Abstract

Cascade multiplication is widely used to enhance photon detector sensitivity. While vacuum tube and semiconductor photomultipliers achieve high gains in the optical range, their performance at lower frequencies is limited by large work functions. Superconducting detectors overcome this constraint, enabling operation in the terahertz (THz) and microwave (MW) ranges. Here we introduce a concept of cascade-amplified superconducting detectors based on Josephson junction arrays. Interjunction coupling in an array triggers avalanche-like switching of multiple junctions upon photon absorption, resulting in cascade amplification of the readout voltage and an increased signal-to-noise ratio. We present prototypes using either low-Tc linear Nb/NbxSi1−x/Nb arrays or Bi2Sr2CaCu2O8+δ high-Tc stacked intrinsic Josephson junctions. Both MW and THz responses are analyzed and the advantages of the cascade detector over a conventional single-junction detector are demonstrated. Our findings suggest that Josephson junction arrays hold promise for the development of highly sensitive, broadband MW-to-THz detectors.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Detectors in MW and THz ranges find diverse applications, including security, environmental monitoring, medical imaging, chemical analysis, future telecommunication, and fundamental research1,2,3. Single-photon and photon-counting detectors are essential for quantum optics and electronics3,4,5,6. However, despite two decades of intense research1,2,3,4,5,6,7,8,9,10,11,12,13,14,15,16,17,18,19,20,21,22,23, MW and THz single-photon detectors are still not commercially available due to various technical challenges and materials limitations.

The primary challenge arises from the small photon energy, placing constraints on materials. Conventional vacuum tube and semiconductor photodetectors3 are not suitable for this range. Low- gap materials such as superconductors4,5,6,7,8,9,10,11,12,13,14,15,16, half-metals12,17,18,19, and gap-engineered quantum dots20,21 are required. In addition, in situ gap tuning is necessary to optimize detector performance and adjust the dynamic range15. This can be achieved through electrostatic gating5,11,12,17,18,19,20,21, magnetic field4,6,15,20, bias6,9,10,15,22,23, temperature7,8,9,10,15,16,22,23, etc.

Another problem is associated with the large wavelength λ0 ~mm, which makes it difficult catching photons by micron-size detectors. A sensitive detector must have high optical absorption efficiency χ, but size mismatch leads to a large impedance mismatch with free space, reducing χ24. Dedicated pickup antennas with sizes ~λ0 must be implemented to achieve impedance matching and optimal χ ≃ 0.524,25.

The low photon energy imposes stringent requirements on detector characteristics. For single-photon resolution, the Noise-Equivalent Power (NEP) should be in the zW/Hz1/2 range11,12,16,20,21. To avoid intense background radiation, such devices should be cooled to low temperatures, enabling utilization of superconductors. Superconductivity is beneficial for ultrasensitive detectors due to the absence of Jonson-Nyquist noise in the electrodes. Several existing superconducting detectors, particularly those based on qubits4,5,6,11,12, approach the quantum limit of sensitivity. The base element exhibiting quantum-mechanical behavior26, is the Josephson junction (JJ).

A current-biased JJ can function as a sensitive switching current detector (SCD) in a broad MW-to-THz range15,22,23,27,28,29,30,31,32,33,34. The responsivity of SCD can be very high, ultimately limited by quantum fluctuations15,34 or phase diffusion15,35. The upper frequency depends on the characteristic voltage, Vc, and ranges from sub-THz for low-Tc, to THz-range for high-Tc JJs29,31,32,36. The highest Vc ≳30 mV37,38 is achieved in intrinsic Josephson junctions (IJJ) naturally formed in Bi-2212 cuprates39. The operation of IJJs above 10 THz has been reported29,36. The atomic scale of IJJs leads to a strong mutual coupling and enables coherent behavior29,32,40,41,42,43,44,45. The coupling leads to a current-locking phenomenon, when switching of one JJ drags several neighbors to the resistive state, thereby cascade-multiplying the readout voltage46,47,48.

Here we demonstrate prototypes of cascade SCD based on a linear Nb-array and a stack of IJJs in a whisker-type Bi-2212 single crystal. We investigated MW and THz responses and compared single-junction and cascade SCD operation on the same device. The absorption efficiency is analyzed by studying the MW polarization loss diagrams. We discuss the operation principle and the ultimate performance of cascade SCD. The advantage is shown to be associated with a new, pure cascade gain operating mode, allowing both cascade amplification of the sensitivity and reduction of statistical noise.

Results

Cascade multiplication is widely used in photon detectors, such as photomultipliers and avalanche photodiodes3. Cascading increases the sensitivity S (V/W) in proportion to the number of stages, Sn = nS1. As sketched in Fig. 1a, this will reduce NEP = δV/S, provided the noise floor, δV (V/Hz1/2), is not multiplied equally.

a A concept of cascade amplified detector. b The energy-phase diagram of a Josephson junction array. Switching (escape) of one junction leads to avalanche-like switching of neighbors due to the interjunction coupling. c The current-voltage characteristics of a linear array with N = 1000 Nb/NbxSi1−x/Nb junctions at T ≃ 2.5 K. A nearly perfect current locking of all junctions can be seen. The inset shows the array layout. d–f Operation of a single-junction detector, SCD1. Calculated switching probabilities d and probability densities e without (navy) and with (magenta) radiation. (f) Calculated voltage response (red) and sensitivity (olive line) for ib = Ib/Ic0 = 0.972. Based on the data from ref. 15. g,h Operation of a cascade detector, SCDn. g Three examples of active junction number distribution, n(PTHz), for arrays with N = 200 junctions: uniform (δPn = δP1/4, n0 = 50, blue), intermediate (δPn = δP1, n0 = 25, red), nonuniform case (δPn = 2δP1, n0 = 10, olive), where δP1 is the response range of a single junction, the red line in (f). h Array responses, calculated from Eq. (5). i Cascade gains for the three cases from (g). Note that they can be larger than n.

We aim to achieve cascade multiplication in JJ arrays. Individual JJs in an array have inevitable variations. Without interjunction coupling, the low-power response is determined by the weakest single JJ. With coupling, a current-locking phenomenon occurs46, causing several JJs to switch simultaneously, as sketched in Fig. 1b. Figure 1c shows the current-voltage (I-V) characteristics of a linear array of N = 1000 Nb/NbxSi1−x/Nb JJs49. It exhibits a nearly perfect current locking of all JJs, leading to a high readout voltage, V ≃ 0.45 V.

JJ arrays have been known to be advantageous for photon detection: arrays can help with impedance matching and broaden the dynamic range50,51. However, earlier studies focused on heterodyne mixers, operating in the quasiparticle branch of the I–V. In contrast, here we consider SCD, where the signal is generated upon switching out of the superconducting state.

Operation principle

The JJ dynamics is equivalent to motion of a particle in a tilted washboard potential26,34, Fig. 1b. The potential well is determined by the Josephson energy EJ0 = (Φ0/2π)Ic0, where Φ0 is the flux quantum and Ic0 is the fluctuation-free critical current. The SCD is biased by an ac-current with frequency fb and amplitude Ib ≲ Ic0. Transition to the resistive state occurs at a switching current Is < Ic0. The premature escape from the well is caused by internal thermal or quantum fluctuations15,26,34, and by the high-frequency current ITHz, induced by the incoming THz power15,

Here RTHz is the real part of the THz impedance.

Figure 1d–f summarize operation of an SCD1, based on simulations from ref. 15 for an underdamped JJ with the quality factor Q0 = 100, Ic0 = 50 μA, fb = 150 Hz, Vc = 20 mV (Bi-2212), T = 1 K, nonresonant escape, optimal χ = 0.5 and RTHz = 100 Ω52. For more details, see ref. 15 and Supplementary sections SI–III.

Figure 1d, e show switching probabilities, G(I), and probability densities, g = dG/dI (switching current histograms) without and with radiation. The response of SCD1 is caused by the suppression of Is, which shifts histograms and increases switching probability ΔG(I = Ib), leading to the mean voltage rise,

The red line in Fig. 1f shows the response at Ib = 0.972 Ic0. It saturates when ΔIs exceeds the full-width at half-maximum (FWHM) of the switching histogram,

The sensitivity, S1 = ΔV1/PTHz, shown by the olive line in Fig. 1f, is limited only by the finite δIs1.

A switching current is reached twice per bias period at positive and negative current maxima. The probabilistic (binomial) switching leads to a telegraph noise15,

which determines the noise floor and limits NEP1 to ~1 pW/Hz1/2 for the case of Fig. 1d–f. Note that NEP1 does not depend on Vc because it appears in both Eqs. (2) and (4). Vc only affects the frequency range.

For a multi-junction cascade detector (SCDn), the array response and sensitivity can be written as,

where \({G}_{n}^{*}\) is the probability of collective switching of n JJs. The first term in Eq. (6) is caused by the shift of histograms, ΔIs(P), similar to SCD1. The second term represents a new detection mechanism specific for SCDn, where the response ∝ ∂n/∂P, is caused by the pure cascade gain without shifting of Is.

The switching statistics of an imperfect array are not binomial, but follow a compound distribution, where the output acquires a mean value, n, and a standard deviation δn. This changes the statistical noise,

In the ideal current locking case, n = N, δn = 0, Eq. (7) reduces to Eq. (4), but with a multiplied telegraph noise. This will not improve NEP. On the other hand, the uncertainty from the second term in Eq. (7) does not depend on n. Therefore, operation in the pure cascade gain mode, \({G}_{n}^{*}=1\), allows the obviation of large telegraph noise, which improves NEPn.

Figure 1g–i summarizes SCDn operation. The performance of SCDn depends on the distribution n(PThz), with the most important parameters being the starting number, n0, at PTHz → 0 and the width δPn.

Figure 1g shows three examples of n(PTHz) for arrays with N = 200 JJs. The leftmost (blue) is the case of a fairly uniform array with large n0 = 50 and narrow δPn = 1/4 δP1; the middle (red) to n0 = 25 and δPn = δP1; and the rightmost (olive) is to the least homogeneous array with small n0 = 10 and broad δPn = 2 δP1. Here δP1 is the response width of SCD1, shown by the red line in Fig. 1f. Figure 1h represents the corresponding array responses, ΔVn. It is seen that a wider δPn expands the dynamic range but reduces the response.

Figure 1i shows the cascade gain ΔVn/ΔV1. Remarkably, it can be significantly larger than n. The overshooting is caused by the second term in Eq. (6), which provides the key advantage of SCDn and raises the signal-to-noise ratio by increasing the signal and obviating telegraph noise. Interestingly, this pure cascade gain term is associated with an imperfect current-locking, ∂n/∂P, implying that some imperfection is beneficial for SCDn.

Microwave detection

We studied MW and THz responses of linear Nb/NbxSi1−x/Nb JJ arrays and stacked IJJs in Bi-2212 whiskers. Fabrication and physical properties of Nb arrays were described in refs. 49,53,54,55. Details about the fabrication and characterization of Bi-2212 devices can be found in refs. 29,32,56. All presented measurements were performed at ambient magnetic field and T ≃ 3.3 K. See Methods and Supplementary sec. SVII–IX for more experimental details and additional data.

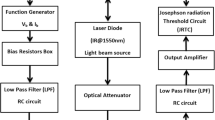

For MW detection, devices were irradiated quasi-optically by a linearly polarized source at f ≃ 74.5 GHz. MW attenuation, μ, and polarization angle, Θ, were adjusted by grid polarizers. A Golay cell detector was used to monitor the incoming MW power.

Figure 2a shows the I–Vs of a Nb array with N = 128 JJs, measured upon minor variation of the bias current in the absence of MW. Multiple branches correspond to a different number, n, of active JJs. The interjunction coupling in these arrays is mediated by surface plasmons55 and manifested by the appearance of collective resonant steps in the I–V ’s49.

a Ensemble of the I-V's without irradiation, obtained at slightly different bias currents. The inset shows the array layout. b The array voltage response (blue symbols, left axis) and the number of active junctions, n, (red line, right axis) as a function of microwave power, f = 74.5 GHz, normalized on Pmax ≃ 14 nW. c Array response, V and n, as a function of the polarization angle, Θ, at constant microwave power. The inset shows the polarization loss diagram. The orange line marks the array direction. Profound off-axis lobes manifest the traveling-wave antenna effect.

Figure 2b shows the MW response of the array. With increasing PMW, progressively more JJs switch to the resistive state (red line) leading to an increase in array voltage (blue symbols). A correlation V ∝ n illustrates the cascade amplification phenomenon. At higher power, all N = 128 JJs switch, and the responsivity dV/dP is greatly reduced. In this case, it is due solely to the decrease of Is(P), the first term in Eq. (6), qualitatively similar to a single-JJ SCD115,29.

To analyze the absorption efficiency, we measured the polarization loss diagram57. Figure 2c shows the array voltage (blue symbols) and the number of active JJs (red line) as a function of the polarization angle, Θ, at a constant PMW. Θ = 0 corresponds to the MW electric field parallel to the array line. The inset displays the polarization-loss diagram, ΔV/VG(Θ), where VG ∝ PMW is the Golay cell voltage (constant in this experiment). The diagram exhibits two profound lobes at Θ ≃ 50∘ and −130∘ with respect to the array. The off-axis behavior is consistent with the traveling-wave antenna operation of long electrodes reported for such arrays54,55. The estimated optical absorption efficiency of this array is χ ≃ 7% (see Methods).

Figure 3a represents a scanning electron microscope (SEM) image of one of the Bi-2212 devices based on whisker-type single crystals32. Several mesas, containing stacked IJJs, were formed at the intersection of the whisker with the top gold electrodes, as sketched in Fig. 3f. To reduce Ic and increase sensitivity, some mesas were trimmed using focused ion beam29,56.

a A scanning electron microscope image of a whisker-based device. b Two I-V characteristics of a mesa with N = 250 intrinsic junctions, measured at different bias amplitudes in the absence of irradiation. c Red circles represent measured temperature dependence of the width of switching current histograms for a single intrinsic junction. The blue line is calculated from Eq. (3). The inset shows the measured switching current histogram (red) and the calculated switching probability density (blue line) at T = 4.2 K. d Ensemble of the I-Vs for different microwave (MW) powers, determined by the attenuation factor μ, at constant Ib = 38.1 μA. e The mesa voltage (symbols) and the number of active junctions, n, (lines) versus the MW power, for Ib = 25.3 and 38.1 μA. f The polarization-loss diagram. The blue line indicates the orientation of the whisker. The yellow background shows the large-scale electrode geometry. The four-fold symmetry is consistent with the turnstile-antenna geometry of the device, as sketched in the inset.

Figure 3b shows two I-V ’s of a mesa ( ~5 × 5 μm2), with N ≃ 250 IJJs. The blue curve, with n = 117 active IJJs, was measured with Ib slightly above the mean switching current, Is ~ 50 μA. The multi-branch structure ends at V ≃ 5 V, corresponding to the large Vc ≃ 20 mV per IJJ. Switching of the first and the last IJJ occurs within an interval, δIn ~ 5 μA ~ 0.1 Is. Statistical analysis of multi-junction switching can be found in the Supplementary sec. SIV.

The inset in Fig. 3c shows a switching histogram (red) for a single IJJ in another mesa. The solid line is the expected probability density at the base T. Red circles in the main panel show the measured T-dependence of the FWHM. The blue line was obtained from Eq. (3). Overall agreement is excellent, indicating that IJJs are well described by the SCD formalism58.

Figure 3d shows the I-Vs of the third mesa at different MW powers and Ib = 38.1 μA. The cascade gain depends on Ib. Figure 3e represents the MW power dependencies of V (symbols) and n (lines), measured at two biases. At lower Ib = 25.3 μA, the sensitivity, dV/dP, remains small up to some threshold, PMW ~0.2 Pmax. At higher Ib = 38.1 μA, there is no threshold and the sensitivity is high at PMW → 0. With a further increase of Ib, the sensitivity remains high at PMW → 0, but saturates at successively smaller power, thus reducing the dynamic range15. Ib = 38.1 μA is the optimal bias amplitude with both high sensitivity and large dynamic range. For comparison, in the Supplementary sec. SIX we analyzed the ordinary SCD operation on the same mesa using a single surface IJJ. The surface IJJ had a much smaller Is38 and could be measured without activation of other IJJs29. The maximum single-junction response is almost 1000 times smaller than for the cascade SCD in Fig. 3e at the same MW power for the same mesa.

Figure 3f shows the polarization-loss diagram of this mesa. It has a four-fold shape with two smaller lobes aligned with the whisker. The larger lobes are approximately perpendicular, slightly inclined in the direction of one of the bias electrodes (see the Supplementary sec. SIX for more details). The large-scale electrode geometry of this device is shown in the background (yellow). The observed four-fold diagram is consistent with the turnstile-antenna geometry of the device59,60, as sketched in the inset. The estimated optical absorption efficiency, χ ≃ 9% (see Methods), is consistent with the emission efficiency reported for similar mesas32.

Detection of THz radiation from a Bi-2212 mesa

To verify THz operation, we performed an in-situ generation-detection experiment in which one mesa emits radiation and a nearby mesa detects it29,32. Figure 4a shows the I–V of a generator mesa (~10 × 15 μm2), containing N = 160 ± 10 IJJs. We analyzed the downturn part of it (magenta) when all IJJs are active. In this case, the Josephson frequency is well defined, fJ = 2eV/hN, as indicated by the top axis. The emission occurs at the cavity modes in the mesa29,43,44. The key signature of such emission (as opposed to heating) is the non-monotonous dependence of the signal on the dissipation power, Pgen = IgenVgen, with distinct peaks at cavity resonances29.

a The I–V characteristics of the generator mesa for upward (blue) and downward (magenta) bias sweeps. Top axis indicates the anticipated Josephson frequency. b, c Low-bias I-V's of the detector mesa with c showing the I–V of the weak surface junction. d Measured detector responses versus total generator power, Pgen = IgenVgen. The magenta curve represents the cascade detector mesa response. The sharp peaks correspond to emission at cavity mode resonances in the generator mesa, the monotonous background is caused by self-heating. The olive line represents a single surface junction response (multiplied by a factor 50) on the same mesa. e A set of detector I–V characteristics with fixed Ib = 370 μA at different bias points of the generator, marked by the same-color circles in (a) and (d). It can be seen that the response is caused predominantly by the cascade gain.

Figure 4b shows low-bias part of the I-V of a detector mesa ( ~ 15 × 15 μm2), about 22 μm away from the generator. A close-up in Fig. 4c represents the I-V of the weak surface junction. It had \({I}_{c}^{{\prime} }\simeq 15\,\mu\)A, significantly lower than Ic ≃ 370 μA for the rest of the IJJs. This disparity allowed SCD1 measurements at \({I}_{c}^{{\prime} } < {I}_{b}\ll {I}_{c}\)29. Cascade detection could be performed on the same mesa by increasing the bias to Ib ~ Ic.

Figure 4d shows SCD1 (olive, × 50) and SCDn (magenta) responses measured at Ib = 25 and 370 μA, respectively. It can be seen that (in this case) the resolution of SCD1 is not sufficient to resolve the emission. The SCDn shows a much larger response with clear emission peaks. The main emission for this mesa occurs in the range from ~4 to 8.4 THz, as indicated in the top axis. The upper frequency is limited by self-heating of the generator mesa at large bias32,42, which also leads to a monotonous upward drift of the detector signal at Pgen > 2 mW (see Supplementary sec. SX for the discussion of self-heating).

Figure 4e shows the detector I-V’s measured with Ib = 370 μA at several bias points of the generator, marked by the same-color circles in Fig. 4a, d. It can be seen that the cascade amplification factor, n, plays a dominating role in the detector response.

Discussion

We observed similar behavior for low- and high-Tc devices, either linear arrays or stacks. Both types of detectors have some advantages. 2D-linear arrays facilitate a large absorption area and simple scalability to tens of thousands of JJs53, while Bi-2212 devices can operate in the whole THz range [0.1-10] THz29.

MW measurements, performed under identical conditions, allow for quantitative comparison of the two devices (see Methods). Although the sensitivity of Bi-2212 is almost hundred times higher, the NEP’s are similar ≃ 3 pW/Hz1/2. This is a consequence of dominant telegraph noise, Eq. (4), which scales with Vc, making the NEP approximately independent of Vc. Therefore, the relevant SCD figure of merit is NEPn, rather than Sn.

The new detection mechanism, when the response is caused by the pure cascade gain without suppression of Is, is central for SCDn. It increases sensitivity, leading to overshooting, Vn/V1 > n. For example, for the olive line in Fig. 1i, the gain at PTHz → 0 is 7.3 times greater than n0 = 10. Even more importantly, this mechanism allows for partial obviation of the telegraph noise.

The statistical uncertainty of an array, Eq. (7), is contributed by the telegraph noise (first) and the gain uncertainty (second term). Unlike SCD1, SCDn can operate at \({G}_{n}^{*}=1\), when the array always switches into the resistive state at every bias cycle and the signal is carried only by the pure cascade gain, ∂n/∂P. In this case the telegraph noise term vanishes, the noise reduces to

the sensitivity is Sn = Vc∂n/∂P ≃ VcN/χδPn, yielding

The N−1 dependence reflects the benefit of cascading.

All measurements presented here were performed in the pure gain mode, with the exception of high power range when suppression of Is also contributed to the response. The latter is clearly distinguishable in Fig. 2b at P/Pmax > 0.6, when cascade gain is saturated, n = N. Apparently, the ordinary sensitivity in this range is much smaller than the cascade sensitivity at lower power.

The MW NEPs of both detectors, ~3 pW/Hz1/2, are consistent with Eq. (9). They are modest due to low fb = 23 Hz and imperfect impedance matching, χ < 0.1. Similar arrays (T = 3 K, Ic0 = 50 μA) with slightly more JJs, optimal χ = 0.5 and higher fb = 230 kHz would reach NEP ~ 1 fW/Hz1/2.

The ultimate limit of NEP is determined by the two main tuning parameters of SCD: T and Ic0.

The decrease of T leads to freezing out of thermal fluctuations and shrinking of switching histograms, Eq. (3). This enhances the sensitivity ∝ 1/δIs1 (see Supplementary sec. III). The limit is set by the crossover temperature to macroscopic quantum tunneling (MQT)4,22,23,26,28,34,58, qualifying SCD as a quantum-limited detector. For TMQT = 30 mK the improvement will be a factor [3.3K/30mK]2/3 ≃ 23, bringing NEP at Ic0 = 50 μA to the ~ 50 aW/Hz1/2 level.

The decrease of Ic0 lowers EJ0 and increases sensitivity approximately as S1 ∝ 1/Ic015. However, at Ic0 ≲ kBT/Φ0 the potential well becomes so low that thermal fluctuations become capable of moving the particle even without tilt/current. The JJ then enters the phase-diffusion state35, which sets the limit of SCD sensitivity15. However, phase diffusion is not necessarily detrimental. In this state, the JJ is switching in and out at a frequency close to the Josephson plasma frequency fp ~ 100 GHz. Paradoxically, such chaotic dynamics could effectively average away the telegraph noise15. Evidence for the collapse of visible fluctuations at the edge of phase diffusion has been reported58.

Thus, we anticipate that the ultimate NEP is achieved at T = TMQT and \({I}_{c0}^{*} \sim {k}_{B}{T}_{MQT}/{\Phi }_{0}\). For TMQT = 30 mK, \({I}_{c0}^{*} \sim 6\) nA is almost four orders of magnitude smaller than 50 μA assumed in estimations above. This indicates potential for a drastic reduction of NEP, provided the impedance matching and absorption efficiency could be preserved. The ultimate limit of NEP in such quantum phase diffusion state remains an interesting question for further investigation.

In conclusion, we have introduced the concept of a cascade SCD based on arrays of coupled JJs and demonstrated prototypes utilizing both low- and high-Tc superconductors. Counterintuitively, some inhomogeneity has been shown to be beneficial for cascade SCD because it enables a new operation mode, which enhances the detector sensitivity while simultaneously reducing statistical noise, thus lowering the noise equivalent power. We developed qualitative and quantitative methods to evaluate antenna efficiency and optical absorption and showed that Bi-2212 detectors operate effectively across a broad THz frequency range.

Methods

Experimental details

Measurements were performed in a closed-cycle optical cryostat with a base temperature ~3.3 K at zero magnetic field. Arrays were current-biased using a programmable source. The I–Vs were measured in a quasi 4-probe configuration. Additional information about experimental setup, bias configuration, and microwave measurements can be found in sec. SVII of the Supplementary. Details about fabrication and characterization of Nb arrays and Bi-2212 mesas are provided in sec. SVIII and SIX.

The operation of SCD requires statistical analysis. The switching statistics of Bi-2212 mesas for single and multi-junction switching can be found in sec. SIV of the Supplementary. It is well described by conventional thermal-activation theory, described in sec. SII.

The SCD response was measured via lock-in measurements. For this, a harmonic current, \(I={I}_{b}\sin (2\pi {f}_{b}t)\), with the amplitude Ib and frequency fb = 23 Hz was supplied for a time interval of 1 s. The read-out voltage corresponds to the Fourier component of the detector V(t) wave form at f = fb. The lock-in response was calculated on-flight by the FPGA-based FFT routine. Additional information about SCD operation and lock-in readout can be found in sec. SI and SV.

Quantitative estimation of detector characteristics

The incoming MW power was measured using a cryostat as a bolometer. The sample stage in our cryostat has a thermal resistance, Rth ≃ 0.5 K/mW32. By measuring a small temperature rise ΔT ~ mK, caused by the MW beam, we directly measured the total incoming power, Ptot = ΔT/Rth. Due to the large λ0 ≃ 4 mm and significant diffraction at several narrow (≃1 cm) apertures of the cryostat, the MW power density was fairly uniform, q = Ptot/πr2. Here, r ≃ 1.5 cm is the radius of the sample space. MW power impacting on SCD was calculated as P = qA, where A ≃ 1 mm2 is the effective absorption area of the receiving antenna, formed by the electrodes. Thus, we obtained Pmax ≃ 14 nW.

The calibration of PMW allows a straightforward estimation of the linear optical response at low power, using the V(P) dependencies from Figs. 2b and 3e. For Bi-2212, SMW ≃ 1.3 108 V/W. For the Nb-array, ∂V/∂P is changing with P, Fig. 2b. The variation is caused by the one-polarizer configuration used in this measurement, in combination with the sharp polarization diagram, Fig. 2c. The sensitivity at the lobe is ~ 2 106 V/W.

The noise measurements presented in Supplementary Fig. S6 reveal a statistical uncertainty, δV ≃ 2 10−4 V/Hz1/2 for the Bi-2212 device. This is consistent with Eq. (8) for the actual Vc ≃ 5 mV, fb = 23 Hz, and δn = 1. The large uncertainty limits the optical MW NEP(Bi-2212) to ~3 pW/Hz1/2.

Alternatively, the NEP can be estimated from Eq. (9). For the Bi-2212 detector, V(P) in Fig. 3e indicates that δPn ≃ 0.2Pmax. For the actual parameters (δn = 1, N = 74), this results in essentially the same optical NEPMW ≃ 2.8 pW/Hz1/2 for Bi-2212. Similar analysis for the Nb-array (δn = 1, δPn = 0.4 Pmax see Fig. 2b, N = 128) yields NEPMW ≃ 3.2 pW/Hz1/2. The agreement in obtained NEP values confirms the validity of Eqs. (8) and (9).

At high power, when the suppression of switching current, ΔIs, becomes distinct, it is possible to directly estimate the absorbed power29:

For the Bi-2212 detector from Fig. 5d, ΔIs ≃ 3 μA at 3.7 dB attenuation. Taking Ic0 = 38 μA, Vc = 5 mV we obtain Pa ≃ 1.3 nW. Thus, the optical MW absorption efficiency is χ = Pa/PMW ≃ 9%. This value is comparable to the observed emission efficiency for similar Bi-2212 mesas (albeit at different frequencies)32, supporting our calibration of Pmax.

For the Nb array, a similar estimation yields χ ≃ 7%. The absorption efficiencies for both types of detectors are several times smaller than the optimal value, which for JJs is less than 50% due to the presence of the quasiparticle leakage current24. Thus, the impedance matching in our detectors is not ideal. Nevertheless, antenna elements on our devices provide decent coupling to the radiation field, as evidenced by the geometry-specific polarization loss diagrams.

For the THz generation-detection experiment in Fig. 4, we could not confidently estimate the incoming power. However, the absorbed power can be estimated in the same way using Eq. (10). For the green I-V in Fig. 6e at fJ = 7.99 THz, the suppression of the switching current is ΔIs = 35 μA. With Ic0 = 390 μA, Vc = 16 mV and V ≃ 1 V it yields Pa ≃ 50 nW and Sa ≃ 2 107 (V/W). A similar analysis for the violet curve at fJ = 6.84 THz yields Sa ≃ 3.5 107 V/W.

Note that the sensitivities obtained with the help of Eq. (10) are several times smaller than the estimated linear responses. The main reason for that is that a confident estimate of ΔIs could be made only at high power, when detectors are already in the saturation state.

Data availability

Data supporting the findings of this study are available from the manuscript and its Supplementary Information. The data is available from the corresponding author upon request.

References

Zhang, M. & Yeow, J. T. W. Nanotechnology-based terahertz biological sensing. IEEE Nanotechn. Mag. 10, 30 (2016).

Lewis, R. A. A review of terahertz detectors. J. Phys. D Appl. Phys. 52, 433001 (2019).

Eisaman, M. D., Fan, J., Migdall, A. & Polyakov, S. V. Invited review article: single-photon sources and detectors. Rev. Sci. Instrum. 82, 071101 (2011).

Inomata, K. et al. Single microwave-photon detector using an artificial Λ-type three-level system. Nat. Com. 10, 12303 (2016).

Kono, S., Koshino, K., Tabuchi, Y., Noguchi, A. & Nakamura, Y. Quantum non-demolition detection of an itinerant microwave photon. Nat. Phys. 14, 546–549 (2018).

Ilinskaya, O. A., Ryzhov, A. I. & Shevchenko, S. N. Flux qubit-based detector of microwave photons. Phys. Rev. B 110, 155414 (2024).

Day, P. K., LeDuc, H. G., Mazin, B. A., Vayonakis, A. & Zmuidzinas, J. A broadband superconducting detector suitable for use in large arrays. Nature 425, 817 (2003).

Wei, J. et al. Ultrasensitive hot-electron nanobolometers for terahertz astrophysics. Nat. Nanotech. 3, 496–500 (2008).

Kuzmin, A. et al. Terahertz transition-edge sensor with kinetic-inductance amplifier at 4.2K. IEEE Trans. THz Sc. Techn. 6, 622 (2018).

Shurakov, A., Lobanov, Y. & Goltsman, G. Superconducting hot-electron bolometer: from the discovery of hot-electron phenomena to practical applications. Supercond. Sci. Technol. 29, 023001 (2016).

Echternach, P. M., Pepper, B. J., Reck, T. & Bradford, C. M. Single photon detection of 1.5 THz radiation with the quantum capacitance detector. Nat. Astr. 2, 90 (2018).

Kokkoniemi, R. et al. Bolometer operating at the threshold for circuit quantum electrodynamics. Nature 586, 47 (2020).

Shi, Q. et al. Terahertz superconducting kinetic inductance detectors demonstrating photon-noise-limited performance and intrinsic generation-recombination noise. Sci. China 65, 239511 (2022).

Lau, J. A., Verma, V. B., Schwarzer, D. & Wodtke, A. M. Superconducting single-photon detectors in the mid-infrared for physical chemistry and spectroscopy. Chem. Soc. Rev. 52, 921 (2023).

Krasnov, V. M. Resonant switching current detector based on underdamped Josephson junctions. Phys. Rev. Appl. 22, 024015 (2024). Erratum. ibid.23, 049901 (2025).

Day, P. K. et al. A 25-micrometer single-photon-sensitive kinetic inductance detector. Phys. Rev. X 14, 041005 (2024).

Auton, G. et al. Terahertz detection and imaging using graphene ballistic rectifiers. Nano Lett. 17, 7015 (2017).

Walsh, E. D. et al. Josephson junction infrared single-photon detector. Science 372, 409–412 (2021).

Gayduchenko, I. et al. Tunnel field-effect transistors for sensitive terahertz detection. Nat. Com. 12, 543 (2021).

Komiyama, S., Astafiev, O., Antonov, V., Kutsuwa, T. & Hirai, H. A single-photon detector in the far-infrared range. Nature 403, 405 (2000).

Kajihara, Y., Nakajima, T., Wang, Z. & Komiyama, S. Terahertz single-photon detectors based on quantum wells. J. Appl. Phys. 113, 136506 (2013).

Poudel, A., McDermott, R. & Vavilov, M. G. Quantum efficiency of a microwave photon detector based on a current-biased Josephson junction. Phys. Rev. B 86, 174506 (2012).

Oelsner, G. et al. Detection of weak microwave fields with an underdamped Josephson junction. Phys. Rev. Appl. 7, 014012 (2017).

Krasnov, V. M. A distributed active patch antenna model of a Josephson oscillator. Beilstein J. Nanotechnol. 14, 151 (2023).

Balanis, C.A. Antenna Theory: Analysis and Design 3rd ed. (Wiley, 2005).

Martinis, J. M., Devoret, M. H. & Clarke, J. Experimental tests for the quantum behavior of a macroscopic degree of freedom: the phase difference across a Josephson junction. Phys. Rev. B 35, 4682 (1987).

Grønbech-Jensen, N. et al. Microwave-induced thermal escape in Josephson junctions. Phys. Rev. Lett. 93, 1007002 (2004).

Andersen, C. K. & Mølmer, K. Effective description of tunneling in a time-dependent potential with applications to voltage switching in Josephson junctions. Phys. Rev. A 87, 052119 (2013).

Borodianskyi, E. A. & Krasnov, V. M. Josephson emission with frequency span 1-11 THz from small Bi2Sr2CaCu2O8+δ mesa structures. Nat. Commun. 8, 1742 (2017).

Revin, L. S. et al. Microwave photon detection by an Al Josephson junction. Beilstein J. Nanotechnol. 11, 960–965 (2020).

Pavlovskiy, V. V., Gundareva, I. I., Volkov, O. Y. & Divin, Y. Y. Wideband detection of electromagnetic signals by high-Tc Josephson junctions with comparable Josephson and thermal energies. Appl. Phys. Lett. 116, 082601 (2020).

Cattaneo, R., Borodianskyi, E. A., Kalenyuk, A. A. & Krasnov, V. M. Superconducting terahertz sources with 12% power efficiency. Phys. Rev. Appl. 16, L061001 (2021).

Chiarello, F. et al. Investigation of resonant activation in a Josephson junction for axion search with microwave single photon detection. IEEE Trans. Appl. Supercond. 32, 1100305 (2022).

Devyatov, I. A., Kuzmin, L. S., Likharev, K. K., Migulin, V. V. & Zorin, A. B. Quantum-statistical theory of microwave detection using superconducting tunnel junctions. J. Appl. Phys. 60, 1808–1828 (1986).

Kautz, R. L. & Martinis, J. M. Noise-affected I-V curves in small hysteretic Josephson junctions. Phys. Rev. B 42, 9903 (1990).

Katterwe, S. O., Motzkau, H., Rydh, A. & Krasnov, V. M. Coherent generation of phonon-polaritons in Bi2Sr2CaCu2O8+x intrinsic Josephson junctions. Phys. Rev. B 83, 100510(R) (2011).

Krasnov, V. M. Interlayer tunneling spectroscopy of Bi2Sr2CaCu2O8+δ: a look from inside on the doping phase diagram of high-Tc superconductors. Phys. Rev. B 65, 140504(R) (2002).

Krasnov, V. M. Temperature dependence of the bulk energy gap in underdoped Bi2Sr2CaCu2O8+δ: evidence for the mean-field superconducting transition. Phys. Rev. B 79, 214510 (2009).

Kleiner, R. & Müller, P. Intrinsic Josephson effects in high-Tc superconductors. Phys. Rev. B 49, 1327 (1994).

Ozyuzer, L. et al. Emission of coherent THz radiation from superconductors. Science 318, 1291 (2007).

Benseman, T. M. et al. Powerful terahertz emission from Bi2Sr2CaCu2O8+δ mesa arrays. Appl. Phys. Lett. 103, 022602 (2013).

Kashiwagi, T. et al. Efficient fabrication of intrinsic Josephson-junction terahertz oscillators with greatly reduced self-heating effects. Phys. Rev. Appl. 4, 054018 (2015).

Zhang, H. et al. Resonant cavity modes in Bi2Sr2CaCu2O8+x intrinsic Josephson junction stacks. Phys. Rev. Appl. 11, 044004 (2019).

Ono, Y. et al. Superconducting emitter powered at 1.5 terahertz by an external resonator. Phys. Rev. Appl. 13, 064026 (2020).

Miyamoto, M., Kobayashi, R., Kuwano, G., Tsujimoto, M. & Kakeya, I. Wide-band frequency modulation of a terahertz intrinsic Josephson junction emitter of a cuprate superconductor. Nat. Photon. 18, 267 (2024).

Grebenchuk, S. Y. U., Cattaneo, R. & Krasnov, V. M. Nonlocal long-range synchronization of planar josephson-junction arrays. Phys. Rev. Appl. 17, 064032 (2022).

Golod, T., Kapran, O. M. & Krasnov, V. M. Planar superconductor-ferromagnet-superconductor Josephson Junctions as scanning-probe sensors. Phys. Rev. Appl. 11, 014062 (2019).

LeFebvre, J. C., Cho, E., Li, H., Pratt, K. & Cybart, S. A. Series arrays of planar long Josephson junctions for high dynamic range magnetic flux detection. AIP Adv. 9, 105215 (2019).

Cattaneo, R., Galin, M. A. & Krasnov, V. M. Observation of collective excitation of surface plasmon resonances in large Josephson junction arrays. Beilstein J. Nanotechnol. 13, 1578–1588 (2022).

McCrath, W. R., Räisänen, A. V., Richards, P. L., Harris, R. E. & Lloyd, F. L. Accurate noise measurements of superconducting quasiparticle array mixers. IEEE Trans. Magn. 21, 212 (1985).

Shitov, S. V. et al. Ultra-low-noise 100GHz receiver based on parallel biased SIS arrays. Supercond. Sci. Techn. 4, 406 (1991).

Siddiqi, I. et al. Direct observation of dynamical bifurcation between two driven oscillation states of a Josephson junction. Phys. Rev. Lett. 94, 027005 (2005).

Mueller, F. et al. 1 V and 10 V SNS programmable voltage standards for 70 GHz. IEEE Trans. Appl. Supercond. 19, 981–986 (2009).

Galin, M. A. et al. Synchronization of large Josephson-Junction arrays by traveling electromagnetic waves. Phys. Rev. Appl. 9, 054032 (2018).

Galin, M. A. et al. Direct visualization of phase-locking of large Josephson junction arrays by surface electromagnetic waves. Phys. Rev. Appl. 14, 024051 (2020).

Krasnov, V. M., Katterwe, S.-O. & Rydh, A. Signatures of the electronic nature of pairing in high-Tc superconductors obtained by non-equilibrium boson spectroscopy. Nat. Commun. 4, 2970 (2013).

IEEE Standard Test Procedures for Antennas, in ANSI/IEEE Std 149-1979, 30 Nov. (1979) https://doi.org/10.1109/IEEESTD.1979.120310.

Krasnov, V. M. et al. Collapse of thermal activation in moderately damped Josephson junctions. Phys. Rev. Lett. 95, 157002 (2005).

Krasnov, M. M., Novikova, N. D., Cattaneo, R., Kalenyuk, A. A. & Krasnov, V. M. Design aspects of Bi2Sr2CaCu2O8+δTHz sources: optimization of thermal and radiative properties. Beilstein J. Nanotechnol. 12, 1392 (2021).

The directivity of turnstile antenna depends on the phase shift between two dipoles, which we can not control, and on the mode number. Therefore, there could be a large variety of directivities, see e.g. [25]. Nevertheless, the observed four-fold polarization dependence is a clear evidence for the geometry-related antenna effect.

Acknowledgements

We are grateful to R. Gerdau and M. Galin for assistance with fabrication of Nb-arrays and to A. Kalenyuk for assistance with fabrication of Bi-2212 samples.

Funding

Open access funding provided by Stockholm University.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

R.G., K.I.S. and O.K. fabricated samples. R.G. and A.E.E. performed measurements. V.M.K. conceived the project and wrote the paper with input from all co-authors.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Peer review

Peer review information

Nature Communications thanks Itsuhiro Kakeya and the other anonymous reviewer(s) for their contribution to the peer review of this work. A peer review file is available.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Cattaneo, R., Efimov, A.E., Shiianov, K.I. et al. Cascade switching current detectors based on arrays of Josephson junctions. Nat Commun 16, 7927 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-025-63360-y

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-025-63360-y

This article is cited by

-

Planar Josephson Junctions for Sensors and Electronics

Journal of Superconductivity and Novel Magnetism (2026)