Abstract

The partial oxidation of methane (POM) into value-added C1 chemicals (e.g., CH3OH, HCHO, and CO) offers a promising approach for natural gas utilization under mild conditions. However, existing POM systems often rely on complex catalyst designs and the addition of extra oxidants. Here, we developed a catalyst-free POM system by integrating mechanical stirring with a low-frequency ultrasonic field. A high production rate of C1 chemicals (129.26 µmol h−1) and methane conversion rate (22%) were achieved under ambient conditions (298 K, PCH4 = 0.1 bar, PO2 = 0.1 bar, PN2 = 0.8 bar). Mechanism studies revealed that the introduction of mechanical stirring amplified the ultrasonic cavitation effect, promoting the in-situ release of reactive oxygen species. Reaction pathway investigation confirmed that hydroxyl radicals facilitated the cleavage of methane C-H bonds and that oxygen participated in the generation of POM products. This strategy provides a sustainable avenue for the value-added conversion of methane.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The efficient utilization of natural gas resources has garnered widespread attention, particularly in the conversion of methane (CH4) into value-added chemicals1. The direct selective oxidation of CH4 to form C1 chemicals (e.g., methanol, formaldehyde, and carbon monoxide) has garnered significant interest, as these products serve as important platform molecules or intermediates widely used in fuel and chemical production2,3. Compared to the high-temperature conditions required for industrial CH4 steam reforming, the use of light or electrical energy for the value-added conversion of CH4 under mild reaction conditions is more attractive4,5,6. However, these catalytic pathways often depend on complex catalyst designs and require additional oxidizing agents, while maintaining catalyst cycle stability remains a challenging task. Therefore, designing a catalyst-free partial oxidation of methane (POM) system to achieve the direct selective oxidation of CH4 under ambient conditions holds significant practical application value.

To date, catalyst-free reactions induced by lasers and microdroplets have demonstrated initial success in nitrogen fixation7,8, hydrogen production9,10, and other chemical synthesis processes11. However, there are few reports on the direct conversion of CH4 to C1 chemicals without catalysts. Zare et al. proposed to utilize the unique redox reactivity of water microdroplets to initiate CH4 oxidation, achieving catalyst-free CH4 conversion under mild conditions for the first time12. The lower mass transfer efficiency and reaction selectivity in the reaction process present limitations in the microdroplet mode. Therefore, exploring a catalyst-free POM approach is essential to enhance the production rate and selectivity of C1 chemicals.

In recent years, ultrasonic cavitation technology has been widely applied in environmental protection, energy conversion, and healthcare due to its sonomechanical effects (high temperature, high pressure, micro-jet, and shock wave) and sonochemical effects (generation of active substances such as •OH, •H, and •OOH radicals)13,14. Energy conversion using ultrasound has become a major research focus, primarily because the extreme conditions created by ultrasonic cavitation provide ideal environments for the dissociation and conversion of inert molecules (N₂, CO₂, CH₄, etc.). Previous studies on CH4 ultrasonic decomposition have focused on high-frequency ultrasound and anaerobic conditions. Henglein and Dehane et al. demonstrated that CH4 can produce gaseous products such as H2, CO and C2 hydrocarbons under ultrasonic irradiation, and pointed out that in multi-bubble systems, the irradiation frequency should be optimized according to the parameter of number density15,16. However, the efficiency of ultrasonic CH4 decomposition is limited due to the attenuation and inhomogeneity of sound waves17. Introducing mechanical stirring into a sonochemical reactor can effectively enhance heat and mass transfer in liquid-phase reactions, while also influencing the sonoluminescence (SL) and sonochemiluminescence (SCL)18,19. However, the fluid flow induced by stirring is influenced by various sonochemical factors, such as ultrasonic frequency and power, temperature, and dissolved gases20. Most studies suggest that combining ultrasound with stirring or external airflow significantly improves the generation of free radicals or reaction efficiency17,21,22. Bussemaker et al. systematically explored the effects of overhead stirring and external flow on low and high-frequency ultrasonic fields23,24. The results showed that at low frequency (40 kHz), the introduction of overhead stirring achieves the maximum hydroxyl radical generation, which is contrary to the common belief that high frequencies are more efficient in radical generation. They pointed out that sonochemical activity in a 40 kHz reactor is driven by both traveling and standing waves, whereas the ultrasonic field in high-frequency reactors is dominated by traveling waves. Overhead stirring during low-frequency ultrasound can reduce the standing wave effect and generate more active bubbles, while in high-frequency ultrasound, a slower flow-through method is recommended. This suggests that the impact of mechanical stirring on sonochemical reactions is closely related to ultrasonic frequency, and the optimal combination of stirring speed, ultrasonic frequency, and power is essential for enhancing sonochemical yield. If sonochemical effects are required in the process, then amplification of the stirred reactor should be considered at lower rather than higher frequencies, since the results of Bussemaker et al. have demonstrated that at a low frequency, lower input power results in maximum sonochemical effects, which reduces the additional energy input. Mechanistic studies of the enhancement of the sonochemical effect by the introduction of mechanical agitation in a low-frequency field was carried out by Nie and Zhang et al.25,26. The results showed that in a 40 kHz ultrasonic field, the introduction of mechanical stirring alters the spatial distribution of the ultrasonic field, addressing issues such as uneven acoustic field distribution and acoustic energy attenuation. The increase in acoustic field pressure not only promotes cavitation in the vortex and impeller zones but also lowers the nucleation energy threshold27, resulting in the formation of more cavitation bubbles and providing broader coverage of high-energy cavitation sites. For instance, in an aqueous system with oxygen, the enhanced ultrasonic cavitation effect promotes the in-situ generation of abundant reactive oxygen species (ROS), resulting in the removal rate of 5 μM diethyl phthalate (DEP) reached 95% within 90 min26. In summary, introducing mechanical stirring at the optimal ultrasonic frequency and power can amplify cavitation and enhance free radical generation. Therefore, we expect this strategy to significantly improve the efficiency of the POM process.

In this work, we propose a catalyst-free POM approach. The combination of a vortex flow field and a low-frequency ultrasonic field enables the direct conversion of CH4 to C1 value-added chemicals under ambient conditions. The periodic generation and collapse of ultrasonic cavitation bubbles create a localized, instantaneous high-temperature and high-pressure environment, promoting the fracture of methane C-H bonds and the in-situ generation of ROS. Mechanism studies proved that in the POM reaction pathway, H2O provides •OH radicals for the hydrogen extraction reaction of CH4 and further oxidation reaction, while oxygen is involved in the formation of most intermediates and is the main source of oxygen atom for the final C1 products.

Results and discussion

Performance of catalyst-free partial oxidation of methane

In the catalyst-free POM system, methyl peroxide (CH3OOH), methanol (CH3OH), and formaldehyde (HCHO) were detected as the main liquid products. The gaseous products consisted primarily of hydrogen (H2) and carbon monoxide (CO), with only trace amounts of carbon dioxide (CO2) detected. Different external field conditions significantly influence the CH4 conversion and the production rate of C1 value-added chemicals. As shown in Fig. 1a, under identical partial pressures of CH4 and O2 (0.1 bar), the production rates of POM products increase with stirring speed, peaking at 600 rpm (CH3OOH: 9.83 µmol h−1, CH3OH: 10.82 µmol h−1, HCHO: 13.57 µmol h−1, and CO: 95.04 µmol h−1). When low-frequency ultrasound is used alone, only trace amounts of products are detected. This phenomenon underscores the importance of introducing mechanical stirring in a low-frequency ultrasonic field to improve the POM yield. The regulation of oxygen partial pressure is crucial for the selectivity of POM products. In the absence of oxygen, only trace amounts of CH3OH and HCHO are detected. The introduction of an appropriate oxygen level positively impacts the improvement of POM yield. However, excessive oxygen leads to an increase in the proportion of CO2, a deep oxidation product of CH4, suggesting that there is an optimal oxygen partial pressure in the POM process (Fig. 1b).

a Production rates of POM products and corresponding CH4 conversion rates at various stirring speeds. Reaction conditions: PCH4 = 0.1 bar, PO2 = 0.1 bar, PN2 = 0.8 bar, 298 K, ultrasonic source: frequency = 40 kHz, power density = 3.6 W cm−3. b Production rates of POM products and corresponding CH4 conversion rates under different oxygen pressures. Reaction conditions: Ptotal = 1 bar, 298 K, stirring speed = 600 rpm, ultrasonic source: frequency = 40 kHz, power density = 3.6 W cm−3. c–h The influence of reaction temperature (c), ultrasonic power density (d), ultrasonic frequency (e), solution PH (f), ion concentration (g), and stirring paddle materials (h) on the yield of POM products and CH4 conversion rates. Reaction conditions: PCH4 = 0.1 bar, PO2 = 0.1 bar, PN2 = 0.8 bar, stirring speed = 600 rpm. i Cycle test of POM in a closed system. Test conditions: PCH4 = 0.1 bar, PO2 = 0.1 bar, PN2 = 0.8 bar, 298 K, stirring speed = 600 rpm, ultrasonic source: frequency = 40 kHz, power density = 3.6 W cm−3. The term rpm stands for revolutions per minute. The error bars in (a–i) represent standard deviations (s.d.) obtained from n = 3 independent measurements. Source data are provided as a Source Data file.

Figure 1c demonstrates a “volcano-type” trend in the relationship between reaction temperature and the production rate of POM. Research indicates that temperature primarily affects the vapor pressure of the liquid phase, thereby influencing the cavitation effect in the ultrasonic field. As the temperature increases, the vapor pressure of the liquid phase rises, making it easier for cavitation bubbles to form. In addition, the reduction in surface tension allows the bubbles to grow and collapse more readily, thereby enhancing the cavitation effect28. However, when the temperature exceeds 313 K, the concentration of water vapor increases, causing the cavitation bubbles to be filled more with vapor rather than gas. This leads to a decrease in the intensity of bubble collapse, meaning that the energy released during the collapse is reduced, thereby weakening the ultrasonic cavitation effect29. Generally, the optimal temperature for ultrasonic cavitation is between 298 and 308 K, consistent with the results of this experiment30. Moreover, a decrease in ultrasonic power density and an increase in frequency both result in a reduction in the POM yield (Fig. 1d, e). This phenomenon would be resulted from that the intensity of the ultrasonic cavitation effect is directly proportional to power density, while the size of cavitation bubbles is inversely proportional to ultrasonic frequency31. At higher frequencies, smaller bubbles result in a weaker cavitation effect24. The pH of the reaction solution and ion concentration also influence the selectivity and yield of POM products. Under alkaline conditions, hydroxide ions in the solution are more easily decomposed to generate •OH radicals through ultrasonic cavitation. •OH radicals can promote the oxidation reaction of CH4 and increase the production rate of CH3OH and HCHO (Fig. 1f). In acidic environments, higher concentrations of hydrogen ions may interact with reaction intermediates, driving the reaction toward complete oxidation and ultimately leading to the formation of more CO2. The presence of chloride ions affects the generation of free radicals in the POM, particularly the formation of chlorine (•Cl) radicals. •Cl radicals are highly reactive and can rapidly break C-H bonds in CH432. This reaction not only improves CH4 conversion efficiency but may also accelerate the process. As shown in Fig. 1g, at a sodium chloride concentration of 0.001 M, the yields of CH3OOH, CH3OH, and HCHO increase significantly. However, excessively high ion concentrations hinder the generation of liquid products, as chloride ions excessively consume •OH radicals, leading to the dominance of •Cl radicals. In addition, the increase in NaCl concentration raises the viscosity of the solution, affecting ultrasonic cavitation efficiency33,34. Subsequently, to rule out the impact of the contact-electro-transfer effect between the Teflon stirring paddle and water on the production of POM products, we conducted a control experiment using a stainless-steel stirring paddle of the same size. The results show that the material of the stirring paddle has almost no effect on the efficiency of POM, suggesting that the increase in production is due to the mechanical stirring-enhanced ultrasonic cavitation effect, rather than the direct contact-electro-catalysis of the dielectric material with water (Fig. 1h).

In summary, under the following reaction conditions (PCH4 = 0.1 bar, PO2 = 0.1 bar, PN2 = 0.8 bar, 298 K, and stirring speed = 600 rpm), the total yield of POM liquid-phase products reached 34.22 μmol h−1, surpassing most of the reported POM systems under mild conditions with catalysts, and demonstrating competitiveness even in pressurized systems (Supplementary Fig. 1)6,12,35,36,37,38,39,40,41,42. In the closed system, the production rates of POM products and CH4 conversion rate remain stable over 5 cycles (Fig. 1i), while in the flow system, the yield values of liquid-phase products from POM show a linear upward trend over 8 h of continuous testing (Supplementary Fig. 2). This demonstrates the stability and scalability of this strategy for POM under ambient conditions.

Mechanism investigation of mechanical stirring-enhanced ultrasonic cavitation

To elucidate the mechanism of the enhanced ultrasonic cavitation effect induced by mechanical stirring in a low-frequency ultrasonic field, we simulated the distribution of flow and acoustic fields in the reaction system in the presence or absence of mechanical stirring. As illustrated in Supplementary Figs. 3 and 4, the application of ultrasonic waves alone leads to a sound pressure distribution in the flask resembling a standing wave sound field. The substantial difference in sound pressure amplitude between the wave nodes and crests of the standing wave sound field reduces the uniformity of the sound field, thereby decreasing cavitation efficiency43. When the stirring speed reaches 600 rpm, the liquid in the flask forms a vortex field (Supplementary Fig. 5). In this case, the liquid surface is regarded as a soft acoustic boundary, allowing a certain degree of reflection, while the liquid container wall and stirring paddles act as hard acoustic boundaries, causing strong reflection of sound waves. Specifically, the vortex field alters the propagation path and direction of sound waves. When an acoustic wave enters the vortex field, its direction is deflected due to the rotational and turbulent properties of the vortex, causing the energy of the sound wave to diffuse in various directions. Notably, the impact of the vortex field on acoustic wave intensity is frequency-dependent. Under high-frequency ultrasound, the cavitation effect of bubbles is suppressed due to scattering and absorption of acoustic waves by the vortex. This effect is particularly pronounced for small bubbles, which lose coordination due to the vortex, leading to instability and disorder in the cavitation process33. In contrast, under low-frequency ultrasound, the vortex field tends to enhance the cavitation effect. Low-frequency sound waves provide more time for bubble expansion, allowing them to undergo more violent expansion and contraction cycles. The vortex field increases the aggregation and collision frequency of bubbles by inducing localized turbulence, thereby promoting their merging and enlargement. To analyze the sound field distribution of the liquid in the flask in more depth, we selected three cross sections of the standing wave sound field (at the peak, trough, and node of the standing wave, respectively). Figure 2 shows the sound field distribution of various cross sections of the flask at different stirring speeds. When the stirring speed reaches 600 rpm, the sound field distribution at each cross-section becomes more uniform than that at lower speeds, and the sound pressure amplitude in more areas of the cross-section exceeds the cavitation threshold (Fig. 2c).

a–c A schematic simulation of the sound field distribution at various stirring speeds (a 0 rpm, b 300 rpm, c 600 rpm), located at the peaks, nodes, and troughs of the standing wave. The color bar in the legend indicates the sectional sound pressure range, expressed in pascals (Pa). The blue region represents areas of negative sound pressure, whereas the red region corresponds to areas of positive sound pressure.

The introduction of stirring achieves higher sound pressure amplitude and a more uniform sound pressure distribution. However, an excessively high stirring speed increases the curvature radius of the vortex field surface (Supplementary Fig. 5a–c). This causes the reflected sound pressure to gradually shift toward the center of the flask, preventing multiple reflections on the flask wall and thereby reducing the sound pressure amplitude. In addition, as the stirring speed increases to 900 rpm, the Reynolds (Re) number of the fluid reaches 24,000 (Supplementary Table 1), placing the system in a fully turbulent state. At the same time, phenomena such as liquid splashing and significant surface fluctuations were observed in the experimental setup, indicating highly disordered and unstable flow characteristics (Supplementary Fig. 6). The strong shear force generated by the intense turbulence can cause cavitation bubbles to be destroyed before they reach sufficient expansion. As a result, the cavitation bubble’s lifecycle is shortened, and both the intensity and duration of energy release are reduced, thereby suppressing the ultrasonic cavitation effect18,44. Fluorescence emission spectra of 2-hydroxyterephthalic acid (Supplementary Fig. 7) and electron paramagnetic resonance (EPR) spectra (Fig. 3a, b) indicate that the weakening of the cavitation effect leads to a decrease in ROS production. When the stirring speed reaches 900 rpm, the signal intensities of •OH and •OOH radicals decrease accordingly, which also explains the decrease in yield of POM product at high stirring speed. Therefore, an appropriate stirring speed promotes homogeneous mixing and cavitation bubble formation.

a, b EPR spectra of •OH, •CH3 (a), and •OOH (b) radicals trapped by DMPO as a function of stirring speed. Detection conditions: PCH4 = 0.1 bar, PO2 = 0.1 bar, PN2 = 0.8 bar, 298 K, solutions: H2O (a) and CH3OH (b). c Time-dependent EPR spectrum of •OH and CH3• radicals trapped by DMPO. Detection conditions: PCH4 = 0.1 bar, PN2 = 0.9 bar, 298 K, solution: H2O. d, e GC-MS spectra of the produced CH3OH with isotopically labeled 18O2, H218O (d), and D2O (e). f GC-MS spectra of the generated CO with isotopically labeled 18O2 and H218O. The term m/z stands for mass-to-charge ratio. The units of intensity are arbitrary, abbreviated arb. units. Source data are provided as a Source Data file.

The above mechanism study suggests that introducing mechanical stirring in a low-frequency ultrasonic field reduces the aggregation of cavitation bubbles, leading to a broader and more uniform sound field distribution and a significant increase in sound pressure amplitude. As a result, the ultrasonic cavitation effect is amplified, promoting the generation of more ROS and positively impacting the yield of POM products.

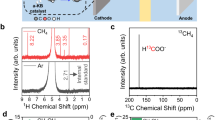

Reaction pathway investigation of the catalyst-free POM

To investigate the POM reaction pathway under low-frequency ultrasound and vortex flow fields, we utilized EPR technology and isotope tracing to identify key intermediates produced during the process, as well as the sources of CH3OH and CO molecules. 5,5-Dimethyl-1-pyrrolidine N-oxide (DMPO) was used as a spin-trapping probe to detect ROS, with different DMPO-OH, DMPO-CH3, and DMPO-OOH signals observed in the presence of both CH4 and O2 (Fig. 3a, b). In the absence of oxygen (PCH4 = 0.1 bar and PN2 = 0.9 bar), the DMPO-CH3 adduct signal is more prominent (Fig. 3c), suggesting that CH4 in the system generates a significant amount of CH3• radicals under ultrasonic irradiation and the influence of •OH radicals. CH3• radicals may react with •OH radicals to directly generate CH3OH. However, this pathway is not the primary route for CH3OH production in the POM process, as the yield of CH3OH is low when only CH4 is present. In contrast, the introduction of O2 significantly enhances the yield of CH3OH, and a substantial amount of CH3OOH is detected in the system. Moreover, when •OH and •OOH radicals in the system were quenched, the POM product yield decreased significantly, highlighting the importance of H2O and O2 in the POM process (Supplementary Fig. 8).

Isotope tracing was conducted using CH4 + 18O2 + H2O and CH4 + O2 + H218O + H2O as reactants to trace the source of oxygen in CH3OH. The results show that the former reactant combination exhibits a strong CH318OH signal, indicating that the oxygen atom in CH3OH primarily originates from O2 rather than H2O (Fig. 3d). By replacing H2O with D2O as a tracer for the source of hydrogen in CH3OH, both CH3OH and CH3OD signals are detected with an intensity ratio of 5:1 (Fig. 3e). This phenomenon indicates that the amounts of CH3OD in the oxidation products is low, and CH3OH still constitutes the majority. Although the reaction rate of deuterated hydrogen (D) is much lower than that of hydrogen (H), the yield of CH3OH in D2O does not decrease compared to that in H2O. This suggests that only a small proportion of D species participate in CH3OH production. Most of the H in the -OH group of CH3OH originates from CH4, with only a small portion derived from H produced by H2O decomposition. The oxygen isotope tracing results for the major gaseous products indicate that most of the oxygen atom in CO originates from oxygen, suggesting that it is likely formed by the further decomposition or oxidation of HCHO (Fig. 3f). In addition, under an N2 atmosphere (PN2 = 1.0 bar), only trace amounts of H2 are produced in the pure water system under the influence of mechanical stirring (600 rpm) and the ultrasonic field (Supplementary Fig. 9). In contrast, under a CH4 atmosphere (PCH4 = 0.1 bar and PN2 = 0.8 bar,), a large amount of H2 is detected (Fig. 1b). This phenomenon suggests that the H2 produced during the POM process primarily results from the recombination of •H radicals generated by CH4 decomposition, rather than from •H produced by H2O ultrasonic decomposition.

The molecular dynamics (MD) simulation results are consistent with the inferred reaction pathway described above. CH4, O2, and H2O molecules are randomly placed into a cubic box with a side length of 2.5 nm. This structure is then used as the initial configuration for the MD simulations using the LAMMPS program package (Fig. 4a). In the simulation, a periodic ultrasonic-like perturbation was introduced by periodically heating the system to 4000 K every 50 ps. This periodic heating protocol was designed to mimic the transient high-temperature and pressure conditions typically associated with ultrasonic treatment (Fig. 4b). During the MD process, as time progresses, free radical signals, such as •OH, •H, CH3•, CH3OO•, and CH3O• radicals emerged (Fig. 4c, d). CH3OOH was unstable under high temperature and pressure during the simulation and rapidly decomposed into products such as CH3O• radicals and HCHO, resulting in no significant signal. However, the results of nuclear magnetic resonance (NMR) (Supplementary Fig. 10) and EPR tests (Fig. 3b) confirm its existence. Figure 4e shows that substantial amounts of H2 and CO generated during the simulation, consistent with the experimental results, indicating that high-value gaseous products can be formed in the gas phase during the POM process.

a Schematic diagram of molecular dynamics simulation, where box side length L = 2.5 nm, and the simulation time is 600 ps. b A periodic heating protocol was designed to mimic the transient high-temperature (4000 K) and pressure (60,000 bar) conditions typically associated with ultrasonic treatment. c–e Number of species (c, d) and molecules (e) as a function of time for main POM products during MD simulation. The units of species number are arbitrary, abbreviated arb.units. f Possible reaction pathway of catalyst-free POM process. Source data are provided as a Source Data file.

Based on the results of the isotope test, EPR test, and MD simulations, we propose the following POM reaction pathways (Fig. 4f). The ultrasonic cavitation effect, enhanced by mechanical stirring, creates a transient high-temperature, high-pressure environment throughout the system. In this environment, the decomposition of H2O generates •OH and •H radicals. The former promotes the dissociation of C-H bonds in CH4, while the latter reacts with oxygen to form •OOH radicals. Under ultrasonic cavitation and reaction of •OH radicals, CH4 decomposes into CH3• and •H radicals. The combination of •H radicals is the primary mechanism for H₂ formation. A small amount of CH3• radicals combine with •OH radicals produced by H2O decomposition to directly generate CH3OH, while most participate in CH3OOH formation. Two possible reaction pathways exist for generating CH3OOH. One pathway involves the reaction of CH3• with O2 to form CH3OO• radicals, which subsequently react with •H radicals to form CH3OOH. Another pathway involves the coupling of CH3• with •OOH radicals to form CH3OOH. The final liquid-phase products (CH3OH and HCHO) of the POM process are primarily further decomposed by CH3OOH, while the main gas-phase product, CO, is formed by the decomposition or oxidation of HCHO.

This study successfully demonstrates a catalyst-free strategy for the POM. Through the synergistic effect of vortex and ultrasonic fields, High production rates of C1 chemicals (CH3OH: 10.82 µmol h−1, HCHO: 13.57 µmol h−1, CO: 95.04 µmol h−1) were achieved, without a trend toward methane over-oxidation. The mechanism study indicates that the introduction of mechanical stirring lowered the cavitation bubble formation threshold, inhibited bubble aggregation, and increased the amplitude of the ultrasonic sound field. The enhanced ultrasonic cavitation effect promoted the cleavage of methane C-H bonds during the POM process and increased oxygen participation in the reaction. This strategy introduces a catalyst-free conversion pathway for methane catalytic oxidation and provides new insights into the effective utilization of natural gas. We anticipate that this catalyst-free strategy based on ultrasonic cavitation will be applicable to additional energy conversion models in the future.

Methods

Partial oxidation of methane reaction system

A 250 mL three-necked flask placed in an ultrasonic cleaner was used as the reaction vessel. Methane (10 % CH4 in N2) and oxygen are mixed in different ratios methane to oxygen by mass flow meters. After continuous aeration into 100 mL of deionized water (DI) for 30 min, the reaction was carried out by switching on sonication (40 kHz, 360 W) and stirring (0, 100, 300, 600, 900 rpm). A circulating chiller kept the system’s temperature at the necessary experimental temperature during the reaction. We kept the position of the three-necked flasks in the ultrasonic cleaner constant for each experiment, and the water level in the ultrasonic cleaner constant to exclude other factors interfering. In a closed system, the gas is introduced for 30 min, after which the system is sealed with a sealing plug. In a flow reactor, the relevant gas is continuously introduced during the reaction (Supplementary Fig. 11).

Product analysis

Liquid-phase oxygenate products were analyzed and quantified by 1H nuclear magnetic resonance (NMR) spectroscopy (Bruker, Advance III 500 MHz) and gas chromatography (GC7900, Timex) (Supplementary Fig. 10). Typically, 0.4 mL post-reaction samples were mixed with 0.1 mL of D2O, and 0.1 mL dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO) in DI (an internal standard, 2 µL 100 mL−1) was added as an internal standard. The concentration of the standard product solution was plotted against the area of the product and DMSO to obtain a calibration curve. The products were quantified by comparing the 1H NMR signal with the calibration curve (Supplementary Fig. 10). Since pure CH3OOH could not be purchased, while both CH3OOH and CH3OH have the methyl group, the amount of CH3OOH in the liquid-phase products was quantified using the working curve of CH3OH. The concentration of HCHO was determined by the acetylacetone colorimetric method (Supplementary Fig. 12). In general, a portion of the post-reaction samples (3 mL) was mixed with the as prepared 0.25% (v v−1) acetylacetone solution (2 mL) before being heated for 3 minutes in boiling water. The amount of HCHO is obtained by measuring the absorbance at 412 nm on a UV-Vis spectrophotometer (Hitachi 3010).

Gaseous products (CO and CO2) were quantified by gas chromatography-mass spectrometry (Agilent 7890B GC- 5977B MS) (Supplementary Figs. 13a–d). H2 was identified by a Shimadzu GC-2014 gas chromatography system equipped with a flame ionization detector (FID) using an MS-5A packed column (Supplementary Fig. 13e). The conversion rate of methane was calculated using the Eq. (1):

in which the initial amounts of CH4 were determined by GC (GC7900, Timex) (Supplementary Fig. 13f). For isotopic reaction, ≥ 98% 18O-enriched O2, 18O-enriched H218O and D2O were used to trace the source of oxygen and hydrogen in the products. The 18O2 isotope experiment is introduced in the atmosphere (P18O2 = 0.1 bar, PCH4 = 0.1 bar, and PN2 = 0.8 bar), and the H218O experiment is to add 1 ml to 19 ml H2O.

The detection of radicals

We employed 5,5-dimethyl-1-pyrrolineN-oxide (DMPO) as a radical trapping agent to identify •OH, •OOH, and •CH3 radicals in the reaction system. In detail, 100 μL of DMPO was added to 10 ml of DI water or methanol. The solution was bubbled with different types of gases (CH4/N2, CH4/O2/N2,), and after applying an external field (sonication or stirring), the free radicals were characterized using the electron paramagnetic resonance (EPR) technique (Bruker EMX NANO Desktop). Terephthalic acid (TA) is an effective probe molecule for •OH radicals. It reacts with •OH radicals to generate 2-hydroxyterephthalic acid (TAOH), which emits strong fluorescence at 452 nm (excited at 315 nm). Therefore, the quantification of •OH radicals can be achieved by observing the fluorescence intensity of TAOH in the reaction solution at 452 nm (the excitation wavelength is 315 nm).

Simulation and computational details

To simulate the influence of the eddy current field on the sound field distribution, the finite element method (FEM) was employed. The multiphysics coupling was achieved by solving the relevant partial differential equations. The flask used in this experiment is a 250 mL three-necked flask with a spherical bottom. The flask’s shape primarily distinguishes the inner and outer fluid domains, creating a discontinuity at the flask boundary between the inner and outer liquids, which indirectly affects the acoustic field. In the simulation, the flask model is treated as a thin-walled material with equivalent acoustic impedance (Zn = 1.25 × 107 Pa s m−1), and acoustic impedance boundary conditions are applied to the inner and outer walls to simulate sound wave reflection at the boundary. The entire simulation process is divided into two steps: the first is to calculate the fluid distribution, including flow velocity and pressure fields; the second is to map the material distribution and flow velocity after the liquid surface changes and input this information into the ultrasonic propagation model. It is worth noting that the RBF function is not directly used for wave propagation, but for interpolating the liquid surface shape, with interpolation data derived from a large set of three-dimensional phase intermediate values obtained through two-phase flow calculations, to achieve a sharp gas-liquid interface. Using RBF to interpolate the liquid surface shape ensures an accurate representation of the free surface in the ultrasonic propagation simulation. This is crucial for sound wave propagation because when sound waves are reflected at the liquid-gas interface, the interface shape directly influences the path and intensity of the sound waves.

Molecular dynamics simulations were employed to investigate the oxidation process of CH4 under ultrasonic conditions. The initial structure for the simulations was constructed using the Packmol program45. 50 methane molecules, 50 oxygen molecules, and 387 water molecules were randomly placed into a cubic box with a side length of 2.5 nm. This was then used as the initial structure for the molecular dynamics simulations carried out in the LAMMPS program package46. One distinct simulation was conducted to explore the effects of ultrasonic treatment on the oxidation process. In the simulation, a periodic ultrasonic-like perturbation was introduced by periodically heating the system to 4000 K every 50 ps. This periodic heating protocol was designed to mimic the transient high-temperature and pressure conditions typically associated with ultrasonic treatment. The Reactive force field (ReaxFF) was employed to describe the reactive interactions among the molecules, allowing for the dynamic formation and breaking of chemical bonds during the simulation. This approach enabled us to capture the complex oxidation chemistry of CH4 under the simulated conditions. ReaxFF parameters provided by Castro-Marcano, Weismiller47 and Chenoweth48 were chosen to provide a comprehensive understanding of the reaction mechanisms and kinetics involved in the ultrasonic-assisted oxidation of CH4. The isothermal isochoric (NVT) ensemble was employed to simulate 60,000,000 steps with the time step of 0.1 ps, corresponding to a total simulation time of 600 ps. Throughout the simulations, the time step was set to 0.10 fs. The bond order cut-off was set to 0.30, which meant that two atoms were considered to have no chemical bond when their bond order was < 0.30. This was also the threshold for determining the presence of chemical bonds when counting the number of molecules.

Data availability

The main data supporting the findings of this study are available within the article and its Supplementary Figures. The source data underlying Figs. 1, 3 and 4 and Supplementary Figs. 1,2, 7–10, 12 and 13 are provided as a Source Data file. The initial and final configurations for molecular dynamics trajectories are supplied as a separate file labeled ‘Supplementary Data 1’. Source data are provided in this paper.

References

Schwach, P., Pan, X. & Bao, X. Direct conversion of methane to value-added chemicals over heterogeneous catalysts: Challenges and prospects. Chem. Rev. 117, 8497–8520 (2017).

Tian, J. et al. Direct conversion of methane to formaldehyde and CO on B2O3 catalysts. Nat. Commun. 11, 5693 (2020).

Dummer, N. F. et al. Methane oxidation to methanol. Chem. Rev. 123, 6359–6411 (2023).

Li, X., Wang, C. & Tang, J. Methane transformation by photocatalysis. Nat. Rev. Mater. 7, 617–632 (2022).

Yuan, S. et al. Conversion of methane into liquid fuels-bridging thermal catalysis with electrocatalysis. Adv. Energy Mater. 10, 2002154 (2020).

Zhou, Y., Zhang, L. & Wang, W. Direct functionalization of methane into ethanol over copper modified polymeric carbon nitride via photocatalysis. Nat. Commun. 10, 506 (2019).

Cao, W. et al. Catalyst-free activation and fixation of nitrogen by laser-induced conversion. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 146, 14765–14775 (2024).

Wang, Y. et al. Catalyst-free nitrogen fixation by microdroplets through a radical-mediated disproportionation mechanism under ambient conditions. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 147, 2756–2765 (2025).

Yan, B. et al. Efficient and rapid hydrogen extraction from ammonia-water via laser under ambient conditions without catalyst. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 146, 4864–4871 (2024).

Yan, B. et al. Laser direct overall water splitting for H2 and H2O2 production. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 121, e2319286121 (2024).

Lee, K. et al. Catalyst-free selective oxidation of C(sp3)-H bonds in toluene on water. Nat. Commun. 15, 6127 (2024).

Song, X., Basheer, C. & Zare, R. N. Water microdroplets-initiated methane oxidation. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 145, 27198–27204 (2023).

Yusof, N. S. M. et al. Physical and chemical effects of acoustic cavitation in selected ultrasonic cleaning applications. Ultrason. Sonochem. 29, 568–576 (2016).

Dehghani, M. H. et al. Recent trends in the applications of sonochemical reactors as an advanced oxidation process for the remediation of microbial hazards associated with water and wastewater: A critical review. Ultrason. Sonochem. 94, 106302 (2023).

Henglein A. Sonolysis of carbon dioxide, nitrous oxide and methane in aqueous solution. 40, 100–107 (1985).

Dehane, A. & Merouani, S. Microscopic analysis of hydrogen production from methane sono-pyrolysis. Energies 16, 443 (2023).

Kojima, Y., Asakura, Y., Sugiyama, G. & Koda, S. The effects of acoustic flow and mechanical flow on the sonochemical efficiency in a rectangular sonochemical reactor. Ultrason. Sonochem. 17, 978–984 (2010).

Hatanaka, S. -i, Mitome, H., Yasui, K. & Hayashi, S. Multibubble sonoluminescence enhancement by fluid flow. Ultrasonics 44, E435–E438 (2006).

Aghelmaleki, A., Afarideh, H., Cairós, C., Pflieger, R. & Mettin, R. Effect of mechanical stirring on sonoluminescence and sonochemiluminescence. Ultrason. Sonochem. 111, 107145 (2024).

Jüschke, M. & Koch, C. Model processes and cavitation indicators for a quantitative description of an ultrasonic cleaning vessel: Part I: Experimental results. Ultrason. Sonochem. 19, 787–795 (2012).

Sidnell, T., Caceres Cobos, A. J., Hurst, J., Lee, J. & Bussemaker, M. J. Flow and temporal effects on the sonolytic defluorination of perfluorooctane sulfonic acid. Ultrason. Sonochem. 101, 106667 (2023).

Yasuda, K., Tachi, M., Bando, Y. & Nakamura, M. Effect of liquid mixing on performance of porphyrin decomposition by ultrasonic irradiation. J. Chem. Eng. Jpn. 32, 347–349 (1999).

Bussemaker, M. J. & Zhang, D. A phenomenological investigation into the opposing effects of fluid flow on sonochemical activity at different frequency and power settings. 1. Overhead stirring. Ultrason. Sonochem. 21, 436–445 (2014).

Bussemaker, M. J. & Zhang, D. A phenomenological investigation into the opposing effects of fluid flow on sonochemical activity at different frequency and power settings. 2. Fluid circulation at high frequencies. Ultrason. Sonochem. 21, 485–492 (2014).

Zhang, X. et al. Studied on sonocatalytic degradation of Rhodamine B in aqueous solution. Ultrason. Sonochem. 58, 104691 (2019).

Nie, G. et al. Mechanical agitation accelerated ultrasonication for wastewater treatment: Sustainable production of hydroxyl radicals. Water Res. 198, 117124 (2021).

Shchukin, D. G., Skorb, E. & Belova, V. Moehwald H. Ultrasonic Cavitation at Solid Surfaces. Adv. Mater. 23, 1922–1934 (2011).

Qin, D. et al. Numerical investigation on acoustic cavitation characteristics of an air-vapor bubble: Effect of equation of state for interior gases. Ultrason. Sonochem. 97, 106456 (2023).

Nanzai, B. et al. Sonoluminescence intensity and ultrasonic cavitation temperature in organic solvents: Effects of generated radicals. Ultrason. Sonochem. 95, 106357 (2023).

Braeutigam, P. et al. Degradation of carbamazepine in environmentally relevant concentrations in water by Hydrodynamic-Acoustic-Cavitation (HAC). Water Res. 46, 2469–2477 (2012).

Asakura, Y. & Yasuda, K. Frequency and power dependence of the sonochemical reaction. Ultrason. Sonochem. 81, 105858 (2021).

Pflieger, R., Nikitenko, S. I. & Ashokkumar, M. Effect of NaCl salt on sonochemistry and sonoluminescence in aqueous solutions. Ultrason. Sonochem. 59, 104753 (2019).

Wood, R. J., Lee, J. & Bussemaker, M. J. Combined effects of flow, surface stabilisation and salt concentration in aqueous solution to control and enhance sonoluminescence. Ultrason. Sonochem. 58, 104683 (2019).

Wall, M., Ashokkumar, M., Tronson, R. & Grieser, F. Multibubble sonoluminescence in aqueous salt solutions. Ultrason. Sonochem. 6, 7–14 (1999).

Zhou, Y. et al. Direct piezocatalytic conversion of methane into alcohols over hydroxyapatite. Nano Energy 79, 105449 (2021).

Jia, T., Wang, W., Zhang, C., Zhang, L. & Wang, W. Polydopamine-mediated contact-electro-catalysis for efficient partial oxidation of methane. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 64, e202413343 (2024).

Li, W. et al. Contact-electro-catalysis for direct oxidation of methane under ambient conditions. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 63, e202403114 (2024).

Jia, T. et al. An efficient strategy for the partial oxidation of methane into methanol over POM-immobilized MOF catalysts under ambient conditions. Appl. Catal. B Environ. Energy 340, 123168 (2024).

Luo, L. et al. Nearly 100% selective and visible-light-driven methane conversion to formaldehyde via. single-atom Cu and Wδ+. Nat. Commun. 14, 2690 (2023).

Song, H. et al. Direct and selective photocatalytic oxidation of CH4 to oxygenates with O2 on cocatalysts/ZnO at room temperature in water. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 141, 20507–20515 (2019).

Fan, Y. et al. Selective photocatalytic oxidation of methane by quantum-sized bismuth vanadate. Nat. Sustain. 4, 509–515 (2021).

Luo, L. et al. Binary Au-Cu reaction sites decorated ZnO for selective methane oxidation to C1 oxygenates with nearly 100% selectivity at room temperature. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 144, 740–750 (2022).

Liu, L., Wen, J., Yang, Y. & Tan, W. Ultrasound field distribution and ultrasonic oxidation desulfurization efficiency. Ultrason. Sonochem. 20, 696–702 (2013).

Wood, R. J., Vévert, C., Lee, J. & Bussemaker, M. J. Flow effects on phenol degradation and sonoluminescence at different ultrasonic frequencies. Ultrason. Sonochem. 63, 104892 (2020).

Martinez, L., Andrade, R., Birgin, E. G. & Martinez, J. M. PACKMOL: A package for building initial configurations for molecular dynamics simulations. J. Comput. Chem. 30, 2157–2164 (2009).

Thompson, A. P. et al. LAMMPS-a flexible simulation tool for particle-based materials modeling at the atomic, meso, and continuum scales. Comput. Phys. Commun. 271, 108171 (2022).

Weismiller, M. R., van Duin, A. C. T., Lee, J. & Yetter, R. A. ReaxFF reactive force field development and applications for molecular dynamics simulations of ammonia borane dehydrogenation and combustion. J. Phys. Chem. A 114, 5485–5492 (2010).

Chenoweth, K., van Duin, A. C. T. & Goddard, W. A. III. ReaxFF reactive force field for molecular dynamics simulations of hydrocarbon oxidation. J. Phys. Chem. A 112, 1040–1053 (2008).

Acknowledgements

We acknowledge the financial support from the National Natural Science Foundation of China (No. 52032001) received by G.Z., National Natural Science Foundation of China (51972325, 52172256) received by W.W., and National Natural Science Foundation of China (52372248) received by L.Z.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Y.P. and W.W. conceived the idea, developed the outline, designed the experiment and compiled the manuscript. Y.P. conducted all the experiments and tests with the assistance of R.L., L.Z. and J.L. W.W. and G.Z. supervised the whole project.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Peer review

Peer review information

Nature Communications thanks Feng Ru Fan, Guandao Gao, Seonae Hwangbo, and the other anonymous reviewer(s) for their contribution to the peer review of this work. A peer review file is available.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Source data

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Pan, Y., Li, R., Zhang, L. et al. Catalyst-free partial oxidation of methane under ambient conditions boosted by mechanical stirring-enhanced ultrasonic cavitation. Nat Commun 16, 7506 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-025-62924-2

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-025-62924-2