Abstract

Nature-inspired high-spin FeIV = O generation enables efficient ambient methane oxidation. By engineering sulfur-bridged dual ≡FeII…FeII≡ sites on pyrite (FeS2) mimicking soluble methane monooxygenase, we achieve O2-driven formation of high-spin (S = 2) surface FeIV = O species at room temperature and pressure. Strategic removal of bridging S atoms creates active sites that facilitate O2 activation via transient ≡Fe-O-O-Fe≡ intermediates, promoting homolytic O − O bond cleavage. The resulting FeIV = O exhibits an asymmetrically distorted coordination environment that reduces the crystal field splitting and favors the occupation of higher energy d-orbitals with unpaired electrons. Impressively, this configuration can efficiently convert CH4 to CH3OH through an oxygen transfer reaction with a synthetic efficiency of TOF = 27.4 h−1 and selectivity of 87.0%, outperforming most ambient O2-driven benchmarks under comparable conditions and even surpassing many H2O2-mediated systems. This study offers a facile method to synthesize high-spin surface FeIV = O and highlights the importance of metal spin state tailoring on non-enzymatic methane activation.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Methane (CH4), the primary constituent of natural gas, has motivated scientists to utilize this light alkane as the starting material or building block to produce energy-intensive fuels and massive chemicals, which can simultaneously mitigate its greenhouse effect1,2,3. Current industrial strategy involves reforming CH4 into syngas (CO plus H2), followed by the Fischer–Tropsch process operated at temperatures ranging from 150 to 300 °C and pressures between 1 and 5 MPa to produce liquid hydrocarbons, such as methanol (CH3OH)4. Nevertheless, the capital-intensive and infrastructure-demanding nature of such thermal-driven routes is unfriendly to small facilities and decentralized areas like offshore drilling platforms or shale gas sites, where the economic challenge of transporting CH4 often results in the common practice of flaring5,6. Consequently, selective CH4 oxidation under mild conditions has been regarded as a “Holy Grail” in chemistry7. Unfortunately, the non-polar tetrahedral structure of CH4 endows it with a high C-H bond dissociation energy of 439.3 kJ mol−1, greatly disfavoring its activation8. Thus, strong and costly oxidants such as fuming sulfuric acid, nitrous oxide, hydroperoxide, or ozone are usually employed for the CH4 activation by means of homogeneous or supported catalytic transitional metal centers9.

Molecular oxygen (O2) is the greenest and most economical oxidant for CH4 activation, offering a cost-effective alternative for upgrading CH4. However, the spin-forbidden nature of the direct reaction between triplet-state O2 and singlet-state CH4 requires higher reaction temperatures to overcome the spin-state mismatch and facilitate the reaction, typically above 100 °C10. Impressively, nature has demonstrated superior efficiency in converting CH4 into CH3OH at ambient temperature via metalloenzymes like soluble methane monooxygenase (sMMO), which employs a diiron (II) center to activate O2, facilitate homolytic O−O cleavage, and generate high-valent iron-oxo (FeIV = O) species (Fig. 1a)11. Although significant efforts have been dedicated to mimicking the functionality of sMMO through synthesizing non-heme diiron(II)-complex or immobilizing dual FeII centers on zeolites and metal-organic frameworks, these artificial systems, when using O2 as the terminal oxidant, frequently generate FeIV = O in intermediate-spin states, resulting in diminished reactivity compared to enzymatically generated high-spin FeIV = O species12,13,14.

a Schematic illustration of the diiron(II) centers for O2 adsorption in the hydroxylase component of soluble methane monooxygenase (sMMO, Protein Data Bank 1MTY). b Distribution of dual ≡FeII (≡ denotes material surface) on the FeS2 plane, showing the spatial repulsion from the bridging S atoms upon O2 adsorption.

Pyrite is an abundant, non-toxic, and inexpensive sulfur-containing mineral with the chemical formula of FeS2, which is widely applied in environmental control, electrochemistry, and photovoltaics15. It features an abundant 5-coordinated ≡FeII (FeII on the FeS2 surface) bridged by S atoms (≡FeII−S−FeII ≡ ) on its surface, making it a suitable dual ≡FeII carrier for the O2 activation (Fig. 1b)16. Unfortunately, the direct O−O Bond dissociation in O2 on FeS2 to form high-spin FeIV = O is spatially and energetically challenged. First, the large atomic radius of the bridging S atoms will sterically hinder the O2 adsorption onto the ≡FeII − S − FeII≡ site17. Second, the strong ligand field exerted by bonding S atoms could increase the energy gap between the d orbitals of Fe, resulting in extensive crystal field splitting that inadvertently leads to the formation of low-spin ≡FeII with tightly paired electrons18. Such an electronic configuration further impedes the efficient electron transfer necessary for cleaving the energy-demanding O−O bond and the subsequent formation of high-spin FeIV = O. Addressing these challenges requires precise engineering of the geometric structure of dual ≡FeII sites and careful modulation of the ligand field properties in FeS2, which are crucial for facilitating efficient O2 dissociation and the subsequent generation of high-spin FeIV = O under ambient conditions.

In this study, we demonstrate that constructing dual ≡FeII…FeII≡ sites by removing bridged S atoms on the (001) surface of FeS2 enable homolytic O2 dissociation to generate high-spin surface FeIV = O, achieving a functional emulation of sMMO’s O2 activation strategy. Comprehensive theoretical calculations and extensive microscopic characterizations were employed to check how sulfur deficiencies affected the adsorption and activation behaviors of O2, the crystal field symmetry of dual ≡FeII…FeII≡ sites, and the formation of high-spin FeIV = O. The reactivity of generated high-spin FeIV = O towards selective oxidation of CH4 to CH3OH with O2 as the oxidant at room temperature and pressure was evaluated, aiming to develop an efficient non-enzymatic method for selective CH4 conversion.

Results

Theoretical insights into O2 activation and surface high-spin FeIV = O synthesis

The thermodynamically lowest-energy (001) surface of FeS2 is composed of 5-coordinated sulfur-bonded ≡FeII (FeII on the FeS2 surface) in a tetragonal pyramid (TGP) geometry. The strong ligand field imposed by bonding S atoms leads to the arrangement of valence electrons into stable pairs across the Fe 3 d orbitals according to crystal field theory, resulting in a low-spin (S = 0) state for 5-coordinated FeII (Fig. 2a)19. According to density functional theory (DFT) calculations, the removal of the outermost bridging S atom connected to two sublayers of Fe atoms (≡FeII−S−FeII≡) was exothermic by 2.45 eV (SI Fig. S1), resulting in the formation of structurally-distorted dual 4-coordinated surface FeII (≡FeII…FeII ≡ ) sites with an interatomic distance of 3.52 Å. The bridging S removal process also broke the local symmetry of dual ≡FeII atoms and changed their coordination environment to a distorted tetrahedron (TH) geometry, which resulted in a new electronic configuration of (dz2)2(dx2-y2)2(dxy)1(dxz)1 with an intermediate-spin state (S = 1) (Fig. 2b and Fig. S2). Spin density diagrams further revealed a higher spin distribution at the dual tetrahedral 4-coordinated ≡FeII…FeII≡ sites compared to the tetragonal 5-coordinated ≡FeII sites on FeS2, with a notable reduction in spin symmetry as evidenced by density of state (DOS) calculations (Fig. 2c and SI Fig. S3)20.

a Top view of optimized FeS2(001) surface, showing the 5-coordinated ≡FeII and the corresponding distribution of valence electrons in a tetragonal pyramid (TGP) geometry within the Fe 3 d orbital. The compass with axis labels illustrates the rotation of the structure model of 5-coordinated ≡FeII. b Top view of optimized Fe…Fe@FeS2 surface, containing dual ≡FeII…FeII≡ sites by removing a bridging S atom and the corresponding distribution of valence electrons in a tetrahedron (TH) geometry. The compass with axis labels illustrates the rotation of the structure model of 4-coordinated ≡FeII. c Optimized planar structure of FeS2 and Fe…Fe@FeS2 alongside two-dimensional spin density diagrams; “L” and “H” represent the low and high spin intensity, respectively. Adsorption of O2 on (d) 5-coordinated ≡FeII site of pristine FeS2 surface in an end-on mode and (e) dual 4-coordinated ≡FeII…FeII≡ sites of Fe…Fe@FeS2 surface in a bridging mode. The charge density difference after O2 adsorption is also depicted. The blue and red iso-surfaces represent charge accumulation and depletion in the space, respectively, with an iso-value of 0.010 au. Mulliken charge analysis was used to determine the number of transferred electrons. f Free energy changes plotted against the reaction coordinate for O2 dissociation and surface FeIV = O formation on FeS2 and Fe…Fe@FeS2 surface. The dashed box presents the distribution of valence electrons within a trigonal bipyramid (TBP) geometry in the Fe 3 d orbital of surface FeIV = O. The compass with axis labels illustrates the rotation of the structure model of a 5-coordinated FeIV = O species.

The enlarged spatial sizes and enhanced electron flexibility arisen from dual ≡FeII…FeII≡ engineering, along with spin state alternations, was considered highly desirable for facilitating the O2 adsorption and activation21. To validate this hypothesis, broader DFT calculations were carried out. On the defect-free FeS2 (001) surface, O2 was adsorbed at the 5-coordinated FeII in a terminal end-on configuration, with electrostatic repulsion from the neighboring S atom causing the deflection of the apical O atom (Fig. 2d). Despite the considerable adsorption energy of −2.48 eV, the chemisorbed O2 underwent weak activation with marginal stretching of O−O bond from 1.21 Å to 1.33 Å, accompanied by a population of 0.26 e (SI Figs. S4 and S5a). Subsequently, we examined the heterogeneous O2 adsorption on the FeS2(001) surface bearing dual ≡FeII…FeII≡ sites. Atomic relaxations demonstrated that dual 4-coordinated ≡FeII…FeII≡ sites could effectively activate O2 into a bridging-mode diiron O–O complex (≡Fe−O−O−Fe≡) with an enormous adsorption energy of −4.26 eV. This strengthened O2 activation was realized by a substantial electron transfer (0.82 e) from dual ≡FeII…FeII≡ to the π* antibonding orbitals of O2, resulting in the sharp lengthening of O−O bond to 1.48 Å (Fig. 2e, SI Fig. 5b-d and S6)22. Further homolytic cleavage of O − O bond occurred spontaneously in a barrierless behavior, leading to the formation of surface FeIV = O species. The Fe = O bond of the resulting terminal FeIV = O species was around 1.64 Å, indicative of a prototypical double bond23. In contrast, the O2 dissociation on the 5-coordinated ≡Fe site of FeS2 surface was endothermic and faced a considerable kinetic barrier of +3.43 eV (Fig. 2f). Notably, the Fe core in the FeIV = O on the dual ≡FeII…FeII≡ sites manifested an asymmetrically distorted coordination referred to as a trigonal-bipyramidal (TBP) geometry (Fig. S7). This asymmetric geometry reduced crystal field splitting that promoted the occupation of higher energy d-orbitals, resulting in a high-spin state of S = 2, characterized by an electron configuration of (dx2-y2)1(dxy)1(dyz)1(dxz)1 (Fig. 2f). The formation of high-spin FeIV = O featured an accessible empty dz2 orbital with decent reactivity towards C-H substrates24.

Synthesis and characterizations of FeS2 with dual ≡FeII…FeII≡ sites

Driven by the theoretical insights, we endeavored to synthesize FeS2 with a (001) surface exposed containing dual ≡FeII…FeII≡ sites through a hydrothermal chemical method followed by vacuum annealing to drive the thermal desorption of bridging S atoms denoted as Fe…Fe@FeS2 (SI Fig. S8)25. The X-ray diffraction (XRD) patterns revealed that the pristine FeS2 and as-prepared Fe…Fe@FeS2 were phase-pure pyrite (PDF # 42–1340) (SI Fig. S9). Scanning electron microscopy (SEM), transmission electron microscopy (TEM), and Brunauer−Emmett−Teller (BET) analysis demonstrated that Fe…Fe@FeS2 well maintained the cubic morphology and surface area of FeS2 (Fig. 3a and SI Figs. S10–S12)16. The high-resolution transmission electron microscopy (HRTEM) image of pristine FeS2 revealed two clear fingerprint lattice fringes of 0.54 and 0.39 nm indexed to (010) and (110) crystal planes of pyrite FeS2, respectively, thus confirming the predominant exposure of (001) surface (Fig. 3b and SI Fig. S13a)25. Following vacuum heat treatment, part of the lattice fringes of FeS2 became blurred, possibly owing to the formation of sulfur vacancies (Fig. 3c and SI Fig. S13b). This proposition was validated by high-angle annular dark-field scanning transmission electron microscopy (HAADF-STEM). Compared with FeS2, a well-ordered, alternating arrangement of heavy Fe and light S atoms, several distinct fadings of dark spots were discerned in the aberration-corrected HAADF-STEM image of Fe…Fe@FeS2, ascribed to the loss of outermost S atoms on the Fe…Fe@FeS2 surface (Fig. 3d, e). As further supported by setting the HADDF-STEM images as temperature-colored patterns to improve their atomic contrast, the intensity profile curves of Fe…Fe@FeS2, which were taken along the white line across the interatomic Fe interval, exhibited weaker signals of the S atom than those of the FeS2 counterpart (Fig. 3f–i and SI Fig. S14)26. Electron energy loss spectroscopy (EELS) mapping results also provided direct nanoscale evidence of S deficiency on the Fe…Fe@FeS2 surface (Fig. S15). More importantly, the measured interatomic ≡FeII distances of 3.66 Å in FeS2 and corresponding ≡FeII distances of 3.55 Å in Fe…Fe@FeS2, matched well with the theoretical values of 3.65 Å and 3.52 Å (Fig. 3f, g and SI Figure S16), further confirming the successful construction of dual ≡FeII…FeII≡ sites on the (001) surface of FeS2 through the removal of bridging S atoms.

a SEM image of the as-prepared Fe…Fe@FeS2. HRTEM images of (b) FeS2 and (c) Fe…Fe@FeS2, the inset white rectangle highlights the blurred areas. HAADF-STEM images of (d) FeS2 and (e) Fe…Fe@FeS2, the insets are the theoretical FeS2 model (Fe: green; S: red; S vacancy: black), and the dashed rectangle in Fig. 3e indicates the S vacancy region. The corresponding temperature-colored HAADF-STEM images of (f) FeS2 and (g) Fe…Fe@FeS2. The image intensity line profiles of (h) FeS2 and (i) Fe…Fe@FeS2, which were taken along the white lines in Figs. 3f and g. j 1/χ versus temperature plots of FeS2 and Fe…Fe@FeS2, with calculated μeff. k XPS spectra of Fe 2p for FeS2 and Fe…Fe@FeS2. l Fourier transformation of k2-weighted Fe extended XAFS of FeS2 and Fe…Fe@FeS2, and a schematic illustration of the formation of dual ≡FeII…FeII≡ sites by removing a bridging S from the pristine FeS2 surface.

We subsequently employed surface-sensitive characterization techniques to investigate the local coordination environment and electronic structure of the dual ≡FeII…FeII≡ sites. Temperature-dependent magnetization (M−T) tests and related magnetic techniques first revealed the effective magnetic moments (μeff) of FeS2 and Fe…Fe@FeS2 were 0.32 μB and 2.38 μB, respectively, corresponding to unpaired d electron numbers (n) of 0 and 2 (Fig. 3j and SI Figs. S17–S22)27,28. These values validated the low-spin (S = 0) nature of 5-coordinated ≡FeII and intermediate-spin (S = 1) state of dual 4-fcoordinated ≡FeII…FeII ≡ , agrees well with the theoretical results shown in Fig. 1a, b. The Fe 2p XPS spectrum experienced a slight shift toward lower binding energies due to the electron localization within the dual ≡FeII…FeII≡ sites following S removal on the FeS2 surface (Fig. 3k and SI Fig. S23)16. The emergence of an electron paramagnetic resonance (EPR) signal at g = 2.0026 was ascribed to unpaired electrons localized at S vacancy sites (SI Fig. S24)29. This observation was further corroborated by the redshift of characteristic pyrite FeS2 Raman peaks, particularly in the vibration modes at Eg ≈ 347 cm−1 and stretching at Ag ≈ 384 cm−1, owing to the phonon confinement effects caused by sulfur vacancies (SI Fig. S25)30. In the X-ray absorption near-edge structure (XANES), the rising edge of the normalized Fe K edge spectrum of Fe…Fe@FeS2 was lower than that of FeS2 but greater than that of metallic Fe foil, further confirming electron localization on the dual ≡FeII…FeII≡ sites (SI Fig. S26). Moreover, the Fourier transform of the Fe K-edge extended XAFS oscillation revealed a lower coordination number (CN ≈ 4.38) for the first shell of Fe−S in Fe…Fe@FeS2 compared to that of FeS2 (CN ≈ 5.45). This observation was consistent with optimized theoretical models that disclosed the transition from 5-coordinated ≡FeII bridged by S atoms (≡FeII−S−FeII≡), to a 4-coordinated ≡FeII within the dual sites following the removal of bridging S atoms (Fig. 3l, SI Fig. S27 and Table S1). Furthermore, temperature programmed desorption (TPD) using H2S as the probe molecule and Fourier transform infrared spectroscopy (FTIR) with thioglycolic acid adsorption demonstrated the site-specific chemical reactivity of the S vacancy-derived dual ≡FeII…FeII≡ sites (SI Figs. S28 and S29).

Mechanistic investigation of high-spin surface FeIV = O for methane activation

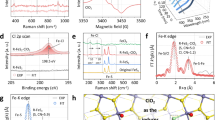

After gaining structural and electronic insights into the dual ≡FeII…FeII≡ sites on Fe…Fe@FeS2, we experimentally investigated their capacity for direct O2 dissociation and high-spin FeIV = O synthesis. The TPD profile of pristine FeS2 first revealed that pre-exposure to O2 resulted in chemisorbed O2 peaks at approximately 350 °C (Fig. 4a and SI Fig. S30)31. In contrast, a new signal associated with O2 dissociation emerged at around 375 °C for the Fe…Fe@FeS2 sample (Fig. 4a and SI Fig. S30). To gain mechanistic insight into O−O bond cleavage process during O2 dissociation, isotope exchange experiments were conducted under room temperature with 16O2 and 18O2 as the feeding gases at a molar ratio of 1:132. Interestingly, the time-resolved 16O18O signal stemmed from isotopic 16O-18O recombination was significantly more pronounced on the Fe…Fe@FeS2 surface than that on the FeS2 surface, indicative of spontaneous and robust dissociation of O2 at dual ≡FeII…FeII≡ sites (Fig. 4b). We then employed low-temperature EPR to probe the dissociated oxygen species, taking advantage of its exceptional sensitivity towards reactive surface-bound radicals33. The X-band EPR spectra of Fe…Fe@FeS2 displayed strong g anisotropy attributed to specific •O3− species with g1 = 2.011, g2 = 2.002, and g3 = 1.997, suggesting the interaction between transient •O− radical derived from the effectively reductive dissociation of O2 and molecular O2 on the Fe…Fe@FeS2 surface (Fig. 4c and SI Fig. S31)34,35. Given the high reactivity of •O− radical, it may react with the bound Fe site to form FeIV = O species on the Fe…Fe@FeS2 surface21,36.

a TPD profiles showing the mass signal of O2 for FeS2 and Fe…Fe@FeS2 at the temperature range of 200 to 450 °C. b Online mass spectrometry profiles of oxygen isotopologue exchange for FeS2 and Fe…Fe@FeS2, and a schematic illustration of dioxygen dissociation and oxygen recombination at the dual ≡FeII…FeII≡ sites. c Low-temperature EPR spectra of O2 activation and dissociation on Fe…Fe@FeS2. d57Fe Mössbauer spectrum of FeS2 and Fe…Fe@FeS2 treated by O2; Experimental and model-fitted data are shown as white circles and gray lines, respectively. e 1/χ versus temperature plots for Fe…Fe@FeS2 treated by O2 with calculated μeff. f Determination of localized electron concentrations in FeS2 and Fe…Fe@FeS2 using TEMPO as the standard and Mn(II) as the reference in EPR, and the concentration of generated FeIV = O in the aqueous FeS2/O2/PMSO and Fe…Fe@FeS2/O2/PMSO systems. Reaction condition: [sample]0 = 1.0 g L−1, [PMSO]0 = 60 mmol L−1, reaction time = 180 min. g In situ FTIR spectra of CH4 and O2 adsorption on FeS2 and Fe…Fe@FeS2. h Schematic illustration of O2 activation and selective CH4 oxidation to CH3OH by high-spin FeIV = O at the dual ≡FeII…FeII≡ sites.

To further validate the formation of FeIV = O in diverse spin states, 57Fe Mössbauer spectroscopy analysis was carried out. The isomer shift (δ) and quadrupole splitting (∆EQ) values can reflect the valence state and electronic structure at the 57Fe nucleus measured following exposure to O237. The Mössbauer spectroscopy results revealed that FeS2 treated by O2 exclusively exhibited a combination of two split doublets arising from structural FeII and FeIII species, while a new separate doublet corresponding to the FeIV state of FeIV = O species was exclusively observed for Fe…Fe@FeS2 case (Fig. 4d, SI Fig. S32 and Table S2). Meanwhile, the fitted parameters of Mössbauer spectroscopy featuring δ = 0.04 mm/s and |∆EQ | = 1.20 mm/s robustly supported the high-spin nature (S = 2) of the as-formed FeIV = O species (SI Table S2)23,36. As corroborated by the temperature-dependent magnetization (M−T) test, this FeIV = O species with a high spin state (S = 2) displayed a double degenerate set of (x2-y2, xy) and (xz, yz) orbitals in its distorted trigonal-bipyramidal (TBP) geometry, which performed the single electron spinning and rendered a reactive low-lying dz2 orbital (Fig. 4e)28. With 2, 2, 6, 6-tetramethyl-1-piperadoxyl (TEMPO) as the spin electron probe and methyl phenyl sulfoxide (PMSO) as the FeIV = O trapping molecule, we quantified both the concentration of localized electrons at the dual ≡FeII…FeII≡ sites and the resulting production of FeIV = O species (SI Figs. S33–S35)38,39. Impressively, the total aerobic concentration of FeIV = O species was approximately 16 times higher than the amount of localized electrons at dual ≡FeII…FeII≡ sites, highlighting steady O2 dissociation and FeIV = O formation on the Fe…Fe@FeS2 surface (Fig. 4f).

We then carried out in situ FTIR experiments to elucidate the mechanism of high-spin FeIV = O in promoting CH4 activation40. The exposure of O2 and CH4 to FeS2 induced a stretching vibration at 1085 cm−1 attributed to surface adsorbed •O2- species. Another two signals appeared at 1305 and 3010 cm-1 were assigned to the weak adsorption of CH4 on the FeS2 surface (Fig. 4g and SI Fig. S36)41. In contrast, Fe…Fe@FeS2 showed no absorbance related to •O2- species, while two distinct resonance peaks located at 1150 and 840 cm−1 emerged, attributed to the vibration frequencies of the bridging ≡Fe−O − O−Fe≡ complex as predicted by theoretical calculations and the resultant formation of FeIV = O species, respectively (Fig. 4g and SI Fig. S36)16,23. Concurrent with the formation of FeIV = O, a prominent peak associated with C-O stretching of surface *OCH3 species emerged at around 1020 cm−1, validating the instant activation and oxidation of CH4 to CH3OH by high-spin FeIV = O species (FeIV=O + CH4 → FeII + CH3OH) (Fig. 4g)42. Thus, the dual ≡FeII…FeII≡ sites of the Fe…Fe@FeS2 surface is vital to facilitate the O2 dissociation into high-spin FeIV = O via forming a bridging ≡Fe−O−O−Fe≡ complex, which energetically enables the selective activation of CH4 under ambient conditions (Fig. 4h).

Selective oxidation of methane to methanol

The capability of Fe…Fe@FeS2 in selectively oxidizing CH4 to CH3OH with O2 at a room temperature of 25 °C and ambient pressure of 1 bar was showcased, using CH4 (1%, Ar equilibrium) as the feeding gas and water as the solvent in a sealed reactor43. Batch experiments revealed negligible consumption of CH4 by pristine FeS2, irrespective of the presence or absence of O2 (SI Fig. S37a). In the O2-free aqueous environment, a small amount of CH4 was transformed into CH3OH with a yield of 0.09 μmol h−1 and selectivity of 39.2% by Fe…Fe@FeS2, but quickly reaching an equilibrium (Fig. 5a and SI Fig. S37b). As expected, the addition of O2 remarkably increased the CH3OH yield to 0.71 μmol h−1 with 60.8% selectivity by Fe…Fe@FeS2, indicating that O2 was the source oxidant for the selective oxidation of CH4 to CH3OH (Fig. 5a and SI Table S3). Control experiments, varying the Fe…Fe@FeS2 amount, displayed a volcano-shaped reactivity for selective CH4 oxidation (SI Table S3)44. Analysis of products using gas chromatography (GC) and 1H nuclear magnetic resonance (NMR) spectroscopy confirmed that CH4 was predominantly converted into CH3OH, with tiny amounts of HCOOH and no signs of overoxidation products such as CO and CO2 (SI Fig. 38)45.

To address the low solubility of CH4 and O2 in water, we then optimized the CH4 oxidation experiments in a binary solution containing perfluorohexane (PFH) and water. The aprotic PFH with a non-polar characteristic can accumulate CH4 and O2 in the reaction zone, while the polar water spontaneously collects the product CH3OH to prevent it from overoxidation through polarity difference (Fig. 5b)46. Intriguingly, the efficient accumulation and concurrent protection mechanism in the binary solution containing 5 mL H2O and 5 mL PFH remarkably increased the CH3OH yield of Fe…Fe@FeS2 to 2.47 μmol h−1 and the selectivity to 87.0% (Fig. 5c, SI Fig. S39 and Table S3). To the best of our knowledge, the turn frequency (TOF = CH3OH yield/reactive site) of Fe…Fe@FeS2, which was calculated to be 27.4 h−1 and outperformed most ambient O2-driven benchmarks under comparable conditions and even surpassed many H2O2-mediated systems (Fig. 5d, SI Fig. S40 and Table S4)47. The different partial pressure experiments revealed a higher reaction order of O2 (0.77) than CH4 (0.31), demonstrating that the O2 activation was more kinetic for CH3OH production in our reaction system, consistent with the theoretical calculations (SI Table S5 and Fig. S41). More importantly, the Fe…Fe@FeS2 could successfully be recovered from the aqueous medium through facial centrifugation and heat treatment, allowing for multiple reuse cycles while maintaining high efficiency and selectivity (Fig. 5e, SI Figs. S42 and S43). Subsequently, the isotope labeling experiments were carried out to trace the origins of C and O in the CH4 oxidation process using 13C-labeled carbon (13C) and 18O-labeled oxygen (18O2)48. Analysis of liquid products by GC-MS revealed a molecular ion signal of CH3OH at the mass-of-charge ratio (m/z) of 32.0, with a prominent deprotonated fragment ([CH3O]+) at m/z = 31.0 (Fig. 4f). Replacing CH4 with 13CH4 and O2 with 18O2 led to a shift in the associated ion peak for CH3OH to m/z 33.1 (13CH3OH) and to m/z 34.0 (CH318OH), respectively, accompanied by the detection of several deprotonated fragments such as [13CH3O]+ or [CH318O]+ (Fig. 5f). These isotope labeling results strongly confirmed that C and O atoms in CH3OH predominantly originated from the oxidation of CH4 by O2 through oxygen atom transfer.

a Performance of selective CH4 oxidation into CH3OH in the aqueous Fe…Fe@FeS2/CH4 and Fe…Fe@FeS2/CH4/O2 systems. b The schematic diagram of selective CH4 oxidation within a binary solution containing perfluorohexane (PFH) and water in a designed reactor, where the gas inlet and outlet balance the pressure of mixture gas (CH4 and O2) at 1 bar, and the condensate inlet and outlet control the reaction temperature to room temperature of 25 °C. c Performance of selective CH4 oxidation into CH3OH in the Fe…Fe@FeS2/CH4/O2 system using 5 mL H2O and 5 mL PFH. d Comparative analysis of TOF and CH3OH selectivity in the Fe…Fe@FeS2/CH4/O2 system versus other gas-liquid-solid three-phase catalytic systems with O2 or H2O2 as the oxidant. e Multi-cycled oxidation of CH4 to CH3OH in the PFH aqueous Fe…Fe@FeS2/CH4/O2 system within 180 min. f Isotopic detection of CH3OH in the Fe…Fe@FeS2/CH4/O2, Fe…Fe@FeS2/13CH4/O2 and Fe…Fe@FeS2/CH4/18O2 systems. Reaction condition: 10 mg Fe…Fe@FeS2, 10 mL solution containing 5 mL H2O and 5 mL PFH, 1 bar gas (CH4 + O2 with a stoichiometric ratio), room temperature. g EPR spectra of *DMPO-•CH3 adducts in the Fe…Fe@FeS2/CH4/O2 system. h Theoretical CH4 molecules adsorption on the high-spin surface FeIV = O of Fe…Fe@FeS2. The charge density difference after CH4 adsorption is also provided. The blue and red iso-surfaces represent charge accumulation and depletion in the space, respectively, with an iso-value of 0.010 au. Mulliken charge calculations were used to determine the number of transferred electrons. i Free energy changes plotted against the reaction coordinate for activation and oxidation of CH4 by high-spin surface FeIV = O on Fe…Fe@FeS2.

We then adopted EPR experiments to re-identify the crucial reactive species responsible for CH4 activation with 5,5-dimethyl- 1-pyrrolidine-N-oxide (DMPO) as a spin-trapping agent to identify the crucial reactive species responsible for CH4 activation. Upon introducing O2, we observed a seven-line signal corresponding to the formation of 5,5-dimethyl-2-pyrrolidone-N-oxyl (DMPOX) adduct resulting from DMPO oxidation by high-spin FeIV = O on Fe…Fe@FeS2, while such a signal was silent for FeS2, suggesting FeS2 cannot dissociate O2 to form high-spin FeIV = O (SI Fig. S44a)49. In contrast, superoxide radical (•O2−) was the dominant reactive oxygen species on FeS2 (SI Fig. S44b). Following the addition of CH4, distinctive sextet DMPO adducts attributed to carbon-centered radical (*DMPO-•CH3) were exclusively observed on Fe…Fe@FeS2, ascribed to the in situ activation of CH4 by high-spin FeIV = O (Fig. 5g)24. Theoretical calculations revealed that upon the formation of high-spin FeIV = O via the O2 at the dual ≡FeII…FeII≡ sites of Fe…Fe@FeS2, CH4 was actively adsorbed by donating an H atom to the terminal O atom of surface ≡FeIV = O, resembling a collinear configuration along the Fe–O axis, with an adsorption energy of 1.40 eV (Fig. 5h). Meanwhile, substantial electron donation (0.64 e) from CH4 to the high-spin ≡FeIV = O site, which featured an energy-accessible empty dz2 orbital, was facilitated via a CH3−H…O=FeIV interaction, effectively elongating the stubborn C-H bond from 1.09 to 1.31 Å (Fig. 4h, SI Figs. S45 and S46)23,50. Subsequent H-abstracting of CH4 by ≡FeIV = O led to the formation of a -CH3 fragment and surface FeIII-OH complex with an inappreciable energy barrier of 0.09 eV(Fig. 5i). This reaction step was followed by an oxygen-rebound process to yield the final CH3OH product and regenerate ≡FeII. The selective oxidation of CH4 to CH3OH by high-spin FeIV = O on Fe…Fe@FeS2 followed a classical H-abstraction/O-rebound mechanism with an exothermicity of 1.45 eV (Fig. 5i)36.

Discussion

We have successfully demonstrated that the challenges associated with synthesizing high-spin FeIV = O species, exhibiting enzymatic reactivity, can be addressed using FeS2 featuring dual ≡FeII…FeII≡ sites with O2 as the oxidant. The dual ≡FeII…FeII≡ sites, obtained by removing the bridging S atom, efficiently interact with the π* antibonding orbitals of O2 via a bridging ≡Fe−O−O−Fe≡ complex. This configuration promotes a homolytic O−O bond cleavage to deliver high-spin surface FeIV = O, featuring an asymmetrically distorted coordination environment that reduces the crystal field splitting and favors the occupation of higher energy d-orbitals with unpaired electrons. Impressively, this high-spin surface FeIV = O can efficiently convert CH4 to CH3OH through oxygen transfer reaction with a synthetic efficiency of TOF = 27.4 h−1 and selectivity of 87.0%, outperforming most ambient O2-driven benchmarks under comparable conditions and even surpassing many H2O2-mediated systems. This study offers a facile method to synthesize high-spin surface FeIV = O and highlights the importance of metal spin state tailoring on non-enzymatic methane activation.

Methods

Theoretical calculations

The theoretical calculations, including structure optimization of FeS2(001) and Fe…Fe@FeS2(001), and heterogeneous activation of O2 and CH4 were performed using the Vienna Ab Initio Simulation Package (VASP) (Supplementary Method 1).

Materials synthesis and characterization

FeS2 was prepared using a one-pot hydrothermal chemical method (Supplementary Method 2). Analytical grade chemicals provided by Sinopharm Chemical Reagent Co., Ltd. (Shanghai, China) were used without purification, and deionized water was utilized in all experiments. Fe…Fe@FeS2 was obtained through a heating treatment of the as-prepared FeS2 sample. Prior to vacuum annealing, FeS2 underwent a 150 °C treatment with a flow rate of 100 mL/min of Ar in a tube furnace for 60 min to desorb surface-adsorbed water, which could potentially react with solid samples at high temperatures and compromise their surface properties. Following dehydration, the tube furnace was rapidly pumped into a vacuum environment while raising the temperature to 400 °C, allowing for thermal treatment of FeS2 for 3 h to remove surface bridging sulfur atoms and thus obtain Fe…Fe@FeS2. Fe…Fe@FeS2 with varying degrees of surface sulfur deficiencies were also prepared by adjusting the heat treatment duration. The morphology, crystal phase, and structural properties of both as-prepared FeS2 and Fe…Fe@FeS2 were characterized by using electron microscopy, X-ray diffraction (XRD), Raman spectroscopy, X-ray photoelectron spectroscopy (XPS), and electron paramagnetic resonance (EPR) (Supplementary Method 3).

Analytic methods

The effective magnetic moment (μeff) and the number of unpaired electrons of the Fe center were determined according to the temperature dependence of magnetic susceptibility (Supplementary Method 4). The interface interaction between reaction gas (O2 and/or CH4) and sample (FeS2 or Fe…Fe@FeS2) was characterized by temperature-programmed desorption (Supplementary Method 5), oxygen isotopologue (16O2 and 18O2) exchange (Supplementary Method 6), and in-situ Attenuated Total Reflection Flourier Transformed Infrared (ATR-FTIR) Spectroscopy (Supplementary Method 7). The qualitative analysis of reactive FeIV = O, •O2−, and *CH3 species was conducted on EPR spectra with 5, 5-dimethyl-1-pyrroline-N-oxide (DMPO) as the radical spin-trapped reagent (Supplementary Method 8). The concentration of localized electrons within FeS2 or Fe…Fe@FeS2 was quantified using EPR with TEMPO as the standard and Mn(II) as the reference (Supplementary Method 9). The concentration of FeIV = O species over the FeS2 or Fe…Fe@FeS2 surface was determined in a high-performance liquid chromatography (HPLC) test with 60 mmol/L of methyl phenyl sulfoxide (PMSO) solution as the FeIV = O species trapping agent (Supplementary Method 10). The 16O/18O isotope-labeled CH3OH product and 12C/13C isotope-labeled oxygenates were analyzed by gas chromatography-mass spectrometry. The determination of generated liquid products was conducted by 1H nuclear magnetic resonance (NMR) with a water suppression pulse using deuterated water (D2O) as an internal standard.

Evaluation of methane conversion performance

Batch experiments of selective CH4 oxidation were conducted in a custom-made reactor with a volume of 300 mL. The reaction temperature was controlled to 25 °C by a circulating water device. A magnetic stirrer was continuously employed throughout the reaction to optimize mass transfer between the reactants and samples. Initially, the sealed reactor underwent a 30-min purge with a gas mixture consisting of O2 (100%) and CH4 (1% CH4 in Argon) at a ratio of 1:1, regulated by two EL-FLOW mass flowmeters (Bronkhorst). Subsequently, 10 mg of samples and 10 mL of binary solution containing perfluorohexane (PFH) and water pre-saturated by the reaction gas mixture of CH4 and O2 were rapidly introduced into the reactor to initiate the CH4 oxidation reaction. The conversion ratio of CH4 at predetermined intervals was determined by measuring its residual amount relative to the initial quantity in the headspace of the reactor. The production yield of CH3OH was quantified by measuring its concentration in the aqueous phase. The gas chromatography (TaiTe, GC2030Smart, China) equipped with a GC water-resistant capillary column (Thermo, TG-WaxMS, 30 m × 0.25 mm × 0.25 μm, America) and a flame ionization detector was used for evaluating the concentrations of CH4 and CH3OH. The potential carbon oxide products were monitored using a GC-FID equipped with a methaniser. All the activity experiments were performed three times, and the results were presented as mean values.

Data availability

All study data are included in the article and Supplementary Information. Soluble methane monooxygenase (sMMO, Protein Data Bank 1MTY) is also presented. Source data are provided with this paper.

References

Hao, S. et al. Photocatalytic CH4-to-ethanol conversion on asymmetric multishelled interfaces. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 146, 25870–25877 (2024).

Xu, Y. et al. Efficient methane oxidation to formaldehyde via photon–phonon cascade catalysis. Nat. Sustain. 7, 1171–1181 (2024).

Yang, Y. et al. Climate change exacerbates the environmental impacts of agriculture. Science 385, eadn3747 (2024).

Sushkevich, V. L., Palagin, D., Ranocchiari, M. & Van Bokhoven, J. A. Selective anaerobic oxidation of methane enables direct synthesis of methanol. Science 356, 523–527 (2017).

Xiong, H. et al. Highly efficient and selective light-driven dry reforming of methane by a carbon exchange mechanism. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 146, 9465–9475 (2024).

Calel, R. & Mahdavi, P. The unintended consequences of antiflaring policies—and measures for mitigation. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA117, 12503–12507 (2020).

Tucci, F. J. & Rosenzweig, A. C. Direct methane oxidation by copper-and iron-dependent methane monooxygenases. Chem. Rev. 124, 1288–1320 (2024).

Meng, X. et al. Direct methane conversion under mild condition by thermo-, electro-, or photocatalysis. Chem 5, 2296–2325 (2019).

Dummer, N. F. et al. Methane oxidation to methanol. Chem. Rev. 123, 6359–6411 (2022).

Wang, W. et al. Selective oxidation of methane to methanol over Au/H-MOR. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 145, 12928–12934 (2023).

Wang, V. C.-C. et al. Alkane oxidation: methane monooxygenases, related enzymes, and their biomimetics. Chem. Rev. 117, 8574–8621 (2017).

Liu, J. et al. Spin-regulated inner-sphere electron transfer enables efficient O-O bond activation in nonheme diiron monooxygenase MIOX. ACS Catal. 11, 6141–6152 (2021).

Jasniewski, A. J. & Que, L. Jr Dioxygen activation by nonheme diiron enzymes: diverse dioxygen adducts, high-valent intermediates, and related model complexes. Chem. Rev. 118, 2554–2592 (2018).

Friedle, S., Reisner, E. & Lippard, S. J. Current challenges of modeling diiron enzyme active sites for dioxygen activation by biomimetic synthetic complexes. Chem. Soc. Rev. 39, 2768–2779 (2010).

Rahman, M. Z. & Edvinsson, T. What is limiting pyrite solar cell performance?. Joule 3, 2290–2293 (2019).

Ling, C. et al. Atomic-layered Cu5 nanoclusters on FeS2 with dual catalytic sites for efficient and selective H2O2 activation. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 134, e202200670 (2022).

Sit, P. H.-L., Cohen, M. H. & Selloni, A. Interaction of oxygen and water with the (100) surface of pyrite: mechanism of sulfur oxidation. J. Phys. Chem. Lett. 3, 2409–2414 (2012).

Rickard, D. & Luther, G. W. Chemistry of iron sulfides. Chem. Rev. 107, 514–562 (2007).

Schmøkel, M. S. et al. Atomic properties and chemical bonding in the pyrite and marcasite polymorphs of FeS2: a combined experimental and theoretical electron density study. Chem. Sci. 5, 1408–1421 (2014).

Dai, J. et al. Spin-polarized Fe1-Ti pairs for highly efficient electroreduction nitrate to ammonia. Nat. Commun. 15, 88 (2024).

Tabor, E. et al. Dioxygen dissociation over a man-made system at room temperature to form the active α-oxygen for methane oxidation. Sci. Adv. 6, eaaz9776 (2020).

Li, H. et al. Vacancy-rich and porous NiFe-layered double hydroxide ultrathin nanosheets for efficient photocatalytic NO oxidation and storage. Environ. Sci. Technol. 56, 1771–1779 (2022).

Hohenberger, J., Ray, K. & Meyer, K. The biology and chemistry of high-valent iron–oxo and iron–nitrido complexes. Nat. Commun. 3, 720 (2012).

Li, M. et al. Highly selective synthesis of surface FeIV= O with nanoscale zero-valent iron and chlorite for efficient oxygen transfer reactions. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA120, e2304562120 (2023).

Ling, C. et al. Sulphur vacancy derived anaerobic hydroxyl radical generation at the pyrite-water interface: Pollutants removal and pyrite self-oxidation behavior. Appl. Catal. B-Environ. 290, 120051 (2021).

Wang, L. et al. Axial dual atomic sites confined by layer stacking for electroreduction of CO2 to tunable syngas. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 145, 13462–13468 (2023).

Zhang, H. et al. Tailoring oxygen reduction reaction kinetics of Fe-N-C catalyst via spin manipulation for efficient zinc–air batteries. Adv. Mater. 36, 2400523 (2024).

Yang, G. et al. Regulating Fe-spin state by atomically dispersed Mn-N in Fe-NC catalysts with high oxygen reduction activity. Nat. Commun. 12, 1734 (2021).

Zhang, C. et al. A review on identification, quantification, and transformation of active species in SCR by EPR spectroscopy. Environ. Sci. Pollut. R. 30, 28550–28562 (2023).

Parkin, W. M. et al. Raman shifts in electron-irradiated monolayer MoS2. ACS Nano 10, 4134–4142 (2016).

Xie, L. et al. Pauling-type adsorption of O2 induced electrocatalytic singlet oxygen production on N–CuO for organic pollutants degradation. Nat. Commun. 13, 5560 (2022).

Huang, Y. L., Pellegrinelli, C. & Wachsman, E. D. Direct observation of oxygen dissociation on non-stoichiometric metal oxide catalysts. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 55, 15268–15271 (2016).

Yang, J. et al. Oxygen vacancy promoted O2 activation over perovskite oxide for low-temperature CO oxidation. ACS Catal. 9, 9751–9763 (2019).

Che, M. & Tench, A. Characterization and reactivity of molecular oxygen species on oxide surfaces. Adv. Catal. 32, 1–148 (1983).

Chiesa, M., Giamello, E. & Che, M. EPR characterization and reactivity of surface-localized inorganic radicals and radical ions. Chem. Rev. 110, 1320–1347 (2010).

Larson, V. A., Battistella, B., Ray, K., Lehnert, N. & Nam, W. Iron and manganese oxo complexes, oxo wall and beyond. Nat. Rev. Chem. 4, 404–419 (2020).

Hou, K. et al. Reactive high-spin iron (IV)-oxo sites through dioxygen activation in a metal-organic framework. Science 382, 547–553 (2023).

Mao, C. et al. Hydrogen spillover to oxygen vacancy of TiO2-xHy/Fe: breaking the scaling relationship of ammonia synthesis. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 142, 17403–17412 (2020).

Ling, C. et al. Symmetry-dependent activation and reactivity of peroxysulfates on FeS2 (001) surface. Sci. Bull. 69, 154–158 (2024).

Mao, J. et al. Direct conversion of methane with O2 at room temperature over edge-rich MoS2. Nat. Catal. 6, 1052–1061 (2023).

Luo, L. et al. Water enables mild oxidation of methane to methanol on gold single-atom catalysts. Nat. Commun. 12, 1218 (2021).

Lyu, Y., Xu, R., Williams, O., Wang, Z. & Sievers, C. Reaction paths of methane activation and oxidation of surface intermediates over NiO on Ceria-Zirconia catalysts studied by In-situ FTIR spectroscopy. J. Catal. 404, 334–347 (2021).

Jin, Z. et al. Hydrophobic zeolite modification for in situ peroxide formation in methane oxidation to methanol. Science 367, 193–197 (2020).

Wang, S. et al. Surface hydrophobization of zeolite enables mass transfer matching in gas-liquid-solid three-phase hydrogenation under ambient pressure. Nat. Commun. 15, 2076 (2024).

Wang, S. et al. H2-reduced phosphomolybdate promotes room-temperature aerobic oxidation of methane to methanol. Nat. Catal. 6, 895–905 (2023).

Ohkubo, K. & Hirose, K. Light-driven C–H oxygenation of methane into methanol and formic acid by molecular oxygen using a perfluorinated solvent. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 57, 2126–2129 (2018).

Zhang, M., Wang, M., Xu, B. & Ma, D. How to measure the reaction performance of heterogeneous catalytic reactions reliably. Joule 3, 2876–2883 (2019).

Song, H. et al. Direct and selective photocatalytic oxidation of CH4 to oxygenates with O2 on cocatalysts/ZnO at room temperature in water. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 141, 20507–20515 (2019).

Wei, S. et al. Self-carbon-thermal-reduction strategy for boosting the Fenton-like activity of single Fe-N4 sites by carbon-defect engineering. Nat. Commun. 14, 7549 (2023).

Mlekodaj, K. et al. Evolution of active oxygen species originating from O2 Cleavage over Fe-FER for Application in Methane Oxidation. ACS Catal. 13, 3345–3355 (2023).

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the National Key Research and Development Program of China (Grant 2023YFC3708002 to L. Z. Z.), the National Natural Science Foundation of China (Grant U22A20402 to L. Z. Z, 22206124 to H. L., 21936003 to L. Z. Z, and 22406127 to M. Q. L.), the China National Postdoctoral Program for Innovative Talents (Grant BX20240219 to M. Q. L.), the China Postdoctoral Science Foundation (Grant 2023M742248 to M. Q. L.), and the Shanghai Post-doctoral Excellence Program (Grant 2023386 M. Q. L.). The authors acknowledge the support from the Instrumental Analysis Center of Shanghai Jiao Tong University and the Instrumental Analysis Center of the School of Environmental Science and Engineering. The authors acknowledge the support from Prof. Xinhao Li (Shanghai Jiao Tong University), and Prof. Jikun Li (Institute of Chemistry, Chinese Academy of Sciences), who contributed to the analysis of the spin properties of FeIV = O, the magnetic properties of FeS2, and the interpretation of the EPR spectra. The authors also acknowledge the support of XAFS and 1H-NMR tests from the Ceshihui (www.ceshihui.cn)

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

L. Z. Z., J. C. Z. and H. L. supervised the project. C. C. L. and H. L. conceived and designed the experiments. C. C. L. conducted material synthesis and characterization and methane oxidation experiments. M. Q. L. conducted DFT calculations. X. F. L., F. R. G., Y. L., and R. Z. contributed to the material synthesis and characterization. C. C. L., H. L. and L. Z. Z. wrote the paper.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Peer review

Peer review information

Nature Communications thanks Yang Lan, Wei Zhou, and the other, anonymous, reviewer(s) for their contribution to the peer review of this work. A peer review file is available.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Source data

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Ling, C., Li, M., Li, H. et al. High-spin surface FeIV = O synthesis with molecular oxygen and pyrite for selective methane oxidation. Nat Commun 16, 7642 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-025-63087-w

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-025-63087-w