Abstract

Sodium co-intercalation in graphite negative electrodes delivers high-rate kinetics, and yet its implementation is plagued by notorious reaction potential. While prior efforts reduce the co-intercalation potential, the design remains limited by the intrinsic properties of electrolyte. Herein, a flexible design strategy based on synergistically competitive coordination is developed to tailor co-intercalation potential in dilute ether systems. The electrolyte design simultaneously diminishes the size and number of intercalated solvents into graphite galleries that enable milder intercalation mechanism, distinctive intercalant distribution, and less stable Na-dimethyl ether coordination. Without sacrificing fast kinetics, the co-intercalation potential of graphite negative electrode is tailored to 0.4 V after incorporating dimethoxymethane, even reaching a level of 0.32 V at evaluated temperature (60 °C). The resultant promotion of average operating voltage and inheritable rate capability are verified in sodium-ion full batteries. This design concept is applicable for screening other sets of small-weak co-solvents and providing guidance for more potential regulation electrolytes.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Sodium-ion batteries are considered as a cost-effective alternative to lithium-ion batteries (LIBs)1. For negative electrodes, the electrochemical formation of binary Li+-graphite intercalation compounds exhibits low redox potential and long-term cyclability in commercial LIBs2,3. After migrating to the sodium system, the thermodynamic instability of Na+-graphite analog results in a negligible specific capacity lower than 30 mAh g-1 (ref. 4,5). In contrast to the bare Na+ ion, graphite host delivers good compatibility with solvated Na+ ions, forming reversible ternary graphite intercalation compounds (t-GICs)6,7,8. By virtue of the rapid mobility in the ether condition and expanded diffusion galleries, the co-intercalation mechanism shows extraordinary rate capability, which maintains 80% specific capacity at high specific current (5 A g−1)9,10. Nevertheless, the discharge plateaus of graphite negative electrodes are 0.6–0.8 V in a suite of traditional ether electrolytes, causing a plummet of output voltage in full cell11,12,13. Especially matching the low voltage Na0.7CoO2 as positive electrode, the operating voltage is only 2.2 V, which seriously hampered the energy density14. Hence, it is pivotal to tailor the co-intercalation potential for graphite negative electrodes in sodium-ion batteries.

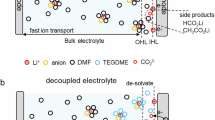

Considering the presence of solvent in t-GICs, the electrolyte chemistry has a profound imprint on decreasing the co-intercalation potential15. In particular, solvents with short chains were recognized to be an effective way, which tuned potential via the stronger repulsion between graphitic layers (Fig. 1a)6,16. The concentrated electrolyte with low activity of free solvents also reduced the co-intercalation voltage (Fig. 1b)16. Those two strategies follow the design principle to reduce the volume proportion of solvents in GICs via smaller molecular size or lower coordination number. However, limited by the chain length of ether molecules and salt solubility, the representative electrolyte recipe with the low reaction voltage (0.56 V) is 2 M NaPF6 in dimethyl ether (DME)16. Taking into account the high viscosity, the high concentration leads to the sacrifice of rate performance17,18. Even when introducing 1,3-dioxolane (DOL) diluent, the threshold potential was reported to be 0.51 V at room temperature, which is still a high value19. Furthermore, the underlying intercalants into graphite negative electrodes during phase transition need to be revealed. Therefore, an electrolyte design principle between phase evolution and solvation structure is desirable to optimize the co-intercalation behavior.

In this work, we proposed an electrolyte concept of synergistically competitive coordination to diminish the solvent-involved volume in the graphitic interlayer, realizing the regulation of co-intercalated potential. The small size dimethoxymethane (DMM) co-solvent with weak solvation is incorporated with conventional DME solvent, where weak solvated DMM increases the amount of \({{{\rm{PF}}}}_{{6}^{\mbox{-}}}\) in Na solvation cluster and the small DMM competitively substitutes part of coordinated DME to form quaternary graphite intercalation compounds (q-GICs) (Fig. 1c). In the optimized electrolyte formulation of 1 M NaPF6 D1M2 (DME:DMM = 1:2 in volume), the co-intercalated potentials are reduced to 0.4 V at 25 °C and 0.32 V at elevated 60 °C. The correlation of solvation environment, phase transformation of q-GICs and resultant potential is established by systematic investigation of electrolyte chemistry, mild interlayer expansion, and less stable Na-DME coordination (Fig. 1d). Furthermore, we screen other small and weak solvents to verify the generality of this competitive coordination concept, guiding the flexible electrolyte design for co-intercalation.

Results

Electrolyte design and electrochemical performance

The ideal electrolyte for co-intercalation should fulfill the following criteria: (1) efficacious solvating ability to ensure solvent participation, (2) high cathodic stability to alleviate the interphasial barrier, and (3) minimized solvent occupation to reduce the redox potential16,20,21. However, whether molecular size regulation by shortened chain length or coordination number manipulation via high concentration, the reported efforts are limited by the intrinsic properties of the electrolyte16,19. The incorporation of a weak solvent promotes the competitive coordination of anions in a solvated shell, and the anions would be repelled in the charged graphite host22. The ligancy of small co-solvent with weak solvation further reduces the number and the size of co-intercalation reagents. This design concept is the competitive coordination enabled by the synergy effect of anions and small co-solvent, which reduces the quantity and scale of solvent occupation in the sodiated graphite synchronously, and it is expected to achieve low ternary intercalation potential in dilute ether electrolyte.

Considering the effect of solvent chain length on potential, we select short DME as the starting solvent. The motivation of electrolyte design is to enable lower solvation ability and smaller solvent size simultaneously. Hence, a methylene in the DME backbone is removed to obtain DMM, and the chelation effect of strong solvent DME is eliminated23 (Supplementary Fig. 1). The weak solvated properties of DMM with a low dielectric constant have been reported in lithium metal batteries24,25. In our designed 1 M NaPF6 D1M2 electrolyte, a portion of strong solvent DME was retained to ensure solvent co-intercalation, and the blended co-solvent DMM with weak solvation enabled the low intercalant volume into graphite galleries. Compared to 1 M NaPF6 DME control electrolyte, the co-intercalation plateau decreases from 0.58 V to 0.4 V in 1 M NaPF6 D1M2 (Fig. 2a). This significant regulation of potential was also indicated by galvanostatic intermittent titration technique (GITT) curves (Supplementary Fig. 2). Furthermore, the cyclic voltammetry (CV) curves showed the shift of redox peaks to low voltage in 1 M NaPF6 D1M2 (Fig. 2b). Those above results were collected in Na | |graphite cell configuration, where the potential may be susceptible to the Na metal reference electrode. Thus, the CV results were recalibrated using the three-electrode system with 4 mM ferrocene as the internal standard (Supplementary Fig. 3)25. A significant reduction of co-intercalation potential was still observed, confirming the effectiveness of a small co-solvent with weakly solvated ability.

a The 2nd galvanostatic charge and discharge (GCD) curves at 100 mA g−1. b The CV curves at the scan rate of 0.2 mV s−1. c The rate performance from 0.05 A g−1 to 5 A g−1. d The long-term cyclic stability at 100 mA g−1. e The dQ/dV curves at evaluated temperatures (45 °C and 60 °C). f The summary of co-intercalation potential (vs. Na/Na+) at different temperatures (from 25 °C to 60 °C).

In the optimized D1M2 electrolyte, the discharge curve of the graphite negative electrode mirrors that of the DME electrolyte, characterized by three discharge regions: a slope at high potential (2 V to plateau), a co-intercalation plateau and a slope at low potential (plateau to 0.01 V). In addition, a short plateau at the end of discharge (around 0.01 V) slightly increased the specific capacity of graphite to 116 mAh g−1, which is corroborated by the small redox pair in the CV curve. It has been generally known that the poor ionic conductivity of weak solvents adversely impacts kinetic performance26,27,28. After comparing the specific capacity retention at high specific current, the rate capability is not significantly hampered, which maintained 106 mAh g−1 at 5 A g−1 (70 s per cycle) in D1M2 electrolyte (Fig. 2c). This privilege may be attributed to the rapid co-intercalation mechanism and blend of strong solvent. Besides rate performance, the cyclic stability of ternary intercalation is still high after being mixed with DMM, and there is no obvious specific capacity decay after 1000 cycles (Fig. 2d and Supplementary Fig. 4). Even under the higher specific current of 1 A g−1, a long-term stability is still maintained after 2000 cycles (Supplementary Fig. 5).

The co-intercalated voltage of graphite electrode is highly temperature-dependent in conventional ether electrolytes, where a lower potential is observed at higher temperatures16. To realize the lower potential, we further performed the graphite negative electrodes at evaluated temperatures of 45 °C and 60 °C (Supplementary Fig. 6). In both DME and D1M2 electrolytes, the sodiated/de-sodiated peaks in differential capacity (dQ/dV) curves show a negative shift (Fig. 2e), demonstrating that high temperature reduces the reaction potential of co-intercalation graphite. When the temperature is evaluated to 60 °C, the co-intercalation potential of graphite in D1M2 electrolyte even decreased to 0.32 V. Such a reduced potential is highly competitive compared with previous reports (Supplementary Table 1). Fig. 2f summarizes the strong tendency of the co-intercalation potential to temperature in those two electrolyte systems. The above electrochemical performance confirms that the optimized electrolyte (1 M NaPF6 D1M2) effectively reduces reversible co-intercalation potential in dilute ether electrolyte without sacrificing rate and cyclic stability. The optimized electrolyte formulation is described as a small-weak cosolvent blended with a strong solvent.

Phase evolution of sodiated graphite

The large occupied volume of co-intercalated solvents would result in a high potential, which originates from the weaker repulsion force between graphitic interlayers to stabilize t-GICs16. To gain deeper insight into the potential regulation, the co-intercalation phase transition of graphite was elucidated by operando X-ray diffraction (XRD). The graphite negative electrodes display similar ternary intercalation evolution with high reversibility in both DME and D1M2 electrolytes (Supplementary Fig. 7). At the initial discharge process (Fig. 3a), the splitting of the (002) peak in pristine graphite indicated the formation of high-staged GICs. Subsequently, the diffraction peaks shifted into higher and lower angles until the emergence of stage 2 GICs, corresponding to the (004) and (005) peaks. With the deeper discharge at 0.4 V, the stage 2 GICs transformed into stage 1 GICs, which are indexed as (002), (003), and (004)6. The starting position of the co-intercalation plateau is the coexistence state of stage 2 and stage 1 GICs, that is, the structure evolution in the plateau region is the transition from stage 2 GICs to stage 1 GICs. In stark contrast to 0.58 V in DME, the phase transition potential of the graphite negative electrode in the D1M2 electrolyte is 0.4 V (Fig. 3b). As shown in Fig. 3c and d, the pronounced differences in peak shifts explain the regulation of reaction potential. In 1 M NaPF6 D1M2 electrolyte, the characteristic peaks of stage 2 GICs are located at 23.57 ° and 29.74 ° (blue curve). The diffraction peaks are higher than those of GICs in DME, demonstrating the milder phase evolution in the optimized D1M2 electrolyte. In addition, the stage 1 GICs also deliver a milder variation of peak position, suggesting the smaller volume expansion of solvent-involved intercalation in the D1M2 electrolyte. Even in the high-staged GICs, this discrepancy was observed, accompanied by the different starting voltages in the high-potential slope region. These results indicated the correlation between lower redox potential and milder formation of GICs in the designed D1M2 electrolyte.

a, b Contour plots of operando XRD and corresponding 2nd GCD profiles in 1 M NaPF6 DME (a) and 1 M NaPF6 D1M2 (b) The empty circles marked on the GCD profile correspond to respective staging states of the graphite electrode, where green is pristine graphite, blue is stage 2 GICs, pink is stage 1 GICs, and purple is final stage 1 GICs. c, d Magnified views of representative regions in XRD patterns (marked as line boxes in a and b). The left-most panels show the discharge process in the first 40 min, and the other panels include both 2nd charge and the discharge process. e The Ic values at different states of charge (SOC), where SOC100 is fully sodiated and SOC60 is at the plateau region. f, g In situ Raman spectra at representative potentials in 1 M NaPF6 DME (f) and 1 M NaPF6 D1M2 (g).

To further quantify the effect of DMM co-solvent on volume occupancy, the lattice parameter (Ic) was extracted from the peak position (Fig. 3e). Ic is the repeatable distance of each staged GIC (Supplementary Fig. 8), with the detailed calculation shown in Supplementary Note 16,29. The 60% state of charge (SOC60, sodiation) is the plateau in the GCD curves, which corresponds to the initial formation of stage 1 GICs. At SOC60, the Ic of values stage 1 GICs are 11.80 Å and 11.65 Å in the DME and D1M2 electrolytes, respectively. This result indicates that DMM co-solvent facilitates a reduction in the occupied volume of intercalant with narrower interlayer distances. During the process of discharge, the Ic value declined, which is consistent with the shift of the diffraction peak. The Ic of the final stage 2 and stage 1 GICs in DME electrolyte are 14.74 Å and 11.63 Å, respectively. As a contrast, the values of Ic in the D1M2 electrolyte are slightly diminished to 14.66 Å and 11.57 Å. To complement the structural analysis, in situ Raman spectra were implemented to assist in interpreting the co-intercalation mechanism (Supplementary Fig. 9). The division of the G peak is characteristic of judging the formation of high-staged GICs, where the G peak is graphitic carbon, and the G’ peak is sodiated carbon30,31,32 (Fig. 3f, g). The splitting potential of the G peak in D1M2 is significantly lower, in good consistency with XRD results, which suggests the different formation potential of high-staged GICs. As a consequence, the introduction of DMM co-solvent mitigates the solvent-involved expansion of graphitic interlayer, especially the phase transition from stage 2 GICs to stage 1 GICs, which is beneficial to weaken the stability of q-GICs and decrease the co-intercalated potential.

Solvation structure in bulk electrolyte

The phase transformation of co-intercalation is determined by the solvated Na+, thus we investigate the solvation structure of the bulk electrolyte to understand the effect of a small-size weak co-solvent. Firstly, the solvation structure of bulk electrolytes was evaluated by the molecular dynamic (MD) simulation (Supplementary Data 1–4), as depicted in Fig. 4a. As shown in the radial distribution function plots (Fig. 4b, c), the DME solvents (Na-ODME) and PF6- anions (Na-FPF6) exhibit strong coordination with Na+ in the first solvation shells at 2 and 3.4 Å. In contrast, the weaker solvation power of DMM is indicated in the primary solvation shell, which serves as a co-solvent to reduce the coordination number (CN) of DME and increase the PF6- contacted with Na+ (Fig. 4c). This solvation structure is consistent with our design rationales that strong solvated DME is dominant to ensure the co-intercalated mechanism and weak interaction of DMM co-solvent causes low CN of DME. From the perspective of molecular and ion interaction, the low CN of DME solvent in the D1M2 system is governed via the competitive coordination enabled by the synergy effect of DMM and PF6-.

a The most probable solvation structure extracted from MD simulation. b, c Na+ radial distribution function obtained from MD simulation of 1 M NaPF6 DME (b) and 1 M NaPF6 D1M2 (c). d, e The Raman spectra of electrolytes and their components from the region of 725–785 cm−1 (d) and 810–890 cm−1 (e). f 23Na NMR obtained in the coaxial tube with NaCl external calibration. g The X-ray photoelectron spectroscopy (XPS) of cycled graphite in these two systems.

Raman spectra have provided additional insight to support this solvation structure, as shown in Fig. 4d, e. From the region of 725–785 cm−1, a major peak at 765 cm−1 is indicated as the vibration of the P-F bond in NaPF633. After the NaPF6 salt is dissolved in the DME solvent, the redshift of the vibration peak corresponds to the formation of solvated Na+. In contrast, a slight blue shift is observed after blending with DMM, confirming the enhanced interaction between Na+ and PF6- anions. The coordination of DME solvent in 1 M NaPF6 DME comprised of free DME at 850 cm−1 and solvated DME at 865 cm−1 in Fig. 4e18. After blending with DMM, the solvation structure is dominated by the coordination DME with a smaller amount of the free DME conformer (Supplementary Fig. 10), which also indicates the increasing local salt concentration. Furthermore, the MD simulation predictions were validated by the 23Na nuclear magnetic resonance spectroscopy (NMR). In 1 M NaPF6 D1M2 electrolyte, the upfield of 23Na chemical shift is determined by the stronger electron density around Na+, owing to the enhancement of PF6- anion coordination34. In general, the intercalation behavior of graphite negative electrodes is strongly dependent on the desolvation effect of interphase17,21,35. A similar interphase chemistry on cycled graphite was produced in these two systems, eliminating its influence on potential regulation (Fig. 4g and Supplementary Fig. 11). To further confirm the limited effects of interphase, the precycled graphite negative electrode in D1M2 system was reassembled with the DME electrolyte, and it delivered a high co-intercalated potential at 0.58 V (Supplementary Fig. 12). In this sense, our hypothesis is proposed that solvation structure via synergistic competition is the root of reduced co-intercalation potential and milder expansion of graphitic interlayer.

Distribution of intercalants in graphitic galleries

The state of intercalants in GICs is critical to confirm the effect of bulk solvation structure on the phase evolution of sodiated graphite, especially the number of co-intercalated solvents. Under realistic testing conditions, the electric double-layer on the electrode has been universally acknowledged to dictate solvation structure36,37. To verify the hypothesis above, the intercalated solvated Na+ in GICs was simulated under an applied electric field, especially in stage 1 and stage 2 GICs (Supplementary Data 5–12). As shown in Supplementary Fig. 13 and Supplementary Table 2, the model of GICs is constructed based on the co-intercalation potential and interlayer distance from XRD in Fig. 3. In the presence of an electric field, the seldomly participated PF6- and retained solvent coordination was found in GICs (Supplementary Fig. 14 and Supplementary Table 3), as summarized in Fig. 5a. This indicated that Na+ solvated shell undergoes anion repulsion and desolvation absence in negatively charged graphite, thus the merit of synergistic competitive coordination in bulk D1M2 electrolyte was inherited. Compared with the DME system, the solvent CN of stage 2 GICs (corresponding to the plateau in Fig. 2a) decreased by 0.7 in 1 M NaPF6 D1M2 electrolyte (Fig. 5d). In addition, the incorporated DMM slightly increases in stage 1 GICs, and the small size is beneficial to lessen its occupied volume. Therefore, the milder gallery expansion of sodiated graphite stemmed from the decreased DME and the introduced DMM co-solvents with a small size.

a, d The coordination number of Na+ for the bulk electrolyte and intercalants in 1 M NaPF6 DME (a) and 1 M NaPF6 D1M2 systems (d). b, e The distribution of intercalant ingredients into graphite galleries in 1 M NaPF6 DME (b) and 1 M NaPF6 D1M2 systems (e). c, f The intercalated DME density of stage 2 GICs in 1 M NaPF6 DME (c) and 1 M NaPF6 D1M2 systems (f). The x denoted the vertical direction of the graphite layer. g 1H NMR spectra of graphite negative electrodes with different SOCs in 1 M NaPF6 D1M2. The spectra were collected in DMSO-d6 and referenced to DMSO-d6 at 2.50 ppm. h The integral area of DME in 1H NMR spectra. The peaks are located at 3.41 ppm and 3.23 ppm. i The survival probability function of Na-DME in stage 2 and stage 1 GICs.

The distribution of intercalants in the graphite host is more intuitive to decipher the impact of blended DMM co-solvent on GICs. As shown in Fig. 5b and e, the distribution states of stage 2 GICs are distinct in these systems, which changed from solvent-Na+-solvent in DME to Na+-solvent-Na+-solvent-Na+ in D1M2. The semblable state demanded a lower potential to attain in DME electrolyte, such as stage 1 GICs. This trend is more intuitive in the co-intercalated Na+ density of stage 2 GICs (Supplementary Fig. 15), where a single Na+ layer in the DME-based system and a three-layer distribution in D1M2. In the DME electrolyte, the different distribution of three-layered Na+ is observed after the formation of stage 1 GICs (Supplementary Fig. 16). Moreover, the co-intercalation number of DME is significantly reduced in the D1M2 system, especially for the central layer in Fig. 5c and f. This improved intercalation mechanism is maintained up to full-sodiated graphite in Supplementary Fig. 17. DMM co-solvent was also observed in the interlayer (Supplementary Fig. 18), which is consistent with the CN results. Such co-intercalation of two solvents has been reported in the diglyme electrolyte with tetrahydrofuran (THF) as diluents, which is called q-GICs38. To further authenticate the reliability of the MD simulation results, we extracted intercalants between graphite galleries via DMSO-d6 and conducted 1H NMR to ascertain the change in the types and amount of co-intercalated solvents. For the sample preparation, several graphite electrodes (the total mass is around 19.8 mg) were used to collect the co-intercalated solvents, and the graphite negative electrodes after resting as the SOC0 were disassembled to eliminate the interference of residual solvents. As shown in Fig. 5g and Supplementary Fig. 19–20, the single peak for DMM molecules at 4.44 ppm intensified with deeper SOCs, confirming the co-intercalated DMM solvents during sodiation. As for DME solvents, the integral area of two single peaks at 3.41 ppm and 3.23 ppm was normalized by integration of DMSO-d6 at 2.50 ppm (Supplementary Fig. 21). During the discharging process, the increment of DME signal inside graphitic layers was significantly higher in the DME systems than in the D1M2 electrolyte (Fig. 5h), further supporting that the incorporation of DMM co-solvents causes the diminishing of co-intercalated DME number.

Beyond structural observations, the thermodynamic stability of GICs is the ultimate clincher for reaction potential, as reported16. The survival probability functions of Na-DME in the stage 1 and stage 2 GICs were calculated to assess the stability of GICs (Fig. 5i). At the same time duration, the survival probability in DME systems was higher than that of D1M2 electrolyte in both staged GICs, indicating a more stable Na-DME coordination in the DME systems. These results show that the electrolyte design of synergistically competitive coordination would weaken the stability of q-GICs to decrease the co-intercalated potential38.

Overall, combining both theoretical and experimental results, the correlation of solvation structure, phase evolution and co-intercalation potential is systematically understood. In the bulk electrolytes, the introduction of a small, weak co-solvent delivers a synergistically competitive coordination of anions and DMM to diminish the solvated DME. During the sodiated process, the anions are repelled out of the solvation shell under the electric field, and the intrinsically small molecular size of DMM contributes to a milder intercalation mechanism characterized by mitigated interlayer expansion. The improved co-intercalated reaction in the D1M2 systems presents the distinctive distribution of intercalants and a small occupied volume of co-intercalated solvents. The weak stability of q-GICs after blending with DMM co-solvents originates from the shorter interlayer distance and less stable Na-DME structure in the staged q-GICs, enabling the starkly decreased co-intercalated potential.

Generality of design concept

According to the dependence of the potential regulation mechanism on optimizing solvation structure, the co-intercalation potential of graphite negative electrodes shows noticeable relevance with volume fraction of DMM co-solvent (Fig. 6a and Supplementary Fig. 22). Accompanied by more DMM substitute, the redox peaks shift to low voltage, stemming from the enhanced competitive coordination (Supplementary Fig. 23). Until an inflection point at DME:DMM = 1:4 (in volume), the electrochemical performance undergoes severe polarization. The emergence of this behavior highlights the necessity of strong solvents to reversible sodiation and desodiation, as a similar report in THF electrolyte39. To confirm the feasibility of the regulation strategy, we further applied DMM co-solvent to the higher-concentration electrolyte, which was plagued by poor kinetics, as shown in Supplementary Fig. 24. After incorporating DMM weak solvent, the 2 M electrolyte also exhibited significantly decreased potential and inflection point at DME/DMM (1:2 in volume). The co-intercalation potential of the graphite negative electrode also reached the threshold value of 0.4 V in 2 M NaPF6 D1M1 conditions with optimized solvation structure (Supplementary Fig. 25).

a The dQ/dV curves of graphite negative electrodes in the electrolyte with different volume fractions of DMM. b The polarization and co-intercalation potential (vs. Na/Na+) of graphite negative electrodes in screened electrolyte systems, where D denotes DME, G denotes EGDEE, M denotes DMM, E denotes DEE, and the value is indicated by the corresponding volume fraction. The gray line and the area below it represent the normal polarization potential. c, d The GCD curves of NVP positive electrode (c) and graphite | |NVP full cell (d) at 100 mA g−1 in 1 M NaPF6 DME and 1 M NaPF6 D1M2. e Rate performance of graphite | |NVP full cell from 0.05 A g−1 to 2 A g−1. f Cycling performance of graphite | |NVP full cell at 1 A g−1 charge and discharge.

Furthermore, the understanding of this design concept guides us to screen co-solvents, favoring molecules with a small size and weak solvation ability. By minimizing the effect of steric hindrance, the dielectric constant serves as an effective descriptor of both solvent polarity and solvating ability of miscible solvents40. Thus, we select diethyl ether (DEE) solvent to validate the universality of the regulation principle (Fig. 6b), as shown in Supplementary Table 4 (physical properties of co-solvents)41,42,43. In both low and high-concentrated electrolytes, the linear ether (DEE) with a smaller size44 shows a comparable regulation degree with DMM co-solvent, that is, the formation potential of GICs decreased to 0.4 V in 1 M NaPF6 D1E2 and 2 M NaPF6 D1E1 (Supplementary Fig. 26). These findings confirm that DMM is not an accidental case. In addition, we utilize the ethylene glycol diethyl ether (EGDEE) as a cosolvent to emphasize the importance of molecular size, which is a weak solvent with a longer chain than DME42. As shown in Supplementary Figs. 27 and 28, the potential threshold is limited to 0.49 V in the 1 M NaPF6 D1G4 and 2 M NaPF6 D1G2, without significant regulation as the DMM or DEE systems. The co-intercalated reaction failed when using EGDEE as the sole solvent, which indicates the necessity of the presence of a strong solvent. The crucial effect of small molecular size was also confirmed by introducing 1,1,2,2-tetrafluoroethyl-2,2,2-trifluoroethyl ether (TFE) as a co-solvent, which is a common diluent with weak solvation and large size. As shown in Supplementary Fig. 29, the potential decreased to 0.52 V (threshold) under the condition of low blended TFE, and the large polarization was observed after adding excessive TFE co-solvents. All the potentials of co-intercalation and polarization in the designed electrolytes are summarized in Supplementary Table 5. Consequently, the concept of a strong solvent in conjunction with small-weak co-solvent is appliable to develop a flexible design of electrolyte, in which the suitable proportion of strong solvent and competitive coordination by small-weak co-solvent ensure the regulation of reversible intercalation mechanism.

Full cell evaluation

To estimate the potential regulation for electrochemical performance in a full cell, the commercial Na3V2(PO4)2 (NVP) serves as a positive electrode material. In these two electrolyte systems, no obvious divergence of voltage plateau and reversible specific capacity is shown in Fig. 6c, which are 3.35 V and 98 mAh g−1, respectively. The almost similar redox behavior illuminated the uncorrelation between the sodium storage mechanism of NVP and the electrolyte. The configuration of the Na-ion full cell is graphite negative electrodes with NVP positive electrodes. The discernible potential regulation was confirmed in these two systems, that is, the average voltage is elevated to 2.66 V in 1 M NaPF6 D1M2 electrolyte (Fig. 6d). Based on the mass of graphite negative electrodes, the specific capacity of a full cell is calculated to 110 mAh g−1 at 100 mA g−1. On the other hand, graphite | |NVP full cell inherited the fast kinetics with 107, 103, 99, 94.3, 89.4 and 81.1 mAh g−1 at the specific current of 0.05, 0.1, 0.2, 0.5, 1 and 2 A g−1, respectively (Fig. 6e and Supplementary Fig. 30). The specific capacity retention under high rate is highly 76% in the case of 1 M NaPF6 D1M2. The long-term cycling stability at 1 A g−1 also supports its rate capability in Fig. 6f. There is no severe attenuation after 500 cycles, with a specific capacity of 93 mAh g−1 and a low decay rate of 0.007% per cycle.

Discussion

In this work, the concept of synergistically competitive coordination is proposed to guide flexible electrolyte design with a small, weak cosolvent. This regulation mechanism is based on diminishing the size and number of co-intercalated solvents simultaneously. The incorporation of DMM substitutes the DME in the primary solvation sheath competitively and increases the probability of anion content, which undergoes repulsion under an electric field. The modified solvation structure advocated milder expansion during ternary intercalation, indicated by the decreased interlayer distance in operando XRD. Furthermore, the blended strategies of DME and small DMM endow a changed intercalant distribution (three-layer Na+) in the galleries of graphite host. The mitigated phase evolution and less stable Na-DME coordination in q-GICs are conducive to weakening the stability of q-GICs, which is critical for decreasing the co-intercalation potential. Therefore, 1 M NaPF6 D1M2 promises a low co-intercalation potential (0.4 V) of graphite negative electrodes in dilute ether electrolyte, and a higher average voltage is also validated in graphite | |NVP full cell. The level of co-intercalated potential at 0.32 V is further realized under the condition of elevated temperature. The effectiveness of this regulation mechanism is extended to other sets of small-weak co-solvent screening and higher concentrated electrolytes. This finding of synergistically competitive coordination motivates a flexible electrolyte design and a deep understanding of ternary intercalation behaviors.

Methods

Chemical reagents and materials

NaPF6 (purity ≥ 99.9%) salt, Polyvinylidene difluoride (PVDF 5130), super P, NVP materials, Cu collector (purity ≥ 99.9%, thickness 9 μm) and Al collector (purity ≥ 99.6%, thickness 15 μm) were purchased from Guangdong Canrd New Energy Technology Co. Ltd. DME (purity ≥ 99.9%) solvent and Na (purity ≥ 99.8%) metal were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich. DMM (purity ≥ 98%) and EGDEE (purity ≥ 98%) solvents were purchased from TCI. DEE (purity ≥ 99.7%) solvent was purchased from Yonghua Chemical Co. Ltd. DMSO-d6 (purity ≥ 99.9%) and N-Methylpyrrolidone (NMP, purity ≥ 99%) were purchased from Aladdin. Graphite materials were purchased from Shenzhen XFH Technology Co., Ltd.

Electrolyte and electrode preparation

Electrolytes were prepared and stored in an argon-filled glovebox with O2 and H2O levels below 0.1 ppm at 25 °C. All purchased solvents were purified by molecular sieves before use, and the sodium salt was dried in a vacuum for 12 h at 90 °C. During dissolution of the sodium salt NaPF6, all electrolytes were stirred with a magnetic stir bar at 25 °C for 1 h. Molarity (M, moles of salt in solvents, in mol L−1) is used to denote the concentration of the electrolyte, regardless of the volume of salt. After preparation, the electrolytes were stored in plastic bottles, transferred using polypropylene pipette tips, and the time interval between preparation and cell assembly was not exceeding two weeks. Before preparing the Na metal electrode, the native oxide layer on the Na ingot was mechanically stripped off. The Na metal electrode was prepared directly prior to cell assembly in an argon-filled glovebox with O2 and H2O levels below 0.1 ppm, and the Na metal was flattened by manual rolling with a steel rod to achieve the thickness about 120 μm. The graphite negative electrodes were prepared by casting the slurry with a mass ratio of 80% graphite, 10% super P, and 10% PVDF in NMP onto Cu foil. The NVP positive electrodes were prepared by mixing 94% NVP powders, 3% super P, and 3% PVDF onto Al foil, using NMP as solvent. All slurries were magnetically stirred for 4 h at 25 °C under air atmosphere and single-side coated using a doctor blade with a gap of 100 μm. After coating, the electrodes were dried at 80 °C in a forced-air oven for 6 h, then cut into discs using the MSK-T10 manual slicer (Shenzhen Kejing). All electrodes were further dried at 100 °C in a vacuum oven overnight before transferring to an argon-filled glovebox for cell assembling.

Cell assemble and electrochemical characterization

All electrochemical tests were performed in CR2032 coin-cells (case and spring materials: 304 stainless steel) assembled in an argon-filled glovebox with O2 and H2O levels below 0.1 ppm, where 90 μL electrolyte was transferred using a 200 μL micropipette with polypropylene tips. A glass fiber (Whatman, GF/A, thickness: 260 μm, porosity: 40%, average pore size: 1.6 μm) and a Celgard 2320 (thickness: 20 μm, porosity: 39%, average pore size: 0.027 μm) were the separators of the cells, with the glass fiber in contact with the negative electrode and Celgard 2320 in contact with the positive electrode. The GF/A separator was vacuum-dried at 100 °C for 24 h, and the Celgard 2320 separator was ultrasonically cleaned in ethanol for 30 min, followed by vacuum drying at 60 °C for 24 h. Both separators were cut into 19 mm-diameter discs using the MSK-T10 manual slicer (Shenzhen Kejing). Na | |graphite cells were configured using Na foil (diameter:12 mm) as the negative electrode and graphite (diameter:12 mm, mass loading: 1.3 mg cm−2) as positive electrode. Na | |NVP cells were configured using Na foil (diameter:12 mm) as the negative electrode and NVP (diameter:12 mm, mass loading: 1.9 mg cm−2) as positive electrode. All graphite||NVP full cells were assembled using graphite as the negative electrode and NVP as the positive electrode, with the N/P (the capacity ratio of the negative electrode to the positive electrode) of 1:1.5. Prior to electrochemical tests, the cells were rested for 8h to ensure complete wetting of the separator. For 100 mA g−1 cycle, rate capability test and 1 A g−1 cycle, the active mass loading of graphite negative electrodes are 1 mg−2, 1.8 mg cm−2 and 2 mg cm−2, respectively. The matched NVP positive electrodes are 1.8 mg−2, 3.3 mg cm−2 and 3.6 mg cm−2, respectively. The positive electrode is slightly larger than the negative electrode (16 mm for NVP and 12 mm for graphite). No presodiation was applied to the electrodes prior to assembly. GCD tests of Na | |graphite, Na | |NVP and graphite | |NVP cells were carried out on a LAND-2001A battery tester. The applied potential ranges are 0.01–2 V (vs. Na/Na+) for Na | |graphite, 2–3.8 V (vs. Na/Na+) for Na | |NVP, 0.7–3.3 V for graphite | |NVP (1 M NaPF6 DME), and 0.7–3.4 V for graphite | |NVP (1 M NaPF6 D1M2). The calculation for the specific capacity is based on the mass of the graphite negative electrode. The co-intercalation potentials were obtained from the sodiated peaks in dQ/dV curves, and each electrochemical test was performed with two cells with good reproducibility. For Na | |graphite cells, the CE is calculated as the ratio of charge capacity to discharge capacity, and it is the ratio of discharge capacity to charge capacity for other cells. The CV measurement of Na | |graphite was performed on a Solartron electrochemical workstation within the applied potential range of 0.01–2 V at 0.2 mV s−1. The GITT measurement was tested using a LAND2001A battery tester, with the applied potential range of 0.01–2 V. The detailed protocol was galvanostatic pulses at 20 mA g−1 for 10 min, followed by the relaxation process for 30 min, and the data points were acquired at an interval of 1 s per point. All electrochemical measurements were conducted in a thermostatic chamber (convection) at 25 ± 1 °C under ambient air, except for the high temperature tests.

Characterizations

Operando XRD was performed on Rigaku D/max-2500 with Cu Kα radiation (λ = 0.154 nm). The measured cells were assembled using graphite (mass loading: 2.5 mg cm−2) negative electrodes on Cu foam with a piece of glass fiber (Whatman, GF/B) as the separator. The volume of electrolyte was 350 μL to ensure the wettability in operando XRD devices, and the graphite side faced the direction of X-ray to enhance the intensity. The cells were open-circuit for 2 h before testing, and the specific current was 50 mA g−1. The collection rate of pattern data was 6 ° min−1 with a range from 10 to 40 °. In situ Raman spectra were collected by the HORIBA LabRAM HR800 spectrometer with a 532 nm argon laser. The sealed device contained a CR2032 cell configuration with a hole (diameter: 6 mm) on the positive electrode shell, and the electrode was prepared by 90% graphite and 10% PVDF without super P. The test specific current is 100 mA g−1, and the data were collected at special potential points from 1200 to 1800 cm−1.

The solvation structure of the electrolyte was measured in a capillary tube via Raman spectroscopy (Horiba LabRAM HR800, France) using a 532 nm laser at a scan range of 600–900 cm−1. 23Na NMR spectra of electrolytes were recorded by a Bruker 400 MHz instrument at 25 °C. The coaxial tube was used with measured electrolyte (400 μL) in the outer tube and 1 M NaCl in D2O (150 μL) in the inner tube as a standard solution. The XPS spectra were obtained by a PHI 5000 Versa probe II spectrometer using Al Kα X-ray source. The graphite negative electrodes after 10 cycles were rinsed with 60 μL DME (three times) and transferred via an inert atmosphere vacuum vessel. To eliminate the interference of conductive agents, the electrodes for the XPS test were no super P, which were prepared by 90% graphite and 10% PVDF. The time values in the XPS depth profiles were estimated based on the sputtering of SiO2. The obtained XPS data were calibrated based on the graphitic carbon peak at 284 eV in C 1 s. 1H NMR spectra of all samples were recorded at 25 °C on a Bruker 400 MHz instrument. The Na | |graphite cells were discharged to different SOCs and disassembled in an Ar-filled glove box. Multiple graphite electrodes with a total graphite mass of 19.8 mg were soaked in 500 μL DMSO-d6 for 12 h, and 200 μL supernatant of the extracted samples was injected into the NMR tube with 200 μL DMSO-d6. For graphite at SOC0, the Na | |graphite cells were resting for 24 h before disassembling. The sodiated graphite electrodes changed from blue to black after soaking, indicating the successful extraction of intercalants. All spectra were referenced to DMSO-d6 at 2.50 ppm for 1H NMR, and the integration of the DME signal was normalized by the integral of DMSO-d6 at 2.50 ppm.

MD simulations

MD simulations were performed via a modified MD package GROMACS, using the OPLS forcefields for ions, DME and DMM45,46. To account for charge transfer and polarizability effects in the condensed phase, partial charges were uniformly scaled by 0.7247. Electrostatic interactions were calculated using the Particle Mesh Ewald (PME) method48, and the Fourier transform (FFT) grid spacing was 0.12 nm. A cutoff distance of 1.2 nm was used to estimate the real-space electrostatic interaction. The leapfrog integration algorithm was performed to solve the equations of motion with a time step of 2 fs. For bulk electrolyte solvation structure, the simulation boxes contained 40 NaPF6 and 385 DME molecules, or 40 NaPF6 and 129 DME + 299 DMM molecules in 1 M NaPF6 DME and 1 M NaPF6 DME/DMM (1:2 in vol), respectively. During the 5 ns NPT simulations, the temperature was controlled at 298 K using the Nosé-Hoover thermostat with a coupling constant of 1 ps and the pressure was controlled at 1 bar using the Parrinello-Rahman barostat with a coupling constant of 10 ps. After the NPT simulation, a 10 ns NVT simulation was performed, and the last 5 ns results were utilized for radial distribution function (RDF) analysis. For the intercalant in GICs, the force fields from Cornell et al. were used to model the carbon electrode49. During simulations, the electric field was applied by the constant-potential method (CPM), allowing the charge fluctuations of carbon atoms50. 40 ns simulations were performed, and the last 5 ns results were used for statistical analysis. Each case was repeated three times with different initial configurations to certify the accuracy of the simulation results. The solvation structures were analyzed by a customized code in the C ++ language. The survival probability function is defined as refs. 47,51,52,53

where h(t) is the population variable defined as h(t) = 1 if the ion continuously remains in the same state during the time duration (t), and h(t) = 0 otherwise. Here in our work, this same state refers to cations maintaining coordination with DME/DMM.

Data availability

All data is available in the main text and Supplementary Information. Source data are provided in this paper.

References

Usiskin, R. et al. Fundamentals, status and promise of sodium-based batteries. Nat. Rev. Mater. 6, 1020–1035 (2021).

Qin, M. et al. Dipole–dipole interactions for inhibiting solvent co-intercalation into a graphite anode to extend the horizon of electrolyte design. Energy Environ. Sci. 16, 546–556 (2023).

Tu, S. et al. Fast-charging capability of graphite-based lithium-ion batteries enabled by Li3P-based crystalline solid–electrolyte interphase. Nat. Energy 8, 1365–1374 (2023).

Liu, Y., Merinov, B. V. & Goddard, W. A. Origin of low sodium capacity in graphite and generally weak substrate binding of Na and Mg among alkali and alkaline earth metals. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 113, 3735–3739 (2016).

Yoon, G., Kim, H., Park, I. & Kang, K. Conditions for reversible Na intercalation in graphite theoretical studies on the interplay among guest ions, solvent, and graphite host. Adv. Energy Mater. 7, 1601519 (2017).

Kim, H. et al. Sodium intercalation chemistry in graphite. Energy Environ. Sci. 8, 2963–2969 (2015).

Jache, B. & Adelhelm, P. Use of graphite as a highly reversible electrode with superior cycle life for sodium-ion batteries by making use of co-intercalation phenomena. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 53, 10169–10173 (2014).

Åvall, G. et al. In situ pore formation in graphite through solvent co-intercalation: a new model for the formation of ternary graphite intercalation compounds bridging batteries and supercapacitors. Adv. Energy Mater. 13, 2301944 (2023).

Divya, M. L., Lee, Y.-S. & Aravindan, V. Solvent co-intercalation: an emerging mechanism in Li-, Na-, and K-ion capacitors. ACS Energy Lett. 6, 4228–4244 (2021).

Wang, J. et al. Mechanistic insight into ultrafast kinetics of sodium cointercalation in few-layer graphitic carbon. Nano Lett. 22, 6359–6365 (2022).

Seidl, L. et al. Intercalation of solvated Na-ions into graphite. Energy Environ. Sci. 10, 1631–1642 (2017).

Kim, H. et al. Sodium storage behavior in natural graphite using ether-based electrolyte systems. Adv. Funct. Mater. 25, 534–541 (2015).

Wei, Q. et al. An ultrahigh-power mesocarbon microbeads|Na+-diglyme|Na3V2(PO4)3 sodium-ion battery. Adv. Mater. 34, 2108304 (2021).

Hasa, I. et al. A sodium-ion battery exploiting layered oxide cathode, graphite anode and glyme-based electrolyte. J. Power Sources 310, 26–31 (2016).

Jache, B., Binder, J. O., Abe, T. & Adelhelm, P. A comparative study on the impact of different glymes and their derivatives as electrolyte solvents for graphite co-intercalation electrodes in lithium-ion and sodium-ion batteries. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 18, 14299–14316 (2016).

Xu, Z.-L. et al. Tailoring sodium intercalation in graphite for high energy and power sodium ion batteries. Nat. Commun. 10, 2598 (2019).

Jiang, L.-L. et al. Inhibiting Solvent co-Intercalation in a graphite anode by a localized high-concentration electrolyte in fast-charging batteries. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 60, 3402–3406 (2020).

Zhou, X. et al. Anion-reinforced solvation for a gradient inorganic-rich interphase enables high-rate and stable sodium batteries. Angew. Chem. 61, e202205045 (2022).

Liang, H.-J. et al. Ether-based electrolyte chemistry towards high-voltage and long-life Na-ion full batteries. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 60, 26837–26846 (2021).

Xia, D. et al. Self-terminating, heterogeneous solid–electrolyte interphase enables reversible Li–ether cointercalation in graphite anodes. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 121, e2313096121 (2024).

Liu, M. et al. Deciphering the paradox between the co-intercalation of sodium-solvent into graphite and its irreversible capacity. Energy Storage Mater. 26, 32–39 (2020).

Song, K. et al. Ultrathin CuF2-rich solid-electrolyte interphase induced by cation-tailored double electrical layer toward durable sodium storage. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 62, e202216450 (2023).

Zhao, Y. et al. Electrolyte engineering for highly inorganic solid electrolyte interphase in high-performance lithium metal batteries. Chem 9, 682–697 (2023).

Ma, T. et al. Optimize lithium deposition at low temperature by weakly solvating power solvent. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 61, e202207927 (2022).

Ko, S. et al. Electrode potential influences the reversibility of lithium-metal anodes. Nat. Energy 7, 1217–1224 (2022).

Wang, S., Zhang, X.-G., Gu, Y., Tang, S. & Fu, Y. An ultrastable low-temperature Na metal battery enabled by synergy between weakly solvating solvents. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 146, 3854–3860 (2024).

Yu, Z. et al. Molecular design for electrolyte solvents enabling energy-dense and long-cycling lithium metal batteries. Nat. Energy 5, 526–533 (2020).

Wang, C. et al. A weakly coordinating-intervention strategy for modulating Na+ solvation sheathes and constructing robust interphase in sodium-metal batteries. Nat. Commun. 15, 6292 (2024).

Yi, Y. et al. Deciphering anion-modulated solvation structure for calcium intercalation into graphite for Ca-ion batteries. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 63, e202317177 (2024).

Cohn, A. P., Share, K., Carter, R., Oakes, L. & Pint, C. L. Ultrafast solvent-assisted sodium ion intercalation into highly crystalline few-layered graphene. Nano Lett. 16, 543–548 (2016).

Wang, H. et al. Stable cycling of Na metal batteries at ultrahigh capacity. Adv. Mater. 36, 2409062 (2024).

Yadegari, H. et al. Operando measurement of layer breathing modes in lithiated graphite. ACS Energy Lett. 6, 1633–1638 (2021).

Tang, Z. et al. Electrode–electrolyte interfacial chemistry modulation for ultra-high rate sodium-ion batteries. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 61, e202200475 (2022).

Guo, D., Wang, J., Lai, T., Henkelman, G. & Manthiram, A. Electrolytes with solvating inner sheath engineering for practical Na–S batteries. Adv. Mater. 35, 2300841 (2023).

Pham, P. N. L. et al. Potassium-ion batteries using KFSI/DME electrolytes: Implications of cation solvation on the K+-graphite (co-)intercalation mechanism. Energy Storage Mater. 45, 291–300 (2022).

Zhang, S. et al. Oscillatory solvation chemistry for a 500 Wh kg−1 Li-metal pouch cell. Nat. Energy 9, 1285–1296 (2024).

Chen, L. et al. Reconstructing helmholtz plane enables robust F-rich interface for long-life and high-safe sodium-ion batteries. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 63, e202407717 (2024).

Son, Y. et al. Diglyme as a promoter for the electrochemical formation of quaternary graphite intercalation compounds containing two different types of solvents. Batteries Supercaps 7, e202300506 (2024).

Tao, L. et al. Solvent-mediated, reversible ternary graphite intercalation compounds for extreme-condition Li-ion batteries. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 146, 16764–16774 (2024).

Xiao, P. et al. Insights into the solvation chemistry in liquid electrolytes for lithium-based rechargeable batteries. Chem. Soc. Rev. 52, 5255–5316 (2023).

Flamme, B. et al. Guidelines to design organic electrolytes for lithium-ion batteries: environmental impact, physicochemical and electrochemical properties. Green. Chem. 19, 1828–1849 (2017).

Chen, Y. et al. Steric effect tuned ion solvation enabling stable cycling of high-voltage lithium metal battery. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 143, 18703–18713 (2021).

Holoubek, J. et al. Tailoring electrolyte solvation for Li metal batteries cycled at ultra-low temperature. Nat. Energy 6, 303–313 (2021).

Zhang, H. et al. Cyclopentylmethyl ether, a non-fluorinated, weakly wolvating and wide temperature solvent for high-performance lithium metal battery. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 62, e202300771 (2023).

Hess, B., Kutzner, C., Spoel, D. V. D. & Lindahl, E. GROMACS 4: algorithms for highly efficient, load-balanced, and scalable molecular simulation. J. Chem. Theory Comput. 4, 435–447 (2008).

Jorgensen, W. L., Maxwell, D. S. & Tirado-Rives, J. Development and testing of the OPLS all-atom force field on conformational energetics and properties of organic liquids. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 118, 11225–11236 (1996).

Zhang, Y. & Maginn, E. J. Direct correlation between ionic liquid transport properties and ion pair lifetimes: a molecular dynamics study. J. Phys. Chem. Lett. 6, 700–705 (2015).

Gingrich, T. R. & Wilson, M. On the Ewald summation of Gaussian charges for the simulation of metallic surfaces. Chem. Phys. Lett. 500, 178–183 (2010).

Cornell, W. D. et al. A second generation force field for the simulation of proteins, nucleic acids, and organic molecules. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 117, 5179–5197 (1995).

Bi, S. et al. Molecular understanding of charge storage and charging dynamics in supercapacitors with MOF electrodes and ionic liquid electrolytes. Nat. Mater. 19, 552–558 (2020).

Padró, J. A., Saiz, L. & Guardia, E. Hydrogen bonding in liquid alcohols: a computer simulation study. J. Mol. Struct. 416, 243–248 (1997).

Guàrdia, E., Martí, J., García-Tarrés, L. & Laria, D. A molecular dynamics simulation study of hydrogen bonding in aqueous ionic solutions. J. Mol. Liq. 117, 63–67 (2005).

Feng, G. et al. Free and bound states of ions in ionic liquids, conductivity, and underscreening paradox. Phys. Rev. X. 9, 021024 (2019).

Acknowledgements

This work is financially supported by the National Key R&D Program of China (2021YFA1202802 [D.Z.]), the National Natural Science Foundation of China (No. 52361165621 [D.Z.], 92472109 [G.F.] and T2325012 [G.F.]), Shenzhen Technical Plan Project (No. JCYJ20220818101003008 [D.Z.] and JCYJ20240813112108012 [D.Z.]).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

J.W. conceived the idea, designed the experiments, performed electrochemical tests, and wrote the manuscript; D.Z. and F.K. directed the project. S.L., M.C., and G.F. performed the MD simulations; J.W. and C.G. conducted the operando XRD; J.W. and W.L. conducted the electrolyte characterizations. All authors contributed to discussing data and revising the paper.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Peer review

Peer review information

Nature Communications thanks Zhicheng Ju, Damien Saurel and the other anonymous reviewer(s) for their contribution to the peer review of this work. A peer review file is available.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Source data

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Wang, J., Li, S., Chen, M. et al. Synergistically competitive coordination for tailoring sodium cointercalation potential of graphite. Nat Commun 16, 7628 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-025-63058-1

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-025-63058-1