Abstract

Electrocatalysis plays a central role in clean energy conversion and sustainable technologies. However, the trade-off between activity and stability of electrocatalysts largely hinders their practical applications, notably in the oxygen evolution reaction for producing hydrogen and solar fuels. Here we report a steam-assisted synthesis armed with machine learning screening of an integrated Ru/TiMnOx electrode, featuring intrinsic metal-support interactions. These atomic-scale interactions with self-healing capabilities radically address the activity-stability dilemma across all pH levels. Consequently, the Ru/TiMnOx electrode demonstrate enhanced mass activities—48.5×, 112.8×, and 74.6× higher than benchmark RuO2 under acidic, neutral, and alkaline conditions, respectively. Notably, it achieves stable operation for up to 3,000 h, representing a multi-fold stability improvement comparable to other state-of-the-art catalysts. The breakthrough in activity-stability limitations highlights the potential of intrinsic metal-support interactions for enhancing electrocatalysis and heterogeneous catalysis in diverse applications.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The global energy crisis and climate issues urgently call for the development of sustainable green energy technologies1,2,3. Electrocatalysis is key to clean energy conversion, driving multiple sustainable processes for future technologies1,2,3,4,5. However, the dilemma between the catalytic activity and the stability imposes fundamental limitations on the practical applications6,7,8,9. Typically, the oxygen evolution reaction (OER) is crucial in various renewable energy conversion and storage systems7,8,9,10,11,12,13,14, especially for hydrogen (H2) production through water electrolysis (WE)2,3,4,5,7,8,9,10,12. The activity-stability tradeoff in OER, arising from the formation of highly active yet soluble Mx+ species, greatly hinders large-scale WE deployment15,16,17. Therefore, overcoming these conventional constraints has been a long-pursued goal in OER and other catalysis research, yet remains extremely challenging.

To date, supported metal catalysts (SMCs) have been regarded as promising candidates for electrocalysis and heterogeneous catalysis17,18,19. By manipulating active metal species at nanoscale or even atomic scale, maximal intrinsic activity can be achieved17,18,19,20,21,22. Unfortunately, the inherently high surface free energy in atomic-scale metal species often drives atom aggregation and activity loss17,18,21,23. Previous studies have focused on modulating the metal-support interactions to prevent metal dissolution in SMCs17,18,19,20,21,22,23. Strategies such as post-treatment24,25,26,27, defect engineering28,29,30,31,32,33 and cation exchange4,15,34,35 have been employed to strengthen these interactions. However, these strategies typically involve support growth and metal loading through a stepwise bond-breaking and reformation process15,24,28,29,30,31,32. The resultant extrinsic metal-support interactions still fails to address the activity-stability dilemma fundamentally. Furthermore, most reported SMCs are in powder form and require binder coating for electrode preparation, thereby compromising catalyst-substrate adhesion and charge transfer efficiency4,15,28,29,30,31,32,33,34,35. Growing SMCs directly on the substrate offers potential for achieving both intrinsic metal-support and catalyst-substrate interactions, leading to a radical enhancement in stability without compromising activity. Prior studies have not experimentally resolved atomic-scale metal-support interactions, particularly with regard to OER under pH-universal conditions.

In this work, we develop a one-step chemical steam deposition (CSD) strategy to fabricate a Ru/TiMnOx electrode with atomic-scale metal-support interactions. This integrated structure overcomes the activity-stability trade-off in pH-universal OER. The key to the CSD strategy was the introduction of potassium permanganate (KMnO4) to obtain gaseous Ru species, ensuring atomic/molecular-scales reaction for achieving intrinsic interactions. Using machine learning, the optimal composition balancing both activity and stability metrics has been screened. The best-performing Ru0.24/Ti0.28Mn0.48O electrode exhibited high mass activities, ~49, 113, and 75 times those of RuO2 under acidic, neutral, and alkaline conditions, respectively; and outstanding long-term durability for up to 3,000 h. Our findings demonstrate a machine learning-guided steam deposition strategy for atomic-level synthesis of nano-metal oxides, enabling tunable interfacial properties applicable across pH-universal conditions

Results

Synthesis of integrated electrode with intrinsic metal-support interactions

A one-pot chemical steam deposition (CSD) strategy was developed to fabricate an integrated Ru/TiMnOx electrode (Fig. 1a, Methods, Supplementary Figs. 1 and 2, and Supplementary Discussion 1). Under hydrothermal conditions, solution-derived RuO4 and KMnO4 volatilized into gas phases. These precursors then reacted with the Ti substrate, enabling Ru embedding at nanoscale within TiMnOx lattices. KMnO4 played a pivotal role in the CSD strategy, not only as a Mn source but also as a strong oxidant that oxidizes Ru3+ into RuO4 gas precursors. RuO4, acting as a gaseous reactant, directly diffused to the Ti substrate surface in molecular form and rapidly accumulated through physical adsorption or chemical interactions. Upon reaching local supersaturation at the Ti interface, RuO4 underwent immediate reduction and nucleated on the substrate surface, forming an interlayer dominated by Ru nanoclusters36,37. As the reaction progressed, the RuO4 concentration near the substrate decreased due to rapid consumption, shifting the reaction mechanism from diffusion-controlled kinetics (fast reduction under high-concentration conditions) to surface reaction-controlled kinetics (slow deposition at low concentrations)38,39. Concurrently, KMnO4 participated as a co-deposition agent under critical conditions, competing with RuO4 for reduction40,41. This phenomenon could potentially explain the suppression of Ru nanocluster formation while enabling atomic-level incorporation of Ru into the TiMnOx lattice. Consequently, these collective processes likely contributed to the formation of the catalytic layer with atomically dispersed Ru species, which constituted the dominant component of Ru/TiMnOx. To validate the CSD synthesis mechanism, we devised an apparatus that ensures the exclusive production of gas-phase products throughout the hydrothermal process. By positioning the Ti substrate onto apparatuses of diverse dimensions, Ru/TiMnOx with distinct electrode areas were successfully fabricated (Supplementary Fig. 2). This strategy provides the initial demonstration of scalable steam-assisted hydrothermal synthesis for nanomaterials.

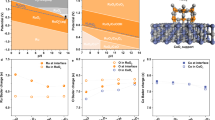

a Schematic illustration of the one-step synthesis of Ru/TiMnOx. b X-Ray diffraction (XRD) patterns of Ru/TiMnOx with different Ru, Ti, and Mn ratios. c Overall machine learning diagram, showing the steps of experimentation, feature extraction, and validation. d, e Predicted OER overpotential (η) and deactivation rate (ΔE) with various ternary compositions.

Employing the CSD strategy, we synthesized Ru/TiMnOx electrodes with varying compositions. As the Ru ratio increases (Fig. 1b, from bottom to top), the peak of Ru/TiMnOx located at 59.3° shifts to a lower angle. This low-angle shift aligns with Bragg’s law, indicating an expansion of the lattice parameters due to the substitutional incorporation of Ru atoms into the TiMnOx matrix, where Ru ions replaced smaller Mn and Ti ions42,43. Subsequently, we evaluated their OER performance based on both experimental overpotential (η) and deactivation rate (ΔE) indicators (Supplementary Fig. 3 and Supplementary Table 1). Given the requirement for an ideal catalyst to exhibit concurrently high activity and stability, we employed machine learning analysis to predict the OER performance of Ru/TiMnOx using both activity and stability indicators as inputs (Fig. 1c, Supplementary Fig. 4 and Supplementary Table 2). The OER η and ΔE of catalysts with different Ru-Ti-Mn ratios are presented in a ternary composition diagram with the molar ratios among the constituent elements on the vertices (Fig. 1d, e). The regions exhibiting the lowest η and ΔE were highlighted in yellow circles, with their overlapping areas indicating the optimal composition range, specifically (Ru-Ti-Mn: 0.20–0.50, 0.20–0.30, 0.25–0.50). The predicted lowest overpotential to drive a current density of 10 mA cm−2 is 163.0 mV, corresponding to a ratio of 0.26: 0.26: 0.48 (Ru: Ti: Mn).

Based on machine learning predictions, an optimized Ru-Ti-Mn electrode was obtained via the CSD strategy. The crystal structure of Ru/TiMnOx was characterized by X-ray diffraction (XRD) analysis (Fig. 2a and Supplementary Table 3). The absence of characteristic peaks corresponding to Ru species in the XRD pattern suggests that Ru species are highly dispersed on the support15. The Ru-Ti-Mn ratio of the Ru/TiMnOx was determined from the refined occupancies to be ~0.24:0.28:0.48, which is consistent with the machine learning prediction and the data obtained from inductively coupled plasma optical emission spectrometry (ICP-OES; Supplementary Fig. 5). Transmission electron microscopy (TEM) image and corresponding elemental mapping (Fig. 2b) verified a homogeneous distribution of Ru, Mn and Ti. Subsequently, focused ion beam (FIB) milling was employed to prepare cross-sectional slices of the Ru/TiMnOx on the Ti substrate, enabling direct observation of interfacial structures (Supplementary Figs. 6–8). Cross-sectional spherical aberration-corrected high-angle annular dark-field scanning TEM (HAADF–STEM) imaging combined with elemental mapping revealed two layers: (i) an interlayer adjacent to the Ti substrate, where Ru predominantly existed as nanoclusters embedded within Ti-rich oxide domains, and (ii) a catalytic layer (accounting for ~80% of the total thickness) with highly dispersed Ru single-atoms uniformly distributed throughout the TiMnOx matrix. Notably, Mn species exhibited preferential surface enrichment, while Ru and Ti demonstrated complete penetration across the entire oxide film.

a Rietveld refinement analysis of XRD patterns of Ru/TiMnOx and its crystal structure (inset). b TEM image of Ru/TiMnOx and corresponding elemental mapping profile. c, e Aberration-corrected HAADF-STEM images of Ru/TiMnOx. d Inverse-fast Fourier-transform (IFFT) image for (c). f 3D surface plot for (c). g, h Magnified images of (f) and the corresponding STEM intensity profiles presented to directions labeled with α and β boxes.

Furthermore, HADDF-STEM characterization was performed on ultrasonically dispersed Ru/TiMnOx fragments, which were preferentially exfoliated from the outer catalytic layer (Fig. 2c–e and Supplementary Fig. 9). The analysis confirmed the atomic-level incorporation of Ru into the TiMnOx lattice. Additionally, lattice fringes with interplanar spacings of 0.23 nm and 0.25 nm were observed, corresponding to the (020) and (111) planes of cubic Ru/TiMnOx, respectively. The observed crystal structure agreed well with the XRD Rietveld refinement results. The 3D surface plots displayed varying peak heights, where relatively higher peaks correlated with Ru atoms (Fig. 2f–h). The line intensity and weight fraction profiles (Fig. 2g, h and Supplementary Fig. 9c,d) further demonstrated the atomic-level embedding of Ru into the TiMnOx lattice within the dominant catalytic layer, which is a prerequisite for achieving intrinsic metal-support interactions. To highlight the significance of these interactions for OER performance, Ru/MnOx and TiMnOx catalysts were synthesized (Supplementary Figs. 10–12 and Supplementary Table 4).

Breaking the activity-stability tradeoff of electrocatalytic OER in pH-universal conditions

The OER performances of the as-prepared Ru/TiMnOx electrodes were evaluated in electrolytes with different pH values, including pH=0 (0.5 M H2SO4), pH=7 (0.5 M PBS), and pH=14 (1.0 M KOH). Ru/MnOx, TiMnOx and commercial RuO2 (Com. RuO2) were used as references. The OER activities in these three electrolytes across the full pH range showed the same trend: Ru/TiMnOx > Ru/MnOx > Com. RuO2 > TiMnOx (Fig. 3a and Supplementary Fig. 13). Notably, the overpotential of Ru0.24/Ti0.28Mn0.48O under 10 mA cm−2 in acidic conditions (165.2 mV) closely aligns with the prediction of Ru0.26/Ti0.26Mn0.48O (163.0 mV) by machine learning, affirming the validity of the established model. Tafel analysis reveals fast reaction kinetics of Ru/TiMnOx across the investigated pH range (Supplementary Fig. 13d–f). Furthermore, Ru/TiMnOx showed high mass activities, 48.5, 112.8 and 74.6 times those of benchmark Com. RuO2 in acidic, neutral and alkaline conditions, respectively (Supplementary Fig. 14 and Supplementary Table 5). The same trend was also confirmed when the activity was evaluated using the electrochemically active surface area (ECSA) (Supplementary Figs. 15–17), further highlighting the advantages of atomically dispersed Ru species in reducing the noble metal loading amount. The electrochemical impedance spectroscopy (EIS) analysis determined the enhanced charge transfer capabilities of Ru/TiMnOx (Supplementary Fig. 18), revealing notably low charge transfer resistance. The radar charts (Fig. 3b and Supplementary Fig. 19) showed the outstanding OER performance of Ru/TiMnOx under pH-universal conditions from multiple perspectives. Its notable activities are attributed to optimized kinetics from atomically dispersed sites and enhanced mass transfer from an integrated structure. As illustrated in Supplementary Movie 1, the Ru/TiMnOx electrode served directly as the anode for electrocatalytic water splitting, bypassing the use of binders. The rapid generation and detachment of oxygen bubbles on the electrode surface visually demonstrated the notable activity of Ru/TiMnOx.

a Linear sweep voltammetry (LSV) curves of Ru/TiMnOx, Ru/MnOx, TiMnOx, and commercial RuO2 (Com. RuO2) in 0.5 M H2SO4 (pH = 0.3 ± 0.02), 0.5 M PBS (pH = 7.1 ± 0.10) and 1.0 M KOH (pH = 13.9 ± 0.03). Scan rate: 10 mV s-1. b Radar plot comparing the OER performance of Ru/TiMnOx and the reference samples in 0.5 M H2SO4 (pH = 0.3 ± 0.02). c–e Chronopotentiometry curves of Ru/TiMnOx for OER at 10 mA cm−2 in 0.5 M H2SO4 (c), 0.5 M PBS (d) and 1.0 M KOH (e), respectively. The potentials of chronopotentiometry tests are not iR-corrected.

In addition to high OER activity, good stability is another crucial prerequisite for catalysts to realize practical applications. The OER stability in acidic and neutral conditions is particularly challenging5,7,8,44. We investigated OER durability at 10 mA cm−2geo (Fig. 3c–e and Supplementary Fig. 20), a widely adapted benchmark criterion in literature. Specifically, in 0.5 M H2SO4, the overpotential (without iR compensation) of Ru/TiMnOx increased from 175 mV to 185 mV in a 1000 h test, to 198 mV in a 2000 h test, and 205 mV in a 3000 h test (Fig. 3c). The average increase in overpotential was 0.01 mV h-1; this is over 1698 times slower than that of the Com. RuO2 (16.9 mV h−1) (Supplementary Fig. 20a). To date, no catalyst, especially Ru-based materials, has matched such performance of Ru/TiMnOx under acidic OER conditions (Supplementary Table 6). This stability was also notable in both neutral and alkaline conditions (Fig. 3d, e, Supplementary Tables 7 and 8), particularly under the challenging neutral conditions5,44, where it attained a duration of 1500 h (Fig. 3d). Furthermore, Ru/TiMnOx demonstrated notable long-term stability under high current density across the entire pH range. It can stably drive a current density of 100 mA cm−2 for 220 h under acidic conditions, 120 h under neutral conditions, and 140 h under alkaline conditions, respectively (Supplementary Fig. 21). These results demonstrate its potential for practical applications in water electrolysis devices. As a proof of concept, both the integrated proton exchange membrane water electrolyzer (PEMWE) and anion exchange membrane water electrolyzer (AEMWE) utilizing Ru/TiMnOx electrodes were constructed to evaluate the performance under conditions that are representative of practical applications. The devices achieved industrial-grade OER performance, delivering a current density of 1.0 A cm−2 at cell voltages of 1.66 V (PEMWE) and 1.72 V (AEMWE), respectively (Supplementary Figs. 22 and 23). These operational efficiencies outperformed those reported for state-of-the-art catalysts and commercial RuO2 benchmarks, as evidenced by the substantially higher potentials (1.94 V and 1.99 V) to reach equivalent current densities under comparable conditions (Supplementary Table 9). Besides, RuO2-based systems exhibited activity decay within 3000 min (PEMWE) and 6000 min (AEMWE) at 200 mA cm−2, whereas Ru/TiMnOx-based electrolyzers maintained stable operation for over 11,000 min and 10,000 min, respectively. These findings further highlights the competitive advantage of Ru/TiMnOx in OER at high current densities, demonstrating its great potential for scalable water electrolysis technologies. In summary, the performance of Ru/TiMnOx for pH-universal OER demonstrated a multi-fold improvement over other advanced OER electrocatalysts (Supplementary Tables 6–9). Surprisingly, we observed periodic increases and decreases in voltage during the long-term stability tests (see inset in Fig. 3c–e, Supplementary Figs. 21 and 24). We believe that periodic potential fluctuations are linked to the long-term stability of Ru/TiMnOx. Next, a thorough examination of the intrinsic metal-support interactions was conducted to elucidate its impact on OER performance.

Insights into intrinsic metal-support interactions

The electronic configuration and the coordination structure of Ru, Ti and Mn in Ru/TiMnOx were investigated using X-ray photoelectron spectroscopy (XPS) and synchrotron X-ray absorption spectroscopy (XAS). Deconvolution of the Ru 3d spectra revealed oxidation states of metallic Ru0 and oxidized Ru4+ in Ru/TiMnOx and Ru/MnOx45,46,47. For Ru/TiMnOx, the Ru0 component accounted for only ~14% of the total Ru content, whereas in Ru/MnOx, the Ru0 fraction was ~60% (Supplementary Table 10). The minimal Ru0 content in Ru/TiMnOx likely originated from trace Ru nanoclusters, while the predominant Ru0 in Ru/MnOx indicated extensive aggregation of Ru nanoparticles due to weaker metal-support interactions. Notably, compared to RuO2, the Ru 3d5/2 binding energies in Ru/TiMnOx and Ru/MnOx exhibited negative shifts of 0.05 eV and 0.10 eV, respectively (Supplementary Fig. 25a and Supplementary Table 10). This observation indicates a lower Ru oxidation state in both Ru/TiMnOx and Ru/MnOx compared to the stoichiometric Ru(IV) in RuO2, with Ru/TiMnOx displaying a much higher Ru valence than Ru/MnOx. In the Mn 2p spectra, the electronic structure of TiMnOx aligned closely with MnO2, suggesting a Mn(IV)-dominant configuration15,16 (Supplementary Fig. 25b and Supplementary Table 11). Conversely, the Mn 2p3/2 binding energies of Mn3+ for Ru/TiMnOx and Ru/MnOx showed negative shifts of 0.79 eV and 0.11 eV relative to TiMnOx, respectively. These shifts correlate with a reduced Mn oxidation state in the ternary oxides, with Ru/MnOx exhibiting a marginally higher Mn valence compared to Ru/TiMnOx. Ti oxidation states were further elucidated through high-resolution Ti 2p spectra. Both Ru/TiMnOx and TiMnOx exhibited dual Ti3+/Ti4+ character, indicating mixed-valence Ti species in these oxides (Supplementary Fig. 25c and Supplementary Table 12)48,49,50,51,52. Collectively, the XPS results reveal strong electronic interactions among Ru, Mn, and Ti in Ru/TiMnOx. The observed binding energy shifts reflected synergistic charge transfer processes, where Ru served as an electron reservoir while Mn and Ti participated in redox-active cycling. These findings provide critical insights into the electronic structure-property relationships governing the catalytic behavior of these multi-metallic oxides, particularly in electrochemical energy conversion applications. Additionally, in-depth XPS analysis was performed to verify changes in elemental composition and valence states within Ru/TiMnOx (Supplementary Fig. 26). As the etching depth increased, a negative shift in the Ru 3 d binding energy was observed (Supplementary Fig. 26a), concomitant with an increase in the Ru0/Ru4+ ratio from 0.17 (catalytic layer) to 0.26 (interlayer) (Supplementary Fig. 26b and Supplementary Table 13). This trend confirmed the accumulation of metallic Ru0 species at the catalyst-substrate interface, as corroborated by HAADF-STEM cross-sectional imaging, which revealed Ru0 nanoclusters within the interlayer (Supplementary Fig. 8). Concurrently, the elemental depth profile demonstrated a gradual increase in Ru content and a decrease in Mn/Ti concentrations. These observations aligned with cross-sectional elemental mapping, further validating the elemental distribution within the catalytic layer. The Mn species in the lattice are known to enhance the OER activity of the oxide3,4,34, while the Ti species are believed to improve the OER stability, especially in acidic conditions32,53. This metal distribution potentially facilitates bulk Ru migration to replenish surface active sites upon dissolution, contributing to enhanced stability. The cross-sectional imaging (Supplementary Figs. 6–8) and depth-resolved XPS analysis (Supplementary Fig. 26 and Supplementary Table 13) collectively provided evidence supporting the as-proposed growth mechanism of Ru/TiMnOx: RuO4 supersaturation first triggered Ru0 nanocluster formation at the interlayer, followed by atomic Ru incorporation into TiMnOx upon precursor depletion, ultimately forming the dominant component of catalytic layer.

Next, the structural and electronic structure stability of Ru/TiMnOx was investigated. HADDF-STEM images demonstrated that the structure of Ru/TiMnOx remained stable after long-term OER stability test in 0.5 M H2SO4 (Supplementary Fig. 27). Subsequent ICP-MS analysis confirmed that the Ru/TiMnOx sample retained over 90% of Ru and Mn content after stability testing, exhibiting only trace ion leaching (Supplementary Fig. 28). Notably, the Ru retention rate in Ru/TiMnOx was 1.67 times and 2.29 times higher than those of Ru/MnOx and Com. RuO2 reference samples, respectively. The electronic structure stability was then verified through XPS, as no marked changes in the valence states of Ru and Mn in Ru/TiMnOx were observed after OER stability testing (Supplementary Figs. 29 and 30). In contrast, a distinct positive shift in the Ru 3 d binding energy was observed in both Ru/MnOx and Com. RuO2. Notably, the Ru0/Ru4+ ratio in Ru/TiMnOx remained nearly unchanged (from 0.17 to 0.16), whereas that in Ru/MnOx drastically decreased from 1.48 to 0.41 (Supplementary Table 10). These results, combined with ICP-MS findings, indicated that the active sites in Ru/TiMnOx were protected from excessive oxidation-induced dissolution, whereas Ru in the comparison samples underwent severe oxidation and leaching deactivation.

To elucidate the origin of the high OER performance in Ru/TiMnOx, we systematically conducted XAS analysis on Ru, Mn and Ti to clarify its coordination structure (Fig. 4, Supplementary Figs. 31-40 and Supplementary Tables 14-17). The K-edge X-ray absorption near-edge spectroscopy (XANES) spectra of Ru, Mn, and Ti reveal that the oxidation states of Ru, Ti, and Mn in Ru/TiMnOx lay between those of metal foils and +4-valent metal oxides (Fig. 4a, Supplementary Figs. 31, 33 and 35). Notably, the oxidation state of Ru in Ru/TiMnOx was determined to be +3.0, which is higher than that observed in Ru/MnOx (+ 1.1). Conversely, the oxidation state of Mn exhibited an opposing trend, with a valence of +3.1 in Ru/TiMnOx, slightly lower than that in the Ru/MnOx ( + 3.8). These findings are in good agreement with the oxidation state trends identified through XPS analysis, further validating the strong interactions between Ru, Mn and Ti in Ru/TiMnOx. The extended X-ray absorption fine-structure (EXAFS) analysis further elucidated the metal coordination environment in Ru/TiMnOx. The Ru K-edge Fourier-transform (FT) EXAFS spectra (Fig. 4b) indicated dominant coordination of Ru centers with oxygen (Ru-O), while the Ru-Ru scattering path, arising from interlayer Ru nanoclusters36,54, is consistent with the metallic Ru0 component identified in XPS analysis. Notably, a unique Ru-O-M signal (where M represents Ru, Mn or Ti) emerged at ~3.3 Å, distinct from both RuO2 reference and Ru/MnOx control sample (Supplementary Table 14). The FT-EXAFS and wavelet transform (WT) patterns of Mn and Ti also confirmed the formation of M1-O-M2 (where M1 and M2 represent different metallic species among Ru, Mn, or Ti) bridging bonds, demonstrating the presence of strong intrinsic interactions within Ru/TiMnOx (Fig. 4c and Supplementary Figs. 32–36). Since Ti-based bridging bonds are conducive to stabilizing active species32,53, Ti stabilizes the active sites through Ti-O-M bonds, underscoring its critical role in maintaining structural integrity and catalytic performance.

a, b Ru K-edge XANES spectra (a) and Fourier transforms (FT) of k2-weighted Ru K-edge of EXAFS spectra (b) of Ru/TiMnOx and Ru/MnOx, with Ru foil and RuO2 as references. c, FT k2-weighted Mn K-edge EXAFS spectra of Ru/TiMnOx and Ru/MnOx, with Mn foil, Mn2O3 and MnO2 as references. d FT k2-weighted Ru K-edge EXAFS spectra of Ru/TiMnOx, Ru/TiMnOx-OER-10 and Ru/TiMnOx-OER-20, with Ru foil and RuO2 as references. e The plot of coordination number (CN) and radial distance (R) fitted from Ru K-edge EXAFS spectra (see Supplementary Table 14 for details). f Wavelet transforms for the k2-weighted EXAFS signals at Ru K-edge of RuO2, Ru/TiMnOx, Ru/TiMnOx-OER−10 and Ru/TiMnOx-OER-20. k (Å−1): Wave vector in momentum space; R (Å): radial distance of coordination shells.

To elucidate the evolution of the active site, in-situ XAS measurements of Ru/TiMnOx were conducted in the 0.5 M H2SO4 electrolytic environment (Supplementary Fig. 39 and 40, Supplementary Table 17). The Mn K-edge XANES spectra demonstrated a reversible behavior of unoccupied Mn orbitals: upon applying a positive voltage bias ( + V), the white-line intensity exhibited an initial increase followed by complete recovery to its original state upon voltage reversal (-V), indicative of dynamic reconstruction of Mn 3 d electronic states (Supplementary Fig. 39a). Furthermore, the Mn-O bond length displayed reversible structural modulation: starting from the initial value of ~1.89 Å, it underwent elongation to ~1.90 Å under +V bias and subsequent contraction to ~1.85 Å upon -V restoration (Supplementary Fig. 39c and Supplementary Table 17). This reversible bond length variation, combined with its orbital state recovery, provided evidence for the self-healing ability of the Mn-O bond.

We hypothesized that this reversibility guarantees the stability of Ru/TiMnOx. To investigate the self-healing behavior in the OER process, we firstly monitored changes in electrolyte concentration during electrolysis at 10 mA cm−2 in 0.5 M H2SO4. Nearly no Ti was detected in the time-dependent ICP-OES tests (Supplementary Fig. 41). By contrast, Ru and Mn concentrations initially increased for 600 min then stabilized at ~20 and ~25 ppb, respectively, correlating with potential fluctuations period. The fluctuation period of the potential driving OER during the stability test is ~20 h (with the voltage increasing during the first ~10 h and then decreasing over the subsequent ~10 h, see Supplementary Fig. 24 for details). To elucidate the structural self-healing mechanism of Ru/TiMnOx, we comprehensively characterized samples collected at 10.83 h (denoted as Ru/TiMnOx-OER-10) and 20.63 h (denoted as Ru/TiMnOx-OER-20) using XAS (Fig. 4d–f, Supplementary Figs. 42 and 43). XANES analysis revealed a reversible oxidation state modulation of Ru: starting from +3.0 in the fresh catalyst, the valence state increased to +3.7 after ~10 h of electrolysis, then decreased to +2.7 by ~20 h (Supplementary Fig. 42). This dynamic redox cycling suggested inherent self-healing capability of Ru centers, effectively maintaining the high catalytic activity. It is noteworthy that the strong interaction between the bridging O atom and proton induced local crystal lattice distortion55. This structural perturbation manifested as an initial elongation of the Ru-O-M bond length (from 3.31 Å to 3.34 Å), accompanied by a simultaneous reduction in coordination number (CN) from 3.9 to 2.6 within the first ~10 h, followed by complete recovery to the original geometric parameters after ~20-h electrolysis (Fig. 4e and Supplementary Table 14). The temporary decrease in CN reflects partial lattice distortion56, while the subsequent recovery indicates structural self-healing through dynamic bond reconfiguration. Such dynamic behavior demonstrated the reconstruction of long-range coordination order, thereby re-establishing its catalytic activity for OER in the subsequent period. By combining time-dependent ICP and XAS characterizations, the self-healing mechanism of Ru/TiMnOx was proposed to involve the following processes: Ti stabilizes the crystalline framework, trace amounts of Ru/Mn dissolve and redeposit, accompanied by the restoration of both compositional and coordination structures (Fig. 5a). This self-healing processes not only explain the observed potential oscillations but also fundamentally guarantee Ru/TiMnOx’s long-term stability in OER applications.

a Schematic illustration for the self-healing behavior of integrated Ru/TiMnOx electrode. b In-situ Raman spectra of integrated Ru/TiMnOx electrode in 0.5 M H2SO4 electrolyte under different external applied potential (OCP−1.75 V vs. RHE). c 2D in-situ Raman contour image enlarged from (b). d, e In-situ ATR-FTIR spectra recorded in the potential range of OCP−1.85 V vs. RHE for Ru/TiMnOx in 0.5 M H2SO4 electrolyte. f, g In-situ differential electrochemical mass spectrometry (DEMS) signals of O2 products for Ru/TiMnOx in 0.5 M H2SO4 (H218O) (f) and 0.5 M H2SO4 (H216O) (g).

Then, the structural evolution of catalyst was tracked by in-situ electrochemical Raman spectroscopy (Fig. 5b, c and Supplementary Fig. 44). As the potential increased from open circuit potential (OCP) to 1.75 V vs. RHE, a blue-shift was observed in the Mn-O vibrational peaks (Fig. 5b). According to Hooke’s law57,58, this blue-shift are attributed to the substitution of Mn by Ru during the OER. Notably, the A1g mode at ca. 666 cm-1 gradually vanished as the potential increased, indicating the deprotonation of Ru-O-Mn59,60. When the potential cycled back to OCP, this peak intensity returned to initial level (Fig. 5c). The combined time-dependent ICP-OES and in-situ spectroscopy results coincide with the hypothesis that the Ru/TiMnOx can self-repair during the OER process, thereby ensuring long-term catalytic efficiency.

Influence of intrinsic metal-support interactions on the OER mechanism

To experimentally investigate the OER mechanism, in-situ attenuated total reflectance Fourier transform infrared (ATR-FTIR) spectroscopy was conducted on Ru/TiMnOx, allowing for tracking the changes in surface reaction intermediates (Fig. 5d, e, Supplementary Figs. 45 and 46). In addition to an absorption peak at ca. 3,619 cm-1 (Fig. 5e, O-H stretching mode), distinctive absorption peaks at 1117 cm-1 and 1100 cm-1 were also observed (Fig. 5d and Supplementary Fig. 46). The central peak (1089 cm-1) and shoulder peak (1100 cm-1) signify the formation of O-O bonds15,61. Specifically, the linearly bonded superoxol species (*-O-O) and the oxygen bridges between metal sites (*-O-O-*), respectively15,62,63. This feature agrees with the advanced oxide path mechanism (OPM) pathway which break through the theoretical activity limit in the traditional adsorbate evolution mechanism (AEM) and avoid the structure collapse in the lattice oxygen oxidation mechanism (LOM)7,15,34,35,61. Additionally, these peak intensities returned to their initial levels when the potential decreased to OCP, reinforcing the reversibility of Ru/TiMnOx. To experimentally confirm this OPM pathway, in-situ differential electrochemical mass spectrometry (DEMS) with isotopic labeling measurements was conducted (Fig. 5f, g, Supplementary Figs. 47 and 48). Initially, the Ru/TiMnOx were subjected to three LSV cycles in 0.5 M H2SO4 (H218O) (Supplementary Fig. 48a). For the OPM-type OER, the adsorbed 16O species on neighboring metal sites may couple to form 32O2, which were detected during the initial 18O-labeling process for Ru/TiMnOx (Fig. 5f). Next, the electrocatalyst was thoroughly washed with H216O deionized water and then operated in the 0.5 M H2SO4 (H216O) electrolyte (Supplementary Fig. 48b). The captured 36O2 signals (Fig. 5g), resulting from the coupling of adjacent 18O adsorbates, corroborate the OPM-related pathway in Ru/TiMnOx15.

The density functional theory (DFT) calculations were conducted to gain insight into the origin of the enhanced OER performance for Ru/TiMnOx. According to the XRD refinement and TEM analysis, Ru/TiMnOx (100) and Ru/MnOx (110) slab models were constructed with formulas of Ru0.24/Ti0.28Mn0.48O and Ru0.56/Mn0.44O2, respectively (Fig. 6a, Supplementary Figs. 49 and 50, Supplementary Data 1). Based on the Bader charge analysis, the average charge of Ru in Ru/TiMnOx was found to be +0.55 e, which is lower than that of RuO2 (+1.68 e). The charge density difference of Ru/TiMnOx and Ru/MnOx further indicated a shift of electron cloud from O to M in the M-O covalent bond (Fig. 6b and Supplementary Figs. 51–53). This observation indicates that the electron transfer from Mn/Ti to Ru through the bridging O atom (Obri) results from the intrinsic metal-support interactions. To quantify the covalency of the M-O bond, the partial density of states (PDOS) calculations were employed (Fig. 6d and Supplementary Fig. 54). The energy of the Ru d-band center (ɛd) for Ru/TiMnOx (-1.167 eV) was more appropriate for adsorbate-catalyst surface interaction compared to Ru/MnOx (-1.936 eV) and RuO2 (-1.110 eV)43. Furthermore, the gap between the Ru/Mn ɛd and O 2p band center (ɛp) is greatly enlarged in Ru/TiMnOx, with values of 2.31 eV and 0.98 eV for Ru-O and Mn-O, respectively. Consequently, the covalency of M-O bonds in Ru/TiMnOx is lower than in Ru/MnOx and RuO2. It is well-established that weaker M-O covalency boosts catalyst stability by inhibiting the LOM mechanism during OER, thereby accounting for the long-term stability of Ru/TiMnOx64,65,66. The enhanced stability of Ru/TiMnOx was also evidenced by its high de-metallization energies for Ru and Mn (Fig. 6c and Supplementary Table 18). Specifically, the de-metallization energy of Ru in Ru/TiMnOx is 0.174 eV greater than in RuO2 and 0.462 eV greater than in Ru/MnOx. Next, we conducted mechanistic studies targeting the OER process. The preferred reaction pathways were determined by investigating the OER paths based on OPM and AEM (Fig. 6e and Supplementary Figs. 55–58). For Ru/MnOx, the formation of *OOH was identified as the rate-determining step (RDS), characterized by a significant free energy barrier of 1.957 eV. Comparatively, the RDS for Ru/TiMnOx via the OPM pathway is 1.511 eV, 0.952 eV lower than that of the AEM, indicating a thermodynamic preference for the OPM. Therefore, theoretical calculations reveal that Ru-Obri-Ti/Mn bonds in Ru/TiMnOx modulate charge distribution and orbital overlap, optimizing the OER pathway.

a Ru0.24/Ti0.28Mn0.48O structure with the value of computed bader charge and bond length. b Filled contour plot of the cross-section of differential charge density for Ru0.24/Ti0.28Mn0.48O (100). c Demetallization energies of Ru from RuO2; Ru and Mn from Ru/MnOx and Ru/TiMnOx, respectively. d Schematic diagram of the band structures of Ru/TiMnOx, Ru/MnOx and RuO2 based on PDOS analysis. e The free energy diagrams for preferred OER paths on the surfaces of Ru/MnOx and Ru/TiMnOx. RDS denotes rate-determining step.

Discussion

In summary, the concept of intrinsic metal-support interactions has been established and validated, addressing a critical challenge in breaking the activity-stability tradeoff for electrolysis. The Ru/TiMnOx exhibited low overpotential of 165.2 mV at 10 mA cm−2, aligning well with machine learning predictions and thereby avoiding traditional trial-and-error approaches. Its mass activities exceed benchmark Ru oxides by ~49, 113, and 75 times under acidic, neutral, and alkaline conditions, respectively; while maintaining 3000-h stability at pH=0. Our findings offer a potential pathway to modulate intrinsic metal-support interactions, thereby mitigating the activity-stability tradeoff in electrocatalysis.

Methods

Synthesis of Ru/TiMnOx samples

The integrated Ru/TiMnOx electrode was prepared through a chemical steam deposition (CSD) strategy which combines the concept of chemical vapor deposition (CVD) and the conditions of hydrothermal reaction (see Fig. 1a, Supplementary Figs. 1 and 2, and Supplementary Discussion 1 for details). In detail, the entire CSD process can be completed in one step, and its mechanism were dissected into the following three steps: firstly, potassium permanganate (KMnO4, Aladdin 99.99%, AR, grade) in aqueous solution oxidized ruthenium(III) chloride hydrate (RuCl3·xH2O, Alfa Aesar, 99.99%, AR, grade) to RuO4 gas. Secondly, under hydrothermal conditions, RuO4 gas, along with KMnO4 steam, underwent spontaneous redox reactions with the Ti foam (TF, thickness 600 μm, Tianjin Eilian Electronics & technology Co. ltd). Finally, the resulting Ru/TiMnOx deposited in-situ on the Ti substrate. Before synthesis, a Ti foam piece (1.0 × 6.0 cm) was etched in hydrochloric acid (HCl, 18 wt%, Sinopharm Chemical Reagent Co., Ltd.) at 90 °C for 15 min. Synthesis of Ru0.24/Ti0.28Mn0.48O involved the following steps: (1) Preparation of a redox-active precursor by dissolving 27.0 mg RuCl3•xH2O and 79.0 mmol KMnO4 in 10.0 mL deionized water; (2) Immersion of a pre-etched TF substrate into the solution within a Teflon-lined autoclave; (3) Hydrothermal reaction at 140 °C (3 h) to concurrently generate the Ti-Mn-O matrix and immobilize Ru species, uniquely yielding gas-phase reaction products from the critical interaction between KMnO4 and RuO4 during hydrothermal nucleation; (4) Post-synthesis washing (deionized water) and vacuum drying (60 °C) of the TF-supported Ru0.24/Ti0.28Mn0.48O. The material obtained from the reaction occurring above the liquid level was identified as Ru0.24/Ti0.28Mn0.48O, and its physical representation corresponds to the black portion on the Ti substrate (Supplementary Fig. 2a). To validate the CSD synthesis mechanism, we devised an apparatus that ensures the exclusive production of gas-phase products during the hydrothermal process (Supplementary Fig. 2). Specifically, the Ti substrates were placed on hollow supports with different heights (4.5, 5 and 5.5 cm) to ensure sufficient gas reaction. Furthermore, we successfully scaled up the support size in proportion to the dimensions of the hydrothermal reactor, thereby obtaining integrated Ru/TiMnOx electrodes with surface areas of 4.00, 6.25, and 12.25 cm², demonstrating the scalability of the CSD. The Ru mass loading of Ru/TiMnOx was 0.14 mg cm−2.

Synthesis of control samples

For comparison, Ru/MnOx, TiMnOx and commercial RuO2 (denoted as Com. RuO2) samples were synthesized. The synthesis conditions for TiMnOx were identical to those employed for Ru/TiMnOx, with the sole exception being that TiMnOx was derived via a liquid-phase reaction occurring within the liquid medium during the hydrothermal process. TiMnOx corresponds to the gray portion on the Ti substrate depicted in Supplementary Fig. 2a. The Ru/MnOx powder was prepared using the same hydrothermal method as Ru/TiMnOx, without adding a Ti substrate. The RuO2 catalyst on TF was fabricated by the following steps: a dispersion was prepared by mixing 50 μL of ethanol, 5 μL of nafion, 15 μL of deionized water, and 10 mg of RuO2 (Alfa Aesar). Subsequently, the dispersion was dropwise added and dispersed onto the TF, with the added quantity determined according to the loading mass of Ru. The Ru mass loadings of Ru/MnOx and Com. RuO2 were 0.35 mg cm−2 and 0.52 mg cm−2, respectively.

The machine learning method

To find the optimal ratio combination of Ru, Mn, and Ti, a powerful and widely used machine learning model, the back-propagation neural network, was employed. In this experiment, five-fold cross-validation was used to optimize the number of layers and the initial learning rate. Three-layer, five-layer, and seven-layer back-propagation networks were considered (excluding the input layer). The activation function of the last layer is linear and all the other layers are rectified linear unit. The number of neurons for the three-layer neural network was (128, 32, 2), for the five-layer network was (128, 64, 32, 16, 2), and for the seven-layer network was (128, 64, 64, 32, 32, 16, 2). The initial learning rates considered were 1e-2, 1e-3, 1e-4, and 1e-5. The loss function was the weighted mean squared error of η and the degradation rate (ΔE), with the weight of η set to be twice that of the ΔE in order to emphasize the importance of η. The Adaptive Moment Estimation optimizer, also known as Adam, was used with 1000 epochs. Finally, based on the cross-validation results, a five-layer back-propagation network with an initial learning rate of 1e-4 was selected. To minimize the impact of randomness, ten training runs were performed, and the one with the smallest mean squared error was chosen as the final model. The data sources, training process and the detailed parameters are shown in Supplementary Figs. 3 and 4, Supplementary Tables 1 and 2, and Supplementary Code 1.

Ex-situ characterizations

Multiscale structural and chemical profiling of the samples included: (1) Topographical and elemental distribution analysis via field-emission scanning electron microscopy (FE-SEM, JSM-7500) integrated with energy-dispersive X-ray spectroscopy (EDS); (2) Atomic-resolution lattice imaging by aberration-corrected transmission electron microscopy (FE-TEM, Titan Themis G2F20) in high-angle annular dark-field scanning TEM mode (HAADF-STEM); (3) Nanoscale compositional mapping using scanning transmission electron microscopy (STEM, Tecnai G2F30) at 300 kV accelerating voltage; (4) Crystalline phase identification through powder X-ray diffraction (XRD, Rigaku SmartLab) with Cu Kα radiation (λ = 1.5418 Å), scanning at 2°/min; (5) Surface speciation and oxidation states quantified by X-ray photoelectron spectroscopy (XPS, ESCALAB 250Xi) with monochromatic Al Kα source (1486.6 eV), calibrated against adventitious carbon (C 1 s, 284.8 eV). Depth profiling was further conducted via alternating cycles of argon ion sputtering (Ar+) and XPS spectral acquisition, enabling layer-by-layer characterization of composition gradients from the surface to the substrate interface. The focused ion beam (FIB) was used for Ru/TiMnOx cross-sectional imaging using FEI Helios G4. The metal concentration in electrolytes were characterized by the inductively coupled plasma optical emission spectrometry (ICP-OES) measurement (iCAP 7400, Thermo, Waltham, USA). Since Ru/TiMnOx was grown in situ on a Ti substrate, the dissolution of the solid did not allow for the measurement of the Ti content in the Ru/TiMnOx. To ascertain the relative elemental proportions within the Ru/TiMnOx material, we implemented an ultrasonic dispersion technique to disperse the Ru/TiMnOx in an aqueous medium, subsequently quantifying the elemental composition of the resultant solution through ICP-OES. This approach circumvented interference from the Ti substrate, enabling accurate measurement of Ru and Mn concentrations. Synchrotron-based X-ray absorption spectroscopy studies were conducted at the Shanghai Synchrotron Radiation Facility (SSRF, beamline BL14W1). Ru K-edge and Mn K-edge spectra were collected using a 4-channel silicon drift detector (Bruker 5040). Samples were prepared as 1 cm diameter pellets sealed with Kapton tape. Reference standards (Ru foil, RuO2, Mn foil, Mn2O3, MnO2) were measured in transmission mode for valence state calibration. Data processing, including background subtraction, normalization, and EXAFS fitting, was executed using the IFEFFIT package (Athena and Artemis modules)67,68. Fourier transforms of χ(k) data employed a Hanning window (dk = 1.0 Å-1), with structural parameters refined via least-squares fitting for conversion into radial distance space (R-space). By taking the first derivative (dμ/dE) of the normalized-XAS of Ru and Mn K-edge, the E0 value was obtained corresponding to the first maximum point. Subsequently, the linear relationship between E0 and valence state is established using references with known valence states (Ru foil and RuO2 for Ru; Mn foil, Mn2O3 and MnO2 for Mn). Finally, the valence state of the target elements in unknown samples were determined by comparing their measured E0 values to the relationship.

In-situ characterizations

In-situ XAS for Mn K-edge was performed at the Canadian Light Source. Before the in-situ XAS test, a micro-electrochemical cell was fabricated with Ru/TiMnOx as the anode ( ~ 1.0 cm2), 0.5 M H2SO4 as electrolyte. The micro-electrochemical cell was connected to an electrochemical station (Biologic). The working electrode was firstly tested without H2SO4 electrolyte and applied voltage, named as ex-situ. Then, the voltages (1.45 V vs. RHE and -0.13 V vs. RHE) were applied, corresponding to current densities of 15 mA cm−2 and -15 mA cm−2, respectively. The catalyst was stabilized for 15 min prior to XAS measurements at each potential. The in-situ XAS spectra of Mn were recorded in transmission mode for 120 seconds, and then the X-ray beam was blocked for 20 min to minimize potential beam damage. During the test, all obtained spectra were calibrated using Mn foil as a reference. The spectra were analyzed using Athena software. In-situ Raman spectroscopy was performed using a Renishaw inVia Raman microscope and a CHI650E electrochemical workstation. The working electrode of Ru/TiMnOx was immersed in the 0.5 M H2SO4 electrolyte through the wall of the in-situ cell, with its plane perpendicular to the laser. Pt and Ag/AgCl were used as the counter electrode and reference electrode, respectively. The potential was gradually increased from OCP to 1.75 V vs. RHE and then gradually decreased back to the initial value, with a stabilization period of 300 seconds at each potential level. For the electrochemical in-situ attenuated total reflectance Fourier transform infrared (ATR-FTIR) measurements, a silicon crystal coated with an Au film was used in the internal reflection mode. The spectra were recorded on a Thermo Nicolet Nexus 670 spectrometer, with a CHI650E electrochemical workstation employed. Pt and Ag/AgCl were used as the counter electrode and reference electrode, respectively. Before data collection, a voltage was applied to the working electrode for 20 min to test for receiving a reliable signal. Then, the potential was gradually increased from OCP to 1.85 V vs. RHE and then gradually decreased back to the initial value. The in-situ differential electrochemical mass spectrometry (DEMS) system is similar to the system recently reported by the Lee group15. The in-situ DEMS system consisted of two interconnected vacuum chambers, including a mass spectrometer chamber with a high vacuum and a second chamber with a mild vacuum. The working electrode was an Au film sputtered on a porous polytetrafluoroethylene membrane. After obtaining powder catalysts through ultrasonic treatment of integrated Ru/TiMnOx electrode, the catalyst ink was prepared and dropped onto the Au film. The electrochemical cell was a three-electrode system with volume of ~3 mL. Before the electrochemical measurements, all the electrolytes were purged with high-purity Ar to remove the dissolved oxygen. Before data collection, a voltage was applied to the working electrode for 718 s to test for receiving a reliable signal. The Ru/TiMnOx were subjected to three LSV cycles in the potential range of 1.17-1.72 V vs. RHE at a scan rate of 10 mV s-1 in 0.5 M H2SO4 (H218O), while the mass signals of 32O2, 34O2 and 36O2 were recorded. Then, five consecutive CV cycles (1.17-1.72 V vs. RHE) were applied for labeling the catalyst surface with 18O. The catalysts were thoroughly washed with H216O deionized water to remove surface-adsorbed H218O and then operated in the 0.5 M H2SO4 (H216O) electrolyte. Before data collection, a voltage was applied to the working electrode for 767 s to test for receiving reliable signals. Again, the gaseous products were monitored by the mass spectrometer.

Electrochemical measurements

All electrochemical experiments were conducted using a BioLogic VSP-300 potentiostat equipped with iR compensation module. A conventional three-electrode cell was employed, comprising: working electrode (as-synthesized integrated RuTiMnOx electrode: geometric area: 1 cm2; thickness: 600 μm), counter electrode (Pt plate: 1 cm2 effective area; positioned parallel to the working electrode) and reference electrode (Ag/AgCl in saturated KCl). The Ag/AgCl reference electrode was calibrated against a secondary pre-validated master electrode (Tianjin Eilian Electronics & technology Co. ltd) using a dual-reference-electrode setup. Both electrodes were immersed in saturated KCl solution, and the open-circuit potential (OCP) was recorded, ensuring potential stability within ± 5 mV. The electrolytes were freshly prepared and promptly utilized. Linear sweep voltammetry (LSV) was performed at a scan rate of 10 mV s-1 from 0.0 to 2.0 V vs. RHE. The potential was converted to the reversible hydrogen electrode (RHE) scale using the Eq. (1):

The LSV curves were corrected with 95 % iR (i, current; R, resistance) compensation. The chronopotentiometric tests, conducted under iR-free conditions at a constant current density of 10 mA cm−2, were performed in an H-type water electrolysis cell with the anode and cathode separated by a Nafion 117 membrane. A Nafion 117 membrane (DuPont, thickness: 183 μm) was sequentially washed by 5 wt% H2O2, electrolyte, and deionized water for 30 min, 60 min, and 30 min, respectively. The active area of Nafion 117 membrane is 19.6 cm−2. Nyquist plots derived from electrochemical impedance spectroscopy (EIS) were acquired using a BioLogic VSP-300 potentiostat under open-circuit conditions, with a sinusoidal perturbation amplitude of 5 mV applied across the frequency domain from 100 kHz to 0.01 Hz. Measurements were conducted in 0.5 M H2SO4 (pH = 0.3 ± 0.02), 0.5 M PBS (pH = 7.1 ± 0.10) and 1.0 M KOH (pH = 13.9 ± 0.03) electrolytes.

For PEMWE tests, a cation exchange membrane (DuPont, Nafion 117) was used as the membrane electrolyte. The membrane electrode assembly (MEA) was prepared by pressing the cathodes (20% Pt/C sprayed on the Nafion 117 membrane) and anodes (Ru/TiMnOx). During the test, the cell was maintained at 60 °C, and the pre-heated deionized water was fed to the anode by a peristaltic pump. For AEMWE tests, the anion exchange membrane (FAA-3–50) was pre-treated in 1.0 M KOH for over 24 h and cleaned with deionized water. The commercial Raney Ni mesh was used as the cathode while the Ru/TiMnOx was used as the anode. 1.0 M KOH was used as an electrolyte at a temperature of 60 °C. All the data of PEMWE and AEMWE were not iR corrected and displayed as raw data.

Calculation of intrinsic activities

The electrochemically accessible surface area (ECSA) was quantified using the double-layer capacitance method, as defined by (2):

Where Cdl is electrode-specific double-layer capacitance and Cs is the specific capacitance of the sample. Cdl was derived from cyclic voltammetry (CV) scans in the non-faradaic region (0.2 ~ 0.3 V vs. RHE) with six scan rates (20, 40, 60, 80, 100, 120 mV s-1). The charging current (ic) was measured at 0.25 V vs. RHE and plotted against scan rate (v). The slope of the linear regression yielded Cdl according to Eq. (3):

The mass activity (jmass) was determined using Eq. (4):

Where mRu is the calculated Ru mass loading based on the results of ICP-OES analysis, Ageo is the geometric area and jgeo is the geometric current density.

Computational details

All DFT calculations were conducted by Vienna Ab initio Simulation Package (VASP) with projected augmented wave (PAW) pseudopotentials. The generalized gradient approximation (GGA) functional of Perdew-Burke-Ernzerhof (PBE) was applied as the exchange-correlation functional. The kinetic cutoff energy of plane wave was set at 520 eV. The DFT + U approach was applied with Ueff = 3.9 for Mn to treat the strong on-site Coulomb interaction of localized electrons.The supercell of Ru/MnTiOx, Ru/MnOx and RuO2 contained 64, 96, 48 atoms respectively. The Brillouin zone in reciprocal space was sampled by a gamma-centered k-point grid of 2 × 2 × 2 during structural optimization. The slab model of Ru/MnTiOx had four layers, containing 18 Ru atoms, 34 Mn atoms, 20 Ti atoms and 72 O atoms. The Ru/MnOx (110) slab model had 96 atoms, including 18 Ru atoms, 14 Mn atoms and 64 O atoms. The slab models are used for calculations of OER and demetallization energies. The demetallization energies were obtained by the following Eq. (5):

where Etot is the total energy of the slab model, Eatom is the energy of a single atom and Evac is the slab model energy with a vacancy formed by removing the single atom.

The computational hydrogen electrode (CHE) approach was applied to calculate the energy barrier in OER process. Adsorbate evolution mechanism (AEM) and oxide path mechanism (OPM) were both considered. The overpotential in AEM was evaluated using the following steps (6)–(9):

OPM was shown in the following steps (10)–(14):

*OH, *O, and *OOH are the reaction intermediates adsorbed on the catalyst surface. The catalyst surface was represented by slab models in calculation. Then, the free energy of each OER step was calculated according to the following Eq. (15):

where ΔZPE is the zero-point energy, ΔE is the change in the total ground-state energy, T is temperature (298 K), ΔS is the change in entropy and ΔGU = eU, U is the electrode potential. The zero point energies and entropies of the intermediates were obtained by calculating the vibrational frequencies.

Data availability

All data supporting this study is available in the article and the Supplementary Information. Source Data file has been deposited in Figshare under accession code DOI link69.

Code availability

The Python code written in this paper for screening the most appropriate catalyst metal ratio is provided in the Supplementary Code 1.

References

Seh, Z. W. et al. Combining theory and experiment in electrocatalysis: insights into materials design. Science 355, eaad4998 (2017).

Ram, R. et al. Water-hydroxide trapping in cobalt tungstate for proton exchange membrane water electrolysis. Science 384, 1373–1380 (2024).

Chong, L. et al. La-and Mn-doped cobalt spinel oxygen evolution catalyst for proton exchange membrane electrolysis. Science 380, 609–616 (2023).

Li, A. et al. Atomically dispersed hexavalent iridium oxide from MnO2 reduction for oxygen evolution catalysis. Science 384, 666–670 (2024).

Yang, S. et al. The mechanism of water oxidation using transition metal-based heterogeneous electrocatalysts. Chem. Soc. Rev. 53, 5593–5625 (2024).

Lyu, Z. et al. Biphase Pd Nanosheets with atomic-hybrid RhOx/Pd amorphous skins disentangle the activity-stability trade-off in oxygen reduction reaction. Adv. Mater. 36, 2314252 (2024).

Rong, C., Dastafkan, K., Wang, Y. & Zhao, C. Breaking the activity and stability bottlenecks of electrocatalysts for oxygen evolution reactions in acids. Adv. Mater. 35, 2211884 (2023).

Wang, Q. et al. Long-term stability challenges and opportunities in acidic oxygen evolution electrocatalysis. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 135, e202216645 (2023).

Zhang, Y. L. et al. Engineering Co-N-Cr cross-interfacial electron bridges to break activity-stability trade-off for superdurable bifunctional single atom oxygen electrocatalysts. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 63, e202400577 (2024).

Han, N. et al. Lowering the kinetic barrier via enhancing electrophilicity of surface oxygen to boost acidic oxygen evolution reaction. Matter 7, 1330–1343 (2024).

Li, W. et al. Defect engineering for fuel-cell electrocatalysts. Adv. Mater. 32, 1907879 (2020).

Yang, Y. et al. Anion-exchange membrane water electrolyzers and fuel cells. Chem. Soc. Rev. 51, 9620–9693 (2022).

Sun, W. et al. A rechargeable zinc-air battery based on zinc peroxide chemistry. Science 371, 46–51 (2021).

Kondori, A. et al. A room temperature rechargeable Li2O-based lithium-air battery enabled by a solid electrolyte. Science 379, 499–505 (2023).

Lin, C. et al. In-situ reconstructed Ru atom array on α-MnO2 with enhanced performance for acidic water oxidation. Nat. Catal. 4, 1012–1023 (2021).

Wu, Z.-Y. et al. Non-iridium-based electrocatalyst for durable acidic oxygen evolution reaction in proton exchange membrane water electrolysis. Nat. Mater. 22, 100–108 (2023).

Gloag, L., Somerville, S. V., Gooding, J. J. & Tilley, R. D. Co-catalytic metal-support interactions in single-atom electrocatalysts. Nat. Rev. Mater. 9, 173–189 (2024).

Yang, J., Li, W., Wang, D. & Li, Y. Electronic metal-support interaction of single-atom catalysts and applications in electrocatalysis. Adv. Mater. 32, 2003300 (2020).

Li, Y., Zhang, Y., Qian, K. & Huang, W. Metal-support interactions in metal/oxide catalysts and oxide–metal interactions in oxide/metal inverse catalysts. ACS Catal. 12, 1268–1287 (2022).

Hu, S. & Li, W.-X. Sabatier principle of metal-support interaction for design of ultrastable metal nanocatalysts. Science 374, 1360–1365 (2021).

Shan, J. et al. Metal-metal interactions in correlated single-atom catalysts. Sci. Adv. 8, eabo0762 (2022).

Yang, C. et al. Metal alloys-structured electrocatalysts: metal-metal interactions, coordination microenvironments, and structural property-reactivity relationships. Adv. Mater. 35, 2301836 (2023).

Wang, Y. et al. Advanced electrocatalysts with single-metal-atom active sites. Chem. Rev. 120, 12217–12314 (2020).

Chen, S. et al. Defective TiOx overlayers catalyze propane dehydrogenation promoted by base metals. Science 385, 295–300 (2024).

Beck, A. et al. Controlling the strong metal-support interaction overlayer structure in Pt/TiO2 catalysts prevents particle evaporation. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 62, e202301468 (2023).

Chen, H. et al. Photoinduced strong metal-support interaction for enhanced catalysis. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 143, 8521–8526 (2021).

Xin, H. et al. Overturning CO2 hydrogenation selectivity with high activity via reaction-induced strong metal-support interactions. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 144, 4874–4882 (2022).

Peng, B. et al. Embedded oxide clusters stabilize sub-2 nm Pt nanoparticles for highly durable fuel cells. Nat. Catal. 7, 818–828 (2024).

Zhai, P. et al. Engineering single-atomic ruthenium catalytic sites on defective nickel-iron layered double hydroxide for overall water splitting. Nat. Commun. 12, 4587 (2021).

Hejazi, S. et al. On the controlled loading of single platinum atoms as a Co-catalyst on TiO2 anatase for optimized photocatalytic H2 generation. Adv. Mater. 32, 1908505 (2020).

J. Chang et al. Synthesis of ultrahigh-metal-density single-atom catalysts via metal sulfide-mediated atomic trapping. Nat. Synth. https://doi.org/10.1038/s44160-024-00607-4 (2024).

Zhao, S. et al. Constructing regulable supports via non-stoichiometric engineering to stabilize ruthenium nanoparticles for enhanced pH-universal water splitting. Nat. Commun. 15, 2728 (2024).

Rong, C. et al. Electronic structure engineering of single-atom Ru sites via Co-N4 sites for bifunctional pH-universal water splitting. Adv. Mater. 34, 2110103 (2022).

Liu, W. et al. Extremely active and robust Ir-Mn dual-atom electrocatalyst for oxygen evolution reaction by oxygen-oxygen radical coupling mechanism. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 136, e202411014 (2024).

Chang, J. et al. Oxygen radical coupling on short-range ordered Ru atom arrays enables exceptional activity and stability for acidic water oxidation. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 146, 12958–12968 (2024).

Zhou, Y. et al. Lattice-confined Ru clusters with high CO tolerance and activity for the hydrogen oxidation reaction. Nat. Catal. 3, 454–462 (2020).

Han, H.-J. et al. Chemical vapor deposition of Ru thin films with an enhanced morphology, thermal stability, and electrical properties using a RuO4 precursor. Chem. Mater. 21, 207–209 (2009).

Sabzi, M. et al. A review on sustainable manufacturing of ceramic-based thin films by chemical vapor deposition (CVD): reactions kinetics and the deposition mechanisms. Coatings 13, 188 (2023).

Zaera, F. Mechanisms of surface reactions in thin solid film chemical deposition processes. Coord. Chem. Rev. 257, 3177–3191 (2013).

Din, R.-U. et al. Steam assisted oxide growth on aluminium alloys using oxidative chemistries: Part I Microstructural investigation. Appl. Surf. Sci. 355, 820–831 (2015).

Din, R.-U., Gudla, V.-C., Jellesen, M.-S. & Ambat, R. Accelerated growth of oxide film on aluminium alloys under steam: part I: effects of alloy chemistry and steam vapour pressure on microstructure. Surf. Coat. Tech. 276, 77–88 (2015).

Hu, W. et al. Doping Ti into RuO2 to accelerate bridged-oxygen-assisted deprotonation for acidic oxygen evolution reaction. Adv. Mater. 37, 2411709 (2025).

Zhong, X. et al. Stabilization of layered lithium-rich manganese oxide for anion exchange membrane fuel cells and water electrolysers. Nat. Catal. 7, 546–559 (2024).

Zhang, L. et al. Sodium-decorated amorphous/crystalline RuO2 with rich oxygen vacancies: a robust pH-universal oxygen evolution electrocatalyst. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 133, 18969–18977 (2021).

Yin, H. et al. Dual active centers bridged by oxygen vacancies of ruthenium single-atom hybrids supported on molybdenum oxide for photocatalytic ammonia synthesis. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 61, e202114242 (2022).

You, M. et al. In-situ growth of ruthenium-based nanostructure on carbon cloth for superior electrocatalytic activity towards HER and OER. Appl. Catal. B 317, 121729 (2022).

Thalluri, S.-M. et al. Enhancing alkaline hydrogen evolution reaction on Ru-decorated TiO2 nanotube layers: synergistic role of Ti3+, Ru single atoms, and Ru nanoparticles. Energy Environ. Sci. 8, e12864 (2025).

Powar, N.-S. et al. Unravelling the effect of Ti3+/Ti4+ active sites dynamic on reaction pathways in direct gas-solid-phase CO2 photoreduction. Appl. Catal. B 352, 124006 (2024).

Wang, K. et al. Highly active ruthenium sites stabilized by modulating electron-feeding for sustainable acidic oxygen-evolution electrocatalysis. Energy Environ. Sci. 15, 2356–2365 (2022).

Deng, L. et al. Valence oscillation of Ru active sites for efficient and robust acidic water oxidation. Adv. Mater. 35, 2305939 (2023).

Qin, Q. et al. Atomically dispersed vanadium-induced Ru-V dual active sites enable exceptional performance for acidic water oxidation. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 137, e202413657 (2025).

Deka, N. et al. On the operando structure of ruthenium oxides during the oxygen evolution reaction in acidic media. ACS Catal. 13, 7488–7498 (2023).

Li, Y. et al. Integrating interactive Ir atoms into titanium oxide lattice for proton exchange membrane electrolysis. Adv. Mater. 37, 2407386 (2025).

Chen, Y. et al. Metastabilizing the ruthenium clusters by interfacial oxygen vacancies for boosted water splitting electrocatalysis. Adv. Energy Mater. 14, 2400059 (2024).

Pan, X. et al. Electric-field-assisted proton coupling enhanced oxygen evolution reaction. Nat. Commun. 15, 3354 (2024).

Feng, W. et al. Proton exchange membrane water splitting: advances in electrode structure and mass-charge transport optimization. Adv. Mater. 37, 2416012 (2025).

Duan, X. et al. Simultaneously constructing active sites and regulating Mn-O strength of Ru-substituted perovskite for efficient oxidation and hydrolysis oxidation of chlorobenzene. Adv. Sci. 10, 2205054 (2023).

Yu, Z. et al. Defective Ru-doped α-MnO2 nanorods enabling efficient hydrazine oxidation for energy-saving hydrogen production via proton exchange membranes at near-neutral pH. Chem. Eng. J. 470, 144050 (2023).

Wen, Y. et al. Introducing Brønsted acid sites to accelerate the bridging-oxygen-assisted deprotonation in acidic water oxidation. Nat. Commun. 13, 4871 (2022).

Yang, C. et al. Mn-oxygen compounds coordinated ruthenium sites with deprotonated and low oxophilic microenvironments for membrane electrolyzer-based H2-Production. Adv. Mater. 35, 2303331 (2023).

Song, H. et al. RuO2-CeO2 lattice matching strategy enables robust water oxidation electrocatalysis in acidic media via two distinct oxygen evolution mechanisms. ACS Catal. 14, 3298–3307 (2024).

Wang, B. et al. In situ structural evolution of the multi-site alloy electrocatalyst to manipulate the intermediate for enhanced water oxidation reaction. Energy Environ. Sci. 13, 2200–2208 (2020).

Vivek, J. P., Berry, N. G., Zou, J., Nichols, R. J. & Hardwick, L. J. In situ surface-enhanced infrared spectroscopy to identify oxygen reduction products in nonaqueous metal-oxygen batteries. J. Phys. Chem. C. 121, 19657–19667 (2017).

Ping, X. et al. Locking the lattice oxygen in RuO2 to stabilize highly active Ru sites in acidic water oxidation. Nat. Commun. 15, 2501 (2024).

Miao, X. et al. Quadruple perovskite ruthenate as a highly efficient catalyst for acidic water oxidation. Nat. Commun. 10, 3809 (2019).

Hwang, J. et al. Perovskites in catalysis and electrocatalysis. Science 358, 751–756 (2017).

Ravel, B. et al. Data analysis for X-ray absorption spectroscopy using IFEFFIT. J. Synchrotron Rad. 12, 537–541 (2005).

Zabinsky, S. I. et al. Multiple-scattering calculations of X-ray-absorption spectra. Phys. Rev. B 52, 2995–3009 (1995).

L. Zhou, M. Yang, Y. Liu, F. Kang & R. Lv, Intrinsic metal-support interactions break the activity-stability dilemma in electrocatalysis, Figshare, https://doi.org/10.6084/m9.figshare.27233385 (2025).

Acknowledgements

This work is supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (Grant No. 52371228 (R.L.) and 52302302 (M.Y.)), the National Key Research and Development Program of China (Grant No. 2021YFA1200800 (R.L.)), Xishan-Tsinghua Program for Deep Integration of Industry-University-Research (Grant No. 20242002205) and Tsinghua University-Toyota Joint Research Center for Hydrogen Energy and Fuel Cell Technology of Vehicles (grant to R.L.). We thank R. X. Zhou and Y. F. Li for technical support, and Q. M. Yuan and G. S. Liao for experimental assistance.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

R.L., and L.Z., conceived the original idea. R.L., supervised the project. L.Z., carried out machine learning, catalyst synthesis, materials characterization, catalytic tests and related data processing. M.Y., and Y.L., carried out DFT calculations. L.Z., M.Y., Y.L., and F.K., co-wrote the manuscript. All authors contributed to data analysis, scientific discussion and commented the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Peer review

Peer review information

Nature Communications thanks Abuzar Khan, Yan-Gu Lin who co-reviewed with Chun-Kuo Peng; and Yongwen Tan for their contribution to the peer review of this work. A peer review file is available.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Zhou, L., Yang, M., Liu, Y. et al. Intrinsic metal-support interactions break the activity-stability dilemma in electrocatalysis. Nat Commun 16, 8739 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-025-63397-z

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-025-63397-z