Abstract

Climate change impacts microbial community structure and function, thus altering biogeochemical cycles. Biological nitrogen fixation by diazotrophs is involved in maintaining the balance of the global nitrogen cycle, but the global biogeographic patterns of diazotrophs and their responses to climate change remain unclear. In this study, we use a dataset of 1352 potential diazotrophs by leveraging the co-occurrence of nitrogenase genes (nifHDK) and analyse the global distribution of potential diazotrophs derived from 137,672 samples. Using the random forest model, we construct a global map of diazotroph diversity, revealing spatial variations in diversity across large scales. Feature importance shows that precipitation and temperature may act as drivers of diazotroph diversity, as these factors explain 54.2% of the variation in the global distribution of diazotroph diversity. Using projections of future climate under different shared socioeconomic pathways, we show that overall diazotroph diversity could decline by 1.5%–3.3%, with this decline further exacerbated by development patterns that increase carbon emissions. Our findings highlight the importance of sustainable development in preserving diazotrophs.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Nitrogen is a crucial element required for the synthesis of biomolecules such as nucleic acids and proteins, playing an essential role in survival and continuity of life1. In natural ecosystems, nitrogen primarily exists as inert atmospheric dinitrogen (N2), with limited availability in more reactive forms, such as ammonium and nitrate2. This scarcity of bioavailable nitrogen is a key factor limiting primary productivity in terrestrial and marine ecosystems3,4. Prokaryotes catalysed diverse and complex nitrogen transformation reactions (including nitrogen fixation, ammonia oxidation, nitrification, and denitrification), thereby controlling the nitrogen input, output, and various conversions within the environment5. Among these processes, biological nitrogen fixation (BNF) by diazotrophs represents a major natural pathway for external nitrogen input to ecosystems. It is estimated that BNF contributes approximately 200 Tg N annually to the Earth’s ecosystems, accounting for more than 90% of natural nitrogen fixation and surpassing other non-biological nitrogen-fixing processes (such as lightning)3,6,7,8.

Biological nitrogen fixation via nitrogenases has long played a crucial role in the expanding Earth’s biosphere9. All known biological nitrogen-fixing functions are based on highly conserved nitrogenase genes, which are widely distributed in bacteria and archaea. Recent evidence indicates that a distinct nitrogen-fixing organism (Candidatus Atelocyanobacterium thalassa, or UCYN-A) has been tightly integrated into eukaryotic host (Braarudosphaera bigelowii) cells as endosymbiont-evolved organelles (nitroplasts) to carry out the nitrogen fixation process10,11. The highly diverse phylogenetic and ecological strategies of diazotrophs (including autotrophy, heterotrophy, symbiosis, and free-living lifestyles) contribute to the widespread distribution of nitrogen-fixing capabilities across terrestrial and marine ecosystems12,13. The diversity and composition of diazotrophic communities are critical for determining the rate of biological nitrogen fixation, thereby greatly influencing nitrogen cycling processes on Earth14.

Under prolonged warming conditions, microbial communities are significantly impacted, leading to a continuous decrease in biological diversity15,16. Moreover, specific microbial functional groups within communities exhibit varying responses to climate warming. For example, elevated temperatures strongly change the relative abundance and diversity of potential soil-borne plant pathogens17,18. BNF serves as a primary source of biologically available nitrogen on Earth, and its response to climate change is crucial for long-term soil fertility regulation3. Climate warming has been predicted to increase the nitrogen fixation rate in high-latitude regions but decrease it in low-latitude regions19,20. However, the global biogeographical patterns of diazotrophs and their responses to climate change remain unclear.

Recently, the rapid accumulation of microbiome sequencing data has expanded our understanding of microbial biogeography, providing the possibility to elucidate the distribution of specific functional groups at a global scale18,21,22,23,24,25. In this study, we use the co-occurrence of nitrogenase genes (nifHDK) to identify diazotrophs26 and provide a detailed portrayal of diazotroph diversity over large spatial scales. Using machine learning techniques, we assess the current global relative richness (defined as the diazotroph share in the local community) of diazotrophs, identifying climate variables (mean annual temperature and precipitation) as the key drivers of the global distribution of relative richness. We also project changes in global diversity under various future climate scenarios. Our results suggest that the diazotroph relative richness is closely tied to temperature and precipitation, and that anthropogenic climate change may lead to a marked decline in diazotroph diversity by the end of the century.

Results

Predicting diazotrophs through analysis of co-occurrence nitrogenase genes

We analysed 16,106 representative prokaryotic genomes and identified 10,251 nitrogenase-related genes within 1723 genomes (Supplementary Dataset 1). The genes nifH (vnf/anfH), nifD (vnf/anfD), and nifK (vnf/anfK) are recognized as structural proteins of nitrogenase and are often organized in one or multiple gene clusters5,27. These genomes were classified into various categories based on co-occurrence genes: canonical nitrogen-fixing genomes with molybdenum-iron (MoFe) nitrogenase, alternative nitrogen-fixing genomes with vanadium-iron (VFe) or iron-iron (FeFe) nitrogenase, incomplete nitrogen-fixing genomes with the nifH gene, and other genomes (Fig. 1a and Supplementary Dataset 2). Canonical nitrogen-fixing genomes and alternative nitrogen-fixing genomes are regarded as potential nitrogen fixers. Among the 16,106 genomes, 1352 (comprising 1220 canonical and 132 alternative nitrogen-fixing genomes) harboured the complete nitrogenase gene cluster (nifHDK), accounting for 8.4% of the total. Furthermore, despite having the marker gene nifH, 323 genomes lacked the complete nitrogenase gene cluster, indicating a probable absence of authentic nitrogen fixation capabilities (Fig. 1a).

a UpSet plot illustrating the co-occurrence of nitrogenase-related genes across diverse genomes. The accompanying pie chart depicts the proportional classification of different genome categories. b Phylogenetic tree of representative prokaryotic whole genomes, with branch colours indicating distinct bacterial phyla. The genome classifications are included in the outer rings. c Proportion (%) and number of nitrogen-fixing genomes across different phyla within representative genomes. Source data are provided as a Source Data file.

Among the 1352 potential nitrogen-fixing genomes, 1303 were derived from bacteria and 49 from archaea, representing 8.4% and 9.2% of their respective genomic repertoires, respectively. Our phylogenetic analysis highlights the remarkable taxonomic diversity among these nitrogen-fixing genomes, encompassing 545 genera within 21 phyla (Fig. 1b and Supplementary Dataset 2). The proportion of nitrogen-fixing genomes exhibited considerable variation among phyla; the Chlorobiota presented a 100% frequency of diazotrophs, with all 16 representative strains demonstrating the capability for nitrogen fixation. Comparatively, the proportions of diazotrophs within Pseudomonadota, Bacillota, Thermodesulfobacteriota, and Cyanobacterota were 11.1%, 9.2%, 70.8%, and 46.7%, respectively (Fig. 1c). Among them, the phyla Pseudomonadota, Bacillota, Thermodesulfobacteriota, and Cyanobacterota collectively contained 669, 263, 155, and 84 nitrogen-fixing genomes, respectively, accounting for more than 83.6% of the total, emphasizing their critical contribution to global nitrogen fixation (Fig. 1c).

Compared with the known spectrum of diazotrophs, 779 out of the 1352 potential nitrogen-fixing genomes have experimental validated species within the same genera, whereas 573 predicted nitrogen-fixing genomes belong to 358 previously unrecognized diazotroph genera (Supplementary Dataset 2). We suggest that these 358 genera should receive priority attention from researchers in the future. In particular, more than 70% of the potential diazotrophs of Thermodesulfobacteriata are from the previously unrecognized diazotroph genera (Fig. 1c), making it a promising source for the discovery of potential diazotrophs.

Biogeography of diazotrophic communities

The stringent criterion for identifying diazotrophs requires information of co-occurrence genes, prompting us to map genomes to prokaryotic communities through the 16S rRNA gene to analyse the composition and diversity of diazotrophic communities. This method has been widely used in recent large-scale microbiome research22,28. We collected sequencing data from 137,672 samples across various habitats within the Microbe Atlas Project (MAP) database (Supplementary Fig. 1). These samples span different latitudes (low latitudes [±0°−30°]: 28,416; mid-latitudes [±30°−60°]: 99,528; high latitudes [±60°−90°]: 9728) and extend across seven continents and four oceans, including eighteen principal habitats (Supplementary Dataset 3 and Supplementary Fig. 1). We calculated the absolute number of diazotroph richness for each sample, but considering that the absolute richness increased significantly (two-sided Pearson correlation test, r(137,670) = 0.307, P = 0, t = 119.551, 95% CI = [0.302, 0.311]; Supplementary Fig. 1) as the sequencing depth increased, we used the 16,106 prokaryotic representative genomes to normalize the richness of diazotrophs in the community (defined as the diazotroph share in the local community). In our results, 593 OTUs were identified as diazotrophs (Supplementary Dataset 4). Among these, 57 OTUs were found in all habitats, and 423 OTUs were distributed across more than ten habitats, accounting for 71.3% of all diazotrophic OTUs (Supplementary Fig. 1), indicating the widespread distribution and habitat adaptability of diazotrophs. These diazotrophic OTUs permeated 128,751 samples, accounting for 93.5% of the total dataset, underscoring the widespread propensity for nitrogen fixation within natural microbial communities. Intriguingly, 86.3% of the samples harboured multiple diazotrophic OTUs, indicating a prevalent redundancy of the nitrogen-fixing function within these communities. We found that terrestrial communities harbour a higher proportion of detected diazotrophs (97.1% versus 84.0%) and functional redundancy (93.0% versus 68.2%) compared to marine communities.

We analysed the latitudinal diversity gradient (LDG) patterns of diazotrophic communities in terrestrial and marine samples. The results revealed a significant negative correlation between absolute latitude and relative richness (terrene: two-sided Pearson correlation test, r(96,989) = −0.061, P = 2.73 × 10−80, t = −18.993, 95% CI = [−0.067, −0.055]; marine: two-sided Pearson correlation test, r(27,671) = −0.031, P = 2.85 × 10−7, t = −5.134, 95% CI = [−0.042, −0.019]; Fig. 2a). This observation aligns with findings from studies of diazotrophic communities in forests29. Furthermore, our computation of distance-decay relationships within diazotrophic communities across both terrestrial and marine environments revealed a distance-decay relationship (DDR) pattern (Supplementary Fig. 2), indicating a decrease in-community similarity with escalating geographic separation. The terrestrial gradient (slope = -0.036, two-sided Pearson correlation test, r(487,848) = −0.123, P = 0, t = −86.845, 95% CI = [−0.126, −0.121]) manifested a more precipitous decline than did its marine counterpart (slope = -0.006, two-sided Pearson correlation test, r(101,818) = -0.038, P = 2.644 × 10−33, t = −12.029, 95% CI = [−0.044, −0.032]), suggesting that terrestrial environmental heterogeneity had a more substantial influence on the composition of diazotrophic communities than did marine environmental heterogeneity.

a Latitudinal distribution of diazotroph relative richness in terrestrial and marine ecosystems, with colour variations indicating the mean annual temperature in each sample (terrene: two-sided Pearson correlation test, r(96,989) = −0.061, P = 2.73 × 10−80, t = −18.993, 95% CI = [−0.067, −0.055]; marine: two-sided Pearson correlation test, r(27,671) = −0.031, P = 2.85 × 10−7, t = −5.134, 95% CI = [−0.042, −0.019]). b Relative richness of diazotrophic communities across different habitats. The sample numbers are included in the label. c Principal coordinate analysis of diazotrophic community composition across various habitats, with the distance matrix generated using Bray-Curtis dissimilarity. d Proportions of stochastic processes of diazotrophic communities in different habitats. The box plots display the median (middle line) and the 25th (Q1) and 75th (Q3) percentiles (box boundaries), and the whiskers indicate the Q1 − 1.5 IQR and Q3 + 1.5 IQR of the observations. Each box summarizes statistical distributions derived from randomized subsampling iterations (n = 100) per habitat. Blue represents aquatic environments, and yellow indicates soil environments. Source data are provided as a Source Data file.

Our assessment of the relative richness of diazotrophs across a spectrum of eighteen habitats revealed pronounced disparities in their distributions (Fig. 2b). Paddy fields (median 0.217, interquartile range (IQR) 0.176–0.263) and peatlands (median 0.205, IQR 0.129–0.289) exhibited relative richness far exceeding those of other habitats. Flooded paddy fields provide optimal pH and redox conditions conducive to nitrogen fixation30, whereas peatlands are characterized by persistently low levels of bioavailable nitrogen31, thereby conferring a competitive edge to diazotrophs in these environments. Moreover, grasslands presented high relative richness of diazotrophs, underscoring their substantial contribution to global nitrogen fixation. Conversely, both desert (median 0.044, IQR 0.030–0.068) and shrub (median 0.033, IQR 0.024–0.047) ecosystems exhibited extremely low relative richness of diazotrophs (Fig. 2b). This may be attributed to the moisture scarcity in these arid ecosystems, which potentially restricts the nitrogen-fixing processes of bacteria32.

We analysed the β-diversity of diazotroph composition across different habitats (Fig. 2c), which revealed a pronounced aggregation of soil-derived diazotrophic communities, which contrasts with the composition found in most aquatic habitats (except for waste), indicating marked differences in diazotroph composition between aquatic and soil samples. Despite the differences in diazotroph composition across habitats, the assembly of diazotrophic communities within these habitats appears to be random. Our exploration of the community assembly mechanisms of diazotrophs across these habitats revealed that stochasticity predominates over determinism in shaping these communities. The influence of stochastic processes ranged from 78% ± 3.7% in peatland ecosystems to 96.1% ± 0.5% in polar ice environments (Fig. 2d), thereby emphasizing the critical role of stochasticity in the formation of diazotrophic communities.

Global maps of relative richness in diazotrophic communities

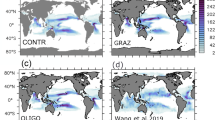

Based on the samples of terrestrial and marine environments in the MAP database, we collected relevant geographic raster data and extracted environmental gridded spatial covariates (e.g., climatic variables, soil-water properties, human activities, etc.) corresponding to latitude and longitude and constructed a regression model between the covariates and the relative richness of diazotrophs using the random forest algorithm. On the basis of cross-validation, we filtered the best subset of variables (63 for terrene and 11 for marine) by feature selection and optimized the model iteratively via a grid search involving hyperparameter tuning (Supplementary Fig. 3). The final model used for prediction performed well (terrene: train dataset, R2 = 0.558, F1,7942 = 10,030, P = 0; marine: train dataset, R2 = 0.324, F1,2981 = 1430, P = 5.597 × 10−256), the mean of ten independent predictions based on the model was used to generate a global map of the relative richness of diazotrophs at a resolution of 0.05° (Fig. 3a and Supplementary Fig. 4), and the coefficients of variation for the ten predictions were used to quantify the estimation uncertainty (Supplementary Fig. 5).

a Relative richness of terrestrial diazotrophs across the world. Sixty-three covariates (resampled resolution of 0.05°) were used in the final random forest model prediction (training dataset with 10-fold cross-validation R2 = 0.558, testing set with R2 = 0.519; Supplementary Fig. 3). Pixels with missing values for covariates are indicated by blanks. b Latitudinal variation in the relative richness of diazotrophs. The y-axis represents relative richness, and the colour represents the density of the pixels with close relative richness. c Relative importance of environmental covariates in the random forest model. The names of the environmental covariates are given in abbreviated form (Supplementary Table 2). d Importance of individual environmental covariates in the random forest model. The top three indices are the mean annual precipitation (bio_12), soil pH (phh2o), and aridity index (ai). IncNodePurity, or increase in node purity, is measured by the sum of squared residuals and represents the effect of each variable on the heterogeneity of observations at each node of the classification tree, thus reflecting the importance of the variables. Source data are provided as a Source Data file.

The prediction map for terrene shows a latitudinal trend in the global relative richness of diazotrophs, with overall low levels of relative richness at mid-latitudes (±25–50°) and higher levels expressed near the equator as well as at high latitudes (above 50°), with the latitudinal median peaking at approximately 70° (Fig. 3b and Supplementary Fig. 6). On an intercontinental scale, the relative richness is highest in North America, Europe, the northern parts of Asia, and Southeast Asia. In contrast, the relative richness levels are lower in Africa and western Asia. Compared with the terrene-based projections, the peaks in the marine map projections are more concentrated in the mid-latitudes (North Pacific, North Atlantic), and the overall latitudinal gradient trend is less pronounced (Supplementary Fig. 4 and Supplementary Fig. 6). Significant correlations were found between the variables selected by the recursive feature elimination method and the predicted values (Spearman correlation, Supplementary Dataset 5), supporting our use of the random forest model to demonstrate the relative importance of different covariates to relative richness (Figs. 3c, 3d and Supplementary Fig. 7). The climate variables (mean annual temperature and precipitation) overwhelmingly ranked high (first: mean annual precipitation-bio12, third: aridity index-ai) and had the highest average importance overall, suggesting that climate is an important predictor of changes in the level of relative richness. Our predictions suggest that climatic variables may be the dominant factor influencing the relative richness of diazotrophic communities at spatial scales.

Projection of diazotrophic community relative richness under future climate scenarios

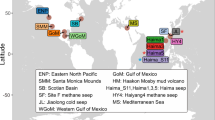

Long-term anthropogenic climate warming has been shown to be an important cause of the reduced richness of soil microorganisms16, and it has been suggested that climate warming has an important effect on nitrogen fixation rates20,33, however, how diazotroph relative richness changes with climate on a global scale remains unknown. Thus, we simulated changes in the relative richness of potential diazotrophs in global communities under four future climate scenarios (shared socioeconomic pathway, SSP126: sustainability; SSP245: middle of the road; SSP370: regional rivalry; SSP585: fossil fuel) for the 2081-2100 timeframe based on the full CMIP6 downscaled global change models (GCMs) provided by WorldClim.

To verify the reliability of the dataset for modelling in predicting climatic variables on a global scale, we removed all pixels with low extrapolation reliability via multivariate environmental similarity surface analysis (MESS) (Supplementary Fig. 8). Our projections indicate that the relative richness of overall diazotrophs will decrease by 1.5%, 2.5%, 2.9%, and 3.3% by the end of the century under the SSP126, SSP245, SSP370, and SSP585 scenarios, respectively (Fig. 4a, b and Supplementary Fig. 9). This suggests that the relative richness of diazotrophs may continue to decrease under future climate scenarios, especially if human activities intensify. Under the full range of climate scenarios, the relative increase in nitrogen-fixing relative richness at mid-latitudes will be accompanied by a continued decrease in relative richness near the equator as well as at high latitudes (Fig. 4a, b). This phenomenon may be associated with the temperature dependence of nitrogenases and differences in the adaptation of nitrogen-fixing organisms to temperature under anomalous climatic conditions5,6. In terms of the relative degree of change and the relative area of different impacts (Fig. 4c, d), the overall global trend is decreasing, with some regional characteristics: Oceania, Antarctica, and Africa show an increasing trend in relative richness, whereas North America, South America, Asia, and Europe show a decreasing trend, and the degree of change increases with climate scenario (increased carbon emissions) changes (except Europe and Antarctica). Such regional differences may suggest potential anthropogenic influences on the relative richness of diazotrophs.

a Trends in the relative richness of diazotrophs under future climate scenarios (2080–2100). The prediction model was based on current bioclimatic variables (resolution of 0.083°) and constructed by the random forest algorithm (Supplementary Fig. 10). The model was used to predict the relative richness of potential future nitrogen-fixing organisms under four climate scenarios for different carbon emission societies (SSP: shared socioeconomic pathway; SSP126: sustainability; SSP245: middle of the road; SSP370: regional rivalry; SSP585: fossil-fuelled development), and we averaged the predictions of downscaled global change models (GCMs; n = 14 for SSP126; n = 12 for SSP245 and SSP585; n = 11 for SSP370) under the same climate scenarios and calculated their changes relative to the current climate (Supplementary Fig. 11). b Overall change in the relative richness of diazotrophs across latitudes under different climate scenarios. We calculated the mean changes in relative richness and showed trends by latitude. c Changes in relative richness across continents under different climate scenarios. We show overall changes in relative richness compared with the current values in all GCMs for each climate scenario based on different intercontinental divisions. For the box plots, the middle line indicates the median, the box represents the 25th (Q1) and 75th (Q3) percentiles (box boundaries), and the whiskers indicate the Q1 − 1.5 IQR and Q3 + 1.5 IQR of the observations. d Proportion of area occupied by each continent whose relative richness changed under different climate scenarios. The bar plot shows the proportions of relative changes in area based on different intercontinental divisions (e.g., the proportions of relative decreases in area are defined as the ratio of the number of pixels in the decreased region to the overall number of pixels). The colour indicates the direction of change for relative richness (increases or decreases). Source data are provided as a Source Data file.

Discussion

The nitrogen-fixing function of prokaryotes arises from their expression of two-component nitrogenases, consisting of the MoFe protein encoded by the nifDK (vnf/anfDGK) gene and the Fe protein encoded by nifH (vnf/anfH)34. nifH has been recognized as a marker gene for the identification of diazotrophs and has been widely used in different environments, which has greatly expanded the diversity of diazotrophs13,35. However, methods for determining relatively accurate nitrogen fixation functions are currently controversial. Approximately 20% of bacterial genomes containing nifH in public databases lack the nifD or nifK gene, and nifH alone may not necessarily be an accurate indicator for the identification of nitrogen-fixing microorganisms36. In the past, the minimal gene set nifHDKENB has been suggested as a standard for prediction37, but it has been noted that nifN or nifE are missing in some diazotrophs (Chloroflexota, Firmicutes, Elusimicrobiota)38,39,40, although they are essential for the assembly and activity of nitrogenases. Here, we identified diazotrophs by co-occurrence nitrogenase genes (nifHDK). We identified diazotrophs in 21 different phylum taxonomic levels, including Pseudomonadota, Bacillota, Thermodesulfobacteriota, and Cyanobacterota, and demonstrated their wide phylogenetic distribution. This is similar to the distribution pattern of diazotrophs (phototrophs versus chemotrophs, aerobes, anaerobes, and facultative anaerobes), as shown in past studies41,42. These observations support the idea that nitrogen-fixing function has been distributed to organisms inhabiting many characteristic ecological niches, reflecting their selective advantage in mitigating fixed nitrogen limitation43. In addition, we compared the predicted classification of diazotrophs at the genus level with past experimental evidence. Experimental evidence for genus-level nitrogen fixation comes from an extensive literature collection42 and the FAPROTAX database44 was constructed on the basis of phenotypic function. Our predictions revealed 573 predicted nitrogen-fixing genomes that lacked experimental evidence in the past, coming from 8 phyla and 358 genera of nitrogen-fixing microorganisms, especially more than 70% of which were Thermodesulfobacteriota. Thermodesulfobacteriota are a group of sulfate-reducing bacteria that thrive in extreme environments. By reducing sulfate to sulfide, they play a vital role in the sulfur cycle45. Our study suggests that Thermodesulfobacteriota may also possess nitrogen-fixing potential. Similar to their function in the sulfur cycle, these extremophiles could contribute to nitrogen cycling within microbial communities, thereby supporting the survival of other microorganisms in extreme ecosystems.

The composition and structure of diazotrophic communities can influence the actual rate of biological nitrogen fixation and are critical to the functioning of soil nutrient cycling14,16. Diazotrophic microorganisms exhibit significant spatial heterogeneity in their distribution across different geographical regions. For instance, Cyanobacteria are the dominant diazotrophic group in the grassland communities of the Tibetan Plateau46, whereas Pseudomonadota is the primary nitrogen-fixing phyla in alpine meadows47. This difference results from their roles in nutrient cycling48. In this study, 57 OTUs were found to be present across all 18 habitats, 44 of which were classified as Pseudomonadota. In contrast to the extremophilic Thermodesulfobacteriota (1 OTU)45 and the aquatic-dominant Cyanobacteriota (3 OTUs)49, Pseudomonadota exhibit notable metabolic diversity and adaptability across a range of environments, enabling them to engage in nitrogen cycling both in soil and aquatic ecosystems. The broad distribution of Pseudomonadota across diverse habitats further emphasizes its ecological significance and potential to sustain nitrogen availability in various environmental contexts. In addition, our results suggest that stochastic processes dominate the species assembly of the diazotrophic community. The composition of functional traits is strongly deterministic, whereas a greater degree of stochasticity is observed for the taxonomic composition of marine N-cycling communities50. This phenomenon originates from widespread functional redundancy among species in microbial communities51. Moreover, our findings suggest that fluidic (aquatic) habitats exhibit a relatively higher proportion of stochastic processes compared to non-fluidic (soil) habitats, a pattern consistent with experimental results and model predictions from previous studies52.

Besides, machine learning was used to predict the relative richness of diazotrophic communities and produce quantitative maps of terrestrial and marine habitat surfaces. Similar to the distribution pattern of bacterial diversity reported in previous global surface soil studies12,53,54, the relative richness of diazotrophic communities exhibited significant latitudinal variation. Unlike the LDG, which decreases from low to high latitudes, we predicted that trends in the relative richness of the terrestrial diazotrophic community tended to favour the mid-latitudes, whereas the opposite was true near the equator and at high latitudes. This regional variation in diazotrophic community relative richness exhibited at absolute latitudes may be due to a combination of environmental factors, such as stronger nitrogen limitation at high latitudes than at mid-latitudes, which may provide a relatively greater survival advantage for nitrogen-fixing organisms at high latitudes55. Compared with those at mid-latitudes, relatively warm climatic conditions near the equator are closer to the optimal temperatures for nitrogen-fixing enzymes, and the increased efficiency of biological nitrogen fixation may help nitrogen-fixing organisms occupy a wider range of ecological niches20.

Furthermore, we analysed the environmental characteristics used for prediction and defined potential drivers related to the relative richness of diazotrophic communities. In the order of importance of random forest features based on node purity, the most important is the average annual precipitation, the second most important is the soil pH, the third most important is the aridity index, and overall, the role of climate is the most dominant, followed by soil properties and human activities. Our results suggest that overall climate primarily influences changes in diazotroph relative richness at broad geographic scales. In past studies, the soil nutrient status has been shown to play an important role in determining the distribution of microorganisms56, and in particular, the content or ratio of carbon, nitrogen, and phosphorus strongly influences the microbial community4. Recently, the distribution of diazotrophic communities has also been shown to be more climate-driven than soil nutrient limitation, including the aridity index57. In addition, precipitation has also been recognized as a key factor that can significantly influence the diversity of soil microbial communities58. Our results support the idea that climate influences mainly the shaping of diazotrophic community relative richness and highlight the importance of soil conditions such as pH.

Since the beginning of the Haber-Bosch process, human activities have more than tripled crop productivity, whereas fertilizers and other anthropogenic nitrogen fixation methods have far outstripped natural contributions. According to estimates of total nitrogen fixation in the 21st century, anthropogenic inputs of nitrogen through fertilizers, fossil fuel combustion, and other forms have reached half of the annual total8. Massive inputs of anthropogenic unnatural nitrogen have had a profound impact on naturally occurring bioavailable nitrogen59, which has also led to unprecedented environmental degradation60. In addition to the impact of anthropogenic nitrogen fixation at specific spatial scales, climate change driven by increased carbon emissions from human activities, including fossil fuel use, may threaten the diversity of diazotrophs at the global level. In fact, the progressive loss of prokaryotic community diversity under conditions of long-term climate warming has been demonstrated16. Our projections based on future climate data under various carbon emission scenarios suggest that the overall relative richness of diazotrophs will decline, with a more pronounced decrease as carbon emissions increase. There were also different trends between continents, which may suggest the potential influence of anthropogenic factors such as population size, level of development, and degree of agriculturalization on the relative richness of diazotrophs. Furthermore, the continued loss of nitrogen-fixing diversity in the future will have a significant impact on the environment, especially those habitats that are highly dependent on N input from diazotrophs (such as peatlands)61. In peatlands, artificial warming is expected to reduce diazotroph diversity and significantly alter community composition, thereby affecting N2 fixation activity within microbiomes62. These changes could ultimately impact host fitness, ecosystem productivity, and carbon storage potential in peatlands, with substantial implications for carbon and nitrogen cycling in boreal ecosystems63. This impact may similarly threaten other natural habitats.

The analyses in this paper are based on predictions of the nitrogen fixation function of prokaryotes. Given the current lack of understanding of nitrogen fixation, our predicted diversity (relative richness) will deviate somewhat from the true value in the environment. However, our results will continue to improve as new microbial taxa continue to be isolated and cultured. Moreover, it should be noted that the above prediction is based only on sequencing data from the current samples, and further experiments are needed to confirm the results, as well as environmental heterogeneity at specific latitudinal and longitudinal points; therefore, predicted maps of the distribution of relative richness for diazotrophic communities may be inaccurate at fine spatial scales but may reveal patterns at larger scales58. Our projections of future diazotroph relative richness depend on the dominance of climate covariates in current projections. If the key influences on diazotroph relative richness change in future scenarios, then our projections will need to be revised accordingly.

In summary, we provide the current global biogeographic distribution of diazotroph relative richness and identify climate as the dominant factor of change. Our work highlights the predictable trend of decreasing diversity of diazotrophic communities predicted to occur in the future with climate warming, with human activities (increased carbon emissions) exacerbating the extent of change. We therefore advocate that potentially decreases in nitrogen-fixing diversity be inhibited by maintaining a climate scenario with low greenhouse gas emissions, thus providing ideas for optimizing sustainable development and valuable references for the future conservation of biodiversity resources, especially the nitrogen-fixing function.

Methods

Identification of potential diazotrophs

The NCBI defines at least one representative genome for each sequenced species. These genomes usually have high sequencing quality. We collected 16,106 representative prokaryotic genomes and corresponding 16S rRNA gene sequences from the NCBI RefSeq database (before November 2022)64. Kofamscan v1.3.065 was used to annotate coding sequences to identify genomes containing nitrogenase-related genes37 (nif/vnfH: K02588, K22899; nif/vnfD: K02586, K22896; nif/vnfK: K02591, K22897; vnf/anfG: K22898, K00531; nif/vnfE: K02587, K22903; nifN: K02592; nifB: K02585). Genomes with genes encoding complete nitrogen-fixing enzymes (nif/vnf/anfHDK) are recognized as potential diazotrophs. Phylogenetic trees of the whole genomes were constructed and annotated by PhyloPhlAn 3.066 and tvBOT 2.667 online.

Mapping MAP operational taxonomic units to prokaryotic genomes

The need for genome information under these stringent criteria compelled us to use a 16S rRNA mapping-based approach to assess the relative richness of diazotrophs in the community. The Microbe Atlas Project (MAP) aims to shed new light on the ecology of global microbes by leveraging large amounts of sequenced microbial communities26. The environmental types (animal, soil, aquatic, and plant; divided by Bray-Curtis community similarity), OTU reads and summary counts of OTUs (with sequence identities ranging from 90% to 99%) for each sample were obtained from the MAP. To analyse diazotrophic communities, we filtered out samples from soil- and aquatic-related environments that contained defined latitudinal and longitudinal information.

The MAP database provides tools for mapping 16S rRNA sequences to OTUs in samples (MAPseq v.2.2.1, MAPref v.3.0), and based on the default parameters, we mapped 16S rRNA sequences from representative prokaryotic genomes to species-level OTUs (97% OTU level)26. With respect to the mapping results, we retained OTUs with confidence (combine_cf) not less than 0.3 and determined the mapping OTUs for the multicopy 16S genome on the basis of the majority (≥50% of copies). In addition, considering the effects of different sampling conditions, we further selected samples containing at least 1000 mapped reads and 10 mapped OTUs and ultimately obtained 137,672 environmental samples for subsequent analysis.

Biogeographical pattern analysis

For the LDG, we considered the process of genome mapping as a random sampling of environmental samples and used the relative richness of diazotrophs (defined as the diazotroph share in the local community, which is the ratio of mapped diazotrophic OTUs to total mapped OTUs, ranging from 0 to 1) as the α-diversity to analyse its relationship with absolute latitude. For the DDR, we constructed 100 subgroups, each comprising 100 random samples. For each subgroup, we calculated the Bray-Curtis similarity between diazotrophic communities and analysed its relationship with log10-transformed geographic distances. The geographic distances between samples were calculated based on Python scripts (Geographiclib package) using the Haversine formula.

Quantification of diazotrophic community assembly processes

Community assembly analysis was performed as described previous study with minor modifications68. Briefly, we constructed subgroups from MAP samples by random sampling, each comprising 100 random samples. For each subgroup, we generated a diazotrophic OTU table and constructed a corresponding phylogenetic tree with MAFFT69 and FastTree70. The β nearest-taxon index (βNTI) was calculated via the vegan package to quantify ecological processes71. The βNTI values were used to estimate the relative contributions of stochastic selection and deterministic selection to community assembly: |βNTI| < 2 indicates stochastic selection, and |βNTI| > 2 indicates deterministic selection. We repeated the above random sampling 100 times for each habitat.

Global maps of diazotroph relative richness

By collecting a wide range of environmental variable rasters from public databases (Supplementary Dataset 6) and based on the ‘randomForest’72 and ‘caret’73 R packages, we constructed machine learning prediction models for the relative richness of diazotrophs in terrestrial and marine environments using the random forest algorithm54,74. The soil variables used for model predictions included climatic conditions, soil properties, physicochemical properties and manmade factors. Climatic conditions were derived from WorldClim (averaged over 1970-2000), and bioclimatic variables were obtained from the CliMond database. The soil property data are mainly from the SoilGrids and EarthData databases. The marine variables collected included water column status, such as temperature, salinity, and dissolved oxygen, and human impacts, including pollution levels and fisheries impacts. To ensure that the covariates were spatially standardized, we resampled all datasets to a resolution of 0.05° by using the nearest neighbour method. To avoid our predictions overstepping their training datasets, the training samples for the ocean and soil models (100,925 samples for soil and 37,440 samples for ocean) were mitigated for potential bias by excluding outliers through the R ‘boxplot.stats’ function. In addition, the sample points with missing covariates were excluded from the random forest model. In addition, through recursive feature elimination, we obtain the best subset of variables for prediction, and the best model for prediction is obtained after hyperparameter tuning by grid search (Supplementary Fig. 3), where R2 and RMSE values are used to identify the best feature variables as well as hyperparameters (mtry, ntree). The above modelling process is based on a 4:1 training set test set division and is executed under 10-fold cross-validation to ensure that the test set is independent of the training set and to minimize the possibility of model overfitting. We use the average of the ten predictions of the final model as the output, and the coefficient of variation is used to quantify the estimation uncertainty (Supplementary Fig. 5). IncNodePurity is used to assess the relative importance of the predictors to the model.

Future relative richness projection

WorldClim provided raster data for 19 bioclimatic variables under the present climate (1970-2000) and different shared socioeconomic pathways (SSPs) in the future Coupled Model Intercomparison Project 6 (CMIP6) downscaled future climate projections (2080–2100, SSP126: sustainability; SSP245: middle of the road; SSP370: regional rivalry; SSP585: fossil-fuelled, Supplementary Table 1). We extracted the current climate data of the samples at a resolution of 0.083° (approximately 10 × 10 km at the equator) and constructed a random forest model of the climate and the relative richness of potential diazotrophs, which used two-thirds of the samples as a training set, and the rest of the built-up data were evaluated via the methods described above. Then, we used multivariate environmental similarity surface analysis (MESS, which is based on the ‘dismo’ R package)75 to remove unreliable prediction ranges. On the basis of 49 CMIP6 downscaled global climate datasets, we predicted the average changes in the relative richness of diazotrophic communities under different future climate scenarios.

Statistical analyses

All data analyses in this article were based on R (version 4.1.2 or 4.3.3) and Python (version 3.9.13). The partial results were visualized by the ‘ggplot2’ package. Raster files were converted and analysed by ‘terra’, ‘raster’ and other R packages.

Reporting summary

Further information on research design is available in the Nature Portfolio Reporting Summary linked to this article.

Data availability

All data generated or analysed during this study have been deposited in the Figshare repository (https://doi.org/10.6084/m9.figshare.26114665). All sequenced genomes and environmental samples are available in the NCBI RefSeq database and MAP database (https://microbeatlas.org). All spatial covariates used for the global maps and original database links are presented in Supplementary Dataset 6. Map outlines derived from Natural Earth public domain datasets (https://www.naturalearthdata.com). The future climate data (CMIP6 GCMs) are available from WorldClim (https://worldclim.org/data/cmip6/cmip6_clim5m.html). Source data are provided with this paper.

Code availability

All scripts and secondary derived data for the analysis process have been deposited in the CodeOcean platform under accession number https://doi.org/10.24433/CO.9682287.v2. https://codeocean.com/capsule/9682287/tree/v2.

References

Canfield, D. E., Glazer, A. N. & Falkowski, P. G. The evolution and future of Earth’s nitrogen cycle. Science 330, 192–196 (2010).

Shamseldin, A. Future outlook of transferring biological nitrogen fixation (BNF) to cereals and challenges to retard achieving this dream. Curr. Microbiol. 79, 171 (2022).

Gruber, N. & Galloway, J. N. An Earth-system perspective of the global nitrogen cycle. Nature 451, 293–296 (2008).

Reed, S. C., Cleveland, C. C. & Townsend, A. R. Functional ecology of free-living nitrogen fixation: a contemporary perspective. Annu Rev. Ecol. Evol. S 42, 489–512 (2011).

Kuypers, M. M. M., Marchant, H. K. & Kartal, B. The microbial nitrogen-cycling network. Nat. Rev. Microbiol 16, 263–276 (2018).

Vitousek, P. M., Menge, D. N., Reed, S. C. & Cleveland, C. C. Biological nitrogen fixation: rates, patterns and ecological controls in terrestrial ecosystems. Philos. Trans. R. Soc. Lond. B Biol. Sci. 368, 20130119 (2013).

Voss, M. et al. The marine nitrogen cycle: recent discoveries, uncertainties and the potential relevance of climate change. Philos. Trans. R. Soc. Lond. B Biol. Sci. 368, 20130121 (2013).

Fowler, D. et al. The global nitrogen cycle in the twenty-first century. Philos. Trans. R. Soc. Lond. B Biol. Sci. 368, 20130164 (2013).

Rucker, H. R. & Kaçar, B. Enigmatic evolution of microbial nitrogen fixation: insights from Earth’s past. Trends Microbiol. 31, 554–564 (2023).

Coale, T. H. et al. Nitrogen-fixing organelle in a marine alga. Science 384, 217–222 (2024).

Raymond, J., Siefert, J. L., Staples, C. R. & Blankenship, R. E. The natural history of nitrogen fixation. Mol. Biol. Evol. 21, 541–554 (2004).

Nelson, M. B., Martiny, A. C. & Martiny, J. B. Global biogeography of microbial nitrogen-cycling traits in soil. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 113, 8033–8040 (2016).

Zehr, J. P. & Capone, D. G. Changing perspectives in marine nitrogen fixation. Science 368, eaay9514 (2020).

Hsu, S. F. & Buckley, D. H. Evidence for the functional significance of diazotroph community structure in soil. ISME J. 3, 124–136 (2009).

Shade, A. et al. Macroecology to unite all life, large and small. Trends Ecol. Evol. 33, 731–744 (2018).

Wu, L. W. et al. Reduction of microbial diversity in grassland soil is driven by long-term climate warming. Nat. Microbiol. 7, 1054–1062 (2022).

Delgado-Baquerizo, M. et al. The proportion of soil-borne pathogens increases with warming at the global scale. Nat. Clim. Change 10, 550–554 (2020).

Li, P. et al. Global diversity and biogeography of potential phytopathogenic fungi in a changing world. Nat. Commun. 14, 6482 (2023).

Wang, Y. P. & Houlton, B. Z. Nitrogen constraints on terrestrial carbon uptake: Implications for the global carbon-climate feedback. Geophys Res Lett. 36, L24403 (2009).

Deutsch, C., Inomura, K., Luo, Y. W. & Wang, Y. P. Projecting global biological N2 fixation under climate warming across land and ocean. Trends Microbiol. 32, 546–553 (2024).

Thompson, L. R. et al. A communal catalogue reveals Earth’s multiscale microbial diversity. Nature 551, 457–463 (2017).

Li, P. et al. Fossil-fuel-dependent scenarios could lead to a significant decline of global plant-beneficial bacteria abundance in soils by 2100. Nat. Food 4, 996–1006 (2023).

Li, D. D. et al. Estimate of the degradation potentials of cellulose, xylan, and chitin across global prokaryotic communities. Environ. Microbiol. 25, 397–409 (2023).

Zhang, Z., Wang, J., Wang, J., Wang, J. & Li, Y. Estimate of the sequenced proportion of the global prokaryotic genome. Microbiome 8, 134 (2020).

Li, D. D. et al. Quantifying functional redundancy in polysaccharide-degrading prokaryotic communities. Microbiome 12, 120 (2024).

Matias Rodrigues, J. F., Schmidt, T. S. B., Tackmann, J. & von Mering, C. MAPseq: highly efficient k-mer search with confidence estimates, for rRNA sequence analysis. Bioinformatics 33, 3808–3810 (2017).

Schmidt, F. V. et al. Structural insights into the iron nitrogenase complex. Nat. Struct. Mol. Biol. 31, 150–158 (2024).

Dmitrijeva, M. et al. A global survey of prokaryotic genomes reveals the eco-evolutionary pressures driving horizontal gene transfer. Nat. Ecol. Evol. 8, 986–998 (2024).

Tu, Q. et al. Biogeographic patterns of soil diazotrophic communities across six forests in North America. Mol. Ecol. 25, 2937–2948 (2016).

Kondo, M. & Yasuda, M. Seasonal changes in N2 fixation activity and N enrichment in paddy soils as affected by soil management in the northern area of Japan. J. Agr. Res. Q. 37, 105–111 (2003).

Wieder, R. K., Vitt, D. H. & Benscoter, B. W. Peatlands and the boreal forest. in Boreal Peatland Ecosystems (eds Wieder R. K., Vitt D. H.) (Springer, 2006).

Tian, J. et al. Soil bacteria with distinct diversity and functions mediates the soil nutrients after introducing leguminous shrub in desert ecosystems. Glob. Ecol. Conserv. 31, e01841 (2021).

Bytnerowicz, T. A., Akana, P. R., Griffin, K. L. & Menge, D. N. L. Temperature sensitivity of woody nitrogen fixation across species and growing temperatures. Nat. Plants 8, 209–216 (2022).

Harwood, C. S. Iron-only and vanadium nitrogenases: fail-safe enzymes or something more?. Annu. Rev. Microbiol. 74, 247–266 (2020).

Zehr, J. P., Jenkins, B. D., Short, S. M. & Steward, G. F. Nitrogenase gene diversity and microbial community structure: a cross-system comparison. Environ. Microbiol. 5, 539–554 (2003).

Mise, K., Masuda, Y., Senoo, K. & Itoh, H. Undervalued pseudo-nifH sequences in public databases distort metagenomic insights into biological nitrogen fixers. mSphere 6, e00785–21 (2021).

Dos Santos, P. C., Fang, Z., Mason, S. W., Setubal, J. C. & Dixon, R. Distribution of nitrogen fixation and nitrogenase-like sequences amongst microbial genomes. BMC Genom. 13, 162 (2012).

Ivanovsky, R. N., Lebedeva, N. V., Keppen, O. I. & Tourova, T. P. Nitrogen metabolism of an anoxygenic filamentous phototrophic bacterium Oscillocholris trichoides strain DG-6. Microbiology 90, 428–434 (2021).

Chen, Y., Nishihara, A. & Haruta, S. Nitrogen-fixing ability and nitrogen fixation-related genes of thermophilic fermentative bacteria in the genus Caldicellulosiruptor. Microbes Environ. 36, ME21018 (2021).

Mendler, K. et al. AnnoTree: visualization and exploration of a functionally annotated microbial tree of life. Nucleic Acids Res. 47, 4442–4448 (2019).

Poudel, S. et al. Origin and evolution of flavin-based electron bifurcating enzymes. Front. Microbiol. 9, 1762 (2018).

Koirala, A. & Brözel, V. S. Phylogeny of nitrogenase structural and assembly components reveals new insights into the origin and distribution of nitrogen fixation across bacteria and archaea. Microorganisms 9, 1662 (2021).

Mus, F., Colman, D. R., Peters, J. W. & Boyd, E. S. Geobiological feedbacks, oxygen, and the evolution of nitrogenase. Free Radic. Biol. Med. 140, 250–259 (2019).

Louca, S., Parfrey, L. W. & Doebeli, M. Decoupling function and taxonomy in the global ocean microbiome. Science 353, 1272–1277 (2016).

Demin, K. A., Prazdnova, E. V., Minkina, T. M. & Gorovtsov, A. V. Sulfate-reducing bacteria unearthed: ecological functions of the diverse prokaryotic group in terrestrial environments. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 90, e01390–23 (2024).

Che, R. et al. Autotrophic and symbiotic diazotrophs dominate nitrogen-fixing communities in Tibetan grassland soils. Sci. Total Environ. 639, 997–1006 (2018).

Wang, J. et al. Contrasting potential impact patterns of unique and shared microbial species on nitrous oxide emissions in grassland soil on the Tibetan Plateau. Appl. Soil Ecol. 195, 105246 (2024).

Guo, L. et al. Fertilization practices affect biological nitrogen fixation by modulating diazotrophic communities in an acidic soil in southern China. Pedosphere 33, 301–311 (2023).

Sanchez-Baracaldo, P., Bianchini, G., Wilson, J. D. & Knoll, A. H. Cyanobacteria and biogeochemical cycles through Earth history. Trends Microbiol. 30, 143–157 (2022).

Song, W. et al. Functional traits resolve mechanisms governing the assembly and distribution of nitrogen-cycling microbial communities in the global ocean. Mbio 13, e03832–21 (2022).

Louca, S. et al. Function and functional redundancy in microbial systems. Nat. Ecol. Evol. 2, 936–943 (2018).

Zhou, J. Z. et al. Stochasticity, succession, and environmental perturbations in a fluidic ecosystem. P Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 111, E836–E845 (2014).

Bahram, M. et al. Structure and function of the global topsoil microbiome. Nature 560, 233–237 (2018).

Zheng, D. et al. Global biogeography and projection of soil antibiotic resistance genes. Sci. Adv. 8, eabq8015 (2022).

Du, E. Z. et al. Global patterns of terrestrial nitrogen and phosphorus limitation. Nat. Geosci. 13, 221–226 (2020).

Leff, J. W. et al. Consistent responses of soil microbial communities to elevated nutrient inputs in grasslands across the globe. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 112, 10967–10972 (2015).

Zhao, W. Q. et al. Broad-scale distribution of diazotrophic communities is driven more by aridity index and temperature than by soil properties across various forests. Glob. Ecol. Biogeogr. 29, 2119–2130 (2020).

Van Den Hoogen, J. et al. Soil nematode abundance and functional group composition at a global scale. Nature 572, 194–198 (2019).

Galloway, J. N. et al. Transformation of the nitrogen cycle: recent trends, questions, and potential solutions. Science 320, 889–892 (2008).

Stein, L. Y. & Klotz, M. G. The nitrogen cycle. Curr. Biol. 26, R94–R98 (2016).

Vile, M. A. et al. N2-fixation by methanotrophs sustains carbon and nitrogen accumulation in pristine peatlands. Biogeochemistry 121, 317–328 (2014).

Carrell, A. A. et al. Experimental warming alters the community composition, diversity, and N2 fixation activity of peat moss (Sphagnum fallax) microbiomes. Glob. Change Biol. 25, 2993–3004 (2019).

Petro, C. et al. Climate drivers alter nitrogen availability in surface peat and decouple N2 fixation from CH4 oxidation in the Sphagnum moss microbiome. Glob. Change Biol. 29, 3159–3176 (2023).

Sayers, E. W. et al. Database resources of the National Center for Biotechnology Information in 2023. Nucleic Acids Res. 51, D29–D38 (2023).

Aramaki, T. et al. KofamKOALA: KEGG Ortholog assignment based on profile HMM and adaptive score threshold. Bioinformatics 36, 2251–2252 (2020).

Asnicar, F. et al. Precise phylogenetic analysis of microbial isolates and genomes from metagenomes using PhyloPhlAn 3.0. Nat. Commun. 11, 2500 (2020).

Xie, J. et al. Tree Visualization By One Table (tvBOT): a web application for visualizing, modifying and annotating phylogenetic trees. Nucleic Acids Res. 51, W587–W592 (2023).

Wang, J., Pan, Z., Yu, J., Zhang, Z. & Li, Y. Z. Global assembly of microbial communities. mSystems 8, e01289–22 (2023).

Katoh, K., Rozewicki, J. & Yamada, K. D. MAFFT online service: multiple sequence alignment, interactive sequence choice and visualization. Brief. Bioinform. 20, 1160–1166 (2019).

Price, M. N., Dehal, P. S. & Arkin, A. P. FastTree 2-approximately maximum-likelihood trees for large alignments. PLoS ONE 5, e9490 (2010).

Stegen, J. C. et al. Quantifying community assembly processes and identifying features that impose them. ISME J. 7, 2069–2079 (2013).

Liaw, A. & Wiener, M. Classification and regression by randomForest. R. N. 2, 18–22 (2002).

Kuhn, M. Building predictive models in R using the caret package. J. Stat. Softw. 28, 1–26 (2008).

Wang, J., Zhu, Y. G., Tiedje, J. M. & Ge, Y. Global biogeography and ecological implications of cobamide-producing prokaryotes. ISME J. 18, wrae009 (2024).

Elith, J., Kearney, M. & Phillips, S. The art of modelling range-shifting species. Methods Ecol. Evol. 1, 330–342 (2010).

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by the Science & Technology Fundamental Resources Investigation Program (2022FY101100), the National Natural Science Foundation of China (32270073) to Z.Z, and the Science Foundation for Youths of Shandong Province (ZR2023QC225) to Z.P.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Z.P., P.L. and Z.Z. conceived and developed the study. Z.P., Z.Z. and P.L. gathered the data, and conducted the analyses. Z.P., P.L. and Z.Z. led the writing of the manuscript. J.S., Y.G. and Y.J. contributed critically to the analyses and the writing. Y.-Z.L. directed the study and critically revised the manuscript for important intellectual content.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Peer review

Peer review information

Nature Communications thanks the anonymous reviewers for their contribution to the peer review of this work. A peer review file is available.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Source data

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Li, P., Pan, Z., Sun, J. et al. Anthropogenic climate change may reduce global diazotroph diversity. Nat Commun 16, 8208 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-025-62843-2

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-025-62843-2