Abstract

Metal single atoms have been demonstrated to induce surface-enhanced Raman scattering (SERS) due to their effectiveness in the modification of electronic structure. However, precisely modulating the relative positions of metal single atoms on sub-nanolattices remains a formidable challenge, which makes SERS studies of metal single atoms dependent on localized environments still lacking. Herein, we rely on polyethylene glycol (PEG) as a soft template to achieve the modulation of the relative positions of W atoms on titanate nanotubes (W-TNTs) and probe the local-environment-dependent SERS induced by metal single atoms based on this technique. We find that the relative position of the W single atoms greatly affects their SERS performance. This phenomenon has been attributed to the difference in charge transfer ability between single W atoms of different configurations, with isolated W atoms inducing a significantly higher density of electronic states near the Fermi energy than associated W atoms, leading to an enhanced polarization of the probe molecule and subsequently a stronger Raman signal. Our findings demonstrate a technique to effectively control the relative positions of single atoms and provide insights into single-atom-induced SERS associated with localized environments, which will facilitate the rational design of SERS substrates based on metal single atoms.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

SERS spectroscopy is a highly sensitive analytical technique for trace detection, offering molecular structural fingerprints and significantly amplified Raman signals, even enabling single-molecule detection. It is emerging as a potential choice for state-of-the-art applications ranging from point-of-care bioanalysis to reaction intermediates tracking1,2,3,4. The surface of SERS substrate is highly critical for analyte detection since the normally weak Raman signals of a molecule can be strongly enhanced on such substrates through two well-known mechanisms: the electromagnetic mechanism (EM) and chemical mechanism (CM)5. The nanostructured plasmonic metals (e.g., Au, Ag) designed with electromagnetic “hotspots” at the tips/gaps are often employed as highly sensitive SERS substrates based on the EM enhancement6. However, the nanostructured metal substrates usually suffer from limited reproducibility, high cost, stemming from the uneven distribution of hotspots, which hinders their practical applications. As alternations, more and more plasmon-free materials (such as TiO2, W18O49, Cu2O, MOFs, etc.) have been found with SERS activities, exhibiting diverse surfaces especially valuable in sensing selectivity/specificity when compared with their metal counterpart7,8,9,10. The observed non-plasmonic SERS is mostly involved in the framework of CM, particularly regarding efficient photoinduced charge-transfer (CT) transitions, which enlarge the molecular polarizability tensor to magnify Raman-scattering cross-sections. Therefore, common strategies aiming at fluent CT transitions in the semiconductor-molecule system have also been applicable for boosting SERS activities, such as the manipulation in stoichiometry, crystallinity, and dimension that can be generally applied to the class of semiconductor materials11. However, the SERS sensitivities of most semiconductors currently are still inferior to the plasmonic ones, partially attributable to the lack of either in-depth understanding or elaborately manipulating the CT transitions on sub-nanometer-scale surfaces.

Since the Raman spectrum is related to the polarizability tensor of the probe molecule, the SERS signals are essentially determined by carrier distribution within the substrate-molecule system, particularly when considering the CT contributions. After the demonstration of single-atom catalysis in 201112, it is noteworthy that some researchers have recently modulated the surface electronic states of catalysts by altering the distribution of metal single atoms/clusters13,14,15,16,17, which has taken the understanding of single-atom catalysis a big step forward in obtaining amazing catalytic activities. The individual and isolated metal adatoms in such surface configurations act as acceptors, where the support substrate serves a role comparable to ligands in coordination chemistry. This acceptor-ligand interaction locally alters the charge carrier distribution in the underlying support15, facilitating CT between the substrate and adsorbed molecules. Consequently, these systems represent ideal platforms for investigating semiconductor-based SERS. Interestingly, the SERS enhancement may alter from EM-dominant to CM-dominant when the noble metal nanoparticles (such as Au) are smaller than a certain size (≈16–21 nm)18, and if the Au particle size is further reduced to a single-atom scale, the SERS would follow the CT mechanism due to the significantly altered electronic structure of the substrate19. Several emerging works demonstrate the potential of single-atom materials as a class of SERS substrates20,21,22,23,24,25, however, a close view of the carrier distribution at the sub-nanometer scale and the subsequent impact on SERS is yet to be disclosed.

Herein, by adopting polymer templates with varying chain lengths as sub-nanometer rulers, we realize the manipulated location of single-atom sites on the SERS substrate. Titanate nanotubes (TNTs) exposing a single lattice plane (020) are employed as supports, on which W single atoms resident as isolated or correlated sites are precisely controlled by the assistance of PEG templates. The series of single-atom substrates exhibits significantly different SERS enhancements, although with approximate W loading amounts, and the optimized one with W loading of 6.2 wt.% achieves an enhancement factor (EF) of 2.25 × 108 among plasmonic-free substrates. These single-atom substrates are found with versatile SERS enhancement toward a variety of probe molecules, including methylene blue (MB), 4-mercaptobenzoic acid (4MBA), tyrosine (Tyr), cytosine (Cyt), dopamine (DP), and bisphenol A (BPA). The site-related enhancement is attributed to the varied local carrier distributions in close to the correlations of single atoms, which directly determine the CT transitions at sub-nanometer-scale interfaces. These findings provide an effective approach for manipulating the correlations of single atoms atthe sub-nanometer scale, which would further shed light on the origin of SERS enhancement regarding CT transitions.

Results

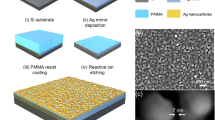

Synthesis of W-TNT composite materials

TNTs were employed as the supporting material for single atoms, which can be feasibly synthesized via an alkaline hydrothermal method26. Briefly, TiO2 powder (3.6 g) was dispersed in 50 mL of NaOH (10 M) and transferred into a 100 mL Teflon container, which was then sealed and subjected to a hydrothermal reaction at 150 °C for 20 h. After cooling to room temperature, the titanate sediment was washed with deionized water and then acidified with 0.1 M HNO3 under continuous stirring for over 24 h. The TNT product was obtained by thoroughly washing with deionized water until the pH reach 7. To realize a controllable distribution of W single atoms on the supporting TNTs, metal-organic complexes (W-PEG) were prepared as W precursors. These complexes were easily formed between Na2WO4 and PEG of varying molecular weights by mixing them in an aqueous solution at a molar ratio of 1:1. The W-PEG precursor was added dropwise into the aqueous dispersion of TNTs and stirred continuously at 75 °C for 4 h, and the solid was then centrifugated and washed successively with deionized water and ethanol until the pH approaches 7. The product was dried in a vacuum oven at 60 °C, followed by calcination under argon at 200 °C for 6 h to remove organic residues from the surface (Supplementary Fig. 1), which were recorded as the W-TNT samples (Supplementary Fig. 2).

In the fabrication process described above, the W-PEG precursor plays a crucial role in manipulating the relative positions of W single atoms on the TNT surfaces, offering an opportunity to control the isolated or correlated configurations of the single atoms. As predicted by the DFT calculations20, the W centers provided by WO42− ions would preferentially bind with the terminal oxygen groups of the PEG ligand through bidentate coordination, which is saturated with another four -OH groups to maintain the same valence state (W6+) as the parent WO42− ions (Fig. 1a). Therefore, by combining Na2WO4 with excessive PEG in a molar ratio of 1:1, the formation of the W-PEG precursor with terminal coordination configuration would be further ensured. The TNTs we select are also crucial for the controlled accommodation of W single atoms, benefiting from their unitary exposed facet (020), which is rich in -OH dangling bonds (Fig. 1b)27. Accordingly, the W head of the W-PEG can be chemically bonded on the surface of TNTs through a hydroxyl condensation reaction, while the PEG tail would tile onto the surface of TNTs as a result of hydrogen bonds formed between PEG chains and the titanate surface. As illustrated in Fig. 1d, the PEG chain then acts as a blocking agent to passive the -OH dangling bonds on TNTs surface, which prevents the accommodation of additional W-PEG precursors by the spacing relevant to the PEG chain length.

a Structural diagram of W-PEG and its adsorption on the surface of TNT via hydrogen bonding. The color scheme of the atoms in the illustration is brown (C) for carbon, red (O) for oxygen, pale pink (H) for hydrogen, and grey (W) for tungsten. Blue wavy lines are used to represent PEG. b Modeling of TNT. c Relative lengths of PEGs with different molecular weights. d Modeling of W-PEG adsorption on TNT surface. e W content of two series of W-TNT samples. f–h Using SS as a reference, SA and CS are obtained by two different strategies to regulate the loading. Source data are provided as a Source Data file.

Since PEG polymers with relatively small molecular weight ( ≤1000 g mol−1) exhibit approximately linear configurations28, five commercially available PEG products with the molecular weight of 300, 400, 600, 800, and 1000 g mol−1 were employed as ligand in this study, with chain lengths estimated to range from 1.8 to 6.25 nm, respectively (Fig. 1c). Thus, by utilizing the PEG chain as a ruler at nanoscale, the concentration, distribution, and even the spacing between W single atoms can be effectively manipulated on the lattice plane of TNTs (see Supplementary Note 1). Moreover, leveraging the molecular ruler effect, the saturated loading of W can be directly related to the chain length of PEG adopted in the W-PEG precursor (Fig. 1d–g). Figure 1g depicts a typical situation of saturated W-PEG loading, where a limited number of W heads adjacent to each other form the correlated single atoms (marked in red circles), named as single sites (SS) according to ref. 29 With different PEG chains, an alterable spacing between neighboring SS can be realized while largely maintaining the arrangement of single atoms in the scope of the SS sites (Fig. 1h). In other words, using PEGs with smaller molecular weights results in decreased spacing between neighboring SS, leading to the formation of correlated sites (CS). In contrast, when W-PEG loading is unsaturated, as shown schematically in Fig. 1f, fewer W-PEG species are distributed across the same surface area of TNTs compared to the saturated loading, resulting in increased separation between W single atoms and diminishing the formation of correlated single atoms, ultimately leading to the emergence of isolated single atoms (SA).

On the basis of above emphasis, the loading amount of W single atoms in the W-TNT composites can be precisely controlled through two methods during synthesis, namely, (1) by choosing PEG with different molecular weights and (2) by varying the W-PEG/TNT ratio. In the first series of products designed to achieve the SS configuration, the W-PEG precursor was added in excess to ensure saturated loading, with PEG molecular weights chosen as 300, 400, 600, 800, and 1000 g mol−1. These samples were labeled as W-TNT-300, W-TNT-400, W-TNT-600, W-TNT-800, and W-TNT-1000, respectively. To obtain the SA configuration, another series of samples was synthesized using PEG with a molecular weight of 600 g mol−1 as the ligand, but with varying W-PEG/TNT ratios, progressively reduced from the saturated loading (100%). These samples were labeled as 74%W-TNT-600, 54%W-TNT-600, 39%W-TNT-600, and 19%W-TNT-600. The actual W content (wt.%) for the two series of W-TNT samples was determined through inductively coupled plasma-optical emission spectroscopy (ICP-OES) analysis, with the results plotted as red and black dots for the SS and SA series, respectively. As shown in Fig. 1e, a nearly linear increase in W content can be observed along with a decreasing PEG molecular weight used in the SS series, with the ratio measured to be 8.8, 9.8, 11.4, 12.6, and 13.2 wt.% for W-TNT-1000, W-TNT-800, W-TNT-600, W-TNT-400, and W-TNT-300, respectively (Supplementary Table 1). While for the SA samples, a descending W ratio in the samples can be obtained as the portion of W-PEG precursor reduces, which are measured to be 11.4, 8.4, 6.2, 4.5, and 2.2 wt.% for the samples synthesized with the W-PEG portion of 5, 1, 0.7, 0.5, and 0.25 mL, respectively (Supplementary Table 2). Clearly, the loading of W single atoms can be effectively controlled either by precursor ratios or by the PEG chain length in the precursor in our synthesis, further validating the configuration models we proposed.

Characterizations for the W-TNT samples

The phase purity of the target products was verified by XRD analysis. As depicted in Fig. 2a, the XRD profile of TNTs exhibits two sharp diffraction peaks at 24.7° and 48°, which can be attributable to the (110) and (020) crystal planes of H2Ti3O7 (JCPDS#36-0654), underscoring the high crystallinity of the TNTs. The W-TNT-300 sample shows an almost identical XRD pattern to its parent TNT, clearly indicating that the TNT structure is preserved, with no additional crystalline phases forming during the synthesis of W-TNT composites, even in the W-TNT-300 sample with the highest W loading in the series. The multi-walled tubular morphology of the TNT materials is distinctly visible in the HR-TEM images of both the W-TNT-300 and parent TNT samples (Fig. 2b and Supplementary Fig. 3a), with individual nanotubes measuring ≈ 10–16 nm in diameter and 300–500 nm in length. The smooth and clean tubular walls of TNTs (Supplementary Fig. 3b) remain intact after W loading, suggesting the uniform dispersion of W species on the TNT surfaces without aggregation or the formation of polymer residues (Fig. 2b). The STEM-EDS mapping image, as shown in Fig. 2c, exhibits a homogeneous distribution of the elements Ti, O, and W throughout W-TNT-300, further suggesting the low dispersity in shape of W atoms for the W-TNT series.

a XRD patterns of W-TNT-300 and TNT. b HR-TEM image of W-TNT-300. c STEM-EDS mapping image of W-TNT-300. d–f HAADF-STEM images of the 54%W-TNT-600, W-TNT-600, and W-TNT-1000, insets show the intensity profile across the tungsten atoms indicated by the yellow solid circles. g XANES spectra and h EXAFS spectra of W foil, WO3, and 54%W-TNT-600. The color scheme of the atoms in the illustration is red (O) for oxygen, blue (Ti) for titanium, and grey (W) for tungsten. i W 4 f core level XPS spectra of W-TNT-600, W-TNT-1000, and 54%W-TNT-600. Source data are provided as a Source Data file.

By combining X-ray absorption near-edge structure (XANES) and extended X-ray absorption fine structure (EXAFS) analyses (Fig. 2g, h), the local configuration of W atoms on TNTs was determined. The W L3-edge XANES spectra (Fig. 2g) reveal an absorption edge energy for the 54%W-TNT-600 sample intermediate to those of metallic W and WO3 references, indicating the W oxidation state between 0 and +630. Furthermore, the Fourier transforms of the EXAFS data (Fig. 2h) show a peak at 2.61 Å for W foil, characteristic of the W-W scattering path, and the absence of this peak in the spectrum of the 54%W-TNT-600 clearly suggests the atomic dispersion of W species. In contrast, the 54%W-TNT-600 exhibits a single prominent shell at 1.3 Å, assigned to the W-O scattering path. This position is different from the W-O peak observed at 1.4 Å in the WO3 reference31. The absence of metallic/oxidized cluster signatures, combined with the single W-O shell for 54%W-TNT-600, confirms the atomic dispersion of W species on the TNTs surface. Quantitative details of the W coordination environment, including coordination number and bond length, can be determined by EXAFS fitting results (Supplementary Fig. 4 and Supplementary Table 3). The close correspondence of the fitted EXAFS model to the experimental data in both R-space and q-space confirms the reliability of the fitting approach. Quantitative analysis of the best-fit parameters (Supplementary Table 3) suggests that the W atom is anchored on the TNTs surface via two oxygen atoms, each located at a vertex of a neighboring Ti-O octahedron, with the W-O-Ti bond length being 2.99 Å. The W atom is further coordinated by two terminal W-O bonds with lengths of 1.78 and 1.93 Å, respectively.

The distribution of W single atoms was further corroborated by high-angle annular dark-field scanning transmission electron microscopy (HAADF-STEM), as a capable means for the sub-Å resolution measurements. HAADF-STEM images of the 54%W-TNT-600 (Fig. 2d) clearly reveal that individual W atoms are well dispersed on the TNT carrier, as illustrated by the line-scan profile taken from the yellow-framed atom row. Statistical analysis of the bright spots, with an average size of ≈ 0.2 nm, confirms the single-atom state of W atoms. The sharp intensity increases in the line-scan profiles result from the additional intensity contributions of W atoms on the Ti column32. This observation aligns with the EXAFS analysis, suggesting that single W atoms are anchored above the vertical positions of Ti atoms. Interestingly, a distinct difference in the distribution of W single atoms between the two series of samples (SS and SA) is evident from the HAADF-STEM images. As shown in Fig. 2e, f, the two SS samples (W-TNT-600 and W-TNT-1000) exhibit similar morphologies featured by correlated W single atoms adjacent to each other, in significant contrast to the relatively isolated W single atoms observed in a typical SA sample (54%W-TNT-600), although the W-TNT-1000 and 54%W-TNT-600 samples are measured to exhibit approximate W loading amount (Fig. 2f). HAADF-STEM images of single nanotube give more detailed information, W atoms are all distributed in a correlated form featured by local aggregation in three typical samples of the SS series (W-TNT-300, W-TNT-600, and W-TNT-1000) (Supplementary Fig. 5a–c). The d values corresponding to W-TNT-300, W-TNT-600, and W-TNT-1000 are 1.14, 1.51, and 1.90 nm, respectively, by statistically analyzing the nearest neighbor SS spacing of the HAADF-STEM images (Supplementary Fig. 6). As mentioned in the concept of our strategy, the passivation region of the lattice is closely related to the length of PEG chains. As the PEG chain length increases, the passivation region on the TNT surface becomes larger, and thus the spacing between SS increases (Supplementary Fig. 5d–f). In contrast to the SS series, the W atoms in 54%W-TNT-600 exist mainly as SA (Supplementary Fig. 7). The reason for this phenomenon is that the decrease in the number of precursors below the saturation ratio leads to the dispersion of neighboring atoms with increasing spacing, which is responsible for the transition from SS to SA.

In case the evidence from HAADF-STEM images can only reflect local information, X-ray photoelectron spectroscopy (XPS) provides further evidence for the distinct dispersion of W single atoms between the SS and SA samples, as revealed by a close examination about the W 4f spectra (Fig. 2i). The XPS profiles can be deconvoluted into two doublets for the three samples, where the prominent peaks appearing as shoulders at 34.7 eV (W 4f7/2) and 36.7 eV (W 4f5/2) can be ascribed to the W5+ doublet, and the peaks at 35.8 eV (W 4f7/2) and 37.8 eV (W 4f5/2) are attributable to the W6+ doublet. Interestingly, similar W5+/W6+ ratio (4.75) is obtained for the two SS samples (W-TNT-600 and W-TNT-1000), whereas the SA sample (54%W-TNT-600) exhibits a significantly lower value (1.31) (Supplementary Table 4). A decreasing W5+/W6+ ratio usually corresponds to a transformation from correlated state to isolated state for single atoms33, which confirms the success in manipulating the single-atom distribution to achieve correlated or isolated configurations. We suppose that the distinct distributions of single atoms as isolated and correlated sites on the TNT substrate would result in different SERS behaviors.

SERS properties for the SS and SA series of W-TNT samples

To examine the SERS activities regarding the distinct distribution of single atoms in the two series, MB was selected as a representative probe. To figure out the single-atom induced signal variations, we try to avoid other resonant SERS effects such as molecular resonance of MB, and thus the Raman spectra are recorded under a 532 nm laser (see Supplementary Note 2). As clearly depicted by the Raman profiles in Fig. 3a, b, the prominent band at 770, 1395, and 1625 cm−1 can be attributable to the Raman vibration of ν(C-S) stretches, νsym(C-N) symmetric stretches, and ν(C-C)ring ring stretches from the MB molecules (Supplementary Table 5)34. Enhanced Raman signals of the target molecules can be obtained on the single-atom substrates, in significant contrast to the negligible signals observed on the TNTs substrate. The variation in signal intensities among different W-TNT samples further indicates single-atom-induced SERS enhancement. For the SS series with correlated single sites controlled by PEG molecular weight, the Raman signal intensity increases first and then decreases as the PEG molecule weight increases (from 300 to 1000), with the largest intensity achieved with the W-TNT-600 sample (Fig. 3a). While for the SA series with isolated single atoms manipulated by W-PEG precursor ratio descending from saturated loading (W-TNT-600), the Raman signals get a large increase to the maxima with the 54%W-TNT-600 sample, and then decrease sharply for samples obtained at relatively small W ratios (Fig. 3b).

Raman spectra of (a) MB (1.0 × 10−5 M) and d 4MBA (1.0 × 10−4 M) collected on W-TNT-300, W-TNT-400, W-TNT-600, W-TNT-800, and W-TNT-1000. In the molecular schematic, atoms are colored brown (C) for carbon, blue (N) for nitrogen, yellow (S) for sulfur, pale pink (H) for hydrogen, and red (O) for oxygen. Raman spectra of (b) MB (1.0 × 10−5 M) and e 4MBA collected on W-TNT-600, 74%W-TNT-600, 54%W-TNT-600, 39%W-TNT-600, and 19%W-TNT-600. Enhancement factors of two series of samples for (c) MB (1.0 × 10−5 M) and f 4MBA (1.0 × 10−4 M). g Raman spectra of MB at concentrations ranging from 10−5 to 10−9 M collected on 54%W-TNT-600. The spectra corresponding to 10−9 M are magnified by a factor of 5. h Raman spectra of 4MBA at concentrations ranging from 10−4 to 10−7 M collected on 54%W-TNT-600. i Raman spectra of BPA, DA, Cyt, and Tyr at concentrations of 10−3M collected on 54%W-TNT-600. Source data are provided as a Source Data file.

To give a quantitative comparison among the SERS enhancement relative to W loading, the reproducibility of the results was first ensured by collecting the Raman profiles of the probe molecules from 20 randomly selected spots on each substrate (Supplementary Figs. 8, 9). The small relative standard deviation (RSD) values (less than 15%) suggest the acceptable reproducibility of Raman signals obtained with the W-TNT substrates. Subsequently, the average intensity of the MB signature band at 1625 cm−1 was plotted against the experimental W loading amount for the two series of W-TNT samples (Fig. 3c). For the SS series (marked with red dots), the signal intensity gradually increases as the W ratio decreases from 13.2 to 11.4 wt.%, reaching a maximum with the W-TNT-600 sample. The intensity then decreases with further reductions in the W ratio, as observed in the W-TNT-800 and W-TNT-1000 samples, which have W ratios of 9.8 and 8.8 wt.%, respectively. It is noteworthy that the SA series (marked in black) shares the same sample of W-TNT-600 with the SS series, but with W ratios gradually decreasing from the saturated loading (W-TNT-600). A further increasing Raman intensity can be obtained at a relatively small W ratio of 6.2 wt.% (54%W-TNT-600), and then decreases sharply with a small W ratio. Interestingly, significantly different signal intensities are obtained between the SS and SA samples, even when measured at approximately the same W ratios, as highlighted by the clearly separated black and red lines for samples with W ratios in the range of 11.4 to 8.4 wt.%. These differences are likely due to the correlated versus isolated distributions of single atoms in the two sample series (as demonstrated in Fig. 1e), which will be further discussed in the following sections.

The Raman spectra of diluted MB solutions show significant intensity enhancement, with detectable signals observed at a concentration as low as 10−9 M, demonstrating its low detection limit (Fig. 3g). Then, the prominent band at 1625 cm−1 for MB was selected for the calculation of EF, based on the magnification of Raman intensity compared with that on bare substrate. The EF values exhibit a slightly increase as the concentration of probe molecule decrease, reaching a maximum of 2.25 × 108 for 10−8 M MB, which is prominent among the documented ones obtained with plasmon-free substrates, such as W18O49, TiO2, and others (Supplementary Table 6)8,35.

Beyond dye molecules, the SERS enhancement of 4MBA, a typical small-molecule probe, is further validated by variations in its characteristic bands at 1074 and 1596 cm−1 when measured on different W-TNT samples (Fig. 3d, e, Supplementary Figs. 10, 11, and Supplementary Table 7)36, showing a detection limit as low as 10−7 M (Fig. 3h). Interestingly, the SERS signal variations in the SS and SA series exhibit quite similar trends to those observed with MB, clearly collaborating the phenomenon that SERS enhancements are essentially related to the distribution of single atoms in our W-TNT samples (Fig. 3f).

Moreover, the W-TNT substrates are also feasible in tracking a variety of practical molecules, such as Tyr, Cyt, DA and BPA. Taking 54%W-TNT-600 sample as an example, enhanced Raman signals of the characteristic bands from Tyr (860 and 830 cm−1), Cyt (791 cm−1), DA (752, 796, and 1286 cm−1), and PBA (640, 818, 1112, and 1180 cm−1) can be clearly observed under the incident laser of 532 nm (Fig. 3i). In contrast, the parent TNT sample shows almost no distinguishable signals for these molecules when measured under the same conditions (Supplementary Fig. 12). These findings consistently indicate that the incorporation of single atoms with precisely controlled distributions significantly enhances the SERS activity of the supporting semiconductors. This improvement enables the detection of practical molecules that are typically difficult to track due to their relatively small Raman cross-sections.

Mechanism of the SERS enhancement on single-atom substrates

Building on the above observations, we now address the underlying mechanism responsible for the significantly varied SERS enhancement influenced by the relative locations of single-atom W species. Drawing insights from the pioneering semiconductor SERS theory proposed by Lombardi et al.37,38,39, we consider the roles of resonances such as charge-transfer, exciton (or interband transition), and molecular resonances in contributing to the differing SERS enhancements of the W-TNT samples. This analysis excludes potential contributions from specific surface area, adsorption capacity, and the localized surface plasmon resonance (LSPR) effect (Supplementary Figs. 13, 14). The optical absorption spectrum of W-TNT preloaded with MB reveals the emergence of a band with an onset at 591 nm, a characteristic that is not present in the spectrum of MB mixed with pristine TNTs (Supplementary Fig. 15). The band locates between the interband transition absorption edge of W-TNT (350 nm) and the photo-absorption band of MB (660 nm), which provides clear evidence for photo-induced charge transfer (PICT) between MB and W-TNT, typically comprising the core of semiconductor SERS enhancement.

To further elucidate the mechanisms underlying the differing SERS performance of the two W-TNT series (SS and SA) compared to pristine TNTs, a comparative analysis of their energy-level structures was conducted. This analysis draws on data from XPS valence-band spectra, Mott–Schottky analysis, and UV–Vis spectroscopy (Supplementary Figs. 16-18, and Supplementary Table 8). Figure 4a depicts the energy-level diagrams and possible PICT transitions for W-TNT-1000, W-TNT-600, 54%W-TNT-600, and TNTs, using MB and 4MBA as representative analytes. The reference TNT sample exhibits a conduction band minimum (CBM) at −3.78 eV and a valence band maximum (VBM) at −7.06 eV, with a Fermi level (EF) at −4.15 eV located below the CBM, indicative of its n-type semiconducting nature. Considering that the frequencies of both the interband excitonic transition and the interfacial PICT transitions (VBM to LUMO or HOMO to CBM) in the TNT-analyte system are away from resonant excitation (2.33 eV), they probably contribute little to the overall SERS enhancement as observed with pristine TNTs. In contrast, the introduction of W single-atom species induces a notable downward shift of both the CBM and VBM in the three W-TNT samples, accompanied by a relatively elevated Fermi level within the conduction band. This shift indicates electron accumulation in the CBM. The down-shifted band levels energetically permit resonant PICT transitions between the CBM of W-TNTs and the HOMO levels of analyte molecules (MB and 4MBA), leading to significantly enhanced SERS activity in the W-TNT samples. However, the substantial variations in SERS performance among different W-TNT samples cannot be fully explained by the relatively small differences in their band structures. This suggests that additional factors, beyond the electronic band configuration, are influencing the observed SERS performance. These factors are explored in subsequent sections.

a Energy-level diagrams of TNT, W-TNT-600, W-TNT-1000, and 54%W-TNT-600 with respect to the analyte of MB and 4MBA. b ELF diagram of the 4MBA-SA system. c Densities of states of SA, SS, and CS. Differential charges and charge transfer amount for 4MBA on (d) SA, e SS, and f CS, where the blue area represents charge loss and the yellow area represents charge aggregation. Source data are provided as a Source Data file.

The results of PL spectroscopy (Supplementary Fig. 19) show that the intensity of the emission peaks of different samples is reduced after the introduction of W atoms, but to different degrees, which is attributed to the fact that W atoms, together with the surrounding microenvironment,t act as electron traps and inhibit the recombination of electrons and holes. Further calculations of the degree of charge transfer (ρCT) suggest that 54%W-TNT-600/MB shows a rather high ρCT value of 0.49, larger than the value of 0.44 for W-TNT-600/MB and 0.39 for W-TNT-1000/MB (Supplementary Table 9). Therefore, it can be inferred that W atoms effectively change the carrier distribution on the TNT surface, alter the carrier separation efficiency of W-TNT samples, and thus affect the SERS activity. To gain a deeper understanding of PICT-related SERS, density functional theory (DFT) calculations were employed to simulate variations in the surface charge distribution of W-TNT samples at the sub-nanometer scale, which directly determine their CT capability. A monolayer of H2Ti3O7 was chosen as the support for anchoring W atoms to construct models for SA, SS, and CS configurations. By combining results from the electron localization function (ELF), projected density of states (PDOS), differential charge density, Bader charge analysis, electrostatic potentials (EPS), and dipole moments (μ), the CT capability of the three configurations is systematically investigated from three perspectives: CT sites, CT probability, and CT-induced polarization. ELF is first used to indicate CT sites based on the degree of electron localization, with yellow and cyan regions representing highly localized and delocalized electrons, respectively. High ELF regions indicate areas with high charge density where electron movement is restricted, while low ELF regions are more conducive to electron flow. As shown in Fig. 4b, an extensive region of low ELF surrounds the W atoms, in contrast to the more localized Ti regions below. This suggests that W atoms act as interfacial channels for charge transfer, consistent with the formation of charge transfer complexes between W-TNT samples and probe molecules (e.g., 4MBA), as discussed earlier. Furthermore, the ELF along the c-axis for the three single-atom models with different degrees of association (SA, SS, CS) is represented in Supplementary Fig. 20, with the region of W atoms shifting from cyan to magenta, indicating that the relative positions of the W atoms directly affect the sub-nanoscale charge distribution. CT probability is then evaluated using Fermi’s golden rule40,41,42, which describes the electron jump probability as the following Eq. (1):

where |a〉 and |b〉 denote the initial and final states of the charge jump, ħ is the reduced Planck constant, M is the interaction operator of the two states, and \({g}_{b}\) is the DOS of the final state. As shown in Fig. 4c, the DOS near the Fermi energy levels align with the Fermi level offset into the conduction band of the W-TNT sample (Fig. 4a). The zoomed-in plots in Fig. 4c clearly demonstrate that the DOS near the Fermi energy level is significantly higher for the SA sample compared to the SS and CS configurations. This indicates that the greater number of accessible energy states in the SA sample facilitates more frequent occurrences of CT, while electrons occupying |a〉 state near the Fermi surface in SA have a higher probability of jumping to the |b〉 state of the molecule.

To further investigate CT-induced polarization in the molecule-substrate system, we calculated the differential charge density using 4MBA as a probe molecule, with the adsorbed substrates being SA, SS and CS as presented from top to bottom, respectively (Fig. 4d–f, Supplementary Fig. 21). Upon the adsorption of 4MBA, electron donation (blue regions) is observed at the binding sites, while electronic charge accumulates in the upper part of the molecule (yellow regions). This charge redistribution, mediated by W atoms, amplifies the molecular polarization rate. Notably, this mechanism differs significantly from conventional charge-transfer processes involving transitions between the valence and conduction bands of semiconductors. Additionally, Bader charge analysis quantitatively assessed the strength of CT-induced polarization. The charge transfer between the parent TNT sample and 4MBA is 0.3350 e, which is significantly lower than the three W-containing models (Supplementary Fig. 21b). Among the three W-containing models, the SA configuration transfers the highest amount of charge (0.6538 e) to the 4MBA molecule, substantially exceeding the values for the SS (0.5070 e) and CS (0.5025 e) configurations. Correspondingly, these CT-induced polarization changes cause significant changes in the EPS and dipole moments of the adsorbed molecule (4MBA). Based on ref. 19 the dipole moment of surface complexes is positively correlated with changes in polarizability (see Supplementary Note 3). It is very intuitive to see in the ESP results that there is a clear difference in the surface potentials at the ends of the 4MBA molecules. As the degree of W atom correlation increases, the blue color of the benzene ring part of the molecule becomes lighter (Supplementary Fig. 22), and the charge transfer between the surface 4MBA molecule and the substrate becomes progressively weaker. Therefore, the effect on the dipole moment of the 4MBA molecules is considerably weakened when the W atoms undergo different degrees of correlation, and the dipole moment of the 4MBA molecules adsorbed on the SS and CS substrate surfaces is 42.0 and 41.6 Debye, respectively (Supplementary Fig. 23). These findings demonstrate that the CT capability of single-atom W, which is central to the enhanced SERS effect, is strongly influenced by whether the atoms are in isolated or correlated configurations at the sub-nm scale.

Discussion

The controlled loading of single-atom W with varying degrees of association was achieved on the TNT lattice plane using polymer PEG as a molecular ruler, enabling sub-nm modulation of the local carrier distribution on the TNT surface. The introduction of single-atom W species significantly enhances the SERS activity of TNTs for detecting a wide range of molecules, from MB dyes to practical small molecules. Notably, the degree of association (ranging from SS to SA) of single-atom W plays a critical role in determining SERS performance. Among the samples, the 54%W-TNT-600 in the SA configuration exhibits the strongest SERS activity, with the highest EF of 2.25 × 108. This enhanced performance is attributed to the strong facilitation of charge transfer within the molecule-substrate system, enabled by the optimal arrangement of W atoms. Our results also demonstrate the feasibility of sub-nm manipulation of single-atom locations, providing a reference for the rational design of high-performance SERS substrates in view of local chemical environment of semiconductors.

Methods

Materials

Sodium tungstate dihydrate (Na2WO4·2H2O 99.5%) was obtained from National Medicines Corporation Ltd. of China. Sulfuric acid (H2SO4 10%), nitric acid (HNO3 70%), sodium hydroxide (NaOH 98%), polyethylene glycol (PEG, 99%, molecular weight = 300, 400, 600, 800, and 1000 g mol−1), titanium oxide (TiO2, 99.8%, anatase, 5–10 nm), ethanol (99.5%) and ethylene glycol (EG, 99%) were purchased from Aladdin chemical reagent Corp (Shanghai, China). Methylene blue (MB, 99%), 4-mercaptobenzoic acid (4MBA, 99%), tyrosine (Tyr, 99.9%), cytosine (Cyt, 99%), dopamine (DA, 98%), and bisphenol A (BPA, 99%) were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich. All of which were of analytical grade and were used as received.

Preparation of TNTs

In a typical preparation, 3.6 g of the TiO2 powder was mixed with 50 mL of NaOH (10 M) solution, followed by hydrothermal treatment of the mixture at 150 °C in a 100 mL Teflon-lined autoclave for 20 h. After cooling to room temperature, the titanate sediment was washed with deionized water, followed by acidification using HNO3 (0.1 M) while continuously stirring for more than 24 h. The TNTs product was obtained after thorough washing with deionized water until pH = 7.

Preparation of W-PEGs

The synthesis of W-PEG followed a method reported in ref. 43 Na2WO4·2H2O (1.3 mmol) and PEG with a molecular weight of 300 g mol−1 (1.3 mmol) were dissolved in deionized water (15 mL), and after stirring for 1 h at room temperature, 0.1 M H2SO4 was added dropwise to the mixture until pH = 5. W-PEG-300 was obtained by adding deionized water to make a solution volume of 20 mL (this step is to ensure that all W-PEGs have the same concentration of W) and then stirring magnetically in a light-free environment for 6 h. Keeping the molar ratio constant, the above steps were repeated using PEG-400, PEG-600, PEG-800, and PEG-1000, respectively, to obtain a series of precursors (W-PEG-400, W-PEG-600, W-PEG-800, and W-PEG-1000).

Preparation of W-TNT composite materials

In a typical procedure for the synthesis of fully loaded W-TNT, TNT powder (0.1 g) was first dispersed into 20 mL of EG/H2O (1:10) mixture, and then 5 mL of W-PEG-300 was added dropwise to the dispersion. The mixture was sealed and stirred continuously at 75 °C for 4 h. The products were obtained by centrifugation after 12 h of storage at room temperature and washed successively with deionized water and ethanol until the pH value was close to 7, and then dried in a vacuum oven at 60 °C. Then it was calcined under argon at 200 °C for 6 h, washed with ethanol and deionized water successively, and dried in a vacuum oven at 60 °C to obtain W-TNT-300. By replacing W-PEG-300 with W-PEG-400, W-PEG-600, W-PEG-800, and W-PEG-1000 and repeating the above steps, W-TNT-400, W-TNT-600, W-TNT-800, and W-TNT-1000 can be obtained, whereas for the synthesis of 73%W-TNT-600, 54%W-TNT-600, 39%W-TNT-600, and 19%W-TNT-600 were synthesized by adding 0.25, 0.5, 0.75, and 1 mL of W-PEG-600, respectively, and keeping the other conditions constant.

Measurement of SERS performance

All SERS samples were prepared using a routine immersion procedure. Typically, 800 μL of probe molecule solution of known concentration was mixed with 200 μL of W-TNT dispersion (0.4 mg mL−1). The solution was then left in the dark for 3 h to equilibrate the adsorption-desorption of the probe molecules. Finally, 20 μL of the suspension was dripped onto clean silicon wafers and dried at 60 °C for 2 h. The Raman spectra were collected using an inVia Qontor confocal Raman spectrometer with an excitation laser of 532 nm (0.02 mW). The laser spot was 1 μm in diameter. For each measurement, the signal was collected after 1 accumulation, and the accumulation time was 10 s. Raman spectra from different locations were collected for each sample, with the signal intensity averaged for final analysis to estimate the RSD values of the SERS intensity.

Measurement of MB adsorption capacity

To measure the amount of MB adsorbed on the sample, 200 μL of sample dispersion (0.4 mg mL−1) was poured into 800 μL of MB solution (1.2 × 10−5 M), and the two were thoroughly mixed by sonication and dispersion. The resulting mixture was then stored in the dark for 12 h to achieve adsorption-desorption equilibrium. The soaked mixture was centrifuged at 16,099 × g for 10 min to collect the residual MB in the solution, and the absorbance was subsequently determined by UV-Vis absorption spectroscopy. According to Lambert-Beer’s law, the relationship between MB absorption intensity (AMB) and the molar concentration of the analyte (c) can be calculated as the Eq. (2):

KMB (L cm−1 mol−1) is the molar absorption coefficient, b (cm) is the thickness of the solution, and the product of KMB and b is numerically equal to 24,465.5 (L mol−1). Therefore, the concentration after adsorption can be obtained, and the molar amount of MB adsorbed on the surface of the sample can be calculated.

Calculation of the EF

The EF was calculated using Eqs. (3–5)44:

Here, NSERS and Nbulk denote the number of MB (or 4MBA) molecules with enhanced and normal signal intensity, respectively. ISERS and Ibulk denote the enhanced and normal Raman intensity. h is the confocal depth of the laser beam (23.64 μm), M is the molecular weight of the probe molecules, ρ is the density of the probe molecules, and c is the molar concentration of the analyte. V is the volume of the droplet, NA is Avogadro’s constant, and ARaman is the Raman laser spot area (1 μm diameter). Data from MB/4MBA (0.05 M) on bare silicon wafers were used as a normal Raman reference. Assuming that the analyte is uniformly distributed on the substrate surface, 20 μL of the analyte solution spontaneously diffuses onto the substrate surface (0.5 cm × 0.5 cm) after solvent evaporation, from which the effective area of the substrate, Asub, is obtained. For the SERS active substrate loaded with the analyte molecules NSERS can be estimated using Eq. (4). Based on the molecular weights and densities of the analyte molecules (MB: 1.15 g cm−3 and 4MBA: 1.35 g cm−3), Nbulk can be calculated using Eq. (5).

Measurement of flat-band potential and energy-level diagram

The flat-band potential Vfb was estimated by extrapolating the Mott-Schottky plot of the sample to the x-axis. Based on the relationship between the Fermi level and flat-band potential, EF can be represented as the Eq. (6):

where e is the elementary charge. The standard hydrogen electrode (SHE) was determined using the potential conversion relationship based on the Ag/AgCl reference electrode (3.5 M KCl solution) as the Eq. (7):

where the absolute potential value of the SHE was estimated to be −4.5 V. Therefore, EF in reference to vacuum can be expressed as the Eq. (8):

By effectively combining the Fermi energy levels, the XPS valence band spectra and the diffuse reflectance spectra, the band energy levels relative to the vacuum can be determined.

Calculation of the degree of charge transfer

The CT (charge-transfer)-induced enhancement in contribution to the overall enhanced SERS signals of the probe molecule can be quantitatively calculated according to Eq. (9),

where Ik(CT) and Ik(SPR) are the signal intensity recorded for the imperfect symmetric mode (line k) with and without CT contributions, respectively. I0(SPR) is the signal intensity for a totally symmetric mode (line 0). If it is a non-totally symmetric mode, the main contribution to the intensity arises from the CT. At this moment, Ik(SPR) can be assumed to be 0 in many cases. In this case, the imperfect symmetric 1040 cm−1 line is chosen for line k and the totally symmetric 1075 cm−1 line is chosen for line 0.

DFT calculation details

DFT calculations were performed by means of the ab initio VASP software package based on density-functional theory, using a projection-enhanced wave (PAW) potential45. The Perdew-Burke-Ernzerhof generalized gradient approximation (GGA-PBE) was used to describe the exchange-association generalized function46. Considering that W atoms are 5 d transition metals, the correction GGA + U was used47, where the value of the electronic Coulomb interaction U was 4.0 eV and the value of the exchange interaction J was 1.0 eV48. Due to the large computational regime, the cut-off energy and electron step self-consistency convergence criteria in the relaxation, self-consistency, and electronic structure calculations were set to 500 eV and 10−5 eV, respectively. The thickness of the vacuum layer was 20 Å. The force on all atoms during relaxation of each atom was less than 0.01 eV Å−1. A 3 × 3 × 1 Gamma central Monkhorst-Pack grid was used. The molecular dynamics simulations were performed using 3 × 3 × 1 supercells running for 8000 fs at 500 K. All the above computational models were derived from 2 × 4 supercells of monolayer H2Ti3O7 as a basis. The formation energy of W- TNT was calculated by the Eq. (10):

with E(W-TNT) being the overall energy of the system after loading with W atoms, E(W) being the energy of the W precursor before loading, and E(TNT) being the energy of the TNT unloaded with W atoms. The charges of the atoms were calculated using the Bader analysis algorithm49. To visualize the charge redistribution of the metal atom modified W-TNT and 4MBA, we calculated the charge difference using the Eq. (11):

where ρtotal, ρW-TNT, and ρ4MBA are the charge density of the total molecule-substrate system, W-TNT and 4MBA, respectively. The specific relaxation configuration and electronic structure are shown in Supplementary Figs. 24–27.

For μ, spin-polarized density functional theory calculations were carried out under the scheme of generalized gradient approximation50, with the use of PBE functional51 and double numerical polarized (DNP) basis, as embedded in DMol3 package52,53. A global orbital cutoff with a radius of 4.5 Å was employed, under which the atomic charges were calculated based on fully relaxed geometries with total energy and atomic force converged to 10-5 Ha and 0.005 Ha Å−1 using Gaussian smearing (smearing width σ = 0.005 Ha). Due to the large dimension size, k-space was sampled with Gamma point, and all energies have been corrected with DFT-D correction54. Such a DNP basis and computational setting have been successfully used in the adsorption of polarized molecules and charged species55,56.

Characterization

XRD patterns of the samples were recorded on a Bruker AXS D8 Advance X-ray diffractometer with a Cu Kα radiation target. The Raman spectra were collected using an inVia Qontor confocal Raman spectrometer (Renishaw). UV-Vis spectra were collected with a UV-Vis spectrophotometer (V660, JASCO). The electronic binding energy of samples was examined by XPS on the ESCALAB 250 Xi system (Thermo Scientific) instrument. High-resolution transmission electron microscopy (HR-TEM) and selected area electron diffraction (SAED) patterns were taken on a FEI Tecnai G2 F20 microscope. The actual W content for the W-TNTs was ascertained using an inductively coupled plasma-optical emission spectrometer (Varian 720-ES). The spherical aberration-corrected STEM high-angle annular dark-field (Cs-corrected STEM-HAADF) images were taken from a JEOL ARM200F (JEOL, Tokyo, Japan) microscope equipped with a CEOS (Heidelberg, Germany) probe aberration corrector, operated at 200 keV. The N and O K-edge XANES spectra were measured at beamline BL11U of the National Synchrotron Radiation Laboratory (NSRL) of China. The X-ray adsorption fine structure spectra (W L3-edge) were collected at the BL14W1 station in the Shanghai Synchrotron Radiation Facility. Electrochemical measurements were carried out on a CHI660E electrochemical workstation (CH Instruments). For measurement of the Mott-Schottky plot, a three-electrode quartz cell setup was used, with Pt wire and Ag/AgCl/KCl serving as the counter and reference electrode, respectively. For the preparation of the working electrode, a suspension of the target material dispersed in water was spin-coated onto a piece of FTO glass (1 cm × 1 cm), until a uniform thin film was formed. The Mott-Schottky plots were collected from -1 to 1 V vs. Ag/AgCl at a frequency of 1000 Hz in 0.1 M TBAP in propylene carbonate saturated withan Ar atmosphere.

Data availability

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding authors upon request. Source data are provided with this paper.

References

Langer, J. et al. Present and future of surface-enhanced Raman scattering. ACS Nano 14, 28–117 (2020).

Ji, W., Zhao, B. & Ozaki, Y. Semiconductor materials in analytical applications of surface-enhanced Raman scattering. J. Raman Spectrosc. 47, 51–58 (2016).

Alessandri, I. & Lombardi, J. R. Enhanced Raman scattering with dielectrics. Chem. Rev. 116, 14921–14981 (2016).

Blackie, E. J., Le Ru, E. C. & Etchegoin, P. G. Single-molecule surface-enhanced Raman spectroscopy of nonresonant molecules. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 131, 14466–14472 (2009).

Cong, S., Liu, X., Jiang, Y., Zhang, W. & Zhao, Z. Surface enhanced Raman scattering revealed by interfacial charge-transfer transitions. Innovation 1, 100051 (2020).

Yin, X. et al. A multiple coupling approach to produce high-performance SERS substrates. Chin. Chem. Lett. 30, 179–182 (2019).

Musumeci, A. et al. SERS of semiconducting nanoparticles (TiO2 hybrid composites). J. Am. Chem. Soc. 131, 6040–6041 (2009).

Gu, L. et al. Populating surface-trapped electrons towards SERS enhancement of W18O49 nanowires. Chem. Commun. 54, 6332–6335 (2018).

Lin, J. et al. Direct experimental observation of facet-dependent SERS of Cu2O polyhedra. Small 14, 1703274 (2018).

Sun, H. et al. Metal–organic frameworks as surface enhanced Raman scattering substrates with high tailorability. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 141, 870–878 (2019).

Song, G., Cong, S. & Zhao, Z. Defect engineering in semiconductor-based SERS. Chem. Sci. 13, 1210–1224 (2022).

Qiao, B. et al. Single-atom catalysis of CO oxidation using Pt1/FeOx. Nat. Chem. 3, 634–641 (2011).

Yan, Y. et al. General synthesis of neighboring dual-atomic sites with a specific pre-designed distance via an interfacial-fixing strategy. Nat. Commun. 16, 334 (2025).

Wei, J. et al. Site-specific metal-support interaction to switch the activity of Ir single atoms for oxygen evolution reaction. Nat. Commun. 15, 559 (2024).

Li, X. et al. Functional CeOx nanoglues for robust atomically dispersed catalysts. Nature 611, 284–288 (2022).

Liu, Z. et al. Modulating spatial distributions of single atoms on supports for enhanced oxygen evolution. Nano Lett. 25, 5358–5365 (2025).

Ding, X. et al. Remote synergy between heterogeneous single atoms and clusters for enhanced oxygen evolution. Nano Lett. 23, 3309–3316 (2023).

Hao, Q. et al. Mechanism switch in surface-enhanced Raman scattering: the role of nanoparticle dimensions. J. Phys. Chem. Lett. 15, 7183–7190 (2024).

Yu, J. et al. Au atoms anchored on amorphous C3N4 for single-site Raman enhancement. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 144, 21908–21915 (2022).

Feng, R. et al. Single-atom sites on perovskite chips for record-high sensitivity and quantification in SERS. Sci. China Mater. 65, 1601–1614 (2022).

Feng, R. et al. Single-atom site SERS chip for rapid, ultrasensitive, and reproducible direct-monitoring of RNA binding. Adv. Healthc. Mater. 13, 2301146 (2024).

Li, M. et al. VSe2-xOx@Pd sensor for operando self-monitoring of palladium-catalyzed reactions. JACS Au 3, 468–475 (2023).

Liu, D. et al. Ag aerogel-supported single-atom Hg nanozyme enables efficient SERS monitoring of enhanced oxidase-like catalysis. Anal. Chem. 95, 4335–4343 (2023).

Xi, H. et al. Peroxidase-like single Fe atoms anchored on Ti3C2Tx MXene as surface enhanced Raman scattering substrate for the simultaneous discrimination of multiple antioxidants. Nano Res 16, 10053–10060 (2023).

Pan, X. et al. Ultrafast ion sputtering modulation of two-dimensional substrate for highly sensitive Raman detection. ACS Mater. Lett. 4, 2622–2630 (2022).

Kitano, M. et al. Protonated titanate nanotubes with Lewis and Brønsted acidity: relationship between nanotube structure and catalytic activity. Chem. Mater. 25, 385–393 (2013).

Camposeco, R. et al. Behavior of Lewis and Brönsted surface acidity featured by Ag, Au, Ce, La, Fe, Mn, Pd, Pt, V and W decorated on protonated titanate nanotubes. Microporous Mesoporous Mater. 236, 235–243 (2016).

Xue, Y. et al. Physisorption of poly (ethylene glycol) on inorganic nanoparticles. ACS Nano 16, 6634–6645 (2022).

Lang, R. et al. Single-atom catalysts based on the metal-oxide interaction. Chem. Rev. 12, 11986–12043 (2020).

Liu, J. et al. High performance platinum single atom electrocatalyst for oxygen reduction reaction. Nat. Commun. 8, 15938 (2017).

Yan, J. et al. Single atom tungsten doped ultrathin α-Ni(OH)2 for enhanced electrocatalytic water oxidation. Nat. Commun. 10, 2149 (2019).

Chen, Z. et al. Thermal migration towards constructing W-W dual-Sites for boosted alkaline hydrogen evolution reaction. Nat. Commun. 13, 763 (2022).

Ding, K. et al. Identification of active sites in CO oxidation and water-gas shift over supported Pt catalysts. Science 35, 189–192 (2015).

Song, G., Gong, W., Cong, S. & Zhao, Z. Ultrathin two‐dimensional nanostructures: surface defects for morphology‐driven enhanced semiconductor SERS. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 60, 5505–5511 (2021).

Pan, T. et al. Hydroxyl group-abundant TiO2 semiconductor SERS sensor toward polymerization inhibitor sensing. J. Phys. Chem. C. 124, 20530–20537 (2020).

Li, R. et al. Vibrational spectroscopy and density functional theory study of 4-mercaptobenzoic acid. Spectrochim. Acta, Part A 148, 369–374 (2015).

Lombardi, J. R. & Birke, R. L. A unified approach to surface-enhanced Raman spectroscopy. J. Phys. Chem. C. 112, 5605–5617 (2008).

Lombardi, J. R. & Birke, R. L. A unified view of surface-enhanced Raman scattering. Acc. Chem. Res. 42, 734–742 (2009).

Lombardi, J. R. & Birke, R. L. Theory of surface-enhanced Raman scattering in semiconductors. J. Phys. Chem. C. 118, 11120–11130 (2014).

Jensen, L. & Schatz, G. C. Resonance Raman scattering of rhodamine 6G as calculated using time-dependent density functional theory. J. Phys. Chem. A 110, 5973–5977 (2006).

Tan, Y., Ma, L., Gao, Z., Chen, M. & Chen, F. Two-dimensional heterostructure as a platform for surface-enhanced Raman scattering. Nano Lett. 17, 2621–2626 (2017).

He, Z. et al. Two-dimensional TiVC solid-solution MXene as surface-enhanced Raman scattering substrate. ACS Nano 16, 4072–4083 (2022).

Wang, C. et al. Ultrahigh photocatalytic rate at a single‐metal‐atom‐oxide. Adv. Mater. 31, 1903491 (2019).

Cong, S. et al. Electrochromic semiconductors as colorimetric SERS substrates with high reproducibility and renewability. Nat. Commun. 10, 678 (2019).

Blöchl, P. E. Projector augmented-wave method. Phys. Rev. B 50, 17953–17979 (1994).

Perdew, J. P., Burke, K. & Ernzerhof, M. Generalized gradient approximation made simple. Phys. Rev. Lett. 77, 3865–3868 (1996).

Dudarev, S. L., Botton, G. A., Savrasov, S. Y., Humphreys, C. J. & Sutton, A. P. Electron-energy-loss spectra and the structural stability of nickel oxide: an LSDA+U study. Phys. Rev. B 57, 1505–1509 (1998).

Yang, W., Wen, Y., Chen, R., Zeng, D. & Shan, B. Study of structural, electronic, and optical properties of tungsten-doped bismuth oxychloride by DFT calculations. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 16, 21349–21355 (2014).

Bader, R. F. W. & Nguyen-Dang, T. T. Quantum theory of atoms in molecules–Dalton revisited. Adv. Quantum Chem. 14, 63–124 (1981).

Kohn, W. & Sham, L. J. Self-consistent equations including exchange and correlation effects. Phys. Rev. 140, A1133 (1965).

Hammer, B., Hansen, L. B. & Nørskov, J. K. Improved adsorption energetics within density-functional theory using revised Perdew-Burke-Ernzerhof functionals. Phys. Rev. B 59, 7413–7421 (1999).

Delley, B. An all‐electron numerical method for solving the local density functional for polyatomic molecules. J. Chem. Phys. 92, 508–517 (1990).

Delley, B. From molecules to solids with the DMol3 approach. J. Chem. Phys. 113, 7756–7764 (2000).

Tkatchenko, A. & Scheffler, M. Accurate molecular van der Waals interactions from ground-state electron density and free-atom reference data. Phys. Rev. Lett. 102, 073005 (2009).

Zeng, X. et al. Simultaneously tuning charge separation and oxygen reduction pathway on graphitic carbon nitride by polyethylenimine for boosted photocatalytic hydrogen peroxide production. ACS Catal. 10, 3697–3706 (2020).

Chen, H. et al. Investigating the electron-scale adsorption mechanisms using DFT calculations and experimental studies in self-assembly magnetic biochar gel incorporated with graphene nanosheets for enhanced Sb(III) removal. Chem. Eng. J. 487, 150740 (2024).

Acknowledgements

This work is supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (No. 22175198, S. C., No. 52172299, Z. Z.; No. 52403357, H. S., and No. 12274210, X. W.) and the China Postdoctoral Science Foundation (2024M762317, H. S.). S. C. would like to acknowledge the support by the International Partnership Program of the Chinese Academy of Sciences (Grant No. 320GJHZ2023011MI), Suzhou Industrial Science and Technology Program (SYC2022036), and the High-end Talents Program of Jiangxi province (jxsq2023101113). The authors are grateful for the technical support for Nano-X from Suzhou Institute of Nano-Tech and Nano-Bionics, Chinese Academy of Sciences (SINANO). We sincerely thank Professor Chenghua Sun for his invaluable guidance and expertise in the calculation of molecular dipole moments.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

S. C. conceived the project. S. C. and J. Z. designed the experiments and analyzed the data. J. Z., X. Z., G. C., Z. C. (Zhigang Chen), T. Z., and Z. C. (Zhiwei Chen). performed material synthesis, characterization, device fabrication and electrochromic measurements. J. Z., S. C., D. W., Y. Y., S. M., Y. S. and H. R. designed the figures. X. W., C. M., H. S., Z. Z. and S. C. supervised the study. S. C., J. Z. and X. W. wrote the manuscript with the assistance of all authors. J. Z., S.C., X. Z., S. M., S.W., Z. Z. and H. S. added the necessary experimental and theoretical calculations and improved the manuscript as suggested by the reviewers. All authors discussed the results and commented on the manuscript.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Peer review

Peer review information

Nature Communications thanks Xingce Fan, Xiaotian Wang, and Liangbao Yang for their contribution to the peer review of this work. A peer review file is available.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Source data

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Zhou, J., Zha, X., Ma, S. et al. Polymer-guided grafting of single W atoms onto titanate nanotubes increases SERS activity in semiconductors. Nat Commun 16, 8042 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-025-63224-5

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-025-63224-5