Abstract

Achieving low-energy and high-efficiency sieving of nitrogen rejection from methane in natural gas purification processes requires precise control of material pore size with a resolution of 0.1–0.2 Å, which is highly challenging. Here, we report a novel adsorbent (MOR-Cu), a mordenite with copper introduced in situ via high-temperature crystallization, enabling precise sieving of nitrogen and methane by the appropriate pore size and pore geometry. Refinement of the crystal structure shows that the higher crystallization temperature changes the position of the copper component, increasing pore volume and enhancing nitrogen adsorption capacity and kinetics. MOR-Cu-210 obtained by crystallization at 210 °C exhibits a record nitrogen adsorption capacity (0.74 mmol g–1) and nitrogen/methane uptake ratio (62.1) at 298 K and 1 bar, breaking the bottleneck of adsorption capacity and selectivity. Cyclic gas adsorption tests and column breakthrough experiments confirm high separation performance and stable recyclability.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Natural gas has emerged as a cleaner fossil fuel with fewer greenhouse gas emissions than coal and oil1. Methane (CH4) is the main component of natural gas, and the presence of N2 significantly reduces the calorific value and does not meet pipeline transportation standards2. As such, it is essential to explore energy-efficient and cost-effective technologies to separate N2 from CH43. Currently, N2 is removed commercially by cryogenic distillation at around 100 K. This process requires multiple phase transitions, is thermally driven and has high capital and operating costs4. Pressure swing adsorption (PSA) technology is a kind of adsorption separation technology that is based on the principle of pressure-driven. The process does not involve phase changes and has the advantages of simplicity of the process and low energy consumption for operation5,6, which centers on the use of low-cost and efficient adsorbents.

Several adsorbents have been developed for CH4/N2 adsorption separation (CH4 enrichment from N2) in recent years, such as carbon-based materials (activated carbon and carbon molecular sieves)7,8,9, zeolites10,11,12,13,14 and metal–organic frameworks (MOFs)15,16,17,18. The amount of CH4 adsorbed by these porous materials is greater than the amount of N2, mainly because polarizability of CH4 is greater than that of N2 (CH4: 25.9 × 10–25 cm3 vs N2: 17.4 × 10–25 cm3)19. Although these adsorbents have good adsorption separation performance for CH4/N2 mixtures, constructing N2-selective adsorbents to preferentially adsorb N2 will allow direct recovery of the desired CH4 products in the adsorption cycle and reduce the energy consumption of PSA technology. Researchers have found that MOFs with unsaturated metal sites (V(II)20,21 and Cr(III)22,23,24) with d3 outer electronic structure show strong affinity for N2, and this class of materials can aptly separate N2/CH4 (CH4 purification from N2) through feedback π-bonding with N2. However, limited by the high reactivity of V(II) and the kinetic inertness of Cr(III), the in situ synthesis of V(II)-MOF and Cr(III)-MOF suffers from harsh reaction conditions25 as well as poor material stability21.

The kinetic diameters of N2 (3.64 Å) and CH4 (3.80 Å) differ by 0.1–0.2 Å (Supplementary Table 1), and theoretically, the adsorbent can be controlled in terms of pore size and pore shape based on the difference in molecular size to achieve N2/CH4 sieving19. However, in practice, it is difficult to achieve pore modulation with a resolution of 0.1–0.2 Å (sub-angstrom) for adsorbents26,27. Compared with MOFs, zeolites are characterized by high thermal/hydrothermal stability and low cost, and their applications in gas separation and purification are well established28,29,30,31,32. Currently, the only zeolites that can be used for selective adsorption of N2 are eight-membered-ring (8MR) small-pore zeolites (K-CHA2, K-ZSM-2533, ETS-434,35,36, K-MER37 and PHI zeolites38) and ten-membered ring (10MR) clinoptilolite28,39,40,41. In 1991, the Ca2+-type clinoptilolite40 studied by Ackley et al. had an uptake of CH4 of about 0.07 mmol g–1 and N2 of 0.23 mmol g–1, giving a N2/CH4 uptake ratio of about 3.3. Kennedy et al39. showed good N2/CH4 equilibrium selectivity values (6.8) for the exchangeable Ag+-type clinoptilolite, but the N2 adsorption was only 0.27 mmol g–1. In 2001, Sr-ETS-4 conferred sieving properties for N2/CH4 by thermally controlled modulation of the molecular gate effect of the pores, but the N2 adsorption capacity was only 0.31 mmol g–1 at 1.33 bar and 298 K35. In 2014, K-CHA reported by Shang et al. showed preferential adsorption of N2 at 253 K2, but as the temperature was increased to ambient, the N2 adsorption decreased significantly and the adsorption reversed, showing preferential adsorption of CH4. Similarly, in 2021, Zhao et al. reported temperature-dependent changes in the adsorption separation capacity of K-ZSM-25, and the N2 uptake and N2/CH4 selectivity decreased significantly with increasing adsorption temperature to 0.15 mmol g–1 and 3.9 at room temperature, respectively33.

Compared with 8MR and 10MR zeolites, twelve-membered ring (12MR) large-pore zeolites tend to have larger pore volumes, which suggesting a possible large adsorption capacity potential. Mordenite zeolites (MOR-type) are typical large-pore high-silica zeolites with one-dimensional 12MR channels. In 2021, Zhou et al. obtained iron-containing mordenite by in situ synthesis, which exhibited the highest carbon dioxide volumetric adsorption capacity and separation efficiency to date, but very limited sieving capacity for N2 and CH4 (N2: ~0.10 mmol g–1, CH4: ~0.02 mmol g–1)42.

Herein, we report the in situ synthesis of a copper-containing MOR zeolite (MOR-Cu-n, where n denotes crystallization temperature) by high-temperature crystallization. The introduction of the copper component gives MOR-Cu-n just the right sieving channel, allowing only N2 to enter and blocking the passage of CH4. At ambient temperature, MOR-Cu-210 obtained by crystallization at 210 °C exhibits high N2 adsorption capacity and the highest N2/CH4 adsorption selectivity among all reported materials, solving the prevailing problem of difficulty in balancing adsorption capacity and selectivity. The material also exhibits excellent desorption and regeneration capabilities, and its complete regeneration can be achieved by evacuation and depressurization at room temperature. This work provides an example of pore modulation with a resolution of 0.1–0.2 Å, demonstrating the great potential of large-pore zeolites for molecular sieving with very small differences.

Results

Structure characterization

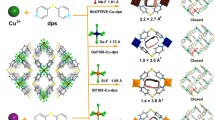

MOR-Cu-n was prepared by introducing Cu into MOR zeolite through an in situ synthesis strategy of high-temperature crystallization (Supplementary Fig. 1). Both well-preserved powder X-ray diffraction (PXRD) patterns of the samples obtained after 5 h of treatment at 923 K (Supplementary Fig. 2) and thermogravimetric analyses (Supplementary Fig. 4) demonstrated that the zeolite framework is highly thermally stable. Rietveld refinement of MOR-Cu-n was performed by collecting high-resolution PXRD as well as synchrotron X-ray diffraction (SXRD) patterns (Supplementary Fig. 6 and Supplementary Fig. 8), and the results confirmed the crystalline MOR topology of the product. MOR-Cu-n possesses one-dimensional 12MR channels (Fig. 1a and Supplementary Figs. 7, 9, and 11). The copper components located in the pores block part of the pores, acting as an obstacle and occupying part of the space originally belonging to the pores (Fig. 1b and Supplementary Fig. 12). As a result, the effective cross-section available for gas passage in MOR-Cu-210 is reduced to 3.2 Å × 5.4 Å, forming a crescent-shaped window just between the molecular sizes of N2 (3.0 Å × 3.1 Å) and CH4 (3.8 Å × 3.9 Å). MOR-Cu-150 and MOR-Cu-170 also showed similar structural features (Supplementary Fig. 12), suggesting the size/shape sieving potential of MOR-Cu-n.

The results of inductively coupled plasma–optical emission spectroscopy elemental analysis (Supplementary Table 4) showed that the Si/Al molar ratios of the in situ synthesized MOR-Cu-n were essentially the same, 5.4–5.8, which was greater than the Si/Al ratio of 4.8 for MOR-Na, it is synthesized by the conventional hydrothermal method without Cu introduction. In addition, the Cu/Al molar ratio distribution of MOR-Cu-n is in the range of 0.29–0.31, showing that we have successfully introduced the Cu component into MOR zeolite by the strategy of in situ synthesis. The Cu/Al molar ratios of the two corresponding zeolites, MOR-Cu-Ex and MOR-Cu-Im, prepared by conventional ion-exchange and wet impregnation methods, respectively, were 0.32 and 0.38, suggesting that Cu-containing MOR zeolites can be successfully synthesized by both posttreatment methods as well (Supplementary Table 4 and Supplementary Figs. 13–14). Scanning electron microscope images (Supplementary Figs. 13–16) showed that these zeolites were aggregated from prismatic crystals. A uniform distribution of Si, Al, Cu, Na and O elements in MOR-Cu-n can be observed in the high-angle annular dark field–scanning transmission electron microscopy (HAADF–STEM) images and the corresponding energy-dispersive X-ray spectral images (Fig. 2a–d and Supplementary Figs. 17–19).

HAADF–STEM image (a) of MOR-Cu-210 and the corresponding energy-dispersive X-ray mapping images for Si (b), Cu (c) and Al (d) elements. k3-weighted Fourier transform spectra (e) derived from EXAFS of Cu K-edge for MOR-Cu-n with the reference materials Cu foil and CuO. Fourier-transformed EXAFS curves for the experimental data and the fit for MOR-Cu-210 (f). UV–vis diffuse reflectance spectrum for MOR-Cu-n (g). Localized PXRD pattern for MOR-Cu-n (h). Source data for (e, f, g, h) are provided as a Source Data file.

X-ray photoelectron spectroscopy (XPS) of MOR-Cu-n showed the presence of distinct satellite peaks in the Cu 2p spectrum of Cu, confirming the divalent oxidation state of the confined Cu component (Supplementary Fig. 20). Cu K-edge X-ray absorption near-edge structure (Supplementary Fig. 21) was performed on the in situ synthesized MOR-Cu-n (n = 150, 170 and 210) showing that, compared with the standard samples, no shoulder peaks were observed at 8983 eV, suggesting that there is no presence of the Cu(I) oxidation state and elemental Cu. A small shoulder at 8986.5 eV shows that Cu(II) is the major oxidation state of copper43, which is consistent with the XPS analysis. The Fourier transform k3-weighted extended X-ray absorption fine structure (EXAFS) spectra (Fig. 2e) show a prominent peak at ~1.4 Å for MOR-Cu-n (n = 150, 170 and 210), which is mainly from the Cu–O contribution. The Cu–O spacing in MOR-Cu-210 is 1.96 Å with a coordination number of 3.6 ± 0.2 (Fig. 2f, Supplementary Fig. 22 and Supplementary Table 5), which is consistent with a tetrahedral Cu2+ species coordinated to four O atoms. Raman spectroscopy is more sensitive to the zeolite structure and allows for finer vibrational information about the T–O bonds in the zeolite framework (Supplementary Fig. 23). The results show that the additional band at 599 cm–1 for the in situ synthesized Cu-containing samples matches well with the reported symmetric telescoping vibrations of the Cu–O bond, and the active copper clusters appear to be tetra-coordinated in this conformation44. The bands at 790 and 1095 cm–1 are symmetric and asymmetric Cu–O–Si bond stretching motions45,46,47, respectively, and the increased intensity of these peaks is attributed to the effect of the crystallization temperature on the location of the copper component; the increased crystallization temperature drives more copper incorporation into the framework of the zeolite.

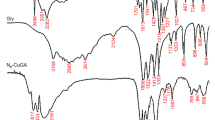

The absorption band at 1050–1063 cm–1 corresponds to the asymmetric stretching mode of the zeolite framework T–O bonds (Supplementary Fig. 24). Fourier transform infrared (FTIR) spectroscopy of the in situ synthesized Cu-containing samples showed a clear wave number change, and the increase in the crystallization temperature is accompanied by a shift of the absorption band to lower wave numbers. Because the bond length of Cu–O (1.95 Å) is larger than that of Al–O (1.75 Å), the substitution of Al by Cu leads to a decrease in the force constant and consequently to a decrease in the vibrational frequency48. We characterized the coordination environment of Cu using ultraviolet–visible (UV–vis) diffuse reflectance spectroscopy (Fig. 2g). The presence of a 250 nm peak in MOR-Cu-n, which can be generally attributed to tetra-coordinated Cu(II)49, corroborates the results from EXAFS and Raman spectra.

In general, the shift in the position of the diffraction peaks is a result of the change in the parameters of the unit cell of the zeolite crystals. As the Al3+ cation (0.53 Å) is replaced by the Cu2+ cation (0.73 Å), the diffraction peaks of the in situ synthesized Cu-containing samples are shifted to a lower angle (Fig. 2h and Supplementary Fig. 2), reflecting a gradual increase in cell volume35,50,51, which is in agreement with the results of the XRD and the FTIR spectra. The higher Si/Al molar ratio of MOR-Cu-n compared with the comparison samples (MOR-Na, MOR-Cu-Ex and MOR-Cu-Im) also corroborates the above-mentioned substitution of Cu for the framework Al (Supplementary Table 4). The Rietveld refinement of the high-resolution PXRD spectra corroborates these results (Supplementary Table 2), with the unit cell volume increasing from 2755.2 Å3 for MOR-Cu-150 to 2770.3 Å3 for MOR-Cu-210, and the volume expansion providing additional evidence for the incorporation of Cu atoms into the framework of the MOR-type zeolite52. The elevated crystallization temperature changed the sites of the copper component, resulting in more copper being embedded in the framework of the zeolite, but some of it was retained in the pores of the 12MR, which acted as a sieving effect (Supplementary Fig. 12). Raman spectroscopy, FTIR spectroscopy and XRD and its refinement results jointly confirm the addition of copper to the zeolite crystal framework of the MOR samples.

Multiprobe analysis of pore structure below 4 Å

Existing theoretical models of pore-size distributions (PSD) obtained using a single probe are relatively insensitive to ultramicroporous zeolite structures, as can be seen from similar PSD results (Supplementary Fig. 25). The precise quantification of fine microporous sizes in MOR-Cu-n was therefore achieved through sorption equilibrium isotherms testing using gases with molecular sizes ranging from 2.9 to 3.6 Å, such as H2, CO2, O2, Ar and N2 as probes (Fig. 3 and Supplementary Table 7–12). The overall trend of increasing micropore volume in the same sample with decreasing probe molecular size was attributed to the steric confinement of ultramicropores smaller than the probe size (Fig. 3b).

Sorption equilibrium isotherms at different temperatures for various gas probes on MOR-Cu-n with molecular sizes of 2.89 Å (H2@77 K), 3.30 Å (CO2@273 K), 3.47 Å (O2@77 K), 3.54 Å (Ar@87 K) and 3.64 Å (N2@77 K), where the value after @ is the corresponding test temperature (a). Micropore volumes were calculated with different probe gases according to the t-plot method (data points from left to right from H2, CO2, O2, Ar and N2 probe gases for MOR-Cu-n, respectively (b). Pore-size distribution of MOR-Cu-n (y-axis differential pore volume (∆V) was obtained from probes of consecutive sizes. VCO2 calculated by CO2 was subtracted from VH2, VO2 from VCO2, and so on) (c). Source data are provided as a Source Data file.

The micropore sizes of MOR-Cu-150 and MOR-Cu-170 were determined to be between 2.89 and 3.47 Å. MOR-Cu-190 was mainly distributed between 3.30 and 3.47 Å, and the pore sizes of MOR-Cu-210 and MOR-Cu-250 were mainly between 3.47 and 3.54 Å (Fig. 3c). It can be seen that a high crystallization temperature increases the zeolite pores, and this refined microporous pore size matches well with the pore size required for sieving separation of N2/CH4 (Fig. 1b).

For CO2 and H2 probes that are not sterically limited by ultramicropores, the higher the crystallization temperature (within 210 °C), the higher the Brunauer–Emmett–Teller surface area and the microporous volume shows an increasing trend (Supplementary Fig. 26 and Supplementary Table 11–12), corroborating the refinement results of PXRD. The specific surface area measured using the CO2 probe was as high as 200–300 m2 g–1, and the pore volume was around 0.10 cm3 g–1. These porosity data suggest that MOR-Cu-n has well-developed, but narrow, channels that allow the entry of CO2 (3.3 Å) and H2 (2.89 Å) with smaller kinetic diameters, but hinder the entry of larger N2 (3.64 Å) or even Ar (3.54 Å). This is clearly differentiated from the typical N2 type I adsorption isotherms of MOR-Na, MOR-Cu-Ex and MOR-Cu-Im zeolites (Supplementary Figs. 32a, 33a, 34a and Supplementary Table 13) and the larger pore distributions of 5.2 Å and 6.3 Å (Supplementary Figs. 32b, 33b, and 34b).

Molecular sieving of nitrogen/methane

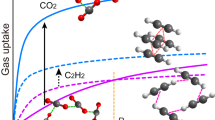

The pure component equilibrium adsorption isotherms of N2 and CH4 were measured (Fig. 4a and Supplementary Figs. 35–39), and MOR-Cu-n exhibited sieving properties for N2 and CH4. At 298 K and 1 bar, the N2 adsorption capacity of MOR-Cu-150 obtained by low-temperature crystallization was only 0.25 mmol g–1, whereas the N2 adsorption capacity of the three samples, MOR-Cu-190, MOR-Cu-210 and MOR-Cu-250, obtained after high-temperature crystallization was greater than 0.65 mmol g–1, which is almost three times the adsorption capacity of MOR-Cu-150, and is the highest value of the zeolite-based adsorbents that have been reported so far (Fig. 4c and Supplementary Table 14). The increase in N2 adsorption capacity was attributed to the larger microporous volume of the sample after increased crystallization temperature, which provided more space for adsorption. Comparison of PXRD before and after N2 adsorption showed (Supplementary Fig. 40) that the diffraction peaks after N2 adsorption saturation underwent an overall leftward shift, which suggested that the cell volume of MOR-Cu-n (n = 150, 170 and 210) became larger, providing more N2 adsorption space, and that preferentially entering N2 molecules were able to promote the adsorbent to possess a high N2 adsorption capacity. In contrast, the adsorption capacity of MOR-Cu-n for CH4 was almost negligible (<0.02 mmol g–1) under the same conditions, implying that CH4 molecules were excluded by the pores, which is consistent with the results of the structural pore size analysis. MOR-Cu-n possessed significant N2/CH4 sieving potential, which was attributed to the hindrance of CH4 by the copper component in the 12MR channel. At lower temperatures (273 K), while an increase in the N2 absorption capacity can be observed, the CH4 uptake remained unincreased (Supplementary Figs. 36–39).

Single-component adsorption (solid point) and desorption (hollow point) isotherms (a) for N2 (blue) and CH4 (red) by MOR-Cu-n at 298 K and 0–1 bar. N2/CH4 or CH4/N2 uptake ratios, with the uptake ratio defined as the ratio of adsorption capacities of N2 and CH4 (CH4 and N2) (both from pure gas isotherms) at 298 K and 1 bar (b). Point plots comparing the N2/CH4 uptake ratios and N2 adsorption of the adsorbent in this work and previous adsorbents reported in the literature (c). Source data are provided as a Source Data file.

MOR-Cu-210 has the largest uptake ratio of 62.1 (Fig. 4b and Supplementary Table 14), a value that is already much higher than reported N2 preferentially selective zeolites such as Na-clinoptilolite (1.8)40, Ca-clinoptilolite (3.3)40, Ag-clinoptilolite (6.8)39, K-ZSM-25 (3.9)33, K-MER-2.7 (5.3)37, ETS-4 (8.7)35, NaK-PHI@GI (20.9)38 and NaZSM-25 (47)4. Note that for adsorbents with sieving separation properties, the calculated uptake ratios are used only for qualitative comparisons because the lower uptake of unadsorbed molecules may give rise to large errors. Nevertheless, the high uptake ratios demonstrate the great potential of MOR-Cu-210 for efficient N2/CH4 sieving separation.

As a comparison, at 298 K and 273 K, MOR-Na, MOR-Cu-Ex and MOR-Cu-Im were able to adsorb both N2 and CH4 (Fig. 4b, Supplementary Figs. 41–45 and Supplementary Table 14), suggesting that both molecules were able to enter the pores easily without the sieving ability of N2 and CH4, and that larger CH4 molecules were adsorbed more than smaller N2, and all were CH4-selective adsorbents. This comparison highlights the critical role of precisely narrowed microchannels in fully utilizing molecular sieves.

Poor diffusive mass transfer and difficulty in desorption are long-standing problems faced by molecular sieving materials53. The desorption branching showed (Fig. 4a, Supplementary Fig. 26a and 26c) that the hysteresis phenomenon gradually disappeared with increasing crystallization temperature, indicating the enhancement of the desorption capacity of the sample, which was attributed to the larger effective pore size. The results obtained by PXRD refinement and multiple probe analysis of the pore structure explain this well. The variation of N2 test time with adsorption pressure (Supplementary Fig. 46) also showed that MOR-Cu-210 was able to reach adsorption equilibrium faster than MOR-Cu-150, with a 32% reduction in the total time consumed. The test results of adsorption kinetics also showed that the dynamic adsorption volume curve of N2 and the gas injection pressure curve of MOR-Cu-210 almost overlapped at a high inlet rate (200 mbar min–1), which showed the most excellent mass transfer effect (Fig. 5a). The mass transfer coefficient of MOR-Cu-210 up to 0.262 min–1 was 5.1 and 1.8 times higher than that of MOR-Cu-150 (0.052 min–1) and MOR-Cu-170 (0.146 min–1), respectively (Supplementary Fig. 47 and Supplementary Table 15). The kinetic adsorption of CH4 over time was measured, and its low adsorption (<0.01 mmol g–1) was nearly constant over 400 min, suggesting that the low adsorption of CH4 by MOR-Cu-210 is due to molecular sieving effects (Supplementary Fig. 48). Moreover, molecular dynamics (MD) simulations of MOR-Cu-210 showed that N2 could diffuse well along the z-axis direction in the pores, whereas CH4 could not enter the pores (Fig. 5b and Supplementary Fig. 49); the diffusion coefficients (D) of the two were D(N2) = 0.359 Å2 ps–1 and D(CH4) = 0.010 Å2 ps–1, which corroborated the molecular sieving effect of the adsorbent.

Adsorption and desorption kinetic curves of N2 at 298 K with an inlet gas flow rate of 200 mbar min–1 (a). MD simulated self-diffusion rates of N2 and CH4 molecules in MOR-Cu-210 (b). Cycling breakthrough tests for an equimolar binary mixture of N2/CH4 in a column packed with MOR-Cu-210 at a feed gas flow rate of 2 NmL min–1 (c). Experimental column breakthrough curves for the mixtures of N2/CH4 (50/50, v/v) on MOR-Cu-210 at a feed gas flow rate of 20 NmL min–1 (d). Breakthrough curves for other feed gas compositions, N2/CH4 (10/90, v/v) (e) and N2/CH4 (5/95, v/v) (f). Source data are provided as a Source Data file.

To verify the regeneration capacity of MOR-Cu-210, we conducted 10 cyclic adsorption tests of N2 (Supplementary Fig. 50), and the regeneration process before each test was simply a vacuuming operation without introducing additional high-energy-consuming heating treatment. The results showed that the adsorption capacity of N2 at 1 bar remained around 0.72 mmol g–1 during the 10 cyclic tests, and did not show any obvious adsorption loss phenomenon. The above phenomena show that MOR-Cu-210 has excellent desorption and regeneration ability, and the material can be completely regenerated by vacuuming and depressurization at room temperature. Calculation of the heat of adsorption (Qst) showed (Supplementary Fig. 51) that the Qst of N2 in MOR-Cu-n at zero coverage was in the range of 20–30 kJ mol–1, which belongs to the category of physical adsorption and is favorable for rapid regeneration under mild conditions.

Dynamic breakthrough experiments

To verify the feasibility of separating binary mixtures under dynamic conditions, we performed column breakthrough experiments on MOR-Cu-210 (Fig. 5c–f). At 298 K, equimolar N2/CH4 mixtures flowed through the activated solid-packed column at different rates (Fig. 5d and Supplementary Fig. 54a). Unsurprisingly, MOR-Cu-210 achieved a challenging clean separation of the N2/CH4 mixture. CH4 eluted at the beginning of the process, indicating that CH4 was not significantly adsorbed in the adsorption column and N2 was selectively trapped. After a period of time, as N2 accumulated in the adsorption column, N2 began to penetrate and was detected, followed by a gradual increase in the concentration of N2 in the exit gas stream, eventually reaching an equimolar concentration. The cycling and regeneration capabilities of MOR-Cu-210 were also investigated by breakthrough cycling experiments (Fig. 5c), in which the average residence times of both CH4 and N2 were not significantly shortened by 10 consecutive cycles under ambient conditions. The regeneration process before each test was a simple evacuation operation with no heat provision. Further breakthrough experimental results of the feedstock gas in wet gas–fresh bed and with CO2-competitive gases showed that MOR-Cu-210 still maintains a good dynamic separation of CH4 and N2 (Supplementary Fig. 58). These properties are clearly important for its potential industrial applications.

As the N2 content in the feedstock decreased, the breakthrough curves still showed an actual separation ability (Fig. 5e–f and Supplementary Fig. 54), which demonstrated the deep N2-trapping ability of MOR-Cu-210 at low concentrations (<1%). The N2/CH4 separation on MOR-Cu-210 was further investigated at different flow rates (5–20 NmL min–1). The results of the breakthrough experiments showed that high-purity CH4 could be produced under such conditions as well, achieving clean separation of N2/CH4 mixtures. Therefore, MOR-Cu-210 was identified as an efficient adsorbent for N2/CH4 separation and natural gas purification.

Discussion

We added atomically dispersed divalent transition metal copper components to the MOR zeolite by in situ high-temperature crystallization synthesis to precisely modulate the effective pore size. This synthesis strategy distinguished from the conventional post-processing approach by introducing a copper component, which enabled MOR-Cu-n to have molecular sieving ability, allowing only N2 molecules to enter whereas CH4 molecules were blocked. Refinement of the crystal structure as well as the characterization of the microporous structure showed that the increase in crystallization temperature not only changed the position of the copper component but also increased the specific surface area and pore volume, which contributed to the increase in N2 adsorption capacity and adsorption kinetic rate. MOR-Cu-210 obtained by crystallization at 210 °C has a record N2 adsorption capacity and N2/CH4 uptake ratio. This effectively alleviates the long-standing trade-off effect between adsorption capacity and selectivity, and this performance advantage is attributed to the unique synthesis method and the precise regulation of the microporous structure. Porosity data obtained based on multiple probe analyses as well as crystallographic and modeling studies comprehensively support the mechanistic explanation of the sieving N2/CH4 separation. Multiple breakthrough tests show real-world separation capabilities, demonstrating the excellent stability of the material. This work provides an important basis for the design and probing of large-pore zeolite materials with pore channels that can be fine-tuned to less than 4 Å.

Methods

Chemicals and reagents

All chemicals were used without further purification. LUDOX HS-40 colloidal silica as a silicon source (40 wt%, suspension in water) was supplied by Sigma-Aldrich. Sodium aluminate (NaAlO2, AR) as aluminum source was provided by Shanghai Macklin Biochemical Technology Co., Ltd. Alkali metal sources of sodium hydroxide (NaOH, AR, 96%) was provided by Shanghai Aladdin Biochemical Technology Co., Ltd. Copper chloride dihydrate (CuCl2·2H2O, AR) was purchased from Shanghai Aladdin Biochemical Technology Co., Ltd. Anhydrous oxalic acid (C2H2O4, 99.5%) was provided by Beijing Innochem Technology Co., Ltd. Distilled water was obtained from Sinopharm Chemical Reagent Co., Ltd.

Preparation of MOR-Cu-n

We introduced the copper component into the MOR zeolite by an in situ synthesis strategy, and the specific gel molar composition was set as 10.0 SiO2: 1.0 Al2O3: 2.0 Na2O: 0.5 CuO: 0.25 C2H2O4: 220 H2O. The calculated sodium hydroxide and sodium aluminate were sequentially placed in distilled water and stirred until completely dissolved to obtain Solution A. A certain amount of distilled water was pipetted and added to a beaker, after which weighed anhydrous oxalic acid and copper chloride dihydrate were added sequentially and stirred for 30 min to obtain the light blue emulsion B. The obtained emulsion B was added drop by drop to solution A and stirred for 30 min to obtain a mixture; under vigorous stirring, a certain amount of colloidal silica was added drop by drop to the mixture. The mixture was stirred at room temperature for 12 h, after which it was transferred to a PTFE liner, loaded into a stainless-steel reactor, and crystallization reaction was carried out in a homogeneous reactor at 60 r min–1 at different temperatures for 24 h, removed and cooled to room temperature, then washed by centrifugation with deionized water several times, and dried in an oven at 80 °C overnight. Finally, the target product MOR-Cu-n was obtained by high-temperature calcination at 650 °C for 6 h, where n represents different crystallization temperatures.

Preparation of MOR-Na

Conventional MOR zeolites with Na as a balancing cation were synthesized with reference to the literature54 in the following steps: (1) A certain amount of distilled water was pipetted and added to a beaker according to a molar ratio of 10.0 SiO2: 1.0 Al2O3: 2.0 Na2O: 220 H2O. A certain amount of distilled water was pipetted and added to the beaker, after which weighed sodium hydroxide and sodium aluminate were added and stirred for 10 min to dissolve them completely. (2) Under vigorous stirring, add a certain amount of colloidal silica drop by drop to the mixture obtained in step (1), stirring at room temperature for 12 h, after which transfer it to a PTFE liner, load it into a stainless steel reactor, and crystallize it in a homogeneous reactor at 60 r min–1 at 150 °C for 72 h, and then remove it and cool it to room temperature. The target product MOR-Na was obtained by centrifugal washing with deionized water for several times and overnight drying in an oven at 80 °C.

Preparation of MOR-Cu-Ex

Copper-containing MOR-Cu-Ex was obtained by postprocessing using ion exchange. The above-synthesized MOR-Na sample (1.5 g) was ion-exchanged with an aqueous solution of copper(II) chloride dihydrate (0.3 mol L–1) at 70 °C with stirring for 3 h. The solid was recovered by centrifugation, washed several times with deionized water and dried overnight in an oven at 80 °C to obtain the target product MOR-Cu-Ex.

Preparation of MOR-Cu-Im

Copper-containing MOR-Cu-Im was obtained by postprocessing using a wet impregnation method. The above-synthesized MOR-Na sample (1.5 g) was taken and mixed with an aqueous solution of copper(II) chloride dihydrate (0.3 mol L−1), followed by stirring for 10 h at room temperature. The water was evaporated at 100 °C and calcined at 650 °C for 6 h to obtain the final product MOR-Cu-Im.

Characterization

PXRD was recorded on a Bruker D8 Advance powder X-ray diffractometer operating at 40 kV and 40 mA under the following conditions: Cu Kα radiation source (λ = 1.5418 Å), Göbel mirror, θ–2θ scan, 2θ = 5°–50°, step size = 0.01° (2θ), scan speed = 0.2 s/step. Thermogravimetric analysis was performed under air conditions with a heating rate of 10 °C min–1 using a Netzsch STA449 F5 thermogravimetric analyzer with a temperature range of 30–800 °C. Elemental analyses of Na, Si, Al, O and Cu in all samples were determined via inductively coupled plasma–optical emission spectroscopy (PerkinElmer Avio 200 apparatus), and the samples were ablated to a clear, transparent liquid before measurement. The infrared spectra were obtained using a Shimadzu FT-ir8400s Fourier transform infrared spectrometer. The scanning electron microscopy images were recorded in a Hitachi SU8000 microscope at 1.0–3.0 kV and various accelerating voltages (1.0–20 kV) and energy-dispersive X-ray spectroscopy (EDX) was carried out using a Smart EDX system equipped with X-ray mapping at an accelerating voltage of 30 kV. HAADF–STEM images and corresponding EDX spectral mapping were taken on an FEI Talos F200X G2 electron microscope. XPS was performed on a Thermo Scientific K-Alpha XPS equipped with Al Kα radiation (1486.6 eV). The sample was fed into the analysis chamber at a pressure of less than 2.0 × 10–7 mbar, with a spot size of 400 μm, an operating voltage of 12 kV, and a filament current of 6 mA; the full-spectrum scanning flux energy was 150 eV in steps of 1 eV; and the narrow-spectrum scanning flux energy was 50 eV in 0.1 eV steps. UV–vis diffuse reflectance spectra in the 200–800 nm range were recorded on a PerkinElmer Lambda 650 spectrometer. Raman spectra were obtained on an InVia 1WU072 Raman spectrometer with λ = 532 nm. X-ray absorption spectroscopy measurements were performed using an Easy XAFS150 system (Easy XAFS LLC, USA).

Powder X-ray diffraction and Rietveld refinement

PXRD data for the Rietveld refining process were collected on a Bruker D8 Advance powder X-ray diffractometer. Before scanning, the samples were pretreated at 300 °C for 3–5 h for in situ dehydration under evacuation, and then high-precision PXRD data were collected in situ at room temperature in an airtight environment with no adsorbed N2 (MOR-Cu-n). For the collection of PXRD data for N2-loaded samples (MOR-Cu-n@N2), additional N2 adsorption experiments were required, followed by diffraction data collection. The scans were performed with an operating voltage of 40 kV and a current of 40 mA under the following conditions: Cu Kα radiation source (λ = 1.5418 Å), Göbel mirror, θ–2θ scan, 2θ = 4°–100°, step size = 0.01° (2θ), scan speed = 1.5 s/step. Repeat scanning mode was turned on until the intensity of the strongest diffraction peaks was >10,000 counts to end the scan. MOR structures from the IZA structure database were taken as the initial model for the Rietveld refinement process of all forms of MOR zeolite employing the TOPAS-Academic V3.0 program55.

Synchrotron X-ray diffraction and Rietveld refinement

High-resolution SXRD was performed at beamline ID31 of the European Synchrotron Radiation Facility. The sample powders were loaded into cylindrical slots (approx. 1 mm thickness) held between Kapton windows in a high-throughput sample holder. Each sample was measured in transmission with an incident X-ray energy of 75.051 keV (λ = 0.16520 Å). Measured intensities were collected using a Pilatus CdTe 2 M detector (1679 × 1475 pixels, 172 × 172 μm2 each) positioned with the incident beam in the corner of the detector. The sample-to-detector distance was approximately 1.5 m for the high-resolution SXRD measurement. Background measurements for the empty windows were measured and subtracted. NIST SRM 660b (LaB6) was used for geometry calibration. The integration of the 2D XRD pattern was performed with the software pyFAI, followed by image integration, including flat-field, geometry, solid-angle, and polarization corrections. The SXRD data was analyzed using the Rietveld refinement method available in TOPAS-Academic V7.0 software55.

Pore structure analysis via probe gases

N2 adsorption–desorption at 77 K, Ar adsorption–desorption at 87 K, O2 adsorption–desorption at 77 K, CO2 adsorption–desorption at 273 K and H2 adsorption–desorption curves at 77 K were measured on a volumetric gas sorption analyzer (ASAP-2460, Micromeritics, USA). Before testing, each sample was vacuum degassed at 300 °C for 6 h under a high vacuum (<15 µbar). This temperature setting was based on the weight-loss step of the thermogravimetric analysis curve. The purity of all gas probes used was 99.999%.

Single-component gas adsorption and desorption measurements

CH4 and N2 adsorption and desorption isotherms were measured using a Micromeritics ASAP 2460 instrument at 298 K and 273 K; before testing, each sample was vacuum degassed at 300 °C for 6 h under a high vacuum (<15 µbar). The purity of the CH4 and N2 used was 99.99% and 99.999%, respectively. For the 10 cycles of N2 adsorption tests, the regeneration process prior to each test was a simple in situ evacuation for 1 h without the introduction of additional energy-intensive heating treatments.

Adsorption kinetics

Kinetic adsorption was measured with an Intelligent Gravimetric Analyzer (IGA001, Hiden, UK), which uses a gravimetric technique to measure accurately gas sorption on materials under diverse operating conditions. The system was degassed at 300 °C for 3–5 h until no further weight loss was observed. When the system temperature was reduced to 298 K, the adsorption test was started. The adsorption equilibrium time was set to 60 min to collect the adsorption equilibrium data fully.

The pseudo-first-order kinetic model was used to fit the gas adsorption kinetics. The equation is as follows:

with qt the amount of adsorbed solute, qe its value at equilibrium, k1 the pseudo-first-order rate constant and t the time56.

Molecular dynamics simulations

The structure of the material was constructed by expanding the crystal structure unit in three directions. The dimension of the final obtained molecular sieve was 54.3 × 61.1 × 52.6 Å3. Two solid models 30 Å apart were then placed in a rectangular box with a z-axis length of 150 Å, with the central axis of the pores along the z direction. 50 N2 and 50 CH4 molecules were placed in the 30 Å vacuum between the two molecular sieve models. Such modeling facilitates the observation of the movement of the molecules of the gas. The simulations were performed using the Forcite module in the Materials Studio software (version 2023). The COMPASSII force field57 was adopted to describe the inter- and intramolecular interactions during the MD simulations. The atomic charges of all the components were assigned using the QEq method. The simulated system was first relaxed using the Smart algorithm with a convergence tolerance of 0.001 kcal/mol. Subsequently, a 5 ns simulation with a time step of 1.0 fs under NVT ensemble was performed. The temperature was set at 298 K and maintained using the Nosé thermostat58,59,60. The long-range electrostatic interactions were truncated using the Ewald method61. The trajectories were saved every 50 fs for further data analysis.

Fitting of pure component isotherms

The single-component N2 and CH4 adsorption isotherms of all samples at 298 K and 273 K were fitted by the Langmuir model.

Where p is the pressure of the bulk gas at equilibrium with the adsorbed phase, qm is saturated adsorption capacity, b is the Langmuir equilibrium constant, and q represents adsorption capacity.

Calculation of isosteric heat of adsorption

The heats of adsorption of each component were determined precisely according to the virial fitting parameters of single-component adsorption isotherms measured at 273 K, 285 K, and 298 K up to 1 bar. The isotherms were fitted to a virial equation, Eq. (3):

Here, P is the pressure expressed in bar, N is the amount absorbed in mmol g-1, T is the temperature in K, ai and bj are virial coefficients, and m, n represent the number of coefficients required to adequately describe the isotherms. The values of the virial coefficients a0 through am were then used to calculate the isosteric heat of absorption using the following expression Eq. (4):

Qst is the coverage-dependent isosteric heat of adsorption and R is the universal gas constant.

Breakthrough experiment

The breakthrough experimental device consists of three parts: the gas flow system, adsorption bed and mass spectrometer. The adsorbent powder was pressed into tablets using a tablet press at a pressure of 4 MPa and then sieved through a stainless-steel sieve into 40–60-mesh particles. Then, 3.28 g of adsorbent was loaded into a homemade adsorbent column (inner diameter 4 mm × length 300 mm). Mass spectrometry (MS, HPR-20, Hiden) was used to monitor the gas concentration at the outlet of the adsorption bed. In the experiment, we loaded the MOR-Cu-210 particles into the stainless-steel columns separately and then activated them at 300 °C for 3–5 h. At the same time, the adsorption bed was purged with a carrier gas (He ≥ 99.999%) at a rate of 20 NmL min–1. When the bed temperature dropped to 25 °C, the mixed gas N2/CH4 (50/50, 10/90, 5/95 and 1/99, v/v) was introduced into the bed (flow rate: 2–20 NmL min–1), and then the outlet gas was analyzed using mass spectrometry. In the cyclic breakthrough experiments, the adsorbent bed was regenerated after 1 h of degassing at room temperature using a vacuum pump.

Reporting summary

Further information on research design is available in the Nature Portfolio Reporting Summary linked to this article.

Data availability

The study’s supporting data can be found in this article and the Supplementary Information. The data that support the findings of this study are openly available in figshare at https://doi.org/10.6084/m9.figshare.29606558 (ref. 62). Source data are provided with this paper.

References

Peng, Q. et al. Enhancing size-selective adsorption of CO2/CH4 on ETS-4 via ion-exchange coupled with thermal treatment. Ind. Eng. Chem. Res. 62, 9313–9324 (2023).

Shang, J. et al. Temperature controlled invertible selectivity for adsorption of N2 and CH4 by molecular trapdoor chabazites. Chem. Commun. 50, 4544–4546 (2014).

Zhou, S. et al. Asymmetric pore windows in MOF membranes for natural gas valorization. Nature 606, 706–712 (2022).

Mousavi, S. H. et al. Nitrogen rejection in natural gas using NaZSM-25 zeolite. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 25, 18259–18265 (2023).

Ding, M., Liu, X., Ma, P. & Yao, J. Porous materials for capture and catalytic conversion of CO2 at low concentration. Coord. Chem. Rev. 465, 214576 (2022).

Liu, J. et al. Superhydrophobic zeolitic imidazolate framework with suitable SOD cage for effective CH4/N2 adsorptive separation in humid environments. AIChE J. 68, e17589 (2022).

Xu, S. et al. Self-pillared ultramicroporous carbon nanoplates for selective separation of CH4/N2. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 60, 6339–6343 (2021).

Wang, S., Wu, P., Fu, J. & Yang, Q. Heteroatom-doped porous carbon microspheres with ultramicropores for efficient CH4/N2 separation with ultra-high CH4 uptake. Sep. Purif. Technol. 274, 119121 (2021).

Du, S. et al. Facile synthesis of ultramicroporous carbon adsorbents with ultra-high CH4 uptake by in situ ionic activation. AIChE J. 66, e16231 (2020).

Tang, X. et al. Synthesis of nanosized IM-5 zeolite and its CH4/N2 adsorption and separation. Sep. Purif. Technol. 318, 124003 (2023).

Kencana, K. S., Gi Min, J., Christian Kemp, K. & Bong Hong, S. Nanocrystalline Ag-ZK-5 zeolite for selective CH4/N2 separation. Sep. Purif. Technol. 282, 120027 (2022).

Wu, Y. et al. Significant enhancement in CH4/N2 separation with amine-modified zeolite Y. Fuel 301, 121077 (2021).

Yang, J. et al. Down-sizing the crystal size of ZK-5 zeolite for its enhanced CH4 adsorption and CH4/N2 separation performances. Chem. Eng. J. 406, 126599 (2021).

Yang, J. et al. K-Chabazite zeolite nanocrystal aggregates for highly efficient methane separation. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 134, e202116850 (2022).

Wang, S., Shivanna, M. & Yang, Q. Nickel-based metal–organic frameworks for coal-bed methane purification with record CH4/N2 selectivity. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 61, e202201017 (2022).

Niu, Z. et al. A metal–organic framework based methane nano-trap for the capture of coal-mine methane. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 58, 10138–10141 (2019).

Lv, D. et al. Improving CH4/N2 selectivity within isomeric Al-based MOFs for the highly selective capture of coal-mine methane. AIChE J. 66, e16287 (2020).

Chang, M. et al. Separation of CH4/N2 by an ultra-stable metal–organic framework with the highest breakthrough selectivity. AIChE J. 68, e17794 (2022).

Li, J.-R., Kuppler, R. J. & Zhou, H.-C. Selective gas adsorption and separation in metal–organic frameworks. Chem. Soc. Rev. 38, 1477–1504 (2009).

Lee, K. et al. Design of a metal–organic framework with enhanced back bonding for separation of N2 and CH4. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 136, 698–704 (2014).

Jaramillo, D. E. et al. Selective nitrogen adsorption via backbonding in a metal–organic framework with exposed vanadium sites. Nat. Mater. 19, 517–521 (2020).

Yoon, J. W. et al. Selective nitrogen capture by porous hybrid materials containing accessible transition metal ion sites. Nat. Mater. 16, 526–531 (2017).

Zhang, F. et al. Efficient N2/CH4 separation in a stable metal–organic framework with high density of open Cr sites. Sep. Purif. Technol. 281, 119951 (2022).

Zhang, F. et al. Substituent-induced electron-transfer strategy for selective adsorption of N2 in MIL-101(Cr)-X metal–organic frameworks. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 14, 2146–2154 (2022).

Wang, J.-H. et al. Solvent-assisted metal metathesis: a highly efficient and versatile route towards synthetically demanding chromium metal–organic frameworks. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 56, 6478–6482 (2017).

Wang, H., Liu, Y. & Li, J. Designer metal–organic frameworks for size-exclusion-based hydrocarbon separations: progress and challenges. Adv. Mater. 32, 2002603 (2020).

Adil, K. et al. Gas/vapour separation using ultra-microporous metal–organic frameworks: insights into the structure/separation relationship. Chem. Soc. Rev. 46, 3402–3430 (2017).

Ackley, M. W., Giese, R. F. & Yang, R. T. Clinoptilolite: untapped potential for kinetics gas separations. Zeolites 12, 780–788 (1992).

Moliner, M., Martínez, C. & Corma, A. Synthesis strategies for preparing useful small pore zeolites and zeotypes for gas separations and catalysis. Chem. Mater. 26, 246–258 (2014).

Bai, R., Song, X., Yan, W. & Yu, J. Low-energy adsorptive separation by zeolites. Natl. Sci. Rev. 9, nwac064 (2022).

Fu, D. & Davis, M. E. Carbon dioxide capture with zeotype materials. Chem. Soc. Rev. 51, 9340–9370 (2022).

Palomino, M., Corma, A., Jordá, J. L., Rey, F. & Valencia, S. Zeolite Rho: a highly selective adsorbent for CO2/CH4 separation induced by a structural phase modification. Chem. Commun. 48, 215–217 (2012).

Zhao, J. et al. Nitrogen rejection from methane via a “trapdoor” K-ZSM-25 zeolite. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 143, 15195–15204 (2021).

Nandanwar, S. U., Corbin, D. R. & Shiflett, M. B. A review of porous adsorbents for the separation of nitrogen from natural gas. Ind. Eng. Chem. Res. 59, 13355–13369 (2020).

Kuznicki, S. M. et al. A titanosilicate molecular sieve with adjustable pores for size-selective adsorption of molecules. Nature 412, 720–724 (2001).

Vosoughi, M. & Maghsoudi, H. Characterization of size-selective kinetic-based Ba-ETS-4 titanosilicate for nitrogen/methane separation: chlorine-enhanced steric effects. Sep. Purif. Technol. 284, 120243 (2022).

Tang, X., Wei, M., Bai, X., Li, J. & Yang, J. Precise pore size modulation of K-MER zeolites for N2 trapping. Sep. Purif. Technol. 339, 126601 (2024).

Tang, X. et al. Optimized mass transfer of PHI-type zeolite for nitrogen/methane sieve separation. Chem. Eng. J. 495, 153630 (2024).

Kennedy, D. A., Khanafer, M. & Tezel, F. H. The effect of Ag+ cations on the micropore properties of clinoptilolite and related adsorption separation of CH4 and N2 gases. Micropor. Mesopor. Mater. 281, 123–133 (2019).

Ackley, M. W. & Yang, R. T. Adsorption characteristics of high-exchange clinoptilolites. Ind. Eng. Chem. Res. 30, 2523–2530 (1991).

Ackley, M. W. & Yang, R. T. Diffusion in ion-exchanged clinoptilolites. AIChE J. 37, 1645–1656 (1991).

Zhou, Y. et al. Self-assembled iron-containing mordenite monolith for carbon dioxide sieving. Science 373, 315 (2021).

Sushkevich, V. L., Palagin, D., Ranocchiari, M. & van Bokhoven, J. A. Selective anaerobic oxidation of methane enables direct synthesis of methanol. Science 356, 523 (2017).

Tao, L. et al. Speciation of Cu-Oxo clusters in ferrierite for selective oxidation of methane to methanol. Chem. Mater. 34, 4355–4363 (2022).

Deplano, G. et al. Copper pairing in the mordenite framework as a function of the cui/cuii speciation. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 60, 25891–25896 (2021).

Yu, Y., Xiong, G., Li, C. & Xiao, F.-S. Characterization of aluminosilicate zeolites by UV Raman spectroscopy. Micropor. Mesopor. Mater. 46, 23–34 (2001).

Twu, J., Dutta, P. K. & Kresge, C. T. Vibrational spectroscopic examination of the formation of mordenite crystals. J. Phys. Chem. 95, 5267–5271 (1991).

Liu, S. et al. Synthesis and characterization of the Fe-substituted ZSM-22 zeolite catalyst with high n-dodecane isomerization performance. J. Catal. 330, 485–496 (2015).

Li, Y. et al. Promoting the activity of Ce-incorporated MOR in dimethyl ether carbonylation through tailoring the distribution of Brønsted acids. Appl. Catal. B Environ. 256, 117777 (2019).

Meng, Y. et al. One-step hydrothermal synthesis of manganese-containing MFI-type zeolite, Mn–ZSM-5, characterization, and catalytic oxidation of hydrocarbons. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 135, 8594–8605 (2013).

Wang, X. et al. The inorganic cation-tailored “trapdoor” effect of silicoaluminophosphate zeolite for highly selective CO2 separation. Chem. Sci. 12, 8803–8810 (2021).

Dubray, F. et al. Direct evidence for single molybdenum atoms incorporated in the framework of MFI zeolite nanocrystals. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 141, 8689–8693 (2019).

Cui, J. et al. A molecular sieve with ultrafast adsorption kinetics for propylene separation. Science 383, 179–183 (2024).

Choi, H. J. & Hong, S. B. Effect of framework Si/Al ratio on the mechanism of CO2 adsorption on the small-pore zeolite gismondine. Chem. Eng. J. 433, 133800 (2022).

Scardi, P., Azanza Ricardo, C. L., Perez-Demydenko, C. & Coelho, A. A. Whole powder pattern modelling macros for TOPAS. J. Appl. Crystallogr. 51, 1752–1765 (2018).

Simonin, J.-P. On the comparison of pseudo-first order and pseudo-second order rate laws in the modeling of adsorption kinetics. Chem. Eng. J. 300, 254–263 (2016).

Sun, H. et al. COMPASS II: extended coverage for polymer and drug-like molecule databases. J. Mol. Model. 22, 47 (2016).

Shuichi, N. Constant temperature molecular dynamics methods. Prog. Theor. Phys. Suppl. 103, 1–46 (1991).

Nosé, S. A unified formulation of the constant temperature molecular dynamics methods. J. Chem. Phys. 81, 511–519 (1984).

Nosé, S. A molecular dynamics method for simulations in the canonical ensemble. Mol. Phys. 52, 255–268 (1984).

Tosi, M. Evaluation of electrostatic lattice potentials by the Ewald method. Solid. State Phys. 16, 107–120 (1964).

Tang, X. et al. In situ synthesis of copper-based mordenite for nitrogen/methane sieving Data sets. figshare https://doi.org/10.6084/m9.figshare.29606558.

Acknowledgements

We acknowledge the financial support from the National Natural Science Foundation of China (No. 22378287 to J.Y., 22478272 to X.W., 22308238 to L.W. and 22408258 to F.Z.).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

X.T. designed the experiments and conducted sample synthesis, characterization, data processing, graph drawing, and article writing. X.B., Y.W., and X.L. performed the collection of some of the adsorption data. F.Z., L.W., and X.W. performed article revisions. J.L. and J.Y. designed the whole project. All authors contributed to the scientific discussion.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Peer review

Peer review information

Nature Communications thanks Jun Wang, and the other anonymous reviewer(s) for their contribution to the peer review of this work. A peer review file is available.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Source data

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Tang, X., Bai, X., Wang, Y. et al. In situ synthesis of copper-based mordenite for nitrogen/methane sieving. Nat Commun 16, 8065 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-025-63537-5

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-025-63537-5