Abstract

Chiral vortex beams with tunable topological charges (TCs) hold promise for high-capacity and multi-channel information transmission. However, asymmetric vortex transport, a crucial feature for enhancing robustness and security, often disrupts channel independence by altering TCs, causing signal distortion. Here, we exploit the radial mode degree of freedom in chiral space to achieve extremely asymmetric transmission with high energy contrast, while preserving chirality and TCs. This is enabled by radial mode modulation, induced by one-way momentum from an invasive metamaterial, resulting in full vortex transmission in one direction and complete isolation in the opposite. We further realize high-contrast asymmetric image transport by encoding information into different TC channels. Notably, this approach sustains near noise-immune performance at signal-to-noise ratios as low as -25 dB, owing to TC preservation and the orthogonality of vortices with differing TCs. Our findings present a new strategy for chiral beam control and pave the way for secure, directional, and noise-resilient information transport in structured wave platforms.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Asymmetric wave transmission has been a key driver in enhancing the security and robustness of high-performance transmission systems1,2,3,4. Achieving asymmetric transmission often requires breaking spatial or temporal symmetry5,6. Over the past decade, breaking spatiotemporal inversion symmetry has facilitated one-way propagation of optical and acoustic waves through various mechanisms, including external magnetic fields1,7, biased background flow fields8,9,10, nonlinear effects4,11,12,13,14, and active spatio-temporal modulations15,16,17,18. On the other hand, broken spatial symmetry and non-Hermitian physics provide a different approach, giving rise to intriguing phenomena such as unidirectional transparency19,20,21, unidirectional absorption22,23, and unidirectional focusing24. However, these studies have primarily focused on manipulating relatively simple plane waves. Given that structured waves inherently carry richer information due to the higher degree of freedom of their wavefronts, asymmetric structured wave transmission has attracted growing interest.

Vortex beams, as a representative class of structured waves, are characterized by a helical phase wavefront and are capable of carrying orbital angular momentum (OAM). In idealized cases—such as a single, stable vortex beam with a centered phase singularity and circularly symmetric amplitude, the carried OAM is proportional to its topological charge (TC)25,26, so that the beam’s chirality can be determined by the sign of the TC. Since the TC is defined as a quantized phase winding number around the singularity, it remains invariant under continuous perturbations as long as the singularity is not annihilated or merged, which in turn ensures the preservation of chirality. It is precisely because of this unique phase and intensity distribution that vortex beams have been widely studied in optics27, acoustics28, and electromagnetism29. These properties have enabled diverse applications such as optical or acoustic tweezers30,31, imaging32,33, and high-capacity communications34,35,36. Notably, manipulating the chirality of vortex beams has emerged as a promising route for achieving asymmetric transport. Existing methods such as gradient-phase modulations (GPMs)37,38, bound states in the continuum (BICs)39, and non-Hermitian exceptional points (EPs)40 have demonstrated unidirectional vortex propagation. However, these methods often introduce external azimuthal momentum via structure angular modulation, which can induce undesired mode coupling between different TC states and distort the output beam’s chirality. This mode mixing complicates the separation of signals encoded in distinct TC channels, increases crosstalk, and degrades communication reliability. Although recent efforts36 have demonstrated real-time acoustic communication with high channel capacity through multiplexed vortex beams, the approach relies on symmetric transmission paths and does not address directional selectivity or chiral preservation. These limitations highlight the need for a new framework that enables asymmetric vortex transmission while preserving both TC and chirality.

In this work, we harness the previously unexplored radial mode as a hidden modal dimension to achieve asymmetric transmission with chirality and TC protection. By introducing an axially modulated non-invasive acoustic metamaterial, we drive the unidirectional evolution of the radial mode, thus achieving perfect vortex transmission exclusively in the forward direction, without altering the chirality and TC. In contrast, backward transmission of vortex is inhibited owing to the divergence of momentum driven by such radial mode evolution, leading to the transition of the system from a transport state to an isolation state. By encoding image information into distinct TC channels, we further utilize such extreme asymmetric vortex transmission to achieve high-contrast one-way image transport. Crucially, we find that the combination of mode orthogonality and chirality protection across different TC states provides strong immunity against external interference during image transmission, as non-target components in the noise are converted into evanescent waves and effectively filtered out. This allows us to experimentally achieve image transport with a signal-to-noise ratio (SNR) as low as -25 dB. Our work offers a generally applicable strategy for chiral beam manipulation and lays a foundation for secure, unidirectional, and noise-resilient information transport across a broad class of structured wave.

Results

Principle of asymmetric transmission with chiral protection

Vortex beams, which act as eigenfunctions of the angular momentum operator41, represent the eigenfields in acoustic circular waveguides, which is expressed as

where Am,n is the complex amplitude of each mode, Jm is the m-th order Bessel function of the first kind that describes the field distribution in radial direction. \({k}_{m,n}^{z}\) and \({k}_{m,n}^{r}\) are the axial and radial wavenumber, respectively. They are related by the equation

where k0 is the wavenumber of the incident wave and \({k}_{m,n}^{r}\) depends on the acoustic properties of the duct radius and its wall boundary conditions. The unique spiral phase wavefront of a vortex beam is determined by two key parameters: the TC number (m) and the radial mode order (n). Note that the TC number, m, is crucial because it carries chiral information that can be encoded for signal transport42, while the radial mode order n, a non-negative integer corresponding to the n-th extremum of the Bessel function, is associated with sidelobe effects and often regarded as interference with m43. Since vortex beams are characterized by the angular phase gradient of their wavefront that relates to m, manipulating vortex beams using structures such as metamaterials with angular modulations is common44,45. However, these methods often alter m, thereby disrupting chirality, mixing communication channels associated with different TCs and increasing the bit error rate.

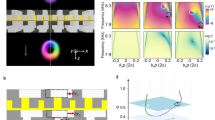

Here, we conceptually show that a perfect rotational symmetry metamaterial modulated in the axial direction facilitates extreme asymmetric control of vortex beams with chiral and TC protection in circular waveguides. Specifically, the axial arrangement of the metamaterial, by introducing an external wave vector Δk in the axial direction, allows the incident wave to evolve along propagation. Δk modulates the axial wavenumber \({k}_{m,n}^{z}\) in a unique way for asymmetric chiral-protected vortex transmission (Fig. 1a, b). Without loss of generality, we consider an incident vortex with TC m and radial mode order 0. When the vortex enters from the forward direction, Δk induced by the metamaterial decreases the axial wavenumber \({k}_{m,0}^{z}\), which causes a corresponding change in \({k}_{m,n}^{r}\), as their squared sum must equal k0 according to momentum conservation (Eq. (2)). In this case, the transmitted vortex remains within the propagable region, which is a semicircle with a diameter of k0 (Eq. (2)). Crucially, during this process, the TC carried by the vortex is preserved because the axially symmetric metamaterial does not introduce a external vector in the azimuthal angle direction that would drive transitions between different TC modes. As a result, the incident radial wavenumber \({k}_{m,0}^{r}\) shifts to the transmitted one \({k}_{m,n}^{r}\), where the m remains unchanged while the radial mode order changes from 0 to n (see the transition from point A to point B in Fig. 1c). Such a TC-preserved transmission is essential for maintaining information transport in the same TC channel.

a Perfect transmission of vortex beams encoding information under positive incidence. The metamaterial imparts an external wave vector Δk (indicated by the blue arrow) to drive the radial mode evolution. This evolution protects the chirality and TC of the vortex beams so that information encoded in different TC channels can be transmitted efficiently without crosstalk. b The transmission of same vortex beams in reversed direction is completely inhibited. c Modulation of wavevector during vortex transmission in the forward direction. When the direction of incidence opposes the direction of the Δk provided by the metamaterial, Δk induces a change in \({k}_{m,n}^{z}\) and causes \({k}_{mn}^{r}\) to match, resulting in the evolution of a vortex beam from mode (m, 0) to mode (m, 1), with the TC m preserved. d When the incident direction is reversed, Δk causes \({k}_{m,n}^{z}\) to increase, resulting in \({k}_{m,n}^{z}\) exceeding the k0. The transmitted vortex transitions from a propagating state to an evanescent state, causing the system to turn into isolation.

Conversely, when the direction of incidence is reversed, the external wave vector is aligned with the direction of \({k}_{m,0}^{z}\) thus increasing its magnitude to exceed the semicircle of diameter k0 (Fig. 1d). As no corresponding \({k}_{m,n}^{r}\) exists and the phase velocity of the chiral beam cp is less than the sound velocity c0, the vortex turns from a transmission state to the evanescent state, entering the isolation plane (see Fig. 1d, transition from point A to point C). As a result, chiral beam propagation is not permitted, and the conservation of energy ensures that the incident beam is fully reflected (see details in Supplementary Note 1).

Acoustic metamaterials empowered radial mode evolution with chiral protection

Achieving asymmetric transmission with chiral protection requires the tailored evolution of the radial mode driven by an external wave vector Δk. Here, this is achieved by leveraging the flexible sound manipulation capability of metamaterials. Since generating specific vortex mode can be achieved through the coherent superposition of sources at different locations (see details in Supplementary Notes 2 and 4), we replace these sources with side-branch slots of subwavelength width which act in a similar but passive way as the sources (Fig. 2a). Note that the metamaterial comprising these axially arranged side-branch slots is noninvasive, allowing high efficient barrier-free signal transport, and thus is superior to those designs with angular or radial modulations that may lead to structural obstruction in the waveguide.

a An axially symmetric metamaterial with subwavelength slots arranged along the axial direction. The circular waveguide has a diameter D, and the metamaterial thickness is L = 1.58λ (λ being the acoustic wavelength). The slots have a fixed width w = 0.22λ and varying depths hj, where h1 = 0.33λ, h2 = 1.18λ, h3 = 1.11λ, and h4 = 0.59λ in this design. The axial spacing between adjacent slots is di. Here d1 = 0.35λ, d2 = 0.22λ and d3 = 0.14λ. b, c The simulated acoustic pressure fields through the metamaterial when the vortex of mode (1,0) propagates along the forward and backward directions, respectively. d Cross-section acoustic pressure and phase distribution at the input and output cross-sections marked by the dashed circles in (b, c). The transmissive vortex retains the same chirality as the input vortex under forward propagation, while transmission is forbidden when the incident direction is reversed.

We showcase a metamaterial designed along this scheme that achieves extreme asymmetric transport for a vortex with mode (1, 0), i.e., m = 1 and n = 0, at 3225 Hz (Fig. 2). Numerical simulations indicate that, under positive incidence, the metamaterial converts the incident vortex of mode (1,0) into the transmitted one (1,1) with 100% efficiency, as shown in Fig. 2b (see simulation details in Methods). Note that the TC value is preserved (m = 1) during this process. The cross-sectional amplitude and phase distributions further confirm the chiral protection (Fig. 2d, upper and middle panels). In contrast, reversing the incidence of vortex (1, 0) leads to complete transport isolation (Fig. 2c and the lower panel of Fig. 2d).

To gain a comprehensive understanding of the mode evolution during the asymmetric vortex transmission, we present the vortex modes of each order at the transmitted side, both simulationally and experimentally, using the sound field decomposition method (see details about the decomposition method in Supplementary Note 2). The experimental setup consists of a dual-layer array of 32 independently controlled loudspeakers, precisely generating a chiral beam with the target mode (1,0) as the incidence (see Methods and Supplementary Notes 2 and 3). A four-layer microphone array is placed in the downstream of the waveguide for accurate modal decomposition of the transmitted sound (See experimental details in Methods and Supplementary Note 3). A scanning microphone, with a step size of 0.004 m, scans a region of 0.12 × 0.12 m2 to measure the field distribution in a cross-section on the transmitted side. When the vortex propagates in the forward direction, the incident state (1,0) evolves completely into the transmitted state of (1,1) (Fig. 3a, b). Conversely, when the vortex is incident from the reverse direction, the incident state (1, 0) is inhibited to pass through the metamaterial, resulting in the isolation (lower panels of Fig. 3a, b). Investigation on the variation of the system performance with frequency further reveals that the asymmetric chiral signal transport exists over a range from 3130 to 3300 Hz: the reversed vortex transmission keeps inhibited while the positive transport maintains relatively high with the energy transmitted ratio T consistently higher than 50%. At the designed frequency (i.e. 3225 Hz), T reaches 100%, accompanying by the contrast ratio σ, the ratio of T under positive and reserve incidence, being as high as 800 (Fig. 3c). The magnitude and phase distributions of the acoustic field on the transmitted side, as predicted by simulations and measured by the scanning microphone, are in good agreement (Fig. 3d). For positive incidence (the left panel of Fig. 3d), the magnitude plot indicates a radial order n = 1 for the transmitted vortex, while the phase plot further confirms the preserved TC number m = 1. For reversed incidence (the right panel of Fig. 3d), the magnitude plot shows that the transmitted sound is strongly suppressed, while the phase plot indicates an evanescent vortex (see Supplementary Note 1).

a Simulated energy flow ratio (transmittance) between transmission and incident (1,0) mode during forward (Tf) and backward (Tb) transmission. b Measured transmittance of each mode. c Simulated and measured the transmittance of mode (1,1) when mode (1,0) is incident in the forward and backward directions, The transmission contrast ratio shown in the lower panel is defined as σ = Tf/Tb. Circles: experiment. Solid line: simulation. d Simulated and measured sound field distributions on the transmitted side on the cross section at a distance z = 4λ from the metamaterial. Left and right panels indicate the forward (propagable) and backward (isolated) directions, respectively. Top row: the real part of pressure p. Bottom row: phase of the vortex.

Chiral-protected asymmetric acoustic information transmission

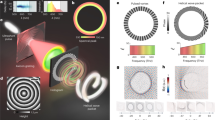

The TC-preserved asymmetric vortex transmission presented here offers a promising approach for one-way, crosstalk-free acoustic information transport, where information is encoded in vortex beams with different TCs (see coding details in Supplementary Note 5). To experimentally validate this concept, we employ the speaker and microphone arrays to excite an encoded data stream and extract the received chiral information (Fig. 4a). To generate the encoded data stream, an image is pixelated and each pixel is encoded onto a vortex beam with TC = 1 or TC = −1 via binary shift keying (Fig. 4b)36,46. Then original image can be reconstructed by decompositing the vortex modes from the extracted information at the receiving side.

a The experimental setup. A speaker array on the incident side is for generating the specific mode field, while a microphone array on the transmitted side is for characterizing the vortex mode composition. b The image “3” to be transferred is pixelized. The information is encoded by binary amplitude shift keying into a vortex with TC= ±1, where the pattern (1,0) represents white and the pattern (-1,0) represents blue. c Data flow decoded for the different radial mode at the transmission end for both forward and backward incidence of the ( ± 1,0) mode. d Image reconstruction under both forward and backward incidences.

During forward signal transport, the input, consisting of modes (1,0) and (−1,0) vortices, is transformed into a data stream composed of (1,1) and (−1,1) vortices at the receiving side (Fig. 4c). Despite the change in radial order n, the transmitted vorticies still maintain the TC value m used for information coding. To investigate the reversed transport of the image, we fix the input (the speaker array) and output (the microphone array) while reversing the metamaterial. As above demonstrated, neither of (1,0) and (−1,0) vortices can be transmitted in the reverse direction (Fig. 4d, the right panel). As a result, the data stream received under forward incidence enables perfect reconstruction of the encoded pattern, whereas no image information is detected during reverse incidence (Fig. 4d). This confirms the feasibility of incorporating radial mode dimensions into asymmetric transmission of information. Notably, this method significantly reduces mode crosstalk, thereby preserving the integrity of the information carrier throughout the transmission process. In this way, we show that the emergence of radial modes introduces a novel approach to information encryption and transmission, opening new possibilities for secure communication systems.

Chiral-protected noise-immune information transport

During information transmission, external perturbations can disrupt sound wave propagation, degrade the information carrier, and diminish system robustness. Since external noise can be represented as a superposition of different modes, information encoded on TCs will be disturbed by noise. In this work, the synergy between TC protection and TC mode orthogonality offers a promising approach to noise-immune signal transmission (see Supplementary Note 6). To prove this, we investigate the effect of the chiral-protected image transport under strong noise interference. We encode the image by using TC = ±1 vortices as the information carrier as above. These signal-carrying vorticies, together with a variety of other vortex modes with random amplitudes and random phases in the range of 1500–4500 Hz as background interference, are generated by the loudspeaker array and then fed into the system from the forward direction. We gradually increased the background noise intensity and then measured the data stream of the image detected on the receiving side at different SNRs (Fig. 5). As the noise intensity increases, the pixel resolvability at the receiving end gradually decreases, with the binary values of each pixel becoming indistinguishable (Fig. 5a). Despite increasing ambient noise, the images remain recognizable and are successfully reconstructed even at an SNR of -25 dB (Fig. 5b).

a Output signal data flow under varying signal-to-noise ratios (SNR). PXI represents the pixel intensity, defined as PXI= −T−1,1 + T1,1 (T being the transmittance). b Reconstructed image under different SNR conditions. The image to transfer is recognizable at SNR as low as −25 dB and indistinguishable at −30 dB. c Composition of vortex modes at pixels α and γ (a TC of −1 is expected), β and δ (a TC of 1 is expected) marked in images I and IV in (b). Only the chiral beam of (±1,1) is transmitted at the transmission end, while all other modes are suppressed. As SNR decreases, the intensity of the target modes (±1, 1) deteriorates.

To gain a deeper understanding of the noise-immune capability of the system, we performed mode decomposition to the received signal at two pixel points (marked in Fig. 5b) at SNR of −10 dB and −25 dB, respectively (Fig. 5c). For image transport at SNR of −10 dB, high intensity vortex carrying TC = 1 and TC = −1 were well received at points α and β, respectively (Fig. 5c, the left panel). When SNR drops to −25 dB, the intensity of the vorticies carrying TC= ±1 received at the two pixel points decreases significantly (especially for the vortex with TC = −1 at point δ), as shown by the right panel of Fig. 5c. However, our design successfully converts those non-coded modes constituting noise into evanescent waves, thereby completely filtering out these interfering modes (see Supplementary Note 6). As a result, the transmitted signal at SNR of −25 dB is still recognizable. This remarkable result demonstrates that the introduction of radial mode evolution not only facilitates the protection of chirality and TC, but also serves as a barrier against external interference, thus ensuring highly robust information transmission. Notice that the image transmission at SNR of −25 dB observed here means that our design allows the signal to be 300 times lower than the background noise. Such a chiral-protected one-way signal transmission at ultra-low SNR may provide an important means for underwater long-distance signal communication.

Discussion

We have demonstrated the concept of extreme asymmetric transmission with chiral protection by harnessing radial modes in chiral space. Owing to the flexible modulation capabilities of metamaterials, a single vortex beam with a well-defined TC can be perfectly transmitted in the forward direction without altering its chirality and TC. Conversely, transmission in the reverse direction is completely inhibited due to the divergence of momentum. Based on this, by encoding image information into different TC channels, we further realized high-contrast asymmetric image transport. Importantly, the unique way of radial mode evolution induced by the metamaterial provides dual protection for information transmission by not only preserving the chirality and TC but also filtering out undesired modes as noise interference through converting them into evanescent waves. This allow us experimentally achieved image transmission at SNR as low as -25 dB. Our core physical mechanism is not limited to acoustics but can be extended to structured waves in other physical domains—such as optics and electromagnetic—offering valuable functionalities for high-capacity communication, including unidirectional transmission, crosstalk-free operation, and noise immunity.

Methods

Numerical simulations

Equivalent monopole sources are employed to simulate the evolution of radial modes. The finite element method is utilized for full-wave numerical simulations to validate the equivalent monopole sources. To simulate the asymmetric transmission characteristics and radial mode evolution capabilities of the proposed metamaterial, a frequency domain solver is employed. The interface between the metamaterial and the surrounding air is modeled as rigid. The excitation of the chiral beam is simulated using either the background pressure field or the angular and radial distributions of monopole sound sources. In characterizing chiral properties, the transmission characteristics of different modes are analyzed through wave beam decomposition by utilizing the distribution of the cross-sectional sound field after numerical calculations, alongside specific sound pressure and phase distributions on the interface surface.

Experiments

The structure is fabricated using 3D-printed resin material. Both ends of the metamaterial are connected to rigid cylindrical pipes with an inner diameter of 200 mm and a wall thickness of 9 mm. Acoustic horns are attached to both ends of the duct to suppress end reflections. The chiral beam is generated using two rings of 32 independently controlled sound sources, driven by the voltage output module (National Instruments, type NI-9263), to stimulate the chiral beam and encode information. For mode characterization, 16 quarter-in. microphones (GRAS 46BD) are uniformly arranged on the duct wall at equal axial and angular intervals. The PXI multi-function I/O device (National Instruments, type PXIe-4497) is employed to extract and collect the amplitude and phase of sound pressure on the duct wall, and the modal coefficients of the chiral beams are retrieved through beam decomposition. Simultaneously, a microphone is connected to a removable console for sound field reconstruction. External noise interference is simulated using white noise within the frequency range of 1500–4500 Hz.

Data availability

All data supporting the findings of this study are available within the main text and Supplementary Information. Additional data are available from the corresponding author upon request.

References

Wen, X., Cho, C., Zhu, X., Park, N. & Li, J. Nonreciprocal field transformation with active acoustic metasurfaces. Sci. Adv. 10, eadm9673 (2024).

Yang, Z. et al. Creating pairs of exceptional points for arbitrary polarization control: asymmetric vectorial wavefront modulation. Nat. Commun. 15, 232 (2024).

Steudel, S. et al. 50 mhz rectifier based on an organic diode. Nat. Mater. 4, 597–600 (2005).

Liang, B., Yuan, B. & Cheng, J. Acoustic diode: rectification of acoustic energy flux in one-dimensional systems. Phys. Rev. Lett. 103, 104301 (2009).

Nassar, H. et al. Nonreciprocity in acoustic and elastic materials. Nat. Rev. Mater. 5, 667–685 (2020).

Quan, J., Gao, L., Jiang, J. & Xu, Y. Asymmetric acoustic metagrating enabled by parity-time symmetry. J. Appl. Phys. 133, 074504 (2023).

Xu, X.-W., Li, Y., Li, B., Jing, H. & Chen, A.-X. Nonreciprocity via nonlinearity and synthetic magnetism. Phys. Rev. Appl. 13, 044070 (2020).

Fleury, R., Sounas, D. L., Sieck, C. F., Haberman, M. R. & Alù, A. Sound isolation and giant linear nonreciprocity in a compact acoustic circulator. Science 343, 516–519 (2014).

Aurégan, Y. & Pagneux, V. \({{{{\mathcal{P}}}}}{{{{\mathcal{T}}}}}\)-symmetric scattering in flow duct acoustics. Phys. Rev. Lett. 118, 174301 (2017).

Zangeneh-Nejad, F. & Fleury, R. Doppler-based acoustic gyrator. Appl. Sci. 8, 1083 (2018).

Wang, B., Li, Y. & Shen, X. Nonlinear photonic crystals for completely independent asymmetric holographic imaging. Opt. Lett. 49, 375–378 (2024).

Boechler, N., Theocharis, G. & Daraio, C. Bifurcation-based acoustic switching and rectification. Nat. Mater. 10, 665–668 (2011).

Gu, Z., Hu, J., Liang, B., Zou, X. & Cheng, J. Broadband non-reciprocal transmission of sound with invariant frequency. Sci. Rep. 6, 19824 (2016).

Devaux, T., Cebrecos, A., Richoux, O., Pagneux, V. & Tournat, V. Acoustic radiation pressure for nonreciprocal transmission and switch effects. Nat. Commun. 10, 3292 (2019).

Hwang, J. et al. Electro-tunable optical diode based on photonic bandgap liquid-crystal heterojunctions. Nat. Mater. 4, 383–387 (2005).

Wang, Q. et al. Acoustic topological beam nonreciprocity via the rotational Doppler effect. Sci. Adv. 8, eabq4451 (2022).

Shen, C., Li, J., Jia, Z., Xie, Y. & Cummer, S. A. Nonreciprocal acoustic transmission in cascaded resonators via spatiotemporal modulation. Phys. Rev. B 99, 134306 (2019).

Chen, Z. et al. Efficient nonreciprocal mode transitions in spatiotemporally modulated acoustic metamaterials. Sci. Adv. 7, eabj1198 (2021).

Zhu, J., Zhu, X., Yin, X., Wang, Y. & Zhang, X. Unidirectional extraordinary sound transmission with mode-selective resonant materials. Phys. Rev. Appl. 13, 041001 (2020).

Li, Y. et al. Tunable asymmetric transmission via lossy acoustic metasurfaces. Phys. Rev. Lett. 119, 035501 (2017).

Wang, X., Fang, X., Mao, D., Jing, Y. & Li, Y. Extremely asymmetrical acoustic metasurface mirror at the exceptional point. Phys. Rev. Lett. 123, 214302 (2019).

Long, H., Cheng, Y. & Liu, X. Asymmetric absorber with multiband and broadband for low-frequency sound. Appl. Phys. Lett. 111, 143502 (2017).

Li, D., Huang, S., Cheng, Y. & Li, Y. Compact asymmetric sound absorber at the exceptional point. Sci. China Phys., Mech. Astron. 64, 244303 (2021).

Wang, Y.-M. et al. Active broadband unidirectional focusing of terahertz surface plasmons based on a liquid-crystal-integrated on-chip metadevice. Photonics Res. 12, 2148–2157 (2024).

Kotlyar, V. V., Kovalev, A. A. & Volyar, A. V. Topological charge of a linear combination of optical vortices: topological competition. Opt. Express 28, 8266–8281 (2020).

Kotlyar, V. V., Kovalev, A. A. & Nalimov, A. G.Topological Charge of Optical Vortices 1st edn (CRC Press, 2022).

Shen, Y. et al. Optical vortices 30 years on: Oam manipulation from topological charge to multiple singularities. Light Sci. Appl. 8, 90 (2019).

Jiang, X., Li, Y., Liang, B., Cheng, J.-c & Zhang, L. Convert acoustic resonances to orbital angular momentum. Phys. Rev. Lett. 117, 034301 (2016).

Zhang, Y., Chen, M. L. N. & Jun Jiang, L. Analysis of electromagnetic vortex beams using modified dynamic mode decomposition in spatial angular domain. Opt. Express 27, 27702–27711 (2019).

Ng, J., Lin, Z. & Chan, C. T. Theory of optical trapping by an optical vortex beam. Phys. Rev. Lett. 104, 103601 (2010).

Li, J. et al. Three dimensional acoustic tweezers with vortex streaming. Commun. Phys. 4, 113 (2021).

Huo, P. et al. Broadband and parallel multiple-order optical spatial differentiation enabled by Bessel vortex modulated metalens. Nat. Commun. 15, 9045 (2024).

Liu, K. et al. Super-resolution radar imaging based on experimental OAM beams. Appl. Phys. Lett. 110, 164102 (2017).

Shi, C., Dubois, M., Wang, Y. & Zhang, X. High-speed acoustic communication by multiplexing orbital angular momentum. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. 114, 7250–7253 (2017).

Qiao, Z. et al. Multi-vortex laser enabling spatial and temporal encoding. PhotoniX 1, 13 (2020).

Wu, K. et al. Metamaterial-based real-time communication with high information density by multipath twisting of acoustic wave. Nat. Commun. 13, 5171 (2022).

Fu, Y. et al. Sound vortex diffraction via topological charge in phase gradient metagratings. Sci. Adv. 6, eaba9876 (2020).

Fu, Y. et al. Asymmetric generation of acoustic vortex using dual-layer metasurfaces. Phys. Rev. Lett. 128, 104501 (2022).

Zhou, Z., Jia, B., Wang, N., Wang, X. & Li, Y. Observation of perfectly-chiral exceptional point via bound state in the continuum. Phys. Rev. Lett. 130, 116101 (2023).

Qi, H. et al. Dynamically encircling exceptional points in different Riemann sheets for orbital angular momentum topological charge conversion. Phys. Rev. Lett. 132, 243802 (2024).

Forbes, A., de Oliveira, M. & Dennis, M. R. Structured light. Nat. Photonics 15, 253–262 (2021).

Zhang, C., Jiang, X., He, J., Li, Y. & Ta, D. Spatiotemporal acoustic communication by a single sensor via rotational Doppler effect. Adv. Sci. 10, 2206619 (2023).

Liu, X. et al. Spatiotemporal optical vortices with controllable radial and azimuthal quantum numbers. Nat. Commun. 15, 5435 (2024).

Jiang, X. et al. Acoustic orbital angular momentum prism for efficient vortex perception. Appl. Phys. Lett. 118, 071901 (2021).

Zhang, C., Jiang, X. & Ta, D. Revealing the incidence-angle-independent frequency shift in the acoustic rotational Doppler effect. Phys. Rev. Lett. 132, 114001 (2024).

Jiang, X., Liang, B., Cheng, J. & Qiu, C. Twisted acoustics: metasurface-enabled multiplexing and demultiplexing. Adv. Mater. 30, 1800257 (2018).

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by the National Key R&D Program of China (Grant Nos. 2022YFA1404400 [X.W.] and 2022YFE0208000 [X.W.]), the Scientific Research Innovation Capability Support Project for Young Faculty (Grant No. ZYGXQNJSKYCXNLZCXM-D8 [Y.L.]), the National Science Foundation of China (Grant No. 12474463 [X.W.], 12404509 [C.S.], and 124B2087 [Q.W.]), the Shanghai Pilot Program for Basic Research [Y.L.], the Xiaomi Young Talents Program [Y.L.], and the Fundamental Research Funds for the Central Universities [Y.L.].

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Q.W. and Y.L. conceived the idea. Q.W. carried out the theoretical verification and numerical simulations. Q.W., C.L., C.S. and D.H. conducted the experiments and performed data analysis. Q.W., X.W. and Y.L. contributed to discussions and provided comments. X.W. and Y.L. supervised the research. All authors reviewed and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Peer review

Peer review information

Nature Communications thanks Li-Yang Zheng and the other, anonymous, reviewers for their contribution to the peer review of this work. A peer review file is available.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Wang, Q., Liu, C., Song, C. et al. Chirality-protected extreme asymmetric acoustic information transport with noise immunity. Nat Commun 16, 8066 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-025-63557-1

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-025-63557-1