Abstract

Advancing safe and efficient natural gas storage solutions is essential for ensuring a stable gas supply and strengthening global energy resilience. In this study, we developed amino acid-modified ice (AM-Ice) for solidified natural gas (SNG) applications. The optimized AM-Ice clathrate system achieved a methane storage capacity of 146.56 v/v with an uptake rate of 3.22 v/v s−1 and 90% of the reaction completed within just 2.42 min. Compared to the unmodified ice baseline, this represents a 30-fold increase in storage capacity and a 29-fold enhancement in reaction kinetics. In situ Raman spectroscopy unveiled time-dependent methane occupancy at the molecular level within both 512 and 51262 cages of the sI clathrate. We conducted an assessment of the effects of amino acid concentration, diversity, pressure, temperature, and scalability on hydrate formation in AM-Ice. Unlike conventional surfactants, amino acids facilitated rapid methane recovery through heat stimulation while effectively mitigating foam formation.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The Paris Agreement1 and the COP26 initiatives2 to phase down coal power and reduce fossil fuel subsidies have accelerated the global shift toward energy sources with lower carbon dioxide emissions. As nations strive to meet their climate commitments, transitioning from high-carbon to cleaner fuels is crucial3. Natural gas—whether extracted from underground reservoirs4 or derived from the anaerobic digestion and thermal gasification of organic matter5—has garnered growing interest for its potential to mitigate CO2 emissions, thereby driving increased demand6. The latter form, known as biomethane, serves as a renewable and sustainable alternative to conventional fossil-based natural gas7. To fully harness the environmental and economic advantages of natural gas, the development of efficient, safe, and scalable storage and transportation technologies is imperative to address current limitations and operational risks8,9. These solutions should prioritize sustainability and play a key role in enhancing global energy security.

Solidified Natural Gas, leveraging clathrate hydrate technology offers superior natural gas storage capacity, while operating under relatively mild temperature and pressure conditions compared to conventional methods10,11,12. Moreover, its intricate cage-like structure facilitates a gradual gas release, significantly mitigating explosion risks10,13,14,15. These hydrates exhibit exceptional thermodynamic stability, retaining their structural integrity even at or above the freezing point of water with the assistance of promoters13,16. As a result, SNG technology emerges as a cost-effective and scalable solution for both efficient gas storage material synthesis and long-term energy storage17,18,19.

Hydrate-based natural gas storage is typically performed in bulk solution systems, with various enhancements aimed at improving gas-liquid contact and thereby increasing hydrate formation kinetics20. These enhancements include advancements in reactor design21, the use of porous materials22,23,24,25, dry water26,27, and chemical promoters28,29,30,31,32. Amino acids have emerged as dual-function modulators in the field of hydrate research, capable of exhibiting either inhibitory or promotive effects on hydrate formation depending on their physicochemical properties and system-specific conditions. Glycine, alanine, and histidine—especially when used at relatively high concentrations (>0.5 wt%)—have been investigated primarily as kinetic inhibitors of hydrate formation33,34,35. The observed inhibition may stem from these amino acids’ hydrophilic characteristics to perturb the hydrogen-bonding network of water and, in some cases, their potential incorporation into the hydrate lattice via hydrogen bonding, thereby compromising lattice integrity and impeding the nucleation and propagation of an ordered crystalline structure33,36. In contrast, tryptophan and methionine have emerged as kinetic promoters, with their hydrophobic interactions with water molecules and methane gas, promoting faster hydrate growth and increased gas uptake37. Tryptophan has demonstrated the ability to facilitate complete hydrate formation within just 15 min under conditions of 283 K and 7.2 MPa11,12. Despite these advancements, the efficiency of hydrate formation in bulk aqueous systems remains limited by challenges in gas–liquid–solid contact and heat accumulation during the exothermic formation process.

Researchers have identified active ice as a promising approach to overcoming the limitations of methane storage capacity and hydrate formation rate38,39. Active ice is a medium obtained by decomposing methane hydrate, which is pre-synthesized from a surfactant solution below the ice point. This technique effectively balances the exothermic heat released during hydrate formation with the endothermic process of ice melting38. Additionally, the porous structure of active ice provides a large gas-liquid-solid interfacial area, enabling nearly complete hydrate formation within just 5 min with maximum gas uptake38. Subsequent studies have further elucidated the microscopic mechanism driving this enhancement: hydrate nucleation preferentially occurs in the sodium dodecyl sulfate (SDS)-enriched unfrozen layer (termed “active water”), where methane diffusion and localized heat transfer are optimized40,41. Molecular dynamics simulations revealed that SDS disrupts the ordered ice surface and accelerates mass transfer, facilitating cage nucleation at ice–water interfaces41. While initial studies focused on a narrow temperature range near the ice point (273.15–271.65 K)38, recent advances have broadened the operational range down to 266.15 K by tuning gas injection modes, particle sizes, and pressure-temperature conditions39. However, this method relies on surfactants like sodium dodecyl sulfate, which are non-biodegradable and pose environmental concerns if not properly managed. Furthermore, surfactants can cause excessive foaming, complicating gas-liquid separation and reactor operation, particularly in large-scale systems.

Herein, we explore the use of amino acids as an alternative for modifying ice without requiring the hydrate formation and dissociation cycle, leading to the development of amino acid-modified ice. This AM-Ice is then directly exposed to methane gas, achieving enhanced methane storage capacity and formation kinetics. The study integrates both macro-scale investigations of hydrate formation kinetics and morphological characteristics, alongside micro-scale analyses using in-situ Raman spectroscopy and X-ray diffraction (XRD). This approach enables gas storage with biodegradable promoters, eliminating foam formation during gas recovery. Our findings establish a foundational framework for advancing a green AM-Ice based SNG technology, reinforcing the feasibility of sustainable natural gas storage.

Results

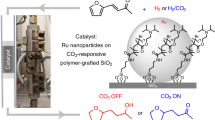

Amino acid-modified ice powder exhibits an enhanced rate and capacity for methane storage under moderate pressure conditions. The ice fabrication process entails freezing liquid water infused with tryptophan (an amino acid) to form bulk ice, which is then transformed into a fine powder through mortar and pestle grinding, as depicted in Fig. 1a and Supplementary Fig. 1. Under identical conditions of 272.7 K and 6 MPa, the tryptophan AM-Ice powder exhibits methane gas uptake of 146.56 ± 5.72 v/v (volume of gas at standard temperature and pressure (STP)/volume of ice) and hydrate formation rate of 3.22 ± 0.10 v/v s−1 with a t90 (time required to complete 90% gas uptake) of just 2.42 ± 0.64 min (see Fig. 1b and Supplementary Table 1). Conversely, pure water-based ice powder showed a negligible gas storage capacity of only 4.80 ± 0.78 v/v over a 20-min reaction period, with a hydrate formation rate of 0.11 ± 0.01 v/v s−1, as presented in Fig. 1b and Supplementary Table 1. These results correspond to a 30-fold enhancement in methane storage capacity and a 29-fold increase in formation kinetics achieved by the tryptophan AM-Ice system. The gas uptake curves presented in Fig. 1b have been averaged across three measurements along with the error bars to illustrate the reproducibility and reliability of the results.

a The fabrication of AM-Ice involves three key steps: 1) mixing a specific amount of amino acids with water, 2) freezing the solution to form ice, and 3) grinding the bulk ice into a fine powder using a mortar and pestle. b The gas uptake (volume of gas at STP per volume of ice, v/v) of tryptophan AM-Ice with 3000 ppm tryptophan is compared with that of pure water-based (non-modified) ice. Each error bar reflects the standard deviation from three individual measurements. c The morphological evolution during hydrate formation from tryptophan AM-Ice. Both systems were tested under identical conditions of 272.7 K and 6 MPa.

In an AM-Ice promoted system, the injection of methane gas triggers substantial morphological changes in the ice powder. The powder transitions from its initial state to a white form, signaling the high-energy-density storage of methane gas. This structural change occurs rapidly, within 30 s (as shown in Fig. 1c), and is accompanied by a pronounced expansion of the synthesized solid hydrate. The rise in the reactor’s internal temperature during methane gas injection caused partial melting at the surface of the ice powder, forming a liquid layer on its exterior, as shown in Fig. 2a and Supplementary Fig. 2. This observation aligns with findings for SDS-modified ice, where research indicates that hydrate formation involves the development of a liquid layer on the ice powder’s surface38. Furthermore, the heat generated by the exothermic reaction of hydrate formation can induce internal melting of the ice, suggesting that the rapid reaction may involve a sequence of transformations: from ice to a liquid water layer, and subsequently to methane hydrate. Tryptophan promotes the formation of porous methane hydrate with interconnected pathways, enabling methane molecules to adsorb onto newly formed gas-liquid-solid interfaces12,37, as illustrated in Fig. 2a. Additionally, tryptophan possesses a high hydrophobicity to strengthen local water structure and is less likely to be abnormally incorporated into the hydrate crystal lattice, thereby preserving lattice integrity and facilitating rapid crystallization33,36,42. The above process enhances the hydrate formation rate and improves methane storage efficiency. In contrast, pure water-based (non-modified) ice powder forms a thin, compact hydrate film on its surface (see Fig. 2b and Supplementary Fig. 3), consequently creating a barrier to mass transfer. This hydrate film hinders methane diffusion, thereby limiting ice-to-methane hydrate conversion.

Both tryptophan AM-Ice and non-modified ice are hexagonal ice (ice Ih), as confirmed by the PXRD patterns in Fig. 3a, indicating that tryptophan does not alter the ice structure. Meanwhile, the methane hydrate synthesized from tryptophan AM-Ice exhibits a structure of sI clathrates, as shown in Fig. 3b. The Raman spectra of methane hydrates derived from both non-modified ice system and tryptophan AM-Ice system are shown in Fig. 3c. With the O-H stretching of water remaining constant, methane molecules exhibit negligible intensity in non-modified ice system compared to tryptophan AM-Ice system, further supporting gas uptake results discussed earlier in Fig. 1b. Raman peak deconvolution analysis of methane hydrate synthesized with tryptophan AM-Ice reveals distinct vibrational modes for methane molecules. As shown in Fig. 3d, a strong absorption band at 2903.1 cm⁻¹ indicates methane resides in the 51262 cage, while a characteristic absorption at 2914.4 cm⁻¹ corresponds to methane in the 512 cage. The Raman spectra are obtained at atmospheric pressure, free from signal interference caused by methane gas. The peak area ratio of large to small cages is found to be 3.09. The thermodynamic equation below illustrates the relationship between chemical potential and cage occupancy in sI hydrate43,44,45.

Where ∆µw represents the chemical potential of the empty hydrate lattice relative to ice, with a value of 1297 J/mol. R is the universal gas constant (8.314 J/(K mol)), and T denotes the experimental temperature in Kelvin. The fractional occupancies of the large and small cages are given by θl and θs, respectively. By using the ratio of large to small cages obtained from the Raman spectra and the thermodynamic equation, we determine the absolute methane cage occupancy in the 512 and 51262 cages to be 94.1% and 96.8%, respectively. The result implies that large cages contribute more significantly to the stability of the hydrate structure than small cages.

a PXRD pattern of ice made from pure water and 3000 ppm tryptophan solution (tryptophan AM-Ice). The International Centre for Diffraction Data entry (ICDD ID: 00-042-1141), corresponding to Ice Ih, is included for comparison. b PXRD pattern of methane hydrate synthesized using tryptophan AM-Ice (3000 ppm tryptophan). The Crystallography Open Database entry (COD ID: 96-901-2469), representing sI hydrate, is included for comparison. c Raman spectra of methane hydrate synthesized from tryptophan AM-Ice (3000 ppm tryptophan) and non-modified ice. The Raman spectra are obtained at atmospheric pressure, free from signal interference caused by methane gas. The yellow rectangle highlights the C–H stretching region of CH4, while the gray rectangle indicates the O–H stretching region of H2O. d Peak fitting and deconvolution for the Raman spectra obtained for methane gas at 6 MPa and methane hydrate synthesized from tryptophan AM-Ice (3000 ppm tryptophan).

The in-situ Raman study was conducted using tryptophan AM-Ice to gain insights into the dynamic cage occupancy of methane hydrate. The experimental sample layout is shown in Fig. 4a, where the Raman probe is immersed in AM-Ice to minimize interference from methane gas signals. However, the presence of micropores or void spaces in the tightly packed AM-Ice sample inevitably results in the detection of methane gas signals upon gas injection into the reactor, as shown in Fig. 4b. Although the methane gas signal may overlap with methane in the 512 cage, the methane signal in the 51262 cages is distinct from that of methane gas, as demonstrated in Fig. 3d. During the in-situ Raman experiment, methane signals in the 51262 cages were identified approximately 16 s after gas injection as shown in Fig. 4b, c, indicating the initial structural transformation from tryptophan AM-Ice to AM-Ice clathrates. Methane intensity within both the 512 and 51262 cages increased rapidly from 16 to 72 s, after which the methane signals in both the 51262 and 512 cages stabilized. The time-dependent Raman spectra analysis further confirms the rapid formation of methane clathrate, as discussed earlier.

a Illustration of the experimental setup for in-situ Raman experiments, where the Raman probe is immersed in the tryptophan AM-Ice sample. b Time dependent Raman spectra obtained during methane hydrate formation with tryptophan AM-Ice under 272.7 K and 6 MPa. c Plot of area under the peak for CH4 in 51262, and the peak for both CH4 in 512 and CH4 gas. The ratio between the two peak areas is also presented. Error bars indicate the fitting error associated with peak deconvolution. The CH4 peak at 512 in the hydrate phase and CH4 gas peak are indistinguishable, given the resolution of the Raman setup.

In the sI clathrate crystal structure, the ratio of large to small cages is 3. Therefore, the peak area ratio of CH4 in 51262 to CH₄ in 512 should ideally approach 3, which aligns with observations after 72 s, as shown in Fig. 4c. However, the initial peak area ratio increased rapidly from 0.41 ± 0.06 to 2.86 ± 0.25 between 16 and 72 s. This appears to suggest an initially higher occupancy of small cages compared to large cages, which contradicts our previous findings that absolute cage occupancy analysis confirms slightly greater methane occupancy in large cages than in small cages. A plausible explanation for this initial deviation from the expected ratio of 3 is the strong interference from methane gas signals affecting the 512 cage region. As hydrate formation progresses, methane signals from the hydrate phase become dominant, while interference from free methane gas diminishes, resulting in a more reliable signal for methane in the 512 cage.

The methane storage performance of tryptophan AM-Ice was evaluated by varying tryptophan concentrations from 300 ppm to 5000 ppm. The gas uptake profile, including the standard deviation, is presented in Fig. 5a, and the corresponding t90 data are summarized in Supplementary Table 1. At the lowest concentration of 300 ppm, tryptophan significantly enhanced gas uptake to 125.05 ± 6.59 v/v and accelerated the hydrate formation rate (R30) by nearly tenfold (from 0.11 ± 0.01 to 1.07 ± 0.19 v/v s−1) compared to the non-modified ice system. Increasing the concentration to 1000 ppm further improved the storage capacity to 131.50 ± 5.76 v/v and enhanced R30 to 1.97 ± 0.14 v/v s−1. At 3000 ppm, the methane storage capacity reached 146.56 ± 5.72 v/v, accompanied by a rapid formation rate (R30) of 3.22 ± 0.10 v/v s−1 and a t90 of just 2.42 ± 0.64 min. At 5000 ppm, the storage capacity was 145.24 ± 3.43 v/v, R30 was 3.15 ± 0.04 v/v s−1, and t90 was 2.65 ± 0.27 min. The gas uptake curves for both 3000 ppm and 5000 ppm concentrations were nearly identical, suggesting comparable kinetic performance. However, the efficiency analysis revealed that the tryptophan concentration of 3000 ppm required only 60% of the amount needed at 5000 ppm, establishing 3000 ppm as the optimal concentration for fabricating tryptophan AM-Ice.

a The gas uptake during hydrate formation from tryptophan AM-Ice with various concentrations of tryptophan (300, 1000, 3000, 5000 ppm), as well as from pure water. Each system is tested under 272.7 K and 6 MPa. Each error bar reflects the standard deviation from three individual measurements. b The gas uptake and t90 for tryptophan AM-Ice (3000 ppm tryptophan) obtained for different masses of 10, 20, and 30 g. The inset presents t₉₀ values observed in the three systems. Each system is tested under 272.7 K and 6 MPa. Each error bar reflects the standard deviation from three individual measurements. c The gas uptake and t90 for tryptophan AM-Ice (3000 ppm tryptophan) obtained under different pressures (4, 5 and 6 MPa) at 272.7 K. The inset presents t₉₀ values observed in the three systems. Each error bar reflects the standard deviation from three individual measurements. d The gas uptake and t90 for tryptophan AM-Ice (3000 ppm tryptophan) obtained under different temperatures (271.2, 272.2 and 272.7 K) at 6 MPa. The inset presents t₉₀ values observed in the three systems. Each error bar reflects the standard deviation from three individual measurements.

To investigate the scalability of this method, we increased the sample mass from 10 g to 30 g, with the results shown in Fig. 5b and Supplementary Table 2. This study employed a batch reactor mode, wherein no additional methane gas was introduced after the initial injection. The increase in sample mass resulted in a decrease in methane gas volume, as the larger ice mass occupied more space. Methane gas uptake decreased from 146.56 ± 5.72 v/v for the 10 g sample, to 139.24 ± 0.85 v/v for the 20 g sample, and 133.09 ± 4.23 v/v for the 30 g sample. Concurrently, the t90 values increased from 2.42 ± 0.64 min for the 10 g sample, to 4.00 ± 0.87 min for the 20 g sample, and 7.63 ± 1.93 min for the 30 g sample. In systems with larger ice masses, the reduction in reactor pressure became more pronounced, leading to a diminished driving force for hydrate formation compared to systems with smaller samples. To sustain optimal kinetic performance while scaling up the sample mass, an effective strategy would be to maintain constant pressure during the experiments and to innovate on process reactor design that can enable efficient gas–liquid–solid contact throughout the hydrate formation process.

To evaluate the pressure and temperature operating ranges of this AM-Ice-based method, we investigated methane hydrate formation using tryptophan AM-Ice (3000 ppm tryptophan) at three pressures (6 MPa, 5 MPa, and 4 MPa) and three temperatures (272.7 K, 272.2 K, and 271.2 K). As the pressure decreased from 6 MPa to 4 MPa, the final gas storage capacity remained relatively constant within the margin of error (see Fig. 5c and Supplementary Table 3). However, the t90 increased from 2.42 ± 0.64 min at 6 MPa to 4.11 ± 0.64 min at 5 MPa and 4.64 ± 0.73 min at 4 MPa, highlighting the enhanced driving force at higher pressures that accelerates hydrate formation and reduces t90. Temperature had a more subtle effect on the hydrate formation, with t90 remaining largely unchanged across the three temperatures (see Fig. 5d and Supplementary Table 4). Nonetheless, at 272.7 K, we observed the fastest formation rate (R30 of 3.22 ± 0.10 v/v·s−1), while 272.2 K led to the highest gas uptake (149.59 ± 1.52 v/v). Li et al.39 demonstrated that while the operational temperature window of active ice-based systems can be extended from 273.15 K to 266.15 K, both the hydrate formation rate and gas uptake decline at lower temperatures. Moreover, operating at such reduced temperatures imposes a substantial energy penalty, especially when considering large-scale deployment reliant on a cold energy supply. Thus, optimizing the process at temperatures just below the freezing point of water is essential to maximize performance while minimizing overall energy consumption. To summarize, the four optimized parameters identified for achieving high-performance methane hydrate formation using AM-Ice are: tryptophan concentration of 3000 ppm, sample mass of 10 g, pressure of 6 MPa, and temperature of either 272.7 K or 272.2 K, as shown in Fig. 5d and Supplementary Table 4.

We also evaluated methane storage performance using AM-Ice synthesized with various amino acids, including methionine, leucine, arginine, and histidine. The results, shown in Fig. 6 and Supplementary Table 5, reveal that both methionine and leucine significantly enhanced hydrate formation kinetics and gas uptake, whereas arginine and histidine were less effective. Specifically, the final methane storage capacity achieved was 150.17 ± 5.52 v/v for the methionine system, 143.41 ± 5.30 v/v for the leucine system, 37.81 ± 10.97 v/v for the arginine system, and 19.48 ± 10.27 v/v for the histidine system. The corresponding t90 and R30 values were 3.63 ± 0.38 min and 2.15 ± 0.07 v/v s−1 for the methionine system, 6.84 ± 1.79 min and 2.10 ± 0.09 v/v s−1 for the leucine system, 13.76 ± 1.85 min and 0.58 ± 0.11 v/v s−1 for the arginine system, and 7.78 ± 4.82 min and 0.36 ± 0.18 v/v s−1 for the histidine system. The key distinction likely stems from the structural properties of these amino acids: histidine and arginine are hydrophilic, whereas tryptophan, methionine, and leucine exhibit hydrophobic characteristics42. Previous studies have shown that hydrophilic amino acids, such as arginine and histidine, have a weaker impact on nucleation time and gas uptake for pure methane hydrate formation from liquid water46. This is attributed to their hydrophilic, charged side chains, which disrupt the structure of liquid water. In contrast, hydrophobic amino acids, including tryptophan, leucine, and methionine, enhance hydrate formation rates and gas storage capacities by introducing hydrophobic regions within the solution, thereby promoting local water ordering37. An interesting phenomenon observed is that the amino acids, which are known to enhance methane hydrate formation in liquid solutions, also work effectively with the ice method employed in this study, and vice versa. This observation further corroborates our previous discussion that the conversion of AM-Ice to methane hydrate involves a sequence of transformations: from AM-Ice to a liquid water layer, followed by the formation of methane hydrate. Similar to their function in the liquid phase, amino acids are likely to play a crucial role in promoting hydrate formation within the liquid water layer in the AM-Ice-based method.

a Illustration of the molecular structure of tryptophan, methionine, leucine, arginine, and histidine. Red, blue, yellow, gray, and white spheres represent oxygen, nitrogen, sulfur, carbon, and hydrogen atoms, respectively. b The gas uptake obtained during hydrate formation from non-modified ice and AM-Ice synthesized with various amino acids at a concentration of 3000 ppm. Each error bar reflects the standard deviation from three individual measurements. Each system was tested under identical conditions of 272.7 K and 6 MPa.

Methane gas recovery was conducted for the tryptophan AM-Ice system at three temperatures, namely, at sub-zero temperatures (272.2 K) and two above-zero temperatures (275.0 K and 278.1 K) as shown in Fig. 7. At the sub-zero temperature, only 77.2% was recovered after 1 week. However, 100% of the methane gas could be recovered within 1h when the recovery temperature was increased to 275.0 K. Further increasing the temperature to 278.1 K enabled complete recovery of methane gas consistently within 30 min (see Supplementary Fig. 4).

a Methane recovery profiles from methane hydrate at sub-zero (272.2 K) and above-zero temperatures (275.0 K and 278.1 K). b Methane recovery profiles from methane hydrate during the first hour at three different temperatures. Methane hydrate was synthesized using tryptophan AM-Ice with a tryptophan concentration of 3000 ppm under 272.7 K and 6 MPa.

We also tested the methane storage performance of SDS-modified ice in order to understand the energy recovery characteristics in comparison with the AM-Ice system. The gas uptake characteristics presented in Supplementary Fig. 5 (the experimental results tabulated in Supplementary Table 6) yielded a final methane storage capacity of 143.11 ± 2.68 v/v, an R30 of 3.16 ± 0.11 v/v s−1, and a t90 of 2.94 ± 1.38 min, consistent as reported in previous studies38. Supplementary Fig. 6 illustrates the methane recovery performance of SDS-modified ice (active ice) at one sub-zero temperature (272.2 K) and two above-zero temperatures (275.0 K and 278.1 K). After 1 week at 272.2 K, only 74.8% of the stored methane was recovered. In contrast, elevating the temperature to 275.0 K enabled complete gas recovery within 1h , while a further increase to 278.1 K shortened the full recovery time to 30 min.

These results highlight the necessity of heat stimulation for efficient methane recovery in practical applications of the ice-based clathrate method. However, one significant drawback of the SDS-modified ice system is the formation of foam during methane recovery (see Supplementary Fig. 7). The foam formation is an intractable challenge in the SDS-containing system during gas recovery operations47. Foam formation complicates the gas recovery process, as it can lead to blockages in recovery lines, decrease the efficiency of the recovery process, and necessitate additional steps to separate the foam from the gas in large-scale operations. This not only affects overall system performance but also drives up operational costs.

In contrast, AM-Ice, such as tryptophan AM-Ice, does not experience foam formation during methane recovery (see Supplementary Fig. 8), making it a more efficient option for large-scale methane storage and recovery systems. Furthermore, amino acids are environmentally benign and biodegradable chemicals, making them ideal for developing green energy storage and transportation systems.

Discussion

Compressed Natural Gas and Liquefied Natural Gas (LNG) are commercially available technologies applied at different scales for the specific needs of storage and transport. Each of these approaches present significant challenges to adopting them for long-term and large-scale storage facilities. CNG requires high-pressure storage, raising safety concerns, while LNG demands energy-intensive liquefaction at −162 °C and suffers from continuous boil-off during storage. Adsorbed Natural Gas (ANG), using porous materials like zeolite-like carbon materials and MOFs, offers promise but is limited by high material costs, slow adsorption kinetics and sustainability48.

SNG provides a safer, energy-dense, long-term storage option with inexpensive raw materials such as pure water (costing as little as USD$1.13 per ton). The current study demonstrates that both the methane uptake and kinetics achieved with the AM-Ice-based approach surpass those of several state-of-the-art porous materials under similar temperature and pressure conditions. For instance, Rozyyev et al.8 reported methane storage capacities of 0.137 and 0.110 g/g for MOF-250 and HKUST-1 (priced at USD $61,200 per kg as listed on the ACS Material website), corresponding to 65.05 and 62.98 v/v, respectively, at 6.5 MPa and 273 K. Antoniou et al.49 demonstrated that zeolite beta (USD $1,278 per kg as listed on the ACS Material website) and CZ1073 exhibited gravimetric methane adsorption capacity of 0.015 and 0.080 g/g, translating to volumetric values of 17.10 and 67.93 v/v under 3.5 MPa and 298 K. However, adsorption kinetics were not reported for these porous materials, which typically require 15 to 30 min to reach equilibrium in isothermal adsorption experiments. In contrast, AM-Ice achieves a volumetric methane storage capacity of 146.56 v/v (equivalent to a gravimetric value of 0.115 g/g) at a formation rate of 3.22 v/v s−1 within the first 30 s, and a t90 of just 2.42 min at the operating conditions of 272.7 K and 6 MPa, as presented in Supplementary Table 7. Beyond cost and performance, sustainability is a critical consideration. To store 1 tonne of methane, approximately 9.09 tonnes of HKUST-1 or 66.67 tonnes of zeolite beta are required. In comparison, the AM-Ice approach only requires 8.69 tonnes of water and 26 kg of tryptophan (at a concentration of 3000 ppm). The synthesis of HKUST-1 and zeolite beta involves energy-intensive processes, organic solvents, and multiple chemical reactants, resulting in significant carbon emissions. Although SDS has a lower unit price than tryptophan, it is a petrochemical-derived surfactant with poor biodegradability and notable aquatic toxicity, resulting in a higher environmental cost50. Moreover, its tendency to cause excessive foaming introduces additional operational challenges in large-scale applications. Conversely, water is abundant and readily available, and tryptophan can be sustainably produced via microbial fermentation, making the AM-Ice method a more environmentally benign and scalable alternative for methane storage.

AM-Ice based method is notably more efficient and a better performer than the aqueous solution-based approach. When using an aqueous solution containing 3000 ppm tryptophan (Trial D1 in the original study)46, the system achieves a gas uptake of 133.26 v/v (corresponding to 117.72 mmol/mol) in 96 min, with a maximum hydrate formation rate of approximately 0.04 v/v s−1 at 275.2 K and 10 MPa. The approach of using AM-Ice clearly offers nearly 40 times faster formation and approximately 80 times higher rates.

Inspired by the concept of battery systems and thermal energy storage systems, a charge–discharge gas storage system is proposed based on the AM-Ice clathrate approach, as illustrated in Fig. 8. In this AM-Ice Clathrate system, rapid ‘charging’ refers to the fast uptake of CH4 into the AM-Ice matrix, while ‘discharging’ is realized through on-demand methane release via controlled thermal stimulation. Following gas release, the resulting aqueous solution can be recycled to regenerate AM-Ice, enabling a fully reusable and sustainable gas storage cycle. The proposed system is suitable for renewable bio-methane storage and transport. Renewable bio-methane production is typically 1000 to 2000 times smaller at scale compared to conventional natural gas production systems. The storage and transport of renewable bio-methane as Bio-SNG through AM-Ice clathrate system is well-suited for both marine and land-based transport applications. Beyond natural gas storage, the AM-Ice clathrate system is a promising potential for the storage of CO2 and H2 gases. As summarized in Supplementary Table 8, the theoretical gravimetric storage capacities for CH4, CO2, and H2 are 0.15, 0.42, and 0.05 g/g, respectively, corresponding to volumetric storage capacities of 210.78, 210.78, and 570.35 v/v.

The left panel shows the AM-Ice system, while the right panel shows the clathrate hydrate system. The forward arrow indicates the gas charging process, during which AM-Ice is converted into clathrate hydrate. The backward arrow indicates the discharging process, where methane gas is released and AM-Ice is regenerated using the recovered solution.

Although AM-Ice clathrate system can achieve high gas uptake and a rapid hydrate formation rate, further investigations are necessary to fully understand the scalability of this approach. Other methodologies, such as vacuum-assisted gas extraction, could be explored to further optimize gas recovery strategies. While sI hydrate is thermodynamically less stable than sII hydrate, it has been reported that, under the self-preservation effect (which remains incompletely understood), sI hydrate can maintain stability at 268 K51. Consequently, the stability of methane hydrate formed with AM-Ice merits deeper exploration. Moreover, utilizing amino acids to engineer sII hydrate seeds may enhance the kinetics of sII methane hydrate formation. Alternatively, a composite system incorporating both ice and sII hydrate seeds engineered with amino acids could potentially combine high gas uptake with enhanced stability for the resulting clathrate composite system. The potential of the AM-Ice method for real natural gas mixtures—comprising methane, ethane, propane, and other trace components—represents a valuable direction for future investigations.

Methods

Materials

Methane gas (99.995 mol% purity) from Air Liquide Singapore Pvt. Ltd., five different types of amino acids: L-tryptophan, L-leucine, L-methionine, L-histidine and L-arginine (≥98% purity) Sodium dodecyl sulfate (≥98.0% purity) which were all purchased from Sigma-Aldrich, and ultrapure deionized water (Merck Millipore) were used for all experiments.

AM-Ice sample preparation

Figure 1a displays the schematic of making amino acid-modified ice used in our current experiments. A more in-depth description of the AM-Ice synthesis is presented in Supplementary Fig. 1. First, an amino acid solution was prepared at the required concentration for the experiment by thoroughly mixing the necessary amount of amino acid with deionized water using a magnetic stirrer. The prepared solution was subsequently stored in a refrigerator. Once the solution was completely frozen, it was initially fractured into small ice pieces and subsequently ground into a fine powder using a mortar and pestle. The ice sample size ranges from 40 µm to 240 µm, as shown in Supplementary Fig. 9. For normal ice preparation, a pure water solution was used instead of an amino acid solution, while all other procedures remained the same.

Experimental setup for AM-Ice clathrate formation and dissociation

Supplementary Fig. 10. illustrates a schematic representation of the apparatus employed in the experimental procedure. The primary element of the experiment comprised a high-pressure stainless steel reactor with an internal volume of approximately 150 mL and an exterior cooling jacket. The front and back sides of the reactor, as well as the top, are equipped with round acrylic sight windows to facilitate the observation of the morphology of the system during hydrate formation and dissociation. The temperature within the reactor was regulated by Chiller 1 via the circulation of the external glycol/water solution. A specialized gas supply container was deployed in the present experiment, with its temperature being precisely managed by Chiller 2. Through the experiment, temperature and pressure data of the reactor, gas supply vessel, and chiller are measured and recorded using thermocouples with a maximum tolerance of ±0.1 K and a pressure transducer that covers a range of 0–20 MPa with a tolerance of ±0.1%. For collecting the data required at 1 s intervals, thermocouples and pressure transducers are both coupled to a data acquisition system. A camera is positioned above the reactor to record the morphology of hydrates via the top sight window.

Experimental procedure for methane hydrate formation and dissociation

The water baths connected to the reactor and gas supply vessel were adjusted until the temperature of both vessels was stable at the required temperature for the experiment. The prepared AM-Ice was weighed to the required mass for the experiment and placed in the reactor. The reactor was then purged on three occasions through the methane supply container in order to expel any residual gas. Afterward, the reactor was pressurized to the designated experimental pressure for methane hydrate formation. The hydrate formation process was allowed to proceed for 30 min. Upon completion, the hydrate was fully dissociated by setting the chiller to 15 °C. Finally, the reactor temperature was restored to its initial value to complete the gas recovery process.

Experimental procedure for methane gas recovery from methane hydrate

Methane hydrate is first synthesized using SDS or tryptophan-modified ice (10 g) at 272.7 K and 6 MPa. A concentration of 3000 ppm SDS or tryptophan is used to prepare the modified ice. Once hydrate formation is complete, the reactor pressure is reduced to atmospheric pressure, and the chiller temperature is adjusted to initiate dissociation. As the hydrate dissociates, the pressure is gradually released. The methane recovery percentage is determined by the real-time pressure during the recovery process, divided by the final pressure when the hydrate is fully dissociated.

Apparatus and procedure for in-situ Raman analysis

Details and a representative schematic of the in-situ Raman spectroscopy equipment are available in the literature11,12. In brief, the setup included a 226 mL high-pressure jacketed crystallizer, and a gas supply container connected to an external refrigerator. Pressure and temperature in both vessels were continuously monitored using pressure transducers and thermocouples linked to a DAQ system. A real-time in-situ Raman spectrometer (Model: SRaman–532, W2 Innovations, Inc.) with a 532 nm Nd:YAG laser at 42 mW power was connected to the reactor, covering a spectral range of 150–4490 cm−1 with a resolution of 2.8 cm−1/pixel at 2200 cm−1. Like in the kinetic experiments, once the temperature stabilized, 10 g of AM-Ice was loaded into the crystallizer, ensuring the Raman probe was covered by the AM-Ice for precise laser targeting. After loading, the reactor was purged three times, followed by methane gas injection to the desired pressure. Raman signal acquisition was simultaneously initiated with the gas injection, and the real-time Raman spectrometer was set to record spectra at 1 s intervals throughout the hydrate formation process. To obtain the Raman signal without interference from methane gas, the pressure is released to atmospheric level after hydrate formation is completed, and the Raman spectra are then recorded.

Apparatus and procedure for powder X-ray diffraction characterization

The ice and hydrate samples were recovered and stored in a liquid nitrogen environment. Before measurement, the samples were crushed into a fine powder using a mortar and pestle in the presence of liquid nitrogen. Once prepared, the sample was immediately transferred to the p-XRD unit for analysis. A BRUKER D8 Advance diffractometer (40 kV, 30 mA) was used for the p-XRD measurements, employing CuKα radiation (λ = 1.542 Å) as the X-ray source. The p-XRD patterns were collected in the 2θ range of 10°–40° with a step size of 0.02° for the hydrate samples, and in the 2θ range of 5°–80° with a step size of 0.02° for the ice samples.

Data treatment

During the hydrate formation process, the amount of methane gas stored (Δnmethane uptake) is determined using the following equation:

In this equation, P and T represent pressure and temperature, respectively, while VR denotes the volume of gas within the reactor. The compression factor, Z, which can be calculated using the Pitzer correlation, accounts for gas non-ideality. R is the universal gas constant. The subscript “0” indicates the starting point of hydrate formation experiment, while the subscript :“t” refers to any given time during the experiment.

During the gas recovery process, the total amount of recovered gas is determined using the following equation:

Here, the subscript ‘end’ denotes the final state of the reactor after gas recovery is completed, while the subscript “int” represents the initial state of the reactor before gas recovery begins.

Then, the methane gas uptake during formation is adjusted by calibrating it against the final amount of recovered methane gas, as shown in the following equation.

The calibrated methane uptake, expressed as the volumetric gas storage capacity (i.e., the volume of gas at STP per unit volume of ice), can be determined using the following equation:

Here, v represents the molar volume of gas at STP, which is equal to 22.4 cm3/mmol. m is the mass of ice added to the reactor (in grams), and ρ is the density of bulk crystalline ice (0.91 g/cm3), which was used as an idealized reference to indicate the upper bound of methane storage performance.

Data availability

The relevant data generated in this study are provided in the Supplementary Information and Source Data file. Source data are provided with this paper.

References

Rogelj, J. et al. Paris Agreement climate proposals need a boost to keep warming well below 2 °C. Nature 534, 631–639 (2016).

Sarkodie S. A., Ahmed M. Y., Owusu P. A. Advancing COP26 climate goals: leveraging energy innovation, governance readiness, and socio-economic factors for enhanced climate resilience and sustainability. J. Clean. Prod. 431, 139757 (2023).

Mac Dowell, N. et al. The hydrogen economy: a pragmatic path forward. Joule 5, 2524–2529 (2021).

Speight J. G. Natural Gas: A Basic Handbook (Gulf Professional Publishing, 2018).

Bakkaloglu, S. & Hawkes, A. A comparative study of biogas and biomethane with natural gas and hydrogen alternatives. Energy Environ. Sci. 17, 1482–1496 (2024).

Birol, F. et al. Are We Entering a Golden Age of Gas. IEA World Energy Outlook (2011).

Marconi, P. & Rosa, L. Role of biomethane to offset natural gas. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 187, 113697 (2023).

Rozyyev, V. et al. High-capacity methane storage in flexible alkane-linked porous aromatic network polymers. Nat. Energy 4, 604–611 (2019).

Eddaoudi, M. et al. Systematic design of pore size and functionality in isoreticular MOFs and their application in methane storage. Science 295, 469–472 (2002).

Veluswamy, H. P., Kumar, A., Seo, Y., Lee, J. D. & Linga, P. A review of solidified natural gas (SNG) technology for gas storage via clathrate hydrates. Appl. Energy 216, 262–285 (2018).

Zhang, Y. et al. Synthesis of methane hydrate at ambient temperature with ultra-rapid formation and high gas storage capacity. Energy Environ. Sci. 15, 5362–5378 (2022).

Bhattacharjee, G., Goh, M. N., Arumuganainar, S. E. K., Zhang, Y. & Linga, P. Ultra-rapid uptake and the highly stable storage of methane as combustible ice. Energy Environ. Sci. 13, 4946–4961 (2020).

Sloan, J.rE. D. Fundamental principles and applications of natural gas hydrates. Nature 426, 353–359 (2003).

Walsh, M. R., Koh, C. A., Sloan, E. D., Sum, A. K. & Wu, D. T. Microsecond simulations of spontaneous methane hydrate nucleation and growth. Science 326, 1095–1098 (2009).

Chen, Y., Takeya, S. & Sum, A. K. Topological dual and extended relations between networks of clathrate hydrates and Frank-Kasper phases. Nat. Commun. 14, 596 (2023).

Yu, Y.-S., Zhang, X., Liu, J.-W., Lee, Y. & Li, X.-S. Natural gas hydrate resources and hydrate technologies: a review and analysis of the associated energy and global warming challenges. Energy Environ. Sci. 14, 5611–5668 (2021).

Sadeh, E. et al. Branched sulfonated promoter: achieving high methane uptake and foam-free gas recovery for solidified gas storage. Chem. Eng. J.487, 150674 (2024).

Denning, S. et al. Metal–Organic Framework HKUST-1 promotes methane hydrate formation for improved gas storage capacity. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 12, 53510–53518 (2020).

Casco, M. E. et al. Methane hydrate formation in confined nanospace can surpass nature. Nat. Commun. 6, 6432 (2015).

Roosta, H., Dashti, A., Mazloumi, S. H. & Varaminian, F. The dual effect of amino acids on the nucleation and growth rate of gas hydrate in ethane + water, methane + propane + water and methane + THF + water systems. Fuel 212, 151–161 (2018).

Omran A., Nesterenko N., Valtchev V. Driving sustainable energy storage: a multi-scale investigation of methane hydrate formation with green promoters and innovative reactor design. J. Energy Storage 75, 109653 (2024).

Lee, H. et al. Tuning clathrate hydrates for hydrogen storage. Nature 434, 743–746 (2005).

Zhang, X. et al. Cooperative effect of surfactant and porous media on CO2 hydrate formation and capacity of gas storage. Fuel 329, 125494 (2022).

Qin, Y. et al. Methane hydrate formation in porous media: Overview and perspectives. J. Energy Chem. 74, 454–480 (2022).

Farrando-Perez, J. et al. Rapid and efficient hydrogen clathrate hydrate formation in confined nanospace. Nat. Commun. 13, 5953 (2022).

Wang, W., Bray, C. L., Adams, D. J. & Cooper, A. I. Methane storage in dry water gas hydrates. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 130, 11608–11609 (2008).

Vishwakarma, G. et al. Understanding the kinetics of CO2 hydrate formation in dry water for carbon capture and storage: X-ray diffraction and in situ Raman studies. ACS Appl Mater. Interfaces 17, 4865–4874 (2025).

Florusse, L. J. et al. Stable low-pressure hydrogen clusters stored in a binary clathrate hydrate. Science 306, 469–471 (2004).

Zhu, J. et al. Effect of biofriendly amino acids on methane hydrate decomposition: insights from molecular dynamics simulations. Fuel 325, 124919 (2022).

Mirzakimov, U. Z. et al. Enhanced methane storage capacity in clathrate hydrate induced by novel biosurfactants: kinetics, stability, in vivo, and biodegradation investigations. J. Energy Storage 73, 108802 (2023).

Ganji, H., Manteghian, M., Sadaghiani Zadeh, K., Omidkhah, M. R. & Rahimi Mofrad, H. Effect of different surfactants on methane hydrate formation rate, stability and storage capacity. Fuel 86, 434–441 (2007).

He, Y. et al. Surfactant-based promotion to gas hydrate formation for energy storage. J. Mater. Chem. A 7, 21634–21661 (2019).

Sa, J.-H. et al. Hydrophobic amino acids as a new class of kinetic inhibitors for gas hydrate formation. Sci. Rep. 3, 2428 (2013).

Naeiji, P., Arjomandi, A. & Varaminian, F. Amino acids as kinetic inhibitors for tetrahydrofuran hydrate formation: experimental study and kinetic modeling. J. Nat. Gas. Sci. Eng. 21, 64–70 (2014).

Roosta, H., Dashti, A., Mazloumi, S. H. & Varaminian, F. Inhibition properties of new amino acids for prevention of hydrate formation in carbon dioxide–water system: experimental and modeling investigations. J. Mol. Liq. 215, 656–663 (2016).

Sa, J.-H., Kwak, G.-H., Lee, B. R., Ahn, D. & Lee, K.-H. Abnormal incorporation of amino acids into the gas hydrate crystal lattice. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 16, 26730–26734 (2014).

Bhattacharjee G., Linga P. Amino acids as kinetic promoters for gas hydrate applications: a mini review. Energy Fuels 35, 7553–7571 (2021).

Xiao, P. et al. Enhanced formation of methane hydrate from active ice with high gas uptake. Nat. Commun. 14, 8068 (2023).

Li, J. et al. Intensified methane hydrate formation from active ice in wide temperate range. Chem. Eng. Sci. 305, 121200 (2025).

Duan, J. et al. Insight into the micro-mechanism of hydrate-based methane storage from active ice. Fuel 381, 133154 (2025).

Duan, J. et al. Molecular insights into the fast hydrate formation in active ice. Chin. J. Chem. Eng. 80, 198–212 (2025).

Trinquier, G. & Sanejouand, Y. H. Which effective property of amino acids is best preserved by the genetic code?. Protein Eng. 11, 153–169 (1998).

Kumar, R., Lang, S., Englezos, P. & Ripmeester, J. Application of the ATR-IR spectroscopic technique to the characterization of hydrates formed by CO2, CO2/H2 and CO2/H2/C3H8. J. Phys. Chem. A 113, 6308–6313 (2009).

Seo, Y.-T. & Lee, H. 13 C NMR analysis and gas uptake measurements of pure and mixed gas hydrates: development of natural gas transport and storage method using gas hydrate. Korean J. Chem. Eng. 20, 1085–1091 (2003).

Ripmeester, J. A. & Ratcliffe, C. I. Low-temperature cross-polarization/magic angle spinning carbon-13 NMR of solid methane hydrates: structure, cage occupancy, and hydration number. J. Phys. Chem. 92, 337–339 (1988).

Veluswamy, H. P., Lee, P. Y., Premasinghe, K. & Linga, P. Effect of biofriendly amino acids on the kinetics of methane hydrate formation and dissociation. Ind. Eng. Chem. Res. 56, 6145–6154 (2017).

Veluswamy, H. P., Hong, Q. W. & Linga, P. Morphology study of methane hydrate formation and dissociation in the presence of amino acid. Cryst. Growth Des. 16, 5932–5945 (2016).

Makal, T. A., Li, J.-R., Lu, W. & Zhou, H.-C. Methane storage in advanced porous materials. Chem. Soc. Rev. 41, 7761–7779 (2012).

Antoniou, M. K. et al. Methane storage in zeolite-like carbon materials. Microporous Mesoporous Mater. 188, 16–22 (2014).

Vogtlander, J. et al. LCA-Based Assessment of Sustainability: the Eco-costs/Value Ratio (EVR) (VSSD, 2009).

Stern, L. A., Circone, S., Kirby, S. H. & Durham, W. B. Anomalous preservation of pure methane hydrate at 1 atm. J. Phys. Chem. B 105, 1756–1762 (2001).

Acknowledgements

The authors acknowledge the funding support from NRF Investigatorship NRF-NRFI08-2022-0006 (P.L.).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

P.L. and Y.Z. conceived the project and the approach; Y.M. and Y.Z. implemented all experiments; Y.Z. conducted the Raman and PXRD characterizations with the help of K.J. and G.V.; Y.Z. carried out the analysis with the help of Y.M.; Y.Z. draft the manuscript with the help of Y.M., and K.J.; P.L., Y.Z., C.-Y. S., and G-J.C. reviewed and edited the manuscript.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Peer review

Peer review information

Nature Communications thanks the anonymous reviewers for their contribution to the peer review of this work. A peer review file is available.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Source data

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Zhang, Y., Ma, Y., Jeenmuang, K. et al. Rapid conversion of amino acid modified-ice to methane hydrate for sustainable energy storage. Nat Commun 16, 8670 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-025-63699-2

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-025-63699-2