Abstract

Defect engineering plays a pivotal role in materials science, as defects significantly influence material properties. However, achieving precise control over defects in pure organic systems remains a challenge. In this study, we demonstrate the creation of controllable defects in molecular crystals through supersaturated solution-fed seeded self-assembly of two strategically designed molecules. One molecule features 2-(2’-hydroxyphenyl)benzimidazole groups at both ends, enabling the formation of an intramolecular hydrogen bond on one side while leaving the hydrogen bond donors on the other side available for potential intermolecular interactions. When coassembled with a second molecule containing benzimidazole groups capable of continuous intermolecular hydrogen bonding, defects in the hydrogen-bonding network are introduced, resulting in the formation of defects within the resulting two-dimensional cocrystals. The defect density can be precisely tuned by adjusting the molar ratio of the two molecules. Remarkably, these defects exhibit shape-complementary hydrogen bonding with dimethoate enabling high sensitivity and selectivity molecular recognition.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Defect engineering is a powerful strategy for tailoring material properties to meet application-specific requirements, as it enables precise control over defect generation and utilization1,2,3,4,5,6,7,8,9,10,11. This approach has been extensively leveraged in inorganic materials and metal-organic frameworks (MOFs), where their inherent structural stability and thermal resilience allow defect introduction via thermal treatment, ion/electron irradiation, or etching—methods that underpin applications in catalysis, sensing, and thermoelectrics4,5,6,7,8,9,10,11. However, organic materials face significant barriers to defect engineering due to their soft and dynamic frameworks. Conventional post-synthetic approaches, such as thermal processing, are incompatible with these systems, as their structural flexibility and low thermal tolerance often lead to irreversible damage rather than controlled defect formation. Consequently, developing innovative strategies that accommodate the delicate nature of organic crystals—enabling defect regulation without compromising structural integrity—is imperative to unlock their potential for advanced functionalities.

Bottom-up self-assembly offers a promising route to embed defects directly into molecular crystals during synthesis, circumventing the need for post-processing12,13,14,15,16,17,18,19,20,21,22,23,24,25,26,27,28,29,30,31,32,33,34,35,36,37,38. For example, our laboratory recently developed a supersaturated solution-fed seeded growth method34,35,39, which enables the construction of multidimensional cocrystals and heterojunctions. This technique suggests potential for intentional defect incorporation, yet the controlled creation of defects in molecular crystals via living self-assembly remains underexplored. A key challenge lies in designing complementary molecular building blocks: a “host” molecule to establish a crystalline framework and a “defect-inducing” molecule with structural similarity to the host, enabling controlled co-assembly.

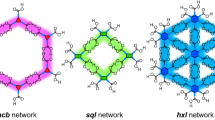

In this work, we introduce a defect engineering strategy in 2D cocrystals through supersaturated solution-fed seeded co-assembly of two custom-designed molecules (1 and 2, Fig. 1). Molecule 2 incorporates 2-(2’-hydroxyphenyl)benzimidazole end groups, which enable intramolecular hydrogen bonding on one side while retaining a hydrogen bond donor on the other side of the benzimidazole moiety for potential intermolecular hydrogen bonding. When coassembled with molecule 1—a molecule equipped with bidirectional hydrogen-bonding sites for robust network formation—the mismatch in hydrogen-bonding linkages creates voids within the 2D cocrystals. By modulating the molar ratio of 1 to 2, we achieve precise control over defect density, as confirmed by spectroscopic and crystallographic analyses. The resulting defect-rich cocrystals demonstrate high sensitivity and selectivity toward dimethoate, an organophosphorus pesticide, via shape-complementary dual hydrogen bonding at defect sites. This breakthrough in controlled defect engineering in molecular crystals opens new avenues for the development of functional organic materials for applications in sensing, catalysis, and beyond.

Results and discussion

Molecular design

Hydrogen bonding is a ubiquitous linkage mechanism in biological systems, yet it often encounters issues with linkage defects. Inspired by this, we sought to deliberately introduce linkage defects in molecular crystals by engineering intermolecular hydrogen bonding imperfections. To achieve this, we required a host crystal formed through continuous hydrogen bonding, into which a defective molecule could be incorporated—one that connects similarly but introduces a flaw in the bonding network. Molecule 1 was herein selected as the host due to its benzimidazole end groups, which enable the formation of shape-controlled 2D platelets through continuous hydrogen bonding with alcohols39. Molecule 2 was designed as the defective molecule, featuring 2-(2’-hydroxyphenyl)benzimidazole groups at both ends. These groups were expected to form intramolecular hydrogen bonds between the hydroxyl group and the hydrogen bond acceptor on the benzimidazole moiety, leaving a hydrogen bond donor on the benzimidazole group available for binding with molecule 1. This intramolecular hydrogen bonding in molecule 2 would disrupt continuous hydrogen bonding network of the host crystal of molecule 1, as illustrated in Fig. 1.

Construction of 2D cocrystals with regulated defects

To explore the feasibility of coassembling molecules 1 and 2, we initially employed a conventional self-assembly approach. Equal volumes of solutions of 1 (0.05 mL, 0.5 mg/mL) and 2 (0.05 mL, 0.5 mg/mL) were prepared in a 1:3 (v/v) mixture of chloromethane and 1-propanol, thoroughly mixed, and subsequently injected into 1 mL of hexane and aged for 72 h. Fluorescence microscopy revealed the simultaneous formation of 2D platelets and 1D microrods, with time-dependent imaging showing that 1D microrods formed prior to 2D platelets (Supplementary Fig. 15). Adjusting the molar ratios of 1 to 2 failed to yield exclusive 2D or 1D morphologies (Supplementary Fig. 16). Control experiments confirmed that 2 alone formed green-emitting 1D microrods (Supplementary Fig. 17), while 1 exclusively produced 2D platelets under identical conditions. These results indicate that 1 and 2 adopt distinct molecular packing modes, preventing their coassembly. Single-crystal X-ray diffraction (SCXRD) analysis of the microrods of 2 reveals that the hydroxyl group in its phenyl linker serves as both a hydrogen-bond donor and acceptor, facilitating benzimidazole connectivity along the a-axis (Supplementary Fig. 18). This hydrogen-bonding motif drives zig-zag packing of 2 along the c-axis, contrasting sharply with the packing arrangement of 1 and its alcohol conformer within 2D platelets39,40.

To overcome the distinct molecular packing behaviors of 1 and 2 and enable the formation of cocrystals, we employed supersaturated solution-fed seeded self-assembly to achieve the coordinated growth of 1 and 2. Initially, the 2D platelets of 1 were prepared and sonicated at −20 °C for 8 h to generate irregular fragments, which served as seeds for subsequent seeded self-assembly (Supplementary Fig. 19). Remarkably, when 0.01 mL of a seed solution (0.05 mg/mL) in a hexane/1-propanol mixture (10:1 v/v) was introduced to 1 mL of a supersaturated solution of 1 and 2 (0.5 mg/mL) in the same solvent mixture and aged for 1 h, uniform yellow-emitting, square-shaped 2D cocrystals were formed, as observed by fluorescence microscopy (Fig. 2a). The narrow area dispersity (Aw/An ≤1.02) of the 2D cocrystals indicates high uniformity, characteristic of a living seeded self-assembly process. Furthermore, the size of the square-shaped 2D cocrystals could be precisely controlled by varying the monomer-to-seed mass ratio (mmonomer/mseed) (Fig. 2b and Supplementary Fig. 20), further demonstrating the living nature of the assembly. Notably, no 1D microrods of 2 were observed even after extended aging for over 48 h. The absorption and fluorescence spectra of the resulting 2D cocrystals were identical to those of 2D platelets formed from 1 alone (Supplementary Fig. 21), suggesting that the seeds guided 1 and 2 to pack in a manner consistent with the structure of 2D platelets formed from 1 alone. Powder X-ray diffraction (PXRD) analysis confirmed that the coassembled 2D cocrystals exhibited patterns similar to those of 2D platelets formed from 1 alone, but distinct from the 1D microrods assembled from 2 alone (Fig. 2c and Supplementary Fig. 22). Selected-area electron diffraction (SAED) patterns (Fig. 2d-g) revealed identical diffraction patterns across different locations on the 2D cocrystals, indicating uniform molecular packing throughout the structure.

a Fluorescence-mode optical image and statistical histogram of 2D cocrystals of 1 and 2 at a 1:1 molar ratio. b Area distribution of 2D cocrystals as a function of the monomer-to-seed mass ratios. c XRD patterns of 2D platelets of 1, 2D cocrystals of 1 and 2 at a 1:1 molar ratio, and 1D microrods of 2. d TEM image of a 2D cocrystal of 1 and 2 at a 1:1 molar ratio. e−g SAED patterns obtained at various locations on the 2D cocrystal shown in (d). h Single-crystal structure of the 2D cocrystal of 1 and 2 at a 1:1 molar ratio, revealing the presence of linkage defects.

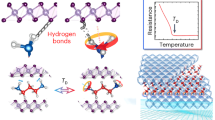

To further investigate the molecular packing of 1 and 2 and confirm the presence of linkage defects in the coassembled 2D cocrystals, single-crystal X-ray diffraction (SCXRD) analysis was performed on the crystals of 1 and 2 at a 1:1 molar ratio. Figure 2h and Supplementary Fig. 22 show that both 1 and 2 in the 2D cocrystals adopt the same molecular orientation as 1 in the seeds. However, unlike 1, intramolecular hydrogen bond (O···H–N: 2.10 Å, N···H–O: 1.92 Å) occurs between the hydroxyphenyl group and imidazole. This blocks the hydrogen bond sites on 2, leaving only the benzimidazole group of 1 with accessible acceptor (N) and donor (N–H) sites at opposing termini. As a result, the intramolecular hydrogen bonds lead to the formation of linkage defects within the 2D cocrystals (Fig. 2h).

Having established the coassembly of 1 and 2 and the generation of defects via seeded self-assembly, we next investigated the tunable range of defect densities in the resulting 2D cocrystals. A hexane/1-propanol mixture (10:1 v/v, 1 mL) containing 1 and 2 at varying molar ratios (ranging from 5:1 to 1:5) but a constant total concentration of 0.5 mg/mL was added to a seed solution (0.05 mg/mL, 0.01 mL) in the same solvent system. After aging for 24 h, uniform 2D cocrystals were obtained (Fig. 3a–d). AFM images show that the 2D platelets have a uniform thickness of 290–310 nm (Supplementary Fig. 23). The introduction of each molecule 2 can produce two defect sites, according to which the density of defects can be calculated (Fig. 3e, Supplementary Figs. 24–26, and Table S2). The defect density increased with the molar proportion of 2, reaching saturation at a 1:2 molar ratio of 1 to 2. Beyond this threshold, further increases in the proportion of 2 did not elevate the defect density, indicating that the 2D cocrystals had reached their maximum defect accommodation capacity of 54 site/nm3. Notably, increasing the molar proportion of 2 also induced a morphological transition in the cocrystals, from hexagonal to square (Fig. 3a–d), despite maintaining consistent molecular packing as confirmed by PXRD and SAED analysis (Supplementary Figs. 27 and 28). This shape evolution is attributed to kinetic growth modulation in two dimensions during coassembly. Defects, which disrupt hydrogen bonding, likely slow crystal growth asymmetrically, leading to changes in morphology.

Fluorescence-mode optical images and corresponding statistical histograms of 2D cocrystals of molecules 1 and 2 at varying molar ratios of 1 to 2: a 5:1, b 2:1, c 1:2, and d 1:5. e Correlation between the molar ratio of 1 to 2 and the defect density. f Fluorescence-mode optical image and a schematic diagram depicting the seeded growth of a concentric multiblock 2D hetero-cocrystal.

To further demonstrate defect control, we sequentially added supersaturated solutions of 1 and 2 (0.5 mg/mL) at varying molar ratios (5:1, 2:1, and 1:1) in a hexane/1-propanol mixture (10:1 v/v, 1 mL) to a seed solution (0.025 mg/mL, 0.01 mL) in the same solvent system. After each cycle of seeded self-assembly, the bulk solvent was removed, and a new feed solution was introduced to initiate the next growth cycle. Figure 3f shows the formation of 2D cocrystals with distinct emission regions, where weakly emitting regions correspond to higher defect densities. These results demonstrate that defect densities in 2D cocrystals can be precisely tuned, directly influencing their optical properties. Notably, fluorescence microscopy and AFM images at various growth stages reveal an increase in platelet area from 55 to 137 μm2, while the height increases from 310 nm to 330 nm (Supplementary Fig. 29). SEM imaging of 2D hetero-cocrystal does not resolve any distinct phase boundaries between these regions. Microspectroscopy reveals that different regions within the concentric multiblock 2D hetero-cocrystal exhibit identical emission peak positions, suggesting the same molecular packing across cocrystals regardless of varying defects (Supplementary Fig. 30). Combining with single-crystal XRD analysis, we have presented a molecule packing diagram illustrating molecular arrangement throughout the interfaces (Supplementary Fig. 31).

Effects of defects on optical properties

We observed that the defect density significantly influenced the emission properties of the 2D cocrystals (Fig. 3e). This prompted a detailed investigation into the effects of defects on their optical properties. The absorption and fluorescence spectra of the 2D cocrystals of 1 and 2 at varying molar ratios closely resembled those of the 2D platelets of 1 alone (Fig. 4a). This similarity suggests that the molecular packing in these assembles is identical, consistent with the XRD results (Fig. 2c and Supplementary Fig. 27). However, despite these similarities, the fluorescence quantum yields (FQYs) of the 2D cocrystals decreased markedly with increasing defect density (Fig. 4b). At the maximum defect density (54 site/nm3), the FQY dropped to approximately 20%, significantly lower than that of the defect-free 2D platelets of 1 (~60%) and the 1D microrods of 2 (~41%). This reduction in FQY is attributed to the presence of free N-H groups at defect sites, which enhances non-radiative transitions. A corresponding trend was observed in the fluorescence lifetimes of the 2D cocrystals (Fig. 4c). As defect density increased, the fluorescence lifetime decreased significantly, revealing an inverse relationship between the two parameters. Specifically, the 2D cocrystals with the highest defect density (54 site/nm3) exhibited a fluorescence lifetime of only 4.4 ns (Fig. 4c, d), substantially shorter than the 10 ns lifetime of the defect-free 2D platelets of 1.

a UV-vis absorption and fluorescence spectra under emission at 380 nm of 2D platelets assembled with varying molar ratios of 1 to 2. b Correlation between defect density and the FQY of the 2D platelets. c Correlation between defect density and the fluorescence decay curves of the 2D platelets. d Correlation between defect density and the fluorescence lifetime of the 2D platelets.

Detection of trace dimethoate

The presence of defects with specific pore sizes and unbound N-H sites in the 2D cocrystals suggests their potential to selectively bind functional groups, such as amido groups. This binding can constrain the N-H vibrations at the defect sites, leading to an enhancement in the fluorescent intensity of the 2D cocrystals. This property makes the 2D cocrystals promising candidates for sensing applications, particularly for the detection of target analytes like dimethoate. To validate this, we employed 2D cocrystals with a defect density of 43 site/nm3 as sensing materials and integrated them into a customized device equipped with a silicon diode detector for dimethoate detection (Supplementary Fig. 32). Figure 5a shows the enhanced fluorescence responses of the 2D cocrystals upon exposure to varying concentrations of dimethoate vapor. Remarkably, the 2D cocrystals exhibit significant fluorescence enhancement even at dimethoate concentrations as low as 0.1 ppb (Fig. 5a). In contrast, 2D platelets of molecule 1 show fluorescence responses only at concentrations above 100 ppb (Fig. 5b), while 1D microrods of molecule 2 display no response within the tested concentration range (10–100 ppb). These findings underscore the critical role of defects in achieving high sensitivity to dimethoate. Notably, as shown in Fig. 5c and Supplementary Fig. 33, the limit of detection (LOD) decreases with increasing defect density, further emphasizing the importance of defect engineering for enhanced sensing performance.

a Fluorescence responses of 2D cocrystals (defect density: 43 sites/nm3) to varying concentrations of dimethoate vapor. b Fluorescence responses of 2D platelets of 1 and 1D microribbons of 2 to varying concentrations of dimethoate vapor. c Limit of detection (LOD) for dimethoate sensing using 2D platelets with varied defect densities. d Fluorescence responses of 2D cocrystals (43 sites/nm3) to potential interferents, including water, common organic solvents, and other pesticides. e, f DFT-calculated interaction mechanisms of dimethoate with the 2D cocrystal (e) and the 2D platelet of 1 (f).

In addition to their high sensitivity, the 2D cocrystals demonstrated high selectivity for dimethoate over potential interferents such as water, common organic solvents, and other pesticides. As shown in Fig. 5d and Supplementary Figs. 34 and 35, exposure of the 2D cocrystals to high concentrations of these interferents resulted in minimal reversible fluorescence responses. These observations highlight the ability of defects with specific pore sizes and unbound N-H sites to selectively bind functional groups like amido groups, thereby triggering enhanced emission. Besides, XRD measurements show unaltered diffraction patterns before and after adsorption of dimethoate molecules, indicating the cocrystal structure remains intact (Supplementary Fig. 36). The duration of completely releasing dimethoate absorbed in cocrystals is around ~192 s as shown in the following Supplementary Fig. 37. The absorption/releasing cycles indicate the recycling and potential use in practical applications. To gain deeper insights into the interactions between the amido group and the defect sites, density functional theory (DFT) calculations were performed. Figure 5e illustrates how dimethoate molecules anchor to the 2D cocrystal surface through dual hydrogen bonds (O···H−N: 2.01 Å and N···H−O: 2.00 Å) at the defect sites. Charge density difference mappings reveal that these interactions are primarily driven by specific dual hydrogen bonding, which is significantly stronger than electrostatic interactions in the absence of defects. The calculated binding energy for this interaction reaches up to 32.9 kcal/mol. In contrast, 2D platelets of 1 bind dimethoate through weaker electrostatic interactions on the crystal surface, yielding a binding energy of only 6.4 kcal/mol (Fig. 5e). These results demonstrate that defects facilitate stronger interactions with dimethoate through optimized hydrogen bonding, thereby enhancing both sensitivity and selectivity.

In conclusion, we have achieved controllable defects in 2D molecular crystals using a supersaturated solution-fed seeded self-assembly of molecules 1 and 2. Molecule 2, which bears 2-(2’-hydroxyphenyl)benzimidazole end groups, acts as the defect molecule, allowing for the formation of intramolecular hydrogen bonds on one side of benzimidazole groups while leaving a hydrogen bond donor on the other side available for intermolecular hydrogen bonding. When coassembled with molecule 1, which has two-sided hydrogen bonding sites on each end group to connect alcohol, defects in hydrogen-bonding linkage can be created. Controlling the numbers of defects can be achieved by simply adjusting the ratio of 1 to 2, which in turn regulates the optical properties of the formed 2D cocrystals. Shape-matching hydrogen bonding between defects and dimethoate in the 2D cocrystals makes them ideal fluorescence sensors with high sensitivity and selectivity. Defect engineering in molecular crystals is opening up new potential in a wide range of organic materials systems. This approach offers a promising strategy for engineering molecular materials with tunable properties for advanced sensing applications.

Methods

Molecular synthesis

The synthetic routes of molecules 1 and 2 are shown in the Supplementary Figs. 1 and 8 and the detailed characterization of molecules 1 and 2 are shown in the Supplementary Figs. 5–7 and 11–13.

Self-assembly of the 1D microrods of molecule 2

1D microrods of 2 were synthesized by adding 0.1 mL of a 0.5 mg/mL solution of 2 in 1-propanol/chloroform (3:1 v/v) to 1 mL hexane, followed by aging at 25 °C for 24 h.

Fabrication of 2D cocrystals via seeded self-assembly

The fabrication of 2D cocrystals with controlled shapes was performed via supersaturated solution-fed seeded self-assembly35. Firstly, the 2D platelets of 1 were prepared by injecting 0.1 mL of a solution of 1 in 1-propanol/chloroform (3:1 v/v, 0.5 mg/mL) into 1 mL of hexane in a 4 mL vial and aging at 25 °C for 24 h. The seeds (0.05 mg/mL) were then prepared by sonicating the 2D platelets of 1 at −20 °C for 8 h. The 2D cocrystals with controlled shapes were synthesized by adding 1 mL of supersaturated solutions—prepared by mixing 1 and 2 (each at 0.05 mg/mL in hexane/1-propanol, 10:1 v/v) at different volume ratios (ranging from 5:1 to 1:5)—to a seed solution (0.05 mg/mL, 0.01 mL in the same solvent), followed by aging at 25 °C for 72 h.

Fabrication of multiblock 2D cocrystals

The multiblock 2D cocrystals were synthesized by sequentially adding 500 μL of supersaturated solutions—prepared by mixing 1 and 2 (each at 0.05 mg/mL in hexane/1-propanol, 10:1 v/v) at different volume ratios (5:1, 2:1, and 1:1)—to a seed solution (0.05 mg/mL, 0.01 mL in the same solvent), followed by aging at 25 °C for 24 h. After each cycle of supersaturated solution-fed seeded self-assembly, the majority of the solvent was carefully removed before the next cycle.

Bulk cocrystals for single-crystal X-ray diffraction (SCXRD) analysis

Different bulk cocrystals with a size of at least 50 μm in each dimension were grown by adding 5 mL of supersaturated solutions—prepared by mixing 1 and 2 (each at 0.05 mg/mL in hexane/1-propanol, 10:1 v/v) at different volume ratios (ranging from 5:1 to 1:5)—to a seed solution (0.05 mg/mL, 0.001 mL in the same solvent), followed by aging at 25 °C for 72 h.

The molecule structures were solved by direct methods using SHELXS-2014, and the non-hydrogen atoms were refined on F2 by full-matrix least-squares procedures with SHELXL-2019/3. All non-hydrogen atoms were refined anisotropically. During the refinement, the hydrogen atoms attached to C atoms were generated geometrically with the riding model and the hydrogen atoms attached to N atoms and O atoms were determined according to the orientation of corresponding hydrogen bonds with N–H = 0.88 Å and O–H = 0.84 Å (Supplementary Fig. 14 and Table S1).

Calculation of defect density

The ratio of 1 to 2 in the 2D cocrystal can be obtained by calculating the percentage of oxygen atoms in the single crystal. The introduction of each molecule 2 can produce two defect sites. The defect density can be calculated by the following equation:

where x2 represents the proportion of 2 in 2D cocrystal and V represents the volume of a crystal cell.

Property and sensing characterizations

Fluorescence-mode optical microscopic images were acquired using an Olympus IX71 fluorescence microscope with a standard CCD detector, in which the samples were excited by a 365 nm ultraviolet LED lamp. Absorption and emission spectra were measured with a CRAIC Technologies UV-visible-NIR microspectrometer. Transmission electron microscopy (TEM) images were obtained using Hitachi JEM-2100 transmission electron microscopy. Selected-area electron diffraction (SAED) analysis was performed using a Talos F200X TEM. SCXRD analysis was performed on a Rigaku XtaLAB PRO 007HF diffractometer with graphite-monochromated Cu Kα radiation (λ = 1.54184 Å) in ω-scan mode. Powder X-ray diffraction (PXRD) patterns were obtained using a Bruker Rigaku SmartLab diffractometer. 1H NMR spectra were acquired on a Bruker AVANCE 400 MHz spectrometer. Fluorescence quantum yields and fluorescence lifetimes were determined using an Edinburgh Instruments steady-state/transient fluorescence spectrometer coupled with an integrating sphere with a 365 nm pulsed laser serving as the excitation source.

A custom detection system, consisting of a silicon diode detector and an Ocean Optics USB4000 fluorometer (spectral acquisition mode) with a 380 nm LED light (0.05 mW/cm2 intensity) serving as the excitation source. A 10 μL suspension of 2D cocrystals (0.05 mg/mL) in hexane was injected into a quartz tube and dried under a nitrogen stream. The tube with 2D cocrystals inside was then exposed to organophosphorus pesticide vapors at varying concentrations to assess its fluorescence response. The pesticide vapor was introduced into the system via a peristaltic pump at a flow rate of 150 mL/min. Real-time fluorescence signals were recorded to quantify the detection sensitivity for organophosphorus pesticides.

The areas of the 2D platelets were measured by tracing the edge of each platelet and measured by ImageJ software. Analysis of the number average area (An) and weight average area (Aw) was calculated by the following equations:

Area analysis in each statistic data set was performed on the measurements of at least 100 platelets.

Theoretical calculations

The first-principles calculations based on density functional theory (DFT) were performed to investigate the binding energetics and electronic interactions between dimethoate and two distinct crystals: (i) 2D platelets of 1, and (ii) 2D cocrystals formed from 1 and 2 at 1:1 molar ratio. All DFT calculations were conducted within the CASTEP module of Materials Studio 2019. The exchange-correlation interactions were modeled using the Perdew–Burke–Ernzerhof (PBE) functional under the generalized gradient approximation (GGA). A Monkhorst-Pack k-point grid of 2 × 2 × 2 was utilized for Brillouin zone integration, and the energy convergence threshold was rigorously set to 10–5 eV per atom to ensure computational accuracy.

Data availability

The raw data for each curve in the plots generated in this study are shown in the Source data file. Crystallographic data for the structures reported in this Article have been deposited at the Cambridge Crystallographic Data Centre, under deposition numbers CCDC 2171137 (Molecule 1), 2425289 (Molecule 2), 2425395 [Molecule 1:2 (5:1)], 2425393 [Molecule 1:2 (2:1)], 2425391 [Molecule 1:2 (1:1)], and 2425392 [Molecule 1:2 (1:2 and 1:5)]. Copies of the data can be obtained free of charge via https://www.ccdc.cam.ac.uk/structures/. All data are available from the corresponding author upon request. Source data are provided with this paper.

References

De Souza, R. & Harrington, G. Revisiting point defects in ionic solids and semiconductors. Nat. Mater. 22, 794–797 (2023).

McGuigan, S. & Fosu, E. A. Defects orchestrate concerted CO2 catalysis. Nat. Rev. Chem. 8, 492–492 (2024).

Ahmad, B. I. Z. et al. Defect-engineered metal–organic frameworks as bioinspired heterogeneous catalysts for amide bond formation. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 146, 34743–34752 (2024).

Chen, S. et al. Defective TiOx overlayers catalyze propane dehydrogenation promoted by base metals. Science 385, 295–300 (2024).

Lee, C. W. et al. Photochemical tuning of dynamic defects for high-performance atomically dispersed catalysts. Nat. Mater. 23, 552–559 (2024).

Ronceray, N. et al. Liquid-activated quantum emission from pristine hexagonal boron nitride for nanofluidic sensing. Nat. Mater. 22, 1236–1242 (2023).

Deng, T. et al. Room-temperature exceptional plasticity in defective Bi2Te3-based bulk thermoelectric crystals. Science 386, 1112–1117 (2024).

Sebti, E. et al. Stacking faults assist lithium-ion conduction in a halide-based superionic conductor. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 144, 5795–5811 (2022).

Day, A. M., Dietz, J. R., Sutula, M., Yeh, M. & Hu, E. L. Laser writing of spin defects in nanophotonic cavities. Nat. Mater. 22, 696–702 (2023).

Ye, G., Liu, S., Zhao, K. & He, Z. Singlet oxygen induced site-specific etching boosts nitrogen-carbon sites for high-efficiency oxygen reduction. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 62, e202303409 (2023).

A. Mohamed, W. et al. Engineering porosity and functionality in a robust twofold interpenetrated bismuth-based MOF: toward a porous, stable, and photoactive material. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 146, 13113–13125 (2024).

Yin, Q. et al. Unveiling the effect of cooling rate on grown-in defects concentration in polycrystalline perovskite films for solar cells with improved stability. Adv. Mater. 36, 2405840 (2024).

Chen, Z. et al. Solvent-free autocatalytic supramolecular polymerization. Nat. Mater. 21, 253–261 (2022).

Sleczkowski, M. L., Mabesoone, M. F. J., Sleczkowski, P., Palmans, A. R. A. & Meijer, E. W. Competition between chiral solvents and chiral monomers in the helical bias of supramolecular polymers. Nat. Chem. 13, 200–207 (2021).

Fukaya, N. et al. Impact of hydrophobic/hydrophilic balance on aggregation pathways, morphologies, and excited-state dynamics of amphiphilic diketopyrrolopyrrole dyes in aqueous media. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 144, 22479–22492 (2022).

Fukui, T. et al. Control over differentiation of a metastable supramolecular assembly in one and two dimensions. Nat. Chem. 9, 493–499 (2017).

Greciano, E. E., Matarranz, B. & Sanchez, L. Pathway complexity versus hierarchical self-assembly in n-annulated perylenes: structural effects in seeded supramolecular polymerization. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 57, 4697–4701 (2018).

Rao, K. V. et al. Distinct pathways in “thermally bisignate supramolecular polymerization”: spectroscopic and computational studies. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 142, 598–605 (2020).

He, Y. et al. Uniform biodegradable fiber-like micelles and block comicelles via “living” crystallization-driven self-assembly of poly(l-lactide) block copolymers: the importance of reducing unimer self-nucleation via hydrogen bond disruption. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 141, 19088–19098 (2019).

Kang, J. et al. A rational strategy for the realization of chain-growth supramolecular polymerization. Science 347, 646–651 (2015).

Khanra, P., Singh, A. K., Roy, L. & Das, A. Pathway complexity in supramolecular copolymerization and blocky star copolymers by a hetero-seeding effect. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 145, 5270–5284 (2023).

Sun, L. et al. Light-regulated nucleation for growing highly uniform single-crystalline microrods. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 63, e202402253 (2024).

Ma, X. et al. Fabrication of chiral-selective nanotubular heterojunctions through living supramolecular polymerization. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 55, 9539–9543 (2016).

Gong, Y. et al. Fabrication of two-dimensional platelets with heat-resistant luminescence and large two-photon absorption cross sections via cooperative solution/solid self-assembly. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 145, 9771–9776 (2023).

Ogi, S., Matsumoto, K. & Yamaguchi, S. Seeded polymerization through the interplay of folding and aggregation of an amino-acid-based diamide. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 57, 2339–2343 (2018).

Ogi, S., Sugiyasu, K., Manna, S., Samitsu, S. & Takeuchi, M. Living supramolecular polymerization realized through a biomimetic approach. Nat. Chem. 6, 188–195 (2014).

Choi, H., Ogi, S., Ando, N. & Yamaguchi, S. Dual trapping of a metastable planarized triarylborane π-system based on folding and Lewis acid-base complexation for seeded polymerization. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 143, 2953–2961 (2021).

Sasaki, N. et al. Multistep, site-selective noncovalent synthesis of two-dimensional block supramolecular polymers. Nat. Chem. 15, 922–929 (2023).

Sarkar, A. et al. Tricomponent supramolecular multiblock copolymers with tunable composition via sequential seeded growth. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 60, 18209–18216 (2021).

Sarkar, A. et al. Cooperative supramolecular block copolymerization for the synthesis of functional axial organic heterostructures. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 142, 11528–11539 (2020).

Moreno-Alcantar, G. et al. Solvent-driven supramolecular wrapping of self-assembled structures. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 60, 5407–5413 (2021).

Jin, X. H. et al. Long-range exciton transport in conjugated polymer nanofibers prepared by seeded growth. Science 360, 897–900 (2018).

He, X. et al. Two-dimensional assemblies from crystallizable homopolymers with charged termini. Nat. Mater. 16, 481–488 (2017).

Liao, C. et al. Concentric hollow multi-hexagonal platelets from a small molecule. Nat. Commun. 15, 5668 (2024).

Liao, C. et al. Living self-assembly of metastable and stable two-dimensional platelets from a single small molecule. Chem. Eur. J. 29, e202301747 (2023).

Qiu, H. et al. Uniform patchy and hollow rectangular platelet micelles from crystallizable polymer blends. Science 352, 697–701 (2016).

Liu, B. et al. Spontaneous emergence of self-replicating molecules containing nucleobases and amino acids. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 142, 4184–4192 (2020).

Tong, Z. et al. Uniform segmented platelet micelles with compositionally distinct and selectively degradable cores. Nat. Chem. 15, 824–831 (2023).

Gong, Y. et al. Unprecedented small molecule-based uniform two-dimensional platelets with tailorable shapes and sizes. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 144, 15403–15410 (2022).

Fu, L. et al. Control over the geometric shapes and mechanical properties of uniform platelets via tunable two-dimensional living self-assembly. Chem. Mater. 35, 1310–1317 (2023).

Acknowledgements

Financial support was from the Taishan Scholars Program [No. tsqn202306257 (Y.G.)], the Natural Science Foundation of Shandong Province [Nos. ZR2024YQ012 (Y.G.) and ZR2024MB118 (L.Y.)], the National Key Research and Development Program of China [No. 22494681 (Y.C.)], and the National Natural Science Foundation of China [No. 21972074 (L.Y.)].

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Y.G., Y.C., L.Y., and W.T. conceived the project. W.T. and Y.G. synthesized the materials. W.T. performed the experiments with assistance from other authors. W.T., L.S., S.L., Q.H., L.Y., Y.C., Y.G., and J.Z. contributed to data discussions. W.T., Y.G., Y.C., and L.Y. analyzed the data. W.T., Y.G., Y.C., and L.Y. wrote the manuscript with input from the other authors.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Peer review

Peer review information

Nature Communications thanks Antonio Fernandez, Yue-Biao Zhang, and the other anonymous reviewer(s) for their contribution to the peer review of this work. A peer review file is available.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Source data

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Tai, W., Sun, L., Liu, S. et al. Crafting defects in two-dimensional organic platelets via seeded coassembly enables emergent molecular recognition. Nat Commun 16, 7968 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-025-63336-y

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-025-63336-y