Abstract

It has become a heated debate as to whether the orbital Hall effect of a material could generate a non-local orbital current and a non-zero spin-orbit torque on an adjacent magnetic layer. Here, we report unambiguous evidence that, regardless of the ferromagnets (FMs) (e.g., Ni, Ni81Fe19, Fe, Fe60Co20B20, and Fe50Pt50), the spin-orbit torque generated by an adjacent Ta, which is predicted to have a 50 times greater positive orbital Hall conductivity than the negative spin Hall conductivity, has essentially the same, negative efficiency. This agrees with the spin Hall effect of Ta being the only source of the interfacial torque. We identify that the constant, positive estimate of the torque of the Ta/FM samples from spin-torque ferromagnetic resonance (ST-FMR) analysis in a specific FM thickness range (≥2 nm for Ni) results from the overlook of a significant thick-dependent self-induced ST-FMR signal of the FM. These results indicate the absence of orbital current torque in Ta/ferromagnet systems, regardless of the type, the spin-orbit coupling, and the layer thickness of the ferromagnets.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The development of fast, energy-efficient memory and computing technologies has triggered bloomed interest in the spin-orbit torques (SOTs) exerted on a ferromagnet (FM) by spin currents1,2,3. Since the discovery of the SOTs1,2, it had been a consensus that the spin currents associated with the SOTs are only directly generated by the spin Hall effect (SHE)1,3,4,5,6,7,8 or interfacial spin-orbit coupling (SOC) effects2,4,9,10,11,12,13 and that the orbital angular momentum is highly localized and gets completely quenched within a very short length scale of 0.2-0.4 nm, regardless of the SOC14,15,16. Until very recently, some experiments17,18,19,20,21,22, which cannot be readily understood by directly generated spin currents, together with some orbital current theories23,24, stimulated searching for indirect sources of spin currents from orbital-to-spin conversion via a bulk or interfacial SOC (Fig. 1a).

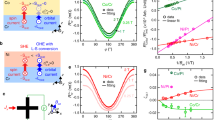

a Schematic of potential torque generation in Ta/ferromagnet bilayer by the spin Hall effect and orbital Hall effect of Ta. b Optical microscopy image and measurement geometry of a ST-FMR device. c Typical ST-FMR spectra for Ta 5/Ni 4, Ta 5/Ni81Fe19 3.8, Ta 5/Fe 3.3, Ta 5/Fe60Co20B20 3, and Ta 5/Fe50Pt50 3 (φ = 45o), with the three solid curves plotting the best fit of the data to Eq. (1) (in orange), the symmetric (in red), and antisymmetric (in blue) components. d Inverse thickness dependence of 1/ξFMR for the Ta/Ni, Ta/Ni81Fe19, Ta/Fe, Ta/Fe60Co20B20, and Ta/Fe50Pt50 samples. Solid lines in (d) represent linear fits. The rf power is 8 dBm.

Searching for hints for indirectly generating spin currents from the flow of orbital angular momentum has now become a rapidly growing interest in the field of spintronics25,26,27,28,29,30,31,32,33,34,35,36,37,38,39. For the sake of convenience, below we use orbital current torque to rename the SOTs with an orbital current as the initial source of the spin current. However, to be precise, experiments cannot directly tell whether the measured SOTs are initially due to a spin or orbital current because orbital current cannot interact with magnetization until it is converted into a spin current.

So far, the most likely observations that support the existence of orbital torque rely on the use of Ni as the torque detector19,21,31,32,33,34. The dampinglike torque efficiency (\({\xi }_{{{\rm{DL}}}}^{j}\)) of Ta/Ni bilayers was analyzed, e.g., using spin-torque ferromagnetic resonance (ST-FMR), as positive in the Ni thickness range of a few nanometers, in striking contrast to the negative spin Hall ratio of Ta as measured using bilayers of Ta/non-Ni 3d FMs (e.g., Ni81Fe19, Fe, FeCoB)19,21. The argument from this observation in the literature was usually that Ni had a weak but slightly stronger SOC than Ni81Fe19, Co, Fe, and Fe60Co20B20 such that Ni more efficiently converted the orbital current from Ta into spin current and generated a much stronger positive orbital torque than the negative spin Hall torque on the FM (the orbital Hall conductivity of Ta is predicted by band structure calculation to be 20-50 times greater than and of opposite sign compared to its spin Hall conductivity40,41). To explain the different experiments, such orbital torque argument had to assume that the orbital relaxation length (λ) of the sputter-deposited polycrystalline Ni was less than 0.5 nm (as indicated by the constant SOT for Ni thicker than <3 nm19, assuming the orbital current decays exponentially with the travel distance t in analog to spin current42,43, jL ~ e−t/λ, when the thickness of the layer in which the orbital current diffuses is greater than λ, Supplementary Fig. S1) or greater than 4 nm (as indicated by the continuous increase of the SOT with Ni thickness up to 20 nm31,32,33). Following similar arguments and with Ni as the detector, the generation of orbital current torque has also been claimed for many light metals that were believed to have little contribution to SOT generation before, such as Cr18,25,28 and Ti31,35. Given the widespread impact and the striking disagreements between the orbital–current–torque arguments and the long-standing consensuses and between different orbital torque arguments, a careful experimental test of the in-depth physics and a unified, precise understanding of the Ta/ferromagnet are urgently required.

Here, we demonstrate evidence for the absence of orbital current torque in the prototype Ta/FM systems, regardless of the type and the layer thickness of the FM. We find that the positive \({\xi }_{{{\rm{DL}}}}^{j}\) of the Ta/Ni, which is heavily cited in the literature as the most robust evidence of orbital current torque, is a misinterpretation of a non-negligible self-induced ST-FMR signal of the FM layer.

Results

Sample preparation

We sputter-deposited in-plane magnetized Ta/FM bilayers with Ta thickness of 5 nm and with the FM of Ni, Ni81Fe19, Fe60Co20B20, Fe, and Fe50Pt50 and the control FM single-layer samples to study the SOTs generated by the SHE and the orbital Hall effect of Ta as a function of the type, the thickness (tFM), and the SOC strength of the FM and the interface. Each bilayer is grown on an oxidized silicon substrate and protected by a MgO 2/Ta 2 bilayer (numbers are the layer thicknesses in nm) that is fully oxidized upon exposure to the atmosphere44. These samples are patterned into ST-FMR microstrips by photolithography and ion milling, followed by deposition of contacts of Ti 5/Pt 150. The resistivity of the Ta layer is determined to be 200 μΩ cm.

ST-FMR measurement of interfacial spin-orbit torques

We measure the SOTs of the Ta/FM using the three-terminal ST-FMR technique using the longitudinal voltage response (via magnetoresistance effects) by sweeping the in-plane magnetic field (H) at the azimuth angle (φ) of 45° relative to the rf current direction (Fig. 1b). As shown in Fig. 1c, each of the devices exhibits strong ST-FMR response (Vmix), fit of which to the relation45

yields the magnitudes of the symmetric and antisymmetric components (S and A), the FMR linewidth (∆H), and the resonance field (Hr). Since the sin2φcosφ scaling of S and A (Supplementary Fig. S2) have revealed no indication of any perpendicular spins46 or perpendicular Oersted field47, we define the ST-FMR efficiency (ξFMR) as

where e is the elementary charge, μ0 the permeability of the vacuum, Ms the saturation magnetization of the FM, and ℏ the reduced Planck’s constant. Meff is the effective demagnetization field of the FM and can be determined from the rf frequency (f) dependence of Hr following Kittel’s equation (Supplementary Fig. S3). As shown in Fig. 1d, \({\xi }_{{{\rm{DL}}}}^{j}\) and the fieldlike torque efficiency (\({\xi }_{{{\rm{FL}}}}^{j}\)) can be estimated from the inverse intercept and the slope of the linear fit of 1/ξFMR vs 1/tFM in the small-thickness regime following5

So far, we have assumed that in the linear regime S and A included only negligible “artifacts” contributions (Sart, Aart) from spin pumping (Sart ≠ 0, Aart = 0)46,48,49,50, the anomalous Nernst effect (due to a vertical thermal gradient formed by the unbalanced thermal dissipation at the substrate and the surface, Sart ≠ 0, Aart = 0)51, and bulk SOT (Sart ≠ 0, Aart ≠ 0)44. These contributions, if significant, may induce deviation from the linear scaling typically in the thick limit (see data of the Ta/Ni81Fe19, Ta/Fe, Ta/Fe60Co20B20, and Ta/Fe50Pt50 devices in Fig. 1d).

Absence of orbital current torques

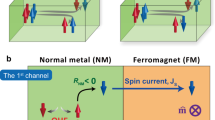

As summarized in Fig. 2a, the values of \({\xi }_{{{\rm{DL}}}}^{j}\) estimated from the above linear-regime analyses remain essentially the same for the Ta/Ni81Fe19 (−0.033 ± 0.004), the Ta/Fe (−0.026 ± 0.001), the Ta/Fe60Co20B20 (−0.030 ± 0.004), and the Ta/Fe50Pt50 (−0.031 ± 0.005). This result suggests a constant \({\xi }_{{{\rm{DL}}}}^{j}\) for the Ta/FM bilayer with the non-Ni FM thickness within the linear regime (typically <4–5 nm). In contrast, \({\xi }_{{{\rm{DL}}}}^{j}\) for the Ta/Ni is estimated to be +0.041 ± 0.003, which is of much higher magnitude and opposite sign compared to others. Such positive estimate for \({\xi }_{{{\rm{DL}}}}^{j}\) of Ta/Ni was cited as the key evidence for the presence of a strong orbital current torque in previous reports18,19,21. The positive, constant \({\xi }_{{{\rm{DL}}}}^{j}\) estimate at the Ni thicknesses of ≥2.5 nm, if represented an orbital current torque, would require the relaxation length of the associated spin and orbital currents to be as short as <0.5 nm (Supplementary Fig. S1), which strongly disagrees with the fairly long relaxation length of nonmagnetic and magnetic metals in some orbital current torque claims18,25,28,31,32,33.

a Efficiency of the dampinglike spin-orbit torque (black circles for data determined from Fig.1d without correction using control FM single layers, the red dots for data determined from Fig. 3b with correction using the control FM single layers), b bulk SOC strength, and c Sum interfacial magnetic anisotropy energy density of the magnetic interfaces for the Ta/FM bilayers plotted as a function of the FM type. Error bars are standard deviations.

The orbital current torque interpretation of the FM type dependence of the \({\xi }_{{{\rm{DL}}}}^{j}\) estimates would require very efficient orbital-spin conversion in the Ni layer and/or at the Ta/Ni interface but negligible orbital-spin conversion in the bulk and interfaces of the non-Ni FMs. According to theories41,52, the efficiency of orbital-spin conversion of a bulk material is approximately proportional to the spin-orbit correlation52, also called spin-orbit polarization41, due to spin-orbit interaction at the Fermi surface. The spin-orbit correlation is predicted to be linearly correlated to the SOC41 and to vary in sign with the band filling (positive for the 3 d FMs19 and 5 d Pt41). While the reliable calculation of the exact values of spin-orbit correlation for the various FMs (i.e., Ni, Ni81Fe19, Fe, Fe60Co20B20, and Fe50Pt50) and the Ta/FM interfaces has remained challenging and beyond the scope of this work, we show below that the bulk and interfacial SOC of the FMs, by themselves, cannot explain the distinct \({\xi }_{{{\rm{DL}}}}^{j}\) estimates for the Ta/Ni and Ta/non-Ni FM samples.

In Fig. 2b, we plot the bulk SOC strength of the FMs as 107 meV for Ni, 99 meV for Ni81Fe19, 70 meV for Fe, 59 meV for Fe60Co20B20, and 335 meV for Fe50Pt50, as estimated using the elemental SOC strengths53. Here, the average bulk SOC of the Fe alloys (Ni81Fe19, Fe60Co20B20, and Fe50Pt50), which is not trivial to obtain, is estimated assuming a linear composition dependence (see ref. 54 for the case of KZnSb1−xBix alloy) and the composition insensitivity of the elemental SOC of the Fe atoms55. The SOC of Ni is only very slightly greater than that of Ni81Fe19, Fe, and Fe60Co20B20, but 3 times weaker than that of Fe50Pt50. The bulk SOC by itself is unlikely to make Ni so different from the other FMs, including Ni81Fe19, 81% of which is also Ni. Thus, the FM-type dependence disproves the bulk SOC as the cause of the positive \({\xi }_{{{\rm{DL}}}}^{j}\) value for the Ta/Ni. This qualitative conclusion still holds even if the bulk SOC of the Fe alloys (Ni81Fe19, Fe60Co20B20, and Fe50Pt50) was only a monotonic function of the composition (which should be rather reasonable, see ref. 55 for the theoretical results of PtxPd1-x alloys) and slightly deviates from the values expected from the linear dependence.

Figure 2c shows the magnetic anisotropy energy density (Ks) of the FM interfaces as the indicator of the interfacial SOC56,57,58 that is distinct from the bulk SOC and sensitive to the short-range ordering and the spin-orbit proximity effect at the interface. Here, the values of Ks for the Ta/FM samples are determined from the slope of the linear fit of \({M}_{{{\rm{eff}}}}\) vs 1/tFM following the relation of \({M}_{{{\rm{eff}}}}\) = Ms − 2Ks/MstFM (Supplementary Fig. S3). Except for the Fe sample with strong SOC at the Fe/MgO interfaces, all the other samples have minimal interfacial SOC at the FM interfaces, revealing that, compared to the non-Ni devices, the Ta/Ni interface does not have a considerably higher interfacial SOC that allowed for enhanced orbital-spin conversion at the Ta/Ni interface and thus enhanced orbital current torque on the Ni layer. Consequently, the positive estimate of \({\xi }_{{{\rm{DL}}}}^{j}\) for the Ta/Ni sample cannot be explained by the interfacial SOC. The similar \({\xi }_{{{\rm{DL}}}}^{j}\) values of the non-Ni samples suggest that the large Ks of the Ta/Fe sample is mainly from the top Fe/MgO interface because the interfacial SOC of the Ta/Fe interface, if strong, should decrease the spin transparency of the interface and thus \({\xi }_{{{\rm{DL}}}}^{j}\) via spin memory loss8,56.

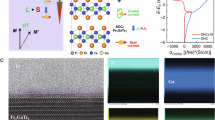

We discuss below that the positive torque estimate is most likely induced by the presence of a significant thickness-dependent self-induced bulk SOT within the FM layers. Figure 3a shows the representative ST-FMR spectra of the representative FM single layers with the thicknesses at which the Ta/FM bilayers exhibit linear dependence of 1/ξFMR on 1/tFM in Fig. 1d. While the self-induced S signals from the non-Ni single-layer FM samples are considerably smaller than that of the bilayers (Fig. 1c), the Ni single layer generates by itself a strong symmetric ST-FMR signal (indicated by the red S curve) that is of the same sign and similar magnitude as that of the Ta/Ni bilayer in Fig. 1c (also see Supplementary Fig. S5 for direct comparison of the measured S and A signals from the control single-layer Ni devices and the Ta/Ni bilayer devices). In consistency with the ST-FMR results, our independent harmonic Hall voltage measurement has also revealed positive bulk SOTs of comparable magnitudes for the Ni and Ta/Ni samples (Supplementary Note 1). These observations consistently suggest the presence of a strong self-induced ST-FMR in the Ni layer in the thickness range of >2 nm. The Ta/Ni81Fe19, Ta/Fe, Ta/Fe60Co20B20, and Ta/Fe50Pt50 samples also demonstrate a deviation from linear scaling only in the thick limit of typically >4–5 nm (Fig. 1d). These observations are consistent with the previous reports of self-induced bulk SOT in magnetic single layers, e.g., CoPt44, Ni81Fe1959, Fe60Co20B2060, Fe50Pt5061, and FexTb1-x62. The emergence only beyond a non-zero threshold layer thickness is also a characteristic of the bulk SOT effect44.

a Self-induced ST-FMR spectra for Ni 4, Ni81Fe19 3.8, Fe 3.3, Fe60Co20B20 3, and Fe50Pt50 3 single layers (φ = 45o), with the three solid curves plotting the best fit of the data to Eq. (1) (in orange), the symmetric (in red), and antisymmetric (in blue) components. b Inverse thickness dependence of 1/ξFMR contributed from the Ta layers of the Ta/Ni, Ta/Ni81Fe19, Ta/Fe, Ta/Fe60Co20B20, and Ta/Fe50Pt50 devices. ξFMR is calculated using the S and A values after subtracting the contributions of the magnetic single layers from those measured from the bilayers. Solid lines in (b) represent linear fits. Error bars are standard deviations.

After subtracting the self-induced S and A signals of the single FM layers (Fig. 3a) from that of the Ta/FM bilayers (Fig. 1c), the true values of S and A contributed by the Ta layer (see more details in Supplementary Note 2) are used to recalculate ξFMR of the Ta/FM devices following Eq. (2) and further \({\xi }_{{{\rm{DL}}}}^{j}\) of the interfacial dampinglike torque from the linear fits of 1/ξFMR vs 1/tFM for the Ta/FM in Fig. 3b following Eq. (3). The linear fit yields a constant \({\xi }_{{{\rm{DL}}}}^{j}\) of ≈ −0.028 for the wide Ni thickness range from 2 nm to 10 nm (Fig. 3b), which coincides reasonably with that of non-Ni samples as determined using the same method (the red dots in Fig. 2a) and the harmonic Hall voltage results (Supplementary Fig. S6). These observations are consistent with the negative spin Hall effect of Ta being the dominant source of the spin-orbit torque contribution from the Ta layer. The similar magnitudes of \({\xi }_{{{\rm{DL}}}}^{j}\) for different Ta/FM samples are consistent with the previous experiments57,63 and theories64 that the spin-mixing conductance of a metallic HM/FM interface is typically robust against the FM type.

Finally, the positive estimate of \({\xi }_{{{\rm{DL}}}}^{j}\) in the particularly wide thickness range for the Ta/Ni samples in Fig. 1d cannot be explained by any pumping of spin or orbital current from the FM into the Ta or any anomalous Nernst voltage effect. The contribution of spin/orbital pumping to the S signal via the inverse SHE of Ta should decrease upon enhancement of the conductivity, magnetic damping, and magnetization of the FM (Supplementary Note 3). However, the Ni has the highest conductivity (lowest resistivity) and the highest damping among the studied FMs and similar magnetization as the Fe50Pt50 (Fig. 4a and Supplementary Fig. S3). This is consistent with the previous estimation of negligible spin pumping contribution to the ST-FMR signal in the Ta and Pt devices in the pioneering works 1,45. To test any anomalous Nernst voltage effect, we fabricated ST-FMR devices with a 150 nm Si3N4 on the top of the Ta/Ni microstrips (Fig. 4b). The thick, high thermal-conductivity65 Si3N4 layer is expected to lower or even reverse the rf-heating-induced vertical thermal gradient, if any. However, without the self-torque correction, the 1/ξFMR vs 1/tNi data of these devices still yields a similar positive estimate of \({\xi }_{{{\rm{DL}}}}^{j}\) ≈0.055 for the Ta/Ni (Fig. 4b), which is close to that of the devices without any top Si3N4 sink layer (Fig. 1d). ξFMR also shows little enhancement as the rf power is increased from 0.01 dBm to 15 dBm (Fig. 4c). The anomalous Nernst effect cannot explain the presence of non-zero A signals in the Ni single layers (Fig. 3a). Thus, the anomalous Nernst voltage is excluded as the cause of the deviation from the linear scaling of 1/ξFMR vs 1/tNi in Fig. 1d and the positive estimate of \({\xi }_{{{\rm{DL}}}}^{j}\) for the Ta/Ni samples. These results reveal that the true Ta-contributed dampinglike SOT of the Ta/FM samples is always negative, regardless of the type and the thickness of the FM. This also reaffirms that the orbital Hall effect makes no detectable contribution to the SOT on the FM layer.

a Resistivity, Magnetization, and Magnetic damping of the Ta/FM bilayers with different FM thicknesses. b Optical microscopy image and 1/ξFMR vs 1/tFM for the Ta/Ni devices with a 150 nm Si3N4 thermal sink on the top. c Minimal variation of ξFMR with the rf power for Ta 5/Ni 5.1. The solid line in (b) plots the linear fit, while the dashed line in (c) is to guide the eyes.

Discussion

We have established robust evidence for the absence of orbital current torque in the Ta/FM bilayers, regardless of the type and the layer thickness of the FM. These findings have clarified the heated debate over the orbital current torque and have indicated a critical need to recheck the reported orbital current torque in samples containing Ni or other FMs with self-induced ST-FMR signals (whether or not there was a heavy or light metal). The universal deviation from the linear scaling of 1/ξFMR with 1/tFM due to self-induced ST-FMR signals suggests that the widely adopted ST-FMR analysis of the dampinglike SOT of a magnetic heterostructure using a single device is highly unreliable for the determination of interfacial SOTs even when the magnetic layer was very thick (> 10 nm) such that the interfacial fieldlike SOT contribution became weak. While we do not wish to immediately extrapolate the conclusion of the absence of orbital current torque from the Ta/FM system to other debated material systems, it is important to note that interface-dependent perpendicular effective field66, FM-type-dependent terahertz emissions67,68, and unusual magnetoresistance69 in magnetic heterostructures have been revealed to have physics origins alternative to orbital angular momentum.

Methods

Sample fabrication

We sputter-deposited in-plane magnetized Ta/FM bilayers with the 5 nm Ta and the FM of Ni, Ni81Fe19, Fe60Co20B20, Fe, and Fe50Pt50 and the control FM single-layer samples with only 1 nm Ta adhesion layer that maintains the Ni property but introduce minimal spin or orbital current. All the samples are grown on oxidized silicon substrates at room temperature with argon pressure of 2 mTorr under base chamber pressure of 10−9 Torr and protected by a MgO 2 nm/Ta 2 nm bilayer. These samples are patterned into 10 × 20 μm2 ST-FMR microstrips and 5 × 60 μm2 Hall bar devices by photolithography and ion milling. The electrical contacts of each device are Ti 5 nm/Pt 150 nm as deposited by a sputtering tool. The Si3N4 thermal sink is also deposited by sputtering.

Measurement

The spin-torque ferromagnetic resonance (ST-FMR) measurements were performed using a three-terminal configuration using the longitudinal voltage response by sweeping the in-plane magnetic field (0–0.3 T) at the different azimuth angles relative to the rf current direction. The rf power is modulated at a low frequency for high signal-to-noise-ratio detection of the ST-FMR response using a lock-in amplifier. The harmonic Hall voltage measurements were performed using a lock-in amplifier to apply an alternating electric field on the Hall bar device and then detect the harmonic Hall voltages while the magnetic field was rotated in the film plane.

Data availability

The authors declare that the data supporting the findings of this study are available within the main text and Supplementary Information files.

References

Liu, L. et al. Spin-torque switching with the giant spin Hall effect of tantalum. Science 336, 555 (2012).

Miron, I. M. et al. Perpendicular switching of a single ferromagnetic layer induced by in-plane current injection. Nature 476, 189 (2011).

Zhu, L. Switching of perpendicular magnetization by spin-orbit torque. Adv. Mater. 35, 2300853 (2023).

Haney, P. M., Lee, H. W., Lee, K. J., Manchon, A. & Stiles, M. D. Current-induced torques and interfacial spin-orbit coupling: Semiclassical modeling. Phys. Rev. B 87, 174411 (2013).

Pai, C., Ou, Y., Vilela-Leão, L. H., Ralph, D. C. & Buhrman, R. A. Dependence of the efficiency of spin Hall torque on the transparency of Pt/ferromagnetic layer interfaces. Phys. Rev. B 92, 064426 (2015).

Zhu, L., Zhu, L., Sui, M. L., Ralph, D. C. & Buhrman, R. A. Variation of the giant intrinsic spin Hall conductivity of Pt with carrier lifetime. Sci. Adv. 5, eaav8025 (2019).

Zhu, L., Ralph, D. C. & Buhrman, R. A. Maximizing spin-orbit torque generated by the spin Hall effect of Pt. Appl. Phys. Rev. 8, 031308 (2021).

Liu, Y., Yuan, Z., Wesselink, R. J. H., Starikov, A. A. & Kelly, P. J. Interface enhancement of Gilbert damping from first principles. Phys. Rev. Lett. 113, 207202 (2014).

Amin, V. P., Zemen, J. & Stiles, M. D. Interface-generated spin currents. Phys. Rev. Lett. 121, 136805 (2018).

Wang, L. et al. Giant room temperature interface spin Hall and inverse spin Hall effects. Phys. Rev. Lett. 116, 196602 (2016).

Li, S., Shen, K. & Xia, K. Interfacial spin Hall effect and spin swapping in Fe-Au bilayers from first principles. Phys. Rev. B 99, 134427 (2019).

Kim, K.-W., Lee, K.-J., Sinova, J., Lee, H.-W. & Stiles, M. D. Spin-orbit torques from interfacial spin-orbit coupling for various interfaces. Phys. Rev. B 96, 104438 (2016).

Wang, X. & Manchon, A. Diffusive spin dynamics in ferromagnetic thin films with a Rashba interaction. Phys. Rev. Lett. 108, 117201 (2012).

Mohn, P. in Magnetism in the solid state: an introduction, edited by M. Cardona, P. Fulde, K. von Klitzing, and H.-J. Queisser, Springer Series in Solid-State Sciences, Vol. 134 (Springer, 2003).

Tinkham, M. Group Theory and Quantum Mechanics, Dover Books on Chemistry (Dover, 2003).

Rang, M. & Kelly, P. J. Orbital relaxation length from first-principles scattering calculations. Phys. Rev. B 109, 214427 (2024).

Ding, S. et al. Harnessing orbital-to-spin conversion of interfacial orbital currents for efficient spin-orbit torques. Phys. Rev. Lett. 125, 177201 (2020).

Lee, S. et al. Efficient conversion of orbital Hall current to spin current for spin-orbit torque switching. Commun. Phys. 4, 234 (2021).

Lee, D. et al. Orbital torque in magnetic bilayers. Nat. Commun. 12, 6710 (2021).

Kim, J. et al. Nontrivial torque generation by orbital angular momentum injection in ferromagnetic-metal/ Cu/Al2O3 trilayers. Phys. Rev. B 103, L020407 (2021).

Dutta, S. & Tulapurkar, A. A. Observation of nonlocal orbital transport and sign reversal of damping-like torque in Nb/Ni and Ta/Ni bilayers. Phys. Rev. B 106, 184406 (2022).

Ding, S. et al. Observation of the orbital Rashba-Edelstein magnetoresistance. Phys. Rev. Lett. 128, 067201 (2022).

Go, D., Jo, D., Kim, C. & Lee, H. Intrinsic spin and orbital Hall effects from orbital texture. Phys. Rev. Lett. 121, 086602 (2018).

Jo, D., Go, D. & Lee, H.-W. Gigantic intrinsic orbital Hall effects in weakly spin-orbit coupled metals. Phys. Rev. B 98, 214405 (2018).

Sala, G. & Gambardella, P. Giant orbital Hall effect and orbital-to-spin conversion in 3d, 5d, and 4f metallic heterostructures. Phys. Rev. Res. 4, 033037 (2022).

Bose, A. et al. Detection of long-range orbital-Hall torques. Phys. Rev. B 107, 134423 (2023).

Li, T. et al. Giant orbital-to-spin conversion for efficient current-induced magnetization switching of ferrimagnetic insulator. Nano Lett. 23, 7174 (2023).

Xie, H. et al. Efficient noncollinear antiferromagnetic state switching induced by the orbital Hall effect in chromium. Nano Lett. 23, 10274 (2023).

Lyalin, I., Alikhah, S., Berritta, M., Oppeneer, P. M. & Kawakami, R. K. Magneto-optical detection of the orbital Hall effect in chromium. Phys. Rev. Lett. 131, 156702 (2023).

Choi, Y.-G. et al. Observation of the orbital Hall effect in a light metal Ti. Nature 619, 52 (2023).

Hayashi, H. et al. Observation of long-range orbital transport and giant orbital torque. Commun. Phys. 6, 32 (2023).

Moriya, H. et al. Observation of long-range current-induced torque in Ni/Pt bilayers. Nano Lett. 24, 6459 (2024).

Fukunaga, R., Haku, S., Hayashi, H. & Ando, K. Orbital torque originating from orbital Hall effect in Zr. Phys. Rev. Res. 5, 023054 (2023).

Fukunaga, R., Haku, S., Gao, T., Hayashi, H. & Ando, K. Impact of crystallinity on orbital torque generation in ferromagnets. Phys. Rev. B 109, 144412 (2024).

Hayashi, H., Go, D., Haku, S., Mokrousov, Y. & Ando, K. Observation of orbital pumping. Nat. Electron. 7, 646 (2024).

Zheng, Z. et al. Effective electrical manipulation of a topological antiferromagnet by orbital torques. Nat. Commun. 15, 745 (2024).

Santos, E. et al. Exploring orbital-charge conversion mediated by interfaces with CuOx through spin-orbital pumping. Phys. Rev. B 109, 014420 (2024).

Mendoza-Rodarte, J. A., Cosset-Chéneau, M., van Wees, B. J. & Guimarães, M. H. D. Efficient magnon injection and detection via the orbital Rashba-Edelstein effect. Phys. Rev. Lett. 132, 226704 (2024).

Ding, S., Kang, M., Legrand, W. & Gambardella, P. Orbital torque in rare-earth transition-metal ferrimagnets. Phys. Rev. Lett. 132, 236702 (2024).

Tanaka, T. et al. Intrinsic spin Hall effect and orbital Hall effect in 4d and 5d transition metals. Phys. Rev. B 77, 165117 (2008).

Kontani, H., Tanaka, T., Hirashima, D. S., Yamada, K. & Inoue, J. Giant orbital Hall effect in transition metals: origin of large spin and anomalous Hall effects. Phys. Rev. Lett. 102, 016601 (2009).

Park, W. et al. Measurement of resistance and spin-memory loss (spin relaxation) at interfaces using sputtered current perpendicular-to-plane exchange-biased spin valves. Phys. Rev. B 62, 1178 (2000).

Zhu, L., Zhu, L. & Buhrman, R. A. Fully spin-transparent magnetic interfaces enabled by insertion of a thin paramagnetic NiO layer. Phys. Rev. Lett. 126, 107204 (2021).

Zhu, L., Zhang, X. S., Muller, D. A., Ralph, D. C. & Buhrman, R. A. Observation of strong bulk damping-like spin-orbit torque in chemically disordered ferromagnetic single layers. Adv. Funct. Mater. 30, 2005201 (2020).

Liu, L., Moriyama, T., Ralph, D. C. & Buhrman, R. A. Spin-torque ferromagnetic resonance induced by the spin Hall effect. Phys. Rev. Lett. 106, 036601 (2011).

Liu, Q. et al. Efficient Generation of out-of-plane polarized spin current in polycrystalline heavy metal devices with broken electric symmetries. Adv. Mater. 36, 2406552 (2024).

Liu, Q. & Zhu, L. Current-induced perpendicular effective magnetic field in magnetic heterostructures. Appl. Phys. Rev. 9, 041401 (2022).

Nakayama, H. et al. Geometry dependence on inverse spin Hall effect induced by spin pumping in Ni81Fe19/Pt films. Phys. Rev. B 85, 144408 (2012).

Mosendz, O. et al. Detection and quantification of inverse spin Hall effect from spin pumping in permalloy/normal metal bilayers. Phys. Rev. B 82, 214403 (2010).

Zhu, L., Zhu, L., Ralph, D. C. & Buhrman, R. A. Origin of strong two-magnon scattering in heavy-metal/ferromagnet/oxide heterostructures. Phys. Rev. Appl. 13, 034038 (2020).

Karimeddiny, S., Mittelstaedt, J. A., Buhrman, R. A. & Ralph, D. C. Transverse and longitudinal spin-torque ferromagnetic resonance for improved measurement of spin-orbit torque. Phys. Rev. Appl. 14, 024024 (2020).

Go, D. & Lee, H.-W. Orbital torque: torque generation by orbital current injection. Phys. Rev. Res. 2, 013177 (2020).

Shanavas, K. V., Popovic, Z. S. & Satpathy, S. Theoretical model for Rashba spin-orbit interaction in d electrons. Phys. Rev. B 90, 165108 (2014).

Kim, D. & Liu, F. Topological alloy engineering and locally linearized gap dependence on concentration. Phys. Rev. B 106, 085105 (2022).

He, P. et al. Chemical composition tuning of the anomalous Hall effect in isoelectronic L10FePd1-xPtx alloy films. Phys. Rev. Lett. 109, 066402 (2012).

Zhu, L., Ralph, D. C. & Buhrman, R. A. Spin-orbit torques in heavy-metal-ferromagnet bilayers with varying strengths of interfacial spin-orbit coupling. Phys. Rev. Lett. 122, 077201 (2019).

Zhu, L., Ralph, D. C. & Buhrman, R. A. Effective spin-mixing conductance of heavy metal ferromagnet interfaces. Phys. Rev. Lett. 123, 057203 (2019).

Zhu, L., Zhu, L., Ma, X., Li, X. & Buhrman, R. A. Critical role of orbital hybridization in Dzyaloshinskii-Mariya interaction of magnetic interfaces. Commun. Phys. 5, 151 (2022).

Seki, T., Lau, Y., Iihama, S. & Takanashi, K. Spin-orbit torque in a Ni-Fe single layer. Phys. Rev. B 104, 094430 (2021).

Du, Y., Thompson, R., Kohda, M. & Nitta, J. Origin of spin–orbit torque in single-layer CoFeB investigated via in-plane harmonic Hall measurements. AIP Adv. 11, 025033 (2021).

Zhu, L., Ralph, D. C. & Buhrman, R. A. Unveiling the mechanism of bulk spin-orbit torques within chemically disordered FexPt1-x single layers. Adv. Funct. Mater. 31, 2103898 (2021).

Liu, Q., Zhu, L., Zhang, X. S., Muller, D. A. & Ralph, D. C. Giant bulk spin–orbit torque and efficient electrical switching in single ferrimagnetic FeTb layers with strong perpendicular magnetic anisotropy. Appl. Phys. Rev. 9, 021402 (2022).

Zhu, L. & Ralph, D. C. Strong variation of spin-orbit torques with relative spin relaxation rates in ferrimagnets. Nat. Commun. 14, 1778 (2023).

Tserkovnyak, Y., Brataas, A. & Bauer, G. E. W. Enhanced Gilbert damping in thin ferromagnetic films. Phys. Rev. Lett. 88, 117601 (2002).

Zhou, H. & Feng, T. Theoretical upper limits of the thermal conductivity of Si3N4. Appl. Phys. Lett. 122, 182203 (2023).

Liu, L., Liu, G. & Xing, L. Zhu, Asymmetric magnetization switching and programmable complete Boolean logic enabled by long-range intralayer Dzyaloshinskii-Moriya interaction. Nat. Commun. 15, 2978 (2024).

Zhang, H. et al. Tuning terahertz emission generated by anomalous Nernst effect in ferromagnetic metal. Appl. Phys. Rev. 10, 021417 (2023).

Feng, Z. et al. Anomalous Nernst effect induced terahertz emission in a single ferromagnetic film. Nano Lett. 23, 8171 (2023).

Zhu, L., Liu, Q. & Wang, X. Physics origin of universal unusual magnetoresistance. Natl Sci. Rev. 12, nwaf240 (2025).

Acknowledgements

This work is supported partly by the National Key Research and Development Program of China (2022YFA1204000), the Beijing Natural Science Foundation (Z230006), and by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (12304155, 12274405).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

L.Z. conceived the project, Q.L. performed the measurements, L.Z. and Q.L. wrote the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Peer review

Peer review information

Nature Communications thanks the anonymous, reviewers for their contribution to the peer review of this work. A peer review file is available.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Liu, Q., Zhu, L. Absence of orbital current torque in Ta/ferromagnet bilayers. Nat Commun 16, 8660 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-025-63809-0

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-025-63809-0