Abstract

Chan-Lam coupling represents one of the most reliable methods for constructing C(sp2)−N bonds under mild conditions. However, application of this technology as a general platform for C(sp3)−N bond assembly remains a longstanding challenge due to the inherent limitation in boron-to-copper transmetalation. In contrast to the conventional two-electron process, the rapid capture of alkyl radicals by copper(II) complex affording the reactive high-valent copper(III) intermediate, has become a key part of the emerging approaches to forge C(sp3)−N bonds. Here, we report an N-alkylation protocol that overcomes the limitations of Chan-Lam coupling by using versatile alkylboronic pinacol esters (APEs) as radical precursors via aminyl radical-mediated boron abstraction. This distinct approach enables a versatile N-alkylation applicable to a wide range of APEs and N-nucleophiles with diverse functional groups. Synthetic utility of this protocol is further demonstrated by its ease of scalability, sequential N-alkylation of substrate with multiple reactive sites, and the late-stage modification of several complex bioactive materials.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

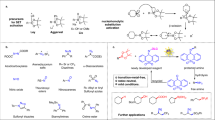

The pervasive prevalence of C − N bonds in natural products, pharmaceuticals and functional materials1,2,3 has made their efficient construction a longstanding objective in both academia and industry4,5,6. Over 80% of FDA-approved small-molecule drugs contain at least one nitrogen atom, with approximately 37% of drug candidates featuring (hetero)aromatic amines7, while C − N installation reactions account for 18% of transformations executed at the drug discovery stage8. With the rise of the “escape from flatland” concept9, there has been a significant shift in research focus towards C(sp3)-enriched N-containing functional molecules to improve the physicochemical and pharmacokinetic properties of target compounds7,10,11. Traditionally, synthetic route to C(sp3)−N linkages have mainly relied on classical methods, such as reductive amination12, nucleophilic displacement13,14,15, and olefin hydroamination16. However, these approaches are constrained by inherent limitations, for instance, assembling C − N bonds on secondary and tertiary sp3 carbon centers through SN2 substitution with unactivated alkyl halides is virtually impossible due to the increased steric hindrance17. Additionally, reductive aminations of ketones are primarily limited to reactions with alkylamines and are not feasible for other valuable N-nucleophiles such as azoles, amides, and carbamates (Fig. 1A).

A General strategies and the scarcity via Chan-Lam Coupling for assembly of C(sp3)–N bonds. B The challenging in the conventional two-electron boron-to-copper transmetalation. C Our design: Overcoming boron-to-copper transmetalation by harnessing the radical reactivity of alkylboronic pinacol esters. PC, photocatalyst; XAT, halogen-atom transfer; HAT, hydrogen-atom transfer; SET, single electron transfer; Nu, Nucleophile.

Chan-Lam coupling (CLC) has been widely applied in the chemical synthesis of C(sp2)−N architectures6,18. It can be carried out under mild conditions with excellent functional group compatibility. However, the efficient construction of C(sp3)−N bonds through this method remains a longstanding unmet challenge19. Mechanistically, this limitation may primarily arise from the high energy barrier in the boron-to-copper transmetalation due to the low reactivity of alkyl organoborons, resulting in a slower reaction rate. As a result, it typically requires the use of superstoichiometric copper salts and forcing conditions (strong bases and high temperatures)6. Nevertheless, early successful examples of CLC have still been mainly limited to cyclopropyl20,21,22,23 and methyl organoborons24,25, with recent reports involving unactivated primary and benzylic organoborons26,27,28,29,30. Furthermore, the poor efficiency with unactivated secondary organoborons and the limited range of N-coupling partners hinder the application of this promising method in accessing a wider chemical space for C(sp3)−N bonds (Fig. 1B)19. Alternative aminations of organoboron compounds have also been achieved under transition-metal-free conditions via a 1,2-metalate rearrangement of a boron ‘ate’ complex mediated by aminating reagent31,32. Given the bench stability, low toxicity, and broad synthetic accessibility of alkylboronic pinacol esters (APEs) compared to other organoboron compounds, there is a strong impetus to establish a general N-alkylation platform that can accommodate a wide range of N-nucleophiles and unactivated APEs to obtain structurally diverse C(sp3)−N linkages.

An attractive approach to achieve this goal is to exploit a unique strategy that circumvents the high energy barrier associated with the conventional two-electron boron-to-copper transmetalation. Over the past decade, the merger of copper catalysis with free-radical chemistry has emerged as a promising frontier for C(sp3)−N bond formation. Pioneering studies by Fu and Peters harnessed photochemistry to enable C(sp3)−N coupling of unactivated alkyl and aryl halides33,34,35, wherein photoexcitation generates highly reducing [Cu(I)−amido]* species that mediate single-electron transfer to organic halides. This novel catalytic paradigm involves the rapid capture of transient alkyl radicals by [Cu(II)−amido] complexes and promote product formation via reductive elimination from the resulting high-valent copper(III) intermediate, thereby bypassing the traditional transmetalation34,35,36,37,38,39,40,41,42,43,44,45,46,47,48,49,50. By integrating copper catalysis with photoredox catalysis, halogen-atom transfer (XAT), or hydrogen atom transfer (HAT) processes, MacMillan, Hu, Liu, Leonori, Hartwig, and König have further demonstrated that this catalytic mode can be applied to C(sp³)−N coupling reactions of carboxylic acids41,42,45, alkyl halides17,44,48,49,50, alcohols43, and simple hydrocarbons46,47 (Fig. 1C).

On the other hand, the direct oxidation of alkylboronic esters for alkyl radical generation has proven to be very challenging due to their high redox potential51. Several elegant activation methods have been developed to facilitate their photo-oxidation by the formation of tetrahedral boron ‘ate’ complexes, including trifluoroborate salts52,53, Lewis base−APE adducts54,55, and electron-rich alkylarylboronate complexes (Fig. 1C)56,57,58. Recently, a novel reductive activation strategy has unlocked the free radical reactivity of APEs via homolytic substitution at boron by aminyl radicals, facilitating C − C bond formation through metallaphotoredox-catalyzed C(sp2)−C(sp3) cross-coupling59 and photoinduced Giese alkylation60, as well as C − N bond construction using tailored N-centered radical scavengers61 and alkylamines62. However, the application of this activation mode in CLC reactions to forge C(sp3)−N bonds remains rare.

Intrigued by this mild activation approach, we envisioned combining copper catalysis with aminyl radical-mediated boron transfer to develop a general C(sp3)−N cross-coupling platform that utilizes APEs as alkylating reagents. However, a key challenge in realizing this transformation is identifying a suitable oxidant that can serve dual functions: as an oxidant for Cu(I)-to-Cu(II) oxidation and as a HAT reagent to generate the aminyl radicals required for promoting boron capture. The initial proof of concept, conducted under copper/photoredox dual catalysis with oxygen as the terminal oxidant, demonstrated low efficiency (see Supplementary Table 1 for details). The trimethylsilyl (TMS)-protected cumyl peroxide (cumOOTMS) O1, recently used by Leonori in copper-catalyzed amination and amidation of unactivated alkyl halides17,48, could efficiently oxidize Cu(I) to Cu(II), while the resulting electrophilic O-radical has shown the appropriate philicity and reactivity to undergo HAT with alkylamines and Me3N − BH3 to produce the corresponding free radicals for halide abstraction.

By leveraging O1 as the ideal bifunctional oxidant, we report here the successful implementation of this proposal for C(sp3)−N coupling with APEs. This strategy benefits from a radical deboronation step occurring outside the copper cycle and eliminating the need for additional photocatalysis, thus providing a practical and effective tool to achieve C(sp3)−N linkages across a broad range of N-nucleophiles and APEs, even in the late-stage modification of complex bioactive materials. Notably, during the preparation and submission of this manuscript, three highly relevant studies were published consecutively. Gestwicki63 and Bera64 independently reported the combination of copper or metallaphotoredox catalysis with aminyl radical-mediated boron abstraction to achieve the amination of APEs, whereas Dong65 described an enantioconvergent amidation of benzylic boronic pinacol esters using a similar strategy.

Results

Reaction design and optimization

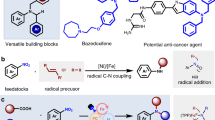

The plausible mechanism for this aminyl radical-Cu-mediated amination is outlined in Fig. 2. First, deprotonation of carbazole by a base and coordination should generate [Cu(I)−amido] complex i. At this stage, complex i is expected to undergo a favorable single-electron transfer (SET) with a stoichiometric oxidant O1, simultaneously producing the [Cu(II)–amido] species ii and a strongly electrophilic cumylO• radical iii17. Next, a polarity-matched HAT between radical iii and amine A1 should deliver the key aminyl radical iv66,67. This process is facilitated by the difference in bond dissociation energy (BDEO-H = 104.7 ± 0.2 kcal mol−1; BDEN-H = 92.5 ± 1.5 kcal mol-1)68. The favorable interaction of the aminyl radical with the unoccupied p-orbital of the Bpin moiety leads to the rapid homolytic cleavage of the C − B bond, thereby releasing the alkyl radical vi59,60. Finally, interception of this radical by complex ii should generate a putative [alkyl-Cu(III)–amido] intermediate vii, which could undergo facile reductive elimination to produce the C(sp3)−N coupled product 3 and regenerate catalytically active copper(I) species i. However, several key challenges in implementing this proposed transformation cannot be overlooked: (i) The HAT between cumylO• radical iii and A1 should selectively abstract the hydrogen from the N atom, rather than at C − H bonds α to O or N position (BDEC-H = 92.0 ± 2 kcal mol-1)68. However, this process may become elusive due to the proximity of bond dissociation energies67; (ii) The competitive reaction of Cu(I) species and APE with the aminyl radical may lead to unproductive pathway to form significant by-product.

The proposed reaction pathway begins with the base-assisted azole 1 coordination to form the [Cu(I)-amido] complex i. Following a sequence of single-electron transfer (SET) and hydrogen atom transfer (HAT), the aminyl radical iv is generated, which then undergoes homolytic substitution at the boron atom to produce the alkyl radical vi. The radical vi is subsequently captured by the [Cu(II)-amido] species ii to furnish the key [alkyl-Cu(III)-amido] intermediate vii, which, upon reductive elimination, releases the C(sp3)-N coupled product 3 and regenerates the copper(I) species i.

With this mechanistic picture in mind, we began our studies by examining the coupling between azole 1 and APE 2. After screening of reaction conditions (Table 1), we identified the optimal conditions for this C(sp3)−N coupling reaction using Cu(CH3CN)4PF6 as the catalyst, BTMG (2-tert-butyl-1,1,3,3-tetramethylguanidine) as the base, O1 as the oxidant and A1 as the radical transfer reagent in CH3CN solvent at room temperature (~30 °C). This standard method provided the desired product 3 in 85% yield (Table 1, entry 1). Variations to the standard conditions, including changes in oxidants, amine additives, copper salts, solvents, and base did not result in better outcomes (Table 1). Screening of oxidants revealed that silicon-protected cumyl hydroperoxide O1 and O2 were excellent oxidants for this transformation, while the parent cumyl hydroperoxide O3 proved to be much less effective, affording product 3 in 32% yield. Other oxidants O3-5 were nearly ineffective in this reaction, despite their superior capacity to oxidize Cu(I)27. Various amines tested in this reaction showed that A1 exhibited best performance. Cyclic secondary amines A2 and A3 gave moderate yields, while primary amine A4 and acyclic secondary amine A6 were inefficient as radical transfer reagents. Notably, the reaction employing a cyclic tertiary amine A5 lacking a free N-H didn’t work, underscoring the necessity of aminyl radical formation for boron abstraction. Control experiments demonstrated that copper salt, oxidant, and amine were essential for this transformation (Table 1 entries 7-9). However, product 3 was still obtained, albeit with a lower yield, in the absence of BTMG, possibly because amine A1 acted as an inefficient base (Table 1 entries 10-11).

Substrate Scope

With the optimized reaction protocol in hand (in some cases, slightly modified conditions were applied to achieve improved results), we began to evaluate the versatility of the deboronative C(sp3)−N cross-coupling reaction with respect to N-coupling partners (Fig. 3). We successfully applied this protocol for N-alkylation of 18 classes of medicinally relevant N-nucleophiles with unactivated secondary APEs. A broad array of N-heteroaromatics, including indazole (3–8), aza-indazole (9), aza-carbazole (10–13), carbazole (14–16), indole (17–24), aza-indole (25–31), deazapurine (32), pyrazole (33) and pyrrole (34), were smoothly coupled with 2 or 2b, delivering the corresponding N-alkylated products in good to excellent efficiency. Excellent regioselectivity for N1 alkylation was observed in the diazole heterocycle substrates (3–8, 9, 32), which can be attributed to the steric preference of heterocycles to coordinate with the copper center at the less hindered position. However, imidazole was not a suitable substrate. Arylamines and aminopyridines, motifs frequently encountered in drug development, could be efficiently engaged in this transformation, regardless of their steric hindrance or electronic properties (35–38, 39–41). In addition, a selection of challenging N-nucleophiles, including aryl and alkyl amides (42-46), sulfonamides (47–49), and oxindole (50), were well-tolerated in this protocol. Moreover, ammonia surrogates, such as benzyl carbamate (51) and benzophenone imine (52), were also viable substrates to yield products that could be easily deprotected to afford the corresponding primary amines. Alkylamine (53) was less efficient in this reaction due to competing N-alkylation of morpholine. In addition to the broad applicability of substrates, various functional groups, such as carbonyls (7, 23, 38), esters (8, 22, 46), nitriles (15), and Boc-protected amine (24), were well-tolerated. Remarkably, the synthetically valuable aryl halides (chloride: 3, 17, 20, 26, 32, 40, 43, 44, 49; bromide: 4, 14, 18, 25, 27, 28, 31, 35, 47; iodide: 5, 16, 19) remained unaffected, providing ample synthetic opportunities for further manipulation via classical cross-coupling reactions.

aConditions: N-nucleophile (0.2 mmol, 1.0 equiv), 2 or 2b (0.3 mmol, 1.5 equiv), Cu(MeCN)4PF6 (15 mol%), oxidant O1 (3.0 equiv), amine A1 (1.5 equiv) and BTMG (1.5 equiv) in MeCN (0.1 M), ambient temperature for 3-6 h. bConditions: N-nucleophile (0.2 mmol, 1.0 equiv), 2 or 2b (0.3 mmol, 1.5 equiv), CuI (15 mol%), oxidant O2 (3.0 equiv), amine A1 (1.5 equiv) and BTMG (1.5 equiv) in MeCN (0.1 M), ambient temperature for 6 h. cusing Cu(OAc)2 instead of CuI as catalyst. dusing dioxane instead of MeCN. ewith d(OMe)-Phen (20 mol%) as ligand. fwith 2-((2,6-dimethoxyphenyl)amino)−2-oxoacetic acid (20 mol%) as ligand. g3.0 equiv of 2 was used. Yields denote isolated yields.

Testing the applicability of this protocol with various unactivated APEs is crucial, given the severe limitations of substrate scope in existing CLC reactions19. Having established the generality of the nucleophilic partners, we shifted our attention to exploring the scope of APEs (Fig. 4). Primary alkylboronic ester (54) could be utilized in this transformation; however, they are not the focus of our investigation, as such N-alkylated products can be obtained through classical SN2 reactions with primary alkyl halides. To our satisfactory, a range of cyclic and acyclic secondary APEs (55–72) with diverse functional groups were successfully converted into the corresponding N-alkylated products in good yields. Substrates bearing rings ranging from three to seven numbers (55–59), as well as bicyclic (60) and heterocyclic (61–65) motifs, could smoothly couple with indazole. Spirocyclic fragments were also incorporated into this N-alkylation, yielding the corresponding products (66–67) that were previously difficult to obtain via nucleophilic substitution. β-Keto boronic esters were easily converted into products (68–69) featuring a versatile handle for further manipulation. Moreover, a set of unactivated tertiary APEs were also viable substrates in this transformation, affording N-tertiary alkyl derivatives in synthetically useful yields (73-75). Notably, the reaction was compatible with cyclic alkenylboronic esters (76-79), further highlighting the broad applicability of the protocol.

aConditions: N-nucleophile (0.2 mmol, 1.0 equiv), alkylboronic pinacol esters (0.3 mmol, 1.5 equiv), Cu(MeCN)4PF6 (15 mol%), oxidant O1 (3.0 equiv), amine A1 (1.5 equiv) and BTMG (1.5 equiv) in MeCN (0.1 M), ambient temperature for 3-6 h. bConditions: N-nucleophile (0.2 mmol, 1.0 equiv), organoboronic pinacol esters (0.3 mmol, 1.5 equiv), CuI (15 mol%), oxidant O2 (3.0 equiv), amine A1 (1.5 equiv) and BTMG (1.5 equiv) in MeCN (0.1 M), ambient temperature for 6 h. c2.0 equiv of alkylboronic pinacol esters was used. Yields denote isolated yields.

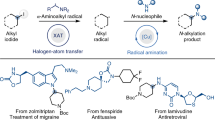

Synthetic utilities

To further illustrate the synthetic utility of this method (Fig. 5), we carried out late-stage N-alkylation on several complex bioactive molecules and pharmaceuticals, affording the desired products (80–84) in good yields (Fig. 5A). In addition, the model reaction could be easily scaled up to a gram-scale, yielding 0.94 g of product 3 with an 80% yield (Fig. 5B). The method was also successfully applied to the synthesis of intermediates of two drug relevant molecules (85, 86), demonstrating its potential utility in medicinal chemistry (Fig. 5C). Furthermore, regioselective monoalkylation for substrates with multiple nucleophilic sites has long been a challenge. We were pleased to find that this C − N coupling platform could be applied to the sequential and selective N-alkylation (87, 88) at two discrete nitrogen positions within the same molecule (Fig. 5D). This excellent regioselectivity is likely governed by N − H acidity, with the more acidic proton of the indazole preferentially undergoing deprotonation.

Mechanistic studies

As proposed in Fig. 2, this C(sp3)−N coupling involves a Cu(I)/Cu(II)/Cu(III) cycle. Initially, we sought to use UV–vis absorption spectroscopy to gather supporting information on specific steps of the process (Fig. 6a). Treatment of a colorless solution of Cu(MeCN)4PF6 with 1 in the presence of BTMG resulted in a pale yellow solution, suggesting the possible formation of [Cu(I)-amido] i. The addition of amine A1 and 2 to this solution did not lead to any color change as demonstrated by the UV–vis spectrum. In contrast, in a parallel experiment, addition of O1 resulted in an immediate color change to dark green, which corresponded to a red shift in the UV–vis spectrum, supporting the formation of [Cu(II)-amido] ii17. Additionally, stoichiometric reaction with Cu(I) salt further validated the plausibility of this proposed catalytic sequence, as evidenced by the isolation of the expected product 3 in 45% yield. However, repeating the reaction with stoichiometric Cu(II) salt did not yield product 3 (Fig. 6b). We infer that the electrophilic O radical iii is generated through one-electron oxidation of Cu(I) by O1, rather than oxidation of Cu(II), and its formation is essential for driving the subsequent steps. EPR experiments revealed the formation of both O and N-centered radicals in this reaction. Specifically, in the absence of amine A1, a strong radical signal was detected, corresponding to the trapping of an oxygen-centered radical by 5,5-dimethyl-1-pyrroline N-oxide (DMPO). In contrast, when amine A1 was present, a distinctly different radical signal was observed, which is most likely attributed to the trapping of an aminyl radical, possibly with contribution from trapped oxygen radical as well (Fig. 6e). 11B NMR study revealed no interaction between 2 and amine A1, ruling out the possibility of amine acting as a Lewis base to activate APEs and subsequently enabling a direct oxidation of the resulting ate-complex by O1 (Fig. 6c). Moreover, the successful isolation of the TEMPO adduct 89 with a high yield, formed by trapping the alkyl radical by TEMPO, substantiated the involvement of an alkyl radical intermediate (Fig. 6d).

a UV–vis absorption spectroscopy studies support the specific steps in the proposed Cu cycle. b Probing reaction with stoichiometric Cu salts. c 11B NMR spectroscopy studies towards the interaction between 2, amine A1, and oxidant O1. d Radical trapping experiment. e EPR experiments to probe O and N-centered radical.

Discussion

By leveraging an aminyl radical-mediated boron transfer strategy, we have addressed the long-standing limitation of APEs in Chan-Lam coupling, thereby establishing a versatile N-alkylation platform that accommodates a broad spectrum of N-nucleophiles and various APEs. Given the wide availability of both coupling partners, and the pivotal role of C(sp3)−N linkages in bioactive molecules, this work not only expands the synthetic toolkit for C(sp3)−N assembly from readily accessible starting materials but also holds potential value for the medicinal chemistry community.

Methods

General procedure for the Chan-Lam amination with alkylboronic esters (conditions A). To an oven-dried 5 mL vial equipped with a magnetic stir bar was charged with N-nucleophile (0.20 mmol, 1.0 equiv, if solid), then the vial was transferred to a N2-filled glovebox. Cu(MeCN)4PF6 (11.2 mg, 0.03 mmol, 15 mol%) was added to the vial, and the mixture was dissolved in 2.0 mL dry MeCN. The vial was tightly capped and removed from the glovebox. The alkyl pinacol boronate (0.3 mmol, 1.5 equiv, if liquid) and amine A1 (26 mg, 0.3 mmol, 1.5 equiv), BTMG (51.4 mg, 0.3 mmol, 1.5 equiv) were sequentially added by a micro-syringe. Finally, cumOOTMS O1 (135 mg, 0.6 mmol, 3.0 equiv) was added dropwise to the solution. The mixture was allowed to stir at 30 °C for 3–6 h (monitored by TLC). After completion, the reaction was quenched by H2O (5 mL), extracted with EtOAc (3 × 5 mL). The combined organic layers were concentrated under reduced pressure. The residue was purified by flash chromatography to give the pure product.

General procedure for the Chan-Lam amination with alkylboronic esters (conditions B). To an oven-dried 5 mL vial equipped with a magnetic stir bar was charged with N-nucleophile (0.20 mmol, 1.0 equiv, if solid), then the vial was transferred to a N2-filled glovebox. CuI (5.8 mg, 0.03 mmol, 15 mol%) were added to the vial, and the mixture was dissolved in 2.0 mL dry MeCN. The vial was tightly capped and removed from the glovebox. The alkyl pinacol boronate (0.3 mmol, 1.5 equiv, if liquid) and amine A1 (26 mg, 0.3 mmol, 1.5 equiv), BTMG (51.4 mg, 0.3 mmol, 1.5 equiv) were sequentially added by a micro-syringe. Finally, cumOOTES O2 (160 mg, 0.6 mmol, 3.0 equiv) was added dropwise to the solution. The mixture was allowed to stir at 30 °C for 6 hours (monitored by TLC). After completion, the reaction was quenched by H2O (5 mL), extracted with EtOAc (3 × 5 mL). The combined organic layers were concentrated under reduced pressure. The residue was purified by flash chromatography to give the pure product.

Data availability

The authors declare that the data supporting the findings of this study are available within the paper and its supplementary information files. All raw data are available from the corresponding author upon request.

References

Ricci, A., Amino Group Chemistry: From Synthesis to the Life Sciences; (Wiley-VCH: Weinheim, Germany, 2008).

Knölker, H.-J., The Alkaloids: Chemistry and Biology Vol. 70, (Elsevier, San Diego, 2011).

Ćirić-Marjanović, G. Recent advances in polyaniline research: polymerization mechanisms, structural aspects, properties and applications. Synth. Met. 177, 1–47 (2013).

Ruiz-Castillo, P. & Buchwald, S. L. Applications of palladium-catalyzed C–N cross-coupling reactions. Chem. Rev. 116, 12564–12649 (2016).

Bhunia, S., Pawar, G. G., Kumar, S. V., Jiang, Y. & Ma, D. Selected copper-based reactions for C-N, C-O, C-S, and C-C bond formation. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 56, 16136–16179 (2017).

West, M. J., Fyfe, J. W. B., Vantourout, J. C. & Watson, A. J. B. Mechanistic development and recent applications of the Chan-Lam amination. Chem. Rev. 119, 12491–12523 (2019).

Vitaku, E., Smith, D. T. & Njardarson, J. T. Analysis of the structural diversity, substitution patterns, and frequency of nitrogen heterocycles among U.S. FDA approved pharmaceuticals. J. Med. Chem. 57, 10257–10274 (2014).

Roughley, S. D. & Jordan, A. M. The medicinal chemist’s toolbox: an analysis of reactions used in the pursuit of drug candidates. J. Med. Chem. 54, 3451–3479 (2011).

Lovering, F., Bikker, J. & Humblet, C. J. Escape from flatland: increasing saturation as an approach to improving clinical success. J. Med. Chem. 52, 6752–6756 (2009).

Brown, D. G. & Boström, J. Analysis of past and present synthetic methodologies on medicinal chemistry: where have all the new reactions gone?. J. Med. Chem. 59, 4443–4458 (2016).

Trowbridge, A., Walton, S. M. & Gaunt, M. J. New strategies for the transition-metal catalyzed synthesis of aliphatic amines. Chem. Rev. 120, 2613–2692 (2020).

Afanasyev, O. I., Kuchuk, E., Usanov, D. L. & Chusov, D. Reductive amination in the synthesis of pharmaceuticals. Chem. Rev. 119, 11857–11911 (2019).

Salvatore, R. N., Yoon, C. H. & Jung, K. W. Synthesis of secondary amines. Tetrahedron 57, 7785–7811 (2001).

Swamy, K. C. K., Kumar, N. N. B., Balaraman, E. & Kumar, K. V. P. P. Mitsunobu and related reactions: advances and applications. Chem. Rev. 109, 2551–2651 (2009).

Fletcher, S. The Mitsunobu reaction in the 21st century. Org. Chem. Front. 2, 739–752 (2015).

Huang, L., Arndt, M., Gooßen, K., Heydt, H. & Gooßen, L. J. Late transition metal-catalyzed hydroamination and hydroamidation. Chem. Rev. 115, 2596–2697 (2015).

Górski, B., Barthelemy, A.-L., Douglas, J. J., Juliá, F. & Leonori, D. Copper-catalysed amination of alkyl iodides enabled by halogen-atom transfer. Nat. Catal. 4, 623–630 (2021).

Chen, J.-Q., Li, J.-H. & Dong, Z.-B. A review on the latest progress of Chan-Lam coupling reaction. Adv. Synth. Catal. 362, 3311–3331 (2020).

Almutairi, N. E. A., Elsharif, N. A., Kamranifard, T., Wang, J. & Partridge, B. M. Amination of alkylboronic esters. Eur. J. Org. Chem. 28, e202401158 (2025).

Tsuritani, T. et al. N-cyclopropylation of indoles and cyclic amides with copper(II) reagent. Org. Lett. 10, 1653–1655 (2008).

Bénard, S., Neuville, L. & Zhu, J. Copper-promoted N-cyclopropylation of anilines and amines by cyclopropylboronic acid. Chem. Commun. 46, 3393–3395 (2010).

Bénard, S., Neuville, L. & Zhu, J. Copper-mediated N-cyclopropylation of azoles, amides, and sulfonamides by cyclopropylboronic acid. J. Org. Chem. 73, 6441–6444 (2008).

Racine, E., Monnier, F., Vors, J.-P. & Taillefer, M. Direct N-cyclopropylation of secondary acyclic amides promoted by copper. Chem. Commun. 49, 7412–7414 (2013).

González, I., Mosquera, C., Guerrero, R., Rodríguez, J. & Cruces, J. Selective monomethylation of anilines by Cu(OAc)2-promoted cross-coupling with MeB(OH)2. Org. Lett. 11, 1677–1680 (2009).

Pudlo, M. et al. Quinolone-benzylpiperidine derivatives as novel acetylcholinesterase inhibitor and antioxidant hybrids for Alzheimer disease. Bioorg. Med. Chem. 22, 2496–2507 (2014).

Rossi, S. A., Shimkin, K. W., Xu, Q., Mori-Quiroz, L. M. & Watson, D. A. Selective formation of secondary amides via the copper-catalyzed cross-coupling of alkylboronic acids with primary amides. Org. Lett. 15, 2314–2317 (2013).

Mori-Quiroz, L. M., Shimkin, K. W., Rezazadeh, S., Kozlowski, R. A. & Watson, D. A. Copper-Catalyzed Amidation of Primary and Secondary Alkyl Boronic Esters. Chem. Eur. J. 22, 15654–15658 (2016).

Sueki, S. & Kuninobu, Y. Copper-catalyzed N- and O-alkylation of amines and phenols using alkylborane reagents. Org. Lett. 15, 1544–1547 (2013).

Kim, D. S. & Lee, H. G. Formation of the tertiary sulfonamide C(sp3)-N bond using alkyl boronic ester via intramolecular and intermolecular copper-catalyzed oxidative cross-coupling. J. Org. Chem. 86, 17380–17394 (2021).

Grayson, J. D., Dennis, F. M., Robertson, C. C. & Partridge, B. M. Chan-Lam amination of secondary and tertiary benzylic boronic esters. J. Org. Chem. 86, 9883–9897 (2021).

Mlynarski, S. N., Karns, A. S. & Morken, J. P. Direct stereospecific amination of alkyl and aryl pinacol boronates. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 134, 16449–16451 (2012).

Liu, X. et al. Aminoazanium of DABCO: An Amination Reagent for Alkyl and Aryl Pinacol Boronates. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 59, 2745–2749 (2020).

Creutz, S. E., Lotito, K. J., Fu, G. C. & Peters, J. C. Photoinduced Ullmann C-N coupling: demonstrating the viability of a radical pathway. Science 338, 647–651 (2012).

Bissember, A. C., Lundgren, R. J., Creutz, S. E., Peters, J. C. & Fu, G. C. Transition-metal-catalyzed alkylations of amines with alkyl halides: photoinduced, copper-catalyzed couplings of carbazoles. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 52, 5129–5133 (2013).

Do, H.-Q., Bachman, S., Bissember, A. C., Peters, J. C. & Fu, G. C. Photoinduced, copper-catalyzed alkylation of amides with unactivated secondary alkyl halides at room temperature. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 136, 2162–2167 (2014).

Kainz, Q. M. et al. Asymmetric copper-catalyzed C-N cross-couplings induced by visible light. Science 351, 681–684 (2016).

Matier, C. D., Schwaben, J., Peters, J. C. & Fu, G. C. Copper-catalyzed alkylation of aliphatic amines induced by visible light. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 139, 17707–17710 (2017).

Ahn, J. M., Peters, J. C. & Fu, G. C. Design of a photoredox catalyst that enables the direct synthesis of carbamate-protected primary amines via photoinduced, copper-catalyzed N-alkylation reactions of unactivated secondary halides. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 139, 18101–18106 (2017).

Chen, C., Peters, J. C. & Fu, G. C. Photoinduced copper-catalysed asymmetric amidation via ligand cooperativity. Nature 596, 250–256 (2021).

Cho, H., Tong, X., Zuccarello, G., Anderson, R. L. & Fu, G. C. Synthesis of tertiary alkyl amines via photoinduced copper-catalysed nucleophilic substitution. Nat. Chem. 17, 271–278 (2025).

Mao, R., Frey, A., Balon, J. & Hu, X. Decarboxylative C(sp3)–N cross-coupling via synergetic photoredox and copper catalysis. Nat. Catal. 1, 120–126 (2018).

Liang, Y., Zhang, X. & MacMillan, D. W. C. Decarboxylative sp3 C-N coupling via dual copper and photoredox catalysis. Nature 559, 83–88 (2018).

Carson, W. P. et al. Free-radical deoxygenative amination of alcohols via copper metallaphotoredox catalysis. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 146, 15681–15687 (2024).

Dow, N. W., Cabré, A. & MacMillan, D. W. C. A general N-alkylation platform via copper metallaphotoredox and silyl radical activation of alkyl halides. Chem 7, 1827–1842 (2021).

Nguyen, V. T. et al. Visible-light-enabled direct decarboxylative N-alkylation. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 59, 7921–7927 (2020).

Tran, B. L., Li, B., Driess, M. & Hartwig, J. F. Copper-catalyzed intermolecular amidation and imidation of unactivated alkanes. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 136, 2555–2563 (2014).

Zheng, Y., Narobe, R., Donabauer, K., Yakubov, S. & König, B. Copper(II)-photocatalyzed N–H alkylation with alkanes. ACS Catal. 10, 8582–8589 (2020).

Zhang, Z., Poletti, L. & Leonori, D. A radical strategy for the alkylation of amides with alkyl halides by merging boryl radical-mediated halogen-atom transfer and copper catalysis. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 146, 22424–22430 (2024).

Chen, J.-J. et al. Enantioconvergent Cu-catalysed N-alkylation of aliphatic amines. Nature 618, 294–300 (2023).

Zhang, Y.-F. et al. Asymmetric amination of alkyl radicals with two minimally different alkyl substituents. Science 388, 283–291 (2025).

Pillitteri, S., Ranjan, P., Van der Eycken, E. V. & Sharma, U. K. Uncovering the Potential of Boronic Acid and Derivatives as Radical Source in Photo(electro)chemical Reactions. Adv. Synth. Catal. 364, 1643–1665 (2022).

Tellis, J. C., Primer, D. N. & Molander, G. A. Single-electron transmetalation in organoboron cross-coupling by photoredox/nickel dual catalysis. Science 345, 433–436 (2014).

Duret, G., Quinlan, R., Bisseret, P. & Blanchard, N. Boron chemistry in a new light. Chem. Sci. 6, 5366–5382 (2015).

Lima, F. et al. Visible light activation of boronic esters enables efficient photoredox C(sp2)-C(sp3) cross-couplings in flow. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 55, 14085–14089 (2016).

Lima, F. et al. Lewis base catalysis approach for the photoredox activation of boronic acids and esters. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 56, 15136–15140 (2017).

Shu, C., Noble, A. & Aggarwal, V. K. Photoredox-catalyzed cyclobutane synthesis by a deboronative radical addition-polar cyclization cascade. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 58, 3870–3874 (2019).

Kaiser, D., Noble, A., Fasano, V. & Aggarwal, V. K. 1,2-Boron shifts of β-boryl radicals generated from bis-boronic esters using photoredox catalysis. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 141, 14104–14109 (2019).

Clausen, F., Kischkewitz, M., Bergander, K. & Studer, A. Catalytic protodeboronation of pinacol boronic esters: formal anti-Markovnikov hydromethylation of alkenes. Chem. Sci. 10, 6210–6214 (2019).

Speckmeier, E. & Maier, T. C. ART─an amino radical transfer strategy for C(sp2)-C(sp3) coupling reactions, enabled by dual photo/nickel catalysis. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 144, 9997–10005 (2022).

Wang, Z., Wierich, N., Zhang, J., Daniliuc, C. G. & Studer, A. Alkyl radical generation from alkylboronic pinacol esters through substitution with aminyl radicals. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 145, 8770–8775 (2023).

Zhu, C., Lin, J., Bao, X. & Wu, J. Development of N-centered radical scavengers that enables photoredox-catalyzed transition-metal-free radical amination of alkyl pinacol boronates. Nat. Commun. 16, 3225 (2025).

Dennis, F. M. et al. Cu-catalyzed coupling of aliphatic amines with alkylboronic esters. Chem. Eur. J. 30, e202303636 (2024).

Sang, R. & Gestwicki, J. E. Radical strategy to the boron-to-copper transmetalation problem: N-alkylation with alkylboronic esters. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 147, 23259–23269 (2025).

Shil, S., Patra, B. P., Begam, T. & Bera, S. C(sp3)–N coupling of nonactivated alkyl boronic pinacol esters by the merger of amino radical transfer and copper catalysis. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 147, 26486–26495 (2025).

Vu, J. et al. Enantioconvergent Chan–Lam coupling: synthesis of chiral benzylic amides via Cu-catalyzed deborylative amidation. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 147, 25527–25535 (2025).

Salamone, M., DiLabio, G. A. & Bietti, M. Hydrogen atom abstraction selectivity in the reactions of alkylamines with the benzyloxyl and cumyloxyl radicals. The importance of structure and of substrate radical hydrogen bonding. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 133, 16625–16634 (2011).

Salamone, M. et al. Bimodal Evans-polanyi relationships in hydrogen atom transfer from C(sp3)-H Bonds to the Cumyloxyl Radical. A Combined Time-Resolved Kinetic and Computational Study. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 143, 11759–11776 (2021).

Luo, Y.-R., Comprehensive Handbook of Chemical Bond Energies. (CRC Press, 2007).

Acknowledgements

We are grateful for the financial support provided by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (22361026, T. Y.), High-Level Talent Programme Foundation of Jiangxi Province (JXSQ2023101070, T. Y.).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

H.X., P.C., W.X., and T.Y. developed the catalytic method. T.Y. directed the investigations. H.X., P.C., and W.X. performed the experiments and analyzed the data. T.Y. wrote the manuscript with revisions provided by the other authors.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Peer review

Peer review information

Nature Communications thanks Jeyakumar Kandasamy and the other anonymous reviewer(s) for their contribution to the peer review of this work. A peer review file is available.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Xiao, H., Cao, P., Xiong, W. et al. Overcoming limitations in Chan-Lam amination with alkylboronic esters via aminyl radical substitution. Nat Commun 16, 9121 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-025-64155-x

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-025-64155-x