Abstract

Cell growth and division must be coordinated to maintain a stable cell size, but how this coordination is implemented in multicellular tissues remains unclear. In unicellular eukaryotes, autonomous cell size control mechanisms couple cell growth and division with little extracellular input. However, in multicellular tissues we do not know if autonomous cell size control mechanisms operate the same way or whether cell growth and cell cycle progression are separately controlled by cell-extrinsic signals. Here, we address this question by tracking single epidermal stem cells growing in the mouse ear. We find that a cell-autonomous size control mechanism, dependent on the RB pathway, sets the timing of S phase entry based on the cell’s current size. Cell-extrinsic variations in the cellular microenvironment affect cell growth rates but not this autonomous coupling. Our work reassesses long-standing models of cell cycle regulation in complex animal tissues and identifies cell-autonomous size control as a critical mechanism regulating cell division.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Cell size sets the fundamental spatial scale of all cellular processes. It delimits a cell’s biosynthetic capacity, affects the rates of cell migration and death, and influences cell fate decisions1,2,3,4,5. Although a cell’s size is generally proportional to the amounts of its biosynthetic machineries and the volumes of its organelles, many proteins scale differently with cell size, leading to small and large cells becoming biochemically different6,7,8. Therefore, each cell type likely controls its size to be within a specific range that optimizes the proteome composition for its physiological role. When cycling cells exceed their target size range, their cellular proteomes begin to resemble those of senescent cells, and they tend to permanently exit the cell division cycle6,9,10,11.

Change in cell size, especially stem cell size, has been associated with cancer and other aging-related diseases1,10,12. However, we do not understand the mechanisms that maintain stable cell sizes in animals. In unicellular free-living eukaryotes, cell growth is largely limited by nutrient availability, while dedicated cell-autonomous mechanisms sense cell size and transmit this signal to control division13,14,15. For multicellular organisms, in order to maintain tissue architecture and sustain the proper distribution of cell types, both cell growth and division processes are thought to be controlled extrinsically by extracellular signals14,16. However, it is unclear how these signals are linked within a single cell to coordinate its growth and division to maintain a constant cell size. In adult stem cells that continually grow and divide to replenish a tissue, cell size affects critical stem cell functions like niche interaction, fate-specification, and tissue regeneration capacity10,17,18,19. Therefore, it is important to understand whether cell-autonomous size control mechanisms, similar to those operating in unicellular species, couple cell growth and cycle progression to produce the remarkable uniformity of stem cell sizes we see in vivo (Fig. 1A; Supplementary Fig. S1)20.

A Schematic of the current model of multicellular cell size control. Whether cell size control is cell-autonomous and how it integrates with cell state changes and non-cell autonomous factors is not well understood. B Zebrafish mesenchymal osteoblasts were imaged in vivo every 20 min from 24 h to 48 h post-scale injury. C An example of a single zebrafish scale osteoblast expressing osx:mCherry-zCdt1 (FUCCI-G1) and osx::Venus-hGeminin (FUCCI-S/G2/M) tracked from birth to the G1/S transition. Solid yellow outlines are the 3D nuclear segmentation. Dotted yellow outlines are the tracked cell position. D Birth size is inversely proportional to the amount of cell growth in the G1 phase in zebrafish osteoblasts. Slope = −0.76 (p < 0.01, two sided T test). n = 36 cells. Source data are provided as a Source Data file.

Previous work identified a class of cell-autonomous size control mechanisms in which the concentration of a cell cycle inhibitor becomes diluted by cell growth to trigger cell cycle progression in larger cells21,22,23,24. These diluted inhibitors include the retinoblastoma protein RB1 in human cells, which binds and inhibits the E2F cell cycle transcription factors to inhibit S phase entry22,25. Although inhibitor-dilution was identified as a cell size control mechanism in some cultured human cells, its functional relevance—and the general importance of size regulation at the G1/S transition—has recently been called into question. This is because a large panel of cell lines cultured in vitro do not strongly control their size at the G1/S transition26,27,28,29. Moreover, cells in vitro are 3–4 fold larger than their in vivo counterparts and cycle much faster30,31. The lack of physiological and phenomenological similarity between metazoan cells in vitro and in vivo has precluded our ability to use in vitro models to dissect what mechanisms coordinate cell growth and cell cycle progression in vivo.

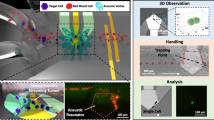

To test if cell-autonomous size control mechanisms operate in vivo, we use intravital time lapse imaging to examine the adult mouse epidermis, a highly proliferative tissue where both cell and tissue size are maintained. We focus on adult stem cells because the cell-extrinsic signals in homeostatic tissues are likely less complex than those in dynamically growing embryonic tissues. Furthermore, methods now exist to directly image stem cells in the mouse epidermis in vivo. We previously showed that for epidermal stem cells, unlike in vitro cultures, the rate at which cells pass through the G1/S transition is very sensitive to cell size32. Here, we further analyzed multiple cell types in mice and zebrafish and found that this tight coupling of cell size to the G1/S transition is likely very general. We show that cell size control is an autonomous process in epidermal stem cells. By tracking the growth and division of single epidermal stem cells alongside changes in the cellular microenvironment, we found that cell size is by far the major determinant of the G1/S transition. Cell-extrinsic factors influence single cell growth rates, but play a lesser role in directly determining G1/S timing. In addition, our analysis of mouse ear skin shows that the RB pathway is crucial for cell-autonomous size control in vivo. Cell-autonomous size control accounts for most of the heterogeneity in stem cell cycle timing. Taken together, our work builds a model where cell growth rate is influenced by non-cell autonomous factors, while a cell-autonomous mechanism, dependent on the RB pathway, sets the timing of S phase entry based on current cell size.

Results

Cell size control occurs at the G1/S transition in multiple vertebrate cell types

We previously found that mouse epidermal stem cells exhibited a much tighter coupling between cell size and the G1/S transition than had previously been observed in cell culture32. However, our analysis was restricted to a single murine epithelial cell type, and the generality of this finding was unclear. To test for size control in another vertebrate cell type, we analyzed previously published in vivo time lapse imaging data of zebrafish scale osteoblasts, a mesenchymal cell type that grows and divides during scale regeneration (Fig. 1B; Supplementary Fig. 2A, B)33,34. We tracked osteoblasts from their birth to the G1/S transition, using osteoblast-specific zCdt1-mCherry and hGeminin-Venus nuclear reporters to measure nuclear volume and cell cycle position (Fig. 1C; Supplementary Fig. 2C, D). This revealed a tight coupling between cell size and the G1/S transition, similar to in vivo mouse epidermal stem cells (Fig. 1D)32. The coefficient of variation (CV) of cell size is also minimized at the G1/S transition, compared to at birth or division (Supplementary Fig. S2F). Since similar cell size control is observed in mouse epithelial and zebrafish mesenchymal cells, tight coupling of cell size to the G1/S transition is likely to be a general feature of vertebrate cells in vivo.

To test how cell differentiation affects cell size control, we examined the mammalian intestinal epithelium, which produces multiple cycling cell types from a single lineage. We analyzed intestinal organoids, which closely resemble their in vivo counterparts in terms of their size, architecture, and transcriptional state35. As organoids grow, they transition from an early spheroid stage to a mature stage when intestinal crypts are stably formed (Fig. 2A)36,37. In the spheroid stage, all cells are proliferative, whereas in the mature organoid, only the Lgr5+ intestinal stem cells and the Lgr5- transit-amplifying (TA) cells are actively cycling within the crypt region (Supplementary Fig. 3A). We used light-sheet microscopy to image the growth of spheroid stage organoids expressing the nuclear marker H2B-miRFP670 and the cell cycle markers FUCCI-Cdt1-mCherry and FUCCI-Geminin-GFP (Fig. 2B; Supplementary Fig. S4A; Supplementary Movie S1)38,39. We also imaged mature organoids expressing the stem cell marker Lgr5-GFP and the G1 phase marker FUCCI-Cdt1-mKO2 (Fig. 2C; Supplementary Fig. S5A; Supplementary Movie S2)40,41. We then tracked the growth of spheroid stage cells (Fig. 2D; Supplementary Fig. S4B–D) as well as stem and TA cells within mature organoid crypts (Fig. 2E, Supplementary Fig. S5B, C). Spheroid, stem, and TA cells would wait longer to grow more in the G1 phase if they were born smaller (Fig. 2F, G). Moreover, in all three cell types, the relationship between birth size and the amount of G1 growth lies on nearly the same negative line, suggesting that a similar cell size triggers the G1/S transition in these cell types (Fig. 2G). Indeed, we found that despite differences in average growth rates (Supplementary Fig S3D) and average birth size across spheroid, stem, and TA cells (Fig. 2H), all three cell types enter S phase at the same average size (Fig. 2I). Taken together, we show that the cell size range required for the G1/S transition remains the same even when cells change state or start to differentiate. Therefore, it is likely that the molecular mechanism that encodes this size-dependence is not remodeled by cell differentiation in the intestinal epithelium.

A Schematic of mouse intestinal organoid development. During the spheroid stage, all cells actively cycle. As the organoid matures, crypt domains are established and maintained, and active cycling is restricted to Lgr5+ stem cells and Lgr5- TA cells. B A z-slice of a spheroid stage intestinal organoid expressing H2B-miRFP670, Cdt1-mCherry (FUCCI-G1), and Geminin-mVenus (FUCCI-S/G2/M) is shown. C A z-slice of a mature intestinal organoid crypt expressing Lgr5-GFP and Cdt1-mKO2 (FUCCI-G1) is shown. The autofluorescent lumen is outlined in yellow. D An example of a single spheroid stage cell tracked from birth to the G1/S transition. Solid yellow outlines are the 3D nuclear segmentation. Dotted yellow outlines are the mother cell’s position. E An example of a single Lgr5+ intestinal stem cell tracked from birth to the G1/S transition. Solid yellow outlines are the 3D nuclear segmentation. Dotted yellow outlines are the mother cell’s position and the cell’s position post G1/S transition. Black asterisk denotes a non-cycling Paneth cell. F The nuclear volume at birth of cycling organoid cells is inversely correlated with G1 duration for all cell types. Pearson’s R = −0.22 (p = 0.16) for spheroid stage cells, R = −0.42 (p = 2e–3) for stem cells, and −0.30 (p = 1e–5) for TA cells. Blue: spheroid; green: stem; magenta: TA. G The nuclear volume at birth of cycling organoid cells is inversely correlated with the amount of nuclear growth during G1 phase. Slope = −0.47 (p = 0.001) for spheroid stage cells, −0.75 (p = 0.002) for stem cells, and −0.85 (p = 1.2e-5) for TA cells. Nuclear size at birth (H) and at G1 exit (I) is quantified for spheroid stage cells, mature stem cells, and mature TA cells. Median is shown in white. Quartiles are shown as the gray box. The non-outlier data range is shown as whiskers. Linear regression is solid line. 95% confidence intervals is shaded area. P values are two-sided T test. Source data are provided as a Source Data file.

Epithelial stem cell size is controlled by the RB pathway

Since our analysis shows that the G1/S transition may be important for controlling cell size in multiple cell types and organisms, we next sought to examine if this size control is mediated by the RB pathway in vivo, similar to previous results in cultured human cells (Fig. 3A)22. To test size control models in vivo, we tracked the growth and division of stem cells in the mouse interfollicular epidermis, a multilayered epithelium with stem cells residing at the basal-most layer42,43. Epidermal cells are close enough to the surface that two-photon imaging can be used to directly visualize growing and dividing cells, and the same cells can be imaged over multiple days in intact animals (Fig. 3B)44,45. We used a K14-H2B-Cerulean marker to measure nuclear size, and inferred cell cycle phase using the FUCCI-Cdt1-mCherry (FUCCI-G1) cell cycle reporter (Fig. 3C)39,44. An image analysis pipeline was then developed to segment 3D nuclear morphology and track individual cells from their birth to division (Fig. 3C; Supplementary Fig. S6). We had shown previously that the G1/S transition is coupled to cell volume in the mouse hindpaw using data previously acquired by the Greco group32,44. We repeated this analysis with our new methods, and showed that a cell’s nuclear volume at birth is also inversely proportional to the amount of nuclear growth the cell does during the G1 phase, comparable to our previous analysis of cell volume (slope = −0.63; Fig. 3D)32. This contrasts with the much less stringent cell size regulation reported for individual cells grown in culture (e.g., slope = −0.24 for HT29)28. We note that the long temporal resolution (12 h time points) needed to measure the slow G1 phase is not sufficient for a detailed resolution of the faster S/G2/M phases of the cell cycle. Therefore, more work is needed to fully assess the influence of cell size on the S/G2/M cell cycle phases.

A Schematic of the RB pathway. The S phase-inhibiting activities of Rb1 and Rbl1 are repressed by dilution as cells grow larger in G1. B Intravital imaging of cells within the mouse hindpaw or ear epidermis. En face and side views are shown of hindpaw epidermis expressing the K14-H2B-Cerulean nuclear marker and the FUCCI-G1-mCherry cell cycle phase reporter. Dotted yellow line indicates the location of the basal layer. C A single stem cell in the hinpaw tracked from birth to division. D Epidermal stem cell birth nuclear size is inversely proportional to the amount of nuclear growth during G1 phase. Binned medians ± SEM are shown in red. Slope = −0.63 (p < 0.0001). N = 2 mice, 254 cells. E 4OHT or vehicle was applied topically to the left and right ears of a mouse homozygous for Rbl1–/– and tamoxifen-inducible Rbl1-floxP. F The relationship between nuclear size at birth and the duration of G1 phase is shown for SKO (cyan) and DKO (red) cells. Linear regression is solid line. 95% confidence intervals are shaded. Errorbars are medians ± SEM. SKO: Pearson’s R = −0.46 (p < 0.001), 57 cells; DKO: R = −0.01 (p > 0.9), 49 cells. G The coefficient of variation (CV) of nuclear size is shown for cells prior to the indicated treatment and 5 days after ethanol or 4OHT treatment. H The number of visible dying nuclear bodies are shown for SKO and DKO tissues relative to the timing of drug treatment. Solid line denotes the mean. Shaded region denotes the 95% confidence interval. N = 3 regions. I The number of 53BP1 foci per nuclei is quantified for SKO and DKO tissues. SKO: N = 112 cells, DKO: N = 115 cells (J). Rbl1 protein concentration was quantified in NIH3T3 cells under control or Rb1-knockdown conditions by subtracting the median Rbl1 intensity in Rbl1-knockdown cells with similar nuclear size. P values are two-sided T test test. Source data are provided as a Source Data file.

After establishing an imaging and analysis pipeline for measuring mouse epidermal stem cell growth, we then sought to test the effect of Rb1 deletion on cell size control (Supplementary Fig. S7A). Surprisingly, when we deleted Rb1 by itself, we found minimal effects on cell size control (Supplementary Fig. S7B–G). However, its paralog Rbl1 (p107) can functionally compensate for Rb1-loss in both mouse embryonic fibroblasts (MEFs) and the mouse skin46,47. When Rb1 was deleted in a Rbl1-/- animal (DKO), the G1 duration no longer depended on cell birth size (Fig. 3E, F; Supplementary Fig. S8A, B)48. In ear tissues where only Rbl1 was mutated (SKO), basal layer stem cells that are born smaller had longer G1 durations compared to larger-born cells (Fig. 3F; Supplementary Fig. S8C-F; Supplementary Movie S3, S5), similar to wild-type paw cells (Supplementary Fig. S7F). However, in DKO tissues, cells have G1 phases of similar durations regardless of birth size, indicating a loss of cell size control at the G1/S transition (Fig. 3F; Supplementary Fig. S8G-J; Supplementary Movie S4, S6). Consistent with the RB pathway maintaining cell size homeostasis, the variation in cell size increased in DKO compared to SKO tissues (Fig. 3G). In DKO tissues, mitotic cells were visible in the supra-basal layer, and the ear epidermis grew considerably thicker, although the K10 differentiation marker was not significantly different compared to SKO tissues (Supplementary Fig. S9A–C). By day 4.5 post-4OHT treatment, when most DKO cells have finished their first division and initiated their second cell cycle (Supplementary Fig. S9D), cells started to die throughout the tissue in numbers significantly above those found in SKO tissues (Fig. 3H; Supplementary Fig. S9E). When we harvested skin tissues to stain for DNA damage markers, we found that DKO cells had significantly more 53BP1 foci compared to SKO cells, although it remains unclear whether this is caused by the uncoupling of S phase entry from cell size, or other functions of the RB pathway (Fig. 3I; Supplementary Fig. S9F).

While these data show that the RB pathway is required for cell size control, they do not show that Rb1 and Rbl1 protein concentrations reflect cell size and thereby act as cell size sensors. The fact that Rb1 single deletion phenocopies wildtype cell size control suggests an alternative model in which removing Rb1 and Rbl1 simply abrogates G1/S control altogether and that Rb1 and Rbl1 are not cell size sensors. To distinguish between these models, we sought to measure the cell size-dependence of Rb1 and Rbl1 protein concentrations in murine cells. We analyzed MEFs and NIH3T3s and found that both Rb1 and Rbl1 decrease in concentration as cells grow larger, which supports their role as cell size sensors (Fig. 3J; Supplementary Fig. S11). Moreover, knockdown of Rb1 in NIH3T3s leads to the upregulation of Rbl1 protein, whose concentration remains cell size-dependent (Fig. 3J; Supplementary Fig. S12A–G). This supports the interpretation that in the absence of Rb1, the increased level of Rbl1 can support cell size control, while in wildtype murine cells, both Rb1 and Rbl1 serve as cell size sensors. While our genetic analysis shows that both Rb1 and Rbl1 function are required for effective coupling between cell size and G1/S progression, future work is needed to demonstrate that the in vivo G1/S transition is quantitatively sensitive to the concentration of these Rb-family members and that their concentration decreases with increasing cell size in vivo.

Cell size is the dominant feature determining passage through the G1/S transition

Having established that tight coupling between the G1/S transition and cell size depends on the RB pathway, we sought to determine whether the G1/S transition is also regulated by the cellular microenvironment. For example, in the skin, it is thought that the local loss of cells in the basal layer upregulates the division of neighboring cells44,49. However, it is unclear whether microenvironment variations simply modulate stem cell growth rates so they can reach the cell size required for the G1/S transition faster, or whether variation in tissue signals or microenvironment state can directly exert influence on the timing of the G1/S transition itself (Fig. 4A).

A Tissue signals or microenvironment changes could influence cell cycle progression primarily by changing the cell growth rate, making cells reach the size needed for G1/S progression faster, or by directly influencing cell cycle progression without influencing any cell size requirement. B Example montage of the 3D quantification of cell-intrinsic geometry and cell-extrinsic microenvironment. Top row shows a single basal layer stem cell from birth to division. The middle row shows the cell’s microenvironment. The bottom row shows the cell and microenvironment merged. C Predictive modeling of cell cycle variation in the basal layer tissue. Left shows a table of all the morphometric features derived from cell-intrinsic geometries (15 features) and cell-extrinsic (23 features) geometries. These features used to train a multiple-logistic regression model to predict whether a cell will be in G1 or S/G2 phases of the cell cycle and the relative contribution of each feature analyzed. D Error matrix of the model showing the observed and predicted cell cycle phase classifications. Average of 1000 models. N = 2 regions, 140 S phase cells, and 200 G1 phase cells subsampled randomly from 567 total G1 data points. E The regression coefficient of each feature is shown against its pvalue, as determined by F-test for nested models where the feature was omitted from the model. Only features above significance values of α = 0.01 (dotted line) are labeled. Mean ± std of 1000 iterations. F The mean AUC is shown for 10% cross-validation models with the full feature-set, completely random features, or models with only a single indicated feature. The cell volume-only model performs nearly as well as the full model. Dotted red line marks the performance of the full model. Mean ± SEM of 1000 iterations. G. A linear model combining birth size and pre-G1/S cell growth rate can accurately predict total cell cycle duration. Normalized R2 = 0.64. Source data are provided as a Source Data file.

To disentangle the effects of cell size and microenvironment features on the G1/S transition, we expanded our analysis of wild-type hind-paw epidermal basal layer cells growing during normal homeostasis32,44. We extended our image analysis pipeline to exhaustively annotate all basal layer stem cells within the visible tissue, so that we can conduct a morphometric analysis of all cells and cell-cell contacts with high fidelity (Supplementary Fig. S13; Supplementary Movie S7). Our methods enabled the simultaneous quantification of cell-intrinsic shape alongside quantification of the shape of that cell’s microenvironment, consisting of its immediate neighboring cells (Fig. 4B). We measured many features of cell-intrinsic shape as well as geometries pertaining to the microenvironment, including neighborhood density, average neighbor size, and tissue curvature (Fig. 4C; Supplementary Fig. S14, S15; “Methods”). We used these features to build multiple-logistic regression models that can accurately predict whether a cell is in G1 or S/G2 phases of the cell cycle (Fig. 4D; Supplementary Fig. S16A, B). Surprisingly, when we analyzed the relative contribution of each feature to the model’s accuracy, we found that cell volume was the sole significant factor (Fig. 4E). Consistent with this, we found that the model suffered in its performance only when we randomly permuted cell volume, compared to any other single feature (Supplementary Fig. S16C). Meanwhile, models trained on cell volume alone perform nearly as well as models trained on the whole feature-set (Fig. 4F). Similar results were obtained when we trained the model with PCA-diagonalized feature-sets or used random forest classifiers (Supplementary Fig. S17). Consistent with the classification model, a linear model that combines cell birth size and pre-G1 growth rate accurately predicts the total stem cell cycle duration, since G1 phase accounts for 96% of total cell cycle variance (Fig. 4G; normalized R2 = 0.64). Thus, cell size is the dominant determinant of cell cycle duration for epidermal stem cells.

In contrast to these results showing the importance of cell size for epidermal stem cells in vivo, logistic regression analysis on a previously published human mammary epithelium cell (HMEC) dataset revealed that cell size is not an accurate predictor of the G1/S transition in vitro (Supplementary Fig. S18)50. Moreover, analysis of cell and microenvironment features in mouse intestinal organoids yielded regression models in which both nuclear size and neighbor cell cycle state were significant predictors of the G1/S transition (Supplementary Fig. S19). This shows that while cell size is coupled to the G1/S transition in developing organoids, there is more cell cycle synchrony amongst neighbors (Supplementary Movie S1). Taken together, these data are consistent with the notion that cultured cells do not accurately recapitulate in vivo cell size control physiology, but 3D organoid cultures are better models31.

The cellular microenvironment regulates growth, but not cell-autonomous size control

So far, our work supports a model in which variations in cellular microenvironment and tissue-level signals are upstream of a cell-autonomous size control mechanism. To directly test this model, we perturbed the microenvironment of epidermal stem cells and asked whether the size at which these cells entered S phase remained the same. We used a two-photon laser to selectively deliver a high dose of light to a single cell and quantified the volumetric growth rates and G1 exit sizes of cells that were either within 20 µm of the ablation site (neighboring) or further away (non-neighboring) (Fig. 5A; Supplementary Fig. S20A–C). Within 8–16 h, the ablated cell disappeared from the tissue while the neighboring cells remained intact and growing (Fig. 5B). When we examined the exponential growth rates derived from the growth of either neighboring or non-neighboring cells, we saw that cells proximal to the ablation site grew significantly faster for 3 out the 4 animals we analyzed (Fig. 5C; Supplementary Fig. S20D–H). However, for all animals, the size at which cells entered S phase remained indistinguishable between neighboring and non-neighboring cells (Fig. 5D). Therefore, the coupling of cell size to G1/S transition rates remains similar despite ablation-neighboring cells experiencing faster growth rates. These data collectively support the model in which variation in tissue signals or microenvironment states mainly modulate stem cell growth rates, but the G1/S transition is predominantly determined by the cell’s current size (Fig. 5E).

A Schematic of cell ablation experiments to perturb the skin stem cell microenvironment. A high dose of light is delivered to a single cell nucleus, leading to cell death. The nearby neighboring cells experience faster cell growth rates compared to non-neighboring cells, which are further away from the ablation site. B Example montage of a cell ablation time-series, showing a central ablated cell (green) and a single neighbor cell (red) tracked through time. Only a single tracked neighbor cell is highlighted for clarity. Scale bar is 10 µm. C Exponential growth rate fitted from the nuclear growth rate of ablation-neighboring and non-neighboring cells are shown for 4 mice. D The nuclear size at which cells exit G1 phase is shown for ablation-neighboring and non-neighboring cells. E In adult tissues, variations in tissue and microenvironment state influence the rates of stem cell growth but do not directly influence G1/S transition rates. Instead, a cell size control mechanism, dependent on the RB pathway, autonomously couples the cell’s current size to the G1/S transition, which happens within a specific cell size range. For boxplots, the midline shows the median, the box delimits the quartiles, and the whisker shows non-outlier data range. Pvalues are two-sided T test. Source data are provided as a Source Data file.

Discussion

The complexity of cell-extrinsic control in multicellular tissues has raised the question of whether any cell-autonomous size control mechanisms identified from unicellular eukaryotes and in vitro cell lines can couple cell size to G1/S transition rates in vivo. Here, we show that such cell-autonomous mechanisms are of primary importance for cell size and cell cycle regulation in multiple cell types in mouse and fish. Thus, size control implemented at the G1/S transition is likely a general feature of many vertebrate cells.

Through our exhaustive annotation of basal layer cells and their cell-cell contacts, we reached the surprising conclusion that cell-autonomous size control dominates over non-cell-autonomous signaling in regulating the G1/S transition. By quantitatively analyzing the microenvironment over time, we ruled out fluctuations in microenvironment geometry as direct causes of the G1/S transition in individual cells. This finding was further validated through cell-ablation experiments, where the loss of a neighboring cell was found to upregulate stem cell growth but not alter the average size at which cells enter S phase. These observations support the hypothesis that the decision to enter S phase is cell-autonomously driven, likely through the molecular coupling of the G1/S transition to cell size via the dilution of RB family proteins (Fig. 5E)22,25.

This cell-autonomous model of how the G1/S transition is controlled in vivo calls into question our previous understanding of cell cycle control in the context of tissue biology. Historically, studies have inferred from fixed cells or tissues that animal cells do not exhibit cell-autonomous size control, with cell cycle progression seemingly unaffected by cell size51. In these models, often in embryonic or developmental contexts, cell cycle progression and cell growth are thought to be independently controlled by cell-extrinsic signals52,53. The difference between our conclusions and previous developmental models of cell cycle control may be that during development both cell and tissue size are not kept in homeostasis, whereas in the adult they are. Thus, cell-autonomous size control could be a crucial mechanism that supports the maintenance of adult tissues.

Finally, we suspect that keeping efficient stem cell size homeostasis is important for maintaining tissue health throughout the organism’s lifespan because recent work linked stem cell enlargement to a loss of regeneration potential in the blood and intestine10. Indeed, blood and skin stem cells become increasingly large with age, which is coincident with their progressively declining function10,54. Therefore, understanding how cell-autonomous size control mechanisms break down during the aging process could yield new strategies for treating diseases associated with aging.

Methods

In vivo imaging and analysis of regenerating zebrafish osteoblasts

Zebrafish scale regeneration data were previously acquired and published33. Briefly, zebrafish were anesthetized in phenoxyethanol, and approximately 16–20 scales were manually removed with forceps from the caudal peduncle. The fish were then allowed to recover from anesthesia. Before long-term in vivo imaging, the fish was anesthetized in 0.01% tricane and embedded in a cool 1% agarose pad within a custom imaging dish. The fish was kept sufficiently anesthetized but alive using a custom water intubation system. The regenerating scales were imaged using a Leica SP8 microscope with 25x FLUOTAR water immersion lens every 20 min for over 24 h. This study used a dataset obtained from a transgenic animal expressing osteoblast-specific constructs of the FUCCI system: osx:mCherry-zCdt1 and osx:Venus-hGeminin33,55.

To track single osteoblasts, the time course images were first registered in 3D by finding the most similar z-slice across stacks, and finding the best rigid body transformation matrix using a Python wrapper of StackReg56. Registration was then manually adjusted. Individual cells were then tracked manually in Mastodon/FIJI (Supplementary Fig. S2)57,58. A 3D StarDist nuclear segmentation model was trained using approximately 1000 instances of nuclei segmented from the summed intensity of both FUCCI-G1 and FUCCI-S/G2/M channels59,60,61. Tracked cells were collated with segmentation predictions and all cell tracks were individually inspected and corrected for errors in napari62. Since mitosis was visible through the hGeminin-mVenus reporter, birth was determined as the frame at which the daughter nuclei are clearly defined. The G1/S transition was determined as the frame right before which the zCdt1-mCherry signal started to decrease in intensity (Fig. 1C).

Mouse lines

All mice were handled in accordance with the guidelines of the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee at Stanford University. The K14-H2B-Cerulean and R26p-FUCCI2 mice were kindly shared by Dr. Valentina Greco at Yale University. The Rb1-flox, Rbl1-/-, and Rosa26-CreERT2 mice were kindly shared by Dr. Julien Sage at Stanford Medical School. The Lgr5-DTR-GFP mice were kindly shared by Dr. Fred de Sauvage at Genentech. Unless otherwise noted, mice used for hindpaw skin imaging in the study were of the genotype K14-H2B-Cerulean; R26p-FUCCI2; Rosa26-CreERT2; Rb1-fl/fl. Wild-type mice refer to mice of this genotype that were never exposed to tamoxifen. For visualizing cell cycle phases, only the Cdt1-mCherry portion of the R26p-FUCCI2 reporter system was visible in our studies because the strong signal from the K14-H2B-Cerulean reporter masks the signal of the Geminin-mVenus reporter in the yellow channel. All mice imaged in the study were 3–7 months old and never used for breeding.

The mouse lines used in this study is presented in Table 1.

Cell culture

Low-passage NIH3T3 cells from ATCC were gifts from Dr. Scott Dixon at Stanford University. Mouse embryonic fibroblasts were generated by culturing minced wildtype E13 mouse embryos in DMEM for at least 3 passages. For all analyses, MEFs between passage 3 and passage 5 were used. hRPE-1 cells were gifts from Dr. Tim Stearns. Human embryonic stem cells (H9 hESCs) were gifts from Dr. Kyle Loh at Stanford Medical School and cultured in mTeSR1 (StemCell Technologiehs, 85850). V6.5 mouse embryonic stem cells (mESCs) were gifts from Dr. Marius Wernig at Stanford Medical School and cultured in 2i media (Sigma-Aldrich, SF016-200). Human mammary epithelial cells (HMECs) were gifts from Dr. Stephen Elledge at Harvard Medical School and cultured in MEGM mammary epithelial cell growth medium (Lonza, CC-3150). Low passage HEK293T cells were from ATCC. Primary hepatocytes were isolated from Fucci2 mice using two-step collagenase perfusion using Liver perfusion medium (Thermo Fisher Scientific, 17701038), liver digest medium (Thermo Fisher Scientific, 17703034) and hepatocyte wash medium (Thermo Fisher Scientific, 17704024). Unless otherwise noted, cells were maintained in Dulbecco’s modified Eagle’s medium with l-glutamine, glucose (4.5 g/liter), and sodium pyruvate (Corning), supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (Corning) and 1% penicillin/streptomycin. All cultures were maintained in 37 C with 5% CO2.

Lentiviral generation

The FUCCI-Cdt1-mKO2 reporter construct was cloned into the CSII-EF-MCS lentiviral payload vector under a constitutive EF1α promoter63. The payload vector, the lentiviral packaging vector dr8.74, and the envelope vector VSVg were transfected into HEK293T cells by PEI (1 mg/mL, Sigma-Aldrich). 48-60 h later, 10 mL of the lentivirus-containing medium was collected and filtered through a 0.45 µm filter. The viral supernatant was concentrated by centrifugation at 50,000 × g for 2:20 h at room temperature. The viral pellet was dried and resuspended in 0.5 mL IntestiCult medium (StemCell Technologies) supplemented with 10 µM Y-27632 and 2.5 µM CHIR-99021.

Intestinal organoid culture generation, maintenance, and engineering

Intestinal organoids expressing H2B-miRFP670, Cdt1-mCherry, and Geminin-Venus used for spheroid stage datasets were generated previously38. Intestinal organoids used for mature stage datasets were generated from a 3 month old male mouse bearing the Lgr5-DTR-GFP allele by established methods64,65. Briefly, the proximal 15 cm section of the small intestine was collected, opened longitudinally, and cut into small ~2 mm sections. The intestinal pieces were washed 20 times in PBS by pipetting up and down in 10 mL pipettes. The pieces were gently dissociated with EDTA and resuspended with PBS and 0.1% BSA and shaken vigorously. Four fractions of supernatant were collected, strained through a 70 µm cell strainer, and each fraction visually examined for intact crypt morphology. The best crypt fractions were concentrated and resuspended in a mixture of 50:50 IntesitCult medium (StemCell Technologies) to Matrigel (Corning) and plated as dome-shaped droplets within IntestiCult medium. For the maintenance of organoid cultures, IntestiCult media was changed every 2–3 days, and the culture was split by dissolving the Matrigel using ice-cold PBS and using mechanical dissociation through a narrow glass or plastic pipette tip. All organoids were cultured at 37 C with 5% CO2.

To express FUCCI-Cdt1-mKO2 in organoids, organoids were infected with lentivirus using previously established methods66. Briefly, organoid cultures were digested into single cell suspensions by incubating in TrypLE supplemented with 10 µM Y-27632 at 37 C for 3–5 min or until single cell dissociation is confirmed by visualization. The cells were strained with a 40 µm cell strainer and washed with DMEM/F12. Cells were then resuspended in 250 µL of IntestiCult medium supplemented with 10 µM Y-27632 and 2.5 µM CHIR-99021 that also contains the lentiviral preparation. Then, two wells from a 24-well plate were bottom-coated with Matrigel and allowed to solidify. The cell-virus suspension was plated atop the Matrigel and incubated overnight at 37 C. Next morning, the supernatant in the well containing viruses and dead cells were carefully discarded. An additional layer of Matrigel was then overlaid on top of the live cells that have attached to the bottom Matrigel layer. The whole well was then incubated with IntestiCult medium supplemented with 2.5 µM CHIR-99021. The CHIR-99021 was withdrawn 2–3 days later. The organoids were allowed to grow out from the primary viral induction. Single organoids expressing the FUCCI reporter were hand-picked and re-cultured from single cell suspensions for at least five passages before experiments.

Light-sheet microscopy and analysis

Organoid cultures used for imaging were transitioned from IntestiCult to ENR medium for at least 3 days. Organoid cultures were replated into a 1:1 mixture of Matrigel and ENR medium containing Advanced DMEM/F12 supplemented with 1x Penn/Strep, 1x GlutaMax (ThermoFisher), 1x B27 (Life Technologies #17504044), 1x N2 (Gibco #A1370701), 1 mM n-Acetylcysteine (Sigma), 50 ng/mL recombinant mouse EGF (Gibco #8044), 100 ng/mL recombinant mouse Noggin (R&D Systems #1967-NG), and 500 ng ng/mL recombinant mouse R-Spondin1 (R&D Systems #7150-RS).

Preparation of organoids for light-sheet microscopy followed methods previously established38. To prepare spheroid-stage organoids, organoid cultures were dissociated with TrypLE, strained through a 30 µm cell strainer and live cells were sorted as single cells by FACS. The collected single cells were seeded at a density of 3000 cells per 5 µL of ENR medium supplemented with 20% Wnt3a-conditioned medium, 10 µM Y2-27632, and 3 µM CHIR99021. The organoids were grown for 3 days until they reached spheroid morphology before movie acquisition began.

To prepare mature stage organoids, organoid cultures were mechanically dissociated by triturating through a P100 or P200 pipette tip and resuspended in a 60:40 mixture of Matrigel and ENR medium. The mixture was placed as 5 µL drops into a custom imaging chamber and incubated with ENR medium for 1 additional day before being transferred into the microscope chamber.

To image organoids, a LS1-Live dual illumination and inverted detection light-sheet microscope by Viventis Microscopy Sàrl was used. For spheroid stage datasets, organoids that formed well-defined cystic shapes were selected and imaged every 10 min for up to 40 h, with z-spacing of 2 µm. For mature stage datasets, organoids with visible budded regions were selected and imaged every 10 min for up to 2.5 days, with z-spacing of 0.67 µm. The medium was exchanged every day.

For analysis, lightsheet movies were first deconvolved using Huygen Software by Scientific Volume Imaging or denoise and deconvolved using LSTree, utilizing empirically measured point spread functions38. The movies were then indexed using BigDataViewer to facilitate image viewing on small-memory computers67.

For spheroid stage organoids, LSTree was used to generate a preliminary prediction of single-cell 3D segmentation and tracking based on H2B-miRFP670 reporter signal38. The predicted lineage trees were extensively corrected manually using Mastodon, and the segmentation was corrected using napari. For spheroid stage organoids, all cells in the organoids were segmented and tracked. The birth frame was determined as the first frame in which the daughter cell chromosome is no longer condensed (Supplementary Fig. S4B). The G1 exit frame was determined as the frame at which the FUCCI-G1 reporter intensity started to decrease (Supplementary Fig. S4D). To quantify growth rates, a smoothing cubic spline was used to fit the nuclear volume curve, and its derivative was used to estimate instantaneous growth rates.

For mature stage organoids, MaMuT or Mastodon was used to manually track single cells within the budded region of organoids68. Mature stage cells were only tracked from birth to G1/S transition. The birth frame was defined as the frame at which the nuclear volume became distinguishable from the background fluorescence and the G1/S transition frame was the frame in which the FUCCI-G1 reporter intensity started to decrease (Fig. 1I). The birth frame, G1 exit frames, and spatial locations of single cells were then used to select cells for manual nuclear segmentation using napari. For each cell, an estimate of its nuclear volume at birth and at the G1/S transition was averaged from the first and last 2–3 frames in which the FUCCI-G1 nuclear signal was visible above background, respectively. To quantify nuclear growth rates, nuclear volume was segmented for each cell every 30 min, and a smoothing cubic spline was used to fit the growth curves to generate estimates of instantaneous growth rates. Stem cells were identified by a clear border of Lgr5-GFP signal all around a cell’s nucleus (Supplementary Fig. S5B). TA cells were identified by the absence of Lgr5-GFP and if a cell exited G1 phase by degrading the FUCCI-G1 reporter, indicating active cycling (Supplementary Fig. S5C).

Longitudinal intravital imaging

The longitudinal imaging of the same mouse skin region was performed based on protocols previously described43,44,45. At least one week prior to imaging experiments, the mouse ear was depilated using a depilating cream (Nair). During imaging, the mouse was kept under anesthesia by isoflurane inhalation through a nose cone and kept warm by a rodent heating pad. The mouse paw or ear skin was immobilized between a custom-made stage arm and another stage arm holding a coverslip. The coverslip pressure was kept to a minimum to immobilize the tissue without deforming it. To find the same tissue regions over time, extensive cartographic notes were taken noting the idiosyncratic features of the skin itself, including folds, hair follicle patterns, and blood vessel patterns. The exact matching tissue region was confirmed by close comparison of the underlying dermal collagen signal from session to session. Images were taken on a Prairie View Ultima IV (Brucker) scope equipped with a Mai Tai DeepSee Ti:sapphire tunable laser, 690-1040 nm (Spectra Physics, Newport). The sample was imaged with either an Olympus XLUMPLFLN 20x water-dipping objective (NA = 0.95) or an Olympus LMUPlanFl/IR 40x water-dipping objective (NA = 0.8). For visualizing Cerulean, the excitation laser was tuned to 920 nm or 940 nm and both 460/50 nm and 525/50 nm bandpass filter channels were used. To visualize mCherry, the excitation laser was tuned to 1020 nm or 1040 nm and a bandpass filter of 595/50 nm was used. Collagen fibrils were visualized with 460/50 nm bandpass filter using 920-940 nm excitation or 525/50 nm bandpass filter using 1020-1040 nm excitation.

Segmenting and tracking single cells in longitudinal skin images

A custom image analysis pipeline was built to register, segment, and track epidermal stem cells in the basal layer, in part based on previous work32. The longitudinally acquired images were first registered using the second-harmonic generation collagen signal, since collagen fibrils rarely change during skin homeostasis (Supplementary Movie S5-6). Cross-correlation was used to identify the respective z-positions between two time points that corresponded to each other, and StackReg was used to register the two tissue volumes. If bending or warping of the tissue impeded successful tracking of cells, then BigWarp in FIJI was optionally used to nonrigidly warp the tissues using collagen landmarks69. Nuclear image volumes were first treated with local contrast equalization using equalize_adapthist from scikit-image70. Cellpose was then used in 3D stitching mode to segment the nuclear volumes in 3D, using the pretrained nuc model71. Independently, single cells were manually tracked from birth to division (or only until G1 exit) using MaMuT or Mastodon and BigDataViewer in FIJI67,68. Then, the coordinates of the single cell tracks were mapped onto the registered movie, and the corresponding nuclear segmentations were collated. To preserve cell volume, if BigWarp was used to register the movie, the nonrigid transformations were reversed and tracking coordinates mapped back onto untransformed images. napari was used for manually inspecting, curating, and editing the 3D segmentations. Cell cycle timings were manually annotated. Birth frame was determined as the first frame in which the daughter cell is visible. The G1 exit frame was the frame in which the FUCCI-G1 signal significantly decreased compared to the previous frame (Supplementary Fig. S9 E-F; Supplementary Fig. S21). This is equivalent to the previous frame being the G1/S transition frame. This frame was determined manually by both inspecting the image series as well as the total intensity time series. Any cell where this drop in intensity was ambiguous was discarded from analysis. The division frame was determined as the final frame before daughter cells are visible. If the cell was in mitosis during its division frame, no division nuclear volume was recorded since the nuclear volume becomes undefined in mitosis. A final script was used to collate the segmented and tracked cells with the cell cycle timing annotations to generate time-series measurements for every tracked epidermal stem cell. See Supplementary Fig. S6 for a graphical representation of the pipeline.

Throughout the paper, except for in Fig. 4, nuclear volume was used as an approximate proxy for cell volume, since we and others have previously reported that nuclear and cell volumes are directly proportional to each other, with their linear regression line passing through the origin (Supplementary Fig. S3C)32,72. For DKO cells, because the duration of G1 phase was rendered very short (median = 28 h) by the mutations, we were unable to accurately estimate the precise size at the G1/S transition with our 12 h sampling rate. However, the change in the duration of G1 duration compared to SKO cells at different sizes is well-estimated by our sampling (see Sampling rate analysis and Supplementary Fig. S10).

Induction of CreER activity using tamoxifen or 4OHT

To induce CreER activity in the paw skin, 10 mg/mL tamoxifen dissolved in corn oil was introduced via intraperitoneal injection to the mouse abdomen for 3–5 days consecutively. Subsequently, the mice were imaged 4–5 weeks post-injection for Rb1–/– single mutant experiments. Two pairs of male littermates were used, aged 4 month and 6 months at the beginning of the experiment.

For DKO experiments, topical application of 4OHT to the thinner ear skin was instead used to directly compare SKO and DKO tissues in the same animal. A 3 month old male of mixed strain was used. Also, whole body Rb1–/–; Rbl1–/– animals became sickly and we wanted to avoid systemic effects arising from outside the epidermis. A slurry of 4OHT was applied topically to the ear skin, consisting of a solution of ethanol and 2 mg/mL of 4OHT mixed with 1 g of petroleum jelly (Vaseline). 100 mg of the 4OHT slurry was then applied on top of the ear of an isoflurane-anesthetized mouse, let incubate for 30 min, and washed thoroughly. As a control, ethanol-only slurry was applied to the other ear. The mouse was imaged every 12 h from 24 h before to 8 days after 4OHT treatment.

siRNA knockdown

Lipofectamine RNAiMAX (Invitrogen) was used for siRNA transfection. For 24-well plates and LabTek 4-well chambers, cells were plated 1 day prior so that they were ~40% confluent at the time of transfection. For each well, 6 pmol of siRNA in 50 μl of Opti-MEM was mixed with 1 μl of RNAiMAX in 50 μl of Opti-MEM. After 10 to 20 min of incubation at room temperature, the mixture was added to the cells. Two days later, the cells were lysed for qPCR analysis. To analyze the steady-state behavior of Rbl1 in the absence of Rb1, cells transfected with Rb1 RNAi after 48 h were passaged and reverse-transfected into a new LabTek 4-well chamber containing a second round of siRNA-RNAiMAX. The cells were cultured for 48 h more hours, fixed at 96 h post initial round of siRNA transfection, and further processed for immunofluorescence analysis. Silencer Select siRNA constructs (Ambion, Thermo Fisher) targeting negative control (#4390843), mouse Rb1 (siRNA ID: #s72763, catalog #4390771), and mouse Rbl1 (siRNA ID: #151420, Catalog: #AM16708) were used. For larger 6-well plates, the reaction was scaled up by 5x.

qPCR analysis

Total RNA was isolated using a Direct-zol RNA Miniprep kit (Zymo Research). For RT-qPCR, cDNA synthesis was performed with 1 μg of total RNA using an iScript Reverse Transcription Kit (Bio-Rad). qPCR reactions were made with the 2x SYBR Green Master Mix (Bio-Rad). Gene expression levels were measured using the ΔΔCt method. PrimeTime PreDesigned primers (IDT) were used to design primer sets against murine genes Actb, Rps18, Gapdh, Rb1, and Rbl1.

Western blotting analysis

NIH3T3 cells were directly lysed with 1× NuPAGE LDS sample buffer (Invitrogen) and then incubated at 95 °C for 10 min. Lysates were separated on NuPAGE 10% tris-acetate protein gels (Thermo Fisher Scientific) and transferred to nitrocellulose membranes. Membranes were then blocked with SuperBlock (tris-buffered saline) blocking buffer (Thermo Fisher Scientific) and incubated overnight at 4 °C with primary antibodies in 3% BSA solution in PBS. The primary antibodies were detected using the fluorescently labeled secondary antibodies IRDye 680LT goat anti-mouse IgG (LI-COR, 926-68020) and IRDye 800CW goat anti-rabbit IgG (LI-COR, 926-32211). Membranes were imaged on a LI-COR Odyssey CLx and analyzed with LI-COR Image Studio software. Primary antibodies: β-actin (Sigma-Aldrich # A2103, rabbit monoclonal; 1:2000) and Rb1 (Santa Cruz Biotechnology #sc-74570, mouse monoclonal; 1:500).

Immunofluorescence analysis in 2D cell culture and intestinal organoids

2D cell cultures or Intestinal organoid cultures were grown in 4-chamber LabTek chamber slides. Cells were fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde at room temperature, 10 min for NIH3T3 and MEFs, and 30 min for organoids. 2D cells were blocked with 1% BSA, 5% normal goat serum, 1% fish gelatin, and 0.1% Triton-X in PBS. Organoids were blocked and permeabilized with 1% BSA and 2% Triton-X in PBS. Cells were stained overnight at 4 C with primary antibodies, in their respective blocking buffers. Then, they were washed three times in PBS and stained overnight at 4 C with secondary antibodies. Lastly, samples were washed 3x in PBS, stained with DAPI or Hoechst, and stored in PBS. Primary antibodies: β-Catenin (BD Transduction Laboratories # 610154, monoclonal mouse, 1:400), Rb1 (Santa Cruz Biotechnology #sc-74570, monoclonal mouse, 1:50), RNA Polymerase RPB1 (Abcam, monoclonal rat, #ab252854, 1:200), Histone H3 (Cell Signaling Technology, monoclonal rabbit, #4499, 1:200), and Rbl1 (Abcam, polyclonal rabbit, #209546, 1:200). Secondary antibodies: Goat anti-Mouse IgG (H + L) Highly Cross-Adsorbed Secondary Antibody, Alexa Fluor™ Plus 647 (Invitrogen #A32728, 1:1000), Goat anti-Rabbit IgG (H + L) Highly Cross-Adsorbed Secondary Antibody, Alexa Fluor™ Plus 488 (Invitrogen #A11034, 1:1000), and Goat anti-Mouse IgG (H + L) Highly Cross-Adsorbed Secondary Antibody, Alexa Fluor™ Plus 488 (Invitrogen #A11029, 1:1000).

2D cells were imaged using a Zeiss Axio Observer Z1 microscope with Zyla 5.5 scMOS camera (Andor) and a Zeiss A-plan 10x Ph1 objective (NA = 0.25). Organoids were imaged using a Zeiss 880 confocal microscope using a Zeiss EC Plan Neofluar 40x oil immersion lens (NA = 1.3). napari was used to manually segment nuclear and cell volumes for 3D images (Supplementary Fig. S3B).

StarDist model 2D_versatile_fluo was used to automatically segment individual nuclei for 2D cell cultures (Supplementary Fig. S11D). For quantification of total DNA or protein, a median background intensity was estimated from pixels not within any nuclear mask and subtracted from the DNA or protein image. Nuclear volume was estimated using an ellipsoid approximation, where an ellipse was fitted 2D nuclear shape, its major and minor axis calculated, and volume estimated as the product of the major axis times the square of the minor axis, up to a constant multiplicative factor. Total DNA or protein intensity per nuclear mask was measured for each cell from the nuclear mask and the background-subtracted intensity image. Total DAPI intensity and nuclear volume were then used to gate for 2 N cells.

For Rbl1 concentration estimations, to more carefully subtract background fluorescence and compare across siRNA conditions, the total Rbl1 signal in each cell was calculated as described above from the raw Rbl1 immunofluorescence image without any median intensity background subtraction. Then, cells in the Rbl1-knockdown condition were binned by their nuclear volume, and a median background Rbl1 intensity was determined per nuclear size bin (Supplementary Fig. S12F). This size-dependent background intensity was then used to subtract from the median Rbl1 staining in Control-knockdown and Rb1-knockdown conditions for the same nuclear volume bin, resulting in comparable background-subtracted size-resolved quantifications.

Whole mount epidermal immunofluorescence

Mouse epidermal tissues were prepared for whole mount imaging of interfollicular tissues according to established dissection methods43. Mice were sacrificed by overdose of isoflurane anesthesia. The ear was depilated postmortem. The ear and paw were collected, and the entire skin was dissected away from muscle and cartilage tissues. The skin was then incubated floating on top of a solution of PBS and 5 mg/mL Dispase for 15-20 min at 37 C. Superfine forceps were used to manually dissect the epidermal layer from the dermis under a dissecting scope. The epidermal tissue was then fixed by floating atop a solution of PBS and 4% PFA for 30 min at room temperature. The fixed tissue was then washed and blocked (5% normal goat serum, 1% BSA, 0.2% gelatin, and 2% Triton-X in PBS) before being incubated overnight with a primary antibody. Then, the samples were washed three times and incubated with a secondary antibody. Primary antibodies: phospho-RB1[S807/S811] (Cell Signaling Technology #9308, monoclonal rabbit 1:200); 53BP1 (Novus Biologicals #NB100-304, monoclonal rabbit 1:200); Keratin 10 (Biolegends #19054, polyclonal rabbit 1:200). Secondary antibodies: Goat anti-Rabbit IgG (H + L) Highly Cross-Adsorbed Secondary Antibody, Alexa Fluor™ Plus 647 (Invitrogen #A32733, 1:1000). Stained samples were washed three times in PBS and then mounted in Vectashield Antifade Mounting Medium (Vecta Laboratories #H-1000-10) on glass slides. Finally, the samples were imaged using a Zeiss 880 or Zeiss 980 confocal microscope using a 40X oil immersion objective. A phospho-Rb1 antibody was used due to poor staining by Rb1 antibodies. 53BP1 foci were manually counted.

Sampling rate analysis

To estimate the effect of reduced temporal sampling on cell size control measurements, we first down sampled the in vivo skin stem cell dataset, and recalculated cell size control correlations. We found that sampling every 24 h instead of the original 12 h did not have significant impact on the correlation between birth size and cell growth in G1 (Supplementary Fig. S10A). Then, to test whether the correlation between birth size and G1 growth or G1 duration was more robust in the face of temporal undersampling, we modeled exponentially growing cells that either obeyed idealized ‘sizer’ (divide when cell size meets a threshold) or ‘adder’ (divide when cell growth meets threshold) behaviors. Then, we subsampled the growth curves of these cells using increasingly coarse temporal sampling rates (Supplementary Fig. S10B). We found that the correlation between birth size and G1 duration is more robust to temporal undersampling compared to the correlation between birth size and G1 growth (Supplementary Fig. S10C, D).

Measurement of the epidermal stem cell microenvironment

A custom image analysis pipeline was built to densely annotate cell and nuclear shapes in order to measure the microenvironment surrounding stem cells of interest. We used existing imaging data published by the Greco group, which were derived from movies of basal layer stem cells growing in a mouse expressing K14-H2B-Cerulean, FUCCI-mCherry, and K14-Actin-GFP44. We had previously sparsely annotated the majority of all stem cells that complete a cell cycle within the 7 day duration of the movie32. For this study, we built new tools to annotate each dividing cell’s microenvironment by quantifying the rest of the tissue.

To densely annotate the rest of the cells in the tissue, we used Cellpose running in 3D stitching mode to segment the images using the pretrained ‘nuc’ and ‘cyto2’ models (Supplementary Fig. S13A, B). To find the basal layer cells, we automatically annotated the location of the basement membrane (BM). We used a Gaussian blurring filter with large sigmas (25–30 for xy, 5–10 for z) to blur the H2B-Cerulean images. The first-derivative of the profiles of the blurred intensity were generated at each x,y pixel position, and the z-slice that maximized the first-derivative magnitude was determined as the location of the BM (Supplementary Fig. S13D). Using the BM location, basal layer cells could initially be identified. Then, napari was used to fine-tune basal cell identification, correct segmentation errors, as well as add back basal cells that were missing from the initial segmentation. For the purposes of this analysis, the K14-ActinGFP signal was examined manually and any cell that had a visible basal footprint immediately above the BM were counted as a ‘basal layer cell’, even if that footprint was very small and likely in the process of delamination. The cell’s height from the BM was recorded to capture the spectrum of the delamination process.

The cortical channel was then carefully examined to determine which cells shared a cell-cell interface and the information encoded in a 2D contact image (Supplementary Fig. S13C). Finally, the 3D cortical segmentation was manually inspected and error-corrected using napari. To characterize apical and basal cell area, the original image volume was re-sliced to generate a flattened version of the tissue (Supplementary Fig. S13E). The cell’s apical and basal areas were calculated as the average area of the 3 top-most and bottom-most slices, respectively.

Finally, since collagen orientation is thought to guide keratinocyte growth in development, we also measured the properties of the dermal collagen fibrils in relation to basal layer cells73. To do so, gradient images were calculated from a flattened version of the collagen signal 3 µm below the basal layer and smoothed with a Gaussian filter (sigma=4px). For each cell, its basal footprint was created from the flattened reslice of the tissue, and a local average Jacobian matrix was calculated based on the local collagen signal gradients. Then, the eigenvalues and eigenvectors of the local Jacobian matrix were found. The orientation of the fibrils was defined as the directionality of the principal eigenvector, while a ‘coherence’ metric was defined as the ratio of the two eigenvalues, which reports the degree of alignment amongst the local fibers (Supplementary Fig. S13F). A triangular mesh model of the basal layer surface was generated using the library trimesh and used to calculate the local tissue curvature (Supplementary Fig. S13D)74. Finally, cell bodies that do not express the K14-H2B-Cerulean reporter are often visible throughout the epidermal layer based on a coherent cell-like shadow. These dark cell bodies likely correspond to resident macrophages, melanocytes, or other non-keratinocytes75. The locations of these cells were annotated and incorporated into the model (Supplementary Fig. S13D).

For each basal cell nuclear and cell annotation, regionprops from scikit-image was used to generate individual object statistics, including cell and nuclear shapes and positions. In addition, for each previously tracked dividing stem cell of interest, statistics about the neighboring cells were calculated or collated in custom Python scripts. Although more than 130 features were generated, ultimately only a total of 38 features were kept in the analysis. An example cell and six of its microenvironment statistics are shown in Supplementary Fig. S14.

Many co-correlated features were eliminated or combined into ratiometric features. For example, while cell volume was kept, cell surface area (SA) and nuclear volume were transformed into SA-to-volume and nuclear-to-cytoplasmic volume ratios. The resulting feature-set has relatively low covariance amongst the individual features and a reasonable condition number (C = 34.5, using the minimum covariance determinant as the estimator of the covariance matrix) (Supplementary Fig. S15A). A similar condition number (35.3) was obtained using the empirical covariance matrix. When principal component analysis (PCA) was performed using PCA from scikit-learn, the variance was reasonably evenly weighted amongst the components, with the top 3 components combined only explaining <25% of total variance (Supplementary Fig. S15B)76. Therefore, we decided to directly use the 38 features for constructing statistical models.

The features used in the model are presented in Table 2:

Measurement of organoid cellular microenvironment

The LSTree framework was used to process spheroid stage organoid datasets in order to extract cell and microenvironment features (Supplementary Fig. S18A)38. All nuclei in the organoid were manually inspected for the correct lineage, tracking, and segmentation. To extract the overall organoid shape, aics-shparam was used to parametrize a spherical harmonic mesh model (l = 5) from the coordinates of all cell nuclei72. From this 3D organoid mesh model, mean surface curvatures and geodesic neighborhoods (defined as within 12 µm from the center cell) surrounding each nucleus were calculated using trimesh (Supplementary Fig. S18B, C). The spheroid stage movies were analyzed for the first ~10 h of after the beginning of the movie, prior to the cells the organoids synchronously arresting and establishing a nascent crypt bud.

The features used in the model are presented in Table 3.

Statistical modeling of cell cycle phase

Statistical models were built using the Python libraries scikit-learn and statsmodels76,77. For logistic regression, either logit from statsmodels or LogisticRegression from scikit-learn were used. For random forest classification, RandomForestClassifier from scikit-learn was used. For multi-linear regression, we used LinearRegression from scikit-learn. Prior to training, all features were standardized to have a mean of 0 and standard deviation of 1.

Since cells spend more time in G1 phase, we rebalanced the training examples by randomly subsampling (without replacement) from a total of 567 G1 examples down to 200 instances, which is comparable to 140 instances of S/G2 cells. This subsampling was randomly repeated each time a new model is trained. For all models, unless indicated otherwise, model metrics are reported as the mean model performance as evaluated on 10% of the data that were withheld from the training. For classification models aiming to predict whether cells have or have not passed the G1/S transition, we only kept data from the single movie frame immediately following the transition into S phase. Including the remaining S/G2 timepoints did not significantly change our findings (Supplementary Fig. S16G), although the NC ratio became statistically significant in leave-one-out tests, but not in permutation tests (Supplementary Fig. S16H–I).

To analyze the contribution of each feature to the statistical power of the models, we re-evaluated the model performance (AUC) when each feature was dropped from the model, or when only a single feature was included in the model. To estimate the performance of a null model, we generated a random-feature model using a feature-set of the same size, but where each feature was instead drawn randomly from a Gaussian distribution with mean 0 and sigma 1.

To evaluate whether cell volume remains the leading predictor of the G1/S transition with other model structures, we also trained a statistical model on PCA-diagonalized data using logistic regression model as well as a random forest classifier trained on the untransformed feature-set. When PCA components were used to generate logistic regression models, only PC1 had a significant contribution to the model power, either via single feature permutation test implemented by permutation_importance from scikit-learn, or when it was the sole feature in the model (Supplementary Fig. S17A–C). The topmost feature of PC1 was cell volume (Supplementary Fig. S14C), and when we examined how much of total cell volume weight was placed into each PC, PC1 accounted for nearly 40% of cell volume’s total weight (Supplementary Fig. S17D). When cell cycle classification was performed with a random forest classifier on the original feature-set, the model performed similarly to logistic regression models (Supplementary Fig. S17E). Similar to the logistic regression model, random forest models where a single-feature was permuted or only a single feature was included, also reveal that cell volume is the most important feature (Supplementary Fig. S1EF, G). Therefore, both the PCA-logistic regression model and the random forest models are consistent with our conclusion that cell volume is likely the major contributor to the accurate classification of cell cycle phase in basal layer stem cells.

To predict total cell cycle duration, we used cell birth size and G1 phase growth rate as endogenous variables. G1 phase growth rate was estimated by fitting exponential growth to cell growth time series in G1 phase. These were used to construct models to predict total cell cycle duration (Fig. 3G) and calculate a coefficient of determination between predicted and measured durations (R2 = 0.56). Since our measurement of total cell cycle duration is discretized by 12 h intervals, we calculated the maximum attainable Rmax2 = 0.88 by discretizing a continuous normal distribution. We then reported the normalized R2 = 0.64.

To determine whether cell volume or nuclear volume is more accurate at predicting cell cycle phase, we tested logistic regression models using either cell volume or nuclear volume as the endogenous variable. We found that single-variable models that used cell or nuclear volume perform nearly as well as each other, although cell volume had slightly better performance (Supplementary Fig. S16D). We concluded that we likely cannot distinguish cell and nuclear volume based on our measurements. We chose include cell volume as an independent variable in our analysis and incorporated any extra information from nuclear volume by using the nuclear-to-cytoplasmic ratio.

Similar methods were used to fit multiple-logistic regression models of cell cycle dynamics in organoids or in vitro cell culture data of wild-type HMEC cells previously acquired by our lab50. For HMECs, nuclear volume was used to test the accuracy of cell cycle classification (Supplementary Fig. S18). For organoids, both cell and microenvironment features were used to predict cell cycle classification (Supplementary Fig. S19D-G).

Laser ablation of single cells

The selective ablation of single cells was done similarly to previous methods44. A two-photon laser was tuned to 810 nm and used to continuously image a diffraction-limited spot in the middle of a cell nucleus with 20–30% of the total laser power for 15 s. For each experiment, 4–6 cells spaced approximately 100 µm apart were picked for ablation. Before and after each ablation, an image was taken using normal laser settings to ensure that the intended target received the laser dose. 12 h after the ablation, we took time-series of same skin region every 4–6 h for at least 18 h, followed by a final time point at 36 h or 48 h post-ablation. Nuclear volume growth curves were measured as described above, and an exponential growth rate was determined using curve_fit from scipy, assuming an exponential growth function (Supplementary Fig. S20F). Ablation-neighboring cells grew faster than non-neighboring cells, whether counting all neighboring cells or only the cells that enter S phase (Supplementary Fig. S20G). We then manually counted the fraction of cells that enter S phase in each mouse in ablation-neighboring or non-neighboring regions and found that cells in ablation-neighboring regions are more likely to enter S phase (Supplementary Fig. S20H). Finally, we find that there is a non-linear spatial relationship between individual cell growth rate and distance to ablation sites (Supplementary Fig. S20I), with cells that are 10–20 µm away from the ablation site growing faster.

Statistics and reproducibility

Single-variable linear regression was calculated using polyfit from NumPy or LinearRegression and Lasso from scikit-learn. We checked that using LASSO regularization did not change the regression coefficient for all slopes beyond <0.1%. For all linear regressions shown, pvalue corresponds to the T test statistical significance compared with a null-model where the slope of the linear regression is 0. For Pearson’s correlation, pvalue corresponds T test against a null-model where the correlation is 0. For intestinal organoids, we included data from N = 3 spheroid stage and 3 mature organoids. n = 75 spheroid cells, 71 stem cells, 76 TA cells.

Software

In addition to specific software or libraries noted elsewhere, all computation was done using Python libraries NumPy, SciPy, and Pandas78,79,80,81. Visualization was done using matplotlib and seaborn82,83. 3D image volume visualization was done using napari or PyVista84.

Reporting summary

Further information on research design is available in the Nature Portfolio Reporting Summary linked to this article.

Data availability

A minimum dataset generated in this study has been deposited in https://github.com/skotheimlab/xie_etal_2025_autonomous_cell_size_control/test_data.zip. The raw microscopy data used in Fig. 1 was previously published in33. The raw microscopy data used in Fig. 3 was previously published in44. Source data are provided with this paper. Due to space constraints, other raw microscopy data are available upon request to Jan Skotheim. Source data are provided with this paper.

Code availability

All code is available at https://github.com/skotheimlab/xie_etal_2025_autonomous_cell_size_control85.

References

Xie, S., Swaffer, M. & Skotheim, J. M. Eukaryotic cell size control and its relation to biosynthesis and senescence. Ann. Rev. Cell Dev. Biol. 38, 291–319 (2022).

Ramanathan, S. P., Krajnc, M. & Gibson, M. C. Cell-size pleomorphism drives aberrant clone dispersal in proliferating epithelia. Dev. Cell 51, 49–61.e4 (2019).

Cachoux, V. M. L. et al. Epithelial apoptotic pattern emerges from global and local regulation by cell apical area. Curr. Biol. 33, 4807–4826.e6 (2023).

Gong, Y. et al. A cell size threshold triggers commitment to stomatal fate in Arabidopsis. Sci. Adv. 9, eadf3497 (2023).

Hubatsch, L. et al. A cell-size threshold limits cell polarity and asymmetric division potential. Nat. Phys. 15, 1078–1085 (2019).

Lanz, M. C. et al. Increasing cell size remodels the proteome and promotes senescence. Mol. Cell 82, 3255–3269.e8 (2022).

Lanz, M. C., Fuentes Valenzuela, L., Elias, J. E. & Skotheim, J. M. Cell size contributes to single-cell proteome variation. J. Proteome Res. 22, 3773–3779 (2023).

Chen, Y., Zhao, G., Zahumensky, J., Honey, S. & Futcher, B. Differential scaling of gene expression with cell size may explain size control in budding yeast. Mol. cell 78, 359–370.e6 (2020).

Neurohr, G. E. et al. Excessive cell growth causes cytoplasm dilution and contributes to senescence. Cell 176, 1083–1097.e18 (2019).

Lengefeld, J. et al. Cell size is a determinant of stem cell potential during aging. Sci. Adv. 7, eabk0271 (2021).

Manohar, S. et al. Genome homeostasis defects drive enlarged cells into senescence. Mol. Cell 83, 4032–4046.e6 (2023).

Ginzberg, M. B., Kafri, R. & Kirschner, M. On being the right (cell) size. Science 348, 1245075–1245075 (2015).

Zatulovskiy, E. & Skotheim, J. M. On the molecular mechanisms regulating animal cell size homeostasis. Trends Genet. 36, 360–372 (2020).

Øvrebø, J. I., Ma, Y. & Edgar, B. A. Cell growth and the cell cycle: New insights about persistent questions. BioEssays 44, 2200150 (2022).

Liu, S., Tan, C., Tyers, M., Zetterberg, A. & Kafri, R. What programs the size of animal cells? Front. Cell Dev. Biol. 10 https://doi.org/10.3389/fcell.2022.949382 (2022).

Ward, P. S. & Thompson, C. B. Signaling in control of cell growth and metabolism. Cold Spring Harb. Perspect. Biol. 4, a006783 (2012).

Shaya, O. et al. Cell-cell contact area affects notch signaling and notch-dependent patterning. Dev. Cell 40, 505–511.e6 (2017).

Guisoni, N., Martinez-Corral, R., Garcia-Ojalvo, J. & de Navascués, J. Diversity of fate outcomes in cell pairs under lateral inhibition. Development 144, 1177–1186 (2017).

Pentinmikko, N. et al. Cellular shape reinforces niche to stem cell signaling in the small intestine. Sci. Adv. 8, eabm1847 (2022).

Hatton, I. A. et al. The human cell count and size distribution. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 120, e2303077120 (2023).

Schmoller, K. M., Turner, J. J., Kõivomägi, M. & Skotheim, J. M. Dilution of the cell cycle inhibitor Whi5 controls budding-yeast cell size. Nature 526, 268–272 (2015).

Zatulovskiy, E., Zhang, S., Berenson, D. F., Topacio, B. R. & Skotheim, J. M. Cell growth dilutes the cell cycle inhibitor Rb to trigger cell division. Science 369, 466–471 (2020).

D’Ario, M. et al. Cell size controlled in plants using DNA content as an internal scale. Science 372, 1176–1181 (2021).

Liu, D., Lopez-Paz, C., Li, Y., Zhuang, X. & Umen, J. Subscaling of a cytosolic RNA binding protein governs cell size homeostasis in the multiple fission alga Chlamydomonas. PLOS Genet. 20, e1010503 (2024).

Zhang, S., Zatulovskiy, E., Arand, J., Sage, J. & Skotheim, J. M. The cell cycle inhibitor RB is diluted in G1 and contributes to controlling cell size in the mouse liver. Front. Cell Dev. Biol. 10 https://doi.org/10.3389/fcell.2022.965595 (2022).

Ginzberg, M. B. et al. Cell size sensing in animal cells coordinates anabolic growth rates and cell cycle progression to maintain cell size uniformity. eLife 7, 7729 (2018).

Varsano, G., Wang, Y. & Wu, M. Probing mammalian cell size homeostasis by channel-assisted cell reshaping. Cell Rep. 20, 397–410 (2017).

Cadart, C. et al. Size control in mammalian cells involves modulation of both growth rate and cell cycle duration. Nat. Commun. 9, 1–15 (2018).

Liu, X., Yan, J. & Kirschner, M. W. Cell size homeostasis is tightly controlled throughout the cell cycle. PLOS Biol. 22, e3002453 (2024).

Echave, P., Conlon, I. J. & Lloyd, A. C. Cell size regulation in mammalian cells. Cell Cycle 6, 218–224 (2007).

Devany, J., Falk, M. J., Holt, L. J., Murugan, A. & Gardel, M. L. Epithelial tissue confinement inhibits cell growth and leads to volume-reducing divisions. Dev. Cell 58, 1462–1476.e8 (2023).

Xie, S. & Skotheim, J. M. A G1 sizer coordinates growth and division in the mouse epidermis. Curr. Biol. 30, 916–924.e2 (2020).

Cox, B. D. et al. In toto imaging of dynamic osteoblast behaviors in regenerating skeletal bone. Curr. Biol. 28, 3937–3947.e4 (2018).

Iwasaki, M., Kuroda, J., Kawakami, K. & Wada, H. Epidermal regulation of bone morphogenesis through the development and regeneration of osteoblasts in the zebrafish scale. Dev. Biol. 437, 105–119 (2018).

Kretzschmar, K. & Clevers, H. Organoids: Modeling development and the stem cell niche in a dish. Dev. Cell 38, 590–600 (2016).

Serra, D. et al. Self-organization and symmetry breaking in intestinal organoid development. Nature 569, 66–72 (2019).

Yang, Q. et al. Cell fate coordinates mechano-osmotic forces in intestinal crypt formation. Nat. Cell Biol. 23, 733–744 (2021).

De Medeiros, G. et al. Multiscale light-sheet organoid imaging framework. Nat. Commun. 13, 4864 (2022).

Abe, T. et al. Visualization of cell cycle in mouse embryos with Fucci2 reporter directed by Rosa26 promoter. Development 140, 237–246 (2013).

Tian, H. et al. A reserve stem cell population in small intestine renders Lgr5-positive cells dispensable. Nature 478, 255–259 (2011).

Sakaue-Sawano, A. et al. Visualizing Spatiotemporal Dynamics of Multicellular Cell-Cycle Progression. Cell 132, 487–498 (2008).