Abstract

Gas–liquid interfaces at the micro- and nanoscale are emerging hotspots for unique chemical reactivity, yet the reactivity of individual microbubbles remains largely unexplored. Here, we visualize the catalyst-free generation of reactive oxygen species, particularly hydroxyl radicals, at the gas‒liquid interface of microbubbles. In-situ chemiluminescence imaging, together with spectroscopic analyses, and multiscale computational simulations shows that the enrichment of hydroxide ions at the microbubble surface, coupled with the interfacial electric field, drives the catalyst-free generation of hydroxyl radicals. The generated hydroxyl radicals enable efficient degradation of organic pollutants and facilitate the conversion of nitrogen into nitrate ions under mild conditions, highlighting the practical applicability of this catalyst-free process in environmental remediation and sustainable nitrogen fixation. These findings provide new insights into catalyst-free radical chemistry at gas–liquid interfaces, with significant implications for catalytic processes, sustainable chemical manufacturing, and environmental catalysis.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Chemical reactions at the interface between water and other phases are fundamental to many natural and industrial processes, including atmospheric chemistry1, chemical manufacturing2,3,4, and energy conversion5,6. Unlike bulk water, these interfaces exhibit unique reactivity due to their localized molecular distributions and varying environmental conditions4,7,8,9,10. Despite the growing interest in this area11,12, the dynamic properties of micro- and nanoscale bubble interfaces remain largely unexplored, even though they hold significant potential for facilitating chemical reactions.

Micro- and nanoscale bubbles exhibit distinct physicochemical properties, including high surface curvature, mobility and stability, that create reactive environments at their interfaces13,14,15,16,17,18. These features result in a dynamic and reactive interface that could lead to chemical processes that are not feasible in bulk water19,20,21. Previous studies have demonstrated that the gas‒liquid interface of microbubbles can facilitate various chemical transformations, including the conversion of gaseous compounds into valuable products22,23,24,25. These findings have opened up new avenues for sustainable chemical manufacturing.

Understanding these processes is critical to numerous fields, such as advanced material synthesis, electrochemical energy storage, and pollutant degradation26,27. While there have been significant strides in microdroplet-based systems for investigating the gas‒liquid interface28,29,30, directly probing chemical reactions at these highly dynamic interfaces remains a major challenge. Micro- and nanobubbles, due to their buoyancy and short-lived nature, present significant difficulties for in situ spectroscopic or electrochemical measurements. Their curved surfaces scatter light31,32, and the interfacial composition evolves continually during reactions, complicating the study of chemical dynamics. These factors have limited detailed mechanistic studies to date.

Here, we directly probe and visualize the chemical dynamics at the gas‒liquid interface of microbubbles, with a specific focus on the generation of hydroxyl radicals (•OH) and the subsequent chemical reactions they facilitate. Through a combination of experimental techniques and theoretical modeling, we characterize the unique properties of these interfaces and uncover new fundamental principles governing their reactivity. By directly visualizing and mechanistically probing •OH generation at individual microbubble interfaces under mild, catalyst-free conditions, our study provides critical insights into gas–liquid interfacial chemistry. Moreover, these insights open new pathways for environmentally sustainable chemical processes, highlighting significant potential in pollutant remediation, sustainable nitrogen fixation, and green chemical manufacturing.

Results

Imaging of hydroxyl radical production at the gas–water interface

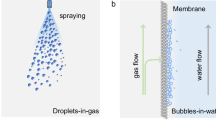

To investigate interface behavior, we introduced an aqueous solution containing nitrogen micro- and nanobubbles, produced by a pressurized dissolved-air type micro-nanobubble generator, into a custom-built flow cell tilted at 45° (Fig. 1a and S1). This setup allowed micron-sized N2 bubbles to adhere to the glass slide at the window of the flow cell, which allowed precise observations of the gas‒liquid interface via inverted fluorescence imaging techniques. We used luminol (5-amino-2,3-dihydro-1,4-phthalazinedione, LH-), a classic chemiluminescent agent that reacts with reactive oxygen species (ROS) in an alkaline environment such as •OH to emit light, to serve as an indicator of •OH generation at the interface (Supplementary Note 2). We observed significant chemiluminescence at the gas‒liquid interface of the bubble under UV light exposure, indicating the generation of •OH. Intense chemiluminescence was generated at the gas‒liquid interface compared with the surrounding liquid environment (Fig. 1b). Additionally, chemiluminescence was observed around the gas‒liquid interface of O3 and other three gas components bubbles (Fig. S2, S3). It should be noted that although different gas compositions could influence subsequent reaction pathways and resulting secondary products, the chemiluminescence intensity observed here primarily reflects the immediate capture and detection of •OH by luminol molecules. Thus, the direct chemiluminescence signal is largely indicative of interfacial •OH production, independent of gas-specific secondary reaction products. The nitrogen microbubbles used for chemiluminescence imaging had an average diameter of approximately 50 µm and remained stable, maintaining a consistent gas‒liquid interface for at least 10 minutes during the imaging measurements (Fig. S4), suggesting that the local changes in redox reactivity were intrinsic to the gas‒liquid interface rather than artefacts of rapid cavitation events. Under alkaline conditions, the diffusion rate of N2 molecules is known to decrease, and the stable hydrogen bonding network surrounding hydroxide ions (OH−) is known to enhance the dynamic stability of these bubbles33,34,35,36, which provides favorable conditions for our subsequent experiments. We also modulated the UV light intensity, which yielded an increase in chemiluminescence as the light power increased (Fig. 1c and S5).

a Schematic diagram of the experimental process of generating microbubbles and in situ imaging the chemiluminescence phenomenon of microbubbles. b Intense chemiluminescence generated at the gas‒liquid interface of the N2 bubble. c Chemiluminescence intensity around nitrogen gas bubbles containing luminol molecules as a function of light intensity. d Statistics of the diameters of N2 bubbles deposited on a glass slide. e Chemiluminescence intensity of N2 bubbles of different sizes and f light intensity statistics per pixel. Error bars for (f) are derived from the range within 1.5IQR calculated over the fluorescence intensity. All figures use the same scale bar: 11 μm. Source data are provided as a Source Data file.

We statistically analysed the diameters of more than 100 bubbles in different fields of view and found that the average size of the bubbles emitting chemiluminescence was 50 microns (Fig. 1d). Interestingly, the average chemiluminescence intensity of each bubble did not significantly differ with bubble size (Fig. 1e), whereas localized regions on larger bubbles presented higher maximum intensities (Fig. 1f). This increase indicates that the surface area of the bubbles plays a crucial role in •OH generation. Unlike microdroplets, curvature effects on interfacial electric fields and zeta potentials were minimal for microbubbles in the 10–50 µm diameter range, as demonstrated previously21. Specifically, due to the large ratio of particle radius (a) to Debye length (κ−1 ≈ 2 nm, thus κa ≫ 1), curvature effects are negligible. This allows us to approximate the interface as essentially planar37,38 and show that the zeta potentials of microbubbles at micrometer scales are indeed size-independent, confirming our observations. Although bubble curvature does not significantly affect the electric field or zeta potential at this scale, the larger absolute surface area provided by bigger microbubbles offers more adsorption sites for hydroxide ions, facilitating their transformation into hydroxyl radicals. Consequently, localized regions of larger microbubbles can exhibit stronger chemiluminescence signals, even though average intensities across the entire bubble surface remain relatively consistent.

To rule out the potential effect of the solid interface since the bubbles were deposited on glass slides, we generated bulk-phase bubbles via laser irradiation and thermal cavitation in the solution. This method uses a low-energy continuous-wave (CW) laser, which creates vapor bubbles39,40 through gentle heating with minimal interference rather than violent breakdown of water41. We observed that these freely moving bulk-phase bubbles also presented intense chemiluminescence (Fig. S6 and S7). This confirmed that ROS generation at the gas‒liquid interface is a general phenomenon that is independent of the formation method and location of bubbles.

Moreover, we used a different luminol derivative that emits green light upon ROS interaction, and under these conditions, chemiluminescence was still detected at the interface (Fig. S8), confirming the generality of the ROS generation mechanism at the bubble interface under UV irradiation. We conducted further experiments using coumarin as a molecular probe to quantitatively assess the generation of •OH radicals. Upon reacting with •OH, coumarin produces 7-hydroxycoumarin, a fluorescent compound that allows for quantitative analysis through fluorescence intensity measurements. This provides additional quantitative validation for the presence and spatial distribution of •OH in our system (Fig. S9). Additionally, mass spectrometry provided complementary evidence: upon UV irradiation on nitrogen microbubble-containing water, a distinct peak corresponding to [(DMPO + O) + H]+ (m/z 130) was detected (Fig. S10). This observation provides additional evidence for the generation of •OH at microbubble interface.

Similar to previous findings showing that the photochemical reaction of phenol proceeds up to 10,000 times faster at the air‒water interface than in bulk water due to the unique solvation environment at the interface42, our study reveals that the gas‒liquid interface of bubbles exhibits increased reactivity under UV irradiation. This acceleration can be attributed to the increased electron transfer and distinct interfacial conditions, facilitating the generation of •OH.

Mechanisms of hydroxyl radical generation

To verify the generation of •OH, we introduced tert-butanol, a known •OH quencher, into the system. The significant decrease in chemiluminescence intensity following tert-butanol addition, with kinetics consistent with first-order behavior (Fig. 2a, b and S11), strongly supports the idea that •OH was present at the gas‒liquid interface. Furthermore, electron paramagnetic resonance (EPR) spectroscopy confirmed the generation of •OH radicals at the interface under UV irradiation, as evidenced by the characteristic 1:2:2:1 EPR spectral peak (Fig. 2c). These findings substantiate the notion that electron transfer processes occurred at the interface. In our experiments, we specifically utilized nitrogen microbubbles under alkaline conditions to avoid interference from reactive gas components like ozone, which were common in previous studies43,44,45,46. Nitrogen was was deliberately selected due to its inertness, ensuring significantly fewer reactive species are generated compared to air or ozone. Consequently, •OH formation observed in our system mainly results from interactions between OH− and the gas–liquid interface under external field stimulation, rather than the gas composition itself.

a,b The variation in the chemiluminescence intensity of N2 bubbles over time after the addition of tert-butanol. c EPR experiments verifying the generation of hydroxyl radicals. d, e Chemiluminescence intensity at different pH values. f, g Bubble under radiation with center wavelengths of 365 nm and 545 nm. h COMSOL simulation of the strong electric field at the gas‒liquid interface of bubbles. All figures use the same scale bar: 11 μm. Source data are provided as a Source Data file.

To further explore these interfacial electron-transfer processes, we conducted electrochemical experiments in which the flow cell window was replaced with a conductive indium tin oxide (ITO) electrode. Anodic current was observed at potentials below +1.9 V (vs. SHE) in the bubble system under UV illumination, despite the thermodynamic unfavourability of OH− oxidation to •OH at these potentials. This suggests that the high nonequilibrium concentration of OH− at the gas‒liquid interface may drive this otherwise unfavorable reaction. Additionally, the local increase in current density at the same redox potential indicates an increased reaction rate (Fig. S12), implying that the interfacial electric field played a role in facilitating redox processes.

We therefore hypothesize that the •OH is present around the bubbles because of the presence of a high concentration of unbalanced OH− ions at the gas‒liquid interface of the bubbles. Preferential adsorption of OH− at interfaces has been shown to significantly modify local electric fields and hydrogen-bond networks at macroscopic air–water interfaces47. Similar phenomena have been reported in computational studies of microdroplets, further confirming interfacial OH− enrichment and subsequent alterations to the local hydrogen-bonding environment48. We therefore propose that preferential adsorption of OH− is a general phenomenon occurring at gas–liquid interfaces, extending to both microdroplet and microbubble interfaces. Zeta potential measurements confirmed that the bubble interface exhibited a negative charge across various pH values (Fig. S13), which is indicative of preferential OH− adsorption. For a 50-micron N2 bubble, the interfacial charge density at the gas‒liquid interface is estimated to be −52 µC/cm2 19., corresponding to 5.4 × 10−10 mol/cm2 OH−. The unique hydrophobic characteristics of •OH radicals at the gas‒liquid interface6, coupled with the presence of liquid and vapor phases, favor not only the formation of •OH but also efficient proton transfer within the hydrogen‒bond network.

To further confirm that the generation of •OH at the gas‒liquid interface is driven by a high concentration of hydroxide ions in strong electric fields, we examined the chemiluminescence intensity of N2 bubbles across different pH values. Given that luminol molecules dissolve only in strongly alkaline solutions, we employed L-012, an alternative chemiluminescence probe, which operates effectively over a broader pH range. Notably, the chemiluminescence intensity significantly increased at pH 12.5 compared with that at pH 8.9 (Fig. 2d, e). Moreover, when microbubbles with high interfacial areas were injected into the solution, the overall pH of the solution decreased (Fig. S14). Additionally, to further validate the observed phenomenon and rule out potential experimental artifacts, we conducted a control experiment in which the solution pH was continuously monitored following the introduction of micro- and nanobubbles. This experiment consistently showed a gradual decrease in pH over time, supporting our conclusion that OH− are being adsorbed onto the microbubble interfaces. This pH dependency further highlights the role of the OH− concentration in ROS generation. When the bubbles were obstructed by particles, preventing OH− from accumulating on the bubble surface, a significant reduction in chemiluminescence was observed, further supporting the aforementioned mechanism (Fig. S15). To further explore the wavelength-dependent properties of this phenomenon, we shifted the light source to green light (545 nm) and other wavelengths, which yielded no chemiluminescence (Fig. 2f, g and Fig. S16).

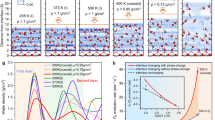

Evidence from theory suggests that ultrahigh electric fields (109 V/m) exists at the gas‒water interface in droplets, which are sufficient to induce spontaneous redox reactions3,29,49,50,51,52. This provides a plausible explanation for the conversion of OH− ions around bubbles into hydroxyl radicals. To verify the presence of strong electric fields at the gas‒liquid interface, we conducted COMSOL simulations (see Supplementary Note 3 for details) to examine the electric field distribution around 100 nm diameter N2 bubbles at different pH values. Our simulations revealed that the electric field at pH 13 reached 1.02×109 V/m, with the peak field strength increasing with increasing pH (Fig. 2h). Additionally, we simulated the concentration of OH− around the bubble under UV irradiation at pH 12, which revealed that the local OH− concentration was a factor of 69.4 higher than that in bulk solution (Fig. S17). Thus, there findings indicate that the high concentration OH− enriched at the gas‒liquid interface is in a more active state due to the presence of a strong electric field, creating a favorable environment for •OH formation via electron loss (Fig. 3).

Compared to bulk solutions, OH− in microbubble-containing solutions tend to accumulate at the gas–liquid interface. Due to the presence of a strong electric field, these enriched ions exist in a more reactive state, which facilitates the formation of •OH through electron loss. When external perturbations such as optical fields are applied, this process is accelerated, rapidly converting OH− into •OH, which can subsequently recombine to form ROS. In our system, the presence of luminol enables these ROS to react with it, resulting in chemiluminescence.

To further explore the mechanisms of •OH formation at the gas‒liquid interface of bubbles, we performed a series of MD simulations (Supplementary Note 4). We first constructed bubble models using N2 and O2 at varying initial gas densities to determine the minimum supersaturation required for stability. Only bubbles with gas concentrations roughly 100–200 times the gas phase at standard state maintained a distinct core and overall shape over a 10 ns NVT run (Fig. S18, S19), despite some dissolution of peripheral molecules toward the end of the simulations. This behavior is expected for nanoscale bubbles, which shrink unless the surrounding liquid is highly supersaturated. To reduce computational expense while preserving qualitative stability, all production simulations employed a smaller N2 bubble (radius ≈ 1.5 nm) containing 200 molecules; even under this leaner condition, the bubble remained relatively intact for the full 10 ns simulation (Fig. 4a). The density distribution along the z-direction (Fig. 4b) indicates that the bubble gradually formed a density gradient in the radial direction, with a single maximum point corresponding to a minimum point of water density, implies that the bubble did not split or form other gas clusters. We conducted 50 ps QM/MM MD simulations to investigate the behavior of hydroxide ions in both the bubble model and the bulk solution. Radial distribution function (RDF) analysis revealed that the OH− ions at the bubble interface have a lower water coordination number than those in the bulk solution do, which may enhance their reactivity (Fig. 4c, d). This partial solvation destabilizes OH− by reducing its hydration enthalpy and raising its ground-state energy, and thereby lowering the Gibbs free energy change associated with electron loss, thus may enhancing the thermodynamic favorability of •OH formation. This result is consistent with previous reports of similar redox reaction mechanisms in microdroplets50,52,53,54,55.

a Snapshots of the N2 bubble in the time period of 0–10 ns under NVT conditions. b Gas and liquid density profile along the z-axis of the nitrogen bubble model. c Radial distribution function (RDF) and the coordination number (CN) of water from 50 ps QM/MM trajectories of OH⁻ at the liquid–bubble interface. d RDF and the CN of water from 50 ps QM/MM trajectories of OH− in bulk water. In Fig. 4c, d, the light blue color represents the raw data of the RDF, while the dark blue indicates the smoothed data. The yellow dashed lines denote the values of the coordination number curve corresponding to the maximum extent of the first peak in the RDF. Source data are provided as a Source Data file.

Finally, we evaluated the vertical ionization energy (VIE) of OH− at the bubble interface via QM/MM MD simulations (Supplementary Note 5). The VIE distribution followed a Gaussian shape (Figs. S20, S21), with an average value of 200.0 kcal/mol, which was slightly lower than the experimental value (207 kcal/mol)56 for OH− in the bulk solution. This difference reflects the catalytic effect of the bubble interface. Although the exact electron-transfer activation barrier is difficult to quantify due to complexities such as reorganization energy and the diversity of OH− electron acceptors, the observed lowering of VIE at the interface serves as indirect evidence of a reduced energetic threshold for electron ejection. The interfacial electric field may provide direct energetic input needed to overcome activation barriers, and potentially lowers the barrier itself via polarization effects that modify the electron-transfer pathway, which has also been supported by emerging theoretical and computational findings29,57,58.

The experimental and theoretical findings collectively validated the idea that •OH was generated at the gas‒liquid interface of the bubbles in the solution. On the basis of these results, we propose a mechanistic pathway (Supplementary Note 6) for hydroxyl radical generation at the bubble interface. In this model, the catalyst-free formation of •OH is driven by three synergistic interfacial effects: (1) partial solvation of OH− reduces its hydration enthalpy and raises its ground-state energy, lowering the Gibbs free energy for electron loss; (2) the strong local electric field provides direct activation energy and polarizes the transition state, further reducing the electron-transfer barrier; and (3) OH− enrichment at the interface boosts local reactant concentration, shifting the reaction equilibrium toward •OH formation. When perturbed by external forces, such as optical fields, this process accelerates, rapidly converting OH− into •OH radicals. These radicals can then either recombine to form H2O2 or transfer electrons to dissolved oxygen in the solution, producing O2•⁻. In the presence of luminol in our systems, these ROS react with luminol, leading to chemiluminescence.

Catalyst-free conversion processes and applications

The generation of ROS, particularly •OH, at the gas‒liquid interface of bubbles without external catalysts presents significant opportunities for practical applications in chemical manufacturing and environmental remediation. To demonstrate the utility of this phenomenon, we conducted pollutant degradation experiments using rhodamine B (RhB), methylene blue, all of which are typical toxic pollutants. Microbubbles generated by a gas disperser led to notable degradation of these pollutants, as evidenced by a significant concentration reduction over time (Supplementary Note 7 for details). Specifically, we compared RhB degradation rates under three different conditions: N2 bubbles only, UV irradiation only, and a combination of N2 bubbles and UV (Fig. 5a). The results show that the combined application of N2 bubbles and UV leads to the highest degradation efficiency. We also utilized an LC-MS to analyze the intermediates formed during the degradation of RhB under nitrogen microbubble and UV exposure (Suppl. Note 23). The pollutant degradation effect varied significantly with different concentrations of OH− (Fig. S27), further confirming the generation of oxidizing radicals.

a Degradation of RhB under three conditions, UV irradiation, bubble generation, and the combined effect of both. RhB, 2.5 mg/L. b Degradation effects of different volumes of methylene blue. methylene blue, 2 mg/L (30-min reaction time). c, d The impact of air pump-generated bubble interfaces on the degradation of RhB and methylene blue. RhB, 2.5 mg/L (air microbubbles + UV); methylene blue, 5 mg/L (air microbubbles + UV). e Yield of nitrate ion with increasing N2 bubbling time. Error bar for (a–e) are presented as mean values ± SD (n = 3). Source data are provided as a Source Data file.

To advance the practical applications of ROS generation, we focused on two strategies: optimizing reactor-level parameters and broadening the applicability of the system by using air instead of nitrogen. First, to explore the potential of this system at an industrial scale, we investigated critical operational parameters at the reactor scale, particularly the effects of bubble generation rate and bubble residence time on degradation efficiency. By varying the solution volumes from 200 to 600 mL, corresponding to liquid column heights of 42, 63, 84, 105, and 126 mm, we calculated bubble residence times to be approximately 31, 46, 62, 77, and 93 s, respectively (Supplementary Note 25 for details). Pollutant degradation efficiency increased with solution volume up to 400 mL, where an optimal balance between gas–liquid interfacial area and bubble residence time was achieved. Beyond this volume, increased bubble coalescence occurred, reducing the number of smaller bubbles and thus diminishing the effective interfacial area, which in turn decreased the degradation performance (Fig. 5b). These findings emphasize the need to carefully balance the bubble residence time and volume to maximize reactor efficiency.

Next, to increase the practicality of this approach, we replaced N2 with air as the gas source for generating microbubbles under UV radiation. Remarkably, the degradation of pollutants using air-driven microbubbles was comparable to the results obtained with N2 (Fig. 5c, d), demonstrating that specialized gases are unnecessary for effective pollutant degradation. The similar degradation performance observed for N2 and air microbubbles can be attributed to the dominant role of •OH, which have a high redox potential ( + 2.8 V) and strong reactivity toward RhB. Although air introduces dissolved O2, which can form superoxide (O2•⁻), its lower redox potential ( ~ 0.93 V) and limited reactivity make it less effective. Moreover, O2 may even reduce •OH availability through side reactions (e.g., O2•⁻ + •OH → O2 + OH−). Without transition metal catalysts like Fe2+, in situ generated H2O2 is also less likely to efficiently produce •OH, potentially leading to quenching effects. By utilizing ambient air, we significantly lowered the operational costs of the system, making it more viable for large-scale applications.

Furthermore, we demonstrated that introducing nitrogen into an aqueous solution to form microbubbles enables the efficient, direct, and environmentally friendly conversion of nitrogen into nitrate ions (Fig. 5e). Due to the high oxidation potential, •OH can significantly lower the activation energy barrier of the nitrogen triple bond (N ≡ N). Electrophilic attack by •OH initially forms nitrogen-containing intermediates such as dihydroxy diazene (H2N2O2). With continued activation by •OH, H2N2O2 undergoes successive dehydrogenation and oxidation steps, ultimately forming nitrate (NO3−)59. This nitrogen fixation approach for the sustainable production of nitric acid has the potential to facilitate energy-efficient and green nitric acid manufacturing.

Discussion

In this work, we showed that the gas‒liquid interface of microbubbles is a highly reactive zone capable of generating •OH without the need for external catalysts. This process is driven by the synergistic effects of interfacial hydroxide ion enrichment, strong localized electric fields, and partial solvation at the bubble interface. Both experimental observations and theoretical simulations confirmed that these interfacial conditions significantly lower the energy barrier for electron loss from OH− ions, facilitating the efficient formation of •OH. Beyond fundamental insights, we translated this mechanism into practical applications, demonstrating the effective degradation of recalcitrant organic pollutants and the direct conversion of nitrogen gas into nitrate ions under mild conditions. Our findings not only advance our understanding of interfacial chemistry, by elucidating how microbubble interfaces can facilitate chemical reactions typically requiring catalytic materials. This work also highlights a scalable, cost-effective approach for effectively applying this reactivity characteristic in environmental remediation and chemical processes.

Methods

Micro/nano bubble generation

Micro- and nanobubbles are generated by circulating water in a 5 L plastic container using a microbubble generator (ZJC-NM; Zhongjing Technologies Inc.). Nitrogen or air was introduced at a flow rate of 0.3 L/min at the suction side of the pump. High pressure at the discharge side facilitated gas dissolution into the water, creating a supersaturated solution. By reducing the pressure at the nozzle, gas-supersaturated water released microbubbles. The bubble-containing water was then directed into a custom-designed flow cell using a peristaltic pump, allowing micron-sized bubbles to adhere to the quartz glass observation window for imaging.

Fluorescence, and chemiluminescence microscopy

Bubble imaging and chemiluminescence detection were performed using motorized inverted fluorescence microscope (Olympus, IX83P2ZF) equipped with a sCMOS camera (Teledyne Photometrics, Prime 95B) and a 20× objective (Olympus, LUCPLFLN20XPH). Bright-field and chemiluminescence images were captured at a resolution of 1200×1200 pixels. For chemiluminescence detection, experiments were conducted in the dark using an aqueous solution containing 0.1 M sodium hydroxide and 0.05 M luminol.

Classical MD simulations

A 1.5 nm-radius nanobubble was initialized in an 8 × 8 × 8 nm box with 200 N2 molecules and water (1 g/cm3). The system was equilibrated under NVT and NPT ensembles (5 ns each), then used for QM/MM MD simulations. Production runs were under NVT at 298.15 K and 1 atm, using the velocity rescale thermostat and Berendsen barostat. The general AMBER force field (GAFF) was applied for OH⁻, •OH, and N2, while water was modeled with the SPCE model. Electrostatics interactions were calculated using the particle mesh Ewald (PME) method with a 10 Å cutoff. A 1 fs timestep and LINCS constraints were applied. Umbrella sampling (US) with a 1500 kJ/(mol·nm2) harmonic restraint was used to calculate the potential of mean force (PMF) of OH⁻ transfer, based on 5 ns of simulation and WHAM analysis. Simulations were performed using GROMACS 2020. The detailed simulation processing procedure is available in the SI Appendix.

QM/MM MD simulations

Structures from classical MD were input into CP2K for QM/MM simulations. OH was treated quantum mechanically (PBE/DZVP-MOLOPT-SR-GTH), while water and N2 were modeled with the SPCE force field. A 450 Ry cutoff was used for plane-wave expansion. Simulations ran in the NVT ensemble at 298.15 K (Nosé-Hoover thermostat), with a 1 fs timestep and periodic boundary conditions. The detailed simulation processing procedure is available in the SI Appendix.

Pollutants degradation

To evaluate pollutant degradation, nitrogen or air microbubbles were generated using a gas dispersion tube (porosity 25–50 µm; Z408743-1EA, Sigma-Aldrich). Gas flow was maintained at 0.3 L/min using either nitrogen or an air pump (AP-80A/40 W; Risheng Technologies Inc.). The microbubbles were introduced into aqueous solutions containing rhodamine B or methylene blue. Pollutant concentrations were monitored by UV-Vis spectrophotometry to determine degradation efficiency.

Nitrogen conversion

Nitrogen-to-nitrate conversion was performed in a double-layer quartz photoreactor was used for nitrate ion generation, with temperature maintained by circulating cooling water through the outer layer. Nitrogen gas was injected at 0.02 MPa into 280 mL of neutral (pH 7) aqueous solution to generate microbubbles. The system was irradiated with a 375 nm mercury lamp. To compensate for water evaporation, distilled water was replenished every three hours. Samples (5 mL) were collected at regular intervals for nitrate quantification ion chromatography (ICS-3000, Thermo Fisher).

Mass spectrometry analysis

To analyze the intermediates in the degradation process of RhB, degradation intermediates of RhB (5 mL) were collected every 3 h. After solid-phase extraction, 100 μL of the sample was taken for mass spectrometry analysis (LTQ-Orbitrap XL, Thermo Fisher Scientific). To detect hydroxyl radical adducts, DMPO (5 μL) was added to 500 mL of pure water, and nitrogen micro-nano bubbles were generated using a circulating micro-nano bubble generator. After irradiating with an ultraviolet light source (375 nm) for 5 minutes, 100 μL of the resulting mixture was collected and analysed using mass spectrometry (Orbitrap Exploris™ 240, Thermo Fisher Scientific).

EPR experimental analysis

10 μL DMPO and 200 μL solution were mixed and reacted for 2 min. The sample was immediately transferred into an EPR capillary tube (1 mm inner diameter). This tube was immediately placed into the cavity of an EPR spectrometer (EMX Plus, Bruker Co.) for spectra acquisition.

Data availability

The data that support the findings of this study, including the instrument parameters and raw image data, are available from the corresponding author upon request. Source data are provided with this paper. The data of all initial and final configurations of the molecular dynamics trajectories in this study have been uploaded to https://zenodo.org/records/16736502. Source data are provided with this paper.

Code availability

The code for the image processing is available from the corresponding author.

References

Andreae, M. O. & Crutzen, P. J. Atmospheric aerosols: Biogeochemical sources and role in atmospheric chemistry. Science 276, 1052–1058 (1997).

Tian, Y.-M., Silva, W., Gschwind, R. M. & König, B. Accelerated photochemical reactions at oil-water interface exploiting melting point depression. Science 383, 750–756 (2024).

Ruiz-Lopez, M. F., Francisco, J. S., Martins-Costa, M. T. C. & Anglada, J. M. Molecular reactions at aqueous interfaces. Nat. Rev. Chem. 4, 459–475 (2020).

Zhong, J. et al. Growth of millimeter-sized 2D metal iodide crystals induced by ion-specific preference at water-air interfaces. Nat. Commun. 15, 3185 (2024).

Chen, X. et al. Sprayed Oil–Water Microdroplets as a Hydrogen Source. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 146, 10868–10874 (2024).

Ren, G., Zhou, M., Hu, P., Chen, J.-F. & Wang, H. Bubble-water/catalyst triphase interface microenvironment accelerates photocatalytic OER via optimizing semi-hydrophobic OH radical. Nat. Commun. 15, 2346 (2024).

Gonella, G. et al. Water at charged interfaces. Nat. Rev. Chem. 5, 466–485 (2021).

Sung, W., Inoue, K., Nihonyanagi, S. & Tahara, T. Unified picture of vibrational relaxation of OH stretch at the air/water interface. Nat. Commun. 15, 1258 (2024).

Rossignol, S. et al. Atmospheric photochemistry at a fatty acid–coated air-water interface. Science 353, 699–702 (2016).

Seki, T. et al. Ions speciation at the water–air interface. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 145, 10622–10630 (2023).

LaCour, R. A., Heindel, J. P., Zhao, R. & Head-Gordon, T. The role of interfaces and charge for chemical reactivity in microdroplets. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 147, 6299–6317 (2025).

Wang, K. & Pera-Titus, M. Microstructured gas-liquid-(solid) interfaces: A platform for sustainable synthesis of commodity chemicals. Sci. Adv. 10, eado5448 (2024).

Zhang, X. H. et al. Degassing and temperature effects on the formation of nanobubbles at the mica/water interface. Langmuir 20, 3813–3815 (2004).

Weijs, J. H. & Lohse, D. Why surface nanobubbles live for hours. Phys. Rev. Lett. 110, 054501 (2013).

Lohse, D. & Zhang, X. Physicochemical hydrodynamics of droplets out of equilibrium. Nat. Rev. Phys. 2, 426–443 (2020).

Brenner, M. P. & Lohse, D. Dynamic equilibrium mechanism for surface nanobubble stabilization. Phys. Rev. Lett. 101, 214505 (2008).

Ji, B., Singh, A. & Feng, J. Water-to-air transfer of nano/microsized particulates: Enrichment effect in bubble bursting jet drops. Nano Lett. 22, 5626–5634 (2022).

Zhou, L. et al. Ultrahigh density of gas molecules confined in surface nanobubbles in ambient water. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 142, 5583–5593 (2020).

Vogel, Y. B. et al. The corona of a surface bubble promotes electrochemical reactions. Nat. Commun. 11, 6323 (2020).

Kathmann, S. M., Kuo, I.-F. W. & Mundy, C. J. Electronic effects on the surface potential at the vapor−liquid interface of water. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 130, 16556–16561 (2008).

Takahashi, M. ζ potential of microbubbles in aqueous solutions: Electrical properties of the gas−water interface. J. Phys. Chem. B 109, 21858–21864 (2005).

Li, J., Xia, Y., Song, X., Chen, B. & Zare, R. N. Continuous ammonia synthesis from water and nitrogen via contact electrification. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 121, e2318408121 (2024).

Bose, S. et al. Understanding the formation of nitrate from nitrogen at the interface of gas–water microbubbles. Chem. Sci. 15, 19764–19769 (2024).

Li, J. et al. Methane C(sp3)–H bond activation by water microbubbles. Chem. Sci. 15, 17026–17031 (2024).

Song, X., Basheer, C., Xu, J., Adam, M. M. & Zare, R. N. Methane bubbled through seawater can be converted to methanol with high efficiency. Adv. Sci. 12, 2412246 (2025).

Park, S. et al. Solutal Marangoni effect determines bubble dynamics during electrocatalytic hydrogen evolution. Nat. Chem. 15, 1532–1540 (2023).

Atkinson, A. J., Apul, O. G., Schneider, O., Garcia-Segura, S. & Westerhoff, P. Nanobubble technologies offer opportunities to improve water treatment. Acc. Chem. Res. 52, 1196–1205 (2019).

Pullanchery, S., Kulik, S., Rehl, B., Hassanali, A. & Roke, S. Charge transfer across C–H⋅⋅⋅O hydrogen bonds stabilizes oil droplets in water. Science 374, 1366–1370 (2021).

Shi, L. et al. Water structure and electric fields at the interface of oil droplets. Nature 640, 87–93 (2025).

Wilson, K. R. & Prophet, A. M. Chemical kinetics in microdroplets. Annu. Rev. Phys. Chem. 75, 185–208 (2024).

Davis, G. E. Scattering of light by an air bubble in water. JOSA 45, 572–581 (1955).

Bhanawat, A., Zhu, K. & Pilon, L. How do bubbles affect light absorption in photoelectrodes for solar water splitting?. Sustain. Energy Fuels 6, 910–924 (2022).

Zhang, P., Chen, C., Feng, M., Sun, C. & Xu, X. Hydroxide and hydronium ions modulate the dynamic evolution of nitrogen nanobubbles in water. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 146, 19537–19546 (2024).

Hamamoto, S., Takemura, T., Suzuki, K. & Nishimura, T. Effects of pH on nano-bubble stability and transport in saturated porous media. J. Contam. Hydrol. 208, 61–67 (2018).

Nirmalkar, N., Pacek, A. W. & Barigou, M. On the existence and stability of bulk nanobubbles. Langmuir 34, 10964–10973 (2018).

Meegoda, J. N., Aluthgun Hewage, S. & Batagoda, J. H. Stability of nanobubbles. Environ. Eng. Sci. 35, 1216–1227 (2018).

Shi, Y.-R., Ye, M.-P., Du, L.-C. & Weng, Y.-X. Experimental determination of particle size-dependent surface charge density for silica nanospheres. J. Phys. Chem. C. 122, 23764–23771 (2018).

Duval, J. F., Merlin, J. & Narayana, P. A. Electrostatic interactions between diffuse soft multi-layered (bio)particles: Beyond Debye–Hückel approximation and Deryagin formulation. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 13, 1037–1053 (2011).

Fang, Z. et al. Evolution of light-induced vapor generation at a liquid-immersed metallic nanoparticle. Nano Lett. 13, 1736–1742 (2013).

Carlson, M. T., Green, A. J. & Richardson, H. H. Superheating water by CW excitation of gold nanodots. Nano Lett. 12, 1534–1537 (2012).

Padilla-Martinez, J. P., Berrospe-Rodriguez, C., Aguilar, G., Ramirez-San-Juan, J. C. & Ramos-Garcia, R. Optic cavitation with CW lasers: A review. Phys. Fluids 26, 122007 (2014).

Kusaka, R., Nihonyanagi, S. & Tahara, T. The photochemical reaction of phenol becomes ultrafast at the air–water interface. Nat. Chem. 13, 306–311 (2021).

Takahashi, M., Chiba, K. & Li, P. Formation of hydroxyl radicals by collapsing ozone microbubbles under strongly acidic conditions. J. Phys. Chem. B 111, 11443–11446 (2007).

Takahashi, M., Chiba, K. & Li, P. Free-radical generation from collapsing microbubbles in the absence of a dynamic stimulus. J. Phys. Chem. B 111, 1343–1347 (2007).

Minamoto, C. et al. Effect of acidic conditions on decomposition of methylene blue in aqueous solution by air microbubbles. Chemosphere 263, 128141 (2021).

Li, P., Takahashi, M. & Chiba, K. Degradation of phenol by the collapse of microbubbles. Chemosphere 75, 1371–1375 (2009).

Litman, Y., Chiang, K.-Y., Seki, T., Nagata, Y. & Bonn, M. Surface stratification determines the interfacial water structure of simple electrolyte solutions. Nat. Chem. 16, 644–650 (2024).

Zhang, P., Feng, M. & Xu, X. DoUble-layer Distribution Of Hydronium And Hydroxide Ions In The Air–water Interface. ACS Phys. Chem. Au 4, 336–346 (2024).

Chamberlayne, C. F. & Zare, R. N. Simple model for the electric field and spatial distribution of ions in a microdroplet. J. Chem. Phys. 152, 184702 (2020).

Colussi, A. J. Mechanism of hydrogen peroxide formation on sprayed water microdroplets. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 145, 16315–16317 (2023).

Liu, Y. et al. Strong electric field force at the air/water interface drives fast sulfate production in the atmosphere. Chem 10, 330–351 (2024).

Xiong, H., Lee, J. K., Zare, R. N. & Min, W. Strong electric field observed at the interface of aqueous microdroplets. J. Phys. Chem. Lett. 11, 7423–7428 (2020).

Rao, Z. et al. Accelerated photolysis of H2O2 at the air–water interface of a microdroplet. J. Am. Chem. Soc. https://doi.org/10.1021/jacs.3c08101 (2023).

Heindel, J. P., Hao, H., LaCour, R. A. & Head-Gordon, T. Spontaneous formation of hydrogen peroxide in water microdroplets. J. Phys. Chem. Lett. 13, 10035–10041 (2022).

Li, K. et al. Spontaneous dark formation of OH radicals at the interface of aqueous atmospheric droplets. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 120, e2220228120 (2023).

Winter, B., Faubel, M., Vácha, R. & Jungwirth, P. Behavior of hydroxide at the water/vapor interface. Chem. Phys. Lett. 474, 241–247 (2009).

Hao, H., Leven, I. & Head-Gordon, T. Can electric fields drive chemistry for an aqueous microdroplet?. Nat. Commun. 13, 280 (2022).

Nauman, J. A., Suvlu, D. & Willard, A. P. Electric fields at solid-liquid interfaces: Insights from molecular dynamics simulation. Annu. Rev. Phys. Chem. 76, 181–202 (2025).

Chen, S. et al. Direct electroconversion of air to nitric acid under mild conditions. Nat. Synth. 3, 76–84 (2024).

Acknowledgements

We thank the National Natural Science Foundation of China (22225602, 52293441, and 51821006) for their support. This work was partially carried out at the Instruments Center for Physical Science, USTC. We acknowledge Dr. Fang Liu from Guangzhou University of Chinese Medicine for providing GL-1 chemiluminescence molecule.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

S.Y.Y., and X.W.L. designed and analyzed the experiments. S.Y.Y. performed the experiments. W.W and J.J.C. carried out the theoretical calculations and simulations. S.Y.Y., W.W., J.J.C., and X.W.L. discussed the results. S.Y.Y., W.W., J.J.C., J. S. F., and X.W.L. wrote the manuscript. All the authors contributed to the manuscript.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Peer review

Peer review information

Nature Communications thanks Feng Wang, Richard Zare, and the other, anonymous, reviewer(s) for their contribution to the peer review of this work. A peer review file is available.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Source data

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Yang, SY., Wang, W., Chen, JJ. et al. Probing catalyst-free hydroxyl radical generation at microbubble interfaces. Nat Commun 16, 8835 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-025-63899-w

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-025-63899-w