Abstract

Polymer-based solid-state batteries operable across broad temperatures are critical for advanced energy storage but face limitations from sluggish ion transport kinetics in polymer electrolytes. Here, we develop a fluorinated quasi-solid polymer electrolyte that balances weak Li⁺-polymer interactions with efficient salt dissociation. This electrolyte was fabricated by in situ polymerization of 2,2,3,4,4,4-hexafluorobutyl acrylate. The incorporation of -CF2- groups within 2,2,3,4,4,4-hexafluorobutyl acrylate promotes the formation a fluorine-oxygen co-coordination structure that decouples ion conduction from polymer relaxation. This mechanism creates more efficient Li⁺ transport pathways along polymer chains and surrounding solvent molecules, promoting uniform Li⁺ flux at the Li metal electrode interface. Consequently, the electrolyte exhibits 0.27 mS cm−1 conductivity at −40 °C, enabling 10 C rates and operation from −50 to 70 °C in Li | |LiNi0.8Co0.1Mn0.1O2 cells. At 20 mA g−1 and −30 °C, the 4.5 V coin cell retains 64.3% capacity of its 30 °C capacity, while cells maintain 86% capacity after 200 cycles at 60 mA g−1 and 30 °C. Extending this coordination-tuning strategy to sodium-based systems yields similar ion-transport enhancements, highlighting its broad applicability for next-generation solid-state batteries.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Current electrolytes, predominantly based on carbonate esters, encounter significant challenges in meeting the rigorous demands of lithium batteries. These challenges include their constrained voltage window, typically limited to 4.3 V, as well as their narrow operational temperature range, typically spanning from −20 °C to +50 °C1,2,3. Additionally, these electrolytes exhibit high flammability, posing considerable safety concerns4,5,6. The adoption of polymer electrolytes in the development of Li metal batteries presents a promising solution to both energy density and safety issues7,8,9, because they are inherently flexible, promote intimate electrode contacts, offer facile processing, and are cost-effective. These attributes position polymer electrolytes as highly attractive materials for constructing solid-state batteries10,11,12.

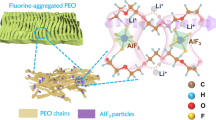

Despite their promise, polymer electrolytes, such as those based on polyethylene oxide (PEO), encounter significant challenges in achieving stable operation across a wide temperature range, particularly from low temperatures (<−20 °C) to high temperatures (>+60 °C)13,14,15. The inherent limitations of polymer electrolytes stem from their sluggish Li+ transport kinetics and inadequate electrochemical/thermal stability. Considerable efforts have been dedicated to the development of highly ion-conducting polymer electrolytes aimed at enhancing Li+ transport efficiency to achieve uniform Li deposition16,17,18. One approach involves the incorporation of plasticizers into polymer matrices, which has shown promise in improving the ion transport. In such systems, the ionic conduction primarily occurs through diffusion in solvated forms akin to carbonate-based liquid electrolytes19,20. However, improving the ionic conductivity of quasi-solid electrolytes requires more than just the addition of solvents; it demands a thorough understanding of complex molecular interactions and dynamic behaviors. As depicted in Fig. 1a, the presence of strong ion-dipole interactions (Li+…O = C) in polymer electrolytes results in sluggish Li+ decomplexation and migration, particularly at low temperatures. Moreover, the organic solvents involved in the Li+ coordination can lead to parasitic reactions with both electrodes, especially in polymer electrolytes operating at elevated temperatures21,22,23. Consequently, dendritic Li plating and continuous loss of lithium inventory are more likely to occur under both low and high temperature conditions.

In this study, we engineer a fluorinated quasi-solid polymer electrolyte specifically tailored for broad-temperature solid-state batteries by modulating the local Li+ conformation. Leveraging the strong electro-withdrawing characteristics of fluorinated substitution groups within the polymer, we achieve the formation of a fluorine-oxygen co-coordination structure. This unique conformational feature effectively decouples ionic conduction from polymer relaxation, facilitating the establishment of high-speed Li+ transport pathways and ensuring homogeneous Li+ flux at the Li metal negative electrode interface, as depicted in Fig. 1b. As a result of these advancements, the fluorinated quasi-solid polymer electrolyte exhibits a high ionic conductivity of 0.27 mS cm−1 at −40 °C. This electrolyte design enables high-rate capability (10 C) and stable operation across a broad temperature range (−50 to 70 °C) in quasi-solid-state lithium batteries. Notably, 4.5 V Li | |LiNi0.8Co0.1Mn0.1O2 (NCM811) coin cells retain 64.3% of their 30 °C capacity at 20 mA g−1 and −30 °C, while Li | |NCM811 cells maintain a capacity retention of 86% after 200 cycles at 60 mA g−1 and 30 °C. Furthermore, applying similar design principles, solid-state sodium metal batteries with Na-based fluorinated quasi-solid polymer electrolyte demonstrate high-rate capability (20 C) and stable cycling performance across a broad temperature range from (−40 °C to 70 °C) as well.

Results

Designing fluorinated polymer electrolytes

Polymers that exhibit reduced ion-dipole interactions are indicative of rapid coupling/decoupling processes, but demonstrate low Li+ decomplexation energies while minimally compromising ionic dissociation ability, which is a key criterion in polymer selection. The dielectric constant (ε) and donor number (DN) are recognized as primary descriptors for evaluating the capability to overcome the lattice energy of salt and facilitate the formation of complex ions24. In Fig. 2a and Supplementary Data 1, the ε and DN of various polymers and plasticizers are presented. In comparison to butyl acrylate (BA), 2,2,3,4,4,4-hexafluorobutyl acrylate (HFA) demonstrates a low ε and DN, suggesting weak interactions between Li+ ions and polymer dipoles.

a Dielectric constants and donor numbers of different polymer monomers and solvents; b Electrostatic potential of different polymer monomers. left: BA; right: HFA, and optimized binding geometry of Li+-BA and Li+-HFA. c Bond lengths of Li+-solvent complexes. d Binding energies of Li+-solvent molecules. e Comparison of the melting points and boiling points of various solvents. f Ionic conductivities of electrolytes at different temperatures. g Ionic transference numbers tLi+ of different electrolytes. h LSV curves of electrolytes upon the anodic scan. “Liquid” denotes the liquid electrolyte, “polymer” denotes the non-fluorinated quasi-solid polymer electrolyte, and “fluorinated polymer” denotes the fluorinated quasi-solid polymer electrolyte.

The electrostatic potentials were further explored to elucidate the electron density distribution of different monomers and plasticizers (Fig. 2b, Supplementary Fig. 1, and Supplementary Data 1). Compared to BA, the electron cloud density of the carbonyl oxygen is notably weaker in the case of HFA, indicating the formation of multiple binding sites with Li+ ions, forming a fluorine-oxygen co-coordination structure (Fig. 2b). Figure 2c, d and Supplementary Fig. 1 illustrate the Li bond length and binding energy of Li+ ions with solvents and polymers. Longer lithium bonds with carbonyl oxygen (1.79 Å) in HFA are observed, while the binding energy between Li+ ions and HFA (−190.8 kJ/mol) is significantly smaller as compared to that of Li+ ions and BA (−217.3 kJ/mol). The weaker binding between Li+ ions and HFA is expected to enhance the Li+ decomplexation process and transport kinetics. As a result, HFA was chosen as the polymer monomer for this study.

Compared to methyl propionate (MP), methyl 3,3,3-trifluoropropanoate (MTFP) possesses a low DN and a moderate ε, optimizing the balance between solvent coordination strength and effective salt dissociation. Maintaining high ionic conductivity across a broad temperature range is crucial, which necessitates a low freezing point and moderate boiling point (Fig. 2e). Consequently, MTFP was selected as the solvent. The addition of fluoroethylene carbonate (FEC) can significantly improve the stability of the electrolyte to lithium metal and enhance its oxidation resistance25. Lithium bis(fluorosulfonyl)imide (LiFSI) is a suitable choice due to its high dissociation, solubility, as well as its electrochemical stability (Supplementary Fig. 2, Supplementary Data 1, and Supplementary Note 1 for details)26.

Consequently, fluorinated quasi-solid polymer electrolyte incorporating HFA-MTFP-FEC-LiFSI was synthesized using the in situ polymerization method at 60 °C for 2 hours (Supplementary Fig. 3). Investigations using Fourier transform infrared spectroscopy (FTIR) and gel permeation chromatography (Supplementary Figs. 4 and 5) reveal the solidification process, where the initially flowable liquid precursor transitions into a solid-like electrolyte with free-standing characteristics (Supplementary Figs. 6–8, with relevant analyses in Supplementary Note 2). Notably, the polymer matrix in the fluorinated quasi-solid polymer electrolyte effectively immobilizes the solvents and mitigates the risk of liquid leakage, even though the liquid phase accounts for 54.8%, as depicted by the leakage experiments and the thermogravimetric analysis (Supplementary Figs. 9 and 10, and Supplementary Note 3 for details). These findings demonstrate that the fluorinated polymer electrolyte is capable of forming a stable, free-standing membrane and exhibits reliable solvent-sealing properties, making it well-suited for safe and effective battery technology.

For comparison, the following electrolytes were also used in subsequent experiments: a liquid electrolyte (1 M lithium hexafluorophosphate (LiPF6) in an ethylene carbonate (EC): dimethyl carbonate (DMC) 1:1 v/v carbonate solution), a non-fluorinated quasi-solid polymer electrolyte prepared by replacing HFA and MTFP with BA and MP, respectively, and a quasi-solid (poly-BA)/MTFP electrolyte prepared by replacing HFA with BA.

Physicochemical properties of electrolyte

The ionic conductivity of the fluorinated quasi-solid polymer electrolyte was assessed using electrochemical impedance spectroscopy (EIS) measurements. As depicted in Fig. 2f and Supplementary Figs. 11 and 12, the fluorinated polymer electrolyte exhibits an ionic conductivity of 2.95 mS cm−1 at 30 °C and 0.27 mS cm−1 at −40 °C, surpassing that of the non-fluorinated polymer electrolyte (2.6 mS cm−1 at 30 °C and 0.2 mS cm−1 at −40 °C), suggesting that the ionic conductivity depends critically on both solvent molecules and polymer coordinating units. While the conductivity of the liquid electrolyte is larger at temperatures above 0 °C, it decreases dramatically when temperatures drop below −20 °C. The temperature-dependent conductivities of the fluorinated quasi-solid polymer electrolyte align well with the Arrhenius equation (Supplementary Fig. 13)27. Li+ migration within the fluorinated quasi-solid polymer electrolyte is expedited, with an activation energy (Ea) for the ionic conduction of only 17.4 kJ mol−1, whereas the non-fluorinated polymer electrolyte exhibits a higher Ea of 20.3 kJ mol−1. Furthermore, the fluorinated quasi-solid polymer electrolyte demonstrates an elevated Li+ transference number of 0.56, surpassing those of the non-fluorinated polymer electrolyte (0.31) and the liquid electrolyte (0.26) (Fig. 2g and Supplementary Fig. 14). This increase in Li+ transference number can be attributed to the robust interactions between anions and -CHF groups in the fluorinated polymers28.

The electrochemical stability window of the electrolytes was evaluated using linear sweep voltammetry (LSV) and electrochemical floating tests. As shown in Fig. 2h and Supplementary Figs. 15 and 16, the fluorinated quasi-solid polymer electrolyte exhibits an electrochemical window exceeding 5.0 V. This enhanced electrochemical stability primarily stems from the fluorination of the polymer monomers and plasticizers. In contrast, the non-fluorinated polymer electrolyte and the liquid electrolyte exhibit oxidation starting around 4.2 and 4.7 V vs Li/Li+, respectively. Supplementary Fig. 17, illustrating cyclic voltammetry (CV) curves, demonstrates the reversible plating and stripping of Li on the negative electrode between −0.2 and 2.5 V, indicating no side-reaction between the fluorinated quasi-solid polymer electrolyte and Li metal negative electrodes. Additionally, the fluorinated quasi-solid polymer electrolyte exhibits high safety characteristics (as demonstrated in combustion tests presented in Supplementary Fig. 18, Movie 1, and Supplementary Note 4), as the fluorination significantly reduces the generation of hydrogen radical29.

Li+ coordination structure and ionic conduction

Polymer electrolytes are complexes formed through reactions of Li salts with polar or Lewis-acid-base active groups (e.g., -C = O, -C-O-, -C-F) within polymer hosts (or other additives). Molecular dynamics (MD) simulations were conducted to envisage the polymer-salt complexes and elucidate the ionic conduction mechanisms. In the non-fluorinated quasi-solid polymer electrolyte, Li+ ions are predominantly coordinated by 1.17 poly-BA, 1.73 MP plasticizers, and 1.51 FSI− anions at energy equilibrium, resulting in the formation of a “helical” Li+ conformation (Fig. 3a, c and Supplementary Data 1)30,31. However, in the fluorinated quasi-solid polymer electrolyte, the coordination numbers of Li+ with poly-HFA and MTFP plasticizers decrease to 0.94 and 1.69, respectively, while the coordination number of Li+ with FSI− anions increases to 1.36 (Fig. 3b, d and Supplementary Data 1), the liquid solvent within the primary Li⁺ solvation shell facilitates the Li+ migration. Due to the weak binding energy with Li+ ions, FEC molecules predominantly exist in a free state in electrolytes32.

Molecular dynamic simulation snapshots of (a) non-fluorinated quasi-solid polymer electrolyte, and (b) fluorinated quasi-solid polymer electrolyte. Radical distribution functions and the corresponding average coordination numbers for the poly-BA (c) and poly-HFA (d) quasi-solid polymer electrolytes. e MSD of Li+ in poly-BA and poly-HFA quasi-solid polymer electrolytes. f Oxygen K-edge XANES spectra of fluorinated quasi-solid polymer electrolyte and non-fluorinated quasi-solid polymer electrolyte. The normalization method is to subtract the background signal, set the pre-edge to 0, and set the post-edge at the end to 1. g 7Li ssNMR spectra of non-fluorinated quasi-solid polymer electrolyte and fluorinated quasi-solid polymer electrolyte. h 19F ssNMR spectra of fluorinated quasi-solid polymer electrolyte with or without LiFSI.

The radial distribution function of Li+…O = C (poly-BA) shows closer interactions with Li+ (~1.92 Å) compared to poly-HFA (1.94 Å) (Fig. 3c, d). Additionally, the overall concentration of O(poly-HFA) around Li+ is notably lower than that of O(poly-BA), with clear Li-F interactions observed at distances of approximately 2.04 Å (0.51 for poly-HFA, Supplementary Fig. 19). This suggests the formation of a fluorine-oxygen co-coordination structure in the fluorinated polymer electrolyte. Additionally, mean square displacement (MSD) predictions from the MD calculations indicate accelerated ion transport kinetics in the fluorinated quasi-solid polymer electrolyte, with a higher Li+ diffusivity of 4.8 × 10−9 cm2 s−1, as compared to that of 2.1 × 10−9 cm2 s−1 for the non-fluorinated polymer electrolyte (Fig. 3e and Supplementary Data 1). The fluorinated quasi-solid polymer electrolyte exhibits weaker ion-dipole interactions and a looser Li-polymer coordination structure, indicating balance between moderate Li+-solvating power and efficient ionic transport.

The molecular structure was further investigated using a range of analytical techniques, including FTIR, Raman spectroscopy, solid-state nuclear magnetic resonance (ssNMR) spectroscopy, and K-edge X-ray absorption near edge structure (XANES) spectroscopy. The coordination environment of the fluorinated quasi-solid polymer electrolyte was characterized using oxygen K-edge XANES spectroscopy. As shown in Fig. 3f, the edge position shifts to lower energy with the fluorinated electrolyte, indicating that the addition of the F group reduces electron transfer between Li+ and O in poly-HFA, weakening the bonding strength between Li+ and C = O(poly-HFA) in the Li+ solvation sheath. The O K-edge peak near 536 eV shifts to a lower wave number, further confirming the presence of weak ion-dipole interactions within the fluorinated quasi-solid polymer electrolyte33,34. Additionally, investigations using FTIR and Raman spectroscopy (Supplementary Figs. 20 and 21, with relevant analyses in Supplementary Note 5) confirm the interaction of Li+ with F and C = O in the fluorinated polymer electrolyte, these results align well with the outcomes of the MD calculations, indicating a diminished Li+-poly-HFA coordinating ability.

SsNMR spectroscopy provides additional insights into molecular structural characteristics. The 7Li ssNMR spectra in Fig. 3g reveal a downfield-shifted signal in the fluorinated quasi-solid polymer electrolyte due to reduced electron density around the Li atoms, supporting the notion that Li+ ions are less tightly bound by the poly-HFA backbone35,36,37. Furthermore, a downward trend of F peaks is observed in the 19F ssNMR spectra (Fig. 3h) following the addition of the LiFSI salt, suggesting strong -C-F…Li+ resonances and diminished affinity between C = O and Li+ ions38,39,40. This suggests the formation of a distinct fluorine-oxygen co-coordination structure, where Li+ ions are coordinated with reduced intensity alongside polymer dipoles, thus providing supplementary Li+ transport sites.

The above theoretical calculations and experimental investigations reveal a distinctive molecular architecture with the following key features: (1) The formation of a fluorine-oxygen co-coordination structure reduces Li+-polymer interactions along the polymer chains, facilitating the decomplexation of Li+ from the polymer chain; (2) The fluorine groups on the polymer chains substantially increase the number of complexation sites, thereby shortening the Li+ hopping distance; and (3) Solvent molecules is an important carrier to dissociate Li-salt and transport the Li+. This unique molecular architecture allows the fluorinated polymer electrolyte to decouple the ionic conduction from the polymer relaxation and to reduce the Li+ transport energy barrier (Supplementary Fig. 22, with detailed discussion in Supplementary Note 6). Therefore, in the fluorinated quasi-solid polymer electrolyte, the ionic conduction is predominantly facilitated through the polymer chains and the surrounding solvents via the movement and exchange of ion-dipole interactions, specifically involving C = O…Li+ and -C-F…Li+ (Supplementary Fig. 23). This mode of conduction contrasts with previous systems, where the liquid phase or polymer was the primary conductor of ions41,42.

Low-temperature Li metal performance

The electrolytes were initially applied to Li | |Cu cells to characterize the Li metal plated at temperatures of interest, conducting at a high-capacity of 5 mAh cm−2 (current density: 0.5 mA cm−2) (Fig. 4a–c). The fluorinated quasi-solid polymer electrolyte demonstrated smooth Li deposition/stripping profiles with stable voltage outputs, a feature not observed in the non-fluorinated polymer electrolyte and the liquid electrolyte, which exhibited indications of soft-shorting events. Subsequently, the cells were disassembled to examine the morphology of the plated Li. Photographs and scanning electron microscope (SEM) images of the Cu electrodes (Fig. 4d) reveal a significant reduction in the observable amount of deposited Li in the liquid electrolyte, accompanied by a decrease in diameter to approximately ~1 μm. A single localized dendrite was observed from 30 °C to −20 °C, and nearly no deposits were visible at −40 °C. However, the non-fluorinated quasi-solid polymer electrolyte exhibited the presence of black substance and dendritic Li when the temperature dropped below −20 °C (Fig. 4e). These Li deposits pose hazards, as they are prone to disconnect from the current collector, resulting in the formation of “dead” Li, which can penetrate the separator, leading to internal short-circuit and battery failure43. In contrast, the fluorinated quasi-solid polymer electrolyte consistently produced uniform Li metal depositions at 30 °C, −20 °C, and −40 °C, with the surfaces of deposited Li exhibiting smooth and dense structures. Additionally, the chunk size of the deposited Li was observed to decrease from ~10 μm to ~1 μm as the temperature decreased from 30 °C to −40 °C (Fig. 4f).

a–c Li deposition profiles in liquid electrolyte, non-fluorinated quasi-solid polymer electrolyte, and fluorinated quasi-solid polymer electrolyte at 0.5 mA cm−2 with a cutoff capacity of 5 mAh cm−2. Optical photographs and SEM images of Cu current collectors after the corresponding deposition experiments in liquid electrolyte (d), non-fluorinated quasi-solid polymer electrolyte (e), and fluorinated quasi-solid polymer electrolyte (f). g Atomic ratios of F and O in the SEI formed in different electrolytes at different sputtering time periods. The characterized Li metal negative electrodes were collected from Li | |Li symmetric cells after 10 times Li plating/stripping at 30 °C and 0.3 mA cm−2 with a cut-off capacity of 0.6 mAh cm−2. hThe activation energy of Li+ desolvation process derived from Nyquist plots of cycled Li | |Li symmetric cells with different electrolytes after 20 times Li plating/stripping at 0.3 mA cm−2 with a cutoff capacity of 0.6 mAh cm−2. i Li+ desolvation activation energy obtained from quantum chemistry simulations of different electrolytes.

The Li plating/stripping Coulombic efficiency of each electrolyte was subsequently determined in Li | |Cu cells44. As illustrated in Supplementary Fig. 24a and Supplementary Note 7, the fluorinated quasi-solid polymer electrolyte maintains high Coulombic efficiency values, with an efficiency of 99.1% at 30 °C. In contrast, the non-fluorinated polymer electrolyte and the liquid electrolyte exhibit lower efficiencies of 83.7% and 88.9%, respectively. Moreover, the Li plating/stripping performance of symmetrical Li | |Li cells was evaluated (Supplementary Figs. 25 and 26). The cells utilizing the liquid electrolyte, the non-fluorinated quasi-solid polymer electrolyte, and the quasi-solid (poly-BA)/MTFP electrolyte failed after 700, 475, and 398 hours, respectively. However, the Li | |Li cell employing the fluorinated quasi-solid polymer electrolyte demonstrated very stable Li plating/stripping for over 1000 hours, exhibiting a small overpotential (~30 mV) and negligible fluctuation at 0.6 mAh cm−2 (0.3 mA cm−2). These consistent Li plating/stripping behaviors in both Li | |Cu and Li | |Li cells suggest that the fluorinated quasi-solid polymer electrolyte plays a critical role in regulating the Li metal performance by optimizing the Li+ transport processes and interfacial kinetic stability (Supplementary Fig. 27 and Supplementary Note 8). These positive effects are highly desirable for broad-temperature operation.

In-depth X-ray photoelectron spectroscopy (XPS) was utilized to analyze the chemical composition of the SEIs formed on cycled Li metal negative electrodes. Figure 4g and supplementary Table 1 present the atomic ratios of selected elements collected at various depths. Detailed XPS spectra for different electrolytes are provided in Supplementary Fig. 28 and Supplementary Note 9. Examination of the Li metal negative electrode cycled in the liquid electrolyte and the non-fluorinated quasi-solid polymer electrolyte revealed elevated contents of O-containing species derived from carbonate esters or polymers, with a less presence of F-containing species. In contrast, the Li metal negative electrode cycled with the fluorinated quasi-solid polymer electrolyte exhibited a notably high atomic ratio of F element, with minimal detection of O-containing species. The robust SEI layer regulates the Li⁺ diffusion kinetics more effectively, thus promoting uniform lithium deposition.

The enhanced Li+ transport kinetics of the fluorinated quasi-solid polymer electrolyte were investigated through temperature-dependent EIS measurements of cycled Li | |Li symmetric cells (Supplementary Fig. 29). Activation energies for the Li+ ion desolvation process were calculated from ion transfer (Rct) resistances45. The activation energy of the Li+ ion desolvation process for the fluorinated quasi-solid polymer electrolyte (54.4 kJ mol−1) is notably lower compared to that of the liquid electrolyte (66.5 kJ mol−1) and the non-fluorinated polymer electrolyte (60.5 kJ mol−1), as depicted in Fig. 4h and supplementary Tables 2–4. This disparity can be attributed to the weak complexation ability of HFA toward Li+, which facilitates the Li+ desolvation from ion ligands. Furthermore, the desolvation energy was assessed via the quantum chemistry simulations, yielding binding energies of −569.1, −491.1, and −477.0 kJ mol−1 for the liquid electrolyte, the non-fluorinated quasi-solid polymer electrolyte, and the fluorinated quasi-solid polymer electrolyte (Fig. 4i and Supplementary Data 1), respectively. These findings further corroborate the notion that the fluorination accelerates the Li+ desolvation process.

Normally, the Li deposition dynamics would proceed in a tip-driven manner in the non-fluorinated system due to the increased driving force provided by the high-surface-area dendritic Li46; such growth would eventually lead to rampant shorting observed in the non-fluorinated system below −20 °C. However, the weakly bound HFA system of the fluorinated quasi-solid polymer electrolyte exhibits homogeneous Li deposition behavior at these temperatures.

Performances of quasi-solid-state lithium metal batteries

To showcase the wide-temperature performance of the fluorinated quasi-solid polymer electrolyte, a commercially relevant Ni-rich layer positive electrode (NCM811) with the cutting off voltage at 4.5 V was selected for cell construction. In Fig. 5a and Supplementary Figs. 30 and 31, the broad-temperature performance of the fluorinated quasi-solid polymer electrolyte in Li | |NCM811 coin cells at a specific current of 20 mA g−1 is illustrated. Below −30 °C, the Li | |NCM811 cell with the liquid electrolyte failed to operate due to the solidification of the electrolyte. Moreover, significantly lower capacity retentions were observed in the Li | |NCM811 cells with the non-fluorinated polymer electrolyte and the quasi-solid (poly-BA)/MTFP electrolyte across temperatures ranging from −40 to 70 °C. Additionally, cells with the liquid electrolyte, the non-fluorinated polymer electrolyte, and the quasi-solid (poly-BA)/MTFP electrolyte experienced rapid capacity decay and fluctuation when the working temperature exceeded 60 °C. In contrast, good performance was achieved in the Li | |NCM811 cell with the fluorinated quasi-solid polymer electrolyte under the same conditions. It delivered capacities of 106, 144, 167, 224, 250, and 251 mAh g−1 at −40, −30, −20, 30, 60, and 70 °C, respectively. Notably, the cell with the fluorinated quasi-solid polymer electrolyte exhibited high retention of its 30 °C capacity at low temperatures: 64.3% at −30 °C and 47.3% at −40 °C. This suggests that the fluorinated quasi-solid polymer electrolyte enabled fast ion transport kinetics and smaller polarization, thereby resulting in a larger output capacity.

a Broad temperature operations from −40 to 70 °C of Li | |NCM811 coin cells with different electrolytes at 20 mA g−1. b Cycling performances of Li | |NCM811 coin cells with different electrolytes at −20 °C and 60 mA g−1. c Rate performances of Li | |NCM811 coin cells with different electrolytes. d Capacity retention rates as compared to those at 0.2 C. e Cycling performances of Li | |NCM811 coin cells with different electrolytes at 60 mA g−1 under practical conditions.

The Li | |NCM811 coin cell utilizing the fluorinated quasi-solid polymer electrolyte also demonstrated significantly extended cycling stability at both −20 °C and 60 °C. As illustrated in Fig. 5b and Supplementary Fig. 32, this cell achieved a high capacity of nearly 123 mAh g−1 and maintained a capacity retention of 94.3% with a consistent Coulombic efficiency of 99.9% over 200 cycles at 60 mA g−1. In contrast, the Li | |NCM811 coin cells employing the liquid electrolyte, the non-fluorinated quasi-solid polymer electrolyte, and the quasi-solid (poly-BA)/MTFP electrolyte exhibited rapid capacity decay. In addition, these cells were subjected to cycling at 60 °C to assess their performance under broad-temperature conditions. As depicted in Supplementary Figs. 33 and 34, the Li | |NCM811 coin cell employing the fluorinated quasi-solid polymer electrolyte demonstrated higher capacity retention at 60 °C, as compared to those employing the liquid electrolyte, the non-fluorinated quasi-solid polymer electrolyte, and the quasi-solid (poly-BA)/MTFP electrolyte. This highlights the operational versatility and effectiveness of the fluorinated quasi-solid polymer electrolyte.

The fluorinated quasi-solid polymer electrolyte was further subjected to rigorous testing to assess its capability in enabling fast-charging and accommodating high-loading positive electrodes under practical conditions. Leveraging the enhanced Li+ decomplexation process and transport kinetics facilitated by the fluorinated quasi-solid polymer electrolyte, the assembled Li | |NCM811 cell demonstrated the capability to cycle at high rates, delivering specific capacities of 220, 210, 200, 190, 176, and 155 mAh g−1 at 0.2, 0.5, 1, 2, 5, and 10 C, respectively. Upon reducing the rate back to 0.2 C, the specific capacity recovered to 215 mAh g−1 (Fig. 5c and Supplementary Figs. 35 and 36). Notably, the fluorinated quasi-solid polymer electrolyte retained 70.5% capacity retention at 10 C, despite experiencing a 50-fold increase in discharge current (Fig. 5d and Supplementary Fig. 37). In contrast, the reference electrolytes failed to perform adequately, with the cells utilizing the liquid electrolyte, the non-fluorinated polymer electrolyte, and the quasi-solid (poly-BA)/MTFP electrolyte delivering only 45.4%, 5.6% and 10.4% capacity retention at 10 C, respectively. These results unequivocally demonstrate that the fluorinated quasi-solid polymer electrolyte facilitates rapid charge-discharge processes in solid-state batteries.

Moreover, the cycling stability of solid-state lithium batteries was examined under challenging conditions, including high-loading positive electrode, lean electrolyte, and limited Li excess. As illustrated in Fig. 5e and Supplementary Fig. 38, even when subjected to practical conditions, such as a positive electrode loading of approximately 2.5 mAh cm−2, a negative to positive (N/P) ratio of around 4, and an electrolyte to capacity (E/C) ratio of roughly 2.5 g (Ah)−1, the Li | |NCM811 cell incorporating the fluorinated quasi-solid polymer electrolyte demonstrated improved cycling stability. It sustained a high capacity of 182 mAh g−1 and retained 86% of its capacity over 200 cycles at 60 mA g−1. In contrast, under the same conditions, cells utilizing the liquid electrolyte, the non-fluorinated polymer electrolyte, and the quasi-solid (poly-BA)/MTFP electrolyte demonstrated significantly shorter cycling lifespans, with operation ceasing after only 45, 70 and 50 cycles, respectively. This disparity indicates the detrimental impact of side reactions on capacity fade, which is effectively mitigated by the superior performance of the fluorinated quasi-solid polymer electrolyte. Supplementary Fig. 39 presented additional electrochemical data employing fluorine-containing quasi-solid polymer electrolytes, providing further validation of the electrolyte design’s reversibility. Moreover, 4.8 V lithium metal batteries with Li1.2Ni0.13Co0.13Mn0.54O2 (Li-rich) positive electrodes were assembled to evaluate the applicability of the fluorinated polymer-based electrolyte (Supplementary Fig. 40). The charge-discharge curves show good electrochemical stability, characterized by well-defined voltage plateaus and the absence of electron-leakage signals. The cell delivers an initial capacity of 260 mAh g⁻¹ and retains 81% of its capacity after 70 cycles at 125 mA g−1. These results demonstrate that the fluorinated polymer-based electrolyte maintains electrochemical stability in the 4.8 V Li | |Li-rich cells.

To further assess the practicality of the fluorinated quasi-solid polymer electrolyte, Li | |NCM811 pouch cells were assembled with lean electrolyte (2.5 g Ah−1) and a low N/P ratio of 1.6. The cell capacity amounted to approximately 2.6 Ah. (Fig. 6a). The fluorinated quasi-solid polymer electrolyte demonstrated enhanced performance in the Li | |NCM811 pouch cell, exhibiting high-capacity retention and minimal voltage polarization during cycling. After 20 cycles at 20 mA g−1, the cells maintained a capacity retention of 99.7% (Fig. 6b). Accelerating rate calorimetry (ARC) tests were performed to evaluate the thermal safety of the fully charged 2-Ah Li | |NCM811 pouch cell. As shown in Supplementary Fig. 41, the self-exothermic onset temperature (T₁) of the fluorinated quasi-solid battery increased from 82 °C to 142 °C. It also exhibited a higher thermal runaway onset temperature (T₂ = 196 °C) and a prolonged self-heating duration (Δt = 4.5 h), compared to the liquid electrolyte cell, which showed a T₂ of 125 °C and a Δt of 1.2 h. Moreover, the maximum thermal runaway temperature (T₃) was significantly reduced to 388 °C, indicating a notable decrease in the total energy released during thermal runaway. Nail puncture test further evaluates the safety of the battery under real cases. As depicted in Fig. 6c, Supplementary Fig. 42, and Movie 2, no significant increase in temperature or decrease in voltage was detected, and the pouch cell did not show any signs of smoking or burning during the puncture test. Remarkably, even after the puncture test, the battery retained the ability to charge a mobile phone (Supplementary Fig. 43), demonstrating good reliability and safety of the fluorinated quasi-solid polymer electrolyte for solid-state batteries.

a Schematic illustration of Li | |NCM811 pouch cell. b Charge-discharge voltage profiles of Li | |NCM811 pouch cell at 20 mA g−1. c Optical photograph showing the needle-puncture test of the Li | |NCM811 pouch cell. d Li | |NCM811 pouch cell using the fluorinated quasi-solid polymer electrolyte was powering an electric fan at −51.3 °C. e Comparison of broad-temperature performances of polymer-based quasi-solid-state batteries.

Furthermore, the Li | |NCM811 pouch cell in a dry ice/ethanol slush bath successfully powered an electric fan at −51.3 °C (Fig. 6d, and Supplementary Movie 3). This Li | |NCM811 pouch cell delivered a capacity of 76 mAh when charged at 30 °C and discharged at −50 °C at 6 mA g−1, corresponding to 51% of its 30 °C capacity (Supplementary Fig. 44). Notably, the Li | |NCM811 pouch cell retained 39% of its 30 °C discharge capacity under the demanding conditions of repeated cycling at −50 °C (Supplementary Fig. 44). Figure 6e exhibits the operational temperature limits of solid-state batteries with polymer electrolytes47,48,49,50,51,52,53. Notably, the battery with the fluorinated quasi-solid polymer electrolyte has surpassed the performance of the other batteries operating at low temperatures. These findings reinforce the significance of the electrolyte design and molecular-scale understanding of the electrolyte chemistry in enhancing the electrochemical performance of polymer-based electrolytes.

Application of fluorinated polymer electrolyte in sodium metal batteries

The fluorination strategy, aimed at optimizing the ionic conformation to establish rapid ion transport pathways, exhibits potential for broader applications beyond lithium-ion systems. By substituting the LiFSI salt with NaFSI salt, the fluorinated quasi-solid polymer electrolyte demonstrates efficacy in facilitating sodium-based batteries to operate across a broad temperature spectrum as well.

Electrochemical assessments of the Na plating/stripping behavior on Na metal negative electrodes were conducted in symmetric Na | |Na cells employing the fluorinated quasi-solid polymer electrolyte, which demonstrated good Na plating/stripping behavior for 500 hours at 30 °C and −20 °C, with a current density of 0.1 mA cm−2 and a capacity of 0.1 mAh cm−2 (Supplementary Fig. 45). Supplementary Fig. 46 illustrates the broad-temperature performance of the fluorinated quasi-solid polymer electrolyte in Na | |Na3V2(PO4)3 (NVP) coin cells. At a specific current of 23.4 mA g−1, the coin cell of Na | |NVP delivered capacities of 46, 80, 100, 116, 114, and 115 mAh g−1 at −40 °C, −30 °C, −20 °C, 30 °C, 60 °C, and 70 °C, respectively. Moreover, Supplementary Fig. 47 presents the cycling stability of Na | |NVP coin cells with the fluorinated quasi-solid polymer electrolyte at different temperatures. Specifically, the cells maintained steady cycling at 58.5 mA g−1 and −20 °C for 100 cycles, exhibiting a discharge capacity of 105 mAh g−1 with a capacity retention of 95.2%. At 585 mA g−1 and 30 °C, 95.5% of capacity was retained after 400 cycles with an average Coulombic efficiency of 99.8%. Even at a high temperature of 60 °C, the Na | |NVP coin cells cycled steadily for over 200 cycles at 117 mA g−1, demonstrating a Coulombic efficiency of about 99.2%. The cell displayed high rate performance with discharge capacities of 112, 109, 104, 98, 91, and 84 mAh g−1 at 1, 2, 5, 10, 15, and 20 C, respectively. Upon returning to a rate of 1 C, the specific discharge capacity recovered to 110 mAh g−1, accounting for 98.2% of its original capacity (Supplementary Fig. 48). The fluorinated quasi-solid polymer electrolyte has demonstrated its effectiveness in enabling sodium-based batteries to operate efficiently across a wide temperature range, making it a versatile solution for both lithium and sodium battery technologies.

Discussion

In summary, we propose design principles for polymer-based electrolytes tailored for solid-state batteries that can operate across a wide temperature range. At the core of these principles is the selection of polymers exhibiting low ion-dipole interactions that demonstrate a low Li+ decomplexation energy while minimally compromising ionic dissociation ability, paired with plasticizers that have low donor numbers and moderate dielectric constants to optimize lithium salt dissociation. Through systematic molecular design, we have developed a highly conductive fluorinated quasi-solid polymer electrolyte featuring a unique fluorine-oxygen co-coordination structure. This coordination facilitates the decomplexation and transport of Li⁺ ions within the polymer electrolyte, promoting the formation of rapid Li⁺ transport pathways along the polymer chains and adjacent solvent molecules, thereby ensuring a uniform Li⁺ flux at the Li metal negative electrode interface.

Therefore, the polymer-based Li | |NCM811 cells have exhibited high-rate capability of 10 C, while expanding the operational temperatures to the range from −50 °C to 70 °C, a significant improvement over previously reported polymer-based batteries. Importantly, the 4.5V Li||NCM811 cell has demonstrated improved performance when cycling at 20 mAg−1 and −30 °C, retaining over 64.3 % of its initial discharge capacity after cycling at 30 °C. Furthermore, the Li | |NCM811 cells have exhibited stable long-term cycling, with a capacity retention of 86 % after 200 cycles at 60 mA g−1 and 30 °C. Also importantly, employing similar design principles, quasi-solid-state sodium batteries have exhibited steady operation across a broad temperature range as well.

Our work offers advanced perspectives on regulating electrolyte chemistry to develop stable, wide-temperature solid-state batteries for practical applications. These findings are especially valuable for creating rechargeable batteries that operate reliably under specific conditions, such as high/low temperatures or rapid charging. By emphasizing safety, our research provides crucial guidance for designing and implementing next-generation energy storage systems.

Methods

Materials

2,2,3,4,4,4-hexafluorobutyl acrylate (HFA, >98.0% (GC)), butyl acrylate (BA, >99.0% (GC)), methyl 3,3,3-trifluoropropanoate (MTFP, >98.0% (GC)) and Methyl propionate (MP, >99.5% (GC)), were purchased from Tokyo Chemical Industry Co., Ltd, and they were dried with 4 Å molecular sieves (Sigma-Aldrich) before use. Fluoroethylene carbonate (FEC, 99.95%), lithium bis(fluorosulfonyl)imide (LiFSI, 99.9%), sodium Bis(fluorosulfonyl)imide (NaFSI, 99.9%), and the liquid electrolyte (i.e., 1 M lithium hexafluorophosphate (LiPF6) in an ethylene carbonate (EC): dimethyl carbonate (DMC) 1:1 v/v carbonate solution) were purchased from DoDoChem. Active materials (LiNi0.8Co0.1Mn0.1O2 (NCM811) powders), Li metal negative electrode (250 μm), conductive carbon, polyvinylidene fluoride (PVDF), anhydrous N-methyl-2-pyrrolidone (NMP, 99.9% purity), carbon-coated aluminum (Al, 15 μm-thick) foil, and Celgard 2500 (PP, 25 μm thick) were purchased from the Guangdong Canrd New Energy Technology Co., Ltd.

NCM811 electrodes containing 90 wt.% active material, 5 wt.% conductive carbon, and 5 wt.% polyvinylidene fluoride binder in NMP were coated on Al foil current collectors with active material mass loadings of 2.5 or 12.5 mg cm−2. The rolled electrodes had a thickness of 40 μm, a compacted density of 3.4 g cm−3 and a porosity of 26.9%, corresponding to a loading level of 12.5 mg cm−2. The electrodes were punched into disks with a diameter of 12 mm and dried in a vacuum for 12 h at 80 °C before use.

Preparation of quasi-solid polymer electrolytes

Fluorinated quasi-solid polymer electrolytes were prepared in an argon gas-filled glovebox (H2O < 0.1 ppm, O2 < 0.1 ppm). 1 M LiFSI was dissolved first in a mixture of MTFP and FEC (at a molar ratio of 9:1) and stirred for 3 h to obtain a homogeneous and transparent solution. Then, HFA were added to the above obtained solution and mixed thoroughly. The polymer monomers account for 25% of the final solution molar ratio. Finally, 1 wt.% AIBN was dissolved in the liquid precursor as the thermal initiator. Subsequently, the liquid precursor was immediately injected into coin or pouch cells, in which the PP was used as the separator, and then assembled cells were kept at 60 °C for 2 h to realize spontaneous polymerization; in such a way, quasi-solid-state batteries were obtained. For comparison, the non-fluorinated quasi-solid polymer electrolyte was prepared by replacing HFA and MTFP with BA and MP.

Physicochemical characterizations

For structural analysis, Fourier transform infrared (FTIR) spectra were acquired for both the precursor solution and the quasi-solid polymer electrolyte using the attenuated total reflection mode (Thermo Scientific, Nicolet iS50R)53. Raman spectroscopy investigations were conducted by a Micro-laser confocal Raman spectrometer (Horiba LabRAM HR800, France). Solid-state Nuclear Magnetic Resonance (ssNMR) investigation, 7Li and 19F ssNMR experiments were carried out on a Bruker Avance III 500 MHz (11.7 T) spectrometer at resonance frequencies of 73.6, 194.4, and 125.7 MHz. The O K-edge X-ray absorption near-edge structure (XANES) data were collected at the catalysis and surface science of the BL11U Soft X-Ray beamline at the National Synchrotron Radiation Laboratory (NSRL) in Hefei, China.

The cycled Li | |Cu and Li | |Li cells were disassembled in an Ar-filled glovebox, and Cu electrode (or Li electrode) was recollected, and washed three times with DMC solvents inside a glovebox (H2O < 0.1 ppm, O2 < 0.1 ppm). Li deposition morphology of Li | |Cu cells was characterized by SEM at 5.0 kV (NovaNanoSEM450). The chemical compositions of SEIs were studied by X-ray photoelectron spectroscopy (XPS, PHI 5000 VersaProbe III). Argon ion sputtering was adopted for the depth profile analysis on the Li electrode. Accelerating rate calorimetry (ARC) tests were performed in heat-wait-search mode, where the temperature was increased in 5 °C increments, with each increment followed by a 30-minute stabilization period.

Electrochemical measurements

All coin cells were assembled in an argon-filled glove box (O2 and H2O < 0.1 ppm) by sandwiching a 25 μm PP separator between a 250 μm Li metal negative electrode and a single-side coated NCM811 positive electrode, with about 30 μL electrolyte. The electrochemical stability of the electrolyte was evaluated by linear sweep voltammetry (LSV; 2.5–7 V) and cyclic voltammetry (CV; –0.2 to 2.5 V) on Li | |Pt coin cells at a scan rate of 1 mV s−1 and 30 °C using a Gamry Interface 1000E electrochemical workstation54. Ionic conductivities of the quasi-solid polymer electrolytes were measured via electrochemical impedance spectroscopy (EIS) using a custom glass cell (20 mm diameter) with two embedded stainless steel electrodes. Measurements were conducted over a temperature range of −40 to 60 °C with an AC amplitude of 10 mV and a frequency range of 5 MHz to 1 Hz, in which the EIS adopted potentiostatic (0 V vs OCV) with the number of 12 data points of per decade of frequency and 10 seconds for open-circuit voltage time applied before performing the EIS measurement54. The ionic conductivities (σ) of the quasi-solid polymer electrolytes were calculated according to the equation:

where \(l\) (cm) is the thickness of the polymer electrolyte, \(S\) (cm2) is the effective contact area between the electrolyte and stainless steel electrodes, and \(R\) (Ω) is measured by EIS. The Li+ transference number was determined by combining EIS and chronoamperometry with a DC polarization voltage (ΔV = 10 mV) in Li | |Li symmetric coin cells, and calculated using the following equation:

where \({I}_{0}\) and \({I}_{{SS}}\) are the initial and steady-state currents measured by chronoamperometry, and \({R}_{0}\) and \({R}_{{SS}}\) are the initial and steady-state interfacial resistances obtained from EIS.

The Coulombic efficiencies (CE) of lithium deposition/stripping in various electrolytes were evaluated using Li | |Cu coin cells, following the method established by Zhang et al.44. Prior to testing, the Cu substrate underwent preconditioning through one complete deposition/stripping cycle (5 mAh cm−2 at 0.5 mA cm−2). A lithium reservoir (QT = 5 mAh cm−2) was first deposited on the Cu substrate at 0.5 mA cm−2. The cells then underwent n charge-discharge cycles (QC = 1 mAh cm−2 per cycle), followed by complete stripping of the remaining lithium to 1 V at 0.5 mA cm−2. The stripping charge (QS), representing the residual lithium after cycling, was recorded. The average CE was calculated as:

To study the electrochemical stability between Li and quasi-solid polymer electrolytes, Li | |Li symmetric cells and Li | |Cu coin cells were assembled and tested at 30 °C by using a Neware battery test system (CT-4008-5V50mA-164, Shenzhen, China). The galvanostatic charge/discharge tests of Li | |NCM811 coin or pouch cells were performed to evaluate the cycling performance and rate capabilities. The applied specific current and specific capacity were referred to the mass of the active material in the positive electrode. All cells were tested in an environmental test chamber to maintain a stable temperature environment (−60 to 150 °C, MSK-TE906-150P-70-5, Shenzhen Kejing Star Technology Co., Ltd.).

Pouch cells were fabricated under practical conditions using NCM811 positive electrodes and Li metal negative electrodes in an argon-filled glove box (H2O/O2 < 0.01 ppm). Each pouch cell contained 20 double-sided positive electrodes (44 mm × 57 mm) and 21 double-sided Li metal negative electrodes (20 μm Li on 8 μm Cu foil, 45 mm × 58 mm), with PP separators wrapped around the electrodes to prevent short circuits. The cells were filled with 6.5 g of precursor solution, then vacuum-sealed and encapsulated. Following assembly, cells were heated at 60 °C for 2 hours to induce spontaneous polymerization. After pre-charging, the air pocket was removed and the cell was resealed under −95 kPa vacuum to eliminate gases. All cycling tests were conducted under 0.1 MPa pressure applied by stainless steel plates.

The 2032 coin cell case and the doctor blade (KTQ-80 F) and precision disc cutting machine (MSJ-T10) were bought from Shenzhen Kejing Star Technology Co. Ltd. The Li-Cu composite tape was supplied by China Energy Lithium Co., Ltd.

Theoretical calculations

DFT calculation

The ground-state molecular geometries were first optimized using density functional theory (DFT) at the B3LYP/6-311 + G (d, p) level, followed by evaluation of molecular energies and electrostatic potentials (ESPs). All DFT calculations were performed using the Gaussian 09 software package55. The binding energies of Li+(solvent)x complexes were calculated using the following equation:

where, \({E}_{{{Li}}^{+}{({solvent})}_{x}}\) and \({E}_{{{Li}}^{+}{({solvent})}_{x}}\) are the energies of the full optimized complexes with and without Li+, respectively, \({E}_{{{Li}}^{+}}\) is the energy of an isolated Li+. The desolvation energy was evaluated by:

where n is the number of solvent molecules, \({E}_{{total}}[{{Li}}^{+}{(S)}_{n}]\) is the total energy of Li+ combined with n solvent molecules (S = poly-BA, poly-HFA, MP or MTFP), \({E}_{{total}}[S]\) is the energy of one solvent molecule, and \({E}_{{total}}[{{Li}}^{+}{(S)}_{n+1}]\) is the energy of Li+ combined with n + 1 solvent molecules.

The donor number is defined as the negative enthalpy change at 30 °C for a 1:1 adduct formation between SbCl5 and a solvent at low concentration in the 1,2-dichloroethane. To calculate the donor numbers of these three molecules, we calculated the enthalpy of these molecules and three complex clusters with SbCl5 using quantum chemistry method. These structures were optimized under the framework of DFT with PBE0 functional and 6-31 G(d) and SDD basis sets. The vibrational frequency analysis was then carried out for the optimized structure with the same calculation method to obtain the enthalpy.

MD simulations

We used five repeating units to represent the polymer chains in MD calculations. MD simulations were conducted with GROMACS software56. A time step of 1 fs was employed, with a cutoff distance of 1.0 nm for both the van der Waals interactions and electrostatic interactions. The electrostatic interactions were calculated by the particle mesh Ewald method (PME). The nonbonded interaction contains van deer Waals (vdW) and electrostatic interaction, which is described by the following Equations, respectively.

The size of the cubic box is 10×10×10 nm3 (with periodic boundary conditions). The poly-HFA electrolyte system contains 100 Li+,100 FSI−, 600 MTFP and 200 poly-HFA. The interaction parameters of Li+ and FSI−/MTFP/poly-HFA were taken from Amber and GAFF force field, respectively. In the NVT simulations, the V-rescale thermostat with a characteristic time of 2 ns was applied to implemented the constant temperature condition. For the NPT simulations, the simulations were carried out for 40 ns to ensure the system reaching equilibrium, and the last 5 ns of the equilibrium state were used for subsequent post-processing analysis.

The dielectric constant was calculated using the GROMACS software package with the General Amber Force Field (GAFF). Force field parameters and machine learning-predicted restrained electrostatic potential (RESP) charges for MTHF and DFB were generated using the AuToFF web server57. Initial simulation boxes (50 × 50 × 50 Å3) containing 200 molecules were constructed using the Packmol program. The structures were first relaxed through energy minimization, followed by annealing from 0 to 298.15 K with a 1 ps time step for 1 ns to reach equilibrium. The velocity-rescale thermostat (relaxation constant: 1 ps) was used to maintain the temperature at 298.15 K, and Berendsen’s barostat (isothermal compressibility: 4.5×10−5 bar⁻¹) was used to maintain the pressure at 1.01325×105 Pa (1 atm)58. Periodic boundary conditions were applied in all three dimensions. The particle-mesh Ewald (PME) method (cut-off: 15 Å) was used to handle electrostatic interactions, while van der Waals forces were treated with the same cut-off distance.

Following the energy-minimization and equilibration steps, a 20 ns MD simulation was performed, with the trajectory saved every 1 ps. The further statistics results of relative dielectric constants of these three molecules were analyzed from the trajectory data by Gromacs tool-suites.

Data availability

The source data generated in this study are provided in the Source Data file. Source data are provided with this paper.

References

Zhang, Q.-K. et al. Homogeneous and mechanically stable solid-electrolyte interphase enabled by trioxane-modulated electrolytes for lithium metal batteries. Nat. Energy 8, 725–735 (2023).

Feng, Y. et al. Production of high-energy 6-Ah-level Li||LiNi0.83Co0.11Mn0.06O2 multi-layer pouch cells via negative electrode protective layer coating strategy. Nat. Commun. 14, 3639 (2023).

Zhou, X. et al. Gel polymer electrolytes for rechargeable batteries toward wide-temperature applications. Chem. Soc. Rev. 53, 5291–5337 (2024).

Wang, Z.-Y. et al. Achieving high-energy and high-safety lithium metal batteries with high-voltage-stable solid electrolytes. Matter 6, 1096–1124 (2023).

Meng, Y. et al. Designing phosphazene-derivative electrolyte matrices to enable high-voltage lithium metal batteries for extreme working conditions. Nat. Energy 8, 1023–1033 (2023).

Jagger, B. & Pasta, M. Solid electrolyte interphases in lithium metal batteries. Joule 7, 2228–2244 (2023).

Janek, J. & Zeier, W. G. Challenges in speeding up solid-state battery development. Nat. Energy 8, 230–240 (2023).

Fan, L.-Z., He, H. & Nan, C.-W. Tailoring inorganic-polymer composites for the mass production of solid-state batteries. Nat. Rev. Mater. 6, 1003–1019 (2021).

Zhang, Y. et al. A smart risk-responding polymer membrane for safer batteries. Sci. Adv. 9, 5802 (2023).

Song, Z. et al. A reflection on polymer electrolytes for solid-state lithium metal batteries. Nat. Commun. 14, 4884 (2023).

Lennartz, P. et al. Practical considerations for enabling Li|polymer electrolyte batteries. Joule 7, 1471–1495 (2023).

Han, S. et al. Sequencing polymers to enable solid-state lithium batteries. Nat. Mater. 22, 1515–1522 (2023).

Su, Y. et al. Rational design of a topological polymeric solid electrolyte for high-performance all-solid-state alkali metal batteries. Nat. Commun. 13, 4181 (2022).

Tang, L. et al. Polyfluorinated crosslinker-based solid polymer electrolytes for long-cycling 4.5 V lithium metal batteries. Nat. Commun. 14, 2301 (2023).

Yan, W. et al. Hard-carbon-stabilized Li-Si anodes for high-performance all-solid-state Li-ion batteries. Nat. Energy 8, 800–813 (2023).

Li, Z. et al. Ionic conduction in polymer-based solid electrolytes. Adv. Sci. 10, 2201718 (2023).

Wu, Q. et al. Phase regulation enabling dense polymer-based composite electrolytes for solid-state lithium metal batteries. Nat. Commun. 14, 6296 (2023).

Shi, P. et al. A dielectric electrolyte composite with high lithium-ion conductivity for high-voltage solid-state lithium metal batteries. Nat. Nanotechnol. 18, 602–610 (2023).

Sun, Q. et al. Li-ion transfer mechanism of gel polymer electrolyte with sole fluoroethylene carbonate solvent. Adv. Mater. 35, e2300998 (2023).

Xie, X. et al. Influencing factors on Li-ion conductivity and interfacial stability of solid polymer electrolytes, exampled by polycarbonates, polyoxalates and polymalonates. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 62, e202218229 (2023).

Zhang, J. et al. Smart deep eutectic electrolyte enabling thermally induced shutdown toward high-safety lithium metal batteries. Adv. Energy Mater. 13, 2202529 (2022).

Peng, H. et al. Molecular design for in-situ polymerized solid polymer electrolytes enabling stable cycling of lithium metal batteries. Adv. Energy Mater. 14, 2400428 (2024).

Zheng, X. et al. Critical effects of electrolyte recipes for Li and Na metal batteries. Chem 7, 2312–2346 (2021).

Chen, K. et al. Correlating the solvating power of solvents with the strength of ion-dipole interaction in electrolytes of lithium-ion batteries. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 62, e202312373 (2023).

Wang, Y. et al. Fluorination in advanced battery design. Nat. Rev. Mater. 9, 119–133 (2023).

Jie, Y. et al. Towards long-life 500 Wh kg−1 lithium metal pouch cells via compact ion-pair aggregate electrolytes. Nat. Energy 9, 987–998 (2024).

Utomo, N. W., Deng, Y., Zhao, Q., Liu, X. & Archer, L. A. Structure and evolution of quasi-solid-state hybrid electrolytes formed inside electrochemical cells. Adv. Mater. 34, 2110333 (2022).

Wang, C. et al. Molecular-level designed polymer electrolyte for high-voltage lithium-metal solid-state batteries. Adv. Funct. Mater. 33, 2209828 (2022).

Zhu, G.-R. et al. Non-flammable solvent-free liquid polymer electrolyte for lithium metal batteries. Nat. Commun. 14, 4617 (2023).

Mackanic, D. G. et al. Crosslinked poly(tetrahydrofuran) as a loosely coordinating polymer electrolyte. Adv. Energy Mater. 8, 1800703 (2018).

Zhou, H. Y. et al. Supramolecular polymer ion conductor with weakened Li ion solvation enables room temperature all-solid-state lithium metal batteries. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 62, e202306948 (2023).

Mao, M. et al. Anion-enrichment interface enables high-voltage anode-free lithium metal batteries. Nat. Commun. 14, 1082 (2023).

Zhang, P. et al. Revealing the intrinsic atomic structure and chemistry of amorphous LiO2-containing products in Li-O2 batteries using cryogenic electron microscopy. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 144, 2129–2136 (2022).

Zhang, W. et al. Single-phase local-high-concentration solid polymer electrolytes for lithium-metal batteries. Nat. Energy 9, 386–400 (2024).

Wang, M. et al. Temperature-responsive solvation enabled by dipole-dipole interactions towards wide-temperature sodium-ion batteries. Nat. Commun. 15, 8866 (2024).

Qin, M. et al. Dipole-dipole interactions for inhibiting solvent co-intercalation into a graphite anode to extend the horizon of electrolyte design. Energy Environ. Sci. 16, 546–556 (2023).

Geng, C. et al. Superhigh coulombic efficiency lithium-sulfur batteries enabled by in situ coating lithium sulfide with polymerizable electrolyte additive. Adv. Energy Mater. 13, 2204246 (2023).

Qiao, Y. et al. A high-energy-density and long-life initial-anode-free lithium battery enabled by a Li2O sacrificial agent. Nat. Energy 6, 653–662 (2021).

Wang, X. et al. Poly(ionic liquid)s-in-salt electrolytes with co-coordination-assisted lithium-ion transport for safe batteries. Joule 3, 2687–2702 (2019).

Zhang, Z., Nasrabadi, A. T., Aryal, D. & Ganesan, V. Mechanisms of ion transport in lithium salt-doped polymeric ionic liquid electrolytes. Macromolecules 53, 6995–7008 (2020).

He, X. et al. Insights into the ionic conduction mechanism of quasi-solid polymer electrolytes through multispectral characterization. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 60, 22672–22677 (2021).

Chen, F., Wang, X., Armand, M. & Forsyth, M. Cationic polymer-in-salt electrolytes for fast metal ion conduction and solid-state battery applications. Nat. Mater. 21, 1175–1182 (2022).

Weng, S. et al. Temperature-dependent interphase formation and Li+ transport in lithium metal batteries. Nat. Commun. 14, 4474 (2023).

Adams, B. D., Zheng, J., Ren, X., Xu, W. & Zhang, J. G. Accurate determination of Coulombic efficiency for lithium metal anodes and lithium metal batteries. Adv. Energy Mater. 8, 1702097 (2017).

Zhou, X. et al. Regulating Na-ion solvation in quasi-solid electrolyte to stabilize Na metal anode. Adv. Funct. Mater. 33, 2212866 (2022).

Gao, X. et al. Thermodynamic understanding of Li-dendrite formation. Joule 4, 1864–1879 (2020).

Yu, L. et al. Monolithic task-specific ionogel electrolyte membrane enables high-performance solid-state lithium-metal batteries in wide temperature range. Adv. Funct. Mater. 32, 2110653 (2021).

Xu, S. et al. Decoupling of ion pairing and ion conduction in ultrahigh-concentration electrolytes enables wide-temperature solid-state batteries. Energy Environ. Sci. 15, 3379–3387 (2022).

Lin, Z. et al. A wide-temperature superior ionic conductive polymer electrolyte for lithium metal battery. Nano Energy 73, 104786 (2020).

Huang, X. et al. Polyether-b-amide based solid electrolytes with well-adhered interface and fast kinetics for ultralow temperature solid-state lithium metal batteries. Adv. Funct. Mater. 33, 2300683 (2023).

Wen, K. et al. Ion-dipole interaction regulation enables high-performance single-ion polymer conductors for solid-state batteries. Adv. Mater. 34, e2202143 (2022).

Yu, J. et al. In situ fabricated quasi-solid polymer electrolyte for high-energy-density lithium metal battery capable of subzero operation. Adv. Energy Mater. 12, 2102932 (2021).

Li, Z. et al. Tailoring polymer electrolyte ionic conductivity for production of low- temperature operating quasi-all-solid-state lithium metal batteries. Nat. Commun. 14, 482 (2023).

Li, Z., Li, Z., Yu, R. & Guo, X. Dual-salt poly(tetrahydrofuran) electrolyte enables quasi-solid-state lithium metal batteries to operate at −30 °C. J. Energy Chem. 96, 456–463 (2024).

Zhang, G. et al. A monofluoride ether-based electrolyte solution for fast-charging and low-temperature non-aqueous lithium metal batteries. Nat. Commun. 14, 1081 (2023).

Berendsen, H. J. C., van der Spoel, D. & van Drunen, R. GROMACS: A message-passing parallel molecular dynamics implementation. Comput. Phys. Commun. 91, 43–56 (1995).

Wang, Z. et al. Ion-dipole chemistry drives rapid evolution of Li ions solvation sheath in low-temperature Li batteries. Adv. Energy Mater. 11, 2100935 (2021).

Martinez, L., Andrade, R., Birgin, E. G. & Martinez, J. M. PACKMOL: a package for building initial configurations for molecular dynamics simulations. J. Comput. Chem. 30, 2157–2164 (2009).

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to express their appreciation to the funding from the Natural Science Foundation of Hubei Province, China (Grant No. 2022CFA031 X.G.) and the National Key Research and Development Program of China (Grant No. 2021YFB 2401900 X.G.). This work was also supported by the Natural Science Foundation of China (Grant No. 22309056 Z.L. and Grant No. 12172143 H.Y.). The computing work in this paper is completed in the HPC Platform of Huazhong University of Science and Technology. The authors extend their gratitude to theoretical and computational chemistry team from Shiyanjia Lab for providing valuable assistance.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Z.Y.L. and Z.L. performed the experiments, W.L., Q.C., and H.Y. performed the theoretical calculations, and Z.Y.L. and J.F. carried out data analyses. Z.Y.L., Z.L., and X.G. wrote the paper, and X.G. supervised the work.

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Peer review

Peer review information

Nature Communications thanks the anonymous reviewer(s) for their contribution to the peer review of this work. A peer review file is available.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Source data

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Li, Z., Li, W., Li, Z. et al. Fluorine-oxygen co-coordination of lithium in fluorinated polymers for broad temperature quasi-solid-state batteries. Nat Commun 16, 9265 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-025-64356-4

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Version of record:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-025-64356-4