Abstract

The ability of transcription factors to recognize diverse DNA sequences while maintaining binding specificity is required for gene regulation, but the molecular mechanism enabling this flexibility remains poorly understood. Here, we show that the DNA-binding domain of transcription factor AflR employs a structured zinc cluster motif and disordered terminal regions to achieve sequence-diverse DNA recognition. Using NMR spectroscopy, molecular dynamics simulations, and biochemical approaches, we demonstrate that the DNA-binding domain of AflR contains a structured zinc cluster core flanked by dynamic terminal regions. Two AflR DNA-binding domain monomers recognize inverted CG half-sites, with the zinc cluster motif providing sequence-specific anchoring while dynamic termini optimize binding through distributed interactions. While DNA binding induces overall stabilization, the terminal regions retain conformational flexibility in the bound state, enabling adaptation to sequence variations. Both zinc cluster and C-terminal residue mutations significantly disrupt the stability of the complex. Notably, the C-terminal region functions as a conformational hub coordinating structural changes required for stable complex formation with diverse target sequences. This work demonstrates how intrinsic disorder enables transcription factor sequence-diverse recognition while maintaining specificity, providing insight into the molecular basis of multi-target gene regulation.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Transcription factors (TFs) bind to specific DNA sequences to regulate gene expression, forming the foundation of transcriptional regulation that enables cells to respond to environmental signals and maintain homeostasis1. DNA binding is primarily mediated by DNA-binding domains (DBDs), which interact with specific DNA motifs via distinct interaction interfaces2. While most TFs recognize a limited set of closely related DNA sequences, some display the remarkable ability to bind diverse DNA sequences while maintaining regulatory specificity3,4,5. This sequence-diverse recognition raises fundamental questions about the molecular basis of DNA binding specificity. While traditional models have emphasized the role of well-defined structural interfaces in TF-DNA recognition, emerging evidence suggests that intrinsically disordered regions (IDRs), which lack stable secondary structure, are essential for enabling these dynamic interactions6,7. Understanding how structured domains and IDRs cooperate to enable sequence-diverse DNA recognition is a central challenge in elucidating the molecular basis of transcriptional regulation.

IDRs are particularly abundant in eukaryotic TFs, with over 80% containing disordered regions, compared to only 5% of bacterial TFs8. While IDRs have traditionally been associated with protein-protein interactions, recent studies reveal their direct involvement in DNA recognition and binding specificity9,10. The inherent flexibility of IDR allows TFs to adopt multiple conformations, facilitating interactions with diverse DNA sequences. For example, yeast TFs Msn2 and Yap1 utilize IDRs to bind to distinct promoter sequences selectively6,11. Similarly, the herpes viral TF ICP4 employs IDR alongside its globular DNA-binding domain to modulate DNA recognition specificity12. In the case of the Ets-1 transcription factor, its serine- and arginine-rich IDR alters the flexibility of its binding interface, changing DNA binding affinity by 100–1000 fold through transient interactions13. These examples highlight how structural disorder can enhance, rather than compromise, both binding specificity and plasticity. Despite these advances, the molecular mechanisms by which IDRs collaborate with structured domains to facilitate sequence-diverse DNA recognition remain poorly understood, particularly regarding how conformational flexibility contributes to binding adaptability and specificity.

Zinc cluster proteins represent an important family of eukaryotic TFs that serve as models for sequence-diverse DNA recognition. These TFs frequently regulate multiple genes, particularly in secondary metabolism, where they control biosynthetic gene clusters. Zinc cluster proteins are characterized by a highly conserved CysX2CysX6CysX5-12CysX2CysX6-8Cys motif that coordinates two zinc ions to form a DNA-binding module14. The zinc cluster family has evolved diverse DNA recognition strategies, with members exhibiting two primary binding modes. Many zinc cluster proteins function as homodimers, recognizing inverted (5′-CGGNxCCG-3′, where N represents any nucleotide), everted (5′-CCGNxCGG-3′), or direct repeats (5′-CGGNxCGG-3′) CGG half-sites through coiled-coil interactions14. In contrast, some family members operate as monomers, utilizing flexible regions to bind extended DNA sequences15,16,17,18. Recent structural studies of monomeric zinc cluster TFs suggest that disordered regions provide essential structural plasticity for engaging multiple DNA sequences17,18. This structural diversity within the zinc cluster family offers unique opportunities to understand how protein structural elements, including disordered regions, enable different modes of DNA recognition.

One such zinc cluster TF, AflR from Aspergillus species, provides an intriguing example of sequence-diverse DNA recognition. AflR regulates at least 17 genes within the aflatoxin biosynthesis gene cluster, binding to palindromic sequences across different promoters19,20. Early studies on AflR from A. nidulans revealed binding to the palindromic sequence 5′-TCGN₅CGA-3′21. This finding was later extended through studies of A. parasiticus AflR, which identified a preference for 5′-TCGSWNNSCGR-3′ sequences (where S represents G/C, W represents A/T, and R represents A/G)22. Recent chromatin immunoprecipitation sequencing in A. flavus revealed binding to an 18-bp palindromic sequence containing overlapping recognition motifs20. Genetic studies demonstrate that AflR deletion dramatically reduces aflatoxin production and affects fungal development, establishing its central regulatory role23. Notably, while AflR binds palindromic sequences typically associated with homodimeric zinc cluster TFs, it lacks the predicted helical secondary structure for dimerization24. This observation raises the possibility that AflR employs a distinct recognition mechanism, potentially involving disordered regions.

Here, we investigate the structural and dynamic properties of AflR’s DNA-binding domain (AflR-DBD) and its interactions with three target promoters ver1, vbs, and norA, which are the representative biosynthetic genes within the aflatoxin gene cluster. Through integrated analysis using NMR spectroscopy, molecular dynamics simulations, and biochemical approaches, we reveal how a structured zinc cluster core and disordered terminal regions enable sequence-diverse DNA recognition. Our findings provide insights into how IDRs expand transcription factor recognition capabilities while maintaining specificity. This work advances our understanding of IDR-mediated transcriptional regulation and establishes principles for targeting strategies to control aflatoxin production in agriculturally important fungi.

Results

AflR contains a flexible DNA-binding domain

Initial bioinformatics analysis of AflR (residues 1–444) revealed distinct structural features within its N-terminal region that surround the zinc cluster motif (Supplementary Fig. 1a). Secondary structure predictions identified two short α-helices within the zinc cluster motif, while the surrounding regions showed predominantly coiled structures (Supplementary Fig. 1b). Disorder predictions further indicated that most of the N-terminus, except for the zinc cluster motif, possessed intrinsically disordered characteristics (Supplementary Fig. 1c). Notably, unlike typical zinc cluster proteins that recognize two CG half-sites through coiled-coil mediated dimerization, AflR showed no significant propensity for coiled-coil formation near its N-terminus despite its demonstrated ability to bind two CG half-sites (Supplementary Fig. 1d, e). This unexpected finding aligned more closely with the structural characteristics of monomeric zinc cluster proteins interacting with single CG sites.

Based on comparative sequence analysis with well-characterized zinc cluster proteins (Supplementary Fig. 2), we designed a series of truncation constructs (8–98, 15–88, 15–79, 15–69, 26–79) that systematically span potential DNA-binding domain boundaries for both dimeric (residues 26–95) and monomeric (residues 15–74) binding modes (Fig. 1a, Supplementary Fig. 2). Size exclusion chromatography (SEC) revealed that all truncations eluted as monomers (Fig. 1b, c), similar to the monomeric zinc cluster protein Pho7 (Supplementary Fig. 3). Analysis of DNA binding using the ver1 promoter, a well-established strong binding target of AflR, showed that constructs 8–98, 15–88, and 15–79 formed stable complexes, while truncations 15–69 and 26–79 displayed reduced binding capacity (Fig. 1d)22. Fluorescence correlation spectroscopy (FCS) with Cy3-labeled ver1 DNA quantified these differences. Systematic increases in molecular diffusion time (τ) with protein concentration demonstrated complex formation (Supplementary Fig. 4), yielding dissociation constants (KD) of 408.8 ± 137.1 nM, 400.9 ± 54.5 nM, 1505.3 ± 250.0 nM, and 4017.0 ± 594.0 nM for fragments 8–98, 15–79, 15–69, and 26–79, respectively (Fig. 1e). These results corroborated the SEC observations: fragments 8–98 and 15–79 displayed comparable binding affinities, while further truncation resulted in substantially reduced affinity for the target DNA.

a Domain architecture of AflR (1–444) showing the zinc cluster motif (29–56) and truncation constructs designed for functional mapping. b SDS-PAGE analysis of purified TRX-tagged AflR truncations. The experiments have been repeated independently three times, and one representative result is shown. c Size exclusion chromatography (SEC) profiles of TRX-tagged AflR truncations with molecular weight standards. d Analytical gel filtration chromatography profiles of TRX-tagged AflR truncation interactions with the ver1 promoter DNA. Complex peaks (black arrow), free DNA peak (green arrow), and free protein peak (gray arrow) are indicated. Absorbance at 280 nm (mAU) indicates components eluting at different retention volumes. e Binding affinity determination using FCS titration of Cy3-labeled ver1 promoter with AflR truncations. Error bars represent the Mean ± SD from three independent experiments. f Far-UV CD spectra of AflR 8–98 and 15–79. Error bars represent the Mean ± SEM from three independent measurements. g 1H-15N HSQC spectrum demonstrating partial disorder in AflR 15–79. Black labels indicate zinc cluster residues, blue labels show N-terminal residues, cyan labels show C-terminal residues. h Secondary structure propensity calculated from Cα and Cβ chemical shifts. i MD simulation-derived conformational ensemble showing the six most populated states with their relative populations. Helical regions are shown in blue, dynamic terminal regions are shown in red, zinc ions are shown in gold. j T1/T2 ratios of 15N-labeled AflR-DBD. T₁ and T₂ relaxation rates were estimated by fitting the peak intensities to single exponential decays. Error bars represent the uncertainty in relaxation rates derived from the fitting procedure45. k 1H-15N heteronuclear NOE of 15N-labeled AflR-DBD. NOE values were determined as the ratio of peak intensities in spectra recorded with and without proton saturation. Error bars were calculated based on the standard deviation of noise in the saturated and unsaturated spectra using error propagation. For (c–f), colors consistently represent AflR truncations: 8–98 (blue), 15–88 (green), 15–79 (yellow), 15–69 (pink), and 26–79 (purple).

Secondary structure analysis using far-UV circular dichroism (CD) spectroscopy revealed similar characteristics for fragments 8–98 and 15–79. Both displayed a minor peak at 222 nm, indicating limited helical content likely corresponding to the zinc cluster motif helices, along with a pronounced negative molar ellipticity minimum at 202 nm, suggesting a predominantly disordered structure (Fig. 1f). Notably, the relatively higher negative molar ellipticity observed at 202 nm for fragment 8–98 compared to fragment 15–79 suggests a more significant proportion of unstructured regions in the longer construct. These spectroscopic data aligned well with our initial bioinformatics predictions and supported a model wherein localized structure within the zinc cluster motif exists within a predominantly disordered context. Based on these analyses, we identified fragment 15–79 as the minimal region maintaining optimal DNA binding while preserving essential structural features, designating it AflR-DBD.

To corroborate the monomeric nature of AflR-DBD, we performed native mass spectrometry analysis. The spectrum revealed three well-defined peaks corresponding to different charge states (z = 5, 6, and 7) of the protein following tag removal (Supplementary Fig. 5). The calculated average molecular masses derived from these peaks (7789.75–7791.77 Da) demonstrated excellent agreement with the theoretical average molecular mass of monomeric AflR-DBD coordinated with two zinc ions (7789.5 Da). This precise mass correlation, combined with our SEC data showing monomeric elution profiles for all AflR truncations (Fig. 1c, Supplementary Fig. 3), provides compelling evidence that AflR-DBD exists as a monomer in solution prior to DNA binding.

The structural properties of AflR-DBD were further characterized through multidimensional NMR spectroscopy. The ¹H-¹⁵N HSQC spectrum exhibited a distinctive pattern wherein several peaks corresponding to the zinc cluster motif showed notable dispersion in the ¹H dimension (8.5–10 ppm, black labels), while the majority of signals displayed limited amide proton chemical shift dispersion, consistent with significant conformational flexibility (Fig. 1g)25,26. Chemical shift-based secondary structure propensity (SSP) analysis revealed strong α-helical propensity within the zinc cluster motif, while the remainder exhibited weak structural propensities, confirming the predominantly disordered nature of regions outside the zinc-binding core (Fig. 1h). These observations agreed with sequence-based secondary structure and disorder predictions.

The dynamic nature of AflR-DBD, coupled with limited side-chain assignments and sparse NOE signals, presented significant challenges for conventional structure determination methods (Supplementary Fig. 6). To overcome these limitations and gain deeper insights into the protein’s conformational landscape, we conducted extensive all-atom molecular dynamics (MD) simulations. Three independent 18 μs trajectories were generated using NMR-derived restraints, yielding a total simulation time of 54 μs. The robustness of our computational approach was validated through a comparison of predicted chemical shifts and secondary chemical shifts (SCSs) of Cα with experimental values, showing excellent agreement that matched or exceeded the accuracy of previous simulation studies of similarly challenging systems (Supplementary Fig. 7)25,26.

The conformational ensemble of AflR-DBD was systematically characterized through root-mean-square deviation (RMSD)-based hierarchical clustering analysis of the MD trajectories. The RMSD of backbone atoms was used as the distance metric to optimize the resolution of conformational clustering, resulting in the selection of a 0.7 nm cutoff value (Supplementary Fig. 8). The top six clusters (C1-C6), accounting for 82.0% of all sampled conformations, revealed the dominant structural states accessible to the protein (Fig. 1i). All clusters showed consistent zinc cluster motifs with two short α-helices connected by a geometrically constrained loop region. Analysis of backbone torsion angles in the connecting loop region identified significant populations of polyproline II helical conformations in several residues (37, 39, 43, 45, 46), with residue 40 adopting a left-handed helical conformation (Supplementary Fig. 9a). These non-canonical structural elements, stabilized by specific hydrogen bonds (Supplementary Fig. 9b), collectively contribute to the elevated secondary structure propensity observed in our NMR experiments (Fig. 1h), despite the region lacking canonical α-helical structure. In contrast, the N- and C-terminal regions displayed significant conformational variability. This observation was further substantiated by root-mean-square fluctuation (RMSF) analysis across the three independent trajectories, which demonstrated high RMSF values in the terminal regions, indicating substantial flexibility, while the central region encompassing the zinc cluster motif displayed relatively lower RMSF values, suggesting a more stable core structure (Supplementary Fig. 10).

To validate these computational findings, we conducted backbone dynamics analysis of AflR-DBD using NMR 15N relaxation and heteronuclear NOE experiments. The T1/T2 ratio, which serves as an indicator of molecular tumbling and local conformational dynamics, exhibited higher values for residues corresponding to the zinc cluster motif, consistent with restricted motion characteristic of structured elements (Fig. 1j)26. In contrast, both terminal regions (residues 15–26 and 60–79) displayed notably lower T1/T2 values, reflecting enhanced molecular mobility. Complementary heteronuclear NOE measurements revealed positive values (>0.6) across the zinc cluster region, further confirming its structured nature, while terminal regions demonstrated reduced or negative NOE values, a hallmark of significant conformational flexibility (Fig. 1k). Remarkably, the residue-specific mobility pattern observed in the NMR dynamics data closely mirrors the RMSF profile derived from MD simulations (Supplementary Fig. 10). The combined NMR experimental data and MD simulation analyses thus paint a picture of AflR-DBD as a partially disordered protein characterized by a stable zinc-binding core flanked by highly dynamic terminal regions.

AflR-DBD employs unique inverted binding for sequence-diverse DNA recognition

The interaction between AflR-DBD and target DNA was first characterized through NMR titration experiments. The stepwise addition of unlabeled DNA to ¹⁵N-labeled AflR-DBD resulted in significant line broadening for most peaks in the ¹H-¹⁵N HSQC spectrum, a phenomenon attributable to increased effective correlation time, restricted conformational motion, or exchange between free and bound states on the microsecond to millisecond timescales (Fig. 2a and Supplementary Fig. 11)25. The limited chemical shift changes during titration suggested that AflR-DBD maintains substantial conformational flexibility even when bound to DNA. Previous studies identified that AflR recognizes sequences containing the motif 5′-TCGN₅CGA-3′ with two CG half-sites, suggesting the possibility of a complex binding mode involving multiple protein molecules. To investigate this hypothesis, we employed a modified EMSA approach using differently tagged AflR-DBD constructs to investigate binding stoichiometry27. Analysis of three target promoters (ver1, vbs, and norA) consistently showed an intermediate band between the TRX-tagged and His-tagged protein-DNA complexes (Fig. 2b), demonstrating that two AflR-DBD molecules bind each DNA target. This conclusion was further supported by isothermal titration calorimetry (ITC) measurements, showing a 1:2 DNA: protein binding ratio (N = 0.5, Supplementary Fig. 12). The experiments revealed comparable dissociation constants across promoters, with slightly stronger binding observed for the ver1 promoter (Supplementary Fig. 12 and 13).

a NMR titration experiments showing the 1H-15N HSQC spectra of AflR 15-79 alone (pink) and with ver1 promoter DNA at a 1:0.05 ratio (green). b Organization of the AF gene cluster and sequence logo of DNA binding sites in ver1, vbs, and norA promoter regions. ver1 contains a typical inverted CG site (5′-CGGN3CCG-3′), while vbs and norA have a 5′-CGGN3GCG-3′ motif. Gels showing the EMSA results of TRX-tagged and His-tagged AflR 15-79 constructs binding to the promoter DNAs. c Systematic DNA mutations designed to probe binding orientation specificity. d EMSA analysis showing both CG sites are essential for complex formation. e The mutations mimicking a typical direct repeat (5′-CGGN3CGG-3′) disrupt AflR-DNA interaction. f The mutations mimicking the inverted repeat (5′-CGGN3CCG-3′) maintain binding similar to wild-type. g The mutations of the second CG site (GCG/CCG to ACG or GCA/CCA) show that ACG maintains a binding affinity similar to the wild-type, while GCA or CCA decreases the binding affinity. h DNA truncation experiments test the functional significance of individual CG Site A or Site B. Cyan arrows indicate residual complex formation. The EMSA assays have been repeated independently three times, and one representative result is shown.

Sequence analysis revealed that the three promoters share a conserved 5′-TCGGN₃SCGA-3′ motif (Fig. 2b). The ver1 promoter contains a perfect inverted repeat (5′-CGGTCTCCG-3′), while vbs and norA harbor a variant motif (5′-CGGN₃GCG-3′). This organization resembles canonically inverted CG half-sites recognized by dimeric zinc cluster proteins (Supplementary Fig. 14a–c). To determine the binding orientation and examine the functional significance of sequence variations, we conducted mutational analysis (Fig. 2c). EMSA experiments showed that mutation of either CG site disrupted complex formation across all promoters (Fig. 2d), establishing that both sites are essential for the interaction. These results support an inverted binding orientation, as the requirement for both CG sites is consistent with the notion that the two AflR-DBD molecules bind in opposite orientations on the DNA.

Notably, mutations creating direct repeat configurations (5′-CGGN₃CGG-3′) abolished the binding of two AflR-DBD molecules (Fig. 2e) while converting the vbs and norA variant sites to typical inverted repeats (5′-CGGN₃CCG-3′) maintained binding comparable to wild-type sequences (Fig. 2f). Detailed examination of the second CG site revealed differential effects of specific base changes: while mutation of SCG to ACG preserved wild-type binding affinity, alteration to SCA significantly reduced binding (Fig. 2g). This pattern indicated that the terminal G in the second CG site plays a more critical role in AflR-DBD binding than the preceding base, providing additional validation of the inverted half-site polarity model.

To further characterize the contribution of individual half-sites to AflR-DBD binding, we performed EMSA analysis using truncated DNA constructs containing either Site A or Site B for each promoter. While both sites showed evidence of interaction with AflR-DBD, as indicated by decreased free DNA intensity, neither site alone was sufficient to form stable complexes comparable to those observed with AflR-DBD (Fig. 2h). Interestingly, promoter-specific differences in single-site interactions were observed. ver1 showed negligible complex formation with either individual site, whereas vbs exhibited weak complex formation with Site A, and norA displayed detectable interaction with Site B. These observations correlate with our CG mutation results (Fig. 2d), where ver1 binding was completely abolished upon mutation of either site, while vbs retained minimal binding with Mut2 (intact Site A) and norA maintained weak interaction with Mut1 (intact Site B). Overall, these results collectively support a model of AflR-DNA interaction in which two monomeric AflR-DBD molecules bind to promoter DNA containing two half CG sites in an inverted orientation.

AflR-DBD retains terminal region flexibility in DNA-bound states

To elucidate the atomic-level details of AflR-DBD’s interactions with target DNA sequences, we developed a structural modeling strategy guided by conserved geometric relationships between zinc cluster motifs and CG bases observed in existing protein-DNA complexes (Supplementary Fig. 14d). Initial MD simulations of promoter DNAs generated accessible conformations of CG sites (Supplementary Fig. 15). However, direct docking and alignment attempts failed to generate viable complexes due to steric clashes between the protein and DNA backbone (Supplementary Fig. 16). To overcome this challenge, we employed steered MD simulations of AflR-DBD to optimize protein conformations for alignment (Supplementary Fig. 17). The zinc cluster motifs were then aligned to DNA CG sites using the Ppr1-DNA complex structure as a template, followed by 50 ns simulations allowing terminal regions to establish contacts (Supplementary Fig. 17)28.

Extended MD simulations (12 μs per promoter) revealed distinct binding patterns for each complex. RMSD analysis indicated generally consistent behavior across the three DNA complexes. After an initial equilibration phase, AflR-DBD at both CG sites (A and B, Fig. 2b) displayed reduced fluctuations compared to the free protein (Supplementary Figs. 8a, 18a, b, 19a, b, and 20a, b). RMSF analysis demonstrated that DNA binding significantly reduced conformational flexibility across most residues, particularly in the zinc cluster motif region (residues 30–60, Supplementary Figs. 10, 18c, d, 19c, d, and 20c, d). However, the terminal regions (residues 15–25 and 65–79) maintained substantial flexibility, especially in the vbs and norA complexes, consistent with observations from the NMR titration experiments (Fig. 2a and Supplementary Fig. 11).

The conformational ensembles of AflR-DBD/DNA complexes were characterized using RMSD-based hierarchical clustering analysis (Supplementary Fig. 21). The results revealed distinct structural ensembles for each promoter complex, characterized by two AflR-DBD molecules bound to DNA in an inverted orientation with zinc cluster motifs engaging the CG sites within the major grooves (Fig. 3a–c). The ver1 and vbs complexes showed relatively stable conformations, with their top three clusters representing approximately 90% of the sampled states (Fig. 3a, b). The norA complex exhibited greater conformational variability (Fig. 3c). Notably, while the core binding region remained stable, the tail regions of AflR-DBD exhibited conformational fluctuations across all complexes. The structural diversity observed within each ensemble suggests that AflR-DBD retains significant conformational flexibility even when bound to DNA. Furthermore, the dominant binding conformations showed relative differences among the ver1, vbs, and norA complexes, indicating that AflR-DBD residues adapt their binding mode to accommodate sequence variations across different promoters (Fig. 3a–c).

a–c MD-derived structural ensembles showing binding modes of ver1, vbs, and norA complex. Major conformational clusters are shown with their relative populations. In each panel, two AflR-DBD molecules bind to DNA (gray) in an inverted orientation, with binding sites labeled as A and B (blue letters). Cyan arrows indicate regions of conformational variability. d–f NMR relaxation dynamics of AflR-DBD bound to ver1, vbs, and norA promoter (pink). NMR relaxation dynamics of AflR-DBD in free state (gray, from Fig. 1j, k) are shown for comparison. T₁ and T₂ relaxation rates were estimated by fitting the peak intensities to single exponential decays, with error bars representing the uncertainty derived from the fitting procedure. NOE values were determined as the ratio of peak intensities in spectra recorded with and without proton saturation, with error bars calculated based on the standard deviation of noise in the saturated and unsaturated spectra using error propagation45. Cyan arrows highlight residues with differential binding-induced changes in dynamics.

To experimentally validate these computational observations, we conducted comparative NMR relaxation experiments. Building upon our initial characterization of free AflR-DBD dynamics (Fig. 1j, k), we measured T1/T2 relaxation ratios and heteronuclear 1H-15N NOE values for the protein in complex with each promoter (Fig. 3d–f). The T1/T2 relaxation data reveal that the fundamental dynamic profile of AflR-DBD persists upon DNA binding, with zinc cluster residues maintaining restricted mobility while terminal regions retain significant flexibility. Notably, we observed promoter-specific alterations in dynamics for some residues, such as R63 exhibited increased T1/T2 values when bound to vbs and norA promoters but not ver1, while G65 and R66 showed substantial increases exclusively in the norA complex. These residue-specific, promoter-dependent dynamic changes suggest localized conformational adaptations that optimize interactions with distinct DNA sequences.

The heteronuclear NOE measurements further corroborate these findings, with zinc cluster motif residues consistently displaying positive NOE values in both free and bound states, while terminal regions maintain reduced NOE values indicative of preserved flexibility (Fig. 3d–f). We note that measurement uncertainties are inherently larger for DNA-bound states due to signal attenuation from complex formation, a technical challenge in NMR studies of biomolecular interactions. Nevertheless, the overall dynamic patterns remain interpretable and provide direct experimental evidence that AflR-DBD retains significant conformational plasticity in its terminal regions even when engaged with DNA. These distinct promoter-dependent dynamic signatures strongly support our computational model of sequence-adaptive recognition through conformationally flexible terminal regions.

Terminal regions enable sequence-diverse DNA recognition via distributed interactions

To further elucidate the interaction patterns between AflR-DBD and the promoter DNAs, we conducted a contact map analysis. The residue contacts plots showed that while zinc cluster motifs make conserved interactions with CG sites, terminal regions display promoter-specific binding patterns (Supplementary Fig. 22). At site A, both termini primarily contact the 3′-end of DNA, while at site B, they engage the 5′-end (sense strand sequences are shown in Fig. 2b). The C-terminal region at site B shows adaptability, interacting with both 5′ and 3′ DNA ends in different promoters, particularly in the ver1 and vbs promoters (Supplementary Fig. 22a, b, arrows). From the structural analysis, we observed a conformational shift in the C-terminal region of AflR-DBD across different clusters. For instance, in the ver1 complex, the C-terminal region interacted with the 3′-end of the DNA at site B in clusters C1 and C2, while in cluster C3, it interacted with the 5’-end (Fig. 3a, Supplementary Fig. 22a, arrows). However, this conformational shift was less pronounced in the vbs complex (Fig. 3b, Supplementary Fig. 22b) and minimally observed in the norA complex (Fig. 3c and Supplementary Fig. 22c). These findings suggest that the conformational flexibility of the C-terminal region of AflR-DBD, particularly when bound at site B, depends on the specific promoter.

To understand the molecular basis of AflR-DBD’s differential interactions with various target sequences, we conducted comparative analysis across ver1, vbs, and norA promoter regions. Differential residue contact mapping, using ver1 as a reference, revealed distinct binding patterns among the three promoters (Fig. 4a). While zinc cluster motif interactions remained largely conserved, both terminal regions showed marked differences in their interaction patterns. Notably, in the vbs and norA complexes, AflR-DBD molecules bound at site B demonstrated enhanced contacts with 5′ DNA sequences (Fig. 4a, arrows), whereas, in the ver1 complex, site B interactions favored 3′ DNA sequences. This differential binding pattern correlated with variation in the site B motif sequence (CCG in ver1 versus GCG in vbs and norA). To validate these computational observations experimentally, we designed and tested DNA truncation constructs targeting the 3′ and 5′ regions. EMSA analysis showed that deletion of 5′-end sequences more severely impacted AflR-DBD interactions with vbs and norA compared to ver1, while 3′-end deletions showed the opposite effect (Fig. 4b). Quantitative analysis of complex formation ratios between 3′-Del and 5′-Del truncations precisely mirrored the interaction patterns predicted by our MD simulations.

a Differential residue contact maps highlight differences in interaction patterns between AflR-DBD binding to vbs vs. ver1 and norA vs. ver1 promoter regions. The y-axis represents residues from AflR-DBD molecules bound at site A and site B. The x-axis labels C and D denote sense and antisense DNA strands. Red indicates higher contact probability in vbs or norA, while blue represents higher contact probability in ver1. Cyan arrows highlight key differential contacts in the terminal regions. b DNA truncation analysis quantifying the relative importance of 5′ vs. 3′ contacts across promoters. Schematic representation of 3′-deletion (3′-Del) and 5′-deletion (5′-Del) constructs are shown with conserved CG sites highlighted in color. EMSA results demonstrate differential effects of these truncations across the three promoters. The ratio of stable complex band intensity (arrows) for 3′-deletion vs. 5′-deletion constructs is quantified in the graph. EMSA experiments were performed independently in triplicate, with one representative image shown and quantitative ratios from all three experiments plotted. c Mutational analysis identifies key residues required for DNA recognition. Binding curves from EMSA titration experiments show differential effects of mutations in the N-terminal (R23A, D27A), zinc cluster (K36A, V37A), and C-terminal regions (R63A, G65A, R66A) across all three promoters. Error bars represent the Mean ± SEM from three independent experiments.

To gain deeper insight into the molecular details of these interactions, we integrated NMR experimental data with MD simulations for analysis and revealed distinct interaction profiles for each promoter (Supplementary Fig. 23). Comparative analysis of NMR signal intensity reduction upon DNA binding with maximum contact ratios derived from simulations showed remarkable correlation in specific regions (Supplementary Fig. 23), identifying key interaction sites distributed from the N-terminal region (residues 23, 27, 28) to the C-terminal region (residues 61, 62, 62, 63, 65, 66). Although the zinc cluster motif (residues 35-38) was not highlighted by this comparative analysis approach, our MD simulations consistently identified these residues as forming significant contacts with DNA across all three promoters.

To elucidate how key residues achieve sequence-adaptive recognition, we performed interaction fingerprinting analysis using ver1 as the reference for quantitative comparison. This analysis revealed distinct interaction strategies across different promoter sequences. Notably, R63 from AflR-DBD molecules bound at site B demonstrated dramatic changes in interaction patterns, showing substantially reduced cationic interactions in vbs (1.02% with A15C vs 54.45% with T16C in ver1, Supplementary Table 1) while establishing extensive van der Waals (VdW) contacts in norA (62.76% with A14C vs 7.22% with T14C in ver1, Supplementary Table 2). R23 from site B formed the most significant interactions in norA, exhibiting 79.73% cationic interactions with A20D compared to only 0.04% with A19D in ver1. R66 from site A exhibited reduced contacts in vbs (30.77% VdW with G20C vs 72.83% with G21C in ver1), while R66 from site B formed extensive interactions in vbs (30.90% VdW with A13C vs 0.22% with T14C in ver1). D27 from site A maintained strong interactions in ver1 but showed minimal engagement in vbs, whereas D27 from site B enhanced hydrogen bonding in norA (68.20% with A16C vs 20.74% with T16C in ver1). K62 from site A demonstrated reduced cationic interactions in norA (6.80% with T14D vs 43.78% with A13D in ver1). These results demonstrate sequence-adaptive recognition through residue-specific modulation of interaction types.

To experimentally validate the functional significance of these identified residues, we performed site-directed mutagenesis followed by quantitative EMSA titration analysis (Fig. 4c). The binding curves and calculated apparent dissociation constants (KD-app, Supplementary Table 3) revealed sequence-dependent effects across the tested regions of AflR-DBD. N-terminal mutations (R23A, D27A) showed moderate effects on binding (1.2–10.3 μM²), with R23A slightly enhanced binding to vbs and norA while reducing affinity for ver1. Mutations within the zinc cluster motif (K36A, V37A) substantially reduced binding to all promoters. K36A showing a ~1.8-fold difference between its effects on ver1 (30.6 ± 5.72 μM²) and vbs (17.3 ± 0.32 μM²). Similarly, V37A affected binding to ver1 (11.3 ± 3.33 μM²) differently than to vbs and norA (~16 μM²). Notably, C-terminal mutations displayed both the most severe and sequence-dependent effects on complex formation. R63A showed ~1.8-fold variation in KD-app values between ver1 (39.5 ± 16.4 μM²) and norA (72.3 ± 16.5 μM²). Most dramatically, R66A exhibited a ~3.4-fold difference between its impact on vbs (58.1 ± 22.6 μM²) and norA (197.9 ± 196.7 μM²), with substantially higher variability in norA measurements. G65A almost abolished binding to all promoters, highlighting its universal importance. The conserved cysteine residues in zinc cluster proteins are known to be critical for zinc coordination and structural integrity14. Mutation of one such residue, C39A, resulted in complete loss of DNA binding activity across all three promoters (Supplementary Fig. 24a). This observation underscores the essential role of the zinc cluster structural fold in establishing the foundation for DNA recognition.

To further assess the functional importance of terminal regions in DNA recognition, we tested additional truncation constructs lacking either the C-terminal region (15–57) or both terminal regions (28–57) for their ability to bind promoter DNA. While the DBD (15–79) formed stable complexes with all three promoters, removal of either the C-terminal region alone or both terminal regions completely abolished DNA binding (Supplementary Fig. 24b). Constructs 15–69 (C-terminal truncation) and 26–79 (N-terminal truncation) had previously demonstrated substantially reduced binding affinities for the ver1 promoter compared to the intact DBD (Fig. 1d, e). These findings provide direct experimental evidence that both terminal regions, particularly the C-terminus, are essential for DNA recognition. These results, combined with NMR titration experiments and the differential contact patterns revealed by MD simulations (Fig. 4a and Supplementary Fig. 23), provide compelling evidence that AflR-DBD employs distributed interactions across its structural elements to achieve sequence-diverse DNA recognition, with terminal regions playing a key role in adapting to sequence variations across different promoters.

DNA binding reshapes AflR-DBD’s dynamic landscape

Having established the validity of the MD ensembles through the overall agreement between simulation results, NMR observations, and mutational effects, we next conducted an in-depth analysis to examine how DNA binding influences AflR-DBD’s conformational dynamics. Jensen-Shannon Divergence (JSD) analysis (see Methods for details) comparing free and DNA-bound states revealed that complex formation primarily affects backbone conformational dynamics rather than side-chain arrangements across all three promoter complexes and at both binding sites (Fig. 5a). Two-dimensional density analysis of JSD backbone distance showed that the N-terminal region (residues 15–25) exhibits relatively consistent patterns of altered interactions across all complexes, while C-terminal region (residues 65–79) changes vary significantly between different promoters and binding sites (Fig. 5b). This observation aligns with our previous findings regarding the role of terminal regions in adapting to different DNA sequences, particularly the C-terminal region’s variable interaction patterns observed in different complexes (Fig. 4a).

a Jensen-Shannon Divergence (JSD) distributions comparing free AflR-DBD to AflR-DBD bound to the first CG site (site A) and second CG site (site B) of ver1, vbs, and norA promoters. JSD values are calculated for backbone distances (JSDBB-dist), backbone torsion angles (JSDBB-tor), and sidechain torsion angles (JSDSC-tor). b Two-dimensional density plots of JSD for backbone distances compares free and DNA-bound states at site A and site B across promoters. Color intensity indicates the degree of conformational change, with reddish colors representing larger differences.

To further investigate the specific conformational motions influenced by DNA binding, we performed principal component analysis (PCA) on the structural ensembles. The PCA model constructed using the ensemble of free AflR-DBD and applied to the DNA-bound systems revealed striking differences between free and DNA-bound states of AflR-DBD. The free protein explored a broader conformational space, consistent with its partially disordered nature, while DNA-bound forms occupied more restricted conformational regions (Fig. 6a). Visualization of conformational motions showed that PC1 represents an opening-closing movement between terminal tails (Fig. 6b). AflR-DBD bound at site A maintains similar motions to the free protein along PC1 but with reduced amplitude (Fig. 6c), while binding at site B induces distinctly different motions, indicating site-specific effects on protein dynamics. PC2 captured movement between the C-terminal tail and zinc cluster motif (Fig. 6b). Interestingly, the behavior along PC2 showed an inverse pattern—binding at site B preserved free protein-like motions while site A binding induced different movements (Fig. 6d). This differential response suggests that each binding site uniquely modulates distinct aspects of AflR-DBD’s conformational flexibility.

a Principal component analysis (PCA) comparing conformational spaces of free and bound states. The PCA model was constructed using the MD trajectory of free AflR-DBD and applied to DNA-bound AflR-DBD states. b Porcupine plots illustrate major conformational motions on the free state along PC1 and PC2. c, d DNA binding-induced changes in conformational dynamics along PC1 and PC2. e Changes in residue centrality upon DNA binding identify key communication hubs. Red dots indicate increased centrality, while blue dots represent decreased centrality.

The integration of JSD and PCA analyses provided complementary insights, collectively emphasizing the crucial role of the C-terminal region in modulating AflR-DBD’s conformational dynamics upon DNA binding. This region’s contributions were particularly evident in the backbone dynamics and differential motions captured along PC1 and PC2. To further clarify the role of the C-terminal region in AflR-DBD dynamics and function, we conducted a correlation network analysis of the structural ensembles. This approach quantified how DNA binding alters coordinated motions within the protein. The analysis demonstrated that DNA binding significantly enhances the centrality of C-terminal residues in AflR-DBD’s structural network (Fig. 6e). In correlation network analysis, high centrality indicates that a node (in this case, a residue or group of residues) plays a key role in information flow through the network. The increased centrality of the C-terminal residues upon DNA binding suggests that this region acts as a hub for information transfer within the protein.

The residue-level differential correlation analyses further revealed that DNA binding strengthens the connections between the C-terminal tail (residues 60–70) and other protein regions, though the magnitude of this effect varies depending on the specific DNA sequence (Supplementary Fig. 25). Furthermore, our experiments revealed that mutations in this region disrupted protein-DNA interactions substantially more than non-cysteine residue mutations in either the zinc cluster motif or N-terminal region (Fig. 4c). Together, these analyses establish that DNA binding reshapes AflR-DBD’s dynamic landscape. While complex formation restricts overall conformational spaces, the protein maintains significant flexibility, particularly in the C-terminal region. The differential effects across promoters suggest that retained dynamics enable adaptation to sequence variations while maintaining specificity through the zinc cluster motif’s anchoring interactions.

Discussion

Through integrated structural, dynamics, and functional analyses, we have uncovered how the AflR DNA-binding domain employs a distinct mechanism combining a structured zinc cluster motif with dynamic terminal regions to achieve sequence-diverse DNA recognition. Our CD, NMR, and MD simulations revealed that AflR-DBD contains a stable zinc cluster motif flanked by dynamic terminal regions (Fig. 1f–k). Two AflR-DBD monomers recognize inverted CG half-sites while maintaining conformational plasticity (Figs. 2, 3 and Supplementary Fig. 11), with binding mediated through distributed interactions spanning from the zinc cluster motif through both terminal regions (Fig. 4 and Supplementary Figs. 22 and 23). The C-terminal region functions as a conformational hub that coordinates structural changes required for stable complex formation (Fig. 6e and Supplementary Fig. 25).

Structural and dynamics analysis of AflR-DBD reveals a marked departure from known zinc cluster protein binding mechanisms. Classical dimeric TFs like Gal4 and Ppr1 recognize DNA through coiled-coil mediated dimerization, while monomeric proteins like AlcR and Pho7 employ stable conformations and interaction interfaces14,17,18. In contrast, AflR achieves promoter binding through two monomers, maintaining conformational flexibility in their bound state. Our MD simulations and NMR analyses demonstrate that although DNA binding constrains overall conformational spaces, the terminal regions retain mobility for adaptation to sequence variations (Figs. 2a, 3 and Supplementary Fig. 11). The distributed interaction network, spanning the zinc cluster motif and terminal regions, establishes binding specificity while enabling recognition of diverse target sequences with significant variation. This diversity appears biologically meaningful when compared to metrics used in previous studies—the Jaccard similarity indices (0.290–0.375) approach thresholds used to classify different binding patterns, while the Pearson correlation values (0.255–0.300) are comparable to thresholds for defining distinct binding clusters (Supplementary Fig. 26)29,30. This binding mechanism likely evolved to enhance flexibility in target recognition while maintaining sequence specificity, enabling AflR to regulate multiple genes in the AF biosynthesis gene cluster through varied binding configurations.

The AflR binding mechanism extends the current understanding of IDR-mediated transcription factor function and suggests broader principles of transcriptional regulation. Recent studies of yeast transcription factors Msn2 and Yap1 have demonstrated how IDRs use multiple weak interaction motifs to determine promoter specificity6,11. The herpes virus transcription factor ICP4 similarly employs disordered regions to modulate DNA recognition12. AflR extends these findings by demonstrating how relatively short, disordered regions can integrate with a structured motif to enable sophisticated DNA recognition—the zinc cluster motif provides sequence-specific anchoring while dynamic termini optimize binding through distributed interactions (Fig. 3a–c). This mechanism implies an evolutionary adaptation, as evidenced by the prevalence of intrinsic disorder in eukaryotic transcription factors (>80%) compared to bacterial counterparts (<5%), suggesting evolutionary selection for structural flexibility in more complex regulatory networks8. Integrating ordered and disordered regions appears advantageous for TFs that coordinate multiple genes through diverse binding sites while maintaining regulatory specificity7,9,31,32.

Based on our findings and the understanding of IDR-mediated transcription factor binding, we propose a “Dynamic-Anchor” model for AflR-DNA recognition (Fig. 7). This model describes a sophisticated three-phase binding strategy that integrates both structured elements and IDRs to achieve optimal DNA binding specificity. In Phase I, flexible terminal regions facilitate initial DNA scanning through transient interactions. This dynamic scanning process, reminiscent of IDR-mediated target searching observed in transcription factors like Msn2, Yap1, and tumor suppressor p53, enables rapid exploration of potential binding sites across broad DNA regions6,31. Phase II centers on the structured zinc cluster motif, establishing sequence-specific major groove contacts with CG half-sites (Fig. 3a–c). This anchoring phase provides the foundation for sequence-specific recognition9. In Phase III, the disordered regions coordinate structural changes that optimize binding through distributed interactions6,7,9,32. This model explains how AflR achieves both sequence specificity and adaptability. The conserved zinc cluster ensures target recognition, while terminal region flexibility enables the accommodation of sequence variations. The proposed “Dynamic-Anchor” mechanism represents a paradigm that addresses the challenge of sequence-diverse DNA recognition and advances understanding of multi-target transcriptional regulation by TFs regulating multiple genes through varied recognition sequences.

Schematic model showing three phases of DNA binding. Phase I (IDR-guided promoter scanning): The highly flexible terminal regions of AflR-DBD engage in transient, non-specific interactions with DNA to facilitate rapid scanning of potential binding sites. Phase II (Zinc cluster motif anchoring): The structured zinc cluster motif recognizes and binds to specific CG half-sites within different promoters through precise major groove contacts, serving as a stable molecular anchor. Phase III (IDR-mediated binding optimization): The dynamic terminal regions mediate the protein undergo conformational changes to establish distributed, weak interactions across the DNA binding interface, optimizing the binding specificity and stability. Orange spheres represent the zinc cluster motif; gray, blue, and red lines indicate terminal IDRs; turquoise dots mark CG binding sites; and the gray double helix represents DNA.

From a therapeutic perspective, understanding this mechanism suggests strategies for targeting transcription factor function in pathogenic fungi. While the zinc cluster motif provides a stable binding site, its conservation across fungal transcription factors presents selectivity challenges for inhibitor development. The more variable terminal regions, particularly the C-terminal domain containing residues R63, R66, and G65 that are essential for DNA recognition (Fig. 4c), offer opportunities for selective inhibition through recently developed approaches targeting disordered regions33,34. These findings establish a structural basis for developing targeted interventions to control aflatoxin biosynthesis while minimizing off-target effects on other zinc cluster proteins.

Beyond the therapeutic implications, our mechanistic insights into AflR contribute to the understanding of transcriptional regulation. By revealing how conformational dynamics enable sequence-diverse DNA recognition through the interplay of structured and disordered protein regions, our findings have implications far beyond fungal systems. The proposed “Dynamic-Anchor” mechanism may represent a broader model in TFs-DNA interactions, suggesting that integrating ordered and disordered elements could be a common strategy for achieving regulatory specificity while maintaining adaptability. Future studies examining the prevalence of such mechanisms across different DNA-binding protein families will further elucidate the role of structural disorder in expanding regulatory capabilities while retaining binding specificity. The combined approach employed here for characterizing partially disordered DNA-binding domains should prove valuable for investigating other flexible transcription factors that have resisted traditional structural analysis.

Methods

Bioinformatics analysis

Initial characterization of the AflR protein was conducted through comprehensive bioinformatics analyses. Secondary structure predictions were performed using PSSpred, which employs a neural network-based algorithm to predict protein secondary structure elements with high accuracy35. Intrinsic disorder predictions were carried out using the PONDR suite36. The presence of potential coiled-coil regions was assessed using the CoCoNat server37. To analyze the conservation of DNA binding sequences, promoter regions of ver1, vbs, and norA genes were examined using Skylign, generating sequence logos highlighting position-specific nucleotide preferences38.

Protein expression and purification

A series of A. flavus AflR fragments (residues 8–98, 15–88, 15–79, 15–69, and 26–79) was systematically designed based on sequence analysis and structural predictions. These fragments were individually cloned into modified versions of the pET32a vector (containing a TRX tag) or pET-M3C vector (containing a His₆ tag) at their N-termini. All mutations were generated using standard PCR-based site-directed mutagenesis protocols and verified through DNA sequencing. The expression constructs were transformed into Escherichia coli BL21(DE3) cells for protein production. Bacterial cultures were grown in Luria-Bertani (LB) medium supplemented with 100 μg/mL ampicillin at 37 °C until the optical density at 600 nm (OD₆₀₀) reached 0.6–0.8. Protein expression was induced by adding 0.3 mM isopropyl β-D-1-thiogalactopyranoside (IPTG) and 100 μM ZnCl₂ to ensure proper zinc finger formation. After induction, cultures were incubated overnight at 16 °C to optimize protein folding and solubility.

For NMR studies, uniformly ¹⁵N/¹³C-labeled proteins were prepared by growing bacteria in an M9 minimal medium supplemented with 100 μM ZnCl₂. The medium contained ¹⁵NH₄Cl as the sole nitrogen source for single-labeled proteins or both ¹⁵NH₄Cl and ¹³C-labeled glucose for double-labeled proteins. Cells were harvested by centrifugation (5000 × g, 15 min, 4 °C) and resuspended in a lysis buffer containing 20 mM Tris-HCl pH 7.9, 100 mM NaCl, 5 mM imidazole, 1 mM phenylmethylsulfonyl fluoride (PMSF), and 10 μM ZnCl₂. The cell suspension was subjected to sonication for efficient lysis, followed by centrifugation (20,000 × g, 30 min, 4 °C) to remove cellular debris. The clarified lysate was treated with deoxyribonuclease for 30 min to eliminate nucleic acid contamination before purification. The supernatant was applied to Ni-NTA agarose resin pre-equilibrated with lysis buffer. The resin was thoroughly washed with high-salt buffer (20 mM Tris-HCl pH 7.9, 1 M NaCl, 20 mM imidazole, 10 μM ZnCl₂) to remove non-specifically bound proteins and DNAs. Target proteins were eluted using a buffer containing 20 mM Tris-HCl pH 7.9, 500 mM NaCl, 500 mM imidazole, and 10 μM ZnCl₂. The eluted proteins were purified by size exclusion chromatography (SEC) using a HiLoad 16/600 Superdex 75 pg column (Cytiva). The column was equilibrated for biochemical experiments with SEC buffer (20 mM Tris-HCl pH 8.0, 100 mM NaCl, 10 μM ZnCl₂, and 1 mM 2-mercaptoethanol). For NMR experiments, a modified PBS buffer (pH 6.8, containing 23 mM Na₂HPO₄, 27 mM NaH₂PO₄, 10 μM ZnCl₂, and 1 mM 2-mercaptoethanol) was used.

DNA synthesis and annealing

All oligonucleotides (ver1: 5′-TCAGATATTTCGGTCTCCGAGGAAAGAT-3′, vbs: 5′-ACCGACTCTCGGACAGCGAGGCAGACCG-3′, norA: 5′-ACCGGGCTTTCGGAAAGCGATCAGCTTGT-3′), including those labeled with Cy3 fluorophore for fluorescence-based assays, were chemically synthesized by Sangon Biotech with high-purity purification. Complementary oligonucleotides were carefully annealed using a standardized protocol to generate double-stranded DNA constructs. The oligonucleotides were diluted to 400 µM in either annealing buffer (10 mM Tris-HCl, pH 8.0, 50 mM NaCl) for biochemical assays or PBS buffer for NMR experiments. Equimolar ratios of complementary strands were combined and subjected to a controlled temperature program: thermal denaturation at 95 °C for 5 minutes, followed by gradual cooling to room temperature (25 °C) to ensure proper duplex formation.

Analytical gel filtration chromatography

Analytical gel filtration experiments were performed using an AKTA FPLC system (GE Healthcare) equipped with a Superdex 75 Increase 10/300 GL column (Cytiva). All chromatographic analyses were conducted at room temperature with a 1.0 mL/min flow rate using SEC buffer. For protein-DNA interaction studies, purified proteins (8 μM) were incubated with promoter DNAs (2 μM) for 20 min at room temperature before injection. Elution profiles were monitored continuously by measuring absorbance at 280 nm, enabling the detection of both protein and nucleic acid components.

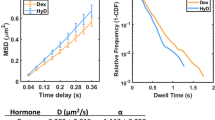

Fluorescence correlation spectroscopy (FCS)

Molecular hydrodynamic measurements were conducted using a bench-top FCS instrument (CorTector SX-B10; LightEdge Technologies Ltd.) equipped with dual continuous-wave lasers (532 nm and 638 nm) and a high-numerical-aperture Olympus 60X NA1.2 water immersion objective26. FCS measurements were performed using optimized conditions: 10 nM Cy3-labelled DNAs were excited using the 532 nm laser, with each measurement lasting 10 s. Auto-correlation curves were analyzed using specialized Correlation Analysis software (LightEdge Technologies Limited) employing the following mathematical model:

N represents the number of fluorescently labeled molecules in the FCS volume, τD is the characteristic diffusion correlation time, S denotes the structure parameter, T represents the fraction of fluorophores residing in the triplet state, and τT is the triplet lifetime. The hydrodynamic radius RH of sample molecules was calculated from the diffusion correlation time \({\tau }_{{{\rm{D}}}}\) using the following relationships:

r0 represents the lateral dimension of the FCS volume; D is the diffusion coefficient, kB is Boltzmann constant, T is absolute experimental temperature, η represents the sample buffer viscosity.

Titration experiments were performed by mixing different concentrations of Trx-tagged AflR-DBD with Cy3-labelled DNAs. To obtain the fractions of unbound and bound DNA after incubation with AflR-DBD, normalized autocorrelation curves were fit to a model of the diffusion of two species in a three-dimensional Gaussian confocal volume. All fitting was performed with a non-linear least-squares algorithm, and dissociation constants (KD) were determined by the Correlation Analysis software.

Circular dichroism (CD) spectroscopy

Far-UV CD spectra were recorded on a Chirascan VX spectropolarimeter (Applied Photophysics Ltd). Protein samples were prepared at 60 μM concentration in PBS buffer and measured in a high-quality quartz cuvette with a 1 mm path length. Spectra were collected from 190 to 240 nm with a scanning speed of 50 nm/min and a bandwidth of 1 nm. Buffer baselines were subtracted, and three accumulations were averaged for each spectrum.

Isothermal titration calorimetry (ITC)

ITC experiments were performed using a MicroCal PEAQ-ITC instrument (Malvern Panalytical) at 16 °C. DNA solutions (0.3 mM) were systematically titrated into protein samples (50–70 μM) prepared in SEC buffer. The titration consisted of an initial 0.5 μL injection followed by multiple 1.5 μL injections, with 150-s intervals between injections. Data analysis was performed using the MicroCal PEAQ-ITC Analysis Software (Malvern Panalytical), and binding parameters including dissociation constants (KD) and binding stoichiometry (N) were determined using a “One Set of Sites” model. Reported KD values represent the Mean ± SD from the two independent measurements.

Electrophoretic mobility shift assay (EMSA)

EMSAs were conducted using 4%–20% gradient polyacrylamide gels (BeyoGel™ Plus PAGE, Beyotimee). DNA fragments (10 µM) were incubated with AflR-DBD (15 or 20 µM) in binding buffer containing 23 mM Na₂HPO₄, 27 mM NaH₂PO₄ (pH 6.8), 1 mM β-mercaptoethanol, 10 µM ZnCl₂, 5% (v/v) glycerol, and 0.01 mg/mL bovine serum albumin (BSA). Following a 20-min incubation on ice, samples were loaded onto pre-cooled gels and electrophoresed at 4 °C using a two-step voltage gradient protocol: 100 V for 20 min followed by 160 V for 50 min. For quantitative EMSA titration experiments, 0.4 μM DNA was incubated with varying concentrations of wild-type or mutant AflR-DBD (0, 0.05, 0.1, 0.2, 0.5, 1, 1.5, 2, 3 μM) in the same binding buffer. After incubation on ice for 20 min, samples were analyzed using the same electrophoresis conditions. Each titration experiment was performed in triplicate.

Post-electrophoresis visualization was achieved by staining gels with 1X TS-GelRed (TSINGKE) for 2 h. Gel images were captured using a Chemi Doc XRS imaging system (Bio-Rad), and quantitative analysis of band intensities was performed using ImageJ software. For titration experiments, the fraction of bound DNA was plotted against protein concentration, and apparent dissociation constants (KD-app) were calculated by fitting the data to an equation derived for a highly cooperative two-to-one equilibrium binding model39. Reported KD-app values represent the Mean ± SD from three independent experiments.

NMR spectroscopy

NMR experiments were conducted using uniformly ¹⁵N-labeled or ¹³C/¹⁵N-double-labeled AflR 15–79 protein samples prepared in PBS buffer containing 10% D₂O. All spectra were acquired at 278 K using a Bruker AVIII 600 spectrometer equipped with a cryoprobe. Backbone and side-chain resonance assignments were achieved by standard heteronuclear correlation experiments, including HNCO, HNcaCO, HNCACB, CACBCONH, HBHAcoNH, HCCH-TOCSY, CCH-TOCSY, using a ∼0.6 mM 15N/13C-labeled protein sample. Approximate inter-proton distance restraints were derived from three-dimensional NOESY experiments, specifically a ¹⁵N-separated NOESY and a ¹³C-separated NOESY. All multidimensional NMR data were processed using NMRPipe40 and analyzed using NMRFAM-SPARKY41. The backbone and side-chain chemical shift assignments and NOE assignments were initially determined using the machine learning-based method ARTINA implemented in the NMRtist web-server, followed by careful manual verification and correction42. Backbone dihedral angle restraints (Φ and Ψ angles) were derived using the TALOS-N program, which employs chemical shift data to predict protein backbone torsion angles43. Secondary structure propensity (SSP) values were calculated using the SSP program, primarily utilizing Cα and Cβ chemical shifts to determine local structural preferences44. For NMR titration experiments investigating protein-DNA interactions, unlabeled DNA was added incrementally to ¹⁵N-labeled AflR samples, and ¹H-¹⁵N HSQC spectra were recorded at the titration point to monitor binding-induced changes in chemical shifts and peak intensities.

¹⁵N relaxation experiments were carried out using ¹⁵N-labeled AflR-DBD samples at a protein concentration of 0.1 mM. T₁ measurements were performed with eight relaxation delays (2, 20, 40, 80, 160, 320, 640, and 1280 ms) using a 2 s recycle delay. T₂ was measured with ten relaxation delays (0, 20, 40, 80, 100, 120, 160, 200, 300, and 400 ms). Steady-state ¹H-¹⁵N heteronuclear NOE experiments were recorded in an interleaved manner, with and without proton saturation26. The spectra measuring ¹H-¹⁵N NOEs were acquired with a 2 s relaxation delay, followed by a 3 s period of proton saturation. In the absence of proton saturation, the spectra were recorded with a relaxation delay of 5 s. T₁/T₂ ratios were calculated from relaxation rates, heteronuclear NOE values were determined as the ratio of peak intensities in spectra recorded with and without proton saturation. Error bars for relaxation parameters were derived from the signal-to-noise ratio of the spectra and fitting errors45.

Native mass spectrometry

The purified AflR-DBD protein was buffer-exchanged into 150 mM ammonium acetate solutions using 3 KDa centrifugal filters (Amicon). The prepared sample was loaded into gold-coated borosilicate glass capillaries (in-house prepared) and ionized via standard static nanoESI ion sources into a Q Exactive UHMR Hybrid Quadrupole Orbitrap mass spectrometer (Thermo Fisher Scientific). The mass spectra were acquired in the positive mode and at a resolution setting of 120,000 and scan range of m/z 300–3500. The instrument was tuned as follows: spray voltage 1.6 kV, capillary temperature 250 °C, desolvation voltage 0 V, source fragmentation 0 V. Data analysis was performed using FreeStyle (v1.6) software (Thermo Fisher Scientific) to determine charge states and calculate the molecular mass of the protein.

Molecular dynamics (MD) simulations

All-atom MD simulations were performed using GROMACS 2020 with the AMBER99SB-ILDN force field for protein and the TIP3P water model46,47,48. For the simulations of free AflR-DBD, initial structural models were generated using CS-Rosetta and AlphaFold2, providing multiple starting conformations for comprehensive sampling49,50. Three independent simulations were initiated using two structures from CS-Rosetta and one from AlphaFold2. The CYS residues within the zinc cluster motif were modeled in their deprotonated state (CYM) to maintain a stable zinc finger domain structure. Systems were neutralized with Na⁺ and Cl⁻ ions to a physiological concentration of 150 mM. Energy minimization was performed using the steepest descent algorithm for 50,000 steps. System equilibration was carried out for 1 ns with constraints on the hydrogen bonds in the isothermal-isochoric (NVT) and isothermal-isobaric (NPT) ensembles, respectively51. Temperature was maintained at 298 K using the v-rescale method, while pressure was kept at 1 bar through semi-isotropic coupling to a Parrinello-Rahman barostat (τp = 1.0 ps, compressibility = 4.5 × 10⁻⁵ bar)52,53. Hydrogen bonds were constrained using the LINCS algorithm with a 2 fs time step54. Both electrostatic and van der Waals interactions employed a cutoff of 1.0 nm, with long-range electrostatics computed using the particle mesh Ewald (PME) method55. The zinc cluster topology was stabilized using previously reported geometric constraints, including Zn-Zn and S-Zn distances of 3.16 Å and 2.34 Å, respectively. Additionally, the S-Zn-S and Zn-S-Zn angles were constrained to 109° and 70°, respectively15. These parameters maintain tetrahedral geometry for zinc coordination. Additional distance and dihedral angle restraints derived from NMR experiments were applied throughout all simulation steps. Three independent trajectories were generated, each running for 18 μs, resulting in a total simulation time of 54 μs. Chemical shift prediction based on MD simulations was performed using the SPARTA+ software56. Secondary chemical shift ∆δ, such as ∆δ of C\(\alpha\) (∆δCα), is defined as ∆δCα = δCαexp/simu − δCαrandom25.

For protein-DNA complex simulations, initial models were constructed through a multi-step process. Standard B-form DNA structures were generated using the W3DNA web server57. Direct docking of AflR-DBD to the DNA CG sites was hindered by steric clashes (Supplementary Fig. 16b). Therefore, 100 ns MD simulations of the DNAs from the ver1, vbs, and norA promoter regions were performed using the updated Parmbsc1 (BCS1) force field for nucleic acids to optimize CG half-site accessibility48,58. Steered MD (SMD) simulations were performed using an AlphaFold model of AflR-DBD to achieve the appropriate conformation for complex formation. The external force was applied to the Cα atoms of the first and last residues of AflR-DBD to pull the protein tails along the z-axis, with the protein positioned along the xy-plane. The force constant was set to 1000 kJ/mol/nm², and the reference position’s velocity was 10 nm/ns. Each SMD simulation lasted 1 ns in the NPT ensemble, with coordinates saved every 10 ps.

The resulting structures of AflR-DBD and DNA were aligned with the crystal structure of the Ppr1-DNA complex (PDB ID: 1PYI) using the align and pair fit modules in PyMOL (http://www.pymol.org/pymol)28. Structures without steric clashes were used as initial models for the AflR-DBD/DNA complexes. Production MD simulations for protein-DNA complexes employed the same parameters as free protein simulations but excluded NMR-derived restraints while maintaining zinc cluster geometry constraints. Three independent 4 μs trajectories were generated for each promoter complex (ver1, vbs, and norA), totaling 12 μs per complex. For analysis, all production trajectories from the three independent simulations were used for each system. The setup of simulation systems is described in Table 1.

Analysis of MD ensembles

The root-mean-square deviation (RMSD), Root-mean-square fluctuation (RMSF), and cluster analyses were carried out using tools implemented in GROMACS. A hierarchical approach was applied to identify representative conformations for the cluster analysis. The backbone RMSD was employed as the similarity metric, exploring cut-off values ranging from 0.2 to 1.0 Å to determine the optimal clustering resolution. Plotting the number of clusters against the RMSD cut-off showed a significant reduction in cluster numbers as the cut-off increased from 0.3 to 0.6 nm for free AflR-DBD and from 0.2 to 0.4 nm for complex systems. Beyond these ranges, the decrease in cluster numbers became more gradual. This analysis allowed for selecting the RMSD cut-off that achieved a balance between maintaining a manageable number of clusters and preserving meaningful structural variation. A final cut-off of 0.7 nm was chosen for free AflR-DBD, while 0.5 nm was selected for the complex systems.

Protein-DNA interactions were examined using Contact Map Explorer (v0.7.0), which builds on tools provided by MDTraj (v1.9.6)59. The interaction fingerprinting analysis was performed using ProLif (v2.0.3)60. To further characterize the differences in the conformational dynamics of AflR-DBD, distributions of intra-backbone distances (BB-dist) and backbone and side-chain torsions (BB-tor, SC-tor) were analyzed across the systems. The Jensen-Shannon Divergence (JSD) was used to quantify the similarity of these ensembles between the different systems, with values ranging from 0 (identical distributions) to 1 (completely different distributions). JSD values were calculated for free and DNA-bound states using the Python-based PENSA library (v0.3.0)61. Principal Component Analysis (PCA) was conducted using the MDAnalysis package (v2.7.0), where the trajectories were aligned, and PCA was performed on the backbone atoms62. The first two principal components were visualized for further analysis. Additionally, a correlation network analysis was carried out with the MDiGest package (v0.1.8)63. Based on mutual information, generalized correlation coefficients (gcc-mi) were calculated from the Cα displacements sampled from the MD trajectories for both the free and DNA-bound systems. Changes in eigenvector centrality, which measure the importance of residues in the network, were used to identify residues with significant changes in centrality, reflecting their altered role in the system’s conformational dynamics.

Sequence diversity analysis

To quantify the diversity among AflR binding sites, we performed comparative sequence analysis of the ver1, vbs, and norA promoter regions. For Jaccard similarity calculation, we first decomposed each DNA sequence into trinucleotide k-mers using a sliding window approach. The Jaccard similarity index was then calculated as the ratio of the number of shared k-mers between two sequences to the total number of unique k-mers in both sequences29. This resulted in a similarity score ranging from 0 (completely dissimilar) to 1 (identical). For the Pearson correlation analysis, we generated k-mer frequency profiles for each sequence and calculated the Pearson correlation coefficient between these profiles30. This approach captures the similarity in the distribution patterns of sequence motifs.

Reporting summary

Further information on research design is available in the Nature Portfolio Reporting Summary linked to this article.

Data availability

The 1H, 13C, and 15N chemical shifts for AflR-DBD generated in this study have been deposited in the Biological Magnetic Resonance Data Bank under accession code 52862. MD simulation files, including the initial coordinate, simulation input files and a coordinate file of the final output, have been deposited on Zenodo at https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.15969641. Native mass spectrometry raw data has been deposited to the ProteomeXchange Consortium [https://proteomecentral.proteomexchange.org] via the iProX partner repository [https://www.iprox.cn/] with the dataset identifier PXD067110. This study made use of the following previously published structure deposited in the Protein Data Bank: 1PYI. Additional data supporting the findings of this study are included within the paper and its Supplementary Information files. Source data are provided with this paper.

References

Todeschini, A.-L., Georges, A. & Veitia, R. A. Transcription factors: specific DNA binding and specific gene regulation. Trends Genet. 30, 211–219 (2014).

Weirauch, M. T. et al. Determination and inference of eukaryotic transcription factor sequence specificity. Cell 158, 1431–1443 (2014).

Badis, G. et al. Diversity and complexity in DNA recognition by transcription factors. Science 324, 1720–1723 (2009).

Lambert, S. A. et al. The human transcription factors. Cell 172, 650–665 (2018).

Morgunova, E. et al. Two distinct DNA sequences recognized by transcription factors represent enthalpy and entropy optima. Elife 7, e32963 (2018).

Brodsky, S. et al. Intrinsically disordered regions direct transcription factor in vivo binding specificity. Mol. Cell 79, 459–471 (2020).

Brodsky, S., Jana, T. & Barkai, N. Order through disorder: the role of intrinsically disordered regions in transcription factor binding specificity. Curr. Opin. Struct. Biol. 71, 110–115 (2021).

Liu, J. et al. Intrinsic disorder in transcription factors. Biochemistry 45, 6873–6888 (2006).

Ferrie, J. J., Karr, J. P., Tjian, R. & Darzacq, X. Structure”-function relationships in eukaryotic transcription factors: the role of intrinsically disordered regions in gene regulation. Mol. Cell 82, 3970–3984 (2022).

Már, M., Nitsenko, K. & Heidarsson, P. O. Multifunctional intrinsically disordered regions in transcription factors. Chemistry 29, e202203369 (2023).

Mindel, V. et al. Intrinsically disordered regions of the Msn2 transcription factor encode multiple functions using interwoven sequence grammars. Nucleic Acids Res. 52, 2260–2272 (2024).

Tunnicliffe, R. B. et al. The herpes viral transcription factor ICP4 forms a novel DNA recognition complex. Nucleic Acids Res. 45, 8064–8078 (2017).

Van Der Lee, R. et al. Classification of intrinsically disordered regions and proteins. Chem. Rev. 114, 6589–6631 (2014).

MacPherson, S., Larochelle, M. & Turcotte, B. A fungal family of transcriptional regulators: the zinc cluster proteins. Microbiol. Mol. Biol. Rev. 70, 583–604 (2006).

Cerdan, R., Cahuzac, B., Félenbok, B. & Guittet, E. NMR solution structure of AlcR (1–60) provides insight in the unusual DNA binding properties of this zinc binuclear cluster protein. J. Mol. Biol. 295, 729–736 (2000).

Cahuzac, B., Cerdan, R., Felenbok, B. & Guittet, E. The solution structure of an AlcR-DNA complex sheds light onto the unique tight and monomeric DNA binding of a Zn2Cys6 protein. Structure 9, 827–836 (2001).

Garg, A., Goldgur, Y., Schwer, B. & Shuman, S. Distinctive structural basis for DNA recognition by the fission yeast Zn2Cys6 transcription factor Pho7 and its role in phosphate homeostasis. Nucleic Acids Res. 46, 11262–11273 (2018).

Garg, A., Goldgur, Y., Sanchez, A. M., Schwer, B. & Shuman, S. Structure of fission yeast transcription factor Pho7 bound to promoter DNA and effect of Pho7 mutations on DNA binding and homeostasis. Mol. Cell Biol. 39, e00132–00119 (2019).

Caceres, I. et al. Aflatoxin biosynthesis and genetic regulation: a review. Toxins 12, 150 (2020).

Kong, Q. et al. Identification of AflR binding sites in the genome of Aspergillus flavus by ChIP-Seq. J. Fungi 6, 52 (2020).

Fernandes, M., Keller, N. P. & Adams, T. H. Sequence-specific binding by Aspergillus nidulans AflR, a C6 zinc cluster protein regulating mycotoxin biosynthesis. Mol. Microbiol. 28, 1355–1365 (1998).

Ehrlich, K. C., Montalbano, B. G. & Cary, J. W. Binding of the C6-zinc cluster protein, AFLR, to the promoters of aflatoxin pathway biosynthesis genes in Aspergillus parasiticus. Gene 230, 249–257 (1999).

Wang, P., Xu, J., Chang, P. K., Liu, Z. & Kong, Q. New insights of transcriptional regulator AflR in Aspergillus flavus physiology. Microbiol. Spectr. 10, e0079121 (2022).

Woloshuk, C. et al. Molecular characterization of aflR, a regulatory locus for aflatoxin biosynthesis. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 60, 2408–2414 (1994).

Wu, S. et al. The dynamic multisite interactions between two intrinsically disordered proteins. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. Engl. 56, 7515–7519 (2017).

Wang, D. et al. The importance of the compact disordered state in the fuzzy interactions between intrinsically disordered proteins. Chem. Sci. 13, 2363–2377 (2022).

Carey, M., Kakidani, H., Leatherwood, J., Mostashari, F. & Ptashne, M. An amino-terminal fragment of GAL4 binds DNA as a dimer. J. Mol. Biol. 209, 423–432 (1989).

Marmorstein, R. & Harrison, S. C. Crystal structure of a PPR1-DNA complex: DNA recognition by proteins containing a Zn2Cys6 binuclear cluster. Genes Dev. 8, 2504–2512 (1994).

Schmitges, F. W. et al. Multiparameter functional diversity of human C2H2 zinc finger proteins. Genome Res. 26, 1742–1752 (2016).

Najafabadi, H. S. et al. C2H2 zinc finger proteins greatly expand the human regulatory lexicon. Nat. Biotechnol. 33, 555–562 (2015).

Staby, L. et al. Eukaryotic transcription factors: paradigms of protein intrinsic disorder. Biochem. J. 474, 2509–2532 (2017).

Hadži, S. et al. Fuzzy recognition by the prokaryotic transcription factor HigA2 from Vibrio cholerae. Nat. Commun. 15, 3105 (2024).

Henley, M. J. & Koehler, A. N. Advances in targeting ‘undruggable’ transcription factors with small molecules. Nat. Rev. Drug Discov. 20, 669–688 (2021).