Abstract

Patients with chronic kidney disease (CKD) are recognized as a higher risk group for cardiovascular disease (CVD) due to various traditional risk factors, kidney-specific factors, and comorbidities, which have recently attracted significant attention. However, the long-term risk of acute CVD events such as sudden cardiac death (SCD) in CKD patients is unclear. Using the UK Biobank and Changsha cohorts, we find that CKD is associated with an increased risk of SCD. Patients with early-stage CKD, especially those with advanced CKD, faced an elevated risk of SCD. Furthermore, through proteomic analyses of the UK Biobank and Framingham Offspring Cohort, we identify five candidate proteins (NTproBNP, ANGPT2, FGF23, DTNB, and SEPTIN8) linked to SCD risk in CKD patients. Here, we show that patients with CKD have an increased risk of SCD in the long term, underscoring the imperative for strategies that address both cardiovascular risk and renal function in this population.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Chronic kidney disease (CKD) has become a serious public health problem worldwide, and it is projected to be the 5th most common cause of years of life lost (YLL) globally by 20401,2. As one of the major risk factors for cardiovascular disease (CVD), CKD causes significantly greater cardiovascular hazards than its own, with >50% of CKD patients developing cardiovascular complications and, eventually, experiencing a shortened life expectancy3,4,5. Thus, given the multifaceted burden of risk factors for cardiovascular and kidney disease, patients with CKD are considered to represent the “Perfect Storm” of cardiometabolic risk and tend to have poor outcomes6. Moreover, in addition to cardiometabolic disorders, the potential risks of treatments for CKD patients should not be underestimated. Some treatments, such as dialysis, are even thought to exacerbate metabolic disorders in advanced CKD patients, resulting in increased risk of CVD and mortality7,8,9.

Sudden cardiac death (SCD), the leading cause of CVD death, accounts for approximately half of all deaths10. Particularly, This burden is pronounced in CKD and chronic kidney failure patients, where, ion imbalances and sympathetic overactivity exacerbate electrical instability, arrhythmias, and cardiac arrest, ultimately leading to hemodynamic failure and SCD11. Arising from the interplay of these acute events and underlying disease, >20% of advanced CKD patients succumb to SCD12. Recent studies have reported that patients with early-stage CKD may also be at high risk for SCD13. However, only a few small-sample studies, focusing on specific populations such as the elderly, women, or comorbidities in CKD patients, have explored the risk of SCD in CKD14,15,16,17. The SCD risk across different stages of CKD in the general population remains unclear. Moreover, given the rapid and fatal onset of SCD, identifying the potential biomarkers for CKD patients holds significant clinical potential and importance.

Hence, we conducted this study in three independent diverse cohorts: (1) an exploration cohort to identify the association between CKD and the risk of SCD; (2) a validation cohort to confirm the findings from the exploration cohort; and (3) the Framingham Offspring Cohort to identify circulating proteins that mediate the risk of SCD in CKD patients.

Results

Population characteristics

The baseline characteristics of the two cohorts are provided in Table 1. The median age of 349,648 participants from the exploration cohort was 57 years old (IQR, 49–63 years), and 48.91% were male. In total, 4.83% of the participants had a history of diabetes, 7.12% had hypertension, and 10.92% had a history of CVD. The median age of 129,279 participants in the validation cohort was 40 years old (IQR, 31–50 years), and 76,170 (58.92%) were male. The prevalence of diabetes, hypertension, and CVD in these participants was 8.66%, 16.90%, and 15.82%, respectively. Compared with those in the exploration cohort, the participants in the validation cohort were younger, more likely to be male, and more likely to have a history of diabetes or hypertension.

The characteristics of the participants in these cohorts grouped on the basis of CKD status at baseline are shown in Supplementary Tables 1 and 2. In the exploration cohort, a total of 18,410 (5.27%) participants had CKD. Compared to those without CKD, CKD patients were older, had a higher proportion of males (52.36%), and the greater prevalence of obesity (74.62%). Additionally, the prevalence of diabetes, hypertension, and CVD was significantly higher in these participants. In the validation cohort, 2475 (1.92%) participants were diagnosed with CKD at baseline. These participants were significantly older, and the proportion of males was higher comparing with non-CKD. There were significant differences in all baseline characteristics between the CKD group and the non-CKD group both in the exploration cohort and the validation cohort.

Association between CKD and SCD risk

In the exploration cohort, during a median follow-up period of 13.63 years (IQR, 12.88–14.35 years), a total of 6815 (1.9%) participants experienced SCD. In the validation cohort, we observed 154 SCD events at a median follow-up of 8 years. Stratified Kaplan–Meier (KM) curve analysis revealed a significantly greater cumulative incidence of SCD in participants with CKD than in those without CKD in both the exploration cohort and the validation cohort (Plog-rank < 0.001, Fig. 1). In the exploration cohort, the adjusted hazard ratio (HR) for the risk of SCD among CKD patients was 1.81 (with respect to non-CKD patients; 95% CI, 1.68–1.96) in Model 1, whereas the adjusted HR was 1.33 (95% CI, 1.22–1.45) in Model 2. In the validation cohort, the adjusted HRs of SCD among CKD patients were 2.08 (95% CI, 1.37–3.17) and 1.87 (95% CI, 1.05–3.33) in Model 1 and Model 2, respectively (Fig. 2). Besides, when including potential cases by extending SCD-defined ICD-10 codes, the results were robust in the exploration cohort (Supplementary Table 3). These results indicated that in both cohorts, CKD patients were at greater risk of developing SCD.

The central markers indicate hazard ratios, and the error bars represent 95% confidence intervals. In the exploration cohort (n = 349,648, SCD = 6815), model 1 was adjusted for age, sex, and ethnic; model 2 was adjusted for age, sex, ethnic, obesity, eGFR, smoking, drinking, household income, exercise, hypertension, diabetes, hyperlipidemia, CVD, medication for cholesterol, medication for BP, and medication for diabetes. In the validation cohort (n = 129,279, SCD = 154), model 1 was adjusted for age, sex; model 2 was adjusted for age, sex, obesity, eGFR, smoking, drinking, exercise, hypertension, diabetes, hyperlipidemia, CVD, medication for cholesterol, medication for BP, and medication for diabetes. Source data are provided as a Source data file. No Number, HR hazard ratio, CI confidence interval, CKD chronic kidney disease, SCD sudden cardiac death.

When a subanalysis for participants who died due to SCD, the adjusted HR among CKD patients was 2.76 (relative to non-CKD patients; 95% CI, 2.10–3.62) in Model 1. Following full confounder adjustment, the adjusted HR was 1.63 (95% CI 1.19–2.25) in Model 2 (Supplementary Table 4). In addition, when the data of only participants diagnosed with sudden cardiac arrest (SCA) were analysed, the association between CKD and the risk of SCA remained significant both in Model 1 (HR 1.79, 95% CI 1.65–1.94) and Model 2 (HR 1.32, 95% CI 1.21–1.44) (Supplementary Table 5). The above results revealed that CKD increased the risk of both SCD and SCA.

SCD risk for different CKD stages

The results of the Cox proportional hazard model analyses for Model 1 showed that patients in all CKD stages including CKD stages 1–3 (HR 1.77, 95% CI 1.53–2.04), stage 4 (HR 7.46, 95% CI 5.40-12.38), and stage 5 (HR 6.15, 95% CI 4.63–8.17) were at greater risk of SCD. Following adjustment for all considered confounders, the observed associations persisted, including for participants with CKD stages 1–3 (HR 1.31, 95% CI 1.13–1.52), stage 4 (HR 4.10, 95% CI 2.46–6.82), and stage 5 (HR 3.09, 95% CI 2.32–4.12) (Fig. 3). These findings indicated that individuals with both early and especially advanced stage (stages 4 and 5) CKD have a more pronounced risk of SCD than those without CKD.

The central markers indicate hazard ratios, and the error bars represent 95% confidence intervals. In this analysis, CKD staging was performed based on the ICD-10 codes and the eGFR levels of patients with CKD. Number of participants stratified by CKD stage: non-CKD (n = 344,077), CKD stage 1–3 (n = 4118), CKD stage 4 (n = 111), CKD stage 5 (n = 431). Model 1 was adjusted for age, sex, and ethnic; Model 2 was adjusted for age, sex, ethnic, obesity, smoking, drinking, household income, exercise, hypertension, diabetes, hyperlipidemia, CVD, medication for cholesterol, medication for BP, and medication for diabetes. Source data are provided as a Source data file. No. Number, HR hazard ratio, CI confidence interval, CKD chronic kidney disease.

Stratified and sensitivity analyses

Stratified analyses of the exploration cohort revealed that baseline age, sex, hypertension status, diabetes status, and history of CVD affected the association between CKD and the risk of incident SCD (all P-interaction < 0.05, Supplementary Table 6). Specifically, the risk of SCD was significantly greater in males (HR 1.39, 95% CI 1.25–1.54) than in females (HR 1.26, 95% CI 1.08–1.47) and in CKD participants with hypertension (HR 1.36, 95%CI 1.16–1.59), diabetes (HR 1.49, 95% CI 1.23–1.81), or CVD (HR 1.46, 95%CI 1.25-1.69).

The association between CKD and an increased risk of SCD was shown to be robust in sensitivity analyses of the exploration cohort (Supplementary Tables 7–9). The results were consistent with those of the main analysis after sequentially excluding participants with certain relevant comorbidities, such as CVD (N = 38,185), hypertension, diabetes or hyperlipidaemia (N = 40,601), and those with end-stage renal disease who require dialysis (N = 65) at baseline. To explain the long-term relationship between CKD and SCD, we excluded participants who had been followed up only for <1 year (N = 740) and <3 years (N = 3310); the results were again similar to the findings of the main analysis. Considering the interactions between hypertension, diabetes, and CVD and CKD for the risk of SCD identified in the stratified analyses, we changed the adjusted covariates and developed several sensitivity models; nevertheless, the results remained robust to these adjustments. Moreover, the associations remained robust following a restriction of the definition of CKD patients to only those with relevant diagnostic records and eGFR<60 mL/min/1.73 m2 (N = 4698).

Circulating protein analysis

In the exploration cohort, 1250 differentially expressed proteins (FDR-adjusted P < 0.05) were identified between CKD and non-CKD patients (Supplementary Data 1), whereas 1335 proteins were found to be significantly associated with CKD following Bonferroni correction in multiple linear regression analyses (Supplementary Data 2). In the Cox proportional hazard model analysis, 92 proteins associated with SCD were identified (Supplementary Data 3). Among these proteins, 38 overlapping proteins were included in the analysis (Supplementary Fig. 3A). These 38 overlapping proteins are differentially expressed, positively correlated with CKD, and associated with an increased risk of SCD. Next, we selected five candidate proteins from among these 38 proteins with an L1-penalized least absolute shrinkage and selection operator (LASSO) Cox regression model, including N-terminal pro-brain natriuretic peptide (NT-proBNP), angiopoietin 2 (ANGPT2), fibroblast growth factor 23 (FGF23), dystrobrevin beta (DTNB) and septin 8 (SEPTIN8) (Supplementary Fig. 3B, C). Finally, the associations of the above five selected proteins with SCD risk in patients with CKD were assessed (Fig. 4). Higher levels of all five proteins—NT-proBNP (HR 1.48, 95% CI 1.23–1.77), ANGPT2 (HR 2.25, 95% CI 1.33–3.81), FGF23 (HR 2.27, 95% CI 1.39–3.71), DTNB (HR 2.64, 95% CI 1.30–5.39) and SEPTIN8 (HR 5.90, 95% CI 2.30–15.11)—were associated with an increased risk of SCD in Model 2.

The central markers indicate hazard ratios, and the error bars represent 95% confidence intervals. Number of participants with avaliable proteomic data: NTproBNP (n = 2096, SCD = 94), ANGPT2 (n = 2167, SCD = 105), FGF23 (n = 2049, SCD = 89), DTNB (n = 1667, SCD = 72), SEPTIN8 (n = 1659, SCD = 69). Model 1 was adjusted for age, sex and ethnic; Model 2 was adjusted for age, sex, ethnic, obesity, eGFR, uACR, smoking, drinking, household income, exercise, hypertension, diabetes, hyperlipidemia, CVD, medication for cholesterol, medication for BP, and medication for diabetes. Source data are provided as a Source data file. No. Number, HR hazard ratio, CI confidence interval, CKD chronic kidney disease, NTproBNP N-terminal pro-brain natriuretic peptide, ANGPT2 angiopoietin 2, FGF23 fibroblast growth factor 23, DTNB dystrobrevin beta, SEPTIN8 septin 8.

In the proteomic analysis replication cohort from Framingham Offspring Cohort, due to differences in the proteomic panels from those in the exploration cohort, data were available only for FGF23 and NT-proBNP. In Model 1, higher levels of both FGF23 and NT-proBNP were significantly associated with an increased risk of CVD. However, after further adjustment for the additional factors in Model 2, including the eGFR, only an increased NT-proBNP level remained significantly associated with an elevated risk of CVD (HR 1.87, 95% CI 1.28–2.74, P < 0.001). An increased level of FGF23 was still associated with an increased risk of CVD, but this association was no longer significant following the adjustments in Model 2 (HR 1.66, 95% CI 0.95–2.88, P = 0.075) (Supplementary Fig. 4).

Discussion

Using two independent large-scale cohorts, we identified an elevated risk of SCD in patients with CKD in the long term. Moreover, patients with both early and especially advanced stage CKD had a significantly greater risk of experiencing SCD than non-CKD patients. Furthermore, by combining the circulating protein data of the exploration cohort, we identified NT-proBNP, ANGPT2, FGF23, DTNB, and SEPTIN8 as candidate proteins that mediate the association between CKD and SCD. Protein replication analysis with the data from the Framingham Offspring Cohort supported the promising predictive capabilities of NT-proBNP and FGF23 for incident SCD among patients with CKD (Fig. 5). These findings provide significant evidence supporting the management and prevention of acute cardiovascular events in patients with CKD.

In recent decades, there has been growing interest in the risk of cardiovascular complications in patients with CKD5,18,19. Numerous studies have investigated the risks of coronary heart disease (CHD), heart failure, stroke, and atrial fibrillation in patients with CKD20,21,22,23. SCD, a severe type of CVD that occurs suddenly and unpredictably, poses a greater burden of premature death than any other individual CVD24. Despite the significant health burden caused by SCD, the risk of SCD in patients with CKD has received relatively little attention. In a prospective analysis that included end-stage renal disease (ESRD) patients requiring long-term dialysis treatment, SCD was found to account for 24% of total deaths17. The results of another study in patients with advanced CKD (e.g., stage 4 to 5) who were not yet on dialysis revealed that even in these patients, SCD was a common cause of death25. However, the focus of these studies was only on the incidence of SCD in patients with advanced kidney disease, so the risk of SCD specifically attributable to advanced CKD remains inadequately understood. The results of our study extended previous findings and revealed that the risk of SCD in patients with stage 5 CKD was 3.09-fold (95% CI, 2.32-4.12) greater than that in patients without CKD. Our findings underscore the critical need for effective prevention and management strategies for mitigating the risk of SCD in patients with advanced CKD. For this high-risk population, clinical approaches such as routine monitoring with 12-lead electrocardiograms and echocardiography for assessing ventricular diastolic and systolic function could play a key role in reducing the risk of SCD.

Given that cardiovascular morbidity and mortality in CKD patients often occur before progression to ESRD and the initiation of dialysis, the risk of SCD should not be overlooked even in patients with early-stage and moderate CKD. The majority of previous studies involved patients with serious cardiovascular conditions, such as CHD and heart failure, and the associations between renal dysfunction and SCD risk were explored in these susceptible populations14,15,26,27. However, definitive evidence on whether reduced renal function independently contributes to the risk of developing SCD is lacking. Our study investigates the risk of SCD in patients with CKD from the early to moderate stages using 2 independent large sample cohorts. By integrating the findings from the primary and multiple sensitivity analyses, our investigation revealed that reduced renal function across the early-moderate and advanced stages was independently associated with an elevated risk of SCD, regardless of the presence of CVD.

Traditionally, the biomarkers used to predict SCD risk have included electrocardiographic findings and left ventricular function. With advancements in proteomics technology, the use of circulating proteins to predict CVD risk holds considerable promise. In our analysis of circulating proteins, we identified several that potentially mediate the risk of SCD in CKD patients, including FGF23 and NT-proBNP. FGF23, a phosphatonin hormone critical for regulating phosphorus and calcium homeostasis, has been extensively studied for its role in both renal dysfunction and CVD28,29,30,31,32. Together with its co-FGF receptor-stimulating protein, the transmembrane ɑ-Klotho, FGF23 and ɑ-Klotho form a signalling axis that serves as the main pathogenic factor adversely affecting the outcomes of CKD patients, including ESRD, CVD, and death28,29,30. Additionally, NT-proBNP has long been established as a cardiac biomarker, especially for heart failure33. Notably, the findings of a study involving 230 dialysis-dependent patients with ESRD suggested that serum NT-proBNP could serve as an alternative to echocardiography for identifying patients at risk of SCD17. Given the promising nature of these proteins as biomarkers for the risk of CVD in CKD patients, further research is warranted to investigate the underlying mechanisms by which FGF23 and NT-proBNP predict SCD and the therapeutic potential of targeting these proteins.

The notable strengths of this study include the use of two large, independent cohorts that jointly included more than 450,000 participants, allowing both appropriate analytical power and independent replication of the main findings of the initial cohort, as well as the ability to conduct a series of sensitivity analyses to validate the robustness of our findings. Furthermore, in our analysis of data on circulating proteins, we identified candidate predictive proteins for the risk of SCD in patients with CKD; these proteins could have significant implications for future clinical considerations in the risk prediction and management of CKD patients.

However, several limitations should also be considered. First, consistent with most existing studies, our study used ICD-10 codes to define SCD, which may have led to missed cases compared to the gold standard definition. Further research and clinical efforts are needed to incorporate physician-adjudicated chart reviews for accurately identifying SCD cases. Second, participants in the UKB and Changsha cohorts tended to be young or middle-aged at baseline; notably, in the present study, the prevalence of CKD and SCD was lower than that in the general population. However, our follow-up period was sufficiently long, and our population size was large enough to be representative. In addition, owing to the lack of availability of detailed data on treatments for the CKD patients, we did not consider different types of medication, durations of use, or dosages when conducting our analyses. Future studies should include additional representative CKD patients to validate our findings and provide further insights for CVD risk management in CKD patients.

In conclusion, the findings obtained in our study suggest a greater SCD risk in CKD patients, particularly advanced CKD patients and males. FGF23 and NT-proBNP show potential as valuable candidate proteins for predicting and managing SCD risk among CKD patients. These findings demonstrate that, despite improvements to clinical management strategies including renal replacement therapy and antihypertensive and lipid-lowering drug administration, the risk of severe CVD in CKD patients persists. Future research should focus on treatments for CKD patients aimed at reducing the dual risk of renal and cardiovascular complications.

Methods

Study population

Following the exclusion of individuals with missing information on relevant covariates and patients with a diagnosis of sudden cardiac arrest (SCA) prior to baseline, the exploration cohort ultimately consisted of 349,648 participants from the UK Biobank (UKB) (Supplementary Fig. 1). Data for the participants in the validation cohort were retrieved from the Changsha cohort, a group of individuals involved in an ongoing, large-scale longitudinal cohort study in Hunan, China34,35. Mortality information for the participants in the Changsha cohort was obtained from the National Mortality Surveillance System (NMSS), which is operated by the Centre of Disease Control and Prevention in Hunan Province. The unique ID number in the resident’s health record was matched with the NMSS to obtain the time of death, cause of death, and International Classification of Diseases 10th Edition (ICD-10) code. Since participant death information in the NMSS was tracked from 1 January 2009 to 24 February 2021, the 129,279 participants from the Changsha cohort aged ≥18 years with complete, available information on important covariates (age, sex), renal function tests, and mortality tracked from 1 January 2009 to 31 December 2020 were included in this study. In addition, to ensure that the renal function tests were sufficiently robust, we excluded individuals in the Changsha cohort who had data from only one physical examination (Supplementary Fig. 2). The proteomic analysis was replicated with data from participants in the Framingham Offspring Study. We included CKD participants attending the seventh Heart Study visit and who underwent proteomic testing. Detailed descriptions of the UKB, Changsha cohort, and Framingham Offspring Study are given in the Supplementary Methods, Section 1. All participants provided written informed consent. The UKB study protocol was approved by the North West Multi-centre Research Ethics Committee (11/NW/0382), and the study in Changsha cohort was approved by the institutional review board of the Third Xiangya Hospital of Central South University (no. 23309).

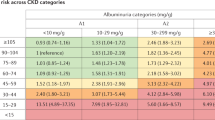

CKD definition

According to the 2021 CKD-EPI Race-Free Equation36, we used serum creatinine to calculate the baseline eGFR and urine creatinine and microalbumin to calculate the urine albumin–creatinine ratio (uACR) (as detailed in the Supplementary Methods, Section 2). Individuals in the exploration cohort were considered to have CKD if they met any of the following criteria: 1) a diagnosis of CKD according to the ICD-10 codes; 2) a baseline eGFR<60 mL/min/1.73 m2; and 3) a baseline uACR≥30 mg/g. Owing to the limited data availability, in the validation cohort and Framingham offspring cohort, we considered only the participants with an eGFR <60 mL/min/1.73 m2 to have CKD. To explore the risk of SCD in patients with different CKD stages, we divided the participants into four groups on the basis of the ICD-10 codes and the eGFR level of the patients with CKD: non-CKD, CKD stages 1–3, CKD stage 4, and CKD stage 5 (Supplementary Information).

Outcome definitions

For the exploration cohort, the outcome of this study was SCD (defined according to the relevant ICD-10 codes; Supplementary Methods, Section 3), including both patients who diagnosed with SCA and those who died as a result of SCD. The participants were followed from baseline until the date of first SCA, death, or the last follow-up (Oct 31, 2022). In the validation cohort, the outcome was mortality due to SCD. Patients for whom the primary or secondary cause of death was listed as SCD or cardiac arrest were considered to have SCD. The subjects were followed from baseline until the date of death or last follow-up (31 December 2020). In the proteomic analysis replication cohort, with the limited sample size, CVD mortality was used as the primary outcome of interest in Framingham Offspring Study.

Data collection

In the exploration cohort, information on socioeconomic status (average household income) and lifestyle factors (smoking history, alcohol use, and use of medications for cholesterol, blood pressure, and diabetes) was collected with a self-administered questionnaire. Demographic information on age, sex, ethnicity, body mass index (BMI), systolic blood pressure (SBP), diastolic blood pressure (DBP), total cholesterol (TC), and serum creatinine was collected by trained nurses during the baseline assessment at the visit to the corresponding centre. A history of hypertension, diabetes, and hyperlipidaemia in participants at baseline was obtained on the basis of the corresponding ICD-10 codes. Detailed descriptions of the covariates of these cohorts are provided in the Supplementary Information.

Plasma proteomics

In the original UKB cohort, over 50,000 participants in UKB were randomly selected to undergo proteomic profiling of their blood plasma samples acquired at baseline from 2007 to 2010. The plasma samples were transported to the Olink Analysis Service in Sweden, where 2923 unique proteins were measured using the antibody-based Olink Explore 3072 proximity extension assay (PEA)37,38,39. The proteins measured spanned four panels: cardiometabolic, inflammation, neurology, and oncology proteins. Stringent quality control ensured inter- and intra-panel coefficients of variation below 20 % and 10 %, respectively. Upon conducting quality control procedures, protein levels were converted into normalized protein expression (NPX) values. For each protein level, values greater than five times the median absolute deviation from the median were removed from our analyses. We ultimately included the data of 52,687 UKB participants who underwent complete baseline plasma proteomic profiling. In the proteomic analysis replication cohort, the stored EDTA plasma samples acquired from the seventh (1998–2001) Heart Study visit of the Framingham Offspring Study were similarly sent to the Olink Analysis Service for proteomics40. Fasting plasma samples collected during the Offspring 7th Examination (stored at −80 °C) were analyzed for protein biomarkers using the antibody-based Olink Explore proximity extension assay. Protein expression levels are reported as NPX values, where a one-unit increase represents a twofold change in protein concentration.

Statistical analysis

The baseline characteristics of both the CKD and non-CKD participants are presented as the medians with interquartile ranges (IQRs) for continuous variables, and the frequencies (percentages) for categorical variables. The differences between the groups were assessed with the χ2 test or the Mann‒Whitney U test, as appropriate.

To assess outcome disparities between participants with and without CKD, we performed stratified Kaplan‒Meier (KM) analysis followed by the log-rank test to compare KM curves. Cox proportional hazard models were subsequently constructed to estimate the association between CKD, CKD stages, and the risk of incident SCD. In the exploration cohort, two models were constructed: one adjusted for age, sex, and ethnicity (Model 1) and another adjusted for age, sex, and ethnicity plus obesity, lifestyle factors, socioeconomic status, history of hypertension, diabetes, hyperlipidaemia, CVD, medication for cholesterol, blood pressure, and diabetes, and eGFR (Model 2). In the validation cohort, Model 1 was adjusted for age and sex (since >90% of the validation cohort is Han Chinese, adjusting for ethnicity would have served no purpose), and Model 2 was adjusted for obesity, lifestyle factors, history of hypertension, diabetes, hyperlipidaemia, and medication for cholesterol, blood pressure, and diabetes, and eGFR. Besides, to reduce the potential impact of missed SCD, we conducted an additional analysis in the exploration cohort using these expanded ICD-10 codes, which were proposed by previous researchers41. We also separately restricted the outcomes to death due to SCD and diagnosis with SCA for Cox proportional hazard model analysis in the exploration cohort.

Additionally, we conducted stratified analyses to investigate potential effects of age (≤60 years or >60 years), sex (male or female), the presence of hypertension (yes or no), diabetes (yes or no), hyperlipidemia (yes or no), and a history of CVD (yes or no). To ensure the reliability of our findings, we conducted several sensitivity analyses in the exploration cohort, separately: (1) excluding participants with CVD; (2) excluding participants with preexisting conditions such as hyperlipidaemia, diabetes, or hypertension; (3) excluding participants with diagnosed ESRD or who were dependent on dialysis; (4) excluding individuals who achieved either outcome within the first year after baseline; (5) excluding individuals who achieved either outcome within 3 years after baseline; (6) changing the confounders in the final model; and (7) restricting the definition of CKD to a diagnosis in the medical records and the eGFR.

Circulating protein analysis

A 3-step study combined with observational analysis was conducted in 36,530 participants with available circulating protein data in the exploration cohort. First, we examined the differentially expressed proteins between non-CKD patients (N = 34,250) and CKD patients (N = 2280) with the t-test. If a protein was absent in >50% of the population, the mean value of that protein was used. If the protein was absent in >80% of the population, it was excluded from the analysis. We also constructed a linear regression model and Cox proportional hazards model to separately identify CKD- and SCD-related proteins. We then overlapped the three sets of proteins to obtain our initial protein list of interest. Second, we applied a penalized Cox proportional hazards model with adaptive LASSO with the minimized mean cross-validated error criterion to select the optimal biomarkers among the overlapping significant proteins from CKD patients with all overlapping protein data. Finally, we constructed Cox proportional hazard models with the data from these CKD patients to examine the associations of candidate proteins selected in the LASSO regression with the risk of SCD. Moreover, in CKD patients whose protein data were available from the proteomic analysis replication cohort, we constructed Cox proportional hazards models to validate the candidate proteins identified in the exploration cohort.

All statistical analyses were conducted using Stata software version 17.0 and R version 4.4.1. A two-sided P value < 0.05 was considered statistically significant, whereas the statistically significant result was determined by an adjusted P value < 0.05 using Benjamini and Hochberg false discovery rate (FDR) and Bonferroni-corrected P value < 0.05/2923 for multiple testing in the analysis of circulating proteins.

Reporting summary

Further information on research design is available in the Nature Portfolio Reporting Summary linked to this article.

Data availability

The data of UKB for this research are obtained from the UK Biobank and are publicly available to approved researchers for health-related research (https://www.ukbiobank.ac.uk/enable-your-research/apply-foraccess). This research has been conducted using the UKB Resource under Application Number 75283. The data in Framingham Heart Study (FHS) Research Materials obtained from the NHLBI Biologic Specimen and Data Repository Information Coordinating Center does not necessarily reflect the opinions or views of the FHS, or the NHLBI. The data are available to qualified researchers upon application and approval through BioLINCC (https://biolincc.nhlbi.nih.gov/ login/? next = / requests/type/ framoffspring/, Application Number 14307). Due to ethical and legal restrictions, the clinical data of Changsha cohort are not publicly available. Data of Changsha cohort are available from the corresponding author (Yao Lu, luyao0719@163.com) by reasonable request. The process involves submitting a proposal to the management team for approval. Upon approval, data will be released following the execution of a data access agreement. The standard response timeframe for information access requests is 20 working days from the date of receipt. Source data are provided with this paper.

Code availability

Relevant analyses in this study were conducted using Stata software version 17.0 (https://www.stata.com/) and R version 4.4.1 (https://www.r-project.org). No customized code was developed.

References

Foreman, K. J. et al. Forecasting life expectancy, years of life lost, and all-cause and cause-specific mortality for 250 causes of death: reference and alternative scenarios for 2016-40 for 195 countries and territories. Lancet 392, 2052–2090 (2018).

Francis, A. et al. Chronic kidney disease and the global public health agenda: an international consensus. Nat. Rev. Nephrol. 20, 473–485 (2024).

Global, regional, and national burden of chronic kidney disease, 1990–2017: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2017. Lancet 395, 709–733 (2020).

Matsushita, K. et al. Estimated glomerular filtration rate and albuminuria for prediction of cardiovascular outcomes: a collaborative meta-analysis of individual participant data. Lancet Diabetes Endocrinol. 3, 514–525 (2015).

Jankowski, J., Floege, J., Fliser, D., Böhm, M. & Marx, N. Cardiovascular disease in chronic kidney disease: pathophysiological insights and therapeutic options. Circulation 143, 1157–1172 (2021).

Towler, D. A. Chronic kidney disease: the “perfect storm” of cardiometabolic risk illuminates genetic diathesis in cardiovascular disease. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 62, 799–801 (2013).

McIntyre, C. W. et al. Hemodialysis-induced cardiac dysfunction is associated with an acute reduction in global and segmental myocardial blood flow. Clin. J. Am. Soc. Nephrol. 3, 19–26 (2008).

Morales, M. A. et al. Signal-averaged ECG abnormalities in haemodialysis patients. Role of dialysis. Nephrol. Dial. Transpl. 13, 668–673 (1998).

Aoki, J. & Ikari, Y. Cardiovascular disease in patients with end-stage renal disease on hemodialysis. Ann. Vasc. Dis. 10, 327–337 (2017).

Wong, C. X. et al. Epidemiology of sudden cardiac death: global and regional perspectives. Heart Lung Circ. 28, 6–14 (2019).

Di Lullo, L. et al. Sudden cardiac death and chronic kidney disease: From pathophysiology to treatment strategies. Int J. Cardiol. 217, 16–27 (2016).

Genovesi, S. et al. Sudden cardiac death in dialysis patients: different causes and management strategies. Nephrol. Dial. Transpl. 36, 396–405 (2021).

Svane, J. et al. Nationwide study of mortality and sudden cardiac death in young persons diagnosed with chronic kidney disease. Europace 24, 1599–1607 (2022).

Deo, R. et al. Kidney dysfunction and sudden cardiac death among women with coronary heart disease. Hypertension 51, 1578–1582 (2008).

Pun, P. H. et al. Chronic kidney disease is associated with increased risk of sudden cardiac death among patients with coronary artery disease. Kidney Int. 76, 652–658 (2009).

Sobue, Y., Watanabe, E., Funato, Y., Yanase, M. & Izawa, H. Renal dysfunction is a time-varying risk predictor of sudden cardiac death in heart failure. ESC Heart Fail 11, 3085–3094 (2024).

Wang, A. Y. et al. Sudden cardiac death in end-stage renal disease patients: a 5-year prospective analysis. Hypertension 56, 210–216 (2010).

Schuett, K., Marx, N. & Lehrke, M. The cardio-kidney patient: epidemiology, clinical characteristics and therapy. Circ. Res. 132, 902–914 (2023).

Matsushita, K. et al. Epidemiology and risk of cardiovascular disease in populations with chronic kidney disease. Nat. Rev. Nephrol. 18, 696–707 (2022).

Sarnak, M. J. et al. Chronic kidney disease and coronary artery disease: JACC state-of-the-art review. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 74, 1823–1838 (2019).

House, A. A. et al. Heart failure in chronic kidney disease: conclusions from a Kidney Disease: improving Global Outcomes (KDIGO) controversies conference. Kidney Int. 95, 1304–1317 (2019).

Vanent, K. N. et al. Association of chronic kidney disease with risk of intracerebral hemorrhage. JAMA Neurol. 79, 911–918 (2022).

Ha, J. T. et al. Kidney function, albuminuria, and risk of incident atrial fibrillation: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Am. J. Kidney Dis. 83, 350–359.e351 (2024).

Stecker, E. C. & Nazer, B. The shadows of sudden cardiac death. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 77, 2363–2365 (2021).

Caravaca, F., Chávez, E., Alvarado, R., García-Pino, G. & Luna, E. Sudden cardiac death in non-dialysis chronic kidney disease patients. Nefrologia 36, 404–409 (2016).

van der Burgh, A. C. et al. Kidney function and the risk of sudden cardiac death in the general population. Clin. Kidney J. 15, 1524–1533 (2022).

Deo, R. et al. Cystatin C and sudden cardiac death risk in the elderly. Circ. Cardiovasc. Qual. Outcomes 3, 159–164 (2010).

Edmonston, D., Grabner, A. & Wolf, M. FGF23 and klotho at the intersection of kidney and cardiovascular disease. Nat. Rev. Cardiol. 21, 11–24 (2024).

Lu, X. & Hu, M. C. Klotho/FGF23 axis in chronic kidney disease and cardiovascular disease. Kidney Dis.3, 15–23 (2017).

Epstein, M. & Freundlich, M. The intersection of mineralocorticoid receptor activation and the FGF23-Klotho cascade: a duopoly that promotes renal and cardiovascular injury. Nephrol. Dial. Transpl. 37, 211–221 (2022).

Quarles, L. D. Endocrine functions of bone in mineral metabolism regulation. J. Clin. Investig. 118, 3820–3828 (2008).

Gattineni, J. & Baum, M. Regulation of phosphate transport by fibroblast growth factor 23 (FGF23): implications for disorders of phosphate metabolism. Pediatr. Nephrol. 25, 591–601 (2010).

Wang, W. et al. Association between NT-proBNP levels and risk of atrial fibrillation: a systematic review and meta-analysis of cohort studies. Heart 111, 109–116 (2025).

Lu, Y. et al. Trajectories of age-related arterial stiffness in Chinese men and women. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 75, 870–880 (2020).

Duan, J. W. et al. Association of long-term ambient fine particulate matter (PM(2.5)) and Incident CKD: A Prospective Cohort Study in China. Am. J. Kidney Dis. 80, 638–647.e631 (2022).

Hundemer, G. L. et al. Performance of the 2021 race-free CKD-EPI creatinine- and cystatin C-based estimated GFR equations among kidney transplant recipients. Am. J. Kidney Dis. 80, 462–472.e461 (2022).

Guo, Y. et al. Plasma proteomic profiles predict future dementia in healthy adults. Nat. Aging 4, 247–260 (2024).

Sun, B. B. et al. Plasma proteomic associations with genetics and health in the UK Biobank. Nature 622, 329–338 (2023).

Dhindsa, R. S. et al. Rare variant associations with plasma protein levels in the UK Biobank. Nature 622, 339–347 (2023).

Chen, J. et al. Peripheral inflammatory biomarkers are associated with cognitive function and dementia: Framingham Heart Study Offspring cohort. Aging Cell 22, e13955 (2023).

Warming, P. E. et al. Harmonization of the definition of sudden cardiac death in longitudinal cohorts of the European Sudden Cardiac Arrest network - towards Prevention, Education, and New Effective Treatments (ESCAPE-NET) consortium. Am. Heart J. 245, 117–125 (2022).

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by grants from Noncommunicable Chronic Diseases-National Science and Technology Major Project (2023ZD0503900, 2023ZD0503901, Y.L), National Natural Science Foundation of China (82170437, 82470445, Y.L), Provincial Natural Science Foundation of Hunan (2024JJ8118, Y.L), and Central South University Innovation-Driven Research Program (2023CXQD007, Y.L).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Y.L.L. and Y.L. conceived the project. L.Z. provided methodological support and revised the manuscript. Y.L.L. and Y.L. performed the data analysis and wrote the manuscript. R.J., C.O., J.W., and L.Z. visualized and organized the main results. Q.Y., J.L., W.H. and S.L. revised the manuscript. Y.C., J.C., H.Y. and L.Z. contributed to the discussion of the results. All the authors have reviewed, revised, and approved the manuscript.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Peer review

Peer review information

Nature Communications thanks Patrick Pun, Peter Rossing, and the other, anonymous, reviewer(s) for their contribution to the peer review of this work. A peer review file is available.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Source data

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Li, Y., Jiang, R., Ouyang, C. et al. Chronic kidney disease is associated with increased risk of sudden cardiac death. Nat Commun 16, 9180 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-025-64254-9

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-025-64254-9