Abstract

Ruthenium-bearing intermetallics (Ru-IMCs) featured with well-defined structures and variable compositions offer new opportunities to develop ammonia synthesis catalysts under mild conditions. However, their complex phase nature and the numerous controlling parameters pose major challenges for catalyst design and exploration. Herein, we demonstrate that a combination of machine learning (ML) and model mining techniques can effectively address these challenges. Based on the combination techniques, we generate a two-dimensional activity volcano plot with adsorption energies of N2 and N, and identify the radius of atom coordinating to Ru as a key parameter. The well-designed Sc1/8Nd7/8Ru2 reaches as high as 8.18 mmol m−2 h−1 at 0.1 MPa and 400 °C. Density functional theory (DFT) calculations combined with N2-TPD and FT-IR studies reveal that Ru‒N interaction is controlled by the d-p orbital hybridization between Ru and N. These findings underscore the importance of ML towards material design on exploring IMCs for ammonia synthesis.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Ammonia (NH3) is one of the most important chemical intermediates for chemical and energy industries1,2,3,4,5,6,7. A primary challenge of ammonia synthesis is the breaking of the N ≡ N triple bond, which is one of the strongest bonds among diatomic molecules8,9,10,11,12,13. Therefore, the Cat–N interaction has been the central material design guidelines for ammonia synthesis catalysts14,15,16,17,18,19,20,21,22. Among the reported systems23,24,25,26,27,28,29, Ru-based catalysts have been intensively investigated because of the relatively optimized Ru–N bond strength, facilitating N2 dissociation and NHx formation30,31,32,33,34,35,36,37. One of the successful examples includes the combination with counter elements to create electron-rich Ru and optimized the Ru–N bond strength34,37. In particular, alloying strategy can control its electronic properties, such as d-band center, so as Ru–N bond strength38,39. In addition, Ru sites of alloys and intermetallic compounds are characterized by robust structural and electronic stability, enabling longer catalytic cycles40,41. For example, Hosono et al.34. presented a series of Ru-containing intermetallics (Ru-IMCs), with LaRuSi electride standing out for superior stable performance in NH3 synthesis. These findings have provided a new degree of freedom for catalysts design by allowing lattice Ru to participate in the catalytic cycle. However, the correlation between the electronic states of Ru within IMCs and their catalytic efficacy in ammonia synthesis remains elusive. Most importantly, the vast array of potential Ru-containing IMCs poses a significant challenge for material selection using only chemical intuition or the conventional trial and error method.

Machine learning (ML) techniques, with their robust ability to restructure information and support multidimensional features, are widely used in materials informatics42,43,44. These techniques significantly enhance the capacity to process and summarize large datasets, thereby accelerating catalyst discovery and optimization in various catalytic reactions45,46,47,48,49,50. Recently, ML has been employed to accelerate the discovery of A2BC2 ternary electrides, which exhibit high catalytic activity for ammonia synthesis under mild conditions when loaded with Ru51. Even though the study successfully identified fundamental heuristics for the formation of new electrides, the connection between the materials screening and the catalyst performance within the explored parameter space remains unclear. Additionally, there appear to be very few studies that have employed ML for the development of ammonia synthesis catalysts, particularly those focusing on Ru-IMCs catalysts.

Herein, we developed a ML workflow to screen and predict highly active Ru-IMCs catalysts for ammonia synthesis. Utilizing 201 samples, we constructed a two-dimensional volcano plot, which is scaled by the adsorption energies of N2 and N atoms, EN2 and EN. In it, NdRu2 was found as the potential having optimized parameters, which can be further optimized by Sc-doping. Indeed, the catalytic activity of Sc1/8Nd7/8Ru2 reached as high as 8.18 mmol m−2 h−1 at 0.1 MPa and 400 °C. Density functional theory (DFT) combined with N2-TPD and FT-IR studies revealed that Ru‒N interaction was controlled by the d-p orbital hybridization between Ru and N. Thus, Sc1/8Nd7/8Ru2, which exhibits larger electronic density of state near the Fermi level than Ru and NdRu2 shows higher Ru‒N interaction and N2 dissociation rates. These findings underscore the importance of ML and DFT combined material design on exploring Ru-IMCs for ammonia synthesis.

Results

Machine learning prediction of Ru-IMCs

The workflow for designing efficient Ru-based intermetallic catalysts for ammonia synthesis was outlined in Fig. 1, comprising three main components: materials theoretical prediction, experimental verification, and reaction mechanism analysis. Firstly, a foundational dataset containing 201 Ru-based binary intermetallics was curated from the Inorganic Crystal Structure Database (ICSD) for ML models, which are listed in Supplementary Table 1. Training of the models involved using eXtreme Gradient Boosting (XGB) algorithms for regression predictive modeling. The regression model demonstrating the best performance was then leveraged to predict unexplored materials with promoted activity for ammonia synthesis. The SHapley Additive exPlanations (SHAP) value analysis, an interpretable ML technique, was employed to identify the parameters for optimizing the nitrogen interaction, which was crucial as the adsorption energies of N2 (EN2) and N atoms (EN) were pivotal activity indicators, playing a key role in the N2 activation, and N atoms hydrogenation in the subsequent ammonia formation pathway (Supplementary Fig. 1). To validate the predictions, materials preparations, structural characterization, and catalytic activity evaluations were conducted on the predicted Ru-IMCs materials. Finally, in-situ characterization and DFT calculations were employed to uncover insights into the reaction mechanism enhancing catalytic activities in ammonia synthesis.

The workflow includes stablishing a foundational dataset of Ru-based IMCs; utilizing machine learning to create an activity volcano plot dependent on EN and EN2 for material screening; preparing Ru-IMCs and testing their ammonia synthesis performance; conducting DFT calculations and in-situ characterization to investigate the underlying mechanisms.

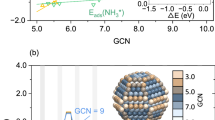

For ML of Ru-based binary intermetallics, each case was described using multidimensional vectors that considered both element-specific and chemical environment features of Ru active sites. Here, the composition of the IMCs is characterized by the normalized stoichiometric ratio of the elements present in the material (denoted as NSR). The chemical environment of the active sites is defined by the Miller indices (denoted as (h k l)), the total number of atoms in the sites (denoted as site atoms), and the Ru ratio of the sites (denoted as Ru ratio). Furthermore, the coordination specificity of the elements is determined by the variance in the first ionization energy in comparison to Ru (denoted as Δ(X-Ru)) and the radius of the coordinating elements (denoted as r(X)). Here, the selected features possessed high irrelevance in heat map depicted Fig. 2a, indicating they independently represent an aspect of the atomic and electronic structure of the chemical system while being correlated and independent. To augment the prediction accuracy of ML, we evaluated the performance of multiple regression algorithms, including XGB, Multi-Layer Perception (MLP), K Nearest Neighbors (KNN), Gradient Boosting Decision Tree (GBDT), and Support Vector Regression (SVR) models (Fig. 2b). The obtained adsorption energy data of EN2 and EN was randomly shuffled and divided, with 80% for the training model and the remaining 20% for test model (Fig. 2c). The difference between the predicted and calculated values was defined as the error to assess the models’ performance. As depicted in the violin plot (Fig. 2b), the XGB model displayed the most competitive prediction accuracy for error values and probability density for the adsorption energy of both N2 and N atoms among the five models, with details of the predictions of different models displayed in Supplementary Figs. 2–5. Additional evaluation metrics for model accuracy were summarized in Supplementary Tables 2 and 3. Across all metrics, including MAE (Mean Absolute Error), RMSE (Root Mean Square Error), and R² (R-square), the XGB model consistently demonstrated the best performance and can be utilized for the ML algorithms.

a Heat map of Pearson’s correlation coefficient matrix in features which were employed in machine learning models. b Violin plots of the error from true to predicting N2 and N adsorption energies through XGB, MLP, KNN, GBDT, and SVR models. c The regression curve of training data and testing data by XGB model. d A two-dimensional activity volcano plot for ammonia synthesis. N2 and N adsorption energies in panels were calculated using DFT. The gray square points are selected Ru-IMCs to train the model; blue cycle points are predicted Ru-IMCs through the model; and asterisk represents the un-explored Ru-IMCs candidate for ammonia synthesis. e The beeswarm plot of feature importance in XGB models using SHAP assessment. f The average absolute SHAP values of each input feature.

Next, a volcano plot was generated using the XGB model algorithm to evaluate the catalytic activity of various Ru-IMCs catalysts (Fig. 2d). All predicted EN/EN2 values for the Ru-IMC catalysts are listed in Supplementary Table 1 and Supplementary Fig. 6. Considering the elementary steps of ammonia synthesis, the energy barriers of each step can be depicted by the adsorption energies of N2 and N atoms. Subsequently, we calculated their adsorption energies on different surfaces of Ru-IMCs through high-throughput methods, represented by the gray square points in Fig. 2d. To validate the accuracy of these data points, a selection of them was prepared, and their catalytic activities for ammonia synthesis were measured under conditions of 0.1 MPa and 400 °C. The reaction rates were determined for YRu2, LaRu2, and Ga3Ru, showing the order of Ga3Ru (N. D.) <LaRu2 (0.25 mmol g−1 h−1) < YRu2 (0.57 mmol g−1 h−1) (Supplementary Fig. 7), aligning well with the trend observed in the volcano plot (Fig. 2d). Additionally, in Fig. 2d, the positions corresponding to Ru-IMCs represented by the blue circles were identified through ML screening, with NdRu2 emerging as a promising candidate for ammonia synthesis due to its proximity to the apex of the volcano plot. Next, we obtained NdRu2 pure phase through arc-melting and further tested its catalytic performance (Supplementary Fig. 8). The ammonia production rate of NdRu2 is as high as 0.86 mmol g−1 h−1, surpassing that of YRu2, LaRu2, and Ga3Ru, which is in line with the predicted trend of the volcano plot, but it still does not quite reach the peak of the volcano plot (Fig. 2d). Referring to Fig. 2d, focusing on NdRu2, enhancing N2 adsorption without altering the interaction of N atoms too much could bring us closer to the volcano plot’s apex. Typically, element doping serves as an effective method to tailor the properties of the host material, potentially modifying the surface adsorption strength of the reactant molecules. Nevertheless, in the absence of clear guidance, the options for doping can become overwhelming and arbitrary.

In order to uncover the underlying chemical patterns within the model and facilitate optimization, we utilized the SHAP value method to delve into the complex relationship between features and adsorption energies. A negative SHAP value for a feature indicates an enhancement on EN or EN2 through the XGB model’s output. As illustrated in Fig. 2e, instances of robust N atom adsorption tendencies were typically linked to high feature values of NSR and atoms, but low feature values of r(X) and Ru ratio. Conversely, cases involving N2 adsorption usually demonstrated elevated feature values of Δ(X-Ru) and Ru ratio, alongside lower feature values of r(X). By combining the feature importance values outlined in Fig. 2f and Supplementary Table 4, replacing an element with a lower r(X) at the Nd site could enhance N2 adsorption while minimally impacting the strength of N atoms, thereby potentially enhancing the catalytic performance of NdRu2.

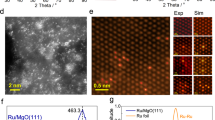

Preparation and characterization of Ru-IMCs

By using the arc-melting method, we successfully synthesized the Laves phase NdRu2. In this structure, Ru atoms occupy sites with a coordination number (CN) of 12, forming a Frank-Kasper polyhedron. The Nd atoms, on the other hand, have a CN of 16. This well-defined crystal structure and the combination of elements spanning the periodic table provide a unique opportunity to tune the properties of Ru by modifying the Nd site. Since Nd is a rare earth element, we use a light rare earth element, Sc as the doping element and designed a novel Sc-doped NdRu2 intermetallic catalyst. Here we have optimized the molar ratio of Sc doping to be 12.5% (Supplementary Fig. 9), that can be denoted as Sc1/8Nd7/8Ru2. Given a smaller radius of Sc (160 pm) compared to Nd (185 pm), the substitution of Nd atoms with Sc is expected to induce lattice contraction of NdRu2. As shown in Fig. 3b, Rietveld refinement was conducted to precisely verify the expected lattice change observed in the X-ray diffraction (XRD) patterns. Upon doping with Sc, the lattice parameters of Sc1/8Nd7/8Ru2 are smaller than those of NdRu2 (contracting from 7.613 Å to 7.573 Å), consistent with the structural relaxation predicted by our DFT calculations (Fig. 3a). The Extended X-ray Absorption Fine Structure (EXAFS) of Ru K-edge as depicted in Fig. 3c reveals a slight shift of the first nearest-coordination peaks in R space of NdRu2 and Sc1/8Nd7/8Ru2. The curve fitting results of all three samples are listed in Supplementary Figs. 10 and 11 and Supplementary Tables 5 and 6, which demonstrates that the specific Ru−Nd bond length decreases from 2.55 Å (NdRu2) to 2.48 Å (Sc1/8Nd7/8Ru2), further confirming the lattice contraction induced by Sc incorporation.

a Crystal structure and lattice parameters of NdRu2 (left) and Sc1/8Nd7/8Ru2 (right) through DFT calculations. b Rietveld refinement of NdRu2 and Sc1/8Nd7/8Ru2. c EXAFS of Ru K-edge based on Fourier transform for NdRu2 and Sc1/8Nd7/8Ru2. d XANES of Ru K-edge for NdRu2 and Sc1/8Nd7/8Ru2. Ru 3d XPS of e NdRu2, and f Sc1/8Nd7/8Ru2. g TEM and EDS mapping of Sc1/8Nd7/8Ru2, inset shows the corresponding Fourier transform pattern. h The interplanar spacings of different crystal faces in NdRu2 and Sc1/8Nd7/8Ru2.

The electronic structure of NdRu2 and Sc1/8Nd7/8Ru2 was analyzed using X-ray absorption near-edge structure (XANES) and X-ray photoelectron spectroscopy (XPS). Illustrated in Fig. 3d, the absorption pre-edge positions follow the sequence of Ru foil > Sc1/8Nd7/8Ru2 > NdRu2, indicating the negatively charged nature of the Ru species in both NdRu2 and Sc1/8Nd7/8Ru2, with the electron density of Ru being slightly lower in Sc1/8Nd7/8Ru2 than that in NdRu2. Figure 3e, f depict the XPS Ru 3d spectra with respect to the binding energy of Sc1/8Nd7/8Ru2 and NdRu2. The noticeable shifts of typical peaks to lower energy also indicate negatively charged feature of surface Ru sites, which is consistent with the XANES results. While the Nd 3 d peaks exhibit a significant shift to higher energy compared to Nd0 3d (Supplementary Fig. 12). These findings suggest that Nd and Sc donate electrons while Ru accepts electrons in NdRu2 and Sc1/8Nd7/8Ru2 systems. The enrichment of electrons on the surface Ru highlights the potential for promoting the back-donation of electrons to the antibonding π-orbitals of adsorbed N2.

Transmission electron microscopy (TEM) was employed to investigate the microstructure of NdRu2 and Sc1/8Nd7/8Ru2. The elemental distribution in Sc1/8Nd7/8Ru2 was assessed using Energy Dispersive Spectroscopy (EDS) mapping, depicted in the middle of Fig. 3g, revealing the uniform dispersion of Nd, Sc, and Ru elements in Sc1/8Nd7/8Ru2 particle. On the right side of Fig. 3g, a distinct lattice corresponding to the (3 1 1) index was evident, consistent with the Fourier transform pattern in the inset. Additional crystal plane orientations can be observed in Supplementary Fig. 13. The interplanar spacings of NdRu2 and Sc1/8Nd7/8Ru2 measured by TEM are summarized in Fig. 3h. It is apparent that following Sc doping, all interplanar spacings demonstrate a contraction of 4.3–7.4%, aligning with theoretical calculations (Fig. 3a), XRD patterns (Fig. 3b), and EXAFS results (Fig. 3c).

Ammonia synthesis performance of Ru-IMCs

We successfully doped NdRu2 by Sc with a smaller ion radius to create a new Ru-IMCs, Sc1/8Nd7/8Ru2, and sought to evaluate its performance in catalytic ammonia synthesis. In Fig. 4a, the catalytic activity is depicted as a function of temperature over Sc1/8Nd7/8Ru2, NdRu2, and Ru metal. The ammonia production rate of Sc1/8Nd7/8Ru2 reached 2.77 mmol g−1 h−1, which is 3 times higher than that of NdRu2 (0.86 mmol g−1 h−1) at 400 °C and 0.1 MPa, while pure Ru metal exhibited negligible activity. Note that the catalytic activity of Sc1/8Nd7/8Ru2 surpasses that of other intermetallic catalysts investigated under similar reaction conditions, such as LaRuSi (1.76 mmol g−1 h−1), LaCoSi (1.25 mmol g−1 h−1), and YRu2 (0.57 mmol g−1 h−1) (Fig. 4b). The activities of Ru/MgO and Ru/AC catalysts are also referenced as typical Ru-based catalysts; they exhibited lower activities for ammonia production, at 0.80 mmol g−1 h−1 and 0.77 mmol g−1 h−1 (Supplementary Fig. 14), respectively, significantly less than that of the Sc1/8Nd7/8Ru2 catalyst. Despite having a relatively low surface area of only 0.34 m2 g−1, Sc1/8Nd7/8Ru2 yields a remarkable reaction rate of 8.18 mmol m−2 h−1 when assessed by specific activity, positioning it as one of the most active binary Ru-based intermetallic catalysts (Fig. 4b and Supplementary Tables 7 and 8).

a Temperature dependence of the NH3 synthesis rates over Ru, NdRu2, and Sc1/8Nd7/8Ru2 under 0.1 MPa. b Catalytic activity (dark blue, specific surface activity; light blue, mass activity) for ammonia synthesis over various Ru-IMCs catalysts. Error bars represent the standard deviation from three independent measurements. c Arrhenius plots for NH3 synthesis over NdRu2 and Sc1/8Nd7/8Ru2 under 0.1 MPa. d Reaction orders of H2 and N2 and e pressure effect of NdRu2 and Sc1/8Nd7/8Ru2. f Time courses for NH3 synthesis over Sc1/8Nd7/8Ru2 at 0.1 and 0.9 MPa, 400 °C.

In the earlier section on ML, we noted that the small radius of the coordinating atom in Ru-IMCs would notably improve their N2 adsorption, thereby enhancing the activity of ammonia synthesis. Here, if we introduce the element Y with a slightly larger atomic radius (180 pm) than Sc and incorporate it into NdRu2 at the same ratio, the resulting Y1/8Nd7/8Ru2 catalyst displays a catalytic activity of 0.94 mmol g−1 h−1 for ammonia production (Supplementary Fig. 15). This places it between Sc1/8Nd7/8Ru2 (2.77 mmol g−1 h−1) and NdRu2 (0.86 mmol g−1 h−1), underscoring the significant impact of the doping atomic radius on enhancing the activity of NdRu2. The outstanding catalytic performance observed with small atomic radius element doping in NdRu2 for ammonia synthesis aligns with the trend depicted in the volcano plot in Fig. 2d, which emphasizes our methodology of utilizing the XGB algorithm for screening and optimizing Ru-IMCs catalysts for ammonia synthesis through ML as a reliable and effective approach.

The kinetics of ammonia synthesis over NdRu2 and Sc1/8Nd7/8Ru2 catalysts were analyzed using the ammonia production rates (r) at different reaction temperatures. A series of Arrhenius plots were generated by plotting lnr against 1/T. The slope of the Arrhenius plot allowed for the calculation of the apparent activation energy (Ea) for Sc1/8Nd7/8Ru2, resulting in a value of 38.7 kJ·mol−1 (Fig. 4c). This represents a reduction of approximately 30% compared to the Ea for the undoped NdRu2 catalysts (58.9 kJ·mol−1), providing evidence that Sc doping significantly enhances the ammonia synthesis reaction over NdRu2. The suppressed Ea is attributed to Sc doping, which improves the adsorption of N2, thereby reducing the energy barrier for N2 dissociation on Sc1/8Nd7/8Ru2. This hypothesis is initially supported by the N2 reaction orders, with the N2 reaction order for undoped NdRu2 being close to unity (α = 0.94). While, the N2 reaction order was measured to be 0.77 over Sc1/8Nd7/8Ru2 (Fig. 4d), indicating higher efficiency of N2 dissociation on Sc doped NdRu2. Compared to NdRu2, Sc1/8Nd7/8Ru2 not only exhibits a lower activation energy but also demonstrates a fundamental improvement in resistance to hydrogen poisoning. Figure 4d illustrates the H2 reaction orders, with the undoped NdRu2 catalyst showing a negative value of −0.22, which demonstrates a strong hydrogen adsorption on its surface, named hydrogen poisoning effect. Conversely, the H2 reaction order of Sc1/8Nd7/8Ru2 is positive, reaching 0.79 (Fig. 4d), indicating that hydrogen poisoning has been mitigated by Sc doping. This substantial difference results in markedly different catalytic performance under high-pressure conditions, where the reaction rate over Sc1/8Nd7/8Ru2 shows an approximately linear response to pressure increase. This led to a fourfold increase to 9.03 mmol g−1 h−1 when the reaction pressure rose from 0.1 to 0.9 MPa (Fig. 4e). Such enhancement of catalytic activity with pressure is not observed for NdRu2, as the catalytic performance remains independent of total pressure, probably attributed to the hydrogen poisoning effect over NdRu2. We further investigated the high-pressure responsiveness of Sc1/8Nd7/8Ru2. As shown in Supplementary Fig. 16, the reaction rate increased monotonically to 15.85 mmol g−1 h−1 at 2.0 MPa, indicating a positive pressure effect for Sc1/8Nd7/8Ru2 in ammonia synthesis. The exceptional stability of Sc1/8Nd7/8Ru2 is evidenced by its sustained activity over 105 h at 400 °C under pressures of 0.1 MPa and 0.9 MPa, respectively (Fig. 4f). XRD patterns show the lattice parameters of the used Sc1/8Nd7/8Ru2 sample are slightly larger than those of the fresh sample (increasing from 7.573 to 7.584 Å, Supplementary Figs. 17 and 18), likely due to the incorporation of hydrogen, which will be discussed below. Repeatable ammonia synthesis activity was observed for different batches of Sc1/8Nd7/8Ru2 over an 80-h period (Supplementary Fig. 19).

Mechanism studies of Ru-IMCs for ammonia synthesis

To explore the origin of high performance of Sc1/8Nd7/8Ru2, we conducted computational studies using first-principles calculations. Bader charge analysis indicates that the valence states of Ru in NdRu2 and Sc1/8Nd7/8Ru2 are −0.66 and −0.61, respectively, signifying electron transfer from Nd and/or Sc to Ru in the lattice of these intermetallic compounds (Supplementary Table 9), consistent with the experimental results in XANES and XPS (Fig. 3d–f). It is important to note that the electronic structure analysis from the XANES and XPS results demonstrates that the electron density of Ru in Sc1/8Nd7/8Ru2 is lower than that in NdRu2 (Fig. 3d–f), yet N2 activation is significantly enhanced over Sc1/8Nd7/8Ru2 (Fig. 4d). This observation contradicts the well-known assumption that increasing the electron density of Ru active sites would enhance electron back donation for N2 dissociation and subsequently ammonia production.

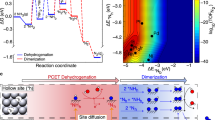

Motivated by the aforementioned discrepancy, we conducted DFT calculations to elucidate the electronic structure of these catalysts. Figures 5a–c displays the band structures of the Ru element in Ru, NdRu2, and Sc1/8Nd7/8Ru2, in which the electron states near the Fermi level of both NdRu2 and Sc1/8Nd7/8Ru2 are significantly higher than that of pure Ru. To discern the enhanced N2 activation over NdRu2 and Sc1/8Nd7/8Ru2, we calculated the projected density of states (pDOS), and the 3σ and 2π orbitals of free N2 contribute to the energy range of −4 to 0 eV, aligning well with the energy level of Ru d orbitals (Fig. 5d), and their overlap is most prominent over Sc1/8Nd7/8Ru2 (Fig. 5e), indicating a strong tendency for Sc1/8Nd7/8Ru2 to interact with N2. Additionally, the pDOS results of adsorbed N2 reveal that the p-band of N splits into a bonding state and a small antibonding state (below and above the Fermi level, respectively), with the bonding orbitals of N2 hybridizing with Ru d orbitals at around −8 to −5 eV (Supplementary Fig. 20). Notably, the electronic state at the bonding orbitals of N2-adsorbed Sc1/8Nd7/8Ru2 exhibits a more negatively shifted energy compared with NdRu2 and Ru, indicating a more stabilized N2. The significant N2 adsorption results in the weakening of the N ≡ N triple bond and a more pronounced elongation of the bond length over Sc1/8Nd7/8Ru2 (Fig. 5e), which is consistent with the prediction made by the SHAP value method in ML, suggesting that doping small-radius elements in Ru-IMCs would enhance N2 adsorption.

Calculated band structure of a Ru and Ru element in b NdRu2, c Sc1/8Nd7/8Ru2. d Projected density of states (PDOS) of free N2 and Ru d-band in Ru metal, NdRu2 and Sc1/8Nd7/8Ru2. The inserts show surface structure and electron distribution (yellow, electron rich; sky blue, electron poor) of a N2-adsorbed catalysts. e A comparison of the overlap of the local electron state ranging from −4 to 0 eV between N2 and Ru-IMCs. f Reaction free energy for N2 dissociation and g N2-TPD of Ru, NdRu2 and Sc1/8Nd7/8Ru2. h FT-IR spectra of N2-adsorbed NdRu2 (14N2) and Sc1/8Nd7/8Ru2 (14N2 and 15N2). i H2-TPD of NdRu2 and Sc1/8Nd7/8Ru2. Insert shows the crystal structure of hydrogen incorporated Sc1/8Nd7/8Ru2.

The work function of Sc1/8Nd7/8Ru2 on the crystal facet (001), the most stable surface, was calculated to be 2.95 eV (Supplementary Fig. 21), indicating its high electron donation ability. With the high electronic states near the Fermi level, Sc1/8Nd7/8Ru2 is poised to facilitate electron injection into the adsorbed N2. Hence, the 3D electron density isosurface map illustrates a pronounced electron transfer from Sc1/8Nd7/8Ru2 to the adsorbed N2 (Fig. 5d inset, Supplementary Figs. 22–24). The activated N2 reaction pathway was further examined on the surfaces of Ru, NdRu2, and Sc1/8Nd7/8Ru2. NdRu2 demonstrates stronger N2 adsorption compared to Ru, with adsorption energies of −0.94 eV versus −0.62 eV (Fig. 5f). The addition of Sc enhances N2 adsorption further, increasing it from −0.94 eV to −1.17 eV. This finding is in line with both the previously discussed reaction kinetics findings (Fig. 4d) and theoretical calculation results (Fig. 2d). The N2 dissociation barrier over Ru, NdRu2, and Sc1/8Nd7/8Ru2 was determined to be 1.79 eV (for Ru flat site), 1.32 eV (for Ru B5 site see in Supplementary Fig. 25),1.15 eV, and 0.75 eV, respectively, which indicates that the adsorbed N2 is more readily cleaved over Sc1/8Nd7/8Ru2.

Experimental studies were conducted using the calculation data provided to assess the validity of the proposed N2 activation mechanism. As depicted in Fig. 5g, N2 desorption from Sc1/8Nd7/8Ru2 occurs at 501 °C, a higher temperature range than that from NdRu2 (379 °C), while there is almost no desorption from pure Ru, which suggests that the nitrogen interaction strength over Sc1/8Nd7/8Ru2 is significantly stronger, consistent with the calculated adsorption energies shown in Fig. 5f. Quantification revealed 0.005 mmol of desorbed nitrogen, a value similar to the number of exposed Ru atoms (0.004 mmol) on the surface of Sc1/8Nd7/8Ru2 catalyst (Supplementary Table 10). This, along with the XPS observation of a strong N 1s peak (~398.4 eV) on the used catalyst that almost disappeared after Ar plasma etching (Supplementary Fig. 26), supports the conclusion that the desorbed nitrogen originates primarily from surface species rather than from the bulk material of Sc1/8Nd7/8Ru2. FT-IR results reveal broad peaks around 2300–2100 cm−1, attributed to the stretching vibrational mode of chemisorbed N2 on Ru sites (Fig. 5h). Due to N ≡ N stretching (νN2), the 14N2-adsorbed NdRu2 exhibits a broad band at 2222.6 cm−1. While, 14N2-adsorbed Sc1/8Nd7/8Ru2 shows a broad band assignable to νN2 at around 2191.9 cm−1 (Fig. 5h). The red-shift of the N2 signal is clear evidence of a stronger electronic interaction between N2 and Sc1/8Nd7/8Ru2, in which N2 accepts more electrons and is more dissociative than that on NdRu2. For 15N2 adsorbed on Sc1/8Nd7/8Ru2, the adsorption band appears around 2118.4 cm−1 (Fig. 5h), consistent with the value estimated based on the isotope effect (2191.9 cm−1 × \(\sqrt{14/15}\) = 2117.6 cm−1), indicating the chemisorbed N2.

To determine the origin of the resistance to hydrogen poisoning over Sc1/8Nd7/8Ru2, we conducted an H2-TPD experiment to examine the thermal desorption of the used samples. As depicted in Fig. 5i, the mass signal of H2 is scarcely detected on NdRu2, whereas a prominent peak is observed at 171 °C on Sc1/8Nd7/8Ru2, indicating that the ability to incorporate hydrogen has been achieved through the substitution of Sc. The mole ratio of the hydrogen can be estimated to be 0.52 through mass quantification, denoted as Sc1/8Nd7/8Ru2H0.52. DFT calculation results also reveal that the hydrogen-involving Sc1/8Nd7/8Ru2 structure is much more energetically favored than that of NdRu2, further confirming that H− can be trapped in Sc1/8Nd7/8Ru2, which accounts for the high resistance to hydrogen poisoning issue.

Discussion

In summary, we developed a ML workflow to predict highly active Ru-based intermetallic catalysts (Ru-IMCs) for NH3 synthesis. A two-dimensional activity volcano plot was constructed by employing the adsorption energies of N2 and N atoms as descriptors. Among the candidates evaluated, a novel Sc1/8Nd7/8Ru2 intermetallic catalyst achieved the highest activity ever reported for Ru-IMCs catalysts. Combining the experimental characterizations and theoretical studies, we found that Sc doping significantly enhances N2 activation by augmenting the local electron state near the Fermi level of IMCs. Furthermore, Sc doping provides extra interstitial spaces in the lattice, granting Sc1/8Nd7/8Ru2 with an unexpected ability to resist hydrogen poisoning, leading to excellent catalytic stability and improved high-pressure performance.

Methods

Data processing for machine learning

All binary Ru-based intermetallics were collected from ICSD. The identification of adsorption sites on low Miller index surfaces of intermetallics were recognized by pymatgen package. 20% cases of the dataset were calculated the adsorption energy of nitrogen molecule and nitrogen atom through DFT for the model training and testing. The adsorption energy of other 80% were predicted through the selected model. Each case would be represented as a 6-dimension feature vector, and all dimensions were normalized to diminish the influence of different feature scales.

Machine learning model training

SVM, KNN, MLP, GBDT, and XGB algorithms were obtained through Scikit-Learn package. KNN is a simple, non-parametric, and instance-based learning algorithm used for both classification and regression tasks. The most common distance metric used in KNN is Euclidean distance. For two points x = (x1, x2, x3, …, xn) and y = (y1, y2, y3, …, yn), the Euclidean d is given by:

For regression, if yi represents the value of the i-th nearest neighbor, the predicted value ŷ is typically the mean of the neighbors’ values:

The goal of SVM is to find a separating hyperplane that maximizes the margin between two classes of data points. Suppose we have a training dataset (xi, yi), where xi is a feature vector and yi is the class label. A hyperplane can be represented as:

where w is the normal vector to the hyperplane and b is the offset.

GBDT is an ensemble learning method that builds multiple decision trees to enhance the predictive power of the model. Each tree is trained to correct the errors made by the previous trees. The output of a GBDT model is a weighted sum of the outputs of multiple tree models:

where hm(x)is the output of the m-th tree, and γm is the corresponding weight.

XGBoost is an efficient implementation of GBDT, offering better performance and faster computation, making it suitable for large-scale data. The objective function of XGBoost includes both the loss function and a regularization term:

where T is the number of leaves in the tree, and wj is the weight of the j-th leaf.

MLP is a type of feedforward neural network composed of an input layer, one or more hidden layers, and an output layer. For each layer l, the output is computed as:

where al is the activation value of this layer, Wl is the weight matrix, bl is the bias vector, and f is the activation function. Common loss functions include Mean Squared Error for regression.

SHAP analysis

Shapley value method was computed by a model-independent kernel as implemented in the SHAP package to explain the governing electronic factors. The SHAP value is defined as follows:

where S is a subset of features not containing i, |S| is the size of subset S, v(S) is the contribution of subset S to the model output.

For any input x, the model output f(x) can be expressed as the sum of all feature Shapley values plus a baseline value:

where Φ0 is the baseline value (often the mean prediction over all samples), and Φi is the Shapley value for feature i.

DFT calculations

All of the structure relaxation and electronic structure calculations were performed using the DFT as implemented in the Vienna Ab initio Simulation Package52. The generalized gradient approximation was adopted in the DFT calculations and the core electrons were described using the projector augmented wave method53,54,55. The GGA + U method56 was used since the local interactions of the f electrons in Nd, with the Coulomb parameter U = 4.8 eV and Hund’s exchange J = 0.6 eV57. The description of valence electrons was using plane wave basis kinetic energy cut-off value with 450 eV. All models were fully optimized until the energy and forces were converged to 1 × 10−5 eV and 0.0257 eV Å−1, respectively. For cubic relaxion, Nd8Ru16 and Sc1Nd7Ru16 used a Gamma center mesh of 4 × 4 × 4.

For N2 dissociation calculations, the slab models were built based on (001) facet. The thickness of the vacuum layer is 25 Å with the K-mesh of 2 × 2 × 1. The bottom layers were constrained to their original positions. The dissociation of N2 was considered as following steps:

where * represents the Ru sites, *N2 and *N means nitrogen molecule and nitrogen atoms adsorbed at sites.

The reaction energy of each step was considered as follows:

where Ep is the energy of each part of production, Er is the energy of each part of reactant.

For TS calculation, the parameters of CI-NEB58 were kept the same as the structure relaxation. Five transition states were interpolated linearly between initial state and final state by VASPKIT package59.

Sample preparation

NdRu2 intermetallic was synthesized by arc-melting neodymium (99.9%, Adamas) and ruthenium (99.95%, Adamas) ingots with a molar ratio of 1:2. The resulting silver-gray ingot was annealed in an enclosed quartz tube for a duration of ten days at 1000 °C, followed by water cooling to room temperature. Subsequently, the prepared NdRu2 was ground into powder within a glovebox. No additional treatment was performed before utilizing as a catalyst for ammonia synthesis test. Similarly, the intermetallics Sc1/8Nd7/8Ru2 and Y1/8Nd7/8Ru2 were synthesized like NdRu2 with 1/8 Sc (99.9%, Adamas) or Y (99.9%, Adamas) replace Nd. YRu2 was prepared from arc-melting with a stoichiometric mixture of Ru (99.95%, Adamas) and Y (99.9%, Adamas) without further treatment. Ga3Ru was obtained based on previous report60. Typically, the Ga (99.99%, Adamas) and Ru (99.95%, Adamas) with a molar ratio of 10:1 were mixed, and loaded into quartz ampoules, then sealed under vacuum. The mixture was heated to 800 °C with 3 °C min−1, kept at 800 °C for 24 h, and finally cooled to room temperature. Excess Ga metal was dissolved with 3 M HCl and washed with deionized water. Ru/MgO and Ru/AC were prepared using commercial MgO (99.9995%, Adamas) and active carbon (99.9995%, Adamas) as supports. MgO or AC and Ru3(CO)12 (99.99%, Adamas) were mixed and then sealed in an evacuated silica tube and heated under a temperature programme of 0.5 °C min−1 from room temperature to 250 °C, kept at 250 °C for 2 h and then cooled to room temperature. All the materials were commercially available without further purification.

Catalytic reaction

The catalytic reactions were conducted in a fixed-bed flow system with a mix gas flow of H2:N2 (3:1) at a flow rate of 60 ml min−1. In a typical test, 100 mg catalyst was loaded into the reactor in the glovebox and then pre-treated in a stream of above mix gas flow under 0.1 MPa using a temperature program of heating to 400 °C for 2 h and then holding at 400 °C for 2 h. The reaction was monitored under steady-state conditions of temperature (250–400 °C) with a flow rate of 60 ml min−1 under 0.1–0.9 MPa. The produced ammonia was trapped in 5 mmol sulfuric acid solution and the amount of NH4+ generated in the solution was determined using an ion chromatograph (Prominence, Shimadzu) equipped with a conductivity detector. Comparison of the catalyst performance was conducted under the same conditions.

Kinetic studies

The experimental active energy (Ea) was calculated based on Arrhenius plots like follows.

where k is the ammonia synthesis rates, which were less than 20% of that at equilibrium.

Measurement of the reaction orders for N2 and H2 was conducted with Ar gas as a diluent to ensure a total flow of 60 mL min−1 when changing the flow rate of N2 and H2. The reaction orders were estimated by using the followings:

where r, W, y0, q, and (1-m) represent the reaction rate of the ammonia synthesis, the catalyst weight, the mole fraction of NH3 at the reactor outlet, the flow rate, and the reaction order with respect to NH3 (γ). Finally, the α and β can be determined by plotting the logarithm of r vs that of N2 or H2 partial pressure.

Characterization

The specific surface area was analyzed using Nitrogen sorption measurements (ASAP2460, Micromeritics) through Brunauer–Emmett–Teller method. The crystal structure of materials was analyzed using XRD (Equinox 3500, Thermo Fisher) with Cu Kα radiation (λ = 0.15418 nm). To prevent oxidation, the samples were enclosed in Ar-filled plastic capsules. The surface morphologies of the catalyst samples were investigated using 200 kV field emission transmission electron microscopy (Talos F200X G2, Thermo Scientific). X-ray photoelectron spectroscopy (ESXCALAB Xi + ; Thermo Scientific) measurements were performed using magnesium Kα radiation at <10−6 Pa (8 kV bias voltage applied to the X-ray source). X-ray photoelectron spectroscopy data were corrected according to the C (carbon) 1 s peak (binding energy = 284.8 eV). The strength of the interaction between the catalyst and N2 or H2 is studied using the BELCAT II (Microtrac BEL) equipment. Typically, a 0.2 g sample is placed in a quartz tube, and the pretreatment involves heating from room temperature to 300 °C in an Ar flow, holding at 300 °C for 2 h. Then the flow is switched to N2 or H2, cooling naturally to room temperature, and keeping for an additional 2 h. Subsequently, under an Ar flow, the temperature is increased to the specified value at a rate of 10 °C min−1, and the signal is detected using an online mass spectrometer (ANELVA, Quadrupole Mass Spectrometer) with masses m/z = 2 or 28. FT-IR were measured using a spectrometer (IRTracer-100, Shimadzu) equipped with a mercury–cadmium–tellurium detector at a resolution of 4 cm−1. Samples were pressed into self-supported disks (20 mm diameter). A disk was placed in a silica-glass cell equipped and connected to a closed gas-circulation system to allow thermal adsorption–desorption experiments. The disk was heated under an Ar flow at 300 °C for 2 h. After the pretreatment, the disk was cooled to –170 °C under vacuum by liquid-nitrogen to obtain a background spectrum. Pure N2 (99.99995%) or isotopic nitrogen (15N2, 98% without further purification) were pumped to the catalyst system. The infrared spectrum of the sample at –170 °C prior to N2 adsorption was used as the background for difference spectra obtained by subtracting the background from the spectra of N2-adsorbed samples. For diatomic molecules N2, the infrared vibration frequency (ν) can be expressed through the harmonic vibration models as:

where k is a constant related to the chemical bond, μ represents the reduced mass of N2,

where m1, m2 represent the atomic mass in N2 molecules. Based on Eqs. (17) and (18), the infrared vibration frequency ratio of 14N2 and 15N2 can be described as follows:

The X-ray absorption data at the Ru K-edge of the samples were recorded at room temperature in transmission mode using ion chambers at beam line BL14W1 of the Shanghai Synchrotron Radiation Facility (SSRF), China. The station was operated with a Si (111) double crystal monochromator. During the measurement, the storage ring was operated at energy of 3.5 GeV and a current of 200 mA (top-up). The photon energy was calibrated with the first inflection point in Ru K-edge of Ru metal foil. X-ray absorption fine-structure spectra and X-ray absorption near edge structure were studied using the Athena and Artemis software packages61.

Data availability

The data generated in this study are presented in the main text and Supplementary Information, and can be obtained from the corresponding authors upon request.

References

Cao, Y. et al. Zr-based Laves phases with nitride/hydride ions for ammonia synthesis. Solid State Sci. 145, 107331 (2023).

Erisman, J. W. et al. How a century of ammonia synthesis changed the world. Nat. Geosci. 1, 636–639 (2008).

Fu, X. et al. Continuous-flow electrosynthesis of ammonia by nitrogen reduction and hydrogen oxidation. Science 379, 707–712 (2023).

Fu, X. et al. Calcium-mediated nitrogen reduction for electrochemical ammonia synthesis. Nat. Mater. 23, 101–107 (2024).

Li, S. et al. Long-term continuous ammonia electrosynthesis. Nature 629, 92–97 (2024).

Smil, V. Detonator of the population explosion. Nature 400, 415 (1999).

Zhang, Y. et al. Fullerene on non-iron cluster-matrix co-catalysts promotes collaborative H2 and N2 activation for ammonia synthesis. Nat. Chem. 16, 1781–1787 (2024).

Gambarotta, S. & Scott, J. Multimetallic cooperative activation of N2. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 43, 5298–5308 (2004).

Jiang, Y. et al. CN22– vacancies enhance ammonia synthesis over air-durable alkaline earth metal cyanamide-supported cobalt catalysts. ACS Catal. 14, 6349–6357 (2024).

Wu, L. J. et al. From dinitrogen to N-containing organic compounds: using Li2CN2 as a synthon. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 62, e202219298 (2023).

Ye, T. N. et al. Vacancy-enabled N2 activation for ammonia synthesis on an Ni-loaded catalyst. Nature 583, 391–395 (2020).

Ye, T. N. et al. Dissociative and associative concerted mechanism for ammonia synthesis over Co-based catalyst. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 143, 12857–12866 (2021).

Jia, H. P. & Quadrelli, E. A. Mechanistic aspects of dinitrogen cleavage and hydrogenation to produce ammonia in catalysis and organometallic chemistry:relevance of metal hydride bonds and dihydrogen. Chem. Soc. Rev. 43, 547–564 (2014).

Singh, A. R. et al. Computational design of active site structures with improved transition-state scaling for ammonia synthesis. ACS Catal. 8, 4017–4024 (2018).

Cao, Y. et al. Ammonia synthesis via an associative mechanism on alkaline earth metal sites of Ca3CrN3H. ChemSusChem 16, e202300234 (2023).

Han, G. F. et al. Mechanochemistry for ammonia synthesis under mild conditions. Nat. Nanotechnol. 16, 325–330 (2021).

Higham, M. D. et al. Mechanism of ammonia synthesis on Fe3Mo3N. Faraday Discuss. 243, 77–96 (2023).

Li, Z. et al. Multiple reaction pathway on alkaline earth imide supported catalysts for efficient ammonia synthesis. Nat. Commun. 14, 6373 (2023).

Shao, L. et al. Structures and ammonia synthesis activity of hexagonal ruthenium iron nitride phases. iScience 27, 110795 (2024).

Zhang, K. et al. Spin-mediated promotion of Co catalysts for ammonia synthesis. Science 383, 1357–1363 (2024).

Zhou, Y. et al. Precious-metal-free Mo-MXene catalyst enabling facile ammonia synthesis via dual sites bridged by H-spillover. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 146, 23054–23066 (2024).

Jacobsen, C. J. et al. Catalyst design by interpolation in the periodic table: bimetallic ammonia synthesis catalysts. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 123, 8404–8405 (2001).

Maksoud, W. A. et al. Silicon clathrate-supported catalysts with low work functions for ammonia synthesis. Adv. Mater. 36, 2406944 (2024).

Miyazaki, M. et al. BaTiO3-xNy: highly basic oxide catalyst exhibiting coupling of electrons at oxygen vacancies with substituted nitride ions. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 145, 25976–25982 (2023).

Gong, Y. et al. Ternary intermetallic LaCoSi as a catalyst for N2 activation. Nat. Catal. 1, 178–185 (2018).

Daisley, A. et al. Experimental and theoretical investigations on the anti-perovskite nitrides Co3CuN, Ni3CuN and Co3MoN for ammonia synthesis. Faraday Discuss. 243, 97–125 (2023).

Guan, Y. et al. Light-driven ammonia synthesis under mild conditions using lithium hydride. Nat. Chem. 16, 373–379 (2024).

Kim, J. H. et al. Achieving volatile potassium promoted ammonia synthesis via mechanochemistry. Nat. Commun. 14, 2319 (2023).

Sobhi, S. A. et al. A Comparison of the reactivity of the lattice nitrogen in tungsten substituted Co3Mo3N and Ni2Mo3N. ChemSusChem 16, e202300945 (2023).

Li, L. et al. Size sensitivity of supported Ru catalysts for ammonia synthesis: from nanoparticles to subnanometric clusters and atomic clusters. Chem 8, 749–768 (2021).

Wu, J. et al. Tiered electron anions in multiple voids of LaScSi and their applications to ammonia synthesis. Adv. Mater. 29, 1700924 (2017).

Kitano, M. et al. Ammonia synthesis using a stable electride as an electron donor and reversible hydrogen store. Nat. Chem. 4, 934–940 (2012).

Wang, Q. et al. Ternary ruthenium complex hydrides for ammonia synthesis via the associative mechanism. Nat. Catal. 4, 959–967 (2021).

Wu, J. et al. Intermetallic electride catalyst as a platform for ammonia synthesis. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 58, 825–829 (2019).

Kitano, M. et al. Electride support boosts nitrogen dissociation over ruthenium catalyst and shifts the bottleneck in ammonia synthesis. Nat. Commun. 6, 6731 (2015).

Lu, Y. et al. Water durable electride Y5Si3: electronic structure and catalytic activity for ammonia synthesis. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 138, 3970–3973 (2016).

Ogawa, T. et al. High electron density on Ru in intermetallic YRu2: the application to catalyst for ammonia synthesis. J. Phys. Chem. C. 122, 10468–10475 (2018).

Zeng, R. et al. Precise tuning of the d-band center of dual-atomic enzymes for catalytic therapy. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 146, 10023–10031 (2024).

Ai, X. et al. Transition-metal-boron intermetallics with strong interatomic d-sp orbital hybridization for high-performance electrocatalysis. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 59, 3961–3965 (2020).

Furukawa, S. & Komatsu, T. Intermetallic compounds: promising inorganic materials for well-structured and electronically modified reaction environments for efficient catalysis. ACS Catal. 7, 735–765 (2016).

Nakaya, Y. & Furukawa, S. Catalysis of alloys: classification, principles, and design for a variety of materials and reactions. Chem. Rev. 123, 5859–5947 (2023).

Shields, B. J. et al. Bayesian reaction optimization as a tool for chemical synthesis. Nature 590, 89–96 (2021).

Tao, H. et al. Nanoparticle synthesis assisted by machine learning. Nat. Rev. Mater. 6, 701–716 (2021).

Yao, Z. et al. Machine learning for a sustainable energy future. Nat. Rev. Mater. 8, 202–215 (2023).

Butler, K. T. et al. Machine learning for molecular and materials science. Nature 559, 547–555 (2018).

Julian, A. H. et al. Accelerated dinuclear palladium catalyst identification through unsupervised machine learning. Science 374, 1134–1140 (2021).

Li, X. et al. Sequential closed-loop Bayesian optimization as a guide for organic molecular metallophotocatalyst formulation discovery. Nat. Chem. 16, 1286–1294 (2024).

Tran, K. & Ulissi, Z. W. Active learning across intermetallics to guide discovery of electrocatalysts for CO2 reduction and H2 evolution. Nat. Catal. 1, 696–703 (2018).

Zhai, S. et al. A combined ionic Lewis acid descriptor and machine-learning approach to prediction of efficient oxygen reduction electrodes for ceramic fuel cells. Nat. Energy 7, 866–875 (2022).

Zhong, M. et al. Accelerated discovery of CO2 electrocatalysts using active machine learning. Nature 581, 178–183 (2020).

Wang, Z. et al. Machine learning-accelerated discovery of A2BC2 ternary electrides with diverse anionic electron densities. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 145, 26412–26424 (2023).

Kresse, G. & Furrbmiiller, J. Efficiency of ab-initio total energy calculations for metals and semiconductors using a plane-wave basis set. Comput. Mater. Sci. 6, 15–50 (1996).

Kresse, G. & Joubert, D. From ultrasoft pseudopotentials to the projector augmented-wave method. Phys. Rev. B 59, 1758–1775 (1999).

Heyden, A., Bell, A. T. & Keil, F. J. Efficient methods for finding transition states in chemical reactions: comparison of improved dimer method and partitioned rational function optimization method. J. Chem. Phys. 123, 9978–9985 (2005).

Perdew, J. P., Burke, K. & Ernzerhof, M. Errata: generalized gradient approximation made simple. Phys. Rev. Lett. 78, 1396 (1997).

Anisimov, V. V., Zaanen, J. & Andersen, O. K. Band theory and Mott insulators: Hubbard U instead of Stoner I. Phys. Rev. B Condens. Matter 44, 943–954 (1991).

Waller, O. et al. Lattice dynamics of neodymium: influence of 4f electron correlations. Phys. Rev. B 94, 014303 (2016).

Mathew, K. et al. Implicit solvation model for density-functional study of nanocrystal surfaces and reaction pathways. J. Chem. Phys. 140, 9901 (2000).

Wang, V., Xu, N. & Liu, J. C. VASPKIT: a user-friendly interface facilitating high-throughput computing and analysis using VASP code. Comput. Phys. Commun. 267, 108033 (2021).

Häussermann, U. et al. FeGa3 and RuGa3: semiconducting intermetallic compounds. J. Solid State Chem. 165, 94–99 (2002).

Ravel, B. & Newville, M. Athena, Artemis, Hephaestus: data analysis for X-ray absorption spectroscopy using IFEFFIT. J. Synchrotron Radiat. 12, 537–541 (2005).

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (22275121, 21931005, 22105122), National Key R&D Program of China (2023YFA1506300), Shanghai Municipal Education Commission (2024AIYB007), Shanghai Municipal Science and Technology Major Project, Fundamental Research Funds for the Central Universities (23 × 010301599, 24 × 010301678), the project of Jiangxi Academy of Sciences (2023YSTZX01). H.H. acknowledges a support by the JST-Mirai Program (JPMJMI21E9) from JST. The XAFS data was collected at beamline BL14W1 of the Shanghai Synchrotron Radiation Facility (SSRF, China).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

T.-N.Y. conceived the idea and supervised the project. Z.L. M.Z., Y.L., J.L., W.L., K.Q., X.L., M.X., B.D. and Y.Q. performed the synthesis, characterization, and catalytic measurements. Z.L. conducted the machine learning and DFT calculations. X.S. and R.T. helped with the XAFS measurements. Q.Z. helped with the STEM measurements. Z.L., Y.L., H.H., J.-S.C., and T.-N.Y. co-wrote the paper with input from all authors.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Peer review

Peer review information

Nature Communications thanks Yoji Kobayashi and the other, anonymous, reviewer(s) for their contribution to the peer review of this work. A peer review file is available.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Li, Z., Zhang, M., Su, X. et al. Machine learning-assisted Ru-N bond regulation for ammonia synthesis. Nat Commun 16, 7818 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-025-63064-3

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-025-63064-3