Abstract

Nations recently agreed to set aside 30% of the planet by 2030 as conservation areas (the “30 × 30” goal) necessitating major expansions, not just of traditional protected areas like national parks, but also of ‘other effective area-based conservation measures’ (OECMs) – areas that provide de facto benefits to biodiversity despite conservation not being the primary management objective. But evidence for whether OECMs achieve positive biodiversity outcomes remains critically needed. Here we quantify how OECMs contribute to biodiversity conservation in the three high-biodiversity countries in which they have been extensively trialed. OECM performance varies across countries; those in South Africa align better with areas that a priori strategic planning identified as important for species conservation and key ecosystem services than those in Colombia and the Philippines. OECMs tend not to cover areas supporting regional connectivity in any of the countries. OECMs have potential to assist conservation, but policy, planning, and coordination at national and international levels would help ensure that new OECMs are strategically established and effectively managed to enhance outcomes for biodiversity conservation and ecosystem service provisioning.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Major expansions of conservation areas are central to slowing the loss of biodiversity worldwide. Indeed, the United Nations recently adopted the Kunming-Montreal Global Biodiversity Framework that established the target of setting aside 30% of the planet’s surface by 2030 as conservation areas (the “30 × 30” goal)1, arguably representing humanity’s most ambitious conservation strategy to date. Protected areas such as national parks have long been considered the cornerstone of global conservation strategies2,3 and can enhance biodiversity4. However, the nations of the world were unable to meet their earlier commitment of setting aside 17% of land by 20205. Moreover, there are ongoing questions about how to ethically meet conservation goals given that protected areas can in some circumstances restrict the land use rights of Indigenous and/or vulnerable peoples.

In order to have any chance of achieving the 30 × 30 goal, particularly in a just and equitable way, it is almost certain that expansions to the conservation area estate will have to include ‘other effective area-based conservation measures’ (OECMs). These are areas that provide de facto benefits to biodiversity but where conservation is not necessarily the primary management objective; they can include Indigenous lands, coastal areas managed by artisanal fisheries, and even some military installations1,6,7,8. OECMs were introduced as a conservation strategy in 2010 within the Aichi Biodiversity Targets – global conservation goals established by the Convention on Biological Diversity. Few nations, however, incorporated OECMs into conservation area networks initially, likely due to the vague definitions of OECMs. To provide direction on how OECMs could help countries meet global conservation targets, an official definition was adopted in 2018, as “a geographically defined area other than a Protected Area (PA), which is governed and managed in ways that achieve positive and sustained long-term outcomes for the in situ conservation of biodiversity, with associated ecosystem functions and services and where applicable, cultural, spiritual, socio–economic, and other locally relevant values”9. Currently there are 693 OECMs in 9 countries reported in the World Database on Protected Areas10. But legislation around the declaration and recognition of OECMs is not always clear and varies widely among and within countries. Thus, despite their name, the ‘effectiveness’ of OECMs at protecting biodiversity is unclear.

OECMs are anticipated to provide a number of benefits to global conservation. First, they could have high conservation value by protecting important biodiversity areas, particularly those that are not well represented in existing protected areas8,11. The locations of protected areas are known to be biased towards (i.e., disproportionately found in) remote, often high-elevation places, as these areas have low economic opportunity costs12,13. Partly because of this, protected areas designated over the last decade have provided little improvement to the coverage of important ecosystems or the ranges of threatened taxa14. OECMs could therefore complement protected areas, enhancing the conservation of many additional taxa, ecosystems, and ecosystem services11,14, particularly in areas where designating PAs is not socioeconomically or politically feasible. In Australia, for example, Indigenous lands that meet the criteria for OECMs overlap the ranges of three quarters of threatened vertebrate species15, equivalent to the species range overlap with protected areas16. In another study across 10 nations, sites that met some or all OECM criteria overlapped with 77% of key biodiversity areas that are currently unprotected17, indicating the strong potential of OECMs to provide complementary conservation benefits to those of protected areas.

A second major benefit of OECMs is that they are intended to be integrated into the broader conservation landscape by enhancing connectivity (e.g., the movement of organisms) among existing protected areas11. Landscape connectivity is important for ensuring gene flow18,19, species movements in response to climate change20, and long-term population persistence21,22. While the Global Biodiversity Framework stipulates that protected area networks must be “well-connected”1, in most countries network connectivity remains poor23,24,25.

Given that OECMs are still a relatively new area-based conservation tool, evidence of whether they will be able to achieve these positive biodiversity outcomes is needed. As with traditional protected areas, OECMs risk being predominantly located in areas with low opportunity costs that are not necessarily important for biodiversity or that fail to protect a representative sample of national or regional biodiversity26. This could cause the 30 × 30 agenda to fail in that, if national governments achieve 30% conservation area coverage via suites of OECMs that provide few biodiversity benefits, there could be no remaining incentive to protect the areas that do matter11,27. Moreover, and again like protected areas28,29,30, underfunded or poorly managed OECMs could be ineffective at achieving positive conservation outcomes. Assessing OECM locations and contributions to national-level conservation in light of different objectives, governance, and management is a major recognized challenge11. In sum, an evidence base for the conservation effectiveness of OECMs is critically needed7,31,32.

Here we quantify the conservation benefits of OECMs to assess their contribution to biodiversity conservation in the three high-biodiversity countries where they have been extensively trialed to-date in terrestrial (Colombia, South Africa) and marine (the Philippines) ecosystems (Fig. 1). We do not include countries where only small-scale OECMs have been implemented or where they have not yet been included in the World Database of Protected Areas10. While there are also relatively large OECMs in a few low-biodiversity locations such as Algeria and boreal Canada10, and these may well be important for local biodiversity and cultural considerations, we do not include them because these areas contribute much less to global biodiversity conservation—the overarching justification for the Global Biodiversity Framework.

Other effective area-based conservation measure’ (OECM) locations in Colombia (A), the Philippines (B), and South Africa (C). OECMs are terrestrial (A, C) or marine (B); protected areas (PAs) and Key Biodiversity Areas (KBAs) also shown. The background shows ‘raw’ (i.e., not normalized) landscape connectivity based on predicted animal movements among protected areas (A, C) or coral larval connectivity36 (B), both scaled from 1 (lowest) to 100.

To quantify the importance of OECMs to biodiversity, we address two specific objectives. First, we evaluate whether OECMs are situated in areas that are important for biodiversity and ecosystem services, including (i) threatened species ranges, ecosystem carbon, and water quality regulation26,33, (ii) areas that provide high connectivity between existing protected areas1,25, and (iii) Key Biodiversity Areas (KBAs), sites identified as important for global biodiversity persistence based on threatened biodiversity, geographically restricted biodiversity, ecological integrity, biological processes, or irreplaceability34. Second, we assess whether OECM designation reduced rates of forest loss, an indicator of effective forest management, in Colombia and South Africa. Overall, these assessments are intended to inform the further deployment of OECMs towards global conservation objectives such as 30 × 30.

Results

OECM locations relative to key areas for biodiversity and ecosystem services

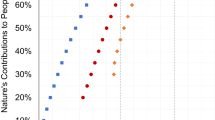

To address objective 1, we first determined whether OECMs were situated in locations important for biodiversity, ecosystem services, and landscape connectivity. First, we used systematic conservation planning to examine if OECMs encompassed the most important terrestrial areas (Colombia and South Africa) for threatened species ranges, ecosystem carbon, and water quality regulation33; and the most important marine areas (the Philippines) for biodiversity, fisheries yield, and marine carbon35. Locations within OECMs in Colombia had somewhat (2.7%) lower conservation importance, based on prioritization rankings from a priori systematic conservation planning, than paired unprotected locations (β = −0.03; p < 0.001; Fig. 2). In the Philippines, OECMs and paired unprotected locations did not differ statistically (β = 0.15; p = 0.324). In South Africa, OECMs were in areas with 14.7% higher conservation importance (β = 0.14; p < 0.001; Fig. 2) than paired unprotected locations. In Colombia and the Philippines, OECMs did a somewhat poor job of overlapping with areas identified as high conservation priority outside protected areas. Of the most important areas for conservation in each country outside of protected areas—those in the top 25% of conservation rankings—4.4% (Colombia), 0.0% (Philippines), and 11.1% (South Africa) were in OECMs. Of the total OECM estate, 11.1% (Colombia), 0.0% (Philippines), and 43.5% (South Africa) overlapped this set of the most important conservation areas. Compared to recently designated protected areas, recently designated OECMs were, on average, in areas with 36.7% lower conservation ranking in Colombia (β = −0.49; p < 0.001) and 27.6% higher conservation ranking in South Africa (β = 0.234; p < 0.001; Figure S1).

Coverage by ‘other effective area-based conservation measures’ (OECMs) of areas important for strategic conservation from a priori systematic prioritization (A–C), landscape or seascape connectivity (D–F), and Key Biodiversity Areas (KBAs; G–I) shown for Colombia (A, D, G), the Philippines (B, E, H), and South Africa (C, F, I). Connectivity and conservation importance are scaled from 1 (lowest) – 100. Boxes and error bars show means and 95% CIs, respectively, from two-tailed linear models. Sample sizes (N) show the number of biological replicates (grid cells).

OECM status was negligibly (Colombia and South Africa) or negatively (the Philippines) related to landscape and seascape connectivity—the areas predicted to be preferentially used for dispersal by organisms moving among existing protected areas. Mean landscape connectivity values, as estimated from circuit theoretic dispersal models (see Methods), were 0.3% lower than in paired unprotected locations in Colombia (β = −0.003; p < 0.001) and 2.6% higher in OECMs than in unprotected locations in South Africa (β = 0.026; p < 0.001) (Fig. 2). In the Philippines, marine OECMs were in areas with 34.9% lower estimated coral larval connectivity36 than paired unprotected areas (β = −5.10; p < 0.001; Fig. 2). This indicates that OECMs in all three countries were not strategically located in areas that meaningfully enhanced landscape or seascape connectivity among protected areas.

Terrestrial OECM status as a binary predictor variable was positively related to inclusion in a KBA in logistic models for Colombia (Δ\(\bar{x}\) = 31.4% higher mean overlap with KBAs; β = 0.277; p < 0.001; Fig. 2) and South Africa (Δ\(\bar{x}\) = 154.0%; β = 1.12; p < 0.001). This demonstrates that OECMs were more likely than paired unprotected locations to be within KBAs. However, the effect size (the contribution of OECMs to KBA protection) was relatively small; only 18.4% (Colombia) and 15.2% (South Africa) of KBA land outside of protected areas was in OECMs, while 5.1% (Colombia) and 22.7% (South Africa) of OECM land overlapped with KBAs. Marine KBA area in the Philippines was concentrated in the far north of the country (Fig. 1), overlapping very little with either OECMs or protected areas. As a result, only 3.0% of marine KBA area outside of protected areas was in OECMs, while 1.0% of marine OECM area overlapped with KBAs; marine OECM locations overlapped less than paired unprotected locations with KBAs (Δ\(\bar{x}\) = −73.9%; β = −1.36; p < 0.001; Fig. 2).

OECM effectiveness at reducing forest loss

To address objective 2, we assessed the effectiveness of OECMs at reducing forest loss in Colombia and South Africa relative to paired unprotected and protected areas. Across Colombia, national average annual deforestation rates per square kilometer ranged from 0 − 14%. In areas where OECMs were designated, local deforestation rates decreased from 4.4% per year ( ± 7.2% [SE]) pre-designation to 0.9% ( ± 7.2%) after designation (a 79.2% decline in local deforestation rate; β = −0.75; p < 0.001; Fig. 3C). Deforestation in OECMs after designation was 36.9% lower than in paired unprotected locations (β = −0.20; p < 0.001; Fig. 3A) but remained higher than in paired protected areas (post-designation; average deforestation rate = 0.3 ± 0.3% per year; β = 0.86; p < 0.001; Fig. 3B). In Colombia, OECM designation was associated with a substantial decline in deforestation—from 4.4% per year before designation to 0.9% per year after designation (a 79.2% decline; β = −0.75; p < 0.001; Fig. 3C). While this post-designation rate remained higher than that in protected areas (0.3% per year), the absolute difference was modest (Fig. 3). In South Africa, OECM effect sizes were negligible; deforestation rates changed from 0.02% per year ( ± 7.1%) both before and after OECM designation. Likewise, average deforestation rates remained slightly higher than in paired unprotected locations (0.012 ± 3.2%) and paired protected areas (average annual deforestation rate = 0.009 ± 3.2%; Fig. 3D-F).

Annual forest cover loss in ‘other effective area-based conservation measures’ (OECMs), post-designation, in Colombia (A–C) and South Africa (D–F) compared to unprotected locations (A, D), protected areas (B, E), and OECMs before designation (C, F). Boxes and error bars show means and 95% CIs, respectively, from two-tailed linear models. Sample sizes (N) show the number of biological replicates (grid cells).

Discussion

Globally, designation of OECMs may be the only way that many countries can reach their 30 × 30 commitments of enhancing both the coverage of conservation areas and the connectivity among them; as such, the strategy holds great promise for slowing the extinction crisis in ways that may be more flexible and equitable than some common types of protected areas. However, our assessment suggests that the performance of OECMs to date has been mixed—relatively weak in Colombia and the Philippines, and more promising, though still limited, in South Africa. In terms of location, OECMs in Colombia were disproportionately in areas that a priori systematic planning determined to be less important to the conservation of species and two key ecosystem services: ecosystem carbon storage and water quality regulation. Philippine marine OECMs were statistically indistinguishable from unprotected areas in their overlap of important conservation areas. South African OECMs were in better locations, with a bias towards protecting important conservation areas. OECMs in all three countries were poor at protecting regional connectivity; while South African OECMs were in areas with slightly higher connectivity than unprotected areas, we interpreted the small magnitude (2.6%) as unlikely to represent a biologically meaningful enhancement in connectivity. However, OECMs in South Africa and Colombia (but not the Philippines) had improved coverage of KBAs. These findings build in some interesting ways on those of Donald et al.17, who found that unprotected KBAs had a high overlap with potential OECM locations (i.e., areas that met the OECM criteria but which had not been designated) in the Philippines but not South Africa. The discrepancy between their findings and ours is consistent with bias in the designation of OECMs such that the choice of which potential OECM sites to officially designate led to overlap with KBAs that was disproportionately high in South Africa and disproportionately low in the Philippines. These results suggest that OECM performance is context-dependent and influenced by national-level implementation approaches. OECMs in South Africa tended to be better aligned with key biodiversity and connectivity priorities, potentially suggesting stronger strategic integration or more mature processes for identification and reporting. In contrast, Colombia and the Philippines showed more limited alignment, potentially reflecting earlier-stage or more locally driven OECM recognition processes. That said, deforestation rates in Colombian OECMs dropped substantially following designation; while these rates remained higher than in protected areas in relative terms, the absolute differences were small, suggesting that OECMs may still offer meaningful conservation benefits, particularly in landscapes where establishing traditional PAs may be less feasible.

While our analyses provide important early insights into the performance of OECMs, several limitations should be acknowledged. First, our evaluation of OECM placement relies on overlap with global spatial datasets of conservation priorities (e.g., KBAs, systematic conservation planning outputs), which are necessarily coarse and may not fully capture locally or nationally relevant biodiversity values. It is possible that additional or alternative data—such as national species occurrence records, local ecological knowledge, or cultural values—were used in the designation of OECMs but are not represented in the global datasets we analyzed. Thus, our finding that many OECMs do not strongly overlap with global priority areas could reflect either (1) a true mismatch between OECM locations and high-priority conservation sites, or (2) limitations in the scope or resolution of the global datasets used. This ambiguity highlights the importance of improving transparency and data-sharing around the criteria and evidence used to designate OECMs, as well as the need for locally grounded assessments that complement global analyses like ours.

A greater emphasis on strategic deployment and management of OECMs could dramatically improve their conservation outcomes. Currently, the identification and declaration of OECMs in many countries is driven by which local entities decide to apply for OECM status and can meet the planning and reporting criteria6. Indeed, it is fairly common in conservation to have goals focused on biodiversity at regional or global scales1 but management decisions that are made at national or more local scales6. But having OECM designation be entirely locally driven may lead to opportunistic OECM networks that are not based on unified strategies at the state, national, or international scale. This approach creates a risk, consistent with our results, that OECMs could be used for reaching international targets without delivering meaningful conservation gains. Jurisdictional guidance in OECM deployment, while incorporating and respecting local objectives, knowledge, and management capacities, could help ensure that OECMs are ecologically representative, thereby helping rectify the biases in the locations of existing protected areas14,26. Such policy could also focus the deployment of new OECMs towards the most important areas for conservation33,35 and the enhancement of connectivity20,22 – a key goal of the Global Biodiversity Framework1. At broader scales, international coordination, for example through the IUCN World Commission on Protected Areas, could help achieve global standardization that still allows for tailoring to particular regional contexts11. A hierarchical approach incorporating global guidelines, state or national strategies, and local tailoring may generate additional buy-in of the OECM concept on the part of jurisdictions in developing countries, particularly if co-benefits (e.g., based on marketable forest carbon37,38) can be realized.

As a caveat to our findings on the performance of OECMs, we note that OECMs (as with protected areas, connectivity, and many other spatial conservation features) are often treated as static entities rather than dynamic parts of changing landscapes or seascapes. This is important because, while our analysis suggests that OECM designation currently provides mixed benefits for conservation, these benefits could increase over time39 and gains in biodiversity conservation may lag several years behind OECM designation40. Habitats and species in deforested or defaunated OECMs can recover through natural regeneration and ecological restoration41 such that the OECMs could eventually be designated as KBAs, achieve high conservation prioritization rankings, and meaningfully enhance regional connectivity. But all of that said, the long-term benefits of OECMs for biodiversity are still likely to be substantially enhanced by using a strategic planning process to assist in the choosing of their locations.

Important ways to build on our assessment of OECM effectiveness at broad spatial scales include developing a better understanding of how different types of OECMs, management practices, and anthropogenic impacts affect conservation outcomes. OECMs encompass a wide variety of land uses and governance structures, from Indigenous lands to military installations, whose different management practices could dramatically influence biodiversity17. Additionally, in our study we did not know the conservation status of OECMs prior to their designation; if OECMs had existing protections prior to designation, this would limit our ability to detect a relationship between OECM designation and conservation outcomes (e.g., deforestation trajectories). We also note that our measures of forest loss include timber harvest and agricultural expansion along with the effects of fire, which can be ‘natural’ or anthropogenic in origin and which are exacerbated by climate change – indeed, increases in fire frequency and extent are a primary threat to forest ecosystems42,43. Finally, it will also be important to assess the effectiveness of OECMs in a landscape context; for example, larger or better-connected OECMs may have disproportionate benefits for biodiversity, as has been suggested with protected areas4.

In conclusion, despite their potential to be an effective area-based conservation tool to complement protected areas, we find that OECMs provide mixed conservation benefits. By definition, OECMs have other goals besides conservation, for example leveraging the protection and knowledge of local communities, although currently <2% of OECMs globally are locally governed8. While we should not solely rely on OECMs to fill gaps in biodiversity coverage in the existing protected area network, they could contribute importantly to global conservation if deployed more strategically. OECMs may achieve the desired outcome of slowing biodiversity loss if placed in areas of maximum conservation value, with capacity for long-term monitoring, management, and trust-building with stakeholders.

Methods

Statistics and reproducibility

Our first objective was to investigate whether OECMs are located in areas with high potential to protect biodiversity. As with protected areas26, the locations of OECMs might be chosen to minimize opportunity costs, such that they are biased towards areas that are “high and far”12. In our analyses, this could lead to elevation and human disturbance being associated with both OECM location (i.e., the predictor variable) as well as measures of OECM effectiveness (e.g., forest loss; response variables described further below). Therefore we de-confounded the effects of elevation and human disturbance by including the covariates in terrestrial analyses and also by using propensity score-matching44 to facilitate the testing of relationships between OECM status and key variables of interest while balancing the sets of confounding and other covariates. Specifically, we paired landscape pixels (1 km2 in most analyses; see below) in OECMs with corresponding pixels either in protected areas or ‘unprotected’ parts of the landscape (i.e., outside of both protected areas and OECMs) by matching based on elevation, easting, northing, and the Human Footprint Index (HFI; log10-transformed) – a composite metric of the cumulative human impacts on the environment based on human population density, agriculture, and a variety of infrastructures45. Overall, matching allowed us to compare OECM locations with either paired protected or unprotected locations that were similar in elevation and human disturbance, and as close as possible in Euclidean distance. The goal of this matching was to be able to compare effects of OECMs on biodiversity by controlling for other factors (besides OECM designation) that could affect biodiversity. Some residual imbalance remained after matching in Colombia and South Africa, particularly for HFI (Table S1). Nevertheless, matching was generally effective, helping to balance the covariate sets and reduce potential bias in the subsequent analyses.

We used OECM and protected area locations from the World Database on Protected Areas (May 2023 version)10 (see main text Table 1); following Hanson46, we restricted the sites to those with a status of “Designated”, “Inscribed”, or “Established” and a ‘GIS_area’ > 0. We used propensity score matching to pair 1 km2 landscape pixels inside OECMs with unprotected pixels in order to strive for balanced covariate sets. Using the package MatchIt47 in R48, we used nearest-neighbor matching with a logit link function to match OECM and unprotected pixels based on northing, easting, elevation, and human disturbance as measured by the HFI (log10-transformed)45. For the Philippines, we matched data based on northing, easting, and ocean depth49.

We evaluated whether OECMs were situated in the most effective areas for biodiversity conservation (objective 1) by comparing them against unprotected locations in terms of (i) the most important conservation areas as determined by systematic conservation planning, (ii) landscape or seascape connectivity, and (iii) coverage of KBAs. First, we assessed OECM contributions to strategic biodiversity conservation by comparing them to unprotected locations in terms of coverage of the most important areas for global conservation in each country as determined by a priori systematic conservation planning. We used an existing conservation prioritization assessment for terrestrial areas from Jung et al.33. This ranked 10-km grid cells in terms of their contribution to protecting species ranges, ecosystem carbon, and water quality regulation – this combination of features addresses the Global Biodiversity Framework’s stipulation that new conservation areas should be situated in important areas for biodiversity as well as ecological functions and ecosystem services that benefit humanity26. For the Philippines, we used a global map of the most important areas for marine biodiversity from Sala et al.35. This ranked 50-km grid cells from 0 to 1 in terms of species extinction risk, habitat suitability, and ecological distinctiveness. To standardize between these metrics, we rescaled both conservation prioritization maps to a 1 [lowest priority] − 100 [highest priority] scale. These prioritizations did not have protected areas ‘locked in’ (i.e. automatically included in the prioritization process as already protected and assumed that these cannot be changed) to avoid also locking in OECMs. We aggregated the OECM data to the 10 km for Colombia and South Africa, 50 km for the Philippines, using bilinear interpolation. In the Philippines, where marine OECMs were mostly nearshore, we restricted the analysis to areas less than or equal to the maximum depth of OECMs in that country (1671 m), to avoid comparing shallow-water OECMs to deep-water unprotected locations. We used Poisson linear regressions to test whether conservation importance (integer scale: 1-100) was associated with OECM status (binary).

We also repeated this analysis for recently designated (i.e., post-2014) OECMs and protected areas in terms of their coverage of high conservation values areas. If recently designated OECMs and protected areas were both sub-optimally located for conservation, then the problem would not necessarily be with OECMs per se, but with recent conservation site-selection in general. We could not do this analysis for the Philippines because we were unable to find data on OECM establishment year for this country. We could not perform such comparisons for connectivity because we were explicitly measuring connectivity as organismal movement among protected areas, as per Brennan et al.25. Likewise, we could not make similar comparisons for KBAs because the boundaries of KBAs are sometimes explicitly set to match those of protected areas34, making comparisons between protected areas and OECMs with respect to KBAs potentially circular.

We assessed landscape connectivity in Colombia and South Africa by using circuit theory algorithms to map the locations and rates of movement between existing protected areas within each country. Our analysis follows the connectivity mapping framework of Brennan et al.25 but at a finer spatial scale. There are many other approaches to mapping connectivity e.g.24,50,51, but most of these assess structural connectivity (i.e. the contiguity of habitats such as forest) whereas we were interested in functional connectivity (i.e. where and to what degree organisms actually move across the landscape). Indeed, determining how to measure the “well-connected” stipulation of the Global Biodiversity Framework remains poorly defined22. We included a 100 km buffer around countries to account for sites that could have appeared isolated within a nation but were actually well-connected to protected areas across an international border. We followed Brennan et al.25 by assessing connectivity for a model wide-ranging species: a 74 kg herbivore. Following Tucker et al.52, we calculated landscape resistance as a function of the HFI and normalized difference vegetation index (scaled from 0 − 1)53. We used model coefficients from Tucker et al.52 to calculate movement distances over 10-day (256 hour) timeframes using 95% quantiles, as per Brennan et al.25. We calculated resistance as the complement of scaled (from 0−1) 10-day movements. We modeled connectivity between protected areas using the samc package54, which applies spatial absorbing Markov chains to simulate connectivity in response to landscape resistance and animal mortality. In each of 5000 timesteps, an animal was simulated to take one step from their starting location to one of the four neighboring cells; the direction of movement was semi-random and influenced by the relative resistance of each path. Individuals originated in protected areas, and each map pixel within a protected area contributed one disperser (such that larger areas contributed more dispersers). Individuals continued to disperse until either they died in transit and were “absorbed” into the landscape (with absorption rates equal to scaled, log10-transformed HFI), they settled in an existing protected area (arbitrarily set to 50% settlement rate per timestep), or 5000 timesteps passed. Connectivity was then calculated as the summed distribution of paths taken by all dispersing individuals. As the metric of connectivity, we calculated normalized current flow (the sum of movement paths divided by the result of an analogous simulation but with landscape resistance set to 0), where pixels with values below 1 have anthropogenic barriers impeding connectivity, values above 1 indicating that barriers are channeling dispersers into narrow pinch-points (such that movement values are higher than expected), and values similar to one have unimpeded connectivity55. As a measure of seascape connectivity for the Philippines, we used an existing map of coral larval dispersal from Pata and Yñiguez36.

We followed Donald et al.17 in assessing OECM overlap with KBAs, which integrate taxonomic diversity, ecoregions, and ecological integrity to identify areas that are disproportionately important for conservation. We obtained maps of KBAs in the three countries from BirdLife International56 and note that KBAs sometimes share boundaries with existing protected areas (Fig. 1)34. For each country, we ascertained whether OECMs overlapped more than paired unprotected locations with either high-connectivity areas or KBAs using linear models with propensity score-matched data. Specifically, we used logistic models parameterized with the matched data to assess whether, for 1 km2 cells (sampling units), KBA status (binary response variable) was associated with OECM status (binary), additionally including elevation (or ocean depth, for the Philippines) and the log-transformed Human Footprint Index (Colombia and South Africa only) as covariates. Models to assess connectivity were similar except that the response variable, connectivity, was continuous (instead of binary) and had an identity? (rather than logit) link function. In the models to address all three components of objective 1, we included first- and second-order polynomials of latitude and longitude in analyses to account for spatial autocorrelation, though noting that coefficients from regression analysis of gridded geographical data tend to be statistically robust to bias from spatial autocorrelation57,58.

To address objective 2, determining the effectiveness of OECMs at reducing deforestation in Colombia and South Africa, we used linear models on propensity score-matched data to compare average annual rates of forest cover loss from 2001 to 2022 in OECM locations (restricted to time periods after each OECM’s designation) to those in paired protected areas (restricted to post- designation) and unprotected locations. We also measured rates of forest loss in OECMs before versus after their legal designation, acknowledging that conservation status prior to OECM designation was unknown and some areas could have had forms of protection in place before OECM designation. We only analyzed data for landscape pixels with ≥5 years of data both before and after OECM designation – this excludes OECMs designated before 2006 or after 2017 because they would not have sufficient before- and after-designation data. We could not use before-after-control-impact or difference-in-differences approaches for this analysis because the treatment (i.e., OECM designation) occurred at different times for each jurisdiction, making it impossible to specify a “before” versus “after” treatment designation for the control data (i.e., unprotected sites). We did not apply buffers around (or within) OECMs because leakage and edge effects are key factors that could affect the ability of OECMs (or PAs) to support biodiversity, so we did not want to control for (and therefore statistically eliminate) these effects.

Annual forest change data came from Hansen et al.59 (data updated to 2022) with “forest” defined as areas having ≥30% tree cover in the year 2000, which is the forest threshold definition in Colombia60. Hansen et al.59 defined forest loss as “… a stand-replacement disturbance, or a change from a forest to non-forest state”, which can include disturbances such as fire and logging. For the comparisons between OECMs and either protected areas or unprotected locations, we again used propensity score matching to balance the covariate sets. Specifically, we matched OECM locations with either protected or unprotected locations that were as similar as possible in elevation, HFI, northing, and easting. Annual forest loss data were log10-transformed for the analyses to improve normality of residuals.

Reporting summary

Further information on research design is available in the Nature Portfolio Reporting Summary linked to this article.

Data availability

Data used in this study have been deposited in the figshare database at https://doi.org/10.6084/m9.figshare.29661356.v1.

Code availability

Google Earth Engine code to determine annual forest loss in Colombia and South Africa is available at https://code.earthengine.google.com/1cbc484a4f2137a7faaf49b7e3c42dc5. Code in the R programming language for the other analyses has been deposited in the Zenodo database at https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.16051529.

References

UN-CBD. Kunming-Montreal Global Biodiversity Framework. (United Nations Convention on Biological Diversity; Fifteenth Meeting of the Conference of the Parties, 2022).

Laurance, W. F. et al. Averting biodiversity collapse in tropical forest protected areas. Nature 489, 290–294 (2012).

Le Saout, S. et al. Protected areas and effective biodiversity conservation. Science 342, 803–805 (2013).

Brodie, J. F. et al. Landscape-scale benefits of protected areas for tropical biodiversity. Nature 620, 807–812 (2023).

Hirsch, T., Mooney, K. & Cooper, D. Global Biodiversity Outlook 5. (Secretariat of the Convention on Biological Diversity, 2020).

Gurney, G. G. et al. Biodiversity needs every tool in the box: use OECMs. Nature 595, 646–649 (2021).

Maini, B., Blythe, J. L., Darling, E. S. & Gurney, G. G. Charting the value and limits of other effective conservation measures (OECMs) for marine conservation: A Delphi study. Mar. Policy 147, 105350 (2023).

Jonas, H. D. et al. Global status and emerging contribution of other effective area-based conservation measures (OECMs) towards the ‘30x30’biodiversity Target 3. Front. Conserv. Sci. 5, 1447434 (2024).

CBD. Decision Adopted by the Conference of the Parties to the Convention on Biological Diversity (CBD) 14/8. Protected areas and other effective area-based conservation measures. (2018).

UNEP-WCMC & IUCN. Protected Planet: The World Database on Protected Areas (WDPA). (United Nations Environment Programme - World Conservation Monitoring Centre and International Union for the Conservation of Nature; www.protectedplanet.net (accessed 1 Oct 2023), 2023).

Alves-Pinto, H. et al. Opportunities and challenges of other effective area-based conservation measures (OECMs) for biodiversity conservation. Perspect. Ecol. Conserv. 19, 115–120 (2021).

Joppa, L. N. & Pfaff, A. High and far: biases in the location of protected areas. PloS one 4 (2009).

Nelson, A. & Chomitz, K. M. Effectiveness of strict vs. multiple use protected areas in reducing tropical forest fires: a global analysis using matching methods. PloS one 6, e22722 (2011).

Maxwell, S. L. et al. Area-based conservation in the twenty-first century. Nature 586, 217–227 (2020).

Renwick, A. R. et al. Mapping Indigenous land management for threatened species conservation: An Australian case-study. PloS one 12, e0173876 (2017).

Schuster, R., Germain, R. R., Bennett, J. R., Reo, N. J. & Arcese, P. Vertebrate biodiversity on indigenous-managed lands in Australia, Brazil, and Canada equals that in protected areas. Environ. Sci. Policy 101, 1–6 (2019).

Donald, P. F. et al. The prevalence, characteristics and effectiveness of Aichi Target 11′ s “other effective area-based conservation measures”(OECMs) in Key Biodiversity Areas. Conserv. Lett. 12, e12659 (2019).

Kling, M. M. & Ackerly, D. D. Global wind patterns shape genetic differentiation, asymmetric gene flow, and genetic diversity in trees. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. 118, e2017317118 (2021).

Savary, P., Foltête, J. C., Moal, H., Vuidel, G. & Garnier, S. Analysing landscape effects on dispersal networks and gene flow with genetic graphs. Mol. Ecol. Resour. 21, 1167–1185 (2021).

Williams, S. H. et al. Incorporating connectivity into conservation planning for the optimal representation of multiple species and ecosystem services. Conserv. Biol. 34, 934–942 (2020).

Brodie, J. F., Mohd-Azlan, J. & Schnell, J. K. How individual links affect network stability in a large-scale, heterogeneous metacommunity. Ecology 97, 1658–1667 (2016).

Brodie, J. et al. A well-connected Earth: the science and conservation of organismal movement. Science In Press (2025).

Parks, S. A., Holsinger, L. M., Abatzoglou, J. T., Littlefield, C. E. & Zeller, K. A. Protected areas not likely to serve as steppingstones for species undergoing climate-induced range shifts. Glob. Change Biol. 29, 2681–2696 (2023).

Ward, M. et al. Just ten percent of the global terrestrial protected area network is structurally connected via intact land. Nat. Commun. 11, 4563 (2020).

Brennan, A. et al. Functional connectivity of the world’s protected areas. Science 376, 1101–1104 (2022).

Watson, J. E. et al. Priorities for protected area expansion so nations can meet their Kunming-Montreal Global Biodiversity Framework commitments. Integr. Conserv. (2023).

Giglio, V. J. et al. Large and remote marine protected areas in the South Atlantic Ocean are flawed and raise concerns: Comments on Soares and Lucas (2018). Mar. Policy 96, 13–17 (2018).

Leverington, F., Costa, K. L., Pavese, H., Lisle, A. & Hockings, M. A global analysis of protected area management effectiveness. Environ. Manag. 46, 685–698 (2010).

Nolte, C., Agrawal, A., Silvius, K. M. & Soares-Filho, B. S. Governance regime and location influence avoided deforestation success of protected areas in the Brazilian Amazon. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. 110, 4956–4961 (2013).

Benitez-Lopez, A. et al. The impact of hunting on tropical mammal and bird populations. Science 356, 180–183 (2017).

Cook, C. N. Progress developing the concept of other effective area-based conservation measures. Cons. Biol. (2023).

IUCN-WCPA. Recognising and Reporting Other Effective Area-Based Conservation Measures. (International Union for the Conservation of Nature (IUCN) - World Congress on Protected Areas (WCPA) Task Force on OECMs, 2019).

Jung, M. et al. Areas of global importance for conserving terrestrial biodiversity, carbon and water. Nat. Ecol. Evolution 5, 1499–1509 (2021).

IUCN. A global standard for the identification of Key Biodiversity Areas, version 1.0. First edition. (International Union for the Conservation of Nature, 2016).

Sala, E. et al. Protecting the global ocean for biodiversity, food and climate. Nature 592, 397–402 (2021).

Pata, P. R. & Yñiguez, A. T. Spatial planning insights for Philippine coral reef conservation using larval connectivity networks. Front. Mar. Sci. 8, 719691 (2021).

Duncanson, L. et al. The effectiveness of global protected areas for climate change mitigation. Nat. Commun. 14, 2908 (2023).

Jantz, P., Goetz, S. & Laporte, N. Carbon stock corridors to mitigate climate change and promote biodiversity in the tropics. Nat. Clim. Change 4, 138–142 (2014).

Curran, M., Hellweg, S. & Beck, J. Is there any empirical support for biodiversity offset policy?. Ecol. Appl. 24, 617–632 (2014).

Adams, V. M., Setterfield, S. A., Douglas, M. M., Kennard, M. J. & Ferdinands, K. Measuring benefits of protected area management: trends across realms and research gaps for freshwater systems. Philos. Trans. R. Soc. B: Biol. Sci. 370, 20140274 (2015).

Rodrigues, R. R., Lima, R. A., Gandolfi, S. & Nave, A. G. On the restoration of high diversity forests: 30 years of experience in the Brazilian Atlantic Forest. Biol. Conserv. 142, 1242–1251 (2009).

Brodie, J., Post, E. & Laurance, W. F. Climate change and tropical biodiversity: a new focus. Trends Ecol. evolution 27, 145–150 (2012).

Anderegg, W. R. et al. Climate-driven risks to the climate mitigation potential of forests. Science 368, eaaz7005 (2020).

Schleicher, J. et al. Statistical matching for conservation science. Conserv. Biol. 34, 538–549 (2020).

Venter, O. et al. Sixteen years of change in the global terrestrial human footprint and implications for biodiversity conservation. Nat. Commun. 7, 12558 (2016).

Hanson, J. O. Wdpar: Interface to the world database on protected areas. J. Open Source Softw. 7, 4594 (2022).

Stuart, E. A., King, G., Imai, K. & Ho, D. MatchIt: nonparametric preprocessing for parametric causal inference. Journal of statistical software, (2011).

R Core Team. R: A language and environment for statistical computing. (R Foundation for Statistical Computing, 2023).

GEBCO. The General Bathymetric Chart of the Oceans (GEBCO) 2023 Grid (https://doi.org/10.5285/f98b053b-0cbc-6c23-e053-6c86abc0af7b) {accessed 20 Oct 2023). (GEBCO Compilation Group, 2023).

Beyer, H. L., Venter, O., Grantham, H. S. & Watson, J. E. Substantial losses in ecoregion intactness highlight urgency of globally coordinated action. Conserv. Lett. 13, e12692 (2020).

Theobald, D. M., Keeley, A. T., Laur, A. & Tabor, G. A simple and practical measure of the connectivity of protected area networks: The ProNet metric. Conserv. Sci. Pract. 4, e12823 (2022).

Tucker, M. A. et al. Moving in the Anthropocene: Global reductions in terrestrial mammalian movements. Science 359, 466–469 (2018).

Copernicus Service Information. Global land service; https://land.copernicus.eu/en (accessed 1 Aug 2023). (2023).

Marx, A. J., Wang, C., Sefair, J. A., Acevedo, M. A. & Fletcher, R. J. Jr. samc: an R package for connectivity modeling with spatial absorbing Markov chains. Ecography 43, 518–527 (2020).

McRae, B. et al. Conserving nature’s stage: mapping omnidirectional connectivity for resilient terrestrial landscapes in the Pacific Northwest. (The Nature Conservancy, 2016).

BirdLife International. World Database of Key Biodiversity Areas. (Developed by the KBA Partnership: BirdLife International, International Union for the Conservation of Nature, American Bird Conservancy, Amphibian Survival Alliance, Conservation International, Critical Ecosystem Partnership Fund, Global Environment Facility, Re:wild, NatureServe, Rainforest Trust, Royal Society for the Protection of Birds, Wildlife Conservation Society and World Wildlife Fund. September 2023 version. Available at http://keybiodiversityareas.org/kba-data/request (accessed 25 Oct 2023).

Hawkins, B. A. Vol. 39 1–9 (Wiley Online Library, 2012).

Hawkins, B. A., Diniz-Filho, J. A. F., Mauricio Bini, L., De Marco, P. & Blackburn, T. M. Red herrings revisited: spatial autocorrelation and parameter estimation in geographical ecology. Ecography 30, 375–384 (2007).

Hansen, M. C. et al. High-resolution global maps of 21st-century forest cover change. science 342, 850–853 (2013).

FAO. From reference levels to results reporting: REDD+ under the UNFCCC. 2018 update. (Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations (FAO), 2018).

Acknowledgements

Support for this project was provided by Northern Arizona University, Universiti Malaysia Sarawak, University of British Columbia, University of Montana, and University of York. We thank P. Pata for providing the coral larval dispersal data.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

J.B. conceived of the project and conducted the analyses to test the study objectives. M.D. conducted the analyses to measure connectivity across Colombia and South Africa. P.B. assembled the data on forest loss in Colombia and South Africa. J.B. wrote the initial manuscript draft; M.D., P.B., S.G., C.C., J.H., G.R., and J.M.-A. contributed to writing.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors have no competing interests.

Peer review

Peer review information

Nature Communications thanks the anonymous reviewers for their contribution to the peer review of this work. A peer review file is available.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Brodie, J.F., Deith, M.C.M., Burns, P. et al. The contribution of other effective area-based conservation measures (OECMs) to protecting global biodiversity. Nat Commun 16, 7886 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-025-63205-8

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-025-63205-8