Abstract

Selective CH4-to-C2 oxygenates conversion under mild conditions represents a frontier challenge in catalysis science with promising commercial implications. Herein, we report the successful and controlled construction of densely distributed O2-bridged Fe diatomic (Fe1-O2-Fe1) interfaces in carbon nitride aerogel-supported Fe dual-atom catalysts (Fe-DAC/g-C3N4) for selective methane oxidation to acetic acid (CH3COOH) in aqueous solution under mild conditions. Experimental studies reveal that the Fe1-O2-Fe1 atomic interfaces with tailored coordination environments and precisely modulated Fe-Fe distance (2.92 ± 0.05 Å) and oxygen-bridged coordination environment synergistically promote the activation and cleavage of C-H bond to form methyl radicals (•CH3), carboxyl intermediates (•COOH), followed by selective C-C coupling via a radical recombination pathway. This concerted mechanism achieves unprecedented performance with near 100% selectivity and a remarkable CH3COOH production rate of 0.79 mmol gcat−1 h−1 under ambient conditions. Notably, industrially relevant pressures (1.5 MPa CH4) elevate the production rate to 1.67 mmol gcat−1 h−1 while maintaining >96% selectivity.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The selective conversion of methane (CH4)—a chemically inert yet abundant component of natural gas and a potent greenhouse agent—into value-added multicarbon products under mild conditions is an ideal strategy to promote sustainable chemical synthesis and climate change mitigation. Among potential targets, acetic acid (CH3COOH) emerges as a strategic platform molecule for various industrial products (e.g., plastics, photographic films and textiles) and intermediates in numerous chemical processes1,2,3,4,5,6,7,8,9,10,11,12,13, accounting for about 80% of global vinyl acetate monomer production (key precursor to adhesives/coatings), over 60% of cellulose acetate manufacturing (essential for textiles/photographic films), and various important agrochemical intermediates. This industrial ubiquity contrasts with the absence of scalable catalytic routes for its direct synthesis from CH4 under mild conditions.

Efficient catalysts that can activate methane and promote the following C–C coupling reaction are essential. Previous approaches to CH4 activation predominantly rely on homogeneous metal complexes (e.g., Rh and Pd) and strongly acidic solutions, and suffer from low reaction selectivity, corrosive environments accelerating the degradation of reactors, and energy-intensive operation conditions14. Single-atom catalysts have recently shown promise for CH4 activation compared to traditional catalysts; however, their dependency on exogenous carbon donors (e.g., CO) to enable C─C coupling introduces unsustainable process complexity15,16,17,18,19,20,21,22,23,24. Despite extensive research, no existing system concurrently addresses three benchmarks for industrial viability, including the direct CH4-to-C2 conversion without auxiliary carbon inputs, aqueous-phase operation under mild conditions (T < 100 °C, P < 3 MPa), and over 95% selectivity toward a single oxygenate25. This highlights the need for catalysts that can effectively facilitate both methane activation and C–C coupling.

Recent advances in nanoconfined catalysis suggest spatial confinement could synergize reactant enrichment and transition-state stabilization26,27,28,29. For instance, molecular catalysts with hydrophobic cavities substituted with formyl/anthracenyl groups and Fe (II) species can hydroxylate CH4 to methanol in aqueous media via a catch-and-release mechanism24, while hydrophilic Fe (III)@ACN hydrogel membranes can photocatalytically generate matched concentrations of •OH and •CH3 at the three-phase interface, leading to the production of methanol and ethanol6,30,31,32,33,34. However, due to the lack of precise control over active sites, the activity for methane activation and selectivity for C–C coupling still require significant improvement. In particular, the direct oxidation of CH4 to C2+ products in the absence of other carbon sources has rarely been observed. However, these systems exhibit two critical shortcomings, including the low solubility of CH4 in water and its small diffusion coefficient, which impedes the accumulation and coupling of intermediates such as •CH3 on the catalyst surface35,36,37; and the uncontrolled radical recombination pathways38,39. Fundamentally, the absence of atomic-level control over multinuclear active sites impedes precise steering of sequential C─H activation and C–C coupling—a prerequisite for selective C2 oxygenate formation.

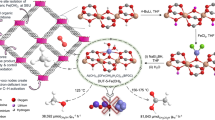

Here, the coordination tailored Fe1-O2-Fe1 atomic interface was fabricated by precisely incorporating Fe1-O2-Fe1 on C3N4 to form Fe-DAC/g-C3N4 with a strong affinity for CH4 through impregnation, freeze-drying, and pyrolysis. This catalyst achieves nearly 100% selectivity for the direct oxidation of CH4 to acetic acid without additional carbon sources. This “capture-coupling” mechanism can be understood as follows: the high CH4 affinity of the C3N4 aerogel cavity enhances the local concentration of CH4 around the active sites, while the distinctive Fe1-O2-Fe1 centers facilitate the coupling of CH4 oxidation intermediates (•CH3 and •COOH), as corroborated by comprehensive characterization and theoretical calculations.

Results

Fabrication and characterization of Fe-DAC/g-C3N4

By developing a controlled fabrication strategy for carbon nitride aerogel-supported Fe dual-atom catalysts (Fe-DAC/g-C3N4), we successfully constructed densely distributed Fe-DAC/g-C3N4 with tailored coordination geometry (Fig. 1a). These unique configurations exhibit exceptional methane affinity, effectively concentrating CH4 molecules around active sites followed by efficent CH4 activity, heterolytic C–H cleavage, and C–C coupling (Fig. 1b). In brief, the Fe-DAC/g-C3N4 was constructed through a controlled two-step strategy, involving the first self-assembly Fe2(CO)9/g-C3N4 via an adsorption-freeze-drying procedure (Fig. 2a and Supplementary Figs. S1 and 2). The anchoring of Fe2(CO)9 at nitrogen-rich cavities of C3N4 is driven by two complementary factors: (1) electronic interaction between the lone-pair electrons of cavity nitrogen atoms in C3N4 and the d-orbitals of Fe atoms in Fe2(CO)9, facilitating initial binding; (2) Steric constraints imposed by the bulky carbonyl (CO) ligands surrounding each Fe center. Crucially, the steric guidance arises because the maximum cavity diameter in C3N4 (4.7 Å) is smaller than the van der Waals diameter of Fe2(CO)9 (5.67 Å). This forces the Fe2(CO)9 molecule to adopt a specific orientation where its CO ligands sterically “lock” against the cavity edges, preventing aggregation and ensuring monodisperse anchoring. The resulting Fe2(CO)9/g-C3N4 exhibited a porous structure (Fig. 2b–e) with multiscale pore sizes. These structures were well maintained in the aerogel after pyrolysis (Fig. 2f–i), which resulted in the lightweight (Fig. 2g) and mechanically robust (Fig. 2k–m) containing 0.521 wt% Fe (Table S1). Furthermore, Fe-DAC/g-C3N4 exhibited exceptional structural and chemical stability, retaining its porous architecture (Fig. 2b–d, f–h) and elemental composition (Fig. 2i) post-pyrolysis. The abundant nanoscale pores within the catalyst (Supplementary Fig. S3), serving as confined reactors, facilitate the occurrence of C–C coupling. The morphology and crystallinity (Supplementary Figs. S4–7) of Fe-DAC/g-C3N4 were consistent with those of C3N4, suggesting the high mechanical stability of the samples40,41. X-ray diffraction (XRD) patterns of the Fe-DAC/g-C3N4 reveal a prominent (002) peak and smaller (100) peaks of g-C3N442, while the absence of iron metal or oxide peaks indicates the highly dispersed nature of the iron species (Supplementary Fig. 6). The FTIR spectra of C3N4 and Fe-DAC/g-C3N4 display peaks corresponding to −NH stretching vibration modes at approximately 3180 cm−1, C–N heterocycles in the wavelength range of 1100–1650 cm−1, and the breathing mode of tri-s-triazine units at 810 cm−1 (Supplementary Fig. S7)43. Compared with Fe2(CO)9, Fe-DAC/g-C3N4 has no additional infrared features related to the dimeric iron complex, indicating the complete removal of organic ligands during the immobilization process.

a Design of confined Fe1-O2-Fe1 atomic interfaces. In the upper left illustration, the green, gray, and blue spheres represent Fe, C, and N atoms, respectively. The Fe atoms are connected by brown sticks, representing carbonyl ligands. b Illustration of the production process of C2 oxygenates from CH4.

a Schematic diagram of Fe-DAC/g-C3N4 synthesis. The green, red, gray, and blue spheres represent Fe, O, C, and N atoms, respectively. The Fe atoms are connected by brown sticks, representing carbonyl ligands. Low and high magnified SEM images of (b–d) Fe2(CO)9/g-C3N4 and (f–h) Fe-DAC/g-C3N4. HAADF-SEM images and corresponding EDX elemental mapping for C, N, and O distribution in (e) Fe2(CO)9/g-C3N4 and (i) Fe-DAC/g-C3N4. g Photographs of 30 mg Fe-DAC/g-C3N4 supported by soft setaria viridis. k–m Compressibility testing of Fe-DAC/g-C3N4.

The aberration-corrected high-angle annular dark field scanning transmission electron microscopy (HAADF-STEM) images (Fig. 3a–h) reveal that numerous adjacent, paired bright spots (indicated by red rectangles) distributed over the substrates, without any aggregates. The random distribution of Fe atom pairs is related to the three-dimensional structure of C3N4-gel. These paired bright spots can be contributed to the atomically dispersed Fe atoms due to higher Z contrast (M = 56 for Fe, where M refers to the atomic mass) than that of C3N4 (M = 12 or 14). Fig. 3i–k shows clear views of the local coordination environment of Fe atoms in the sample, providing evidence for the anchoring configurations of the Fe atoms on C3N4. Line profile analysis of approximately 200 pairs of these bright spots yields an average interatomic distance of 2.92 (±0.05 Å, Fig. 3l). This distance is notably greater than the 2.53 Å separation observed in the Fe2(CO)9 complex, further confirming the reconstruction of the iron dimers resulting from the removal of organic ligands during synthesis. The intensity surface maps (Fig. 3m, n) reveal the visual differentiation of the Fe dimers in Fig. 3f, g, respectively. Energy-dispersive X-ray spectroscopy (EDX, Supplementary Fig. S8) result shows the uniform distribution of elements across Fe-DAC/g-C3N4. As illustrated in Figs. 3o and S9, the determined iron-dimer structure consists of two Fe atoms bridged by two O atoms, with Fe–O bond lengths of approximately 1.99 Å and an included angle (Fe-O-Fe) of 94.7°. The Fe-Fe distance in the Fe dimers is approximately 2.93 Å.

a–h Representative HAADF-STEM images of Fe-DAC/g-C3N4, Fe dimers is marked in a red rectangle. i–k Different configurations of the Fe2 anchored on the C3N4 structure. The yellow, gray, and blue spheres represent Fe, C, and N atoms, respectively. l Statistical distribution of the Fe-Fe distance in the Fe dimers derived from the STEM images. The upper right illustration shows a schematic of the C3N4 pore size. m, n 3D intensity surface plot and intensity range shown for the dashed white regions of the image in (f, g). o Geometric parameters of the Fe1-O2-Fe1 atomic interface structure.

The normalized Fe K-edge X-ray absorption near-edge structure (XANES) spectra reveal that the absorption threshold of Fe-DAC/g-C3N4 located between FeO and Fe2O3 (Fig. 4a). Fitting analysis show that Fe atoms in Fe-DAC/g-C3N4 have an average valence state of +2.8, which is higher than Fe in Fe2(CO)9 (Fig. 4b). This is further supported by Fe 2 P X-ray photoelectron spectroscopy (XPS, Fig. S10). The wavelet transforms (WT) plot of the Fe-DAC/g-C3N4 has a pronounced intensity maximum at approximately 4.5 Å−1 (Fig. 4c), corresponding to Fe-N/O/C bonds. The density center at approximately 7.0 Å−1 corresponding to FeO suggests the formation of the Fe-O-Fe structure within the catalyst. The coordination environments of Fe species were determined by Fourier transform (FT) k3-weighted EXAFS spectral analysis and XPS analysis. As shown in Fig. 4d, the Fe-DAC/g-C3N4 shows first-shell scattering at 1.57 Å in the R space (prior to phase correction), which is close to the distances of 1.51 and 1.50 Å for FeO and Fe2O3, respectively. Based on these observations, we tentatively attribute the primary scattering pair at 1.57 Å in the R-space spectrum of Fe-DAC/g-C3N4 to Fe-N/O/C coordination. The high–resolution N 1 s XPS spectrum (Fig. 4e) of the support shows three peaks at binding energies of 398.04, 400.4, and 401.1 eV, corresponding to C-N = C, N-(C)3, and N-H, respectively44,45. Notably, an additional peak at approximately ≈399.4 eV is observed for Fe-DAC/g-C3N4, which is indicative of Fe–N bonds.

a XANES spectra for Fe-DAC/g-C3N4 with the reference materials Fe foil, FeO, Fe2(CO)9 and Fe2O3. b Relationship between Fe k-edge absorption energy (E0) and oxidation state for Fe-DAC/g-C3N4, Fe foil, FeO, Fe2(CO)9 and Fe2O3. c WT plots. d k2-weighted Fourier transform spectra derived from EXAFS results of the Fe k-edge for Fe-DAC/g-C3N4, Fe foil, FeO, Fe2(CO)9, and Fe2O3. e, f High–resolution of N 1s (e) and O 1s (f) XPS spectra of Fe-DAC/g-C3N4 and C3N4. g The EXAFS R-space fitting results of Fe-DAC/g-C3N4 spectra. h Charge-density difference of Fe-DAC/g-C3N4. The yellow and blue regions represent electron accumulation and depletion, respectively. i The PDOS of Fe 3d, O 2p, and N 2p in Fe-DAC/g-C3N4.

The high-resolution O 1s XPS spectrum (Fig. 4f) of Fe-DAC/g-C3N4 can be deconvoluted into H2O (533.6 eV), adsorbed O (533.1 eV), and Fe–O (531.6 eV)33. In contrast, Fe–O oxygen species are not detectable in C3N4. The C 1s spectra (Fig. S11) for both the catalyst and the support exhibit identical peak profiles, suggesting that Fe–C bonds are either minimal or absent in the catalyst46,47,48. These findings indicate that Fe atoms are directly anchored to Fe-DAC/g-C3N4 via Fe–N bonds and form multiatom centers through Fe–O bonds. The Fe coordination configurations in Fe-DAC/g-C3N4 were then determined by quantitative EXAFS curve fitting analysis (Fig. 4g, Supplementary Fig. S12 and Table S2). The optimized fitting results reveal that Fe atoms in Fe-DAC/g-C3N4 are coordinated with two nitrogen (N) atoms and two oxygen (O) atoms, with average bond distances of approximately 1.95 Å for Fe-N and 1.93 Å for Fe–O. Additionally, a contribution at 2.98 Å corresponding to Fe-O-Fe is observed, with an average coordination number (CN) of 1.0, which is indicative of an Fe-O2-Fe site. Charge density analysis reveals that Fe atoms are situated at the interface between regions of electron accumulation and electron depletion (Fig. 4h), with charge transfer occurring between Fe and C3N4. The corresponding electronic density of states (DOS, Fig. 4i) for Fe-DAC/g-C3N4 further elucidates the interactions between Fe atoms and N and O atoms.

The catalytic performance of Fe-DAC/g-C3N4

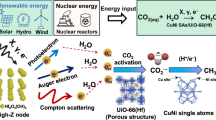

Fe-DAC/g-C3N4 demonstrates an impressive selectivity of 96.4% for the conversion of methane to acetic acid, achieving a yield of 1.67 mmol gcat−1 h−1 (Fig. 5a, b and Supplementary Fig. S13). Both C3N4 and C3N4-gel exhibited no catalytic activity towards CH4 oxidation. To demonstrate the unique benefits of diatomic sites, a direct comparison between the diatomic Fe catalyst (FeDAC) and an analogous Fe single-atom catalyst (FeSAC) under identical reaction conditions has been conducted. Compared with Fe-DAC/g-C3N4 samples, the Fe-SAC/g-C3N4 exhibits smaller reaction selectivity (only 13.1% CH3COOH) and product yielding rates (CH3OH: 0.41 mmol gcat−1 h−1; CH3OOH: 0.96 mmol gcat−1 h−1; CH3COOH :0.21 mol gcat−1 h−1; Supplementary Figs. S14 and S15). These results demonstrate the unique benefits of diatomic sites for CH4 oxidation. Acetic acid selectivity is correlated with the Fe content, with the Fe-DAC/g- C3N4 containing 0.52 wt% Fe exhibiting the optimal selectivity for acetic acid (Supplementary Figs. S16 and S17). Fe-DAC/g-C3N4 effectively suppresses overoxidation of the products, as confirmed by the absence of CO2 in the gas chromatography (GC) results (Supplementary Figs. S18–S21). The only byproduct is methanol peroxide (CH3OOH). Notably, typical byproducts such as formaldehyde and carbon monoxide, which are commonly associated with methane oxidation reactions, are absent. This suggests a new reaction pathway on Fe-DAC/g-C3N4 compared to traditional methane oxidation or CO-involved methane oxidation processes (Supplementary Fig. S22)15,16,17,18,48,49,50,51,52. To elucidate the origin of the reaction products, a control experiment employing isotopically labeled 13CH4 was performed. The 13C nuclear magnetic resonance (NMR) spectra reveal chemical shifts at 20.8 and 176.9 ppm, corresponding to 13CH3COOH (Fig. 5c). When 13CH4 and H2O2 coexisted, the 1H NMR spectra displayed two distinct peaks for CH3COOH (Supplementary Fig. S23). While there are no products detected in control experiments using pure argon, H2O2, or CH4 (Supplementary Fig. S24). These confirms that CH3COOH is derived only from the conversion of CH4, rather than from the environmental contaminants or impurities within the catalyst.

a Schematic representation of the oxidation of CH4 to CH3COOH. The black, red, and gray spheres represent C, O, and H atoms, respectively. b CH4 Oxidation performances on C3N4, C3N4-gel, Fe-SAC/g-C3N4, Fe2(CO)9, and Fe-DAC/g-C3N4. c 13C NMR spectra of the liquid products for Fe-DAC/g-C3N4. d Correlation between product distribution and CH4 pressure catalyzed by Fe-DAC/g-C3N4. e Comparative analysis of CH3COOH productivity and selectivity during the CH4 oxidation reaction (Please see Table S7 for samples represented by numbers in e). f Evolution of product distribution and selectivity over Fe-DAC/g-C3N4. g CH4 bubble contact angles and water contact angles for C3N4 and Fe-DAC/g-C3N4. h Detection of •OH and •CH3 groups in various reaction systems. i Detection of •OOH groups in different reaction systems. j, k In situ DRIFTS spectra of Fe-DAC/g-C3N4 and Fe2(CO)9 under 1 atm CH4 at 20 °C. l Schematic illustration of Fe-DAC/g-C3N4 for the conversion of CH4 to CH3COOH.

The influence of various reaction conditions on the oxidation of methane to acetic acid was systematically examined. As illustrated in Fig. S25 and Table S4, the yield of CH3COOH (YCH3COOH) exhibits a strong dependence on temperature. Specifically, the YCH3COOH increases from 1.67 mmol gcat−1 h−1 at 20 °C to 2.14 mmol gcat−1 h−1 at 80 °C. Concurrently, the YCH3OOH rises from 0.06 mmol gcat−1 h−1 at 20 °C to 0.32 mmol gcat−1 h−1 at 80 °C. While higher temperatures promote the rapid formation of CH3COOH, the more pronounced increase in CH3OOH yield results in a decrease in selectivity for CH3COOH, from 96.4% at 20 °C to 87.1% at 80 °C. This indicates that lower temperatures are more conducive to C–C coupling reactions (leading to CH3COOH formation) compared to C–O coupling reactions (resulting in CH3OOH formation). Figure S26 and Table S5 demonstrate the effects of varying H2O2 amounts on CH4 oxidation over the Fe-DAC/g-C3N4 catalyst. Increasing the amount of H2O2 enhances the product yield; however, when the amount of H2O2 exceeds 3.0 mL, the selectivity for CH3COOH slightly declines. Methane pressure is another critical factor influencing the reaction performances. For Fe-DAC/g-C3N4, the YCH3COOH increases from 0.79 mmol gcat−1 h−1 at 0.5 MPa CH4 to 2.05 mmol gcat−1 h−1 at 2.0 MPa CH4, with a selectivity consistently exceeding 94%. Notably, at 0.5 MPa CH4, only CH3COOH is observed, highlighting the exceptional performance of Fe-DAC/g-C3N4 (Fig. 5d, Supplementary Fig. S27 and Table S6). As shown in Fig. S28, the rate dependence of CH3COOH formation on CH4 pressure follows a 0.68-order, which is lower than the stoichiometric value (second-order), indicating that the Fe-DAC/g-C3N4 may be relatively saturated with CH417. In the context of CH4 oxidation to CH3COOH, Fe-DAC/g-C3N4 exhibits the highest selectivity for CH3COOH and outperforms most catalysts (Fig. 5e and Supplementary Table S7).

The evolution of CH3COOH yield and selectivity over time at 20 °C and 1.5 MPa (Fig. 5f and Supplementary Table S8) was next studied. As the reaction time was prolonged, YCH3COOH gradually increased from 1.67 mmol gcat−1 at 1 h to 5.11 mmol gcat−1 at 9 h, while maintaining consistent selectivity. Additionally, Supplementary Fig. S29 and Table S9 shows that the YCH3COOH and selectivity of Fe-DAC/g-C3N4 could be maintained over six operational cycles. Even after five consecutive cycles, the yield of CH3COOH remains at 1.67 mmol gcat−1 h−1, with a selectivity of 96.0%. Inductively coupled plasma–optical emission spectroscopy (ICP‒OES) analysis of the spent catalyst reveals negligible loss of Fe loading compared to the freshly-prepared catalyst (Supplementary Table S1). The SEM images (Supplementary Fig. S30) show that the morphology of Fe-DAC/g-C3N4 remains intact after stability testing, preserving its porous structure. AC-HAADF-STEM and XAS analysis of the spent Fe-DAC/g-C3N4 catalyst (Supplementary Fig. S31) clearly confirms that Fe species retain their initial dispersion without significant aggregation post-catalytic cycles. These results demonstrate the excellent stability of Fe-DAC/g-C3N4.

The origin of the catalytic performance

More insights were paved into the origin of such high catalytic performance of Fe-DAC/g-C3N4 for conversion of CH4 to C2 products. The contact angle measurements (CA, Fig. 5g) of CH4 bubbles on water and CH4/O2 temperature-programmed desorption (TPD, Supplementary Fig. S32) profiles were conducted. Compared with C3N4 (CA = 105°; T = 30.4 °C), Fe-DAC/g-C3N4 exhibits a significantly reduced CH4 CA of 60° and a considerably higher CH4 desorption temperature of 56.0 °C. These reveal the significantly improved CH4 affinity of Fe-DAC/g-C3N4. Besides, the water CA increases from 80° for C3N4 to 110° for Fe-DAC/g-C3N4, indicating that Fe-DAC/g-C3N4 can facilitate the desorption of hydrophilic species like CH3COOH, thereby avoiding excessive oxidation (Supplementary Fig. S33). Low-temperature O2 TPD experiments further corroborate the differential adsorption of oxygen species (e.g., •OH, •OOH) on Fe-DAC/g-C3N4 compared with C3N4. Figure S32 shows that the O2 desorption temperature slightly increases from C3N4 to Fe-DAC/g-C3N4, which is beneficial for the reaction of oxidizing species on the catalyst surface. Moreover, compared to non-gel iron dual-atom catalysts, the iron dual-atom gel catalyst exhibits a significantly larger specific surface area and confined pores (Supplementary Fig. S3), which enhance the CH₄-affinitive restricted space. This results in an increase in acetic acid selectivity on the Fe catalyst surface from 23.7% on Fe2-C3N4 to 96.4% on Fe-DAC/g-C3N4 (Supplementary Fig. S34). This highlights the unique selectivity of dual-atom Fe sites within the CH4-affinitive confined space for the conversion of CH4 to acetic acid.

The role of oxygen radicals in methane activation and the stabilization of oxygenated species is well established. To explore the variations in H2O2 activation across C3N4, Fe2(CO)9, and Fe-DAC/g-C3N4, we investigated the presence and behavior of radicals within these catalytic systems and reaction solutions. The incorporation of Fe2(CO)9 and Fe-DAC/g-C3N4 significantly enhances H2O2 activation compared with C3N4 alone (Fig. 5h, i), resulting in the formation of ·OH and ·OOH radicals, which were successfully detected using 5,5’-dimethyl-1-pyrroline N-oxide (DMPO). Notably, the Fe-DAC/g-C3N4 system shows a marked increase in the concentration of •OH and •OOH radicals, which is consistent with the observed elevated yield of CH3COOH. Furthermore, the detection of •CH3 radicals following the selective oxidation of CH4 suggests that CH4 is activated via a radical mechanism. Remarkably, the filtrate separated from Fe-DAC/g-C3N4 contains negligible quantities of •CH3, •OH, and •OOH radicals, indicating that these radicals are predominantly confined within the nanopores of Fe-DAC/g-C3N4 rather than being present in the solution. This confinement of ·CH3, •OH, and •OOH radicals within Fe-DAC/g-C3N4 enhances the collision frequency and improves the selectivity of the oxidation products.

In situ diffuse reflectance infrared Fourier transform spectroscopy (DRIFTS) measurements further revealed the active species involved in CH4 activation and CH3COOH formation on Fe-DAC/g-C3N4. Compared with the initial state, the introduction of H2O2 and CH4 (1 atm) into Fe-DAC/g-C3N4 results in the appearance of weak new peaks at 3648, 3228, 1683, and 1508 cm−1 (Fig. 5j), which are attributed to adsorbed •OH, •OOH, and H2O244, respectively. Additionally, peaks corresponding to •CH3 (1457 cm−1), •CH3O (1088 cm−1), •CH2 (1473 cm−1), •COOH (1558, 1541, 1521, 1495 cm−1), and C–C (895 cm−1) were also identified45. With the increasing of the reaction time, peaks associated with •CH3 and •COOH intensify significantly, which aligns with the extended CH4 oxidation reactions on Fe-DAC/g-C3N4. In-situ infrared spectroscopy experiments under varying CH4 pressures (Supplementary Fig. 35) were conducted to further elucidate the potential reaction intermediates and mechanism on the Fe-DAC/g-C3N4 surface. At CH4 pressures ≤1.5 MPa, the IR spectra exhibited nearly identical features. However, when the CH4 pressure increased to 2.5 or 3.5 MPa, intensified adsorption of *CH3 (1445 cm−1) and *CH2 (1470 cm−1) on the catalyst surface was observed. This enhancement facilitated the formation of *CH2OH (1016 cm−1) and promoted coupling between intermediates, consistent with the increased product complexity at higher CH4 pressures (Fig. 5d). These results indicate that CH4 is oxidized to •CH3 by radicals generated from H2O2 activation and that •CH3 is further transformed into •OCH3, •CH2, and •COOH. In contrast, Fe2(CO)9 exhibits not only weak peaks for •OCH3 and •COOH radicals but also a distinctive •CH2OH radical peak (Fig. 5k), explaining the formation of CH2OHCH2OH and the diversity of the resulting products. In addition, despite the Fe-DAC/g-C3N4 catalytic system exhibiting remarkable selectivity for CH3COOH during CH4 conversion, in situ DRIFTS reveals no CO-related infrared peaks on the Fe-DAC/g-C3N4 surface Supplementary Fig. S33). This finding emphasizes the efficient suppression of excessive product oxidation by the hydrophobic Fe-DAC/g-C3N4 catalyst and suggests that Fe-DAC/g-C3N4 operates through a catalytic mechanism that diverges significantly from CO-involved pathways (Supplementary Fig. 22)20. To elucidate the potential intermediate species in the reaction, we conducted control experiments with various reactants, including methanol, formic acid, and ethanol. In contrast to the experiments utilizing pure CH4, the introduction of 10 μL of CH3OH significantly increases the yields of CH3COOH and CH3OOH while also leading to the emergence of a novel product, HCOOH (Supplementary Figs. S35 and 36). This observation suggests that •OCH3 is a pivotal intermediate in the conversion of CH4 to CH3COOH. Notably, the addition of 10 μL of HCOOH increases the yield of CH3COOH, along with enhancing the yields of CH3OOH (Supplementary Fig. S37). This indicates that the synthesis of CH3COOH is likely driven by the coupling of the intermediates •CH3 and •COOH. Although ethanol addition elevates the acetic acid content (Supplementary Fig. S38), no ethanol or ethanol oxidation products are detected during pure CH4 oxidation, implying that CH3COOH formation on the Fe-DAC/g-C3N4 surface arises from the coupling of •CH3 and •COOH.

These experimental results highlight the crucial role of Fe dual-atom sites within the methane-accessible confined space in promoting the conversion of CH4 to CH3COOH. Compared to C3N4 nanosheets or the previously reported Cu2 catalysts, the porous channels in Fe-DAC/g-C3N4 nanosheets enhance the residence time and collision frequency of CH4 molecules on the catalyst surface (Fig. 5l), thereby facilitating C–C coupling. The proposed reaction pathway is illustrated in Figs. 1 and 5l. CH4 is preferentially activated at Fe sites in the presence of •OH/•OOH, yielding the Fe-CH3 intermediate. The methyl group can interact with the O atom at the Fe-O2-Fe site to form the CH3O• intermediate. This intermediate subsequently undergoes dehydrogenation through •OH/•OOH action, gradually converting into the Fe-O-COH (COOH) intermediate. Following this, C–C coupling between the carbonyl and methyl groups at the Fe sites results in the formation of Fe-CH3COOH. Importantly, the hypothesis that the methyl group can bind with the O atom in Fe-O2-Fe to form the CH3O• intermediate is supported by the fact that the Fe–O bond length in Fe-O2-Fe approximates the C–C bond length in acetic acid (1.54 Å), thereby facilitating efficient C–C coupling. Consequently, precise control over the catalyst’s active site structure and the concentration of intermediates such as •CH3 or •OCH3 on the surface is crucial for enhancing the yield and selectivity of CH3COOH.

Discussion

We have achieved the complete conversion of CH4 to CH3COOH using CH4 as the sole carbon source by enhancing the adsorption and accumulation of CH4 and its oxidative intermediates and by precisely optimizing Fe dimer sites to facilitate methyl‒carboxyl coupling. Comparative experiments and in situ characterization have provided robust evidence that the porous, hydrophobic surface of Fe-DAC/g-C3N4 significantly enhances CH4 adsorption. In the presence of H2O2, the Fe-O2-Fe sites effectively transform CH4 into •CH3, •OCH3, and •COOH intermediates, with the coupling of •CH3 and •COOH being pivotal for the formation of CH3COOH. This mechanism contrasts sharply with the traditional CO insertion pathway. At a CH4 pressure of 0.5 MPa, Fe-DAC/g-C3N4 achieves complete selectivity for CH3COOH conversion, with a yield of up to 0.79 mmol gcat−1 h−1. Increasing the CH4 pressure to 1.5 MPa boosts the CH3COOH yield to 1.67 mmol gcat−1 h−1 while maintaining a selectivity of over 96%. Further development of this strategy is expected to yield highly efficient and selective catalytic processes, providing novel insights into the selective synthesis of C2+ oxyorganic compounds from methane under mild conditions.

Methods

Synthesis of the Fe-DAC/g-C3N4 and C3N4-gel

Fe2(CO)9-gel was synthesized by mixing C3N4, Fe2(CO)9, and KSCN in aqueous solution, followed by directional freezing and freeze-drying. 2 mg of Fe2(CO)9, 100 mg of C3N4 and 25 mg of KSCN were ultrasonically dispersed in 50 ml of deionized water for 2 h. The mixture was then directionally frozen in −15 °C propylene glycol and subsequently transferred to a freeze-dryer for 48 h, yielding a pale yellow Fe2(CO)9-C3N4-gel. Finally, the Fe2(CO)9-C3N4-gel was placed in a porcelain boat within a tube furnace. The temperature was gradually raised to 500 °C at a rate of 5 °C/min and maintained for 1 h under an argon atmosphere. After cooling to room temperature, it was washed three times with deionized water and dried in a vacuum oven at 60 °C to obtain the Fe-DAC/g-C3N4 (0.52 wt%). The preparation process for the 0.15 wt% and 1.1 wt% samples is identical to that of Fe-DAC/g-C3N4 (0.52 wt%), with the only difference being the variation in the amounts of C3N4, which are 400 mg and 40 mg, respectively. The KSCN can serve both as a binder to promote the formation of a compacted three-dimensional C3N4 network, and as a pore-forming agent to form porous C3N4 gel as a result of releasing gases during pyrolysis process. The synthesis of C3N4-gel is like that of Fe-DAC/g-C3N4, except that Fe2(CO)9 is missing.

Synthesis of the Fe-SAC/g-C3N4

5 mg of FeCl2, 100 mg of C3N4, and 25 mg of KSCN were sonicated in 50 mL of deionized water for 2 h. The resulting mixture was then directionally frozen in −15 °C propylene glycol and subsequently transferred to a freeze dryer for 48 h, yielding a yellow gel. Finally, the gel was placed in a porcelain crucible inside a tubular furnace, where the temperature was gradually increased to 500 °C at a rate of 5 °C/min and held for 1 h under an argon atmosphere, resulting in Fe-SAC/g-C3N4.

Synthesis of the Fe2-C3N4

Disperse 2 mg of Fe2(CO)9 and 100 mg of C3N4 ultrasonically in 50 mL of deionized water for 2 h. Afterward, separate by centrifugation, dry (60 °C, in air), and calcine (1 h at 500 °C in Ar) to obtain Fe2-C3N4.

Catalyst characterization

Scanning electron microscopy (SEM) measurements were performed on a FEI Apreo SEM. Transmission electron microscope (TEM), aberration-correction high-angle annular dark-field scanning TEM (AC-HAADF-STEM) and Energy dispersive spectrometer (EDS) elemental mapping images were recorded on FEI Spectra aberration-corrected TEM at 200 kV and a Talos F200X TEM at 100 kV. The metal loadings of the catalysts were detected by an inductively coupled plasma atomic emission spectrometer (ICP–AES, Thermo ICAP 6300). IR spectra were recorded with a Bruker Invenio S spectrometer with a resolution of 4 cm−1, and each spectrum is an average of 64 scans. The X–ray photoelectron spectra (XPS) were recorded on an ESCALab–250 X photoelectron spectrometer using an Al Kα source (1486.6 eV). Electron paramagnetic resonance measurements were performed at room temperature using a Bruker EMX-10/12 EPR spectrometer operated in the X-band frequency using the following parameters: microwave frequency of 9.8 GZ, microwave power of 20 mW, modulation frequency of 100 kHz, and a 10 dB attenuator. O2–TPD measurements were carried out using the AutoChem II 2920 with a flowing 5% O2/He stream (50 ml/min) at −60 °C. The samples were pretreated with Ar at 150 °C for 1 h to remove the adsorbed gaseous impurities before the TPD test. The X–ray absorption spectroscopy experiments at the Fe K edge were conducted on the 1W1B beamline of the Beijing Synchrotron Radiation Facility (BSRF). Fe foil FeO, and Fe2O3 were used as reference samples. All spectra were recorded in transmission mode at room temperature. We used IFEFFIT software to calibrate the energy scale, correct the background signal, and normalize the intensity.

The sample for in situ IR spectroscopy was loaded into a diffuse reflectance infrared Fourier transform spectroscopy (DRIFTS) cell (Harrick Scientific Products, Praying MantisTM). The cell was connected to a flow system that allows recording of spectra while gases pass through and around the sample. The samples in IR cell were pretreated at 200 °C for 1 h and then cooled down to 20 °C in flowing Ar (30 mL/min). The infrared spectrum at this moment serves as the background. Subsequently, CH4 and H2O2 were introduced into the gas stream while the time-resolved reflectance spectra were collected.

Pressurized in-situ infrared spectroscopy experiments were performed on a Thermo Nicolet IS50 FT-IR spectrometer equipped with a pressure-resistant in situ infrared diffuse reflectance cell (Hefei In Situ Technology Co., Ltd., China). Transmission spectra were collected throughout the experiment. The sample was first loaded into the cell, heated to 150 °C under 50 sccm Ar flow, held for 1 h, then cooled to room temperature. Background spectra were acquired after thermal pretreatment. CH4 was then introduced to bubble through H2O2, carrying the vapor into the reaction chamber until reaching target pressure. Reaction spectra were collected after 30 min.

Catalytic reactions

Methane conversion was tested in a 50 ml stainless-steel autoclave. For a typical run, 5 mg catalyst, 2 ml H2O2, and 9 ml deionized water were added into an autoclave. This was then flushed with argon 3 times and pressurized to 1.5 MPa CH4. The reaction mixture was stirred at an optimized speed of 1000 rpm to promote mass transfer and heated to the desired reaction temperature (typically 20 °C) at a ramp rate of 10 °C/min for a fixed reaction time (typically 1 h). After reaction, the autoclave was immediately cooled to a temperature below 10 °C in an ice bath to minimize the loss of volatile products. The gas product was directly detected by GC and then the liquid product was filtered for the subsequent analysis. For isotopic reaction, ≥99% 13C-enriched CH4, was used to trace the source of carbon in the products.

The reusability test of the catalyst was evaluated as follows. After the first reaction cycle, the catalyst (5 mg) was washed with deionized water and centrifuged several times, and then the sample was dried overnight at room temperature in a vacuum desiccator. This dried sample was subsequently evaluated under the same reaction conditions to obtain the performance of second cycle of the catalyst. The remaining cycles were carried out in the same way; more than 6 reaction cycles were repeated.

Data availability

The raw data generated in this study are provided in the Supplementary Information. All data are available from the corresponding author upon request.

References

Tang, Y., Li, Y. & Tao, F. Activation and catalytic transformation of methane under mild conditions. Chem. Soc. Rev. 51, 376–423 (2022).

Blankenship, A., Artsiusheuski, M., Sushkevich, V. & van Bokhoven, J. A. Recent trends, current challenges and future prospects for syngas-free methane partial oxidation. Nat. Catal. 6, 748–762 (2023).

An, B. Direct photo-oxidation of methane to methanol over a mono-iron hydroxyl site. Nat. Mater. 21, 932–938 (2022).

Sushkevich, V. L., Palagin, D., Ranocchiari, M. & van Bokhoven, J. A. Selective anaerobic oxidation of methane enables direct synthesis of methanol. Science 356, 523–527 (2017).

Jin, Z. et al. Hydrophobic zeolite modification for in situ peroxide formation in methane oxidation to methanol. Science 367, 193–197 (2020).

He, C. et al. Photocatalytic conversion of methane to ethanol at a three-phase interface with concentration-matched hydroxyl and methyl radicals. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 146, 11968–11977 (2024).

Jin, R. et al. Low Temperature oxidation of ethane to oxygenates by oxygen over iridium-cluster catalysts. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 141, 18921–18925 (2019).

Zeng, L. et al. Stable anchoring of single rhodium atoms by indium in zeolite alkane dehydrogenation catalysts. Science 383, 998–1004 (2024).

Xie, J. et al. Stable photocatalytic coupling of methane to ethane with water vapor using TiO2 supported ultralow loading AuPd nanoparticles. Acta Phys. -Chim. Sin. 39, 2306037 (2023).

Sui, J. F. et al. Bioinspired microenvironment modulation of metal-organic framework-based catalysts for selective methane oxidation. Sci. Bull. 68, 1886–1893 (2023).

Dong, Y. C. et al. Highly efficient chemical production via electrified, transient high-temperature synthesis. eScience 4, 100253 (2024).

Jiang, Y. H., Fan, Y. Y., Li, S. Y. & Tang, Z. Y. Photocatalytic methane conversion: insight into the mechanism of C(sp3)-H bond activation. CCS Chem. 5, 30–54 (2023).

Zhang, Q. et al. Regulating mono-/binuclear Fe species in framework Al-rich zeolites for efficient low temperature alkane oxidation. CCS Chem. 7, 819–831 (2025).

Periana, R. A., Mironov, O., Taube, D., Bhalla, G. & Jones, C. Catalytic, oxidative condensation of CH4 to CH3COOH in one step via CH activation. Science 301, 814–818 (2003).

Wu, B. et al. Fe binuclear sites convert methane to acetic acid with ultrahigh selectivity. Chem 8, 1658–1672 (2022).

Shan, J., Li, M., Allard, L. F., Lee, S. & Flytzani-Stephanopoulos, M. Mild oxidation of methane to methanol or acetic acid on supported isolated rhodium catalysts. Nature 551, 605–608 (2017).

Li, H. et al. Selective methane oxidation by heterogenized iridium catalysts. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 145, 769–773 (2023).

Li, H. et al. Selective formation of acetic acid and methanol by direct methane oxidation using rhodium single-atom catalysts. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 145, 11415–11419 (2023).

Liu, J. et al. Isolated Ni sites anchored on zeolites for direct synthesis of acetic acid from methane oxidative carbonylation. Appl. Catal. B Environ. Energy 350, 123951 (2024).

Xu, W. et al. Metal-oxo electronic tuning via in situ co decoration for promoting methane conversion to oxygenates over single-atom catalysts. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 63, e202315343 (2024).

Qi, G. et al. Au-zsm-5 catalyses the selective oxidation of CH4 to CH4OH to CH3COOH using O2. Nat. Catal. 5, 45–54 (2022).

Hou, Z. et al. Electronically engineering water resistance in methane combustion with an atomically dispersed tungsten on PdO catalyst. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 61, e202201655 (2022).

Shi, Y. et al. Homogeneity of supported single-atom active sites boosting the selective catalytic transformations. Adv. Sci. 9, 202201520 (2022).

Liu, Y. et al. Unravelling the enigma of nonoxidative conversion of methane on iron single-atom catalysts. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 59, 18586–18590 (2020).

Nie, S. et al. High-entropy-perovskite subnanowires for photoelectrocatalytic coupling of methane to acetic acid. Nat. Commun. 15, 6669 (2024).

Zhou, H. et al. Organocatalytic stereoselective cyanosilylation of small ketones. Nature 605, 84–89 (2022).

Ma, Y. et al. Germanium-enriched double-four-membered-ring units inducing zeolite-confined subnanometric pt clusters for efficient propane dehydrogenation. Nat. Catal. 6, 506–518 (2023).

Zhang, H. et al. Confined cu-oh single sites in SSZ-13 zeolite for the direct oxidation of methane to methanol. Nat. Commun. 14, 7705 (2023).

Fujisaki, H. et al. Selective methane oxidation by molecular iron catalysts in aqueous medium. Nature 616, 476–481 (2023).

Hai, X. et al. Geminal-atom catalysis for cross-coupling. Nature 622, 754–760 (2023).

Wang, R. et al. Switching the symmetry of a trinuclear copper cluster catalyst for electroreducing CO2 to an asymmetric C2 product in an acidic electrolyte. ACS Catal. 14, 741–750 (2024).

Gao, R. et al. Pt/Fe2O3 with Pt–Fe pair sites as a catalyst for oxygen reduction with ultralow Pt loading. Nat. Energy 6, 614–623 (2021).

Wang, J. M. et al. Asymmetric gradient orbital interaction of hetero-diatomic active sites for promoting C-C coupling. Nat. Commun. 14, 3808 (2023).

Liang, H. et al. Operando mobile catalysis for reverse water gas shift reaction. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 63, e202318747 (2024).

Zhang, C. et al. Efficient and selective photocatalytic oxidation of CH4 over Fe single-atom-incorporated MOFs under visible light. ACS Catal. 13, 15351–15359 (2023).

Wang, C. et al. Synergy of ag and agbr in a pressurized flow reactor for selective photocatalytic oxidative coupling of methane. ACS Catal. 13, 3768–3774 (2023).

Luo, L. et al. Binary au–cu reaction sites decorated zno for selective methane oxidation to c1 oxygenates with nearly 100% selectivity at room temperature. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 144, 740–750 (2022).

Bu, F. et al. Boosting benzene oxidation with a spin-state-controlled nuclearity effect on iron sub-nanocatalysts. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 62, e202216062 (2022).

Rong, H., Ji, S., Zhang, J., Wang, D. & Li, Y. Synthetic strategies of supported atomic clusters for heterogeneous catalysis. Nat. Commun. 11, 5884 (2020).

Zhang, B. et al. Polarized few-layer g-C3N4 as metal-free electrocatalyst for highly efficient reduction of CO2. Nano Res 11, 2450–2459 (2018).

Xu, D. et al. Boosting mass exchange between Pd/NC and Mo/NC dual junctions via electron exchange for cascade CO2 fixation. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 144, 5418–5423 (2022).

Li, Y. et al. Cayanamide group functionalized crystalline carbon nitride aerogel for efficient CO2 photoreduction. Adv. Funct. Mater. 34, 2312634 (2024).

Xie, P. et al. Oxo dicopper anchored on carbon nitride for selective oxidation of methane. Nat. Commun. 13, 1375 (2022).

Mane, G. P. et al. Highly ordered nitrogen-rich mesoporous carbon nitrides and their superior performance for sensing and photocatalytic hydrogen generation. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 56, 8481–8485 (2017).

Chen, Z. et al. Stabilization of single metal atoms on graphitic carbon nitride. Adv. Funct. Mater. 27, 1605785 (2017).

Wan, X. et al. Iron atom–cluster interactions increase activity and improve durability in Fe–N–C fuel cells. Nat. Commun. 13, 2963 (2022).

Yan, J. Y. et al. Self-supported cuprous oxide/graphdiyne nanosheets array for efficient ammonia synthesis. ChemPhysMater 4, 131–136 (2025).

Xia, L. et al. Operando-informed precatalyst programming towards reliable high-current-density electrolysis. Nat. Mater. 24, 753–761 (2025).

Nie, S., Wu, L. & Wang, X. Electron-delocalization-stabilized photoelectrocatalytic coupling of methane by nio-polyoxometalate sub-1 nm heterostructures. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 145, 23681–23690 (2023).

Wu, B. et al. Highly selective synthesis of acetic acid from hydroxyl-mediated oxidation of methane at low temperatures. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 63, e202412995 (2024).

Fang, G. et al. Retrofitting zr-oxo nodes of uio-66 by ru single atoms to boost methane hydroxylation with nearly total selectivity. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 145, 13169–13180 (2023).

Mao, J. et al. Direct conversion of methane with O2 at room temperature over edge-rich MoS2. Nat. Catal. 6, 1052–1061 (2023).

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by the National Key Research and Development Project of China (2024YFA1509400), the Taishan Scholars Youth Expert Program of Shandong Province (tsqn201909050), the Natural Science Foundation of Shandong Province (ZR2024ZD02, ZR2021JQ07) and the Shandong University Youth Students’ Basic Research Program (SDUQM2502). We thank Professor Yong Qin and Chaoqiu Chen from the Institute of Coal Chemistry, Chinese Academy of Sciences, for their assistance in the in situ infrared spectroscopy and O2-TPD, Professor Lirong Zheng at the 1W1B station of the Beijing Synchrotron Radiation Facility for XAFS measurements, and Professor Tie Yu from the Institute of Frontier Chemistry, School of Chemistry and Chemical Engineering, Shandong University, for his assistance in the infrared testing.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Y.X. conceived and designed the research, and critically revised the manuscript. F. B. synthesized the catalysts, performed the activity tests, analyzed the data, and wrote the draft. J.Y. helped the synthesis of catalyst. L.Q. and S.Z. helped the characterization of the samples. All authors contributed to the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Peer review

Peer review information

Nature Communications thanks Takahiko Moteki, and the other, anonymous, reviewer(s) for their contribution to the peer review of this work. A peer review file is available.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Bu, F., Yan, J., Qi, L. et al. Coordination-tailored atomic interfaces for selective CH4-to-C2 conversion in aqueous solution. Nat Commun 16, 9161 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-025-64248-7

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-025-64248-7