Abstract

Photonic neuromorphic computing has emerged as a promising approach toward energy-efficient artificial neural networks (ANN). Nanolasers, in particular, have become attractive candidates due to their ultra-low power consumption and intrinsic nonlinear characteristics. In this work, we propose a photonic neuromorphic computing architecture based on symmetry-protected robust zero modes at the center of the optical spectrum in coupled semiconductor nanolaser arrays. We experimentally demonstrate that even a small set of coupled nanolasers inherently provides non-convex classification capabilities, enabling it to solve non-trivial classification tasks. As a benchmark, we show that a 2 × 2 nanolaser array, acting as a hidden nonlinear layer with recurrent coupling is able to solve the XNOR logical gate. Our results further highlight the computation capabilities of such nanolaser array by showing robust classification performance even under challenging conditions, such as the classification of highly compressed handwritten digits with significantly overlapping feature boundaries. These findings suggest that symmetry or topologically protected modes in nanolaser arrays can leverage robust optical connections to tackle complex problems without the need of scaling up the number of neurons.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Artificial neural networks (ANNs) are undergoing unprecedented growth, continually advancing the boundaries of artificial intelligence systems1. However, this rapid progress has also led to an exponential increase of energy consumption during the training process. Consequently, an alternative paradigm known as neuromorphic computing—aiming at developing hardware-level frameworks with significantly lower energy consumption—has attracted considerable attention2,3,4.

Photonics provide a promising platform in this context, leveraging the unique properties of light to meet growing computational demands5,6,7,8. By enabling remarkable processing speeds, high parallelism, and superior energy efficiency, photonic hardware can outperform conventional electronic architectures for certain specialized tasks, such as vector-matrix multiplications9,10 and solving nonlinear optimization tasks11.

A key element in neuromorphic computing is the activation function, which in photonic systems is commonly implemented through various nonlinear mechanisms such as optical bistability and saturable absorption9. Recent studies have also demonstrated that nonlinearity can be achieved through linear wave scattering12,13,14, presenting an alternative pathway for photonic activation functions.

Nevertheless, the aforementioned nonlinearities often require additional nonlinear or scattering materials, increasing overall design complexity. In contrast, micro- and nanolasers—notably in semiconductor media—offer intrinsic nonlinearities through gain saturation and nonlinear dispersive effects, compatible with photonic integration15. Semiconductor lasers have already been successfully demonstrated as efficient building blocks in neuromorphic computing. In a seminal work16, an edge-emitting device with feedback has been employed in a reservoir computing paradigm, which has been extended some years later to the nanoscale17. Vertical-cavity surface-emitting lasers have also been recently implemented in neuromorphic computing18 and deep learning approaches19. In addition, coupled nanolaser arrays have been proposed and theoretically investigated as pseudo-spins in Ising machines20. In this context, nanolasers emerge as particularly promising candidates for energy-efficient photonic neuromorphic computing owing to their ultra-low lasing thresholds21,22,23,24,25, which are attributed to the high quality factors (Q), ultra small mode volumes (V), and large spontaneous emission factors (β)15.

Recent advancements in nanoscale fabrication techniques now enable the creation of large-scale nanolaser networks, further broadening the potential of these devices for a variety of applications26,27. One particularly intriguing area is non-Hermitian topological photonics, where nanolaser arrays can be engineered to exploit symmetry and/or topological protection for robust, disorder-tolerant operation28,29,30,31. The integration of symmetry or topologically protected optical modes into neuromorphic computing architectures might pave a novel pathway toward the next generation of robust nanolaser-based ANNs.

In this work, we propose and experimentally realize a photonic neuromorphic computing architecture based on a small array of evanescently-coupled III–V semiconductor photonic crystal (PhC) nanolasers with embedded quantum wells. It has been shown that standard two-dimensional geometries—such as rectangular lattices—of coupled cavities with gain-loss perturbations exhibit various non-Hermitian symmetries, including parity-time symmetry30, non-Hermitian particle-hole (NHPH) symmetry32,33, and non-Hermitian chiral symmetry34. As a consequence, a symmetry-protected zero mode35 can be excited through an exceptional point (EP) bifurcation—a singularity where both eigenvalues and eigenvectors coalesce. Following on our pervious theoretical work36, here we experimentally show that our coupled nanolaser array functions as a nonlinear layer with recurrent coupling in an ANN architecture, where symmetry-protected zero modes serve as positive output for classification tasks. In particular, we will demonstrate that our system outperforms single-layer neural architectures by solving a non-convex problem such as the XNOR logical gate. Moreover, the inherent nonlinear properties of our system enhance its ability to process data and maintain robust performance for challenging conditions, particularly when class boundaries are overlapped in the feature space. This is experimentally verified by compressing the dimensionality of the input image in a handwritten digit classification problem, confirming that our system can satisfactorily perform on non-trivial—in the sense of non-convex—classification tasks. Although the concept of topologically protected modes for optical computing can be ideally applied in systems or networks featuring many protected modes, here we analyze a small-scale array consisting of four coupled nanolasers. Even if small in scale, such physical systems can serve as effective toy models to start exploring new technological perspectives. Notable examples are spintronic nano-oscillators37,38 and memristors39, which have been successfully leveraged for AI tasks, offering both energy- and footprint-efficient alternatives to large-scale architectures3.

Results

General principle

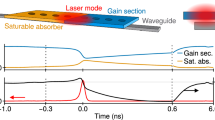

The principle of our coupled nanolasers is illustrated in Fig. 1. For illustration purposes, we will focus on an image classification task. Let us consider an image of a handwritten “1” with dimensions Ix × Iy, where Ix and Iy represent the number of pixels in the x and y directions, respectively. The input matrix is then reshaped into a one-dimensional column vector, \({{{\bf{I}}}}^{{\prime} }\), consisting of m = Ix × Iy elements in total. The input information is subsequently encoded into the pump patterns P through a linear matrix M(p × m), specifically \({{\bf{P}}}(p\times 1)=| {{\bf{M}}}(p\times m){{{\bf{I}}}}^{{\prime} }(m\times 1)|\), where p is the total number of cavities on the photonic chip (see the insert below the hidden layer in Fig. 1). Finally, the pump pattern is projected onto the nanolaser array via a spatial light modulator (SLM). The coefficients of M are adjusted such that the optical spectrum—serving as the output layer—exhibits a lasing zero mode (interpreted as a positive response) when the digit “1” is presented. Conversely, for any other handwritten digit, the zero mode remains off, indicating a negative response36.

Two key features are at the heart of our architecture. First, the nanolaser array acts as a hidden recurrent nonlinear layer of the optical ANN, enabling the system to tackle classification tasks—including non-convex problems, as will be shown in Sec. “XNOR logic gate”. Second, the semiconductor lasers inherently provide a nonlinear activation function through gain saturation, which plays an important role when feature-space boundaries are highly overlapped, as will be presented in Sec. “Binary classification”.

Symmetry protected zero modes

We consider a tight-binding arrangement of optical cavities, with on-site frequencies ωj, uniform losses κ and on-site gain rates gj. The corresponding Hamiltonian is given by:

where δjk is the Kronecker-δ. For simplicity, we begin by assuming that all cavities share the same resonant frequency, which allows us to set ωj = 0 without loss of generality. In a square lattice, the evanescent wave coupling (K is real) is represented by

Here, T represents an nA × nB matrix, where nA and nB denote the size of two sublattices; these are defined as the two subsets A and B of the array such that the couplings only link cavities belonging to different subsets (see the hidden layer in Fig. 1).

It is straightforward to verify that the Hamiltonian in the Hermitian limit (gj → 0) exhibits both chiral and particle-hole symmetry. Specifically, chiral—or sublattice—symmetry is characterized by the anticommutation relation \(\{{{\mathcal{C}}},{{\bf{H}}}\}=0\)34, while particle-hole (PH) symmetry is represented by the relation \(\{{{\mathcal{CT}}},{{\bf{H}}}\}=0\)35, where \({{\mathcal{C}}}\) denotes a unitary operator and \({{\mathcal{T}}}\) represents the time-reversal operator. As a result, these two symmetries give rise to a real eigenvalue spectrum symmetric about ϵ0 = 0. This is illustrated in Fig. 2a for the system considered in this work: four coupled optical cavities in a ring configuration. In such a system, sublattice A consists of cavities in the vertical direction (cavities 1 and 4), while sublattice B encompasses the horizontally oriented cavities (cavities 2 and 3).

a In the Hermitian limit, both particle-hole and chiral symmetry lead to a symmetric eigenvalue spectrum around ϵ = 0. We call the two cavity subsets colored in blue and red sublattices A and B, respectively. b Pumping sublattice B (red cavities) triggers spontaneous PH symmetry restoration at an EP, giving rise to the zero mode. c Including the carrier-induced frequency shift breaks PH symmetry but leaves non-Hermitian chiral symmetry intact, i.e., the eigenvalues are symmetric around shifted origin \({\epsilon }_{0}^{{\prime} }=\frac{{\Delta }_{A}+{\Delta }_{B}}{2}\). By introducing sublattice detuning to compensate for this shift, the system again realizes an EP, along with the zero mode. Here in the simulations, we take K1 = −1.5, K2 = −1, κ = 1 and α = 3. In (b and c) only sublattice B is pumped; the rectangles and diamonds indicate the spectra at gB = 0, gB = 1.25, and gB = 1.5, respectively. The stars in (b) and (c) mark the location of the exceptional points.

In the non-Hermitian regime (gj ≠ 0), however, the eigenvalues become generally complex, and these two symmetries yield distinct consequences: chiral symmetry enforces eigenvalue spectrum satisfying ϵn = −ϵm, whereas NHPH symmetry leads to eigenvalues satisfying \({\epsilon }_{n}=-{\epsilon }_{m}^{*}\), where * denotes complex conjugation. Thus, zero modes remain at ϵ = 0 under chiral symmetry, while NHPH symmetry allows for modes to evolve along the imaginary axis of the complex plane—i.e., satisfying \({{\rm{Re}}}[\epsilon ]=0\)—over the entire range of spatial perturbations induced by the pump beams40. In the non-Hermitian four coupled cavity ring with all the cavities having the same resonant frequency, the zero mode arises from NHPH symmetry, which manifests through spontaneous symmetry restoration at an EP bifurcation, as shown in Fig. 2b. In other words, once these zero modes are formed, they have the same resonant frequency as a single cavity mode, independent of the pump beam. Exploiting these symmetry-protected zero modes can enhance robustness against structural coupling disorders and pump perturbations, making them promising candidates for implementing resilient optical neuromorphic computing systems36.

It is important to point out, however, that in active III–V semiconductor materials, nonlinear dispersive effects significantly modify these underlying symmetries. Specifically, the refractive index changes in response to variations in the charge-carrier population (electrons and holes), leading to the pump-induced cavity frequency shift modeled by the terms αgj, where α is the Henry—also called linewidth enhancement—factor. Consequently, pumping one of the sublattices (e.g., gA = 0 and gB ≠ 0) introduces carrier-induced sublattice detuning, explicitly breaking the NHPH symmetry and prohibiting the formation of both EPs and zero modes. To compensate for the frequency shift, one must introduce a linear detuning41 which, in the present case, red-shifts sublattice B, satisfying ωA–ωB = 2α∣K1–K2∣. This condition can be achieved in a PhC ring-like coupled nanocavity geometry, as shown in Fig. 3c. In such a design, we engineer the coupling difference by means of a design parameter, ∣K1–K2∣ ~ 70 GHz, while relying on the intrinsic sublattice detuning, ωA–ωB ≈ 500 GHz. Taking these considerations into account, the final Hamiltonian can be expressed as:

Where ΔA,B = ωA,B + αgA,B + i(gA,B − κ). We can verify that this Hamiltonian exhibits non-Hermitian chiral symmetry34, which, as shown in Fig. 2c, enforces an eigenvalue spectrum symmetric about the shifted origin \({\epsilon }_{0}^{{\prime} }\) of the complex plane, where \({\epsilon }_{0}^{{\prime} }=\frac{{\Delta }_{A}+{\Delta }_{B}}{2}\) varies with the pump power. With the previously described linear sublattice detuning, the system can satisfy the EP condition and subsequently excite a zero mode warranted by the non-Hermitian chiral symmetry.

a Definitions of the convex and non-convex regimes. b Illustration of the XNOR problem. The dots represent the input-output states of an XNOR gate, the solid line denotes the decision boundary (hyperplane) achievable by a single-layer perceptron and the dashed lines represent the decision boundaries obtained by a multilayer ANN. The positive responses (output = 1) are marked in orange, and the negative responses (output = 0) are marked in green. Clearly, the single-layer perceptron is unable to correctly represent this non-convex classification task. c Experimental setup. Two representative system responses are shown on the left: the top panel corresponds to a positive response, characterized by lasing of the quasi-zero modes, whereas the lower panel demonstrates a negative response, in which the zero mode remains off. On the right side, representative pump patterns generated using the SLM are depicted, with white circles indicating the cavity positions. The schematic of the coupled cavity array is shown at the bottom of the figure, where the boxes highlight the photonic barriers engineered to introduce asymmetric couplings (hole radii modification: −17%).

For classification purposes, we categorize pump patterns that effectively excite the central two modes—i.e., quasi-zero modes—as positive inputs, while those that trigger side-mode lasing are classified as negative inputs (see the spectrum in the output layer of Fig. 1). A detailed eigenvalue analysis for different pump patterns is provided in the Supplementary Note 2.

XNOR logic gate

As discussed in the previous section, our coupled cavity arrays cannot be mapped into a single-layer of optical neurons without intra-layer couplings. Otherwise saying, it cannot be mapped to a Perceptron. As a matter of fact, the chiral symmetry dictates that the ring array can be decomposed as two layers (or sublattices)—the chiral partners, featuring inter-layer couplings. As such, it may in principle solve different tasks including convex—where any two points in the region can be connected by a straight line that lies fully in that region—as well as non-convex classification problems (see Fig. 3a). Noticeably, while the convex classification tasks do not necessarily require hidden layers, non-convex problems do42. In the following, we demonstrate the capability of our nanolaser array as a recurrent nonlinear hidden layer of an optical ANN architecture to implement a XNOR logic gate—a fundamental non-convex classification problem that cannot be solved by a single-layer perceptron—schematically illustrated in Fig. 3b. This provides experimental evidence that our nanolaser array can effectively tackle non-trivial classification tasks.

Our photoluminescence (PL) experimental configuration is depicted in Fig. 3c (a detailed discussion about the setup can be found in the “Methods”). We bias our nanolaser array in order to excite a lasing zero mode, realized by means of a specific SLM-induced pump pattern (P1 = P4 = 4.1 μW and P2 = P3 = 5.7 μW). We recall that this lasing zero mode is warranted by the underlying non-Hermitian chiral symmetry. We assign the pump powers in cavities 1 and 4 as the input ports I1 and I2 of the XNOR gate (detailed photoluminescence experimental results can be found in the Supplementary Note 3). Specifically, we define:

I1 and I2 take the same binary values, i.e., 0 (1) if the respective pump power is 4.1μW (8.2μW). Meanwhile, the pump power in cavity 2 and 3 remain fixed. Note that in this simplified binary classification task, the reshaping operation shown in Fig. 1 is not necessary.

To confirm our nanolaser array’s ability to represent the XNOR logic gate in a systematic way, we continuously vary the pump powers in cavities 1 and 4 and monitor the status of the zero mode. To quantify the output, we define an intensity ratio between the zero-mode laser and the other modes as follows:

where mz denotes the intensity of the zero mode or the quasi-zero mode, mb and mr represent the intensities of the blue-most and red-most modes, respectively (see Fig. 3c for notation). This ratio characterizes the output state: if R > 2.5 we assign a positive response, indicating the dominance of the zero mode; otherwise, if R ≤ 2.5, we categorize the output as negative.

Figure 4a shows the experimental results. Notably, the positive regions—where the ratio R > 2.5—are predominantly localized near the diagonal corners of the parameter space (highlighted in yellow). This clearly demonstrates that our nanolaser array effectively encodes the two-state XNOR output, thus providing direct experimental evidence of its capability to solve non-convex classification tasks. Additionally, Fig. 4b illustrates four representative input-output configurations corresponding precisely to the entries in Fig. 3b, successfully reproducing the XNOR truth table. It can be observed that the selected zero modes (O = 1) have significantly different spectra in the two cases (blue and black traces in Fig. 4b). This is due to the bias we set, that excites a zero mode with large intensity ratio in the absence of extra inputs—i.e., at large pump imbalance—, while R decreases for simultaneous active input ports since the zero-mode approaches the EP.

Binary classification

To fully unlock the capabilities of our nanolaser array for more challenging tasks, we employ a machine learning algorithm to optimize the system’s performance. Namely, we carefully adjust the coefficients of the matrix M based on the linear eigenvalue problem of the laser array36, i.e., diagonalizing the H-matrix (Eq. (3)). Such a theoretical description of the laser system can be considered as a piecewise linear modeling: we solve the eigenmode problem until a given mode reaches the lasing threshold; further pump increase above threshold is assumed to result in gain clamping, and therefore the single lasing mode frequency also gets clamped. Such piecewise linear model—which includes the carrier-induced refractive index change, but rules out mode switching and other nonlinear dynamical effects (see Supplementary Note 6 for a discussion)—serves as a digital twin of the experiment. It not only accurately predicts which mode lases first but also significantly reduces computational time, allowing the efficient calculation of the matrix M.

Let us recall the operation principle: pump patterns associated with the positive-class samples excite the zero modes, while those corresponding to negative-class samples excite other modes. Specifically, we employ an in silico optimization algorithm to determine the elements of matrix M in a way that maximizes agreement between predictions and ground truth. Full details of the algorithm are provided in ref. 36. To mitigate overfitting, we train the algorithm on 75% of the dataset and validate its performance on the remaining 25%.

Iris dataset

To demonstrate the feasibility of this approach, we begin with a widely recognized benchmark: the Iris dataset43. This dataset contains 150 measurements of 4 geometric features for three Iris species: Setosa, Versicolor, and Virginica. For consistency, we normalize each feature to have zero mean and unit variance.

Once the matrix M for the Iris dataset is determined using the linear Hamiltonian, we first numerically evaluate the performance of our optical ANN by calculating the eigenvalues of Eq. (3). The results, shown in Table 1, include accuracy—defined as the fraction of correctly classified samples—and the F1 score, a widely used metric for overall effectiveness, defined by: \({{\rm{F1}}}=2\times \frac{{{\rm{Precision}}}\times {{\rm{Recall}}}}{{{\rm{Precision}}}+{{\rm{Recall}}}}\), where Precision is the fraction of correctly predicted positive classifications among the samples predicted as positive, and Recall is the fraction of correctly predicted positive classifications among all actual positive samples44. Although both accuracy and F1 vary according to the specific flower species being classified, our algorithm maintains consistently high performance across all classes in simulation.

We further use the fitted M elements to experimentally evaluate the classification performance. As in the in silico case, the performance varies depending on the specific flower being classified, as shown in Table 1. Notably, the experimental results closely match their simulated counterparts, building confidence on the digital twin model used here, that accurately captures the nanolaser array’s behavior within the operational regime.

Notably, for the Setosa class, our classifier achieves an accuracy of 100% both in simulations and experiments. This perfect classification is attributed to the clear separability of Setosa from the other classes in the feature space, as illustrated in Fig. 5a. Consequently, even the single-layer perceptron is sufficient to reliably distinguish this class. On the other hand, the Versicolor and Virginica classification regions slightly overlap, featuring a nonlinear boundary (dashed line in Fig. 5a), which makes it difficult for a single-layer perceptron to resolve this inherently non-convex classification problem. In contrast, our nanolaser-based architecture, benefiting from its intrinsic nonlinearity and recurrent couplings, still achieves robust performance, demonstrating its ability to handle complex classification tasks effectively.

a Iris dataset showing that Setosa is clearly separated from the rests, while Versicolor and Virginica exhibit some overlap. The dashed line represents the non-convex boundary. b and c present the handwritten digits dataset, illustrating two clusters representing digits “0” and “1” at different image resolutions. The decreasing dimensionality (from 8 × 8 to 2 × 2) leads to significant overlap between classes.

Compressed handwritten digit

To further assess the computational boundaries of our system, we evaluate its performance on a highly compressed handwritten digits dataset. This more challenging test case induces severe information loss, resulting in substantial class overlap within the feature space, thereby making the classification task more difficult. Such problems typically require nonlinear classifiers to achieve reasonable performance. In our system, the intrinsic nonlinearity—stemming from gain saturation in the nanolaser array—together with the non-convex classification capabilities demonstrated above, enables effective handling of this non-trivial classification task (a detailed comparison between linear classifiers and our nanolaser array is provided in the Supplementary Note 4).

To further illustrate our approach, we focus on handwritten zeros (“0”) and ones (“1”), which constitute two well-separated classes for high-enough image resolution. To introduce confusion between classes in the classification problem, we compress the input features from 64 (corresponding to an 8 × 8 image) down to 4, representing a 2 × 2 image. The experimental results are illustrated in Fig. 6, where we compare the performance of our nanolaser array both in experiments (marked by hexagrams) and in simulations (marked by blue crosses) with other nonlinear classifiers, including a 2 × 2 artificial neural network (ANN, marked by orange diamonds; see details in Supplementary Note 5) and a random forest (RF, marked by purple triangles). We also include a simple single-layer perceptron (marked by yellow triangles) for comparison.

At relatively high resolutions, all classifiers achieve nearly 100% accuracy because a hyperplane can readily separate the data in a high-dimensional feature space (see Fig. 5b). However, as the input dimensionality decreases, classifier accuracy declines. At extremely low resolution—where the input is reduced to just 4 features—the boundaries between the two classes significantly overlap (see Fig. 5c), causing single-layer linear classifiers, such as the perceptron, to fail in achieving reliable performance. In this regime, the presence of the nonlinear hidden layer with recurrent couplings becomes essential for maintaining classification accuracy. Notably, our nanolaser array performs comparably to nonlinear classifiers, particularly when the input information is highly compressed, thereby demonstrating its capability to process low-dimensional data efficiently using only four nonlinear neurons.

Furthermore, a noticeable drop in accuracy is observed for the 4 × 2 input configuration. This drop, due to a mode switch that occurs above the lasing threshold (a detailed explanation is provided in the Supplementary Note 6), reflects limitations in our setup and analysis procedures. Future implementations could mitigate this effect by imposing additional constraints on the pump distributions or by employing full nonlinear model (Supplementary Note 1) in training procedures.

Discussion

In this work, we propose and experimentally demonstrate a photonic neuromorphic computing architecture utilizing symmetry-protected modes in coupled III–V semiconductor nanolaser arrays. By engineering the optical materials to exploit EP bifurcations, we could excite symmetry-protected zero modes, which serve as robust outputs for classification tasks. Moreover, the intrinsic nonlinear response—arising from gain saturation and the amplitude-phase coupling of the semiconductor nanolasers—combined with the recurrent couplings in the hiddden layer, enables the array to efficiently handle non-convex tasks, such as the XNOR logic gate.

We further evaluated our system using a highly compressed handwritten digit dataset, where severe dimensionality reduction causes significant overlap between classes, thereby necessitating a nonlinear classification scheme beyond single-layer architectures. Our experimental results demonstrate that the nanolaser array maintains reliable accuracy even under extreme input compression, effectively classifying low-resolution data with only four nonlinear neurons. These findings highlight the potential of symmetry-protected optical modes in the nanolaser arrays for energy-efficient, compact, and robust neuromorphic computing systems capable of tackling non-trivial computing tasks. Since the number of final modes in the output layer can, in principle, be relatively small (eventually matching the number of classes in future developments), then the number of coupled units in the nanolaser layer does not need to scale up significantly if restricted to the neural networks’ final readout layers. In other words, we do not require large coupled cavity arrays to realize symmetry protected modes. What can—and should, in most cases—be large is the problem’s dimensionality, which is given, e.g., by the number of input pixels in an image classification problem. While this is in general desirable to ease classification, in some cases the input information is limited. This is what Fig. 6 shows: increasing dimensionality actually improves performance in general, because a hyperplane can always be found to classify data. Still, for limited input data—i.e., highly compressed datasets—the recurrent nanolaser layer outperforms other algorithms like the Perceptron.

The classification tasks addressed in this work can be regarded as minimal yet non-trivial problems that serve as benchmarks. When facing more complex tasks, we would naturally attempt to scale up the nanolaser array to Nx × Ny, where this product could be over one hundred for realistic implementations. Within this planar approach, we may mention an interesting avenue to achieve multilayer architectures: the possibility of having multiple sets of nanocavity arrays connected to one or more common waveguides, which act as tunable links (e.g., via thermal effects) between different hidden layers. In addition, III–V technology also enables potential solutions for signal amplification within those waveguides, if required, for example, in the case of consecutive layers of nanolaser arrays in deep neural networks. A key aspect is the network connectivity, which not only supports optimal problem solving but also reduces hidden layer dimensionality through symmetry-protected laser modes. This is a completely open question and, in our opinion, a most interesting one that deserves further investigation.

Let us finally discuss the performance of our device in terms of robustness, energy consumption and speed. Regarding tolerance to fabrication imperfections, a slight dispersion of cavity-frequencies can be mitigated by the strong inter-cavity couplings, while the impact of coupling disorder can be assumed negligible because of the fundamental symmetry-protection of zero modes36. In terms of energy consumption, our PhC nanolaser threshold is about 3–4 μW average pump power for a single nanolaser operating at 10 MHz repetition rate, and ~ 100 ps pump-pulse duration, which corresponds to 4 mW pump peak-power; besides, the electronic lifetime is about 200 ps. This represents a consumed energy of E0 ~ 1 pJ per pulse, which scales as N × E0 for N-coupled nanolasers. For comparison, state-of-the art electrically pumped PhC nanolasers consume about 1–10 μW of electrical pump power24, leading to an almost three order of magnitude reduction in energy consumption, eventually showcasing the strong potential of these devices. Regarding speed, while 200 ps is the ultimate limit, additional time delays coming from the in-silico matrix multiplications substantially impact the operation time. An interesting prospect is to replace the in-silico linear operations by 2D passive meta-surfaces, enabling the all-optical implementation of these linear transformation functions36.

In conclusion, we have demonstrated that symmetry and/or topologically protected modes in nanolaser arrays—functioning as a readout nonlinear layer within optical ANN architectures—can facilitate classification tasks. This approach naturally accommodates high-dimensional feature spaces and leverages small-to-medium scale coupled laser networks. Crucially, it opens new avenues for addressing complex problems without the need for significantly scaling the number of nonlinear neurons.

Methods

Sample fabrication

The four coupled PhC nanolasers are fabricated in an Indium Phosphide membrane, with four embedded InGa0.17As0.76P quantum wells. The detailed geometric parameters we used in the experiments are: lattice constant, a = 414 nm, the radii of the air hole is r0 = 0.266a. The coupling difference is introduced by modifying the barrier hole size according to rb = (1 + h)r0, with h = −17%, and the thickness of the slab is d = 265 nm.

Experimental setup

In our setup, the pump source is a pulsed laser operating at 783 nm with a 10 MHz repetition rate to minimize thermal effects. The total pump power is then controlled by means of an acousto-optic modulator. The SLM is operated in amplitude-modulation mode, wherein a half-wave plate is rotated by 22.5° to maximize contrast between the pump pattern and the background. Several representative pump patterns are illustrated on the right of Fig. 3. The patterned beam is then projected onto the sample through a microscope objective (100 × magnification, 0.95 N.A.), while the emitted light is collected by the same objective and spectrally resolved using a spectrometer.

Data availability

The experimental data generated in this study have been deposited in the Zenodo database under accession code https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.17064001.

Code availability

The machine learning codes used this study are available from the corresponding author upon request.

References

LeCun, Y., Bengio, Y. & Hinton, G. Deep learning. Nature 521, 436–444 (2015).

Schuman, C. D. et al. A survey of neuromorphic computing and neural networks in hardware. Preprint at https://arxiv.org/abs/1705.06963 (2017).

Marković, D., Mizrahi, A., Querlioz, D. & Grollier, J. Physics for neuromorphic computing. Nat. Rev. Phys. 2, 499–510 (2020).

Schuman, C. D. et al. Opportunities for neuromorphic computing algorithms and applications. Nat. Comput. Sci. 2, 10–19 (2022).

Shastri, B. J. et al. Photonics for artificial intelligence and neuromorphic computing. Nat. Photonics 15, 102–114 (2021).

Wetzstein, G. et al. Inference in artificial intelligence with deep optics and photonics. Nature 588, 39–47 (2020).

Totović, A. R., Dabos, G., Passalis, N., Tefas, A. & Pleros, N. Femtojoule per MAC neuromorphic photonics: an energy and technology roadmap. IEEE J. Sel. Top. Quantum Electron. 26, 1–15 (2020).

Li, G. H. et al. Deep learning with photonic neural cellular automata. Light.: Sci. Appl. 13, 283 (2024).

Shen, Y. et al. Deep learning with coherent nanophotonic circuits. Nat. Photonics 11, 441–446 (2017).

Bandyopadhyay, S. et al. Single-chip photonic deep neural network with forward-only training. Nat. Photon. 18, 1335–1343 (2024).

De Lima, T. F. et al. Machine learning with neuromorphic photonics. J. Lightwave Technol. 37, 1515–1534 (2019).

Yildirim, M., Dinc, N. U., Oguz, I., Psaltis, D. & Moser, C. Nonlinear processing with linear optics. Nat. Photonics 18, 1076–1082 (2024).

Xia, F. et al. Nonlinear optical encoding enabled by recurrent linear scattering. Nat. Photonics 18, 1067–1075 (2024).

Wanjura, C. C. & Marquardt, F. Fully nonlinear neuromorphic computing with linear wave scattering. Nat. Phys. 20, 1434–1440 (2024).

Ren, K., Li, C., Fang, Z. & Feng, F. Recent developments of electrically pumped nanolasers. Laser Photonics Rev. 17, 2200758 (2023).

Brunner, D., Soriano, M. C., Mirasso, C. R. & Fischer, I. Parallel photonic information processing at gigabyte per second data rates using transient states. Nat. Commun. 4, 1364 (2013).

Guo, X. X. et al. High-speed neuromorphic reservoir computing based on a semiconductor nanolaser with optical feedback under electrical modulation. IEEE J. Sel. Top. Quantum Electron. 26, 1–7 (2020).

Skalli, A. et al. Photonic neuromorphic computing using vertical cavity semiconductor lasers. Optical Mater. Express 12, 2395–2414 (2022).

Chen, Z. et al. Deep learning with coherent VCSEL neural networks. Nat. Photonics 17, 723–730 (2023).

Parto, M., Hayenga, W. E., Marandi, A., Christodoulides, D. N. & Khajavikhan, M. Nanolaser-based emulators of spin Hamiltonians. Nanophotonics 9, 4193–4198 (2020).

Park, H.-G. et al. Electrically driven single-cell photonic crystal laser. Science 305, 1444–1447 (2004).

Nozaki, K., Kita, S. & Baba, T. Room temperature continuous wave operation and controlled spontaneous emission in ultrasmall photonic crystal nanolaser. Opt. Express 15, 7506–7514 (2007).

Crosnier, G. et al. Hybrid indium phosphide-on-silicon nanolaser diode. Nat. Photonics 11, 297–300 (2017).

Dimopoulos, E. et al. Electrically-driven photonic crystal lasers with ultra-low threshold. Laser Photonics Rev. 16, 2200109 (2022).

Dimopoulos, E. et al. Experimental demonstration of a nanolaser with a sub-μA threshold current. Optica 10, 973–976 (2023).

Ma, R.-M. & Oulton, R. F. Applications of nanolasers. Nat. Nanotechnol. 14, 12–22 (2019).

Jeong, K.-Y. et al. Recent progress in nanolaser technology. Adv. Mater. 32, 2001996 (2020).

Lu, L., Joannopoulos, J. D. & Soljačić, M. Topological photonics. Nat. Photonics 8, 821–829 (2014).

Ota, Y. et al. Active topological photonics. Nanophotonics 9, 547–567 (2020).

Feng, L., El-Ganainy, R. & Ge, L. Non-Hermitian photonics based on parity–time symmetry. Nat. Photonics 11, 752–762 (2017).

Feng, X. et al. Non-Hermitian hybrid silicon photonic switching. Nat. Photon. 19, 264–270 (2025).

Malzard, S., Poli, C. & Schomerus, H. Topologically protected defect states in open photonic systems with non-Hermitian charge-conjugation and parity-time symmetry. Phys. Rev. Lett. 115, 200402 (2015).

Qi, B., Zhang, L. & Ge, L. Defect states emerging from a non-Hermitian flatband of photonic zero modes. Phys. Rev. Lett. 120, 093901 (2018).

Rivero, J. D. & Ge, L. Chiral symmetry in non-Hermitian systems: product rule and Clifford algebra. Phys. Rev. B 103, 014111 (2021).

Ge, L. Symmetry-protected zero-mode laser with a tunable spatial profile. Phys. Rev. A 95, 023812 (2017).

Tirabassi, G., Ji, K., Masoller, C. & Yacomotti, A. M. Binary image classification using collective optical modes of an array of nanolasers. APL Photonics 7, 090801 (2022).

Torrejon, J. et al. Neuromorphic computing with nanoscale spintronic oscillators. Nature 547, 428–431 (2017).

Romera, M. et al. Vowel recognition with four coupled spin-torque nano-oscillators. Nature 563, 230–234 (2018).

Sun, L. et al. In-sensor reservoir computing for language learning via two-dimensional memristors. Sci. Adv. 7, eabg1455 (2021).

Hedir, M. et al. Probing non-Hermitian zero modes in a nanophotonic trimer: from nonuniform to twisted coupling. Phys. Rev. A 110, 043515 (2024).

Ji, K. et al. Tracking exceptional points above the lasing threshold. Nat. Commun. 14, 8304 (2023).

Graupe, D. Principles of Artificial Neural Networks (World Scientific, Singapore, 2013).

Fisher, R. A. The use of multiple measurements in taxonomic problems. Ann. Eugen. 7, 179–188 (1936).

Taha, A. A. & Hanbury, A. Metrics for evaluating 3D medical image segmentation: analysis, selection, and tool. BMC Med. Imaging 15, 1–28 (2015).

Acknowledgements

L.G. acknowledges support by the National Science Foundation (NSF) under Grants No. PHY-1847240 and No. DMR-2326698. C.M. acknowledges the support of Ministerio de Ciencia, Innovación y Universidades (PID2024-160573NB-I00); Institució Catalana de Recerca i Estudis Avançats (Academia); Agencia de Gestió d’Ajuts Universitaris i de Recerca (AGAUR, SGR2021 00606); European Office of Aerospace Research and Development (FA8655-24-1-7022). G.T. acknowledges the support of the Serra Húnter Programme. This work is partially supported by the French National Research Agency (ANR), Grant No ANR-22-CE24-0012-01, by the RENATECH network, and by the “Grand Programme de Recherche” (GPR) LIGHT.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

A.M.Y. conceived the project. A.M.Y. and C.M. supervised the project. G.T. and K.J. performed the simulations and the experiments, with feedback from C.M., L.G., and A.M.Y. K.J. and A.M.Y. wrote the main part of the manuscript. L.G., C.M., and G.T. contributed to the manuscript preparation and revision. All authors reviewed and approved the final version of the paper.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Peer review

Peer review information

Nature Communications thanks the anonymous reviewers for their contribution to the peer review of this work. A peer review file is available.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Ji, K., Tirabassi, G., Masoller, C. et al. Photonic neuromorphic computing using symmetry-protected zero modes in coupled nanolaser arrays. Nat Commun 16, 9203 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-025-64252-x

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-025-64252-x