Abstract

Zero-gap membrane electrode assembly (MEA) CO2 electrolysers offer high energy efficiency and promise for industrial application. However, the transport of carbonates within an anion exchange membrane (AEM) electrolyser leads to CO2 loss, thereby limiting carbon utilization efficiency. Emerging acidic anolyte electrolysers using cation exchange membrane (CEM) can address this challenge but face critical stability issues, including accelerated hydrogen evolution reaction (HER) and persistent salt precipitation. Here, we propose a porous membrane (PM) as an alternative to the CEM in acidic anolyte electrolysers. The system demonstrates continuous operation at 100 mA cm−2 for 200 h without salt precipitation, while maintaining nearly 100% CO selectivity. Furthermore, large-scale device (100 cm2) also shows stable performance. Mechanism analysis suggests that enhanced water permeation and bidirectional ion transfer are critical for achieving stable performance in acidic anolyte electrolysers. These findings offer a feasible approach for high-performance, stable and scalable acidic MEA CO2 electrolysers.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The electrochemical CO2 reduction reaction (CO2RR) holds great promise for mitigating CO2 emissions while producing value-added products1,2. Recent advancements have focused on the electrochemical conversion of CO2 into various products, including CH4, CO, C2H4, C2H5OH and HCOOH3,4,5,6. However, the low solubility of CO2 in aqueous systems imposes mass transfer limitations in H-cells, hindering the industrialization of CO2RR7,8. The introduction of gas diffusion electrodes (GDEs)9 has overcome these constraints, enabling efficient mass transfer and high current density operations in flow cells10 and membrane electrode assemblies (MEAs)11, imparting industrial feasibility of CO2RR. Among these devices, zero-gap MEA electrolysers have garnered significant attention due to their superior energy efficiency and operational stability12. This is particularly evident in alkaline and neutral electrolytes, where they achieve industrially relevant current densities with impressive performance and appreciable stability13. Despite these advantages, MEAs utilizing anion exchange membrane (AEM) face challenges such as carbonate crossover and salt precipitation14,15, leading to low carbon utilization efficiency and device degradation.

To address these challenges, cation exchange membrane (CEM) based MEA electrolyzers operating in acidic electrolytes have emerged as a promising alternative, reducing carbon loss associated with AEM-based systems16. However, CEM-based electrolyzers introduce additional complexities. In an external electric field, the high proton flux to the cathode in acidic electrolytes enhances hydrogen evolution reaction (HER), which competes with CO2RR. Although increasing the concentration of alkaline metal cations in the electrolyte can suppress HER and promote CO2RR, CEMs simultaneously transport both alkaline metal cations and protons to the cathode17. This results in salt precipitation due to reactions between alkaline metal cations and carbonate, the latter formed by the reaction of hydroxide (OH−)—a CO2RR byproduct—with supplied CO2 in the cathodic flow field. This precipitation compromises operational stability by clogging the cathodic flow field and GDE, further hindering system performance18.

Reducing the concentration of alkaline metal cations and modifying electrode configurations have been shown to alleviate these challenges19,20,21. However, ion transport in MEA electrolyzers remains constrained by the physical properties of CEMs and the externally applied electric field. The continuous transport of cations depletes metal ions in the anolyte and leading to instability in the cathodic microenvironment22. Additionally, CEMs prevent the crossover of cathodic liquid products into the anodic compartment, complicating the collection of liquid products in MEAs that operate without a catholyte23. To address these issues, innovative designs incorporating a thin electrolyte layer between the cathodic electrode and CEM have demonstrated improved stability in acidic electrolytes19,24. These configurations use a slim liquid layer that can be periodically refreshed during operation with minimal energy efficiency loss, enabling stable, long-term performance by optimizing CO2 and H2O management25. However, despite these improvements, such systems essentially function as flow cells. The use of a CEM results in the continuous depletion of metal ions in the anodic electrolyte, necessitating periodic electrolyte replacement and preventing sustained water-fed operation. Therefore, there remains a pressing demand for water-fed MEAs operating in acidic electrolytes to enhance energy efficiency and enable the practical industrial application of CO2RR.

From an economic perspective, the use of porous membranes (PMs) has gained attention as a cost-effective strategy for improving water management and stability in CO2RR systems. Lee et al. replaced AEMs with low-cost PMs to enhance economic feasibility while maintaining similar activity and selectivity26. Furthermore, they used polyvinylidene fluoride (PVDF) PMs to construct a large-scale CO2 electrolyzer stack (total area: 100 cm2)27, achieving over 80% CO selectivity during 110 h operation at 200 mA cm−2. However, periodic mitigation of salt precipitation was still necessary, and the CO2 crossover issue persisted under neutral condition. Ha et al. demonstrated the use of a PM in a MEA electrolyzer operating under acidic conditions, achieving a CO Faradic efficiency (FE) of 87.9% at 150 mA cm−2 while preventing salt formation28. However, despite PMs demonstrated higher efficiency and stability compared to ion exchange membrane (IEM)-based systems, periodic pulsing and washing were still required to suppress the salt deposition in the cathode flow field. Besides, the proportion of unreacted CO2 remained high and the efficiency of CO2 utilization was still low. We propose that utilizing PMs in acidic MEA electrolyzers can effectively manage the balance of ions, gas, and water by optimizing the electrolyte composition, selecting appropriate PMs, and adjusting the gas flow rate.

In this work, we employ a hydrophilic PM and utilize an Ag catalyst on a GDE to evaluate the CO2RR performance in comparison to conventional CEMs in acidic MEA electrolysers. The PM-based MEA electrolyser achieves a FE of 85% for CO at 400 mA cm−2 with a pH 2 anolyte, significantly outperforming the CEM-based MEA electrolyser, which only achieves 20% FE for CO. Furthermore, the single-pass CO2 conversion efficiency (SPCE) reaches 75%. In terms of long-term stability, a 4 cm2 MEA operated at 100 mA cm−2 for 200 h exhibits nearly 100% CO selectivity, while a 100 cm2 MEA sustains operation for over 120 h with more than 90% CO selectivity, without salt precipitation. Mechanistic analysis reveals that the superior water permeation and unrestricted ion transport capabilities of the PM play a pivotal role in maintaining stable performance under acidic conditions, effectively mitigating both HER and salt precipitation. These findings provide valuable insights into membrane design and strategies for enhancing the stability of industrial-relevant CO2RR systems.

Results

Mass transport in different membranes

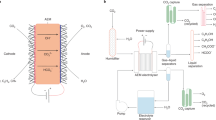

The examination of the operational principles of AEM, CEM and PM under an applied electric field (Fig. 1) reveals distinct mechanisms for each membrane type. In AEM-based systems, though the anion serves as the primary ion for maintaining charge balance through transport, alkaline metal ions in the anolyte inevitably migrate across the membrane due to the electric field and artifact of AEM. In alkaline and neutral anolyte systems, the carbonate and bicarbonate species formed at the cathode due to CO2RR may partially interact with the transported alkaline metal ions, leading to salt precipitation, while the remainder migrates to the anolyte, resulting in carbon loss. In CEM-based systems, the compositional structure of the CEM primarily facilitates cation transport while inhibiting anion migration, which leads to selective ion permeability, while unavoidable migration of alkaline metal ions may lead to a decrease in pH at the anode and significant accumulation of these ions at the cathode, promoting salt precipitation. Even if the issue of salt precipitation is mitigated, the excess of H+ at the cathode would heighten competition between the HER and the CO2RR. Furthermore, excessive H2O production from HER and CO2RR at the cathode could destabilize the GDE and degrade overall device performance29. In contrast, PM-based systems offer potential solutions to these challenges. The internal porous structure of the PM facilitates balanced, bidirectional transport of alkaline metal ions and H+, driven by both electric field and concentration polarization. Alkaline metal ions effectively activate CO2 molecules on the catalyst surface for CO2RR without significant salt accumulation. Protons, in turn, serve as charge carriers and facilitate the regeneration of CO2 at the cathode by reacting with carbonate and bicarbonate ions formed during CO2RR. Excess H2O generated at the cathode can be efficiently transported to the anode side, aided by the high hydrophobicity of the GDE and the superior H2O permeability of PM. This results in stable electrolysis operation with minimal competition from HER and a reduced risk of cathode flooding, positioning PM as a promising alternative for acidic electrolyte systems.

MEA performance comparison and analysis

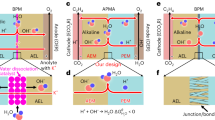

To evaluate the performance of PM in acidic systems, an Ag film was sputtered onto a GDE, and control variable experiments were conducted to compare CO2RR performance with CEM. Firstly, the performance differences in product selectivity were investigated using Cs2SO4 electrolyte with constant pH (adjusted with H2SO4) and varying Cs+ concentrations. Nafion membranes, a typical CEM, were used as a benchmark for comparison in this work with PM. The FE of CO remained at approximately 90% across all Cs+ concentrations when PM was used in acidic conditions (pH 2) and Cs+ concentrations ranged from 1 M to 0.01 M. (Fig. 2A), significantly outperforming the Nafion membrane, which exhibited lower CO FE under identical conditions. Then the impact of pH on CO FE with Cs+ concentrations maintained at 0.1 M and 0.01 M was investigated (Electrolyte: Cs2SO4 + H2SO4). For the PM, CO FE remained close to 90% at 0.1 M Cs+ even as the pH dropped to 0.5 (Fig. 2B), whereas the Nafion membrane showed a maximum CO FE of 60% at pH 3, with a noticeable decline in performance at lower pH values. At a Cs+ concentration of 0.01 M, the PM maintained stable CO FE until the pH decreased to 1, indicating the critical role of the alkaline metal ions to H+ ratio in influencing CO2RR performance (Supplementary Fig. 1A). In contrast, the Nafion membrane showed a maximum CO FE of only 50% under similar conditions, highlighting the superior ion mitigation properties of PM. In MEA systems, energy efficiency is a key parameter for evaluating the industrial feasibility of CO2RR processes. By comparing the cell voltage and CO FE at varying concentration of Cs+, energy efficiency was calculated, revealing that Cs+ concentration of 0.5 M and 1 M Cs+ represented nearly identical energy efficiency, both approaching 37% (Supplementary Fig. 1B). Lastly, 0.5 M Cs+ (pH 2) was selected for further comparative testing under varying current densities (Fig. 2C). Under these conditions, the PM consistently outperformed the Nafion membrane in terms of CO FE across all current densities. Considerably, the PM maintained 85% CO FE even at 400 mA cm−2, demonstrating its robustness and suitability for high performance CO2RR applications.

The FE of CO for MEA electrolyzer performance comparison between Nafion membrane and Porous membrane under 100 mA cm−2 using (A) different concentration of Cs2SO4 electrolyte (pH adjusted to 2 using H2SO4), B various pH value electrolyte (0.05 M Cs2SO4, pH adjusted by H2SO4), C CO FE comparison for Porous membrane and Nafion membrane under different current density using 0.25 M Cs2SO4 (pH adjusted to 2 using H2SO4). Values are means, and error bars indicate standard deviation (n = 3 replicates). D The FE of CO and H2 for MEA electrolyzer performance using Porous membrane at different CO2 gas flow rate and the corresponding SPCE under 100 mA cm−2 (Electrolyte: 0.25 M Cs2SO4, pH adjusted to 2 using H2SO4). Source data are provided as a Source Data file.

To validate the advantages of bidirectional ion transport for PMs, we also evaluated the performance of PM and AEM in both neutral (0.5 M KHCO3) and basic (0.5 M KOH) systems. The PMs showed considerable performance during stability tests conducted over a 10 h period (Supplementary Fig. 2), with no significant salt precipitation observed. Furthermore, the AEM displayed signs of instability (Supplementary Fig. 3A), with salt precipitation occurring after 3 h operation in basic conditions (0.5 M KOH) (Supplementary Fig. 3B), and after 5 h operation in neutral conditions (0.5 M KHCO3) (Supplementary Fig. 3C). The results demonstrated that the PMs could effectively slow down salt precipitation, thereby achieving considerable performance across all conditions tested. However, both neutral and basic systems exhibited a tendency for salt precipitation, driven by intrinsic ion transport dynamic, which hindered the efficiency of carbon utilization. These observations underscore the critical role of acidic electrolytes in enhancing CO2 utilization efficiency. To further investigate CO2 utilization, the gas flow rates were systematically varied. Based on previous work30, the theoretical 100% SPCE for CO production corresponds to a CO2 input gas rate of 2.8 standard cubic centimeters per minute (sccm) under a current density of 100 mA cm−2 for a 4 cm2 reaction area. The experimental results showed that decreasing the CO₂ input gas rate resulted in an increase in SPCE. Specifically, at a gas flow rate of 3 sccm, the SPCE reached 75% (Fig. 2D), thus confirming that acidic electrolytes facilitate more efficient CO2 utilization.

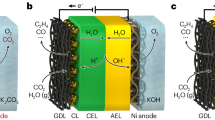

Measurement of ions diffusion rate

The observed differences in CO2RR performance between PM and Nafion membrane-based acidic MEA systems can be attributed to their distinct ion transport mechanisms, as outlined in Fig. 1. To assess the ion transport capability of both membranes under conditions of concentration polarization, ion diffusion experiments were conducted using an H-cell configuration (Fig. 3A). A 0.5 M Cs+ (pH 2) solution and pure water were separated by either the PM or Nafion membrane. The diffusion rate of Cs+ ions was monitored over time by measuring the Cs+ concentration on the pure water side using atom absorption spectroscopy, and H+ concentrations were monitored with a pH meter. The results demonstrated that PM exhibited significantly faster concentration polarization diffusion rates for both Cs+ ions (Fig. 3B) and H+ ions (Fig. 3C) compared to the Nafion membrane, suggesting that PM has a superior ability to facilitate ionic balance under concentration polarization. Under the applied electric field in MEA (Fig. 3D), ion transport by electromigration during CO2RR is theoretically dominated by four primary charge carriers: carbonate and bicarbonate (transported from cathode to anode), H+ and Cs+ (transported from anode to cathode). To further elucidate the ion transport under applied electric field, the variations in Cs+ and H+ concentrations in the anolyte were monitored during CO2RR. These changes were quantified using atomic adsorption spectroscopy for Cs+ and a pH meter for H+. The results showed rapid consumption of Cs+ (Fig. 3E) and a marked decrease of pH (Fig. 3F) when Nafion membrane was used, which corresponded to the instability and poor performance observed under high concentrations of H+. In contrast, the concentration of H+ and Cs+ remained stable when the PM was used, indicating there is no obvious Cs+ accumulation near the electrode, and the H+ produced by water oxidation would react as the charge carriers and the reactant, which leads to more stable ion transport dynamics. Typically, salt precipitated at the cathode during CO2RR is caused by the electromigration of alkaline metal ions from the anode side, leading to concentrations that exceed their saturation solubility. The enhanced concentration polarization ionic balance ability of the PM ensures that alkaline metal ions do not reach oversaturation, thus minimizing the likelihood salt precipitation.

A The schematic plot of the H cell setup: The two parts which contained 0.25 M Cs2SO4 solution (pH adjusted to 2 using H2SO4) and pure water were separated by either the porous membrane or Nafion membrane. The trends of Cs+ concentration (B) and pH value (C) over time during the diffusion test using Nafion membrane and Porous membrane, respectively. D The installation sketch of MEA electrolyzer for electrolysis. The trends of Cs+ concentration (E) and pH value (F) of the anolyte over time during electrolysis experiment under 100 mA cm−2 using 0.5 M Cs2SO4 (pH adjusted to 2 using H2SO4) for both Nafion membrane and Porous membrane, respectively. Values are means, and error bars indicate standard deviation (n = 3 replicates). Source data are provided as a Source Data file.

As highlighted in recent studies, there remains an active debate regarding whether protons (H+) or water (H2O) primarily act as the proton source under locally acidic conditions during CO2 electroreduction. Yao et al. demonstrated that the reaction proceeds only when the interfacial pH allows H2O to participate in the proton-coupled electron transfer (PCET) step31, rather than H+. In contrast, Wu et al. showed that proton-coupled CO2 activation dominates at low overpotentials, while at more negative potentials, the local pH increases and shifts the proton source to H2O32. Despite these mechanistic distinctions, both pathways ultimately lead to the same net chemical transformation. Based on the reactions at the anodic and cathodic chambers, we speculate that in the early stages of electrolysis, where an ample supply of H+ is available, the cathodic reduction likely proceeds via proton-coupled pathways, represented by (Eq. (1)) and (Eq. (2)):

Anode reaction:

Cathode reaction:

As electrolysis progresses and the local pH increases, the dominant proton source is expected to transition from H+ to H2O, as depicted in Eq. (3). Meanwhile, protons transferred from the anode react with OH- to form water (Eq. (4)), sustaining charge balance and contributing to local pH regulation:

Cathode reaction:

As for the CO production via CO2RR, water is not consumed. If there is H2 production at the cathode, the overall reaction aligns with water splitting reactions (Eq. (5)) and (Eq. (6)):

Anode reaction:

Cathode reaction:

In reaction where no metal cations are consumed to form carbonates, the reactions at the anode and cathode can achieve material balance. Specifically, in the context of CO production via CO2RR, neither water nor electrolytes are consumed; CO2 remains the sole reactant. Even in the presence of H2 generation at the cathode, water consumption remains minimal, with small amount of water required for replenishment during prolonged stability tests. However, IEM systems often encounter limitations due to restricted water transport. The accumulation of excess water at the cathode can disrupt the hydrophobicity of the GDE, leading to progressive degradation of the device33. Consequently, PM systems, with enhanced water transport capabilities, could maintain optimal humidity at the cathode, thereby supporting sustained performance of the MEA.

Device stability and large-scale application

To further assess the stability performance at lower Cs+ concentration and pH, tests were conducted using 0.05 M Cs2SO4 and 0.5 M H2SO4 anolyte for both membranes. The PM maintained a stable 90% CO FE over 60 min at 100 mA cm−2, whereas the Nafion membrane exhibited only approximately 20% CO FE (Fig. 4A). The suboptimal performance of the Nafion membrane was attributed to the highly acidic local environment at the catalyst/Nafion interface. In subsequent stability tests conducted with 0.5 M Cs2SO4 and 0.005 M H2SO4 (Fig. 4B), the PM exhibited a consistent cell voltage and sustained CO FE of 90% throughout the test, while the Nafion membrane displayed a sharp decline in CO FE, coupled with a significant increase in cell voltage. After 3 h of operation, salt precipitation was observed in the gas flow area, and the GDE became hydrophilic (Supplementary Fig. 4), consistent with the ion transport data. In principle, Nafion membrane, owing to their strong ionic selectivity under an electric field, inhibits cation transport from the cathode to the anode. This selective transport of cations in a single pass leads to cation accumulation, which, in combination with carbonate anions, promotes salt precipitation. In contrast, the PM does not hinder ion transport, preventing the accumulation of alkaline metal cations at the cathode and facilitating the combination of formed carbonates with H+ to regenerate CO2. Besides, the water management ability of PM was better than Nafion membrane and there was no obvious water accumulation throughout all comparative variable experiments.

A The operation stability of FE and voltage for Nafion membrane and Porous membrane under 100 mA cm−2 (Electrolyte: 0.05 M Cs2SO4 + 0.5 M H2SO4). B The operation stability of FE and voltage for Nafion membrane and Porous membrane under 100 mA cm−2 (Electrolyte: 0.5 M Cs2SO4 + 0.005 M H2SO4). C The FE of CO comparison among membranes made of different materials under 100 mA cm−2 using 0.25 M Cs2SO4 (pH adjusted to 2 using H2SO4). D The set-up diagram of 100 cm2 MEA electrolyzer. E The long-term operation stability of electrolyzers of different size under 100 mA cm−2 using 0.25 M Cs2SO4 (pH adjusted to 2 using H2SO4). All the voltages are full cell voltages without iR correction. Source data are provided as a Source Data file.

To explore the key parameters of the PM for maintaining high CO FE and operational stability. First, three types of PM with different pore sizes (0.1 μm, 0.22 μm and 0.45 μm) were evaluated (Supplementary Fig. 5) using 0.5 M Cs+ electrolyte (pH 2). The results showed negligible difference in CO FE during short-term test; however, membranes with larger pore sizes exhibited lower cell voltages. Then, several commercial PMs with the same pore size (0.22 μm) but different material compositions were investigated under identical electrolyte conditions (0.5 M Cs+, pH 2) (Fig. 4C). Among these, the PVDF membrane exhibited open-circuit states and no product performance under 10 V voltage overload conditions, while the polytetrafluoroethylene (PTFE) membrane demonstrated performance degradation over time. After plasma O2 treatment to improve its wettability, the PVDF membrane achieved about 80% CO FE. In contrast, the nylon membrane (used in this study) maintained a stable FE of CO. To further investigate the water permeation characteristics of these materials, a water contact angle test was conducted (Supplementary Fig. 6), where the contact angle was measured 11 s after water exposure. Among the tested PMs, nylon displayed appropriate water infiltration properties, which played a crucial role in maintaining effective water management and ensuring stable operation. Compared to nylon, the pristine PTFE membrane exhibits a high initial contact angle that rapidly decreases upon immersion, leading to water management issues such as flooding, consistent with the observed sharp decline in CO FE over time. Conversely, the highly hydrophobic PVDF membrane restricts ionic transport, reflected by its open-circuit behavior during CO2RR. Plasma treatment of PVDF effectively reduced its contact angle, enhancing wettability and enabling stable operation with about 80% CO FE. These results underscore that an optimal balance of hydrophilicity and hydrophobicity is essential for ensuring effective water management and sustained CO2 electrolysis performance.

To demonstrate the stability and scalability of PM-based acidic MEA, FE stability and cell voltage were assessed using both 4 cm2 and 100 cm2 cells (Fig. 4D and Supplementary Fig. 7) under a 0.5 M Cs+ (pH 2) electrolyte at 100 mA cm−2. The 4 cm2 cell demonstrated prolonged stability over 200 h, maintaining near 100% CO selectivity and a cell voltage keeping stable at 3.3 V (Fig. 4E). Post-operation inspection revealed a clean without any significant precipitation cathode gas flow field (Supplementary Fig. 8), indicating the PM’s efficacy in ion migration. Additionally, there was minimal change in the water contact angle of the used GDE. XRD analysis (Supplementary Fig. 9) confirmed the stability of Ag electrode. SEM (plane and cross-section) imaging before and after the long-term operation (Supplementary Fig. 10) showed no visible signs of salt precipitation or catalyst detachment. The catalyst layer remained morphologically intact, and no evidence of cracking or corrosion was observed. Overall, the cathode electrode surfaces remained clean and structurally stable. Due to the difficulty of precise pressure control between the cathodic gas and the anodic liquid compartments in large scale electrolyzers, minimal crossover of anodic liquid to the cathode was observed. The 100 cm² cell similarly sustained 90% CO selectivity for 120 h (Fig. 4E) while maintaining a stable cell voltage below 3.5 V. To verify the feasibility of the PM in practical large scale device, a three-cell CO2 electrolyser stack (total area: 300 cm2) (Supplementary Fig. 11) demonstrated 80% CO selectivity for 10 h under 100 mA cm−2. These results highlight the scalability and robustness of the PM, positioning it as a promising candidate for large-scale CO2RR application.

Based on experimental performance comparisons and mechanistic analysis, the advantages and disadvantages of PM and CEM were discussed (Supplementary Table 1). The PM demonstrated superior water management and ion transport capabilities, making it a promising candidate for industrial applications. The key advantages of the PM include its low cost, unrestricted ion conductivity, chemical stability, effective water management, and scalable physical properties. However, the inherent physical properties of the PM may give rise to potential gas or liquid crossover issues, which could be mitigated through optimization of the gas/liquid supply system or the development of membranes with tailored pore sizes. This study offers an alternative approach to the design of critical components in MEA, challenging the traditional reliance on IEM, with the goal of achieving stable operation and efficient mass management throughout the electrochemical process.

Discussion

In this work, we successfully utilized a PM to operate an acidic MEA electrolyzer under high current densities, achieving stable performance with high CO FE over extended operation times. The PM enables effective CO2RR even in the presence of high H+ concentrations by leveraging bidirectional ion transfer without significant ion consumption, thereby ensuring long-term operational stability. Key factors contributing to this stability include efficient water management and enhanced mass transfer, which are critical for achieving robust performance in MEA. Our findings provide valuable insights into the unique operating mechanisms of PM and highlight their potential to overcome existing challenges in acidic CO2RR systems. These results serve as a foundation for the design and development of advanced electrolyzer devices for industrial-scale CO2 reduction.

Methods

Chemicals and materials

All chemicals used in this study were of high purity and utilized without further purification. Cesium sulfate (Cs2SO4, 99.9%), potassium bicarbonate (KHCO3, 99.9%) and potassium hydroxide (KOH, 99.9%) were purchased from Aladdin. Sulfuric acid (H2SO4, 98%) was purchased from Tianjin Binhai New Area Guangshunda Chemical Reagent Co., Ltd. All of the porous membrane specification were listed in Supplementary Table 2. Hydrophilic Nylon (pore size: 0.22 μm, thickness: 110 μm) was obtained from Ameritech brand. Hydrophilic PTFE membrane (pore size: 0.22 μm, thickness: 110 μm) and hydrophilic PVDF membrane (pore size: 0.22 μm, thickness: 110 μm) were obtained from Nantong Longjin membrane technology Co., Ltd. Nafion 117 membrane (183 μm) and Fumatech (FAA-3-50, 50 μm) anion exchange membrane were purchased from Suzhou Shengernuo company. Silver targets (99.999%) for magnetron sputtering were purchased from Beijing Zhongsheng Company. IrO2/Ti electrodes were purchased from Kunshan material company, and carbon paper (Sigrate-22BB) was supplied by Saibo electrochemical company. Carbon dioxide (CO2, 99.9%) was purchased from Tianjin BAISIDA Gas Limited Company. Ultrapure water (18.25 MΩ•cm) was used in all experiments to ensure consistency and eliminate potential contamination.

Characterizations

X-ray diffraction (XRD) patterns were collected at room temperature using a PANalytical diffractometer (Netherlands) operated at 40 kV and 15 mA (600 W). Scanning electron microscopy (SEM) was performed on a field-emission microscope (JSM-7800F, JEOL, Japan). The pH value of the electrolyte was performed on the METTLER TOLEDO FE28-Standard pH meter. Atomic adsorption spectroscopy was carried out on the contrAA 700 Continuous light source atomic absorption spectrometer with high ultraviolet sensitivity CCD linear array detector. The contact angle measurements were performed using a contact angle goniometer (JC2000C1, POWEREACH, Shanghai Zhongchen Digital Technology Equipment Co., Ltd., China). The instrument was operated at an AC220 V rated voltage and a frequency of 50 Hz. All measurements were conducted at room temperature using deionized water as the probe liquid. The contact angle was determined by the sessile drop method, and each reported value represents the average of at least three independent measurements.

Electrode and membrane preparation

Ag GDE was prepared by magnetron sputtering (Pudi Inc.) of 99.999% pure Ag targets (Loyaltarget) onto a carbon paper substrate. The sputtering process was carried out under a 0.5 Pa argon atmosphere with an argon flow rate of 80 sccm. A sputtering power of 40 W was applied for 20 min. The resulting silver-coated (~300 nm thick) GDE was then carefully transferred. The fresh Nafion membrane was pretreated by boiling in 3 wt% H2O2 for 30 min to remove organic impurities, followed by soaking in ultrapure water for 30 min. To achieve proton exchange, the membrane was then boiled in 0.5 mol/L H2SO4 for 30 min and rinsed in ultrapure water before use. The FAA-3-50 was pretreated by 1 M KOH for 24 h before use. The porous membranes were used directly without additional treatment. The plasma treat process was carried out on RIE plasma etcher Etchlab 200.

Cell assembly and electrochemical CO2 reduction measurements

Membrane electrode assembly (MEA)

The 4 cm2 (active area) MEA electrolyzer was constructed with two titanium flow field plates. The setup featured a dual-electrode configuration, with Ag GDE samples (2 × 2 cm2) serving as cathode catalysts and a commercial DSA electrode (titanium mesh coated with iridium oxide, 2 × 2 cm2) as the anode material. The cathode electrode and the anode electrode were separated by membrane (Nafion membrane or porous membrane or FAA-3-50, 2.5 × 2.5 cm2). The cathodic flow field was supplied with 20 sccm of CO2 gas via a mass flow controller (MFC, INHA), and gas product flow rates were measured using a soap film flowmeter for faradic efficiency calculations. The anodic flow filed was fed with fresh acidic Cs2SO4 electrolytes (50 mL, pH adjusted to different values using H2SO4) continuously at a 5 mL/min using a peristaltic pump (Kamoer). In details, different concentration of acidic Cs2SO4 electrolytes were prepared fresh before the experiment, and the pH was adjusted through a pH Meter (METTLER TOLEDO FE28-Standard pH meter, accuracy 0.01). For the basic and neutral electrolyte test, the anodic flow filed was fed with fresh KOH electrolytes (100 mL, 0.5 M) or KHCO3 electrolytes (100 mL, 0.5 M) continuously at a 5 mL/min using a peristaltic pump.

The construction of 100 cm2 MEA electrolyzer was similar as the 4 cm2 device. The 300 cm2 stack comprised three 100 cm2 bipolar plates and two end plates. The setup featured a dual-electrode configuration, with a Ag GDE serving as cathode and a DSA as the anode, separated by a porous membrane. CO2 was supplied to the cathodic flow field at 300 and 500 sccm via a MFC (INHA) for 100 cm2 and 300 cm2 electrolyser, respectively. The anodic flow field was fed with 0.25 M Cs2SO4 electrolytes (500 mL, pH adjusted to 2 using H2SO4) continuously at a 20 mL/min using a peristaltic pump.

All tests were conducted using a DC power supply and an electrochemical workstation (Jiangsu Donghua Analytical Instrument Co.). The FE of products was measured at a fixed current density, and the voltage was recorded. All voltage values were full cell voltage without iR correction.

CO2RR products analysis

When operating the MEA, the outlet gas was directed through a safety bottle to a gas chromatograph (GC, Fuli Inc. 9790 Plus) for gas product analysis and the gas product flow rates were measured using a soap film flowmeter for faradic efficiency calculations. The gas sample was conducted at 9-minute intervals. H2 was detected using a thermal conductivity detector (TCD), while other gaseous products such as carbon monoxide (CO), methane (CH4), ethylene (C2H4), and ethane (C2H6) were analyzed with two flame ionization detectors (FIDs). All gas product concentrations were calibrated using standard gas mixtures. In this work, the faradic efficiency for liquid product was low and negligible. Values are means, and error bars indicate standard deviation (n = 3 replicates).

The Faradaic Efficiency (FE) of gas products was calculated using the formula:

Where F was the Faraday constant (96500 C mol−1), v was the cathodic outlet gas flow rate (calibrated by a soap film flowmeter), y was the product concentration derived from a standard calibration curve for the 1 mL sample loop, N was the number of electrons transferred per reaction, and i was the working current.

The energy efficiency (EE) was calculated as follow,

The calculation of cathodic energy efficiency was performed for the half-cell under the assumption of zero overpotential for the oxygen evolution reaction.

The single-pass conversion efficiency evaluates carbon utilization as the ratio of the transformed desired products to the supplied CO2.

Where i was the total current, N was the electron transfer per product molecule. vin was the inlet CO2 flow rate without applied voltage.

Data availability

Data supporting the findings of this study are available within the article and its Supplementary Information. The raw data is provided within the Source data file. Source data are provided with this paper.

References

Zhu, P. et al. Continuous carbon capture in an electrochemical solid-electrolyte reactor. Nature 618, 959–966 (2023).

Wang, M. & Luo, J. A coupled electrochemical system for CO2 capture, conversion and product purification. eScience 3, 100155 (2023).

Farooqi, S. A., Farooqi, A. S., Sajjad, S., Yan, C. & Victor, A. B. Electrochemical reduction of carbon dioxide into valuable chemicals: a review. Environ. Chem. Lett. 21, 1515–1553 (2023).

Lee, T., Lee, Y., Eo, J. & Nam, D.-H. Acidic CO2 electroreduction for high CO2 utilization: catalysts, electrodes, and electrolyzers. Nanoscale 16, 2235–2249 (2024).

Chen, F. et al. Recent advances in p-block metal chalcogenide electrocatalysts for high-efficiency CO2 reduction. eScience 4, 100172 (2024).

Fu, Y., Wei, S., Du, D. & Luo, J. Cyclic voltammetry activation of magnetron sputtered copper–zinc bilayer catalysts for electrochemical CO2 reduction. EES Catal. 2, 603–611 (2024).

Dunwell, M., Yan, Y. & Xu, B. Understanding the influence of the electrochemical double-layer on heterogeneous electrochemical reactions. Curr. Opin. Chem. Eng. 20, 151–158 (2018).

Han, N., Ding, P., He, L., Li, Y. & Li, Y. Promises of main group metal–based nanostructured materials for electrochemical CO2 reduction to formate. Adv. Energy Mater. 10, 1902338 (2020).

Higgins, D., Hahn, C., Xiang, C., Jaramillo, T. F. & Weber, A. Z. Gas-diffusion electrodes for carbon dioxide reduction: a new paradigm. ACS Energy Lett. 4, 317–324 (2019).

Wang, Q. et al. Lanthanide single-atom catalysts for efficient CO2-to-CO electroreduction. Nat. Commun. 16, 2985 (2025).

Iglesias van Montfort, H.-P. et al. An advanced guide to assembly and operation of CO2 electrolyzers. ACS Energy Lett. 8, 4156–4161 (2023).

Zhang, Z. et al. Membrane electrode assembly for electrocatalytic CO2 reduction: principle and application. Angew. Chem. Int Ed. 62, e202302789 (2023).

Wei, P. et al. CO2 electrolysis at industrial current densities using anion exchange membrane based electrolyzers. Sci. China Chem. 63, 1711–1715 (2020).

Garg, S. et al. How alkali cations affect salt precipitation and CO2 electrolysis performance in membrane electrode assembly electrolyzers. Energy Environ. Sci. 16, 1631–1643 (2023).

Moss, A. B. et al. In operando investigations of oscillatory water and carbonate effects in MEA-based CO2 electrolysis devices. Joule 7, 350–365 (2023).

Zou, X. & Gu, J. Strategies for efficient CO2 electroreduction in acidic conditions. Chin. J. Catal. 52, 14–31 (2023).

Chae, K. J. et al. Mass transport through a proton exchange membrane (nafion) in microbial fuel cells. Energy Fuels 22, 169–176 (2008).

Zhang, Z. et al. Unravelling the carbonate issue through the regulation of mass transport and charge transfer in mild acid. Chem. Sci. 15, 2786–2791 (2024).

Fan, M. et al. Cationic-group-functionalized electrocatalysts enable stable acidic CO2 electrolysis. Nat. Catal. 6, 763–772 (2023).

Lhostis, F. et al. Promoting selective CO2 electroreduction to formic acid in acidic medium with low potassium concentrations under high CO2 pressure. ChemElectroChem 11, e202300799 (2024).

Zeng, M. et al. Reaction environment regulation for electrocatalytic CO2 reduction in acids. Angew. Chem. Int Ed. 63, e202404574 (2024).

Habibzadeh, F. et al. Ion exchange membranes in electrochemical CO2 reduction processes. Electrochem Energy R. 6, 26 (2023).

Xie, Y. et al. High carbon utilization in CO2 reduction to multi-carbon products in acidic media. Nat. Catal. 5, 564–570 (2022).

Li, L., Liu, Z., Yu, X. & Zhong, M. Achieving high single-pass carbon conversion efficiencies in durable CO2 electroreduction in strong acids via electrode structure engineering. Angew. Chem. Int Ed. 62, e202300226 (2023).

Weng, L.-C., Bell, A. T. & Weber, A. Z. Towards membrane-electrode assembly systems for CO2 reduction: a modeling study. Energy Environ. Sci. 12, 1950–1968 (2019).

Lee, W. H. et al. New strategies for economically feasible CO2 electroreduction using a porous membrane in zero-gap configuration. J. Mater. Chem. A 9, 16169–16177 (2021).

Ha, M. G. et al. Efficient and durable porous membrane-based CO2 electrolysis for commercial Zero-Gap electrolyzer stack systems. Chem. Eng. J. 496, 154060 (2024).

Ha, T. H., Kim, J., Choi, H. & Oh, J. Selective zero-gap CO2 reduction in acid. ACS Energy Lett. 9, 4835–4842 (2024).

Lees, E. W., Bui, J. C., Romiluyi, O., Bell, A. T. & Weber, A. Z. Exploring CO2 reduction and crossover in membrane electrode assemblies. Nat. Chem. Eng. 1, 340–353 (2024).

Wei, S., Hua, H., Ren, Q. & Luo, J. Enhanced electrochemical carbon dioxide reduction in membrane electrode assemblies with acidic electrolytes through a silicate buffer layer. Chin. J. Catal. 66, 139–145 (2024).

Yao, Y., Delmo, E. P. & Shao, M. The electrode/electrolyte interface study during the electrochemical CO2 reduction in acidic electrolytes. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 64, e202415894 (2025).

Wu, W. & Wang, Y. The role of protons in CO2 reduction on gold under acidic conditions. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 147, 11662–11666 (2025).

Byun, S.-J. & Kwak, D.-K. Removal of flooding in a PEM fuel cell at cathode by flexural wave. J. Electrochem. Sci. Te 10, 104–114 (2019).

Acknowledgements

J. L. acknowledges the funding from the National Key R&D Program of China (2019YFE0123400), the Tianjin Distinguished Young Scholar Fund (20JCJQJC00260), the Major Science and Technology Project of Anhui Province (202203f07020007), and the Anhui Conch Group Co., Ltd.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

J. L. supervised the project. S. W. conceived the idea. S. W. designed and performed the experiments. Y. Z. helped with the atomic adsorption spectroscopy test. J. L., S. W., and H. H. contributed to the data interpretation and writing of the manuscript. All authors commented on the manuscript and made thorough revisions and final review of the paper.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

J. L. and S. W. have filed a patent application regarding the application of the porous membranes in MEA CO2 electrolyzers. The other authors declare no competing interests.

Peer review

Peer review information

Nature Communications thanks the anonymous reviewers for their contribution to the peer review of this work. A peer review file is available.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Source data

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Wei, S., Hua, H., Zhao, Y. et al. Porous membranes enable selective and stable zero-gap acidic CO2 electrolysers. Nat Commun 16, 9299 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-025-64342-w

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-025-64342-w