Abstract

Earth’s inner core consists of iron (Fe) alloyed with minor light elements, predominantly silicon (Si), yet the crystal structure and seismic velocities of Fe-Si alloys at inner-core conditions remain poorly constrained. Ab-initio methods struggle with the alloy’s vast configurational complexity, limiting reliable property predictions. To overcome this, here we integrate a hybrid Monte Carlo sampling algorithm with a deep-learning interatomic potential to compute the Fe-Si binary phase diagram and sound velocities at inner-core boundary pressures. A complex phase diagram emerges, featuring the re-entrance of a body-centered cubic (bcc) phase stabilized by pronounced short-range ordering of the Si atoms. The bcc phase reproduces key seismic features of the inner core, including low shear-wave velocities and seismic anisotropy, more faithfully than other competing close-packed structures, making it a leading candidate for the inner-core structure. Our results underscore the importance of accurately describing light-element effects on Earth’s core properties.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Earth’s core is composed primarily of iron (Fe) alloyed with small amounts of nickel (Ni) and of light elements such as Si, S, O, C, and H1,2. Despite their low abundance, light elements play a crucial role in determining the properties of the alloy and in explaining geophysical observations of core density and seismic wave velocities, as well as in the understanding of Earth’s accretion and core formation processes1,2. While the properties of the alloy end-member, pure Fe, at the extreme conditions of pressure and temperature of the Earth’s core, are reasonably well understood3,4,5, phase relations for more realistic compositions for the core are subject to considerable uncertainty even in the case of binary systems, due to intrinsic difficulties in reproducing the relevant conditions of pressure and temperature in the laboratory2. Ab-initio atomistic simulations have provided important contributions to our understanding of the Earth’s core6,7,8, but attempts to determine phase relations in core-forming alloys with ab-initio methods are hindered by the large amount of calculations required to sample atomic configurational disorder in solid solutions at high temperature9,10. It has been recently pointed out that even slight departures from a totally random distribution of the elements in the lattice can affect the properties of solid solutions significantly, and that these departures can now be theoretically quantified with ab-initio accuracy11.

The relative concentration of light elements in the Earth’s solid inner core is uncertain. However, evidence from the presence of Si in iron meteorites and its depletion in the Earth’s mantle suggest that Si could be the most abundant light element in the Earth’s core, with concentrations estimated up to 16 atomic percent (at%), equivalent to 8 weight percent (wt%)9,12,13,14. Therefore, crucial insights into the present state and thermodynamic evolution of the core can be gained by constraining the phase diagram and elastic properties of the Fe-Si alloy at Earth’s core conditions.

Experimental studies on the phase relations for the Fe-Si alloy15,16,17,18,19 remain, with a few exceptions, limited to pressures that are below the range relevant for the Earth’s inner core (330–360 GPa). Above 200 GPa, these experiments indicate that the Fe-Si phase diagram comprises the hexagonal close-packed (hcp), body-centered cubic (bcc), B2 (a cubic phase isostructural to CsCl), and liquid phases. However, the precise location of the phase boundaries at core pressures remains elusive, and as a consequence, attempts to infer the chemical composition and crystal structure of the Earth’s inner core from the phase diagram are fraught with significant ambiguities. A heated debate persists whether it exists as a two-phase mixture (hcp+B2) or it comprises solely the bcc or hcp phase17,18,19. The solubility limit of Si in solid Fe and the size of the miscibility gap between end-members (Fe and FeSi) are also poorly constrained, especially close to Earth’s core temperatures and pressures. At lower pressures (40 GPa), experiments indicate a strong temperature dependence of the phase boundaries and a stabilization of the bcc phase at temperatures close to melting temperatures20. The distinction between the two reported cubic structures (bcc and B2) is also poorly characterized. The B2 crystal symmetry is a sub-group of the bcc symmetry caused by the emergence of a distinction between the two simple-cubic sublattices that compose the bcc structure (Fig. 1). Evidence for a discontinuous transition between two distinct structures18,21 was not confirmed by more recent experiments19,22. Although the B2 and bcc phases are structurally similar, it was recently pointed out that while the sound velocity of the bcc phase is consistent with seismic values23, the B2 phase has significantly higher values that are incompatible with geophysical observations24.

In both cases, the structure consists of two simple cubic lattices. P(Si) is the probability of finding a Si atom on a given lattice site. When Fe and Si are randomly distributed across all cubic sublattice sites with equal probability (P(Si) = 0.5), the crystallographic structure is bcc (a). Conversely, when Si occupies one of the two simple-cubic sublattices and Fe the other, as shown in (c), the crystal is isostructural with the B2 phase. Intermediate configurations with 0 < P(Si) < 1, shown in (b), retain the B2 crystal symmetry and are called B2-like.

Theoretical investigations of the phase diagram of solid Fe–Si alloys using first-principle methods8,25,26,27,28 have yielded conflicting results regarding the crystal structure of the alloy. Earlier work9,10 suggests that the structure of the alloy is the same (hcp) as that of pure Fe. However, in later studies the bcc8,27 and face-centered cubic (fcc) structures26 have been reported to be stabilized by small concentrations of Si over the hcp structure. No theoretical attempt has been made to clarify structural differences and relative stability of the B2 and bcc phases at core conditions.

While first-principle accuracy is required to discriminate between different structures, accurately sampling vibrational and configurational disorder in a solid solution is challenged by the vast number of physical realizations of the system that need to be calculated in order to achieve statistical converged values of free energies. As a result, most previous first-principle studies have implicitly assumed a random distribution of the Fe and Si atoms, primarily based on the observation that Fe and Si possess very similar atomic sizes at high pressure9. However, this idealized assumption has been recently challenged by the direct experimental observations of chemical short-range order (SRO) in high-entropy alloys composed of elements with comparable atomic sizes29,30. The existence of SRO violates the ideal-mixing approximation and can have a significant impact on the thermodynamic properties and phase relations of a solid solution31,32. In the specific case of Fe-Si, Alfe et al.9,10 have included the effects of non-ideal mixing, but only in the limit of small Si concentrations. However, none of the theoretical work reported so far has been able to include the full effects of configurational disorder in the solid solution at arbitrary concentrations, with first-principle accuracy.

We recently developed a deep-learning-based method to accelerate the sampling of both the vibrational and configurational disorder in alloys, while retaining first-principles accuracy in the description of the interatomic potential33. The method combines particle swaps performed with Monte Carlo (MC) moves with deterministic molecular dynamics (MD) simulations to sample the thermal agitation of particles within a given lattice configuration. It enables the determination of Gibbs free energy surfaces of solid solutions with density-functional theory (DFT) accuracy34,35,36.

In this work, we apply this method to construct phase relations in the Fe-Si binary alloy over a large range of concentrations up to 1:1 stoichiometry, at Earth’s core conditions of pressure and temperature. A complex phase diagram emerges at Earth’s core temperatures, where a re-entrance of the body-centered cubic (bcc) phase is observed. The bcc structure is stabilized by a pronounced short-range ordering of the Si atoms. We also show that a bcc Fe-Si solid solution reproduces key geophysical data, such as the low shear sound velocity and the seismic anisotropy of the inner core, more accurately than other competing structures, making it a strong candidate for the structure of the inner core.

Results

Bcc-B2 phase transition

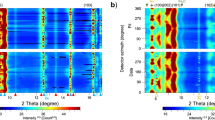

Prompted by previous theoretical studies suggesting that the presence of Si can stabilize the bcc structure over hcp27, we begin our study of the Fe-Si solid solutions by restricting our analysis to cubic lattices, and investigating order-disorder transitions in the bcc and B2 structures. FeSi, as a 1:1 stochiometric compound, crystallizes in the B2 structure at high pressures, in which the two simple-cubic sublattices of the parent bcc structure are fully occupied by Fe and Si atoms, respectively. When the Si concentration is intermediate between the end-members Fe and FeSi, the location of the Si atoms is determined by a balance between the competing effects of entropy, which favors a fully disordered state where the probability of finding a Si atom in the two sublattices is identical, and interatomic energies, which favor an ordered, FeSi-like, state where Si occupies preferentially one of the two sublattices of the bcc structure. The group-subgroup symmetry relation between the bcc and B2 structures gives rise to extra peaks ([100], [210], etc.) in the x-ray diffraction pattern of the B2 phase, with respect to the set of reflections that characterize the bcc structure ([110], [200], [220], etc.)18,22.

We simulate the transition between bcc and B2 in the Fe-Si system using the semi-grand canonical (SGC) ensemble37, where the total number of particles and the difference in chemical potential, denoted as Δμ = μFe − μSi, remain fixed, while the relative concentration of the two species is allowed to fluctuate by swapping the identity of an atom from Fe to Si, or vice versa. The simulations were conducted using a 3456-atom simulation box at temperatures of 4000 K, 5000 K, and 6000 K, respectively, and at a pressure of 330 GPa, with the initial structure being a disordered bcc. By varying the values of Δμ, the equilibrium Si concentration was extracted.

As illustrated in Fig. 2a, we observe a discontinuity in the Si concentration at Δμ = 3843.1 and 3843.4 eV for temperatures of 4000 K and 5000 K, respectively. This indicates the presence of a first-order phase transition from the bcc to the B2 structure. At low concentrations, the probability of Si atoms occupying one of the two simple-cubic sublattices is the same, consistent with a disordered bcc structure. At higher concentrations, Si atoms occupy preferentially one of the sublattices, giving rise to a structure with B2 crystal symmetry and to the appearance of extra peaks in the X-ray diffraction (XRD) spectra. At 6000 K, the change in Si concentration becomes continuous. In the inset of Fig. 2a, we show the XRD intensities of the [100] and [110] peaks across the transition at 6000 K. The [100] peak characteristic of the B2 structure appears at about Δμ ~ 3844 eV, corresponding to a Si concentration of 24 at%. Changes in the long-range ordering of the structure reflect also changes in the short-range atomic structure of the solid solution, as shown in Fig. 2b. The first peak of the Si-Si pair distribution function includes the 1st and 2nd coordination shell of the bcc structure. Its shift to higher distances with increasing Δμ reflects the depletion of the 1st shell arising from the B2-like ordering of the Si sublattice. The relative height of the second and third peaks, located at 3.4 and 4.2 Å, respectively, is also consistent with the bcc-to-B2 transition. Figure 2c shows a sketch of the Fe-Si phase diagram restricted to the bcc-B2 system, based on our simulations. The miscibility gap shrinks with increasing temperature and the observed change in the order of the phase transition from discontinuous to continuous between 5000 K and 6000 K hints at the presence of a tricritical point occurring below 6000 K, above which the transition becomes second order. The phenomena observed in our study align well with previous work on the bcc Fe-Al system using a model Hamiltonian38.

a Calculated Si concentration as a function of Δμ at different temperatures. The inset displays the simulated X-ray diffraction intensity of the (100) and (110) peaks at 6000 K, the (100) peak being a fingerprint of the B2 phase. Convergence on system size was checked by running simulations with 432 and 1024 atoms. We also employed the thermodynamic integration (TDI) method to determine Δμ at fixed cSi, which was found to be consistent with the simulation results obtained in the semi-grand canonical ensemble. b Evolution of the Si–Si pair distribution function (PDF) as function of Δμ. Vertical arrows indicate the three peaks discussed in the text. Peak heights are plotted in arbitrary units (a.u.), normalized to the maximum observed value. c Schematic diagram of the Fe–Si system restricted to the bcc, B2 and liquid phases. The region below the blue dotted lines corresponds to the miscibility gap between bcc and B2. The black dashed line shows the temperature below which we find the bcc structure to be mechanically unstable.

We also found that at high temperatures, the B2-type ordering is present even at concentrations as low as 32 at% Si, which significantly deviates from stoichiometric FeSi. Furthermore, our analysis at 6000 K highlights that although Si atoms in the B2 structure preferentially occupy one of the two cubic sublattices, some degree of disorder due to sublattice chemical interchange persists.

In our recent work on pure Fe (cSi = 0)23 we have shown that range of temperatures where bcc-Fe is mechanically stable is small. Bcc Fe becomes mechanically unstable only a few hundred degreees Kelvin below its melting point, due to the vanishing of the c11 − c12 shear elastic constant. We computed the elastic constants of the Fe–Si solid solution and find that increasing concentrations of Si lead to a dramatic lowering of the temperature at which the bcc structure becomes unstable and therefore to a substantially broadening of the temperature range where the bcc structure is mechanically stable (see Fig. 2c).

Fe-Si phase diagram at 330 GPa

Having clarified the nature of the order-disorder transition in the bcc-B2 system, we are now in a position to extend our study to include all other structures (hcp, fcc, liquid) and determine the full phase diagram of the Fe-Si alloy. To this aim, we employ our recently developed hybrid Monte Carlo (HMC)-based thermodynamic integration (TDI) method to compute the free energies of the hcp, fcc, and liquid phases with first-principle accuracy.

We show the results of the HMC-TDI simulations at 6000 K and 330 GPa in Fig. 3a. These simulations were conducted at several Si concentrations, and a smooth curve was fitted to the resulting Δμ, following the approach proposed in previous studies9,39. As Δμ represents the derivative with respect to cSi of the free energy difference between two phases connected by the transmutation of one Fe atom into a Si atom, its integration over cSi yields the free energy difference between the solutions and the pure phase, which is shown in Fig. 3b. The continuous nature of the bcc-B2 phase transition can also be inferred from the observation that starting from bcc Fe and integrating along Δμ - cSi up to 0.5 results in a free energy that differs from the B2 phase from direct TDI simulations by only 2 meV/atom. Additionally, a characteristic flat region near the minimum in the Gibbs free energy curve is indicative of a continuous phase transition.

Phase boundaries are determined by identifying the common tangent line between two relevant phases. At 6000 K (Fig. 3b), the solid hcp phase remains stable up to 21 at% Si, beyond which a miscibility gap emerges. For Si concentrations exceeding 30 at%, only the B2 phase is stable. As the phase transition boundary between bcc and B2 occurs at approximately 24 at% Si, the bcc phase is not present at this temperature. Moreover, we observe that the fcc phase closely aligns with the free energy of hcp iron at high concentration of Si, but remains less stable than the B2 phases. Additionally, the Gibbs free energy curve of hcp iron closely parallels but remains lower than that of the liquid phase, suggesting the nearly congruent melting of the hcp alloy with a partition coefficient close to 1, in agreement with the results of Alfe et al.9. We applied the same strategy to determine the phase boundary at temperatures of 4000, 5000, 6000, 6200, and 6400 K, respectively.

The full phase diagram is illustrated in Fig. 4. Below 6000 K, a miscibility gap between the hcp and B2 phases is evident, which is consistent with the only available experimental data at this pressure19. As temperature increases, the phase relationships become more complex due to the strong temperature dependence of the phase boundary of the cubic phases and to the appearance of the bcc phase above 6200 K, which pushes the stability region of the hcp phase towards lower cSi and the B2 phase towards higher cSi at high temperatures. The boundaries of the stability range of the bcc structure are subject to a large uncertainty, but clearly show that at Earth’s inner core temperatures the bcc structure is stable in the range 20-25 Si at%, much lower than the concentration required to stabilize the cubic phase at lower temperatures. Our results are consistent with the experimental phase diagram reported at lower pressure (40 GPa) by Edmund et al.20, where a re-entrance of the bcc phase is observed at temperatures close to melting.

The stability field of the hcp phase extends up about ~ 20 at% Si, with a weak temperature dependence. In contrast, the stability field of the B2 phase shows a much stronger temperature dependence. At 4000 K, B2 is stable only within a narrow range of Si concentrations near the FeSi end-member. As temperature increases, the miscibility gap between hcp and B2 phases shrinks and the B2 phase expands its stability field down to 28 at% Si at 6000 K. A stability pocket for the bcc phase emerges in the phase diagram above 6200 K, for Si concentrations ranging from about 20 to ~25 at%. The B2 and bcc phases are separated by a continuous (second-order) transition line. Above 6500 K, only the liquid and B2 phases remain. The eutectic point is located at 6300 ± 150 K and 20 ± 3 at% Si. The experimentally determined solubility limit of Si in hcp at this pressure is also shown19.

The eutectic Si concentration is in the middle of the hcp/bcc miscibility gap, while the eutectic temperature should lie somewhere between 6200 K, where hcp iron alloy remains more stable than the liquid phase (Fig. 3c) and 6450 K, where pure hcp iron melts. The finding that the eutectic temperature of the alloy is close to the melting temperature of pure Fe implies a solid–liquid partition coefficient of Si close to one. Considering that the density difference between solid and liquid at the same Si concentration is independent of the Si concentration (see Fig. S8 in Supplementary Information), we conclude that Si alone cannot explain the observed density jump across the inner-core boundary.

The effects of short-range ordering on phase stability

While the presence of solid solutions with B2 symmetry at cSi ≲ 0.5 and hcp symmetry at cSi ≳ 0 is not surprising in view of the structures of the end-members, the presence in the window around 6200–6500 K and 20–25 at % Si of a stability domain of the bcc structure, that is of a lattice where the location of the Si atoms looses the B2 long-range order, indicates that other, more complex types of ordering of the Si sublattice must come into play in order to explain the reversal of the hcp-bcc relative stability when the Si concentration increases from cSi = 0 to cSi ~ 0.2.

Most previous theoretical works have assumed that the location of the Si atoms in the bcc lattice is purely random. To understand the extent to which the ideal mixing approximation holds, we determined the free energy of solid phases by forcing a random distribution of the Si atoms in the bcc lattice, and calculating free energies using the standard thermodynamic integration method.

The comparison between the ideal-mixing approximation and the fully self-consistent non-ideal calculation is shown in Fig. 5. As expected, the non-ideal solid solutions have a lower free energy compared with the ideal ones, and their difference increases with increasing Si concentration. For Fe-20 at% Si, the free energy difference for hcp Fe–Si can be as large as 19 meV/atom, and it becomes even larger for the bcc phase, reaching about 34 meV/atom. At cSi = 0.2 the effect is large enough to compensate the free-energy difference between hcp and bcc in pure Fe, and for cSi > 0.2 the bcc solid solution becomes more stable than the hcp solid solution. As shown in Fig. 5b, the significant difference between non-ideal and ideal solid solutions results from the presence of SRO in the relative position of the Si atoms, which tends to decrease the probability of its presence in the first coordination shell and increase it in the second one. We found that the effects of SRO are much stronger for the bcc phase than for the hcp and fcc phases, and stabilize the bcc phase at Earth’s inner conditions.

a Gibbs free energies (ΔG) for ideal and non-ideal solid solutions in the bcc, fcc, and hcp structures, with the non-ideal hcp phase as the reference. The free energy of ideal solid solutions was determined using the thermodynamic integration (TDI) method, whereas that of non-ideal solid solutions was obtained via a hybrid Monte Carlo-based TDI method. In the latter case, identity interchange Monte Carlo moves enabled sampling of the full configurational space. Error bars for the ideal solid solutions represent the standard deviation of free energy values computed from five different configurations, each generated by randomly assigning Si atoms within the simulation box. b Normalized coordination number (C.N.) for Si–Si pairs in the first and second coordination shells relative to a fully disordered random alloy.

Discussion

A direct comparison of our results with geophysical observations for the inner core40 is obtained by computing densities and sound velocities of all the solid Fe-Si phases considered in this work, at the pressure and temperature conditions of the inner-core boundary, 330 GPa and 6000 K (Fig. 6). We find that Si has a similar effect on the density of different structures, causing a decrease of ~ 0.05 g/cm3 per 1 at% Si. The Si concentration required to match the density of the Earth’s inner core at 330 GPa is 10 at%, independent of the crystal structure. For hcp, the result agrees with the findings of Alfe et al.9. This concentration is well within the stability range of the hcp structure (Fig. 4), a result which is in contrast with the mixture of B2 and hcp phases proposed in previous studies for similar Si concentrations but lower pressures41.

The effect of Si on compressional wave velocities is small for all solid phases, with only a slight increase of less than 4% as Si concentration increases from 0 to 20 at%. We conclude that the comparison of density and compressional wave velocities with geophysical data is not sufficient to unequivocally discriminate between different crystal structures for the core-forming alloy. In contrast, we find that different solid structures show greater relative variations in shear wave velocities. The best agreement with the PREM model40 is obtained for the bcc alloy, whereas the shear velocities of the hcp, fcc, and B2 alloys (see Fig. S7 in the Supporting Information) are 25%, 30%, and 40% higher than the seismic observations, respectively.

The effects of elements other than Si on the sound velocities of Fe solid solutions have, so far, been investigated only for the hcp structure. A high concentration of O, C, or H in the interstitial sites of the hcp lattice has been reported to yield shear velocities consistent with PREM42. However, a more recent study by Wu et al.43 suggests that the solubility of interstitial light elements in hcp is too low to cause a significant reduction in shear velocities. Similarly, other light elements occupying substitutional sites in hcp have also been found to be present only in very low concentrations9,44 and thus have only a minor effect on shear velocities45.

The calculated anisotropy of the compressional waves in the hcp solid solution is 6%, a value which is too close to the seismic anisotropy of the inner core46 and which would require an unrealistically high degree of crystal orientation. By contrast, the calculated compressional wave anisotropy of the bcc iron alloy is about 20%, a value which is compatible with seismic observations if the primary mechanisms generating anisotropy are solidification texturing, grain growth, melt inclusions47,48 or thermal convection49 rather than the large-scale flow induced by preferential growth at the inner core equator, which has instead been shown to produce seismic anisotropies well below seismic values in cubic phases47.

Our findings that a bcc iron alloy matches geophysical data for density and seismic velocities better than any other structure suggest that the Earth’s inner core might adopt a bcc structure. Although the bcc phase has a higher free energy than the hcp phase at geophysically relevant Si concentrations (about 10 at%), the free energy difference between these two structures is only 23 meV/atom at 6000 K (see Fig. 5a). Such a small difference could be easily overturned by the addition of minor amounts of other elements in the solid solutions.

Indeed, clear evidence suggests that Ni and other light elements such as O which were not included in this study, could further stabilize the cubic phase. For example, recent experiments by Ikuta et al.41 on an Fe-Ni-Si alloy containing about 7 at% Ni and 10 at% Si report a cubic B2 structure at approximately 160 GPa and 2500 K. This stabilization likely originates from short-range ordering driven by differences in atomic sizes between solvents and solutes, as observed in our study. In this context, oxygen may exert an even stronger stabilizing effect on the bcc structure than Ni and Si if it occupies substitutional sites.

The stabilization effects of Ni and O are further supported by studies on the Fe-Ni and Fe-O binary phase diagrams. Ab-initio simulations by Sun et al.50 demonstrate that Ni stabilizes the bcc structure over hcp in the Fe-Ni system. Meanwhile, experimental studies indicate that FeO adopts a B2 structure under core conditions51. Given the close structural relationship between the B2 and bcc phases, these findings reinforce the notion that O could similarly enhance the stability of the cubic structure, as Si does. Even if oxygen remains in interstitial sites, Wu et al.43 have shown that it stabilizes the cubic structure. Consequently, it is plausible that a combination of Ni, Si and O, elements likely present in the Earth’s core, could stabilize the bcc phases at Si concentrations that are compatible with the density constraints. The presence of other light elements may also affect the Si partition coefficient and help reconcile the discrepancy between the calculated density jump for Fe-Si and geophysical data52,53. Future studies should extend our deep-learning model to more realistic geophysical scenarios, including ternary systems and beyond. Despite the computational challenges, our approach remains feasible for determining the phase diagrams of multi-component systems and could offer valuable insights into the composition and structure of the Earth’s inner core.

Methods

The Construction and validation of the deep-learning interatomic potentials

We employed an active-learning method similar to our previous work54 to construct deep-learning interatomic potentials (DLP) for the B2, bcc, fcc, hcp, and liquid Fe–Si alloys using the DeePMD package55, with the training dataset built iteratively. Energies, forces, and virial stress tensors for these structures were computed using Quantum ESPRESSO56,57. The atom identity swap Monte-Carlo move was also employed to expedite the sampling of the configurational space. As shown in Li and Scandolo54, temperature-dependent thermal electron excitations significantly affect the stability of solid phases. To accurately replicate the DFT potential energy surface, we constructed a total of five DLP models at temperatures of 4000, 5000, 6000, 6200, and 6400 K. To reduce computational workload, we initially constructed the DP model from scratch at 6000 K and then refined the model for the other temperatures. Across all conditions, the root-mean-squared errors of energy, pressure, and force were below 8.5 meV/atom, 0.7 GPa, and 0.38 eV/Å, respectively. Detailed information on the active-learning process, the number of structures in the training dataset, neural network architecture, and DFT simulation parameters can be found in Text S1 and S2 of the Supporting Information (SI).

We used an independent testing dataset to validate the developed DLP models and found that their performance remains consistent across all Si concentrations and phases, and comparable to that on the training dataset (See Table S1 in SI). Additionally, we conducted validation checks with up to 500 atoms for the fcc, hcp, and liquid phases, and up to 1024 atoms for the bcc phase, confirming that the tail of the interatomic potential was accurately captured, suggesting that our DLP model can be applied to large-scale simulations (See Text S3 in SI). Furthermore, we performed accuracy checks using free energy perturbation theory and found that the discrepancy between the DLP model and DFT potentials was less than 13 meV/atom (See Fig. S3 in SI). We also verified the performance of the DLP models on elastic properties, which showed good agreement with DFT data (See Text S4 in SI). Therefore, the trained DLP models are accurate proxies for the DFT potentials.

Hybrid Monte Carlo method

We employ the hybrid Monte Carlo method58,59 coupled with deep-learning interatomic potentials to sample the phase space, allowing to treat positional and configurational disorders on an equal footing. The simulations were performed with LAMMPS60. Depending on the targeted statistical ensemble, we use various Monte Carlo moves. For the canonical ensemble, we apply atom displacement MC moves and identity interchange MC sweeps. In the atom displacement MC move, a short molecular dynamics (MD) simulation of Nmd = 5 steps in the microcanonical ensemble is used to generate the trial configuration. In the identity interchange MC sweep, up to 5% of the atoms undergo identity interchange moves, where each move involves randomly selecting one Fe atom and one Si atom and swapping their positions. Note that in an identity interchange MC sweep, only the final configurations contribute to the ensemble average. For the isobaric-isothermal ensemble, we use a composite MC displacement move that combines atom displacement and volume fluctuation, in addition to the identity interchange MC sweeps. The trial configuration in the composite displacement move is generated by running an MD simulation in the isoenthalpic-isobaric ensemble61 for Nmd = 5 steps. All Monte Carlo moves are accepted or rejected based on the Metropolis criterion62. Detailed technical aspects can be found in our recent work33. In practice, we define two probabilities, ηdisp = 0.75 and ηidentity = 0.25, to determine the choice among the different moves. To quantify the uncertainty in the reported values, we employ the block averaging method63 and use the Monte Carlo method for error propagation64.

Semi-grand isobaric and isothermal ensemble

To understand the order-disorder phenomenon in the bcc-FeSi system, we simulate the solid solutions using the semi-grand isobaric and isothermal ensemble (ΔμPT) as developed by37, where P and T represent pressure and temperature, respectively. In this approach, the total number of particles and the chemical potential difference Δμ = μFe − μSi are kept fixed while allowing the compositions to fluctuate. This method is advantageous compared to the conventional canonical and isobaric-isothermal ensembles, where two phases can coexist over a wide range of compositions. In contrast, at a fixed Δμ, only one phase remains stable (bcc vs. B2) in the ΔμPT ensemble. The simulation procedure is similar to the hybrid Monte Carlo algorithm in the NPT ensemble. Instead of the atom identity MC sweep in the semi-grand ensemble, the atom transmutation MC sweep is applied, which consists many atom transmutation MC moves up to 5% of the total number of atoms. We define two probabilities, ηdisp = 0.75 and ηtransmutation = 0.25, for the choice among the different moves. The MC transmutation of atomic species is accepted by the Metropolis criterion62,

where ΔNSi = 1 if a Fe atom is transmuted into Si, while ΔNSi = − 1 if a Si atom is transmuted into Fe, \(\beta={({k}_{B}T)}^{-1}\) where kB is the Boltzmann constant, and ΔU is the change in potential energy evaluated using the deep-learning interatomic potential. It should be noted that in hybrid Monte Carlo simulations in the semi-grand or isobaric-isothermal ensembles, the choice of simulation parameters such as Nmd, ηdisp or ηtransmutation affects only the sampling efficiency and does not influence the ensemble averages.

Thermodynamic integration for solutions

To determine the phase diagram for the Fe-Si system, we employ a four-step procedure to compute the free energies of the bcc, B2, fcc, hcp, and liquid phases by transforming a system with an analytic free energy to the one described by a DFT potential. The phase space is sampled using the hybrid Monte Carlo method, ensuring no approximation is made on the configurational entropy of the solid phases33. Except for the bcc or B2 phases, in the first step, we construct a reversible thermodynamic path connecting the solutions to their pure phase counterparts and compute their free energy difference (\(\Delta {G}_{1}={G}_{{{{{\rm{solution}}}}}}^{{{{{\rm{DLP}}}}}}-{G}_{{{{{\rm{pure}}}}}}^{{{{{\rm{DLP}}}}}}\)) by using the DLP models. For the bcc or B2 phase, the relationship between Δμ and Si concentration (cSi) can be obtained from simulations in the semi-grand canonical ensemble. Since Δμ represents the free energy gradient, ΔG1 can be extracted by integrating the obtained Δμ as a function of cSi. We have also verified the consistency between the thermodynamic integration and the semi-grand canonical ensemble methods, and found excellent agreement as expected (Fig. 2).

In the second step, we apply the thermodynamic integration method to determine the Gibbs free energy difference between the DLP model and a modified version of the Lennard-Jones (LJ) potential that has a soft repulsive core65 (\(\Delta {G}_{2}={G}_{{{{{\rm{pure}}}}}}^{{{{{\rm{DLP}}}}}}-{G}_{{{{{\rm{pure}}}}}}^{{{{{\rm{LJ}}}}}}\)). In the third step, we use the Frenkel-Ladd method66 to compute the free energy difference between the solid or liquid pure phase and a reference system (\(\Delta {G}_{3}={G}_{{{{{\rm{pure}}}}}}^{{{{{\rm{LJ}}}}}}-{G}_{{{{{\rm{pure}}}}}}^{{{{{\rm{ref}}}}}}\)). For solid and liquid iron, the reference systems are chosen as the Einstein crystal and the ideal gas, respectively. In the final step, we calculate the free energy difference described by a DLP model compared to DFT based on free energy perturbation theory (\(\Delta {G}_{4}={G}_{{{{{\rm{solution}}}}}}^{{{{{\rm{DFT}}}}}}-{G}_{{{{{\rm{solution}}}}}}^{{{{{\rm{DLP}}}}}}\)), ensuring that the obtained free energy fully reaches ab initio accuracy (see Text S3 in SI). Consequently, the free energy of a solution is the sum of all the free energy differences calculated in these four steps. We have previously benchmarked this method for the MgO-CaO system under ambient pressure conditions, and it agrees very well with available experimental results33.

In our previous study23, we conducted systematic convergence tests on system size to determine the free energy difference (ΔG2) between the LJ and DLP models for pure phases in the second step. We found that simulation cells containing 3456 atoms for bcc/B2, 3072 atoms for hcp, 4000 atoms for fcc, and 3456 atoms for liquid iron alloys yielded fully converged results, with further increases in system size leading to differences in ΔG2 that remained within the error bars. We then applied these system sizes to calculate the free energy difference (ΔG1) between the solid solutions and the pure systems described by the DLP models in the first step. As shown in Fig. 2, for the cubic structure, even a system size of 432 atoms is sufficient to achieve convergence in ΔG1. In the third step, systematic finite-size scaling is performed to obtain the free energy values for the LJ potential in the thermodynamic limit (see, e.g. Figure 2 in Li and Scandolo (2024)33). In the final step, we used simulation cells with 432, 500, 448, and 432 atoms for the bcc/B2, fcc, hcp, and liquid Fe1−xSix phases, respectively. Simulations were performed for an interval of x = 0.0625, and data were interpolated using a piecewise cubic polynomial to obtain ΔG4 at other x values. Additional tests with a 1024-atom cell for bcc iron yielded results consistent with those obtained from the 432-atom simulation cell.

Elastic properties

The elastic constants of hcp, fcc, and bcc iron alloys at 6000 K and 330 GPa were calculated using the stress-strain method23. In this method, a small strain is applied to a well-equilibrated simulation cell, and the resulting deviatoric stress is determined by performing hybrid Monte Carlo simulations in the canonical ensemble. As demonstrated in our previous study23, simulation cells with 3456, 4000, and 3072 atoms for bcc, fcc, and hcp, respectively, yield converged values for the elastic constants. Here we further examine the convergence of the elastic constants of bcc-Fe0.875Si0.125 as a function of system size, up to 16,000 atoms. We found that a 3456-atom cell is sufficient to reach full convergence, as the differences in elastic constants between the 3456- and 16,000-atom cells fall within the error bars and are not statistically significant (see Fig. S9 in Supporting Information).

Data availability

All relevant data supporting the key findings of this study are available within the article and its Supplementary Information files. Additionally, source data for the figures are provided with this paper.

Code availability

The molecular dynamics simulations in this study were conducted using LAMMPS (Large-scale Atomic/Molecular Massively Parallel Simulator) and the DeepMD-kit for deep-learning interatomic potentials. LAMMPS is an open-source software package available at https://www.lammps.org/, and DeepMD-kit can be accessed at https://github.com/deepmodeling/deepmd-kit. The hybrid Monte Carlo (HMC) LAMMPS plugin, used in this study, is available at https://github.com/ZhiLi00001/hmc and described in Li and Scandolo33. The deep-learning interatomic potential model used in this study is provided with this paper.

References

Hirose, K., Wood, B. & Vočadlo, L. Light elements in the Earth’s core. Nat. Rev. Earth Environ. 2, 645–658 (2021).

Hirose, K., Labrosse, S. & Hernlund, J. Composition and state of the core. Annu. Rev. Earth Planet. Sci. 41, 657–691 (2013).

Kraus, R. G. et al. Measuring the melting curve of iron at super-Earth core conditions. Science 375, 202–205 (2022).

Tateno, S., Hirose, K., Ohishi, Y. & Tatsumi, Y. The structure of iron in Earth’s inner core. Science 330, 359–361 (2010).

Anzellini, S., Dewaele, A., Mezouar, M., Loubeyre, P. & Morard, G. Melting of iron at Earth’s inner core boundary based on fast x-ray diffraction. Science 340, 464–466 (2013).

Alfe, D., Gillan, M. & Price, G. The melting curve of iron at the pressures of the Earth’s core from ab initio calculations. Nature 401, 462–464 (1999).

Laio, A., Bernard, S., Chiarotti, G., Scandolo, S. & Tosatti, E. Physics of iron at Earth’s core conditions. Science 287, 1027–1030 (2000).

Vočadlo, L. et al. Possible thermal and chemical stabilization of body-centred-cubic iron in the Earth’s core. Nature 424, 536–539 (2003).

Alfè, D., Gillan, M. & Price, G. D. Composition and temperature of the Earth’s core constrained by combining ab initio calculations and seismic data. Earth Planet. Sci. Lett. 195, 91–98 (2002).

Alfe, D., Gillan, M. & Price, G. Constraints on the composition of the Earth’s core from ab initio calculations. Nature 405, 172–175 (2000).

Sheriff, K., Cao, Y., Smidt, T. & Freitas, R. Quantifying chemical short-range order in metallic alloys. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. 121, e2322962121 (2024).

Rubie, D. C. et al. Heterogeneous accretion, composition and core-mantle differentiation of the Earth. Earth Planet. Sci. Lett. 301, 31–42 (2011).

Georg, R. B., Halliday, A. N., Schauble, E. A. & Reynolds, B. C. Silicon in the Earth’s core. Nature 447, 1102–1106 (2007).

Allegre, C. J., Poirier, J.-P., Humler, E. & Hofmann, A. W. The chemical composition of the Earth. Earth Planet. Sci. Lett. 134, 515–526 (1995).

Huang, H. et al. Equation of state for shocked Fe-8.6 wt% Si up to 240 GPa and 4670 K. J. Geophys. Res.: Solid Earth 124, 8300–8312 (2019).

Wicks, J. K. et al. Crystal structure and equation of state of Fe-Si alloys at super-Earth core conditions. Sci. Adv. 4, eaao5864 (2018).

Ozawa, H., Hirose, K., Yonemitsu, K. & Ohishi, Y. High-pressure melting experiments on Fe-Si alloys and implications for silicon as a light element in the core. Earth Planet. Sci. Lett. 456, 47–54 (2016).

Fischer, R. A. et al. Phase relations in the Fe-FeSi system at high pressures and temperatures. Earth Planet. Sci. Lett. 373, 54–64 (2013).

Tateno, S., Kuwayama, Y., Hirose, K. & Ohishi, Y. The structure of Fe-Si alloy in Earth’s inner core. Earth Planet. Sci. Lett. 418, 11–19 (2015).

Edmund, E. et al. The Fe-FeSi phase diagram at Mercury’s core conditions. Nat. Commun. 13, 387 (2022).

Dubrovinsky, L. et al. Iron-silica interaction at extreme conditions and the electrically conducting layer at the base of Earth’s mantle. Nature 422, 58–61 (2003).

Lin, J.-F. et al. Phase relations of Fe-Si alloy in Earth’s core. Geophys. Res. Lett. 36 (2009).

Li, Z. & Scandolo, S. Competing phases of iron at Earth’s core conditions from deep-learning-aided ab-initio simulations. Geophys. Res. Lett. 51, e2024GL110357 (2024).

Nagaya, Y., Gomi, H., Ohta, K. & Hirose, K. Equations of state for B2 and bcc Fe1−xSix. Phys. Earth Planet. Inter. 341, 107046 (2023).

Côté, A. S., Vočadlo, L. & Brodholt, J. P. Light elements in the core: effects of impurities on the phase diagram of iron. Geophys. Res. Lett. 35 (2008).

Côté, A. S., Vočadlo, L., Dobson, D. P., Alfè, D. & Brodholt, J. P. Ab initio lattice dynamics calculations on the combined effect of temperature and silicon on the stability of different iron phases in the Earth’s inner core. Phys. Earth Planet. Inter. 178, 2–7 (2010).

Belonoshko, A. B., Rosengren, A., Burakovsky, L., Preston, D. L. & Johansson, B. Melting of Fe and Fe0.9375Si0.0625 at Earth’s core pressures studied using ab initio molecular dynamics. Phys. Rev. B 79, 220102 (2009).

Cui, H., Zhang, Z. & Zhang, Y. The effect of Si and S on the stability of bcc iron with respect to tetragonal strain at the Earth’s inner core conditions. Geophys. Res. Lett. 40, 2958–2962 (2013).

Chen, X. et al. Direct observation of chemical short-range order in a medium-entropy alloy. Nature 592, 712–716 (2021).

Zhang, R. et al. Short-range order and its impact on the CrCoNi medium-entropy alloy. Nature 581, 283–287 (2020).

Alam, A., Chouhan, R. K. & Mookerjee, A. Phonon modes and vibrational entropy of disordered alloys with short-range order: A first-principles calculation. Phys. Rev. B 83, 054201 (2011).

Gao, M. C. et al. Thermodynamics of concentrated solid solution alloys. Curr. Opin. Solid State Mater. Sci. 21, 238–251 (2017).

Li, Z. & Scandolo, S. Efficient determination of free energies of non-ideal solid solutions via hybrid Monte Carlo simulations. Computer Phys. Commun. 304, 109307 (2024).

Kohn, W. & Sham, L. J. Self-consistent equations including exchange and correlation effects. Phys. Rev. 140, A1133 (1965).

Hohenberg, P. & Kohn, W. Inhomogeneous electron gas. Phys. Rev. 136, B864 (1964).

Mermin, N. D. Thermal properties of the inhomogeneous electron gas. Phys. Rev. 137, A1441 (1965).

Kofke, D. A. & Glandt, E. D. Monte Carlo simulation of multicomponent equilibria in a semigrand canonical ensemble. Mol. Phys. 64, 1105–1131 (1988).

Dünweg, B. & Binder, K. Model calculations of phase diagrams of magnetic alloys on the body-centered-cubic lattice. Phys. Rev. B 36, 6935–6952 (1987).

Kranendonk, W. & Frenkel, D. Free energy calculations for solid solutions by computer simulations. Mol. Phys. 72, 699–713 (1991).

Dziewonski, A. M. & Anderson, D. L. Preliminary reference Earth model. Phys. Earth Planet. Inter. 25, 297–356 (1981).

Ikuta, D., Ohtani, E. & Hirao, N. Two-phase mixture of iron-nickel-silicon alloys in the Earth’s inner core. Commun. Earth Environ. 2, 225 (2021).

He, Y. et al. Superionic iron alloys and their seismic velocities in Earth’s inner core. Nature 602, 258–262 (2022).

Wu, Z. et al. Ab initio superionic-liquid phase diagram of Fe1−xOx under Earth’s inner core conditions. Preprint at https://arxiv.org/abs/2410.23557 (2024).

Li, Y., Vočadlo, L., Alfè, D. & Brodholt, J. Carbon partitioning between the Earth’s inner and outer core. J. Geophys. Res.: Solid Earth 124, 12812–12824 (2019).

Vočadlo, L. Ab initio calculations of the elasticity of iron and iron alloys at inner core conditions: evidence for a partially molten inner core? Earth Planet. Sci. Lett. 254, 227–232 (2007).

Mattesini, M. et al. Hemispherical anisotropic patterns of the Earth’s inner core. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. 107, 9507–9512 (2010).

Lincot, A., Merkel, S. & Cardin, P. Is inner core seismic anisotropy a marker for plastic flow of cubic iron? Geophys. Res. Lett. 42, 1326–1333 (2015).

Deguen, R. Structure and dynamics of Earth’s inner core. Earth Planet. Sci. Lett. 333, 211–225 (2012).

Tkalčić, H. et al. Imaging the top of the Earth’s inner core: a present-day flow model. Sci. Rep. 14, 8999 (2024).

Sun, Y. et al. Unveiling the effect of Ni on the formation and structure of Earth’s inner core. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. 121, e2316477121 (2024).

Ozawa, H., Takahashi, F., Hirose, K., Ohishi, Y. & Hirao, N. Phase transition of FeO and stratification in Earth’s outer core. Science 334, 792–794 (2011).

Fu, S., Chariton, S., Prakapenka, V. B. & Shim, S.-H. Core origin of seismic velocity anomalies at Earth’s core-mantle boundary. Nature 615, 646–651 (2023).

Pozzo, M., Davies, C., Gubbins, D. & Alfe, D. Transport properties for liquid silicon-oxygen-iron mixtures at Earth’s core conditions. Phys. Rev. B 87, 014110 (2013).

Li, Z. & Scandolo, S. Deep-learning interatomic potential for iron at extreme conditions. Phys. Rev. B 109, 184108 (2024).

Wang, H., Zhang, L., Han, J. & Weinan, E. DeePMD-kit: A deep learning package for many-body potential energy representation and molecular dynamics. Comput. Phys. Commun. 228, 178–184 (2018).

Giannozzi, P. et al. QUANTUM ESPRESSO: a modular and open-source software project for quantum simulations of materials. J. Phys.: Condens. Matter 21, 395502 (2009).

Giannozzi, P. et al. Advanced capabilities for materials modelling with Quantum ESPRESSO. J. Phys. Condens. Matter 29, 465901 (2017).

Duane, S., Kennedy, A. D., Pendleton, B. J. & Roweth, D. Hybrid Monte Carlo. Phys. Lett. B 195, 216–222 (1987).

Mehlig, B., Heermann, D. & Forrest, B. Hybrid monte carlo method for condensed-matter systems. Phys. Rev. B 45, 679 (1992).

Plimpton, S. Fast parallel algorithms for short-range molecular dynamics. J. Comput. Phys. 117, 1–19 (1995).

Martyna, G. J., Tobias, D. J. & Klein, M. L. Constant pressure molecular dynamics algorithms. J. Chem. Phys. 101, 4177–4189 (1994).

Metropolis, N., Rosenbluth, A. W., Rosenbluth, M. N., Teller, A. H. & Teller, E. Equation of state calculations by fast computing machines. J. Chem. Phys. 21, 1087–1092 (1953).

Flyvbjerg, H. & Petersen, H. G. Error estimates on averages of correlated data. J. Chem. Phys. 91, 461–466 (1989).

Anderson, G. Error propagation by the Monte Carlo method in geochemical calculations. Geochim. Cosmochim. Acta 40, 1533–1538 (1976).

Beutler, T. C., Mark, A. E., van Schaik, R. C., Gerber, P. R. & Van Gunsteren, W. F. Avoiding singularities and numerical instabilities in free energy calculations based on molecular simulations. Chem. Phys. Lett. 222, 529–539 (1994).

Frenkel, D. & Ladd, A. J. New Monte Carlo method to compute the free energy of arbitrary solids. Application to the fcc and hcp phases of hard spheres. J. Chem. Phys. 81, 3188–3193 (1984).

Acknowledgements

We acknowledge CINECA (Consorzio Interuniversitario per il Calcolo Automatico) under the ISCRA initiative and the Leonardo early access program, for the computing resources and support. L.Z. also thanks Chao Li (ICTP) for many useful discussions on statistical sampling with the hybrid Monte Carlo method. The research was supported by MONSTER, awarded to Sandro Scandolo, a project of the Italian National Centre for HPC, Big Data and Quantum computing (ICSC) funded by the European Union - Next Generation EU, through PNNR.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Zhi Li (L.Z.) and Sandro Scandolo (S.S.) designed research; L.Z. performed simulations; L.Z. and S.S. analyzed data; and L.Z. and S.S. wrote the paper.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Peer review

Peer review information

Nature Communications thanks Carlos Pinilla, and the other, anonymous, reviewer(s) for their contribution to the peer review of this work. A peer review file is available.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Source data

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Li, Z., Scandolo, S. Short-range order stabilizes a cubic iron alloy in Earth’s inner core. Nat Commun 16, 7574 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-025-62666-1

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-025-62666-1

This article is cited by

-

Pressure–temperature route from disordered BCC to a 2 × 2 × 2 B2 superstructure

Scientific Reports (2025)