Abstract

One significant obstacle to the colonization of Mars is the high cost of excess launch mass required for long-term space travel and the establishment of a settlement. The Sabatier reaction provides a means for recycling water and rocket propellant that dramatically reduces the supplement. Herein, we introduce a membrane Sabatier system by integrating a catalytic reactor with an H2O vapor permselective membrane tube. We achieve a substantial increase in CO2 conversion, a high CH4 yield and excellent long-term stability via highly efficient in-situ water removal. Furthermore, the system’s robustness under intermittent power supplies, and its adaptability across a wide range of reaction conditions, makes it highly compatible with the electrolytic hydrogen production system, which is subject to unstable solar energies. The advent of the membrane Sabatier system heralds a transformative approach to the recycling of H2O and rocket propellant in long-term interplanetary exploration.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The SpaceX Starship successfully achieved a soft splashdown using liquid CH4 as propellant and marked a significant milestone in the era of Martian exploration1,2,3. To realize colonization, thousands of people must be shuttled between Earth and Mars4,5,6,7,8. One significant obstacle to this vision is the high cost of excess launch mass required for long-term space travel and the establishment of a settlement. To this end, water (H2O) and the fuel needed to bring the spacecraft back to Earth are the most critical supplies, occupying a substantial launch mass in a spacecraft9,10,11,12,13. It is estimated that sending a kilogram to the International Space Station costs around USD $21,00014. For a nine-month journey from Earth to Mars, the cost of transporting the daily H2O requirement for one astronaut amounts to USD $88 million. In addition, launching a spacecraft from Mars to its orbit requires about 30 tons of liquid methane. To transport this amount from Earth would require sending up to 500 tons of initial payload, at a cost of about eight billion dollars1.

A promising solution to dramatically reduce the need for supplement deliveries from Earth is H2O recycling and in-situ propellant production15,16,17, and the Sabatier reaction (CO2 + 4H2 → CH4 + 2H2O) provides the means10,18. H2O recycled from the Sabatier reaction can be used for drinking and electrolysis, to provide H2 and O2, while the CH4 is the fuel for the return journey19,20,21. Before the introduction of the Sabatier system, H2 produced during the generation of station O2 was considered to be as dangerous an exhaust gas and was vented overboard. This is the same fate for CO2 generated by the crew’s metabolism22,23. With the Sabatier system, these two waste gases are recycled. The initial mass of the spacecraft launched from Earth can be reduced by more than 45% using the Sabatier reaction1,18,24. However, to sustain the conversion of metabolic or Martian atmospheric CO2 into methane, hydrogen is obtained from water electrolysis, which relies on various water sources such as transported supplies from Earth, extraction from Martian regolith, recovery from lunar polar regions, or wastewater recycling in spacecraft and space stations. Additionally, the in-situ H2O collection from the membrane system could provide an extra water source, potentially reducing the overall water demand for completing the methanation cycle.

In 2011, a Sabatier reaction system was integrated into the International Space Station’s H2O recovery system22. The current Sabatier system nevertheless requires a gas–liquid separator to divide liquid H2O from the products22. On Earth, the gas–liquid separation is achieved by gravity settling, but it is not efficient in a microgravity environment (gravitational forces < 10−3 g)25,26. To compensate, in the current space station, a centrifugal force is employed in space to separate liquids from gases22. However, the redesigned rotary separation system inevitably causes energy consumption, mechanical unreliability, and noise pollution27,28,29. It is highly desired to simplify the current Sabatier system with less complexity, less power consumption, and high recovery efficiency. Various strategies have been explored for the selective removal of H2O for increasing CO2 conversion, including the incorporation of water sorbents (powder) into the reactor30,31,32 and the use of water-selective membranes fabricated from organic polymers33,34,35 or inorganic thin films36,37. However, significant challenges remain, particularly in developing membranes with high thermal stability, water resistance, superior water selectivity, and ease of preparation for practical and scalable applications.

Herein, a membrane Sabatier system was developed to separate H2O streams and enhance the activity of the catalyst for CH4 production, according to Le Chatelier’s principle. The working pressure of the system is 1.15 bar. The membrane Sabatier system was designed by integrating a catalytic reactor and an H2O vapor-permselective membrane tube. The ZrO2-supported Ni catalyst was loaded into the catalytic reactor for the Sabatier reaction to convert CO2 and H2 into CH4 and H2O. A NaA zeolite membrane tube was prepared to automatically separate the liquid H2O. The CO2 methanation reaction was enhanced when the by-product H2O was removed in-situ from the catalytic membrane Sabatier system. For example, for the reaction of mixed gas (H2:CO2 = 4:1) with a space velocity of 16,000 mL gcat.−1 h−1, and a temperature of 150 °C, the CO2 conversion with the membrane reactor was 7%, being 3.5 times as high as that (2%) by using a quartz tube. Upon increasing the reaction temperature to 300 °C, the CO2 conversion of the membrane reactor reached 99%, with a CH4 selectivity of 100%, exceeding the thermodynamic equilibrium conversion calculated based on feed conditions. Furthermore, the space-time yield (STY) of CH4 reached 1947 mmol g−1 h−1 with a space velocity of 342,857 mL gcat.−1 h−1 at 300 °C. Moreover, the removal of H2O mitigated H2O-caused sintering of the catalyst. There was no obvious deactivation under a long-term stability test of 10 days, with a space velocity of 12,000 mL gcat.− h−1 at 240 °C. The system’s resilience to an intermittent power supply and its adaptability across a wide range of reaction conditions aligned well with hydrogen production from variable solar energy. Furthermore, the simulated overall energy efficiency of the proposed system was approximately 65%, demonstrating its potential for energy-efficient CH4 synthesis and water recovery in space applications.

The membrane-based Sabatier system in this work integrates reaction engineering and catalysis for water recovery and rocket propellant production, with a strong emphasis on space exploration. Its holistic process design eliminates the need for microgravity-specific adaptations, making it highly versatile for extraterrestrial applications. This innovative concept supports in-situ resource utilization (ISRU) by recovering water for human consumption, producing breathable oxygen for astronauts, and generating hydrogen through water electrolysis to sustain the CO2 methanation cycle. Furthermore, the separation of water prevents water-caused catalyst degradation, significantly prolonging catalyst lifetime and reducing the need for frequent astronaut intervention. By leveraging in-situ water removal, our system enhances single-pass CO2 conversion and improves overall robustness, eliminating the need for bulky auxiliary separation systems. This ensures a compact design, which is particularly beneficial for mini-scale (pilot) and distributed production in space missions. Adopting the catalytic membrane Sabatier system on Mars could produce CH4 as a rocket fuel for return journeys, highlighting its transformative potential for sustainable space missions.

Results and discussion

Synthesis and characterization of the H2O vapor permselective membrane tube

The H2O vapor permselective membrane was prepared by assembling NaA zeolite seeds onto a centimeter-scale ceramic tube (Fig. 1a). The ceramic hollow tube support was 50 mm in length, with an outer diameter of 12 mm, an inner diameter of 8 mm and pores size of 500 nm (Supplementary Fig. 1a). The rough surface of support was beneficial for immobilizing NaA zeolite seeds (Supplementary Fig. 1b). The Al and O elements were homogeneously distributed in a ceramic hollow tube support (Supplementary Figs. 2 and 3). NaA zeolite seeds of 50–200 nm were obtained via a hydrothermal synthesis approach (Supplementary Fig. 4). In addition to Al and O elements, Na and Si elements were shown in the energy-dispersive X-ray (EDX) elemental mapping and EDX spectrum of NaA zeolite seeds (Supplementary Figs. 5 and 6). A seed layer, composed of the prepared nanosized NaA crystals, was coated on the outer surface and in the pores of the ceramic hollow tube support, using a dip-coating method to facilitate the growth of the NaA membrane. The ceramic hollow tube support was briefly blocked at both sides, and heated to 120 °C; it was then dipped into a well-dispersed zeolite seed solution for 20 s. Afterward, the support was carefully withdrawn from the seed solution and dried at 100 °C for 1 h. To affix the zeolite seeds onto the supports, the coated support was annealed at 180 °C for 12 h. The annealing procedure bonded the physically loaded zeolite seeds chemically to the support surface and the inside pores by dehydration of the surface hydroxyl groups38,39.

a Schematic diagram of H2O vapor permseletive membrane over porous alumina surface. b Pathway for transport of gases through H2O vapor permseletive membrane. c Measurement of single gas permeation through the H2O vapor permseletive membrane at different temperatures under 1.15 bar pressure. d Evaluation of water/single-gas separation performance of H2O vapor permseletive membrane at different temperatures under 1.15 bar pressure. e Evaluation of water/mixed-gas separation performance of H2O vapor permseletive membrane as a function of temperature under 1.15 bar pressure.

The bonded zeolite seeds served as the nuclei to induce in-situ growth of the membrane. A synthesis solution with a molar composition of 1Al2O3:5SiO2:50Na2O:1000H2O was used to grow NaA zeolite membranes on the seeded support. Membranes grew on the surface of the seeded supports via crystallization in the synthesis solution at 90 °C for 20 h. At the same time, membranes also grew within the support pores via the zeolite seeds, which penetrated inside the pores. The membrane obtained was confirmed by EDX elemental mapping images and an X-ray diffraction (XRD) profile (Supplementary Figs. 7 and 8a). These two intergrown layers ensured an indistinguishable boundary between the membrane layer and the support (Fig. 1b and Supplementary Fig. 8b, c). The thickness of the membrane was about 5 μm, as characterized by the differential distribution of Na and Si elements in the EDX elemental mapping (Supplementary Fig. 8d–f). The successful preparation of the hydrophilic membrane was further confirmed using a water contact angle measurement (Supplementary Fig. 9).

Evaluating the separation performance of the membrane Sabatier system

We designed a membrane Sabatier system by integrating a Sabatier reactor and an H2O vapor-permselective membrane tube. The single gas blockage performance of the H2O vapor permselective membrane tube was evaluated by using the membrane Sabatier system. In this case, there was no adsorbed H2O in the zeolitic nanochannels. The system consisted of a membrane module, a vertical oven, a mass flow controller, a digital gas bubble flowmeter, and the necessary accessories (Supplementary Fig. 10). The permeation apparatus included two parallel outlets, i.e., the permeate and retentate outlets (Supplementary Fig. 10). The membrane module was constructed by connecting a stainless-steel pipe to one end of the membrane tube, while the other end was sealed with heat-resistant glue (Supplementary Fig. 11). Single-gas (CH4, CO2, CO, and H2 respectively) was fed with various molecular sizes to the permeation apparatus under 1.15 bar. When the permeate outlet was blocked, all feeding gas flowed out from the retentate outlet; the flow rate was recorded using a digital gas bubble flowmeter, denoted as the reference flow rate. When the permeate outlet was opened, permeated gas was released through the membrane tube. The gas flowing out from the retentate outlet was denoted as the retentate flow rate. The permeance amount of each gas was calculated based on the difference between the reference flow rate and the retentate flow rate. The permeance value of CH4, CO2, CO, and H2 was calculated as 2.75 × 10−8, 3.42 × 10−8, 1.97 × 10−8, and 1.07 × 10−7 mol m−2 s−1 Pa−1 at 200 °C, respectively (Fig. 1c and Supplementary Table 1). Enhancement of the gases’ permeance values occurred within a narrow range (10−8–10−7 mol m−2 s−1 Pa−1) when the temperature increased from 200 °C to 450 °C (Fig. 1c). Therefore, the H2O vapor permselective membrane tube of the membrane Sabatier system effectively blocked gas permeation.

To investigate the H2O permeance of the H2O vapor permselective membrane tube, a water trap with silica gel was connected at the end of the permeate outlet. The H2O was introduced through a syringe pump with a carrier gas of Ar (Supplementary Fig. 12). When the permeated H2O was released through the membrane tube, it was trapped by silica gel through physical adsorption and chemical reactions (Supplementary Fig. 13). H2O permeance was determined by measuring the increase in the weight of the silica gel. The value of H2O permeance remained consistent (4.0 × 10−6–4.3 × 10−6 mol m−2 s−1 Pa−1) across the temperature range of 200 °C to 450 °C (Supplementary Fig. 14). The notable H2O permeance (31–33% from 200 to 250 °C) of the membrane tube was attributed to the Na+-gated water-conducting nanochannels, in which the passage of polar H2O molecules was facilitated38.

To explore the effect of adsorbed H2O on gas permeation in the zeolitic nanochannels, single gas (CH4, CO2, CO, and H2, respectively) was co-fed with H2O into the permeation apparatus. The H2O was trapped by silica gel; at the same time, the flow rate of the gases was measured by the gas bubble flowmeter (Supplementary Fig. 15). When binary H2O/gas mixtures were introduced, the permeance value of CH4, CO2, CO, and H2 was calculated as 8.30 × 10−9, 3.14 × 10−8, 2.29 × 10−8, and 1.0 × 10−7 mol m−2 s−1 Pa−1 at 200 °C, respectively (Fig. 1d and Supplementary Table 2). The membrane tube maintained excellent separation performance up to 450 °C (Fig. 1d). Therefore, the H2O vapor permselective membrane tube exhibited good thermal stability and H2O resistance.

A mixture separation measurement was then conducted by co-feeding a gas mixture (H2/CO2/Ar = 76 vol%/19 vol%/5 vol%/) and liquid water (0.2 ml/min). The components of the mixture were controlled by mass flow controllers and a syringe pump (Supplementary Fig. 15). A gas bubble flow meter and water trap (silica gel) were used to determine the amount of permeated gas and water, respectively. The permeance values of the mixed gas and water vapors were calculated as 1.12 × 10−7 and 3.29 × 10−6 at 200 °C, respectively (Fig. 1e and Supplementary Table 3). The permeance ratio of H2O to mixed gas was calculated as 29.4 at 200 °C. This high value of water permeation suggested the effective separation ability of the H2O vapor permselective membrane tube. Furthermore, the permeance value of water in a multicomponent gas mixture is lower than that of its binary mixture with the corresponding individual gases. This effect is attributed to the competitive adsorption and molecular interactions among gas species, which hinder the transport of water vapors through the membrane38,40,41,42,43,44.

Preparation and characterization of the ZrO2-supported Ni catalyst

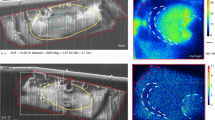

A ZrO₂-supported Ni catalyst (Ni/ZrO₂) was prepared to evaluate the property of the membrane Sabatier system. The fresh Ni/ZrO2 was prepared using the sol–gel method45; a solution of nickel nitrate, zirconyl (IV) nitrate, and citric acid was mixed, and the gel was formed by evaporating the water. The resultant gel was dried and calcined (Supplementary Fig. 16). The calcined sample was reduced under 1.15 bar of H2 with a gas flow rate of 50 mL min−1 at 450 °C for 2 h, identified as reduced Ni/ZrO2. The reduced Ni/ZrO2 revealed abundant pores, as shown in the scanning transmission electron microscopy (SEM) and transmission electron microscopy (TEM) images (Fig. 2a, b). The surface area was 49.4 m2 g−1, based on the Brunauer–Emmett–Teller (BET) method (Supplementary Fig. 17a and Supplementary Table 4). The average mesopore diameter was determined as 4.5 nm using the BJH method (Supplementary Fig. 17b and Supplementary Table 4). The high-resolution transmission electron microscopy (HRTEM) image revealed the interfaces of Ni nanoparticles and ZrO2 support (Fig. 2c). The lattice parameters of 0.203, 0.330, and 0.296 nm were ascribed to Ni (111), monoclinic (m-ZrO2) (011), and cubic ZrO2 (c-ZrO2) (111) facets, respectively. The interfaces between these facets, marked by red lines, were clearly identified. As shown in Fig. 2d–h, Ni, Zr, and O elements are distributed homogeneously, indicating that Ni nanoparticles were highly dispersed over the ZrO2 support. The phase coexistence of m-ZrO2 and c-ZrO2 was further confirmed by the X-ray diffraction (XRD) profile (Fig. 2i). The reduction treatment led to the partial transformation of c-ZrO2 to m-ZrO2 (Fig. 2i and Supplementary Fig. 16).

a–c SEM, TEM, and HRTEM images of reduced Ni/ZrO2. d–h HAADF image and corresponding elemental mapping images of reduced Ni/ZrO2. i X-ray diffraction pattern of reduced Ni/ZrO2. j Ni K-edge XANES spectra (normalized) of reduced Ni/ZrO2 and reference materials. k First derivatives of XANES spectra of reduced Ni/ZrO2 and reference materials.

The electronic structures of reduced Ni/ZrO2 were investigated using X-ray photoelectron spectroscopy (XPS) and X-ray absorption fine structure (XAFS) measurements. The Ni 2p XPS spectrum showed two peaks at 855.2 and 852.3 eV, corresponding to Ni2+ and Ni0, respectively (Supplementary Fig. 18a). The ratio value of Ni0/(Ni0 + Ni2+) was 0.36. The Ni0 2p binding energy (852.3 eV) of reduced Ni/ZrO2 was lower than the bulk Ni0 (853.0 eV) in the literature46, demonstrating that Ni atoms were negatively charged by the transfer of electrons from ZrO2 support at the interface. Based on the Zr 3d XPS spectrum, reduced Ni/ZrO2 contained Zr3+ and Zr4+ species (Supplementary Fig. 18b). As shown in Supplementary Fig. 18c, the O 1s spectrum was deconvoluted into three peaks. The main peak at 529.8 eV was ascribed to the lattice O atoms (Olattice) of ZrO2. The peaks at 531.3 eV were assigned to O atoms proximal to a defect (Odefect), while those at 532.4 eV corresponded to surface hydroxyl groups (OH*)47,48. The electron transfer of Ni atoms with ZrO2 support was further investigated using XAFS measurements. X-ray absorption near-edge spectroscopy (XANES), collected at the Ni K edge, provided the valence states of Ni species. In comparison with XANES and first derivative XANES spectra of Ni foil and NiO, the valence state of Ni in reduced Ni/ZrO2 was determined to be between 0 and +2 (Fig. 2j). The extended XAFS (EXAFS) analysis revealed that the coordination number (CN) of Ni in reduced Ni/ZrO2 was 7.4 (Fig. 2k and Supplementary Table 5). The value was lower than that of Ni particles (12), indicating the good dispersion of Ni species and the strong metal support interactions between Ni species and ZrO2.

Sabatier system evaluation for water recovery and propellant production

We applied membrane Sabatier system to Sabatier reaction for H2O recovery and CH4 production (Fig. 3a and Supplementary Fig. 19). Reduced Ni/ZrO2 was loaded in the region between the membrane tube and the quartz reactor tube (Supplementary Fig. 20). By-product H2O was selectively permeated through the membrane tube (Supplementary Movie 1) and collected by an Erlenmeyer flask under the atmosphere. The driving force required for water permeation through the hydrophilic membrane comes from a concentration gradient created by the in-situ generation of water during CO2 methanation, the strong interaction between the Na⁺ ions of the membrane and the partially negative oxygen atoms (Oδ−) in water, and a partial pressure difference (1.15 bar on the feed side vs. 1 bar on the permeate side) that facilitates water movement into the membrane pores38,49. The catalytic properties of reduced Ni/ZrO2 were operated under 1.15 bar (H2:CO2 = 4:1) with a space velocity of 16,000 mL h−1 gcat.−1 across a temperature range of 150–420 °C. For comparison, the same catalyst was also evaluated by using a quartz tube with the same dimensions to replace the membrane tube. The CO2 conversion of reduced Ni/ZrO2 with membrane tube was 7% at 150 °C, being 3.5 times as high as that (2%), by using a quartz tube (Fig. 3b). Upon increasing the reaction temperature to 300 °C, the CO2 conversion of the membrane reactor reached 99%, exceeding thermodynamic equilibrium conversion (95%) based on the feed conditions (Fig. 3b).

a Role of H2O vapor permseletive membrane in in-situ removal of water during CO2 methanation and its potential applications in space technology. b, c Catalytic CO2 conversion and CH4 selectivity by Ni/ZrO2, inside quartz and membrane reactor (GHSV = 16000 mL gcat.−1 h−1, P = 1.15 bar), respectively. d Long-term catalyst stability, pictorial images of quartz tube, H2O vapor permseletive membrane tube after reaction, and collected water from H2O vapor permseletive membrane during stability test. e Catalytic performance under three times on–off reaction conditions with a 10 h and 1 h each on and off, with H2O vapor permseletive membrane. (Reaction conditions for d and e H2/CO2 = 4/1, GHSV = 12,000 mL gcat.−1 h−1, P = 1.15 bar, T = 240 °C).

The mass balance of water was determined by absorbing the water at both permeate and retentate streams during the CO2 methanation reaction (Supplementary Table 6). Besides, the C-balance calculated from the retentate stream is very close to the C-balance calculated from both retentate and permeate streams, further demonstrating that analyzing the composition of the reaction mixture at the retentate outlet is reasonable (Supplementary Table 7). This enhanced performance was attributed to the effective in-situ H2O removal via the membrane tube, which shifted the equilibrium towards CO2 conversion50. Moreover, the enhanced activity induced the generation of more H2O to react with CO via a water-gas shift reaction, resulting in the increase of CH4 selectivity51. CH4 selectivity with the membrane tube was 100% at 150 °C, higher than the 98% using a quartz tube (Fig. 3c).

In addition to optimal activity and selectivity, long-term stability of the system is crucial for interplanetary exploration. A 10-day stability test of the membrane Sabatier system was performed under 1.15 bar (H2:CO2 = 4:1), with a space velocity of 12,000 mL h−1 gcat.−1 at 240 °C. The CO2 conversion and CH4 selectivity of reduced Ni/ZrO2 with the membrane tube, fluctuated within 1% during the test, indicating the high stability of the system (Fig. 3d). After 10 days on the stream, CH4 selectivity was maintained at 100% and CO2 conversion remained at 96% (Fig. 3d). The catalyst was denoted as used Ni/ZrO2. By using the membrane tube, the porous structure of used Ni/ZrO2 was preserved (Supplementary Fig. 21). In contrast, the CO2 conversion of reduced Ni/ZrO2 with the quartz tube declined continuously (Supplementary Fig. 22). The conversion was 71% after 10 days on the stream, lower than the 78% at the beginning (Supplementary Fig. 22). To investigate the reason for the deactivation, we characterized the used Ni/ZrO2 with a quartz tube. As shown in Supplementary Fig. 23, the Ni nanoparticles were sintered after the reaction. The Ni2+/(Ni0 + Ni2+) value of the used Ni/ZrO2 with the quartz tube was 0.69, higher than the 0.63 with the membrane tube, indicating the oxidation of Ni0 to Ni2 by the side product of H2O (Supplementary Fig. 24 and Supplementary Table 8). The oxidation of Ni nanoparticles was also verified by XAFS spectra (Supplementary Fig. 25). The characterization of reduced Ni/ZrO2 with the quartz tube demonstrated that sintering and Ni oxidation lead to deactivation. The removal of H2O by using the membrane tube therefore mitigated the catalyst deactivation, affording excellent long-term stability.

Another important aspect (particularly for applications involving renewable energy and H2 production in space) is the robustness of the catalyst under complex working conditions52. After the 10-day stability test of the catalyst, working conditions were exposed to alternating states of an on–off power supply to simulate conditions under an unstable solar power supply. As shown in Fig. 3e, after three cycles of intermittent power supply, the catalyst fully recovered its activity without any loss of CO2 conversion and CH4 selectivity. The CH₄ selectivity remained at 100% at a CO2 conversion of 96% under the dynamic conditions. To investigate the robustness of the catalytic membrane Sabatier system, the space velocity was varied and the ratio of H2 to CO2 over reduced Ni/ZrO2 was also varied in the catalytic membrane Sabatier system. When the space velocity increased from 16,000 to 64,000 mL h−1 gcat.−1, the CH4 selectivity exhibited slight variations, while the conversion of CO2 decreased from 100 to 92% at 300 °C (Supplementary Fig. 26). When the ratios of H2 to CO2 decreased from four to two, with the space velocity of 12,000 mL h−1 gcat.−1 at 300 °C, the CH4 selectivity decreased slightly from 100% to 99%, while the conversion of CO2 dropped from 99% to 48% (Supplementary Fig. 27). Therefore, the membrane Sabatier system displayed high robustness and reliability.

To assess the reusability of the catalytic membrane reactor, we examined its performance over multiple reaction cycles by cooling and storing the reactor at room temperature. As shown in Supplementary Fig. 28 and Supplementary Table 9, the CO2 conversion fluctuated between 97% and 96%, exhibiting a 1% decrease over five reaction cycles at 300 °C after cooling the reactor for 1 h at room temperature. We further extend the storage time to 12 h. As depicted in Supplementary Fig. 29 and Supplementary Table 10, the CO2 conversion decreased from 97% in cycle 1 to 94% in cycle 5 at 300 °C after storing the reactor for 12 h at room temperature. Therefore, these results demonstrate an excellent reusability of the membrane reactor.

To investigate the influence of pressure, we designed a stainless-steel reactor for the CO2 methanation reaction (Supplementary Fig. 30). The CO2 methanation was conducted under 10 bar with a space velocity of 16,000 mL h−1 gcat−1 (H2/CO2/N2 = 76%/19%/5%). The CO2 conversion exhibited a notable increase at lower temperatures. For instance, the CO2 conversion with 10 bar pressure was 16%, being 2.2 times as high as that (7%) under 1.15 bar at 150 °C (Supplementary Fig. 31). Upon increasing the reaction temperature to 300 °C, the CO2 conversion of the membrane reactor reached 99% with a CH4 selectivity of 100% under both 1 and 10 bar (Supplementary Fig. 31). Thus, the CO2 conversion was significantly enhanced with the increase in pressure at lower temperatures, while the influence of high pressure became less pronounced at higher temperatures.

To evaluate the impact of impurities like oxygen in the reaction gas mixture, we introduced 0.7% O2 into the reactor along with reaction gas (H2/CO2/N2/O2 = 76%/19%/4.3%/0.7%). This specific concentration of oxygen was selected to ensure safety when heating oxygen in the presence of hydrogen. In the presence of O2, the CO2 conversion started at 150 °C with a value of 3%, peaking at 94% at 300 °C (Supplementary Fig. 32). In the absence of O2, the CO2 conversion started at 150 °C with a value of 7%, reaching a maximum of 98% at 300 °C (Supplementary Fig. 32). Therefore, when the O2 as a possible impurity in the reaction system, the conversion of CO2 showed slight decrease probably due to the in-situ oxidation of Ni.

We tested our membrane Sabatier system for potential use under the condition of many crews, by increasing the space velocity from 4000 to 342,857 mL h−1 gcat.−1 at 300 °C (Fig. 4a and Supplementary Fig. 26). 100% CO2 conversion and 100% CH4 selectivity were achieved at a gas hourly space velocity (GHSV) of 4000 mL h−1 gcat.−1. When the GHSV increased to 16,000 mL h−1 gcat.−1, the CO2 conversion slightly decreased to 99%. The CH4 STY value increased to 1947 mmol g−1 h-1 at a CO2 conversion of 67%, when the GHSV reached 3,42,857 mL gcat.−1 h−1. We compared the results in our work with the performance of both reported membrane Sabatier reactors and traditional reactors from literature in terms of CO2 conversion and CH4 space-time yield (Fig. 4b and Supplementary Table 11). Supplementary Fig. 33 shows a comparison plot without reference labels. Coupling the Sabatier reaction and H2O separation provides added synergy and enhances the performance of both steps33. To our best knowledge, the result obtained on the membrane Sabatier system in this work represents the highest values under similar reactions. This exceptional catalytic performance was attributed to the in-situ H2O removal from the reaction mixture, which enhanced the catalyst efficiency.

a Catalytic activity evaluation of Ni/ZrO2 with H2O vapor permseletive membrane at various GHSVs (T = 300 °C and P = 1.15 bar). b Comparisons of catalytic results in this work with the performance of both reported membrane Sabatier reactors and traditional reactors from literature in terms of CO2 conversion and CH4 space-time yield (Supplementary Table 11). The performance of reported traditional reactors is represented by other symbols (Nos. 1–69). The performance of reported membrane Sabatier reactors is represented by blue stars (Nos. 70–76). The catalytic performance of this work under different gas hourly space velocities and temperatures is represented by red stars (Nos. 77–85).

To evaluate the energy efficiency of methane synthesis through CO2 methanation coupled with water electrolysis on Mars, we give a schematic diagram of a catalytic membrane Sabatier system for space applications (Supplementary Fig. 34). A simulation was performed using Aspen Plus V11. The Peng–Robinson (PR) equation of state method was applied in the simulation53. Given the high concentration of CO2 in the Martian atmosphere, Mars’ air can be utilized directly without further purification. However, due to the low atmospheric pressure on Mars (0.07 bar), multistage compression is required to achieve the pressure necessary for the methanation process. Moreover, the methane product is cooled for cryogenic storage and serves as liquid methane for the rocket.

The water electrolysis and methanation processes were modeled using RStoic reactor models54,55, achieving conversion of 99% for H2O and 99% for CO2. Details of the feed, process conditions, and product specifications are presented in Supplementary Fig. 35. The energy efficiency of the process was evaluated by analyzing the energy inputs and outputs (Supplementary Table 12, Eqs. (8)–(11)). When a feed rate of 132.03 kg CO2/h was applied, 45.98 kg CH4/h was produced with a concentration of 97.08 mol%, corresponding to an energy efficiency of 65%, with 85,152 kJ (23.65 kWh) energy required for producing 1 kg methane.

To address the critical resources for future Mars crewed missions, we compared our membrane-integrated Sabatier system with existing CO2 utilization technologies according to different technology readiness levels (TRL) (Supplementary Table 13). While only the Sabatier process has been applied, our system builds upon it by incorporating a hydrophilic zeolite membrane for passive, gravity-independent water separation, enabling higher CH4 yield, energy-efficient water recovery, and improved system simplicity. Technically, the membrane module is compatible with NASA’s Mars Design Reference Architecture 5.0 and can be retrofitted into existing systems like the International Space Station’s (ISS) Environmental Control and Life Support System (ECLSS) with slight modification. Its water output also supports supplemental O2 generation via electrolysis, enhancing redundancy alongside the Mars Oxygen In-Situ Resource Utilization Experiment (MOXIE). We recommend a hybrid ISRU strategy combining our membrane-Sabatier reactor with other CO2 utilization technologies to co-produce water, oxygen and methane for supporting human missions to space.

In conclusion, a catalytic membrane Sabatier system was fabricated, which not only circumvented the insufficiency of the current Sabatier system, but also achieved a substantial increase in CO2 conversion, a high CH4 yield and excellent long-term stability through highly efficient in-situ water removal. The system achieved a 99% CO2 conversion and 100% CH4 selectivity under 1.15 bar (H2:CO2 = 4:1), with a space velocity of 16,000 mL h−1 gcat.−1 at 300 °C. The space-time yield (STY) of CH4 was as high as 1947 mmol g−1 h−1 under 1.15 bar (H2:CO2 = 4:1) with a space velocity of 342,857 mL h−1 gcat.−1 at 300 °C. The system’s resilience to an intermittent power supply and its adaptability across a wide range of reaction conditions aligned well with hydrogen production from variable solar energy. These findings represent a promising approach to recycling H2O and rocket propellant, suggesting potential application for long-term interplanetary exploration.

Materials and methods

Chemicals and materials

Nickle nitrate Ni(NO3)2⋅6H2O, zirconyl(IV) nitrate hydrate ZrO(NO3)2⋅xH2O, and citric acid (C6H8O7) were obtained from the Sinopharm Chemical Reagent Co., Ltd. Sodium hydroxide (NaOH), tetramethylammonium hydroxide pentahydrate (TMAOH.5H2O, 97 wt%), aluminum isopropoxide (Al(i-C3H7O)3, 98 wt%), Ludox colloidal silica (30 wt% in water), sodium aluminate (NaAlO2) and sodium oxide (Na2O) were purchased from Shanghai Aladdin Biochemical Technology Co., Ltd. The mixed feed gas for reaction was obtained from the Nanjing Special Gas Company. An α-alumina tube with the desired surface properties of 500 nm pore size (porosity = 30%, OD = 12, ID = 8 mm, length = 50 mm) was provided by Jiexi Lishun Technology Co., Guangdong, China, which was used as a support for the NaA membrane. All aqueous solutions were prepared using deionized water with a resistivity of 18.2 MΩ cm.

Methods

Synthesis of NaA zeolite seeds

A controlled hydrothermal synthesis approach was employed to prepare non-ionized NaA zeolite seeds. The prepared zeolite seeds, with a molar composition of 1.8 Al2O3: 11.25 SiO2: 0.6 Na2O: 13.4 (TMA)2O, had particle sizes ranging from 50 to 200 nm. The precursor solution was prepared by dissolving sodium hydroxide (0.4 g), tetramethylammonium hydroxide (41.7 g), and aluminum isopropoxide (6.2 g) in deionized water (76.5 g). This mixture was then stirred vigorously at 900 rpm for 12 h at room temperature. Ludox colloidal silica (18.7 g) was added dropwise to the above solution; stirring continued for 12 h until a clear solution formed. The resulting mixture was transferred to a stainless-steel autoclave and subjected to hydrothermal synthesis at 100 °C for 10 h. After synthesis, the autoclave was cooled to room temperature, and the precipitate was recovered by centrifugation at 9300×g for 30 min. The resulting seeds were washed with deionized water until their pH reached nine and dried overnight at 100 °C.

Synthesis of H2O vapor permselective membrane tube

NaA seed implantation

Non-ionized NaA zeolite seeds were fixed on the external surface of hollow alumina tubes to facilitate membrane synthesis. Before immobilizing the seeds, the tubes were ultrasonically cleaned in deionized water to remove impurities and empty their pores. Both ends of the hollow tubes were sealed with Teflon to prevent seed adhesion on the inner surface. A 1 wt% NaA seed suspension in deionized water (0.3 g/30 mL) was prepared by ultrasonication for 20 min. The hollow alumina tubes, pre-heated at 120 °C for 3 h, were immersed in the seed suspension for 20 s using the hot dip method. The tube was slowly withdrawn from the suspension and heated in an oven at 100 °C for 1 h to facilitate seed adhesion. This procedure was repeated three times, and finally, the tubes were transferred into a preheated oven at 180 °C overnight. The seeded tubes were allowed to cool to room temperature naturally before proceeding to membrane synthesis.

Membrane synthesis

To prepare a defect-free membrane on the surface of the seeded alumina tube, a clear solution with a molar composition of 1Al2O3:5SiO2:50Na2O:1000H2O was prepared by dissolving sodium hydroxide (11.0 g), sodium aluminate (0.2 g), sodium oxide (0.2 g), aluminum oxide (0.2 g) and Ludox colloidal silica 3.1 g) in deionized water (51.2 g). The resultant mixture was vigorously stirred for 12 h at room temperature. After 6 h of aging, the resultant mixture was transferred to an autoclave. A seeded alumina tube, sealed at both ends with a Teflon tap, was positioned vertically in the solution and heated at 90 °C for 20 h. The membrane tubes were then carefully withdrawn from the solution, rinsed with deionized water, and dried overnight in an oven at 60 °C.

Evaluation of water/gas mixture separation ability of H2O vapor permseletive membrane tube

To evaluate the water/gas mixture separation performance of the H2O vapor permseletive membrane tube, an experimental model was constructed as follows: One end of a membraned tube (length: 5 cm) was connected to a stainless-steel pipe (inner diameter: 3 mm, outer diameter: 6 mm, length: 25 cm), while the other end was sealed with a temperature-resistant glue. The function of the stainless-steel pipe was to remove the permeated water from the reactor. The membrane module was then placed in a quartz reaction tube. The quartz reaction tube consisted of an upper inlet to feed the reaction gas mixture and a lower outlet for the escape of retentate species. Finally, the module was fixed inside a vertical oven (CHEMN TFV-1200) to perform the separation experiment at the desired temperature (200–450 °C).

To evaluate the permselectivity of the membrane tube, four different samples (including individual water vapors, single gases, a binary mixture of water/single gas and a mixture of water/mixed-gas) were investigated. The procedure for each permeation experiment follows.

The equation to calculate the permeance is:

Where ni is the mole number of permeated component i, A (m2) is the effective area of the membrane tube (0.000942 m2 in this work), t (s) is the permeation test duration, and ∆pi is the feed and permeate pressure difference of component i.

Single gas permeation

Various single gases (H2, CO, CO2, and CH4, respectively) were passed individually through the membrane tube at 200–450 °C under atmospheric pressure (Supplementary Fig. 10). The flow of each gas at the retentate side was recorded by a digital gas bubble flowmeter (Scale Plus—Electronic Soap Film Flowmeter) and named the reference flow. Finally, the top outlet was opened to allow the permeated gas to escape. The flow rate of the gas was recorded again and termed the retentate flow. The difference in the flow rates between the reference flow and the retentate flow was used to calculate the mole number of permeated gas in Eq. (1).

Water vapor permeation

A syringe pump (longer pump LSP01-1A) was used to supply a constant flow of water (0.2 mL/min) through a capillary tube. A nitrogen gas (50 mL/min) carried water drops towards the membrane tube, which was fixed inside the oven. The temperature of the oven was adjusted to a range of 200–450 °C to facilitate the vaporization of the injected water. Upon contact with the membrane tube, the vaporized water was absorbed and moved toward the permeate outlet of the membrane tube. The permeate outlet of the membrane tube was connected to a pre-weighted silica gel, which acted as a water trap (Supplementary Fig. 12). After a continuous flow of water for 1 h, the silica gel was weighed again. The increase in water trap weight was used to calculate the mole number of permeated water in Eq. (1).

Water/single gas separation measurement

To evaluate the permselectivity of water in the presence of competing gases, both water (0.2 mL/min) and gas (50 mL/min) were passed through the membrane tube (Supplementary Fig. 15). The temperature of the oven was maintained at 200–450 °C. Initially, valves one and two (which controlled the water and gas supply), were opened, while valve three, connected to the permeate outlet, remained closed. The water was absorbed by silica water trap one. The gas flow rate was recorded by a gas bubble flow meter, referred to as the reference flow, representing the initial flow of gas prior to permeation.

Subsequently, valve three was opened, allowing permeated species to exit through the permeate outlet. Permeated water was collected using a silica water trap (two), and quantified using the method described in the Water Vapor Permeation section. The flow of the retentate gas was then recorded by the bubble flow meter, referred to as the retentate flow. The difference between the reference flow and the retentate flow was used to calculate the mole number of permeated gas in Eq. (1), and the increase in water trap weight was used to calculate the mole number of permeated water in Eq. (1).

The permeance ratio of water to gas was calculated according to the following Eq. 2.

Where Pw and Pgas are the permeance values of water and gas, respectively.

Water/mixed-gas separation measurement

A water/mixed-gas mixture (H2O/H2/CO2/Ar = 83 vol%/12.9 vol%/3.2 vol%/0.9 vol%) separation by membrane tube was performed at 200–450 °C. A syringe pump was used to inject water (0.2 mL/min) through a capillary tube into the system, while a controlled flow of the feed gas (50 mL/min) was maintained by a mass flow controller (MFC) (Supplementary Fig. 15). Prior to the introduction of the water/gas mixture, the oven temperature was raised to 200 °C, ensuring the efficient conversion of water droplets into vapor. The procedure and calculation of water and gas permeation are described in Water/single gas separation measurement.

Evaluation of CO2 conversion in the membrane and quartz reactor

The catalytic CO2 conversion to methane was conducted in a fixed-bed membrane reactor at atmospheric pressure. Reaction temperature was maintained in the range of 150–420 °C. Specifically, 0.3 g of Ni/ZrO2 (30–40 mashed) catalyst, diluted with 1.3 g of silica sand, was loaded around the membrane tube in a quartz reactor, which had a 14 mm inner diameter. Before the catalytic reaction, the catalyst was reduced in-situ by passing through pure hydrogen (50 mL/min) at 450 °C for 2 h. After reduction, the membrane reactor was cooled to 420 °C. A pre-mixed gas, including 76.0 vol% H2, 19.0 vol% CO2 and 5.0 vol% Ar (as internal standard), was passed at 80 mL/min flow rate from the catalyst bed.

The permeated water vapors were collected at the permeate outlet of the reactor (the stainless-steel tube was glued to the membrane tube) without purging any gas. For comparison, the methanation reaction was also performed in a quartz reactor, i.e., a non-permeable quartz tube with the same dimensions as a membraned alumina tube. CO2 conversion was calculated according to an external standard method (Eq. 3).

where the CO2 inlet and CO2 outlet were moles of CO2 at the inlet and outlet, respectively. The selectivity of methane was obtained according to Eq. 4:

where nCH4, nC2H6, nC3H8, and nCO represent moles of methane, ethane, propane, and carbon monoxide at the retentate outlet.

The yield of CH4 was calculated by Eq. (5):

Where SCH4 is methane selectivity, XCO2 is CO2 conversion and Catwt. is the weight of the catalyst in the reactor.

Evaluation of catalyst activity through on–off reaction conditions

After a ten-day stability test of the catalyst, the working conditions were exposed to evaluate the reusability of the catalyst through on-off experiments. The feed gas was changed to N2, and the temperature was decreased to 50 °C. After maintaining these conditions for one hour, N2 was switched to the reaction feed gas and the temperature was increased to 240 °C. The test time was 10 h. This procedure was repeated three times, and no change was detected in catalytic activity.

Evaluation of the catalytic membrane reactor reusability

In the first set of experiments, the Ni/ZrO2 was reduced inside the membrane reactor at 450 °C by passing pure hydrogen for 2 h. The CO2 methanation reaction was performed at a temperature range of 150–300 °C (The test was from high temperature to low temperature, i.e., 300, 270, 240, 210, 180, and 150 °C). The test lasted 6 h. After completing one reaction, the reactor was cooled to room temperature under reaction gas atmosphere and was kept at room temperature for 1 h. This entire procedure was defined as “one cycle”. Then, the reactor was heated to 300 °C and began the next cycle of CO2 methanation reaction. This process was repeated for five reaction cycles.

In the second set of experiment, the procedure was similar to the first set of experiment except for the treatment after the reaction. Upon the completing of the CO2 methanation reaction, the membrane reactor was cooled to room temperature and store for 12 h without flowing the reaction gas. This whole procedure was termed as “one cycle”. Before initiating the subsequent cycle, the catalyst was subjected to a reduction process, and the reaction was repeated under identical conditions as cycle 1. This procedure was performed for five consecutive cycles.

High pressure CO2 methanation in H2O vapor permeselective membrane

To evaluate the membrane’s performance at high pressure, we designed a stainless-steel reactor for the CO2 methanation reaction (Supplementary Fig. 30). The H2O vapor permselective membrane module was fixed inside the stainless-steel reactor, with Ni/ZrO2 catalyst packed around the effective area of the membrane tube. Prior to CO2 methanation reaction, the catalyst was reduced by passing pure H2 (50 mL/min) through the system at 450 °C for 2 h. Once the reduction process was complete, the reactor temperature was decreased to 420 °C. A mixed gas feed (H2/CO2/N2 = 76%/19%/5%) was introduced into the reactor from the top inlet, and the pressure was maintained at 10 bar. The pressure of the reactor was adjusted by a back pressure regulator. The reaction products were analyzed online using a gas chromatograph (GC), while the permeated water was collected in the container positioned at the lower end of the reactor.

Evaluation of the catalytic membrane reactor performance in the presence of O2

The catalyst was reduced in the membrane reactor at 450 °C. After cooling the reactor to 420 °C, a feed gas (H2/CO2/N2/O2 = 76%/19%/4.3%/0.7%) was introduced to the reactor with a GHSV of 16,000 mL gcat.−1 h−1. The reaction mixture was analyzed by an online gas chromatograph.

Carbon balance calculation

The carbon balances in permeate and retentate streams were calculated based on the CO2 methanation reaction. Firstly, the composition of the reaction stream in retentate stream were analyzed using an on-line gas chromatograph (GC). Then, we repeated the measurement by combining the retentate and permeate streams and the composition of the reaction stream in both streams were analyzed using an on-line GC.

The carbon balance was calculated based on the following Eq. (6).

Here, CO2 out, CH4 out, CO out, C2H4 out, C3H8 out, CO2 in, and are the concentrations of the corresponding species in the reaction mixture determined by GC analysis. The subscripts ‘out’ and ‘in’ denote the final and initial concentrations, respectively. The numeric coefficient represents the number of carbon atoms in the given compound.

Water balance calculation

To clarify the mass balance of water (Eq. 7), we absorbed the water at both permeate and retentate streams during the CO2 methanation reaction.

Where \({W}_{{{{{\rm{H}}}}}_{2}{{{{\rm{O}}}}}_{{{\mathrm{perm}}}.}}\) and \({W}_{{{{{\rm{H}}}}}_{2}{{{{\rm{O}}}}}_{{{\mathrm{reten}}}.}}\) are the weights of water collected at permeate and retentate streams during CO2 methanation. The mCO2 in, mCO2 out, and mCO out are the molar content of the corresponding species in the reaction mixture determined by GC analysis. \(M{{{{\rm{H}}}}}_{2}{{{\rm{O}}}}\) is the relative molecular mass of H2O.

Energy efficiency calculation of the membrane Sabatier system for space applications

The energy efficiency (η) was calculated using the following Eqs. (8)–(11), shown under Supplementary Table 11

The International Energy Agency (IEA) shows that the standard solar panels produces about 150–200 watts per square meter (W/m2) under standard test conditions. If we use the solar panel with dimension of 2 meters (m) × 1 meter (m), assume the standard solar panels produces 200 watts per square meter (W/m²), consider the solar irradiance on Mars is about 43% of that on Earth, and consider the 12 h of daytime near the equator, the energy produced by one solar panel is 2.06 kWh each day. To get the 23.65 kWh energy required for producing 1 kg methane, ideally, we need 11.5 solar panels.

Instrumentations

The surface morphology and cross-sectional view of the prepared NaA seeds, membrane and Ni/ZrO2 catalysts were viewed on scanning electron microscopy (SEM, Gemini-SEM 360) and energy-dispersive X-ray spectroscopy (EDX, Bruker XFlash 6160). Transmission electron microscopy (TEM) images were acquired using a JEM-2100PLUS instrument. X-ray diffraction profiles of NaA crystals, membrane and Ni/ZrO2 catalysts, were made on a Bruker D8-Discover diffractometer using Cu Kα radiation at 40 kV and 40 mA. To analyze the local electronic structure, an extended X-ray absorption fine structure (EXAFS) and X-ray absorption near edge structure (XANES) spectra were collected at the BL11B beamline of the Shanghai Synchrotron Radiation Facility (SSRF). Specific surface area, total pore volume, and pore size distribution of the catalyst were determined by nitrogen adsorption and desorption isotherms of the samples at −196 °C in a Micromeritics ASAP 2460. The specific surface area of the fresh catalysts was calculated using the Brunauer–Emmett–Teller (BET) method. The total pore volume and pore size distribution of the sample were obtained using the Barrett–Joyner–Halenda (BJH) algorithm. The surface elemental compositions of the Ni/ZrO2 catalysts were examined by X-ray photoelectron spectroscopy (XPS) experiments using a Thermo ESCELAB 250XI instrument equipped with an Al Kα monochromate ray source. To confirm the hydrophilic modification of the support surface by NaA membrane coating, a water contact angle was tested by a water contact angle meter CA-100 (Shanghai Innuo Precision Instruments Co., Ltd., China).

Data availability

The data generated in this study are provided in the Supplementary Information/Source Data file. Source data are provided with this paper.

References

Kruyer, N. S., Realff, M. J., Sun, W., Genzale, C. L. & Peralta-Yahya, P. Designing the bioproduction of Martian rocket propellant via a biotechnology-enabled in situ resource utilization strategy. Nat. Commun. 12, 6166 (2021).

Maiwald, V., Bauerfeind, M., Fälker, S., Westphal, B. & Bach, C. About feasibility of SpaceX’s human exploration Mars mission scenario with starship. Sci. Rep. 14, 11804 (2024).

Overbey, E. G. et al. The space omics and medical atlas (SOMA) and international astronaut biobank. Nature 632, 1145–1154 (2024).

Levchenko, I., Xu, S., Mazouffre, S., Keidar, M. & Bazaka, K. in Mars colonization: beyond getting there. Terraforming Mars 73–98 (2021).

Cockell, C. S. et al. Space station biomining experiment demonstrates rare earth element extraction in microgravity and Mars gravity. Nat. Commun. 11, 5523 (2020).

Soureshjani, O. K., Massumi, A. & Nouri, G. Sustainable colonization of Mars using shape optimized structures and in situ concrete. Sci. Rep. 13, 15747 (2023).

Soureshjani, O. K. & Massumi, A. Martian buildings: structural forms using in-place sources. Sci. Rep. 12, 21992 (2022).

Puumala, M. M., Sivula, O. & Lehto, K. Moving to Mars: the feasibility and desirability of Mars settlements. Space Policy 66, 101590 (2023).

Hajduk, C. in The first settlement of Mars. Terraforming Mars 331–351 (Wiley, 2021).

Tamponnet, C. et al. Water recovery in space. ESA Bull. 97, 56–60 (1999).

Lindeboom, R. et al. A five-stage treatment train for water recovery from urine and shower water for long-term human Space missions. Desalination 495, 114634 (2020).

Globus, A., Covey, S. & Faber, D. Space settlement: an easier way. NSS space.settl. j. (2017).

Scott, J. P., Green, D. A., Weerts, G. & Cheuvront, S. N. Body size and its implications upon resource utilization during human space exploration missions. Sci. Rep. 10, 13836 (2020).

Brown, I. M., Weck, O. L. d., Jordan, K., Charoenboonvivat, Y. & Miller, A. Cost optimized logistics for commercial low earth orbit destinations. AIAA J. 6, 4803 (2024).

Brinkert, K., Zhuang, C., Escriba-Gelonch, M. & Hessel, V. The potential of catalysis for closing the loop in human space exploration. Catal. Today 423, 114242 (2023).

Sheehan, S. W. Electrochemical methane production from CO2 for orbital and interplanetary refueling. iScience 24, 102230 (2021).

Saravanabavan, S., Kaur, M., Coulthard, C. T. & Brinkert, K. in Catalysis in space environments. In-space manufacturing and resources. Ch 7, 141–162 (2022).

Vogt, C., Monai, M., Kramer, G. J. & Weckhuysen, B. M. The renaissance of the Sabatier reaction and its applications on earth and in space. Nat. Catal. 2, 188–197 (2019).

Brooks, K. P., Hu, J., Zhu, H. & Kee, R. J. Methanation of carbon dioxide by hydrogen reduction using the Sabatier process in microchannel reactors. Chem. Eng. Sci. 62, 1161–1170 (2007).

Ye, R.-P. et al. CO2 hydrogenation to high-value products via heterogeneous catalysis. Nat. Commun. 10, 5698 (2019).

Lomax, B. A. et al. Predicting the efficiency of oxygen-evolving electrolysis on the Moon and Mars. Nat. Commun. 13, 583 (2022).

The Sabatier system. NASA. https://www.nasa.gov/missionpages/station/research/news/sabatier.html (2011).

Hwang, H. T., Harale, A., Liu, P. K. T., Sahimi, M. & Tsotsis, T. T. A membrane-based reactive separation system for CO2 removal in a life support system. J. Membr. Sci. 315, 116–124 (2008).

Drake, B. G., Hoffman, S. J. & Beaty, D. W. in Human exploration of Mars, design reference architecture. 2010 IEEE Aerospace Conference pp 1–24 (2010).

Wu, X., Loraine, G., Hsiao, C.-T. & Chahine, G. L. Development of a passive phase separator for space and earth applications. Sep. Purif. Technol. 189, 229–237 (2017).

Wu, C., Wu, P., Huang, B. & Wu, D. in Research on the performance of a passive gas-liquid separator used in space. ASME 2021 Fluids Engineering Division Summer Meeting. 10 (2021).

Yang, L. et al. A review of gas-liquid separation technologies: Separation mechanism, application scope, research status, and development prospects. Chem. Eng. Res. Des. 201, 257–274 (2024).

Pingel, A. & Dreyer, M. E. Phase separation of liquid from gaseous hydrogen in microgravity experimental results. Microgravity Sci. Technol. 31, 649–671 (2019).

Ahn, H., Tanaka, K., Tsuge, H., Terasaka, K. & Tsukada, K. Centrifugal gas–liquid separation under low gravity conditions. Sep. Purif. Technol. 19, 121–129 (2000).

Walspurger, S., Elzinga, G. D., Dijkstra, J. W., Sarić, M. & Haije, W. G. Sorption enhanced methanation for substitute natural gas production: experimental results and thermodynamic considerations. Chem. Eng. J. 242, 379–386 (2014).

Borgschulte, A. et al. Sorption enhanced CO2 methanation. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 15, 9620–9625 (2013).

Agirre, I., Acha, E., Cambra, J. & Barrio, V. Water sorption enhanced CO2 methanation process: Optimization of reaction conditions and study of various sorbents. Chem. Eng. Sci. 237, 116546 (2021).

Kim, E.-Y. et al. Selective in-situ water removal by polybenzoxazole hollow fiber membrane for enhanced CO2 methanation. Chem. Eng. J. 487, 150206 (2024).

Lee, J. et al. Low-temperature CO2 hydrogenation overcoming equilibrium limitations with polyimide hollow fiber membrane reactor. Chem. Eng. J. 403, 126457 (2021).

Escorihuela, S. et al. Intensification of catalytic CO2 methanation mediated by in-situ water removal through a high-temperature polymeric thin-film composite membrane. J. CO2 Util. 55, 101813 (2022).

Liu, Z., Bian, Z., Wang, Z. & Jiang, B. A CFD study on the performance of CO2 methanation in a water-permeable membrane reactor system. React. Chem. Eng. 7, 450–459 (2022).

Ohya, H. et al. Methanation of carbon dioxide by using membrane reactor integrated with water vapor permselective membrane and its analysis. J. Membr. Sci. 131, 237–247 (1997).

Li, H. et al. Na+-gated water-conducting nanochannels for boosting CO2 conversion to liquid fuels. Science 367, 667–671 (2020).

van Kampen, J., Boon, J., van Berkel, F., Vente, J. & van Sint Annaland, M. Steam separation enhanced reactions: Review and outlook. Chem. Eng. J. 374, 1286–1303 (2019).

Hyeon, M.-H. et al. Equilibrium shift, poisoning prevention, and selectivity enhancement in catalysis via dehydration of polymeric membranes. Nat. Commun. 14, 1673 (2023).

Zito, P. F., Brunetti, A., Drioli, E. & Barbieri, G. CO2 separation via a DDR membrane: mutual influence of mixed gas permeation. Ind. Eng. Chem. Res. 59, 7054–7060 (2019).

Zito, P. F., Brunetti, A., Caravella, A. & Barbieri, G. H2 permeation and its influence on gases through a SAPO-34 zeolite membrane. Int. J. Hydrog. Energy 48, 12036–12044 (2023).

Huang, S. et al. Single-layer graphene membranes by crack-free transfer for gas mixture separation. Nat. Commun. 9, 2632 (2018).

Zhu, W. et al. Water vapour separation from permanent gases by a zeolite-4A membrane. J. Membr. Sci. 253, 57–66 (2005).

Ye, R. et al. Boosting low-temperature CO2 hydrogenation over Ni-based catalysts by tuning strong metal-support interactions. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 63, e202317669 (2024).

Ni, J. et al. Tuning electron density of metal nickel by support defects in Ni/ZrO2 for selective hydrogenation of fatty acids to alkanes and alcohols. Appl. Catal. B 253, 170–178 (2019).

Romero-Sáez, M. et al. CO2 methanation over nickel-ZrO2 catalyst supported on carbon nanotubes: A comparison between two impregnation strategies. Appl. Catal. B 237, 817–825 (2018).

Carrasco, J. et al. In situ and theoretical studies for the dissociation of water on an active Ni/CeO2 catalyst: Importance of strong metal–support interactions for the cleavage of O–H bonds. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 54, 3917–3921 (2015).

Mulder, M. Basic Principles of Membrane Technology. (Springer Science & Business Media, 2012).

Yue, W. et al. Highly selective CO2 conversion to methanol in a bifunctional zeolite catalytic membrane reactor. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 60, 18289–18294 (2021).

Wu, W. et al. CO2 hydrogenation over Copper/ZnO single-atom catalysts: water-promoted transient synthesis of methanol. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 61, e202213024 (2022).

Junaedi, C. et al. in Compact and lightweight Sabatier reactor for carbon dioxide reduction. 41st International Conference on Environmental Systems (Aerospace Research Center, 2011).

Uddin, Z., Yu, B.-Y. & Lee, H.-Y. Evaluation of alternative processes of CO2 methanation: Design, optimization, control, techno-economic and environmental analysis. J. CO2 Util. 60, 101974 (2022).

Lonis, F., Tola, V. & Cau, G. Assessment of integrated energy systems for the production and use of renewable methanol by water electrolysis and CO2 hydrogenation. Fuel 285, 119160 (2021).

Zhang, C. et al. Direct conversion of carbon dioxide to liquid fuels and synthetic natural gas using renewable power: techno-economic analysis. J. CO2 Util. 34, 293–302 (2019).

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by the National Key Research and Development Program of China (2019YFA0405602 to Z.W.), National Key Research and Development Program of China (2025YFE0106800 to W.W.), the National Natural Science Foundation of China (22204158 to W.W.), Anhui Provincial Science Foundation for Excellent Young Scholars (2408085Y007 to W.W.).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Z.W. conceived the idea and designed the experiments. I.U. performed the materials synthesis, characterizations and experiments. J.R. and H.L. assisted in the design of the membrane reactor, performing the experiment and arranging data. F.Z. performed the energy efficiency calculation of the membrane Sabatier system. Z.A. and S.M.A. helped in analyzing the XAS data. I.U., W.W., and Z.W. wrote the paper. Z.W. supervised and directed all aspects of the project. All authors discussed the results and commented on the paper.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Peer review

Peer review information

Nature Communications thanks Jurriaan Boon, Volker Hessel, and the other, anonymous, reviewer(s) for their contribution to the peer review of this work. A peer review file is available.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Source data

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Ullah, I., Ren, J., Zeng, F. et al. A membrane Sabatier system for water recovery and rocket propellant production. Nat Commun 16, 8624 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-025-63667-w

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-025-63667-w