCB) liquid crystals beyond display. Mater. Sci. Eng. B 275, 115522 (2022).

Grigoriadis, C. et al. Suppression of phase transitions in a confined rodlike liquid crystal. ACS Nano 5, 9208–9215 (2011).

Klishevich, G. V., Kurmei, N. D., Melnik, V. I. & Tereshchenko, A. G. Temperature dependence of the luminescence spectra of a 5CB liquid crystal and its phase transitions. J. Appl. Spectrosc. 85, 904–908 (2018).

Lebovka, N. et al. Low-temperature phase transformations in 4-cyano-4′-pentyl-biphenyl (5CB) filled by multiwalled carbon nanotubes. Phys. E Low. Dimens. Syst. Nanostruct. 52, 65–69 (2013).

Noble, A. R., Kwon, H. J. & Nuzzo, R. G. Effects of surface morphology on the anchoring and electrooptical dynamics of confined nanoscale liquid crystalline films. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 124, 15020–15029 (2002).

Noble-Luginbuhl, A. R., Blanchard, R. M. & Nuzzo, R. G. Surface effects on the dynamics of liquid crystalline thin films confined in nanoscale cavities. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 122, 3917–3926 (2000).

Oladepo, S. A. Temperature-dependent fluorescence emission of 4-cyano-4′-pentylbiphenyl and 4-cyano-4′-hexylbiphenyl liquid crystals and their bulk phase transitions. J. Mol. Liq. 323, 114590 (2021).

Porter, D., Savage, J. R., Cohen, I., Spicer, P. & Caggioni, M. Temperature dependence of droplet breakup in 8CB and 5CB liquid crystals. Phys. Rev. E 85, 041701 (2012).

Sandström, D. & Levitt, M. H. Structure and molecular ordering of a nematic liquid crystal studied by natural-abundance double-quantum 13C NMR. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 118, 6966–6974 (1996).

Smart, C. L., Cortese, A. J., Ramshaw, B. J. & McEuen, P. L. Nanocalorimetry using microscopic optical wireless integrated circuits. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 119, e2205322119 (2022).

Zhang, J., Su, J. & Guo, H. An atomistic simulation for 4-Cyano-4′-pentylbiphenyl and its homologue with a reoptimized force field. J. Phys. Chem. B 115, 2214–2227 (2011).

Mansaré, T., Decressain, R., Gors, C., Dolganov, V. K. J. M. C. & Crystals, L. Phase transformations and dynamics of 4-cyano-4′-pentylbiphenyl (5CB) by nuclear magnetic resonance, analysis differential scanning calorimetry, and wideangle X-ray diffraction analysis. Mol. Cryst. Liq. Cryst. 382, 111–197 (2002).

Kresse, G. & Furthmüller, J. Efficiency of ab-initio total energy calculations for metals and semiconductors using a plane-wave basis set. Comput. Mater. Sci. 6, 15–50 (1996).

Kresse, G. & Furthmüller, J. Efficient iterative schemes for ab initio total-energy calculations using a plane-wave basis set. Phys. Rev. B 54, 11169–11186 (1996).

Kresse, G. & Hafner, J. Ab initio molecular dynamics for liquid metals. Phys. Rev. B 47, 558–561 (1993).

Perdew, J. P., Burke, K. & Ernzerhof, M. Generalized gradient approximation made simple. Phys. Rev. Lett. 77, 3865–3868 (1996).

Abraham, M. J. et al. GROMACS: high performance molecular simulations through multi-level parallelism from laptops to supercomputers. SoftwareX 1-2, 19–25 (2015).

Bussi, G., Donadio, D. & Parrinello, M. Canonical sampling through velocity rescaling. J. Chem. Phys. 126, 014101 (2007).

Essmann, U. et al. A smooth particle mesh Ewald method. J. Chem. Phys. 103, 8577–8593 (1995).

Rappé, A. K., Casewit, C. J., Colwell, K., Goddard, W. A. III & Skiff, W. M. UFF, a full periodic table force field for molecular mechanics and molecular dynamics simulations. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 114, 10024–10035 (1992).

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (52472041, 52022098) and the Beijing National Laboratory for Condensed Matter Physics (2023BNLCMPKF004). C.Z. thanks the Guizhou Provincial Science and Technology Projects (ZK[2022]402). We also thank the Analysis & Testing Center, BIT.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

T.W. conceived the research and supervised the project. L.L. and Y.Z. performed the material preparations and magnetic measurements. C.Z. and Z.Z. performed the DFT calculations. C.W. gave advice and guidance. All authors discussed the results and commented on the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Peer review

Peer review information

Nature Communications thanks Shangfeng Yang and the other anonymous reviewer(s) for their contribution to the peer review of this work. A peer review file is available.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Source data

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Liu, L., Zhao, C., Zhang, Y. et al. Molecular spin sensor for in-situ monitoring of crystallization behavior and phase transition in aromatic materials. Nat Commun 16, 7170 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-025-62649-2

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-025-62649-2