Abstract

Luminescent cerium(III) compounds with 5d-4f transition have received extensive interest in phosphor, photocatalysis, and electroluminescence. Due to the high vacuum 5 d energy level, Ce(III) compounds with emission from ultraviolet to yellow region have been well developed, while orange to deep-red emissions are scarce. In this work, we develop a series of molecular Ce(III) complexes with red to deep-red emission by using S-coordinating dithiobiuret ligands, providing new insights into long-wavelength Ce(III) emitters. The longest emission maxima are extended to 725 nm with a photoluminescence quantum efficiency of 31%. Furthermore, it is found that tuning on the steric hindrance yields both mononuclear and dinuclear Ce(III) complexes with different emission colors, as well as different conversion behaviors between the two structures in toluene solution. This work not only shows the great potential of S-coordinating ligands in achieving deep-red Ce(III) emitters, but also demonstrates interesting coordination chemistry of molecular Ce(III) complexes.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Cerium, as a member of the lanthanide elements, has the highest crust abundance among the lanthanide series1. Among the various properties of cerium, trivalent cerium (Ce(III)) exhibits unique optical properties in the field of luminescence2,3 with the radiative transition from 5 d1 to 4f1. Owing to the adjustability of the energy level of 5 d orbitals and parity-allowed d-f transition mechanism, numerous Ce(III) emitters with tunable emission and short excited decay lifetimes in a nanosecond scale have been reported4,5,6,7,8. Without the drag of the intermediate level between the 5d and 4 f state, Ce(III) emitters usually display pretty high photoluminescence quantum yields (PLQYs, ΦPL). According to the above advantages, luminescent Ce(III) compounds have been applied to lighting, photocatalysis8,9, inkjet printing10, and electroluminescence devices5,11,12,13 with vigorous vitality.

Restricted by the rather high vacuum 5 d energy level of Ce(III) (6.35 eV14,15), most luminescent Ce(III) compounds emit light with high energy from ultraviolet to yellow12,16,17,18. Even in inorganic Ce(III) phosphors that have been extensively studied, orange-red emissions are not common, and the highest PLQY is 45%19. Molecular Ce(III) complexes, as a new class of Ce(III) emitters5,6,9,11,12,20,21,22,23,24,25,26, have gradually gained attention in recent years due to well-defined molecular structures, good solubility in organic solvents, and clear structure-activity relationships. As for now, Ce(III) complexes with longer wavelength emission are still rare, as the molecular design requires ligands with even stronger covalence and calls for strong donor ligands like cyclopentadienyl18,27,28 and pyrazolate29,30, and the related research is difficult and rare. In 2018, Wickleder et al. reported a yellow-emitting Ce(III) complex [Ce(CptBu2)2(μ-Cl)]2 with photoluminescence (PL) maxima of 560 nm and a PLQY of 61%18. In 2022, Taydakov et al. synthesized orange- and orange-red-emitting Ce(III) coordination polymers based on 2-pyridylpyrazole ligand29,30. With stronger bond covalence, the PL maxima of the two complexes redshift to 604 nm and 642 nm with PLQY lower than 1%, respectively. Considering the low cost of cerium element and the potential application of deep-red-emitting materials in photo detectors31, light-conversion32,33, and organic light-emitting diodes34,35, achieving efficient deep-red-emitting Ce(III) complexes through reasonable ligand design is desirable.

In inorganic Ce(III) phosphors, a combination of both nephelauxetic effects on 5 d centroid shift and crystal-field splitting is extensively applied in the design of materials with different emission wavelengths36,37. To fulfill our target, the strategies in inorganic phosphors are worth learning from, that is, both ligand skeletons with coordinating atoms having strong covalence and polarizability to enhance 5 d centroid shift, and with electron-donating groups to promote ligand-field splitting are in necessity. Inspired by the orange-red-emitting cerium sulfide38,39, the sulfur atom with high electronegativity and soft-donor properties is selected as the coordination atom to construct molecular Ce(III) complexes with deep-red emission (Fig. 1a).

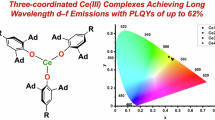

a Influence of both nephelauxetic effect and ligand-field splitting on 5 d orbitals and emission energy; b Summary of PLQY and PL maxima data of luminescent Ce(III) complexes in literature and this work. c Molecular structures of Ce(III) complexes and controllable tuning of mononuclear and dinuclear structures.

In this work, with the exploration of strong-donor S-coordinating dithiobiuret ligand, a series of Ce(III) complexes Ce-dtuR4 with the formula of Cen[(N(CSNR2)2]3n (n = 2, R = Me, Et; n = 1, R = iPr and Cy, N(CSNR2)- is R group substituted dithiobiuret anion, shortened as dtuR4) emitting red to deep-red light were synthesized. For PL properties, the best two complexes, Ce-dtuMe4 and Ce-dtuCy4, display red- and deep-red-emissions with PL maxima of 640 nm and 725 nm and PLQY of 22% and 31%, respectively (Fig. 1b). For molecular structure, via tuning of the steric hindrance of the ligand, both mononuclear- and dinuclear-type Ce(III) complexes were obtained and the conversion between the two structures has also been elucidated (Fig. 1c). To the best of our knowledge, this work represents new Ce(III) emitter with PL maxima exceeding 700 nm, showing the pioneering result beyond traditional cognition in the luminescence of Ce(III), as well as a unique example jumping out of classical O- or N-coordination systems.

Results

Synthesis and structures

The synthesis routes of the coordination ligands and the corresponding Ce(III) complexes are depicted in Fig. 2. Starting from thiophosgene, the reaction with secondary amine yields the corresponding thiocarbamoyl chloride. The intermediate was reacted with KSCN and then secondary amine to give symmetrical 1,1,5,5-tetra-substituted dithiobiuret HdtuR4 (R = Me, Et, iPr, and Cy). HdtuMe4 and HdtuEt4 are soluble in acetonitrile (MeCN) and were recrystallized using MeCN, while HdtuiPr4 and HdtuCy4 were precipitated directly as white solids during the reaction. It’s noteworthy that HdtuEt4, HdtuiPr4 and HdtuCy4 are not stable enough to be stored even in solid-powder state under inert gas at room temperature, as Brown et al. proposed that dithiobiuret may decompose into carbamoyl isocyanate and corresponding amines upon standing, followed by side reactions of irreversible polymerization40.

The Ce(III) complexes are denoted as Ce-dtuR4 (R = Me, Et, iPr, and Cy). Except for insoluble Ce-dtuMe4, which was synthesized via the acid-base reaction between HdtuMe4 and Ce[N(SiMe3)2]3 in MeCN to afford the pure product, all the other three complexes were synthesized by mixing the stoichiometric HdtuR4 ligand, cerium triflate (Ce(OTf)3), and NaH in tetrahydrofuran (THF) via salt metathesis, followed by recrystallization, because these complexes show great solubility in low-polarity solvents like dichloromethane (DCM) and toluene (PhMe). To further verify the oxidation state of Ce in the prepared samples, X-ray photoelectron spectroscopy (XPS) was conducted for solid-powder Ce-dtuR4 (R = Me, Et, iPr, and Cy) complexes. As shown in Supplementary Fig. 1, all four complexes exhibit two peaks centered at about 904 eV and 885 eV, respectively, which are attributed to 3d3/2 and 3d5/2 of Ce(III)41, indicating the trivalent essence. Upon standing under nitrogen for several months, the four complexes are stable without observable change, while Ce-dtuEt4 decomposes slowly to an unidentified orange-pink powder if there is long-term presence of alcohol solvent vapor in the glove box.

Except for the single crystal of Ce-dtuMe4 being obtained during the reaction of Ce[N(SiMe3)2]3 and HdtuMe4, single crystals of Ce-dtuR4 (R = Et, iPr, and Cy) were obtained by slowly evaporating a mixed solution of the corresponding complex in DCM/THF and n-hexane. The molecular structures of these Ce(III) complexes were characterized by single-crystal X-ray diffraction (SXRD), and the coordination geometry of the four complexes can be divided into two classes: dinuclear eight-coordinating and mononuclear six-coordinating. The crystallographic data and coordination bond lengths are shown in Supplementary Table 1 and Supplementary Table 2. The simulated powder X-ray diffraction (PXRD) data using SCXRD data are shown in Supplementary Fig. 2, as the complexes themselves are not stable enough in air to conduct the PXRD experiments. To better understand the molecular structure of the four complexes, the key structure parameters are shown in Table 1. Here, we take Ce-dtuMe4 and Ce-dtuCy4 as representatives, considering the smallest and largest steric hindrance across the whole series. In dinuclear Ce-dtuMe4, the crystal belongs to the monoclinic P21/n space group. One asymmetric unit contains one Ce(III) center and three dithiobiuret ligands, indicating a completely equivalent coordination environment between the two Ce atoms. Meanwhile, the molecule exhibits C2-symmetry and coordination geometry of dodecahedron close to tetragonal antiprism, with two different typical Ce-S bond lengths, which are derived from the bonding between Ce(III) and both the terminal ligand (Ave.(Ce-S) = 2.90 Å) and the bridging ligand (Ave.(Ce-S) = 3.04 Å), respectively. In mononuclear Ce-dtuCy4, the crystal belongs to triclinic \(P\bar{1}\) space group. The coordination geometry can be best described as a twisted trigonal prism with C3-symmetry, and the average Ce-S bond length is 2.84 Å. Compared with dinuclear Ce-dtuMe4, the shorter bond length in Ce-dtuCy4 implies a stronger interaction between the central metal and coordinating atoms.

The structure change of these Ce(III) complexes from dinuclear to mononuclear occurs during the variation of the substituent from ethyl to iso-propyl on the dithiobiuret ligand. As shown in Supplementary Fig. 3, Ce-dtuEt4 exhibits a similar but more asymmetric dinuclear structure with Ce-dtuMe4; As for Ce-dtuiPr4, the mononuclear structure is nearly identical to its Ce-dtuCy4 analog. In other words, at least secondary carbon substituents should be attached to N atoms to provide sufficient steric hindrance to obtain mononuclear complexes. In addition, we also tried to synthesize ligands with tertiary carbon substituents and aromatic substituents, such as tert-butyl and phenyl, but the synthesis route didn’t work, as either the large steric hindrance or the electron-withdrawing groups may impede the nucleophilic substitution at the first step.

Photophysical properties in solid state

As Ce-dtuMe4 is insoluble in common organic solvents, we first studied the photophysical properties of the four Ce-dtuR4 complexes in solid-powder state to attain systematic information. The photographs of the complexes under ambient light and 365 nm UV light are shown in Fig. 3a. The PL spectra of dinuclear Ce-dtuMe4 (with the smallest steric hindrance ligand) and mononuclear Ce-dtuCy4 (with the largest steric hindrance ligand) were discussed first as representatives. With direct excitation of Ce(III) center via f-d absorption (Supplementary Fig. 4), orange-red and deep-red luminescence originating from 5 d 1 → 4f1 (d-f) transition can be observed for the two complexes. The PL maxima are 640 nm and 725 nm for Ce-dtuMe4 and Ce-dtuCy4 (Fig. 3b), respectively. Considering 4 f is nearly fixed, the PL maximum difference between the two complexes (85 nm, about 1.83×103 cm-1) arises from the different average Ce-S bond lengths and coordination geometries (Ce-dtuMe4: 2.96(8) Å, dodecahedron; Ce-dtuCy4: 2.83(6) Å, twisted trigonal prism) in the two complexes, which result in distinct impact on 5 d centroid shift and/or ligand-field splitting. We can draw on models from inorganic Ce3+ phosphors to analyze the impact of 5 d centroid shift and ligand-field splitting on the redshift (Supplementary Fig. 5). The centroid shift (εC) in Ce-dtuMe4 and Ce-dtuCy4 can be roughly compared using the following equation42 (Eq. 1):

Where N represents the coordination numbers, which are 8 and 6 for Ce-dtuMe4 and Ce-dtuCy4, respectively; αsp is the spectroscopic polarizability related to coordination atoms and can be seen as identical in the two complexes; Reff is treated as the average coordination bond length in the two molecular complexes. Thus, εC(Ce-dtuCy4)/εC(Ce-dtuMe4) ≈ 0.985, indicating a similar centroid shift on 5 d in the two complexes. The ligand-field splitting is directly related to coordination geometry, and the splitting energy in a twisted trigonal prism (Ce-dtuCy4) is similar to that in an octahedron42, which is about 1.26 times higher than that in a dodecahedron (Ce-dtuMe4)43. That is, larger splitting energy instead of centroid shift on 5 d finally lowers the lowest 5 d energy level in Ce-dtuCy4, resulting in a redshifted emission maximum to 725 nm. To further elucidate the essence of the d-f transition, Gaussian peak fitting of the PL spectra was conducted. As shown in Supplementary Fig. 6, the emission peak of both complexes can be fitted into double peaks with an energy difference of about 1.8 × 103 cm−1, which corresponds to the transition from the 5 d excited state to two 4 f sublevels, 2F5/2 and 2F7/2. Additionally, the excited-state lifetimes in solid-powder state are determined to be 37 ns and 53 ns for Ce-dtuMe4 and Ce-dtuCy4 (Fig. 3c), respectively. We are also interested in the luminescence efficiency of these emitters, and their PLQYs are measured to be 22% and 31%. That is, Ce(III) complexes not only show high efficiency with short-wavelength emission as works of literature reported4,5,8,23,44, but also exhibit great performance in the red to deep-red region with rational molecule design.

a Illustration of the difference in chemical structures and photophysical properties between dinuclear and mononuclear complexes (The images are the four complexes in solid-powder state under ambient light and excitation with 365 nm from R = Me, Et to R = iPr, Cy). b Emission spectra of the four complexes and c PL decay spectra of the three complexes at 293 K; d Emission spectra and e PL decay spectra of the four complexes at 77 K. Excitation wavelength: Ce-dtuMe4: 450 nm; Ce-dtuEt4: 500 nm; Ce-dtuiPr4: 490 nm; Ce-dtuCy4: 500 nm. The excitation source used for PL decay measurement is EPL475.

For the other two complexes, Ce-dtuEt4 and Ce-dtuiPr4, we will briefly discuss their PL properties. Upon direct f-d excitation, Ce-dtuEt4 exhibits weak red emission with PL maxima of 670 nm, and the excited-state lifetime cannot be determined reliably due to the weak luminescence. The Gaussian peak fitting indicates two emission peaks centered at 630 nm and 725 nm (Supplementary Fig. 6), which is similar to the result of Ce-dtuMe4. The more asymmetric molecular structure and higher average atomic displacement parameters (ADP) of sulfur atoms (ADP = 0.0266) compared with its methyl analog (ADP = 0.0245) indicate a lower rigidity and open up more vibrational quenching channels45,46, which may account for the low efficiency. Ce-dtuiPr4 just displays nearly identical PL maxima at 725 nm to its Ce-dtuCy4 analog, suggesting an external alkyl group has little impact on the 5 d energy difference. However, the smaller steric hindrance of substituents makes Ce-dtuiPr4 easier for Ce(III) centers to interact with the external environment, as well as its slightly lower PLQY of 20% compared with Ce-dtuCy4, and as discussed before in other literature using guanidinate as anion ligands23, a more rigid molecular skeleton brings smaller stokes shift and higher efficiency when comparing Ce-dtuiPr4 and Ce-dtuCy4.

At 77 K, the PL spectra of the four complexes in solid-powder state can be well divided into two categories: Dinuclear Ce-dtuMe4 and Ce-dtuEt4 exhibit orange-red emission, and mononuclear Ce-dtuiPr4 and Ce-dtuCy4 show deep-red emission. Between the dinuclear complexes, both share highly resembled PL maxima (Fig. 3d), and a more obvious double-peak emission was observed in Ce-dtuEt4. According to Gaussian peak-fitting, the PL maxima of the 5 d → 4 f (2F5/2) peak are similar in these two complexes (Me: 632 nm; Et: 644 nm) (Supplementary Fig. 7). In addition, the excited-state lifetimes are determined to be 85 ns and 74 ns for the two complexes, respectively. Mononuclear Ce-dtuiPr4 and Ce-dtuCy4 display almost the same PL spectra with emission maxima of 725 nm. Meanwhile, the excited-state lifetimes of the two complexes at 77 K are slightly shorter than those of the dinuclear complexes, with values of 58 ns and 70 ns, respectively (Fig. 3e).

Stability in solution state

The UV-vis absorption spectra (Supplementary Fig. 8) of only three Ce-dtuR4 (R = Et, iPr, and Cy) complexes were conducted in PhMe solution since Ce-dtuMe4 is insoluble in common organic solvents. The absorption spectra display similar absorption characteristics in these complexes with a strong absorption band ascribed to ligand transition and one weak f-d band (spin- and parity-allowed 4f1 → 5d1) of Ce(III). The molar extinction coefficients (ε) of these f-d bands are about 3 × 102 M−1·cm−1, as the other literature reported6,47. Among them, the f-d bands are within different positions: Absorption of the dinuclear Ce-dtuEt4 lies in the range of 420–450 nm, as it is covered by strong ligand absorption; the other two mononuclear complexes exhibit apparent redshifted f-d maxima of 480 nm and 500 nm for Ce-dtuiPr4 and Ce-dtuCy4, respectively.

In addition, to ensure the reliability of the PL data for these complexes in the solution state, we monitored the change of the UV-vis absorption spectra of the three soluble complexes Ce-dtuR4 (R = Et, iPr, and Cy) during an 8 h period. As shown in Fig. 4a–c, the intensity of the f-d absorption peaks in all three complexes remained nearly unchanged within 3 h, and exhibits slight degradation after 8 h. The absorbance was selected at the f-d absorption maxima for each complex, and the detailed data are listed in Supplementary Table 3. It’s clear to see that Ce-dtuCy4 is the easiest to degrade. Considering the measurements in solution can be conducted within 1 h, the above results indicate the complexes are stable enough for a short-period PL measurement using freshly prepared solutions.

Subsequently, the redox behaviors of these complexes in solution were characterized by studying their cyclic voltammetry (CV) in DCM solutions (10−3 M), as the electrolyte [nBu4N][PF6] is not soluble in PhMe. The three complexes exhibit one oxidation peak near 0 V and one at about 0.80 V vs ferrocene redox couple (Fc0/+) (Supplementary Fig. 9), indicating their similar redox behaviors. Meanwhile, both oxidations are irreversible for the three complexes according to the cyclic voltammograms. Among the series, Ce-dtuEt4 becomes the easiest to oxidize, as the first oxidation peak occurs at about −0.13 V, while those of the other two complexes are 0.16 V (Ce-dtuiPr4) and 0.00 V (Ce-dtuCy4) vs Fc0/+, respectively.

Photophysical properties in solution state

The steady PL spectra of the three complexes in PhMe (10−3 M) at 293 K were also measured. With direct f-d excitation (Supplementary Fig. 10a), all three complexes share nearly identical emissions with PL maxima at about 725 nm (Fig. 5a, Supplementary Fig. 11). In addition, the PL spectra remain unchanged even with different excitation wavelengths (Supplementary Fig. 12), indicating a single luminescence species. It should be noted that Ce-dtuiPr4 and Ce-dtuCy4 show similar yet more broadened emission spectra as their solid-powder samples, while Ce-dtuEt4 shows a different emission spectrum as its solid-powder sample with a significantly redshifted emission maximum, i.e., from 670 nm to 725 nm. The highly similar PL spectra among the three complexes indicate that they may have the same coordination environment for Ce(III) in solution. As the emission maxima remain identical in Ce-dtuiPr4 and Ce-dtuCy4 from solid-powder to solution state, it’s plausible to ascribe the existence of mononuclear species of Ce-dtuEt4 in PhMe solution too. 1H nuclear magnetic resonance (NMR) spectra of the three complexes in deuterated toluene (tol-d8) were measured. Besides the peaks arising from the residual solvents in the glovebox (Supplementary Fig. 13), all three complexes show only one group of signals for the corresponding alkyl group (Supplementary Figs. 14–16), indicating that the complex is highly symmetric or undergoes rapid ligand exchange. Furthermore, diffusion ordered NMR spectroscopy (DOSY) is conducted in tol-d8 to derive the hydrodynamic radius (rH) of the three complexes, thereby determining the mononuclear nature. As shown in Supplementary Figs. 17–19, the paramagnetism of Ce(III) brings difficulty for distinguishing specific peaks in the NMR spectra, while the self-diffusion coefficient (Dt) can be obtained after the DOSY transform. Thus, the values of rH were calculated using the Stokes-Einstein Equation (Eq. 2):

Where kB and T represent the Boltzmann constant and temperature, respectively; η is the viscosity of the deuterated solvent at measuring temperature (0.554 mPa·s for PhMe at 298 K48,49). Thus, the rH are determined to be 5.60 Å, 6,31 Å, and 7.89 Å for Ce-dtuEt4, Ce-dtuiPr4, and Ce-dtuCy4, respectively. Compared with the results obtained from crystal structure (9.61 Å, 7.63 Å, and 9.03 Å determined by the distance from the center of gravity to the farthest atom), the obvious radius difference between Ce-dtuEt4 in solution and crystal (dinuclear structure), as well as the almost identical values of Ce-dtuEt4 and Ce-dtuiPr4 in solution strongly support the mononuclear structure of Ce-dtuEt4 in PhMe solution (Fig. 5b, c), as ethyl and iso-propyl contribute similarly to the radius. That is to say, Ce-dtuEt4 experienced a chemical structure conversion from dinuclear to mononuclear when dissolved in PhMe, and the 725 nm emission in solution originates from the mononuclear structure species.

a Emission spectra in PhMe solution at 293 K. b Molecular radius of the three complexes obtained from the crystal structure and DOSY experiment. c Schematic diagram of the molecular radius of Ce-dtuEt4 corresponding to mononuclear and dinuclear structures in the crystal structure (The radius of mononuclear Ce-dtuEt4 is estimated by the distance from the farthest point to the Ce(III) center). Emission spectra of d Ce-dtuEt4, e Ce-dtuiPr4, and f Ce-dtuCy4 in PhMe solution at 77 K and 293 K under 350 nm excitation. g Illustration of the difference in photophysical properties of Ce-dtuR4 in PhMe solution via mononuclear-dinuclear conversion. DOSY: diffusion-ordered NMR spectroscopy. PhMe: toluene.

The excited-state lifetimes of these complexes in PhMe (10-3 M) at 293 K are determined to be 3.3 ns, 51 ns, and 60 ns for Ce-dtuEt4, Ce-dtuiPr4, and Ce-dtuCy4 (Supplementary Fig. 10b), respectively. The scale in tens of nanoseconds with mono-exponential decay behavior reveals the d-f transition essence of the Ce(III) emitters in PhMe solution. We are also interested in the luminescence efficiency of these deep-red emitters in PhMe solution, and the PLQYs of Ce-dtuEt4, Ce-dtuiPr4, and Ce-dtuCy4 are measured to be 1%, 17%, and 27%, slightly lower than the values in solid-powder state. As a supplement, the radiative decay rate (kr) and the non-radiative decay rate (knr) could also be derived using the equations kr = ФPL/τ and 1/τ = kr + knr, and the photophysical data are summarized and listed in Table 2 for comparison in both solid-powder and solution states. It’s clear to see a significantly faster knr in Ce-dtuEt4 compared with the other two complexes in PhMe solutions, which may be due to the ethyl group with less steric hindrance and less rigidity, leading to an easier access for the solvent to interact with the Ce(III) center.

We further measured the PL spectra of the three complexes in PhMe solution at 77 K for deeper insight. For Ce-dtuEt4, a large blueshift compared to the spectrum at 293 K is observed, showing a PL maximum at 600 nm under 350 nm excitation (Fig. 5d). The mono-exponential decay with an excited-state lifetime of 103 ns supports the d-f essence of the emission band. Different excitation wavelengths, such as 365 nm, 425 nm, and 490 nm, were also used, but no emission band centered at 725 nm was observed (Supplementary Fig. 20). In this context, considering the mono- and di-nuclear structures could be tuned by the steric hindrance of the alkyl group, we suggest the coordination structure of Ce-dtuEt4 in PhMe solution is temperature-dependent as well, and low temperature could stabilize the dinuclear structure to induce high energy emission (600 nm).

The low-temperature behavior of the other two complexes, Ce-dtuiPr4 and Ce-dtuCy4, differs from dtuEt4. Under 350 nm excitation, Ce-dtuiPr4 exhibits similar PL spectra with Ce-dtuEt4, while a difference lies in the tail at 800–1000 nm in the spectrum (Fig. 5e). Under 500 nm excitation, the 725 nm emission emerged as the main component (Supplementary Fig. 21), which indicates the existence of two luminescence species (600 nm and 725 nm) under the experiment condition and explains that the aforementioned tail is the 725 nm emission. Compared to the excitation-independent emission of Ce-dtuEt4 centered at 600 nm, the excitation-dependent emission of Ce-dtuiPr4 indicates the concurrent existence of mononuclear and dinuclear structures at 77 K. Subsequently, for Ce-dtuCy4 with larger steric hindrance, the 600 nm emission just manifests as a small band, and 725 nm emission becomes dominant under 350 nm excitation (Fig. 5f), implying the fact that Ce-dtuCy4 is more difficult to become a dinuclear structure. Furthermore, monitoring of both emissions at 600 nm and 725 nm yields two different excitation spectra and excited-state lifetimes as well (Supplementary Fig. 22), which strongly supports the existence of two luminescent species in the PhMe solutions of both Ce-dtuiPr4 and Ce-dtuCy4 at 77 K. Therefore, through the complexes from Ce-dtuEt4 to Ce-dtuiPr4 and Ce-dtuCy4, a gradually increased steric hindrance yields complete to lower 600 nm component (i.e. dinuclear structure component), indicating the structure conversion is also temperature-dependent in solution (Fig. 5g).

Discussion

In summary, deep-red Ce(III) emitters with PL maxima exceeding 700 nm has been synthesized and characterized using S-coordinating dithiobiuret ligands. By applying different steric hindrances, dinuclear and mononuclear Ce(III) complexes were obtained with red and deep-red emissions, respectively, due mainly to different splitting energies rather than the centroid shift of the 5 d orbital. Among them, the best two complexes, dinuclear Ce-dtuMe4 and mononuclear Ce-dtuCy4, exhibit red emission centered at 640 nm and deep-red emission centered at 725 nm with PLQY of 22% and 31%, respectively. The exciting result exceeds the common understanding of the emission color of Ce(III) compounds, which may raise new attention in designing red to near-infrared d-f emitters. Furthermore, temperature-dependent PL spectra suggest different chemical structure conversions between monomer and dimer in these Ce(III) complexes, revealing interesting coordination chemistry among these unique complexes. This work not only demonstrates the pioneering use of S-coordinating ligands in lanthanide Ce(III) complexes, but also reveals the huge potential of Ce(III) to construct highly efficient deep-red, even near-infrared emitters.

Methods

General information

All synthesis experiments were performed under a nitrogen atmosphere. All chemical reagents used in the synthesis process were commercially available and were used as received unless otherwise mentioned. The synthesis and purification of Ce(III) complexes were carried out in a glove box. Ce(OTf)3 was dried under vacuum at 180 °C prior to use. The solvents used to synthesize the complexes were specially treated: THF, PhMe, tol-d8, and n-hexane were dried over sodium/benzophenone and freshly distilled under an argon atmosphere; DCM and MeCN were dried over calcium hydride and freshly distilled under an argon atmosphere. Powder-state NaH was prepared by washing commercially available 60% NaH with n-hexane (3 × 20 mL) in a glovebox. All glasswares were oven-dried at 120 °C for at least 1 h before use.

1H NMR spectra were recorded on a Bruker-400 MHz NMR spectrometer. Tetramethylsilane (TMS) was used as an internal reference for the chemical shift correction, where δ(TMS) equals 0. The 13C NMR spectra and DOSY NMR spectra were recorded on a Bruker-500 MHz NMR spectrometer. Electrospray ionization mass spectra (ESI-MS) were performed in negative ion mode on a Bruker Apex IV Fourier transform ion cyclotron resonance mass spectrometer. The infrared spectrum (IR) of the product (KBr pellets) was recorded using a Fourier transform infrared spectrometer (Nicolet Is50, ThermoFisher) in the range of 400–4000 cm−1 the results are shown in Supplementary Figs. 23–24. X-ray photoelectron spectroscopy was performed on an AXIS Supra X-ray photoelectron spectrometer.

Synthesis of thiocarbamoyl chloride

Synthesis of Et2NC(S)Cl

To an orange solution of thiophosgene (11.50 g, 0.100 mol) in 50 mL THF in an ice-salt bath, Et2NH (14.63 g, 0.200 mol) in 50 mL THF was added dropwise over 1 h, the amine hydrochloride precipitated immediately, and the mixture became cloudy. After the addition, the mixture was stirred at room temperature for a further 45 min. The amine hydrochloride was filtered off and washed with 20 mL THF. The brown filtrate was combined, and the solvent was removed in vacuo to afford a brown solid, which was washed with n-hexane (3 × 20 mL) to give pale-brown to off-white crystalline powder. Yield: 9.56 g (63.1%). 1H NMR (400 MHz, CDCl3): δ 3.87 (dq, J = 61.6, 7.1 Hz, 4H), 1.33 (td, J = 7.1, 2.8 Hz, 6H); 13C{1H} NMR (126 MHz, CDCl3): δ 174.12, 50.30 (d, J = 36.0 Hz), 12.98, 10.95; IR (ν, KBr pellet): 2977, 2935, 2856, 2820, 2038, 1668, 1505, 1457, 1443, 1425, 1354, 1275, 1199, 1147, 1094, 1067 cm−1.

Synthesis of i Pr 2 NC(S)Cl

A similar procedure of synthesis of Et2NC(S)Cl was used with thiophosgene (8.70 g, 75.7 mmol) in 70 mL THF and iPr2NH (15.20 g, 150 mmol) in 50 mL THF to give pale-brown crystalline powder. Yield: 9.82 g (72.9%). 1H NMR (400 MHz, CDCl3): δ 3.47–3.33 (m, J = 6.4 Hz, 2H), 1.50 (d, J = 6.5 Hz, 12H); 13C{1H} NMR (126 MHz, CDCl3): δ 47.50, 19.28; IR (ν, KBr pellet): 2973, 2934, 2835, 2759, 2721, 1668, 1624, 1464, 1399, 1378, 1320, 1275, 1187, 1141, 1117, 1026 cm−1.

Synthesis of Cy2NC(S)Cl

A similar procedure of synthesis of Et2NC(S)Cl was used with thiophosgene (5.75 g, 50.0 mmol) in 50 mL THF and Cy2NH (18.1 g, 100 mmol) in 50 mL THF to give off-white crystalline powder. Yield: 8.02 g (61.7%). 1H NMR (400 MHz, CDCl3): δ 2.55 (s, 2H), 1.75 (d, J = 72.6 Hz, 10H), 1.48–1.25 (m, 6H), 1.16 (q, J = 13.0 Hz, 4H); 13C{1H} NMR (126 MHz, CDCl3):δ 62.70, 30.79, 29.36 (d, J = 15.7 Hz), 26.37 (d, J = 41.0 Hz), 24.96 (d, J = 40.0 Hz); IR (ν, KBr pellet): 2932, 2854, 1476, 1441, 1371, 1346, 1312, 1268, 1242, 1162, 1090, 997, 949, 898, 871 cm−1.

Synthesis of 1,1,5,5-tetra-substituted dithiobiuret ligand

Synthesis of [Me2NC(S)]2NH (HdtuMe4)

To a mixture of Me2C(S)Cl (3.78 g, 30.0 mmol) and KSCN (2.95 g, 30.3 mmol) was added 60 mL MeCN. The reaction mixture was heated and refluxed for 3 h. After cooling down, the yellow mixture was filtered. The filtered KCl was washed with 10 mL MeCN, and the filtrate was combined. Then 2 M Me2NH in THF (16.0 mL, 32.0 mmol) was added to the yellow filtrate of Me2NC(S)NCS, and the solution was stirred overnight. The solvent was removed in vacuo, and the residue was washed with Et2O (3 × 20 mL) and PhMe (20 mL) to afford a pale-brown solid. Yield: 4.01 g (69.9%). 1H NMR (400 MHz, CDCl3): δ 3.35 (m, 12H); 13C{1H} NMR (126 MHz, CDCl3): δ 181.44, 43.05; ESI-MS (m/z) [M-H]- calcd. for C6H12N3S2, 190.05; found, 190.05; IR (ν, KBr pellet): 3218, 2930, 1546, 1466, 1386, 1289, 1261, 1219, 1153, 1105, 742 cm−1.

Synthesis of [Et2NC(S)]2NH (HdtuEt4)

A similar procedure of synthesis of HdtuMe4 was used with Et2C(S)Cl (4.55 g, 30.0 mmol) and KSCN (2.91 g, 30.0 mmol) in 50 mL MeCN. Et2NH (4.20 g, 57.4 mmol) was added to the yellow filtrate of Et2NC(S)NCS, and the reaction was stirred overnight. The solvent was removed in vacuo, and the obtained brown solid was washed with a small amount of MeCN (3 × 1 mL) to afford an off-white powder. The filtrate can be further concentrated to yield more crystalline products. Yield: 2.52 g (34.0%). 1H NMR (400 MHz, CDCl3): δ 4.04–3.49 (m, 8H), 1.28 (t, J = 7.2 Hz, 12H); 13C{1H} NMR (126 MHz, CDCl3): δ 180.01, 46.57, 12.56; ESI-MS (m/z) [M-H]- calcd. for C10H20N3S2, 246.11; found, 246.11; IR (ν, KBr pellet): 3203, 2974, 2931, 2871, 1533, 1503, 1430, 1346, 1266, 1228,1192, 1123, 1073, 1011 cm−1.

Synthesis of [iPr2NC(S)]2NH (HdtuiPr4)

A similar procedure of synthesis of HdtuMe4 was used with iPr2C(S)Cl (3.49 g, 20.0 mmol) and KSCN (1.95 g, 20.0 mmol) in 50 mL MeCN. iPr2NH (4.05 g, 40.0 mmol) was added to the yellow filtrate of iPr2NC(S)NCS, and white HdtuiPr4 precipitated with stirring. The mixture was filtered after stirring overnight, and the obtained solid was washed with MeCN (3 × 5 mL) to afford an off-white powder. The filtrate can be further concentrated to yield more crystalline products. Yield: 4.99 g (82.1%). 1H NMR (400 MHz, CDCl3): δ 2.92 (hept, J = 6.3 Hz, 4H), 1.05 (d, J = 6.2 Hz, 24H); 13C{1H} NMR (126 MHz, CDCl3): δ 45.46, 22.95; ESI-MS (m/z) [M-H]- calcd. for C14H28N3S2, 302.17; found, 302.17; IR (ν, KBr pellet): 2970, 2931, 2870, 1999, 1569, 1489, 1456, 1369, 1341, 1271, 1250, 1227, 1209, 1147, 1099, 1035 cm−1.

Synthesis of [Cy2NC(S)]2NH (HdtuCy4)

A similar procedure of synthesis of HdtuMe4 was used with Cy2C(S)Cl (3.90 g, 15.0 mmol) and KSCN (1.46 g, 15.0 mmol) in 50 mL MeCN. Cy2NH (3.62 g, 20.0 mmol) was added to the yellow filtrate of Cy2NC(S)NCS, and white HdtuCy4 precipitated with stirring. The mixture was filtered after stirring overnight, and the obtained solid was washed with MeCN (3 × 15 mL) to afford an off-white powder. Yield: 5.25 g (75.4%). 1H NMR (400 MHz, CDCl3): δ 2.55 (tt, J = 10.6, 3.8 Hz, 4H), 1.95–1.54 (m, 16H), 1.48–0.90 (m, 24H); 13C{1H} NMR (126 MHz, CDCl3): δ 53.12, 34.23, 26.17, 25.31; ESI-MS (m/z) [M-H]- calcd. for C26H44N3S2, 462.30; found, 462.30; IR (ν, KBr pellet): 2930, 2851, 1587, 1464, 1450, 1367, 1343, 1271, 1213, 1180, 1123, 1093, 992, 894 cm-1.

Synthesis of the cerium complex

Synthesis of Ce2[N(C(S)NMe2)2]6

HdtuMe4 (286 mg, 1.50 mmol) was dissolved in 15 mL MeCN and added to the solution of Ce[N(SiMe3)2]3 (330 mg, 0.53 mmol) in 15 mL MeCN. Orange-yellow powder precipitated immediately. The reaction mixture was stirred for 1 day at room temperature and then filtered. The filtered solid was washed with MeCN (3 × 10 mL) and THF (2 × 10 mL) to give an orange-yellow solid. Yield: 267 mg (54.9%) for powder sample. The single crystals were obtained by slowly diffusion the MeCN solution of Ce[N(SiMe3)2]3 into the MeCN solution of HdtuMe4. Analysis (calcd., found for C36H72N18S12Ce2 + 0.5C4H8O, M = 1458.10 g/mol): C (31.30, 31.13), H (5.25, 5.05), N (17.29, 17.32).

Synthesis of Ce2[N(C(S)NEt2)2]6

To the mixture of HdtuEt4 (741 mg, 3.00 mmol) and NaH (72 mg, 1.50 mmol) was added 15 mL THF to prepare the ligand salt in situ. Then the yellow ligand slurry was added to a slurry of Ce(OTf)3 (587 mg, 1.00 mmol) in 15 mL THF. The colorless slurry turned to orange-yellow immediately, and the reaction mixture was stirred for 1 day at room temperature. The solvent was removed in vacuo, and the residue was extracted with 25 mL PhMe and filtered. The solvent of the orange-red filtrate was removed to give an orange solid. Yield: 589 mg (67.0%) for powder sample. The single crystals were obtained by slowly evaporating the mixed solution of THF and n-hexane. Analysis (calcd., found for C60H120N18S12Ce2, M = 1758.68 g/mol), C (40.97, 40.74), H (6.88, 6.81), N (14.34, 14.05).

Synthesis of Ce[N(C(S)NiPr2)2]3

To the mixture of HdtuiPr4 (910 mg, 3.00 mmol) and NaH (72 mg, 3.00 mmol) was added 15 mL THF to prepare ligand salt in situ. Then the ligand slurry was added to a slurry of Ce(OTf)3 (587 mg, 1.00 mmol) in 15 mL THF. The colorless slurry turned orange immediately, and the reaction mixture was stirred for 1 day at room temperature. The solvent was removed in vacuo, and the residue was extracted with 25 mL n-hexane and filtered. The solvent of the orange-red filtrate was removed again to give a pink solid, which is no longer easily soluble in n-hexane. The solid was washed with n-hexane (3 × 10 mL) to give a coral-red to peach-colored powder. Yield: 312 mg (29.8%) for powder sample. The single crystals were obtained by slowly evaporating the mixed solution of DCM and n-hexane. Analysis (calcd., found for C42H84N9S6Ce, M = 1047.69 g/mol), C (48.15, 48.26), H (8.08, 8.07), N (12.04, 11.90).

Synthesis of Ce[N(C(S)NCy2)2]3

A similar procedure to above was used with HdtuCy4 (696 mg, 1.50 mmol), NaH (54 mg, 2.25 mmol), and Ce(OTf)3 (293 mg, 0.50 mmol). The residue from THF was extracted with 25 mL PhMe and filtered. The solvent of the orange-red filtrate was then removed in vacuo. The residue was washed with a 10 mL mixed solution of DCM and n-hexane (1:4 in volume ratio) to give a magenta powder. Yield: 475 mg (60.5%) for powder sample. The single crystals were obtained by slowly evaporating the mixed solution of DCM and n-hexane. Analysis (calcd., found for C78H132N9S6Ce + 0.5CH2Cl2, M = 1570.91 g/mol), C (60.01, 60.25), H (8.53, 8.74), N (8.03, 7.49).

Single-crystal X-ray crystallography

The single-crystal X-ray diffraction data were obtained with a Rigaku007HF Saturn CCD Diffractometer utilizing Mo Kα radiation with a wavelength of 0.71073 Å via the CrystalClear software package. All structures were solved by the intrinsic phasing method with SHELXT5 and refined by full-matrix least-squares procedures utilizing SHELXL within the Olex2 crystallographic software package50. The PXRD data were simulated using the SCXRD data of the corresponding complexes via the CCDC Mercury software package51. The molecular structures of the complexes using ORTEP-style are shown in Supplementary Fig. 25.

Spectral measurements

All the solutions used for measurement were freshly prepared to avoid the influence of degradation. The UV-vis absorption spectra were obtained from a Shimadzu UV-3100 spectrometer. Steady/transient photoluminescence spectra were recorded on an Edinburgh Analytical Instruments FLS980 spectrophotometer equipped with a pulsed laser (Edinburgh Ltd. Co.). The spectral tests of solid-powder complexes at room temperature were carried out by paraffin encapsulation between two quartz plates, and the solutions were protected by capped cuvettes under a N2 atmosphere. The spectral tests of samples at 77 K were conducted in a quartz NMR tube equipped with caps in a Dewar flask. The photoluminescence quantum yields (PLQYs) were measured by an absolute PLQY measurement system on C9920-02 from Hamamatsu Company.

Cyclic voltammetric measurements

Cyclic voltammetry was performed in the range of −1.8 V to 1.8 V, at 0.1 V/s scan rate in DCM containing 0.1 M [nBu4N][PF6] as electrolyte. For internal reference, ferrocene (Fc) was added after scanning the solution of the complex.

Data availability

The main data supporting the findings of this study are shown within the article and its Supplementary Figs. and are provided in the Supplementary Information/Source Data file. The source data underlying Figs. 3–5, Supplementary Figs. 1–2, Supplementary Fig. 4, Supplementary Figs. 8–10, Supplementary Fig. 12, and Supplementary Figs. 20–22 are provided as a Source Data file. Source data are provided with this paper. Crystallography data have been deposited at the Cambridge Crystallographic Data Centre (CCDC) under deposition numbers CCDC 2401372 (Ce-dtuMe4), 2401373 (Ce-dtuEt4), 2401374 (Ce-dtuCy4), and 2401375 (Ce-dtuiPr4), and are publicly available as of the date of publication. Copies of the data can be obtained free of charge via https://www.ccdc.cam.ac.uk/structures/. All data are available from the corresponding author upon request. Source data are provided with this paper.

References

Yaroshevsky, A. A. Abundances of chemical elements in the Earth’s crust. Geochem. Int. 44, 48–55 (2006).

Wang, L. et al. Review on the electroluminescence study of lanthanide complexes. Adv. Opt. Mater. 7, 1801256 (2019).

Gao, S., Cui, Z. & Li, F. Doublet-emissive materials for organic light-emitting diodes: exciton formation and emission processes. Chem. Soc. Rev. 52, 2875–2885 (2023).

Fang, P. et al. Delayed doublet emission in a cerium(III) complex. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 62, e202302192 (2023).

Fang, P. et al. Lanthanide cerium (III) tris (pyrazolyl) borate complexes: efficient blue emitters for doublet organic light-emitting diodes. ACS Appl. Mater. Inter. 13, 45686–45695 (2021).

Yan, W. et al. Highly efficient heteroleptic cerium (III) complexes with a substituted pyrazole ancillary ligand and their application in blue organic light-emitting diodes. Inorg. Chem. 60, 18103–18111 (2021).

Yan, W. et al. Deep-blue emitting cerium (III) complexes with tris (pyrazolyl) borate and triflate ligandˍ. Dalton Trans. 51, 3234-3240 (2022).

Yin, H., Carroll, P. J., Anna, J. M. & Schelter, E. J. J. J. O. T. A. C. S. Luminescent Ce (III) complexes as stoichiometric and catalytic photoreductants for halogen atom abstraction reactions. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 137, 9234–9237 (2015).

Yin, H., Carroll, P. J., Manor, B. C., Anna, J. M. & Schelter, E. J. J. J. O. T. A. C. S. Cerium photosensitizers: structure–function relationships and applications in photocatalytic aryl coupling reactions. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 138, 5984–5993 (2016).

Du, H. et al. Electrohydrodynamically printed d–f transition cerium(III) complex. J. Phys. Chem. Lett. 15, 874–879 (2024).

Wang, L. et al. Deep-blue organic light-emitting diodes based on a doublet d–f transition cerium (III) complex with 100% exciton utilization efficiency. Light Sci. Appl 9, 1–9 (2020).

Zhao, Z. et al. Efficient rare earth cerium (III) complex with nanosecond df emission for blue organic light-emitting diodes. Natl. Sci. Rev. 8, nwaa193 (2020).

Fang, P. et al. Lanthanide complexes with d-f transition: New emitters for single-emitting-layer white organic light-emitting diodes. Light Sci. Appl 12, 170 (2023).

Ueda, J. & Tanabe, S. Review of luminescent properties of Ce3+-doped garnet phosphors: New insight into the effect of crystal and electronic structure. Opt. Mater. X 1, 100018 (2019).

Blasse, G. & Bril, A. Investigation of some Ce3+-activated phosphors. J. Chem. Phys. 47, 5139–5145 (2004).

Wen, Z. et al. Optimizing energy transfer: suppressing Cs2ZnCl4 self-trapped states and boosting Ce3+ ion luminescence efficiency. Laser Photonics Rev. 18, 2400525 (2024).

Wang, Q. et al. Ultraviolet emission from cerium-based organic-inorganic hybrid halides and their abnormal anti-thermal quenching behavior. Adv. Funct. Mater. 33, 2303399 (2023).

Suta, M. et al. Bright photoluminescence of [{(Cp)2Ce(μ-Cl)}]2: a valuable technique for the determination of the oxidation state of cerium. Chem. Asian J. 13, 1038–1044 (2018).

You, S., Li, S., Jia, Y. & Xie, R.-J. Interstitial site engineering for creating unusual red emission in La3Si6N11:Ce3+. Chem. Mater. 32, 3631–3640 (2020).

Blasse, G., Dirksen, G., Sabbatini, N. & Perathoner, S. J. I. C. A. Photophysics of Ce3+ cryptates. Inorg. Chim. Acta 133, 167–173 (1987).

Yu, T. et al. Ultraviolet electroluminescence from organic light-emitting diode with cerium (III)–crown ether complex. Solid·State Electron 51, 894–899 (2007).

Zheng, X. L. et al. Bright blue-emitting Ce3+ complexes with encapsulating polybenzimidazole tripodal ligands as potential electroluminescent devices. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 46, 7399–7403 (2007).

Qiao, Y. et al. Understanding and controlling the emission brightness and color of molecular cerium luminophores. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 140, 4588–4595 (2018).

Yin, H., Carroll, P. J., Anna, J. M. & Schelter, E. J. Luminescent Ce(III) complexes as stoichiometric and catalytic photoreductants for halogen atom abstraction reactions. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 137, 9234–9237 (2015).

Guo, R. et al. Complexes of Ce (III) and bis (pyrazolyl) borate ligands: Synthesis, structures, and luminescence properties. Inorg. Chem. 61, 14164–14172 (2022).

Fang, P. et al. Delayed doublet emission in a cerium (III) complex. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 62, e202302192 (2023).

Hazin, P. N., Bruno, J. W. & Brittain, H. G. Luminescence spectra of a series of cerium(III) halides and organometallics. Probes of bonding properties using 4f-5d excited states. Organometallics 6, 913–918 (1987).

Rausch, M. D. et al. Synthetic, X-ray structural and photoluminescence studies on pentamethylcyclopentadienyl derivatives of lanthanum, cerium and praseodymium. Organometallics 5, 1281–1283 (1986).

Youssef, H. et al. Red emitting cerium(III) and versatile luminescence chromaticity of 1D-coordination polymers and heterobimetallic Ln/AE pyridylpyrazolate complexes. Z. Anorg. Allg. Chem. 648, e202200295 (2022).

Youssef, H., Sedykh, A. E., Becker, J., Taydakov, I. V. & Müller-Buschbaum, K. 3-(2-Pyridyl)pyrazole based luminescent 1D-coordination polymers and polymorphic complexes of various lanthanide chlorides including orange-emitting cerium(III). Inorganics 10, 254 (2022).

Chow, P. C. Y. & Someya, T. Organic photodetectors for next-generation wearable electronics. Adv. Mater. 32, 1902045 (2020).

Wu, W. et al. Characterization and properties of a Sr2Si5N8:Eu2+-based light-conversion agricultural film. J. Rare Earths 38, 539–545 (2020).

Yang, C. et al. Recent advances in light-conversion phosphors for plant growth and strategies for the modulation of photoluminescence properties. Nanomaterials 13, 1715 (2023).

Pu, Y. et al. Sulfur-locked multiple resonance emitters for high performance orange-red/deep-red OLEDs. Nat. Commun. 16, 332 (2025).

Sudhakar, P., Gupta, A. K., Cordes, D. B. & Zysman-Colman, E. Thermally activated delayed fluorescence emitters showing wide-range near-infrared piezochromism and their use in deep-red OLEDs. Chem. Sci. 15, 545–554 (2024).

Li, G., Tian, Y., Zhao, Y. & Lin, J. Recent progress in luminescence tuning of Ce3+ and Eu2+-activated phosphors for pc-WLEDs. Chem. Soc. Rev. 44, 8688–8713 (2015).

Dorenbos, P. Lanthanide 4f-electron binding energies and the nephelauxetic effect in wide band gap compounds. J. Lumin. 136, 122–129 (2013).

Zhang, H., Zhang, J., Ye, R., Xu, S. & Bai, G. Color modulation of cerium sulfide colorant powders through chemical doping engineering. J. Mater. Chem. C. 11, 9215–9222 (2023).

Zhang, H. et al. Impurity doping effects and ecological friendly synthesis of cerium sulfide powders for enhanced chromaticity and color tunability. Ceram. Int. 49, 34090–34096 (2023).

Borkovec, A. B., Oliver, J. E., Chang, S. C. & Brown, R. T. Insect chemosterilants. 10. Substituted dithiobiurets. J. Med. Chem. 14, 772–773 (1971).

Bêche, E., Charvin, P., Perarnau, D., Abanades, S. & Flamant, G. Ce 3d XPS investigation of cerium oxides and mixed cerium oxide (CexTiyOz). Surf. Interface Anal. 40, 264–267 (2008).

Dorenbos, P. 5d-level energies of Ce3+ and the crystalline environment. III. Oxides containing ionic complexes. Phys. Rev. B 64, 125117 (2001).

Wei, Y., Dang, P., Dai, Z., Li, G. & Lin, J. Advances in near-infrared luminescent materials without Cr3+: Crystal structure design, luminescence properties, and applications. Chem. Mater. 33, 5496–5526 (2021).

Guo, R. et al. Luminescent rare earth complexes of Ce3+, Eu2+ and Yb2+ with spiro-bis(pyrazolyl)borate ligands containing C–H···M interactions. J. Rare Earths (2024).

Amachraa, M. et al. Predicting thermal quenching in inorganic phosphors. Chem. Mater. 32, 6256–6265 (2020).

Qi, H. et al. Air stable and efficient rare earth Eu (II) hydro-tris (pyrazolyl) borate complexes with tunable emission colors. Inorg. Chem. Front. 7, 4593–4599 (2020).

Aguirre Quintana, L. M., Jiang, N., Bacsa, J. & La Pierre, H. S. Homoleptic cerium tris(dialkylamido)imidophosphorane guanidinate complexes. Dalton Trans. 49, 14908–14913 (2020).

Harris, K. R., Malhotra, R. & Woolf, L. A. Temperature and density dependence of the viscosity of octane and toluene. J. Chem. Eng. Data 42, 1254–1260 (1997).

Santos, F. J. V. et al. Standard reference data for the viscosity of toluene. J. Phys. Chem. Ref. Data 35, 1–8 (2005).

Dolomanov, O. V., Bourhis, L. J., Gildea, R. J., Howard, J. A. K. & Puschmann, H. OLEX2: a complete structure solution, refinement and analysis program. J. Appl. Crystallogr. 42, 339–341 (2009).

Macrae, C. F. et al. Mercury 4.0: from visualization to analysis, design and prediction. J. Appl. Crystallogr. 53, 226–235 (2020).

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by the National Key R&D Program of China (2021YFB3501800 (Z. Liu), 2023YFB3506901 (Z. Liu), 2021YFB3500400 (Z. Bian), 2022YFB3503700 (Z. Liu), and 2022YFF0710001 (Z. Liu)) and the National Natural Science Foundation of China (U23A20593 (Z. Liu), 22071003 (Z. Liu), 62104013 (Z. Liu), and 92156016 (Z. Liu)).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Jiayin Zheng conducted most of the experiments and wrote the manuscript. Haodi Niu conducted the synthesis of the organic intermediates and measurement of the FT-IR data. Ruoyao Guo and Yujia Li measured the PLQY values. Haodi Niu, Huanyu Liu, Wen Lu, Tianming Zhong, Zuqiang Bian, and Zhiwei Liu revised the manuscript and provided suggestions. All authors discussed the results and contributed to the paper.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Peer review

Peer review information

Nature Communications thanks Feng Liu and the other anonymous reviewer(s) for their contribution to the peer review of this work. A peer review file is available.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Source data

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Zheng, J., Niu, H., Guo, R. et al. Lanthanide cerium(III) complex with deep-red emission beyond 700 nm. Nat Commun 16, 7801 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-025-63226-3

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-025-63226-3

This article is cited by

-

Three-coordinated Ce(III) complexes with long wavelength d–f emissions

Communications Chemistry (2025)