Abstract

Industrial decarbonization refers to the removal or reduction of greenhouse gas emissions, process emissions, or embodied carbon from industry. Building from our experiences working with communities contemplating industrial decarbonization projects, we argue that community-based research can move nebulous calls for “community engagement” to processes that emphasize just and equitable governance. We first summarize the co-benefits and risks of industrial decarbonization for historically marginalized communities. We then draw from our own experiences working on community benefit plans for developer-led projects to show how community-based research can help ensure that industrial decarbonization projects benefit the communities that choose to host them.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Industrial processes account for a substantial portion of greenhouse gas emissions—a third of the United States’ total emissions and 20% of the European Union’s total emissions. “Industrial decarbonization can be defined as technologies or practices that reduce or eliminate greenhouse gas emissions from all aspects of industry”1. Efforts to decarbonize industrial processes thus play a key role in climate policymaking, and encompass efforts such as energy efficiency, electrification, replacing fossil fuels with lower carbon fuels like hydrogen, reducing materials demand, establishing more circular material flows, and promoting carbon capture and storage (CCS), among others. One example is Direct Air Capture (DAC), which is designed to remove CO₂ directly from the atmosphere. Proponents of DAC highlight its ability to achieve net-negative emissions and address unavoidable emissions from sectors where decarbonization is challenging, while critics raise questions about its efficiency, energy requirements, and cost.

Many industrial decarbonization technologies are in the early stages of development and deployment, which means that their impacts on carbon reduction as well as the people and places that host projects are still largely uncertain. Many communities targeted for new energy projects have already borne the burdens of industrial development, such as systematic exclusion from decision-making, disproportionate exposure to environmental hazards, economic hardship, limited access to environmental resources, challenges to maintaining cultural ways of life, and heightened vulnerability to climate change. For example, installing carbon capture, utilization, and storage (CCUS) technologies on natural gas power plants and industrial emitters in the Texas and Louisiana Gulf Coast is predicted to generate additional ammonia emissions that would disproportionately harm the health of Hispanic and Black communities2. Protests against seven proposed US hydrogen hubs have centered on potential environmental damage and a lack of community engagement to address potential harms to already overburdened communities3. Environmental justice organizations have specifically pointed to DAC, CCUS, and hydrogen projects as evidence that industrial decarbonization is dominated by “false solutions” that preserve the power of corporations—and incentivize continued emitting of carbon - rather than fundamentally reorganizing the economy to be more sustainable and equitable4.

Decades of grassroots activism have called for private developers to practice more robust and equitable community engagement, and the successful halting of major projects has resulted in the widespread corporate recognition of the need for a social license to operate. By presenting good community relations as good financial risk management, the social license presents a “win-win” business case for community engagement. Many activists and academics critique this framing for sidelining more crucial questions about justice, equity, and free, prior and informed consent5. This “win-win” framing of engagement, however, was reinforced by stipulations that were attached to the Inflation Reduction Act and the Bipartisan Infrastructure Law, which directed over $6 billion to developer-led industrial decarbonization projects. Until the change of administration in 2025, projects receiving federal awards were required to develop Community Benefit Plans (CBPs). CBPs formalized project plans for community engagement and were intended to help direct 40% of the benefits of federal funding to communities identified by screening tools as historically marginalized, in support of the previous administration’s Justice40 initiative. Federal agencies including the Department of Energy (DOE) promoted CBPs as a way to advance equity while minimizing the risks of project delays and failures due to lack of community engagement and support.

Most of the authors of this Perspectives piece helped design and - in some cases - began to implement CBPs for carbon storage, DAC, and hydrogen projects. Here we build on those (and our past) experiences to show how community-based research can help move nebulous calls for community engagement to processes that emphasize just and equitable governance, providing a greater chance for industrial decarbonization projects to benefit the communities that choose to host them. Community-based research, paired with just process, encourages the co-definition of problems, deep listening, and more equitable collaboration. At the same time, we also signal the fraught position of community engagement as a part of these projects. Community engagement in industrial decarbonization projects is often framed as a question of how to garner support for developer-led projects, rather than how to engage community partners in considering whether or in what form the projects should be implemented at all. The current dominant framing treats community knowledge as input rather than as central to defining the problems and solutions themselves, and developer-led engagement often stops short of community leadership and ownership6. In this Perspectives piece, we outline the opportunities and limitations for centering equity and community priorities in developer-led projects for industrial decarbonization.

What potential co-benefits and risks does community engagement seek to manage?

Community engagement for industrial decarbonization projects frequently revolves around the risks and co-benefits they pose for communities. We therefore begin by summarizing existing academic research on those potential risks and co-benefits to help characterize what is at stake in both engagement-as-usual and attempts to improve it. Co-benefits refer to positive outcomes that are a result of the technology and systems themselves, not those that developers additionally promise to stakeholders as a result of negotiations, such as scholarships, community investments, or project labor agreements. The methodology for this portion of the research was document analysis via a literature review7. The evidence review targeted peer-reviewed academic journals published in English, over the past 20 years, using keywords in their titles and abstracts such as “industrial decarbonization” and “community benefits,” “co-benefits,” “co-impacts,” “barriers,” “challenges,” “risks” and “social acceptance.” The aim was to provide an illustrative, but by no means exhaustive or representative, overview of the relevant literature on the social and community dynamics of net-zero industry with a focus on the United States. These studies are complicated by the fact that industrial decarbonization is not a singular set of technological systems with uniform impacts; CCUS systems present a very different benefit and risk profile than electrification, for example. Caution should therefore be taken with generalizing impacts across applications, sectors, and locations.

What benefits can communities expect from industrial decarbonization?

Industrial decarbonization could provide a range of benefits to local communities, from jobs and job security to investment and community growth and even innovation spillovers. It could also enable improved energy security and/or lower energy services costs or result in reduced air pollution and other environmental benefits. Maintaining or even growing the American manufacturing sector is seen as a critical benefit, as it can provide communities with jobs but also indirect economic benefits such as tax revenue, innovation spillovers, and enhanced resilience. Approximately 12.2 million manufacturing jobs exist in the United States, and as many as 107,000 to 131,000 new high-wage jobs could be created through the necessary capital investment needed for decarbonization by 20351.

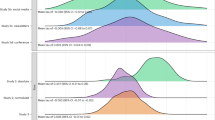

Improved air quality and health gains might also be a considerable benefit, depending on the particular technological system, as noted below. Picciano et al.8 examined the potential air quality benefits from industrial decarbonization and noted mixed findings about the impact for volatile organic compounds, nitrogen oxides, particulate matter, carbon emissions, ammonia, and sulfur dioxide (Fig. 1). While projected industrial decarbonization efforts would see a decline in carbon emissions (21.9%), sulfur dioxide (−6.4%), and nitrogen oxides (−2%), they could see an increase in emissions of ammonia (+10.3%), volatile organic compounds (+3.9%), and particulate matter (+20%). Wang et al.9 were more positive in their assessment, and calculated that even in relatively greener economies such as California, decarbonization would provide about 14,000 fewer premature deaths by 2050 and that 35% of these would come from historically marginalized communities, enhancing equity. That same study projected that the monetary value of those health improvements would reach about $215 billion, far surpassing the estimated cost of $106 billion. In simpler terms: when health co-benefits are included in the assessment, industrial decarbonization more than pays for itself.

Chart projecting impacts of industrial decarbonization for air quality and carbon dioxide emissions, with values showing only the projections for the baseline (2030) scenario and historical or current emissions as of 2017. The projected “baseline” or 2030 numbers are based on no carbon policy in 2030 – a scenario that seems the most likely the current approach taken by the current federal administration. National emissions for the U.S. are shown in billion metric tons (MT) for CO2 and million MT for non-CO2 pollutants. Source: Authors’ own, modified and redrawn substantially using values from P. Picciano, M. Qiu, S. D. Eastham, M. Yuan, J. Reilly, and N. E. Selin, “Air quality related equity implications of U.S. decarbonization policy,” Nat. Commun., vol. 14, no. 1, p. 5543, Sep. 2023, doi: 10.1038/s41467-023-41131-x. Published under a CC-BY 4.0 Attribution International License.

Gallagher et al.10 examined decarbonization pathways from health and environmental justice lenses and reached similarly positive conclusions. They estimated that industrial decarbonization would reduce the risk of primary particulate matter emissions by up to 21%, considering indirect sources from burning, agriculture, and fugitive dust from unpaved roads in addition to direct sources from factories. They also predict that nitrogen and sulfur dioxide emissions would be reduced by roughly 10%. Predicted regional patterns of improved air quality are also notable, with industrial decarbonization producing the most air pollution benefits in the Southeast, along the Great Lakes, as well as in Pennsylvania, California, and New York. They estimated that industrial decarbonization would yield $90.5 billion in annual public health benefits, more than the electricity scenario (only $66.1 billion in benefits) and more than the transport scenario ($43.3 billion). In terms of racial equity, the study estimated that the groups most benefitting from reduced exposure to air pollution would be non-white, racially and ethnically minoritized communities, here referred to as communities of color, in the South (where 58% of the African American population resides) along with urban areas in the North; Hispanic populations in California, Arizona, New Mexico, and Texas; and Asian communities in California, Washington, and Texas. The opposite holds true as well: failing to decarbonize industry would largely and disproportionately harm communities of color and low-income communities, usually defined as a percentage of households living at or below twice the federal poverty level ($32,150 for a family of four in 2025).

The American Council for an Energy-Efficient Economy11 modeled national CO2 and PM2.5 emission profiles as well as facility upgrades aimed at decarbonization and reducing air pollution among cement facilities and found that five of the top 11 facilities emitting well above the median levels of PM2.5 and CO2 per year are located in areas where 66–100% of the population within a three-mile radius meets federal criteria for being classified as a disadvantaged community. They conclude that “such sites are top candidates for early investment in technologies that substantially reduce both carbon and air pollution emissions.”

What risks does industrial decarbonization pose?

Notable risks exist in juxtaposition to the benefits of decarbonization above. These include uncertainty in technical performance, liability concerns, accidents, high costs of deployment, and lack of a mature market. Potentially adverse outcomes – depending on the type of industrial decarbonization – include negative environmental impacts, residual emissions, and CO2, methane or hydrogen leakage, as well as disparities in air pollution and distribution of co-benefits. Industrial decarbonization has the potential to exacerbate rather than alleviate disparities in air pollution, given that many industrial facilities are located in low-income and communities of color, often with high population density in close proximity to sources of high emissions. Colmer et al.12 noted that pollution abatement trends in the U.S. have not altered disparities in exposure to PM2.5 pollution. Although total pollution levels have declined, the most polluted census tracts in 1981 remained the most polluted in 2016, the least polluted census tracts in 1981 remained the least polluted in 2016, and the most exposed subpopulations in 1981 remained the most exposed in 2016. The authors conclude, “Overall, absolute disparities have fallen, but relative disparities persist.”

Wang et al.13 reached a similar conclusion in their assessment of the now-defunct Climate and Economic Justice Screening Tool (CEJST) developed as part of the Biden Administration’s Justice40 Initiative, which failed to include race in its metrics. They noted that the application of CEJST to guide ambient air pollution emission reductions may eliminate the modest exposure disparities by income, but not the frequently larger disparities by race and ethnicity. A number of EJ organizers and scholars strongly disagreed with the decision to exclude race as a factor, arguing that doing so would impede scientific, evidence-based analyses. Legal challenges to analyses factoring in race14 contributed to decisions to exclude race from the federal screening tools15. This was a loss, given that decades of research has regularly and conclusively demonstrated that race is a key determinant in environmental decisions that result in negative impacts on surrounding communities16,17, and that some forms of industrial decarbonization are predicted to worsen health outcomes for communities of color2.

Communities that have already experienced negative impacts also point out that some approaches to industrial decarbonization facilitate the continued use of fossil fuels that created such harm in the first place. CCUS is a key example, as it can be used to promote additional oil production (via enhanced oil recovery) and is being developed to maintain the viability of oil and gas fields, or coal- and natural gas plants, subject to increased emission regulations. Indeed, a 2024 report from the Government Accountability Office found that over 90% of DOE investments in carbon management had gone to reducing emissions from coal-based facilities18. Many environmental organizations argue that hefty federal investments in CCUS would be better directed to building out renewable energy infrastructure instead.

These concerns have spurred activism that is raising crucial questions. Grubert and Hastings-Simon19 note the scalar mismatch between the benefits and harms of industrial decarbonization, writing that it is “intended to create national (and global) benefit at the expense of local harms, and that host and prospective host communities are likely to understand, and oppose, concrete and easily communicated negative impacts.” Specifically writing about hydrogen – but applicable more broadly to industrial decarbonization technologies – Bukirwa et al.20 write: “Given this past and persistent discrimination, it is understandable that communities are wary and skeptical of heavy industry development, even if the intent is a cleaner energy future. There are legitimate reasons why communities are skeptical of replacing unabated fossil fuels with hydrogen, including health, safety, environmental, and water usage concerns, and that certain hydrogen production methods will perpetuate some fossil fuel industries.” These serious concerns form the backdrop of community engagement in emerging industrialization decarbonization – and efforts to improve it.

Community based research and procedural justice

Commitments to “community engagement” have become de rigueur in the corporate world, and federally-funded industrial decarbonization projects included requirements for what funding calls described as “meaningful engagement… [which] involves building relationships and having a two-way dialog with mutual learning that shapes how projects are developed”1. Engagement, however, is a plastic word that can encompass everything from simply providing information to stakeholders to deeply co-designing technological systems with communities. The kinds of community engagement practiced by most private developers can “maintain the status quo and the unequal distribution of burdens of benefits in energy transitions”21. In instances where engagement is made superficial, such as in the case of providing input on decision-making around the location of oil and gas pipelines with little effect on outcomes, experiences of “performative” participation can tangibly harm the people who participate22.

In contrast, community-based research is well suited to promoting opportunities for people to shape project designs to advance community visions, voice concerns, minimize adverse impacts, and ensure the delivery of benefits as defined by themselves. Community-based research is grounded in epistemic justice, which draws attention to knowledge, specifically the recognition of people as knowers, experts, and innovators. Ottinger23 argues for treating epistemic justice as “careful knowing, or practices of empirical investigation and meaning-making responsive to the needs of marginalized knowers.” A primary concern is to counteract the devaluing of historically marginalized communities’ own knowledge. Castro-Diaz et al.24 summarize key research frameworks from the social sciences that center deep listening to and learning from community members and their unique expertise (1–7 in Table 1). These approaches help to address power differentials among project proponents, researchers, and communities.

Research methodologies from the humanities are also key to better documenting people’s lived experiences, as well as engaging them in imagining alternative futures. Framing and tools from humanities disciplines can be used to develop research questions and methodologies that treat people and communities as full human beings rather than narrowly as stakeholders and ask questions about how carbon management and similar projects make assumptions about – and aim to reconfigure – fundamental aspects of society and culture such as space and belonging, work and individual autonomy, and the need for what Mbembe calls “co-belonging”25.

The field of science and technology studies also provides multiple methodologies for integrating social considerations into the design of technological systems. Value Sensitive Design integrates human values through the design process26. Participatory Technology Assessment formalizes opportunities for the public to provide feedback on technology development27. Consent-based siting provides a process through which communities themselves develop site-specific assessment criteria to determine whether to host an industrial project28. Rather than presenting a community with a pre-designed project, these tools open up broader deliberations about technical decision-making to directly include community input into the project design – for example, which technologies are selected, where infrastructure is sited, and which environmental controls are utilized. Fundamentally, participatory design frameworks play a critical role in doing the work of identifying projects that best meet the needs of a community, while also functioning within environmental, cultural, and economic resource constraints of the region and its population. In this sense, they echo tenants of the appropriate technology movement29,30, but applied to projects that operate at a complex infrastructural systems level.

These research approaches are especially powerful when paired with frameworks from community organizing that are grounded in principles that try to equalize power relations and prioritize community-created visions and goals. Facilitating Power, a community-based organization focused on racial equity and environmental justice builds from Arnstein’s influential Ladder of Citizen Participation to create a spectrum of community engagement that moves through marginalization, placation, and tokenization, to voice, delegated power, and ultimately community ownership31. Figure 2 visualizes these community engagement techniques on a spectrum of no involvement to advanced involvement such as ownership.

Rosa Gonzalez’s visualization of public engagement moving from activities that marginalize communities and their interests to community decision-making and ownership. Reproduced with permission from R. González, “The Spectrum of Community Engagement to Ownership.” Facilitating Power. Available online: https://www.facilitatingpower.com/spectrum_of_community_engagement_to_ownership.

Epistemic justice pushes us to diversify our sources to include written and oral materials that are community-generated or that center community voices. For example, the CARE and FAIR Principles for Indigenous data futures32, The Principles of Environmental Justice33, and the Jemez Principles for Democratic Organizing34. These materials can encompass a wide range of sources, from memoranda to newsletters to blog posts to action plans, such as the 10-Year Strategic Action Plan recently drafted by The Southeast Region Environmental Justice Network35, which the Georgia Tech team is incorporating into its work with the Southeast DAC Hub (described in greater detail in the following section).

While centering community perspectives is crucial for epistemic justice, it is equally important to avoid fetishized views of local knowledge. Community perspectives are the product of complex social and material relationships that interact within power structures at multiple scales—including with government agencies, industry, advocacy organizations, as well as other invested communities36,37. Community perspectives are also deeply heterogenous and contradictory, given the diversity of stakeholders and their positions relative to industrial development projects38,39,40,41. Scholars working in these spaces must, therefore, necessarily acknowledge that “local knowledge” is always to be understood as partially representative, as well as always altered in-process by researchers’ own power, institutional affiliations, and positionalities42,43,44. The pitfalls of fetishization and partial representation reinforce the importance of maximizing the use of co-produced, community-driven, and participatory methodologies that decenter the researcher and the potential for performative engagement.

Gaining a nuanced sense of local priorities and values using these frameworks can serve as the foundation for more meaningful deliberation and co-design and potential co-ownership of industrial decarbonization projects.

More just engagement in federally-funded industrial decarbonization projects

The first section of this article identified four themes emerging from existing research: (1) industrial decarbonization offers air quality improvements, but relative inequities in exposures persist; (2) these inequities are unlikely to be addressed given race-blind policy approaches; (3) some forms of industrial decarbonization that facilitate the continued use of fossil fuels can entrench environmental justice concerns; and (4) there is a scalar mismatch between the global benefits and local harms of decarbonization projects. We then laid out how community-based research, paired with procedural justice, can lay the basis for more just community engagement to address those risks. In this section, we share our own experiences attempting to put those practices into action through our own participation in industrial decarbonization projects.

The data from this section comes from our active involvement in designing and beginning to implement Community Benefit Plans (CBPs) for DOE-funded projects, with a focus on DAC and carbon capture and storage. Collectively, our experiences underscore epistemic and procedural justice as a necessary precursor to addressing any of the previously identified risks of industrial decarbonization.

We begin by noting that our experiences have not been uniform - and that institutional positionality matters for what teams are able to do. When our institutions were the project leads (“prime recipients”), we wrote our own CBPs and inflected project direction and leadership with community knowledge and priorities. These close connections also raised the risk of cooptation. Serving as sub-recipients meant that our teams did not have ultimate say over the CBPs that were proposed, but teams experienced more independence to direct their own actions and center community perspectives. Both power for CBP leads to shape project decision making and independence for CBP leads to design and facilitate processes that meaningfully engage and empower communities are critical. We encountered other projects in which there were no people with critical social science, humanities, or energy justice training included in conceptualizing or implementing the CBPs, which instead were managed by public relations firms.

Our teams have managed the two major barriers to making industrial decarbonization more accountable to local communities: procedural injustice and epistemic injustice. Procedural injustices were embedded into the application process for federal funds. Most applications for funding were made by developers (due to the cost share requirement) and encouraged but did not require documentation of community support. Both literature and practice demonstrate that engagement is rarely meaningful when it comes after major project decisions have been made. Procedural justice was also under-emphasized in the initial round of applications, which instead focused on distributive benefits and harms. By focusing on distributive benefits versus harms, the engagement encouraged by CBPs neglected to address the underlying structures that exclude diverse voices from defining what counts as benefits and harms in the first place. Foundational concerns include due process, transparency, intra- and inter-generational equity, and accountability45,46,47.

Epistemic injustice was a second key barrier, including in how project benefits and risks were conceptualized and tracked. Applicants for federal funds were required to set out which “benefits” the projects would deliver, without requiring that they be jointly defined with communities, and propose quantitative measures for tracking them. The existing research on co-benefits, summarized in the first section, has also focused on those that are quantifiable: new jobs, improved air quality, and improved health. While quantitative metrics can help make patterns visible, they also risk “informating” justice48, or rendering justice issues into problems that can be understood and manipulated through information systems49. This risks narrowing the kinds of ethical questions that can be asked and answered, as well as the kinds of benefits and risks that can be tracked and monitored. Epistemic justice further compels us to consider how community knowledge and concerns can be integrated into the design, collection, and analysis of metrics. Developing “everyday indicators” could be one strategy to create measurements from the ground up50,51. Another related strategy is to work with communities early on to co-develop targets and assessment mechanisms for risks and benefits, as described in the paragraph about JET below.

Our approaches to promoting epistemic and procedural justice have been diverse, but all seek to facilitate more meaningful opportunities for community members to articulate their priorities and values and to have a greater say in how projects develop and are managed. A recurring challenge has been ensuring that community benefits are systematically integrated with technical objectives. A team from the Colorado School of Mines is using community-based research to integrate local knowledge and priorities into the feasibility study for a potential carbon storage hub in the southern part of the state. A team of anthropologists and STEM students have worked with environmental and energy justice advocates, conducting participant-observation at meetings and marches, interviewing community members, and analyzing oral histories and other publicly available archival material to better understand the history of the region so that project planning can attend to – and hopefully ameliorate – past harms of the region’s steelworks and coal-fired power plants. One clear outcome, tying back to the “false solution” concern identified above, is the identification of a clear preference that storage prioritize CO2 from local hard-to-abate industries, such as concrete, rather than throwing a lifeline to fossil fuels that have already disproportionately harmed their community. Another outcome has been a more clear set of desired benefits, including expanded community-based air monitoring, water well testing, and job skills training for the formerly incarcerated. Going forward, the team aims to promote procedural justice by collaboratively setting out what consent-based siting would look like for a potential future carbon storage hub. Consent-based siting would lay the groundwork for procedural justice in determining whether the hub should move forward from the current feasibility stage into construction and commercialization.

Georgia Tech’s work with the Southeast DAC Hub is focusing on educating leaders of community-based organizations across the region in emerging carbon management technologies and incorporating this education into their community and economic development work. Led by a sustainable communities office, the Georgia Tech team is convening engineers, project developers, and community partners across the Southeast to develop a curriculum that examines an array of carbon management technologies (e.g., electrification, battery storage, hydrogen, carbon capture) as they relate to the core work that the community organizations work on, including food, water, land, air, and energy. The goal is to help CBOs develop understandings of the potential benefits and harms these technologies present, from a local perspective, rather than thinking about them only in terms of ideological positions like “false solutions,” and to prepare them to make informed decisions about their energy futures.

The Just Energy Transition (JET) Center at Arizona State University supports communities impacted by the energy transition to forge new economic futures. These efforts always begin with community visioning and an asset inventory by the community members to identify what they love about their community and what they want to build for the future. These processes position communities to negotiate with developers with strength and self-knowledge, with a clear sense of the co-benefits that are most important to them. For example, in community visioning sessions led by JET, community members were vocal in their opposition to certain kinds of industries that didn’t align with their values and that opposition was inelastic to salary and job growth potential. Early engagement with impacted communities affords those communities the opportunity to develop their own success metrics and can contribute to real and perceived co-ownership of project outcomes.

Lastly, Visage Energy offers a final case study of application of a stakeholder engagement framework to ensure that community perspectives inform the technical planning and feasibility of CCS and DAC deployment for industrial and power generation facilities. The focus has been on establishing clear channels for ongoing dialog between engineering teams, local organizations, and community leaders. By convening stakeholders early in the process, prior to finalizing key project parameters, Visage Energy integrated regional environmental priorities, labor force realities, and community-defined success metrics into the overall project design. This stakeholder engagement strategy went well beyond “public relations” models to focus on iterative communication and joint decision-making. For instance, community members and developers jointly identified their priority concerns such as air quality impacts, job training needs, or infrastructure reliability.

Our experiences show that iterative engagement processes, anchored in social science and energy justice principles, can help align projects with local priorities, facilitate feedback loops, and address workforce development needs. When structured to include a range of perspectives, from engineering to humanities, these approaches can yield more robust outcomes that anticipate long-term sustainability and community wellbeing, rather than merely fulfilling regulatory or public relations benchmarks. While it is too early to say how much these efforts will address the inequities of risks and benefits identified in the first section, as none of these are construction-phase projects, we share what we have learned so far. While our participation in these projects aims to make them more just, the structures that give them shape present serious limitations to that work. This underlines the fraught nature of community-based research in projects that are ultimately led by developers and inspires our recommendations for making such efforts more meaningful.

Value of slowing down and acting from the top-down, bottom-up, and middle-out

Industrial decarbonization projects that depended on federal infrastructure funding now find themselves in legal limbo. Ironically, new uncertainties about their fate may provide an opportunity to slow down and practice the kind of relationship building that was difficult during the frenetic pace of the initial clean energy funding rollout. We conclude with four concrete recommendations to take advantage of the pace slowing and promote more equitable relationships between communities and developers.

First, our experiences directly highlight the need for sustained government funding opportunities to create more just structures for soliciting, implementing, and evaluating applications and projects. Project proponents ought to be required to demonstrate that appropriate local and regional government bodies and civil society groups have not simply been informed about the project, but are engaged in a process of determining whether and how it can advance local priorities without creating harm, especially for historically marginalized populations. This would require more availability of funds for community-directed visioning before the project is finalized and funding for ongoing community-directed evaluation of risks and harms during its implementation. The DOE previously ran Phase 0 programs that assisted new applicants in collecting the data and developing the relationships necessary to qualify for a DOE grant. A Phase 0 program for community engagement that transcended specific decarbonization projects would be an opportunity to invest in those relationships that make real co-design a possibility, and it would give DOE a set of relationships with community benefits practitioners that could be leveraged in future FOAs.

Ongoing uncertainties in federal funding, however, pose major challenges to community engagement as usual, let alone more just and expansive visions. It is always challenging to meaningfully engage communities in projects whose development depends on a competitive funding process with no guarantees. Developing meaningful, trusting relationships with communities requires consistency, and delays in funding compromise trust. The January 2025 Executive Order on DEIA attempted to eliminate community benefits planning while maintaining infrastructure development programs. This was antithetical to relationship building and reinforced skepticism about the role of communities in industrial decarbonization planning. Models that espouse co-management and community-ownership31 would more radically open up spaces for developing industrial decarbonization projects that serve the needs of communities and the climate, mitigating the scalar mismatch that currently exists between global benefits and local harms19.

Second, industrial decarbonization projects and research must include communities and their expertise in broadening current considerations of co-benefits and risks. The majority of existing co-benefits research considers air pollution and carbon emissions. Future work should 1) develop frameworks to include marginalized communities themselves in the identification and tracking of benefits and 2) explore a broader range of co-benefits, as desired and defined by communities. In their report on state-level climate and clean energy programs, Callahan et al. emphasize community based organization capacity-building, including relationship-building, knowledge transmission, and leadership development, as key co-benefits of the strongest programs. Sovacool and colleagues found 128 co-benefits for four low-carbon transitions in Europe and noted that some were political or even social.52 Building on this work in a follow-up study, Sovacool et al.53 applied socio-technical thinking to include a diffuse array of possible impacts, both positive and negative, of carbon removal and net-zero transitions: financial and economic co-benefits such as the expansion of markets, business models, government revenues, and carbon credits (among others); socio-environmental co-benefits such as protection of habitats, forests, oceans or species, or the provision of decent work and high paying jobs; technical impacts such as the improved performance of systems, disruptive or positive innovation patterns for a sector, enhanced efficiency, or positive and negative learning and experimentation; political and institutional co-impacts such as the achievement of policy goals (relating to industrial strategy, equity and leveling up, or energy security) or the creation of a moral hazard. Such broad and multidimensional assessments of co-impacts could be applied to industrial decarbonization, working in partnership with local communities to identify their priorities.

Third, neither of the previous two recommendations will be successful without intervening in how developers and technologists understand and practice “community engagement.” As we argued above, engagement ought to be grounded in procedural and epistemic justice. Whereas most attention to capacity-building centers on ensuring that the public has the competency and literacy to engage in decarbonization partnerships with the project leads, we emphasize that learning also needs to happen on the side of project developers and technologists. Even the most well-intentioned developers frequently presume that community opposition is a result of a lack of knowledge, rather than a legitimate critique of industry assumptions, and they often presume that the roles of social scientists are to garner social acceptance rather than critically understand the inherent social dimensions of any proposed technology or system. Engineers and applied scientists are frequently under-prepared to grapple with those social dimensions, given a pervasive technical/social dualism54 that defines “social” skills, related to areas such as community, engagement, justice, and ethics, as “soft skills” rather than core competencies55. This leads to the marginalization of justice considerations and engagement skills in their professional preparation. Existing efforts to train STEM students to consider the inherent justice dimensions of their work and engage communities in more just ways56 can be scaled up. Developers and technologists must be trained to equitably engage with community partners as experts and to collaborate with them to meaningfully integrate their perspectives into technology-focused studies, design, and deployment.

Fourth and finally, industrial decarbonization action must occur at multiple scales, not just where technology is being deployed, or among factory floors and industrial facilities57. Instead, some actions need to be cultivated from the top-down, through technocratic efforts done at the level of policy and regulation, utilizing instruments such as tax incentives, technology demonstrations, local or regional carbon taxes, and possibly carbon border adjustment mechanisms58. Other actions can occur from the bottom-up, utilizing more democratic efforts such as changing behaviors and consumption patterns that lower demand for carbon-intensive industrial products, or putting pressure on industrial firms to be more sustainable59,60. Still other efforts can be from the middle out, at the meso level of intermediaries, social movements, and community organizations61,62. When such concerted actions occur across top-down, bottom-up, and middle-out scales, it tends to promote multiple levels of accountability and also successfully lead to reconfiguring power relations63. It also promotes what Ostrom terms polycentric governance efforts that blend together scales and actors to address collective action problems in ways that no single actor can do alone64. Industrial decarbonization therefore becomes a multi-scalar, multi-technological, multi-sectoral and multi-institutional phenomenon rather than being siloed within any single party, sector, firm, or policy domain.

More community-based, equity-oriented social science and humanities research should replace vague community engagement cut in the cloth of corporate public relations, slowing down industrial decarbonization so that it moves at the speed of trust. In their review of recent articles related to this topic, Moore and Milkoreit65 challenge us to consider concepts such as “imagination” and “imagining alternative futures” from the perspectives of history and power, noting that “participatory and coproduction processes of imagination can be thoughtfully designed in ways that address the power asymmetries that have historically dominated decision making for the future, or conversely, can be designed and used to resist changing power asymmetries, or even to imagine an enduring unsustainable or unjust path for the future.” One of the central questions for their research agenda—“What is the relationship between imagination, power and governance”—can serve as an important foundation for just processes that facilitate a clean and equitable energy future.

References

Department of Energy, Industrial Decarbonization Roadmap, DOE/EE−2635, (2022).

Waxman, A. R., Huber-Rodriguez, H. R., & Olmstead, S. M. What are the likely air pollution impacts of carbon capture and storage?. J. Assoc. Environ. Resour. Econ. 11(S1), S111–S155 https://doi.org/10.1086/732195 (2024).

Al-Sadi, B. Seven Months After the DOE Hydrogen Hub Announcement: Where Are We Now on Community Engagement?” Accessed: Feb. 19, [Online]. Available:https://www.nrdc.org/bio/batoul-sadi/seven-months-after-doe-hydrogen-hub-announcement-where-are-we-now-community (2025).

J. Chemnick, False promise’: DOE’s carbon removal plans rankle community advocates,” E&E News by POLITICO. Accessed: Feb. 19, [Online]. Available: https://www.eenews.net/articles/false-promise-does-carbon-removal-plans-rankle-community-advocates/ (2025).

Smith, J. M. Extracting Accountability: Engineers and Corporate Social Responsibility (The MIT Press, 2021).

Baxter, J. et al. Scale, history and justice in community wind energy: An empirical review. Energy Res. Soc. Sci. 68, 101532 (2020).

Grant, M. J. & Booth, A. A typology of reviews: an analysis of 14 review types and associated methodologies. Health Inf. Libr. J. 26, 91–108 (2009).

Picciano, P. et al. Air quality related equity implications of U.S. decarbonization policy. Nat. Commun. 14, 5543 (2023).

Wang, T. et al. Health co-benefits of achieving sustainable net-zero greenhouse gas emissions in California. Nat. Sustain. 3, 597–605 (2020).

Gallagher, C. L. & Holloway, T. U.S. decarbonization impacts on air quality and environmental justice. Environ. Res. Lett. 17, 114018 (2022).

ACEEE. Aligning Industrial Decarbonization Technologies with Pollution Reduction Goals to Increase Community Benefits,” ACEEE, Washington, DC. Accessed: Feb. 19, 2025. [Online]. Available https://www.aceee.org/sites/default/files/pdfs/aligning_industrial_decarbonization_technologies_with_pollution_reduction_goals_to_increase_community_benefits_-_encrypt.pdf.

Colmer, J., Hardman, I., Shimshack, J. & Voorheis, J. Disparities in PM2.5 air pollution in the United States. Science 369, 575–578 (2020).

Wang, Y. et al. Air quality policy should quantify effects on disparities. Science 381, 272–274 (2023).

Martin, V. St. “In Louisiana’s ‘Cancer Alley,’ excitement over new emissions rules is tempered by a legal challenge to federal environmental justice efforts. Inside Clim. News May 10, Accessed: Jun. 21, 2024. [Online]. Available:https://insideclimatenews.org/news/10052024/louisiana-cancer-alley-emission-rules-environmental-justice/ (2024).

Shrestha, R., Neuberger, J., Rajpurohit, S., Saha, D. 6 Takeaways from the CEQ Climate and Economic Justice Screening Tool, Mar. 2022, Accessed:Feb. 10, [Online]. Available: https://www.wri.org/technical-perspectives/6-takeaways-ceq-climate-and-economic-justice-screening-tool (2025).

Mohai, P., Pellow, D. & Roberts, J. T. Environmental justice. Annu. Rev. Environ. Resour. 34, 405–430 (2009).

Bullard, R. D., Mohai, P., Saha, R., Wright, B. Toxic wastes and race at twenty: why race still matters after all of these years. Environ. L. 38, 371 (2008).

United States Government Accountability Office, Decarbonization: opportunities exist to improve the Department of Energy’s management of risks to carbon capture projects: report to congressional committees,” United States. Accessed: Feb. 19, [Language material, Electronic resource, Computer, Online resource]. Available: http://catalog.gpo.gov/F/?func=direct&doc_number=001262807&format=999 (2025).

Grubert, E. & Hastings-Simon, S. Designing the mid-transition: a review of medium-term challenges for coordinated decarbonization in the United States. WIREs Clim. Change 13, e768 (2022). p.

Bukirwa, P., Gamage, C., McClellan, M., Sheerazi, H., Westler, G. Delivering Equitable and Meaningful Community Benefits via Clean Hydrogen Hubs, Jan. 2024. Accessed: Feb. 19, [Online]. Available: https://rmi.org/delivering-equitable-and-meaningful-community-benefits-via-clean-hydrogen-hubs/ (2025).

Suboticki, I., Heidenreich, S., Ryghaug, M. & Skjølsvold, T. M. Fostering justice through engagement: a literature review of public engagement in energy transitions. Energy Res. Soc. Sci. 99, 103053 (2023).

Bell, S. E. et al. Pipelines and power: psychological distress, political alienation, and the breakdown of environmental justice in government agencies’ public participation processes. Energy Res. Soc. Sci. 109, 103406 (2024).

Ottinger, G. Responsible epistemic innovation: How combatting epistemic injustice advances responsible innovation (and vice versa). J. Responsib. Innov. 10, 2054306 (2023).

Castro-Diaz, L. et al. Participatory research in energy justice: guiding principles and practice. Prog. Energy 6, 033005 (2024).

Franklin Humanities Institute, “Achille Mbembe, Future Knowledges & the Dilemmas of Decolonization.” Accessed: Feb. 19, [Online]. Available: https://humanitiesfutures.org/media/achille-mbembe-future-knowledges-dilemmas-decolonization-2/ (2025).

Friedman, B., Kahn, P. H., Borning, A., & Huldtgren, A. Value sensitive design and information systems. in Early Engagement and New Technologies: Opening Up the Laboratory pp. 55–95 (Springer, 2013).

Guston, D. H. & Sarewitz, D. Real-time technology assessment. Technol. Soc. 24, 93–109 (2002).

Richter, J., Bernstein, M. J. & Farooque, M. The process to find a process for governance: nuclear waste management and consent-based siting in the United States. Energy Res. Soc. Sci. 87, 102473 (2022).

Pearce, J. M. & Mushtaq, U. Overcoming technical constraints for obtaining sustainable development with open source appropriate technology. in 2009 IEEE Toronto International Conference Science and Technology for Humanity (TIC-STH) pp. 814–820 (2009).

Mittlefehldt, S. From appropriate technology to the clean energy economy: renewable energy and environmental politics since the 1970s. J. Environ. Stud. Sci. 8, 212–219 (2018).

González, R. The Spectrum of Community Engagement to Ownership. Facilitating Power, Available online: https://movementstrategy.org/resources/the-spectrumof-community-engagement-to-ownership/ (2019).

Carroll, S. R., Herczog, E., Hudson, M., Russell, K. & Stall, S. Operationalizing the CARE and FAIR Principles for Indigenous data futures. Sci. Data 8, 108 (2021).

Delegates to the First National People of Color Environmental Leadership Summit, The Principles of Environmental Justice (EJ).” [Online]. Available: https://www.ejnet.org/ej/principles.pdf

Southwest Network for Environmental and Economic Justice (SNEEJ), Jemez Principles for Democratic Organizing. Working Group Meeting on Globalization and Trade, Jemez, New Mexico, 1996. Available online: https://www.ejnet.org/ej/jemez.pdf.

The Southeast Region Environmental Justice Network Steering & The Southeast Region Environmental Justice Network Steering Committee, “Southeast Region Environmental Justice Network 10-Year Strategic Action Plan,” CEAR Hub. Accessed: Feb. 19, 2025. [Online]. Available https://www.cearhub.org/projects/southeast-region-environmental-justice-network-10-year-strategic-action-plan.

Jasanoff, S. States of Knowledge: The Co-production of Science and the Social Order (Routledge, 2004). Accessed: Dec. 19, [Online]. Available: https://www.routledge.com/States-of-Knowledge-The-Co-production-of-Science-and-the-Social-Order/Jasanoff/p/book/9780415403290 (2023).

Callon, M. The role of lay people in the production and dissemination of scientific knowledge. Sci. Technol. Soc. 4, 81–94 (1999). Marpp.

Ottinger, G. Refining Expertise How Responsible Engineers Subvert Environmental Justice Challenges (University Press, 2013).

Wylie, S., Shapiro, N. & Liboiron, M. Making and doing politics through grassroots scientific research on the energy and petrochemical industries. Engag. Sci. Technol. Soc. 3, 393–425 (2017). Sep.

Cooley, R. & Casagrande, D. Marcellus Shale as golden goose: the discourse of development and the marginalization of resistance in Northcentral Pennsylvania. in ExtrACTION (Routledge, 2017).

Jacquet, J. B. Landowner attitudes toward natural gas and wind farm development in northern Pennsylvania. Energy Policy 50, 677–688 (2012).

Corburn, J. Street Science: Community Knowledge and Environmental Health Justice (The MIT Press, 2005) https://doi.org/10.7551/mitpress/6494.001.0001.

Minkler, M. Ethical challenges for the ‘outside’ researcher in community-based participatory research. Health Educ. Behav. Publ. Soc. Public Health Educ. 31, 684–697 (2004).

Arancibia, F. Rethinking activism and expertise within environmental health conflicts. Sociol. Compass 10, 477–490 (2016).

Sovacool, B. K., Heffron, R. J., McCauley, D. & Goldthau, A. Energy decisions reframed as justice and ethical concerns. Nat. Energy 1, 16024 (2016).

Dutta, N. S. et al. JUST-R metrics for considering energy justice in early-stage energy research. Joule 7, 431–437 (2023).

Owen, R. et al. A framework for responsible innovation. in Responsible Innovation pp. 27–50 (John Wiley & Sons, Ltd, 2013).

Smith, J. M. The politics of percentage: informating justice in the US clean energy rush. Crit. Anthropol. 44, 341–361 (2024).

Fortun, K. From Bhopal to the informating of environmentalism: risk communication in historical perspective. Osiris 19, 283–296 (2004).

Goodale, M. Justice in the vernacular: an anthropological critique of commensuration. Law & Social Inquiry. 49 7–25 (2024).

Underhill, V. & Esparza, R. Wildflowers and water: desire, joy, and creativity in environmental justice organizing. Environ. Justice env.0058 (2022) https://doi.org/10.1089/env.2021.0058 (2021).

Sovacool, B. K., Martiskainen, M., Hook, A. & Baker, L. Beyond cost and carbon: The multidimensional co-benefits of low carbon transitions in Europe. Ecol. Econ. 169, 106529 (2020).

Sovacool, B. K., Baum, C. M. & Low, S. Beyond climate stabilization: exploring the perceived sociotechnical co-impacts of carbon removal and solar geoengineering. Ecol. Econ. 204, 107648 (2023).

Faulkner, W. Nuts and Bolts and people’: gender-troubled engineering identities. Soc. Stud. Sci. 37, 331–356 (2007).

Cech, E. A. The (Mis)Framing of social justice: why ideologies of depoliticization and meritocracy hinder engineers’ ability to think about social injustices. in Engineering Education for Social Justice: Critical Explorations and Opportunities (ed Lucena, J.) in Philosophy of Engineering and Technology., Dordrecht: Springer Netherlands, pp. 67–84. (2013).

Leydens, J. A. & Lucena, J. C. Engineering Justice: Transforming Engineering Education and Practice (Wiley-IEEE Press, 2017). Accessed: Jul. 01, [Online]. Available: https://www.wiley.com/en-us/Engineering+Justice%3A+Transforming+Engineering+Education+and+Practice-p-9781118757307 (2018).

Sovacool, B. K. et al. Beyond the factory: ten interdisciplinary lessons for industrial decarbonisation practice and policy. Energy Rep. 11, 5935–5946 (2024).

Bhardwaj, A. Styles of decarbonization. Environ. Polit. 32, 619–641 (2023).

Upham, D. P., Sovacool, P. B. & Ghosh, D. B. Just transitions for industrial decarbonisation: a framework for innovation, participation, and justice. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 167, 112699 (2022).

Welton, S. Decarbonization in Democracy,” May 14, 2019, Social Science Research Network, Rochester, NY: 3388219. Accessed: Feb. 19, [Online]. Available: https://papers.ssrn.com/abstract=3388219 (2025).

Schenk, N. J., Moll, H. C. & Schoot Uiterkamp, A. J. M. Meso-level analysis, the missing link in energy strategies. Energy Policy 35, 1505–1516 (2007).

Parag, Y. & Janda, K. B. More than filler: middle actors and socio-technical change in the energy system from the ‘middle-out. Energy Res. Soc. Sci. 3, 102–112 (2014).

Avelino, F. Power in sustainability transitions: analysing power and (dis)empowerment in transformative change towards sustainability. Environ. Policy Gov. 27, 505–520 (2017).

Ostrom, E. Beyond markets and states: polycentric governance of complex economic systems. Am. Econ. Rev. 100, 641–672 (2010).

Moore, M.-L. & Milkoreit, M. Imagination and transformations to sustainable and just futures. Elem. Sci. Anthr. 8, 081 (2020).

Acknowledgements

Reproduced with permission from the National Academy of Sciences, courtesy of the National Academies Press, Washington, D.C. The authors gratefully acknowledge the National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine for the opportunity to present our research at the 2024 workshop Developing and Assessing Ideas for Social and Behavioral Research to Speed Efficient and Equitable Industrial Decarbonization. This article is a synthesis of two papers commissioned for that workshop. The authors also thank their community partners, colleagues, and students for their collaboration. BS acknowledges that this work was supported by the UKRI ISCF Industrial Challenge Fund within the UK Industrial Decarbonization Research and Innovation Center (IDRIC) award number: EP/V027050/1.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

B.S. served as the sole author of his original workshop paper, and the remaining authors (J.H., K.J., L.K., K.O., D.R., J.S.) contributed to the conceptualization, writing, review, and editing of the other original workshop paper, which was presented by J.H., who also served as its corresponding author. J.S. led the integration of the two papers into this Perspective and the process of revising it, with contributions from all co-authors.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Peer review

Peer review information

Nature Communications thanks the anonymous reviewers for their contribution to the peer review of this work.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Smith, J., Hirsch, J., Jalbert, K. et al. Community-based research supports more just and equitable industrial decarbonization. Nat Commun 16, 8239 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-025-63569-x

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-025-63569-x