Abstract

Processing ultra-high molecular weight polymers presents significant experimental challenges due to their high viscosity, which requires elevated shear rates and consequently increases energy demands. Here, we explore the role of the geometry of nanoparticles- spheres, rods, and tetrapods - in controlling the effective viscosity of polymer nanocomposites. Intriguingly, our combined experiments and molecular dynamics simulations reveal a significant decrease in the viscosity of composites with tetrapod nanoparticles, without compromising mechanical or thermal integrity, unlike sphere and rod, which exhibit minimal impact on the viscosity at the same level of loading. We show that the inner curvatures of the nanotetrapods impose strong physical confinement introducing an entropic cost for polymers to access this space. The inaccessible volume creates polymer packing frustration around nanotetrapod surfaces, which, in turn, increases their mobility and decreases the overall viscosity of the composite. Nanotetrapods prove to be effective flow promoters while preserving good dispersion within a polymer melt, offering significant potential for advanced polymer processing applications.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Polymers are central to a wide range of products due to their high processability, tunable properties, and adaptability to a wide range of performance demands. However, the entangled nature of long polymer chains significantly increases viscosity, with polymers containing 10,000 monomers flowing approximately seven orders of magnitude slower than those with 100 monomers under the same stress. This dramatic reduction in flow requires higher shear forces, leading to increased energy consumption during processing1,2,3. Strategies to reduce polymer viscosity while preserving mechanical integrity are crucial4. Incorporating nanoparticles (NPs) into polymers alters their viscosity as a function of NP concentration, size, surface ligands, and particle-polymer interactions. Over the past few decades of studies5,6,7,8,9,10,11,12,13, the prevailing trend is a viscosity increase due to NP loading in a polymer matrix. Additionally, NPs can also jeopardize phase stability by triggering aggregation or phase separation—particularly at high loadings and/or when chemical compatibility with the matrix is poor. Achieving uniform dispersion of added NPs while simultaneously lowering the viscosity of the composite thus remains a persistent challenge in polymer science and engineering. While NPs are loading, their size and interaction with base polymers have been extensively studied in prior works; the effect of NP shape on the properties of polymers14,15 remains poorly understood. In particular, the impact of anisotropic and architecturally complex NPs—such as tetrapods (TPs)—on polymer dynamics has not been explored. We posit that the TP geometry can create tortuous interfaces and create packing frustration in a polymer matrix, and effectively reduce the viscosity of composites. Our study establishes this approach with the aim of improving polymer processability and performance.

The key question we investigate here is how NP shape or architecture influences the properties of polymer nanocomposites (PNCs)? To this end, we explore the effect of NP architecture—specifically TPs alongside commonly-used shapes such as spherical nanoparticles (SNs) and nanorods (NRs) on the rheological properties of polystyrene (PS). We experimentally assess how NP shape influences the viscosity of PNCs in bulk using conventional rheological studies, and in thin films using dewetting-based thin film rheological measurements. Results from bulk and thin films reveal excellent quantitative agreement. The viscosity of SN-based PNCs and NR-based PNCs revealed an expected increase in the viscosity. In contrast, the viscosity of PNCs based on TP nanoparticles decreased significantly when compared with pristine polymers. This is surprising as the exposed surface area for polymer adsorption is much larger for TP-based PNCs. For instance, tetrapod-shaped concrete blocks at macroscopic scales are well-known to break flow16. We perform coarse-grained molecular dynamics simulations (CGMD) to shed light on this intriguing observation. The simulation results exhibit strong agreement with experimental observations, reinforcing the validity of the underlying model and computational approach. Simulations further reveal a reduction of polymer density around TPs, in comparison with SNs and NRs, though the nature of polymer-particle interactions is identical for all three cases. This is due to the highly confined space around a nanotetrapod that imposes entropic penalties on polymers accessing these regions. We determine a quantitative correlation between the composite viscosity, deduced from experiments and simulations, and the inaccessible volume around a TP. Notably, this effect of TPs disappears when introduced into non-polymeric Lennard-Jones fluids or into short-chain polymers with a molecular weight below the entanglement length. TP NPs could therefore serve as an effective means for enhancing flow in high-molecular-weight polymers.

Results and discussion

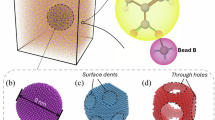

We synthesize sterically stabilized CdSe NPs with three distinct shapes—SN, NR, and TP and disperse them in PS with molecular weight 1250 kDa, as schematically shown in Fig. 1a–c. Table 1 summarizes the composition, viz, the dimensions of NPs considered in our experiments and simulations. Details on the synthesis and characterization of the CdSe NPs are provided in the Supplementary Information (SI) (Figs. S1–S11). We examine the rheological properties in two geometries: a) bulk melt slabs and b) thin films. We use conventional melt rheological measurements for the bulk samples. However, quantifying the rheological parameters of a thin film is quite challenging using conventional techniques. Thus, we use the dewetting approach, which is a simple yet effective method as has been used earlier to extract the viscoelastic properties of polymer films17,18,19. Here, the rate at which a polymer film dewets an unfavorable surface, in the form of nucleation and growth of holes, is a sensitive function of the rheological characteristics of the film. Details on dewetting (Figs. S12 and S13) and melt rheometry (Fig. S14) experiments are provided in the SI and Materials and Methods section. Figure 2a displays the dewetting velocity (V(tdew)) over dewetting time (tdew) for holes nucleated in PS thin films containing 1% CdSe SNs and NRs, when annealed at Tdew = 200 °C = Tg + 100 °C, where Tg is the glass transition temperature of bulk PS. The inclusion of both SNs and NRs reduces the dewetting velocity of the composite compared to the pure PS (1250 kDa). In contrast, TP-PS thin films display higher dewetting velocity than a PS film, suggesting better flow with the inclusion of TPs. In Fig. 2a, we only show V(tdew) corresponding to holes nucleated after large delay times to avoid the influence of preparation-induced non-equilibrium effects19,20,21,22,23. The temporal evolution of the dewetting velocity followed \(V({t}_{{{{\rm{dew}}}}}) \sim {t}_{{{{\rm{dew}}}}}^{-\alpha }\) with α = 0.56 ± 0.04 ≈ 0.5 predicted for viscoelastic flow. For (preparation-induced) stress-driven flow, α = 118,19,20,22. The α value deduced from our experiments reveals the absence of stress-driven transient effects. Thus, the deviations in dewetting velocities reveal the influence of NP shape on the flow behavior at constant NP loading.

a Temporal evolution of dewetting velocity \(\left(V({t}_{{{{\rm{dew}}}}})=\frac{dR}{d({t}_{{{{\rm{dew}}}}})}\right)\) for pure PS and PNC thin films of thickness 207 ± 1 nm dewetted at Tdew = 200 °C for tdew = 200 s. b Complex viscosity (∣η*∣) calculated from melt rheology experiments (Trheo = 200 °C) using oscillatory shear as a function of shear rate. The dotted red line signifies the viscosity at a strain rate = 0.00159 s−1. c Calculated viscosity using equation (2) for the pure PS and PNC thin films dewetted at Tdew = 200 °C is shown as a function of tdew. The horizontal lines in (c) represent time-average viscosity. The error bars in the figure represent the standard deviation of the data. The legends in (b) are also applicable to (a) and (c).

Results from a conventional rheometer on bulk melt slabs are shown in Fig. 2b by plotting the strain rate dependence of the complex viscosity (∣η*∣) of PS and PNC melts at Trheo = 200 °C. While the composites of SN and NR exhibit a viscosity higher than that of the pristine polymer, the composites with TP display a relatively lower viscosity. These results nicely corroborate the dewetting observations as reported in Fig. 2a. This confirms that the substrate in dewetting experiments does not alter the PNC dynamics, as similar trends appear in bulk rheology. The viscosity values of pure PS (Mw = 1250 kDa) obtained in our study are in excellent agreement with those reported in the literature for PS films19, as well as for PS melt slabs measured using rheometry24,25.

To quantify the viscosity η, from dewetting experiments, we rely on the model developed by Brochard-Wyart and coworkers26,27. This model has been successfully utilized in literature for polymer films on slippery substrates, as in our case17,28. This model pertains to the dewetting of polymer films slipping on a solid substrate to create plug flow, i.e., a constant velocity throughout the film thickness. During dewetting, the driving capillary force at the contact line is balanced by the viscous force following26,27,

where, \(k=\frac{\eta }{b}\) = solid friction co-efficient, \(b=a\frac{{N}^{3}}{{N}_{e}^{2}}\) = slippage length, N = number of monomers in the polymer chain, Ne = number of monomers between entanglements, a = monomer length, γ = surface tension, θ(tdew) = dynamic contact angle (detailed calculation can be found in Section 2.3 and Fig. S15 in SI), V(tdew)= time-dependent dewetting velocity, W(tdew) = time dependent rim width around the growing hole. Thus, the force balance equation shown in equation (1) yields the time-dependent viscosity (η(tdew)):

In the equation above, all parameters on the right-hand side are accessible from experiments and γ = 28 mN/m is used from literature17,20. Thus, we use equation (2) to extract the viscosity of PNCs without any fit parameters. The time-dependent viscosities η(tdew) are summarized in Fig. 2c for all the composites with SN, NR, and TP with varying arm lengths. All films exhibit a constant viscosity over time tdew, suggesting that the shear rate (\(\dot{\gamma }=\frac{V({t}_{{{{\rm{dew}}}}})}{W({t}_{{{{\rm{dew}}}}})}\approx 0.00159{{{{\rm{s}}}}}^{-1}\)) is constant. Following the bulk rheological data shown in Fig. 2b, \(\dot{\gamma }\approx 0.00159{{{{\rm{s}}}}}^{-1}\) should yield the zero-shear viscosity. The dewetting results reveal that SN and NR loaded polymer films exhibit higher viscosities than PS films, whereas TP-based PNC films show reduced viscosity relative to PS. This trend correlates with dewetting observations in Fig. 2a, where η > η0 for SN and NR cases, and η0 > η for TP cases. Interestingly, as depicted in Fig. 2c, η(tdew) decreases monotonically with increasing TP size. The same pattern is reflected in the complex viscosity ∣η*∣ vs. strain rate \(\dot{\gamma }\) for both PS and PNC bulk melt slabs in Fig. 2b. Clearly, for both geometries, TP-based composites show a decrease in viscosity compared to pristine polymers. We note that there is roughly a tenfold difference between viscosity estimates from dewetting and rheometry, likely due to model approximations in the dewetting analysis26,27 neglecting the non-linear polymer-substrate interfacial friction29, and altered polymer entanglement at the substrate interface30. Nevertheless, both methods conclusively capture the general trend of viscosity reduction upon TPs incorporation. Further, a control on the arm length of the TPs allowed us to decrease the viscosity by an order of magnitude. This observation contrasts with the expectation for a favorable surface: An increase in surface area enhances polymer–particle contacts, which would be expected to enhance the viscosity. How do we rationalize this intriguing observation?

We perform CGMD simulations to establish the underpinning molecular mechanisms of the improved ability of TP-polymer composites to flow. We use the Kremer-Grest bead-spring polymer model31 for these simulations. SNs are modeled as a single Lennard-Jones (LJ) particle with a diameter of 1σ. For NR and TP, rigid bodies are constructed from multiple LJ particles to replicate their respective shapes. Table 1 summarizes the parameters of the various PNC models used in CGMD simulations. Representative CGMD snapshots illustrating the spatial arrangement of NPs—SNs, NRs, and TPs—in polymer melts are shown in Fig. 3a–c. Magnified views highlighting the local environment surrounding an SN, NR4, and TP4 are presented in Fig. 3d, e and f, respectively. The corresponding NP-NP pair-correlation functions are plotted in Fig. 3g, as a function of the distance between their centers of mass. For the NR4 and TP4 systems, the pair-correlation function approaches unity from below as the interparticle distance increases, indicative of uniform dispersion within the polymer matrix. This suggests a weak potential of mean force between NPs in NR and TP systems, which facilitates better dispersion in the polymer matrix. This is consistent with our experimental observations, which are summarized in Fig. S17 of the SI, wherein we do not observe any microphase separation in TP14-based systems. Moreover, we perform non-equilibrium molecular dynamics (NEMD) simulations to obtain the viscosity by shearing the simulation box in parallel-plate geometry. The details of NEMD simulations can be seen in the Methods section. We calculate the ratio of the PNC viscosity to the pure polymer viscosity in the Newtonian regime from NEMD simulations for all the cases. We compare the viscosity ratio, as calculated from simulations, with that of our experiments in Fig. 4 for all the composites. Our experimental data clearly show that the viscosity ratio is larger than unity for SN and NR2-based composites, in accordance with previous reports9,15, The viscosity ratios are progressively smaller for TP-based composites with increasing arm length. This experimental trend of viscosity reduction with the NP shape is in agreement with our simulation data. We also note that, in simulations, we quantify the viscosity of several NRs with different lengths alongside the L = 2σ, which is comparable to the experimental system. It indicates that the viscosity ratio can decrease slightly from unity for longer NRs.

Ratio of the PNC viscosity to that of the pure polymer (\(\frac{\eta }{{\eta }_{0}}\)) a computed from MD simulations and b estimated from experimental techniques (dewetting dynamics in closed symbols and melt rheology in open symbols). Simulation viscosity is computed for the shear rate \(\dot{\gamma }=1{0}^{-5}{\tau }^{-1}\), where τ is the unit of time in simulations. All the experimental viscosity values are compared at Texperiment = 200 °C and at uniform strain rate (\(\dot{\gamma }\)) = 0.00159 s−1. The yellow shaded region denotes the condition when η > η0. The purple shaded region denotes the condition when η0 > η. The gray shaded region corresponds to η0 = η. The error bars in the figure represent the standard deviation of the data.

Overall, our simulations and experiments synergistically demonstrate that the NP shape controls the viscosity of the composites, albeit in a non-intuitive manner, especially for TPs. The inclusion of particles in polymer melts with neutral or favorable interactions with polymers is expected to increase the viscosity of the composites5,32. In addition, given the favorable interface between particles and polymers, we may expect the polymer chains to adsorb to the particles, which is expected to scale with the surface area. This may explain the experimental results of SN- and NR-based composites. Alternatively, simulations also reveal increased viscosity for SN-based composites, but NR-based composites exhibit a viscosity similar to that of the melt, or even a slight decrease, when the NRs are sufficiently long. However, the results of TP-based composites are surprising. Though there is an increase in the exposed surface area of the inclusions in TP-based composites, the viscosity clearly decreases monotonically with increasing arm lengths as summarized in Fig. 4a–for simulations and b–for experiments). Literature on the role of the shape of the nanoparticles on the viscoelastic behavior of polymer nanocomposites is scarce15,33,34,35. The existing studies reveal that NP inclusions often enhance the viscosity. These results nicely corroborate our results on SN-based and NR-based composites. However, to the best of our knowledge, shape-induced reduction in the viscosity, the case of our TP-based composites, of polymer melts, has not been reported. This suggests that the role of NP shape might be more complex than previously recognized in determining PNC flow properties. Further investigation into NP shape-dependent viscosity is thus crucial to gain deeper insights into this behavior.

We compute the monomer density as a function of the radial distance from the NP surface. The monomer density profile ρNP-m(r) is shown in Fig. 5a. The height of the first peak in ρNP-m(r) is significantly lower for the TP surface in comparison with SN- and NR-based composites. This suggests that the local polymer density around a TP is the lowest among the three composite systems studied here. Further, we compute the monomer-monomer pair-correlation function, as shown in Fig 5b. The correlation is strongest in SN-based composites, while it is comparatively weaker in TP4 and NR4-based composites, with TP4 exhibiting a slightly lower correlation than NR4. This suggests that the polymer packing in the PNC becomes weaker with the presence of anisotropic NPs, particularly TPs. To understand it better, we compute monomer density as a function of the radial distance from the center of a TP in Fig. 5c. It shows that the first peak of ρTP-m shifts to the right as TP arm length increases, implying greater inaccessible space near the TP center. Thus, we infer that packing inefficiencies of anisotropic NPs in an entangled polymer melt reduce the overall packing fraction, which contributes to the lower viscosity in NR-polymer composites, especially with longer NRs. When four NRs are connected at a single junction, as in TPs, the packing frustration increases due to an additional inaccessible volume at the TP core, resulting in the greatest viscosity reduction (Fig. 4a).

a Monomer density profiles from the surface of a NP for SN, NR4 and TP4 filled PNCs. b Monomer-monomer pair-correlation function for SN, NR4, and TP4 filled PNCs. c Monomer density profiles from the center of a TP for varying arm lengths. d Viscosity ratio (\(\frac{\eta }{{\eta }_{0}}\)) calculated from melt rheology experiments (open triangles), dewetting experiments (closed diamonds) and MD simulations (closed hexagons) as a function of normalized inaccessible volume (V *). All green symbols denotes TP5, all pink symbols denotes TP11 and all blue symbols denotes TP14. All black hexagons are results extracted from MD simulations. The black dotted line denotes viscosity ratio \(\frac{\eta }{{\eta }_{0}}\) = 1. The black solid line indicates a scaling of \(\frac{\eta }{{\eta }_{0}} \sim {({V}^{*})}^{-0.2}\). The error bars in the figure represent the standard deviation of the data.

Due to their tetrahedral structure, TPs feature highly confined spaces with a size d that decreases progressively toward the core. If the length scale d of these confined regions is comparable to or smaller than the size of the polymer chains, Rg, the chains must stretch to access these spaces. The stretching of real chains in such confined areas follows a scaling of \(\sim {d}^{-\frac{2}{3}}\), while the associated increase in confinement energy scales as \(\sim {d}^{-\frac{5}{3}}\)36. To minimize the energy penalty from confinement, the polymer chains tend to remain in the less confined regions of the TP. Our system can be qualitatively compared to the model proposed by Napolitano and coworkers37, where a film supported on a rough substrate is considered as a membrane freely suspended on pillars of uniform height distributed randomly across a flat surface. An increase in substrate roughness corresponds to a lower pillar density, which results in a larger freestanding surface area per unit, thereby explaining the enhanced dynamics of polymer films on rough substrates.

In addition, given the rapid timescales associated with spin coating or melt rheometry preparation, the polymer chains can adopt conformations with reduced packing around the TPs on a length scale (d) within TPs. To capture the presence of such a geometrical effect, we extracted the normalized free inaccessible volume (V *) within the envelope volume of TP i.e., V * = Vinaccessible/Vg. Here, \({V}_{{{{\rm{g}}}}}={R}_{{{{\rm{g}}}}}^{3}\) is the envelope volume of the polymers. More details of the V * calculations can be seen in SI. Interestingly, for all the TPs used in our study, Vinaccessible < < Vg. Thus, we believe that Vinaccessible sets the scale for the inaccessible volumes within a TP. The presence of such inaccessible volumes may allow us to understand the reduced viscosity in TP-based composites. To explicitly capture this aspect, we plot the viscosity ratio \(\frac{\eta }{{\eta }_{0}}\) against V * in Fig. 5d. All our results, thin film and bulk experiments, and CGMD simulations, nicely overlap to yield a scaling relation between the reduction in viscosity and the normalized inaccessible volume within the system: \((\frac{\eta }{{\eta }_{0}}) \sim {({V}^{*})}^{-0.2}\). This overlap of all the data demonstrates that the confinement-induced packing frustration around the TP underlies the observed decrease in the viscosity of TP-based composites. Clearly, SN- and NR-based composites do not possess such restrictive spaces.

To provide additional evidence supporting our claims, we calculate the TP-polymer viscosity in the limiting case where the polymer chain length is N = 1. This effectively corresponds to a system of TPs in an LJ liquid (Fig. S23 in SI), representing a non-polymeric base matrix. In this case, we find that the normalized viscosity \(\frac{\eta }{{\eta }_{0}}\) is ~1.0, compared to a significantly lower value of 0.15 for the polymer matrix (chain length is N = 110). This stark contrast indicates that the substantial reduction in viscosity is primarily due to the polymeric nature of the base matrix, which undergoes packing frustration near TPs. A control simulation with varying particle-polymer interaction softness shows a similar viscosity trend (Fig. S24 in SI), suggesting the effect is robust and persists even under weakly attractive conditions.

TPs can be intuitively compared to star polymers, which have a branched structure with multiple polymer arms extending from a central core, resulting in unique shape-dependent properties. However, TP-polymer composites differ significantly from star polymer-linear polymer composites. While star polymers are flexible and can interpenetrate the matrix based on chain length and stiffness, rigid TPs interact differently. Castro Rubio et al. observed viscosity enhancement with stiff star polymers in short-chain (below the entanglement length) linear polymer matrices, emphasizing the role of matrix chain length38. Consistent with this, our data show no viscosity reduction when TPs are loaded in an LJ fluid (Fig. S23), and suppressed dewetting (Fig. S25) in a TPs-loaded PS film with a molecular weight (9 kDa) far below the entanglement molecular weight. This suggests that only longer polymer chains lead to packing frustration around TPs, resulting in viscosity reduction. This highlights the critical impact of polymer molecular weight, a factor we will explore in future studies.

Nanotechnology continues to revolutionize materials science, offering new possibilities for manipulating the physical properties of materials at the molecular level. In recent years, the integration of nanoparticles into polymers has drawn considerable attention due to their unique impact on fluid dynamics and polymeric properties. Here, using thin film dewetting dynamics, conventional rheological studies and MD simulations, we demonstrate that a small fraction of nanotetrapods can significantly enhance polymer flow. We show that the nanotetrapods, though having a favorable interaction with the matrix polymers, create confined spaces that are entropically restrictive for the large polymeric molecules. The absence of viscosity reduction in LJ fluids and in PS, where the chain length is well below the entanglement molecular weight, upon the addition of nanotetrapods, further indicates that the polymer chain length is a key factor in governing the viscosity of PNCs. We anticipate that our results on nanotetrapod polymer composites are scalable and thus have potential applications at the industrial level, where controlling the flow of ultra-high molecular weight polymers is crucial.

Methods

Materials

Cadmium oxide (CdO, 99.5%), oleic acid (OA, 90%), 1-octadecene (ODE, 90%), trioctylphosphine (TOP, 97%), cetyltrimethylammonium bromide (CTAB, 99.9%), selenium (Se, 99.5%), tetradecylphosphonic acid (TDPA, 97%), trioctylphosphine oxide (TOPO, 97%), hexylphosphonic acid (HPA, 95%), tributylphosphine (TBP, 97%), oleylamine (>98%) from Sigma-Aldrich, toluene (99.5%, spectrophotometric grade), dimethyl cadmium (98%) and 2-propanol (HPLC grade) from Merck were used as received. Polystyrene (Mw = 1250 kDa, PDI = 1.35) was procured from Polymer Source, Canada.

Sample preparation

Synthesis of CdSe SN

Colloidal CdSe SN were synthesized using a modified procedure by combining cadmium oxide (0.64 mmol), TDPA (1.28 mmol), TOPO (4.2 mmol), and oleylamine (5 mL) in a three-neck round-bottom flask39. The reaction mixture was heated to 100 °C, followed by a nitrogen purge for 10 minutes and a subsequent vacuum applied for 30 minutes, all while maintaining continuous stirring. This cycle was repeated three times to ensure the removal of moisture and oxygen. The temperature was then increased to 320 °C, resulting in the formation of a colorless solution. After reducing the temperature of the reaction mixture to 270 °C, 4 ml of a 0.2 M TOP-Se solution was swiftly injected. The preparation of the TOP-Se solution was carried out within a nitrogen-filled glove box. The reaction was sustained for ~10 minutes. Subsequently, the reaction mixture was cooled to 90 °C, and 10 ml of toluene was added to prevent solidification. To precipitate the nanoparticles, ethanol was used, followed by centrifugation at 4116 × g for 10 minutes. This washing process was applied 2–3 times to eliminate unreacted precursors. The final CdSe nanoparticle precipitate was re-dispersed in toluene for subsequent measurements. Particle size of SN as well as the thickness of the stabilization layer was calculated using transmission electron microscopy (TEM) and dynamic light scattering (DLS), which can be found in detail in Figs. S3, S6, S9, and S11 of SI.

Synthesis of CdSe NR

A three-neck round-bottom flask was taken and a mixture of HPA, TDPA and TOPO was added, and the mixture was heated to 360 °C40. \({{{\rm{Cd}}}}{({{{{\rm{CH}}}}}_{3})}_{2}\)/ TBP solution was added to the mixture dropwise followed by a quick injection of Se/TBP solution. The resulting solution was kept at 300 °C for growth. Aliquots are taken out of the reaction mixture and purified by precipitation in ethanol followed by centrifuging at 4116 × g. The pure product is re-dispersed into toluene. Dimensions (length and diameter) of NR as well as thickness of stabilization layer was calculated using TEM and DLS which can be found in details in Figs. S4, S7, S10 and S11 of SI.

Synthesis of CdSe nanotetrapods (TP)

In a 100 ml three-neck round-bottom flask, CdO (1 mmol), oleic acid (6.28 mmol), and octadecene (ODE, 20 ml) were used as the Cd precursor41. The flasks were connected to a condenser, connected to a Schlenk line that connected an inert nitrogen cylinder and a vacuum pump on both ends. Another neck was used to insert a temperature sensor, while the third was sealed with a septum for withdrawing samples using a microsyringe. The reaction mixture was gradually heated under an inert atmosphere, ensuring continuous nitrogen purging through the Schlenk line. To maintain controlled conditions, the alternation between nitrogen purging and evacuation was performed while continuously stirring at 100 °C. This cycle was repeated three times to completely eliminate moisture and oxygen from the mixture. The temperature was then slowly raised to 240-250 °C, resulting in the brown mixture turning clear and colorless, forming a stable Cd-oleate precursor solution. For the Se precursor, 0.5 mmol of Se was mixed with 1.5 ml of TOP within a nitrogen-filled glove box. A solution of TOP-Se premixed with CTAB (0.02 g in 3 ml of toluene) was swiftly injected into the reaction mixture in the round-bottom flask at 190 ∘C using a glass syringe with a stainless-steel needle through a septum. To grow CdSe nanotetrapods, the reaction temperature was maintained at 160 °C. Samples were collected periodically to monitor the formation of the nanotetrapods. A schematic of the entire process is added in Fig. S1 of SI. The CdSe nanotetrapods were purified by precipitation using 2-propanol (1:3) to remove excess unreacted precursors, followed by centrifugation at 4116 × g at 4 °C. The final product was dried at room temperature and re-dispersed in toluene. Dimensions (arm length and arm width) of TP as well as thickness of stabilization layer were calculated using TEM and DLS, which can be found in details in Figs. S2, S5, S8 and S11 of SI.

Preparation of PNC thin films

PS/PNC thin films were spin-coated at 67 × g (2000 rpm) using a PS solution in toluene. Before spin-coating PS/PS-NP solution, Si (100) substrates were already covered with a thin irreversibly adsorbed slippery layer of hydroxy-terminated polydimethylsiloxane (layer thickness ca. 10 nm). Such a layer represents an ideally homogeneous surface of low surface tension and rather low interfacial friction for the dewetting of PS/PNC thin films. PS/PNC thin film thickness used in our experiments was 207 ± 1 nm as measured by atomic force microscope.

Dewetting experiments

Evolution of dewetting holes in PS/PNC thin films was followed in situ using an optical microscope (OLYMPUS BX53M) attached to a digital charge-coupled device (CCD) camera (DP 27) on a heating stage setup (Linkam THMS-600). The temperature of the dewetting experiments was always 200 °C. Circular holes were formed in the films which grew with time18,19,21. A time series of images were taken at regular intervals to follow the temporal growth of dewetted holes nucleated in the films.

Rheology experiments

Rheological measurements of bulk polymer thin slabs (sample thickness ca. 500 μm) and bulk PNC thin slabs (sample thickness ca. 500 μm) were done on a stress-controlled Rheometer (MCR 702, Anton Paar) in oscillatory shear mode. The tests were done on a parallel-plate geometry with a 50 mm diameter plate (PP50) at the bottom and an 8 mm diameter plate (PP08) at the top. Temperature control was achieved by using a CTD 600 convection oven. All measurements were done at 200 °C, unless otherwise specified. The gap was adjusted according to the sample thickness. An amplitude sweep was performed to determine the linear viscoelastic limit (LVE). A strain value within the LVE region was taken, and a frequency sweep was performed from (100–0.01) rad/s to measure the complex viscosity. The samples were held at 200 °C for 10 min before conducting the experiments to ensure equilibration of temperature.

Molecular dynamics simulations

A pair of non-bonded monomers interacts via the LJ potential of the form \(V(r)=4\epsilon \left[{\left(\frac{\sigma }{r}\right)}^{12}-{\left(\frac{\sigma }{r}\right)}^{6}\right]\) with a cut-off distance rc = 2.5σ. Here, ϵ is the unit of pair interaction energy, and σ is the size of a monomer. Two adjacent monomers of a polymer chain are connected by the finitely extensible non-linear elastic (FENE) potential of the form \(E=-\frac{1}{2}K{R}_{0}^{2}\ln \left[1-{\left(\frac{r}{{R}_{0}}\right)}^{2}\right]+4\epsilon \left[{\left(\frac{\sigma }{r}\right)}^{12}-{\left(\frac{\sigma }{r}\right)}^{6}\right]+\epsilon\), where \(K=\frac{30\epsilon }{{\sigma }^{2}}\) and R0 = 1.5σ is the maximum bond extension in the FENE potential. The 2nd term in E is truncated at a distance r = 21/6σ. Each chain consists of 110 monomer units. NPs are also modeled using the LJ potential. The spherical NP is modeled as an LJ particle of diameter 1σ. A nanorod is modeled as a rigid body made of a few LJ particles, each of size 1σ. They are placed in a straight line with an interparticle spacing of 1σ. Four such rods are catenated at a point to construct a tetrapod model. Schematic representations of NP models are shown in the SI. During a simulation, all the beads of an NP move as a rigid body42. The interaction between the beads of different NPs is truncated at a distance rc = 21/6σ to represent repulsion between them. The polymer-NP interaction is considered to be attractive to model the adsorbing polymers, and the interaction strength between polymer-NP is taken as ϵNP = 2.0. We note that small spherical NPs with the same interaction as between monomers can act as a solvent and reduce viscosity5. Therefore, we chose a stronger NP-polymer interaction to model the experimental trend for the SN-polymer composite. The polymer-NP interaction is truncated at a cut-off distance rc = 2.5σ. All LJ interactions are shifted to zero at their respective cut-off distances. The numbers of polymer chains and NPs are varied in the simulation box to maintain a constant NP mass fraction across all the systems. A total of 10 systems are simulated with varied compositions as tabulated in Table S2 of the SI. We use the velocity-Verlet algorithm with a timestep of 0.005τ to integrate the equations of motion. Here, \(\tau=\sigma \sqrt{\frac{m}{\epsilon }}\) is the unit of time, and m is the mass of a monomer. The simulations are conducted in an isothermal-isobaric ensemble (NPT) at a reduced temperature \({T}^{*}=\frac{{k}_{B}T}{\epsilon }=1.0\) and pressure \({P}^{*}=\frac{{\sigma }^{3}}{\epsilon }=1.0\). The temperature and pressure are maintained using a Nosé-Hoover thermostat and barostat, respectively. MD simulations are carried out for 3 × 107 MD steps for equilibrating the system. An equilibration run is followed by a production run of 2 × 107 MD steps. All properties are calculated from the production trajectory. The chain end-to-end vector relaxation time is about 1000τ, which can be seen in the SI. Thus, our simulations are long enough to capture the equilibrium properties of the system.

Furthermore, the equilibrated structures are used for NEMD simulations, in which SLLOD43,44 equations of motion are solved in a canonical ensemble (NVT) at a reduced temperature T * = 1.0. In NEMD simulations, a shear is applied to the simulation box in the xy plane with a constant rate. All NEMD simulations are performed for 3 × 107 steps, followed by a production run of additional 2 × 107 steps. The shear stress is computed from a production trajectory, which can be written as \({\sigma }_{xy}=\frac{1}{V}\mathop{\sum }_{k=1}^{M}{m}_{k}{v}_{kx}{v}_{ky}+\frac{1}{V}\mathop{\sum }_{k=1}^{M}{r}_{kx}{F}_{ky}\). Here, V is the volume of the system. The rkx is the x-component of kth particle’s position co-ordinate; and Fky is the y–component of the kth particle’s force. The total number of particles in the system is M. The vkx and vky are th the x- and y- components of the velocity of the kth particle, respectively. The shear viscosity (η) is calculated as \(\eta=-{\sigma }_{xy}/\dot{\gamma }\). We vary the shear rate from \(\dot{\gamma }=1{0}^{-5}\) to \(\dot{\gamma }=1{0}^{-1}\). In our simulations, η becomes nearly constant around the lowest shear rate \(\dot{\gamma }=1{0}^{-5}\), as shown in the SI. This indicates that the system approaches the Newtonian regime in our simulations when \(\dot{\gamma }=1{0}^{-5}\)44. All the simulations are performed using the large atomic/molecular massively parallel simulator (LAMMPS) MD simulation package45.

Moreover, we repeat the simulations with weaker interactions to examine how the choice of interaction parameters in the model affects our conclusions. The corresponding results are provided in SI. We also perform simulations with polymer chain length N=1, as reported in the SI, to reinforce our claim that viscosity reduction is only possible for high-molecular-weight polymers. In this study, we employ the canonical bead-spring model for polymers46. We use the LJ potential to model the monomers and beads of NPs, which corresponds to an effective diameter of ~5 nm. At this coarse-grained level, each monomer represents several Kuhn segments of the experimental system. This can result in a softer effective interaction between a pair of particles than the one used in this study. This reflects a typical trade-off in coarse-grained simulations. The computational efficiency is gained at the expense of some structural resolution. This approach aims to capture the essential mesoscale physics while recognizing that the resulting pairwise interactions are likely softer than those between individual particles47,48,49. Although the softness of the model may slightly affect local packing and entanglement, we believe that it sufficiently captures the key physics relevant to the phenomenon under investigation.

Data availability

The data that supports the findings of this study are included in the paper and SI. The source data of all the figures are available in the Source Data file, which is available with this paper. All data are available from the corresponding author upon request. Source data are provided with this paper.

References

Chandran, S. et al. Processing pathways decide polymer properties at the molecular level. Macromolecules 52, 7146–7156 (2019).

Dhand, A. P. et al. Additive manufacturing of highly entangled polymer networks. Science 385, 566–572 (2024).

Kumar, S. K., Benicewicz, B. C., Vaia, R. A. & Winey, K. I. 50th anniversary perspective: Are polymer nanocomposites practical for applications? Macromolecules 50, 714–731 (2017).

Huang, J. et al. Full-scale polymer relaxation induced by single-chain confinement enhances mechanical stability of nanocomposites. Nat. Commun. 15, 6747 (2024).

Kalathi, J. T., Grest, G. S. & Kumar, S. K. Universal viscosity behavior of polymer nanocomposites. Phys. Rev. Lett. 109, 198301 (2012).

Drakopoulos, S. X. et al. Polymer nanocomposites: interfacial properties and capacitive energy storage. Prog. Polym. Sci. 156, 101870 (2024).

Bailey, E. J. & Winey, K. I. Dynamics of polymer segments, polymer chains, and nanoparticles in polymer nanocomposite melts: a review. Prog. Polym. Sci. 105, 101242 (2020).

Swain, A., Anthuparambil, N. D., Begam, N., Chandran, S. & Basu, J. Harnessing interfacial entropic effects in polymer grafted nanoparticle composites for tailoring their thermo-mechanical and separation properties. Soft Matter 21, 3443–3472 (2025).

Kumar, S.K., Ganesan, V. & Riggleman, R.A. Perspective: outstanding theoretical questions in polymer-nanoparticle hybrids. J. Chem. Phys. 147, 020901 (2017).

Sunday, D., Ilavsky, J. & Green, D. L. A phase diagram for polymer-grafted nanoparticles in homopolymer matrices. Macromolecules 45, 4007–4011 (2012).

Koh, C., Grest, G. S. & Kumar, S. K. Assembly of polymer-grafted nanoparticles in polymer matrices. ACS Nano 14, 13491–13499 (2020).

Mangal, R., Srivastava, S. & Archer, L. A. Phase stability and dynamics of entangled polymer–nanoparticle composites. Nat. Commun. 6, 7198 (2015).

Midya, J., Rubinstein, M., Kumar, S. K. & Nikoubashman, A. Structure of polymer-grafted nanoparticle melts. ACS Nano 14, 15505–15516 (2020).

Arno, M. C. et al. Exploiting the role of nanoparticle shape in enhancing hydrogel adhesive and mechanical properties. Nat. Commun. 11, 1420 (2020).

Knauert, S. T., Douglas, J. F. & Starr, F. W. The effect of nanoparticle shape on polymer-nanocomposite rheology and tensile strength. J. Polym. Sci. Part B: Polym. Phys. 45, 1882–1897 (2007).

Danel, P. Tetrapods. Coast. Eng. (4), 28–28 (1953).

Chandran, S. & Reiter, G. Transient cooperative processes in dewetting polymer melts. Phys. Rev. Lett. 116, 088301 (2016).

Reiter, G. et al. Residual stresses in thin polymer films cause rupture and dominate early stages of dewetting. Nat. Mater. 4, 754–758 (2005).

Madhusudanan, M., Sarkar, J., Dhar, S. & Chowdhury, M. Tuning the plasticization to decouple the effect of molecular recoiling stress from modulus and viscosity in dewetting thin polystyrene films. Macromolecules 56, 1402–1409 (2023).

Chandran, S. et al. Time allowed for equilibration quantifies the preparation induced nonequilibrium behavior of polymer films. ACS Macro Lett. 6, 1296–1300 (2017).

Chowdhury, M., Al Akhrass, S., Ziebert, F. & Reiter, G. Relaxing nonequilibrated polymers in thin films at temperatures slightly above the glass transition. J. Polym. Sci. Part B: Polym. Phys. 55, 515–523 (2017).

Madhusudanan, M. & Chowdhury, M. Relaxation and entropy generation in dewetting thin glassy polymer films trapped far from equilibrium. J. Polym. Sci. 62, 5052–5076 (2024).

Madhusudanan, M. & Chowdhury, M. Advancements in novel mechano-rheological probes for studying glassy dynamics in nanoconfined thin polymer films. ACS Polym. Au 4, 342–391 (2024).

Tuteja, A., Mackay, M. E., Narayanan, S., Asokan, S. & Wong, M. S. Breakdown of the continuum stokes- einstein relation for nanoparticle diffusion. Nano Lett. 7, 1276–1281 (2007).

Kwag, C., Manke, C. & Gulari, E. Rheology of molten polystyrene with dissolved supercritical and near-critical gases. J. Polym. Sci. Part B: Polym. Phys. 37, 2771–2781 (1999).

Redon, C., Brzoska, J. & Brochard-Wyart, F. Dewetting and slippage of microscopic polymer films. Macromolecules 27, 468–471 (1994).

Brochard-Wyart, F., De Gennes, P.-G., Hervert, H. & Redon, C. Wetting and slippage of polymer melts on semi-ideal surfaces. Langmuir 10, 1566–1572 (1994).

Reiter, G. & Khanna, R. Kinetics of autophobic dewetting of polymer films. Langmuir 16, 6351–6357 (2000).

Vilmin, T. & Raphaël, E. Dewetting of thin polymer films. Eur. Phys. J. E 21, 161–174 (2006).

Bäumchen, O., Fetzer, R. & Jacobs, K. Reduced interfacial entanglement density affects the boundary conditions of polymer flow. Phys. Rev. Lett. 103, 247801 (2009).

Kremer, K. & Grest, G. S. Dynamics of entangled linear polymer melts: a molecular-dynamics simulation. J. Chem. Phys. 92, 5057–5086 (1990).

Krishnan, R. et al. Improved polymer thin-film wetting behavior through nanoparticle segregation to interfaces. J. Phys. Condens. Matter 19, 356003 (2007).

Li, Y., Kröger, M. & Liu, W. K. Nanoparticle geometrical effect on structure, dynamics and anisotropic viscosity of polyethylene nanocomposites. Macromolecules 45, 2099–2112 (2012).

Petersen, M. K., Lane, J. M. D. & Grest, G. S. Shear rheology of extended nanoparticles. Phys. Rev. E—Stat. Nonlin. Soft Matter Phys. 82, 010201 (2010).

Heine, D.R., Petersen, M.K. & Grest, G.S. Effect of particle shape and charge on bulk rheology of nanoparticle suspensions. J. Chem. Phys. 132, 184509 (2010).

De Gennes, P.-G. Scaling Concepts in Polymer Physics. (Cornell University Press, London, 1979).

Panagopoulou, A., Rodríguez-Tinoco, C., White, R. P., Lipson, J. E. & Napolitano, S. Substrate roughness speeds up segmental dynamics of thin polymer films. Phys. Rev. Lett. 124, 027802 (2020).

Castro Rubio, C. A., Fan, J., Hanrahan, M. K., Douglas, J. F. & Starr, F. W. Structure and dynamics of composites of star polymers in a linear polymer matrix. Macromolecules 56, 9324–9335 (2023).

Gopal, M. B. Ag and Cu doped colloidal CdSe nanocrystals: partial cation exchange and luminescence. Mater. Res. Express 2, 085004 (2015).

Hu, J. et al. Linearly polarized emission from colloidal semiconductor quantum rods. Science 292, 2060–2063 (2001).

Banerjee, S., Maddala, B. G., Ali, F. & Datta, A. Enhancement of the band edge emission of cdse nano-tetrapods by suppression of surface trapping. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 21, 9512–9519 (2019).

Miller Iii, T. et al. Symplectic quaternion scheme for biophysical molecular dynamics. J. Chem. Phys. 116, 8649–8659 (2002).

Evans, D. J. & Morriss, G. Nonlinear-response theory for steady planar couette flow. Phys. Rev. A 30, 1528 (1984).

Sundaravadivelu Devarajan, D. et al. Sequence-dependent material properties of biomolecular condensates and their relation to dilute phase conformations. Nat. Commun. 15, 1912 (2024).

Thompson, A. P. et al. Lammps-a flexible simulation tool for particle-based materials modeling at the atomic, meso, and continuum scales. Comput. Phys. Commun. 271, 108171 (2022).

Everaers, R., Karimi-Varzaneh, H. A., Fleck, F., Hojdis, N. & Svaneborg, C. Kremer–grest models for commodity polymer melts: linking theory, experiment, and simulation at the kuhn scale. Macromolecules 53, 1901–1916 (2020).

Louis, A., Bolhuis, P., Hansen, J. & Meijer, E. Can polymer coils be modeled as “soft colloids”? Phys. Rev. Lett. 85, 2522 (2000).

Likos, C. N. Effective interactions in soft condensed matter physics. Phys. Rep. 348, 267–439 (2001).

Bolhuis, P. & Louis, A. How to derive and parameterize effective potentials in colloid- polymer mixtures. Macromolecules 35, 1860–1869 (2002).

Stukowski, A. Visualization and analysis of atomistic simulation data with ovito–the open visualization tool. Model. Simul. Mater. Sci. Eng. 18, 015012 (2009).

Acknowledgements

We thank Sanat Kumar (Columbia University), Haimanti Mukherjee, and Rohit V. Menon (IIT Bombay) for many insightful discussions. M.C. acknowledges support from the Anusandhan National Research Foundation (ANRF; formerly SERB) through the Ramanujan Fellowship (SB/S2/RJN-084/2018), and the Early Career Research Award (ECR/2018/001740). Additional support from IIT Bombay was acknowledged through SEED (RD/0519-IRCCSH0-033) and IOE-SCPP (RD/0523-IOE00I0-193) grants. S.C. acknowledges the funding from the Startup Research Grant (SRG/2021/001276) from the ANRF and the Kotak Sustainable School, IITK. A.D. is grateful to ANRF for a generous research grant. We also thank IIT Bombay for access to several central facilities, Advanced Rheology Facility, Bio Atomic Force Microscopy Facility, and the MEMS TEM-300 kV Facility.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

J.S. performed most of the experiments, S.M.B.G. performed MD simulations, F.A. did the synthesis of nanoparticles under the supervision of A.D., H.Y. did bulk rheometry experiments, J.S., M.M., and S.M.B.G. carried out data analysis, J.S., S.M.B.G., M.M., T.K.P., S.C., and M.C. wrote the manuscript. M.C. conceived the research idea. T.K.P., S.C., and M.C. supervised the project’s progress. All the authors participated in discussions about the results and agreed on the content of the manuscript.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Peer review

Peer review information

Nature Communications thanks Arash Nikoubashman and the other, anonymous, reviewers for their contribution to the peer review of this work. A peer review file is available.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Source data

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Sarkar, J., Gautham, S.M.B., Ali, F. et al. Nanotetrapods promote polymer flow through confinement induced packing frustration. Nat Commun 16, 8550 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-025-63555-3

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-025-63555-3